Neuroprotective Effects and Mechanisms of Procyanidins In Vitro and In Vivo

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

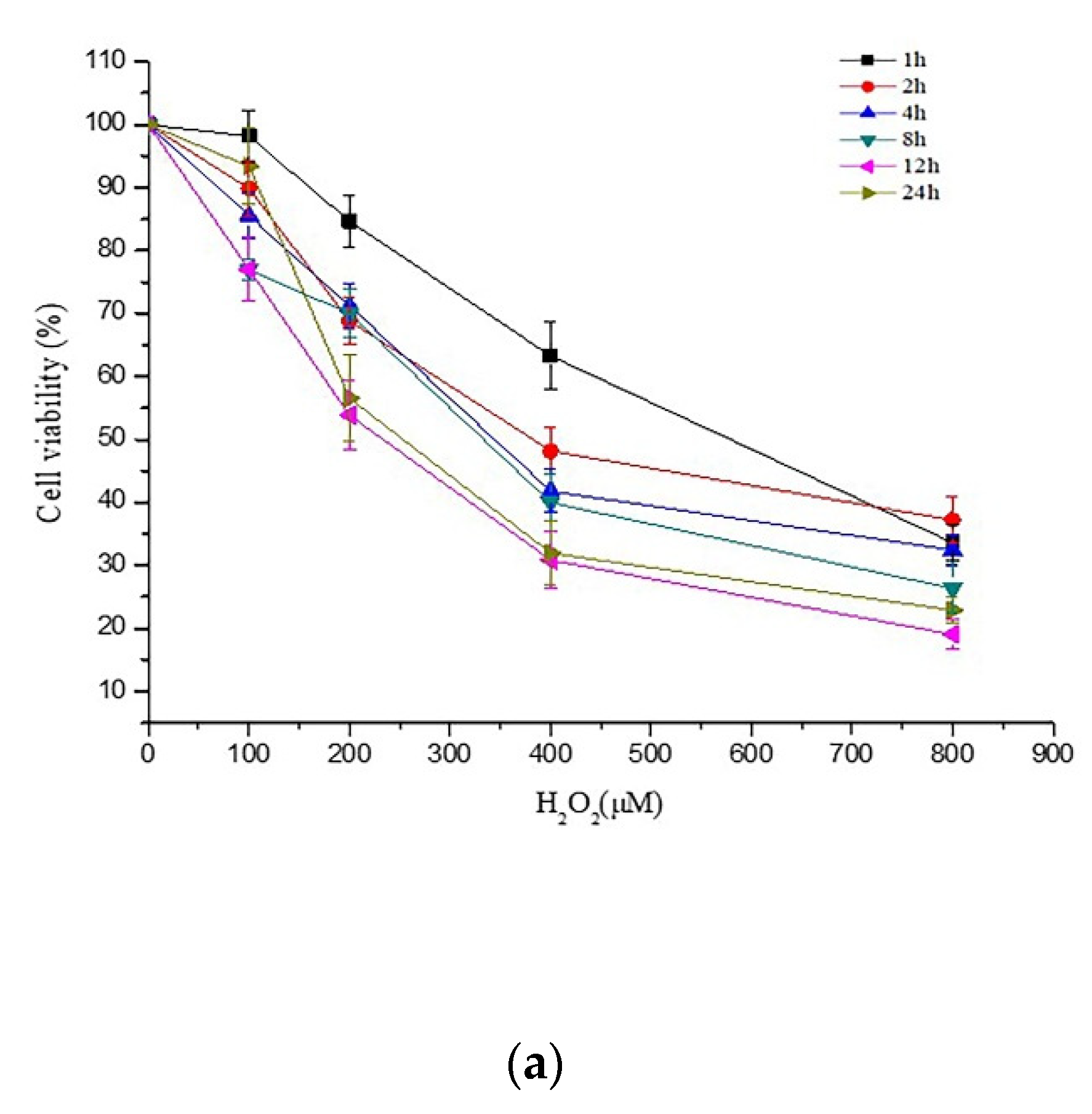

2.1. Effects of PCs on H2O2-Treated Damage of PC12 Cells

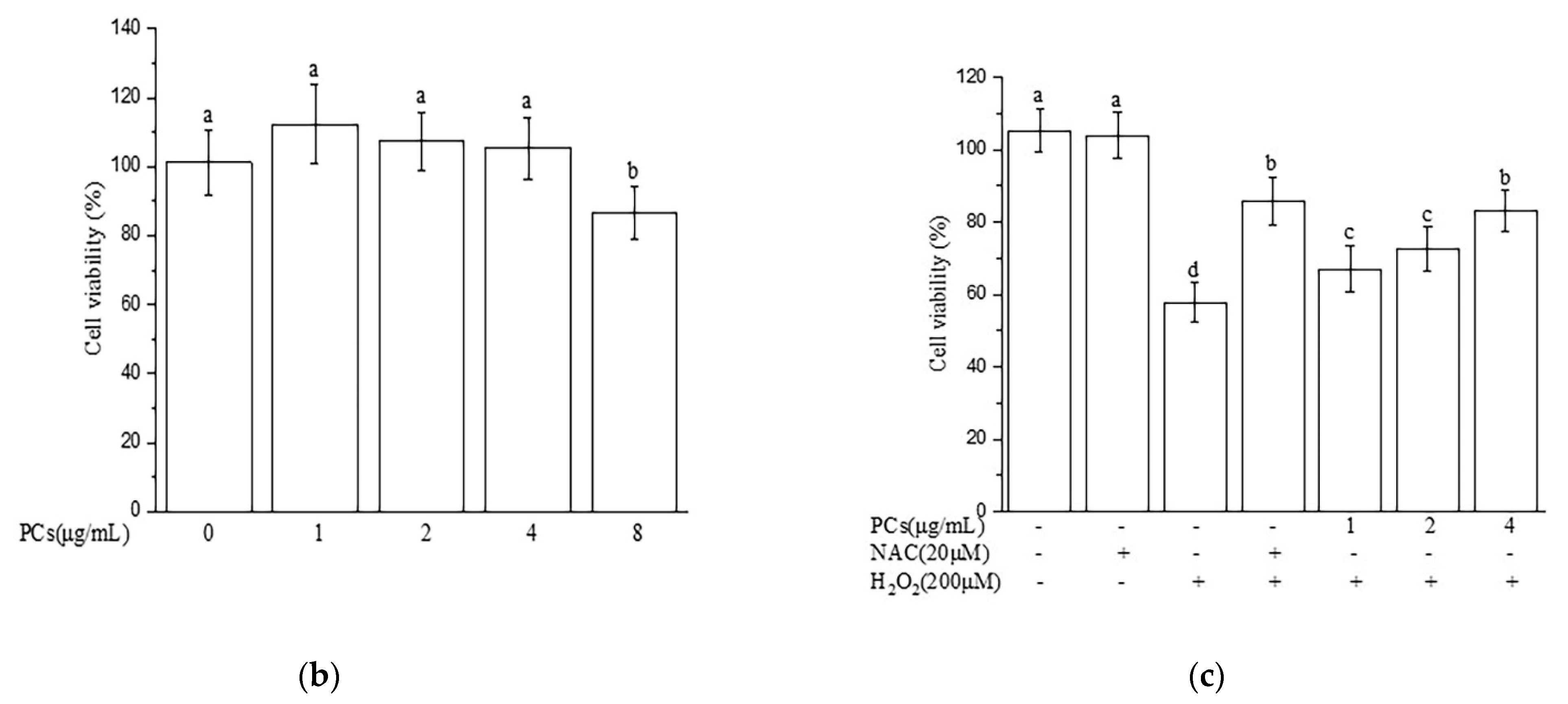

2.2. Effects of PCs on Oxidative Stress of PC12 Cells Treated with H2O2

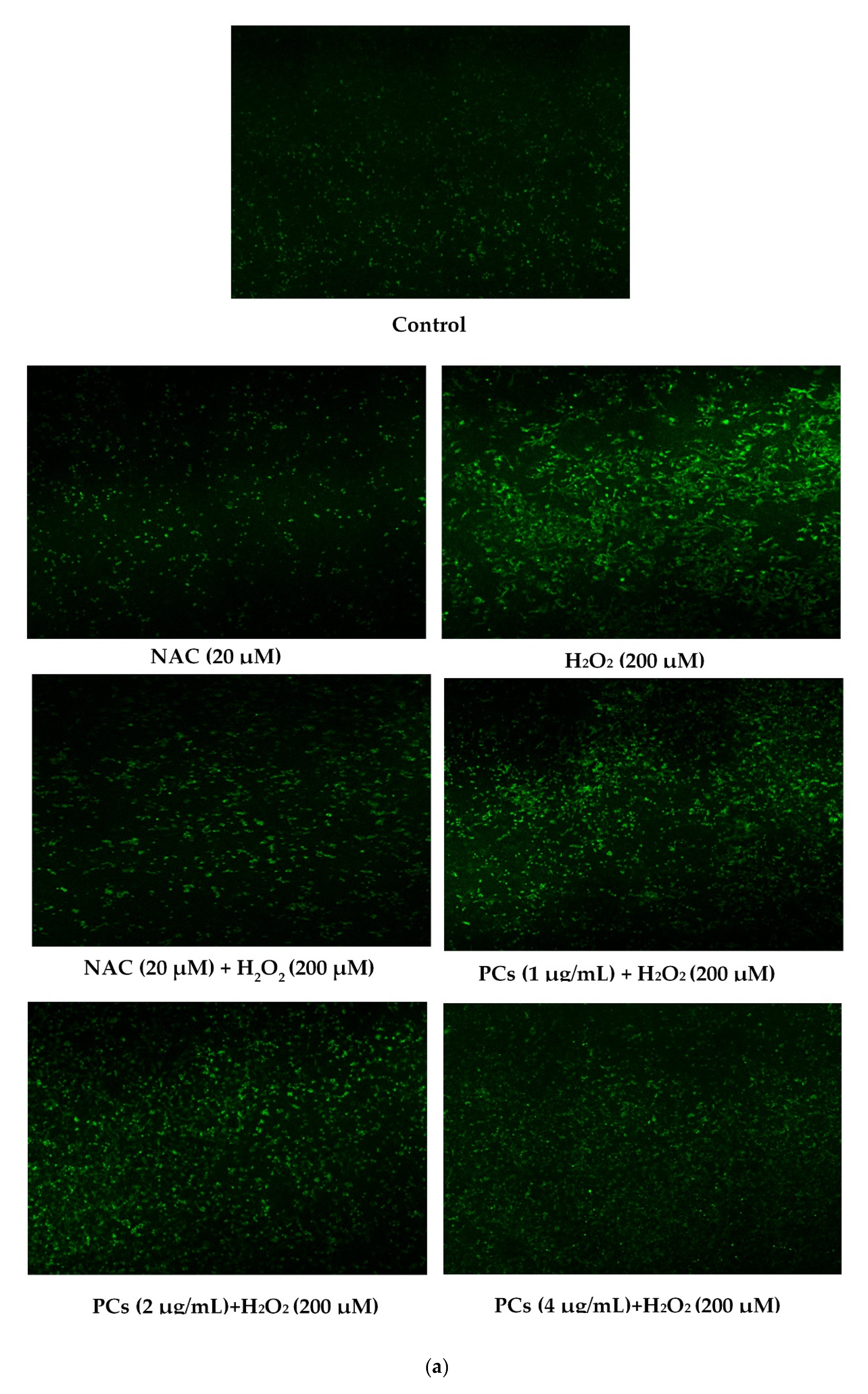

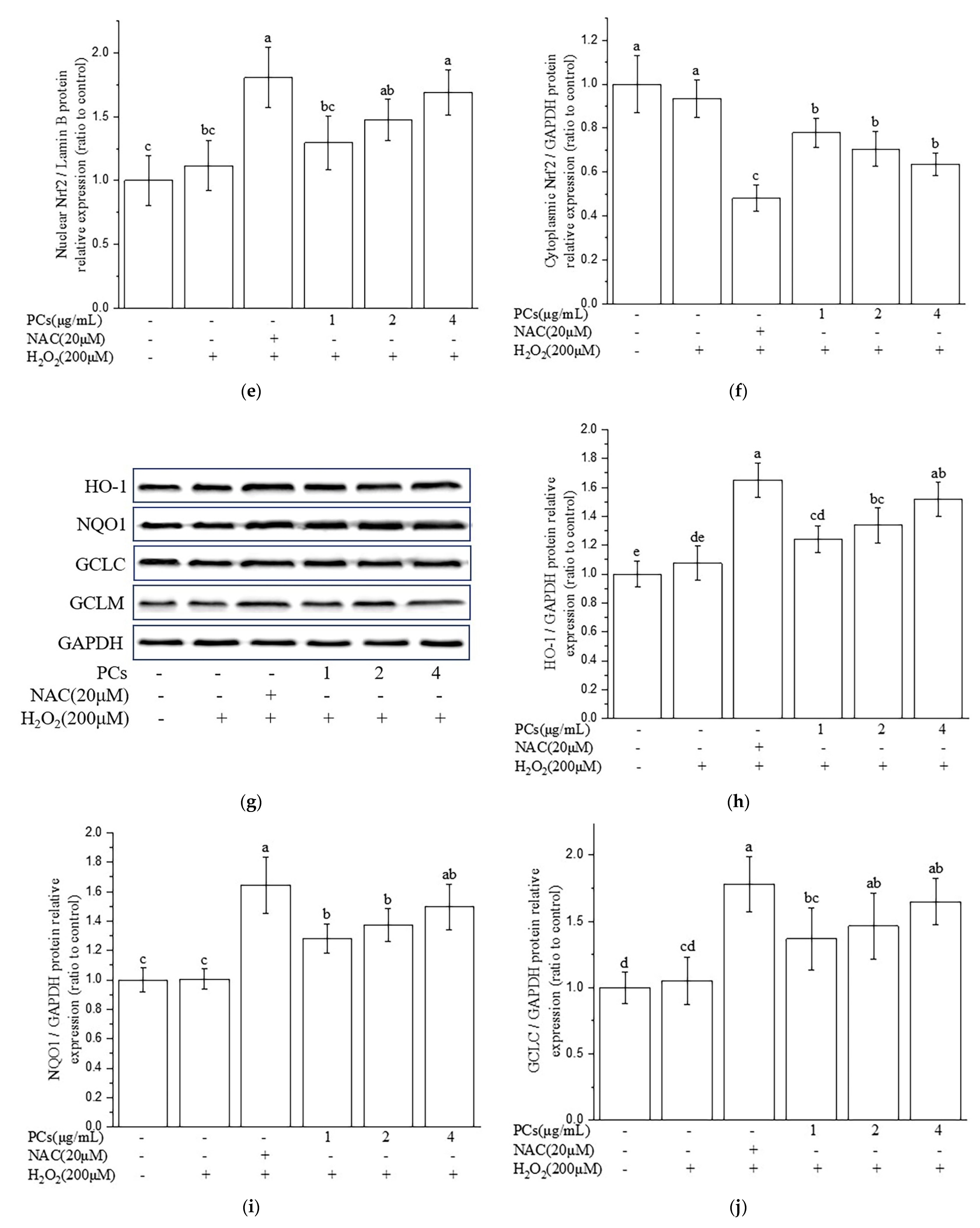

2.3. Effects of PCs on the Nuclear Factor-Erythroid 2-Related Factor 2 (Nrf2)/ARE Pathway in H2O2-Treated PC12 Cells

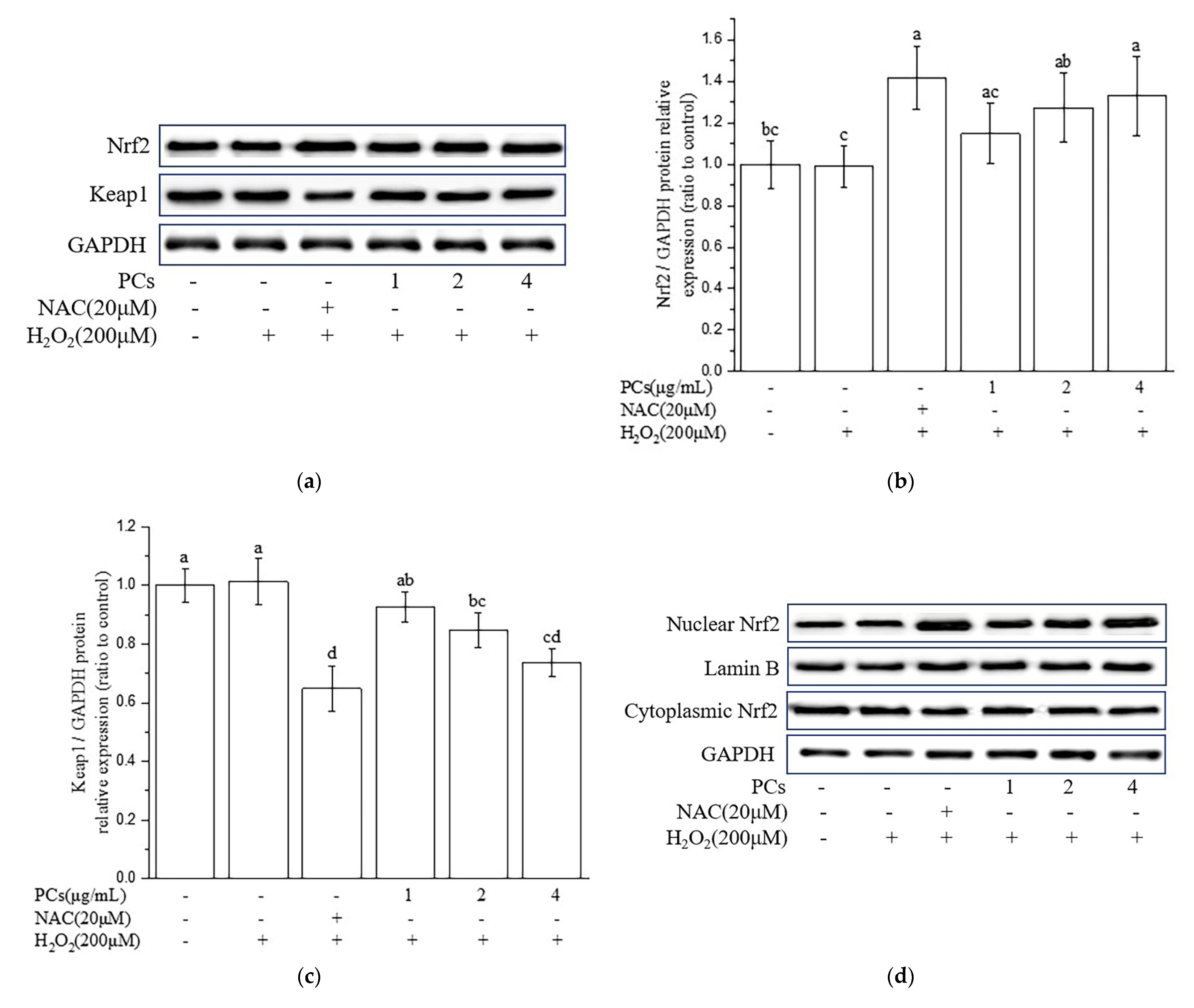

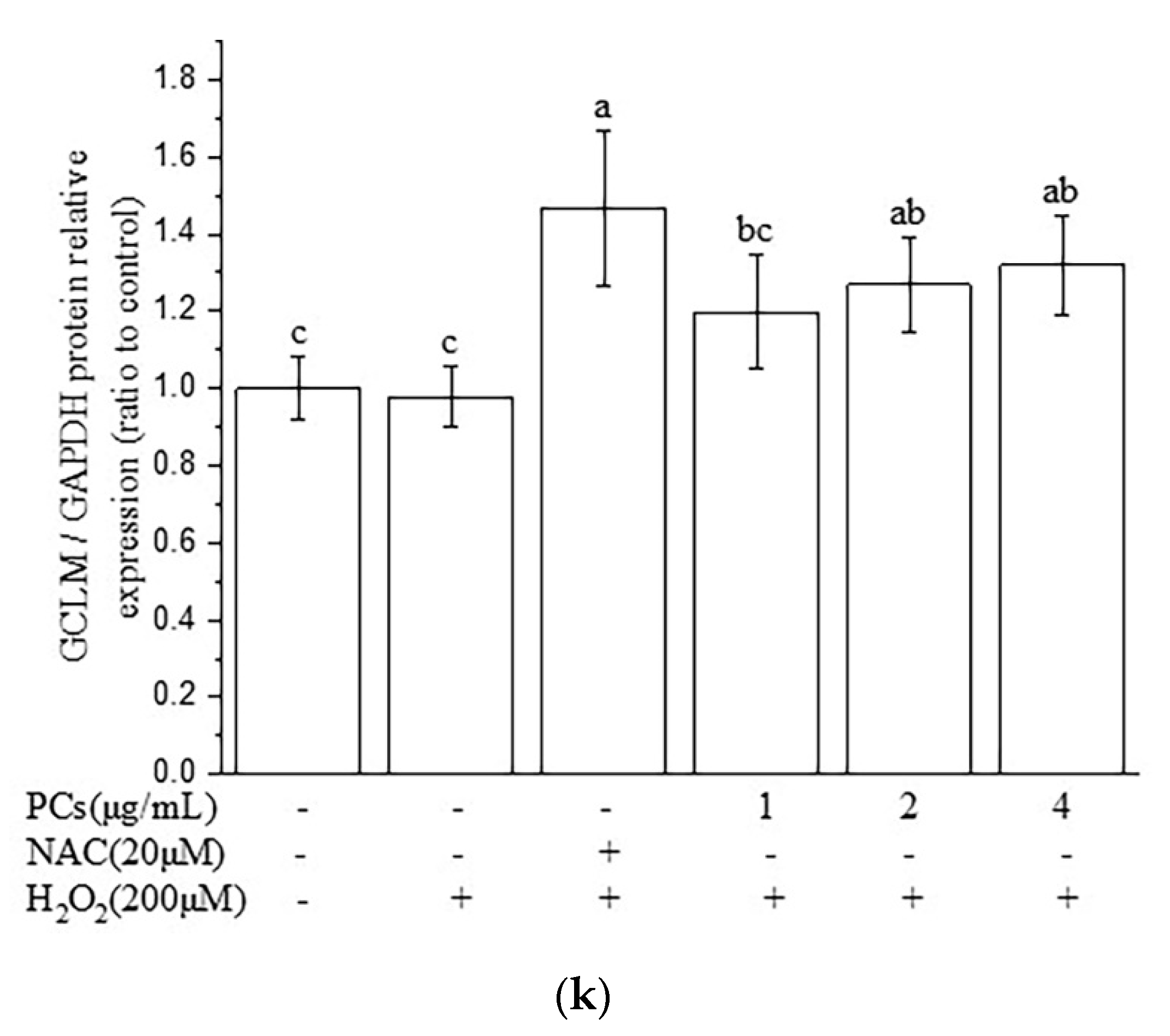

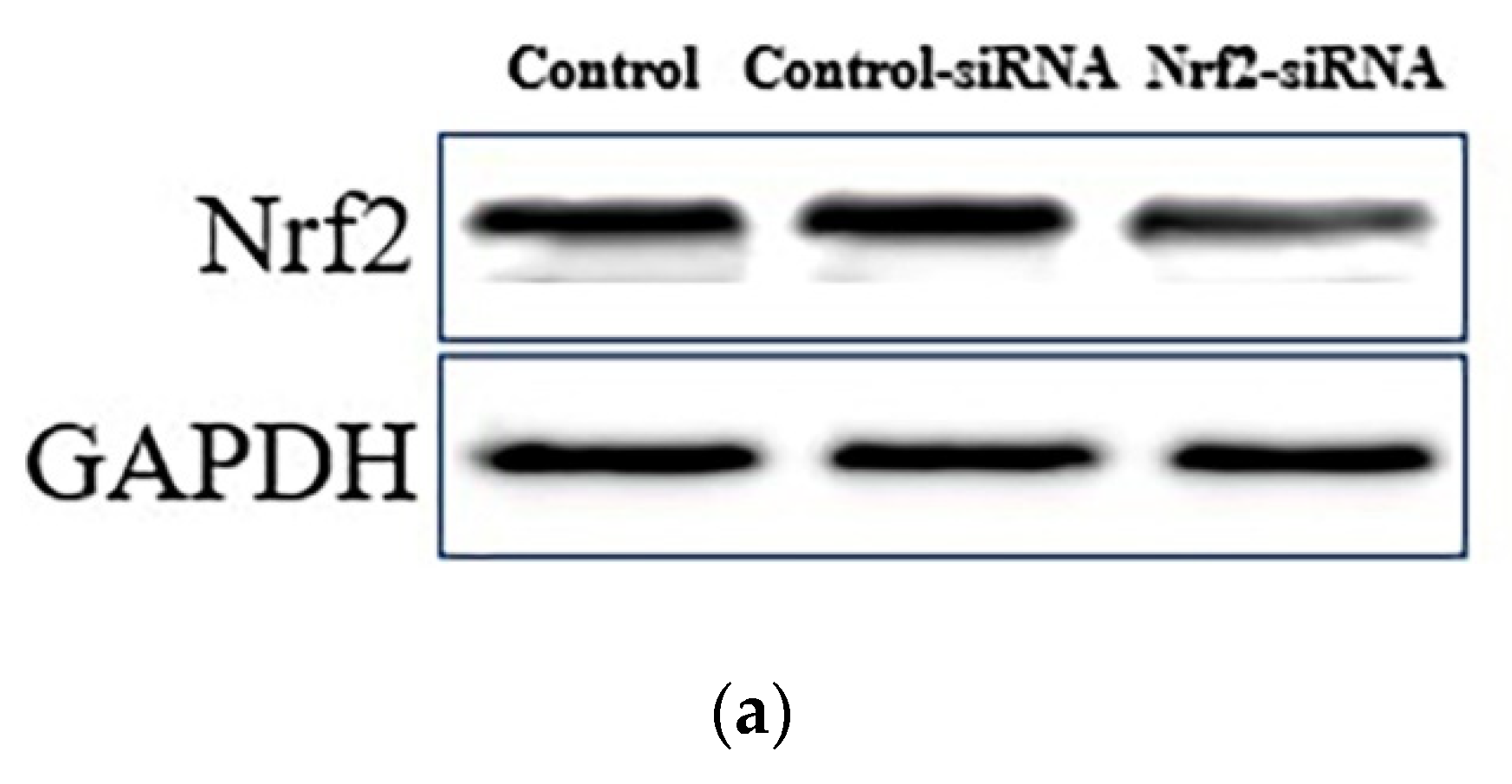

2.4. Nrf2/ARE Signaling Is Responsible for PCs-Mediated Antioxidative Effects

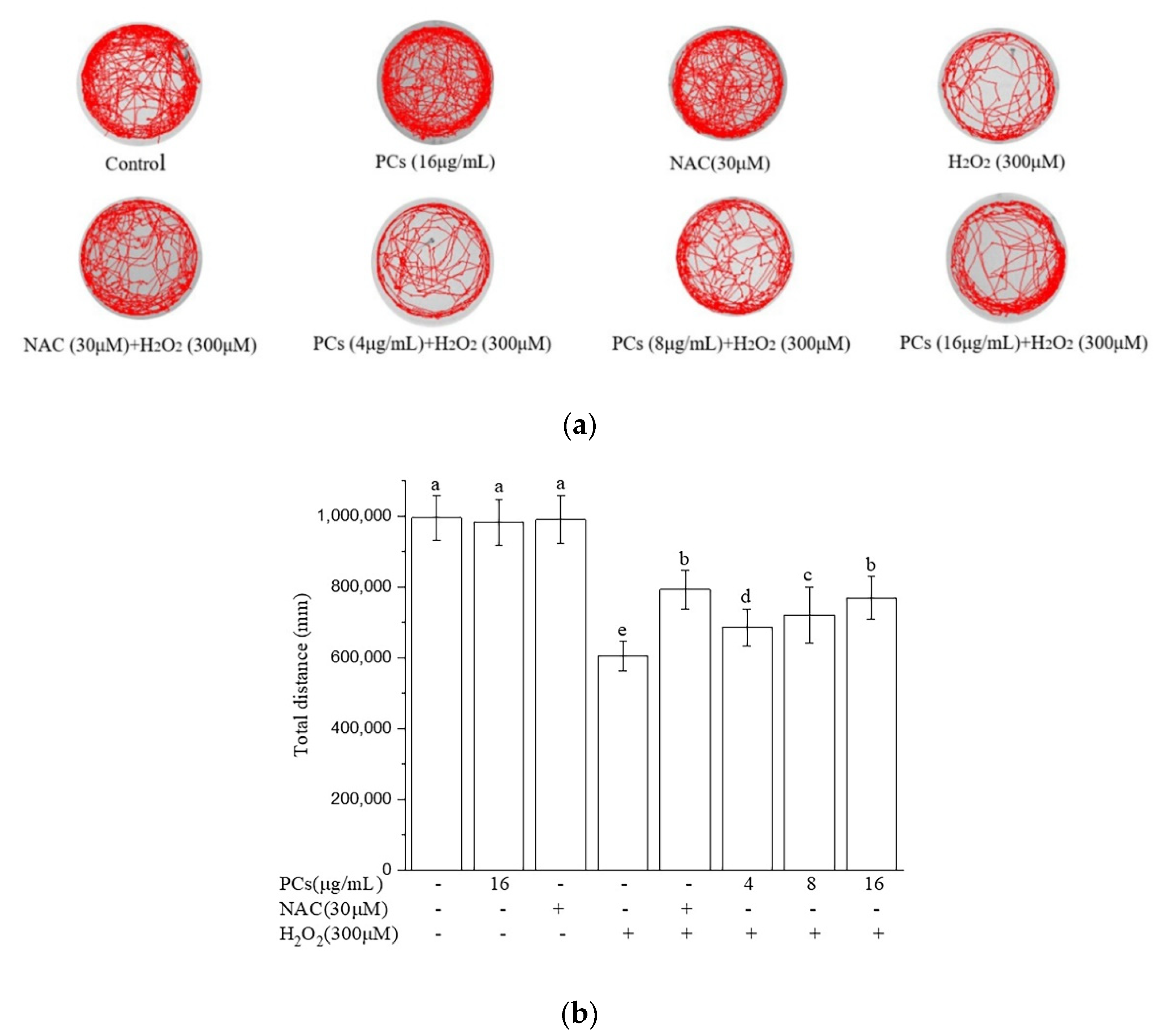

2.5. Effects of PCs on Motility of Zebrafish Larvae Following H2O2 Treatment

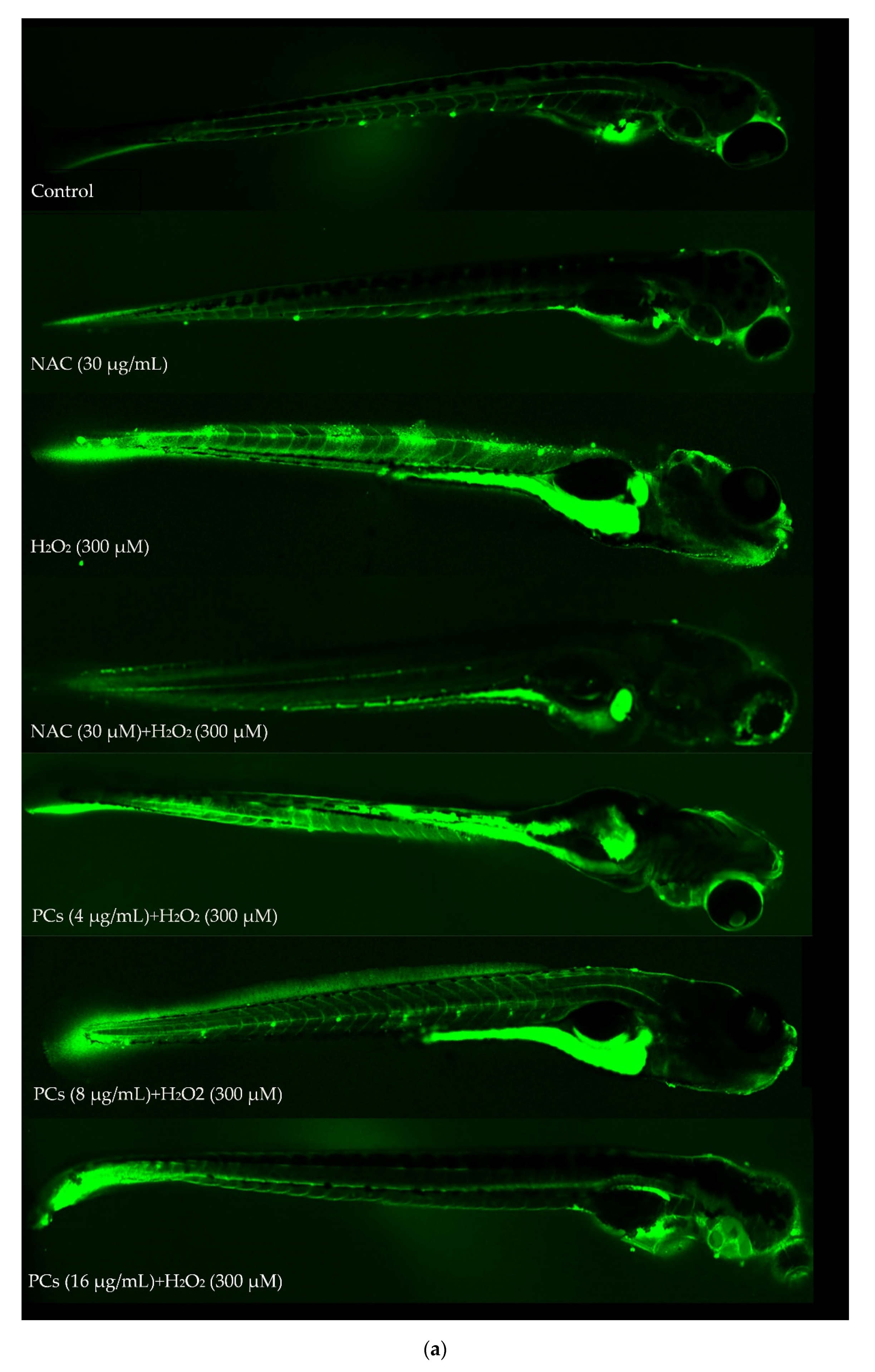

2.6. Effects of PCs on Oxidative Stress of Zebrafish Larvae Treated with H2O2

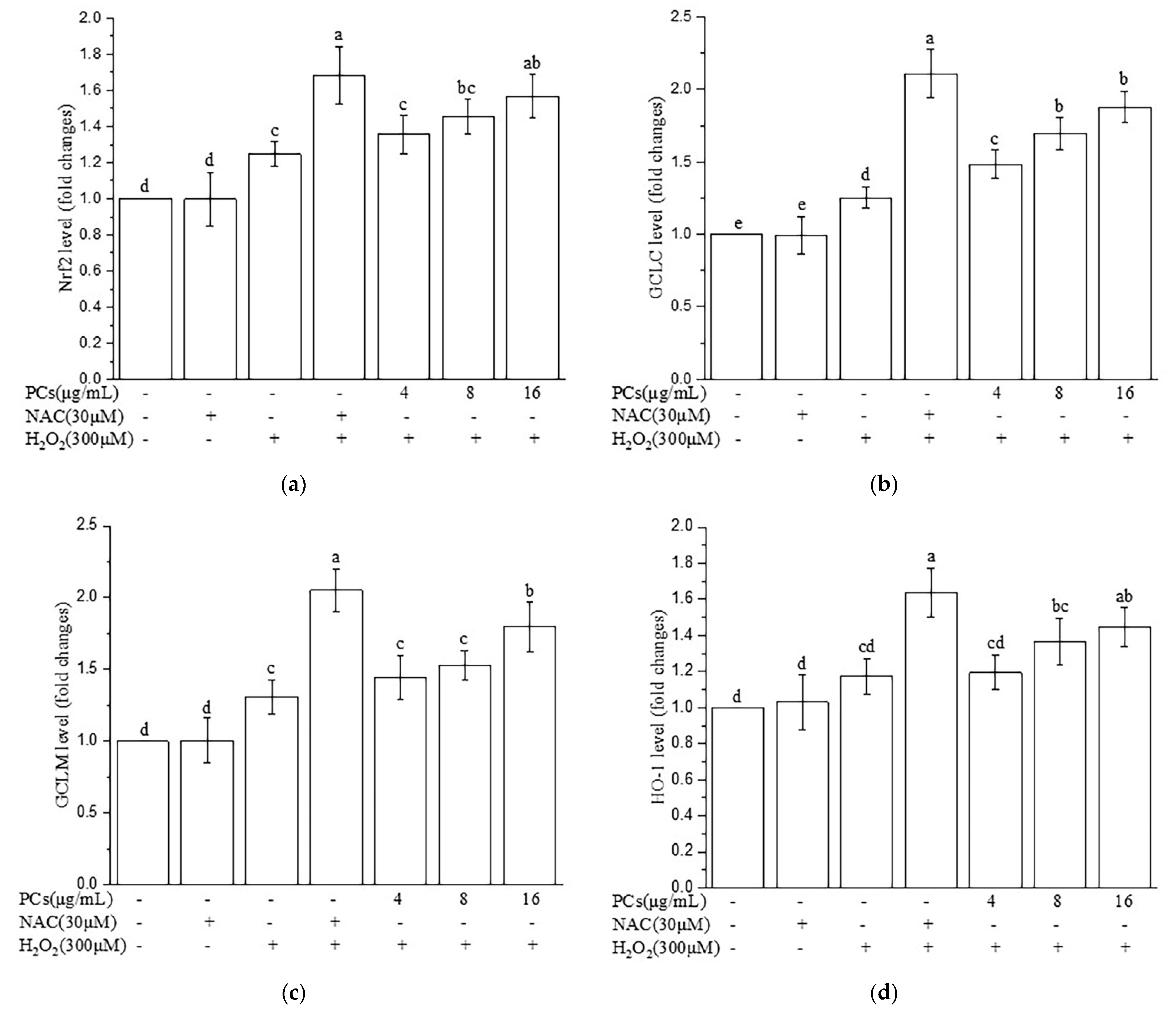

2.7. Effects of PCs on Nrf2/ARE Pathways in H2O2-Treated Zebrafish Larvae

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Chemicals and Reagents

4.2. Cell Culture

4.3. Cell Viability Assays

4.4. Fish Maintenance

4.5. ROS Measurements

4.6. Assessment of MDA, GSH-Px, SOD, and CAT

4.7. Total RNA Extraction, Reverse Transcription, and Quantitative Real-Time Polymerase Chain Reaction

4.8. Nrf2 siRNA Transfection

4.9. Preparation of Whole Cell, Cytoplasmic, and Nuclear Protein

4.10. Western Blotting

4.11. Locomotor Behavioral Assay

4.12. Statistical Analysis

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Sample Availability

References

- Brettschneider, J.; del Tredici, K.; Lee, V.M.Y.; Trojanowski, J.Q. Spreading of pathology in neurodegenerative diseases: A focus on human studies. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2015, 16, 109–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofer, S.M.; Berg, S.; Era, P. Evaluating the interdependence of aging-related changes in visual and auditory acuity, balance, and cognitive functioning. Psychol. Aging 2003, 18, 285–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frahm-Falkenberg, S.; Ibsen, R.; Kjellberg, J.; Jennum, P. Health, social and economic consequences of dementias: A comparative national cohort study. Eur. J. Neurol. 2016, 23, 1400–1407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coyle, J.; Puttfarcken, P. Oxidative stress, glutamate, and neurodegenerative disorders. Science 1993, 262, 689–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jo, D.S.; Cho, D.-H. Peroxisomal dysfunction in neurodegenerative diseases. Arch. Pharm. Res. 2019, 42, 393–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabner, B.J.; El-Agnaf, O.M.A.; Turnbull, S.; German, M.J.; Paleologou, K.E.; Hayashi, Y.; Cooper, L.J.; Fullwood, N.J.; Allsop, D. Hydrogen peroxide is generated during the very early stages of aggregation of the amyloid peptides implicated in Alzheimer disease and familial British dementia. J. Biol. Chem. 2005, 280, 35789–35792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pisoschi, A.M.; Pop, A. The role of antioxidants in the chemistry of oxidative stress: A review. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2015, 97, 55–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Lee, W.; Cui, Y.R.; Ahn, G.; Jeon, Y.-J. Protective effect of green tea catechin against urban fine dust particle-induced skin aging by regulation of NF-κB, AP-1, and MAPKs signaling pathways. Environ. Pollut. 2019, 252, 1318–1324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Lee, W.; Oh, J.Y.; Cui, Y.R.; Ryu, B.; Jeon, Y.-J. Protective effect of sulfated polysaccharides from celluclast-assisted extract of Hizikia fusiforme against ultraviolet B-induced skin damage by regulating NF-κB, AP-1, and MAPKs signaling pathways in vitro in human dermal fibroblasts. Mar. Drugs 2018, 16, 239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terra, X.; Fernández-Larrea, J.; Pujadas, G.; Ardèvol, A.; Bladé, C.; Salvadó, J.; Arola, L.; Blay, M. Inhibitory effects of grape seed procyanidins on foam cell formation in vitro. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2009, 57, 2588–2594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, L.; Kelm, M.A.; Hammerstone, J.F.; Beecher, G.; Holden, J.; Haytowitz, D.; Gebhardt, S.; Prior, R.L. Concentrations of proanthocyanidins in common foods and estimations of normal consumption. J. Nutr. 2004, 134, 613–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Rio, D.; Rodriguez-Mateos, A.; Spencer, J.P.E.; Tognolini, M.; Borges, G.; Crozier, A. Dietary (poly)phenolics in human health: Structures, bioavailability, and evidence of protective effects against chronic diseases. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2013, 18, 1818–1892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bagchi, D.; Garg, A.; Krohn, R.L.; Bagchi, M.; Tran, M.X.; Stohs, S.J. Oxygen free radical scavenging abilities of vitamins C and E, and a grape seed proanthocyanidin extract in vitro. Res. Commun. Mol. Pathol. Pharmacol. 1997, 95, 179–189. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ellett, F.; Lieschke, G.J. Zebrafish as a model for vertebrate hematopoiesis. Curr. Opin. Pharmacol. 2010, 10, 563–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kalueff, A.V.; Stewart, A.M.; Gerlai, R. Zebrafish as an emerging model for studying complex brain disorders. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 2014, 35, 63–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, S.D.M.; Verveer, P.J.; Bastiaens, P.I.H. Growth factor-induced MAPK network topology shapes Erk response determining PC-12 cell fate. Nat. Cell Biol. 2007, 9, 324–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenberg, D.A.; Jin, K. From angiogenesis to neuropathology. Nature 2005, 438, 954–959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shui, G.; Bao, Y.-M.; Bo, J.; An, L.-J. Protective effect of protocatechuic acid from Alpinia oxyphylla on hydrogen peroxide-induced oxidative PC12 cell death. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2006, 538, 73–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, X.; Zhang, L.; Hu, J.; Sun, L.; Du, G. Neuroprotective effects of tetramethylpyrazine on hydrogen peroxide-induced apoptosis in PC12 cells. Cell Biol. Int. 2007, 31, 438–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, B.; Liu, J.H.; Bao, Y.M.; An, L.J. Hydrogen peroxide-induced apoptosis in pc12 cells and the protective effect of puerarin. Cell Biol. Int. 2003, 27, 1025–1031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, X.; Zhang, H.; Duan, Y.; Chen, G. Protective effects of radish (Raphanus sativus L.) leaves extract against hydrogen peroxide-induced oxidative damage in human fetal lung fibroblast (MRC-5) cells. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2018, 103, 406–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Wu, Y.; Wang, Y.; Fu, A.; Gong, L.; Li, W.; Li, Y. Bacillus amyloliquefaciens SC06 alleviates the oxidative stress of IPEC-1 via modulating Nrf2/Keap1 signaling pathway and decreasing ROS production. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2017, 101, 3015–3026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bettaib, J.; Talarmin, H.; Droguet, M.; Magné, C.; Boulaaba, M.; Giroux-Metges, M.-A.; Ksouri, R. Tamarix gallica phenolics protect IEC-6 cells against H2O2 induced stress by restricting oxidative injuries and MAPKs signaling pathways. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2017, 89, 490–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bettaib, J.; Talarmin, H.; Kalai, F.Z.; Giroux-Metges, M.-A.; Ksouri, R. Limoniastrum guyonianum prevents H2O2-induced oxidative damage in IEC-6 cells by enhancing enzyamtic defense, reducing glutathione depletion and JNK phosphorylation. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2017, 95, 1404–1411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kondo, K.; Klco, J.; Nakamura, E.; Lechpammer, M.; Kaelin, W.G. Inhibition of HIF is necessary for tumor suppression by the von Hippel-Lindau protein. Cancer Cell 2002, 1, 237–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razavi, S.