Straightforward Regio- and Diastereoselective Synthesis, Molecular Structure, Intermolecular Interactions and Mechanistic Study of Spirooxindole-Engrafted Rhodanine Analogs

Abstract

:1. Introduction

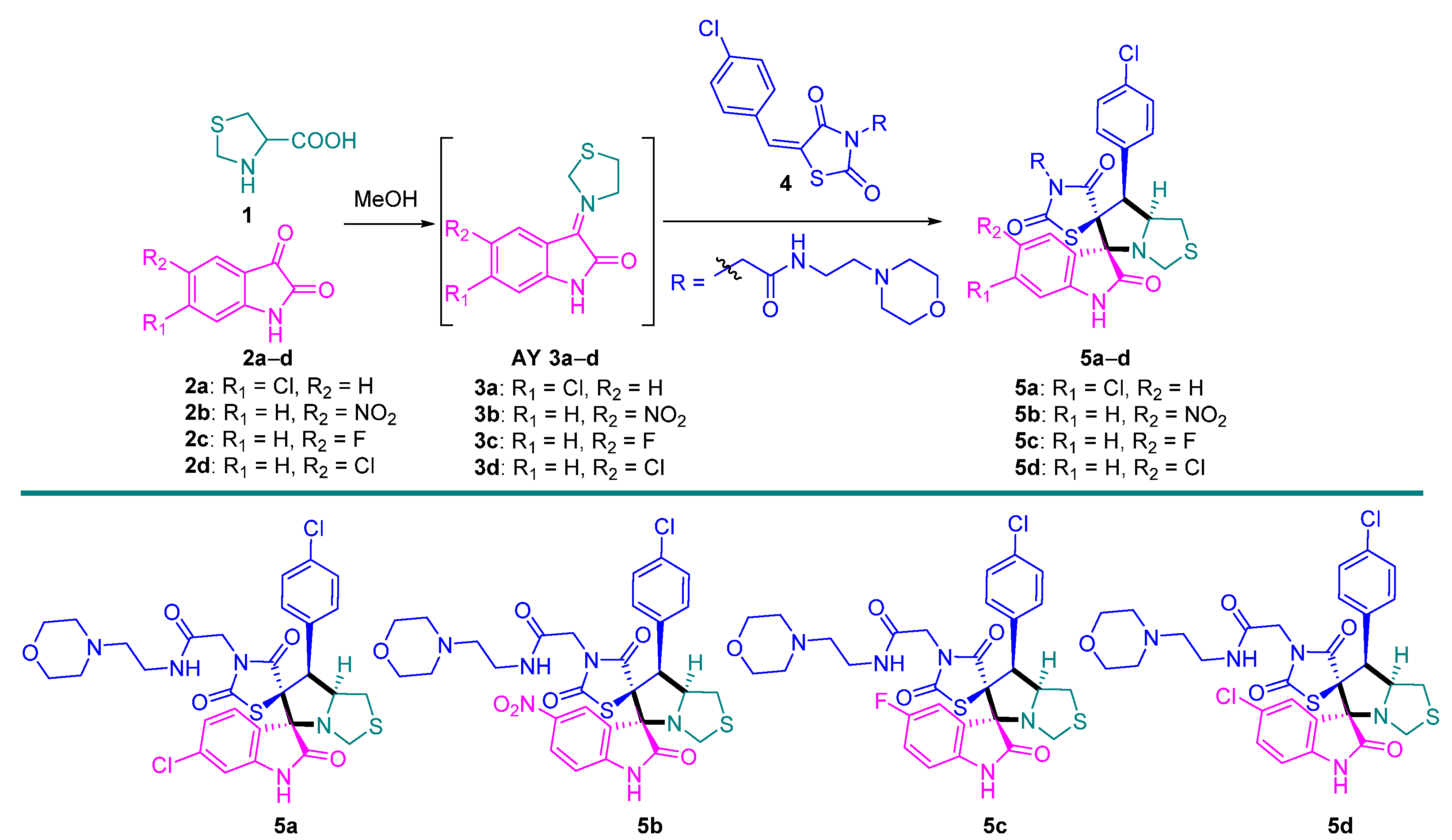

2. Results and Discussion

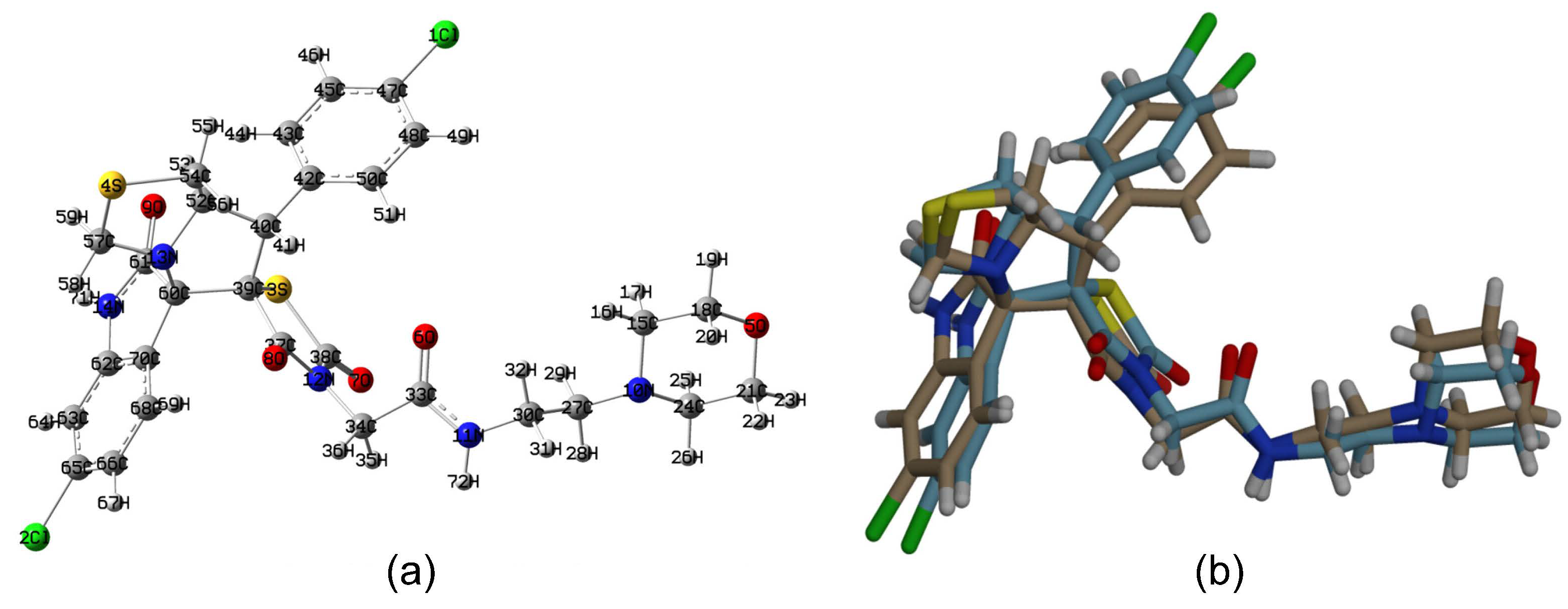

2.1. Crystal Structure Description

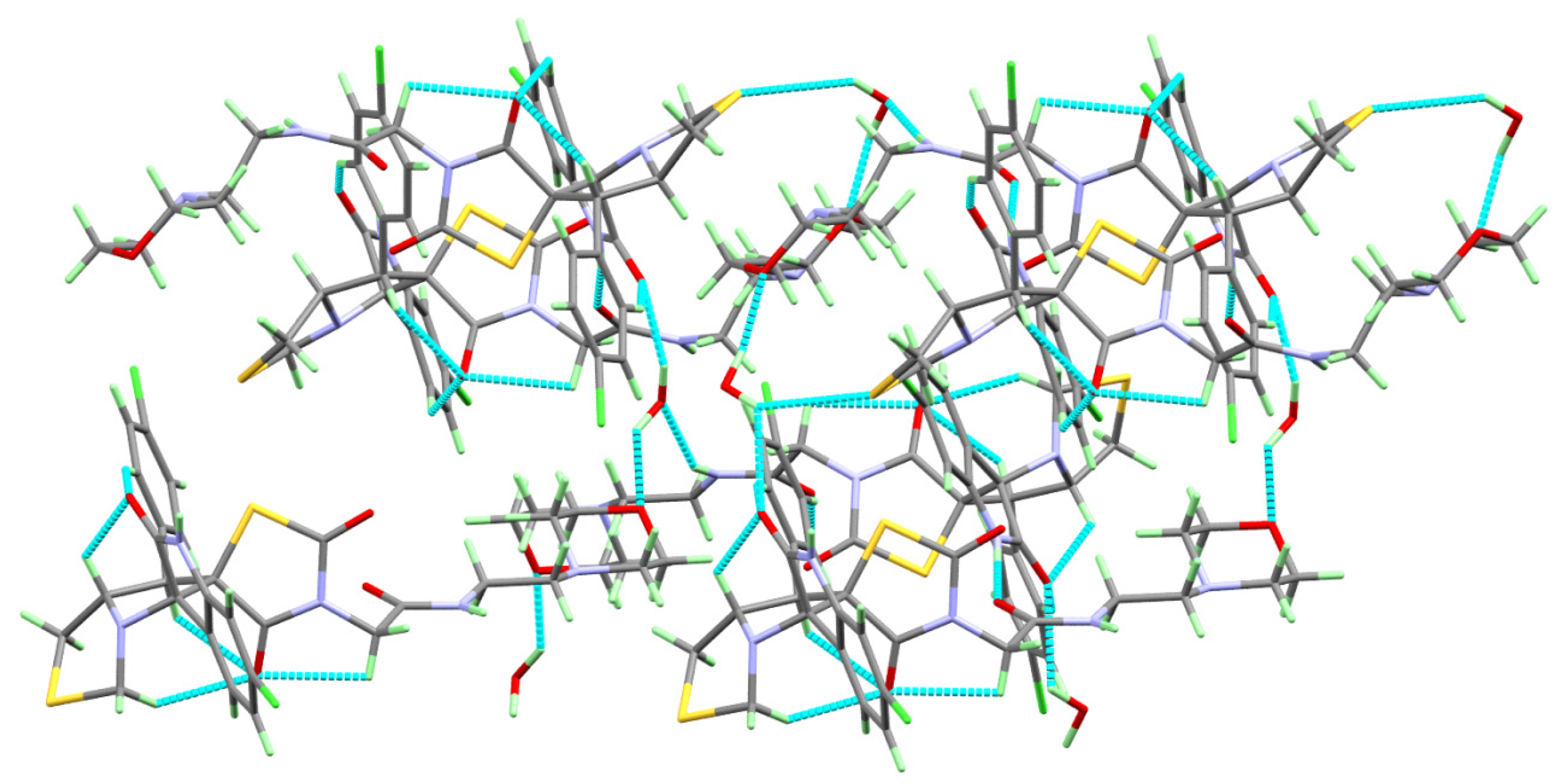

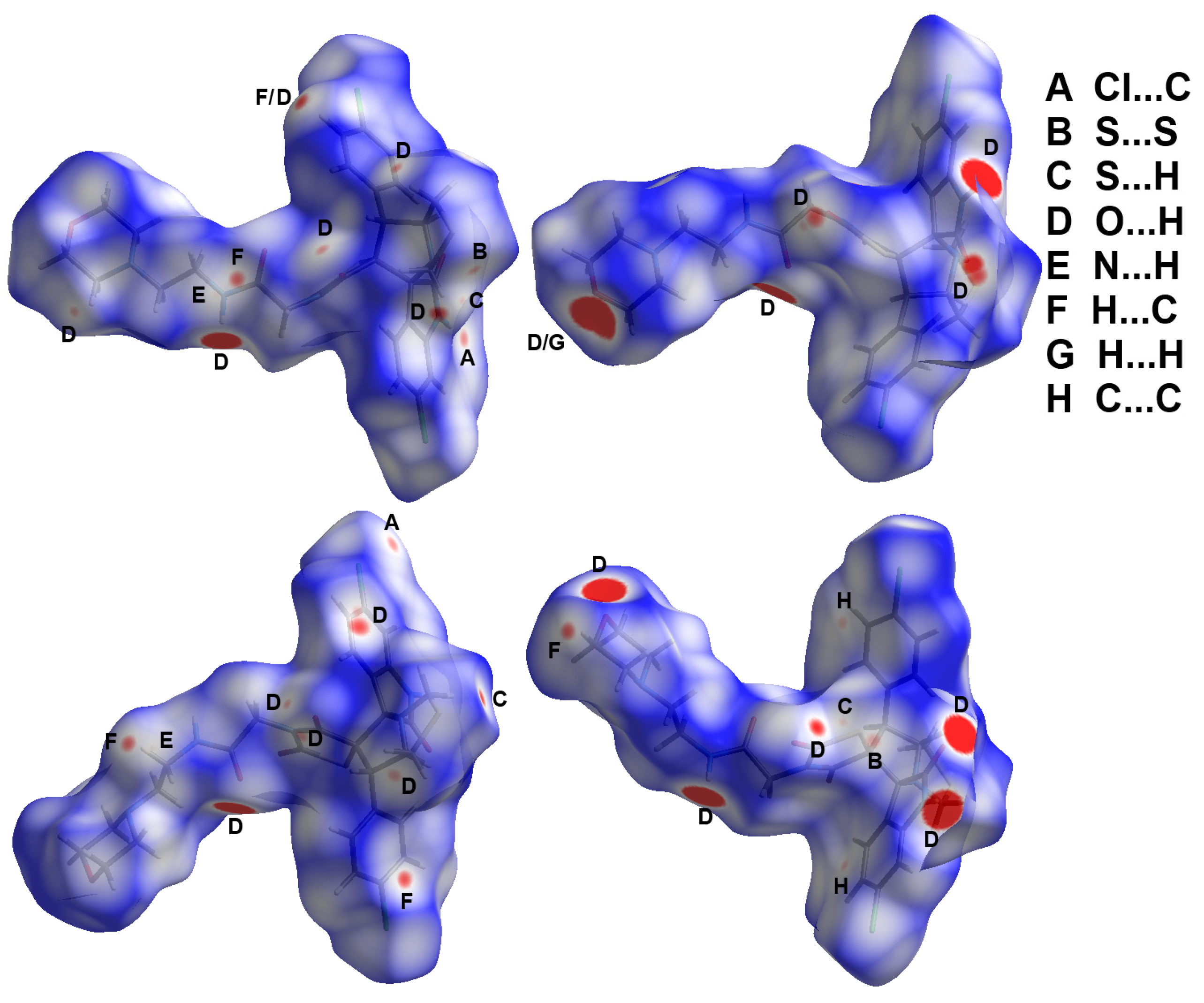

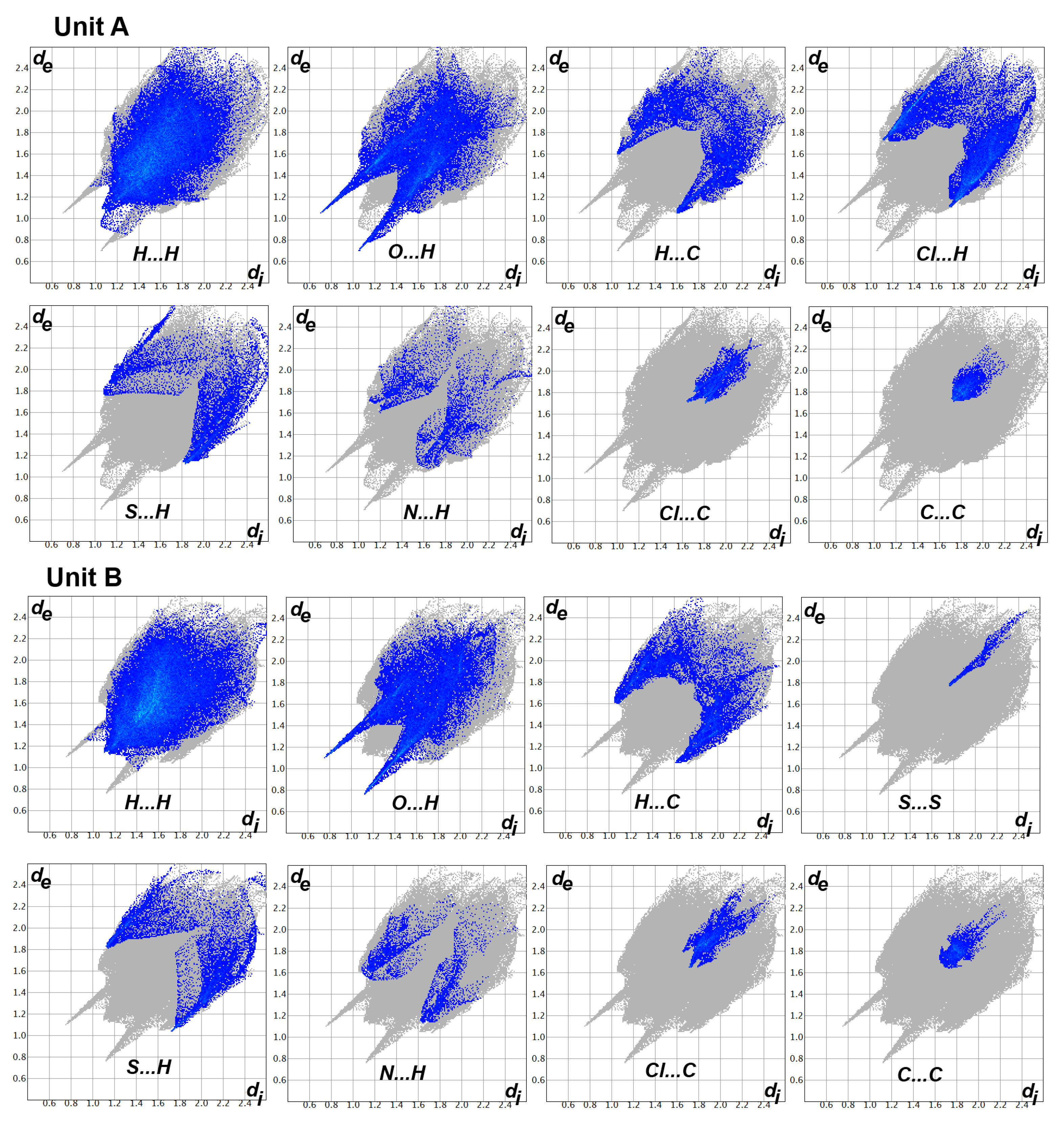

