Quantitative Ethnobotanical Analysis of Medicinal Plants of High-Temperature Areas of Southern Punjab, Pakistan

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

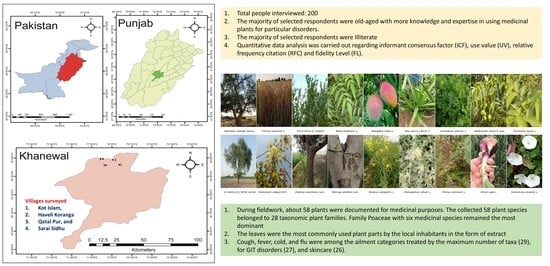

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Field Surveys and Data Collection

2.3. Inventory

2.4. Ethical Consideration

2.5. Quantitative Ethnobotany

2.5.1. Informant Consensus Factor

2.5.2. Use Value

2.5.3. Relative Frequency Citation

2.5.4. Fidelity Level

2.6. Data Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Demographic Characteristics of Respondents

3.2. Health Issues

3.3. Medicinal Plant Diversity

3.4. Medicinal Plant Parts Used for the Treatment of Diseases

3.5. Mode of Utilization

3.6. Number of Taxa Curing or Treating Ailment Categories

3.7. Quantitative Data Analysis

3.7.1. Informant Consensus Factor

3.7.2. Use Value

3.7.3. Relative Frequency Citation

3.7.4. Fidelity Level

3.8. Ethnopharmacological Relevance

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Ethics Approval and Consent to Participate

References

- Sardar, A.A.; Zaheer-Ud-Din, K. Ethnomedicinal studies on plant resources of tehsil Shakargarh, district Narowal, Pakistan. Pak. J. Bot. 2009, 41, 11–18. [Google Scholar]

- Zahoor, M.; Yousaf, Z.; Aqsa, T.; Haroon, M.; Saleh, N.; Aftab, A.; Javed, S.; Qadeer, M.; Ramazan, H. An ethnopharmacological evaluation of Navapind and Shahpur Virkanin district Sheikupura, Pakistan for their herbal medicines. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2017, 13, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shah, S.; Khan, S.; Bussmann, R.W.; Ali, M.; Hussain, D.; Hussain, W. Quantitative ethnobotanical study of indigenous knowledge on medicinal plants used by the tribal communities of gokand valley, district buner, Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, Pakistan. Plants 2020, 9, 1001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awan, A.A.; Akhtar, T.; Ahmed, M.J.; Murtaza, G. Quantitative ethnobotany of medicinal plants uses in the Jhelum valley, Azad Kashmir, Pakistan. Acta Ecol. Sin. 2021, 41, 88–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omotayo, A.O.; Ndhlovu, P.T.; Tshwene, S.C.; Aremu, A.O. Utilization pattern of indigenous and naturalized plants among some selected rural households of north west province, South Africa. Plants 2020, 9, 953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silva, F.D.S.; Ramos, M.A.; Hanazaki, N.; Albuquerque, U.P.D. Dynamics of traditional knowledge of medicinal plants in a rural community in the Brazilian semi-arid region. Rev. Brasil. Farmacogn. 2011, 21, 382–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arshad, M.; Ahmad, M.; Ahmed, E.; Saboor, A.; Abbas, A.; Sadiq, S. An ethnobiological study in Kala Chitta hills of Pothwar region, Pakistan: Multinomial logit specification. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2014, 10, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Karous, O.; Ben Haj Jilani, I.; Ghrabi-Gammar, Z. Ethnobotanical study on plant used by Semi-Nomad Descendants’ community in Ouled Dabbeb—Southern Tunisia. Plants 2021, 10, 642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ambu, G.; Chaudhary, R.P.; Mariotti, M.; Cornara, L. Traditional uses of medicinal plants by ethnic people in the Kavrepalanchok district, central Nepal. Plants 2020, 9, 759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mesfin, F.; Demissew, S.; Teklehaymanot, T. An ethnobotanical study of medicinal plants in WonagoWoreda, SNNPR, Ethiopia. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2009, 5, 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Vitalini, S.; Iriti, M.; Puricelli, C.; Ciuchi, D.; Segale, A.; Fico, G. Traditional knowledge on medicinal and food plants used in Val San Giacomo (Sondrio, Italy) an alpine ethnobotanical study. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2013, 145, 517–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yaseen, G.; Ahmad, M.; Sultana, S.; Alharrasi, A.S.; Hussain, J.; Zafar, M.; Rehmanc, S.-U. Ethnobotany of medicinal plants in the Thar Desert (Sindh) of Pakistan. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2015, 163, 43–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agisho, H.; Osie, M.; Lambore, T. Traditional medicinal plants utilization, management and threats in hadiya zone, Ethiopia. J. Med. Plants Stud. 2014, 2, 94–108. [Google Scholar]

