A Generalized Method for the Synthesis of Carbon-Encapsulated Fe3O4 Composites and Its Application in Water Treatment

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

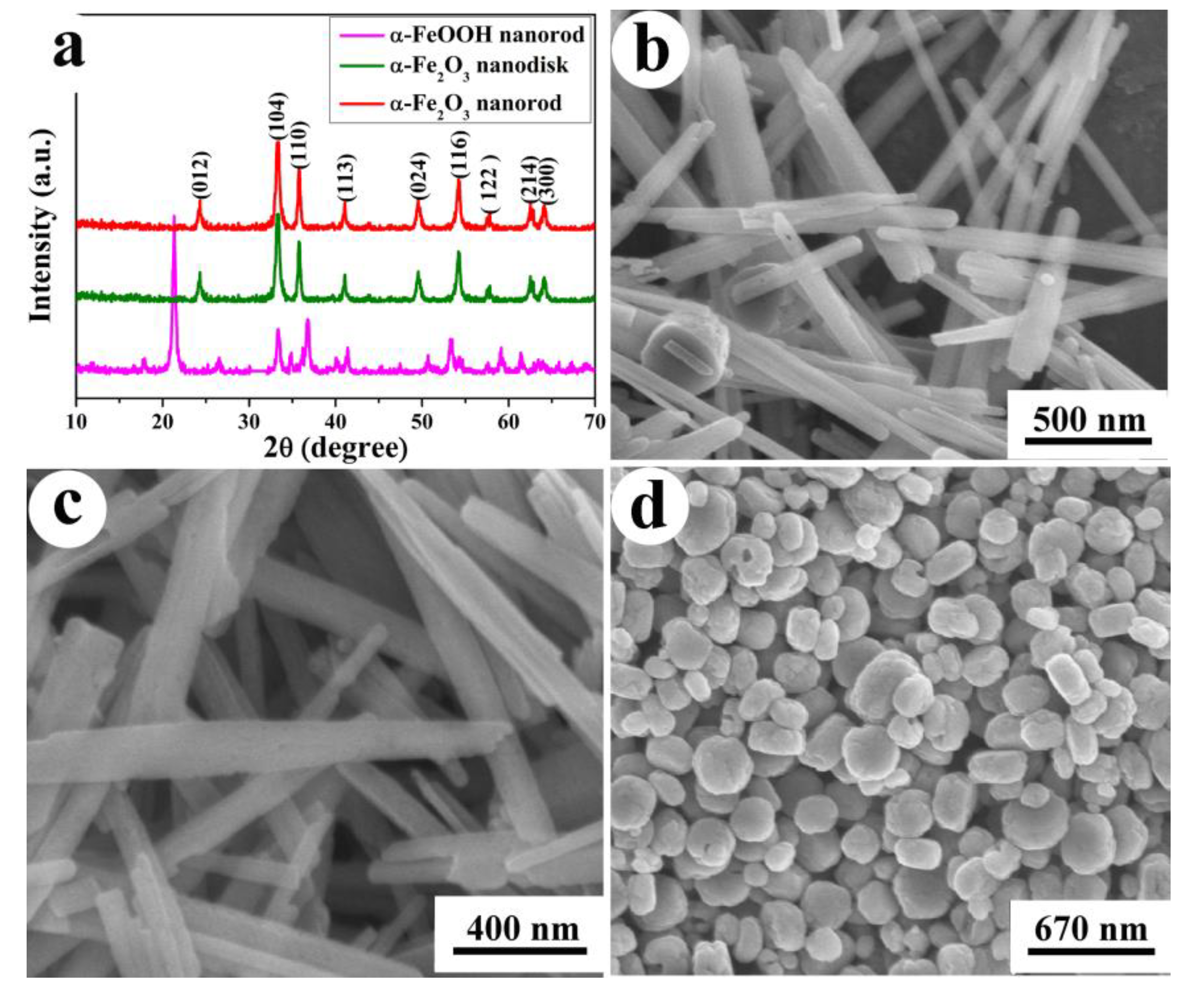

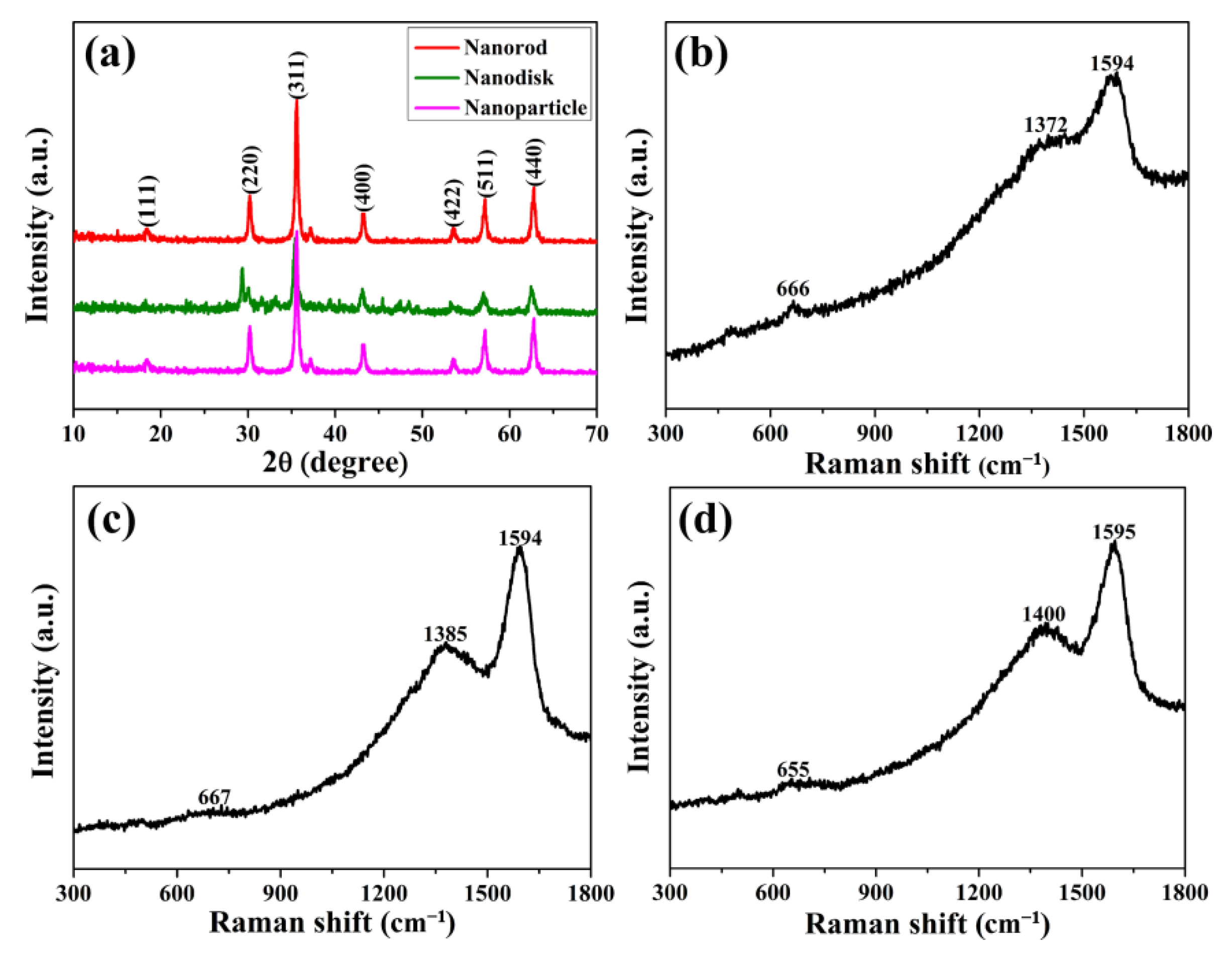

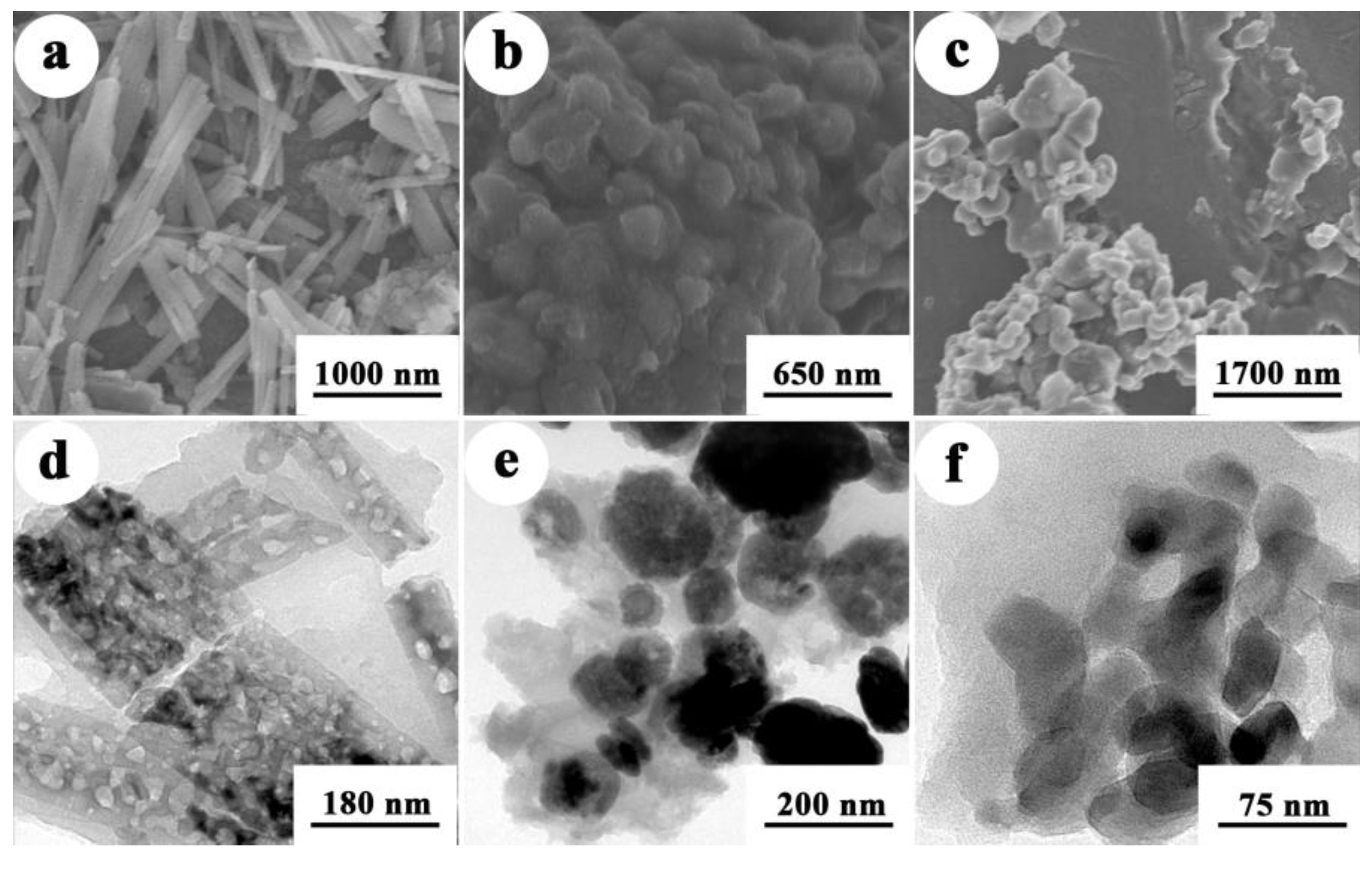

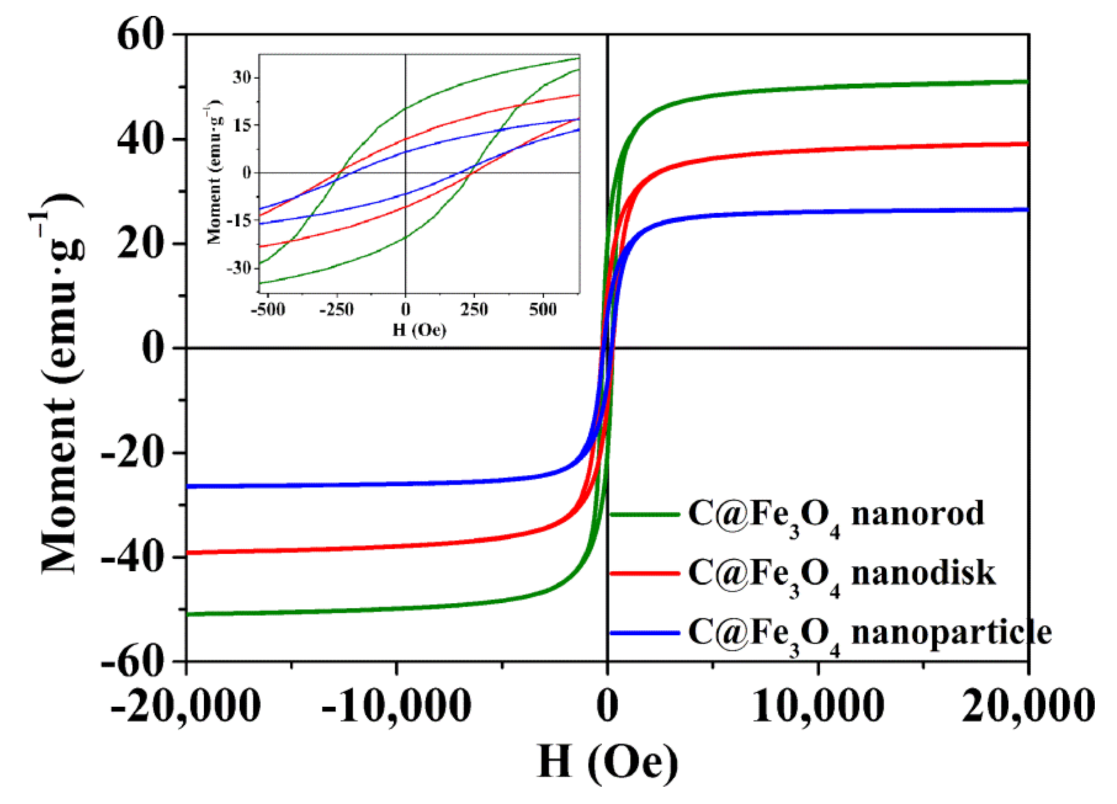

2.1. Properties of the Synthesized Samples

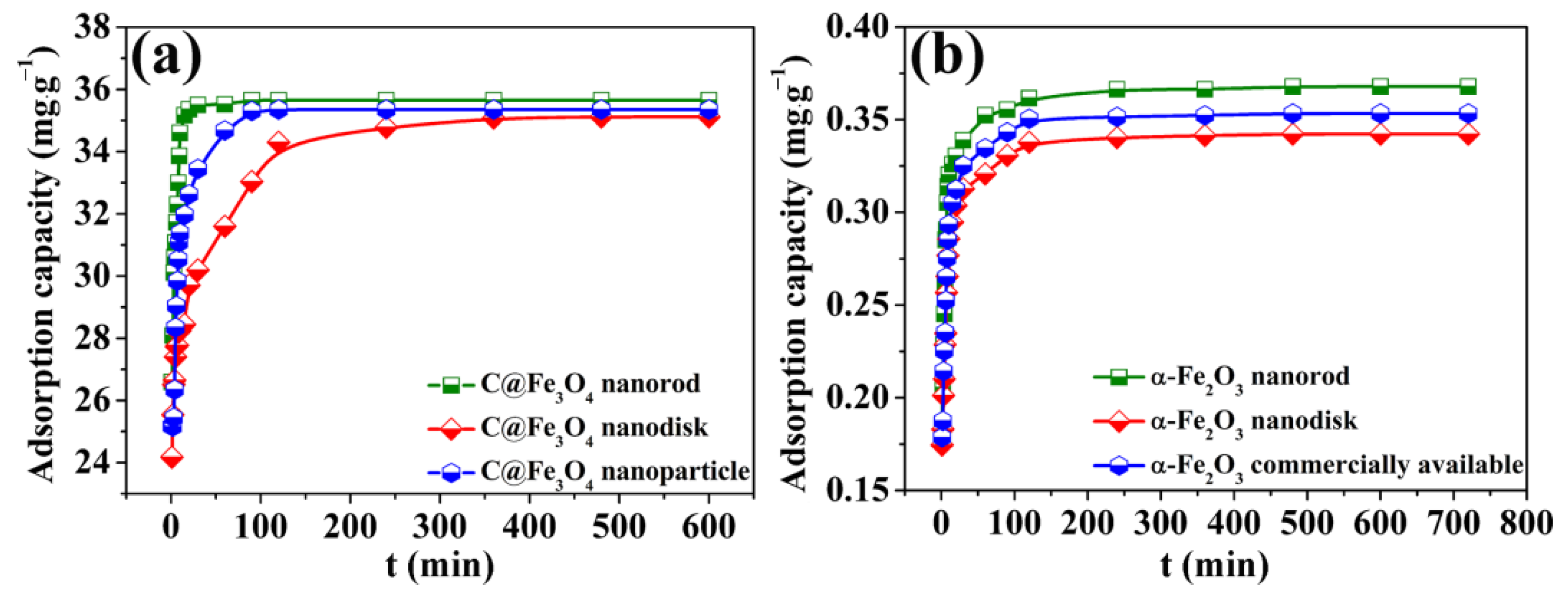

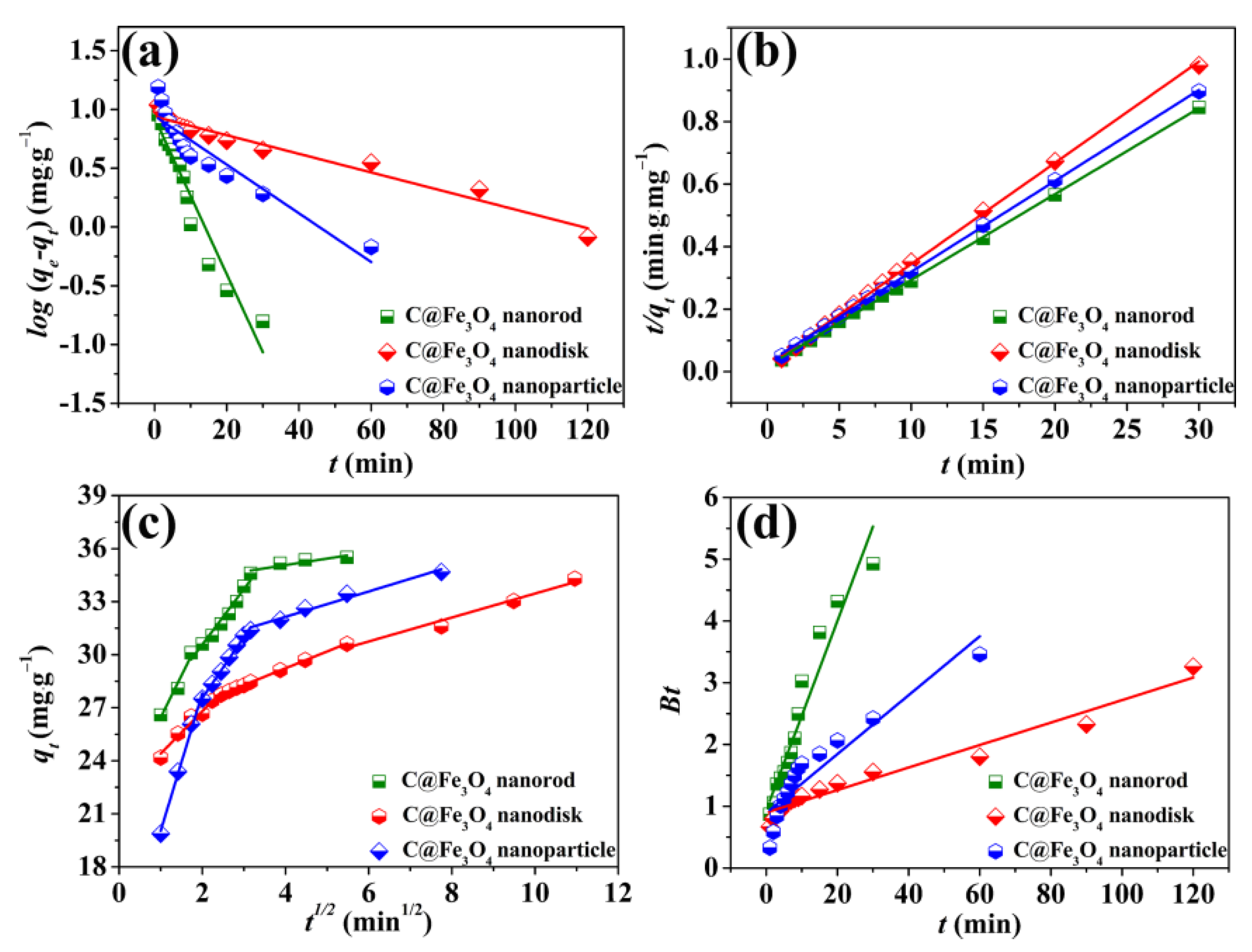

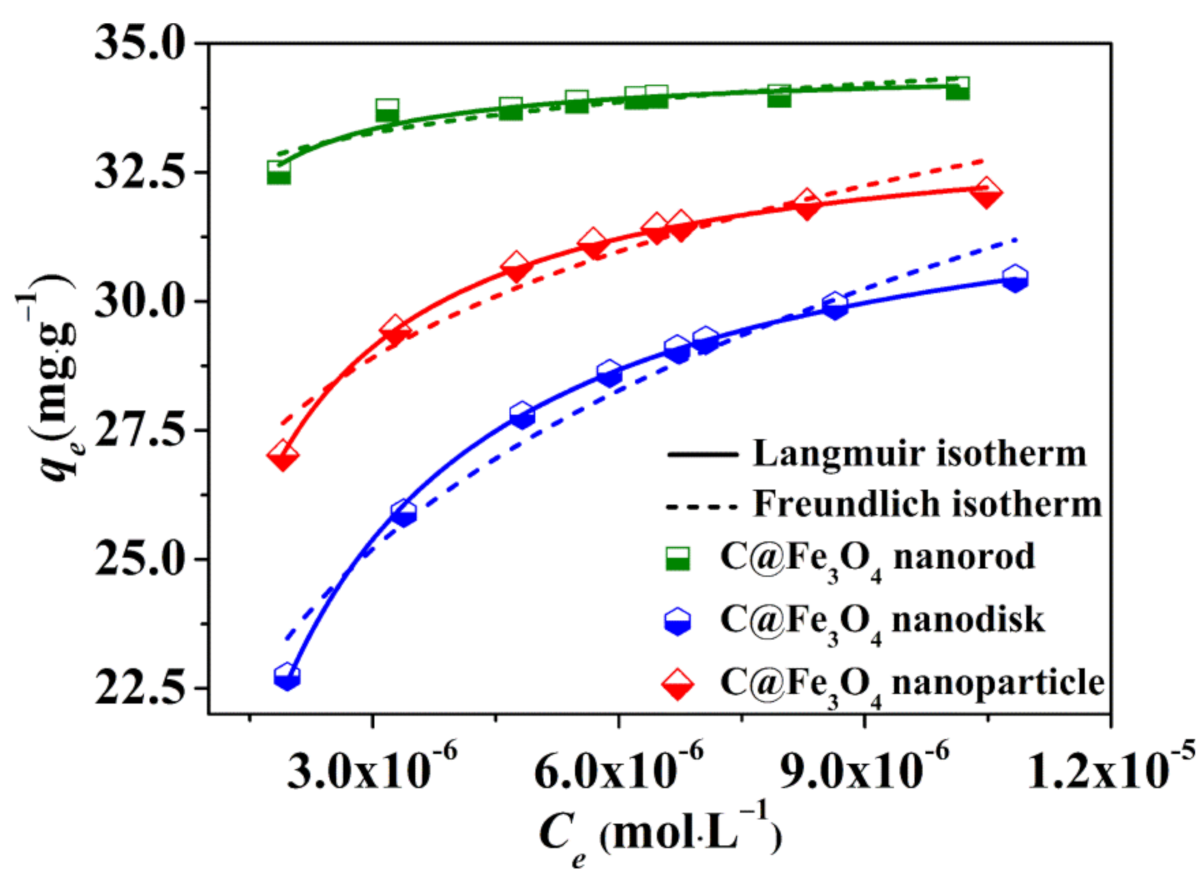

2.2. Adsorption Kinetics of the C@Fe3O4 Composites

2.3. Adsorption Kinetics of the C@Fe3O4 Composites

3. Experimental

3.1. Chemicals

3.2. Synthesis of C@Fe3O4 Nanorods

3.3. Characterization

3.4. Adsorption Experiment

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Sample Availability

References

- Shayesteh, H.; Rahbar-Kelishami, A.; Norouzbeigi, R. Evaluation of natural and cationic surfactant modified pumice for congo red removal in batch mode: Kinetic, equilibrium, and thermodynamic studies. J. Mol. Liq. 2016, 221, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shayesteh, H.; Rahbar-Kelishami, A.; Norouzbeigi, R. Adsorption