Investigation of Enantioselective Membrane Permeability of α-Lipoic Acid in Caco-2 and MDCKII Cell

Abstract

:1. Introduction

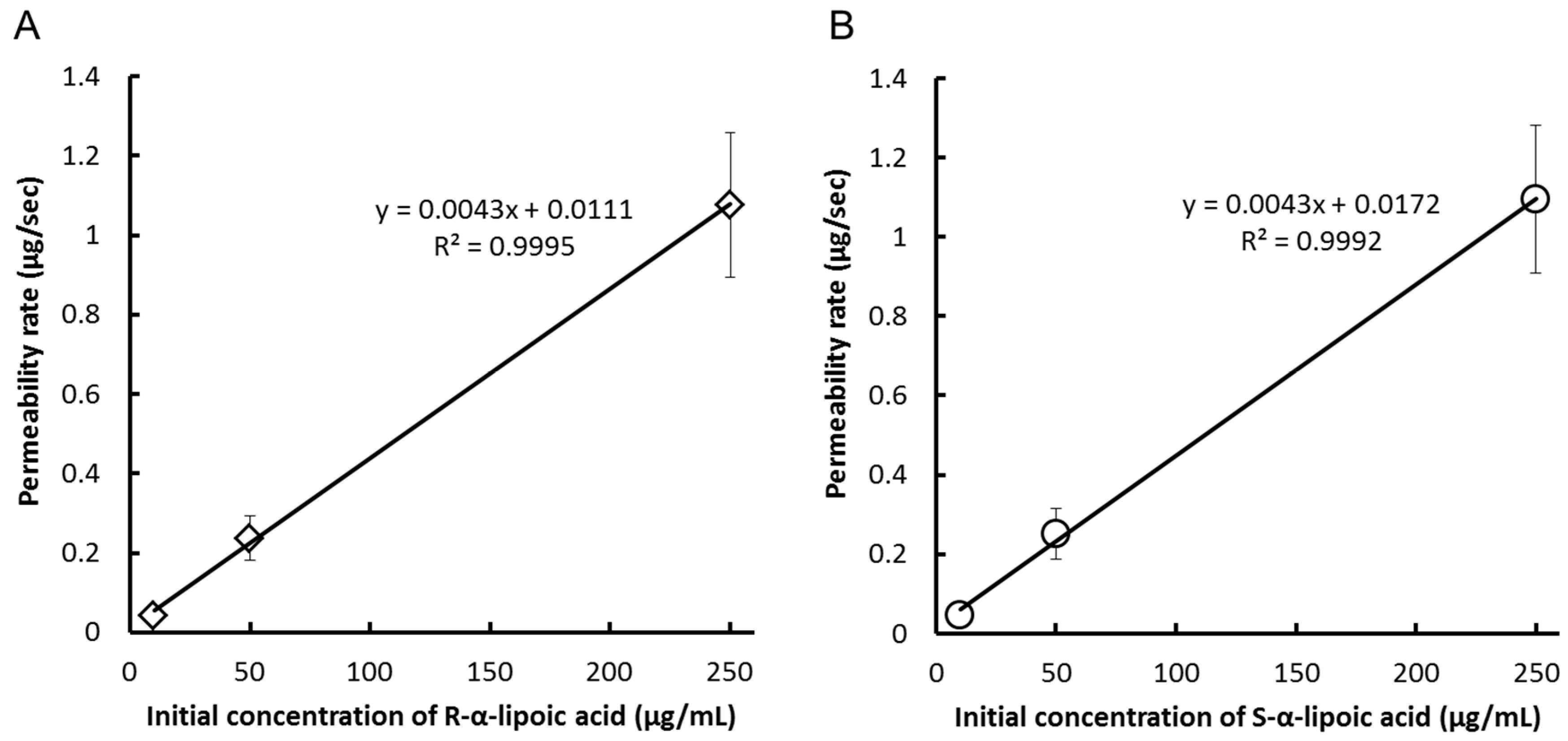

2. Results and Discussion

| Side | Time (min) | Concentrations (µg/mL) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low Group | Middle Group | High Group | |||||

| RLA | SLA | RLA | SLA | RLA | SLA | ||

| basal | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 15 | 0.06 ± 0.01 | 0.07 ± 0.01 | 0.36 ± 0.08 | 0.38 ± 0.10 | 1.61 ± 0.27 | 1.64 ± 0.28 | |

| 30 | 0.14 ± 0.01 | 0.15 ± 0.01 | 0.70 ± 0.09 | 0.73 ± 0.08 | 3.54 ± 0.39 | 3.66 ± 0.36 | |

