Cannabinoids and Neurogenesis: The Promised Solution for Neurodegeneration?

Abstract

:1. Introduction

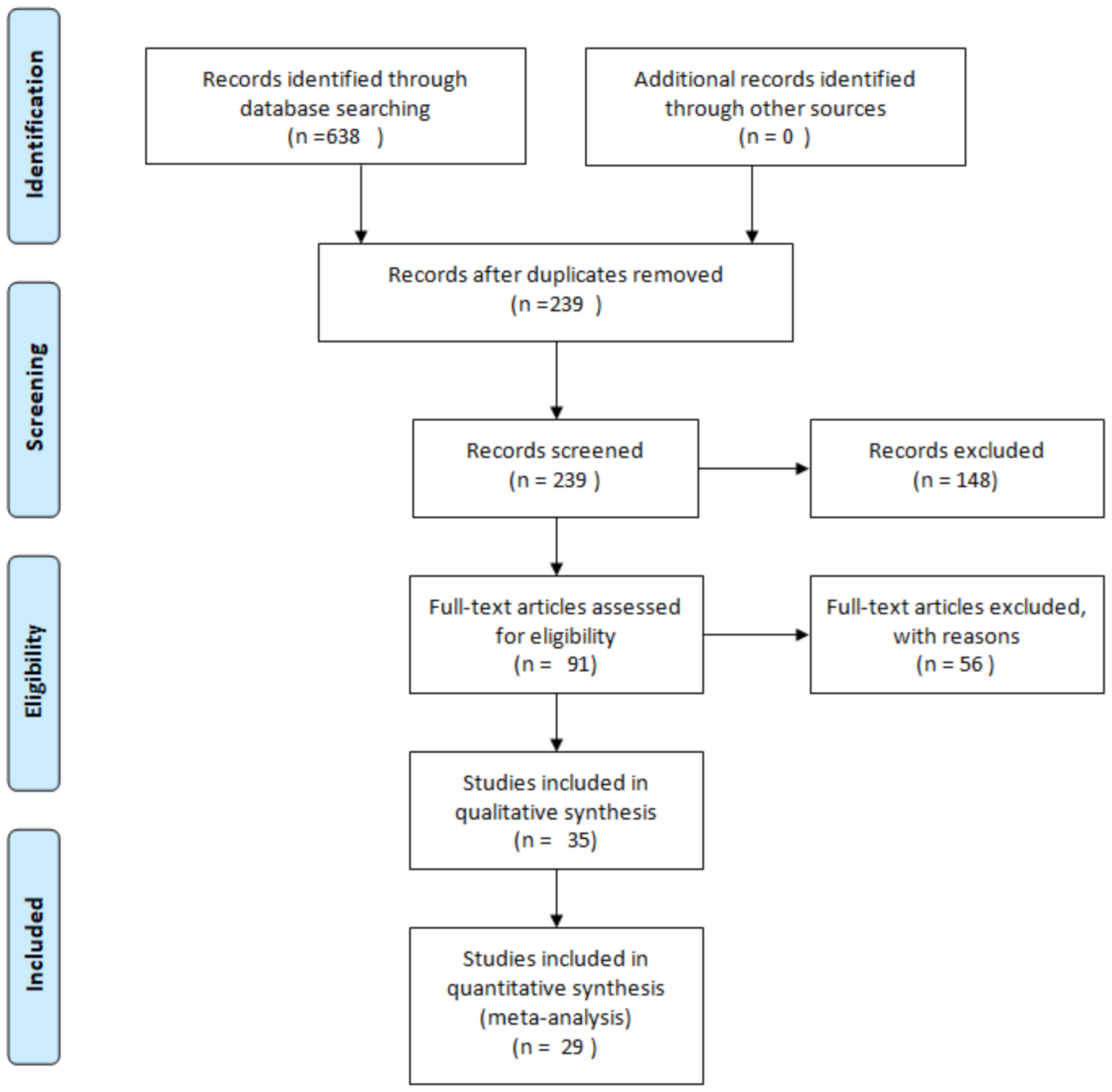

2. Methodology

3. Neurogenesis

4. Cannabinoid Receptors: CB1, CB2, TRPV1, GPR55 and PPARγ

4.1. Cannabinoid Receptor 1

4.2. Cannabinoid Receptor 2

4.3. Transient Receptor Potential Cation Channel Subfamily V Member 1

4.4. G Protein-Coupled Receptor 55

4.5. Peroxisome Proliferator-Activated Receptor Gamma

5. Cannabinoids: Endocannabinoids, Phytocannabinoids and Synthetic Cannabinoids

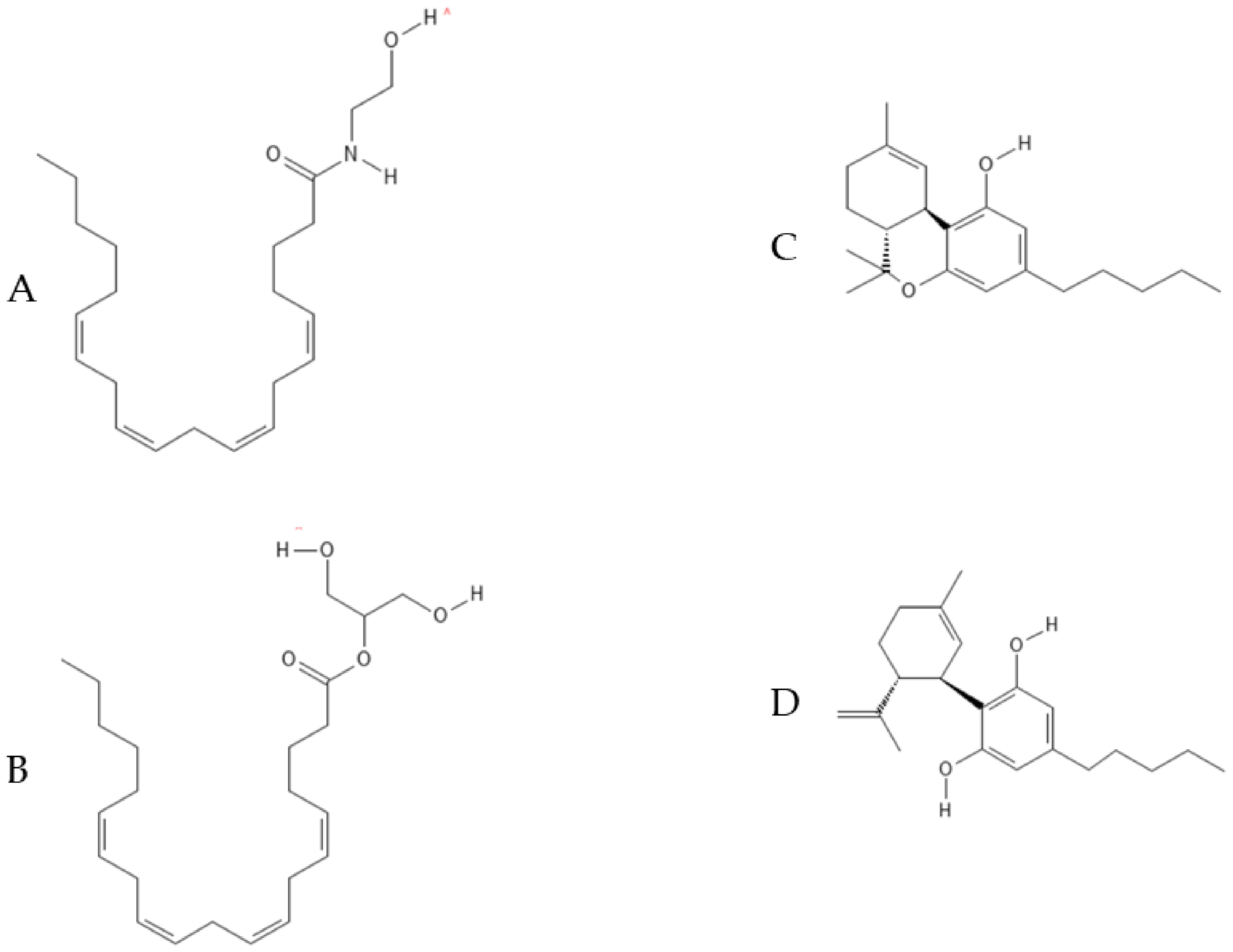

5.1. Endocannabinoids: AEA and 2-AG

