Abstract

Deans, associate deans, and department chairs in higher education institutions manage not only their departments’ course offerings but also faculty and students who teach and learn both in person and online. Possessing a good understanding of how to plan, supervise, and evaluate online degree programs for maximum efficiency, optimum student learning, and optimum faculty support is imperative for these professionals. The purpose of this study was to investigate administrators’ perceptions, attitudes, and experiences managing various online learning environments. A basic qualitative research design was applied to this study. Current and former administrators were invited to participate in individual in-depth interviews that were transcribed and analyzed for emerging themes. Results indicated that administrators need multiple levels of support, including supervisor’s support as well as instructional and technology support, among others. It is concluded that administrators find themselves in “a continuum” in terms of the need for different types of support. Implications for further research are discussed.

1. Introduction

The purpose of this research was to examine administrator perceptions and attitudes regarding online learning as well as their experiences in various online learning environments. Understanding administrators’ experiences and perceptions can facilitate better course design for future courses, which can result in better student and instructor experiences and may even improve class retention [1].

Online learning has become a ubiquitous feature of instructional programming in institutions from middle school through post-secondary education. Across the nation, the demand for online teaching continues to steadily increase according to data from the U.S. Department of Education, National Center for Educational Statistics [2]. Currently, about one in six college students is enrolled in a 100% online program and more than 33% of college students are enrolled in at least one online class [3]. Additionally, a substantial proportion of students take classes that include online components. Our public university located in the southwestern United States is no exception. Even though many faculty and students profess to prefer face to face classes, the campus is abuzz with talk of new online programs and initiatives—aimed to ensure greater student access—as well as to boost enrollment. Indeed, improving and proliferating online learning is a focal point on almost all university and college campuses both nationally and internationally. The expansion of online learning options meets the President’s mission, as well as the vision statement of the Board of Regents that governs our state institutions.

Today’s university leaders, department chairs, associate deans, and deans face multiple challenges as they create, plan, and implement their institutions’ strategic plans as they relate to the inclusion and expansion of online courses, programs, and degrees. University administrators increasingly included an online learning capability among the tools employed to implement their strategic plans and achieve their university’s mission and vision. In this article, the authors determine how selected administrators’ (current and previous) perceptions regarding supervision of online teaching and learning in this e-learning revolution can strengthen access, teaching, learning, diversity, and the overall mission of colleges and universities.

The COVID-19 pandemic has forced institutions of higher learning, as well as K-12 school and school districts, to move quickly to implement on-line course delivery, as well as develop alternative methods to in-person instruction and only a few readers would argue that online learning provides some benefits over in-person instruction, both for the learner and for the learning institution. Learners gain convenience, ease of access, and, frequently, more personalized learning in the online setting. Institutions benefit from the ability to offer coursework without being limited by students’ lack of proximity to a particular location. Institutions may also experience online delivery as a more cost-effective and efficient way to deliver instruction, potentially reducing expenditures for classroom facilities and for personnel. When designed well, online courses offer the potential for greater personal connections and differentiated learning for students.

This article is intended to provide, in a concise and conversational manner, practical recommendations to leaders of online programs. The authors explore the “why” of online learning, related technology and funding issues, curricular design and delivery methods, the human resource demands of online programs, support services, best practices, and potential pitfalls.

Much is required of those in leadership positions, particularly those who lead online learning programs. The online learning landscape will continue to change dramatically in the coming years, and the coming changes will affect instructional practices, the tools of technology, curricular standards, methods of assessment, and the faculty evaluation process. While the authors of this brief article do not lay claim to any special insights regarding coming changes and innovations, it is hoped that this article will serve as an effective foundation for leaders who are committed to continuous improvement in online learning.

2. Review of Literature

How is online learning defined? Singh and Thurman [4] conducted a literature review that covered research studies from 1988–2018 with the purpose of finding standard ways of defining online learning. One of their findings was that the use of technology was the essential element when referring to online learning, and that the terms online learning, e-Learning, web-based instruction, and others refer to basically the use of technology to teach and learn in a physically separated space. Thus, the terms “online learning”, “online education”, and “e-Learning” will be interchangeably used in this document.

When the Babson Research Institute started to track online education in 2002, only about 49% of higher education institutions considered e-Learning as strategic for their growing goals; by 2014 that number grew close to 71% [5]. Furthermore, online student enrollment continued to grow even as in-person student enrollment dropped in 2016. Because public, 4-year institutions were among the first type of institutions to launch online learning programs, they continue to have the biggest share of e-Learning programs and students enrolled in them. In fact, the National Center for Education Statistics reported in 2016 that 95% of 4-year public institutions offered online programs as compared to 78% of private 4-year institutions [6]. Unsurprisingly, 4-year public institutions continue to rate online learning as strategic for future growth. On the other hand, students who reported not taking any online class continue to decline [7]. In the latest publication of their survey results in 2018, Seaman, Allen, and Seaman et al. [8] reported that distance education enrollments continued to steadily grow for the last fourteen years. That is, not considering online education as strategic for growth is not an option anymore because both the offer and the demand for online programs continue to grow. This steady growth is being stimulated by advancing technologies, the almost ubiquitous use of the Internet, and the demand for a workforce that is developed to cater to the global digital economy [9]. These same researchers ventured to predict that online education may become mainstream as early as 2025. Yet, even when educational leaders acknowledge that e-learning is essential to both the institution and their stakeholders [10], not much has been written about middle management perceptions (department chairs, deans) in terms of managing e-learning programs [11]. This is important because Allen and Seaman [7] reported that only 28% of educational leaders believed that their faculty accepted online education as valuable and legitimate. However, in the same year, Willcox et al. [12] proposed that online education could be a catalyzer for higher education and could serve as digital scaffold for teachers by allowing for personalized instruction, online collaboration, and continuous assessment, among other benefits.