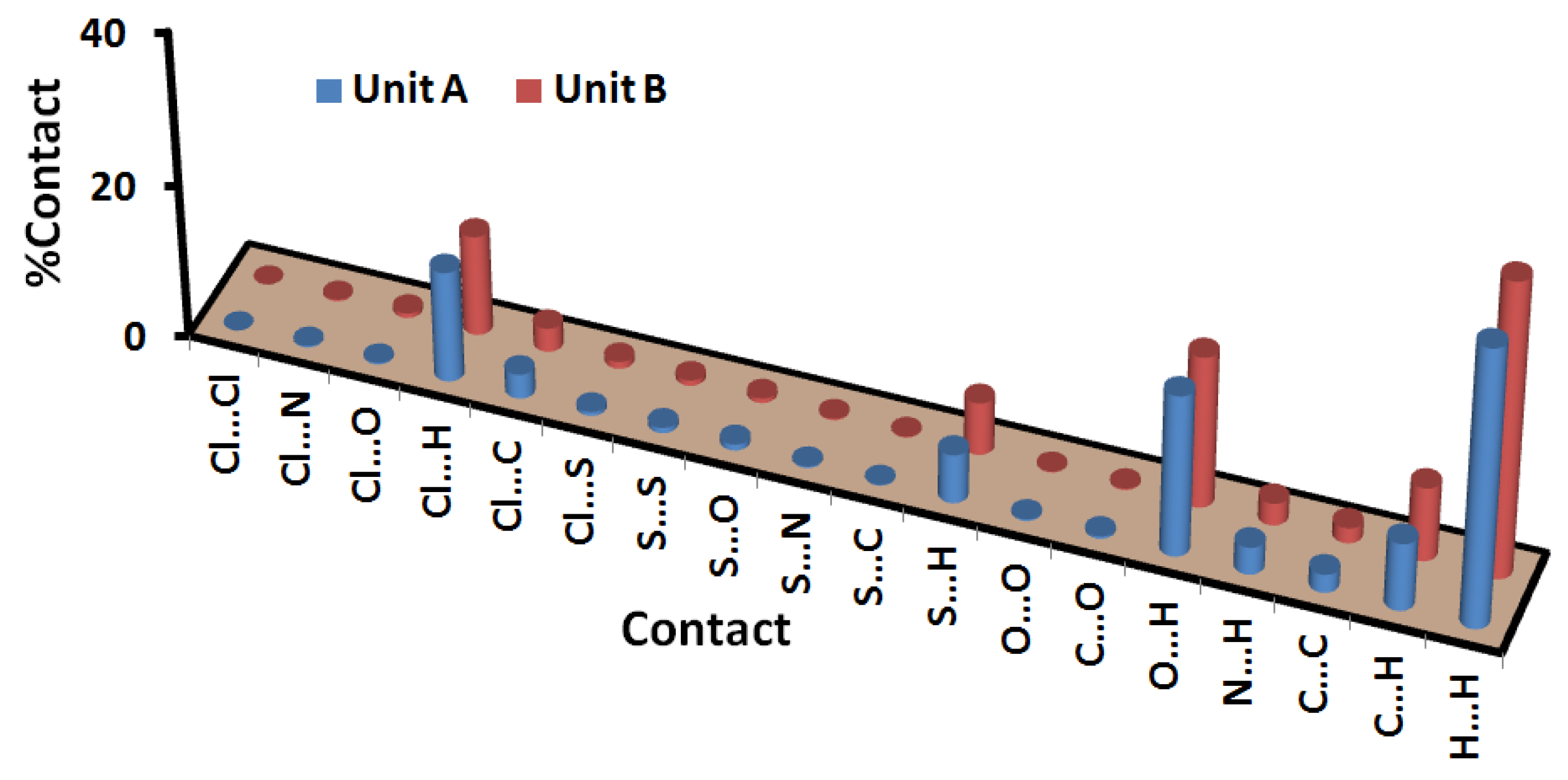

2.2. Analysis of Molecular Packing

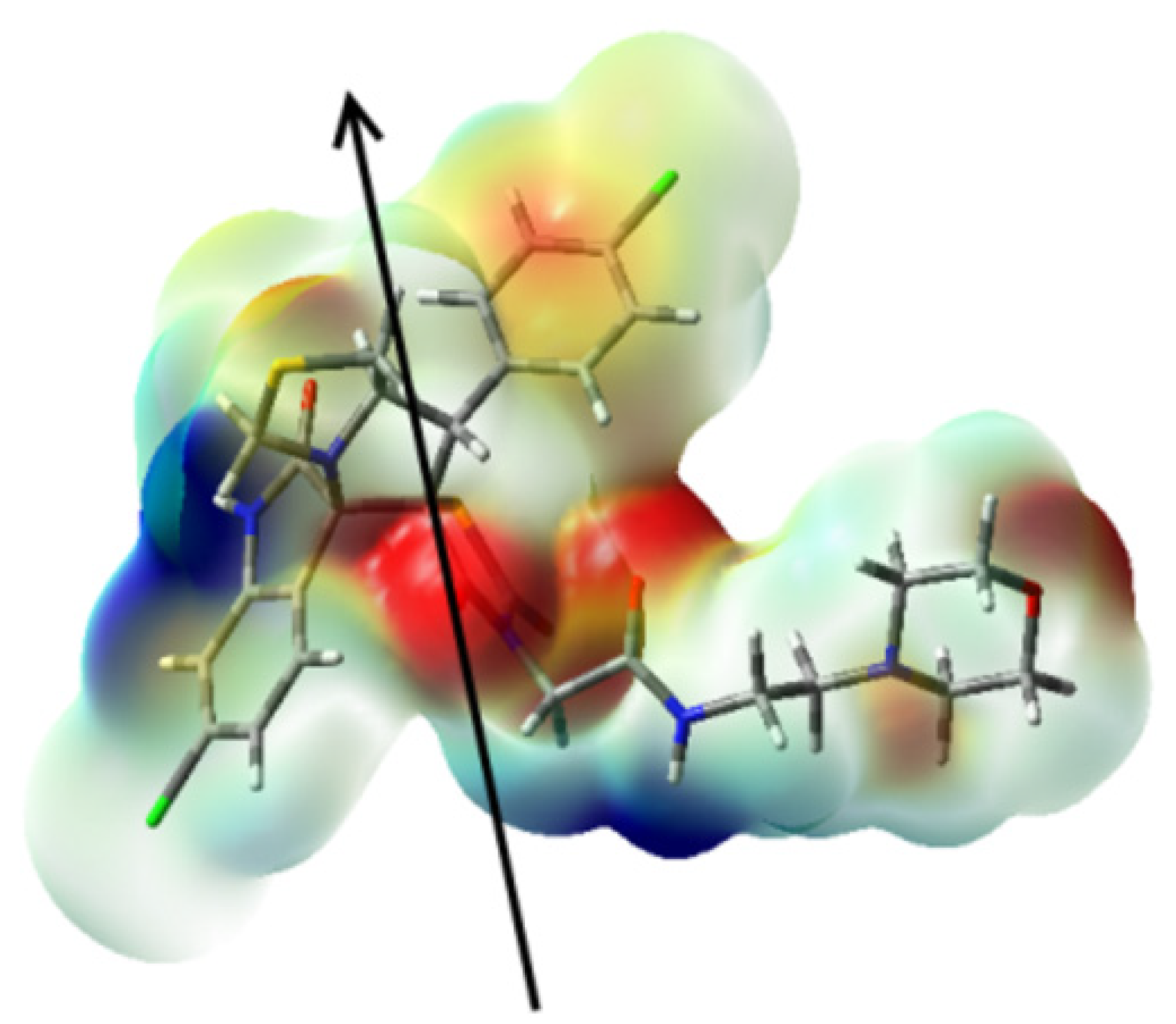

2.3. DFT Studies of the Structure of 5a

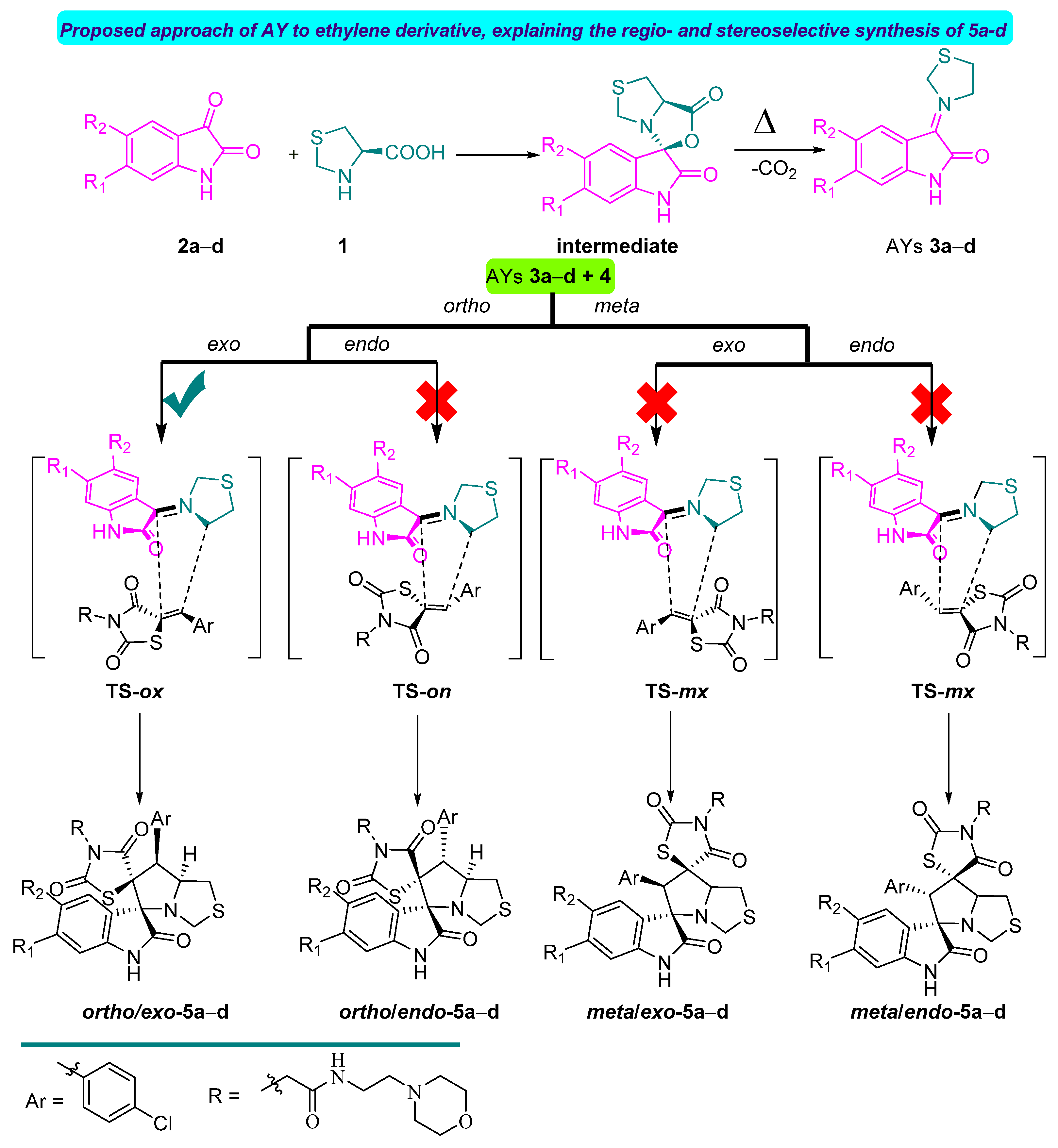

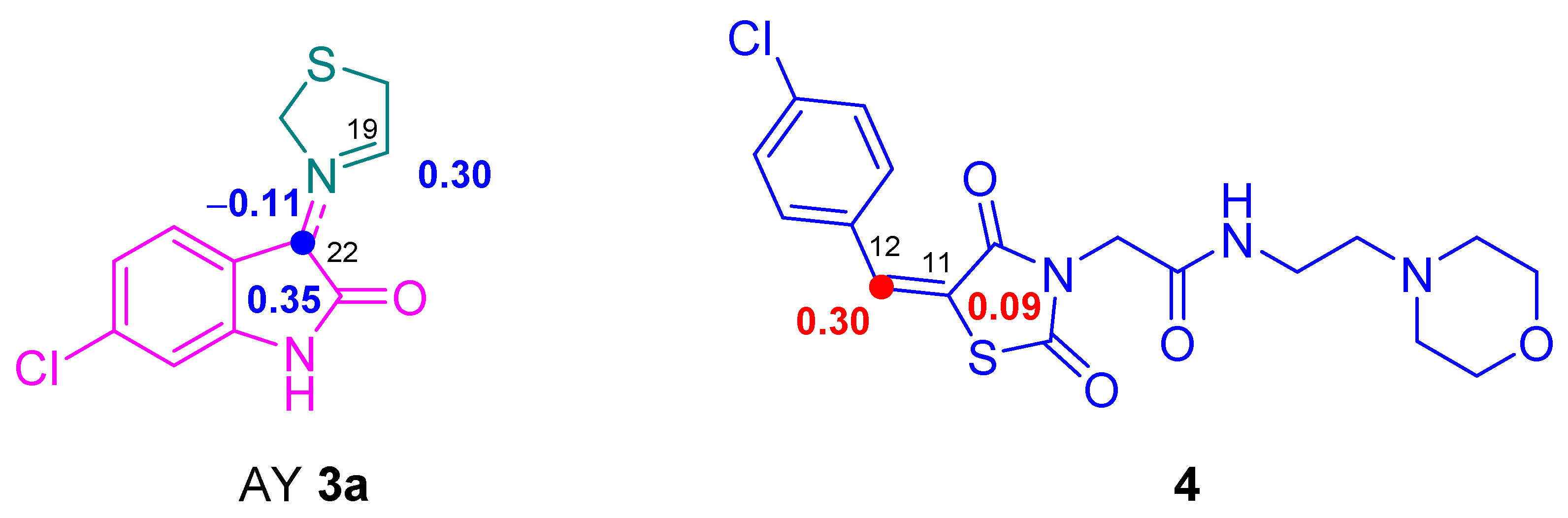

2.4. Conceptual DFT Analysis of the 32CA Reaction of AYs 3a–d with Ethylene Derivative 4

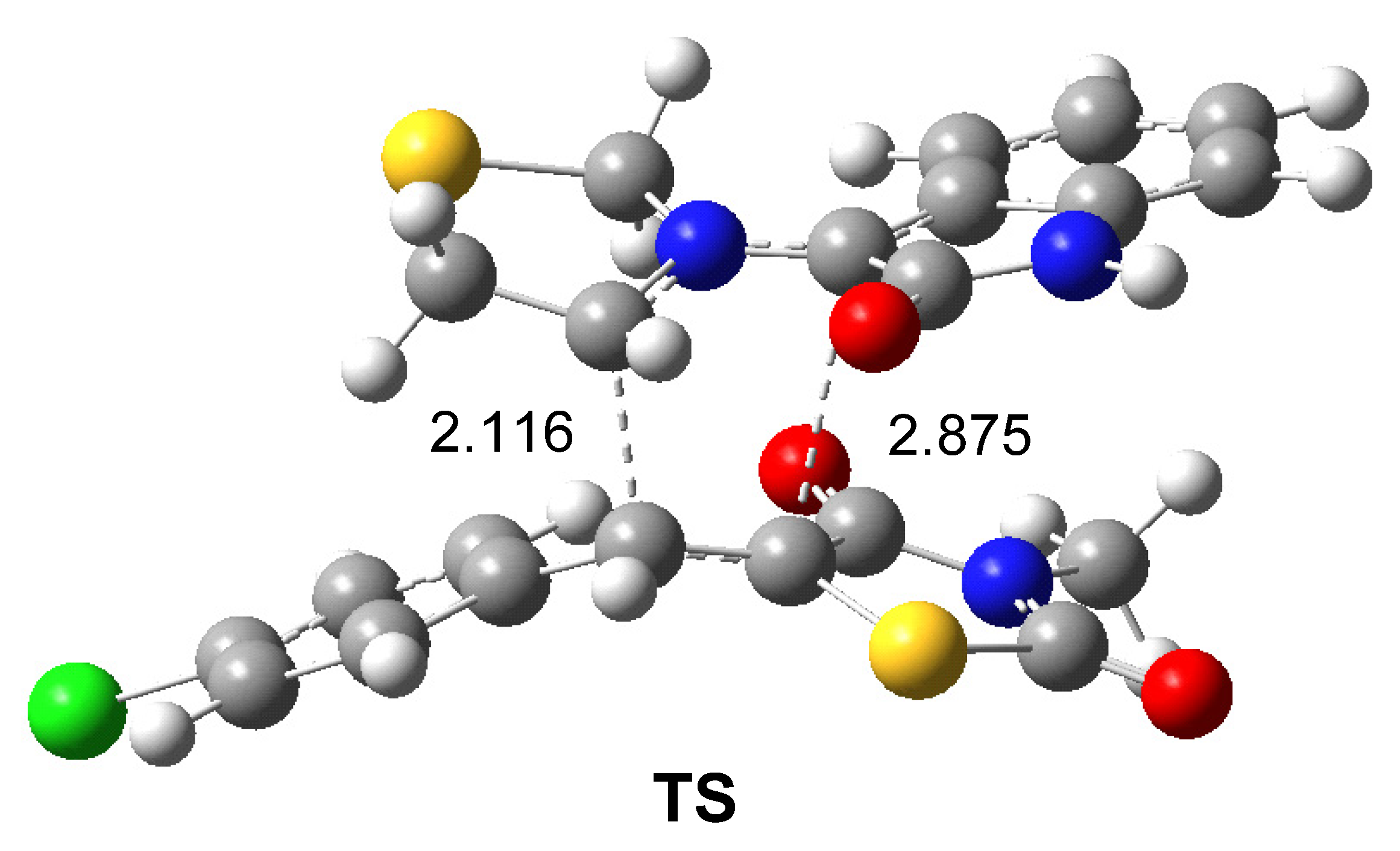

2.5. Study of the Reaction Mechanism

