Asymmetric Solvation of the Zinc Dimer Cation Revealed by Infrared Multiple Photon Dissociation Spectroscopy of Zn2+(H2O)n (n = 1–20)

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

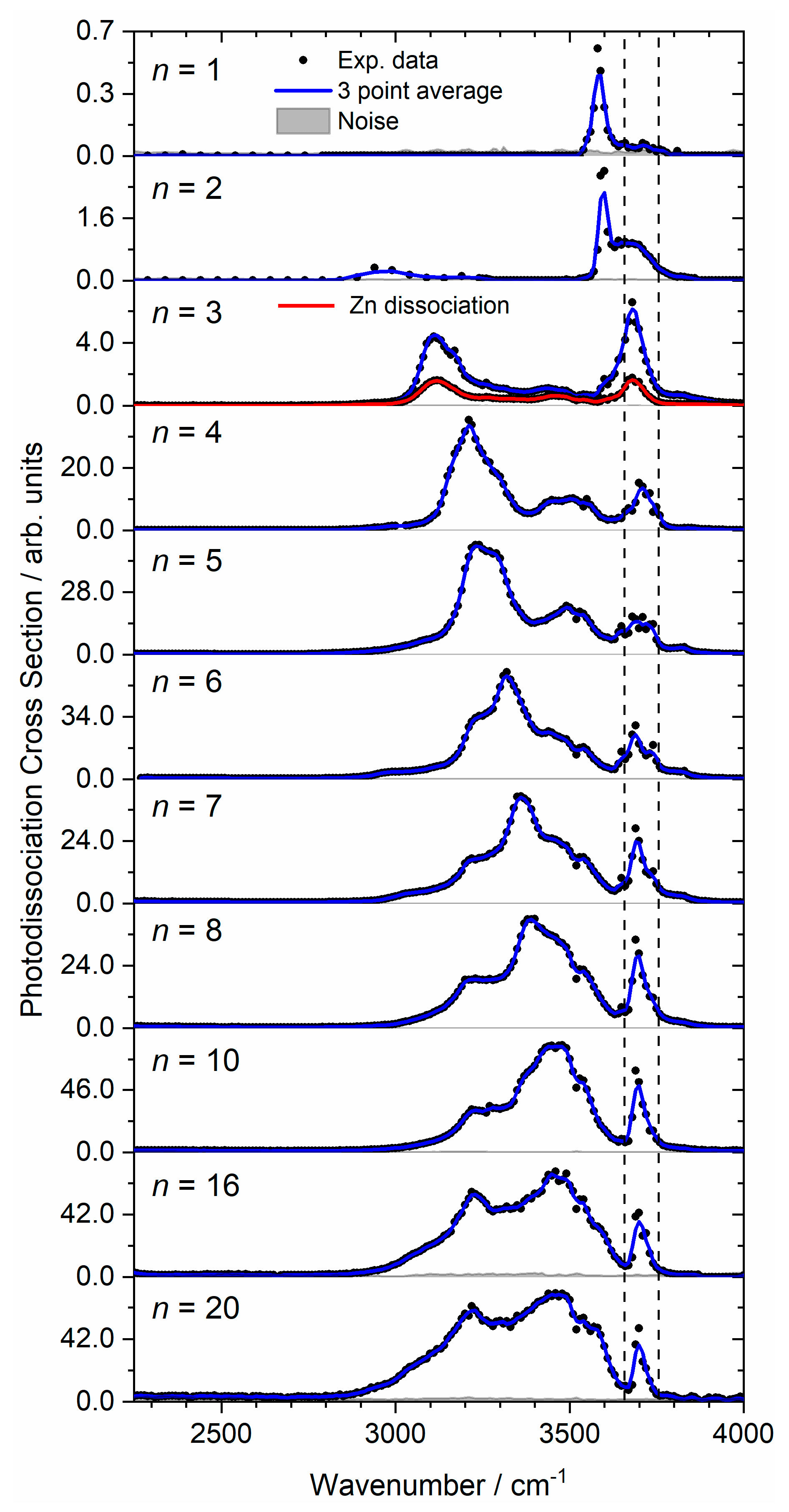

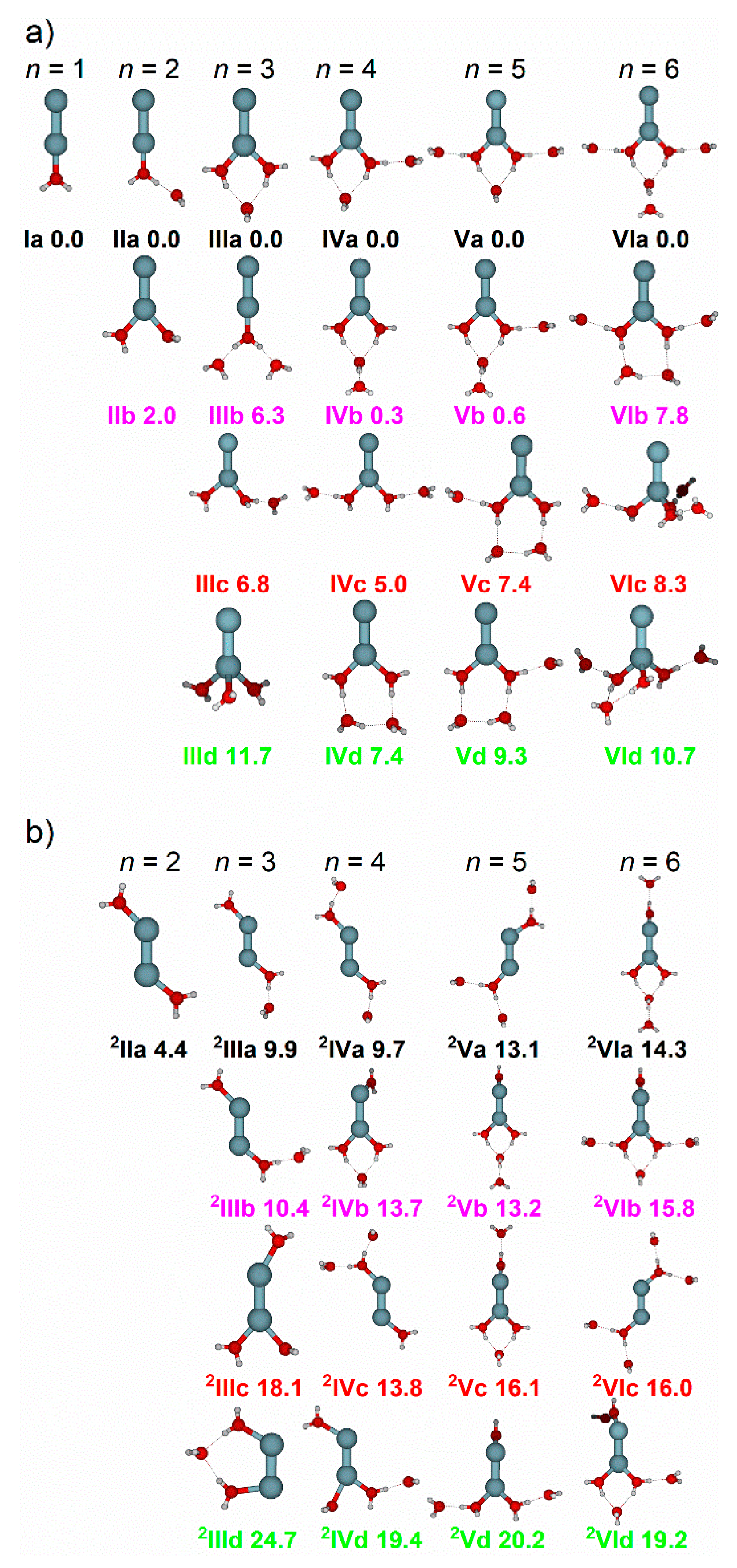

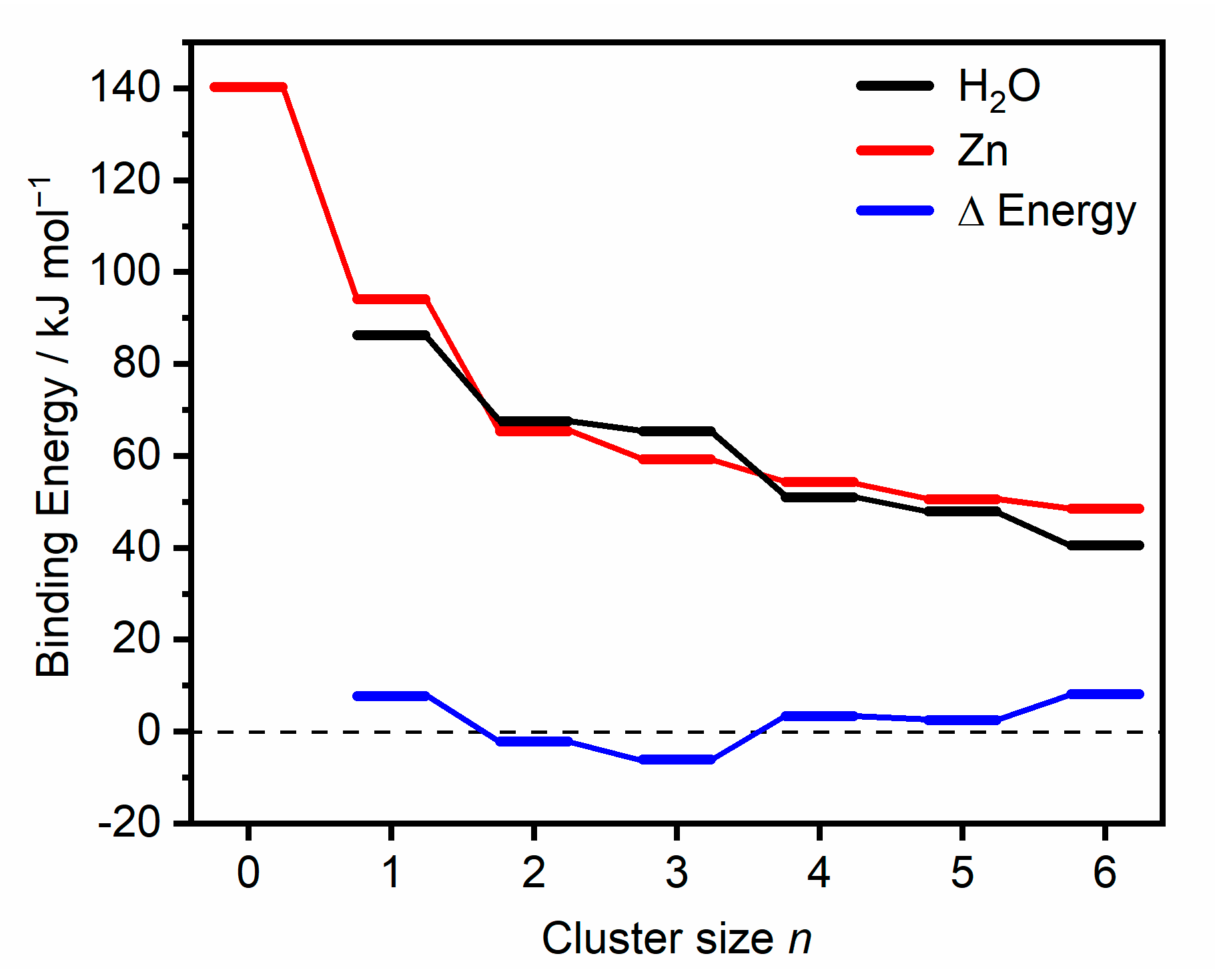

2.1. Zn2+(H2O)1–6

2.1.1. H2O Coordinated to One Zn Atom

2.1.2. H2O Coordinated to Both Zn Atoms

2.1.3. Zn Dissociation

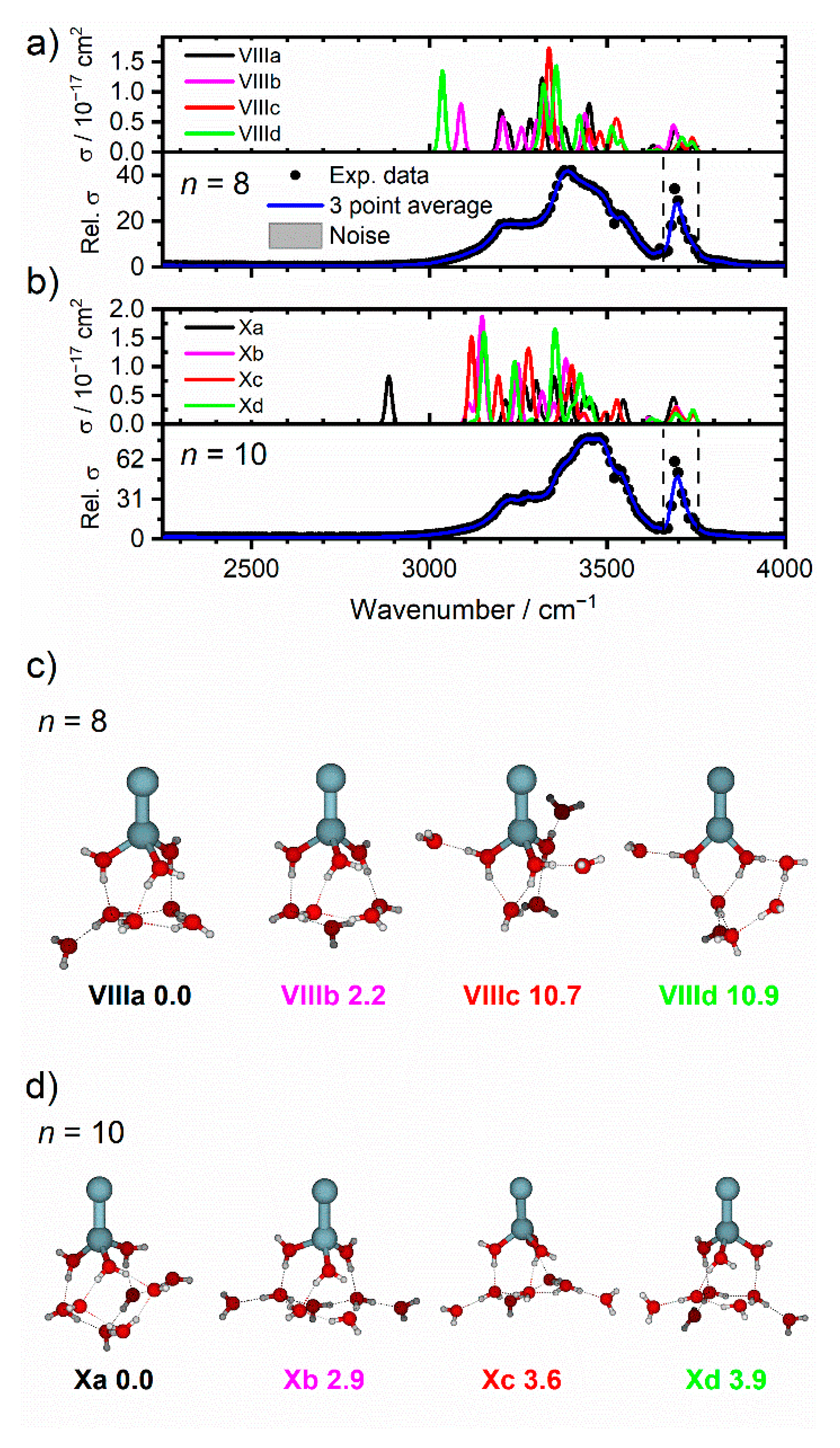

2.2. Zn2+(H2O)8 and Zn2+(H2O)10

3. Experimental and Computational Details

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Cooper, W.F.; Clarke, G.A.; Hare, C.R. Molecular orbital theory of the diatomic molecules of the first row transition metals. J. Phys. Chem. 1972, 76, 2268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bender, C.F.; Rescigno, T.N.; Schaefer, H.F.; Orel, A.E. Potential energy curves for diatomic zinc and cadmium. J. Chem. Phys. 1979, 71, 1122–1227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morse, M.D. Clusters of transition-metal atoms. Chem. Rev. 1986, 86, 1049–1109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buckner, S.W.; Gord, J.R.; Freiser, B.S. Gas phase studies of Zn+2, Ag+3, and Ag+5. J. Chem. Phys. 1988, 88, 3678–3681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czajkowski, M.A.; Koperski, J. The Cd2 and Zn2 van der Waals dimers revisited. Correction for some molecular potential parameters. Spectrochim. Acta A 1999, 55, 2221–2229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flad, H.-J.; Schautz, F.; Wang, Y.; Dolg, M.; Savin, A. On the bonding of small group 12 clusters. Eur. Phys. 1999, 6, 243–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutsev, G.L.; Bauschlicher, C.W. Chemical bonding, electron affinity, and ionization energies of the homonuclear 3d metal dimers. J. Phys. Chem. A 2003, 107, 4755–4767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutsev, G.L.; Mochena, M.D.; Jena, P.; Bauschlicher, C.W., Jr.; Partridge, H., III. Periodic table of 3d-metal dimers and their ions. J. Chem. Phys. 2004, 121, 6785–6797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Wang, G.; Zhao, J. Nonmetal-metal transition in Znn (n = 2–20) clusters. Phys. Rev. A 2003, 68, 013201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Quillian, B.; Wei, P.; Wang, H.; Yang, X.