Before considering e-Learning as strategic for future growth, the Higher Education Act (HEA) of 1992 dictated the 50% rule; that is, institutions that offered more than 50% of their programs online or enrolled more than 50% of their students in online programs would be denied Pell grants, subsidized student loans, and work-study funding [13]. It was not until 2006 that the rule was abolished. Speaking in institutional years, offering an abundance of online learning programs is a relatively new development. As such, many institutions are still trying to find the best way to fund, create, and administer their online programs. Chief among the administrators’ reasons for offering online programs, Özcan and Yıldırım [14] found the following: demands for programs, congruence with educational mission, present infrastructure, qualified teaching staff, ability to adapt the content to online offerings, economics of on-campus spaces for teaching, revenue, and gaining prestige for the institution; these findings had already been established by Popovich and Neel [15]. While the entire institution is responsible for making online programs successful, it is the administrators in departments, schools, and colleges that bear the brunt of day-to-day operation of such programs. In fact, Alexander [11] stated that online education requires not only committed faculty but also the participation of administrators that make strategic decisions to establish and administer infrastructure that promote and support online education. The same author explains that this infrastructure includes specific training for faculty, hiring the adequate faculty, technology, and technology support for both faculty and students, among others.

Administrators have one of the principal roles in hiring faculty, especially part-time (also called “contingent”) faculty. Having dedicated faculty can favorably impact student attrition. Lee et al. [16] and Pardino et al. [10] established that student–faculty relationships have a strong correlation with student learning success. Faculty provide students with a door to discover new concepts and to establish a productive dialog through timely feedback. While many part-time faculty members are specialists, experts, career changers, and retired professionals with much knowledge in their professional field, they may need some training in both online pedagogy and technology ([17,18], among others). In terms of pedagogical training, Schmidt et al. [19] found that faculty need focused training on online pedagogy and course design. Technology training is another specific need of e-Learning faculty. Several researchers ([20,21,22], for example) found that teaching and digital competence self-efficacy had a major impact on teaching effectiveness and both faculty and student satisfaction with online learning. Furthermore, perceived technology competence fostered more faculty participation in online learning. On the other hand, Kebritchi et al. [23] found that existing faculty may deal with other barriers, such as changing faculty roles, moving from in-person to online learning, and seemingly incompatible teaching styles for e-Learning.

Online faculty can also have difficulties with content development. Some faculty may feel that they, as course faculty, have little say in content development that includes the use of multimedia for teaching, selecting content, and application of specific instructional strategies [23]. This is important because lack of a sense of ownership may prevent faculty from fully engaging with the content and, thus, the students. Online learning faculty, through their teaching presence, provide the opportunities for students to engage in cognitive presence in course activities, including the discussion boards which, in turn, builds their own social presence. The combination of these three presences: teaching, cognitive, and social form the bases to have a community of inquiry that is necessary to engage learners with the content [18]. At the end, frequent and substantial student–instructor interactions are the gateway to build online learning programs that can better serve more students, regardless of their previous academic preparation and socioeconomical background [24,25]. As administrators seek to have faculty who engage students’ interests and foment retention, providing technology training and a well-established technology support infrastructure are two of the essential tools to successfully manage e-Learning programs.

As already established, faculty need professional development and administrators need to keep several considerations in mind. For instance, they need to plan faculty professional development opportunities having in mind not only their campus-based faculty, but also faculty who are geographically dispersed; they need to consider the different technology competency levels at which faculty are so training is attractive to participate and relevant to faculty [26]. Administrators also need to provide opportunities for faculty to form professional and support networks among geographically distant faculty and to offer such opportunities in different formats, i.e., online, in-person, synchronous, asynchronous, etc., so it is easier for faculty with different technology levels to engage in learning [17]. Technical support for online faculty, as well as for online students, plays a substantial role in student retention and faculty agreeability to teach online. Some types of institutional support come from specialized departments that guide faculty on instructional design to develop their courses, the use of a learning management system (LMS), and even allowing faculty to “get their feet wet” by acting as students of online courses before they become the instructors [27]. While pedagogical and technical support are important, online learning faculty also need administrative support and faculty recognition of their achievements [10]. Clearly, the role of the administrator cannot be overlooked. Besides playing an important role in selecting and hiring online faculty, it is the administrator who is the relationship builder, the mediator with students, and a bridge to achieve faculty and student satisfaction in online education [28]. It is the administrator who makes strategic decisions to facilitate and foster sustained support for online education endeavors.

In general, several authors offer their findings on what has worked best in offering online learning programs. Some of them are presented below.

- Establish Lead Faculty for online programs. Innovative and well-versed in developing online quality courses, these faculty coordinate and facilitate course offerings and building schedules. They also provide contingent faculty with course shells that require minimal customization. This decision also allows full-time faculty to keep control of the content in different courses [11,27].

- Provide contingent faculty with training that targets fostering teaching, cognitive, and social presence in the online classroom. Promote retention and satisfaction among e-Learning faculty by making them an essential part of the department and the institution. Additionally, invest in strategic training and support that is specific for online learning faculty [17,18].

- Administrators serve as bridges between physically distant faculties and students’ access to institutional administrative supports and services [28].

- Establish clear policies, procedures, and structures to support online learning programs [14].

- Foster a feeling of belonging and connectedness among students to help them overcome obstacles to improve persistence. Some ideas are a partial residential program for doctoral students, and online opportunities to interact with other faculty and students [16], contacting students periodically to check on their progress, and evaluating student preferred learning style and computer fluency at the beginning of the semester [10]. Additionally, placing warning and monitoring systems so struggling students receive help before they withdraw from a course [13].

- Provide multiple options for professional development that focus on course design, technology use, and content-specific topics. These opportunities work best if they are at different levels of the institution, are smaller and more targeted, foster communities of learners, and provide means for self-directed learning [19,26,29].

- Open paths to openly collaborate with outside institutions, such as governmental and non-governmental institutions, industry leaders, and innovators to realign existing programs to foster relevancy, alignment with industry needs, and innovation [30].

- Openly communicate with faculty the reasons for an online teaching assignment and provide faculty with institutional support in the form of acknowledgement of increased time and workload commitment, enrollment caps, development of online faculty communities, and appropriate teaching and proctoring software [20].

