Abstract

This work is part of a semio-constructivist conception of learning sport and physical education that emphasizes the primary role of language action in the co-construction of knowledge in/through action. The aim is to study the decision-making methods of three groups of students in a verbal football cycle. A total of 48 pupils participates voluntarily in our study, in mixed teams, with/without a teacher (Time = 2 × 4 mn) before/after small sided games (2 × 10 mn). The language activity of students is dependent on the development of cognitive structures identified from the classes to which they belong.

1. Introduction

Bringing pleasure to a student’s learning can only be achieved through his involvement in the construction of knowledge. This involvement will make sense if he fully understands the goals he has to achieve and how to reach them to acquire knowledge. In this context, Jean Lave (1988) [1] postulated that “knowledge is formed in activities with a social purpose. They make sense in terms of the purpose of the actions and not in relation to scientific concepts or in relation to conceptual organizations external to the subject, elaborated by communities of experts who discuss and develop an epistemology about them”. Similarly, Wright and Forrest (2007) [2] state that it is not enough to teach for students to learn, what the author points out here is the possibility of understanding something other than what the teacher wanted to convey. Knowledge is often acquired in exchanges in reference to particular contexts; speech is an action situated constantly towards adapting to the context [3]. As part of the teaching of physical activities, Delignières (1991) [4] noted a massive use of the explicit actions and verbalization of procedures: “It is striking how much students currently are supposed to think and verbalize in EPS class”.

Similarly, Darnis–Paraboschi, Lafont, and Menaut (2007) [5] have emphasized the interest of language interactions in dyads [6]. They attach particular interest in co-operation to build new knowledge in learning situations and in particular their beneficial effects in the acquisition of new skills in collective sports games. Cooperative Learning Moments by Grangeat (2013, 2016) [7,8] allow students to engage in a process of co-building knowledge in/through action.

Much research in different disciplines has contributed to making verbalization an important step in teaching practices [9,10,11]. In the experimental sciences, a mode of teaching was developed called “scientific debate in the classroom” [12]. However, for this method of teaching based on student verbalization to be beneficial for acquiring new skills, there must be a real scientific debate where it is possible to ask good questions and solve problems [13]. A class discussion is a scientific discussion around a specific problem involving students with different points of view, reflections and experiences on a problem proposed by the teacher.

In physical education and sports, Gréhaigne and Godbout (1998) [14] prefer to talk about “debates of ideas” because according to them, it is not possible to have a strictly scientific debate at a gymnasium or the stadium, because of the difficulty identifying the concepts, knowledge, and skills at work because they come from a wide variety of fields.

Debates between pupils or between them and their teacher imply a shared verbalization. In this perspective, Caverni (1997) [15] pointed out that verbalization can be a source of information and influence on cognitive processes. Considering the timing of the debate regarding the execution of the tasks, he distinguished three types of verbalization: verbalization before (considering what will be or should be done), simultaneous verbalization (considering what is done) and subsequent verbalization (given what has been done) [15].

The debate of ideas as a teaching technique is an innovative concept in the teaching-learning process at school [16]. This method insists that knowledge is developed with the help of peers and teachers and co-constructed during exchanges [17]. The debate of ideas appears first of all as a situation of verbalization about the action intended to make one aware of the task to be carried out and the instructions which characterize it. Then this notion of debate is supplemented by notions of observation and evaluation with a retreat from the action [18].

In physical education, the debate of ideas consists of proposing verbalization sequences between students to produce cognitive effects that put them in a situation that aims to co-construct knowledge. Consequently, in this didactic context, learners are not limited to a passive role in the hands of a master or a coach who holds knowledge, but instead participate in the construction of knowledge [19,20]. This teaching situation allows students to discuss and have verbal exchanges about the action, which reflects a reflexive approach [21,22] that consists of a distanced posture of reasoning about what needs to be done to change a situation [23]. In fact, the debate of ideas and situations can have different objectives, having certain similarity with situations proposed by Brousseau in his theory of the didactic situation [24].