-J.; Xie, Y.; King, R.B.; Schleyer, P.V.R.; Schaefer, H.F.; Robinson, G.H. On the Chemistry of Zn–Zn Bonds, RZn– ZnR (R = [{(2, 6-Pri2C6H3)N(Me)C}2CH]): Synthesis, Structure, and Computations. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005, 127, 11944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Figgen, D.; Rauhut, G.; Dolg, M.; Stoll, H. Energy-consistent pseudopotentials for group 11 and 12 atoms: Adjustment to multi-configuration Dirac–Hartree–Fock data. Chem. Phys. 2005, 311, 227–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, G.; Stace, A.J. Gas phase studies of metal dimer complexes, M2Ln+, where M = Zn and Mn, and L = pyrrole and furan, for n in the range 1–5. Int. J. Mass Spectrom. 2006, 249, 289–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grirrane, A.; Resa, I.; Rodriguez, A.; Carmona, E.; Alvarez, E.; Gutierrez-Puebla, E.; Monge, A.; Galindo, A.; del Río, D.; Andersen, R.A. Zinc– Zinc Bonded Zincocene Structures. Synthesis and Characterization of Zn2(η5-C5Me5)2 and Zn2(η5-C5Me4Et)2. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007, 129, 693–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Philpott, M.R.; Kawazoe, Y. The electronic structure of the dizincocene core. Chem. Phys. 2006, 327, 283–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Truhlar, D.G. A new local density functional for main-group thermochemistry, transition metal bonding, thermochemical kinetics, and noncovalent interactions. J. Phys. Chem. A 2006, 110, 194101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carmona, E.; Galindo, A. Direct bonds between metal atoms: Zn, Cd, and Hg compounds with metal–metal bonds. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2008, 47, 6526–6536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Resa, I.; Carmona, E.; Gutierrez-Puebla, E.; Monge, A. Decamethyldizincocene, a stable compound of Zn (I) with a Zn-Zn bond. Science 2004, 305, 1136–1138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pahl, E.; Figgen, D.; Borschevsky, A.; Peterson, K.A.; Schwerdtfeger, P. Accurate potential energy curves for the group 12 dimers Zn2, Cd2, and Hg2. Theor. Chem. Acc. 2011, 129, 651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oymak, H.; Erkoç, Ş. Group 12 elements and their small clusters: Electric dipole polarizability of zn, cd and hg, zn2 dimer and higher znn microclusters and