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. General Notes

3.2. Synthesis of Compound 4

3.3. General Method for the Synthesis of 5a–d

- 2-((3S,6′S,7′S,7a′S)-6-chloro-7′-(4-chlorophenyl)-2,2″,4″-trioxo-7′,7a′-dihydro-1′H,3′H-dispiro[indoline-3,5′-pyrrolo[1,2-c]thiazole-6′,5″-thiazolidin]-3″-yl)-N-(2-morpholinoethyl)acetamide 5a

- 2-((3S,6′S,7′S,7a′S)-7′-(4-chlorophenyl)-5-nitro-2,2″,4″-trioxo-7′,7a′-dihydro-1′H,3′H-dispiro[indoline-3,5′-pyrrolo[1,2-c]thiazole-6′,5″-thiazolidin]-3″-yl)-N-(2-morpholinoethyl)acetamide 5b

- 2-((3S,6′S,7′S,7a′S)-7′-(4-chlorophenyl)-5-fluoro-2,2″,4″-trioxo-7′,7a′-dihydro-1′H,3′H-dispiro[indoline-3,5′-pyrrolo[1,2-c]thiazole-6′,5″-thiazolidin]-3″-yl)-N-(2-morpholinoethyl)acetamide 5c

- 2-((3S,6′S,7′S,7a′S)-5-chloro-7′-(4-chlorophenyl)-2,2″,4″-trioxo-7′,7a′-dihydro-1′H,3′H-dispiro[indoline-3,5′-pyrrolo[1,2-c]thiazole-6′,5″-thiazolidin]-3″-yl)-N-(2-morpholinoethyl)acetamide 5d

