Targeting Oncogenic Protein-Protein Interactions by Diversity Oriented Synthesis and Combinatorial Chemistry Approaches

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Targeting Oncogenic Protein-Protein Interactions with Small Molecules

3. Antagonists of p53-Mdm2 Interactions

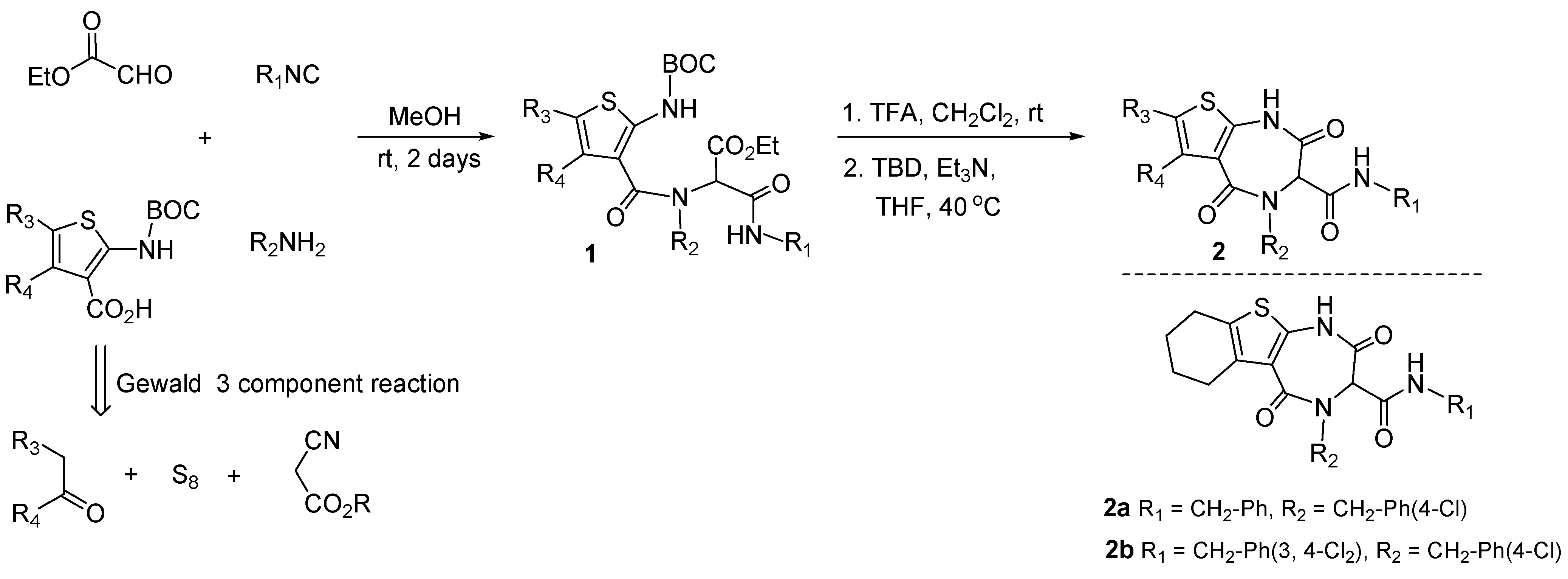

3.1. Antagonists of p53-Mdm2 Interactions Based on 1,4-thienodiazepine-2,5-dione Based Core Structures

4. Targeting Anti-Apoptotic Members of the Bcl-2 Family Proteins

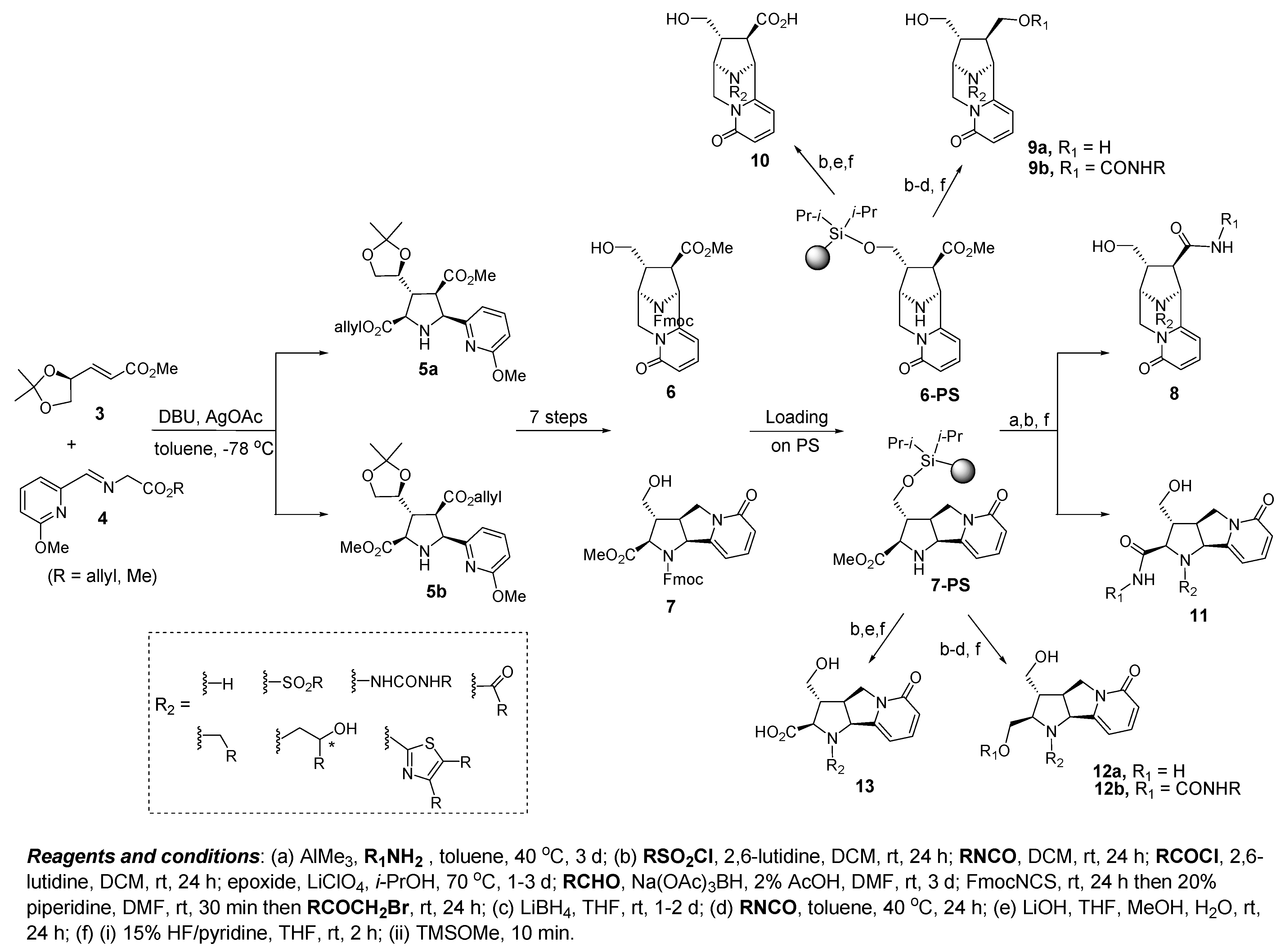

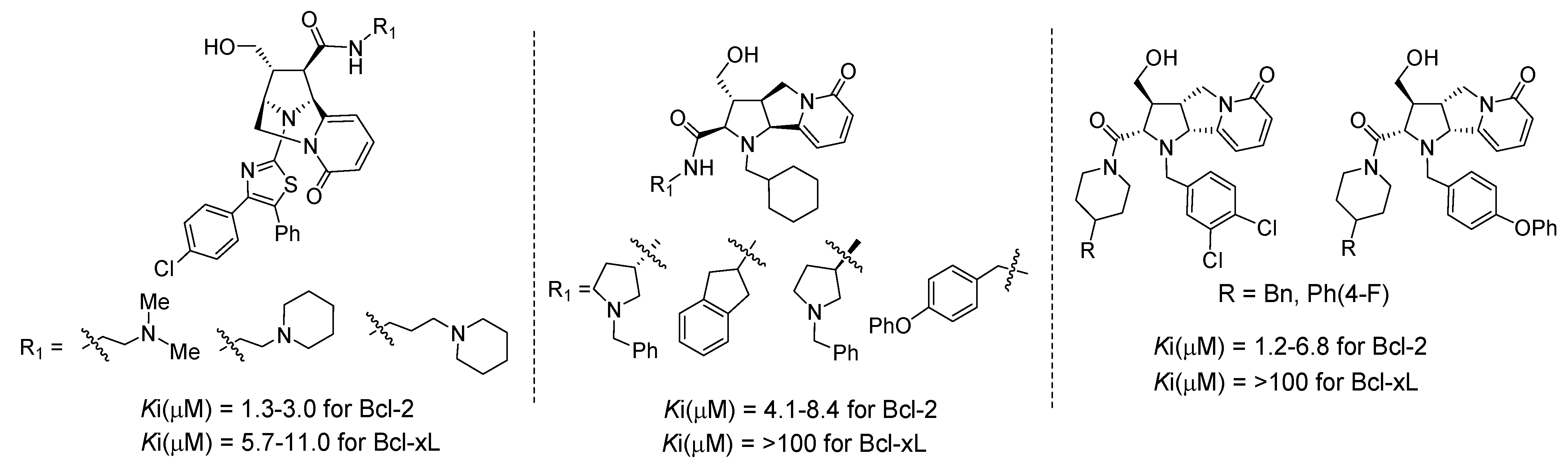

4.1. Discovery of Novel Bcl-2 Inhibitors Based on Rigid Pyridone Scaffolds

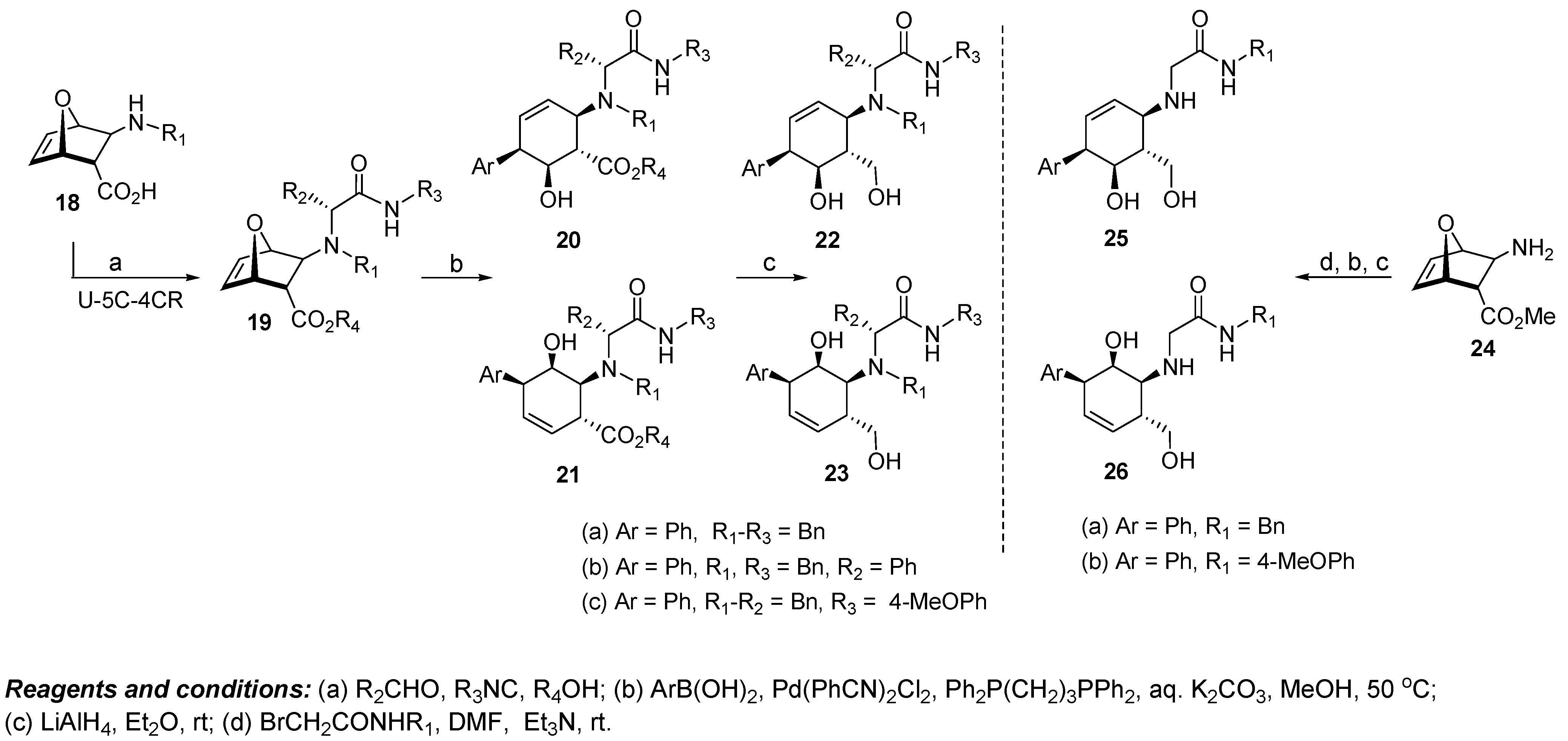

4.2. Discovery of Bcl-2 Inhibitors from an Isoxazolidine Library

4.3. Discovery of Bcl-xL Antagonists Resulting from Oxabicyclic Scaffolds

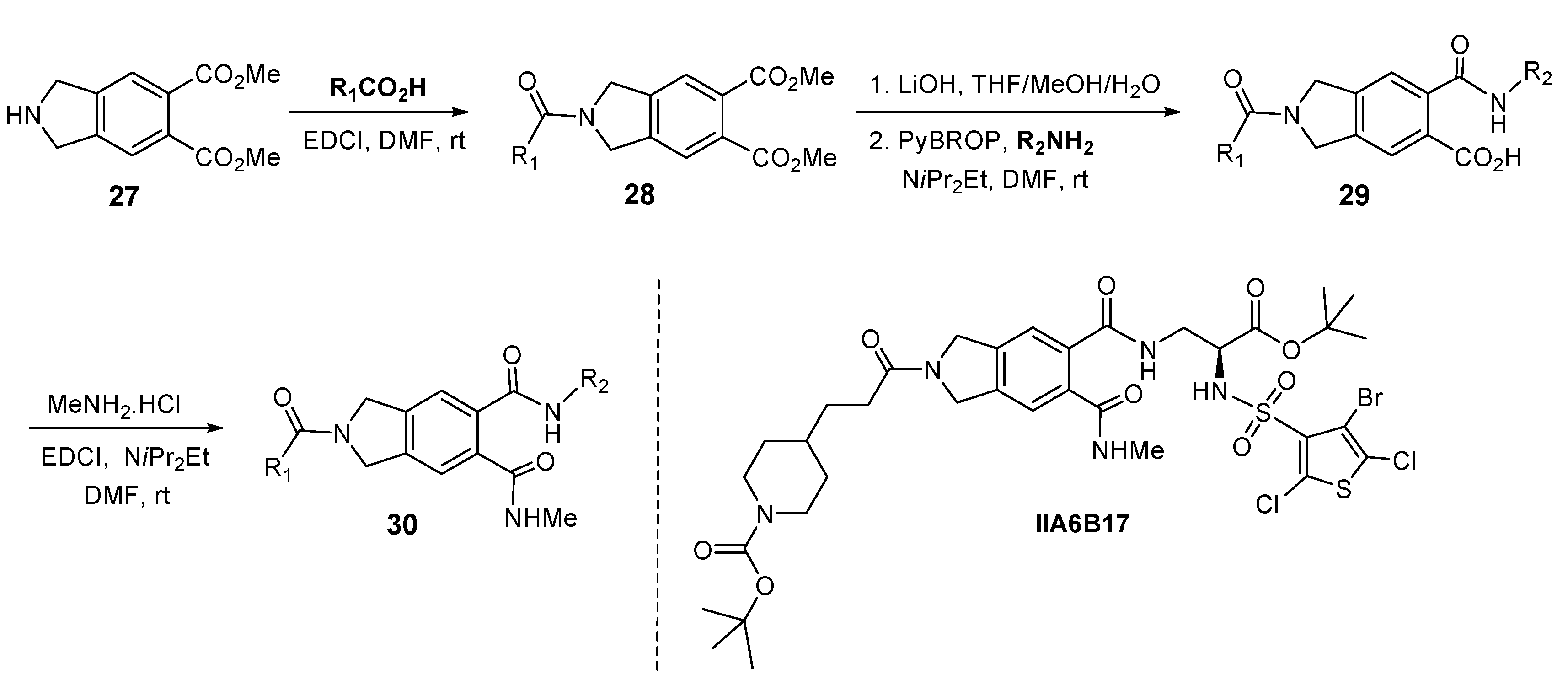

5. Isoindoline Based Antagonists of the Myc-Max Protein-Protein Interaction

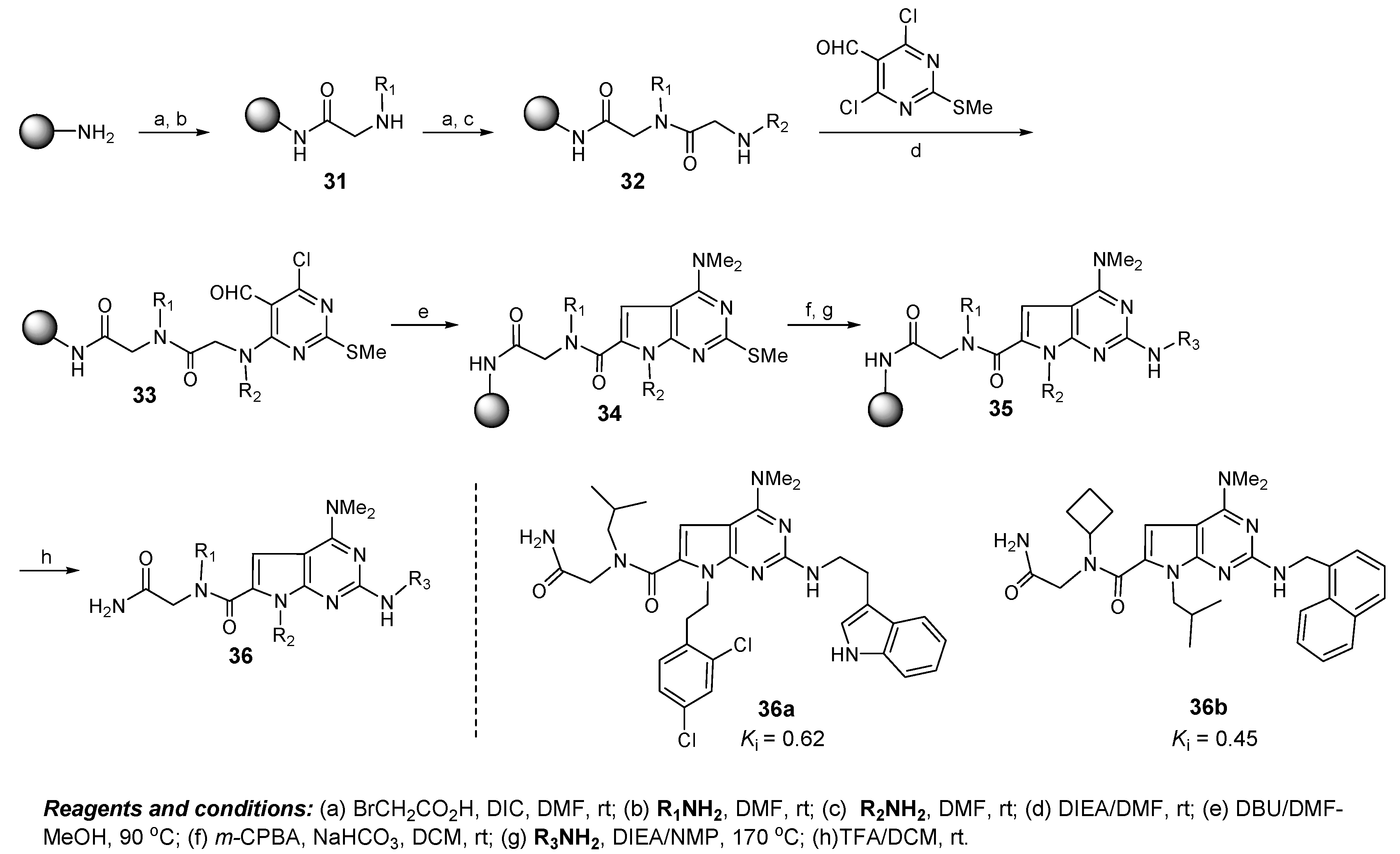

6. Discovery of Dual Mdmx/Mdm2 Inhibitors Based on Pyrrolopyrimidine Scaffolds as A-Helix Mimetics

7. Future Directions

Acknowledgements

References and Notes

- Jones, P.A.; Baylin, S.B. The fundamental role of epigenetic events in cancer. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2002, 3, 415–428. [Google Scholar]

- Rosen, J.M.; Jordan, C.T. The increasing complexity of the cancer stem cell paradigm. Science 2009, 324, 1670–1673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) Research Network. Comprehensive genomic characterization defines human glioblastoma genes and core pathways. Nature 2008, 455, 1061–1068. [CrossRef]

