Research Progress on Triarylmethyl Radical-Based High-Efficiency OLED

Abstract

1. Introduction

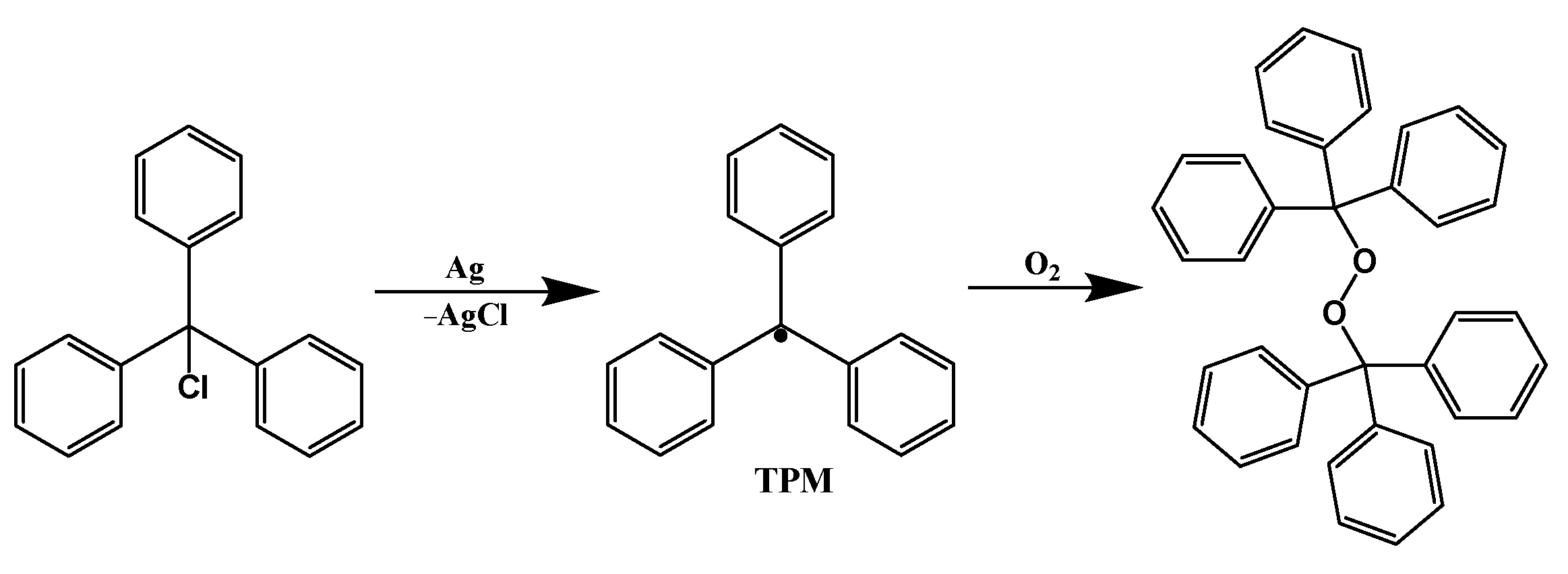

2. Introduction to OLED

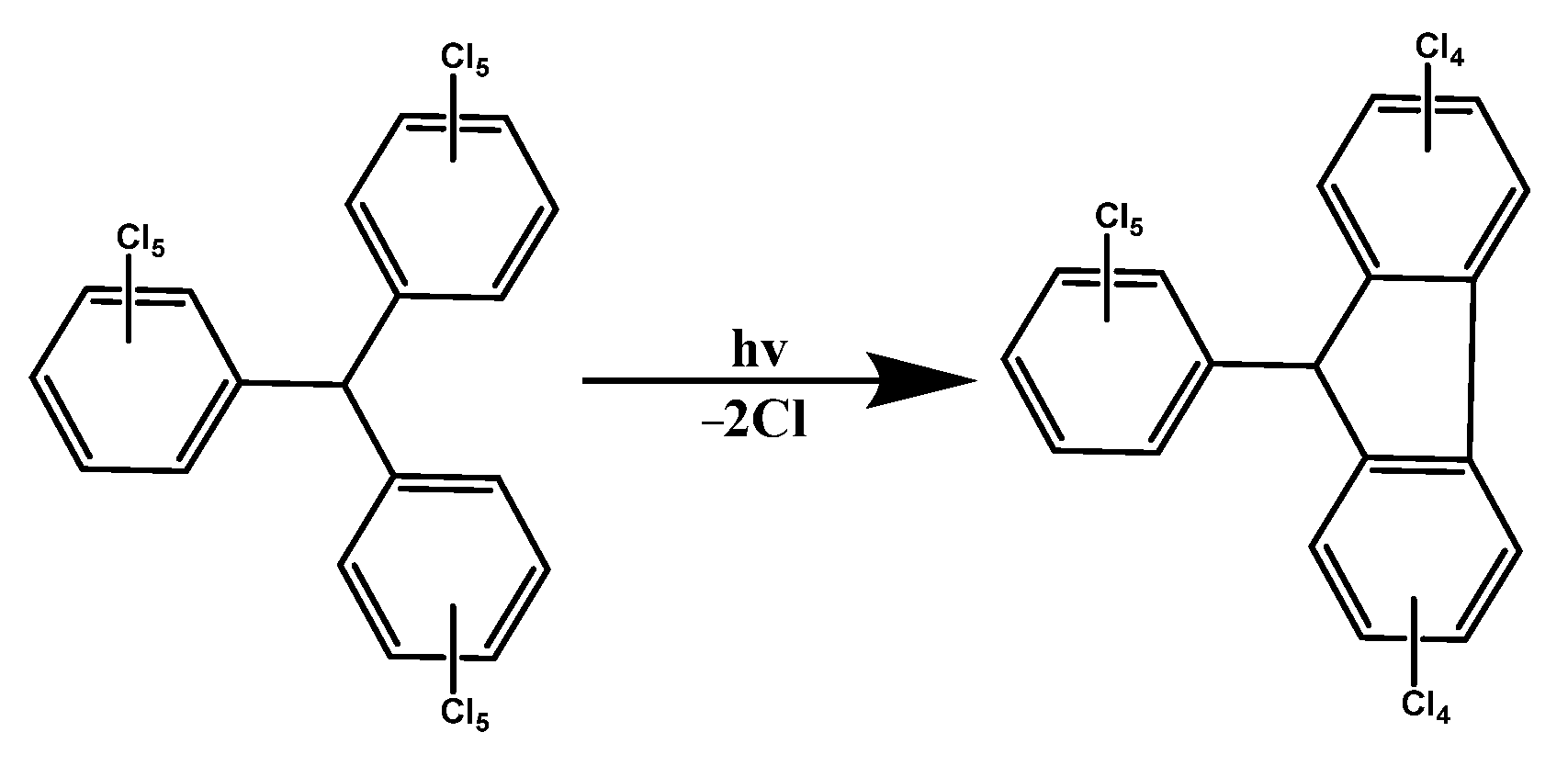

2.1. OLED’s Working Principle and Material Structure Composition

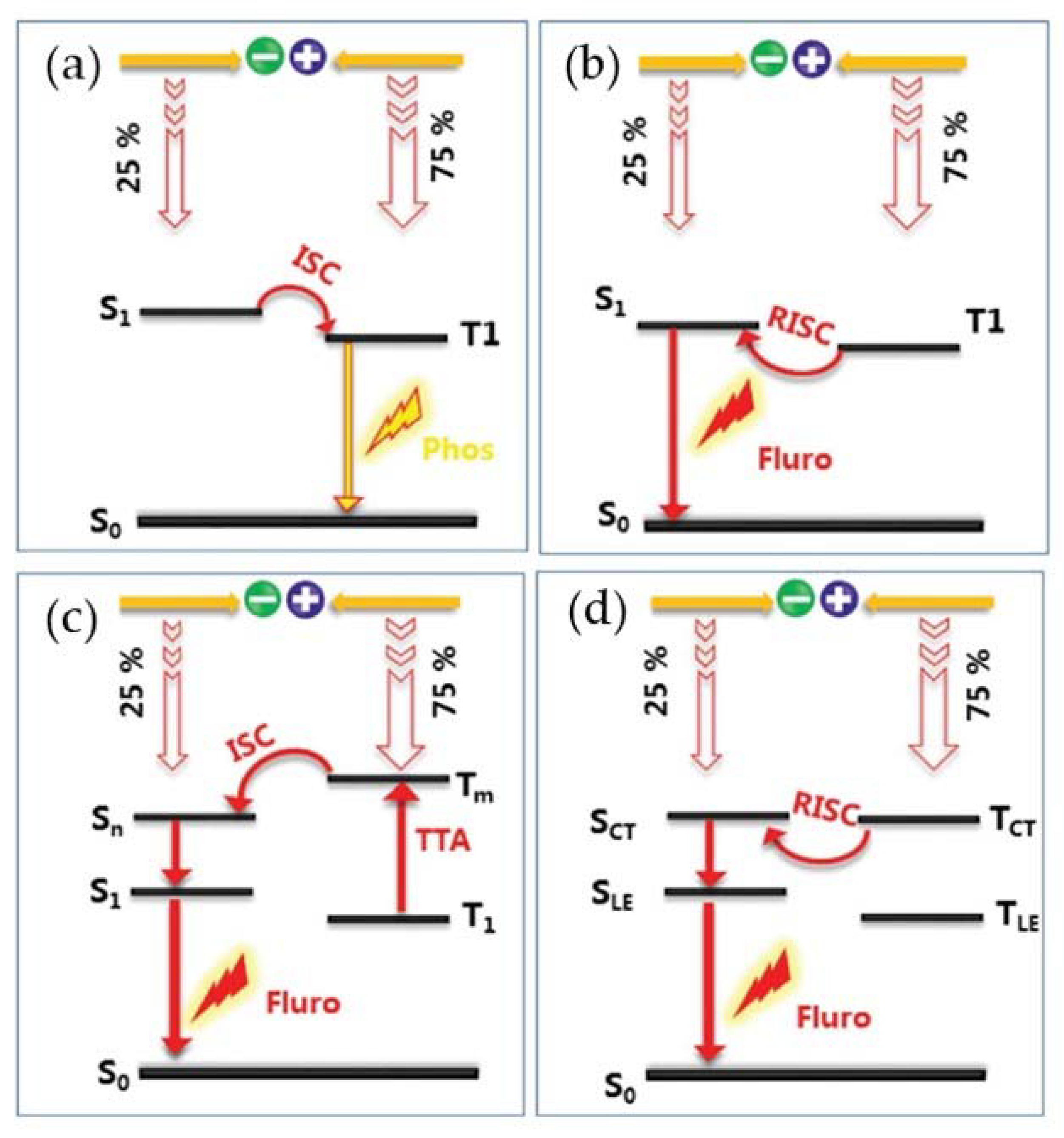

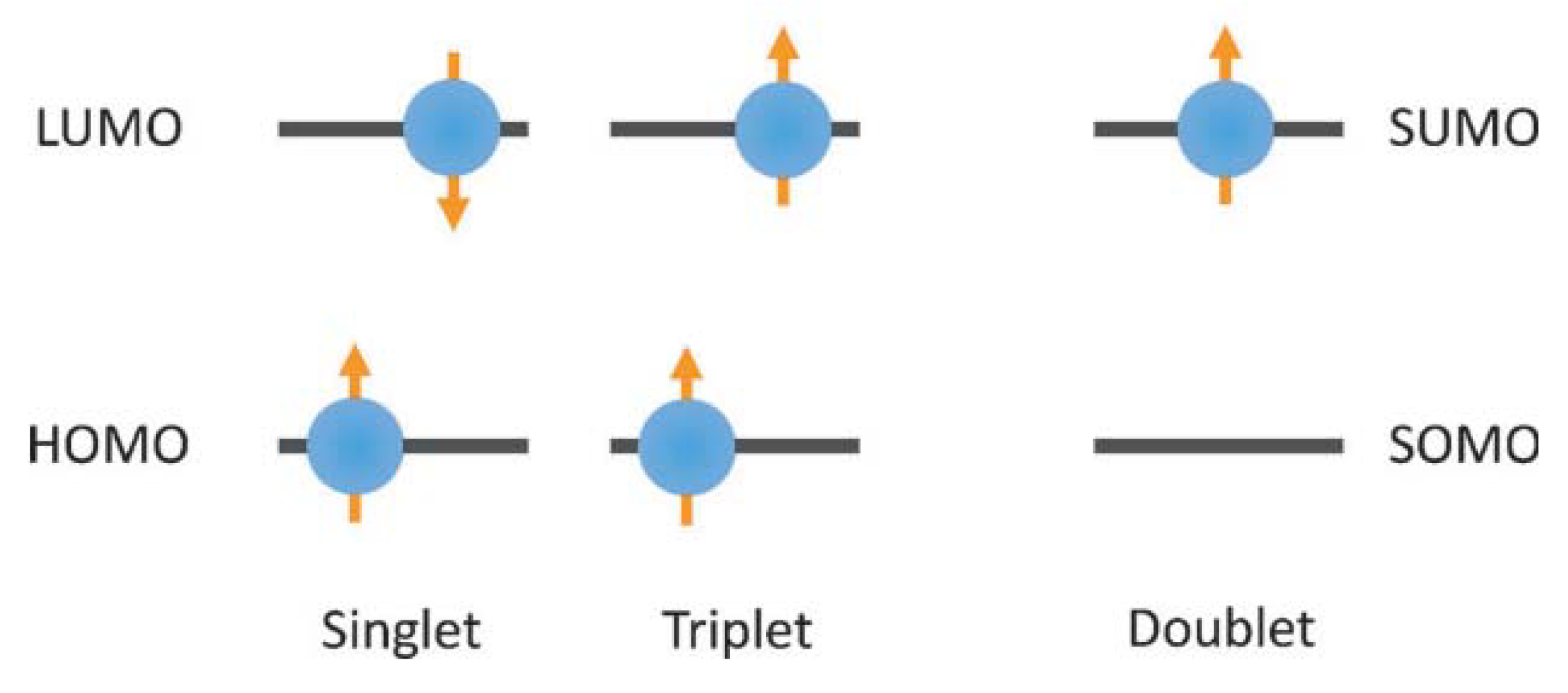

2.2. Classification of OLED Lighting Methods

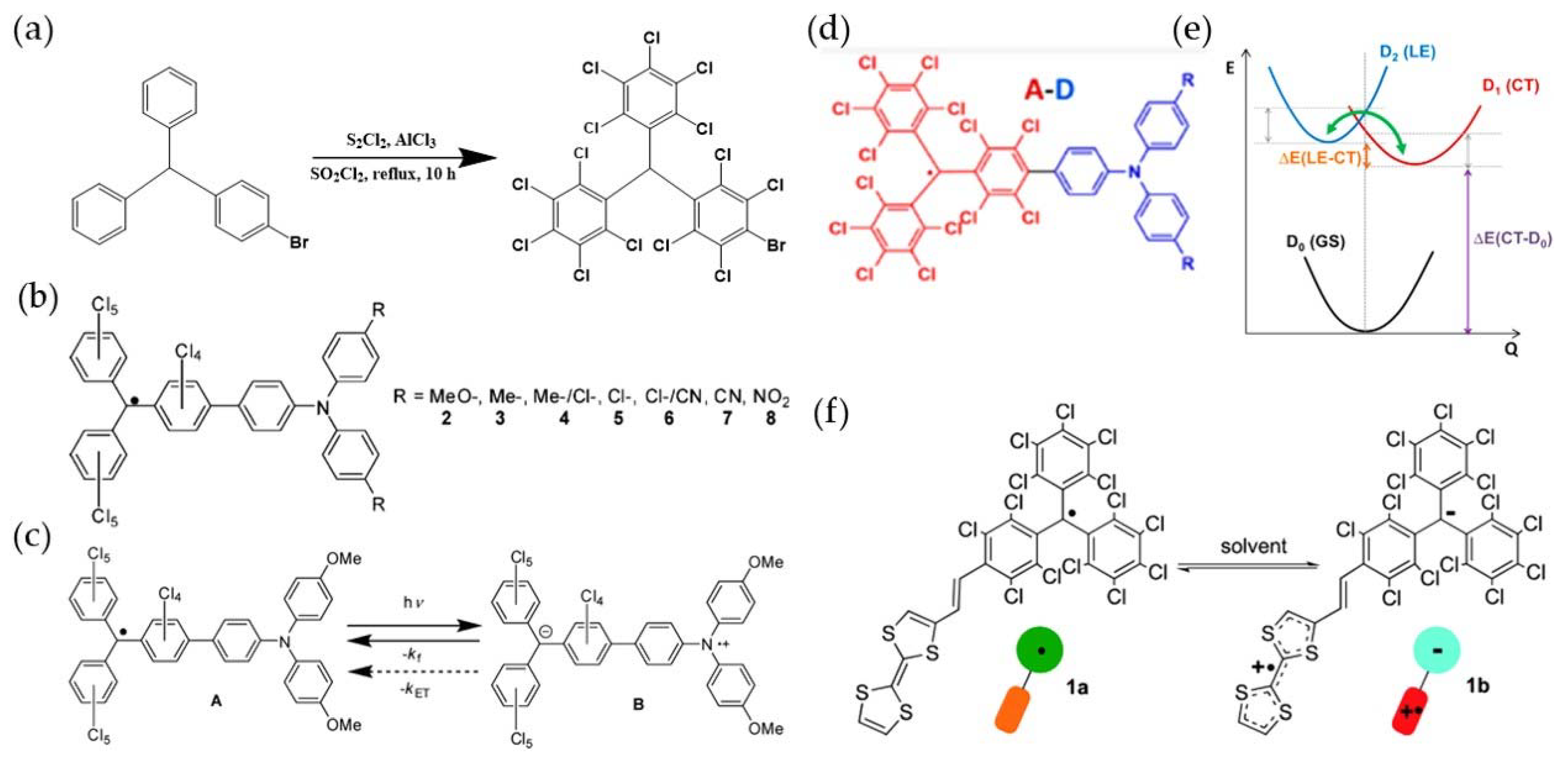

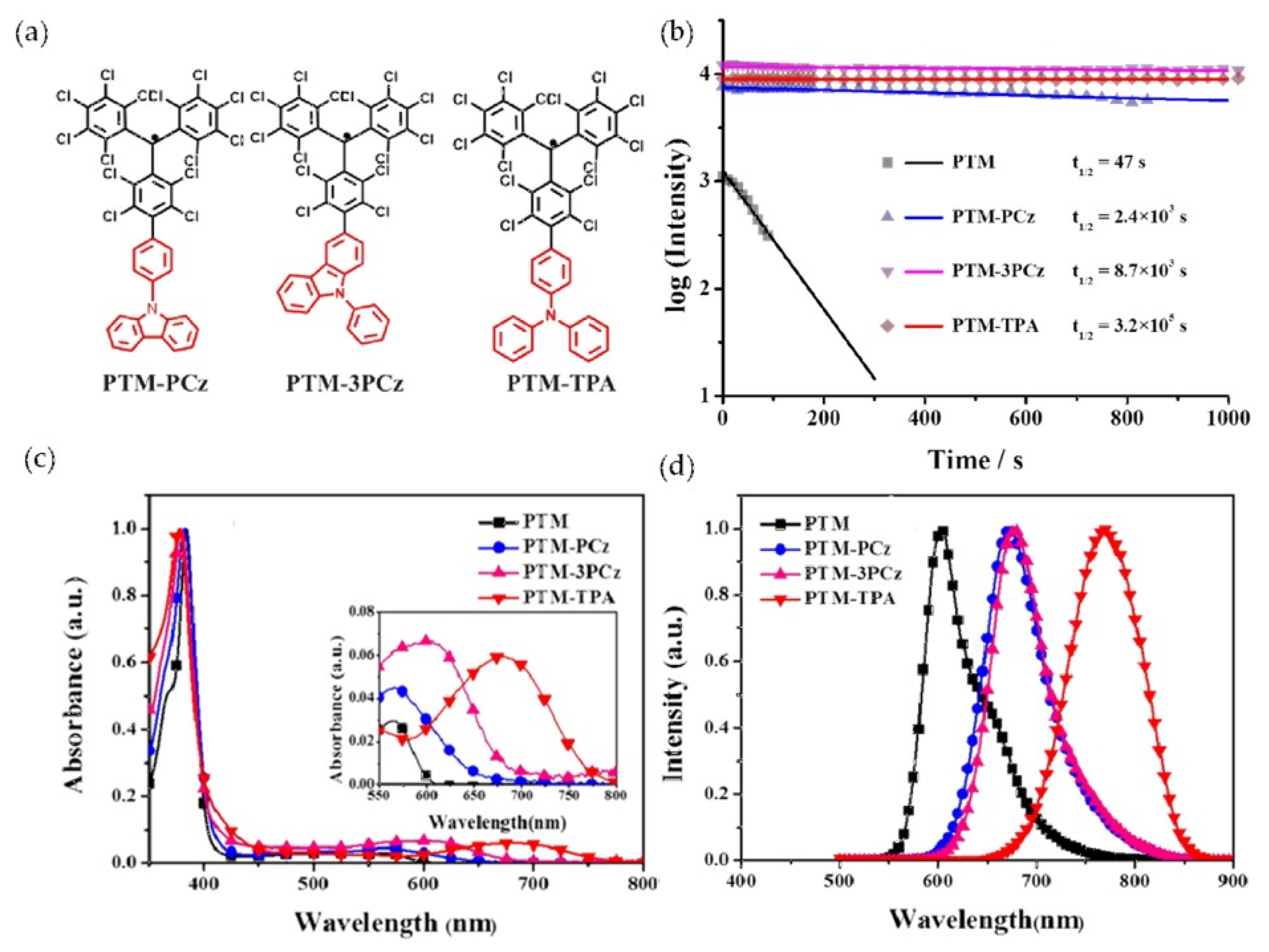

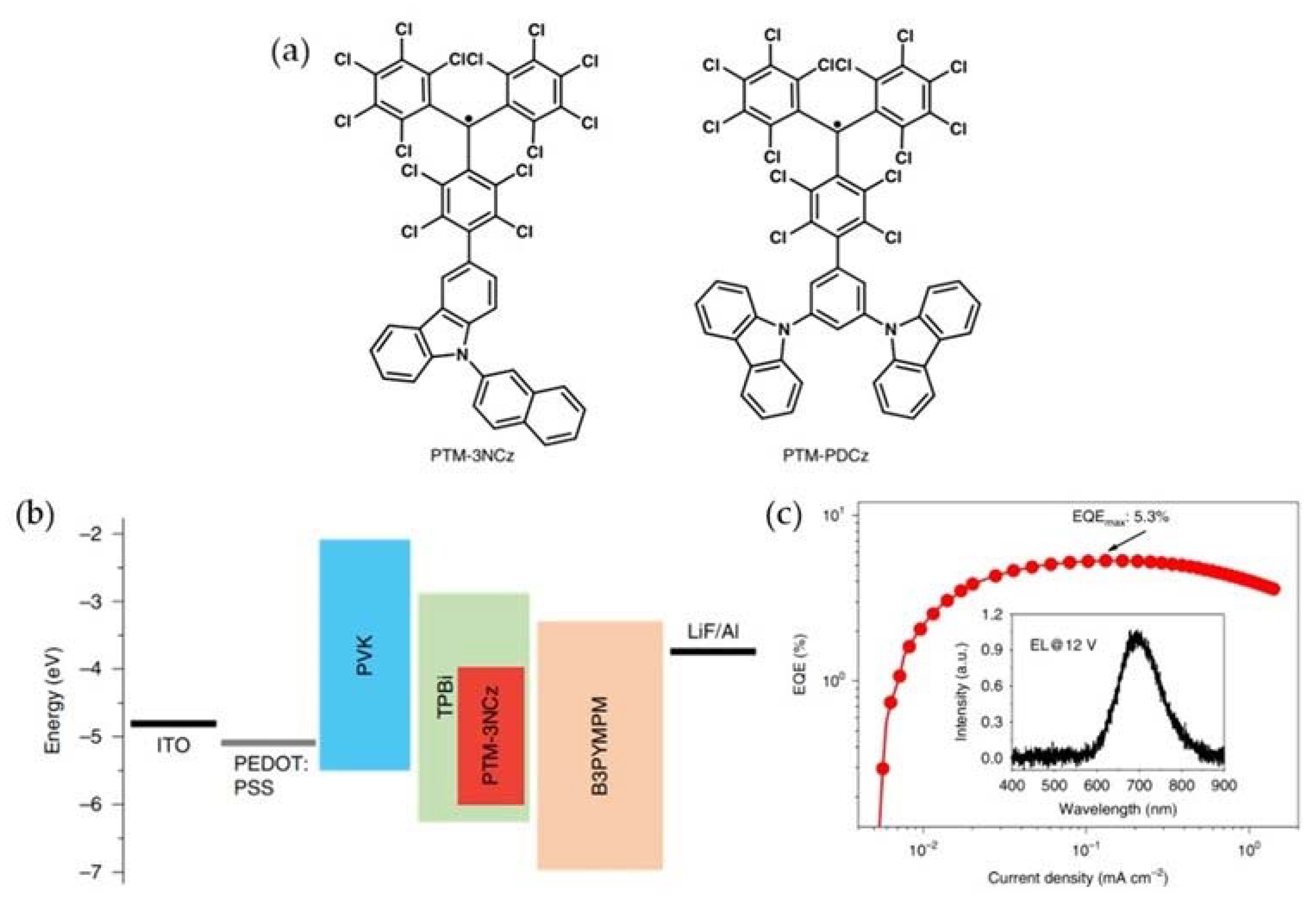

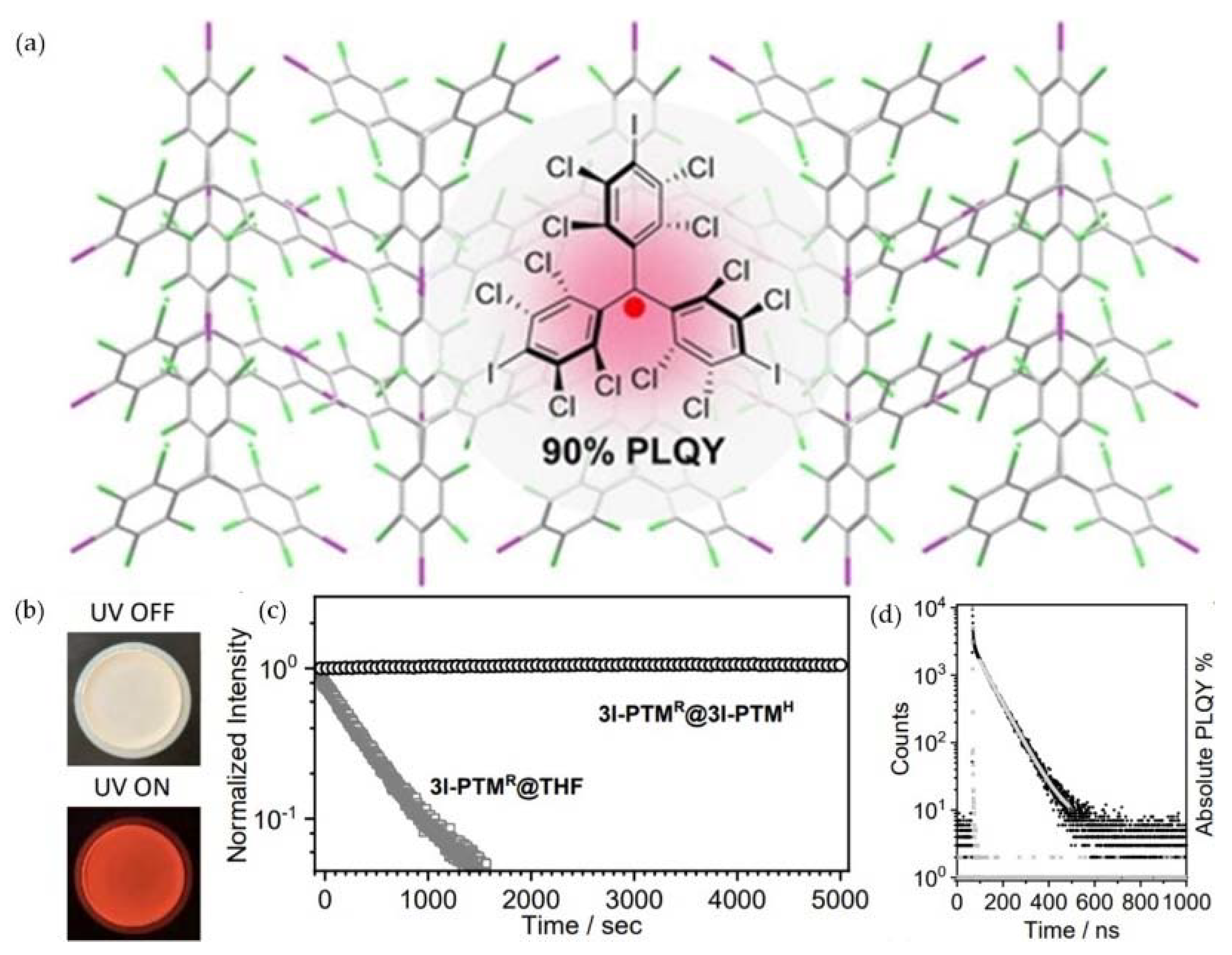

3. PTM-Based Luminescent Organic Radicals

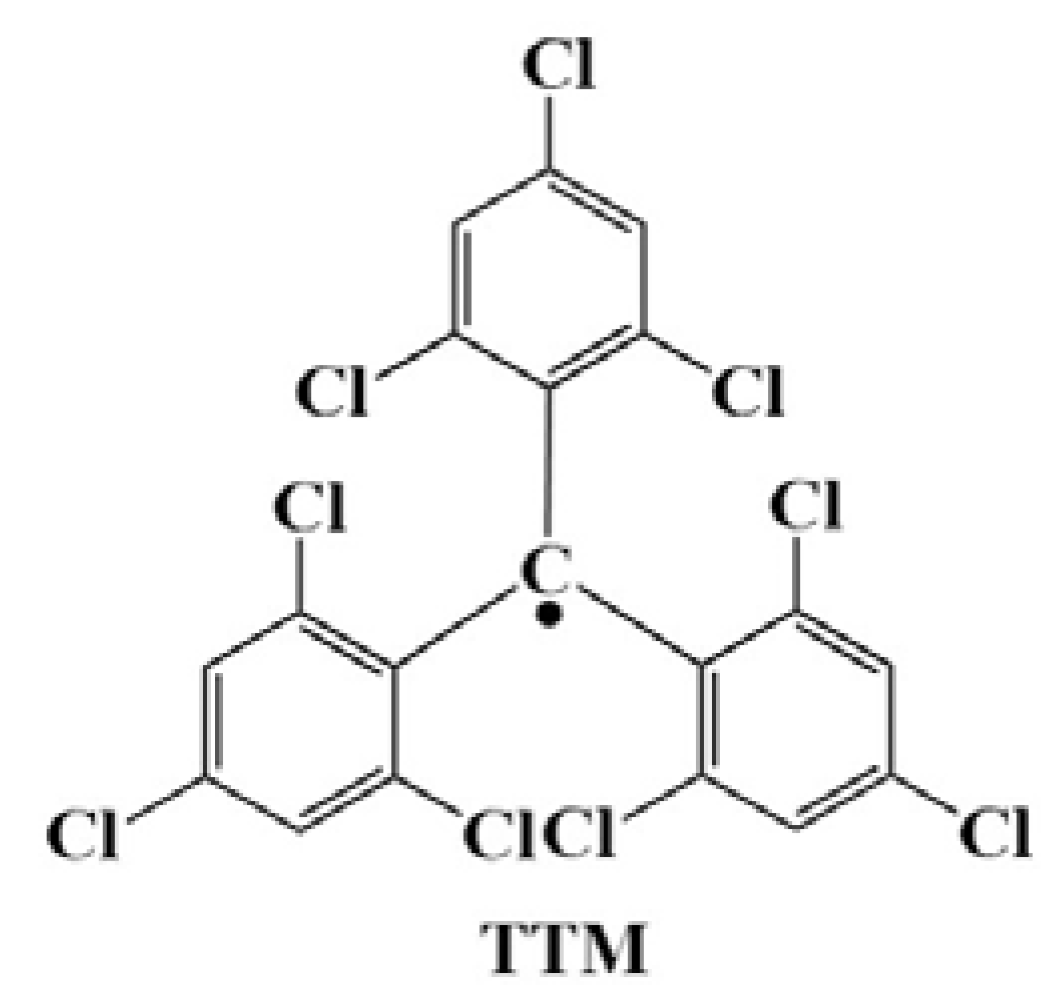

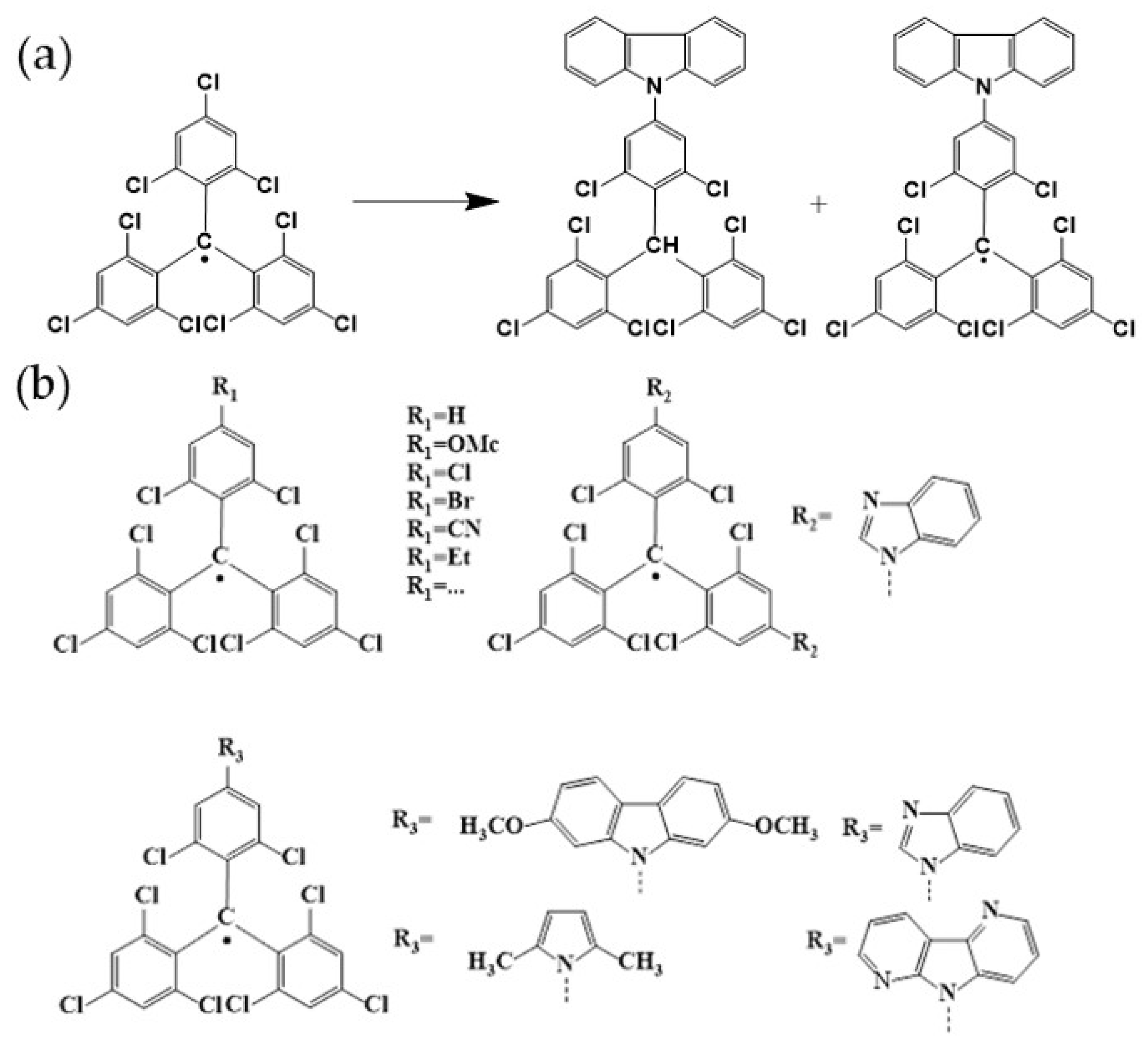

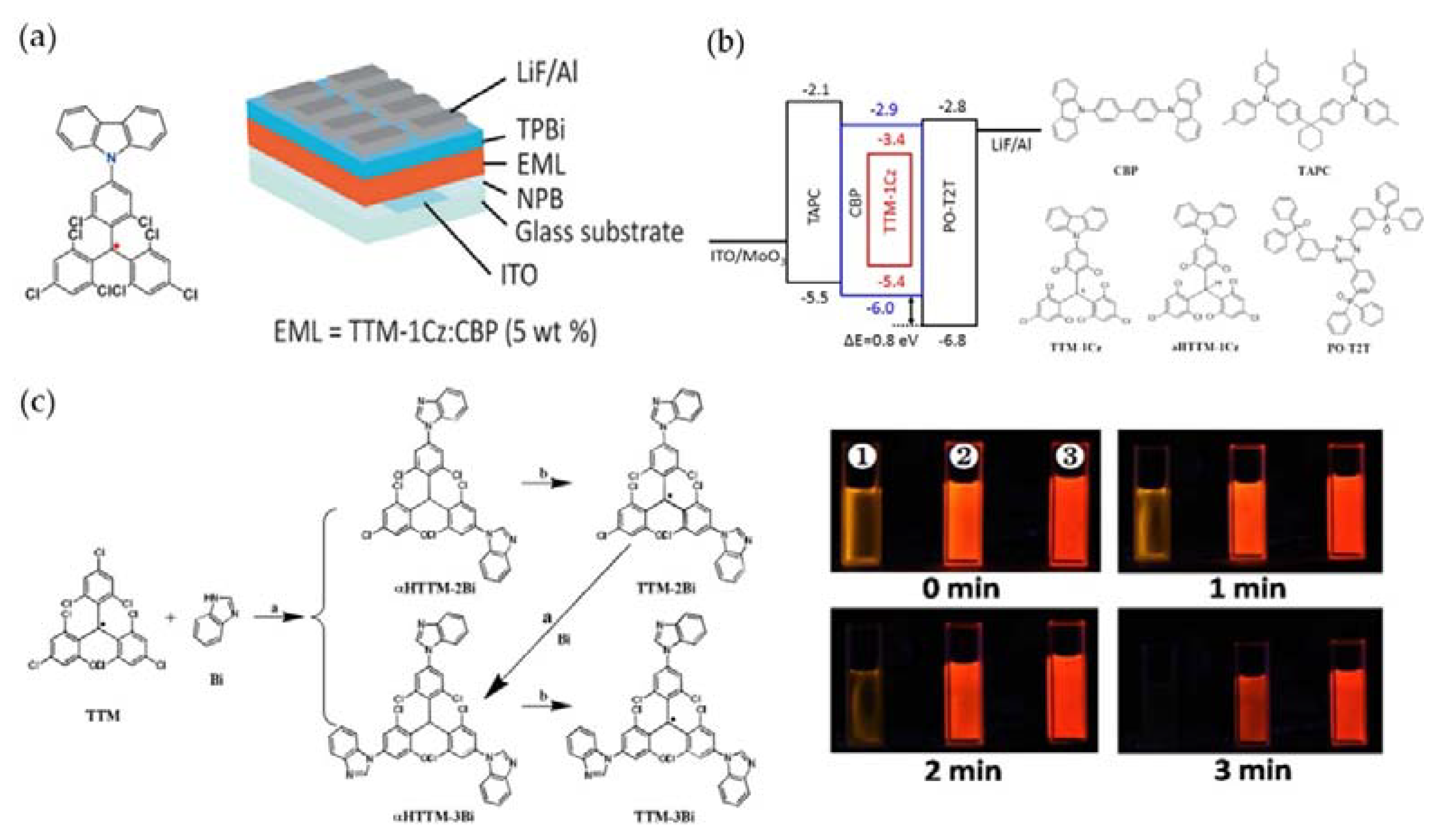

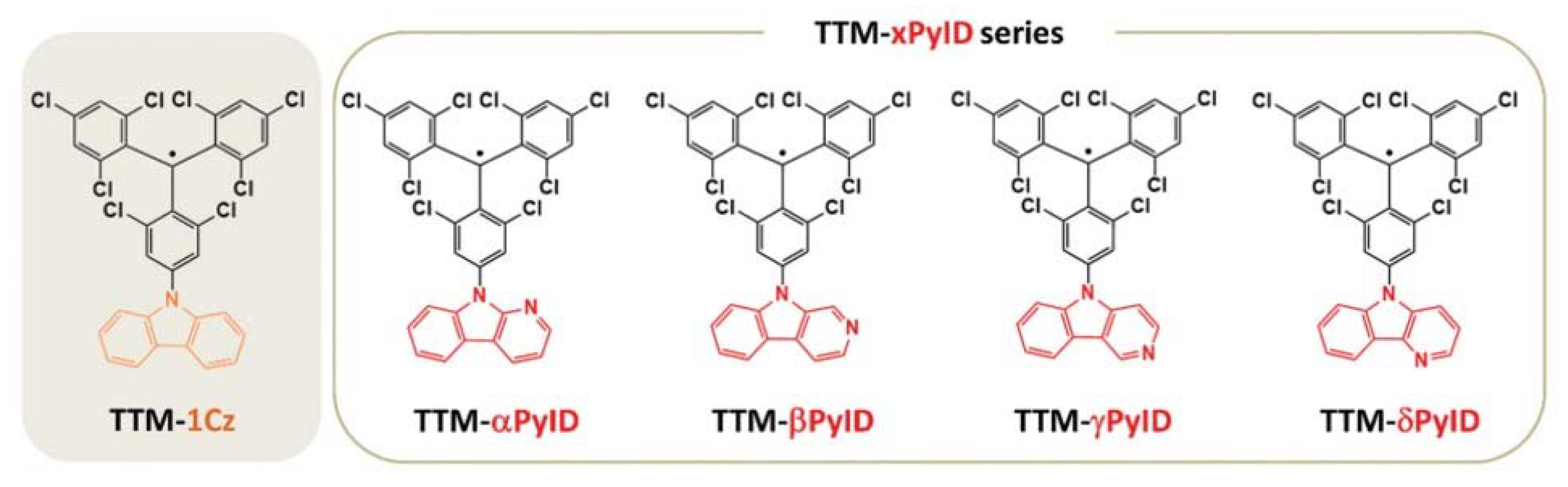

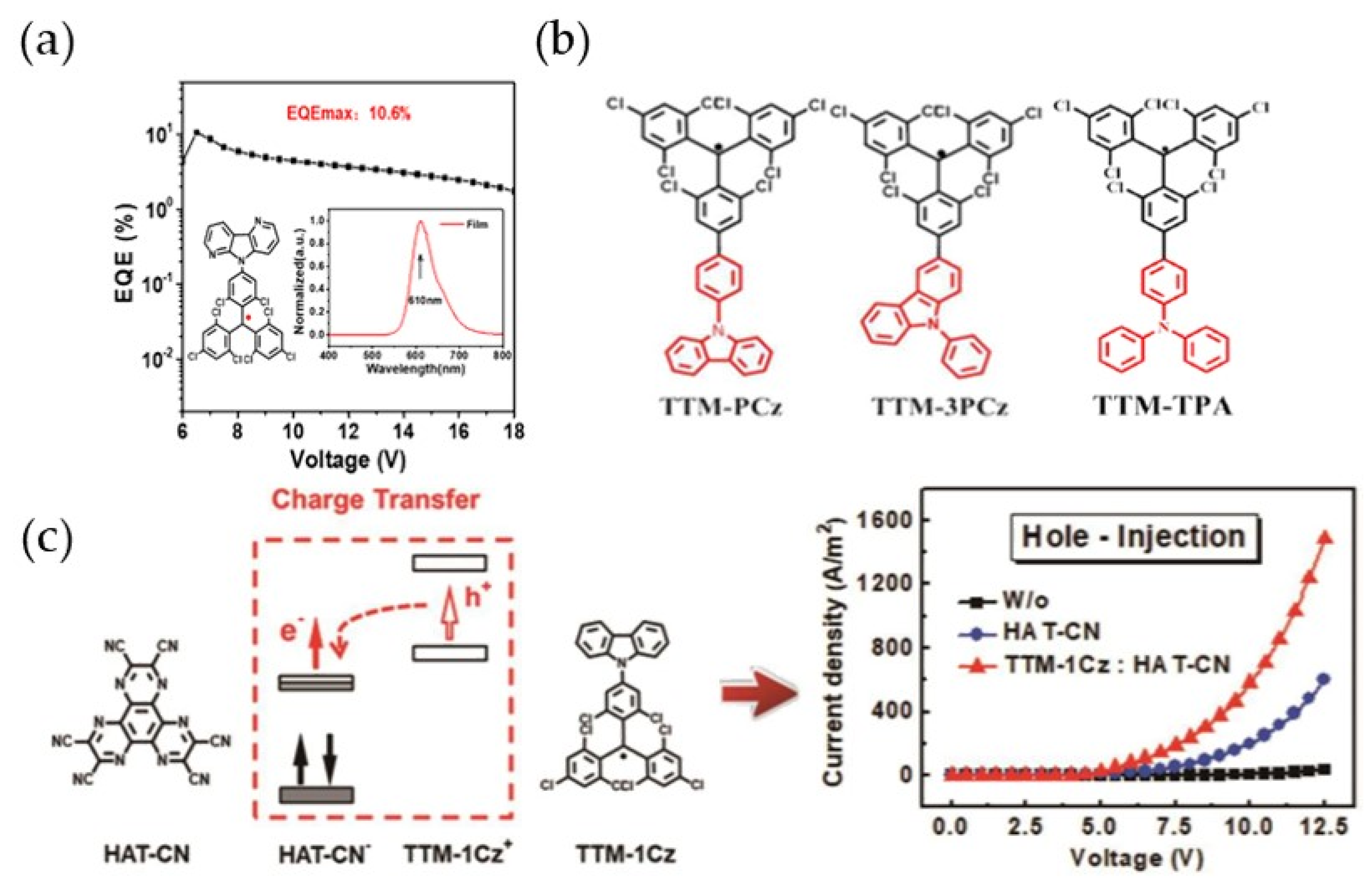

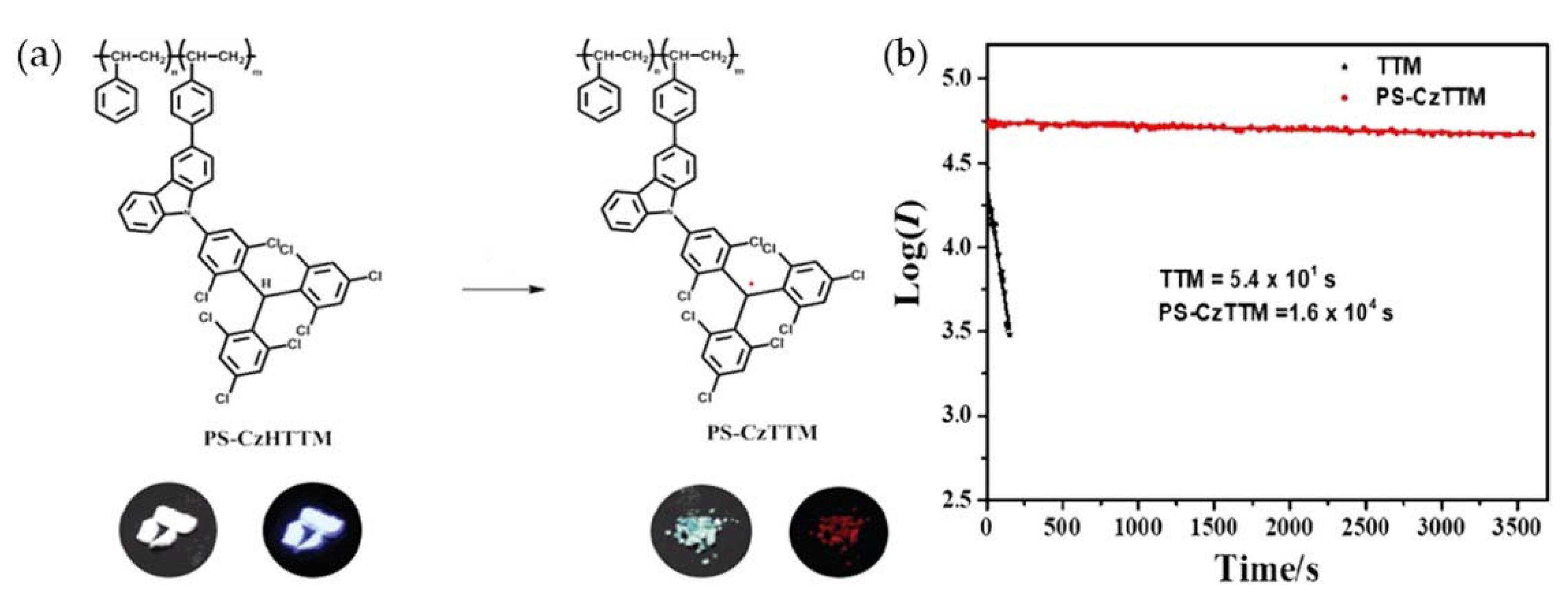

4. TTM-Based Luminescent Organic Radicals

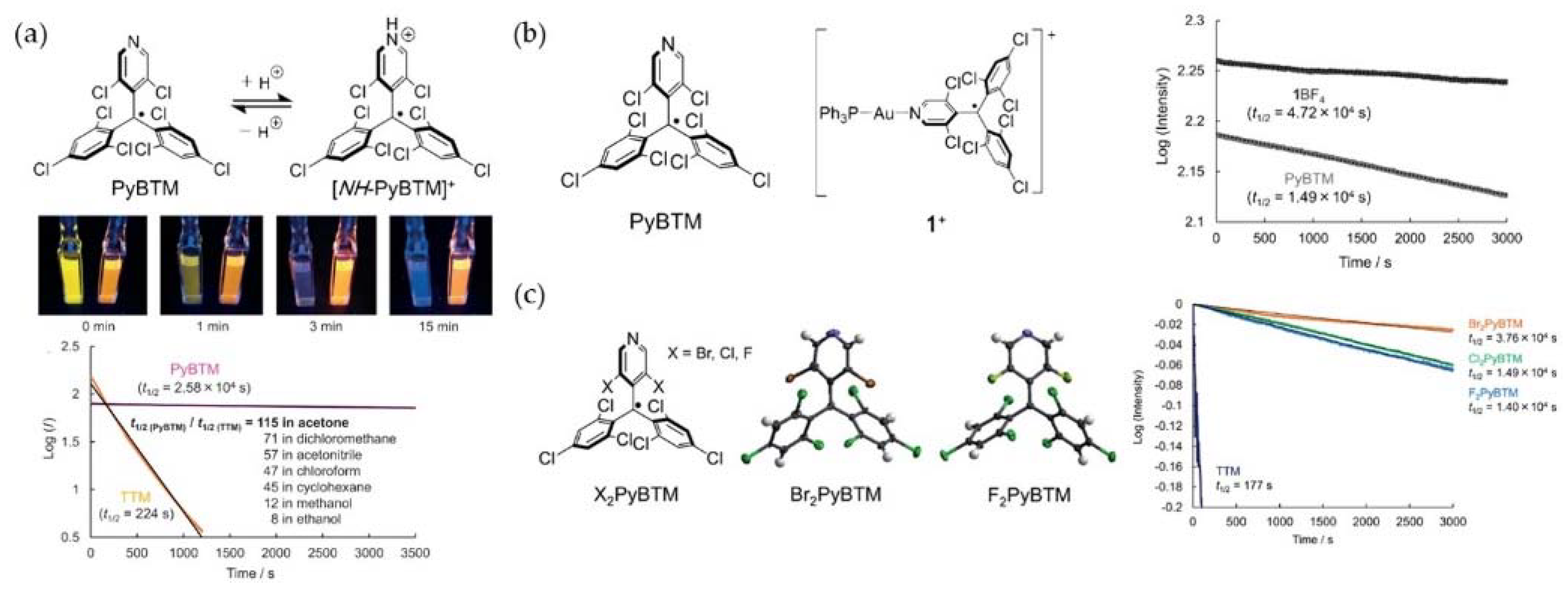

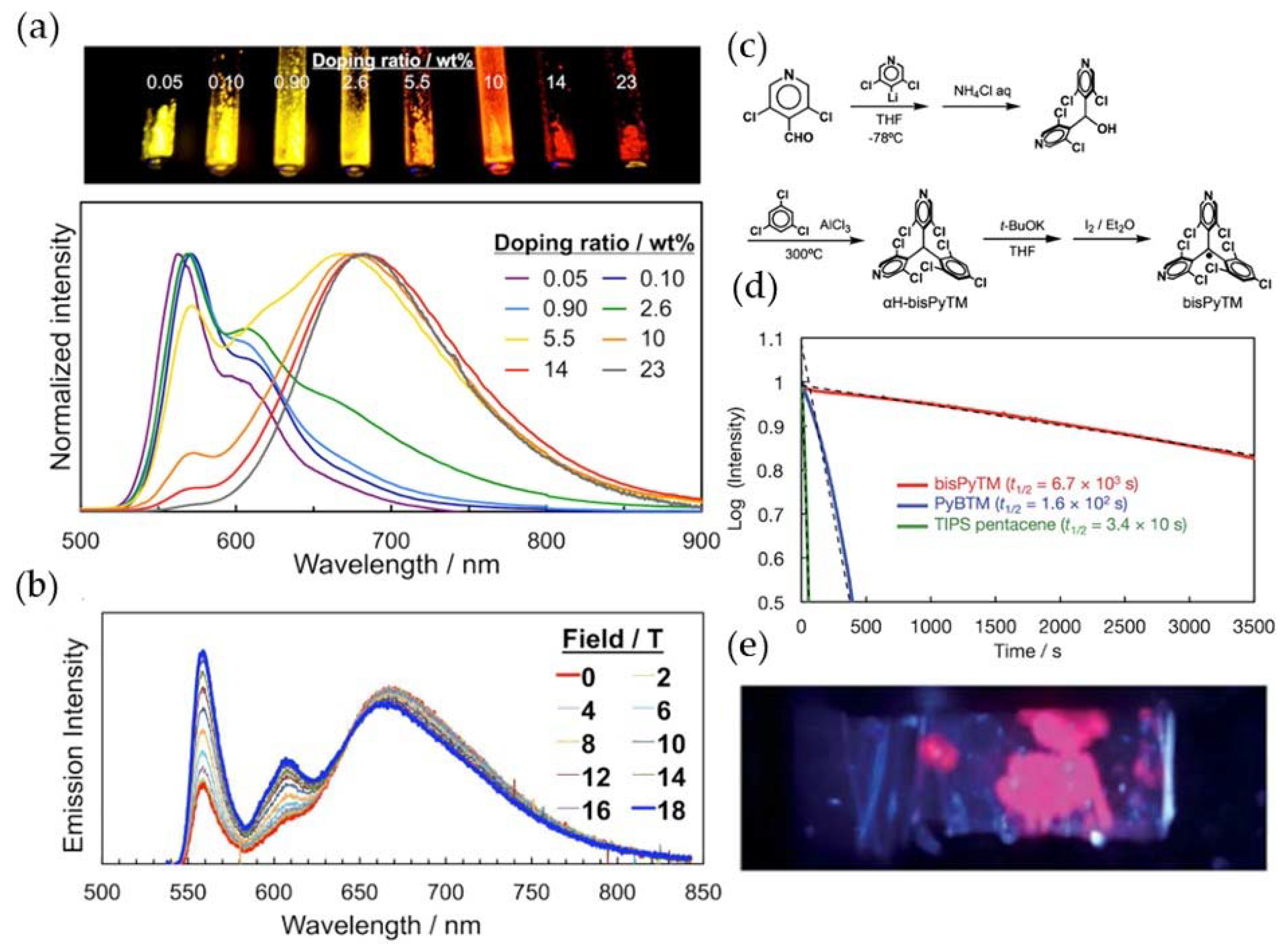

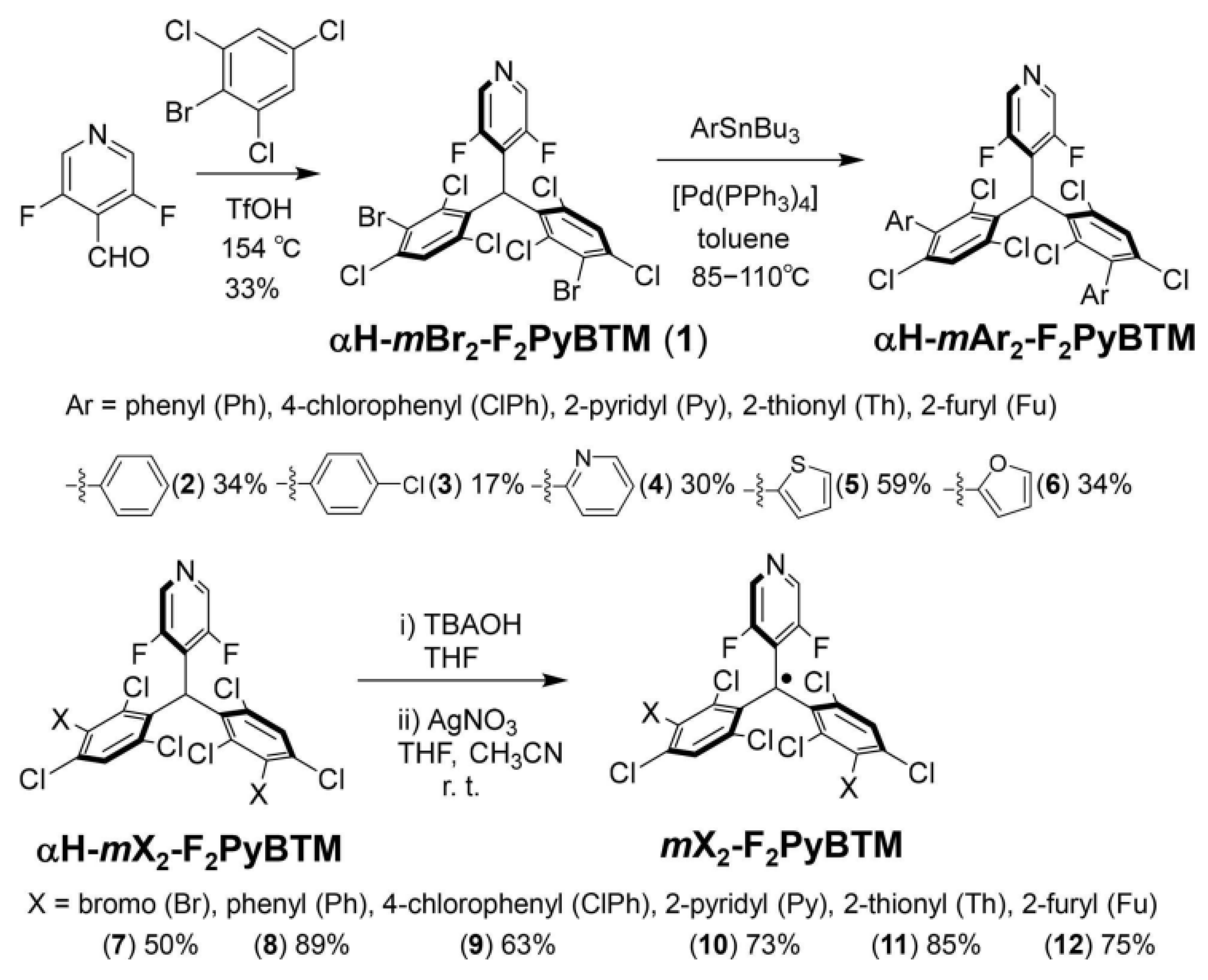

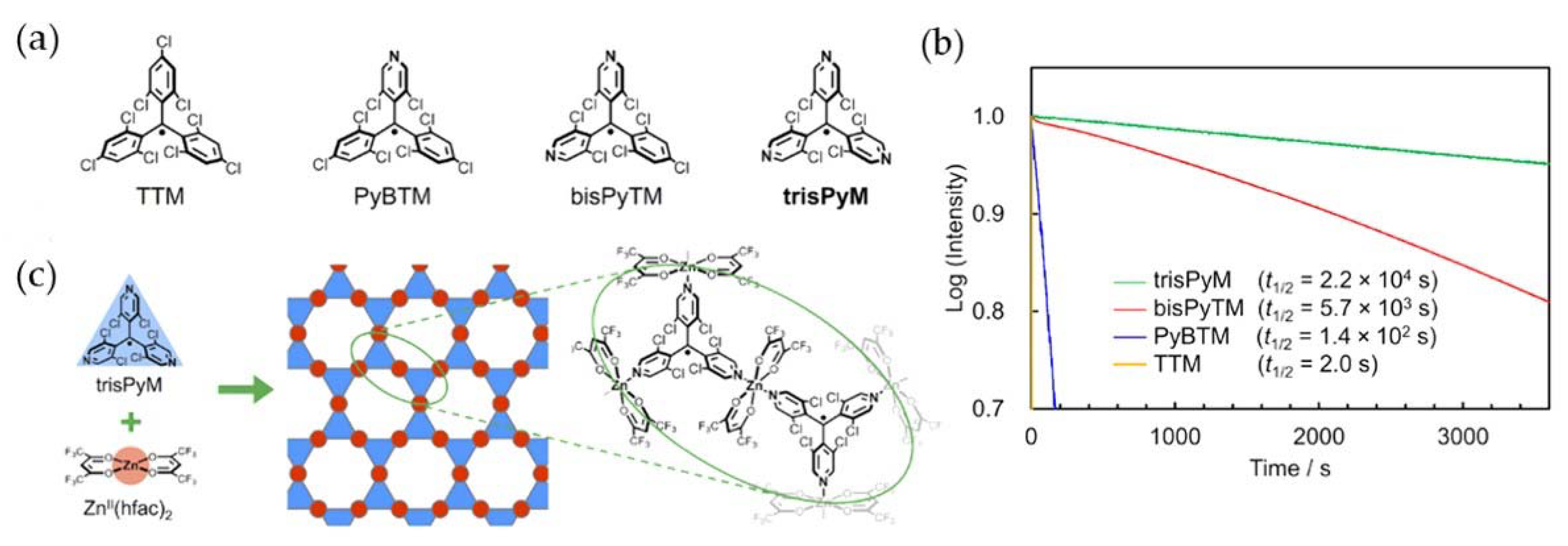

5. PyBTM-Based Luminescent Organic Radicals

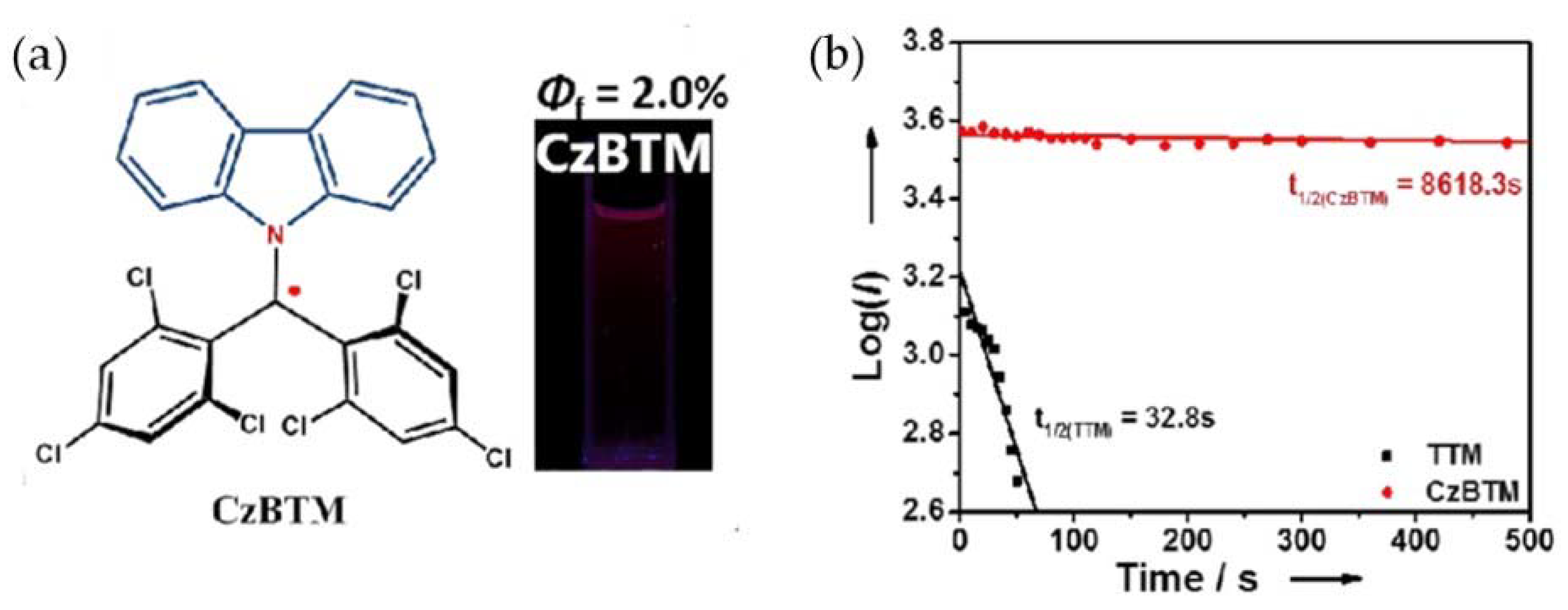

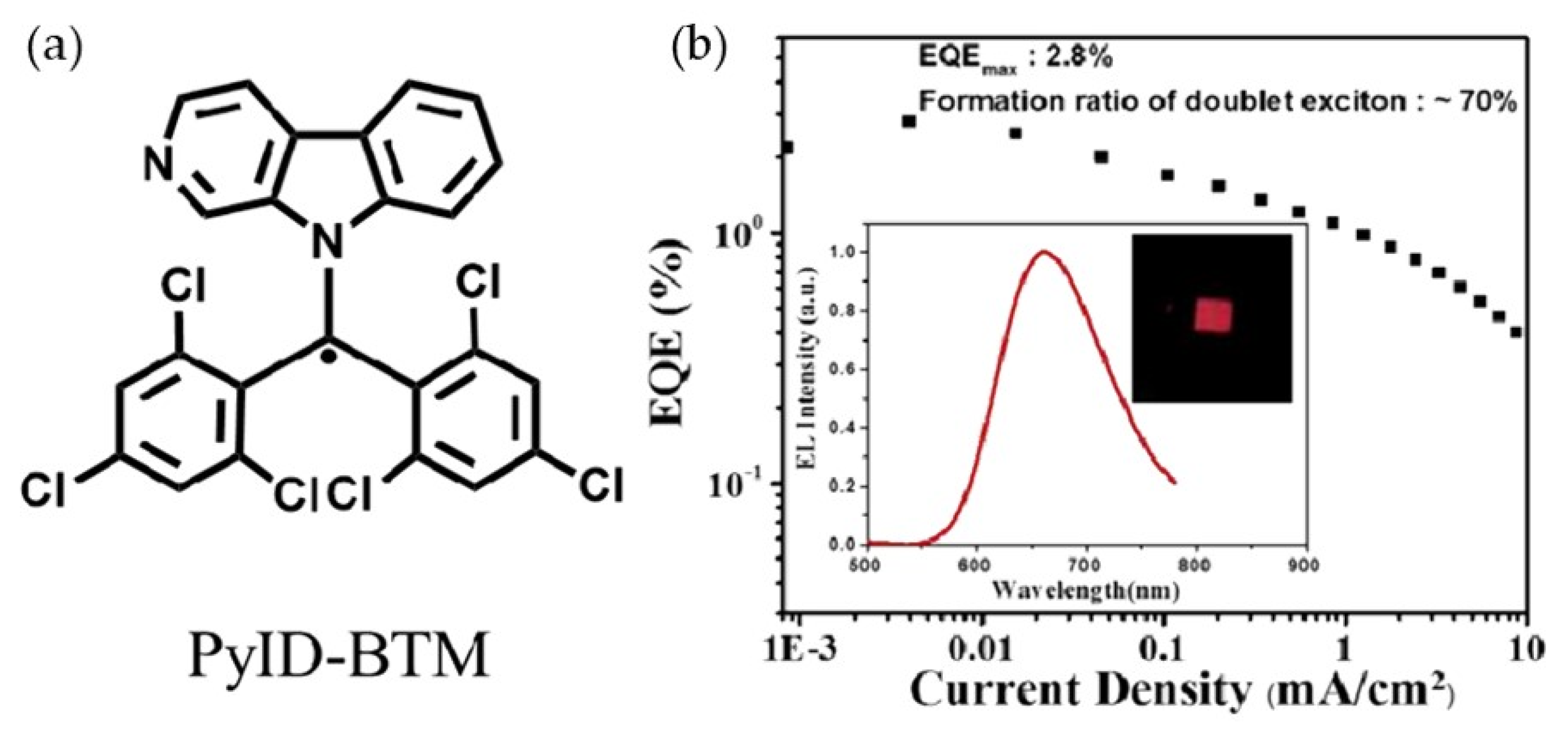

6. CzBTM-Based Luminescent Organic Radicals

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hayeck, N.; Mussa, I.; Perrier, S.; George, C. Production of peroxy radicals from the photochemical reaction of fatty acids at the air–water interface. ACS Earth Space Chem. 2020, 4, 1247–1253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ao, C.; Ruan, S.; He, W.; He, C.; Xu, K.; Zhang, L. Theoretical investigation of chemical reaction kinetics of CO2 and vinyl radical