3.4. Crystal Structure Determination of 5a

3.5. Hirshfeld Surface Analysis

3.6. Computational Methods

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Sample Availability

References

- Kaminskyy, D.; Kryshchyshyn, A.; Lesyk, D. Recent developments with rhodanine as a scaffold for drug discovery. Expert Opin. Drug Discov. 2017, 12, 1233–1252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mousavi, S.M.; Zarei, M.; Hashemi, S.A.; Babapoor, A.; Amani, A.M. A conceptual review of rhodanine: Current applications of antiviral drugs, anticancer and antimicrobial activities. Artif. Cells Nanomed. Biotechnol. 2019, 47, 1132–1148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Jiang, H.; Zhang, W.J.; Li, P.H.; Wang, J.; Dong, C.Z.; Zhang, K.; Chen, H.X.; Du, Z.Y. Synthesis and biological evaluation of novel carbazole-rhodanine conjugates as topoisomerase II inhibitors. Bioorgan. Med. Chem. Lett. 2018, 28, 1320–1323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Krátký, M.; Štěpánková, Š.; Vorčáková, K.; Vinšová, J. Synthesis and in vitro evaluation of novel rhodanine derivatives as potential cholinesterase inhibitors. Bioorgan. Chem. 2016, 68, 23–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shafii, N.; Khoobi, M.; Amini, M.; Sakhteman, A.; Nadri, H.; Moradi, A.; Emami, S.; Saeedian Moghadam, E.; Foroumadi, A.; Shafiee, A. Synthesis and biological evaluation of 5- benzylidenerhodanine-3-acetic acid derivatives as AChE and 15-LOX inhibitors. J. Enzyme Inhib. Med. Chem. 2015, 30, 389–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ramkumar, K.; Yarovenko, V.N.; Nikitina, A.S.; Zavarzin, I.V.; Krayushkin, M.M.; Kovalenko, L.V.; Esqueda, A.; Odde, S.; Neamati, N. Design, synthesis and structure-activity studies of rhodanine derivatives as HIV-1 integrase inhibitors. Molecules 2010, 15, 3958–3992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lotfy, G.; Said, M.M.; El Sayed, H.; Al-Dhfyan, A.; Aziz, Y.M.A.; Barakat, A. Synthesis of new spirooxindole-pyrrolothiazoles derivatives: Anti-cancer activity and molecular docking. Bioorgan. Med. Chem. 2017, 25, 1514–1523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hotta, N.; Sakamoto, N.; Shigeta, Y.; Kikkawa, R.; Goto, Y.; Japan, D.N.S.G. Clinical investigation of epalrestat, an aldose reductase inhibitor, on diabetic neuropathy in Japan: Multicenter study. J. Diabetes Complicat. 1996, 10, 168–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.C.; Peng, Y.P.; Xie, Z.Z.; Wang, J.; Chen, M. Synthesis, α-glucosidase inhibition and molecular docking studies of novel thiazolidine-2,4-dione or rhodanine derivatives. MedChemComm 2017, 8, 1477–1484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bansal, G.; Singh, S.; Monga, V.; Thanikachalam, P.V.; Chawla, P. Synthesis and biological evaluation of thiazolidine-2,4-dione-pyrazole conjugates as antidiabetic, anti-inflammatory and antioxidant agents. Bioorgan. Chem. 2019, 92, 103271–103287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, L.; Wang, P.; Xu, L.; Gao, L.; Li, J.; Piao, H. Discovery of 1,3-diphenyl-1H-pyrazole derivatives containing rhodanine-3- alkanoic acid groups as potential PTP1B inhibitors. Bioorgan. Med. Chem. Lett. 2019, 29, 1187–1193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barakat, A.; Soliman, S.M.; Al-Majid, A.M.; Ali, M.; Islam, M.S.; Elshaier, Y.A.; Ghabbour, H.A. New spiro-oxindole constructed with pyrrolidine/thioxothiazolidin-4-one derivatives: Regioselective synthesis, x-ray crystal structures, Hirshfeld surface analysis, DFT, docking and antimicrobial studies. J. Mol. Strut. 2018, 1152, 101–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altowyan, M.S.; Atef, S.; Al-Agamy, M.H.; Soliman, S.M.; Ali, M.; Shaik, M.R.; Choudhary, M.I.; Ghabbour, H.A.; Barakat, A. Synthesis and characterization of a spiroindolone pyrothiazole analog via X-ray, biological, and computational studies. J. Mol. Struct. 2019, 1186, 384–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haddad, S.; Boudriga, S.; Porzio, F.; Soldera, A.; Askri, M.; Sriram, D.; Yogeeswari, P.; Knorr, M.; Rousselin, Y.; Kubicki, M.M. Synthesis of novel dispiropyrrolothiazoles by three-component 1,3-dipolar cycloaddition and evaluation of their antimycobacterial activity. RSC Adv. 2014, 4, 59462–59471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prado, E.G.; Gimenez, M.G.; De la Puerta Vázquez, R.; Sánchez, J.E.; Rodríguez, M.S. Antiproliferative effects of mitraphylline, a pentacyclic oxindole alkaloid of Uncaria tomentosa on human glioma and neuroblastoma cell lines. Phytomedicine 2007, 14, 280–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barakat, A.; Islam, M.S.; Ghawas, H.M.; Al-Majid, A.M.; El-Senduny, F.F.; Badria, F.A.; Elshaier, Y.A.M.; Ghabbour, H.A. Substituted spirooxindole derivatives as potent anticancer agents through inhibition of phosphodiesterase 1. RSC Adv. 2018, 8, 14335–14346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Haddad, S.; Boudriga, S.; Akhaja, T.N.; Raval, J.P.; Porzio, F.; Soldera, A.; Askri, M.; Knorr, M.; Rousselin, Y.; Kubicki, M.M.; et al. A strategic approach to the synthesis of functionalized spirooxindole pyrrolidine derivatives: In vitro antibacterial, antifungal, antimalarial and antitubercular studies. New J. Chem. 2015, 39, 520–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arun, Y.; Saranraj, K.; Balachandran, C.; Perumal, P.T. Novel spirooxindole—pyrrolidine compounds: Synthesis, anticancer and molecular docking studies. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2014, 74, 50–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Almansour, A.I.; Kumar, R.S.; Arumugam, N.; Basiri, A.; Kia, Y.; Ali, M.A.; Farooq, M.; Murugaiyah, V. A facile ionic liquid promoted synthesis, cholinesterase inhibitory activity and molecular modeling study of novel highly functionalized spiropyrrolidines. Molecules 2015, 20, 2296–2309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Lotfy, G.; Aziz, Y.M.A.; Said, M.M.; El Sayed, H.; El Sayed, H.; Abu-Serie, M.M.; Teleb, M.; Dömling, A.; Barakat, A. Molecular hybridization design and synthesis of novel spirooxindole-based MDM2 inhibitors endowed with BCL2 signaling attenuation; a step towards the next generation p53 activators. Bioorgan. Chem. 2021, 117, 105427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barakat, A.; Islam, M.S.; Ghawas, H.M.; Al-Majid, A.M.; El-Senduny, F.F.; Badria, F.A.; Elshaier, Y.A.; Ghabbour, H.A. Design and synthesis of new substituted spirooxindoles as potential inhibitors of the MDM2—p53 interaction. Bioorgan. Chem. 2019, 86, 598–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aziz, Y.M.A.; Lotfy, G.; Said, M.M.; El Ashry, E.S.H.; El Tamany, E.S.H.; Soliman, S.M.; Abu-Serie, M.M.; Teleb, M.; Yousuf, S.; Dömling, A.; et al. Design, synthesis, chemical and biochemical insights into novel hybrid spirooxindole-based p53-MDM2 inhibitors with potential Bcl2 signaling