Our work is part of a socio-semio-constructivist teaching approach that emphasizes the importance of language activity in the process of co-construction of knowledge in/through action [23,25]. Teaching team sports, especially football, is not just about providing students with instructions to apply or orders to follow to complete an action project. It is also about implementing reflective practices in and through action among students who are called to understand to play and play to understand [26,27,28]. It is through discursive interlocutions between students that students can develop instructions in the form of effective rules of action [29]. Our hypothesis is that the conditions for success in football games are closely related to the development of students’ cognitive structures [30]. A teaching approach with a debate of ideas could change the traditional roles of teachers and students [30]. We are no longer talking about a vertical relationship between someone who knows and someone who does not know, we are talking more about a co-constructed learning [31,32,33].

2. Method

2.1. Participants

Our study involved 3 homogeneous groups of 16 students and each group was composed of 8 boys and 8 girls.

- Group 1 (G1) (16 students in grade 5, 8 girls and 8 boys aged 10 ± 0.3 years) consisted of four equivalent teams. Each team was made up of 4 players (2 boys and 2 girls) that are registered in the 5th year of primary school.

- Group 2 (G2) (grade 9) experienced the same training but included students aged 14 ± 0.4 years that are enrolled in the 9th year.

- Group 3 (G3) (grade 11) experienced the same training but included students aged 16 ± 0.4 years that were registered in the 2nd year of secondary school.

The research was conducted in accordance with the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki. The participants and their parents were informed about the study details. Then the parents signed an informed consent form because the students were under 18. The research project was approved by the Scientific and Ethics Committee of High Institute of Sports and Physical Education of Kef (Tunisia).

An introductory lesson was organized for team selection. As a method of team selection suggested by Farias, Valério and Mesquita [34] and recently used by Wissam et al. [17], four students in each class were elected to form a selection committee that co-operated with the teacher to compose six heterogeneous but balanced teams. Each team included the same number of girls and boys and different skill levels (from less to more qualified).

2.2. Procedure

Each team had 12 learning sessions with verbalization under the control of the teacher (T = VV ‘total effective time’). Each team played for a preliminary time of 12 min and then verbalized for 4 min in the presence of the teacher. This one asked open question of the type: “What did you notice? What made you notice that? What are your plans for response to this situation?”. Then each team went back into play to validate/invalidate the decisions already made during the debate of ideas sequence. The aim was to enable students to co-construct shared knowledge [35,36].

All game situations were filmed using digital video. All verbalization sequences and “interlocutions” were recorded using a camcorder to identify interlocutors and were subsequently transcribed in writing for speech analysis. Teams rotated through a (a) warm up, (b) play, (c) observe cycle throughout this game play lesson segment.

To analyze student verbalization, we opted for the model of Kerbrat–Orecchioni (1998) [37], which distinguishes between six types of answers: “no answer, off-topic, a beginning of decision, a decision with justification, at least one alternative with justification and reproach”. This typology has the advantage of emphasizing the communication contract that binds trading partners both structurally and dynamically.

The definition of the terms is therefore as follows:

- “No answer”: the student does not answer.

- “Off topic”: the student answers, but his answer remains inadequate to the question asked.

- “Beginning of decision”: the student answers, but without providing an explanation.

- “A decision with justification”: while proposing a simple justification.

- “At least one alternative with justification”: the student provides several solutions in the form of options, often with complex reasons.

- “Reproach”: it is the inadequacy between the grammatical form of the utterance and its aim.

2.3. Data Analysis

The 12-learning sessions were divided into three phases (phase 1 going from session 1 to 4; phase 2 of session 5 to 8 and phase 3 of session 9 to 12) to perform statistical analysis. Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS version 24 for Windows (SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL, USA). The normality of the datasets was verified using the Smirnov test. One-way Anova tests were used to compare the variables (no answer, off topic, a beginning of decision, decision with justification, at least one alternative with justification and reproach) between sessions and between groups. They were a priori alpha set at 0.05 (Table 1).