neutral, cationic and anionic zinc oxide molecules (ZnO, ZnO+ and ZnO−). Int. J. Mod. Phys. B 2012, 26, 1230003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, L.M.; Li, P.; Qiao, L.W.; Tang, K.T. Corresponding states principle and van der Waals potentials of Zn2, Cd2, and Hg2. J. Chem. Phys. 2013, 139, 154306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oda, A.; Ohkubo, T.; Yumura, T.; Kobayashi, H.; Kuroda, Y. Synthesis of an unexpected [Zn2]2+ species utilizing an MFI-type zeolite as a nano-reaction pot and its manipulation with light and heat. Dalton Trans. 2015, 44, 10038–10047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benco, L. Adsorption of small molecules on the [Zn-Zn]2+ linkage in zeolite. A DFT study of ferrierite. Surf. Sci. 2017, 656, 115–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyngdoh, R.H.D.; Schaefer, H.F.; King, R.B. Metal–metal (MM) bond distances and bond orders in binuclear metal complexes of the first row transition metals titanium through zinc. Chem. Rev. 2018, 118, 11626–11706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tarento, R.J. Ionization potentials and charge localization in small charged group 12 clusters. Eur. Phys. J. D 2019, 73, 260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadjadi, S.; Matta, C.F.; Hamilton, I.P. Bonding and metastability for Group 12 dications. J. Comput. Chem. 2021, 42, 40–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jensen, W.B. The place of zinc, cadmium, and mercury in the periodic table. J. Chem. Educ. 2003, 80, 952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parkin, G. Zinc-zinc bonds: A new frontier. Science 2004, 305, 1117–1118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Andrews, L. Infrared spectra of Zn and Cd hydride molecules and solids. J. Phys. Chem. A 2004, 108, 11006–11013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrews, L.; Cho, H.-G. Formation of Short Zn–Zn Bonds Stabilized by Simple Cyanide and Isocyanide Ligands. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2020, 59, 2496–2525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Echeverría, J.; Falceto, A.; Alvarez, S. Zinc–Zinc double bonds: A theoretical study. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2017, 56, 10285–10289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayala, R.; Galindo, A. A theoretical study of the bonding capabilities of the zinc-zinc double bond. Int. J. Quantum Chem. 2019, 119, e25823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Artero, V.; Chavarot-Kerlidou, M.; Fontecave, M. Splitting water with cobalt. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2011, 50, 7238–7266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neumaier, M.; Köppe, R.; Schnöckel, H. Ein molekulares Korrosionsmodell für Metalle? Nachr. Chem. 2008, 56, 999–1004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berg, C.; Achatz, U.; Beyer, M.; Joos, S.; Albert, G.; Schindler, T.; Niedner-Schatteburg, G.; Bondybey, V.E. Chemistry and charge transfer phenomena in water cluster cations. Int. J. Mass Spectrom. Ion Process. 1997, 167, 723–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berg, C.; Beyer, M.; Achatz, U.; Joos, S.; Niedner-Schatteburg, G.; Bondybey, V.E. Stability and reactivity of hydrated magnesium cations. Chem. Phys. 1998, 239, 379–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fox-Beyer, B.S.; Sun, Z.; Balteanu, I.; Balaj, O.P.; Beyer, M.K. Hydrogen formation in the reaction of Zn+(H2O)n with HCl. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2005, 7, 981–985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Linde, C.; Akhgarnusch, A.; Siu, C.-K.; Beyer, M.K. Hydrated magnesium cations Mg+(H2O)n, n ≈ 20–60, exhibit chemistry of the hydrated electron in reactions with O2 and CO2. J. Phys. Chem. A 2011, 115, 10174–10180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van der Linde, C.; Beyer, M.K. The structure of gas-phase [AlnH2O]+: Hydrated monovalent aluminium Al+(H2O)n or hydride-hydroxide HAlOH+(H2O)n−1? Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2011, 13, 6776–6778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beyer, M.; Williams, E.R.; Bondybey, V.E. Unimolecular reactions of dihydrated alkaline earth metal dications M2+(H2O)2, M = Be, Mg, CA Sr, and Ba: Salt-bridge mechanism in the proton-transfer reaction M2+(H2O)2 → MOH+ + H3O+. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1999, 121, 1565–1573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- van der Linde, C.; Beyer, M.K. Reactions of M+(H2O)n, n < 40, M = V, Cr, Mn, Fe, Co, Ni, Cu, and Zn, with D2O reveal water activation in Mn+(H2O)n. J. Phys. Chem. A 2012, 116, 10676–10682. [Google Scholar]