3. Methods and Procedures

3.1. Purpose of the Study

The purpose of this qualitative study is to understand the perceptions of current and recent past administrators (department chairs, dean, associate dean) in a College of Education regarding challenges, successes, and support needs concerning online degree program administration. Anticipated general benefits of this study include increased administrative understanding of how to plan, supervise, and evaluate online degree programs for maximum efficiency, optimum student learning, and optimum faculty support.

The study, through the administration of probing questions, determined how the administration of online courses and degree program may (or may not) differ from the administration of more traditional in-person delivery of courses and programs. Additionally, it also determined what support of faculty and students is required of leadership, which would not typically be required when leading traditional courses and programs.

3.2. Research Questions

- What are administrators’ experiences and responsibilities as they relate to online instruction related to the areas of: course management, learner objectives and outcomes, social interactions, and technology requirements?

- What are the benefits and challenges of offering courses and degree programs online?

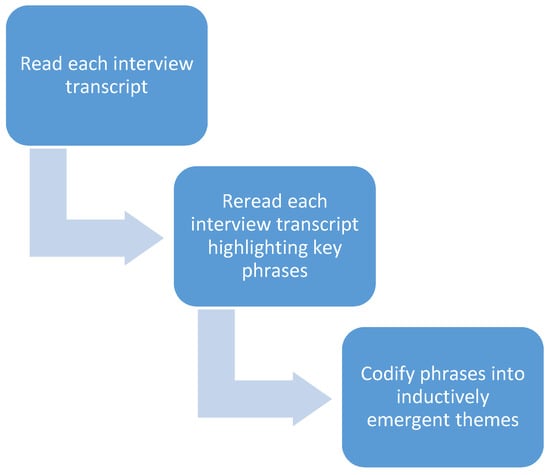

A basic qualitative ethnographic research design [31] was applied to this study. Qualitative research in its different forms (ethnography, case study, narrative inquire, etc.) provides a conduit to understand problems of practice by engaging with practitioners who have first-hand understanding of the issue at hand. Qualitative research results can help shape policy and practice [32]. Semi-structured individual in-depth interviews were conducted via Zoom with seven current and former administrators in the College of Education at Northern Arizona University. A semi-structured interview approach was selected because it is especially suited for situations when immensurable contextual features, such as the impact of leadership style on managing online courses and programs, may take time to be reflected in performance measurements [33]. Qualitative research also helps to understand process-oriented phenomena as managed by different individuals under different circumstances [34]. The study fits the internet/virtual ethnography design, given its focus on subjects’ personal accounts of their lived experience with online instruction, as well as the use of videoconferencing to conduct in-depth interviews with the administrators [35]. Participants consisted of the current dean, a former dean and provost, and five present or former department chairs, one of them currently serving as an assistant dean, from the College of Education. Subject were asked to participate because of the administrative positions they held or hold. The researchers contacted the subjects and asked them to participate in an interview to collect their perceptions and impressions of the administration of online programs. Interviews were conducted via Zoom and transcribed for content analysis of key emergent themes. The researchers elected to conduct the interviews using Zoom because of the COVID-19 pandemic. However, some researchers [36,37] have already documented the use of this tool to conduct qualitative research. The use of thematic analysis as a method [38] was selected because it is useful in understanding activities, thoughts, and behaviors across a data set, so they are identified, analyzed, and reported [39]. Patton [40] classified thematic analysis in qualitative research into two general subtypes (typologies). In the indigenous typologies, the researcher applies or adapts an existing conceptual framework of themes. In the analyst-constructed typologies, the researcher does not start with a predetermined theme, but instead determines the themes entirely inductively through iterative reading of the raw qualitative data. The authors of this paper applied the analyst-constructed typology to their analysis of the interview transcripts. The process is depicted in Figure 1. An inductive approach, similar to that used in grounded theory analysis, was utilized to identify themes offered by the participants and which may or may not be reflected in the original interview questions [39]. This inductive analysis usually yields a more complete analysis of the entire data set.

Figure 1.

Inductive data analysis process.

4. Results and Discussion

Emergent themes are identified below corresponding to each of the following questions. Besides using the coding approach of emergent themes, a quoting approach is used to present the results because participants’ quotes add depth to the presented themes [38].

4.1. Benefits of Online Courses

Four interviewees mentioned access as the greatest benefit of online courses for students. Three subjects singled out ease of delivery to remote areas in Arizona where students are located. One interview subject noted a greater ability of the online classroom to accommodate a diversity of students due to the absence of geographic limitations. This is especially important for members of Indigenous communities where being in a communal setting and learning from elders is of utmost importance to maintain cultural identity [41].

Along with access, online instruction was noted for flexibility of delivery, with students and instructor having 24/7 access to the classroom to interact. The ability of students to work at their own pace was highlighted, along with being able to travel for personal of business reasons without missing class. In the same way, online instruction provides the opportunity to avoid having to travel or relocate to a different place. This is important for busy adults who already have family commitments and/or financial concerns [42].

Online classes are also characterized by greater opportunity for student participation. As explained by one interview participant, “[there is] not enough airtime [for everyone] to talk in a live class”. In contrast, the asynchronous discussion forums are a way for all students to talk even at the same time and with 24/7 opportunity to contribute to the discussion. Interestingly, one interview participant noted fewer problems of student comportment and courtesy of communication in online courses than in face-to-face courses. This comes as a no surprise because previous research in asynchronous communication has indicated that students are able to engage deeply with the content and ponder their thoughts before posting a response. The results are more reflective responses and a stronger sense of being part of a community of learners [43].

Convenience of class scheduling was another benefit of online classes noted by administrators. According to one subject, the online classroom allows administrators to “bring large groups of students together in one space”. Another subject mentioned this benefit as the ability to aggregate and pool enrollments, thereby capitalizing on efficiency of course scheduling.