Table 1.

Comparison of response categories between the three groups during the 12 sessions.

We used two-way repeated measures Anova to examine the session effect, the group effect, and the interaction effect (group × session) on the different variables. Effect sizes (ES) were considered trivial, small, medium and large for values 0 to 0.20, 0.20 to 0.50, 0.50 to 0.80 and >0.80, respectively [38] (Table 2).

Table 2.

Results of the ANOVA with 3 × 3 repeated measures [groups (level of education × sessions (S1–S4, S5–S8 and S9–S12)].

3. Results

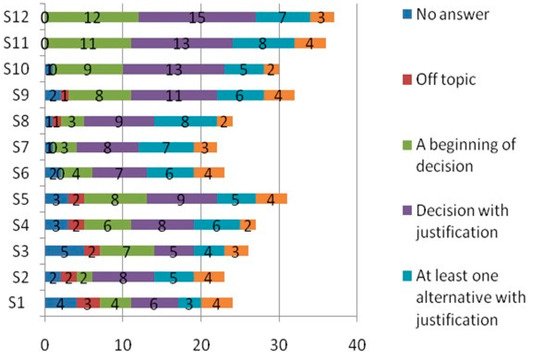

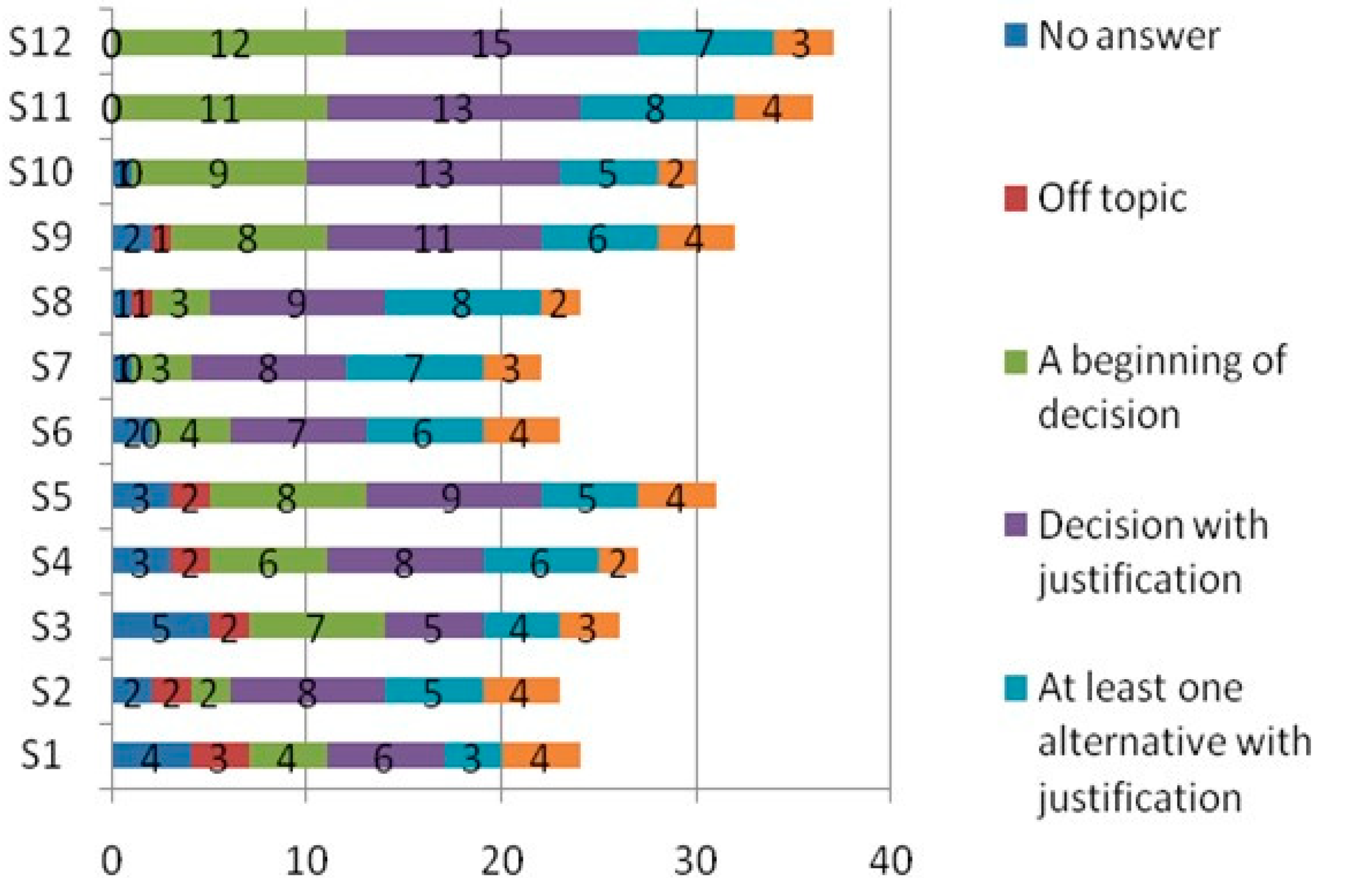

The “no response” category decreases as the sessions progress and measure, but the differences are significant between sessions S1–S4 and S9–S12 and between the different sessions for only group 2 and for group 3 between the first session (S1–S4) and the other two sessions (S5–S8 and S9–S12). Comparison between three groups showed that there were only significant differences between group 1 and group 2 for category “no answer” at the level of the first four sessions (S1–S4) and the last four sessions (S9–S12).

The “off topic” category was larger in session S1–S4 than the other two sessions for all three groups. The differences were only statistically significant between sessions (S1–S4) and (S9–S12) for groups 2 and 3 (Table 1).

The number of students who started to make or decide with justification and or at least alternate with justification increased with the sessions and the differences were significant in favor of the S9–S12 session in the three groups (Table 1).

The response patterns in the three groups were remarkable in session S9–S12 because of the same reasons as the other two sessions, except that the differences were not significant for group 3 (Table 1).

The main effects of sessions and groups has significant impacts on the variables no response, off topic, a beginning of decision, decision with justification and at least one alternative with justification, except that there was no significant group effect on the off-topic variable. On the other hand, there was a significant interaction effect on this variable (Table 2).