-M.; Gholamin, S.; Eskandari, A.; Mohsenian, N.; Ghorbanihaghjo, A.; Delazar, A.; Rashtchizadeh, N.; Keshtkar-Jahromi, M.; Argani, H. Red grape seed extract improves lipid profiles and decreases oxidized low-density lipoprotein in patients with mild hyperlipidemia. J. Med. Food 2013, 16, 255–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, X.; Gong, S.; Su, L.; Li, C.; Kong, Y. Neuroprotective effects of allicin on ischemia-reperfusion brain injury. Oncotarget 2017, 8, 104492–104507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Michaelis, E.K. Selective neuronal vulnerability to oxidative stress in the brain. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2010, 2, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uttara, B.; Singh, A.V.; Zamboni, P.; Mahajan, R.T. Oxidative stress and neurodegenerative diseases: A review of upstream and downstream antioxidant therapeutic options. Curr. Neuropharmacol. 2009, 7, 65–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fang, L.; Li, M.; Zhao, L.; Han, S.; Li, Y.; Xiong, B.; Jiang, L. Dietary grape seed procyanidins suppressed weaning stress by improving antioxidant enzyme activity and mRNA expression in weanling piglets. J. Anim. Physiol. Anim. Nutr. 2020, 104, 1178–1185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, F.; Li, Y.; Feng, T.; Du, Y.; Ren, F.; Zhang, L.; Ma, S.; Li, F.; Wang, P.; Hu, J. Grape seed procyanidin extract (GSPE) improves goat sperm quality when preserved at 4 °C. Animals 2019, 9, 810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McMahon, M.; Thomas, N.; Itoh, K.; Yamamoto, M.; Hayes, J.D. Redox-regulated turnover of Nrf2 is determined by at least two separate protein domains, the redox-sensitive Neh2 degron and the redox-insensitive Neh6 degron. J. Biol. Chem. 2004, 279, 31556–31567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, M.; Li, H.; Liu, Q.; Liu, F.; Tang, L.; Li, C.; Yuan, Y.; Zhan, Y.; Xu, W.; Li, W.; et al. Nuclear factor p65 interacts with Keap1 to repress the Nrf2-ARE pathway. Cell. Signal. 