- Anderson, K.; Lutz, C.; van Delft, F.W.; Bateman, C.M.; Guo, Y.; Colman, S.M.; Kempski, H.; Moorman, A.V.; Titley, I.; Swansbury, J.; Kearney, L.; Enver, T.; Greaves, M. Genetic variegation of clonal architecture and propagating cells in leukaemia. Nature 2011, 469, 356–361. [Google Scholar]

- Sawyers, C. Targeted cancer therapy. Nature 2004, 432, 294–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capdeville, R.; Buchdunger, E.; Zimmermann, J.; Matter, A. Glivec (STI571, imatinib), a rationally developed, targeted anticancer drug. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2002, 1, 493–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Bono, J.S.; Ashworth, A. Translating cancer research into targeted therapeutics. Nature 2010, 467, 543–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grignani, F.; Fagioli, M.; Alcalay, M.; Longo, L.; Pandolfi, P.P.; Donti, E.; Biondi, A.; Lo Coco, F.; Pelicci, P.G. Acute promyelocytic leukemia: From genetics to treatment. Blood 1994, 83, 10–25. [Google Scholar]

- Burris, H.A., III. Shortcomings of current therapies for non-small-cell lung cancer: Unmet medical needs. Oncogene 2009, 28 (Suppl. 1), S4–S13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harousseau, J.L.; Palumbo, A.; Richardson, P.G.; Schlag, R.; Dimopoulos, M.A.; Shpilberg, O.; Kropff, M.; Kentos, A.; Cavo, M.; Golenkov, A.; et al. Superior outcomes associated with complete response in newly diagnosed multiple myeloma patients treated with nonintensive therapy: analysis of the phase 3 VISTA study of bortezomib plus melphalan-prednisone versus melphalan-prednisone. Blood 2010, 116, 3743–3750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McConkey, D.J. Bortezomib paradigm shift in myeloma. Blood 2009, 114, 931–932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saijo, N. Targeted therapies: Tyrosine-kinase inhibitors--new standard for NSCLC therapy. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 2010, 7, 618–619. [Google Scholar]

- Meric-Bernstam, F.; Gonzalez-Angulo, A.M. Targeting the mTOR signaling network for cancer therapy. J. Clin. Oncol. 2009, 27, 2278–2287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sausville, E.A.; Carducci, M.A. Making bad cells go good: the promise of epigenetic therapy. J. Clin. Oncol. 2005, 23, 3875–3876. [Google Scholar]

- Karberg, S. Switching on epigenetic therapy. Cell 2009, 139, 1029–1031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jemal, A.; Bray, F.; Center, M.M.; Ferlay, J.; Ward, E.; Forman, D. Global cancer statistics. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2011, 61, 69–90. [Google Scholar]

- Check Hayden, E. Cancer complexity slows quest for cure. Nature 2008, 455, 148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stewart, D.J.; Kurzrock, R. Cancer: the road to Amiens. J. Clin. Oncol. 2009, 27, 328–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, P.B.; Onder, T.T.; Jiang, G.; Tao, K.; Kuperwasser, C.; Weinberg, R.A.; Lander, E.S. Identification of selective inhibitors of cancer stem cells by high-throughput screening. Cell 2009, 138, 645–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gatenby, R.A. A change of strategy in the war on cancer. Nature 2009, 459, 508–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamb, A.; Wee, S.; Lengauer, C. Why is cancer drug discovery so difficult? Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2007, 6, 115–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fry, D.C.; Vassilev, L.T. Targeting protein-protein interactions for cancer therapy. J. Mol. Med. 2005, 83, 955–963. [Google Scholar]

- Sugaya, N.; Ikeda, K. Assessing the druggability of protein-protein interactions by a supervised machine-learning method. BMC Bioinformatics 2009, 10, 263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, C.; Li, H.; Zhou, C.; Zhang, L.; Zou, J.; Guo, Z. Multi-level reproducibility of signature hubs in human interactome for breast cancer metastasis. BMC Syst. Biol. 2010, 4, 151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujii, N.; You, L.; Xu, Z.; Uematsu, K.; Shan, J.; He, B.; Mikami, I.; Edmondson, L.R.; Neale, G.; Zheng, J.; Guy, R.K.; Jablons, D.M. An antagonist of dishevelled protein-protein interaction suppresses beta-catenin-dependent tumor cell growth. Cancer Res. 2007, 67, 573–579. [Google Scholar]

- Harris, C.C. Protein-protein interactions for cancer therapy. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2006, 103, 1659–1660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araujo, R.P.; Liotta, L.A.; Petricoin, E.F. Proteins, drug targets and the mechanisms they control: the simple truth about complex networks. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2007, 6, 871–880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

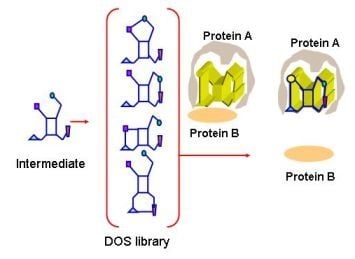

- Dandapani, S.; Marcaurelle, L.A. Current strategies for diversity-oriented synthesis. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 2010, 14, 362–370. [Google Scholar]