3.1. Category “No Answer”

This is the situation in which the student does not respond. In this category, the frequency of non-response declined significantly throughout the learning cycle. It decreased to 0 during the last two sessions for all three studied scholar levels (see Appendix).

The gradual decline of the "no answer" category throughout the cycle can be credited to the verbalization and initiative taken by students in speaking tours. The initially reluctant attitude shown by their abstention began to decline throughout the cycle. Thus, students have given more free rein to their interlocutory activities, probably because the gradual change in their posture leads them to ask words about what they have done or intend to do. However, we note that the age variable acts strongly on this “no answer” category. Students enrolled in primary school are more likely to use this “no answer” mode. Indeed, discussion at this age provokes a hesitant attitude among students. On the other hand, students enrolled in high school and high school give free rein to their expression and take the initiative to speak more often, while the other two classes find it less difficult to answer.

This skill does not appear immediately and presupposes a time of adjustment and emergence. However, it should be noted that an adaptation and a context favorable to exchanges are conditions to establish a “space of connivance” between students. Moreover, when verbalizing, it is necessary to pay attention to the primordial role of the speech of all, that is to say the time of speech shared if possible, between peers throughout the cycle as well. This fact is attested to by the number of "non-responses" that were still observed during the eighth session, marking the difficulty of explaining collective thinking.

3.2. Category “Off Topic”

In this response mode, the student provides answers, but these answers are inadequate for the question asked. Reading the graph clearly shows that the number of responses belonging to the category “off topic” decreased from the fifth session (see Appendix). This regression was especially remarkable for groups 2 and 3.