5.2. Phytocannabinoids: THC, CBD and Effects on Neurogenesis

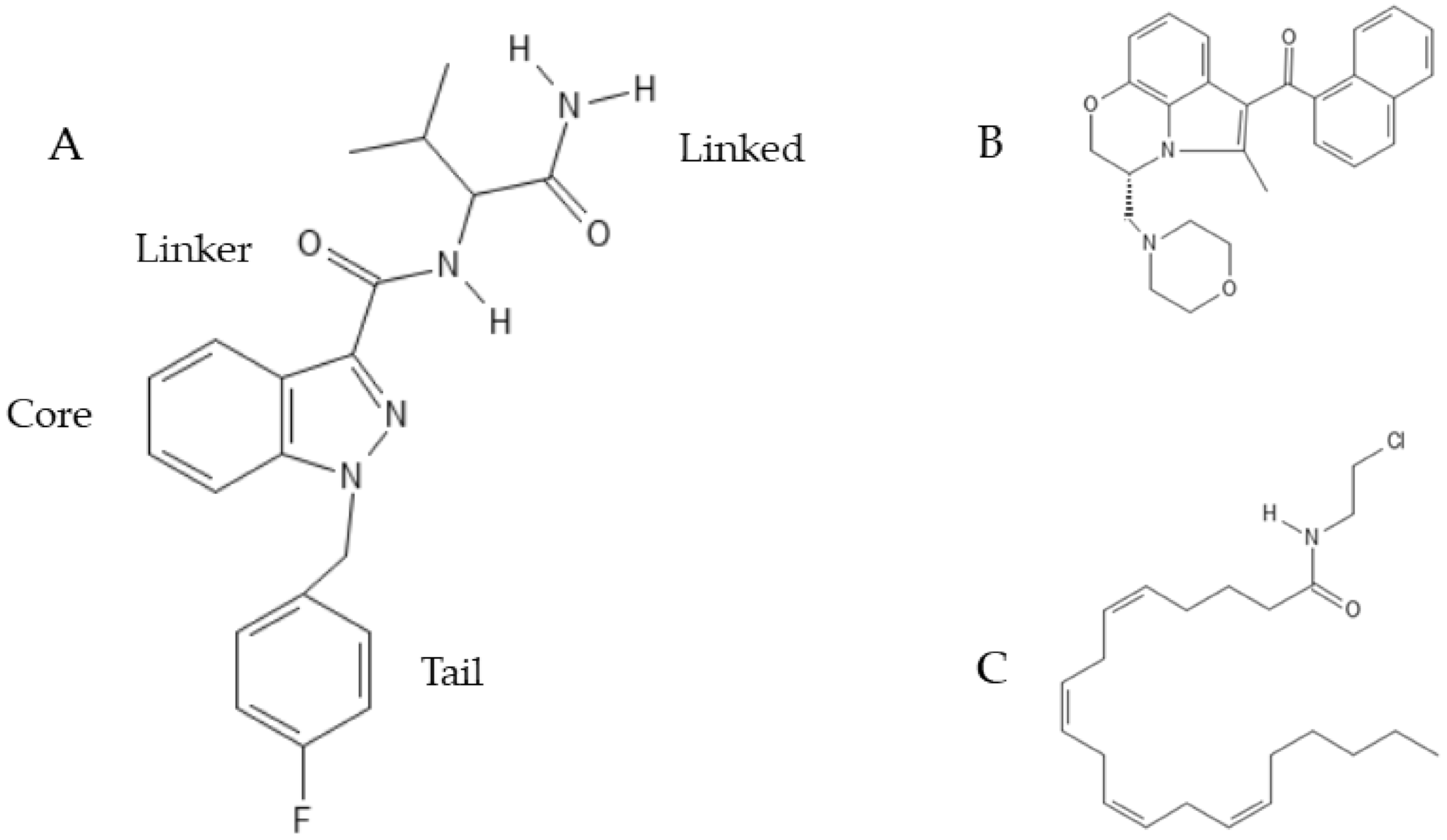

5.3. Synthetic Cannabinoids: Classification, Nomenclature and Effects on Neurogenesis

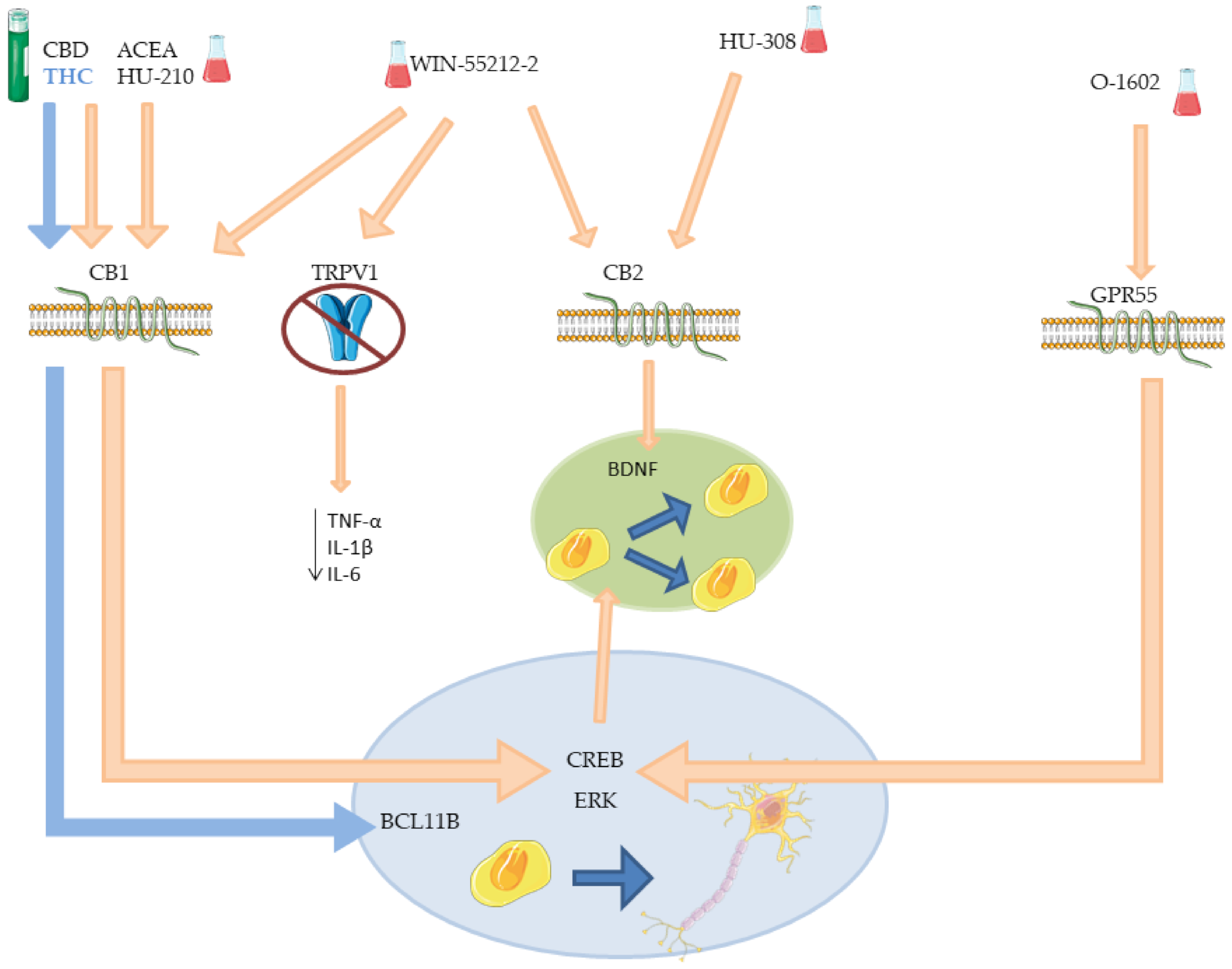

6. Psychoactive and Non-Psychoactive Cannabinoids Effects on Neurogenesis

6.1. Proof-of-Concept Experiments

6.2. Cannabinoids Effects on Neurogenesis in AD, PD, HD and HIV-Associated Dementia

6.3. Cannabinoids Effects on Neurogenesis in Stroke and Hypoxia/Ischemia Models

6.4. Cannabinoids Effects on Neurogenesis in Acute and Chronic Stressed Animals

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| Abbreviation | Full Text |