attenuation. Front. Chem. 2021, 9, 735236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barakat, A.; Islam, M.S.; Ali, M.; Al-Majid, A.M.; Alshahrani, S.; Alamary, A.S.; Yousuf, S.; Choudhary, M.I. Regio-and stereoselective synthesis of a new series of spirooxindole pyrrolidine grafted thiochromene scaffolds as potential anticancer agents. Symmetry 2021, 13, 1426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boudriga, S.; Haddad, S.; Murugaiyah, V.; Askri, M.; Knorr, M.; Strohmann, C.; Golz, C. Three-component access to functionalized spiropyrrolidine heterocyclic scaffolds and their cholinesterase inhibitory activity. Molecules 2020, 25, 1963–1985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Barakat, A.; Soliman, S.M.; Alshahrani, S.; Islam, M.S.; Ali, M.; Al-Majid, A.M.; Yousuf, S. Synthesis, X-ray single crystal, conformational analysis and cholinesterase inhibitory activity of a new spiropyrrolidine scaffold tethered benzo[b]thiophene analogue. Crystals 2020, 10, 120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Barakat, A.; Alshahrani, S.; Al-Majid, A.M.; Ali, M.; Altowyan, M.S.; Islam, M.S.; Alamary, A.S.; Ashraf, S.; Ul-Haq, Z. Synthesis of a new class of spirooxindole–benzo[b]thiophene-based molecules as acetylcholinesterase inhibitors. Molecules 2020, 25, 4671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barakat, A.; Al-Majid, A.M.; Lotfy, G.; Ali, M.; Mostafa, A.; Elshaier, Y.A. Drug repurposing of lactoferrin combination in a nanodrug delivery system to combat severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus-2 infection. Dr. Sulaiman Al Habib Med. J. 2021, 3, 104–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toumi, A.; Boudriga, S.; Hamden, K.; Sobeh, M.; Cheurfa, M.; Askri, M.; Knorr, M.; Strohmann, C.; Brieger, L. Synthesis, antidiabetic activity and molecular docking study of rhodanine-substitued spirooxindole pyrrolidine derivatives as novel α-amylase inhibitors. Bioorgan. Chem. 2021, 106, 104507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abd Alhameed, R.; Almarhoon, Z.; Bukhari, S.I.; El-Faham, A.; de la Torre, B.G.; Albericio, F. Synthesis and antimicrobial activity of a new series of thiazolidine-2,4-diones carboxamide and amino acid derivatives. Molecules 2020, 25, 105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Pace, C.N.; Fu, H.; Lee Fryar, K.; Landua, J.; Trevino, S.R.; Schell, D.; Thurlkill, R.L.; Imura, S.; Scholtz, J.M.; Gajiwala, K.; et al. Contribution of hydrogen bonds to protein stability. Protein Sci. 2014, 23, 652–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Etter, M.C. Hydrogen bonds as design elements in organic chemistry. J. Phys. Chem. 1991, 95, 4601–4610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domingo, L.R. Molecular electron density theory: A modern view of reactivity in organic chemistry. Molecules 2016, 21, 1319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ríos-Gutiérrez, M.; Domingo, L.R. Unravelling the mysteries of the [3 + 2] cycloaddition reactions. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2019, 2019, 267–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domingo, L.R.; Chamorro, E.; Pérez, P. Understanding the high reactivity of the azomethine ylides in [3 + 2] Cycloaddition Reactions. Lett. Org. Chem. 2010, 7, 432–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domingo, L.R.; Kula, K.; Ríos-Gutiérrez, M. Unveiling the reactivity of cyclic azomethine ylides in [3 + 2] cycloaddition reactions within the molecular electron density theory. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2020, 2020, 5938–5948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parr, R.G.; Yang, W. Density-Functional Theory of Atoms and Molecules; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Domingo, L.R.; Ríos-Gutiérrez, M.; Pérez, P. Applications of the conceptual density functional theory indices to organic chemistry reactivity. Molecules 2016, 21, 748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Domingo, L.R. A new C—C bond formation model based on the quantum chemical topology of electron density. RSC Adv. 2014, 4, 32415–32428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Domingo, L.R.; Ríos-Gutiérrez, M.; Pérez, P. A molecular electron density theory study of the participation of tetrazines in aza-Diels–Alder reactions. RSC Adv. 2020, 10, 15394–15405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Parr, R.G.; Szentpaly, L.V.; Liu, S. Electrophilicity index. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1999, 121, 1922–1924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domingo, L.R.; Chamorro, E.; Pérez, P. Understanding the reactivity of captodative ethylenes in polar cycloaddition reactions. A theoretical study. J. Org. Chem. 2008, 73, 4615–4624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chamorro, E.; Duque-Noreña, M.; Gutiérrez-Sánchez, N.; Rincón, E.L.R. Domingo, A close look to the oxaphosphetane formation along the Wittig reaction: A [2 + 2] cycloaddition? J. Org. Chem. 2020, 85, 6675–6686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aurell, M.J.; Domingo, L.R.; Pérez, P.; Contreras, R. A theoretical study on the regioselectivity of 1,3-dipolar cycloadditions using DFT-based reactivity indexes. Tetrahedron 2004, 60, 11503–11509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domingo, L.R.; Pérez, P.; Sáez, J.A. Understanding the local reactivity in polar organic reactions through electrophilic and nucleophilic Parr functions. RSC Adv. 2013, 3, 1486–1494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fukui, K. Formulation of the reaction coordinate. J. Phys. Chem. 1970, 74, 4161–4163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domingo, L.R.; Sáez, J.A.; Zaragozá, R.J.; Arnó, M. Understanding the participation of quadricyclane as nucleophile in polar [2σ + 2σ + 2π] cycloadditions toward electrophilic π molecules. J. Org. Chem. 2008, 73, 8791–8799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- CrysAlisPro. Rikagu Oxford Diffraction; Agilent Technologies Inc.: Oxfordshire, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Sheldrick, G.M. SHELXT–Integrated space-group and crystal-structure determination. Acta Crystallogr. Sect. A Found. Adv. 2015, 71, 3–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Sheldrick, G.M. Crystal structure refinement with SHELXL. Acta Crystallogr. Sect. C Struct. Chem. 2015, 71, 3–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hübschle, C.B.; Sheldrick, G.M.; Dittrich, B. ShelXle: A Qt graphical user interface for SHELXL. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 2011, 44, 1281–1284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Turner, M.J.; McKinnon, J.J.; Wolff, S.K.; Grimwood, D.J.; Spackman, P.R.; Jayatilaka, D.; Spackman, M.A. Crystal Explorer17. University of Western Australia, 2017. Available online: https://crystalexplorer.scb.uwa.edu.au/ (accessed on 20 June 2019).