- Beyer, M.; Berg, C.; Görlitzer, H.W.; Schindler, T.; Achatz, U.; Albert, G.; Niedner-Schatteburg, G.; Bondybey, V.E. Fragmentation and intracluster reactions of hydrated aluminum cations Al+(H2O)n, n = 3−50. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1996, 118, 7386–7389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Achatz, U.; Joos, S.; Berg, C.; Beyer, M.; Niedner-Schatteburg, G.; Bondybey, V.E. Generation of hydrated iodide clusters I−(H2O)n by laser vaporization, their fragmentation and reactions with HCl. Chem. Phys. Lett. 1998, 291, 459–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beyer, M.; Achatz, U.; Berg, C.; Joos, S.; Niedner-Schatteburg, G.; Bondybey, V.E. Size dependence of blackbody radiation induced hydrogen formation in Al+(H2O)n hydrated aluminum cations and their reactivity with hydrogen chloride. J. Phys. Chem. A 1999, 103, 671–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Achatz, U.; Fox, B.S.; Beyer, M.K.; Bondybey, V.E. Hypoiodous acid as guest molecule in protonated water clusters: A Combined FT-ICR/DFT Study of I(H2O)n+. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2001, 123, 6151–6156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beyer, M.K. Hydrated metal ions in the gas phase. Mass Spectrom. Rev. 2007, 26, 517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scharfschwerdt, B.; van der Linde, C.; Balaj, O.P.; Herber, I.; Schütze, D.; Beyer, M.K. Photodissociation and photochemistry of V+(H2O)n, n = 1–4, in the 360–680 nm region. Low Temp. Phys. 2012, 38, 717–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ončák, M.; Taxer, T.; Barwa, E.; van der Linde, C.; Beyer, M.K. Photochemistry and spectroscopy of small hydrated magnesium clusters Mg+(H2O)n, n = 1–5. J. Chem. Phys. 2018, 149, 44309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taxer, T.; Ončák, M.; Barwa, E.; van der Linde, C.; Beyer, M.K. Electronic spectroscopy and nanocalorimetry of hydrated magnesium ions [Mg(H2O)n]+, n = 20–70: Spontaneous formation of a hydrated electron? Faraday Discuss. 2019, 217, 584–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barwa, E.; Ončák, M.; Pascher, T.F.; Herburger, A.; van der Linde, C.; Beyer, M.K. Infrared multiple photon dissociation spectroscopy of hydrated cobalt anions doped with carbon dioxide CoCO2(H2O)n−, n = 1–10, in the C–O Stretch Region. Chem. Eur. J. 2020, 26, 1074–1081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barwa, E.; Pascher, T.F.; Ončák, M.; van der Linde, C.; Beyer, M.K. Carbon dioxideactivation at metal centers: Evolution of charge transfer from Mg + to CO2 in [MgCO2(H2O)n]+, n = 0–8. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2020, 59, 7467–7471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heller, J.; Tang, W.K.; Cunningham, E.M.; Demissie, E.G.; van der Linde, C.; Lam, W.K.; Ončák, M.; Siu, C.-K.; Beyer, M.K. Beyer: Getting ready for the hydrogen evolution reaction: The infrared spectrum of hydrated aluminum hydride-hydroxide HAlOH+(H2O)n−1, n = 9–14. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2021, 60. in print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lisy, J.M. Spectroscopy and structure of solvated alkali-metal ions. Int. Rev. Phys. Chem. 1997, 16, 267–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duncan, M.A. Spectroscopy of metal ion complexes: Gas-phase models for solvation. Annu. Rev. Phys. Chem. 1997, 48, 69–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duncan, M.A. Infrared spectroscopy to probe structure and dynamics in metal ion-molecule complexes. Int. Rev. Phys. Chem. 2003, 22, 407–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asmis, K.R. Structure characterization of metal oxide clusters by vibrational spectroscopy: Possibilities and prospects. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2012, 14, 9270–9281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwarz, H.; Asmis, K.R. Identification of active sites and structural characterization of reactive ionic intermediates by cryogenic ion trap vibrational spectroscopy. Chem. Eur. J. 2019, 25, 2112–2126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reinhard, B.M.; Lagutschenkov, A.; Lemaire, J.; Maitre, P.; Boissel, P.; Niedner-Schatteburg, G. Reductive nitrile coupling in niobium—acetonitrile complexes probed by free electron laser IR multiphoton dissociation apectroscopy. J. Phys. Chem. A 2004, 108, 3350–3355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nosenko, Y.; Menges, F.; Riehn, C.; Niedner-Schatteburg, G. Investigation by two-color IR dissociation spectroscopy of Hoogsteen-type binding in a metalated nucleobase pair mimic. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2013, 15, 8171–8178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Craig, S.M.; Johnson, C.J.; Ranasinghe, D.S.; Perera, A.; Bartlett, R.J.; Berman, M.R.; Johnson, M.A. Vibrational characterization of radical ion adducts between imidazole and CO2. J. Phys. Chem. A 2018, 122, 3805–3810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Craig, S.M.; Menges, F.S.; Duong, C.H.; Denton, J.K.; Madison, L.R.; McCoy, A.B.; Johnson, M.A. Hidden role of intermolecular proton transfer in the anomalously diffuse vibrational spectrum of a trapped hydronium ion. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2017, 114, E4706–E4713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, N.R.; Walters, R.S.; Tsai, M.-K.; Jordan, K.D.; Duncan, M.A. Infrared photodissociation spectroscopy of Mg+(H2O)Arn complexes: Isomers in progressive microsolvation. J. Phys. Chem. A 2005, 109, 7057–7067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, N.R.; Walters, R.S.; Pillai, E.D.; Duncan, M.A. Infrared spectroscopy of V+(H2O) and V+(D2O) complexes: Solvent deformation and an incipient reaction. J. Chem. Phys. 2003, 119, 10471–10474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ward, T.B.; Carnegie, P.D.; Duncan, M.A. Infrared spectroscopy of the Ti(H2O)Ar+ ion–molecule complex: Electronic state switching induced by argon. Chem. Phys. Lett. 2016, 654, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carnegie, P.D.; Marks, J.H.; Brathwaite, A.D.; Ward, T.B.; Duncan, M.A. Microsolvation in V+(H2O)n clusters studied with selected-ion infrared spectroscopy. J. Phys. Chem. A 2020, 124, 1093–1103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walters, R.S.; Pillai, E.D.; Duncan, M.A. Solvation dynamics in Ni+(H2O)n clusters probed with infrared spectroscopy. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005, 127, 16599–16610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sasaki, J.; Ohashi, K.; Inoue, K.; Imamura, T.; Judai, K.; Nishi, N.; Sekiya, H. Infrared photodissociation spectroscopy of V+(H2O)n (n = 2–8): Coordinative saturation of V+ with four H2O molecules. Chem. Phys. Lett. 2009, 474, 36–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iino, T.; Ohashi, K.; Inoue, K.; Judai, K.; Nishi, N.; Sekiya, H. Infrared spectroscopy of Cu+(H2O)n and Ag+(H2O)n: Coordination and solvation of noble-metal ions. J. Chem. Phys. 2007, 126, 194302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inoue, K.; Ohashi, K.; Iino, T.; Judai, K.; Nishi, N.; Sekiya, H. Coordination and solvation of copper ion: Infrared photodissociation spectroscopy of Cu+(NH3)n (n = 3–8). Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2007, 9, 4793–4802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iino, T.; Ohashi, K.; Mune, Y.; Inokuchi, Y.; Judai, K.; Nishi, N.; Sekiya, H. Infrared photodissociation spectra and solvation structures of Cu+(H2O)n (n = 1–4). Chem. Phys. Lett. 2006, 427, 24–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cunningham, E.M.; Taxer, T.; Heller, J.; Ončák, M.; van der Linde, C.; Beyer, M.K. Microsolvation of Zn cations: Infrared multiple photon dissociation spectroscopy of Zn+(H2O)n (n = 2–35). Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2021, 23, 3627–3636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandyopadhyay, B.; Reishus, K.N.; Duncan, M.A. Infrared spectroscopy of solvation in small Zn+(H2O)n complexes. J. Phys. Chem. A 2013, 117, 7794–7803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hock, C.; Schmidt, M.; Kuhnen, R.; Bartels, C.; Ma, L.; Haberland, H.; von Issendorff, B. Calorimetric observation of the melting of free water nanoparticles at cryogenic temperatures. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2009, 103, 73401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Donald, W.A.; Leib, R.D.; Demireva, M.; Negru, B.; Neumark, D.M.; Williams, E.R. Average sequential water molecule binding enthalpies of M(H2O)19−1242+ (M = Co, Fe, Mn, and Cu) measured with ultraviolet photodissociation at 193 and 248 nm. J. Phys. Chem. A 2011, 115, 2–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shimanouchi, T. Tables of Molecular Vibrational Frequencies. Consolidated Volume I; National Bureau of Standards: Washington, DC, USA, 1972.