Online classes also facilitate record keeping and documentation of instructional interaction. As noted by one interview participant, everything is externally documented, and time stamped. This externally verifiable trail of student and instructor engagement facilitates administrative responses to grade appeals. An intriguing side effect of asynchronous participation is the enhanced ability of instructors to notice students who may be struggling or inactive. Those students who do not participate stand out better via their visual absence from discussion forums or live sessions. Instructors also use the built-in tools in Learning Management Systems (LMS) to keep track of student participation. These tools are mainly designed to be unintrusive for students but to provide instructors with good actionable data [44,45].

Curricular innovation was highlighted as a plus of the online classroom. One subject praised the ability to “showcase and deliver exponential content” using a variety of learning materials, including external resources to link to in the web-based classroom learning space. Along these lines, another subject praised the wider accessible pool of creative learning resources such as videos, podcasts, and outside readings that can be easily built into the online classroom and accessed by students. This is an important issue for students learning and satisfaction. It has been reported [46] that the use of multimodal formats in online classes produces shorter perceived transactional distance between instructor and students, more student satisfaction with the course and instructor, and more perceived and actual student learning.

4.2. Drawbacks of Online Courses

Relationship building was noted as challenging to achieve in the online classroom. Courses such as certification courses require getting to know one’s students on a deeper level than may be possible with online courses, particularly those that are asynchronous in nature. One subject shared that building Zoom sessions into online instruction may mitigate this challenge of forging relationships with students to some degree.

While ease of communication was praised as a benefit of the online classroom, the tone and intent of communication could be problematic, especially in text-only asynchronous communication. It may be challenging to capture the full range of emotions in online communication, according to one subject. Another stated, “People sometimes say things (asynchronously) they wouldn’t say in person”, according to one interview subject. As another study participant put it, students may act differently in person than online when communicating with peers and faculty members. As a result, administrators have had to mediate online communication conflicts. As discussed above [47], asynchronous communication has its benefits. However, it has been documented that one of the drawbacks of this medium of communication is that it is prone to misinterpretations of text, thus creating conflict [45].

Even positive and proactive classroom communications can be at times artificially altered in the online classroom setting. Spontaneity of real-time whole-group class discussion may be difficult to achieve, especially in asynchronous discussion posting formats. This is especially true when trying to foster cooperation and participation in groups that work in an asynchronous way [43]. At the same time, this spark of group interaction may be partially facilitated via inclusion of live Zoom sessions. Some researchers [43,48] have reported that synchronous interactions foster feelings of belonging and connection to peers and instructors. Zoom and other video conferencing tools are important in the online classroom because they allow participants to see, at least partially, body cues when communicating with others [47].

As the pandemic has taught us, curricular transfer of real-time classroom content to the online classroom format may be difficult to achieve. The face-to-face curriculum needs to be extensively rethought, revised, and reformatted. Along with this curricular design issue, several interview subjects acknowledged that not all learning material can be effectively taught online.

Administrative recruitment and training of faculty who can teach effectively online has presented challenges, according to one interview subject. Administrators need to consider the unique skill sets necessary for effective online instruction and how to identify or build these skills in their faculty. In fact, administrators recruit faculty based on their expertise in the content matter rather than their expertise in technology. As a result, administrators recruit specialists, experts, and professionals who usually hold a full-time job [17] but who may not be technology experts.

Technology failures can occur in various forms. As one interview subject acknowledged, if something does not work in the face-to-face classroom, it is easier to move on to something else. However, a technology glitch can easily bring things to a complete standstill in the online classroom. The role of technology support will be examined in detail in the following section.

4.3. Adequacy of Technology Support

Administrative interview subjects praised the quality and accessibility of technology support at Northern Arizona University as a primary reason for success of the school’s online instructional initiatives: “[telephone number of the help desk] isn’t only on my speed dial, but I’ll remember that number when I’m 85”, as one subject memorably put it. According to another administrative interviewee, “I’d give [the help line] 5 gold stars”. A third vividly stated, “[they can] resurrect dead carcasses”. Quick responsiveness to questions, availability for follow-up to training session participants, efficient copying of course shells for the upcoming term, and continual offering of e-learning tutorials to the learning community were singled out for praise.

At the same time, administrators shared some wish lists that would boost the helpfulness of technology support even further. One subject wished for a “cheat sheet” of most frequently used technology operations in navigating the online classroom. “If you can’t hold my hand, please give me a flow chart” is how another interviewee put it.

Several administrators also wished for a better stratification of IT support by prior computer experience of students and faculty. According to one subject, IT support needs to exhibit more patience with computer beginners. “The learning curve is so great right now” due to the pandemic and need to port traditional face-to-face instruction to a computer-mediated format, another subject shared. There is also a distinction between “standard boilerplate training” and being able to get specific help with a question or problem.

Several interview subjects bemoaned the current inability to sit down face to face at the computer with an IT expert to get help. They hope to see such real-time in-person help sessions restored by IT when the pandemic has passed.

4.4. Skills That Are Necessary to Teach Online

Effective online faculty perform four different functions [48]: designer and planner, social (in the form of effective interpersonal communicator), pedagogical (as instructor), technological (as capable user of the learning management system), and managerial (as course administrator). More recent research [49] defines the roles of online faculty as those of facilitator, course designer, course manager, content matter expert, and mentor, which are on the same vein as those identified before [48]. While these skills might have become more common with the widespread use of online learning, still many faculty need specialized training. Outcomes-based curriculum and instructional delivery were mentioned by several administrator interviewees as absolutely essential to successful online learning experiences for students. Faculty need to be able to distinguish between “fun activities” and those that truly align with desired instructional outcomes. You cannot “just put a bunch of information up there”; the content has to be outcome driven.

Communication skills that online faculty need to possess include patience, quick feedback to students, excellent writing skills (given the greater reliance on asynchronous communication typical of online courses), being accommodating of individual student differences and needs, and being caring. A sincere commitment to making online instruction work is essential. According to one administrator, “we need instructors who believe that online learning is as good as face to face and are willing to do it”. Good instructor communication skills are of utmost importance given that research [50] has shown that frequent and effective student-instructor interaction is a big component of student success in online learning.