| 60 | 0.27 ± 0.1 | 0.28 ± 0.01 | 1.28 ± 0.19 | 1.32 ± 0.20 | 7.09 ± 0.18 | 7.34 ± 0.14 | |

| 120 | 0.43 ± 0.02 * | 0.46 ± 0.02 | 2.35 ± 0.12 * | 2.47 ± 0.14 | 11.80 ± 0.38 | 12.19 ± 0.30 | |

| apical | 120 | 1.94 ± 0.04 | 2.02 ± 0.05 | 10.64 ± 0.12 | 11.05 ± 0.28 | 65.01 ± 4.04 | 67.56 ± 3.47 |

| Cell Types | Papp (×10−6 cm/s) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low Group | Middle Group | High Group | ||||

| RLA | SLA | RLA | SLA | RLA | SLA | |

| Caco-2 | 14.3 ± 2.2 | 15.4 ± 2.2 | 15.9 ± 3.7 | 16.7 ± 4.3 | 14.4 ± 2.4 | 14.6 ± 2.5 |

| Side | Time (min) | Concentrations (µg/mL) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low Group | Middle Group | High Group | |||||

| RLA | SLA | RLA | SLA | RLA | SLA | ||

| basal | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 15 | 0.90 ± 0.02 | 0.90 ± 0.03 | 4.90 ± 0.09 | 4.89 ± 0.10 | 23.00 ± 1.61 | 23.50 ± 1.65 | |

| 30 | 1.51 ± 0.03 | 1.52 ± 0.02 | 8.48 ± 0.57 | 8.57 ± 0.64 | 37.84 ± 2.21 | 38.79 ± 2.19 | |

| 60 | 2.33 ± 0.11 | 2.40 ± 0.12 | 12.82 ± 0.63 | 12.85 ± 0.68 | 58.44 ± 1.68 | 59.76 ± 1.73 | |

| 120 | 3.11 ± 0.17 | 3.04 ± 0.16 | 17.83 ± 1.20 | 17.74 ± 1.44 | 81.65 ± 2.68 | 83.69 ± 3.36 | |

| apical | 120 | 0.86 ± 0.01 | 0.84 ± 0.02 | 6.02 ± 0.77 | 5.74 ± 0.62 | 59.23 ± 1.36 | 60.17 ± 1.46 |

| Cell Types | Papp (×10−6 cm/s) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low Group | Middle Group | High Group | ||||

| RLA | SLA | RLA | SLA | RLA | SLA | |

| MDCK II | 185.4 ± 5.5 | 186.2 ± 4.6 | 197.3 ± 2.6 | 197.7 ± 2.0 | 186.3 ± 12.7 | 189.8 ± 13.9 |

3. Experimental Section

3.1. Chemical and Reagents

3.2. Cell Culture

3.2.1. Caco-2

3.2.2. MDCK II

3.3. Transport Experiments

3.3.1. Caco-2

3.3.2. MDCK II

3.4. Determination of LA Concentration by LC-MS/MS

3.5. Data Analysis

4. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Packer, L.; Witt, E.H.; Tritschler, H.J. Α-lipoic acid as a biological antioxidant. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 1995, 19, 227–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biewenga, G.P.; Haenen, G.R.; Bast, A. The pharmacology of the antioxidant lipoic acid. Gen. Pharmacol. 1997, 29, 315–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