of malachite green and crystal violet cationic dyes from aqueous solution using pumice stone as a low-cost adsorbent: Kinetic, equilibrium, and thermodynamic studies. Desalin. Water Treat. 2016, 57, 12822–12831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Budnyak, T.M.; Aminzadeh, S.; Pylypchuk, I.V.; Sternik, D.; Tertykh, V.A.; LindstrÖm, M.E.; Sevastyanova, O. Methylene blue dye sorption by hybrid materials from technical lignins. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2018, 6, 4997–5007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelhamid, H.N.; Zou, X. Template-free and room temperature synthesis of hierarchical porous zeolitic imidazolate framework nanoparticles and their dye and CO2 sorption. Green Chem. 2018, 20, 1074–1084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ismail, B.; Hussain, S.T.; Akram, S. Adsorption of methylene blue onto spinel magnesium aluminate nanoparticles: Adsorption isotherms, kinetic and thermodynamic studies. Chem. Eng. J. 2013, 219, 395–402. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.C.; Ni, S.Z.; Wang, X.J.; Zhang, W.H.; Lagerquist, L.; Qin, M.H.; WillfÖr, S.; Xu, C.L.; Fatehi, P. Ultrafast adsorption of heavy metal ions onto functionalized lignin-based hybrid magnetic nanoparticles. Chem. Eng. J. 2019, 372, 82–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman-Setayesh, M.R.; Kelishami, A.R.; Shayesteh, H. Equilibrium, kinetic, and thermodynamic applications for methylene blue removal using Buxus sempervirens leaf powder as a powerful low-cost adsorbent. J. Part. Sci. Technol. 2019, 5, 161–170. [Google Scholar]

- Peng, N.; Hu, D.N.; Zeng, J.; Li, Y.; Liang, L.; Chang, C.Y. Superabsorbent cellulose–clay nanocomposite hydrogels for highly efficient removal of dye in water. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2016, 4, 7217–7224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zambare, R.; Song, X.X.; Bhuvana, S.; Antony Prince, J.S.; Nemade, P. Ultrafast dye removal using ionic liquid–graphene oxide sponge. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2017, 5, 6026–6035. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.J.; Jing, Y.; Xie, Y.; Luo, G.S.; Yao, H.B. Controllable preparation and catalytic performance of heterogeneous fenton-like α-Fe2O3/crystalline glass microsphere catalysts. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2017, 56, 13751–13759. [Google Scholar]

- Deng, P.; Liu, M.; Lv, Z.X. Adsorption mechanism of methyl blue onto magnetic Co0.5Zn0.5Fe2O4 nanoparticles synthesized via the nitrate-alcohol solution combustion process. AIP Adv. 2020, 10, 095005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Pan, S.; Yu, Q.M.; Ding, X.; Liu, R.J. Adsorption mechanism and electrochemical performance of methyl blue onto magnetic Ni(1-x-y)CoyZnxFe2O4 nanoparticles prepared via the rapid-combustion process. Ceram. Int. 2020, 46, 3614–3622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, B.Y.; Bai, Y.T.; Pan, Z.; Xu, J.Y.; Wang, Q.Y.; Wang, X.; Lv, G.J.; Zhou, J.H. pH fractionated lignin for the preparation of lignin-based magnetic nanoparticles for the removal of methylene blue dye. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2022, 295, 121302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iram, M.; Guo, C.; Guan, Y.P.; Ishfaq, A.; Liu, H.Z. Adsorption and magnetic removal of neutral red dye from aqueous solution using Fe3O4 hollow nanospheres. J. Hazard. Mater. 2010, 181, 1039–1050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weng, C.; Lin, Y.T.; Yeh, C.L.; Sharma, Y.C. Magnetic Fe3O4 nanoparticles for adsorptive removal of acid dye (new coccine) from aqueous solutions. Water Sci. Technol. 2010, 62, 844–851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.H.; Yan, B.; Wu, H.; Kong, Q.H. Self-assembled synthesis of carbon-coated Fe3O4 composites with firecracker-like structures from catalytic pyrolysis of polyamide. RSC Adv. 2014, 4, 6991–6997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, H.L.; Ren, G.K.; Zhong, Y.J.; Xu, D.H.; Zhang, Z.Y.; Wang, X.L.; Yang, X.S. Fe3O4@C nanoparticles synthesized by in situ solid-phase method for removal of methylene blue. Nanomaterials 2021, 11, 330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.Y.; Kong, J.L. Novel magnetic Fe3O4@C nanoparticles as adsorbents for removal of organic dyes from aqueous solution. J. Hazard.Mater. 2011, 193, 325–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ai, L.H.; Zhang, C.Y.; Chen, Z.L. Removal of methylene blue from aqueous solution by a solvothermal-synthesized graphene/magnetite composite. J. Hazard. Mater. 2011, 192, 1515–1524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banerjee, A.; Gokhale, R.; Bhatnagar, S.; Jog, J.; Bhardwaj, M.; Lefez, B.; Hannoyerc, B.; Ogale, S. MOF derived porous carbon–Fe3O4 nanocomposite as a high performance, recyclable environmental superadsorbent. J. Mater. Chem. 2012, 22, 19694–19699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, J.T.; Wang, Z.; Wang, L.; Liu, R.J. Preparation, surface modification, and characteristic of α-Fe2O3 nanoparticles. J. Nanosci. Nanotechnol. 2020, 20, 3031–3037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, M.; Hu, X.F.; Tu, C.; Zhang, H.B.; Song, F.; Luo, Y.M.; Christie, P. Sorption mechanisms of diphenylarsinic acid on ferrihydrite, goethite and hematite using sequential extraction, FTIR measurement and XAFS spectroscopy. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 669, 991–1000. [Google Scholar]