This decrease was the result of a consciousness experienced by the three groups of students of interest in the debate for the game and interest in sharing points of view in close relationship with the problems encountered during the game.

The small number for the “off topic” category is interesting because it shows the relevant involvement of a number of students in the discussion. Each student asks for his contribution in the exchange while touching the heart of the subject. It should be noted that the number of responses belonging to this category apparently decreases as one moves forward in the cycle. This may be due to the fact that students have become able to master the subject and act accordingly while striving to give answers that are directly related to the topic of the exchanges. A priori, it appears that the factor “time” acts considerably on the acquisition of these language skills of entering into the relevance of exchanges. Students need a number of sessions to focus their attention on the subject in question. As a result, their answers will get as close to the subject as possible, and a mutual self-adjustment, sometimes sharp or even scathing, makes it possible to avoid irrelevant remarks.

3.3. Category “a Beginning of Decision”

This is a response category where the student responds, but without providing an explanation.

Students in the first group use this category of answers much more than others (see the Appendix). They have a tendency to answer in a simple and concise way. During the first six sessions, the “decision-making” response model kept its high rate and reached its peak from the ninth session, where some 40 responses were recorded. Sometimes, there is a significant drop in this category. This drop suggests that verbalization activity is declining. In fact, the decrease in the number of “beginning of decision” events occurred simultaneously with the increase of more complex response categories that refer to an advanced stage of verbalization.

Therefore, the major concern of students is not only to answer and make proposals, but to support the answers with justifications, to argue to convince others. This is not a simple language production, but rather an attempt to argue that the students want to go through with their proposals and try to act on the interlocutor by bringing him to agree with the proposed opinion, that is to say to accept to be persuaded.

3.4. Category “Decision with Justification”

In this category, the student responds while proposing a simple justification. Statistical processing showed a progression of frequencies relative to this category. This progression is not produced in the same way for the three groups of students. This evolution is remarkable for groups 2 and 3.

Although there was a statistically significant increase, the evolution of the category “decision with justification” was not permanent. Its slight progress paved the way for more complex response modalities, giving rise to a more effective and deployed verbalization. This category of answer is more used especially by group 2. This allows us to say that players of this age prefer to give simple answers with a single justification to avoid engaging in an explanation to several arguments that may attract criticism from his peers.

3.5. Category “At Least One Alternative with Justification”

In this response category, the student provides several solutions in the form of options, often with complex reasons.

The statistical analysis reveals a significant difference between the three groups. The progression of this category follows an ascending curve. Thus, there was a noticeable increase from the third session, culminating in the 11th and 12th sessions. However, the variation in evolution in this category went from one level of student to another. This evolution was remarkable, especially for group 2.

It is in this category of responses that the approach focused on language productions had the most effect by soliciting the ability to make complex decisions: verbalization sequences enabled students to acquire the tools they need to make decisions in an evolving and dynamic context. This proves that they began to better interpret the game in order to solve the problems encountered in the game. Thus, the students were fully anchored in the process of verbalization and argumentation.

Students in group 3 are sufficiently equipped with communicative techniques and freedom of expression and no longer hesitate to be carried away by detailed explanations, which reflects a kind of linguistic and social maturation.

3.6. Category “Reproach”

This category is synonymous with the inadequacy between the grammatical form of the utterance and its purpose. The appearance of the “reproach” response category was a minority occurrence for the three experimental groups. This observation, however, corresponds to an emotional state that shows as being out of control and can sometimes be close to verbal aggression. These reproaches can result from a mismatch between the points of view, going as far as calling into question a point of view of a teammate. However, the statistical analyses show a difference between the three groups of students. The evolution of the answers is remarkable, especially for group 2. This evolution starts from the eighth session until the last session.

Indeed, the evolution of responses in the form of reproaches throughout the cycle marks an evolution of a new decision-making parameter. Students, by questioning what their peers have just verbalized, actually began to make more complex decisions that disprove those already taken or attitudes initially accepted. The multiplicity of possible interpretations about the game was thus operationalized in the contradictory debates and the discussion of points of view.