- Raskin, I.; Ripoll, C. Can an apple a day keep the doctor away? Curr. Pharm. Des. 2004, 10, 3419–3429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhal, N.K.; Panda, S.S.; Muduli, S.D. Traditional uses of medicinal plants by native people in Nawarangpur district, Odisha, India. Asian J. Plant Sci. 2015, 5, 27–33. [Google Scholar]

- Adnan, M.; Ullah, I.; Tariq, A.; Murad, W.; Azizullah, A.; Latif Khan, A.L.; Ali, N. Ethnomedicine use in the war-affected region of northwest Pakistan. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2014, 10, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Amiri, M.S.; Joharchi, M.R. Ethnobotanical investigation of traditional medicinal plants commercialized in the markets of Mashhad, Iran. Avicenna J. Phytomed. 2013, 3, 254. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Farnsworth, N.R. Screening plants for new medicines. In Biodiversity; Wilson, E.O., Peter, F.M., Eds.; The National Academies Press: Washington, DC, USA, 1988; pp. 83–97. [Google Scholar]

- Umair, M.; Altaf, M.; Bussmann, R.W.; Abbasi, A.M. Ethnomedicinal uses of the local flora in Chenab riverine area, Punjab province Pakistan. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2019, 15, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Hamayun, M. Ethnobotanical studies of some useful shrubs and trees of district Buner, NWFP, Pakistan. Ethnobot. Leafl. 2003, 12, 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Akram, M.; Siddiqui, M.I.; Akhter, N.; Waqas, M.K.; Iqbal, Z.; Akram, M.; Khan, A.A.; Madni, A.; Asif, H.M. Ethnobotanical survey of common medicinal plants used by people of district Sargodha, Punjab, Pakistan. J. Med. Plants Res. 2011, 5, 7073–7075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Umair, M.; Altaf, M.; Abbasi, A.M. An ethnobotanical survey of indigenous medicinal plants in Hafizabad district, Punjab-Pakistan. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0177912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Usman, M.; Murtaza, G.; Ditta, A.; Bakht, T.; Asif, M.; Nadir, M.; Nawaz, S. Distribution pattern of weeds in wheat crop grown in District Khanewal, Punjab, Pakistan. Pak. J. Weed Sci. Res. 2020, 26, 47. [Google Scholar]

- Gilani, M.H. Historical Background of Saraiki Language. Pak. J. Soc. Sci. 2013, 33, 61–76. [Google Scholar]

- Nasir, E.; Ali, S.I. Flora of Pakistan; Department of Botany, University of Karachi: Islamabad, Pakistan; Agricultural Research Council: Islamabad, Pakistan, 1974–1991. [Google Scholar]

- Stewart, R.R. An Annotated Catalog of Vascular Plants of West Pakistan and Kashmir; Fakhri Printing Press: Karachi, Pakistan, 1972. [Google Scholar]

- Heinrich, M.; Ankli, A.; Frei, B.; Weimann, C.; Sticher, O. Medicinal plants in Mexico: Healers’ consensus and cultural importance. Soc. Sci. Med. 1998, 47, 1859–1871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canales, M.; Hernandez, T.; Caballero, J.; Vivar, A.; Avila, G.; Duran, A.; Lira, R. Informant consensus factor and antibacterial activity of the medicinal plants used by the people of San Rafael Coxcatlán, Puebla, México. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2005, 97, 429–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tardio, J.; Pardo-de-Santayana, M. Cultural importance indicates: A comparative analysis based on the useful wild plants of Southern Cantabria (Northern Spain). Econ. Bot. 2008, 62, 24–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trotter, R.T.I.I.; Logan, M.; Trotter, R.T.; Logan, M.H. Informant consensus: A new approach for identifying potentially effective medicinal plants. In Plants in Indigenous Medicine & Diet; Routledge: London, UK, 1986; pp. 91–112. [Google Scholar]

- Bano, A.; Ahmad, M.; Hadda, T.B.; Saboor, A.; Sultana, S.; Zafar, M.; Khan, M.P.Z.; Arshad, M.; Ashraf, M.A. Quantitative ethnomedicinal study of plants used in the Skardu valley at high altitude of Karakoram-Himalayan range, Pakistan. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2014, 10, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bennett, B.C.; Prance, G.T. Introduced plants in the indigenous pharmacopoeia of Northern South America. Econ. Bot. 2000, 54, 90–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lulekal, E.; Asfaw, Z.; Kelbessa, E.; Van Damme, P. Ethnomedicinal study of plants used for human ailments in Ankober District, North Shew Zone, Amhara region. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2013, 9, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Bibi, T.; Ahmad, M.; Tareen, R.B.; Tareen, N.M.; Jabeen, R.; Rehman, S.-U.; Sultana, S.; Zafar, M.; Yaseen, G. Ethnobotany of medicinal plants in district Mastung of Balochistan province, Pakistan. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2014, 157, 79–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khan, T.Y.; Badshah, L.; Ali, A. Ethnobotanical survey of some important medicinal plants of area Mandan district Bannu, Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, Pakistan. Int. J. Herb. Med. 2018, 6, 15–21. [Google Scholar]