under catalytic combustion. Fuel 2021, 305, 121566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, Y.; Jasper, A.W.; Georgievskii, Y.; Klippenstein, S.J.; Sivaramakrishnan, R. Termolecular chemistry facilitated by radical-radical recombinations and its impact on flame speed predictions. Proc. Combust. Inst. 2021, 38, 515–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergwik, J.; Akerstrom, B. α1-Microglobulin binds Illuminated flavins and has a protective effect against sublethal riboflavin-induced damage in retinal epithelial cells. Front. Physiol. 2020, 11, 295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Di Meo, S.; Venditti, P. Evolution of the knowledge of free radicals and other oxidants. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longevity 2020, 2020, 9829176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hui, Y.; Wen, S.; Lihong, W.; Chuang, W.; Chaoyun, W. Molecular structures of nonvolatile components in the haihong fruit wine and their free radical scavenging effect. Food Chem. 2021, 353, 129298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gridnev, A.A.; Gudkov, M.V.; Bekhli, L.S.; Mel’nikov, V.P. Possible Mechanism of thermal reduction of graphite oxide. Russ. J. Phys. Chem. B 2019, 12, 1008–1016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- F Marcos, C.; Neo, A.G.; Díaz, J.; Martínez-Caballero, S. A safe and green benzylic radical bromination experiment. J. Chem. Educ. 2020, 97, 582–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.; Luo, Z.; Wang, W.; Cen, J. A study of the mechanisms of guaiacol pyrolysis based on free radicals detection technology. Catalysts 2020, 10, 