X-ray Absorption Spectroscopy Study of Iron Site Manganese Substituted Yttrium Orthoferrite

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Crystal Structure and Rietveld Refinement

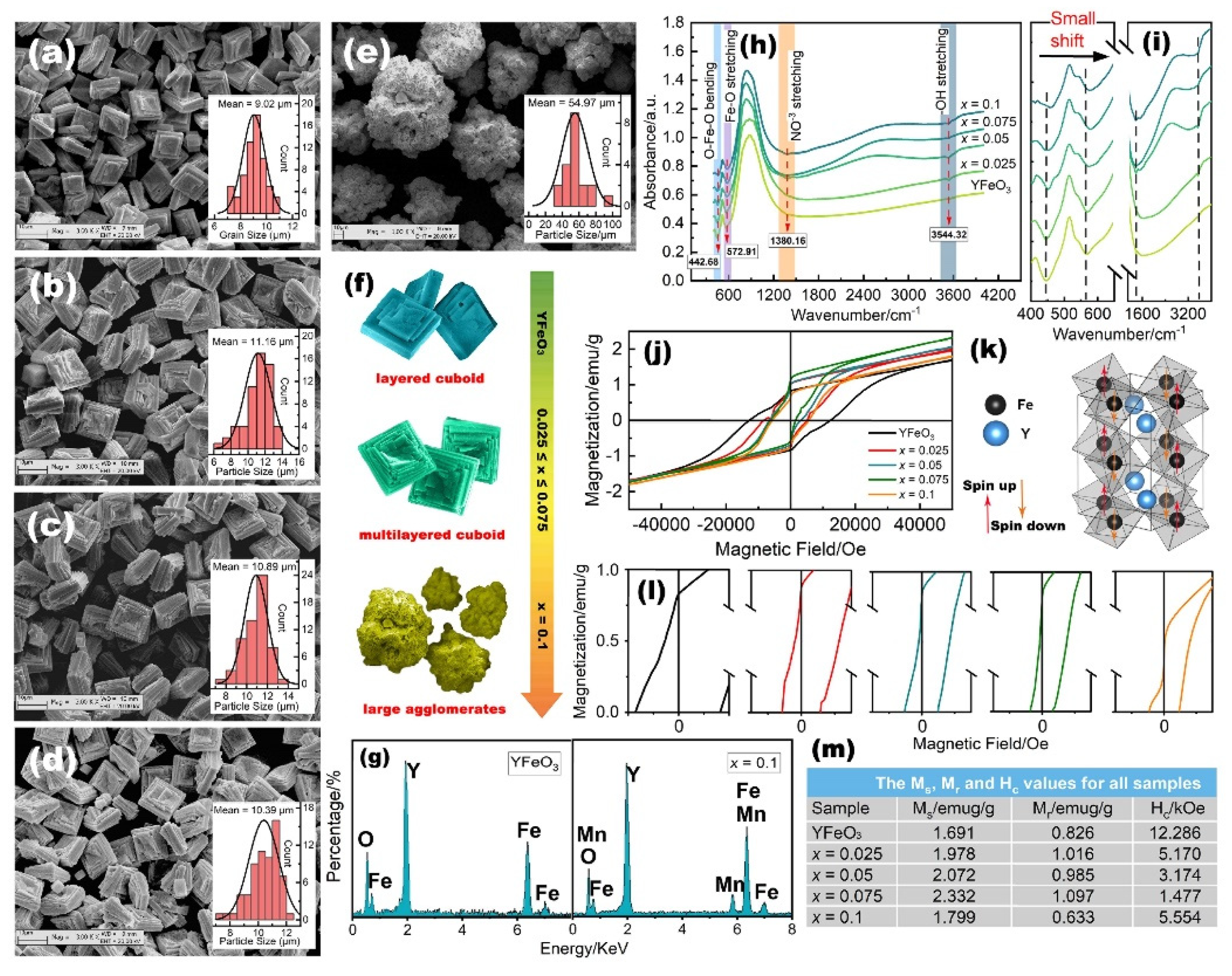

2.2. Morphological, Optical, and Magnetic Properties

2.3. Fe K-Edge Local Electronic Structure

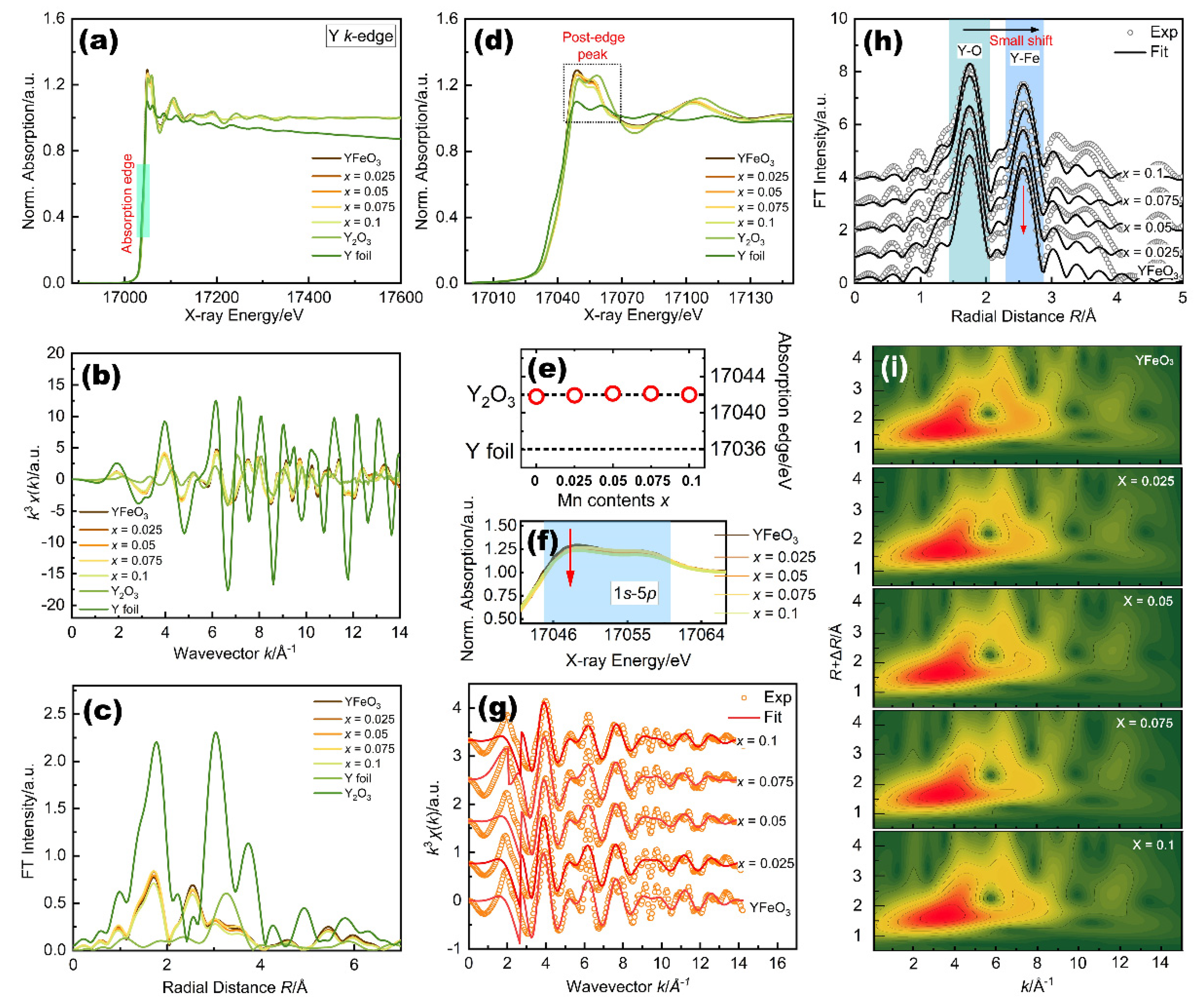

2.4. Y K-Edge Local Electronic Structure

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Sample Preparation

3.2. Characterization

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kimura, T.; Goto, T.; Shintani, H.; Ishizaka, K.; Arima, T.; Tokura, Y. Magnetic control of ferroelectric polarization. Nature 2003, 426, 55–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brown, C.S. Magnetic Oxides Parts 1 and 2. Phys. Bull. 1975, 26, 546–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, R. Review of Recent Work on the Magnetic and Spectroscopic Properties of the Rare-Earth Orthoferrites. J. Appl. Phys. 1969, 40, 1061–1069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Didosyan, Y.S.; Hauser, H. Observation of Bloch lines in yttrium orthoferrite. Phys. Lett. A 1998, 238, 395–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Didosyan, Y.S.; Hauser, H.; Reider, G.A.; Toriser, W. Fast latching type optical switch. J. Appl. Phys. 2004, 95, 7339–7341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.F.; Liu, J.M.; Ren, Z.F. Multiferroicity: The coupling between magnetic and polarization orders. Adv. Phys. 2009, 58, 321–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bamzai, K.K.; Bhat, M. Electrical and Magnetic Properties of Some Rare Earth Orthoferrites (RFeO3 where R = Y, Ho, Er) Systems. Integr. Ferroelectr. 