- Giday, M.; Asfaw, Z.; Woldu, Z. Medicinal plants of the Meinit ethnic group of Ethiopia: An ethnobotanical study. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2009, 124, 513–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kadir, M.F.; Bin Sayeed, M.S.; Mia, M. Ethnopharmacological survey of medicinal plants used by traditional healers in Bangladesh for gastrointestinal disorders. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2013, 147, 148–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ayyanar, M.; Ignacimuthu, S. Ethnobotanical survey of medicinal plants commonly used by Kani tribals in Tirunelveli hills of Western Ghats, India. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2011, 134, 851–864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kunle, O.F.; Egharevba, H.O.; Ahmadu, P.O. Standardization of herbal medicines—A review. Biodivers. Conserv. 2012, 4, 101–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, A.; Marwat, S.K.; Gohar, F.; Khan, A.; Bhatti, K.H.; Amin, M.; Din, N.U.; Ahmad, M.; Zafar, M. Ethnobotanical study of medicinal plants of semi-tribal area of Makerwal and GullaKhel (lying between Khyber Pakhtunkhwa and Punjab provinces), Pakistan. Am. J. Plant Sci. 2013, 4, 98–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gurdal, B.; Kultur, S. An ethnobotanical study of medicinal plants in Marmaris (Mŭgla, Turkey). J. Ethnopharmacol. 2013, 146, 113–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, M.; Shazia, S.; Fazl-i-Hadi, S.; Hadda, T.B.; Rashid, S.; Zafar, M.; Khan, M.A.; Khan, M.P.Z.; Yaseen, G. An ethnobotanical study of medicinal plants in high mountainous region of Chail valley (District Swat-Pakistan). J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2014, 10, 1–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Towfik, I.A.; Hamza, S.S.; Munahi, A. The effect of Henna (Lawsonia inermis) on the wound healing of local Arabian horses. J. Kerbala Uni. 2014, 10, 78–91. [Google Scholar]

- Mahmood, A.; Ahmad, M.; Zafar, M.; Nadeem, S. Pharmacognostic studies of some indigenous medicinal plants of Pakistan. Ethnobot. Leafl. 2005, 2004, 3. [Google Scholar]

- Hassan, N.; Din, M.U.; Shuaib, M.; Ul-Hassan, F.; Zhu, Y.; Chen, Y.; Nisar, M.; Iqbal, I.; Zada, P.; Iqbal, A. Quantitative analysis of medicinal plants consumption in the highest mountainous region of Bahrain Valley, Northern Pakistan. Ukrainian J. Ecol. 2019, 9, 35–49. [Google Scholar]

- Jha, P.; Mohapatra, K.P. Leaf litterfall, fine root production and turnover in four major tree species of the semi-arid region of India. Plant Soil 2010, 326, 481–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliver, S.J. The role of traditional medicine practice in primary health care within aboriginal Australia: A review of the literature. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2013, 9, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Kamalebo, H.M.; Malale, H.N.S.W.; Ndabaga, C.M.; Degreef, J.; Kesel, A.D. Uses and importance of wild fungi: Traditional knowledge from the Tshopo province in the Democratic Republic of the Congo. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2018, 4, 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Kanwal, H.; Sherazi, B.A. Herbal medicine: Trend of practice, perspective, and limitations in Pakistan. Asian Pac. J. Health Sci. 2017, 4, 6–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrakoua, K.; Iatroub, G.; Lamari, F.N. Ethnopharmacological survey of medicinal plants traded in herbal markets in the Peloponnisos, Greece. J. Herb. Med. 2020, 19, 100305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jabbar, A.; Raza, M.A.; Iqbal, Z.; Khan, M.N. An inventory of the ethnobotanicals used as anthelmintics in southern Punjab (Pakistan). J. Ethnopharmacol. 2006, 108, 152–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmad, K.S.; Hamid, A.; Nawaz, F.; Hameed, M.; Ahmad, F.; Deng, J.; Akhtar, N.; Wazarat, A.; Mahroof, S. Ethnopharmacological studies of indigenous plants in Kel village, Neelum Valley, Azad Kashmir, Pakistan. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2017, 13, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ouelbani, R.; Bensari, S.; Mouas, T.N.; Khelifi, D. Ethnobotanical investigations on plants used in folk medicine in the regions of Constantine and Mila (North-East of Algeria). J. Ethnopharmacol. 2016, 194, 196–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tuasha, N.; Petros, B.; Asfaw, Z. Medicinal plants used by traditional healers to treat malignancies and other human ailments in Dalle District, Sidama Zone, Ethiopia. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2018, 14, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Ahmed, N.; Mahmood, A.; Mahmood, A.; Sadeghi, Z.; Farman, M. Ethnopharmacological importance of medicinal flora from the district of Vehari, Punjab province, Pakistan. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2015, 168, 66–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Badar, N.; Iqbal, Z.; Sajid, M.S.; Rizwan, H.M.; Jabbar, A.; Babar, W.; Khan, M.N.; Ahmed, A. Documentation of ethnoveterinary practices in district Jhang, Pakistan. J. Anim. Plant Sci. 2017, 27, 398–406. [Google Scholar]