Possessing technology navigation skills is of course important for online instructors. At the same time, one interview participant emphasized that willingness to keep building one’s technology skills via ongoing professional development is also absolutely essential. Online faculty have to be willing to “advance incrementally” with regard to their technology skill set. In fact, in a study in which award-winning faculty were interviewed [49], willingness to learn and grow in both pedagogical and technical skills was the most mentioned topic by all the participants.

4.5. Administrative Support Provided to Online Faculty

Related to this importance of technology skills, administrators provide technology-related support to their faculty in a number of ways. Sometimes, at least pre-pandemic, this support took the form of real-time face-to-face technology help: “I take them to the computer myself”. Other forms of administrative technology support include connecting online faculty with a more experienced online faculty member as peer mentor. “I always made sure as provost that we could loop in distance-based faculty into faculty development activities”, stated another interview subject. Administrators also searched for ways to streamline faculty tasks via technology. One example shared was housing faculty applicant review files in a central repository accessible via a few clicks for faculty members in various locations throughout Arizona who are serving on faculty search committees. Additional ways that administrators help faculty with technology include pointing them to existing videos, training sessions, and contact persons in IT. “Being able to point faculty in the right direction” when they need technology-related help is an essential administrative responsibility, according to one interview subject. However, providing faculty mentors to new faculty, especially adjunct faculty, helps them feel connected to a community and improves their commitment to the university. These mentors should be in place not only for new adjunct faculty but also for existing faculty to help with retention and lessen faculty turnover [51].

“Helping faculty help their students with technology” is a related source of administrative support. One way to do this is to inform faculty of how students can contact the IT help desk if needed. At the same time, however, one interview subject cautioned that faculty should not have to be “the trainers of online students” themselves. Instead, faculty members should know how to point students in the right direction to get help with technology. It has been reported [52,53] that institutional support, in the forms of technology support and administrative support, is needed by both instructors and students. Instructors need support with course design, pedagogy, and administrative leadership, while students need support to learn how to be effective online learners.

Finally, caring and emotional support by administrators is an overarching skill in helping their online faculty fully maximize their effectiveness. Some ways the administrator interviewees do this is meeting one on one with online faculty, starting out new online faculty more slowly in online teaching to build their comfort zones, and encouraging a sense of community among the online faculty. Patience was once again mentioned, this time in assessing the teaching evaluations of new online faculty. Above all, as one administrative interviewee put it, “Helping their voice be heard and helping them feel valued” is absolutely essential. Administrative support also plays an important role in reducing faculty stress, increasing commitment to stay in the job, and improving faculty job satisfaction [54].

4.6. Adequacy of Instructional Design Support

Curricular and design support services received middling evaluations at best from the administrative interviewees. They acknowledged a staffing shortage in this area. “We just don’t have enough people to make our courses look really snazzy”, according to one subject.

Greater sensitivity to end users’ needs was also noted as a desired improvement in curricular design support. Possible generational differences in technology skills and comfort zones were mentioned as a potential issue. Administrative interviewees wished for more examples of what a quality online courses should look like from instructional design support services. Once again, outcomes-driven goals were key. Outcomes should drive the process of course design, instead of “just a bunch of information”. However, curricular and design support depends on great part on the institution. Some institutions provide almost no support to faculty resulting in them creating their own online courses as best as they can. On the other hand, institutions that use “outcomes-based curricula” may be more inclined to provide robust support to faculty in the form of access to specialized teams composed of subject matter experts, instructional designers, technologists, and even student learning center representatives [49].

4.7. Adequacy of Library Support

The majority of interview subjects rated library support as “excellent”. One administrator noted that the quality of library services has been exceptional for over two decades. Another noted that this excellence has been sustained even during times of budget cuts. Specific services that were praised included ease of access of journals including emailing entire journal articles to faculty and students upon request and ease of interlibrary loans, including discontinued direct-access journal materials.

At the same time, administrator interviewees pointed out several areas of desired improvement. One subject pointed out that students underutilize library services. Both faculty and students need to show greater initiative in reaching out to library services, according to another interviewee. One interview subject would like to see more library outreach to online students and faculty, as opposed to the library staff waiting for “self-generated interests” by students and faculty.

4.8. Administrative Evaluation of Online Faculty

One administrator noted that there are no major differences in faculty evaluation overall between the traditional face-to-face and online teaching setting: only the content and methods of meeting each objective may differ. However, as another interview subject pointed out, they “can’t as easily sit in on a class as walking to it” when attempting to evaluate online teaching performance.

Specific areas that administrators look at in assessing performance of their online faculty include course syllabi (particularly the clarity of syllabus expectations), responsiveness to students including timely provision of feedback on assignments, and overall student evaluation comments. Here, too there are some parallels to the face-to-face instructional evaluation process. The latter is “Not really very different than the results for in-person [instruction; we have] extremes of student reactions” in the student evaluation comments”. However, online faculty evaluation involves much more than what the participants noted. Some important aspects that should be considered when evaluating faculty performance in online courses are the course design, especially if it was created by the faculty and not by a central entity in the university, effectiveness of assignments in promoting student engagement, and timeliness of student feedback and student-instructor communication and interaction, among others [55].

4.9. Improvements Administrators Would Like to See in Online Faculty

One area where administrators think online faculty could do better is in curricular content. For one thing, administrators would like online faculty to find ways to add their own individual personal touches to an online course, as opposed to using “off the shelf course packages that could be taught by a robot”. Another area needing improvement is for faculty to take initiative to keep their course content fresh. “Sometimes I see the same course shell repeated and repeated”.

Clear communication with students was also singled out for desired improvement. One administrator mentioned that the grade book needs to be kept current so that students can always see where they stand. (This was not the case for this particular administrator’s own nephew in his online course). Once again, prompt responsiveness to students with helpful feedback on their course deliverables (assignments, discussions, messages to the instructor) could be better. Faculty also need to mentor their own students more effectively in such areas as online communication netiquette. One example is order of speaking during live Zoom sessions. In a recent study [56], both faculty and alumni identified that holding students to high standards of performance, ethical behavior, and appropriate professional conduct were extremely important to foster student learning. It was also argued that online students need faculty who are effective and constant communicators who promote student-instructor interaction to elicit timely responses and submission of assignments.