2015, 158, 108–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bombik, A.; Leśniewska, B.; Mayer, J.; Pacyna, A.W. Crystal structure of solid solutions REFe1−x(Al or Ga)xO3 (RE = Tb, Er, Tm) and the correlation between superexchange interaction Fe+3-O−2-Fe+3 linkage angles and Néel temperature. J. Magn. Magn. M 2003, 257, 206–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Z.Q.; Guo, L.; Yang, H.X.; Qiang, L.; Feng, Y. Hydrothermal synthesis and magnetic properties of multiferroic rare-earth orthoferrites. J. Alloys Compd. 2014, 583, 21–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coutinho, P.V.; Cunha, F.; Barrozo, P. Structural, vibrational and magnetic properties of the orthoferrites LaFeO3 and YFeO3: A comparative study. Solid State Commun. 2017, 252, 59–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dho, J.; Blamire, M.G. Competing functionality in multiferroic YMnO3. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2005, 87, 252504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosales-González, O.; Sánchez-De Jesús, F.; Cortés-Escobedo, C.A.; Bolarín-Miró, A.M. Crystal structure and multiferroic behavior of perovskite YFeO3. Ceram. Int. 2018, 44, 15298–15303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geller, S. Crystal Structure of Gadolinium Orthoferrite, GdFeO3. J. Chem. Phys. 1956, 24, 1236–1239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, Z.M.; Mics, Z.; Ma, G.H.; Cheng, Z.X.; Bonn, M.; Turchinovich, D. Single-pulse terahertz coherent control of spin resonance in the canted antiferromagnet YFeO3, mediated by dielectric anisotropy. Phys. Rev. B 2013, 87, 094422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, T.H.; Hamh, S.Y.; Han, J.W.; Kang, C.; Kee, C.S.; Jung, S.; Park, J.; Tokunaga, Y.; Tokura, Y.; Lee, J.S. Coherently controlled spin precession in canted antiferromagnetic YFeO3 using terahertz magnetic field. Appl. Phys. Express 2014, 7, 093007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, R.; Wang, Y.; Cui, B.; Wang, Y.J.; Wang, Y.Y. Fabrication of submicron BaTiO3@YFeO3 particles and fine-grained composite magnetodielectric ceramics with a core-shell structure by means of a co-precipitation method. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Electron. 2017, 28, 10986–10991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, K.; Hur, S.; Park, S. The absence of ferroelectricity and the origin of depolarization currents in YFe0.8Mn0.2O3. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2017, 110, 162905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, T.; Shen, H.; Wu, A.H.; Man, P.W.; Su, L.B.; Shi, Z.; Xu, J.Y. Crystal growth, spin reorientation and magnetic anisotropy of YFe0.8Mn0.2O3 single crystal. Solid State Commun. 2016, 247, 64–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, T.; Shen, H.; Zhao, X.Y.; Man, P.W.; Wu, A.H.; Su, L.B.; Xu, J.Y. Single crystal growth, magnetic and thermal properties of perovskite YFe0.6Mn0.4O3 single crystal. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 2016, 417, 143–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Wang, X.F.; Wang, Z.W.; Yan, H.T.; Li, H.S.; Li, L.B. Dielectric relaxation, electric modulus and ac conductivity of Mn-doped YFeO3. Ceram. Int. 2016, 42, 19461–19465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Wang, Z.W.; Yan, H.T.; Wang, X.F.; Kang, D.W.; Li, L.B. Structural and magnetic properties in YFe0.8Mn0.2O3 ceramics. Mater. Lett. 2014, 136, 15–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deka, B.; Ravi, S.; Perumal, A.; Pamu, D. Effect of Mn doping on magnetic and dielectric properties of YFeO3. Ceram. Int. 2017, 43, 1323–1334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deka, B.; Ravi, S.; Perumal, A. Study of Exchange Bias in Mn-Doped YFeO3 Compound. J. Supercond. Nov. Magn. 2016, 29, 2165–2170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, X.Q.; Kim, C.S.; Yoo, H.I. Effect of Substitution of Manganese for Iron on the Structure and Electrical Properties of Yttrium Ferrite. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 2001, 84, 1265–1272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, H.; Xu, J.Y.; Jin, M.; Jiang, G.J. Influence of manganese on the structure and magnetic properties of YFeO3 nanocrystal. Ceram. Int. 2012, 38, 1473–1477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandal, P.; Bhadram, V.S.; Sundarayya, Y.; Narayana, C.; Sundaresan, A.; Rao, C.N.R. Spin-reorientation, ferroelectricity, and magnetodielectric effect in YFe1−xMnxO3 (0.1 ≤ x ≤ 0.40). Phys. Rev. Lett. 2011, 107, 137202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padmasree, G.; Reddy, S.S.K.; Ramesh, J.; Reddy, P.Y.; Reddy, C.G. 57Fe Mossbauer and electrical studies of Mn doped YFeO3 prepared via sol-gel technique. Mater. Res. Express 2020, 7, 116103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suthar, L.; Bhadala, F.; Kumari, P.; Mishra, S.K.; Roy, M. Effect of Mn substitution on crystal structure and electrical behaviour of YFeO3 ceramic. Ceram. Int. 2021, 47, 19007–19018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bharadwaj, P.S.J.; Kundu, S.; Kollipara, V.S.; Varma, K.B.R. Structural, optical and magnetic properties of Sm3+ doped yttrium orthoferrite (YFeO3) obtained by sol-gel synthesis route. J. Phys. Condens. Matter 2020, 32, 035810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Cheng, L.C.; Huang, L.; Ye, F.X.; Yao, Q.R.; Lu, Z.; Zhou, H.Y.; Qi, H.Y. Outstanding microwave absorption behavior and classical magnetism of Y1−xKxFeO3 honeycomb-like nano powders. J. Alloys Compd. 2022, 910, 164927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Aguilar, E.; Hmŏk, H.; Ribas-Ario, J.; Beltrones, J.M.S.; Lozada-Morales, R. Structural, ferroelectric, and optical properties of Bi3+ doped YFeO3: A first-principles study. Int. J. Quantum Chem. 2020, 121, 7. [Google Scholar]