4. Discussion

Even if it was the same situation of reference (4 Vs 4) throughout the cycle, the difficulties encountered by the players are no longer the same; they differ from one configuration of the game to another and from one match to another. Therefore, decision-making is dependent on the situation in which students find themselves: “Knowing is first of all being able to use what one has learned, to mobilize to solve a problem or to clarify a situation [39].”

Verbal interaction is a testament to students’ awareness of the fact that there are various and even contradictory points of view about the game. This interpretation often depends on a direct reading of the game according to the project of collective action. Nevertheless, as Wallian explains, this reading is not enough for the sense of action to be exhausted, since it is not directly established behind the gestures-signs responsible for carrying those actions out [27]. Learning is the result of a permanent interaction between personal knowledge and students’ collective knowledge. The confrontation of the inter-student points of view allows the co-construction of the effective rules of action conducive to the improvement of the tactics of play. This improvement can be translated by the way in which the pupils collectively built the decisions to take to go beyond the problems encountered.

In this semio-constructivist approach, the issue concerns the question of co-construction with peers, a signifying activity in a didactic situation to be modified by the sharing of experiential knowledge [26]. In this postulate, we reached to Austin (1965) [40], who supports the idea that all exchange requires a posture of otherness because it is a question of welcoming the novelty and the point of view of others by accepting to find transformations. The intersection of peer points of view on a common project becomes a major interest for all peers. This crossover creates, during the debate, a conflict of interpretations that is co-constructed in the argumentative interaction and/or in the negotiation of the relations of places [41]. This learning strategy allows the emergence of action knowledge to be shared within a community of practices currently being developed [35,36].

The complexity of the verbalization goes hand in hand with the emotional side of the students. Decision-making, especially for those with “at least one alternative with justification”, has dramatic repercussions on the functioning of some students. The conflicting aspect of the discussion was reflected in the responses in the form of “reproach”: it nourishes inter-student exchanges and opens other perspectives for discussion. In this regard, it should be noted that “reproaches” are not necessarily conceived as direct accusations that could cut short the discussion envying a balance of power, but rather as catalysts for reviving other topics and giving other dimensions to verbalization. These reproaches sometimes come in the form of direct speech acts and sometimes in the form of indirect speech acts “elliptical expression for” acts of language formulated indirectly, under the guise of another act of speech [42].

This study used open questioning in a football game. We were particularly concerned towards the situational conditions in which the questioning of teachers takes place and in the nature of the students’ responses in relation to the cognitive structures and the use of language.

Teachers asked open questions during game football experiments, which typically happened in a small group setting. In these experiments, teachers appeared to use open questions in order to encourage students to predict, reason and to promote recognition and recall of particular information. The results of our study showed that during the learning sessions, open-ended questions aimed at prediction and reasoning were able to elicit responses from students demonstrating a higher level of cognition, targeting recognition and recall of facts. This finding is consistent with previous research showing that “abstract language input”, like open-ended questions, extends concrete knowledge to a higher level of cognitive processing [43,44]. Regarding the use of language in student responses, we found that questions were more likely to elicit responses using more varied vocabulary and more complex sentence structures. Open questions used by teachers tend to have many varied answers, they allow many students to participate and answer the same question, regardless of the answer of the first responder. In this way, these questions encourage the sharing of different thoughts in a debate of ideas.

The students’ responses reflect their need to communicate their thoughts on a situation experienced during the game. During the exchanges or responses, a reflective distance was established between the student and his past actions, giving a description and perceptions of the game [30]. By contributing to the reflection on past action, language becomes a privileged tool for highlighting concepts related to game play. The participants’ responses not only promote the acquisition of a common game language, but also an evolution of the design of the game, its components, its rules and its tactical aspects [45]. This evolutionary process sets up a progressive understanding of the game [32] by going from a convergent reflection (where the participants analyze, categorize, explain, compare, etc.) to a construction process where a divergent reflection takes place to create, invent and imagine solutions for.