Another communication issue was clear communication between administrators and faculty regarding instructional expectations. One subject acknowledged that expectations regarding instructor presence in the online classroom may not always be clear. This is one area where administrators can better support their faculty.

Once again, greater facilitation of community among fellow faculty could result in improved skills and teaching efficiencies. There should be more sharing of courses and online instructional materials among instructional peers.

4.10. What Do Administrators See as the Future of Online Teaching and Learning?

The administrative interview subjects envision even more interactivity in future online learning spaces. This interactivity also includes more blended courses that combine the best of real-time interaction and convenience of online learning.

4.11. How Administrators Can Continue to Facilitate Positive Change in Online Instruction

One interview subject emphasized the need to “celebrate the positives” of online learning. This administrator felt too much emphasis was given only to negative aspects of the online classroom, without a balanced commensurate focus on its benefits. This is one area where administrators can lead the way in providing this balanced perspective to faculty and students.

5. Conclusions

Through identified themes and quotes, the researchers aimed to answer the question “What are administrators’ experiences and responsibilities as they relate to online instruction related to the areas of: course management, learner objectives and outcomes, social interactions and technology requirements?” Administrators are in a privileged position where they can take the lead and model the way to encourage greater interaction among online faculty. We should “avoid getting balkanized”, according to one interviewee. Administrators need to brainstorm ways to “promote richer exchange of ideas among dispersed participants”, as is the case with geographically dispersed faculty and students throughout Arizona. More traditional ways to encourage more of this dialogue include lunch and learn presentations on various aspects of online teaching and learning, as well as including online instructional assistance on faculty meeting agendas. One administrator interviewee encouraged reminding faculty that participation in such activities, including professional development opportunities offered by IT or curricular support services, counts towards their annual evaluation review submissions. Faculty need to be encouraged to “do more [and] be more” in terms of the importance of their ongoing professional development.

The second research question, “What are the benefits and challenges of offering courses and degree programs online?” identified several benefits, such as convenience, 24/7 classroom availability, avoiding relocation, etc. However, issues of equity of access for students and faculty continue to take center stage and should remain as administrative priorities. The digital divide is still a barrier, particularly in many remote regions of Arizona. Administrators need to be proactive in seeking new and more effective ways for technology to reach distantly located students and faculty.

Administrators also need to stay current regarding valid assessment processes such as the Quality Matters criteria. This will help them conduct meaningful evaluations of online instructional initiatives as part of their program offerings.

Finally, administrators should extend the same caring human touch to their online faculty as they expect the faculty to extend to their own students. “Helping people not fear” (online teaching and learning) is vitally important. “We are all someplace and incrementally we can get there”.

This final quote from an administrator interview subject says it all in terms of future leadership vision regarding online teaching and learning. “We are on a continuum and… we are someplace on it and extending a handout to someone who might not be where I am yet or you, extending your hand out to me because I’m not where you are. And me grabbing hold of that.”

6. Limitations of the Study

The study was conducted with administrators at a college of education. The findings may not necessarily be applicable to administrators of other content areas of teaching and learning.

Interviews conducted via technology, such as Zoom, allow limited visibility of non-verbal cues and body language that could further supplement the spoken interview comments of a live-and-in-person interview session.

Individual interviews did not allow for interaction and exchange of perspectives among the administrator participants. This interaction, such as in a focus group interview format, would have allowed researchers to further confirm any areas of agreement or disagreement among administrator interview subjects.

The single interview session, while expedient for busy administrators, did not allow for follow-up interview sessions to probe for more details regarding initial interview responses.

The interviews took place shortly after the pandemic lockdown and sudden move to online instruction. This significant external event may have influenced administrators’ perceptions and responses in atypical directions not necessarily reflective of non-pandemic times.

7. Implications for Future Research

Since interviews were conducted with a small sample size of educational leaders, a follow-up study utilizing much larger sampling of leaders would be appropriate. Additionally, the initial interviews were conducted in March, April, and May of 2020, at the beginning of the COVID -19 pandemic. During this initial interview timeframe, all educational institutions were developing strategies and plans, searching for ways to effectively educate their students, as well as reinventing course delivery with the elimination of in-person instruction. It would be valuable to reinterview the original interviewees to determine what has changed in their thinking over the last year. What lessons were learned? What perceptions have changed? How has the last year changed their administrative perceptions regarding supervision of online learning and teaching?

If as noted previously, “We are on a continuum”, and possibly at the beginning stages of this continuum, in understanding the true details of what is required of leadership in the administration of online learning, it would be appropriate to replicate this study in a year, two years, or five years.

The present study illuminates the strategies that higher education administrators in this specific institution use to manage online programs. However, the lessons learned from this study need to find their way toward administrators in the K-12 setting, especially because basic education classrooms found themselves conducting their business in online environments due to the pandemic. A future study that will target K-12 administrators (principals, assistant principals, etc.) is already in the planning stages to find best practices that will benefit both higher education and K-12 administrators. Future research into on-line teaching and learning should specifically address the various types of support which administrators should provide to faculty and students for effective online instruction. This research should include the areas of professional development for faculty, online learning-strategies for students, identification of skill levels and dispositions for faculty, and minimum levels of computer hard hardware and software, along with corresponding technical support.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.D.; methodology, M.D. and L.S.-M.; formal analysis, M.D.; investigation, M.S., M.D. and L.S.-M.; writing—original draft preparation, M.S., M.D., and L.S.-M.; writing—review and editing, M.D. and L.S.-M.; project administration, M.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Review Board of Northern Arizona University, Project Title: [1557581-2], approved 24 March 2020.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to participant privacy issues.

Conflicts of Interest

Two of the contributing authors also served as participants because of the administrative positions they held or hold.