- Abbasi, A.M.; Khan, M.A.; Zafar, M. Ethno-medicinal assessment of some selected wild edible fruits and vegetables of Lesser-Himalayas, Pakistan. Pak. J. Bot. 2013, 45, 215–222. [Google Scholar]

- Qureshi, R.; Ain, Q.; Ilyas, M.; Rahim, G.; Ahmad, W.; Shaheen, H.; Ullah, K. Ethnobotanical study of Bhera, district Sargodha, Pakistan. Arch. Des Sci. 2012, 65, 690–707. [Google Scholar]

- Nisar, M.; Ali, Z. Ethnobotanical wealth of Jandool valley, dir lower, Khyber Pakhtunkhwa (KPK), Pakistan. Int. J. Phytomed. 2012, 4, 351. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, V.P.; Prashanth, K.H.; Venkatesh, Y.P. Structural analyses and immunomodulatory properties of fructo-oligosaccharides from onion (Allium cepa). Carbohydr. Polym. 2015, 117, 115–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meena, A.K.; Singh, B.; Niranjan, U.; Yadav, A.K.; Nagaria, A.K.; Gaurav, A.; Singh, R. A review on A. nilotica Linn. and it’s ethnobotany, phytochemical and pharmacological profile. Res. J. Sci. Technol. 2010, 2, 67–71. [Google Scholar]

- Khosla, P.; Bhanwra, S.; Singh, J.; Seth, S.; Srivastava, R.K. A study of hypoglycaemic effects of Azadirachta indica (Neem) in normal and alloxan diabetic rabbits. Indian J. Physiol. Pharmacol. 2000, 44, 69–74. [Google Scholar]

- Sharma, A.; Kumari, M.; Jagannadham, M.V. Religiosin C, a cucumisin-like serine protease from Ficus religiosa. Process Biochem. 2012, 47, 914–921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alamgeer, T.A.; Rashid, M.; Malik, M.N.H.; Mushtaq, M.N. Ethnomedicinal survey of plants of valley alladand dehri, tehsil Batkhela, district Malakand, Pakistan. Int. J. Basic Medical Sci. Pharm. 2013, 3, 23–32. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, K.S.; Bhowmik, D.; Chiranjib, B.; Tiwari, P. Allium cepa: A traditional medicinal herb and its health benefits. J. Chem. Pharm. Res. 2010, 2, 283–291. [Google Scholar]

- Shafiq, S.; Shakir, M.; Ali, Q. Medicinal uses of onion (Allium cepa L.): An overview. Life Sci. J. 2017, 14, 100–107. [Google Scholar]

- Valerio, F.; Mezzapesa, G.N.; Ghannouchi, A.; Mondelli, D.; Logrieco, A.F.; Perrino, E.V. Characterization and antimicrobial properties of essential oils from four wild taxa of Lamiaceae family growing in Apulia. Agronomy 2021, 11, 1431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perrino, E.V.; Valerio, F.; Gannouchi, A.; Trani, A.; Mezzapesa, G. Ecological, and plant community implication on essential oils composition in useful wild officinal species: A pilot case study in Apulia (Italy). Plants 2021, 10, 574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perrino, E.V.; Perrino, P. Crop wild relatives: Know how past and present to improve future research, conservation, and utilization strategies, especially in Italy: A review. Resour. Crop Evol. 2020, 67, 1067–1105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maxted, N.; Dulloo, M.E.; Ford-Lloid, B.V.; Frese, L.; Iriondo, J.; Pinheiro de Carvallho, M.A.A. Agrobiodiversity Conservation Securing the Diversity of Crop Wild Relatives and Landraces; CAB International: Wallingford, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Maxted, N.; Kell, S. Establishment of a global network for the in situ conservation of crop wild relatives: Status and needs. Study Pap. 2009, 39, 1–224. [Google Scholar]

| Variation | Category | Number | Percentage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 125 | 62.5% |

| Female | 74 | 37.0% | |

| Other | 01 | 0.5% | |

| Age | Less than 30 | 11 | 5.5% |

| 30–40 | 15 | 7.5% | |

| 40–50 | 32 | 16.0% | |

| 50–60 | 37 | 18.5% | |

| 60–70 | 43 | 21.5% | |

| Over 70 | 62 | 31.0% | |

| Marital status | Unmarried | 26 | 13.0% |

| Married | 174 | 87.0% | |

| Educational background | Illiterate | 171 | 85.5% |

| Primary | 12 | 6.0% | |

| Middle | 07 | 3.5% | |

| Secondary | 05 | 2.5% | |

| Higher secondary | 03 | 1.5% | |

| University | 02 | 1.0% |

| Sr. No. | Family | Number of Medicinal Plants |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Poaceae | 6 |