295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haikal, R.R.; Soliman, A.B.; Pellechia, P.J.; Heißler, S.; Tsotsalas, M.; Ali, S.S.; Alkordi, M.H. Functional microporous polymers through Cu-mediated, free-radical polymerization of buckminster [60] fullerene. Carbon 2017, 118, 215–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, H.; Choi, W.; Zang, N.; Battistella, C.; Thompson, M.P.; Cao, W.; Zhou, X.; Forman, C.; Gianneschi, N.C. Bioactive peptide brush polymers via photoinduced reversible-deactivation radical polymerization. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2019, 58, 17359–17364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, Z.; Shi, S.; Wang, H. Radical chain polymerization catalyzed by graphene oxide and cooperative hydrogen bonding. Macromol. Rapid Comm. 2016, 37, 187–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Li, H.; Dong, J.; Hu, L.; Wei, D.; Bai, L.; Yang, H.; Chen, H. Recyclable bio-based photoredox catalyst in metal-free atom transfer radical polymerization. Macromol. Chem. Phys. 2021, 222, 2000406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamath, D.; Mezyk, S.P.; Minakata, D. Elucidating the elementary reaction pathways and kinetics of hydroxyl radical-induced acetone degradation in aqueous phase advanced oxidation processes. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2018, 52, 7763–7774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Q.; Ma, Y.; Chen, F.; Yao, F.; Sun, J.; Wang, S.; Yi, K.; Hou, L.; Li, X.; Wang, D. Recent advances in photo-activated sulfate radical-advanced oxidation process (SR-AOP) for refractory organic pollutants removal in water. Chem. Eng. J. 2019, 378, 122149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadley, J.H.; Gordy, W. Nuclear coupling of 33S and the nature of free radicals in irradiated crystals of N-acetyl-l-cysteine. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1977, 74, 216–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alagappan, A.; Costen, M.L.; McKendrick, K.G. Frequency modulated spectroscopy as a probe of molecular collision dynamics. Spectrochim. Acta Part A 2006, 63, 910–922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blumenschein, F.; Tamski, M.; Roussel, C.; Smolinsky, E.Z.B.; Tassinari, F.; Naaman, R.; Ansermet, J.P. Spin-dependent charge transfer at chiral electrodes probed by magnetic resonance. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2020, 22, 997–1002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varshney, D.; Kumar, A.; Prakash, J.; Meena, R.; Asokan, K. Gamma irradiation induced dielectric modulation and dynamic memory in nematic liquid crystal materials. J. Mol. Liq. 2020, 320, 114374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Z.; Qiao, C.; Yao, J.; Yan, Y.; Zhao, Y.S. Exciton funneling amplified photoluminescence anisotropy in organic radical-doped microcrystals. J. Mater. Chem. C 2022, 10, 2551–2555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iwasaki, A.; Hu, L.; Suizu, R.; Nomura, K.; Yoshikawa, H.; Awaga, K.; Noda, Y.; Kanai, K.; Ouchi, Y.; Seki, K.; et al. Interactive radical dimers in photoconductive organic thin films. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2009, 48, 4022–4024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, X.; Zhang, Y.; Bai, J.; Li, J.; Li, L.; Zhou, T.; Chen, S.; Wang, J.; Rahim, M.; Guan, X.; et al. Efficient degradation of N-containing organic wastewater via chlorine oxide radical generated by a photoelectrochemical system. Chem. Eng. J. 2020, 392, 123695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hudson, J.M.; Hele, T.J.H.; Evans, E.W. Efficient light-emitting diodes from organic radicals with doublet emission. J. Appl. Phys. 2021, 129, 180901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mu, Y.; Liu, Y.; Tian, H.; Ou, D.; Gong, L.; Zhao, J.; Zhang, Y.; Huo, Y.; Yang, Z.; Chi, Z. Sensitive and repeatable photoinduced luminescent radicals from a simple organic crystal. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2021, 60, 6367–6371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cho, J.M.; Song, C.E.; Moon, S.-J.; Shin, W.S.; Hong, S.; Kim, S.H.; Cho, S.; Lee, J.-K. Scavenging of galvinoxyl spin 1/2 radicals in the processing of organic spintronics. Org. Electron. 2018, 55, 21–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poggini, L.; Cucinotta, G.; Sorace, L.; Caneschi, A.; Gatteschi, D.; Sessoli, R.; Mannini, M. Nitronyl nitroxide radicals at the interface: A hybrid architecture for spintronics. Rend. Fisi. Acc. Lincei. 2018, 29, 623–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramos-Berdullas, N.; Gil-Guerrero, S.; Pena-Gallego, A.; Mandado, M. The effect of spin polarization on the electron transport of molecular wires with diradical character. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2021, 23, 4777–4783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rane, V. Achieving maximal enhancement of electron spin polarization in stable nitroxyl radicals at room temperature. J. Phys. Chem. B 2021, 125, 5620–5629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, X.J.; Zheng, C.; Lan, Y.H.; Chi, S.S.; Dong, Q.; Liu, H.L.; Peng, C.; Dong, L.Y.; Xu, L.; Wang, X.H. Synthesis of multirecognition magnetic molecularly imprinted polymer by atom transfer radical polymerization and its application in magnetic solid-phase extraction. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2018, 410, 247–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, Y.C.; Zhou, W.H.; Li, W.; Huang, H.M.; Laref, A.; Nan, N.; Zhang, J.; Yang, J.T. Emergent electronically-controllable local-field-inducer based on a molecular break-junction with magnetic radical. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2019, 21, 21693–21697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, H.; Vignesh, K.R.; Zhang, X.; Dunbar, K.R. From spin-crossover to single molecule magnetism: Tuning magnetic properties of Co(ii) bis-ferrocenylterpy cations via supramolecular interactions with organocyanide radical anions. J. Mater. Chem. C 2020, 8, 8135–8144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, H.; Wu, B.; Meng, Y.S.; Zhang, W.X.; Xi, Z. Synthesis, structure, and magnetic properties of rare-earth bis(diazabutadiene) diradical complexes. Inorg. Chem. 2021, 60, 1315–1319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gomberg, M. An instance of trivalent carbon: Triphenylmethyl. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1900, 22, 757–771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilhelm, S.; Tobias, W. III. ueber analoga des triphenylmethyls in der biphenylreihe. Justus Liebigs Ann. Chem. 1909, 368, 295–304. [Google Scholar]