References

- Xie, K.; Vongkulluksn, V.W.; Justice, L.M.; Logan, J.A. Technology acceptance in context: Preschool teachers’ integration of a technology-based early language and literacy curriculum. J. Early Child. Teach. Educ. 2019, 40, 275–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NCES. Student Access to Digital Learning Resources Outside of the Classroom. National Center for Education Statistics, 2018. Available online: https://nces.ed.gov/pubs2017/2017098/index.asp (accessed on 5 February 2021).

- NCES. Measuring School Climate using the 2015 School Crime Supplement: Technical Report. National Center for Education Statistics, 2018. Available online: https://nces.ed.gov/pubs2018/2018098.pdf (accessed on 5 February 2021).

- Singh, V.; Thurman, A. How many ways can we define online learning? A systemic literature review of definitions of online learning 1988–2018. Am. J. Distance Educ. 2019, 33, 289–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, I.E.; Seaman, J. Grade Level: Tracking Online Education in the United States; Babson Survey Research Group: Babson Park, MA, USA, 2015. Available online: https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED572778.pdf (accessed on 2 February 2021).

- National Center for Education Statistics. Integrated Postsecondary Education Data System; National Center for Education Statistics: Washington, DC, USA, 2016. Available online: https://nces.ed.gov/ipeds/use-the-data (accessed on 21 October 2021).

- Allen, I.E.; Seaman, J. Online Report Card: Tracking Online Education in the United States; Babson Survey Research Group: Babson Park, MA, USA, 2016; Available online: https://onlinelearningsurvey.com/reports/onlinereportcard.pdf (accessed on 17 February 2021).

- Seaman, J.; Allen, I.E.; Seaman, J. Grade Increase: Tracking Distance Education in the United States; Babson Survey Research Group: Babson Park, MA, USA, 2018; Available online: http://www.onlinelearningsurvey.com/highered.html (accessed on 17 February 2021).

- Palvia, S.; Aeronb, P.; Guptab, P.; Mahapatrac, D.; Paridac, R.; Rosnera, R.; Sindhi, S. Online education: Worldwide status, challenges, trends, and implications. J. Glob. Inf. Technol. Manag. 2018, 21, 233–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pardino, A.; Gleyz-er, I.; Javed, I.; Reid-Hector, J.; Heuer, A. The best pedagogical practices in graduate online learning: A systematic review. Creat. Educ. 2018, 1123–1144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexander, R.C. Establishing an administrative structure for online programs. Int. J. Instr. Technol. Distance Learn. 2015, 12, 49–55. Available online: https://itdl.org/Journal/Jun_15/Jun15.pdf#page=53 (accessed on 10 March 2021).

- Willcox, K.E.; Sarma, S.; Lippel, P.H. Online Education: A Catalyst for Higher Education Reforms. 2016. Available online: https://sites.nationalacademies.org/cs/groups/pgasite/documents/webpage/pga_171687.pdf (accessed on 21 October 2021).

- Xu, D.; Xu, Y. The Promises and Limits of Online Higher Education: Understanding How Distance Education Affects Access, Cost, and Quality; American Enterprise Institute: Washington, DC, USA, 2019; Available online: https://www.aei.org/research-products/report/the-promises-and-limits-of-online-higher-education/ (accessed on 7 May 2021).

- Özcan, H.; Yıldırım, S. Administrators’ perceptions of motives to offer online academic degree programs in universities. Int. Rev. Res. Open Distrib. Learn. 2018, 19, 327–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popovich, C.J.; Neel, R.E. Characteristics of distance education programs at accredited business schools. Am. J. Distance Educ. 2005, 19, 229–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.; Chang, H.; Bryan, L. Doctoral students’ learning success in online-based leadership programs: Intersection with technological and relational factors. Int. Rev. Res. Open Distrib. Learn. 2020, 21, 61–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandernach, J.; Register, L.; O’Donnell, C. Characteristics of adjunct faculty teaching online: Institutional implications. Online J. Distance Learn. Adm. 2015, 18, 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, A.; Chen, X. Online education and its effective practice: A research review. J. Inf. Technol. Educ. Res. 2016, 15, 157–190. Available online: http://www.informingscience.org/Publications/3502 (accessed on 20 March 2021). [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, S.W.; Tschida, C.M.; Hodge, E.M. How faculty learn to teach online: What administrators need to know. Online J. Distance Learn. Adm. 2015, 19, 1–10. Available online: https://www.westga.edu/~distance/ojdla/spring191/schmidt_tschida_hodge191.pdf (accessed on 3 April 2021).

- Wingo, N.P.; Ivankova, N.V.; Moss, J.A. Faculty perceptions about teaching online: Exploring the literature using the tech-nology acceptance model as an organizing framework. Online Learn. 2017, 21, 15–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scherer, R.; Howard, S.K.; Tondeur, J.; Siddiq, F. Profiling teachers’ readiness for online teaching and learning in higher education: Who’s ready? Comput. Hum. Behav. 2020, 118, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatlevik, O.E. Examining the relationship between teachers’ self-efficacy, their digital competence, strategies to evaluate information, and use of ICT at school. Scand. J. Educ. Res. 2017, 61, 555–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kebritchi, M.; Lipschuetz, A.; Santiague, L. Issues and challenges for teaching successful online courses in higher education: A literature review. J. Educ. Technol. Syst. 2017, 46, 4–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Protopsaltis, S.; Baum, S. Does online education live up to its promise? A look at the evidence and implications for federal policy. Cent. Educ. Policy Eval. 2019. Available online: https://jesperbalslev.dk/wp-content/uploads/2020/09/OnlineEd.pdf (accessed on 9 February 2021).