- Cao, C.Y.; Qu, J.; Yan, W.S.; Zhu, J.F.; Wu, Z.Y.; Song, W.G. Low-cost synthesis of flowerlike α-Fe2O3 nanostructures for heavy metal ion removal: Adsorption property and mechanism. Langmuir 2012, 28, 4573–4579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hitam, C.N.C.; Jalil, A.A. A review on exploration of Fe2O3 photocatalyst towards degradation of dyes and organic contaminants. J. Env. Manag. 2020, 258, 110050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.N.; Gao, W.Q.; Zhao, Z.H.; Zhao, L.L.; Claverie, J.P.; Zhang, X.F.; Wang, J.J.; Liu, H.; Sang, Y.H. Efficient photo-electrochemical water splitting based on hematite nanorods doped with phosphorus. Appl. Cat. B. Environ. 2019, 248, 388–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shoorangiz, M.; Shariatifard, L.; Roshan, H.; Mirzaei, A. Selective ethanol sensor based on α-Fe2O3 nanoparticles. Inorg. Chem. Commun. 2021, 133, 108961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balaga, R.; Ramji, K.; Subrahmanyam, T.; Babu, K.R. Effect of temperature, total weight concentration and ratio of Fe2O3 and f-MWCNTs on thermal conductivity of water based hybrid nanofluids. Mater. Today Proc. 2019, 18, 4992–4999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y.; Zhang, A.Q.; Zhang, H.; Ding, G.Q.; Zhang, L.S. A facile route to achieve Fe2O3 hollow sphere anchored on carbon nanotube for application in lithium-ion battery. Inorg. Chem. Commun. 2020, 111, 107633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.D.; Cao, R.G.; Jeong, S.; Cho, J. Spindle-like mesoporous α-Fe2O3 anode material prepared from MOF template for high-rate lithium batteries. Nano Lett. 2012, 12, 4988–4991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.J.; Xiao, G.; Wang, T.S.; Ouyang, Q.Y.; Qi, L.H.; Ma, Y.; Gao, P.; Zhu, C.L.; Cao, M.S.; Jin, H.B. Porous Fe3O4/carbon core/shell nanorods: Synthesis and electromagnetic properties. J. Phys. Chem. C 2011, 115, 13603–13608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pol, V.G.; Daemen, L.L.; Vogel, S.; Chertkov, G. Solvent-free fabrication of ferromagnetic Fe3O4 octahedra. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2010, 49, 920–924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chin, K.C.; Chong, G.L.; Poh, C.K.; Van, L.H.; Sow, C.H.; Lin, J.Y.; Wee, A.T.S. Large-scale synthesis of Fe3O4 nanosheets at low temperature. J. Phys. Chem. C 2007, 111, 9136–9141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phase, D.M.; Tiwari, S.; Prakash, R.; Dubey, A.; Sathe, V.G.; Choudhary, R.J. Raman study across Verwey transition of epitaxial Fe3O4 thin films on MgO (100) substrate grown by pulsed laser deposition. J. Appl. Phys. 2006, 100, 123703–123707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, D.Y.; Myung, S.T. Carbon-coated magnetite embedded on carbon nanotubes for rechargeable lithium and sodium batteries, ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2014, 6, 11749–11757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jia, C.J.; Sun, L.D.; Yan, Z.G.; Pang, Y.C.; You, L.P.; Yan, C.H. Iron oxide tube-in-tube nanostructures. J. Phys. Chem. C 2007, 111, 13022–13027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, L.R.; Lu, X.F.; Bian, X.J.; Zhang, W.J.; Wang, C. Constructing carbon-coated Fe3O4 microspheres as antiacid and magnetic support for palladium nanoparticles for catalytic applications. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2011, 3, 35–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, L.Q.; Zhang, W.Q.; Ding, Y.W.; Peng, Y.Y.; Zhang, S.Y.; Yu, W.C.; Qian, Y.T. Formation, characterization, and magnetic properties of Fe3O4 nanowires encapsulated in carbon microtubes. J. Phys. Chem. B 2004, 108, 10859–10862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, F.Y.; Chen, C.L.; Wang, Q.; Chen, Q.W. Synthesis of carbon–Fe3O4 coaxial nanofibres by pyrolysis of ferrocene in supercritical carbon dioxide. Carbon 2007, 45, 727–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazario, E.; Sánchez-Marcos, J.; Menéndez, N.; Herrasti, P.; García-Hernández, M.; Muñoz-Bonilla, A. One-pot electrochemical synthesis of polydopamine coated magnetite nanoparticles. RSC Adv. 2014, 4, 48353–48361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lagergren, S. About the theory of so-called adsorption of soluble substances. K. Sven. Vetenskapsakad. Handl. 1898, 24, 1–39. [Google Scholar]