2011, 23, 883–892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Itoh, K.; Igarashi, K.; Hayashi, N.; Nishizawa, M.; Yamamoto, M. Cloning and characterization of a novel erythroid cell-derived CNC family transcription factor heterodimerizing with the small Maf family proteins. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1995, 15, 4184–4193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hybertson, B.M.; Gao, B.; Bose, S.K.; McCord, J.M. Oxidative stress in health and disease: The therapeutic potential of Nrf2 activation. Mol. Aspects Med. 2011, 32, 234–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Itoh, K.; Wakabayashi, N.; Katoh, Y.; Ishii, T.; Igarashi, K.; Engel, J.D.; Yamamoto, M. Keap1 represses nuclear activation of antioxidant responsive elements by Nrf2 through binding to the amino-terminal Neh2 domain. Genes Dev. 1999, 13, 76–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kobayashi, A.; Kang, M.-I.; Okawa, H.; Ohtsuji, M.; Zenke, Y.; Chiba, T.; Igarashi, K.; Yamamoto, M. Oxidative stress sensor Keap1 functions as an adaptor for Cul3-based E3 ligase to regulate proteasomal degradation of Nrf2. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2004, 24, 7130–7139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, M.-C.; Ji, J.-A.; Jiang, Z.-Y.; You, Q.-D. The Keap1-Nrf2-ARE pathway as a potential preventive and therapeutic target: An update. Med. Res. Rev. 2016, 36, 924–963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ungvari, Z.; Bagi, Z.; Feher, A.; Recchia, F.A.; Sonntag, W.E.; Pearson, K.; de Cabo, R.; Csiszar, A. Resveratrol confers endothelial protection via activation of the antioxidant transcription factor Nrf2. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2010, 299, H18–H24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidlin, C.J.; Dodson, M.B.; Madhavan, L.; Zhang, D.D. Redox regulation by NRF2 in aging and disease. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2019, 134, 702–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, S.; Hou, Y.; Yao, J.; Fang, J. Activation of Nrf2-driven antioxidant enzymes by cardamonin confers neuroprotection of PC12 cells against oxidative damage. Food Funct. 2017, 8, 997–1007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mi, Y.; Zhang, W.; Tian, H.; Li, R.; Huang, S.; Li, X.; Qi, G.; Liu, X. EGCG evokes Nrf2 nuclear translocation and dampens PTP1B expression to ameliorate metabolic misalignment under insulin resistance condition. Food Funct. 2018, 9, 1510–1523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, S.; Tang, Q.; Jin, J.; Zheng, G.; Xu, J.; Huang, W.; Li, X.; Shang, P.; Liu, H. Polydatin inhibits the IL-1β-induced inflammatory response in human osteoarthritic chondrocytes by activating the Nrf2 signaling pathway and ameliorates murine osteoarthritis. Food Funct. 2018, 9, 1701–1712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Tang, B.; Feng, Y.; Tang, F.; Hoi, M.P.-M.; Su, Z.; Lee, S.M.-Y. Pinostrobin exerts neuroprotective actions in neurotoxin-induced Parkinson’s disease models through Nrf2 induction. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2018, 66, 8307–8318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kimmel, C.B.; Ballard, W.W.; Kimmel, S.R.; Ullmann, B.; Schilling, T.F. Stages of embryonic development of the zebrafish. Dev. Dyn. 1995, 203, 253–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, M.; He, Q.; Zhang, S.; Cui, Y.; Han, L.; Liu, K. Gastrodin suppresses pentylenetetrazole-induced seizures progression by modulating oxidative stress in zebrafish. Neurochem. Res. 2018, 43, 904–917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, B.; Ren, B.; Guo, R.; Zhang, W.; Ma, S.; Yao, Y.; Yuan, T.; Liu, Z.; Liu, X. Supplementation of lycopene attenuates oxidative stress induced neuroinflammation and cognitive impairment via Nrf2/NF-κB transcriptional pathway. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2017, 109, 505–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Genes | Forward Primer | Reverse Primer |