- Metzmacher, K.D.; Brignell, J.E. Apparent charge mobility from breakdown times in a dielectric liquid. J. Phys. Appl. Phys. 1970, 3, 2215–2225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, B.; Liu, B.; Zeng, J.; Nie, H.; Xiong, Y.; Zou, J.; Ning, H.; Wang, Z.; Zhao, Z.; Tang, B.Z. Efficient bipolar blue AIEgens for high-performance nondoped blue OLEDs and hybrid white OLEDs. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2018, 28, 1803369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salehi, A.; Fu, X.; Shin, D.H.; So, F. Recent advances in OLED optical design. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2019, 29, 1808803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, D.; Li, W.; Gan, L.; Wang, Z.; Li, M.; Su, S.-J. Non-noble-metal-based organic emitters for OLED applications. Mater. Sci. Eng. R 2020, 142, 100581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helfrich, W.; Schneider, W.G. Recombination radiation in anthracene crystals. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1965, 14, 229–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, C.W.; VanSlyke, S.A. Organic electroluminescent diodes. Appl. Phys. Lett. 1987, 51, 913–915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiu, T.-L.; Xianyu, H.; Ge, Z.; Lee, J.-H.; Liu, K.-C.; Wu, S.-T. Transflective device with a transparent organic light-emitting diode and a reflective liquid-crystal device. J. Soc. Inf. Disp. 2009, 17, 1009–1013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, B.-F.; Alameh, K. High-contrast tandem organic light-emitting devices employing semitransparent intermediate layers of LiF/Al/C60. J. Phys. Chem. C 2012, 116, 24690–24694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Sim, B.; Moon, C.K.; Kim, K.H.; Kim, J.J. Quantitative analysis of the efficiency of OLEDs. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2016, 8, 33010–33018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeng, L.; Chime, A.C.; Chakaroun, M.; Bensmida, S.; Nkwawo, H.; Boudrioua, A.; Fischer, A.P.A. Electrical and optical impulse response of high-speed micro-OLEDs under ultrashort pulse excitation. IEEE Trans. Electron. Devices 2017, 64, 2942–2948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elsamnah, F.; Bilgaiyan, A.; Affiq, M.; Shim, C.H.; Ishidai, H.; Hattori, R. Reflectance-based organic pulse meter sensor for wireless monitoring of photoplethysmogram signal. Biosensors 2019, 9, 87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, Q.; Obolda, A.; Zhang, M.; Li, F. Organic light-emitting diodes using a neutral pi radical as emitter: The emission from a doublet. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2015, 54, 7091–7195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Feng, Y.; Yong, G.; Shen, C.; Zhao, Y. Proton-shared hydrogen bond: Promoting generation of novel triradicals, and serving as phosphorescent and magnetic switch. Synth. Met. 2016, 220, 477–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Lv, X.; Wang, J.; Sun, L.; Yan, Y. Surface molecular imprinted polymers based on Mn-doped ZnS quantum dots by atom transfer radical polymerization for a room-temperature phosphorescence probe of bifenthrin. Anal. Methods 2017, 9, 4609–4615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ni, L.; Yong, G. Crystal structures, phosphorescent and magnetic properties of novel 1,2-dihydroisoquinoline radicals. J. Mol. Struct. 2018, 1171, 614–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kosai, J.; Masuda, Y.; Chikayasu, Y.; Takahashi, Y.; Sasabe, H.; Chiba, T.; Kido, J.; Mori, H. S-vinyl sulfide-derived pendant-type sulfone/phenoxazine-based polymers exhibiting thermally activated delayed fluorescence: Synthesis and photophysical property characterization. ACS Appl. Polym. Mater. 2020, 2, 3310–3318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poisson, J.; Tonge, C.M.; Paisley, N.R.; Sauvé, E.R.; McMillan, H.; Halldorson, S.V.; Hudson, Z.M. Exploring the scope of through-space charge-transfer thermally activated delayed fluorescence in acrylic donor–acceptor copolymers. Macromolecules 2021, 54, 2466–2476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Chen, W.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Tian, Y.; Fang, L.; Ba, X. Photoredox organocatalysts with thermally activated delayed fluorescence for visible-light-driven atom transfer radical polymerization. Macromolecules 2021, 54, 4633–4640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Gao, Y.; Hussain, M.; Kundu, S.; Rane, V.; Hayvali, M.; Yildiz, E.A.; Zhao, J.; Yaglioglu, H.G.; Das, R.; et al. Efficient radical-enhanced intersystem crossing in an NDI-TEMPO dyad: Photophysics, electron spin polarization, and application in photodynamic therapy. Chem. Eur. J. 2018, 24, 18663–18675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awwad, N.; Bui, A.T.; Danilov, E.O.; Castellano, F.N. Visible-light-initiated free-radical polymerization by homomolecular triplet-triplet annihilation. Chem 2020, 6, 3071–3085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dartar, S.; Ucuncu, M.; Karakus, E.; Hou, Y.; Zhao, J.; Emrullahoglu, M. BODIPY-vinyl dibromides as triplet sensitisers for photodynamic therapy and triplet-triplet annihilation upconversion. Chem. Commun. 2021, 57, 6039–6042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tan, G.; Li, J.; Zhang, L.; Chen, C.; Zhao, Y.; Wang, X.; Song, Y.; Zhang, Y.Q.; Driess, M. The charge transfer approach to heavier main-group element radicals in transition-metal complexes. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2017, 56, 12741–12745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawanishi, Y.; Mutoh, K.; Abe, J.; Kobayashi, Y. Extending the lifetimes of charge transfer states generated by photoinduced heterolysis of photochromic radical complexes. Asian J. Org. Chem. 2021, 10, 891–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, S.; Zhang, S.-T.; Gao, Y.; Yang, X.; Liu, H.; Li, W.; Yang, B. Efficient and stable deep-blue narrow-spectrum electroluminescence based on hybridized local and charge-transfer (HLCT) state. Dye. Pigm. 2021, 193, 109482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brandt, J.R.; Wang, X.; Yang, Y.; Campbell, A.J.; Fuchter, M.J. Circularly polarized phosphorescent electroluminescence with a high dissymmetry factor from PHOLEDs based on a platinahelicene. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2016, 138, 9743–9746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhbaibi, K.; Abella, L.; Meunier-Della-Gatta, S.; Roisnel, T.; Vanthuyne, N.; Jamoussi, B.; Pieters, G.; Racine, B.; Quesnel, E.; Autschbach, J.; et al. Achieving high circularly polarized luminescence with push-pull helicenic systems: From rationalized design to top-emission CP-OLED applications. Chem. Sci. 2021, 12, 5522–5533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, Q.; Chen, S.; Sang, Y.; Guo, H.; Dong, S.; Han, J.; Chen, W.; Yang, X.; Li, F.; Duan, P. Circularly polarized luminescence of achiral open-shell pi-radicals. Chem. Commun. 2019, 55, 6583–6586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wei, Q.; Fei, N.; Islam, A.; Lei, T.; Hong, L.; Peng, R.; Fan, X.; Chen, L.; Gao, P.; Ge, Z. Small-molecule emitters with high quantum efficiency: Mechanisms, structures, and applications in OLED devices. Adv. Opt. Mater. 2018, 6, 1800512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Xu, P.; Hu, D.; Ma, Y. Recent progress in hot exciton materials for organic light-emitting diodes. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2021, 50, 1030–1069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kimura, K.; Miwa, K.; Imada, H.; Imai-Imada, M.; Kawahara, S.; Takeya, J.; Kawai, M.; Galperin, M.; Kim, Y. Selective triplet exciton formation in a single molecule. Nature 2019, 570, 210–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kafle, T.R.; Kattel, B.; Wanigasekara, S.; Wang, T.; Chan, W.L. Spontaneous exciton dissociation at organic semiconductor interfaces facilitated by the orientation of the delocalized electron–hole wavefunction. Adv. Energy Mater. 2020, 10, 1904013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, T.; Xia, L.; Liu, W.; Xie, J.; Jiang, Z.; Xiong, F.; Hu, W. Dy3+-doped LaInO3: A host-sensitized white luminescence phosphor with exciton-mediated energy transfer. J. Mater. Chem. C 2021, 9, 13410–13419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burdov, V.A.; Vasilevskiy, M.I. Exciton-photon interactions in semiconductor nanocrystals: Radiative transitions, non-radiative processes and environment effects. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Hu, Y.; Zhang, N.; Lv, Y.; Lin, J.; Guo, X.; Fan, Y.; Luo, J.; Liu, X. Near-infrared to visible organic upconversion devices based on organic light-emitting field effect transistors. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2017, 9, 36103–36110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, D.; Zhou, X.; Ma, D.; Vadim, A.; Ahamad, T.; Alshehri, S.M. Near infrared to visible light organic up-conversion devices with photon-to-photon conversion efficiency approaching 30%. Mater. Horiz. 2018, 5, 874–882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, B.H.; Cheng, Y.; Li, M.; Tsang, S.W.; So, F. Sub-band gap turn-on near-infrared-to-visible up-conversion device enabled by an organic-inorganic hybrid perovskite photovoltaic absorber. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2018, 10, 15920–15925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsushima, T.; Qin, C.; Goushi, K.; Bencheikh, F.; Komino, T.; Leyden, M.; Sandanayaka, A.S.D.; Adachi, C. Enhanced electroluminescence from organic light-emitting diodes with an organic-inorganic perovskite host layer. Adv. Mater. 2018, 30, 1802662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fadavieslam, M.R. The effect of thickness of light emitting layer on physical properties of OLED devices. Optik 2019, 182, 452–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Segal, M.; Baldo, M.A.; Holmes, R.J.; Forrest, S.R.; Soos, Z.G. Excitonic singlet-triplet ratios in molecular and polymeric organic materials. Phys. Rev. B 2003, 68, 075211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Yan, X.; Cheng, Z.; Zhang, H.; Liu, Y.; Wang, Y. Highly efficient near-infrared delayed fluorescence organic light emitting diodes using a phenanthrene-based charge-transfer compound. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2015, 54, 13068–13072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uoyama, H.; Goushi, K.; Shizu, K.; Nomura, H.; Adachi, C. Highly efficient organic light-emitting diodes from delayed fluorescence. Nature 2012, 492, 234–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thilagam, A. Effect of the Pauli exclusion principle on the singlet exciton yield in conjugated polymers. Appl. Phys. A 2016, 122, 254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Law, C.K. Quantum entanglement as an interpretation of bosonic character in composite two-particle systems. Phys. Rev. A 2005, 71, 034306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.W.; Yoo, S.I.; Kang, J.S.; Yoon, G.J.; Lee, S.E.; Kim, Y.K.; Kim, W.Y. Quenching in single emissive white phosphorescent organic light-emitting devices. Org. Electron. 2016, 38, 230–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strassner, T. Phosphorescent platinum(II) complexes with C(wedge)C* cyclometalated NHC ligands. Acc. Chem. Res. 2016, 49, 2680–2689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Aizawa, N.; Numata, M.; Adachi, C.; Yasuda, T. Versatile molecular functionalization for inhibiting concentration quenching of thermally activated delayed fluorescence. Adv. Mater. 2017, 29, 1604856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Chen, P.; Wang, X.; Wang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Li, F.; Yang, M.; Huang, Y.; Yu, J.; Lu, Z. Charge-transfer-featured materials-promising hosts for fabrication of efficient OLEDs through triplet harvesting via triplet fusion. Chem. Commun. 2014, 50, 7586–7589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, W.; Pan, Y.; Xiao, R.; Peng, Q.; Zhang, S.; Ma, D.; Li, F.; Shen, F.; Wang, Y.; Yang, B.; et al. Employing ∼100% excitons in OLEDs by utilizing a fluorescent molecule with hybridized local and charge-transfer excited state. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2014, 24, 1609–1614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Constantinides, C.P.; Koutentis, P.A. Stable N- and N/S-rich heterocyclic radicals. Adv. Heterocycl. Chem. 2016, 119, 173–207. [Google Scholar]