- Schreiber, S.L. Target-oriented and diversity-oriented organic synthesis in drug discovery. Science 2000, 287, 1964–1969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, G.L.; Wyatt, E.E.; Spring, D.R. Enriching chemical space with diversity-oriented synthesis. Curr. Opin. Drug Discov. Devel. 2006, 9, 700–712. [Google Scholar]

- Bauer, R.A.; Wurst, J.M.; Tan, D.S. Expanding the range of 'druggable' targets with natural product-based libraries: an academic perspective. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 2010, 14, 308–314. [Google Scholar]

- Lipinski, C.A.; Lombardo, F.; Dominy, B.W.; Feeney, P.J. Experimental and computational approaches to estimate solubility and permeability in drug discovery and development settings. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2001, 46, 3–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stockwell, B.R. Chemical genetics: ligand-based discovery of gene function. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2000, 1, 116–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilk, W.; Zimmermann, T.J.; Kaiser, M.; Waldmann, H. Principles, implementation, and application of biology-oriented synthesis (BIOS). Biol. Chem. 2010, 391, 491–497. [Google Scholar]

- Kombarov, R.; Altieri, A.; Genis, D.; Kirpichenok, M.; Kochubey, V.; Rakitina, N.; Titarenko, Z. BioCores: identification of a drug/natural product-based privileged structural motif for small-molecule lead discovery. Mol. Divers. 2010, 14, 193–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wender, P.A.; Verma, V.A.; Paxton, T.J.; Pillow, T.H. Function-oriented synthesis, step economy, and drug design. Acc. Chem. Res. 2008, 41, 40–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, R.M.; Danishefsky, S.J. Small molecule natural products in the discovery of therapeutic agents: the synthesis connection. J. Org. Chem. 2006, 71, 8329–8351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newman, D.J.; Cragg, G.M.; Snader, K.M. Natural products as sources of new drugs over the period 1981-2002. J. Nat. Prod. 2003, 66, 1022–1037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harvey, A.L. Natural products in drug discovery. Drug Discov. Today 2008, 13, 894–901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lovering, F.; Bikker, J.; Humblet, C. Escape from flatland: increasing saturation as an approach to improving clinical success. J. Med. Chem. 2009, 52, 6752–6756. [Google Scholar]

- Ortholand, J.Y.; Ganesan, A. Natural products and combinatorial chemistry: back to the future. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 2004, 8, 271–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feher, M.; Schmidt, J.M. Property distributions: differences between drugs, natural products, and molecules from combinatorial chemistry. J. Chem. Inf. Comput. Sci. 2003, 43, 218–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burke, M.D.; Schreiber, S.L. A planning strategy for diversity-oriented synthesis. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2004, 43, 46–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spandl, R.J.; Bender, A.; Spring, D.R. Diversity-oriented synthesis; a spectrum of approaches and results. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2008, 6, 1149–1158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sauer, W.H.; Schwarz, M.K. Molecular shape diversity of combinatorial libraries: a prerequisite for broad bioactivity. J. Chem. Inf. Comput. Sci. 2003, 43, 987–1003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Welsch, M.E.; Snyder, S.A.; Stockwell, B.R. Privileged scaffolds for library design and drug discovery. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 2010, 14, 347–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Wolf, S.; Bista, M.; Meireles, L.; Camacho, C.; Holak, T.A.; Domling, A. 1,4-Thienodiazepine-2,5-diones via MCR (I): synthesis, virtual space and p53-Mdm2 activity. Chem. Biol. Drug Des. 2010, 76, 116–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitty, A.; Kumaravel, G. Between a rock and a hard place? Nat. Chem. Biol. 2006, 2, 112–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kar, G.; Gursoy, A.; Keskin, O. Human cancer protein-protein interaction network: A structural perspective. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2009, 5, e1000601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; Zhao, Z. A comparative study of cancer proteins in the human protein-protein interaction network. BMC Genomics 2010, 11 (Suppl. 3), S5. [Google Scholar]

- Vassilev, L.T.; Vu, B.T.; Graves, B.; Carvajal, D.; Podlaski, F.; Filipovic, Z.; Kong, N.; Kammlott, U.; Lukacs, C.; Klein, C.; Fotouhi, N.; Liu, E.A. In vivo activation of the p53 pathway by small-molecule antagonists of MDM2. Science 2004, 303, 844–848. [Google Scholar]

- Tovar, C.; Rosinski, J.; Filipovic, Z.; Higgins, B.; Kolinsky, K.; Hilton, H.; Zhao, X.; Vu, B.T.; Qing, W.; Packman, K.; Myklebost, O.; Heimbrook, D.C.; Vassilev, L.T. Small-molecule MDM2 antagonists reveal aberrant p53 signaling in cancer: implications for therapy. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2006, 103, 1888–1893. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, W.; Konopleva, M.; Burks, J.K.; Dywer, K.C.; Schober, W.D.; Yang, J.Y.; McQueen, T.J.; Hung, M.C.; Andreeff, M. Blockade of mitogen-activated protein kinase/extracellular signal-regulated kinase kinase and murine double minute synergistically induces Apoptosis in acute myeloid leukemia via BH3-only proteins Puma and Bim. Cancer Res. 2010, 70, 2424–2434. [Google Scholar]

- Sonnemann, J.; Palani, C.D.; Wittig, S.; Becker, S.; Eichhorn, F.; Voigt, A.; Beck, J.F. Anticancer effects of the p53 activator nutlin-3 in Ewing's sarcoma cells. Eur. J. Cancer 2011, 47, 1432–1441. [Google Scholar]

- Petros, A.M.; Huth, J.R.; Oost, T.; Park, C.M.; Ding, H.; Wang, X.; Zhang, H.; Nimmer, P.; Mendoza, R.; Sun, C.; et al. Discovery of a potent and selective Bcl-2 inhibitor using SAR by NMR. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2010, 20, 6587–6591. [Google Scholar]

- Ackler, S.; Mitten, M.J.; Foster, K.; Oleksijew, A.; Refici, M.; Tahir, S.K.; Xiao, Y.; Tse, C.; Frost, D.J.; Fesik, S.W.; et al. The Bcl-2 inhibitor ABT-263 enhances the response of multiple chemotherapeutic regimens in hematologic tumors in vivo. Cancer Chemother. Pharmacol. 2010, 66, 869–880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oltersdorf, T.; Elmore, S.W.; Shoemaker, A.R.; Armstrong, R.C.; Augeri, D.J.; Belli, B.A.; Bruncko, M.; Deckwerth, T.L.; Dinges, J.; Hajduk, P.J.; et al. An inhibitor of Bcl-2 family proteins induces regression of solid tumours. Nature 2005, 435, 677–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ezzoukhry, Z.; Louandre, C.; Francois, C.; Saidak, Z.; Godin, C.; Maziere, J.C.; Galmiche, A. The BH3 mimetic ABT-737 Reveals the Dynamic Regulation of BAD, a Pro-apoptotic Protein of the BCL2 family, by BCL-XL. Mol. Pharmacol. 2011, 79, 997–1004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, W.H.; O'Connor, O.A.; Czuczman, M.S.; LaCasce, A.S.; Gerecitano, J.F.; Leonard, J.P.; Tulpule, A.; Dunleavy, K.; Xiong, H.; Chiu, Y.L.; et al. Navitoclax, a targeted high-affinity inhibitor of BCL-2, in lymphoid malignancies: A phase 1 dose-escalation study of safety, pharmacokinetics, pharmacodynamics, and antitumour activity. Lancet Oncol. 2011, 11, 1149–1159. [Google Scholar]