| 2-AG | 2-arachidonoyl glycerol |

| ABHD4 | Abhydrolase Domain Containing 4, N-Acyl Phospholipase B |

| AD | Alzheimer’s Disease |

| AEA | Arachidonyol ethanolammide or anandamide |

| ALS | Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis |

| ASCL1 | Achaete-scute homolog 1 |

| Aβ | Beta-amyloid |

| BCL11B | B-cell lymphoma/leukemia 11B |

| BDNF | Brain-derived neurotrophic factor |

| BdrU | Bromodeoxyuridine |

| CAM | Cell adhesion molecules |

| cAMP | Cyclic adenosine monophosphate |

| CB1 | Cannabinoid receptor 1 |

| CB2 | Cannabinoid Receptor 2 |

| CBD | Cannabidiol |

| CBDA | Cannabidiolic acid |

| CBG | Cannabigerol |

| CBGA | Cannabigerolic acid |

| CBN | Cannabinol |

| CDC42 | Cell Division Cycle 42 |

| CDKN1C | Cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor 1C |

| CR | Calretinin |

| CREB | cAMP response element-binding protein |

| DAGL | Ciacylglycerol lipase |

| Dcc | Transmembrane protein deleted in colorectal cancer |

| DCX | Doublecortin |

| DG | Dentate gyrus |

| EMCDDA | European Monitoring Center for Drugs and Drugs Addiction |

| ERK | Extracellular signal-regulated kinases |

| FAAH | Fatty acid amide hydrolase |

| FDA | Food and Drug Administration |

| FGFR | Fibroblast growth factor receptors |

| FST | Force swimming test |

| GABA | Gamma-aminobutyric acid |

| GDE1 | Glycerophosphodiesterase 1 |

| GFAP | Glial fibrillary acidic protein |

| GPP | Geranylpyrophosphate |

| GPR55 | G protein-coupled receptor 55 |

| GSK3β | glycogen synthase kinase 3 beta |

| hiPS | Human induced pluripotent stem |

| IL | Interleukin |

| IL1-RA | Interleukin-1 receptor antagonist |

| JNK | c-Jun N-terminal kinase |

| Ki-67 | Antigen Ki-67 |

| KROX-24 | Early growth response protein 1 |

| LTP | Long term potentiation |

| MAP-2 | Microtubule-associated protein 2 |

| MAPKs | Mitogen-activated protein kinases |

| MPTP | 1-methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridine |

| mTORC | Mechanistic target of rapamycin complex |

| NAE | N-acyl-ethanolamine |

| NAPE | N-acylphosphatidylethanolamine |

| NAPE-PDL | N-acylphosphatidylethanolamine phospholipase D |

| NAT | N-acyltransferase |

| NeuN | Hexaribonucleotide Binding Protein-3 |

| NeuroD1 | Neurogenic differentiation 1 |

| NF-kB | Transcription factors like nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells |

| NPCs | Neuronal progenitor cells |

| NSCs | Neural stem cells |

| p27Kip1 | Cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor 1B protein |

| Pals1 | Protein associated with Lin-7 |

| PD | Parkinson’s Disease |

| PI3K/AKT | Phosphoinositide 3-kinases/protein kinase B |

| PINK1 | PTEN-induced kinase 1 |

| PIP2 | Phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate |

| PLC | NAPE-phospholipase C |

| PLCβ | Phospholipase C-β |

| PPARγ | Peroxisome proliferator- activated receptor gamma |

| Prox1 | Prospero related homeobox gene |

| PSA-NCAM | Polysialylated-neural cell adhesion molecule |

| Rhoa | Ras homolog gene family members A |

| ROCK | Rho-associated protein kinase |

| SGK1 | Serum and glucocorticoid-regulated kinase 1 |

| SGZ | Subgranular zone |

| SOX2 | Sex determining region Y-box 2 |

| STAT3 | Signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 |

| SVZ | Subventricular zone of the lateral ventricle |

| THC | Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol |

| TLX | Nuclear receptor subfamily 2 group E member 1 |

| TNFα | Tumor necrosis factor alpha |

| TrkA | Tropomyosin receptor kinase A |

| TRPV1 | Transient receptor potential cation channel subfamily V member 1 |

| Tuj1 | β-tubulin isoform III |

| UNC5C | UNC-5 netrin receptor C |

| Δ1-THCA | Δ1-tetrahydrocannabinolic acid |

References

- Agrawal, M. Chapter 26—Molecular basis of chronic neurodegeneration. In Clinical Molecular Medicine; Kumar, D., Ed.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2020; pp. 447–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padda, I.S.; Parmar, M. Aducanumab. In StatPearls; StatPearls Publishing LLC.: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Radak, D.; Katsiki, N.; Resanovic, I.; Jovanovic, A.; Sudar-Milovanovic, E.; Zafirovic, S.; Mousad, S.A.; Isenovic, E.R. Apoptosis and Acute Brain Ischemia in Ischemic Stroke. Curr. Vasc. Pharmacol. 2017, 15, 115–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kalaria, R.N.; Akinyemi, R.; Ihara, M. Stroke injury, cognitive impairment and vascular dementia. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2016, 1862, 915–925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- De Chiara, G.; Marcocci, M.E.; Sgarbanti, R.; Civitelli, L.; Ripoli, C.; Piacentini, R.; Garaci, E.; Grassi, C.; Palamara, A.T. Infectious agents and neurodegeneration. Mol. Neurobiol. 2012, 46, 614–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Altman, J.; Das, G.D. Autoradiographic and histological evidence of postnatal hippocampal neurogenesis in rats. J. Comp. Neurol. 1965, 124, 319–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fox, S.H. Cannabinoids. In Encyclopedia of Movement Disorders; Kompoliti, K., Metman, L.V., Eds.; Academic Press: Oxford, UK, 2010; pp. 178–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crocq, M.-A. History of cannabis and the endocannabinoid system. Dialogues Clin. Neurosci 2020, 22, 223–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alves, P.; Amaral, C.; Teixeira, N.; Correia-da-Silva, G. Cannabis sativa: Much more beyond Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol. Pharmacol. Res. 2020, 157, 104822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramirez, C.L.; Fanovich, M.A.; Churio, M.S. Chapter 4—Cannabinoids: Extraction Methods, Analysis, and Physicochemical Characterization. In Studies in Natural Products Chemistry; Atta-ur-Rahman, Ed.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2019; Volume 61, pp. 143–173. [Google Scholar]

- Burstein, S. Cannabidiol (CBD) and its analogs: A review of their effects on inflammation. Bioorganic Med. Chem. 2015, 23, 1377–1385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berdyshev, E.V. Cannabinoid receptors and the regulation of immune response. Chem. Phys. Lipids 2000, 108, 169–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campos, A.C.; Fogaça, M.V.; Sonego, A.B.; Guimarães, F.S. Cannabidiol, neuroprotection and neuropsychiatric disorders. Pharm. Res. 2016, 112, 119–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- PubChem. National Library of Medicine (US), National Center for Biotechnology Information; 2004. PubChem Compound Summary for CID 5284592, Nabilone. Available online: https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/compound/Nabilone (accessed on 1 September 2021).