- Ji, L.; Shi, J.; Wei, J.; Yu, T.; Huang, W. Air-stable organic radicals: New-generation materials for flexible electronics? Adv. Mater. 2020, 32, 1908015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; Lin, S.; Lin, Z.; Peeks, M.D.; Van Voorhis, T.; Swager, T.M. A semiconducting conjugated radical polymer: Ambipolar redox activity and faraday effect. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2018, 140, 10881–10889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ota, K.; Nagao, K.; Ohmiya, H. Synthesis of sterically hindered alpha-hydroxycarbonyls through radical-radical coupling. Org. Lett. 2021, 23, 4420–4425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frisenda, R.; Gaudenzi, R.; Franco, C.; Mas-Torrent, M.; Rovira, C.; Veciana, J.; Alcon, I.; Bromley, S.T.; Burzuri, E.; van der Zant, H.S. Kondo effect in a neutral and stable all organic radical single molecule break junction. Nano. Lett. 2015, 15, 3109–3114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, S.; Xu, W.; Guo, H.; Yan, W.; Zhang, M.; Li, F. Effects of substituents on luminescent efficiency of stable triaryl methyl radicals. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2018, 20, 18657–18662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, H.; Peng, Q.; Chen, X.K.; Gu, Q.; Dong, S.; Evans, E.W.; Gillett, A.J.; Ai, X.; Zhang, M.; Credgington, D.; et al. High stability and luminescence efficiency in donor-acceptor neutral radicals not following the Aufbau principle. Nat. Mater. 2019, 18, 977–984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.H.; Hamzehpoor, E.; Sakai-Otsuka, Y.; Jadhav, T.; Perepichka, D.F. A pure-red doublet emission with 90% quantum yield: Stable, colorless, iodinated triphenylmethane solid. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2020, 59, 23030–23034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fajari, L.; Papoular, R.; Reig, M.; Brillas, E.; Jorda, J.L.; Vallcorba, O.; Rius, J.; Velasco, D.; Julia, L. Charge transfer states in stable neutral and oxidized radical adducts from carbazole derivatives. J. Org. Chem. 2014, 79, 1771–1777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Obolda, A.; Ai, X.; Zhang, M.; Li, F. Up to 100% formation ratio of doublet exciton in deep-red organic light-emitting diodes based on neutral pi-radical. ACS Appl. Mater. Inter. 2016, 8, 35472–35478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, Y.; Xu, W.; Ma, H.; Obolda, A.; Yan, W.; Dong, S.; Zhang, M.; Li, F. Novel luminescent benzimidazole-substituent tris(2,4,6-trichlorophenyl)methyl radicals: Photophysics, stability, and highly efficient red-orange electroluminescence. Chem. Mater. 2017, 29, 6733–6739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdurahman, A.; Hele, T.J.H.; Gu, Q.; Zhang, J.; Peng, Q.; Zhang, M.; Friend, R.H.; Li, F.; Evans, E.W. Understanding the luminescent nature of organic radicals for efficient doublet emitters and pure-red light-emitting diodes. Nat. Mater. 2020, 19, 1224–1229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Abdurahman, A.; Zhang, Y.; Zheng, P.; Zhang, M.; Li, F. Highly efficient multifunctional luminescent radicals. CCS Chem. 2021, 938–947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Arnold, M.; Blinder, R.; Jelezko, F.; Kuehne, A.J.C. Mixed-halide triphenyl methyl radicals for site-selective functionalization and polymerization. RSC Adv. 2021, 11, 27653–27658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, C.; An, D.; Chen, W.; Zhang, N.; Qiao, Y.; Fang, J.; Lu, X.; Zhou, G.; Liu, Y. Stable diarylamine-substituted tris (2,4,6-trichlorophenyl) methyl radicals: One-step synthesis, near-infrared emission, and redox chemistry. CCS Chem. 2021, 3405–3418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hattori, Y.; Kusamoto, T.; Nishihara, H. Luminescence, stability, and proton response of an open-shell (3,5-dichloro-4-pyridyl) bis (2,4,6-trichlorophenyl) methyl radical. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2014, 53, 11845–11848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hattori, Y.; Kusamoto, T.; Nishihara, H. Highly photostable luminescent open-shell (3,5-dihalo-4-pyridyl) bis (2,4,6-trichlorophenyl) methyl radicals: Significant effects of halogen atoms on their photophysical and photochemical properties. RSC Adv. 2015, 5, 64802–64805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kimura, S.; Kusamoto, T.; Kimura, S.; Kato, K.; Teki, Y.; Nishihara, H. Magnetoluminescence in a photostable, brightly luminescent organic radical in a rigid environment. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2018, 57, 12711–12715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kimura, S.; Tanushi, A.; Kusamoto, T.; Kochi, S.; Sato, T.; Nishihara, H. A luminescent organic radical with two pyridyl groups: High photostability and dual stimuli-responsive properties, with theoretical analyses of photophysical processes. Chem. Sci. 2018, 9, 1996–2007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hattori, Y.; Tsubaki, S.; Matsuoka, R.; Kusamoto, T.; Nishihara, H.; Uchida, K. Expansion of photostable luminescent radicals by meta-substitution. Chem. Asian. J. 2021, 16, 2538–2544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kimura, S.; Uejima, M.; Ota, W.; Sato, T.; Kusaka, S.; Matsuda, R.; Nishihara, H.; Kusamoto, T. An open-shell, luminescent, two-dimensional coordination polymer with a honeycomb lattice and triangular organic radical. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2021, 143, 4329–4338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsuoka, R.; Kimura, S.; Kusamoto, T. Solid-state room-temperature near-infrared photoluminescence of a stable organic radical. ChemPhotoChem 2021, 5, 669–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ai, X.; Chen, Y.; Feng, Y.; Li, F. A stable room-temperature luminescent biphenylmethyl radical. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2018, 57, 2869–2873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdurahman, A.; Chen, Y.; Ai, X.; Ablikim, O.; Gao, Y.; Dong, S.; Li, B.; Yang, B.; Zhang, M.; Li, F. A pure red luminescent β-carboline-substituted biphenylmethyl radical: Photophysics, stability and OLEDs. J. Mater. Chem. C 2018, 6, 11248–11254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ballester, M.; Riera-Figueras, J.; Rodríguez-Siurana, A. Synthesis and isolation of a perchlorotriphenylcarbonium salt. Tetrahedron Lett. 1970, 11, 3615–3618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sholle, V.D.; Rozantsev, E.G. Advances in the chemistry of stable hydrocarbon radicals. Russ. Chem. Rev. 1973, 42, 1011–1019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fox, M.A.; Gaillard, E.; Chen, C.C. Photochemistry of stable free radicals: The photolysis of perchlorotriphenylmethyl radicals. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1987, 109, 7088–7094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heckmann, A.; Lambert, C. Neutral organic mixed-valence compounds: synthesis and all-optical evaluation of electron-transfer parameters. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007, 129, 5515–5527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heckmann, A.; Dümmler, S.; Pauli, J.; Margraf, M.; Köhler, J.; Stich, D.; Lambert, C.; Fischer, I.; Resch-Genger, U. Highly fluorescent open-shell NIR dyes: The time-dependence of back electron transfer in triarylamine-perchlorotriphenylmethyl radicals. J. Phys. Chem. C 2009, 113, 20958–20966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heckmann, A.; Lambert, C.; Goebel, M.; Wortmann, R. Synthesis and photophysics of a neutral organic mixed-valence compound. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2004, 43, 5851–5856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cho, E.; Coropceanu, V.; Bredas, J.L. Organic neutral radical emitters: Impact of chemical substitution and electronic-state hybridization on the luminescence properties. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2020, 142, 17782–17786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guasch, J.; Grisanti, L.; Souto, M.; Lloveras, V.; Vidal-Gancedo, J.; Ratera, I.; Painelli, A.; Rovira, C.; Veciana, J. Intra- and intermolecular charge transfer in aggregates of tetrathiafulvalene-triphenylmethyl radical derivatives in solution. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013, 135, 6958–6967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armet, O.; Veciana, J.; Rovira, C.; Riera, J.; Castaner, J.; Molins, E.; Rius, J.; Miravitlles, C.; Olivella, S.; Brichfeus, J. Inert carbon free radicals. 8. Polychlorotriphenylmethyl radicals: Synthesis, structure, and spin-density distribution. J. Phys. Chem. 1987, 91, 5608–5616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carriedo, G.A.; Alonso, F.J.G.; Elipe, P.G.; Brillas, E.; Julia, L. Incorporation of stable organic radicals into cyclotriphosphazene: Preparation and characterization of mono- and diradical adducts. Org. Lett. 2001, 3, 1625–1628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres, J.L.; Varela, B.; Brillas, E.; Julia, L. Tris(2,4,6-trichloro-3,5-dinitrophenyl)methyl radical: A new stable coloured magnetic species as a chemosensor for natural polyphenols. Chem. Commun. 2003, 1, 74–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Viadel, L.; Carilla, J.; Brillas, E.; Labarta, A.; Julia’, L. Two spin-containing fragments connected by a two-electron one-center heteroatom p spacer. A new open-shell organic molecule with a singlet ground state. J. Mater. Chem. A 1998, 8, 1165–1172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gamero, V.; Velasco, D.; Latorre, S.; López-Calahorra, F.; Brillas, E.; Juliá, L. [4-(N-Carbazolyl)-2,6-dichlorophenyl] bis(2,4,6-trichlorophenyl)methyl radical an efficient red light-emitting paramagnetic molecule. Tetrahedron Lett. 2006, 47, 2305–2309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, E.; Coropceanu, V.; Brédas, J.-L. Impact of chemical modifications on the luminescence properties of organic neutral radical emitters. J. Mater. Chem. C 2021, 9, 10794–10801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, Z.; Ye, S.; Wang, L.; Guo, H.; Obolda, A.; Dong, S.; Chen, Y.; Ai, X.; Abdurahman, A.; Zhang, M.; et al. Radical-based organic light-emitting diodes with maximum external quantum efficiency of 10.6. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2018, 9, 6644–6648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bin, Z.; Guo, H.; Liu, Z.; Li, F.; Duan, L. Stable organic radicals as hole injection dopants for efficient optoelectronics. ACS Appl. Mater. Inter. 2018, 10, 4882–4886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdurahman, A.; Peng, Q.; Ablikim, O.; Ai, X.; Li, F. A radical polymer with efficient deep-red luminescence in the condensed state. Mater. Horiz. 2019, 6, 1265–1270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hattori, Y.; Kusamoto, T.; Nishihara, H. Enhanced luminescent properties of an open-shell (3,5-dichloro-4-pyridyl) bis (2,4,6-trichlorophenyl) methyl radical by coordination to gold. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2015, 54, 3731–3734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Molecule | Solvent | Λf a (nm) | Φf | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PTM-PCz | cyclohexane | 673 | 0.44 | [88] |

| PTM-3PCz | cyclohexane | 679 | 0.57 | [88] |

| PTM-TPA | cyclohexane | 767 | 0.26 | [88] |

| PTM-3PCz | cyclohexane | 663 | 0.043 | [88] |

| PTM-TPA | cyclohexane | 664 | 0.29 | [88] |

| 3I-PTMR b | cyclohexane | 605 | 0.016 | [89] |

| TTM | cyclohexane | 680 | 0.54 | [89] |

| TTM-1Cz | / | 611 | 0.91 | [90] |

| TTM-2Bi | cyclohexane | 562 | 0.008 | [91] |

| TTM-3Bi | cyclohexane | 692 | 0.58 | [92] |

| TTM-αPyID | chloroform | 588 | 0.16 | [93] |

| TTM-βPyID | chloroform | 593 | 0.30 | [93] |

| TTM-γPyID | cyclohexane | 599 | 0.63 | [94] |

| TTM-δPyID | cyclohexane | 610 | 0.98 | [94] |

| 2αPyID-TTM | cyclohexane | 598 | 0.37 | [94] |

| 2δPyID-TTM | cyclohexane | 614 | 0.89 | [94] |

| TTM-PCz | cyclohexane | 608 | 0.65 | [95] |

| TTM-3PCz | cyclohexane | 627 | 0.92 | [95] |

| TBr3Cl6M | DCM | / | 0.018 | [96] |

| TBr6Cl3M | DCM | / | 0.012 | [96] |

| TTBrM | DCM | / | 0.008 | [96] |

| TTM-DPA | cyclohexane | 705 | 0.65 | [97] |

| TTM-DBPA | cyclohexane | 748 | 0.28 | [97] |

| TTM-DFA | cyclohexane | 809 | 0.05 | [97] |

| PyBTM | EPA c (77 K) | / | 0.81 | [98] |

| Br2PyBTM | chloroform | 593 | 0.02 | [99] |

| F2PyBTM | chloroform | 566 | 0.06 | [99] |

| PyBTM d | / | 680 | 0.89 | [100] |

| bisPyTM | dichloromethane | 650 | 0.009 | [101] |

| mBr2-F2PyBTM | EPA c (77 K) | / | 0.11 | [102] |

| mPh2-F2PyBTM | EPA c (77 K) | / | 0.12 | [102] |

| mClPh2-F2PyBTM | EPA c (77 K) | / | 0.11 | [102] |

| mPy2-F2PyBTM | EPA c (77 K) | / | 0.07 | [102] |

| trisPyM | CH2Cl2 | 700 | 0.0085 | [103] |

| metaPyBTM | dichloromethane | 571 | 0.017 | [104] |

| CzBTM | cyclohexane | 697 | 0.020 | [105] |

| PyID-BTM | cyclohexane | 664 | 0.195 | [106] |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Luo, J.; Rong, X.-F.; Ye, Y.-Y.; Li, W.-Z.; Wang, X.-Q.; Wang, W. Research Progress on Triarylmethyl Radical-Based High-Efficiency OLED. Molecules 2022, 27, 1632. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules27051632

Luo J, Rong X-F, Ye Y-Y, Li W-Z, Wang X-Q, Wang W. Research Progress on Triarylmethyl Radical-Based High-Efficiency OLED. Molecules. 2022; 27(5):1632. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules27051632

Chicago/Turabian StyleLuo, Jie, Xiao-Fan Rong, Yu-Yuan Ye, Wen-Zhen Li, Xiao-Qiang Wang, and Wenjing Wang. 2022. "Research Progress on Triarylmethyl Radical-Based High-Efficiency OLED" Molecules 27, no. 5: 1632. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules27051632

APA StyleLuo, J., Rong, X.-F., Ye, Y.-Y., Li, W.-Z., Wang, X.-Q., & Wang, W. (2022). Research Progress on Triarylmethyl Radical-Based High-Efficiency OLED. Molecules, 27(5), 1632. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules27051632