3. Results. 1: The Tie-Up from the Male Viewpoint

3.1. The Preparation of the Male Tie-Up (M-TU)

The Tie-Up (TU) denotes an individual psycho-biological link that can be formed in any relationship with an opposite-sex subject who, in some way, also unknowingly, has induced it in the tying-up subject. The Male Tie-Up (M-TU), in particular, is a link whose nature is mental and emotional, even if the mental seduction combines with the physical one. A TU cannot occur if the potential partner has not successfully passed a specific compatibility test.

The male lead character of My Ajussi, Park Dong Hoon (interpreted by Lee Sun Kyun, the lead male actor of Parasite, the first Korean movie to win the Palme d’Or at Cannes and the Oscar Prize for Best Film), is an engineer in a big Korean company who is currently stuck at a dead end of his career. His process of tying-up to the young employee Lee Ji An starts in the very first scene of the drama, when no character has been introduced yet to the viewer. The camera wanders across the desks and the computers of an open space work environment where everybody is intent in their job. Suddenly, the flight of an intruding bug breaks their focus. Everybody gets instantly alarmed: a woman screams, all men stand up, and everybody’s attention is pointed at the flying insect. The viewer is probably already thinking of a giant hornet or a raging wasp, ready to sting. However, that is not the case. It is a simple, nice, little ladybug that lands on the arm of the only person who looks indifferent to the general turmoil: the frowning, taciturn employee Lee Ji An. That Park Dong Hoon is the male lead character of the story becomes instantly apparent, as he is the only one stepping forward to protect that little being, declaring with a single posture of the body his kind nature, and his respect for the beauty and fragility of existence. His friends warmly describe him as a nerd, a great professional but socially shy and reserved. He gently tries to pick the bug, but in the nick of time he is anticipated by Lee Ji Han, who with a sudden blow has already splattered it, with a cruelty that leaves everybody speechless. She is a 21-years-old temporary employee silently attending humble tasks such as delivering the mail, making photocopies, archiving bills and receipts. An unnoticeable person, who quietly stays in the background. However, that unexpected blow, merciless and unmotivated, sparks Park Dong Hoon’s curiosity.

One wouldn’t think that an apparently innocuous insect such as a ladybug, with its tender and fragile appearance, is in fact, surprisingly, a fierce predator that is able to capture a hundred aphids a day, sucking them up until their totally emptied, undigestible exoskeleton is all that remains. Lee Ji An is not that different from a ladybug: tiny, young, with a fragile appearance, she moves across her workplace like an intruder, not unlike an insignificant bug—she is invisible but, if noticed, her avoidant behavior makes others uncomfortable. Nobody would suspect that such a young girl would have a surprisingly devilish, cunning mind; nobody would imagine how insensitive and ruthless she may be. What attracts Park Dong Hoon is not the cruelty of her gesture, but the contrast with the appearance of the person who made it. How come that such a young, delicate, and gently looking girl who should exhale grace and joie de vivre is instead so lacking any compassion for life?

A Tie-Up process always begins with a compatibility test, which for males is a check of psycho-emotional compatibility. The test is automatic and unconscious, and it is easily carried out in the absence of a preexisting TU in the subject that launches it. The pre-existence of a TU is instead blocking the launch of the test, by making it irrelevant, the more so the more the already existing TU is strong and deeply rooted. Park Dong Hoon is in his 40s, and he is married to a beautiful and sophisticated woman, professionally well-accomplished. The couple has a teenager son who studies abroad and is therefore absent from their daily life. He is full of care and ready to support his wife in housekeeping chores—an attitude that in a deeply gender-unequal society such as the Korean one signals consideration and attachment to his partner. Nevertheless, they appear as a cold couple, which finds it hard to communicate. In view of the story’s later unfolding, we can then conclude that despite they are both tied-up, their Tie-Up Cycle is struggling, and is fed more by frustrations than by rewards: a situation that, if dragging along, may cause a dangerous undoing of the TUs themselves.

When Park Dong Hoon notices Lee Ji An, he is not driven by physical attraction, but rather by the fact that his weakened TU leaves space for a new Test of Psychological Compatibility. This seems confirmed by the fact that Lee Ji An does nothing to be sexually attractive. It is hard to tell whether she is attractive at all, as she is always wearing bleak male jackets, has no make-up and a messy, carelessly tied hair. Park Dong Hoon starts observing her and realizes that her thinness and paleness conceal malnutrition—she steals the packets of a freeze-dried beverage that are freely available for employees, as if she had nothing else to eat. He is also impressed by her shabby sneaker shoes, that she wears without socks, totally inadequate for the freezing Korean winter. Her skin is moreover often swollen, and under the sunglasses that she always wears also indoors, making her look so odd and grim, he notices some bruises.

Fragility and toughness, impassibility and endurance, misery and mystery: these are the contrasting signals that capture the interest of Park Dong Hoon and pull him to venture into a first, minimal approach, a few words sounding almost like a provocation, just to get to know something more: “Isn’t it a bit too cruel to kill a ladybug? What’s the worst thing that you’ve killed?”, and her, without even looking at him, answers: “A person”. Obviously, he doesn’t believe her: “Sorry for trying to make small talk”. What he does not know yet about her is that every answer of hers is utterly sincere, that she never lies, in any circumstance. She is desperately clinging to truth at all costs, even against her interest. We will soon discover how her deeply ingrained cynicism stems from the crude, hidden truth that has shaped her entire life, and truth then becomes what justifies her miserable existence. It is true, she has killed a man, and it is such truth, which she cannot escape, that molds her destiny. Lee Ji An is the predator ladybug who exploits any opportunity to suck up life from her victims in order to survive, to pay back an old debt with loan sharks made by a mother who abandoned her when she was still a child.

The first meaningful interaction between the two has therefore a tragic nature. She robs him, snatching away a considerable sum of money from a bribe that was erroneously delivered to Park Dong Hoon. It was intended for a top manager who was being targeted by a rival willing to frame him with an ad hoc allegation of corruption. Park Dong Hoon cannot prove his innocence without giving back that money he no longer has with him. Lee Ji An, in turn, being unable to use the stolen money to extinguish the debt that enslaves her, brings it back, seeing to it that the sum is found in a wastepaper basket at the office. The company’s management will conclude that Park Dong Hoon spontaneously gave up the stolen money before being caught. Again, when he asks her: “Where’s that money?”, she tells the truth: “I threw it away… in the garbage can”. A truth, once again, difficult to accept. Still under shock for having been scammed first and then saved by the same person, Park Dong Hoon lets her get closer to him, out of curiosity and possibly even fascination for such an enigmatic personality, whereas she is already machinating a different plan to strike him again to earn the money she needs through a different tactic.