- Secchiero, P.; Bosco, R.; Celeghini, C.; Zauli, G. Recent advances in the therapeutic perspectives of nutlin-3. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2011, 17, 569–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arkin, M.R.; Wells, J.A. Small-molecule inhibitors of protein-protein interactions: progressing towards the dream. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2004, 3, 301–317. [Google Scholar]

- Arkin, M.R.; Randal, M.; DeLano, W.L.; Hyde, J.; Luong, T.N.; Oslob, J.D.; Raphael, D.R.; Taylor, L.; Wang, J.; McDowell, R.S.; Wells, J.A.; Braisted, A.C. Binding of small molecules to an adaptive protein-protein interface. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2003, 100, 1603–1608. [Google Scholar]

- Meireles, L.M.; Mustata, G. Discovery of modulators of protein-protein interactions: current approaches and limitations. Curr. Top. Med. Chem. 2011, 11, 248–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, J.M.; Tsou, L.K.; Hamilton, A.D. Synthetic non-peptide mimetics of alpha-helices. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2007, 36, 326–334. [Google Scholar]

- Cummings, C.G.; Hamilton, A.D. Disrupting protein-protein interactions with non-peptidic, small molecule alpha-helix mimetics. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 2010, 14, 341–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vazquez, A.; Bond, E.E.; Levine, A.J.; Bond, G.L. The genetics of the p53 pathway, apoptosis and cancer therapy. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2008, 7, 979–987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vassilev, L.T. MDM2 inhibitors for cancer therapy. Trends Mol. Med. 2007, 13, 23–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, J.A. Design of protein-protein interaction inhibitors based on protein epitope mimetics. ChemBioChem 2009, 10, 971–973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domling, A. Small molecular weight protein-protein interaction antagonists: An insurmountable challenge? Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 2008, 12, 281–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- eMolecules, Inc. Available online: http://www.emolecules.com/ accessed on 8 January 2011.

- Adams, J.M.; Cory, S. The Bcl-2 protein family: Arbiters of cell survival. Science 1998, 281, 1322–1326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reed, J.C. Bcl-2 family proteins: Strategies for overcoming chemoresistance in cancer. Adv. Pharmacol. 1997, 41, 501–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chao, D.T.; Korsmeyer, S.J. BCL-2 family: Regulators of cell death. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 1998, 16, 395–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minn, A.J.; Swain, R.E.; Ma, A.; Thompson, C.B. Recent progress on the regulation of apoptosis by Bcl-2 family members. Adv. Immunol. 1998, 70, 245–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Storey, S. Targeting apoptosis: Selected anticancer strategies. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2008, 7, 971–972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sattler, M.; Liang, H.; Nettesheim, D.; Meadows, R.P.; Harlan, J.E.; Eberstadt, M.; Yoon, H.S.; Shuker, S.B.; Chang, B.S.; Minn, A.J.; et al. Structure of Bcl-xL-Bak peptide complex: Recognition between regulators of apoptosis. Science 1997, 275, 983–986. [Google Scholar]

- Petros, A.M.; Nettesheim, D.G.; Wang, Y.; Olejniczak, E.T.; Meadows, R.P.; Mack, J.; Swift, K.; Matayoshi, E.D.; Zhang, H.; Thompson, C.B.; Fesik, S.W. Rationale for Bcl-xL/Bad peptide complex formation from structure, mutagenesis, and biophysical studies. Protein Sci. 2000, 9, 2528–2534. [Google Scholar]

- Day, C.L.; Chen, L.; Richardson, S.J.; Harrison, P.J.; Huang, D.C.; Hinds, M.G. Solution structure of prosurvival Mcl-1 and characterization of its binding by proapoptotic BH3-only ligands. J. Biol. Chem. 2005, 280, 4738–4744. [Google Scholar]

- Becattini, B.; Kitada, S.; Leone, M.; Monosov, E.; Chandler, S.; Zhai, D.; Kipps, T.J.; Reed, J.C.; Pellecchia, M. Rational design and real time, in-cell detection of the proapoptotic activity of a novel compound targeting Bcl-X(L). Chem. Biol. 2004, 11, 389–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcaurelle, L.A.; Johannes, C.; Yohannes, D.; Tillotson, B.P.; Mann, D. Diversity-oriented synthesis of a cytisine-inspired pyridone library leading to the discovery of novel inhibitors of Bcl-2. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2009, 19, 2500–2503. [Google Scholar]

- Marcaurelle, L.A.; Johannes, C.W. Application of natural product-inspired diversity-oriented synthesis to drug discovery. Prog. Drug Res. 2008, 66, 187–216. [Google Scholar]

- Castro, C. Compounds and methods for inhibiting the interaction of BCL proteins with binding partners. US Patent 7,851,637, 14 December 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Di Micco, S.; Vitale, R.; Pellecchia, M.; Rega, M.F.; Riva, R.; Basso, A.; Bifulco, G. Identification of lead compounds as antagonists of protein Bcl-xL with a diversity-oriented multidisciplinary approach. J. Med. Chem. 2009, 52, 7856–7867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bange, J.; Zwick, E.; Ullrich, A. Molecular targets for breast cancer therapy and prevention. Nat. Med. 2001, 7, 548–552. [Google Scholar]

- Escot, C.; Theillet, C.; Lidereau, R.; Spyratos, F.; Champeme, M.H.; Gest, J.; Callahan, R. Genetic alteration of the c-myc protooncogene (MYC) in human primary breast carcinomas. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1986, 83, 4834–4838. [Google Scholar]

- Liao, D.J.; Dickson, R.B. c-Myc in breast cancer. Endocr. Relat. Cancer 2000, 7, 143–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Little, C.D.; Nau, M.M.; Carney, D.N.; Gazdar, A.F.; Minna, J.D. Amplification and expression of the c-myc oncogene in human lung cancer cell lines. Nature 1983, 306, 194–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erisman, M.D.; Rothberg, P.G.; Diehl, R.E.; Morse, C.C.; Spandorfer, J.M.; Astrin, S.M. Deregulation of c-myc gene expression in human colon carcinoma is not accompanied by amplification or rearrangement of the gene. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1985, 5, 1969–1976. [Google Scholar]