- PubChem. National Library of Medicine (US), National Center for Biotechnology Information; 2004. PubChem Compound Summary for CID 16078, Dronabinol. Available online: https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/compound/Dronabinol (accessed on 1 September 2021).

- European Medicine Agency Epidiolex. Available online: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/medicines/human/EPAR/epidyolex (accessed on 1 September 2021).

- Vermersch, P. Sativex(®) (tetrahydrocannabinol + cannabidiol), an endocannabinoid system modulator: Basic features and main clinical data. Expert Rev. Neurother. 2011, 11, 15–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moher, D.; Liberati, A.; Tetzlaff, J.; Altman, D.G. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009, 6, e1000097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ernst, A.; Frisén, J. Adult neurogenesis in humans- common and unique traits in mammals. PLoS Biol. 2015, 13, e1002045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ming, G.L.; Song, H. Adult neurogenesis in the mammalian central nervous system. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 2005, 28, 223–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kempermann, G.; Jessberger, S.; Steiner, B.; Kronenberg, G. Milestones of neuronal development in the adult hippocampus. Trends Neurosci. 2004, 27, 447–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niklison-Chirou, M.V.; Agostini, M.; Amelio, I.; Melino, G. Regulation of Adult Neurogenesis in Mammalian Brain. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 4869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matsuda, L.A.; Lolait, S.J.; Brownstein, M.J.; Young, A.C.; Bonner, T.I. Structure of a cannabinoid receptor and functional expression of the cloned cDNA. Nature 1990, 346, 561–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elphick, M.R.; Egertova, M. The neurobiology and evolution of cannabinoid signalling. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. London. Ser. B Biol. Sci. 2001, 356, 381–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abood, M.; Alexander, S.P.H.; Barth, F.; Bonner, T.I.; Bradshaw, H.; Cabral, G.; Casellas, P.; Cravatt, B.F.; Devane, W.A.; Marzo, V.D.; et al. Cannabinoid receptors (version 2019.4) in the IUPHAR/BPS Guide to Pharmacology Database. IUPHAR/BPS Guide Pharmacol. CITE 2019, 2019, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hua, T.; Vemuri, K.; Nikas, S.P.; Laprairie, R.B.; Wu, Y.; Qu, L.; Pu, M.; Korde, A.; Jiang, S.; Ho, J.-H.; et al. Crystal structures of agonist-bound human cannabinoid receptor CB(1). Nature 2017, 547, 468–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, Z.; Yin, J.; Chapman, K.; Grzemska, M.; Clark, L.; Wang, J.; Rosenbaum, D.M. High-resolution crystal structure of the human CB1 cannabinoid receptor. Nature 2016, 540, 602–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mátyás, F.; Yanovsky, Y.; MacKie, K.; Kelsch, W.; Misgeld, U.; Freund, T.F. Subcellular localization of type 1 cannabinoid receptors in the rat basal ganglia. Neuroscience 2006, 137, 337–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haspula, D.; Clark, M.A. Cannabinoid Receptors: An Update on Cell Signaling, Pathophysiological Roles and Therapeutic Opportunities in Neurological, Cardiovascular, and Inflammatory Diseases. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 7693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brailoiu, G.C.; Oprea, T.I.; Zhao, P.; Abood, M.E.; Brailoiu, E. Intracellular cannabinoid type 1 (CB1) receptors are activated by anandamide. J. Biol. Chem. 2011, 286, 29166–29174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Szabo, B.; Schlicker, E. Effects of cannabinoids on neurotransmission. In Cannabinoids; (Handbook of Experimental Pharmacology); Springer: Berlin/Heidleberg, Germany, 2005; pp. 327–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Topilko, P.; Levi, G.; Merlo, G.; Mantero, S.; Desmarquet, C.; Mancardi, G.; Charnay, P. Differential regulation of the zinc finger genes Krox-20 and Krox-24 (Egr-1) suggests antagonistic roles in Schwann cells. J. Neurosci. Res. 1997, 50, 702–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molina-Holgado, E.; Vela, J.M.; Arévalo-Martín, A.; Almazán, G.; Molina-Holgado, F.; Borrell, J.; Guaza, C. Cannabinoids promote oligodendrocyte progenitor survival: Involvement of cannabinoid receptors and phosphatidylinositol-3 kinase/Akt signaling. J. Neurosci. Off. J. Soc. Neurosci. 2002, 22, 9742–9753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laprairie, R.B.; Bagher, A.M.; Kelly, M.E.M.; Dupré, D.J.; Denovan-Wright, E.M. Type 1 cannabinoid receptor ligands display functional selectivity in a cell culture model of striatal medium spiny projection neurons. J. Biol. Chem. 2014, 289, 24845–24862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Navarrete, M.; Araque, A. Endocannabinoids mediate neuron-astrocyte communication. Neuron 2008, 57, 883–893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Aguado, T.; Palazuelos, J.; Monory, K.; Stella, N.; Cravatt, B.; Lutz, B.; Marsicano, G.; Kokaia, Z.; Guzmán, M.; Galve-Roperh, I. The endocannabinoid system promotes astroglial differentiation by acting on neural progenitor cells. J. Neurosci. Off. J. Soc. Neurosci. 2006, 26, 1551–1561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Munro, S.; Thomas, K.L.; Abu-Shaar, M. Molecular characterization of a peripheral receptor for cannabinoids. Nature 1993, 365, 61–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pertwee, R.G. Pharmacology of cannabinoid CB1 and CB2 receptors. Pharmacol. Ther. 1997, 74, 129–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jordan, C.J.; Xi, Z.X. Progress in brain cannabinoid CB(2) receptor research: From genes to behavior. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2019, 98, 208–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NCBI. CNR2 Cannabinoid Receptor 2 [Homo sapiens (Human)]. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/gene/1269#general-gene-info (accessed on 2 September 2021).