3.2. Start of the Psychological Compatibility Test

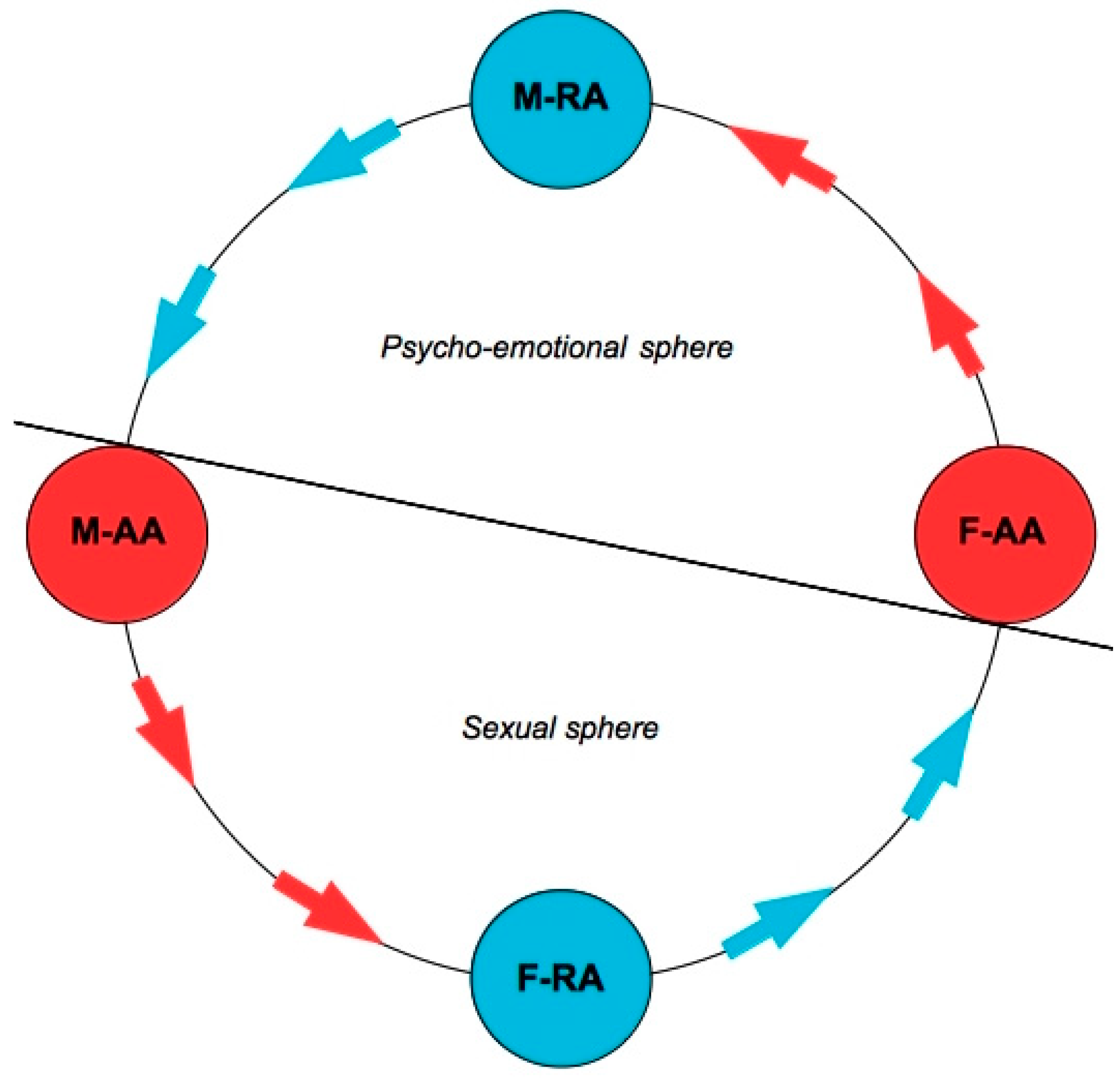

The Psychological Compatibility Test is carried out by males and its purpose is to check the psychological compatibility of the potential female partner, as well as the right level of complementarity in jointly pursuing couple goals. In evolutionary terms, psychological compatibility guarantees the benefits from joint offspring rearing. For both sexes, actual compatibility with a potential partner is tested by a specific psychological structure called the Receptive Area (RA), whose name indicates its passive mode of functioning. When the RA gets effectively stimulated, it becomes susceptible to the TU, that is, it ties-up to the opposite-sex partner with the appropriate characteristics, which has provided, intentionally or not, the successful stimulation. The link with the partner is further reinforced by any subsequent, successful stimulation of the RA. In the absence of effective stimulation, the RA remains ‘turned off’, that is, unnoticed at a conscious level. Conversely, if the stimulation is successful, the RA is turned on at a peak level as the TU is formed and further consolidated. The sphere of operation of the RA depends on the subject’s sex, so that a male RA (M-RA) will have different features than a female RA (F-RA).

A certain level of arousal of interest, even just a curiosity, is generally how the male Psychological Compatibility Test gets started. What appears as a simple curiosity is in fact an ideal opportunity to indulge in an exploratory attempt at knowing—and sometimes even at figuring out—the other, and such an attempt inevitably implies some form of assessment, and therefore a test. Park Dong Hoon starts to furtively observe the mysterious, gloomy Lee Ji An, and by so doing he unknowingly launches his test. His interest is driven by a sort of sympathy and sensitivity toward suffering. To his collaborators—the team of engineers he directs, whose task is checking the structural stability of buildings that need certification—he says: “Don’t you feel sorry for her?”, referring to Lee Ji An; “I feel bad for people who look tense. It gives you an idea about their past. Kids grow up quickly when they’re hurt. I can see it. That’s why I feel bad for her. I’m scared to know what happened to her”. This sense of pity sounds surprisingly remote from a possible infatuation for someone, but the example shows clearly how unbeknownst the psychological approaching process caused by a successful male test may be. Each man has his own implicit criteria he uses to test the compatibility of potential partners, which depends upon a complex mix of variables, mainly determined by his specific psychological traits and personality, together with his level of energy, his social context, and his life history, among others. Let’s try then to understand what are Park Dong Hoon’s psychological priorities, on the basis of which Lee Ji An gets tested.

As the story unfolds, we clearly realize that the test on the female lead character has been successful, despite that Park Dong Hoon tries to conceal it. The curious thing is that the reasons why he opens up to her are initially ill-founded, a misunderstanding, because he believes that the young woman is on his side and has helped him, accepting his younger brother’s view on the stolen money affair: “She likes you, Big Bro. She didn’t steal it to have it for herself. She stole it to save you, and then threw it away!”. However, she in fact despises him, and has placed a trojan horse in his cellphone to be able to record every instant of his phone calls: the words he says, those he listens to, even the environmental sounds that the phone manages to capture. Her goal is to find a weak spot to knock him down. If she will manage to find a way to have him fired, she will receive ‘clean’, that is, no longer stolen money from the careerist Do Joon Young, the company’s CEO, who secretly wants to humiliate Park Dong Hoon at all costs due to a hard-wired inferiority complex dating back to their college years. His envy, later upscaled into hatred, and further fueled by the company’s power games, spills over to Park Dong Hoon’s private life. The rival, for whom boycotting him professionally is not enough for a revenge, manages to become his wife’s secret lover.

A successful compatibility test does not necessarily imply that a TU will result. It simply marks the turning on of the Receptive Area (M-RA or F-RA, according to cases). For the TU to form, the arousal of the RA must cross a certain individual threshold. This may only happen in the absence of a pre-existing TU. Park Dong Hoon experiences the dissolution of his previous TU as he discovers that his wife has been cheating on him. The scenes that show Park Dong Hoon’s inner torment, his excruciating sorrow, are a double proof: of the previous existence of that TU, and of its sudden disintegration. From now on, a new TU with Lee Ji An becomes both possible and likely.

To search for the precise moment in which Park Dong Hoon gets tied-up to Lee Ji An, we need, first of all, to realize why the young woman has successfully passed the test, and what has been its object. An important clue is provided by Park Dong Hoon’s wife and her cheating on him—the fruit of her inability to understand her husband, and specifically his need to remain close to his family of origin: his mother, his brothers, his group of friends with whom to play soccer and drink, and meet together in their old pub. Park Dong Hoon’s wife, possibly because of affective insecurity, enters into a competition with her husband’s social world, from which she feels, and wants to be, excluded. In such competition, she fears to come second, and therefore believes not to be loved by him as she would deserve. She accuses him to prefer his friends to her and to leave her alone in a house she now hates as a materialization of her abandonment complex. In fact, Park Dong Hoon’s circle of friends is pretty open to women: they cheerfully welcome his younger brother’s girlfriend, his older brother’s ex-wife, and his best friend’s ex-girlfriend, all women who not only do not feel refused, but become part of a sort of enlarged family which supports and protects its members—to the extent that the women will remain in the group also after having broken with their group-affiliated partners. And also Lee Ji An will be welcomed by the group.

3.3. End of the Tie-Up Cycle as a Consequence of the Dissolution of the TU

When both partners of a potential couple get tied-up to one another, thus creating a Double Tie-Up (D-TU), the basic condition that is necessary to launch a lasting Tie-Up Cycle (TU-C) is met. The TU-C is a model of the iterative dynamics of the flow of communication between the two partners that form a couple. Only when the flows of communication generate sexual and emotional payoffs under the form of rewards, the TU-C becomes auto-poietic and able to persist in time. When the flow of communication mainly delivers frustrations, one or both TUs will be damaged, the TU-C will extinguish itself and the couple will be undermined.

The exclusive relationship that Park Dong Hoon’s wife reclaims for her derives much more from a self-referential idea of love than from a real ability to resonate with her partner’s personality and feelings. This kind of blindness may seriously compromise the smooth functioning of a TU-C. Once more Park Dong Hoon, when he tested the beautiful woman who would have then become his wife, must have misunderstood the nature of her interest for him, failing to acknowledge her affective insecurity, which now becomes apparent through her unmotivated jealousy. Her cheating is double-edged: sexual and psychological at the same time. What is worst is that she does not limit herself to cheat on him physically, in her quest for that privileged, exclusive love she feels has been denied to her, but does it with his husband’s worst enemy, revealing to be prepared to destroy him at every level, in a sort of spiteful revenge. When he finally vents his sorrow to her, he asks: “How could you do that with him? How could you do that?”, and again: “As soon as you cheated on me with that bastard…you pronounced me dead. Because you thought it was okay for me to be treated that way. That was you saying that I’m worthless and that I should just die”.