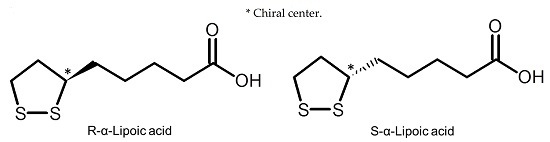

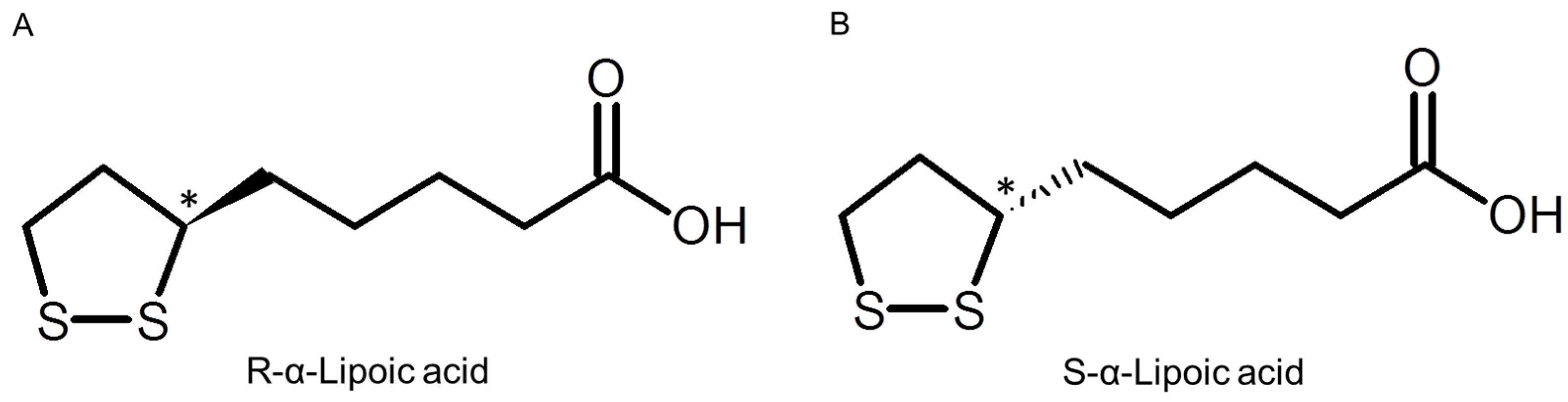

- Naito, Y.; Ikuta, N.; Okano, A.; Okamoto, H.; Nakata, D.; Terao, K.; Matsumoto, K.; Kajiwara, N.; Yasui, H.; Yoshikawa, Y. Isomeric effects of anti-diabetic α-lipoic acid with gamma-cyclodextrin. Life Sci. 2015, 136, 73–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koriyama, Y.; Nakayama, Y.; Matsugo, S.; Kato, S. Protective effect of lipoic acid against oxidative stress is mediated by Keap1/Nrf2-dependent heme oxygenase-1 induction in the RGC-5 cellline. Brain Res. 2013, 1499, 145–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Packer, L.; Kraemer, K.; Rimbach, G. Molecular aspects of lipoic acid in the prevention of diabetes complications. Nutrition 2001, 17, 888–895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grasso, S.; Bramanti, V.; Tomassoni, D.; Bronzi, D.; Malfa, G.; Traini, E.; Napoli, M.; Renis, M.; Amenta, F.; Avola, R. Effect of lipoic acid and α-glyceryl-phosphoryl-choline on astroglial cell proliferation and differentiation in primary culture. J. Neurosci. Res. 2014, 92, 86–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khanna, S.; Roy, S.; Packer, L.; Sen, C.K. Cytokine-induced glucose uptake in skeletal muscle: Redox regulation and the role of α-lipoic acid. Am. J. Physiol. 1999, 276, R1327–R1333. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Bramanti, V.; Tomassoni, D.; Bronzi, D.; Grasso, S.; Curro, M.; Avitabile, M.; Li Volsi, G.; Renis, M.; Ientile, R.; Amenta, F.; et al. Α-lipoic acid modulates GFAP, vimentin, nestin, cyclin D1 and MAP-kinase expression in astroglial cell cultures. Neurochem. Res. 2010, 35, 2070–2077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kramer, K.; Packer, L. R-α-lipoic acid. Oxid. Stress Dis. 2001, 6, 129–164. [Google Scholar]