| 2 | Asteraceae | 5 |

| 3 | Solanaceae | 5 |

| 4 | Brassicaceae | 4 |

| 5 | Fabaceae | 4 |

| 6 | Lamiaceae | 3 |

| 7 | Moraceae | 3 |

| 8 | Amaranthaceae | 2 |

| 9 | Amaryllidaceae | 2 |

| 10 | Apiaceae | 2 |

| 11 | Chenopodiaceae | 2 |

| 12 | Convolvulaceae | 2 |

| 13 | Meliaceae | 2 |

| 14 | Myrtaceae | 2 |

| 15 | Anacardiaceae | 1 |

| 16 | Asphodelaceae | 1 |

| 17 | Apocynaceae | 1 |

| 18 | Boraginaceae | 1 |

| 19 | Combretaceae | 1 |

| 20 | Cucurbitaceae | 1 |

| 21 | Euphorbiaceae | 1 |

| 22 | Lythraceae | 1 |

| 23 | Moringaceae | 1 |

| 24 | Oxalidaceae | 1 |

| 25 | Primulaceae | 1 |

| 26 | Rhamnaceae | 1 |

| 27 | Rutaceae | 1 |

| 28 | Salvadoraceae | 1 |

| Ailment Categories | Nur | Nt | ICF |

|---|---|---|---|

| Wound healing | 103 | 14 | 0.87 |

| Skincare and nails, hair, and teeth disorders | 167 | 26 | 0.85 |

| GIT disorders (Diarrhea, constipation, stomach imbalance, cholera) | 156 | 27 | 0.83 |

| Muscular disorders (Rheumatism) | 89 | 19 | 0.79 |

| Diabetes | 78 | 19 | 0.77 |

| Eye problems | 17 | 05 | 0.75 |

| Cardiac disorders | 13 | 04 | 0.75 |

| Blood purification | 16 | 05 | 0.73 |

| Ulcer | 37 | 11 | 0.72 |

| Urinary disorders | 57 | 18 | 0.70 |

| Cough, cold, fever, flu | 89 | 29 | 0.68 |

| Sexual problems | 58 | 19 | 0.68 |

| Snake or mosquito bite | 14 | 06 | 0.61 |

| Respiratory disorders (asthma, tuberculosis) | 39 | 16 | 0.60 |

| S. No | Plant species with Specimen Name | Family | Vernacular Name | Plant Parts Used | Methods of Utilizations | Uses | UV | RFC | FL% |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Acacia nilotica (L.) Willd. ex Del. JP–454 * | Mimosaceae | Kekar | Leaves, roots, fruit, flowers, bark, gum, oil | Extract, decoction, powder | High blood pressure, liver problems, tuberculosis, sexual disorders, ulcer, wounds, common cold, diarrhea, toothache, pickle, fodder | 0.058 | 0.95 | 91.1 |

| 2 | Albizia lebbeck (L.) Benth. JP–414 | Fabaceae | sharaii | Leaves, flowers, bark, | Paste | Lungs disorders, diabetes, anti-inflammatory, cough, flu, eye care, diarrhea, piles | 0.11 | 0.35 | 60.0 |

| 3 | Allium cepa L. JP–421 | Amaryllidaceae | Ganda/Wasal | Bulb, shoots, flower | Extract, raw, decoction, paste | Diabetes, high blood pressure, asthma, sexual disorders in both sexes, dry cough, sore throat, hair loss, sleeplessness, appetite problems in cattle, wounds, cooking | 0.062 | 0.88 | 60.2 |

| 4 | Allium sativum L JP–379 | Amaryllidaceae | Thoum/Lehson | Bulb, leaves, flower | Extract, decoction, paste, raw, | Diabetes, High blood pressure, cardiac disorders, cough, fever, toothache, skin problems, tuberculosis, cooking | 0.058 | 0.78 | 60.9 |

| 5 | Aloe vera (L.) Burm. f. JP–385 | Asphodelaceae | Kawar patha | Leaves | Extract, oil | Skin care, pimples, cuts, constipation, bleeding gums, diabetes | 0.055 | 0.64 | 87.5 |

| 6 | Amaranthus viridis Hook JP–371 | Amaranthaceae | Chulai | Whole plant | Extract, powder | Diuretic, laxative, blood purification, epilepsy, Cooking, fodder | 0.057 | 0.53 | 71.7 |

| 7 | Amaranthus spinosus L. JP–378 | Amaranthaceae | Kurand | Whole plant | Extract, paste | Snakebite, laxative, diarrhea, mouth ulcer, vaginal discharge, wound healing, fever, cooking, fodder | 0.088 | 0.51 | 74.5 |

| 8 | Lysimachia arvensis var. caerulea (L.) Turland & Bergmeier JP–443 | Primulaceae | Matri | Whole plant | Extract | Diuretic, laxative, skincare, liver disorders | 0.077 | 0.26 | 61.5 |