Park Dong Hoon’s misunderstandings, with his wife first and then with Lee Ji An, give us an important clue as to the psychological aspect he searches for in a woman. For him, the primary condition is that she can stay on his side and is therefore willing to support him in his life choices which, given his independent, uncompromising way of thinking, are far from easy and conventional. The reason behind the dissolution of his TU then becomes evident: with that kind of cheating, his wife unequivocally proves that she is no longer on her husband’s side. She even accepts that her lover strips him of his job in the company he loyally served for so long. She is hesitant in fact, doubting that a layoff followed by a divorce would be a bit too much, but she eventually justifies herself by concluding that “A mechanical engineer will have no problem to get by, even if he’s fired from his company”. There’s no need to comment; what needs to be remarked is rather that her F-TU is paradoxically still standing, and her behavior is futile, the blind capriciousness of someone who is upset for not having gotten the upper hand in a dispute for attention. Even her lover realizes this when he tells her: “You must still really love Senior Park Dong Hoon a lot”, and staring at her perplexed gaze as she still ignores this of herself, he goes on: “It just sounds like that. It pisses me off”.

She will remain the only one to be tied-up in a couple whose TU-C has become nonexistent. This is the nemesis she must accept since the very moment she eventually realizes her mistake. Additionally, the fact that Park Dong Hoon, out of his moral integrity and of his love for their son, decides to formally maintain their couple relationship and avoids cheating on her in retaliation, does not ease at all the harrowing, sorrowful psychological condition of his wife. A compromised TU may be recovered with some effort, by rebooting the rewards that once fed it, but its dissolution is irreversible when the very conditions that led to the success of the compatibility test are basically denied. Remaining tied-up outside of a TU-C means failing to obtain the rewards that the TU needs and being bound to suffer a slow agony up to its final disappearance.

3.4. The Individual Nature of the M-RA

The male Receptive Area (M-RA) has a psycho-emotional nature. Males are seduced in their imaginary and feelings and get tied to an opposite-sex subject on mental rather than physical grounds. A M-RA will then reflect the psycho-emotional imaginary of the male subject to whom it belongs.

Beyond ‘being on his side’, there is another indispensable ingredient that is needed to cause Park Dong Hoon’s compatibility test to be successfully passed: that the woman being tested demonstrates elective affinities in terms of moral standing and values. He wants to have someone next to him that he can appreciate and esteem. This should be generically true for anybody. Here, however, we have a rather extreme case: a derelict young woman, without a family (except for a severely disabled granny), chased by loan sharks and callously scamming and blackmailing people, and who has already killed a man in her young age. How could her be esteemed by an irreprehensible middle-aged professional in a society with deep Confucian roots? But Park Dong Hoon’s attitude towards Lee Ji An shows the extent to which the male lead character of this drama eschews commonsense and is scarcely interested in the standards of social respectability, being instead autonomous in his decisions and self-aware of his moral choices. Lee Ji An successfully passes this part of the test when Park Dong Hoon realizes the nature of the relationship that links Lee Ji An to her granny: an elderly woman, deaf and mute, unable to walk, who entirely depends on the uncompromising effort of her miserable nephew for every living need, both bodily and psychological. Park Dong Hoon witnesses her stealing a shopping cart in the supermarket of the neighborhood where they both live, which she will use to transport her granny at night to an open place from where she would best enjoy the sight of the full moon, out of the maze of narrow, steep passageways through the tenement houses tucked along the hill, where they live in a dark, sleazy rented studio flat. When Park Dong Hoon—after having joined the difficult descent with the granny in the cart and the even harder ascent back home giving the granny a piggyback—says to Lee Ji An: “You’re a good person”, something nobody ever told her before, he treats her as a peer. She has earned his respect, one that reflects, more than physical appearance, her dedication, effort, intrinsic worth, her capacity to stay close to her loved ones despite all difficulties. Many times, other employees complained about Lee Ji An with Park Dong Hoon, and when one of these asks whining: “Can’t we fire her and hire someone who’s nicer? It’s not like we ask for much, but she’s so cold whenever we ask for anything. I can’t even talk to her because she’s so scary”, he gravely replies: “She’s more respectful of her superiors than you are, at least. Don’t make me fire you”. Then, not unlike a Taoist sage would have it, he addresses the annoying employee: “There’s a person who is quiet, amicable, and friendly and yet doesn’t take care of anyone else. And then, there’s a person who may be bitchy and stoic… but always takes care of someone. So which of the two is the truly nice one?”

The last aspect, and maybe the most crucial for Park Dong Hoon’s test, is a sort of recognition that strips bare the most intimate part of his interior world. He realizes that the attraction he feels toward Lee Ji An moves from recognizing himself in the sorrow that the young woman has to endure. There is a sort of human misery that unites them, makes them alike in the toughness of the ordeals each of them has to go through to survive.

A peculiarity of all RAs, both male and female, is that they tend to remain concealed and to shy away. They are intimacy zones, at the edge of the unconscious, that need to be strictly protected. Any individual instinctually knows that publicly exposing their own RA would make them seriously vulnerable psychologically. For women, this sense of decency has a sexual nature due to the characteristics of their F-RA, whereas putting under the spotlight their psychological peculiarities would paradoxically reassure them and, in certain contexts, might become a real strength. For men, exactly the opposite holds as their M-RA has a psycho-emotional nature. A fitting example is offered by the girlfriend of Park Dong Hoon’s younger brother, a young actress who can’t act, who makes no mystery of what she thinks and feel, joyously and shamelessly sharing with all others her most personal thoughts, and, especially at the beginning, making all the men in the group feel totally embarrassed. At the opposite side of the spectrum there is Park Dong Hoon who has a hard time sharing his concerns—the ostracism he suffers in the workplace and her wife’s cheating on him—even with his beloved brothers.

The only person who is aware of the miserable condition Park Dong Hoon is in and that he is striving to conceal, especially to those closest to him, is none other than Lee Ji An. He tells his brother: “There’s someone … who knows a lot about me. And… I think I know a lot about her too”. He then adds: “I’m sad … that she knows who I am”. This is, metaphorically, an experience of nudity. To better understand this passage, let us think how it feels to be seen physically naked. In the absence of exhibitionism, this may be embarrassing and humiliating for both men and women, but for the latter the implications are different. When a woman, who does not make of her physical appearance a tool to pursue instrumental goals, manages to abandon herself to the intimate gaze of a man, this means that there is an attraction that links her to that man. In this case, the F-RA gets excited just because it is looked at. Something analogous happens to the M-RA in the psycho-emotional sphere. The border between irritation and pleasure is impalpable, and only depends upon the extent to which the other is liked and attractive, which in turn depends on sexual or psychological compatibility, according to cases.

The fact that Park Dong Hoon—despite being unaware that the young woman listens to his conversations—has realized that she is able to read deeply through him (“There’s someone…who knows a lot about me”) is an important check as far as the test is concerned and marks a crucial passage as he does not feel irritated by the intermission as much as he could. The sadness that he feels (“I’m sad … that she knows who I am”) is everything but irritation, it rather amounts to a feeling of inadequacy. The misery Park Dong Hoon is currently experiencing has something in common with the one Lee Ji An endures daily since she was a little girl—a misery made of exploitation, injustice, abuse, guilt, suffering, and loneliness. As Park Dong Hoon feels increasingly unable to face the many issues nagging him all along, he senses that maybe that young woman is the human being who more than anyone else goes through a similar kind of sorrow, and this is the reason why the two end up recognizing each other. There is a telling scene just before the midpoint of the drama, in episode 6, which literally represents the core of their relationship, and which resumes all these aspects in one situation: getting to know one so deeply to overcome any defensive barrier and to unveil all weaknesses and vulnerabilities, including blemish and guilt, and despite this ‘standing on their side’. This is the experience of the essence of a RA that feels seen in its nudity and discovers to be accepted simply for what it is, when all reservations fall down, critiques and reproaches disappear, and one realizes with wonder to be loved for real. This is the scene where it becomes clear that Lee Ji Han has successfully passed Park Dong Hoon’s test.