5. Limitations

This study is notable in that it was the first to study the modalities of student responses in a football game according to players’ cognitive structures. There are, however, some limitations, the first of which was that we did not take into consideration the speech of the students while they play; in fact, the players verbalize and propose instructions and effective action rules throughout a game. These self-instructions can influence the decisions taken by the students as they discuss. Another limiting aspect of this study is that some responses remain unclassifiable depending on the analysis model used and it did not verify the implementation of decisions made by players.

6. Conclusions

As part of a new teaching/learning strategy, planning and managing a debate of ideas in physical education involves organizing a class activity that is not just about declarative knowledge, but rather is a tool to analyze practice and not as a challenge of knowledge. With this collaborative form, the identification of problems, the choice of adequate solutions on the one hand and the distribution of tasks between members of the same team are two key points of the collective activity. This distribution of tasks and roles of each should be part of a temporality for their execution.

The interactive dynamic highlights the importance of such cooperative forms of learning. It is a process that results in the mobilization of the cognitive activities of the interlocutors in order to elaborate a project of collective action. The emergence of new knowledge is the result of a permanent interaction between what is the prerequisite and what is envisaged during verbalization. This consists of a process of modifying individual representations within the group, where the interest of verbal interactions in decision making for the development of tactical skills.

The inter-student debate of ideas changes content and nature according to the teaching period. The results found are congruent with Gréhaigne and Godbout (2014)’s [46] work, which classifies students’ cognitive state into four major periods. Students enrolled in middle and high school are able to explain the factors of success and the causes of failure. Through the questioning of the teacher, the player can dig into his knowledge to give answers. In this context, student can develop projects and strategies for the success of the action (reflection on the action). This is the stage of success and understanding with a beginning of generalization.

Author Contributions

Four authors contributed to this research: M.Z. acted as the first author throughout the data analysis and manuscript drafting; H.S. contributed to data collection, development, reviewing and revising; W.B.K. contributed to manuscript drafting, reviewing and revising; H.G. contributed to data analysis and manuscript completion; M.G. contributed to reviewing and revising and M.H. contributed to supervision, reviewing and revising. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The research was conducted in accordance with the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Scientific and Ethics Committee of the High Institute of Sports and Physical Education of Kef as such the approval was waived for minimal risk study with no significant human subject experiments.

Informed Consent Statement

The parents signed an informed consent form as the studied students were under 18.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from JS.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the Regional Board of Education for making it possible to collect data in schools.