- He, T.C.; Sparks, A.B.; Rago, C.; Hermeking, H.; Zawel, L.; da Costa, L.T.; Morin, P.J.; Vogelstein, B.; Kinzler, K.W. Identification of c-MYC as a target of the APC pathway. Science 1998, 281, 1509–1512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavlidis, N.; Briassoulis, E.; Bai, M.; Fountzilas, G.; Agnantis, N. Overexpression of C-myc, Ras and C-erbB-2 oncoproteins in carcinoma of unknown primary origin. Anticancer Res. 1995, 15, 2563–2567. [Google Scholar]

- Berg, T.; Cohen, S.B.; Desharnais, J.; Sonderegger, C.; Maslyar, D.J.; Goldberg, J.; Boger, D.L.; Vogt, P.K. Small-molecule antagonists of Myc/Max dimerization inhibit Myc-induced transformation of chicken embryo fibroblasts. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2002, 99, 3830–3835. [Google Scholar]

- Boger, D.L.; Lee, J.K.; Goldberg, J.; Jin, Q. Two comparisons of the performance of positional scanning and deletion synthesis for the identification of active constituents in mixture combinatorial libraries. J. Org. Chem. 2000, 65, 1467–1474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boger, D.L.; Desharnais, J.; Capps, K. Solution-phase combinatorial libraries: modulating cellular signaling by targeting protein-protein or protein-DNA interactions. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2003, 42, 4138–4176. [Google Scholar]

- Yin, X.; Giap, C.; Lazo, J.S.; Prochownik, E.V. Low molecular weight inhibitors of Myc-Max interaction and function. Oncogene 2003, 22, 6151–6159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