Park Dong Hoon is a witness of the abuse suffered by Lee Ji An on the workplace, by one of the members of his team. When he inquires about the reason of the man’s hostility towards her, it quickly comes up that he has a big grudge against her because Lee Ji An previously slapped him in public. The humiliation did not have consequences in terms of gossip because the slapping happened at the end of a company dinner when most people already had walked away, and the remaining ones were drunk. However, the scene nevertheless fueled the employee’s rage against Lee Ji An who showed so little respect toward a senior colleague. To solve the issue, Park Dong Hoon makes sure to meet with her alone, at the end of the workday, and addresses her asking for the reason behind her act: “How could you be so reckless as to slap someone?”, he scolds her whereas she remains silent. He goes on arguing that this kind of things only happen on the TV but should never happen in real life: “Why did you hit him? Did he insult you? Or hit you? I asked you why you hit him!”. Then, she answers with the usual, disarming sincerity: “Because he was insulting you”. Park Dong Hoon is left speechless, as she goes on: ”He was saying that if he were you, he would’ve quit already and that it’s difficult to work for a superior who’s being abused. And that this entire situation isn’t Do Joon Young’s fault… but the fault of the pitiful Manager Park”. Do Joon Young, as remarked earlier, is the CEO who is striving to have Park Dong Hoon fired and who has a secret affair with his wife. Now there is no misunderstanding any longer: Lee Ji An is really on his side.

One of the most interesting sides of the male lead character of this drama is his capacity to bounce back in moments of difficulty, to manage to keep his dignity intact despite the infamy that pours upon him, reaffirming his leadership even when the employees consider him a loser. He calls his team member on the phone and tells him he now knows why he was slapped, and when the other defends himself by claiming he was drunken and does not remember he said such things, Park Dong Hoon gets loud: “Don’t say you didn’t know, you bastard”. The other remains afflicted and speechless as Park Dong Hoon, still screaming, doubles down: “Say that you’re sorry. Say it ten times, right now”. The atonement ritual is carried out by the employee with conviction and relief, in the awareness to have received forgiveness for that petty act of disloyalty, as Park Dong Hoon closes the incident: “Let’s not be like this, okay? I don’t want you to cause me pain”. Lee Ji An is a witness to the call, staring at the pavement with her back leaning against a house wall, carefully listening. He turns to her and, still tense, tells her: “Everyone talks trash about everyone behind their backs. You think they won’t, just because you’re close? People aren’t so simple like that. I talk trash about people behind their back, too. It happens. Who cares? Why would you tell me? What did you expect me to do? This is so humiliating”. However, then he adds: “I am sorry. This is all my fault, and yet … —he pauses— … Thanks. For hitting him”. At this point, he offers her something to eat and drink. For them, this has become almost a ritual. He gives her the possibility to have at least a decent meal a day, but at the beginning the dinners are unpleasant. He fears to be recognized so that their dining together would spark misunderstanding and gossiping, whereas she viscerally despises him for being a privileged guy with no financial worries and yet not sly enough to avoid trouble. Now, however, the situation has evolved, and both seem to savor this recurring moment that closes their day.

Park Dong Hoon explains to her that next time she will happen to overhear someone badmouthing someone else, she would better pretend not to have heard anything: “It’s more polite to pretend as if you didn’t hear. If you end up telling them…the person whom you told will start avoiding you”—something that he is actually not doing, though. “It’s difficult to be around a person … who saw you so vulnerable. And you end up not wanting to see them”. He, instead, despite the humiliation just experienced, keeps on staying by her side. “It’s fine, as long as nobody knows. Things like these aren’t a big deal. If nobody knows…”—but now, he is not thinking of her, but of her wife and her lover: “Then it’s not a big deal”. Lee Ji An too now suddenly visualizes another scene, and recalls herself stabbing a kitchen knife in the back of the man she killed years ago. Is it really enough to pretend that nothing has happened? In a low voice, with her usual gloomy tone, she offers an alternative point of view based upon her experience: “Then…They’ll be scared until someone does find out. In case someone finds out … and they’ll always wonder who might know. And, whenever you meet someone new you’ll wonder: ‘How long will it be until they find out?’ or ‘Do they already know?’ Sometimes … I wish that I could just have it displayed on the led billboards for everyone in the world to see…instead of living in such fear the rest of my life”.

Park Dong Hoon does not know about Lee Ji An’s past yet. He senses from her affliction that something terrible has happened, something that took away from her the will to live and to long for happiness. However, he is not worried about how serious her guilt might be, because she has already passed his test, and then he says something surprising that nobody told her before: “I’ll pretend that I don’t know. No matter what I may hear about you … I’ll pretend that I didn’t hear it”. He has accepted her as she is, and assimilating her to his own feeling, he asks her to do the same with him: “So promise me this. That you’ll pretend that you didn’t hear it”, and opening up even more his RA, he confesses to her: “I’m scared because I feel like you know everything without me even telling you”. This promise will be kept by both. She will quietly guard the secrets she has learnt while spying on him, making use of such information to protect him even against her own interest and, especially, her own freedom. He will instead pick a fight with the young loan shark that has long been haunting her, and when the latter will reveal to him that Lee Ji An has indeed killed a man and that man was the loan shark’s father, a reason why she deserves all the torment he may inflict to her, Park Dong Hoon realizes that she must have taken such an extreme resolution only to save her granny from further violence. So he replies: “I’d have killed him if I were her, too … I’d kill anyone…who beat up my family”. An instinct of protection, when it leads to self-sacrifice for the other, is a feeling that, if directed at an opposite-sex potential partner, goes hand in hand not only with a more than ascertained compatibility, but with the possibility that a TU has already occurred.

3.5. The Indirect Rewards Produced by the M-RA

Rewards represent a sort of compensation that signals that one’s own or another’s behavior is appropriate. Rewards may be thought of as shots of suitable neurotransmitters (not only the ones conventionally associated with reward in the strict sense) that generate various forms of pleasure, satisfaction and excitement depending on the psychological structure that triggers their release and intensity. Indirect rewards are those rewards that originate in the RA and for this reason their features depend on the nature of this area and on the sex of the subject (M-RA vs. F-RA). The start of the production of indirect rewards coincides with the turning on of the RA, and the intensity of the reward is proportional to the level of excitement of the RA. They are called indirect because, being the RA passive in its nature, their production depends on the actual or potential partner’s capacity to willingly or unintentionally stimulate such area. Indirect rewards are therefore passive rewards in that they are unconsciously determined and externally triggered.

When a Compatibility Test is successfully passed by a potential partner, the latter enters, metaphorically speaking, in the head (that is, in the recurring thoughts) of the person who carried out the Test. This is also what happens to Park Dong Hoon, who while being at the office always looks around for Lee Ji Han to check what she is doing. Or, when passing by the restaurant where he brought her to dine the night before, he pops in and asks the owner whether he has seen her coming again. Or, when escorting her back home, takes time to talk to her. While at the pub with his friends, he keeps on talking about her: “Some kid told me … that she’s 30,000 years old…” This happens because, due to the success of the test, his RA has turned on and starts to generate indirect rewards which, being pleasurable, create an appetite for them, calling for further and gradually increasing shots, thus ending up raising the level of excitement of the RA. Just being able to cast a furtive glance several times a day at that young woman who stares at the computer monitor, a few desks away from his, is a momentary relief.

This is an involuntary mechanism whose purpose is to tap into all the opportunities that may favor the TU, that is, setting the conditions for making it increasingly likely that the RA reaches its peak level of excitement. For Park Dong Hoon, these are small but highly craved treats that help him survive, distractions from his burden of anguish—they are, among other things, serotonin shots that ease up that anxious feeling to be on the verge of going crazy. Grateful to her for making him feel good, and prompted by the desire to support that young, 20-something woman who reckons herself only when she is running—maybe because running makes her feel like she is fleeing away—he starts to carefully put at her disposal his maturity, and, reflecting with her on the lessons learnt from life experience, he eventually helps himself too. For instance, by being reminded how crucial it is to rely upon internal assets that may help one face external pressures, just like for a building it is important to resist the force of the wind and the strikes of the earthquakes, and to carry its own weight: “No matter what happens … you’ll be able to withstand anything if you have sufficient internal forces”.