- Niebch, G.; Buchele, B.; Blome, J.; Grieb, S.; Brandt, G.; Kampa, P.; Raffel, H.H.; Locher, M.; Borbe, H.O.; Nubert, I.; et al. Enantioselective high-performance liquid chromatography assay of (+)R- and (−)S-α-lipoic acid in human plasma. Chirality 1997, 9, 32–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hermann, R.; Niebch, G.; Borbe, H.O.; Fieger-Büschges, H.; Ruus, P.; Nowak, H.; Riethmüller-Winzen, H.; Peukert, M.; Blume, H. Enantioselective pharmacokinetics and bioavailability of different racemic α-lipoic acid formulations in healthy volunteers. Eur. J. Pharm. Sci. 1996, 4, 167–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breithaupt-Grogler, K.; Niebch, G.; Schneider, E.; Erb, K.; Hermann, R.; Blume, H.H.; Schug, B.S.; Belz, G.G. Dose-proportionality of oral thioctic acid—Coincidence of assessments via pooled plasma and individual data. Eur. J. Pharm. Sci. 1999, 8, 57–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Streeper, R.S.; Henriksen, E.J.; Jacob, S.; Hokama, J.Y.; Fogt, D.L.; Tritschler, H.J. Differential effects of lipoic acid stereoisomers on glucose metabolism in insulin-resistant skeletal muscle. Am. J. Physiol. 1997, 273, E185–E191. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Hagen, T.M.; Ingersoll, R.T.; Lykkesfeldt, J.; Liu, J.; Wehr, C.M.; Vinarsky, V.; Bartholomew, J.C.; Ames, A.B. (R)-α-lipoic acid-supplemented old rats have improved mitochondrial function, decreased oxidative damage, and increased metabolic rate. FASEB J. 1999, 13, 411–418. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Uchida, R.; Okamoto, H.; Ikuta, N.; Terao, K.; Hirota, T. Enantioselective pharmacokinetics of α-lipoic acid in rats. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2015, 16, 22781–22794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Artursson, P.; Karlsson, J. Correlation between oral drug absorption in humans and apparent drug permeability coefficients in human intestinal epithelial (ca@Co-2) cells. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1991, 175, 880–885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yee, S. In vitro permeability across Caco-2 cells (colonic) can predict in vivo (small intestinal) absorption in man—Fact or myth. Pharm. Res. 1997, 14, 763–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maubon, N.; le Vee, M.; Fossati, L.; Audry, M.; le Ferrec, E.; Bolze, S.; Fardel, O. Analysis of drug transporter expression in human intestinal caco-2 cells by real-time PCR. Fundam. Clin. Pharmacol. 2007, 21, 659–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Englund, G.; Rorsman, F.; Ronnblom, A.; Karlbom, U.; Lazorova, L.; Grasjo, J.; Kindmark, A.; Artursson, P. Regional levels of drug transporters along the human intestinal tract: Co-expression of ABC and SLC transporters and comparison with Caco-2 cells. Eur. J. Pharm. Sci. 2006, 29, 269–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takaishi, N.; Yoshida, K.; Satsu, H.; Shimizu, M. Transepithelial transport of α-lipoic acid across human intestinal Caco-2 cell monolayers. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2007, 55, 5253–5259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Irvine, J.D.; Takahashi, L.; Lockhart, K.; Cheong, J.; Tolan, J.W.; Selick, H.E.; Grove, J.R. Mdck (Madin-Darby canine kidney) cells: A tool for membrane permeability screening. J. Pharm. Sci. 1999, 88, 28–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Di, L.; Whitney-Pickett, C.; Umland, J.P.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, X.; Gebhard, D.F.; Lai, Y.; Federico, J.J., 3rd; Davidson, R.E.; Smith, R.; et al. Development of a new permeability assay using low-efflux MDCKII cells. J. Pharm. Sci. 2011, 100, 4974–4985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cho, M.J.; Thompson, D.P.; Cramer, C.T.; Vidmar, T.J.; Scieszka, J.F. The madin darby canine kidney (MDCK) epithelial cell monolayer as a model cellular transport barrier. Pharm. Res. 1989, 6, 71–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Volpe, D.A. Variability in Caco-2 and mdck cell-based intestinal permeability assays. J. Pharm. Sci. 2008, 97, 712–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prasad, P.D.; Wang, H.; Huang, W.; Fei, Y.J.; Leibach, F.H.; Devoe, L.D.; Ganapathy, V. Molecular and functional characterization of the intestinal Na+-dependent multivitamin transporter. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 1999, 366, 95–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paroder, V.; Spencer, S.R.; Paroder, M.; Arango, D.; Schwartz, S., Jr.; Mariadason, J.M.; Augenlicht, L.H.; Eskandari, S.; Carrasco, N. Na+/monocarboxylate transport (SMCT) protein expression correlates with survival in colon cancer: Molecular characterization of SMCT. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2006, 103, 7270–7275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pan, G.; Elmquist, W.F. Mitoxantrone permeability in mdckii cells is influenced by active influx transport. Mol. Pharm. 2007, 4, 475–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

© 2016 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons by Attribution (CC-BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Uchida, R.; Okamoto, H.; Ikuta, N.; Terao, K.; Hirota, T. Investigation of Enantioselective Membrane Permeability of α-Lipoic Acid in Caco-2 and MDCKII Cell. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2016, 17, 155. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms17020155

Uchida R, Okamoto H, Ikuta N, Terao K, Hirota T. Investigation of Enantioselective Membrane Permeability of α-Lipoic Acid in Caco-2 and MDCKII Cell. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2016; 17(2):155. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms17020155

Chicago/Turabian StyleUchida, Ryota, Hinako Okamoto, Naoko Ikuta, Keiji Terao, and Takashi Hirota. 2016. "Investigation of Enantioselective Membrane Permeability of α-Lipoic Acid in Caco-2 and MDCKII Cell" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 17, no. 2: 155. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms17020155

APA StyleUchida, R., Okamoto, H., Ikuta, N., Terao, K., & Hirota, T. (2016). Investigation of Enantioselective Membrane Permeability of α-Lipoic Acid in Caco-2 and MDCKII Cell. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 17(2), 155. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms17020155