- Li, X.; Hua, T.; Vemuri, K.; Ho, J.H.; Wu, Y.; Wu, L.; Popov, P.; Benchama, O.; Zvonok, N.; Locke, K.; et al. Crystal Structure of the Human Cannabinoid Receptor CB2. Cell 2019, 176, 459–467 e413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Onaivi, E.S. Neuropsychobiological Evidence for the Functional Presence and Expression of Cannabinoid CB2 Receptors in the Brain. Neuropsychobiology 2006, 54, 231–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.-Y.; Gao, M.; Shen, H.; Bi, G.-H.; Yang, H.-J.; Liu, Q.-R.; Wu, J.; Gardner, E.L.; Bonci, A.; Xi, Z.-X. Expression of functional cannabinoid CB2 receptor in VTA dopamine neurons in rats. Addict. Biol. 2017, 22, 752–765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cottone, E.; Pomatto, V.; Rapelli, S.; Scandiffio, R.; Mackie, K.; Bovolin, P. Cannabinoid Receptor Modulation of Neurogenesis: ST14A Striatal Neural Progenitor Cells as a Simplified In Vitro Model. Molecules 2021, 26, 1448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palazuelos, J.; Ortega, Z.; Díaz-Alonso, J.; Guzmán, M.; Galve-Roperh, I. CB2 cannabinoid receptors promote neural progenitor cell proliferation via mTORC1 signaling. J. Biol. Chem. 2012, 287, 1198–1209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Cao, E.; Liao, M.; Cheng, Y.; Julius, D. TRPV1 structures in distinct conformations reveal activation mechanisms. Nature 2013, 504, 113–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Venkatachalam, K.; Montell, C. TRP channels. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2007, 76, 387–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Irving, A.; Abdulrazzaq, G.; Chan, S.L.F.; Penman, J.; Harvey, J.; Alexander, S.P.H. Cannabinoid Receptor-Related Orphan G Protein-Coupled Receptors. Adv. Pharmacol. 2017, 80, 223–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramírez-Barrantes, R.; Cordova, C.; Poblete, H.; Muñoz, P.; Marchant, I.; Wianny, F.; Olivero, P. Perspectives of TRPV1 Function on the Neurogenesis and Neural Plasticity. Neural Plast. 2016, 2016, 1568145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gibson, H.E.; Edwards, J.G.; Page, R.S.; Van Hook, M.J.; Kauer, J.A. TRPV1 channels mediate long-term depression at synapses on hippocampal interneurons. Neuron 2008, 57, 746–759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kauer, J.A.; Gibson, H.E. Hot flash: TRPV channels in the brain. Trends Neurosci. 2009, 32, 215–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stock, K.; Garthe, A.; de Almeida Sassi, F.; Glass, R.; Wolf, S.A.; Kettenmann, H. The capsaicin receptor TRPV1 as a novel modulator of neural precursor cell proliferation. Stem Cells 2014, 32, 3183–3195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sawzdargo, M.; Nguyen, T.; Lee, D.K.; Lynch, K.R.; Cheng, R.; Heng, H.H.Q.; George, S.R.; O’Dowd, B.F. Identification and cloning of three novel human G protein-coupled receptor genes GPR52, ΨGPR53 and GPR55: GPR55 is extensively expressed in human brain1Sequence data from this article have been deposited with the GenBank Data Library under Accession Nos. AF096784-AF096786, AF100789.1. Mol. Brain Res. 1999, 64, 193–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marichal-Cancino, B.A.; Fajardo-Valdez, A.; Ruiz-Contreras, A.E.; Mendez-Díaz, M.; Prospero-García, O. Advances in the Physiology of GPR55 in the Central Nervous System. Curr. Neuropharmacol. 2017, 15, 771–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Godlewski, G.; Offertáler, L.; Wagner, J.A.; Kunos, G. Receptors for acylethanolamides-GPR55 and GPR119. Prostaglandins Other Lipid Mediat. 2009, 89, 105–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Wu, C.-S.; Chen, H.; Sun, H.; Zhu, J.; Jew, C.P.; Wager-Miller, J.; Straiker, A.; Spencer, C.; Bradshaw, H.; Mackie, K.; et al. GPR55, a G-protein coupled receptor for lysophosphatidylinositol, plays a role in motor coordination. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e60314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Sylantyev, S.; Jensen, T.P.; Ross, R.A.; Rusakov, D.A. Cannabinoid- and lysophosphatidylinositol-sensitive receptor GPR55 boosts neurotransmitter release at central synapses. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2013, 110, 5193–5198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Vázquez-León, P.; Miranda-Páez, A.; Calvillo-Robledo, A.; Marichal-Cancino, B.A. Blockade of GPR55 in dorsal periaqueductal gray produces anxiety-like behaviors and evocates defensive aggressive responses in alcohol-pre-exposed rats. Neurosci. Lett. 2021, 764, 136218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shang, J.; Mosure, S.A.; Zheng, J.; Brust, R.; Bass, J.; Nichols, A.; Solt, L.A.; Griffin, P.R.; Kojetin, D.J. A molecular switch regulating transcriptional repression and activation of PPARγ. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Layrolle, P.; Payoux, P.; Chavanas, S. PPAR Gamma and Viral Infections of the Brain. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 8876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmadian, M.; Suh, J.M.; Hah, N.; Liddle, C.; Atkins, A.R.; Downes, M.; Evans, R.M. PPARγ signaling and metabolism: The good, the bad and the future. Nat. Med. 2013, 19, 557–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Villapol, S. Roles of Peroxisome Proliferator-Activated Receptor Gamma on Brain and Peripheral Inflammation. Cell. Mol. Neurobiol. 2018, 38, 121–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Braissant, O.; Wahli, W. Differential expression of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-alpha, -beta, and -gamma during rat embryonic development. Endocrinology 1998, 139, 2748–2754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moreno, S.; Farioli-Vecchioli, S.; Cerù, M.P. Immunolocalization of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors and retinoid X receptors in the adult rat CNS. Neuroscience 2004, 123, 131–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devane, W.A.; Hanus, L.; Breuer, A.; Pertwee, R.G.; Stevenson, L.A.; Griffin, G.; Gibson, D.; Mandelbaum, A.; Etinger, A.; Mechoulam, R. Isolation and structure of a brain constituent that binds to the cannabinoid receptor. Science 1992, 258, 1946–1949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cascio, M.G.; Marini, P. Biosynthesis and Fate of Endocannabinoids. Handb. Exp. Pharmacol. 2015, 231, 39–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Wang, L.; Harvey-White, J.; Huang, B.X.; Kim, H.-Y.; Luquet, S.; Palmiter, R.D.; Krystal, G.; Rai, R.; Mahadevan, A.; et al. Multiple pathways involved in the biosynthesis of anandamide. Neuropharmacology 2008, 54, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Lu, H.C.; Mackie, K. An Introduction to the Endogenous Cannabinoid System. Biol. Psychiatry 2016, 79, 516–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mechoulam, R.; Ben-Shabat, S.; Hanus, L.; Ligumsky, M.; Kaminski, N.E.; Schatz, A.R.; Gopher, A.; Almog, S.; Martin, B.R.; Compton, D.R.; et al. Identification of an endogenous 2-monoglyceride, present in canine gut, that binds to cannabinoid receptors. Biochem. Pharmacol. 1995, 50, 83–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murataeva, N.; Straiker, A.; Mackie, K. Parsing the players: 2-arachidonoylglycerol synthesis and degradation in the CNS. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2014, 171, 1379–1391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gaoni, Y.; Mechoulam, R. Isolation, Structure, and Partial Synthesis of an Active Constituent of Hashish. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1964, 86, 1646–1647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fellermeier, M.; Zenk, M.H. Prenylation of olivetolate by a hemp transferase yields cannabigerolic acid, the precursor of tetrahydrocannabinol. FEBS Lett. 1998, 427, 283–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Taura, F.; Sirikantaramas, S.; Shoyama, Y.; Yoshikai, K.; Shoyama, Y.; Morimoto, S. Cannabidiolic-acid synthase, the chemotype-determining enzyme in the fiber-type Cannabis sativa. FEBS Lett. 2007, 581, 2929–2934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- De Petrocellis, L.; Ligresti, A.; Moriello, A.S.; Allarà, M.; Bisogno, T.; Petrosino, S.; Stott, C.G.; Di Marzo, V. Effects of cannabinoids and cannabinoid-enriched Cannabis extracts on TRP channels and endocannabinoid metabolic enzymes. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2011, 163, 1479–1494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Castaneto, M.S.; Gorelick, D.A.; Desrosiers, N.A.; Hartman, R.L.; Pirard, S.; Huestis, M.A. Synthetic cannabinoids: Epidemiology, pharmacodynamics, and clinical implications. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2014, 144, 12–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Potts, A.J.; Cano, C.; Thomas, S.H.L.; Hill, S.L. Synthetic cannabinoid receptor agonists: Classification and nomenclature. Clin. Toxicol. 2020, 58, 82–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- PubChem. National Library of Medicine (US), National Center for Biotechnology Information; 2004. PubChem Compound Summary for CID 5311501. Available online: https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/compound/win-55212-2 (accessed on 1 September 2021).