The exact moment Park Dong Hoon gets tied-up to Lee Ji An, that is when his RA reaches its peak of stimulation, is however difficult to find out due to his self-controlled, reserved, and introverted nature, further exacerbated by the toughness of this stage of his life. In fact, Park Dong Hoon is trying to ignore his feelings in order to keep on with his lifeless marriage, even as his wife accuses him: “You’re not trying to keep this marriage together because of your love for me. Are you?”, convinced as she is that the only plausible reason for his perseverance has nothing to do with their relationship but is a mere concern not to let down his mother and brothers who would suffer from their divorce. He tries to explain: “I don’t want to make you miserable just to make it easier for me”, that is, not to retaliate on her by the same token: “I just don’t know how to end this relationship that we’ve maintained for twenty years. Where am I supposed to start? I thought I could get through it as long as you didn’t know … but that’s too difficult to do now. For both of us”. To his dearest friend, who left everything behind to become a Buddhist monk at young age, he confesses: “I’m forcing it. I’m forcefully holding on a heart that wants to fly away”. Complaining: “I don’t know how to live anymore”. And moreover: “I just thought that if I sacrificed myself life would go on just fine”. His friend reproaches him: “Who do you think you are to make sacrifices? I suppose you want to call it sacrifice because you worked your ass off and yet you accomplished nothing, and you’re not happy either”, to finally advise him: “Be shameless and focus on yourself. You’re allowed to do that”.

From this moment on, his constant effort at self-repression makes way to a Park Dong Hoon who accepts to be furious, and who vents his frustration by punching anything within reach, from his house’s door to the company’s CEO who stole him both his wife and his career. Now, his TU to Lee Ji An becomes visible, as he, while riding his car together with his brother, by chance notices her looking at him at a crossroads, and finally feels his heart pounding.

3.6. The Contribution of the M-RA to the Start of the TU-C

The Active Area is a psychological structure which is called active in that it processes the attraction toward and from the opposite sex, and devises its seductive strategies and behaviors as well as its responses to those of an actual, potential or refused partner. It functions at a level of subjective awareness and is responsive to the subject’s social and gender identity.

How does Park Dong Hoon manage to block the start of a new TU-C? When a male TU is formed, the M-RA reaches a peak of excitement corresponding to a strong, intense indirect reward, associated to a likely release of significant serotonin shots. The reward starts flowing toward the M-AA, the male Active Area, which has a sexual nature, and is in turn stimulated to produce its own reward, this time of a direct kind. The man feels sexually attracted and starts to crave a dopaminergic reward: physical contact, close embracing, a kiss, or just simply holding the woman’s hand to let go and gradually boost the reward, further stimulating the underlying neural pathways and possibly raising testosterone levels as well to coax the sexual approach. Park Dong Hoon resolutely blocks this flow, even before the cycle kicks off, not to send signals of sexual interest to Lee Ji An’s F-RA. He accurately avoids getting physically too close, to touch her or to seductively look at her, and by so doing he inhibits the female Test of Biological Compatibility which needs sensory input to be completed—or at least he thinks he has achieved this.

The scene where it becomes most apparent how he is trying to inhibit being tested for compatibility by Lee Ji An’s F-RA is when, in front of the door of her minuscule home, it is the young woman who moves first, calling for physical approach and bodily contact: “Can I hug you, just once?”. He turns around to look at her while already heading out, and her: “I want to hug you just once … so that I can help you feel more energized”. However, he impassibly replies: “I do feel energized”. And, after a pause: “Thanks”, while turning back again to walk away, as she silently stares into a void, stunned.

4. Results. 2: The Tie-Up from the Female Viewpoint

4.1. The Preparation of the Female Tie-Up (F-TU)

The Female Tie-Up (F-TU) is a link that unlike the Male one has a physical-sensorial, and more specifically sexual nature, even though the physical aspect of seduction combines with the mental one. A F-TU cannot occur if the potential male partner has not successfully passed a compatibility test that, in the female case, assesses his biological rather than psychological compatibility.

How many chances are there in this story that the asocial Lee Ji An falls in love with the main character Park Dong Hoon? Despite that they belong to entirely different generations and social worlds, what makes them alike on different grounds are the adversities: their personal misery and inner suffering—the failure of their lives. Lee Ji An notices the similarity from the start, but this acknowledgement, instead of bringing her closer to him, becomes a reason for deep hatred and contempt for a man who didn’t manage to reap the benefits of a world of privilege and opportunity that was denied to her. She tells him: “…Because you looked just as bored as I am. I wondered how someone could look so bored when he makes over five million won a month?”, and she uses the term ‘bored’ but really means pitiful, as if to say that if she had the same economic possibilities as him, she wouldn’t have been in such a desperate condition. Likewise, when her granny tells her through sign language that she thinks he is really a good man, that is a gentle, kind one, she answers: “It’s easy for people who have money to become good people”. For this reason, she thinks he deserves all the damage she can inflict to him: she will find a way to have him fired and, in exchange, will receive the money she needs to keep her loan shark torturer at bay.

Lee Ji An’s contempt is a feeling that originates in her F-AA, and her decision to scam that innocent man is likewise related to her F-AA, whereas at this stage in the story her F-RA is totally turned off—it doesn’t even notice the presence of a potential partner to test. In view of Lee Ji An’s background, one can assume that her F-RA has never given any sign of life, not even in the early phases of her psycho-sexual development. Her teenager years have been marked by violence rather than by the exciting infatuations that are typical of the young age in which the female Receptive Area makes its first tentative steps. Even the first and only kiss exchanged by the two main characters, that is the kiss she steals from him to frame him with an accusation of sexual abuse, has no effect on Lee Ji An’s F-RA. She justifies herself with him again by following the lead of her F-AA: “It looks like your life sucks just as much as mine … and I’m the most miserable looking person here. I wondered if I’d be less bored … if I tried kissing you. I tried it out because I wondered if it’d be fun, even for just a moment. But I was still bored and it was no fun at all. It was the same”. To stress that the kiss did not turn her F-RA on, here comes the last sentence: “It was the same”, which gives voice to an AA that has caught no signal coming from its RA. In addition, there is Park Dong Hoon’s attitude in response to that kiss: he is infuriated, and yells at her: “Do I look easy to you? After seeing me flustered when I received a bribe did you think I’d follow you around like a dog because you saved me once? Did you think I’d be happy and forever grateful to you if you approached me first? Are you having fun? Is it fun playing with an old middle-age man?”. His fury also stems from the self-awareness of his so far irreprehensible attitude, as he carefully made sure not to abuse of his senior position, of his life experience that he could have otherwise exploited to be seductive toward her.

What are the chances, therefore, that Lee Ji An gets tied-up to him? Practically none if the female Biological Compatibility Test of the male subject is unsuccessful, and in view of Park Dong Hoon’s behavior and the fact that such test calls for a sensory involvement of the female subject, this implies that the test has not even a chance to get started. My Ajussi offers us a meaningful opportunity to check how a Compatibility Test may autonomously kick off even if both the involved subjects show no interest or intention to make it happen. In this specific case, it is the one who should be tested who strives to prevent the test from happening, by systematically eschewing any occasion, however futile, for its actual launch. The stolen kiss has been the only favorable possibility for a close contact, but despite it was Lee Ji An, the female subject, who took the initiative, her F-RA could not tap into the unusual opportunity for a chemical-olfactory probe, because of both its inexperience and the adversarial block exerted by her extremely strong F-AA.

4.2. Start of the Biological Compatibility Test

The Biological Compatibility Test is carried out by females and its purpose is to check the biological compatibility of the potential male partner. In evolutionary terms, the Biological Compatibility Test has the purpose to screen the appropriateness of the male’s genetic endowment in view of a possible mating but does not offer any guarantee as to the complementarity in the joint pursuit of couple goals such as offspring rearing. The sexual dimension in F plays a more relevant role in partner selection compared to M. If the F-RA carries out the Biological Compatibility Test on a purely bio-sexual level, the F-AA may however intervene at the psycho-emotional level to facilitate or to oppose the building of the F-TU, whether already formed or still ongoing. The different characteristics of the F-RA with respect to the M-RA derive from a partition of adaptive tasks between sexes: selection of suitable genetic endowments, and joint offspring rearing-driven psycho-cultural development, respectively.