| 9 | Avena sativa L. JP–467 | Poaceae | Jaii | Leaves, stem, | Extract, powder, paste | Diabetes, constipation, sexual improvement, brain health, normalize blood pressure, cooking | 0.073 | 0.41 | 62.2 |

| 10 | Azadirachta indica A. Juss. JP–489 | Meliaceae | Nemb | Leaves, bark, roots, oil | Extract, oil, paste, raw | Blood purification, skincare, eczema, hair growth, ulcer, diabetes, fever, gums care, birth control, and abortion, antimicrobial | 0.055 | 0.91 | 93.4 |

| 11 | Brassica campestris L. JP–399 | Brassicaceae | Saag | Whole plant and oil | Extract, paste | Diuretic, milk production in mammals, fodder, cooking | 0.037 | 0.53 | 89.7 |

| 12 | Brassica nigra L. JP–400 | Brassicaceae | Ussu | Whole plant | Extract, paste, decoction | Rheumatism, skin care, snake bite, laxative, cooking | 0.051 | 0.49 | 46.9 |

| 13 | Calotropis procera (Aiti) Aiti. JP–382 | Apocynaceae | Aakda | Leaves, sap milk | Extract, decoction | Sexual disorders, anti-inflammatory, vermifuge, diarrhea, analgesic | 0.051 | 0.49 | 50.0 |

| 14 | Chenopodium album L. JP–405 | Chenopodiaceae | Bathoo | Whole plant | Extract, paste, decoction | Rheumatism, diuretic, laxative, skincare, cooking, fodder | 0.043 | 0.69 | 79.0 |

| 15 | Chenopodium murale L. JP–403 | Chenopodiaceae | Jangli bathoo | Whole plant | Extract, paste, decoction | Piles, asthma, sexual disorder, cough, hair loss, blood purification, cooking, fodder | 0.075 | 0.53 | 67.9 |

| 16 | Citrus limon (L.) Osbeck JP–433 | Rutaceae | Nimbo/Leemo | Fruit, stem bark, oil, | Extract, oil, paste | Scurvy, flu, stomach imbalance, kidney stones, sore throat, malaria, flavor, cooling juice in summer | 0.048 | 0.82 | 74.5 |

| 17 | Convolvulus arvensis L. JP–401 | Convolvulaceae | Bhanweri | Leaves, flowers, roots | Tea, extract, paste | Laxative, mosquito bite, normalized menstruation, wound healing | 0.070 | 0.28 | 47.4 |

| 18 | Conyza canadensis (L.) Cronquist JP–395 | Asteraceae | Bonkhady | Whole plant | Extract, oil | Rheumatism, diarrhea, fodder | 0.58 | 0.26 | 55.8 |

| 19 | Coriandrum sativum L. JP–389 | Apiaceae | Dhanyaa | Whole plant | Extract, oil, raw | Rheumatism, nausea, diarrhea, intestinal gas, toothache, flavor | 0.039 | 0.76 | 34.2 |

| 20 | Cordia dichotoma Forst. f. JP–391 | Boraginaceae | Lasooda/ Nasooda | Leaves, seeds, bark, fruit | Decoction, extract, paste | Fever, anti-inflammatory, diarrhea, headache, Pickle, cooking, fodder | 0.047 | 0.74 | 64.2 |

| 21 | Coronopus didymus (L.)Sm. JP–394 | Brassicaceae | Jungle podia | Whole plant | Extract | Rheumatism, asthma, diarrhea, malaria, cooking, fodder | 0.079 | 0.38 | 38.2 |

| 22 | Cucurbita pepo L. JP–375 | Cucurbitaceae | Loki | Leaves, flowers, fruits, seeds, | Extract, paste, raw | Diuretic, diabetes, ulcer, laxative, constipation, wound healing, vermifuge, cooking | 0.095 | 0.42 | 51.8 |

| 23 | Cuscuta reflexa Roxb. JP–404 | Convolvulaceae | Amar beel | Whole plant/vine | Extract | Rheumatism, diuretic, jaundice, cough, skincare, fever, laxative | 0.58 | 0.06 | 33.3 |

| 24 | Chloris virgata Sw. JP–473 | Poaceae | Leaves | Paste, extraction | Wound healing, Fodder | 0.25 | 0.04 | 25.0 | |

| 25 | Cynodon dactylon (L.) Pers. JP–468 | Poaceae | Ghass | Whole plant | Extract, powder | Skincare, laxative, fodder | 0.068 | 0.22 | 90.9 |

| 26 | Dalbergia sissoo Roxb. ex DC. JP–411 | Fabaceae | Talii | Leaves, wood, bark | Paste, oil | Diuretic, diabetes, vaginal infection, sperm production, piles, nausea | 0.30 | 0.10 | 35.0 |

| 27 | Datura innoxia Mill JP–439 | Solanaceae | Sundu | Fruit, seeds, | Extract, paste | Malaria, ulcer, common cold, asthma, piles, skin problems, hair loss, dandruff, sexual disorders, | 0.35 | 0.13 | 38.5 |