- Frisch, M.J.; Trucks, G.W.; Schlegel, H.B.; Scuseria, G.E.; Robb, M.A.; Cheeseman, J.R.; Scalmani, G.; Barone, V.; Mennucci, B.; Petersson, G.A. Gaussian 09, Revision A02; Gaussian Inc.: Wallingford, CT, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Dennington, R., II; Keith, T.; Millam, J. (Eds.) GaussView; Version 4.1; Semichem Inc.: Shawnee Mission, KS, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

| 5a | |

|---|---|

| Empirical formula | C29H31Cl2N5O6S2 |

| fw | 680.61 |

| Temperature (K) | 120(2) |

| λ (Å) | 1.54184 |

| Crystal system | Monoclinic |

| Space group | P21 |

| a (Å) | 14.0397(2) |

| b (Å) | 15.9918(2) |

| c (Å) | 14.1488(2) |

| α (deg) | 90 |

| β (deg) | 109.439(2) |

| λ (deg) | 90 |

| V (Å3) | 2995.61(8) |

| Z | 4 |

| ρcalc (Mg/m3) | 1.509 |

| μ (Mo Kα) (mm−1) | 3.704 |

| No. of reflns. | 18,916 |

| Unique reflns. | 9558 |

| Completeness to θ = 67.684° | 99.9% |

| GOOF (F2) | 1.040 |

| Rint | 0.0321 |

| R1 a (I ≥ 2σ) | 0.0573 |

| wR2 b (I ≥ 2σ) | 0.1500 |

| CCDC No. | 2,104,365 |

| Atoms | Distance | Atoms | Distance |

| Cl1-C16 | 1.7486 | Cl1B-C16B | 1.7566 |

| Cl2-C26 | 1.7396 | Cl2B-C26B | 1.7446 |

| S5-C10 | 1.7475 | S5B-C10B | 1.7685 |

| S5-C11 | 1.8265 | S5B-C11B | 1.8185 |

| S6-C20 | 1.8007 | S6B-C20B | 1.8247 |

| S6-C21 | 1.8406 | S6B-C21B | 1.8196 |

| O1-C3 | 1.4218 | O1B-C3B | 1.4399 |

| O1-C2 | 1.4409 | O1B-C2B | 1.4117 |

| O2-C7 | 1.2358 | O2B-C7B | 1.2247 |

| Atoms | Angle | Atoms | Angle |

| C10-S5-C11 | 93.42 | C10B-S5B-C11B | 93.12 |

| C20-S6-C21 | 90.33 | C21B-S6B-C20B | 93.33 |

| C3-O1-C2 | 110.25 | C2B-O1B-C3B | 109.35 |

| C5-N1-C4 | 112.35 | C5B-N1B-C4B | 110.85 |

| C5-N1-C1 | 112.95 | C1B-N1B-C5B | 112.04 |

| C4-N1-C1 | 106.95 | C1B-N1B-C4B | 108.55 |

| C7-N2-C6 | 119.66 | C7B-N2B-C6B | 122.95 |

| D-H...A | d(D-H) | d(H...A) | d(D...A) | <(DHA) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N2-H2...O1S | 0.90(9) | 2.09(9) | 2.875(8) | 146(7) |