When a F-AA has such an overwhelming role in the balance between AA and RA, as for instance in cases where survival needs or trauma-related issues place the female subject into a state of permanent stress and alertness, even before the F-RA may get excited it is crucial to favorably mobilize the F-AA toward the male subject to be tested, so that it does not antagonize the functioning of the F-RA. Like for M-AA, F-AA’s nature is strongly sensitive to the specific gender identity of the individual it belongs to, but unlike the former it does not have a sexual nature. So, it is needed that the male subject be able to resonate with that particular F-AA in its own sphere of functioning, that is, the psycho-emotional one, by involving his own area that operates in the same sphere, that is, the M-RA. The latter is, however, a passive area, which means, essentially, that it is reserved and shy, and takes initiative only by recruiting its own, active, sexually oriented M-AA. In our narrative situation, this may be a problem, which is further exacerbated by the fact that Park Dong Hoon’s M-AA is resolute in concealing the psychological TU of its own M-RA and to avoid the sexual seduction of the young woman’s F-RA. Therefore, his M-AA gets stuck in the attempt not to send any kind of signal to Lee Ji An. The screenplay finds a solution to this problem by means of a ploy that is both simple and ingenious: as the old proverb has it, if Mohammed won’t go to the mountain, the mountain must come to Mohammed.

Lee Ji An, who is searching for Park Dong Hoon’s weaknesses to frame him, starts spying on him by means of a trojan horse furtively installed on his mobile phone. This way, she can listen not only to his phone conversations but also to all the kinds of sounds that are captured by the phone in its surroundings, even when not in use. Lee Ji An then peeks into Park Dong Hoon’s most intimate life, and comes to know all of his private vicissitudes, his deepest feelings—and also much more. She learns to interpret his psychological states through the frequency of his breath, the tone of his voice, the noises and even his silence. She listens to him all day long as she carries out her part-time jobs, as she walks in the street or rides the subway, and finally at night, sitting on the floor of her tiny room. It is like being sucked into some sort of radio fiction where the listener gets caught by a character’s story to the extent of self-identification, getting involved in a daily, tireless listening marathon which only stops when sleep takes over. She finally puts into focus the awkwardness that may lie behind appearance and prejudice. For the first time in her life, she escapes from her own inner world and comes to realize she has looked at reality for years only through the lens of her own tragic life story, failing to see, for this reason, any way out. Park Dong Hoon, however, is inadvertently showing her a new, unsuspected point of view on the world and a way to face up to the obstacles she took for unsurmountable.

The precise moment when Lee Ji An’s F-AA changes its attitude toward Park Dong Hoon is when he shows up with a luscious fruit basket in hand at the office of a rather rude person, who had previously humiliated his elder brother simply because the latter’s job consisted in the cleaning of the common areas of the condo where that person lived. Such person had forced Park Dong Hoon’s brother to apologize by kneeling before him for having accidentally bumped into him, and unfortunately Park Dong Hoon’s mother was a casual witness to that scene. Lee Ji An hears Park Dong Hoon addressing the perpetrator, who is sitting at his office desk: “I’ve … kneeled before too. I’ve also been slapped and cussed at. But thankfully my family doesn’t know about it. I acted like nothing happened and went home with some food. I ate dinner like nothing happened. Yeah, it was no big deal. No matter what I’m subjected to…it doesn’t matter as long as my family doesn’t know. But you can’t … do something like that in front of someone’s family. If you do that in front of their family…”—and here Lee Ji An’s mind suddenly recalls the memory of herself, still underage, got beaten up to a pulp by a man who wanted from her the money to repay her mother’s debt, whereas her disabled granny could only desperately watch the scene. Then, Park Dong Hoon goes on: “then … I could possibly kill you”—and this is exactly what she did: she stabbed that man in the back with a kitchen knife when her granny meddled in to defend her child, and he started to beat the old woman in turn.

She realizes she found the resolve to kill just because her granny had been involved in her own persecution. Then, Park Dong Hoon, as if speaking at unison with her thoughts: “My mom saw it. So I’m capable of doing anything to you right now”. At this point, Park Dong Hoon pulls out of his bag a big hammer. The other man turns pale as Park Dong Hoon starts hitting the office walls while shouting he’s a structural engineer assigned to surveillance checking of security norms for buildings, who is entitled to denounce and stop any in-house public activity in the case of construction irregularities. Still shouting and hammering, he starts listing all the possible irregularities as he intently pokes holes into the walls. The scene is totally insane, but the result is the man coming to visit Park Dong Hoon’s mother at her house, kneeling and apologizing to his brother, and offering as a gift the fruit basket that Park Dong Hoon previously brought to the office for that purpose. Lee Ji Han is distraught by Park Dong Hoon’s sudden show of force, resolution, and violence—he who up to that moment had looked so meek, submitted, and timid, kind of transfigured himself, turning from victim into avenger. He didn’t have to kill—he inspired fear, obtaining respect, and doing justice. She starts to change her mind: maybe he doesn’t deserve his misery after all, and despite this he withstands it with a remarkable moral courage and a determination unknown to her. Not only her F-AA starts to esteem that man, but it understands that there is something to learn from him. The lifting of the block imposed by the F-AA also unblocks the F-RA, kicking off the Biological Compatibility Test to be carried out through the only sensory channel available to Lee Ji An in that situation: hearing.

Generally, the female test makes use of a rich mix of sensory information that ranges from the visual to the haptic-energetic, going through smell, taste, and sound. Every female sensory channel is set to check not only the absence of anomalies, illnesses, and physical defects, but also of behaviors that may negatively influence reproductive success, such as lack of hygiene or wrong food choices as revealed, for instance, by an excess of belly fat, or inappropriate habits that compromise physical prowess, skin health, or breath smell, to make some common examples. Even mere observation of male behaviors allows to unveil important information on the genetic endowment in terms of dominance, aggressiveness, intelligence, sensitivity, instinct, and much more. The more thorough the exam, the quicker the test gets completed. What happens however if it is not possible to deploy all convenient kinds of sensory data gathering and processing? In this case, one must make sure that the kind of analysis that is available is suitably powered up so that to be able, alone, to generate very high levels of excitement in the F-RA, as in cases where one can, say, only look but not touch, or only smell but not look, etcetera. Or, like in the case of Lee Ji An, where she can only listen. That single sensory channel must be able to thoroughly involve, alone, the whole female body and mind, bringing about very high levels of focus and participation on her side, so that she is able to check by means of that single source of information Park Dong Hoon’s compatibility with herself, and specifically, with her own genetic endowment.

Lee Ji An confesses: “I liked…all the sounds you made, Ajussi. And all of your words … And thought … And the sound of your footsteps…all of it. It felt as if…I saw what a human being was, for the first time”. It is her F-RA, in the sexual sphere, that feels attracted by the sound of Park Dong Hoon’s labored breathing, as he rushes into the streets of Seoul, as if she can perceive the accelerating heartbeat, or see the drops of sweat that soak his forehead or inhale the warm smell of that transpiration. It is instead her F-AA, in the psycho-emotional sphere, that realizes for the first time what it is like to be “a human being”, and the value and beauty, even in suffering, that such ‘being’ brings with it. From the female viewpoint, this story shows how both Areas, F-RA and F-AA, may mutually coordinate, each one with its own specific abilities, to inevitably lead to a F-TU, the female tie-up. A F-TU among the most profound and transformational at the personal level that a realistic story may possibly probe and represent.

4.3. Start of the TU-C and Formation of the F-TU

The Tie-Up Cycle (TU-C) originates from the fact that the flow of information between the male and female areas occurs according to a pre-established order and direction, which depend on the areas’ own characteristics. The (passive) RA only communicates with the (active) AA belonging to the same individual, by means of the indirect rewards produced to signal about its own state. The AA is instead tailored to communicate with the opposite-sex subject with whom the relationship may take place, and in particular it can interact both with the partner’s RA, by following the proper direction of the cycle, as well as with the partner’s AA, by inverting the direction of the flow. The activity of the AA is spurred by a growing level of direct reward, that is the one produced by the AA itself, which possibly adds up to the indirect reward coming from the RA. Specifically, when the AA reaches out to the partner’s RA, the latter, if stimulated, will produce, as an effect of its own excitement, some amount of indirect reward which is also felt in its own AA. If the AA gets excited in turn, it will generate some direct reward that will sum up to the indirect reward and further stimulate the AA, pointing its attention at the partner from which the stimulation originally came. The circle is then closed, and the cycle may be kicked off.

When a TU-C starts, the TUs may still be in progress, or one of them may be already formed, or both. In its early phases, the cycle has then also the function to stimulate and favor the formation of the TUs to enhance the likelihood of the eventual occurrence of a Double Tie-Up (D-TU), which impinges upon the viability of the cycle itself. Depending on how the potential partners enter the TU-C, for instance whether they are already tied-up or not, the history of their early interactions will proceed along different routes, and likewise for the first rounds of the TU-C and for its expected durability and stability.