- Mechoulam, R.; Lander, N.; University, A.; Zahalka, J. Synthesis of the individual, pharmacologically distinct, enantiomers of a tetrahydrocannabinol derivative. Tetrahedron: Asymmetry 1990, 1, 315–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiley, J.L.; Marusich, J.A.; Huffman, J.W. Moving around the molecule: Relationship between chemical structure and in vivo activity of synthetic cannabinoids. Life Sci. 2014, 97, 55–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- The European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction. Synthetic Cannabinoids in Europe; EMCDDA: Lisbon, Portugal, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Pike, E.; Grafinger, K.E.; Cannaert, A.; Ametovski, A.; Luo, J.L.; Sparkes, E.; Cairns, E.A.; Ellison, R.; Gerona, R.; Stove, C.P.; et al. Systematic evaluation of a panel of 30 synthetic cannabinoid receptor agonists structurally related to MMB-4en-PICA, MDMB-4en-PINACA, ADB-4en-PINACA, and MMB-4CN-BUTINACA using a combination of binding and different CB(1) receptor activation assays: Part I-Synthesis, analytical characterization, and binding affinity for human CB(1) receptors. Drug Test. Anal. 2021, 13, 1383–1401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnett-Norris, J.; Hurst, D.P.; Buehner, K.; Ballesteros, J.A.; Guarnieri, F.; Reggio, P.H. Agonist alkyl tail interaction with cannabinoid CB1 receptor V6.43/I6.46 groove induces a helix 6 active conformation. Int. J. Quantum Chem. 2002, 88, 76–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diao, X.; Huestis, M.A. New Synthetic Cannabinoids Metabolism and Strategies to Best Identify Optimal Marker Metabolites. Front. Chem. 2019, 7, 109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodrigues, R.S.; Ribeiro, F.F.; Ferreira, F.; Vaz, S.H.; Sebastião, A.M.; Xapelli, S. Interaction between Cannabinoid Type 1 and Type 2 Receptors in the Modulation of Subventricular Zone and Dentate Gyrus Neurogenesis. Front. Pharmacol. 2017, 8, 516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zimmermann, T.; Maroso, M.; Beer, A.; Baddenhausen, S.; Ludewig, S.; Fan, W.; Vennin, C.; Loch, S.; Berninger, B.; Hofmann, C.; et al. Neural stem cell lineage-specific cannabinoid type-1 receptor regulates neurogenesis and plasticity in the adult mouse hippocampus. Cereb Cortex 2018, 28, 4454–4471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mensching, L.; Djogo, N.; Keller, C.; Rading, S.; Karsak, M. Stable Adult Hippocampal Neurogenesis in Cannabinoid Receptor CB2 Deficient Mice. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 3759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Ferreira, F.F.; Ribeiro, F.F.; Rodrigues, R.S.; Sebastião, A.M.; Xapelli, S. Brain-Derived Neurotrophic Factor (BDNF) Role in Cannabinoid-Mediated Neurogenesis. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 2018, 12, 441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Nakagawa, S.; Kim, J.E.; Lee, R.; Malberg, J.E.; Chen, J.; Steffen, C.; Zhang, Y.J.; Nestler, E.J.; Duman, R.S. Regulation of neurogenesis in adult mouse hippocampus by cAMP and the cAMP response element-binding protein. J. Neurosci. Off. J. Soc. Neurosci. 2002, 22, 3673–3682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giachino, C.; De Marchis, S.; Giampietro, C.; Parlato, R.; Perroteau, I.; Schütz, G.; Fasolo, A.; Peretto, P. cAMP response element-binding protein regulates differentiation and survival of newborn neurons in the olfactory bulb. J. Neurosci. Off. J. Soc. Neurosci. 2005, 25, 10105–10118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Paraíso-Luna, J.; Aguareles, J.; Martín, R.; Ayo-Martín, A.C.; Simón-Sánchez, S.; García-Rincón, D.; Costas-Insua, C.; García-Taboada, E.; de Salas-Quiroga, A.; Díaz-Alonso, J.; et al. Endocannabinoid signalling in stem cells and cerebral organoids drives differentiation to deep layer projection neurons via CB(1) receptors. Development 2020, 147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simon, R.; Brylka, H.; Schwegler, H.; Venkataramanappa, S.; Andratschke, J.; Wiegreffe, C.; Liu, P.; Fuchs, E.; Jenkins, N.A.; Copeland, N.G.; et al. A dual function of Bcl11b/Ctip2 in hippocampal neurogenesis. EMBO J. 2012, 31, 2922–2936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Suliman, N.A.; Taib, C.N.M.; Moklas, M.A.M.; Basir, R. Delta-9-Tetrahydrocannabinol (∆(9)-THC) Induce Neurogenesis and Improve Cognitive Performances of Male Sprague Dawley Rats. Neurotox Res. 2018, 33, 402–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Schiavon, A.P.; Bonato, J.M.; Milani, H.; Guimarães, F.S.; Weffort de Oliveira, R.M. Influence of single and repeated cannabidiol administration on emotional behavior and markers of cell proliferation and neurogenesis in non-stressed mice. Prog. Neuro-Psychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry 2016, 64, 27–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolf, S.A.; Bick-Sander, A.; Fabel, K.; Leal-Galicia, P.; Tauber, S.; Ramirez-Rodriguez, G.; Müller, A.; Melnik, A.; Waltinger, T.P.; Ullrich, O.; et al. Cannabinoid receptor CB1 mediates baseline and activity-induced survival of new neurons in adult hippocampal neurogenesis. Cell Commun. Signal. CCS 2010, 8, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Jiang, W.; Zhang, Y.; Xiao, L.; Van Cleemput, J.; Ji, S.P.; Bai, G.; Zhang, X. Cannabinoids promote embryonic and adult hippocampus neurogenesis and produce anxiolytic- and antidepressant-like effects. J. Clin. Investig. 2005, 115, 3104–3116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Andres-Mach, M.; Haratym-Maj, A.; Zagaja, M.; Rola, R.; Maj, M.; Chrościńska-Krawczyk, M.; Luszczki, J.J. ACEA (a highly selective cannabinoid CB1 receptor agonist) stimulates hippocampal neurogenesis in mice treated with antiepileptic drugs. Brain Res. 2015, 1624, 86–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hill, J.D.; Zuluaga-Ramirez, V.; Gajghate, S.; Winfield, M.; Persidsky, Y. Activation of GPR55 increases neural stem cell proliferation and promotes early adult hippocampal neurogenesis. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2018, 175, 3407–3421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Marchalant, Y.; Brothers, H.M.; Norman, G.J.; Karelina, K.; DeVries, A.C.; Wenk, G.L. Cannabinoids attenuate the effects of aging upon neuroinflammation and neurogenesis. Neurobiol. Dis. 2009, 34, 300–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, J.D.; Zuluaga-Ramirez, V.; Gajghate, S.; Winfield, M.; Sriram, U.; Rom, S.; Persidsky, Y. Activation of GPR55 induces neuroprotection of hippocampal neurogenesis and immune responses of neural stem cells following chronic, systemic inflammation. Brain Behav. Immun. 2019, 76, 165–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weller, J.; Budson, A. Current understanding of Alzheimer’s disease diagnosis and treatment. F1000Research 2018, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Antony, P.M.; Diederich, N.J.; Krüger, R.; Balling, R. The hallmarks of Parkinson’s disease. FEBS J. 2013, 280, 5981–5993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Rüb, U.; Seidel, K.; Heinsen, H.; Vonsattel, J.P.; den Dunnen, W.F.; Korf, H.W. Huntington’s disease (HD): The neuropathology of a multisystem neurodegenerative disorder of the human brain. Brain Pathol. 