- Pham, D.H.T.; Nguyen, L.T.T.; Mittova, V.O.; Chau, D.H.; Mittova, I.Y.; Nguyen, T.A.; Bui, V.X. Structural, optical and magnetic properties of Sr and Ni co-doped YFeO3 nanoparticles prepared by simple co-precipitation method. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Electron. 2022, 33, 14356–14367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, H.; Jiang, G.J. Effects of Nd, Er Doping on the Structure and Magnetic Properties of YFeO3. J. Supercond. Nov. Magn. 2018, 31, 2511–2517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kidkhunthod, P.; Phumying, S.; Maensiri, S. X-ray absorption spectroscopy study on yttrium iron garnet (Y3Fe5O12) nanocrystalline powders synthesized using egg white-based sol-gel route. Microelectron. Eng. 2014, 126, 148–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sayers, D.E.; Stern, E.A.; Lytle, F.W. New Method to Measure Structural Disorder: Application to GeO2 Glass. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1975, 35, 584–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subías, G.; García, J.; Proietti, M.G.; Blasco, J. X-ray-absorption near-edge spectroscopy and circular magnetic X-ray dichroism at the Mn K edge of magnetoresistive manganites. Phys. Rev. B 1997, 56, 8183–8191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lytle, F.W.; Sayers, D.E.; Stern, E.A. Extended X-ray-absorption fine-structure technique. II. Experimental practice and selected results. Phys. Rev. B 1975, 11, 4825–4835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vishnoi, A.N.; Agarwal, B.K. Theory of the extended X-ray-absorption fine structure. Proc. Phys. Soc. 1966, 89, 799–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, Z.M.; Zhang, H.; Shen, K.C.; Qu, Y.Q.; Jiang, Z. Wavelet analysis of extended X-ray absorption fine structure data: Theory, application. Phys. B 2018, 542, 12–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Funke, H.; Chukalina, M.; Rossberg, A. Wavelet analysis of extended X-ray absorption fine structure data. Phys. Scr. 2005, T115, 232–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Funke, H.; Chukalina, M.; Voegelin, A.; Scheinost, A.C. Improving Resolution in k and r Space: A FEFF-based Wavelet for EXAFS Data Analysis. AIP. Conf. Proc. 2007, 882, 72–74. [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen, T.A.; Pham, V.; Chau, D.H.; Mittova, V.O.; Mittavoa, I.Y.A.; Kopeychenko, E.I.; Nguyen, L.T.T.; Bui, V.X.; Nguyen, A.T.P. Effect of Ni substitution on phase transition, crystal structure and magnetic properties of nanostructured YFeO3 perovskite. J. Mol. Struct. 2020, 1215, 128293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Racu, A.V.; Ursu, D.H.; Kuliukova, O.V.; Logofatu, C.; Leca, A.; Miclau, M. Direct low temperature hydrothermal synthesis of YFeO3 microcrystals. Mater. Lett. 2015, 140, 107–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boulay, D.D.; Maslen, E.N.; Streltsov, V.A.; Ishizawa, N. A synchrotron X-ray study of the electron density in YFeO3. Acta Cryst. 1995, B51, 921–929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phokha, S.; Pinitsoontorn, S.; Maensiri, S. Room-temperature ferromagnetism in Co-doped CeO2 nanospheres prepared by the polyvinylpyrrolidone-assisted hydrothermal method. J. Appl. Phys. 2012, 112, 113904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geng, F.X.; Matsushita, Y.; Ma, R.Z.; Xin, H.; Tanaka, M.; Iyi, N.; Sasaki, T. Synthesis and properties of well-crystallized layered rare-earth hydroxide nitrates from homogeneous precipitation. Inorg. Chem. 2009, 48, 6724–6730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Yu, Z.L.; Liu, S.T. Preparation, crystal structure, and vibrational spectra of perovskite-type mixed oxides LaMyM′1−yO3 (M, M′ = Mn, Fe, Co). J. Solid State Chem. 1994, 112, 157–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farhadi, S.; Zaidi, M. Bismuth ferrite (BiFeO3) nanopowder prepared by sucrose-assisted combustion method: A novel and reusable heterogeneous catalyst for acetylation of amines, alcohols and phenols under solvent-free conditions. J. Mol. Catal. A-Chem. 2008, 299, 15–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raut, S.; Babu, P.D.; Sharma, R.K.; Pattanayak, R.; Panigrahi, S. Grain boundary-dominated electrical conduction and anomalous optical-phonon behaviour near the Neel temperature in YFeO3 ceramics. J. Appl. Phys. 2018, 123, 174101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hahn, S.E.; Podlesnyak, A.A.; Ehlers, G.; Granroth, G.E. Inelastic neutron scattering studies of YFeO3. Phys. Rev. B 2014, 89, 014420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lima Jr, E.; Martins, T.B.; Rechenberg, H.R.; Goya, G.F.; Cavelius, C.; Rapalaviciute, R.; Hao, S.; Mathur, S. Numerical simulation of magnetic interactions in polycrystalline YFeO3. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 2008, 320, 622–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Jaiswal, A.; Das, R.; Adyanthaya, S.; Poddar, P. Surface Effects on Morin Transition, Exchange Bias, and Enchanced Spin Reorientation in Chemically Synthesized DyFeO3 Nanoparticles. J. Phys. Chem. C 2011, 115, 2954–2960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blasco, J.; Aznar, B.; Garcia, J.; Subias, G.; Herrero-Martin, J.; Stankiewicz, J. Charge disproportionation in La1−xSrxFeO3 probed by diffraction and spectroscopic experiments. Phys. Rev. B 2008, 77, 054107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haas, O.; Vogt, U.F.; Soltmann, C.; Braun, A.; Yoon, W.S.; Yang, X.Q.; Graule, T. The Fe K-edge X-ray absorption characteristics of La1−xSrxFeO3−δ prepared by solid state reaction. Mater. Res. Bull. 2009, 44, 1397–1404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yotburut, B.; Yamwong, T.; Thongbai, P.; Maensiri, S. Synthesis and characterization of coprecipitation-prepared La-doped BiFeO3 nanopowders and their bulk dielectric properties. Jpn. J. Appl. Phys. 2014, 53, 06JG13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, E.W.; Mckinstry, H.A. Chemical effect on X-ray absorption-edge fine structure. In Advances in X-ray Analysis; Springer: Boston, MA, USA, 1966; pp. 376–392. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.T.; Zhang, H.G.; Liu, H.; Dong, X.D.; Li, Q.; Chen, W.; Mao, W.W.; Li, X.A.; Dong, C.L.; Ren, S.L. Magnetic properties and local structure of the binary elements codoped Bi1−xLaxFe0.95Mn0.05O3. J. Alloys Compd. 2014, 592, 19–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seremak-Peczkis, P.; Schneider, K.; Zajączkowski, W.; Kapusta, C.; Zając, D.A.; Pasierb, P.; Bućko, M.; Drożdż-Cieśla, E.; Rękas, M. XAFS study of BaCe1−xTixO3 and Ba1−yCe1−xYxO3 protonic solid electrolytes. Radiat. Phys. Chem. 2009, 78, S86–S88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bajpai, G.; Srivastava, T.; Patra, N.; Moirangthem, I.; Jha, S.N.; Bhattacharyya, D.; Riyajuddin, S.; Ghosh, K.; Basaula, D.R.; Khan, M.; et al. Effect of ionic size compensation by Ag+ incorporation in homogeneous Fe-substituted ZnO: Studies on structural, mechanical, optical, and magnetic properties. RSC. Adv. 2018, 8, 24355–24369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roe, A.L.; Schneider, D.J.; Mayer, R.J.; Pyrz, J.W.; Widom, J.; Que, L., Jr. X-ray Absorption Spectroscopy of Iron-Tyrosinate Proteins. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1984, 106, 1676–1681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, P.Q.; Wu, G.; Wang, X.Q.; Liu, S.J.; Zhou, F.Y.; Dai, L.; Wang, X.; Yang, B.; Yu, Z.Q. NiCo-LDH nanosheets strongly coupled with GO-CNTs as a hybrid electrocatalyst for oxygen evolution reaction. Nano Res. 2021, 14, 4783–4788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torkler, A.; Beuthirn, H.; Gunßer, W.; Niemann, W. X-ray Absorption Spectroscopy of Amorphous Rare-Earth Transition-Metal. Phys. Chem. 1987, 91, 1300–1304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayashi, F.; Tanaka, M.; Lin, D.M.; Iwamoto, M. Surface structure of yttrium-modified ceria catalysts and reaction pathways from ethanol to propene. J. Catal. 2014, 316, 112–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, P.; Chen, I.W.; Penner-Hahn, J.E. X-ray-absorption studies of zirconia polymorphs. II. Effect of Y2O3 dopant on ZrO2 structure. Phys. Rev. B 1993, 48, 10074–10081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Finck, N.; Bouby, M.; Dardenne, K.; Yokosawa, T. Yttrium co-precipitation with smectite: A polarized XAS and AsFlFFF study. Appl. Clay Sci. 2017, 137, 11–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravel, B.; Newville, M. ATHENA, ARTEMIS, HEPHAESTUS: Data analysis for X-ray absorption spectroscopy using IFEFFIT. J. Synchrotron Rad. 2005, 12, 537–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gholam, T.; Wang, H.-Q. X-ray Absorption Spectroscopy Study of Iron Site Manganese Substituted Yttrium Orthoferrite. Molecules 2022, 27, 7648. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules27217648

Gholam T, Wang H-Q. X-ray Absorption Spectroscopy Study of Iron Site Manganese Substituted Yttrium Orthoferrite. Molecules. 2022; 27(21):7648. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules27217648

Chicago/Turabian StyleGholam, Turghunjan, and Hui-Qiong Wang. 2022. "X-ray Absorption Spectroscopy Study of Iron Site Manganese Substituted Yttrium Orthoferrite" Molecules 27, no. 21: 7648. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules27217648

APA StyleGholam, T., & Wang, H.-Q. (2022). X-ray Absorption Spectroscopy Study of Iron Site Manganese Substituted Yttrium Orthoferrite. Molecules, 27(21), 7648. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules27217648