It is Lee Ji An the first to enter into the TU-C, and she does it by making a simple request to Park Dong Hoon: “Buy me some food”. The meals that the two main characters will share throughout the story symbolize the iterations of their own TU-C at its beginnings. At the same time, the fact that their interaction builds up by eating together establishes an interesting parallel between the progress of the TU-C and the basic act of nutrition. Park Dong Hoon steps into the new cycle by accommodating Lee Ji An, even if hesitantly at the outset, unconsciously fearing a possible involvement, made explicit through the preoccupation of being seen and recognized by someone who could misjudge their dining out together: “People will talk”.

Both start the TU-C not being tied-up. She wants to rob him and takes advantage of the opportunity to make him buy her a meal. He literally does not know what to do or think. The first encounter is embarrassing. They eat in a hurry without talking, she wears sunglasses even if it is dark—to conceal her swollen, bruised eye—and this prevents even a simple eye contact. The TU-C stays still, and no communication flow is created between them. At their second encounter, they eat more slowly but substantially persevere in their silence. He attempts a ‘thank you’ for having been helped by her with the bribe money found in the wastepaper basket, and she remains silent. He is morally indebted toward her and could repay his debt by buying her meals or even serving as a scapegoat to clear her in case of need. At their third encounter, things do not get better because, despite some struggling communication, the prevailing flow that goes through the cycle is driven by a feeling of discomfort coming from Park Dong Hoon’s M-RA—as symbolized by his refraining from eating—as a consequence of the repeated attacks from Lee Ji An’s F-AA.

The CEO who enviously wants to destroy Park Dong Hoon asks Lee Ji An: “Isn’t Park Dong Hoon a pretty decent guy? A lot of girls liked him. They’re so strange. Why would anyone like a guy like him? You don’t have any desire to date him for real?”, and then suggests: “An inappropriate relationship forced upon you because he abused his power as your superior. You can get reward money for that too. If you say that you had no other choice because he forced you. I won’t fire him immediately. Just date him, for now. This is 10 million won. I thought I’d need to pay you in advance for this. I need to have a card to play, too. And I need you to keep tabs on what he’s up to and who he’s meeting on with and what he’s talking about, and with whom. And date him. I’m paying you in advance so that you’ll work hard”. She replies: “And how can I ‘work hard’ exactly? Do I need to get naked and throw myself at him?” He clarifies: “Obviously not that. If you do that, he’ll panic. I’m sure you know what he’s doing all the time since you’re always listening in on him. Approach him slowly, and act as if you ran into him by chance. Keep creating little coincidences like that. So that, when the time comes…he won’t be able to escape unscathed. So that he can’t jump away completely denying it”. However, she seems perplexed: “What kind of crazy man would like a woman like me?”. So he comes to the point: “Just eat with him, and drink with him. Just do that”. She is still hesitant: “Eating with him, and drinking with him. Does that mean that he likes me?” After all, it is a common habit to meet and eat together, and many people do this when they want to get something from others. However, the CEO, who has been acquainted with Park Dong Hoon since college times and knows him very well, having grown a competitive obsession about him, when asked: “Don’t a lot of people do that?”, dryly answers: “Not Park Dong Hoon. If he eats or drinks with someone that means he likes them. And make it so that he can’t back out, no matter what”.

In view of the strong psycho-emotional role that food takes on in Korean culture, in terms of carrying on tradition, connecting to ancestors’ legacy, and symbolically encompassing family relationships, elective affinities and the cohesion among people with similar cultural, economic or social backgrounds (

Chung et al. 2016;

Lee and Kim 2018), it is not surprising that the psychological integrity of a reserved, shy man such as Park Dong Hoon manifests itself also and especially in considering his meals—those with his mother and brothers, with his wife, with his staff, with his friends at their habitual neighborhood joint—as a tangible expression of his own feeling of bonding, affinity and affect for them.

This is why we can find in the evening encounters between the two main characters to eat and drink together such a fitting parallel with their TU-C: because it is Park Dong Hoon himself that confers a high symbolic meaning to eating and drinking with someone. Sticking to this key metaphor, it is interesting to remark how it is entirely possible to step into a TU-C with far from benevolent dispositions, concealing the actual lack of real attraction for the partner even under a simulated TU, with the sneaky intent to exploit the other’s one-sided TU. This is what Lee Ji An should do. Despite being the one who has the idea to make him buy her meals to circumvent him, when Park Dong Hoon starts being more relaxed toward her, she hesitates and feels insecure. The reason is that nobody before was really interested in her—“what kind of crazy man would like a woman like me?”—and then, why he does? Why does he accept to eat with her if having meals with others has for him such an exclusive value? What appears to be the only realistic hypothesis to the young woman’s mind is also one that hurts her pride, or better her F-AA that just started to esteem him: he is doing this out of pity.

Then she tells him: “You said you were afraid that word would get out about us eating together. But do you feel better about it now, since you pity me? You just keep buying me meals because if anyone says anything you can just tell them how pitiful I am. Don’t think … that there was never anyone in my life that helped me. There were many people who helped me. They brought me side dishes, and rice, too. Once, twice, three times, four times. After the fourth time they all ran away. All while scorning me for living a life that will never improve. They all must have thought that they were actually nice people”. And him: “They were. Four times is still a lot. After all, there are plenty of people who didn’t even help you once. I get where you’re coming from. But my life is no better than yours. And I’m not buying you food because I pity you. I’m treating you to thank you”. To thank her for being something positive to him, for being an unexpected intermission that is somehow helping him to get through what is likely the toughest period in his life. How? By dragging him into their struggling and still incomplete Tie-Up Cycle. Because the most beneficial feature of a TU-C is distracting people from any egocentric focus to grow an interest for the other. Forgetting about oneself, even just for a short period, and despite this, receiving even more intense rewards than those secured by a self-interested act.

Park Dong Hoon has tied-up to her. He also told her: “I’m only treating you because you deserve it”. The consideration she has earned is strictly related to the impression that she made to his M-RA, that is, to the successful outcome of the Psychological Compatibility Test: “You’re a good person”. It is the indirect reward that his M-RA is producing by relating to Lee Ji An that is literally rescuing him from the abyss. As to his direct reward, the one produced by the M-AA, it cannot have a purely sexual character, not to spark a conflict with his M-RA’s salvaging intent. He is rescued if he rescues in turn, that is if he protects a young woman whose disgrace has captured his thorough sympathy. A sexual approach, in addition to contradicting his moral principles as a man already committed to a marriage however delusional, would also be an abuse in view of Lee Ji An’s psychological condition. She had to grow up too quickly after having been abandoned, blackmailed, beaten up, forced to commit crime, and has therefore literally gotten stuck in the devastating trauma of having killed, no matter whether for self-defense. This was too much for her young age.

Thus, the male hemicycle of the TU-C closes with a M-AA that, instead of seducing, protects, supports, and advises. He becomes for her what Koreans would call an Oppa, an elder brother that buys her meals and drinks, who looks for her when she is fleeing, finds her and brings her to the hospital to fix a broken bone and, moreover, talks to her, teaches her how to access public assistance to cure her disabled granny, and finally finds her a home and a vicarious family ready to welcome and show her affection. However, in view of the large age difference, her Oppa actually turns into her Ajussi, her Mister. For her, he confronts the son of the loan shark, makes an offer to repay the missing part of her debt only to realize that the other does not really want the money back, but prefers to destroy her life because the guilt she must (but can never) redeem is that of having killed his father. Then, he engages in a wild fistfight with the young criminal, that goes on until both fighters are completely exhausted.

Nobody ever took her defense. Nobody fought for her, and nobody ever justified her by saying that, in her position, they would have done the same: “I’d have killed him if I were her, too. I’d kill anyone … who beat up my family!” With these words, which Lee Ji An listens to through the hijacked phone, she is finally acquitted of her guilt and for the first time ever she desperately weeps—a liberating cry. Lee Ji An gets tied-up and her TU is immediately strong and firmly rooted, being the result of an intense synergy between her F-RA and F-AA—of a deep-seeded sensory shock on the former, and of a stark psycho-emotional impact on the latter. In her specific case, unblocking her F-AA has been crucial and resolutive to allow the kick-off of the female test and of the TU, also with the help of a certain amount of frustration—when he seems to ignore her—which was useful to make her realize she was tied-up herself.