- Baum, S.; McPherson, M. The human factor: The promise limits of online education. Daedalus 2019, 148, 235–254. Available online: https://direct.mit.edu/daed/article/148/4/235/27283/The-Human-Factor-The-Promise-amp-Limits-of-Online (accessed on 16 January 2021). [CrossRef]

- Elliott, M.; Rhoades, N.; Jackson, C.M.; Mandernach, B.J. Professional development: Designing initiatives to meet the needs of online faculty. J. Educ. Online 2015, 12, 160–188. Available online: https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1051031.pdf (accessed on 3 April 2021). [CrossRef]

- Guan, S.; Stanford, D. Learner and faculty support. New Dir. High. Educ. 2016, 173, 65–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stein, S.J.; Anderson, B. Hidden aspects of administration: How scale changes the role of a distance education adminis-trator. Online J. Distance Learn. Adm. 2017, 20. Available online: https://www.westga.edu/~distance/ojdla/winter204/stein_anderson204.html (accessed on 26 March 2021).

- Santelli, B.; Stewart, K.; Mandernach, J. Supporting high quality teaching in online programs. J. Educ. Online 2020, 17, n1. Available online: https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1241555.pdf (accessed on 10 May 2021).

- Jackson, N.C. Managing for competency with innovation change in higher education: Examining the pitfalls and pivots of digital transformation. Bus. Horiz. 2019, 62, 761–772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merriam, S.; Tisdell, E. Qualitative Research: A Guide to Design and Implementation, 4th ed.; John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Kozleski, E.B. The uses of qualitative research: Powerful methods to inform evidence-based practice in education. Res. Pract. Pers. Sev. Disabil. 2017, 42, 19–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alajmi, A.; Worthington, A.C. Qualitative Insights into Corporate Governance Reform, Management Decision-Making, and Accounting Performance Semi-Structured Interview Evidence. 2021. Available online: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3884667 (accessed on 20 March 2021). [CrossRef]

- Lemon, L.L.; Hayes, J. Enhancing trustworthiness of qualitative findings: Using Leximancer for qualitative data analysis triangulation. Qual. Rep. 2020, 25, 604–614. [Google Scholar]

- Marshall, C.; Rossman, G.; Blanco, G. Designing Qualitative Research, 7th ed.; Sage Publications, Inc.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Gray, L.M.; Wong-Wylie, G.; Rempel, G.R.; Cook, K. Expanding qualitative research interviewing strategies: Zoom video communications. Qual. Rep. 2020, 25, 1292–1301. [Google Scholar]

- Archibald, M.M.; Ambagtsheer, R.C.; Casey, M.G.; Lawless, M. Using zoom videoconferencing for qualitative data collection: Perceptions and experiences of researchers and participants. Int. J. Qual. Methods 2019, 18, 1609406919874596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiger, M.E.; Varpio, L. Thematic Analysis of Qualitative Data: AMEE Guide No. 131. Med. Teach. 2020, 42, 846–854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patton, M.Q. Qualitative Research & Evaluation Methods: Integrating Theory and Practice, 4th ed.; SAGE Publications, Inc.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2015; ISBN 978-1-4129-7212-3. [Google Scholar]

- Rao, K.; Eady, M.; Edelen-Smith, P. Creating Virtual Classrooms for Rural and Remote Communities. Phi Delta Kappan 2011, 92, 22–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parkes, M.; Gregory, S.; Fletcher, P.; Adlington, R.; Gromik, N. Bringing people together while learning apart: Creating online learning environments to support the needs of rural and remote students. Aust. Int. J. Rural. Educ. 2015, 25, 66–78. [Google Scholar]

- Peterson, A.T.; Beymer, P.N.; Putnam, R.T. Synchronous and asynchronous discussions: Effects on cooperation, belonging, and affect. Online Learn. 2018, 22, 7–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akhtar, S.; Warburton, S.; Xu, W. The Use of an Online Learning and Teaching System for Monitoring Computer Aided Design Student Participation and Predicting Student Success. Int. J. Technol. Des. Educ. 2017, 27, 251–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, F.P. An analysis of synchronous and asynchronous communication tools in e-learning. Adv. Sci. Technol. Lett. 2017, 143, 230–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Limperos, A.M.; Buckner, M.M.; Kaufmann, R.; Frisby, B.N. Online Teaching and Technological Affordances: An Experimental Investigation into the Impact of Modality and Clarity on Perceived and Actual Learning. Comput. Educ. 2015, 83, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watts, L. SYNCHRONOUS AND ASYNCHRONOUS COMMUNICATION IN DISTANCE LEARNING: A Review of the Literature. Q. Rev. Distance Educ. 2016, 17, 23–32. [Google Scholar]

- Martin, F.; Budhrani, K.; Wang, C. Examining Faculty Perception of Their Readiness to Teach Online. OLJ 2019, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, F.; Ritzhaupt, A.; Kumar, S.; Budhrani, K. Award-Winning Faculty Online Teaching Practices: Course Design, Assessment and Evaluation, and Facilitation. Internet High. Educ. 2019, 42, 34–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaggars, S.S.; Xu, D. How Do Online Course Design Features Influence Student Performance? Comput. Educ. 2016, 95, 270–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearson, M.J.; Kirby, E.G. An Online Mentoring Model That Works. Fac. Focus. 2020. Available online: https://www.facultyfocus.com/articles/online-education/an-online-mentoring-model-thatworks/ (accessed on 1 May 2021).

- Martin, F.; Sun, T.; Westine, C.D. A Systematic Review of Research on Online Teaching and Learning from 2009 to 2018. Comput. Educ. 2020, 159, 104009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McGee, P.; Windes, D.; Torres, M. Experienced Online Instructors: Beliefs and Preferred Supports Regarding Online Teaching. J. Comput. High. Educ. 2017, 29, 331–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aldosiry, N.S. The influence of support from administrators and other work conditions on special education teachers. Int. J. Disabil. Dev. Educ. 2020, 67, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soffer, T.; Kahan, T.; Livne, E. E-Assessment of Online Academic Courses via Students’ Activities and Perceptions. Stud. Educ. Eval. 2017, 54, 83–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanis, C.J. The seven principles of online learning: Feedback from faculty and alumni on its importance for teaching and learning. Res. Learn. Technol. 2020, 28, 2319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).