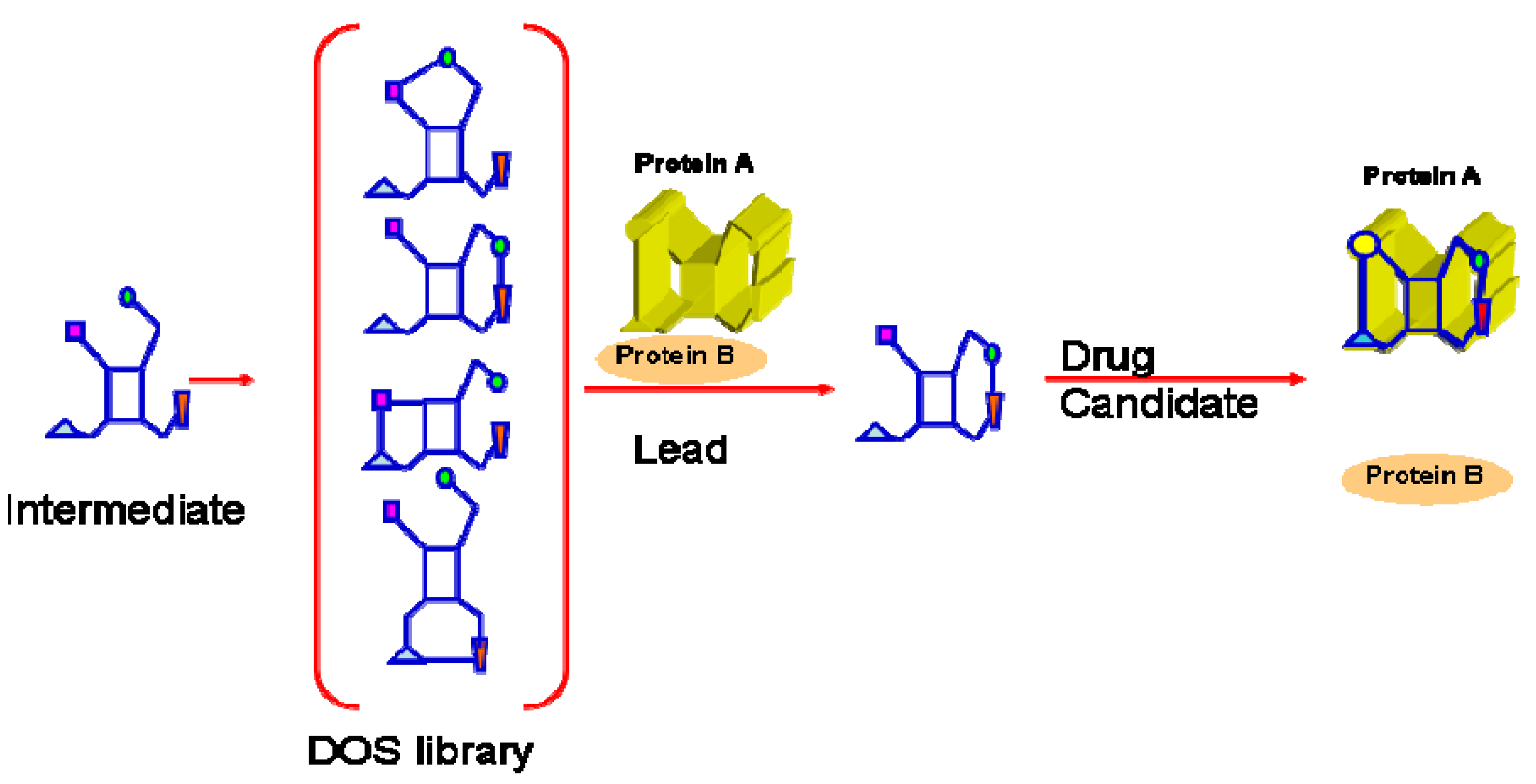

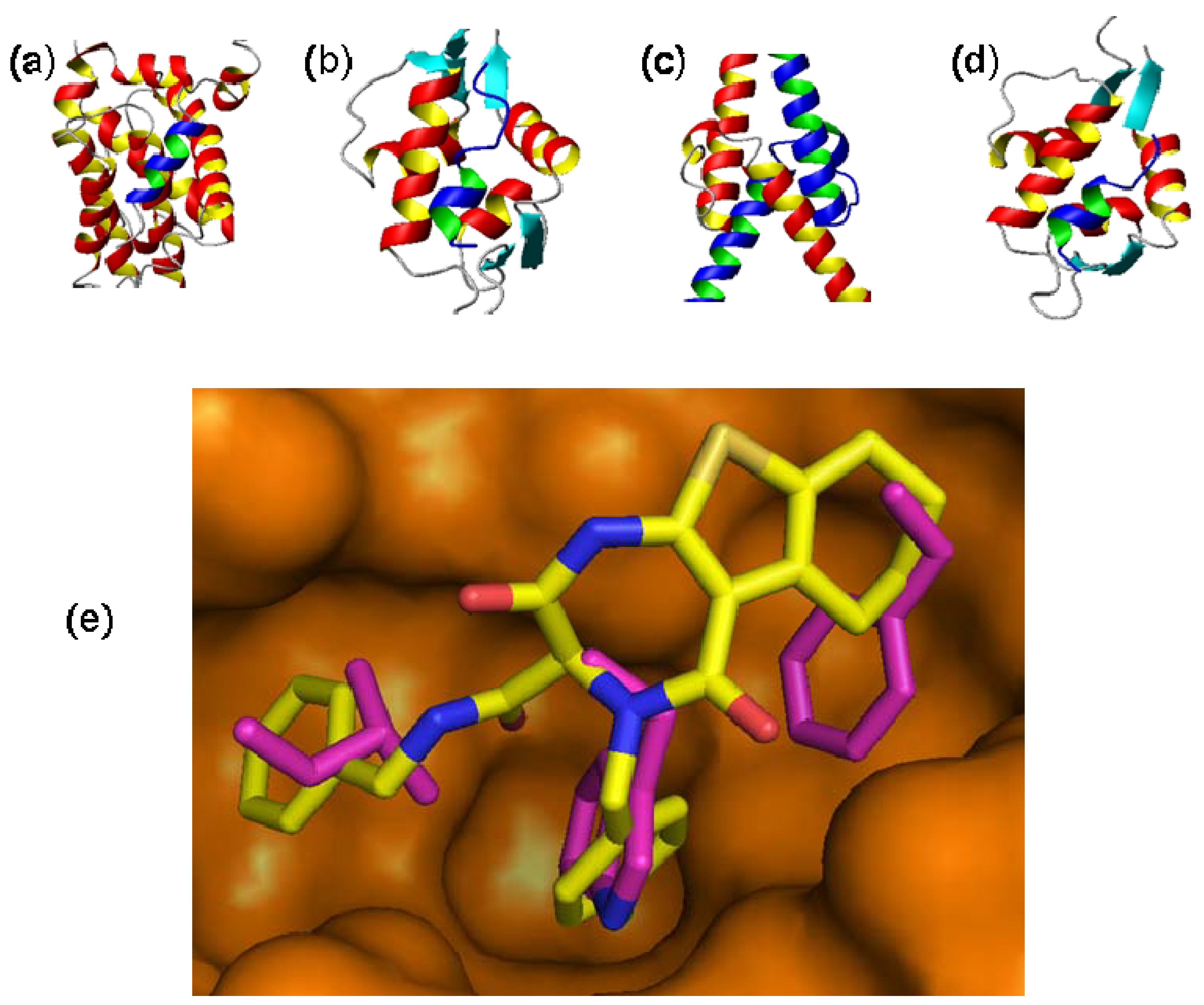

- Lee, J.H.; Zhang, Q.; Jo, S.; Chai, S.C.; Oh, M.; Im, W.; Lu, H.; Lim, H.S. Novel Pyrrolopyrimidine-Based alpha-Helix Mimetics: Cell-Permeable Inhibitors of Protein-Protein Interactions. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011, 133, 676–679. [Google Scholar]

- Laurie, N.A.; Donovan, S.L.; Shih, C.S.; Zhang, J.; Mills, N.; Fuller, C.; Teunisse, A.; Lam, S.; Ramos, Y.; Mohan, A.; et al. Inactivation of the p53 pathway in retinoblastoma. Nature 2006, 444, 61–66. [Google Scholar]

- Toledo, F.; Wahl, G.M. Regulating the p53 pathway: in vitro hypotheses, in vivo veritas. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2006, 6, 909–923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marine, J.C.; Dyer, M.A.; Jochemsen, A.G. MDMX: from bench to bedside. J. Cell. Sci. 2007, 120, 371–378. [Google Scholar]

- McGovern, S.L.; Helfand, B.T.; Feng, B.; Shoichet, B.K. A specific mechanism of nonspecific inhibition. J. Med. Chem. 2003, 46, 4265–4272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seidler, J.; McGovern, S.L.; Doman, T.N.; Shoichet, B.K. Identification and prediction of promiscuous aggregating inhibitors among known drugs. J. Med. Chem. 2003, 46, 4477–4486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huth, J.R.; Mendoza, R.; Olejniczak, E.T.; Johnson, R.W.; Cothron, D.A.; Liu, Y.; Lerner, C.G.; Chen, J.; Hajduk, P.J. ALARM NMR: A rapid and robust experimental method to detect reactive false positives in biochemical screens. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005, 127, 217–224. [Google Scholar]

- Roche, O.; Schneider, P.; Zuegge, J.; Guba, W.; Kansy, M.; Alanine, A.; Bleicher, K.; Danel, F.; Gutknecht, E.M.; Rogers-Evans, M.; et al. Development of a virtual screening method for identification of "frequent hitters" in compound libraries. J. Med. Chem. 2002, 45, 137–142. [Google Scholar]

- Rishton, G.M. Nonleadlikeness and leadlikeness in biochemical screening. Drug Discov. Today 2003, 8, 86–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ANCHOR. Available online: http://structure.pitt.edu/anchor/ accessed on 8 January 2011.

- AnchorQuery. Available online: http://anchorquery.ccbb.pitt.edu/ accessed on 8 January 2011.

© 2011 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution license ( http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/).

Share and Cite

Tzakos, A.G.; Fokas, D.; Johannes, C.; Moussis, V.; Hatzimichael, E.; Briasoulis, E. Targeting Oncogenic Protein-Protein Interactions by Diversity Oriented Synthesis and Combinatorial Chemistry Approaches. Molecules 2011, 16, 4408-4427. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules16064408

Tzakos AG, Fokas D, Johannes C, Moussis V, Hatzimichael E, Briasoulis E. Targeting Oncogenic Protein-Protein Interactions by Diversity Oriented Synthesis and Combinatorial Chemistry Approaches. Molecules. 2011; 16(6):4408-4427. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules16064408

Chicago/Turabian StyleTzakos, Andreas G., Demosthenes Fokas, Charlie Johannes, Vassilios Moussis, Eleftheria Hatzimichael, and Evangelos Briasoulis. 2011. "Targeting Oncogenic Protein-Protein Interactions by Diversity Oriented Synthesis and Combinatorial Chemistry Approaches" Molecules 16, no. 6: 4408-4427. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules16064408

APA StyleTzakos, A. G., Fokas, D., Johannes, C., Moussis, V., Hatzimichael, E., & Briasoulis, E. (2011). Targeting Oncogenic Protein-Protein Interactions by Diversity Oriented Synthesis and Combinatorial Chemistry Approaches. Molecules, 16(6), 4408-4427. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules16064408