|---|---|---|

| β-Actin | CACTGAGGCTCCCCTGAATC | GGGTCACACCATCACCAGAG |

| Nrf2 | CTGCTGTCACTCCCAGAGTT | GCCGTAGTTTTGGGTTGGTG |

| HO-1 | AAGAGCTGGACAGAAACGCA | AGAAGTGCTCCAAGTCCTGC |

| GCLC | CTCCTCACAGTCACGGCATT | TGAATGGAGACGGGGTGTTG |

| GCLM | AAGCCAGACACTGACACACC | ATCTGGAGGCATCACACAGC |

| NQO1 | AAGCCTCTGTCCTTTGCTCC | TGCTGTGGTAATGCCGTAGG |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Chen, J.; Chen, Y.; Zheng, Y.; Zhao, J.; Yu, H.; Zhu, J.; Li, D. Neuroprotective Effects and Mechanisms of Procyanidins In Vitro and In Vivo. Molecules 2021, 26, 2963. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules26102963

Chen J, Chen Y, Zheng Y, Zhao J, Yu H, Zhu J, Li D. Neuroprotective Effects and Mechanisms of Procyanidins In Vitro and In Vivo. Molecules. 2021; 26(10):2963. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules26102963

Chicago/Turabian StyleChen, Juan, Yixuan Chen, Yangfan Zheng, Jiawen Zhao, Huilin Yu, Jiajin Zhu, and Duo Li. 2021. "Neuroprotective Effects and Mechanisms of Procyanidins In Vitro and In Vivo" Molecules 26, no. 10: 2963. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules26102963

APA StyleChen, J., Chen, Y., Zheng, Y., Zhao, J., Yu, H., Zhu, J., & Li, D. (2021). Neuroprotective Effects and Mechanisms of Procyanidins In Vitro and In Vivo. Molecules, 26(10), 2963. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules26102963