- Yang, N.; Duong, C.H.; Kelleher, P.J.; Johnson, M.A. Capturing intrinsic site-dependent spectral signatures and lifetimes of isolated OH oscillators in extended water networks. Nat. Chem. 2020, 12, 159–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlson, K.D.; Kuschnir, K.R. Interatomic potential energy functions for mercury, cadmium, and zinc from vapor viscosities. J. Phys. Chem. 1964, 68, 1566–1567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ervin, K.; Loh, S.K.; Aristov, N.; Armentrout, P.B. Metal cluster ions: The bond energy of diatomic manganese (1+). J. Phys. Chem. 1983, 87, 3593–3596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leopold, D.G.; Ho, J.; Lineberger, W.C. Photoelectron spectroscopy of mass-selected metal cluster anions. I. Cu−n, n = 1–10. J. Chem. Phys. 1987, 86, 1715–1726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, C.J.; Dzugan, L.C.; Wolk, A.B.; Leavitt, C.M.; Fournier, J.A.; McCoy, A.B.; Johnson, M.A. Microhydration of contact ion pairs in M2+OH−(H2O)n=1–5 (M = Mg, Ca) clusters: Spectral manifestations of a mobile proton defect in the first hydration shell. J. Phys. Chem. A 2014, 118, 7590–7597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akhgarnusch, A.; Tang, W.K.; Zhang, H.; Siu, C.-K.; Beyer, M.K. Charge transfer reactions between gas-phase hydrated electrons, molecular oxygen and carbon dioxide at temperatures of 80–300 K. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2016, 18, 23528–23537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Allemann, M.; Kellerhals, H.; Wanczek, K.P. High magnetic field Fourier transform ion cyclotron resonance spectroscopy. Int. J. Mass Spectrom. Ion Process. 1983, 46, 139–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berg, C.; Schindler, T.; Niedner-Schatteburg, G.; Bondybey, V.E. Reactions of simple hydrocarbons with Nb+n: Chemisorption and physisorption on ionized niobium clusters. J. Chem. Phys. 1995, 102, 4870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schindler, T.; Berg, C.; Niedner-Schatteburg, G.; Bondybey, V.E. Reactions of water clusters H+(H2O)n, n = 3–75, with diethyl ether. Chem. Phys. 1995, 201, 491–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akhgarnusch, A.; Höckendorf, R.F.; Beyer, M.K. Thermochemistry of the reaction of SF6 with gas-phase hydrated electrons: A benchmark for nanocalorimetry. J. Phys. Chem. A 2015, 119, 9978–9985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caravatti, P.; Allemann, M. The “infinity cell”: A new trapped ion cell with radiofrequency covered trapping electrodes for Fourier transform ion cyclotron resonance mass spectrometry. Org. Mass Spectrom. 1991, 26, 514–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bondybey, V.E.; English, J.H. Laser induced fluorescence of metal clusters produced by laser vaporization: Gas phase spectrum of Pb2. J. Chem. Phys. 1981, 74, 6978–6979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dietz, T.G.; Duncan, M.A.; Powers, D.E.; Smalley, R.E. Laser production of supersonic metal cluster beams. J. Chem. Phys. 1981, 74, 6511–6512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marshall, A.G.; Hendrickson, C.L.; Jackson, G.S. Fourier transform ion cyclotron resonance mass spectrometry: A primer. Mass Spectrom. Rev. 1998, 17, 1–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, R.L.; Paech, K.; Williams, E.R. Blackbody infrared radiative dissociation at low temperature: Hydration of X2+(H2O)n, for X = Mg, Ca. Int. J. Mass Spectrom. 2004, 232, 59–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balaj, O.P.; Berg, C.B.; Reitmeier, S.J.; Bondybey, V.E.; Beyer, M.K. A novel design of a temperature-controlled FT-ICR cell for low-temperature black-body infrared radiative dissociation (BIRD) studies of hydrated ions. Int. J. Mass Spectrom. 2009, 279, 5–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thölmann, D.; Tonner, D.S.; McMahon, T.B. Spontaneous unimolecular dissociation of small cluster ions, (H3O+) Ln and Cl-(H2O)n (n = 2–4), under Fourier transform ion cyclotron resonance conditions. J. Phys. Chem. 1994, 98, 2002–2004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunbar, R.C. BIRD (blackbody infrared radiative dissociation): Evolution, principles, and applications. Mass Spectrom. Rev. 2004, 23, 127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schindler, T.; Berg, C.; Niedner-Schatteburg, G.; Bondybey, V.E. Protonated water clusters and their black body radiation induced fragmentation. Chem. Phys. Lett. 1996, 250, 301–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schnier, P.D.; Price, W.D.; Jockusch, R.A.; Williams, E.R. Blackbody infrared radiative dissociation of bradykinin and its analogues: Energetics, dynamics, and evidence for salt-bridge structures in the gas phase. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1996, 118, 7178–7189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sena, M.; Riveros, J.M. The unimolecular dissociation of the molecular ion of acetophenone induced by thermal radiation. Rapid Commun. Mass Spectrom. 1994, 8, 1031–1034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fox, B.S.; Beyer, M.K.; Bondybey, V.E. Black body fragmentation of cationic ammonia clusters. J. Phys. Chem. A 2001, 105, 6386–6392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herburger, A.; van der Linde, C.; Beyer, M.K. Photodissociation spectroscopy of protonated leucine enkephalin. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2017, 19, 10786–10795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donald, W.A.; Leib, R.D.; Demireva, M.; Williams, E.R. Ions in size-selected aqueous nanodrops: Sequential water molecule binding energies and effects of water on ion fluorescence. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011, 133, 18940–18949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Herburger, A.; Ončák, M.; Siu, C.-K.; Demissie, E.G.; Heller, J.; Tang, W.K.; Beyer, M.K. Infrared spectroscopy of size selected hydrated carbon dioxide radical anions CO2−(H2O)n (n = 2–61) in the C−O stretch region. Chem. Eur. J. 2019, 25, 10165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breneman, C.M.; Wiberg, K.B. Determining atom centered monopoles from molecular electrostatic potentials. The need for high sampling density in formamide conformational analysis. J. Comput. Chem. 1990, 11, 361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frisch, M.J.; Trucks, G.W.; Schlegel, H.B.; Scuseria, G.E.; Robb, M.A.; Cheeseman, J.R.; Scalmani, G.; Barone, V.; Petersson, G.A.; Nakatsuji, H.; et al. Gaussian 16, Revision A.03; Gaussian Inc.: Wallingford, CT, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