- Qu, L.L.; Han, T.T.; Luo, Z.J.; Liu, C.C.; Mei, Y.; Zhu, T. One-step fabricated Fe3O4@C core–shell composites for dye removal: Kinetics, equilibrium and thermodynamics. J. Phys. Chem. Solids 2015, 78, 20–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, L.S.; Guang, C.Y.; Liu, Y.; Su, Z.Q.; Gong, S.D.; Yao, Y.J.; Wang, Y.P. Adsorption behavior of dyes from an aqueous solution onto composite magnetic lignin adsorbent. Chemosphere 2020, 246, 125757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boyd, G.E.; Adamson, A.W.; Meyers, L.S. The exchange adsorption of ions from aqueous solutions by organic zeolites. 2. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1947, 69, 2836–2848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Langmuir, I. The adsorption of gases on plane surfaces of glass, mica and platinum. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1918, 40, 1361–1403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freundlich, H.M.F. Over the adsorption in solution. Z. Phys. Chem. 1906, 57, 385–471. [Google Scholar]

- Tian, Y.; Wu, M.; Lin, X.B.; Huang, P.; Huang, Y. Synthesis of magnetic wheat straw for arsenic adsorption. J. Hazard. Mater. 2011, 193, 10–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, A.K.; Arockiadoss, T.; Ramaprabhu, S. Study of removal of azo dye by functionalized multi walled carbon nanotubes. Chem. Eng. J. 2010, 162, 1026–1034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, H.Y.; Fu, Y.Q.; Jiang, R.; Yao, J.; Liu, L.; Chen, Y.W.; Xiao, L.; Zeng, G.M. Preparation, characterization and adsorption properties of chitosan modified magnetic graphitized multi-walled carbon nanotubes for highly effective removal of a carcinogenic dye from aqueous solution. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2013, 285, 865–873. [Google Scholar]

| Samples | Nanorod | Nanodisk | Nanoparticle |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ms (emu·g−1) | 50.94 | 39.10 | 26.46 |

| Mr (emu·g−1) | 20.39 | 10.75 | 6.65 |

| Hc (Oe) | 238.86 | 285.59 | 195.58 |

| Samples | Models | Pseudo-First-Order | Pseudo-Second-Order | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C@Fe3O4 nanorod | Parameters | k1 (min−1) | 0.1531 | k2 (g·mg·min−1) | 0.0205 |

| qe (mg·g−1) | 8.4826 | qe (mg·g−1) | 36.36 | ||

| R2 | 0.9290 | R2 | 0.9996 | ||

| C@Fe3O4 nanodisk | Parameters | k1 (min−1) | 0.0182 | k2 (g·mg·min−1) | 8.5428 × 10−3 |

| qe (mg·g−1) | 8.6938 | qe (mg·g−1) | 34.0136 | ||

| R2 | 0.9572 | R2 | 0.9985 | ||

| C@Fe3O4 nanoparticle | Parameters | k1 (min−1) | 0.0477 | k2 (g·mg·min−1) | 0.0120 |

| qe (mg·g−1) | 8.8089 | qe (mg·g−1) | 35.1494 | ||

| R2 | 0.8641 | R2 | 0.9997 | ||

| Sample | Langmuir | Freundlich | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Qmax (mg·g−1) | b (L·mol−1) | R2 | Kf (mg·g−1) | n | R2 | |

| C@Fe3O4 nanorod | 34.54 | 9.27 × 106 | 0.9229 | 46.12 | 38.93 | 0.7791 |

| C@Fe3O4 nanodisk | 32.94 | 1.12 × 106 | 0.9990 | 208.61 | 6.02 | 0.9549 |

| C@Fe3O4 nanoparticle | 33.64 | 2.15 × 106 | 0.9991 | 102.17 | 10.07 | 0.9295 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Duan, S.; Liu, J.; Pang, Y.; Lin, F.; Meng, X.; Tang, K.; Li, J. A Generalized Method for the Synthesis of Carbon-Encapsulated Fe3O4 Composites and Its Application in Water Treatment. Molecules 2022, 27, 6812. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules27206812

Duan S, Liu J, Pang Y, Lin F, Meng X, Tang K, Li J. A Generalized Method for the Synthesis of Carbon-Encapsulated Fe3O4 Composites and Its Application in Water Treatment. Molecules. 2022; 27(20):6812. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules27206812

Chicago/Turabian StyleDuan, Shengxia, Jian Liu, Yanling Pang, Feng Lin, Xiangyan Meng, Ke Tang, and Jiaxing Li. 2022. "A Generalized Method for the Synthesis of Carbon-Encapsulated Fe3O4 Composites and Its Application in Water Treatment" Molecules 27, no. 20: 6812. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules27206812

APA StyleDuan, S., Liu, J., Pang, Y., Lin, F., Meng, X., Tang, K., & Li, J. (2022). A Generalized Method for the Synthesis of Carbon-Encapsulated Fe3O4 Composites and Its Application in Water Treatment. Molecules, 27(20), 6812. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules27206812