2016, 26, 726–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, D.; Low, J.K.; Logge, W.; Garner, B.; Karl, T. Chronic cannabidiol treatment improves social and object recognition in double transgenic APPswe/PS1∆E9 mice. Psychopharmacology 2014, 231, 3009–3017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Zheng, P.; Xie, Y.; Chen, X.; Solowij, N.; Green, K.; Chew, Y.L.; Huang, X.F. Cannabidiol regulates CB1-pSTAT3 signaling for neurite outgrowth, prolongs lifespan, and improves health span in Caenorhabditis elegans of Aβ pathology models. FASEB J. Off. Publ. Fed. Am. Soc. Exp. Biol. 2021, 35, e21537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, N.A.; Martins, N.M.; Sisti, F.M.; Fernandes, L.S.; Ferreira, R.S.; Queiroz, R.H.; Santos, A.C. The neuroprotection of cannabidiol against MPP⁺-induced toxicity in PC12 cells involves trkA receptors, upregulation of axonal and synaptic proteins, neuritogenesis, and might be relevant to Parkinson’s disease. Toxicol. Vitr. Int. J. Publ. Assoc. BIBRA 2015, 30, 231–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Esposito, G.; Scuderi, C.; Valenza, M.; Togna, G.I.; Latina, V.; De Filippis, D.; Cipriano, M.; Carratù, M.R.; Iuvone, T.; Steardo, L. Cannabidiol reduces Aβ-induced neuroinflammation and promotes hippocampal neurogenesis through PPARγ involvement. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e28668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morales-Garcia, J.A.; Luna-Medina, R.; Alfaro-Cervello, C.; Cortes-Canteli, M.; Santos, A.; Garcia-Verdugo, J.M.; Perez-Castillo, A. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ ligands regulate neural stem cell proliferation and differentiation in vitro and in vivo. Glia 2011, 59, 293–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Aguareles, J.; Paraíso-Luna, J.; Palomares, B.; Bajo-Grañeras, R.; Navarrete, C.; Ruiz-Calvo, A.; García-Rincón, D.; García-Taboada, E.; Guzmán, M.; Muñoz, E.; et al. Oral administration of the cannabigerol derivative VCE-003.2 promotes subventricular zone neurogenesis and protects against mutant huntingtin-induced neurodegeneration. Transl Neurodegener 2019, 8, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taheri, M.; Salamian, A.; Ghaedi, K.; Peymani, M.; Izadi, T.; Nejati, A.S.; Atefi, A.; Nematollahi, M.; Ahmadi Ghahrizjani, F.; Esmaeili, M.; et al. A ground state of PPARγ activity and expression is required for appropriate neural differentiation of hESCs. Pharmacol. Rep. PR 2015, 67, 1103–1114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díaz-Alonso, J.; Paraíso-Luna, J.; Navarrete, C.; Del Río, C.; Cantarero, I.; Palomares, B.; Aguareles, J.; Fernández-Ruiz, J.; Bellido, M.L.; Pollastro, F.; et al. VCE-003.2, a novel cannabigerol derivative, enhances neuronal progenitor cell survival and alleviates symptomatology in murine models of Huntington’s disease. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 29789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Shi, J.; Cai, Q.; Zhang, J.; He, X.; Liu, Y.; Zhu, R.; Jin, L. AM1241 alleviates MPTP-induced Parkinson’s disease and promotes the regeneration of DA neurons in PD mice. Oncotarget 2017, 8, 67837–67850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gugliandolo, A.; Silvestro, S.; Chiricosta, L.; Pollastro, F.; Bramanti, P.; Mazzon, E. The Transcriptomic Analysis of NSC-34 Motor Neuron-Like Cells Reveals That Cannabigerol Influences Synaptic Pathways: A Comparative Study with Cannabidiol. Life 2020, 10, 227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avraham, H.K.; Jiang, S.; Fu, Y.; Rockenstein, E.; Makriyannis, A.; Zvonok, A.; Masliah, E.; Avraham, S. The cannabinoid CB₂ receptor agonist AM1241 enhances neurogenesis in GFAP/Gp120 transgenic mice displaying deficits in neurogenesis. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2014, 171, 468–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Goncalves, M.B.; Suetterlin, P.; Yip, P.; Molina-Holgado, F.; Walker, D.J.; Oudin, M.J.; Zentar, M.P.; Pollard, S.; Yáñez-Muñoz, R.J.; Williams, G.; et al. A diacylglycerol lipase-CB2 cannabinoid pathway regulates adult subventricular zone neurogenesis in an age-dependent manner. Mol. Cell. Neurosci. 2008, 38, 526–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oudin, M.J.; Hobbs, C.; Doherty, P. DAGL-dependent endocannabinoid signalling: Roles in axonal pathfinding, synaptic plasticity and adult neurogenesis. Eur. J. Neurosci. 2011, 34, 1634–1646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh-Roy, A.; Wu, Z.; Goncharov, A.; Jin, Y.; Chisholm, A.D. Calcium and cyclic AMP promote axonal regeneration in Caenorhabditis elegans and require DLK-1 kinase. J. Neurosci. Off. J. Soc. Neurosci. 2010, 30, 3175–3183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Mori, M.A.; Meyer, E.; Soares, L.M.; Milani, H.; Guimarães, F.S.; de Oliveira, R.M.W. Cannabidiol reduces neuroinflammation and promotes neuroplasticity and functional recovery after brain ischemia. Prog. Neuro-Psychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry 2017, 75, 94–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, J.; Fang, Y.Q.; Ren, H.; Chen, T.; Guo, J.J.; Yan, J.; Song, S.; Zhang, L.Y.; Liao, H. WIN55, 212-2 protects oligodendrocyte precursor cells in stroke penumbra following permanent focal cerebral ischemia in rats. Acta Pharmacol. Sin. 2013, 34, 119–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Sun, J.; Fang, Y.; Chen, T.; Guo, J.; Yan, J.; Song, S.; Zhang, L.; Liao, H. WIN55, 212-2 promotes differentiation of oligodendrocyte precursor cells and improve remyelination through regulation of the phosphorylation level of the ERK 1/2 via cannabinoid receptor 1 after stroke-induced demyelination. Brain Res. 2013, 1491, 225–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomez, O.; Arevalo-Martin, A.; Garcia-Ovejero, D.; Ortega-Gutierrez, S.; Cisneros, J.A.; Almazan, G.; Sánchez-Rodriguez, M.A.; Molina-Holgado, F.; Molina-Holgado, E. The constitutive production of the endocannabinoid 2-arachidonoylglycerol participates in oligodendrocyte differentiation. Glia 2010, 58, 1913–1927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-López, D.; Pradillo, J.M.; García-Yébenes, I.; Martínez-Orgado, J.A.; Moro, M.A.; Lizasoain, I. The cannabinoid WIN55212-2 promotes neural repair after neonatal hypoxia-ischemia. Stroke 2010, 41, 2956–2964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bravo-Ferrer, I.; Cuartero, M.I.; Zarruk, J.G.; Pradillo, J.M.; Hurtado, O.; Romera, V.G.; Díaz-Alonso, J.; García-Segura, J.M.; Guzmán, M.; Lizasoain, I.; et al. Cannabinoid Type-2 Receptor Drives Neurogenesis and Improves Functional Outcome After Stroke. Stroke 2017, 48, 204–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oudin, M.J.; Gajendra, S.; Williams, G.; Hobbs, C.; Lalli, G.; Doherty, P. Endocannabinoids regulate the migration of subventricular zone-derived neuroblasts in the postnatal brain. J. Neurosci. Off. J. Soc. Neurosci. 2011, 31, 4000–4011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Campos, A.C.; Ortega, Z.; Palazuelos, J.; Fogaça, M.V.; Aguiar, D.C.; Díaz-Alonso, J.; Ortega-Gutiérrez, S.; Vázquez-Villa, H.; Moreira, F.A.; Guzmán, M.; et al. The anxiolytic effect of cannabidiol on chronically stressed mice depends on hippocampal neurogenesis: Involvement of the endocannabinoid system. Int. J. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2013, 16, 1407–1419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Fogaça, M.V.; Campos, A.C.; Coelho, L.D.; Duman, R.S.; Guimarães, F.S. The anxiolytic effects of cannabidiol in chronically stressed mice are mediated by the endocannabinoid system: Role of neurogenesis and dendritic remodeling. Neuropharmacology 2018, 135, 22–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, M.N.; Kambo, J.S.; Sun, J.C.; Gorzalka, B.B.; Galea, L.A. Endocannabinoids modulate stress-induced suppression of hippocampal cell proliferation and activation of defensive behaviours. Eur. J. Neurosci. 2006, 24, 1845–1849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rusznák, K.; Csekő, K.; Varga, Z.; Csabai, D.; Bóna, Á.; Mayer, M.; Kozma, Z.; Helyes, Z.; Czéh, B. Long-Term Stress and Concomitant Marijuana Smoke Exposure Affect Physiology, Behavior and Adult Hippocampal Neurogenesis. Front. Pharmacol. 2018, 9, 786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Name | Receptor | Action (Agonist/Antagonist) |