| O2S-H2S...O1B | 0.97 | 1.9 | 2.843(8) | 164 |

| N5-H5...O2 | 0.78(8) | 1.98(9) | 2.725(7) | 160(10) |

| O1S-H1SA...O1 | 0.96 | 1.93 | 2.747(8) | 140 |

| O1S-H1SB...O5B | 0.92 | 2.03 | 2.909(7) | 159 |

| O2S-H2SA...S6B | 0.99 | 2.77 | 3.627(6) | 146 |

| O2S-H2SA...O5 | 0.99 | 2.41 | 2.910(7) | 111 |

| N5B-H5BA...O2B | 0.87(8) | 2.06(8) | 2.870(6) | 154(7) |

| N2B-H2BA...O2S | 0.96(9) | 1.90(9) | 2.845(8) | 166(7) |

| C8-H8A...O4 | 0.99 | 2.5 | 2.848(7) | 100 |

| C12-H12...O4 | 1.00 | 2.44 | 2.926(7) | 109 |

| C12B-H12B...O4B | 1.00 | 2.46 | 2.929(7) | 108 |

| C8B-H8BB...O4B | 0.99 | 2.49 | 2.856(7) | 102 |

| C14B-H14B...O5B | 0.95 | 2.28 | 3.143(8) | 152 |

| C18-H18...O5 | 0.95 | 2.35 | 3.226(7) | 154 |

| C19-H19...O5 | 1.00 | 2.43 | 3.006(7) | 116 |

| C21-H21B...O4 | 0.99 | 2.49 | 3.338(8) | 144 |

| C28B-H28B...O4B | 0.95 | 2.52 | 3.154(8) | 124 |

| Contact | Distance | Contact | Distance |

|---|---|---|---|

| H3BB…C16B | 2.675 | O4…H20D | 2.585 |

| H6BA…C7 | 2.678 | O3B…H21A | 2.464 |

| H1B…C23 | 2.769 | O5B…H1SB | 1.974 |

| H1SA…C2 | 2.382 | O4B…H4A | 2.542 |

| H15…C10 | 2.654 | O4B…H20A | 2.532 |

| H2S…C3B | 2.613 | O2…H5 | 1.765 |

| S5B…H21A | 2.858 | O3…H15 | 2.595 |

| Cl2B…C24 | 3.368 | O2B…H5BA | 1.941 |

| Cl2…C21B | 3.44 | O3B…H21A | 2.464 |

| S6…S5B | 3.542 | O2S…H2BA | 1.856 |

| H2SA…H2BA | 2.157 | O1B…H2S | 1.886 |

| H2B…H1SA | 1.989 | O1S…H2 | 1.995 |

| H20B…H5B | 2.157 | O5…H2SA | 2.408 |

| N2…H6BA | 2.683 | C26B…C17B | 3.353 |

| Bond b | Calc | Exp | Bond | Calc | Exp |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| R(1–47) | 1.760 | 1.755 | R(15–18) | 1.527 | 1.515 |

| R(2–65) | 1.757 | 1.744 | R(21–24) | 1.527 | 1.506 |

| R(3–38) | 1.784 | 1.769 | R(27–30) | 1.537 | 1.516 |

| R(3–39) | 1.849 | 1.819 | R(33–34) | 1.544 | 1.517 |

| R(4–54) | 1.855 | 1.824 | R(37–39) | 1.541 | 1.547 |

| R(4–57) | 1.861 | 1.819 | R(39–40) | 1.602 | 1.581 |

| R(5–18) | 1.421 | 1.410 | R(39–60) | 1.595 | 1.598 |

| R(5–21) | 1.421 | 1.439 | R(40–42) | 1.514 | 1.498 |

| R(6–33) | 1.223 | 1.224 | R(40–52) | 1.542 | 1.538 |

| R(7–38) | 1.208 | 1.217 | R(42–43) | 1.403 | 1.397 |

| R(8–37) | 1.216 | 1.212 | R(42–50) | 1.401 | 1.402 |

| R(9–61) | 1.219 | 1.225 | R(43–45) | 1.394 | 1.378 |

| R(10–15) | 1.468 | 1.466 | R(45–47) | 1.394 | 1.39 |

| R(10–24) | 1.466 | 1.472 | R(47–48) | 1.393 | 1.356 |

| R(10–27) | 1.460 | 1.465 | R(48–50) | 1.394 | 1.392 |

| R(11–30) | 1.458 | 1.448 | R(52–54) | 1.528 | 1.538 |

| R(11–33) | 1.359 | 1.349 | R(60–61) | 1.576 | 1.585 |

| R(12–34) | 1.448 | 1.462 | R(60–70) | 1.520 | 1.510 |

| R(12–37) | 1.382 | 1.361 | R(62–63) | 1.388 | 1.384 |

| R(12–38) | 1.397 | 1.377 | R(62–70) | 1.405 | 1.396 |

| R(13–52) | 1.460 | 1.448 | R(63–65) | 1.399 | 1.385 |

| R(13–57) | 1.448 | 1.415 | R(65–66) | 1.394 | 1.384 |

| R(13–60) | 1.449 | 1.435 | R(66–68) | 1.401 | 1.403 |

| R(14–61) | 1.374 | 1.35 | R(68–70) | 1.389 | 1.389 |

| Atom | NC | Atom | NC | Atom | NC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cl 1 | −0.0095 | H25 | 0.2085 | H49 | 0.2569 |

| Cl 2 | 0.0055 | H26 | 0.2373 | C50 | −0.2050 |

| S 3 | 0.3188 | C27 | −0.2699 | H51 | 0.2602 |

| S 4 | 0.1906 | H28 | 0.2281 | C52 | −0.0613 |

| O 5 | −0.5755 | H29 | 0.2178 | H53 | 0.2461 |

| O 6 | −0.6328 | C30 | −0.2743 | C54 | −0.5813 |

| O 7 | −0.5651 | H31 | 0.2423 | H55 | 0.2644 |

| O 8 | −0.5838 | H32 | 0.2559 | H56 | 0.2534 |

| O 9 | −0.6000 | C33 | 0.6919 | C57 | −0.3845 |

| N10 | −0.5241 | C34 | −0.3576 | H58 | 0.2554 |

| N11 | −0.6587 | H35 | 0.2708 | H59 | 0.2217 |

| N12 | −0.4929 | H36 | 0.2816 | C60 | 0.0656 |

| N13 | −0.5118 | C37 | 0.7294 | C61 | 0.6974 |

| N14 | −0.6236 | C38 | 0.5354 | C62 | 0.1889 |

| C15 | −0.3000 | C39 | −0.2399 | C63 | −0.2898 |

| H16 | 0.2387 | C40 | −0.2612 | H64 | 0.2620 |

| H17 | 0.2097 | H41 | 0.2837 | C65 | −0.0205 |

| C18 | −0.1199 | C42 | −0.0573 | C66 | −0.2726 |

| H19 | 0.2354 | C43 | −0.2169 | H67 | 0.2611 |

| H20 | 0.2029 | H44 | 0.2618 | C68 | −0.1894 |

| C21 | −0.1199 | C45 | −0.2447 | H69 | 0.2760 |

| H22 | 0.2026 | H46 | 0.2573 | C70 | −0.0911 |

| H23 | 0.2343 | C47 | −0.0391 | H71 | 0.4475 |

| C24 | −0.2965 | C48 | −0.2457 | H72 | 0.4196 |

| μ | η | Ω | N | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AY 3a | −3.31 | 3.23 | 1.69 | 4.20 |

| AY 3b | −3.71 | 3.23 | 2.14 | 3.79 |

| AY 3c | −3.26 | 3.27 | 1.62 | 4.23 |

| AY 3d | −3.34 | 3.29 | 1.70 | 4.13 |

| AY 6 | −3.11 | 3.25 | 1.48 | 4.39 |

| Ethylene 7 | −4.39 | 3.78 | 2.55 | 2.84 |

| Ethylene 4 | −4.24 | 3.58 | 2.51 | 3.09 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Barakat, A.; Haukka, M.; Soliman, S.M.; Ali, M.; Al-Majid, A.M.; El-Faham, A.; Domingo, L.R. Straightforward Regio- and Diastereoselective Synthesis, Molecular Structure, Intermolecular Interactions and Mechanistic Study of Spirooxindole-Engrafted Rhodanine Analogs. Molecules 2021, 26, 7276. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules26237276

Barakat A, Haukka M, Soliman SM, Ali M, Al-Majid AM, El-Faham A, Domingo LR. Straightforward Regio- and Diastereoselective Synthesis, Molecular Structure, Intermolecular Interactions and Mechanistic Study of Spirooxindole-Engrafted Rhodanine Analogs. Molecules. 2021; 26(23):7276. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules26237276

Chicago/Turabian StyleBarakat, Assem, Matti Haukka, Saied M. Soliman, M. Ali, Abdullah Mohammed Al-Majid, Ayman El-Faham, and Luis R. Domingo. 2021. "Straightforward Regio- and Diastereoselective Synthesis, Molecular Structure, Intermolecular Interactions and Mechanistic Study of Spirooxindole-Engrafted Rhodanine Analogs" Molecules 26, no. 23: 7276. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules26237276

APA StyleBarakat, A., Haukka, M., Soliman, S. M., Ali, M., Al-Majid, A. M., El-Faham, A., & Domingo, L. R. (2021). Straightforward Regio- and Diastereoselective Synthesis, Molecular Structure, Intermolecular Interactions and Mechanistic Study of Spirooxindole-Engrafted Rhodanine Analogs. Molecules, 26(23), 7276. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules26237276