| Cluster | Experimental IRMPD Band Position/cm−1 | Isomer Assignment and Binding Motif |

|---|---|---|

| Zn2+(H2O) | 3580 3710 | Ia Ia |

| Zn2+(H2O)2 | 2965 3590 3680 | IIa-SA IIa, IIb IIa, IIb |

| Zn2+(H2O)3 | 3110 3160 3445 3605 3680 | IIIc-SA, IIIb-SA(sym) IIIb-SA(asym) IIIa-DA IIIb IIIa–IIIc |

| Zn2+(H2O)4 | 3210 3290 3490 3710 | IVa-S*A, IVb-oDA, IVc-SA IVb-DA IVa-DA IVa–IVc |

| Zn2+(H2O)5 | 3230 3270 3490 3540 3690 | Va-SA, Vb-oDA Vb-SA, Vb-DA/oDA Va-DA Va-DA Va-Vb |

| Zn2+(H2O)6 | 3240 3320 3445 3540 3690 3730 | VIa-S*A, VIa-oDA, VIb-oSA VIb-SA VIa-DA, VIb-D*A VIb-oSA Via, VIb Via, VIb |

| Zn2+(H2O)7 | 2985–3620, 3220, 3360, 3460, 3540, 3690, 3730 | |

| Zn2+(H2O)8 | 3050–3640, 3220, 3390, 3460, 3540, 3670 | |

| Zn2+(H2O)10 | 3050–3645, 3220, 3460, 3530, 3700 | |

| Zn2+(H2O)16 | 2950–3650, 3220, 3450, 3540, 3700 | |

| Zn2+(H2O)20 | 2920–3660, 3220, 3460, 3560, 3700 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Cunningham, E.M.; Taxer, T.; Heller, J.; Ončák, M.; van der Linde, C.; Beyer, M.K. Asymmetric Solvation of the Zinc Dimer Cation Revealed by Infrared Multiple Photon Dissociation Spectroscopy of Zn2+(H2O)n (n = 1–20). Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 6026. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms22116026

Cunningham EM, Taxer T, Heller J, Ončák M, van der Linde C, Beyer MK. Asymmetric Solvation of the Zinc Dimer Cation Revealed by Infrared Multiple Photon Dissociation Spectroscopy of Zn2+(H2O)n (n = 1–20). International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2021; 22(11):6026. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms22116026

Chicago/Turabian StyleCunningham, Ethan M., Thomas Taxer, Jakob Heller, Milan Ončák, Christian van der Linde, and Martin K. Beyer. 2021. "Asymmetric Solvation of the Zinc Dimer Cation Revealed by Infrared Multiple Photon Dissociation Spectroscopy of Zn2+(H2O)n (n = 1–20)" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 22, no. 11: 6026. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms22116026

APA StyleCunningham, E. M., Taxer, T., Heller, J., Ončák, M., van der Linde, C., & Beyer, M. K. (2021). Asymmetric Solvation of the Zinc Dimer Cation Revealed by Infrared Multiple Photon Dissociation Spectroscopy of Zn2+(H2O)n (n = 1–20). International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 22(11), 6026. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms22116026