If initially their shared meals (a symbol of the early iterations of their TU-C) were awkward due to their emotional toggling between embarrassment, resentment and frustration, now the flow of rewards goes smoothly through the cycle. A scene that makes such change fully legible is Lee Ji An running to reach Park Dong Hoon to drink a beer with him, smiling and making auguring toasts: “Let’s be happy”. The quicker a TU-C gets iterated, by generating recurring waves of rewards that effortlessly cause it to rush along, the more the TUs will grow and fortify and the cycle itself will stay healthy. The term that Lee Ji An uses to describe her ‘special talent’ in the CV that Park Dong Hoon parsed at the moment of hiring her is none other than: “running”. When she asks him: “Why did you hire me?”, he tells her that he was impressed by that ‘running’, further explaining: “You seemed to be mentally strong”. When he discovers she never practiced running as a sport and asks her about why she wrote that in her CV, she confesses: “When I’m running … I disappear. But … I feel like that is the real me”. Maybe it is just a coincidence, but Lee Ji An is literally describing the effect that a fully operating TU-C has upon those who are part of it. “I disappear” stands for one’s taking their own attention away from themselves to direct it toward the partner, with the surprising result to reckon themselves even more in the interaction with the other: “I feel like that is the real me”.

5. Results. 3: The Formation of the Couple

If the success of a Compatibility Test is not a guarantee for the ensuing emergence of a TU, likewise the emergence of a D-TU, despite being a necessary condition for the persistence of the TU-C, is not a sufficient condition for the TU-C’s viability, that is, for the formation of a tied-up couple.

In this story, the couple is not formed eventually, despite the drama’s ending being cheerful. The main characters get tied-up, the D-TU emerges, the TU-C has a good start, but Lee Ji An finds a new job and moves to another city. Why?

The last iteration of their TU-C is a sequence of thanksgivings. She tells him: “I want to try living my life as a different person. I want to go to a place where nobody knows me … and live as if I have no history at all. If we happen to run into each other by chance … we’ll be able to act as if we’re happy to see one another. And for that, I’m glad. When I was on the run, I thought…that you’d avoid me even if you ran into me by chance. And that was what made me most sad. Thank you…for allowing me to reveal everything. Thank you for being so good to me”. Then, he replies: “You must have come to this neighborhood … in order to save me. I was on the verge of dying…but you were the one who saved me”. Then, she again: “I really lived my life for the first time ever…because I met you, Ajussi”, and after a hesitation, she makes an attempt: “Is it okay if I hug you, just once?” She made the same request already in the past, because a tied-up F-RA always seeks physical closeness, but that time he made a step back. Now, finally he hugs her in a warm embrace, and we see clearly how she finally has the confirmation of the outcome of her auditory test through other sensory channels, and she would not loosen up that contact, but after a while he breaks away and releases her.

Park Dong Hoon’s choice is not an easy one. It is a choice driven by love, by someone who is ready to self-sacrifice to this extent for the good of the other, to allow Lee Ji An to become a fully mature adult and to leave her sad past behind. To become a different person, the one she should have been from the outset, at this point Lee Ji An needs, and must, walk alone toward the new life awaiting her. This is why Park Dong Hoon makes a step back and aside. Had he accommodated his physical attraction toward her, she wouldn’t have wanted to leave anymore. The following scenes depict all the suffering that the sacrifice entails on Park Dong Hoon’s side, because a TU that stays outside its own TU-C is very hurtful. The screenplay therefore does not opt, luckily, for the obvious happy end of the romantic story cliché, and shows how it is also possible, even when all goes in the right direction, that the partners do not end up forming a happy couple. From the Tie-Up Theory viewpoint, this is a good example to stress that there is nothing pre-determined and mechanistic in the functioning of a TU-C, and how dynamic and flexible, depending on cases and contexts, the interaction among its AAs and RAs may be. Positive or negative, mating or not, and so on: all outcomes are possible under suitable circumstances.

The drama has in fact a beautiful open finale. After a few years, one day it happens what Lee Ji An augured for: “If we happen to run into each other by chance…we’ll be able to act as if we’re happy to see one another”. Lee Ji An is now an accomplished full-time employee. The company she works for, to reward her, has called her back to their Seoul headquarters, and the two main characters meet again as she recognizes him without the need to visually spot his presence. Walking into a bar with her colleagues, she hears his unmistakable voice. The camera shows her back as she moves following that sound, so that it becomes possible to see the scene from her own viewpoint, when she finds him out. Through her eyes, we now see Park Dong Hoon’s back as he sits at one of the many tables all around, speaking to the person next to him. During these years, he has parted ways with his ex-wife, who left to live with their son studying abroad. Moreover, he quit the company for which he worked and opened his own civil engineering consulting firm, taking the CEO role, and bringing with him his affectionate work team.

When he turns around and sees her, he stands up and his surprised, emotional smile, his radiant face, his overall bright aspect confirm that his M-TU has survived and resisted to all changes, to distance and time. They talk briefly, and when she has to go back to her group of colleagues waiting for her, he proposes: “Let’s shake hands, just once”. The past roles have flipped, and it is him seeking physical contact now. At last, he feels empowered to touch her, and his handshake is resolute, warm, and snug. He thanks her and it is now her who flips to his old position, finally being able to treat him: “I’ll buy you a meal. I want to buy you something delicious, Ajussi”, and as he, moved, smiles even more, she, an instant before turning back and walking away, tells him: “I’ll call you”. As they move in opposite directions, they keep on talking to each other in their thoughts. He asks, calling her by name: “Ji An. Were you able to find some comfort for yourself?” Then, her, in her mind, now aware he had been waiting for her all this time, answers with two sounding, rejoicing “Yes”. The drama closes with a promise, with the reciprocal desire to meet again. Neither of them is any longer the gloomy, depressed person they both once were, and Lee Ji An, with her “I’ll buy you a meal” has clearly signaled her intention to restart their TU-C on new grounds.

6. Discussion and Conclusions

In this paper, we have analyzed

My Ajussi, a Korean drama that cannot be typically classified as a romantic story, as its narrative development rather focuses upon the difficult relationship between the two main characters which, in the story’s open finale, might (or might not) lead to the birth of a new couple. We have shown how such component of the narrative development closely reflects, in the perspective of the so-called biosocial approach to fictional narratives (

Boyd 2010), the structure of the interaction finalized to the possible formation of a couple as characterized by the Tie-Up Theory (

Lucchi Basili and Sacco 2017,

2018). It might, however, seem contradictory that, in the light of such a close correspondence, the story ends without the formation of the couple—an outcome that the finale envisions as possible, even likely, but that is not granted. In fact, however, even in the presence of the best enabling conditions, the eventual outcome depends on the influence of a quantity of factors that may antagonize or favor the functioning of the TU-C (

Lucchi Basili and Sacco 2020a). The fact that failing to represent the formation of the couple does not jeopardize the interest and the social cognition valence of a romantic fictional narrative eloquently illustrates how what matters in this respect is the process more than the result, and that even the failed achievement of the result may be in turn a very interesting source of useful social cognition.

The formation of a couple never follows mechanical rules, and this is all the truer in the most effective examples of fictional narratives. It is for such reason that the human interest for narratives that focus on couple interactions is practically inexhaustible. Each effective fictional narrative manages to identify a specific, meaningful variant of the interaction process among the many possible ones, and its interest lies in the fact that it drives the attention toward a combination of factors and possibilities that sheds light upon as yet poorly considered nuances, and especially on how such combination favors certain types of choices and responses by the characters. The interest of My Ajussi lies also in the fact that the TU-C works in favor of the formation of a possible new couple in a context where there seemed to be not the slightest possibility for this to happen—and not incidentally the story centers the female Biological Test on a sensory dimension notoriously important but often overlooked in romantic fictional narratives: sound, and in particular the main character’s voice, his breath, the sound of his footsteps, that is, a quantity of visceral signals transmitted through an unusual channel.

It is the sound that allows the laying of a bridge that overcomes the unsurmountable physical barrier built by Park Dong Hoon, the male lead character, toward Lee Ji An. This is also, in itself, a circumstance that strengthens the social cognition valence of the story: whereas it is usually said that for men (and in particular for their M-AA) the search for sexual gratification is a basic driver in the interaction with the opposite sex, we have here a man who, despite being humiliated in his sexuality by his wife’s cheating on him with his worst enemy, provides a remarkable example of virtue, and specifically of moral courage (

Peterson and Seligman 2004;