| 28 | Eclipta alba (L.) Hassk. JP–397 | Asteraceae | Gokdi | Whole plant | Decoction | Rheumatism, asthma, diabetes, skincare, laxative, liver disorder, eye drops, hair growth | 0.33 | 0.12 | 45.8 |

| 29 | Eclipta prostrate (L.) L. JP–381 | Asteraceae | Kehraj | Whole plant | Extract, paste | Liver disorders, hair dye, skin care, malaria, anti-inflammatory, diabetes | 0.23 | 0.13 | 38.5 |

| 30 | Eucalyptus globulus Labill. JP–465 | Myrtaceae | Sufaida | Leaves, oil, seed | Extract, oil, paste | Antiseptic, vermifuge, cough, wound healing | 0.15 | 0.13 | 48.1 |

| 31 | Ficus bengalense (Roxb.) Wight & Arn. JP–461 | Moraceae | Bohard | Leaves, hanging roots, fruit, bark | Extract, decoction | Rheumatism, vaginal infection, diabetes, diarrhea, jaundice, anti-inflammatory, ulcer, skincare | 0.045 | 0.89 | 84.3 |

| 32 | Ficus religiosa (L.) Forssk. JP–459 | Moraceae | Peppaal | Leaves, bark, fruit | Extract, decoction, paste | Rheumatism, diabetes, jaundice, ulcer, constipation, cough, fever, wound healing, leucorrhea, skincare, piles | 0.064 | 0.86 | 71.5 |

| 33 | Foeniculum vulgare Mill. JP–369 | Apiaceae | Saunf | Leaves, flowers, fruit | Extract, decoction, tea | Diuretic, laxative, asthma, acne, blood purification | 0.038 | 0.66 | 66.7 |

| 34 | Hordeum vulgare L. JP–466 | Poaceae | Joo | Whole plant | Decoction, paste | Rheumatism, sore throat, cough, vaginal infection, constipation, cooking | 0.048 | 0.63 | 78.6 |

| 35 | Lawsonia Inermis L. JP–419 | Lythraceae | Mehndi | Leaves, flowers, bark | Paste or powder, extract, decoction | Diabetes, skincare, wound healing, ornamentation (hair dye, staining of hair, hands, legs, and nails) | 0.061 | 0.33 | 89.4 |

| 36 | Mangifera indica L. JP–428 | Anacardiaceae | Aamb/Aam | Leaves, flowers, fruits, seed, bark, stem, roots | Powder, extract, raw | skincare, diarrhea, piles, diuretic, diabetes, cardiac disorders, asthma, cough, stomach imbalance, cooking, pickle | 0.064 | 0.85 | 81.3 |

| 37 | Melia azedarach L. JP–451 | Meliaceae | Bkain | Leaves, root, bark, gum | Extract | Asthma, diuretic, diarrhea, laxative, emetic, cooking | 0.040 | 0.74 | 75.8 |

| 38 | Melilotus indicus (L.) All. JP–409 | Fabaceae | Sinji | Whole plant | Extract | Laxative, diabetes, diarrhea, cooking, fodder | 0.14 | 0.16 | 59.4 |

| 39 | Mentha longifolia (L.) Huds. JP–417 | Lamiaceae | Jangli podia | Whole plant | Paste, extract, tea | Asthma, common cold, cough, stomach imbalance, headache, wound healing, laxative | 0.065 | 0.54 | 70.4 |

| 40 | Moringa oleifera Lam. JP–470 | Moringaceae | Sohanjna | Leaves, flowers, seed, and oil | Raw, extract, paste | Diuretic, antimicrobial, asthma, diabetes, birth control, constipation, hair growth, diarrhea, snake bite, ulcer, wound healing, cooking | 0.15 | 0.39 | 65.8 |

| 41 | Morus alba L. JP–457 | Moraceae | Shatoot | Leaves, bark, fruit | Extract, paste, raw | Cough, common cold, eye infection, sore throat, fever, headache | 0.048 | 0.62 | |

| 42 | Nicotiana plumbaginifolia L. JP–434 | Solanaceae | Jangli tambaco | Leaves, stem, fruit | Extract, powder | Rheumatism, snake bite, wound healing, leaches removal, toothache | 0.037 | 0.67 | 85.1 |

| 43 | Ocimum basilicum L. JP–415 | Lamiaceae | Niazbo | Leaves, roots, seeds, | Extract | Headache, menstrual cramps, diuretic, diarrhea, constipation, loss of appetite, flavor | 0.041 | 0.86 | 68.6 |

| 44 | Ocimum sanctum L. JP–413 | Lamiaceae | Tulsi | The whole plant, oil | Extract, powder, oil | Rheumatism, asthma, cough, flu, sore throat, malaria, skincare, diabetes, diarrhea, fever, antiseptic | 0.081 | 0.68 | 61.8 |