|---|---|---|

| ACEA | CB1 | Selective agonist |

| AM-1241 | CB2 | Selective agonist |

| HU-210 | CB1 or CB2 | Non-selective agonist |

| HU-308 | CB2 | Selective agonist |

| JWH-133 | CB2 | Selective agonist |

| O-1602 | GPR55 | Agonist |

| VCE-003.2 | PPARγ | Agonist |

| WIN-55212-2 | CB1 or CB2 TRPV1 | Non-selective agonist Antagonist |

| AM-404 | CB1 and TRPV1 | Agonist |

| Compound | Receptor(s) | Effects | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| ACEA | CB1 | Increased proliferation in SVZ. Increased neuronal differentiation. | [86,87,96] |

| HU-308 | CB2 | Increased proliferation in SVZ and DG. Increased neuronal differentiation. | [86,87] |

| WIN-55212-2 | CB1 and CB2 TRPV1 | Increased proliferation in SVZ and DG. Increased neuronal differentiation. Decreased microglia activation. Decreased microglia activation in DG. | [86,87,98] |

| THC | CB1 | Neuronal differentiation in deep layer. Reduce neurons in upper layer. Altered expression of neurodevelopmental and synaptic function genes. Increased neurogenesis in hippocampus. Increased/decreased cognitive performance †. Worsening/ameliorate locomotion †. | [90,92,94] |

| CBD | CB1 | Increased cell proliferation (low dose). Increased neurogenesis (low dose). Reduce anxiety behaviors. Reduced cell proliferation (high dose). Reduce neurogenesis (high dose). | [93,94] |

| HU-210 | CB1 | Induced proliferation of embryonic NSCs and NPCs. Increased hippocampal neurons number. Anxiolytic and antidepressant effects. | [95] |

| O-1602 | GPR55 | Increased differentiated neurons number. Increase immature neuron number. Increased proliferation in hNSCs. Increased neuronal differentiation. | [97,99] |

| Compound | Receptor(s) | Effects | References |

|---|---|---|---|

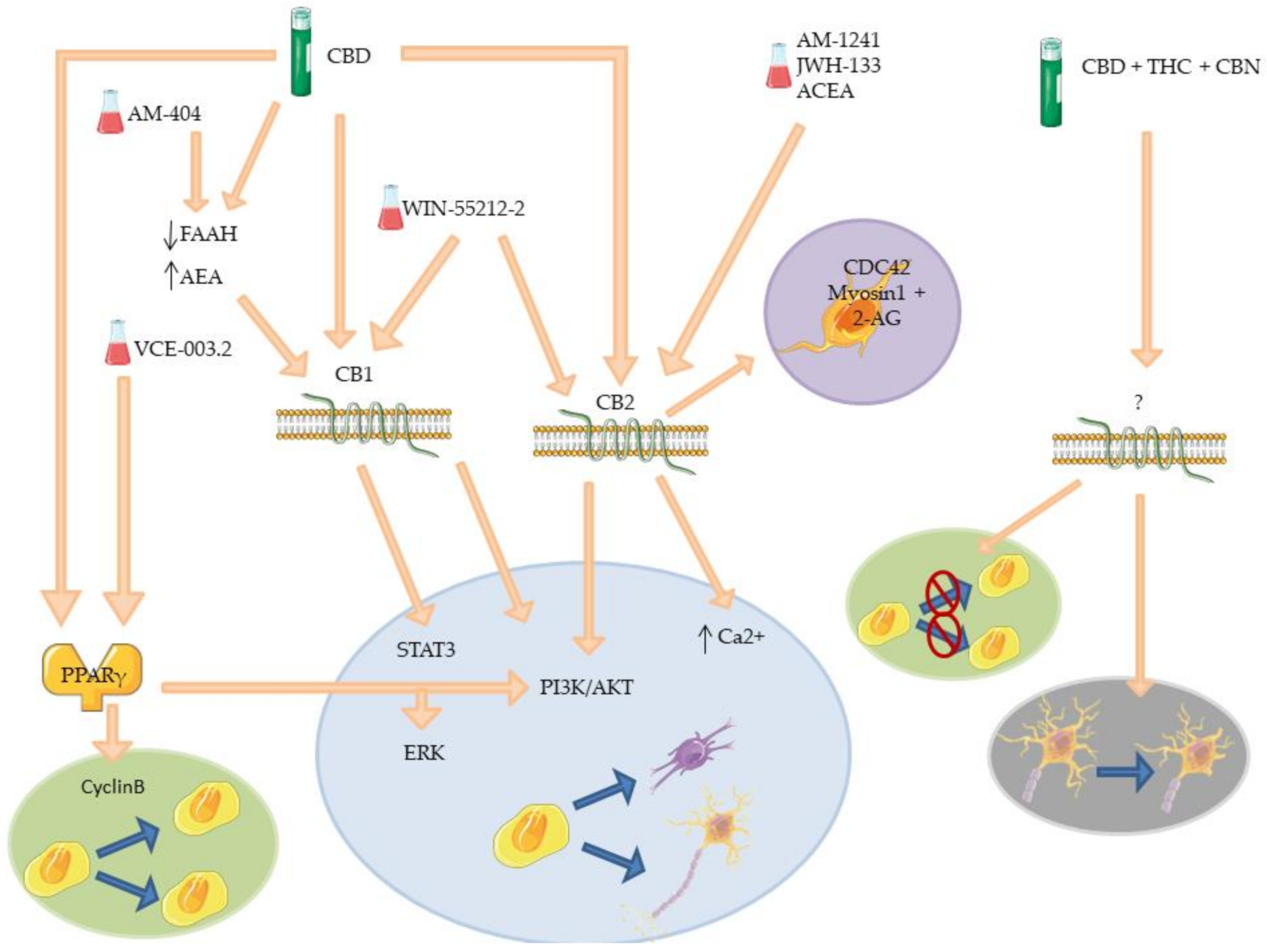

| CBD | CB1, CB2 and PPARγ | Decreased level of FAAH. Promotion neurite outgrowth. Synapsis formation and protection. Increased neurogenesis. Increase NSCs proliferation. Inhibit NSCs differentiation. Anxiolytic effects. Anti-inflammatory effects. | [103,104,105,106,107,117,124,125] |

| WIN-55212-2 | CB1 and CB2 | Re-myelinization. Increased oligodendrocytes progenitors proliferation, survival and differentiation. Increased neuroblast number. | [118,119,121] |

| ACEA | CB2 | Prevention of Gp120-induced hNPCs reduction. | [113] |

| AM-1241 | CB2 | Dopaminergic neurons regeneration. Promotion of NSCs differentiation. Anti-inflammatory effects. | [111,113] |

| JWH-133 | CB2 | Promotion of neuroblast migration. Promotion of NPCs migration. | [122] |

| VCE-003.2 | PPARγ | Promotion of NSCs differentiation. Promotion of NSCs proliferation. | [108,110] |

| AM-404 | CB1 and TRPV1 | Prevention of block of hippocampal cell proliferation. Prevention of defensive behavior. | [126] |

| CBD+THC+CBN | / | Reduction of immature neurons number in DG. Increased mobility of immature neurons in DG. Dendritic morphology alteration. | [127] |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Valeri, A.; Mazzon, E. Cannabinoids and Neurogenesis: The Promised Solution for Neurodegeneration? Molecules 2021, 26, 6313. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules26206313

Valeri A, Mazzon E. Cannabinoids and Neurogenesis: The Promised Solution for Neurodegeneration? Molecules. 2021; 26(20):6313. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules26206313

Chicago/Turabian StyleValeri, Andrea, and Emanuela Mazzon. 2021. "Cannabinoids and Neurogenesis: The Promised Solution for Neurodegeneration?" Molecules 26, no. 20: 6313. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules26206313

APA StyleValeri, A., & Mazzon, E. (2021). Cannabinoids and Neurogenesis: The Promised Solution for Neurodegeneration? Molecules, 26(20), 6313. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules26206313