| 45 | Oxalis corniculata L. JP–463 | Oxalidaceae | Junlgi booti | Whole plant | Extract, | Rheumatism, diuretic, fever, diarrhea, flu, snake bite, Cooking, flavor | 0.28 | 0.14 | 35.7 |

| 46 | Phragmites karka (Retz.) Trin. Ex steud. JP–436 | Poaceae | Lundda | Stem wood | Extract | Cholera, cardiac disorders, fish poisoning, Cooking, fodder | 0.13 | 0.19 | 34.2 |

| 47 | Ricinus communis L. JP–402 | Euphorbiaceae | Arand | Leaves, roots, seeds, oil | Extract, paste | Rheumatism, laxative, liver disorders, castor oil for eye care, birth control, skincare | 0.059 | 0.51 | 80.4 |

| 48 | Salvodora oleoides Decne JP–430 | Salvadoraceae | Jaal | Leaves, bark, roots, seed, and oil | Raw, paste, extract | Rheumatism, diuretic, stomach imbalance, cough, fever, kidney stones, toothache, mosquito repellent, cooking | 0.069 | 0.65 | 57.7 |

| 49 | Sisymbrium irio L. JP–393 | Brassicaceae | Farmi saag | Leaves, seeds, flowers | Extract, powder, paste | Rheumatism, cough, wound healing, sore throat | 0.091 | 0.22 | 40.9 |

| 50 | Solanum nigrum L. JP–453 | Solanaceae | Bambool | Leaves, stem | Extract, raw | Skin problems, loss of appetite, asthma, ulcer, laxative, cough, fever, cooking | 0.069 | 0.58 | 75.9 |

| 51 | Solanum surattense L. JP–445 | Solanaceae | Rubdi | Whole plant | Decoction, paste | Rheumatism, sore throat, cough, vaginal infection, constipation | 0.12 | 0.21 | 76.2 |

| 52 | Sonchus arvensis L. JP–380 | Asteraceae | Maii bodi | Leaves, roots, flowers | Extract | Asthma, cough, chest pain, caked breast treatment | 0.10 | 0.19 | 41.0 |

| 53 | Syzygium cumini L. JP–462 | Myrtaceae | Jaman | Leaves, flowers, wood | Extract, raw | Rheumatism, sore throat, asthma, blood purification, ulcer | 0.05 | 0.50 | 72.0 |

| 54 | Terminalia arjuna L. JP–408 | Combretaceae | Arjun | Leaves, bark, fruit, flower | Extract, paste, powder | Diabetes, cardiac disorders, cough, sore throat, diarrhea, constipation, sore eyes | 0.076 | 0.46 | 71.7 |

| 55 | Triticum aestivum L. JP–476 | Poaceae | Daany/Gandam | Whole plant | Extract, paste | Diuretic, laxative, kidney problems, sexual strength in both sexes, sore throat, constipation, cooking | 0.037 | 0.95 | 88.9 |

| 56 | Withania somnifera (L.) Dunal JP–441 | Solanaceae | Aak-Singh | Leaves, flowers, fruits | Extract | Rheumatism, improvement of sexual strength in male | 0.032 | 0.31 | 67.7 |

| 57 | Xanthium strumarium L. JP–432 | Asteraceae | Muhabat booti | Leaves, roots, fruit | Decoction | Diuretic, laxative, improve appetite, sedative, malaria, fever | 0.37 | 0.08 | 37.5 |

| 58 | Ziziphus mauritiana Lam. JP–440 | Rhamnaceae | Berry | Roots, leaves, fruits, | Extract, paste, oil, raw | Diuretic, diabetes, fever, cough, constipation, sleeplessness, liver disorders, ulcer, wound healing, skincare | 0.082 | 0.55 | 68.2 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Usman, M.; Ditta, A.; Ibrahim, F.H.; Murtaza, G.; Rajpar, M.N.; Mehmood, S.; Saleh, M.N.B.; Imtiaz, M.; Akram, S.; Khan, W.R. Quantitative Ethnobotanical Analysis of Medicinal Plants of High-Temperature Areas of Southern Punjab, Pakistan. Plants 2021, 10, 1974. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants10101974

Usman M, Ditta A, Ibrahim FH, Murtaza G, Rajpar MN, Mehmood S, Saleh MNB, Imtiaz M, Akram S, Khan WR. Quantitative Ethnobotanical Analysis of Medicinal Plants of High-Temperature Areas of Southern Punjab, Pakistan. Plants. 2021; 10(10):1974. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants10101974

Chicago/Turabian StyleUsman, Muhammad, Allah Ditta, Faridah Hanum Ibrahim, Ghulam Murtaza, Muhammad Nawaz Rajpar, Sajid Mehmood, Mohd Nazre Bin Saleh, Muhammad Imtiaz, Seemab Akram, and Waseem Razzaq Khan. 2021. "Quantitative Ethnobotanical Analysis of Medicinal Plants of High-Temperature Areas of Southern Punjab, Pakistan" Plants 10, no. 10: 1974. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants10101974