Conflicts of Interest

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Appendix

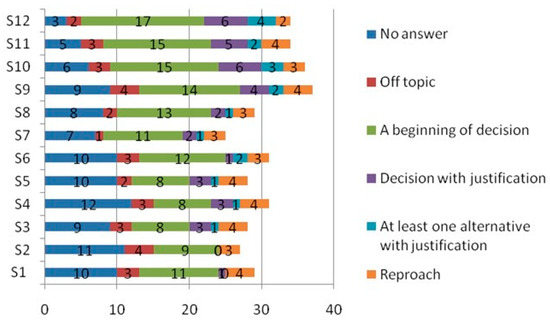

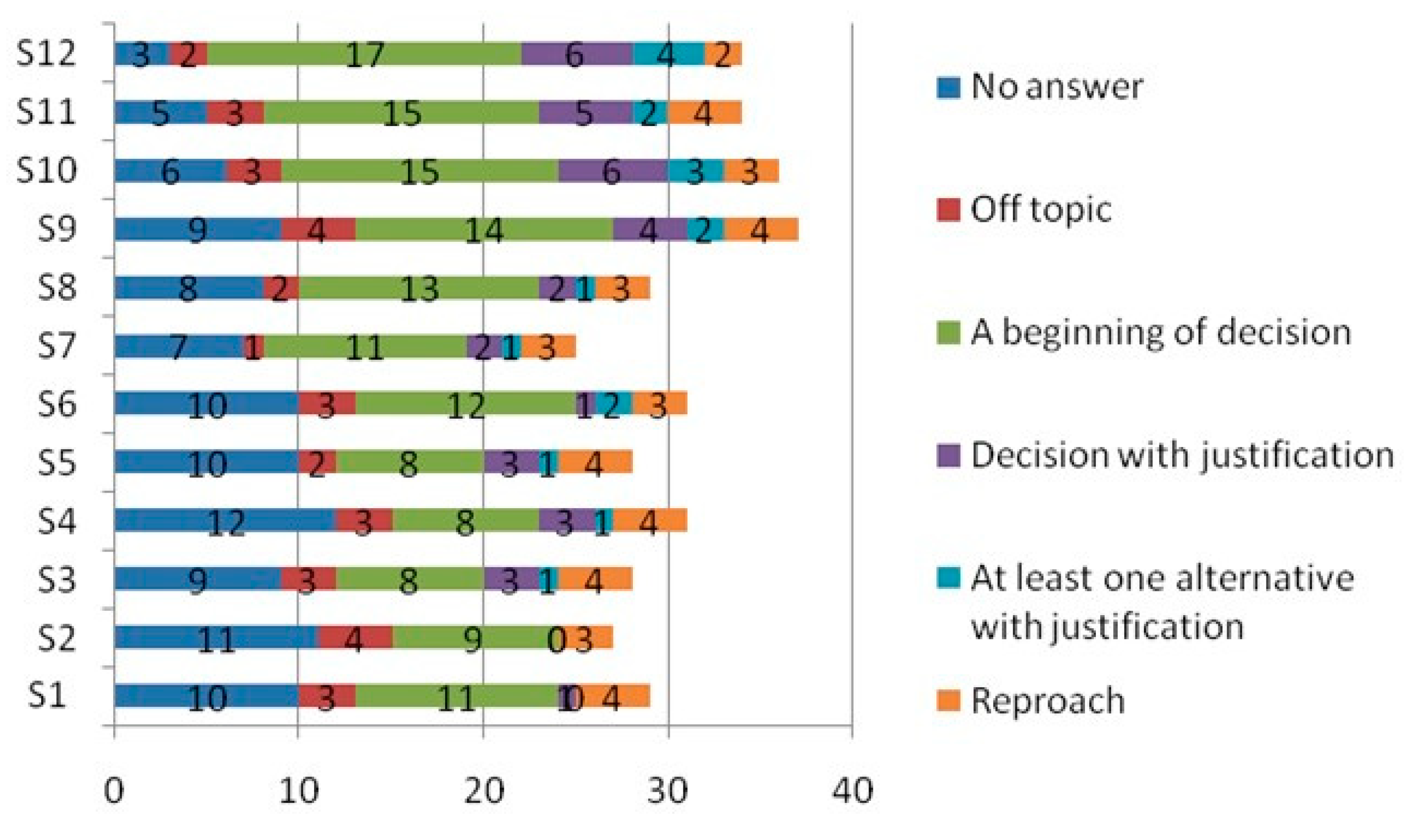

Figure A1.

Categories of responses during the twelve sessions for group 1.

Figure A1.

Categories of responses during the twelve sessions for group 1.

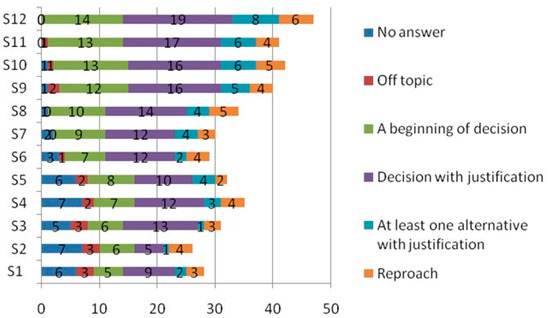

Figure A2.

Categories of responses during the twelve sessions for group 2.

Figure A2.

Categories of responses during the twelve sessions for group 2.

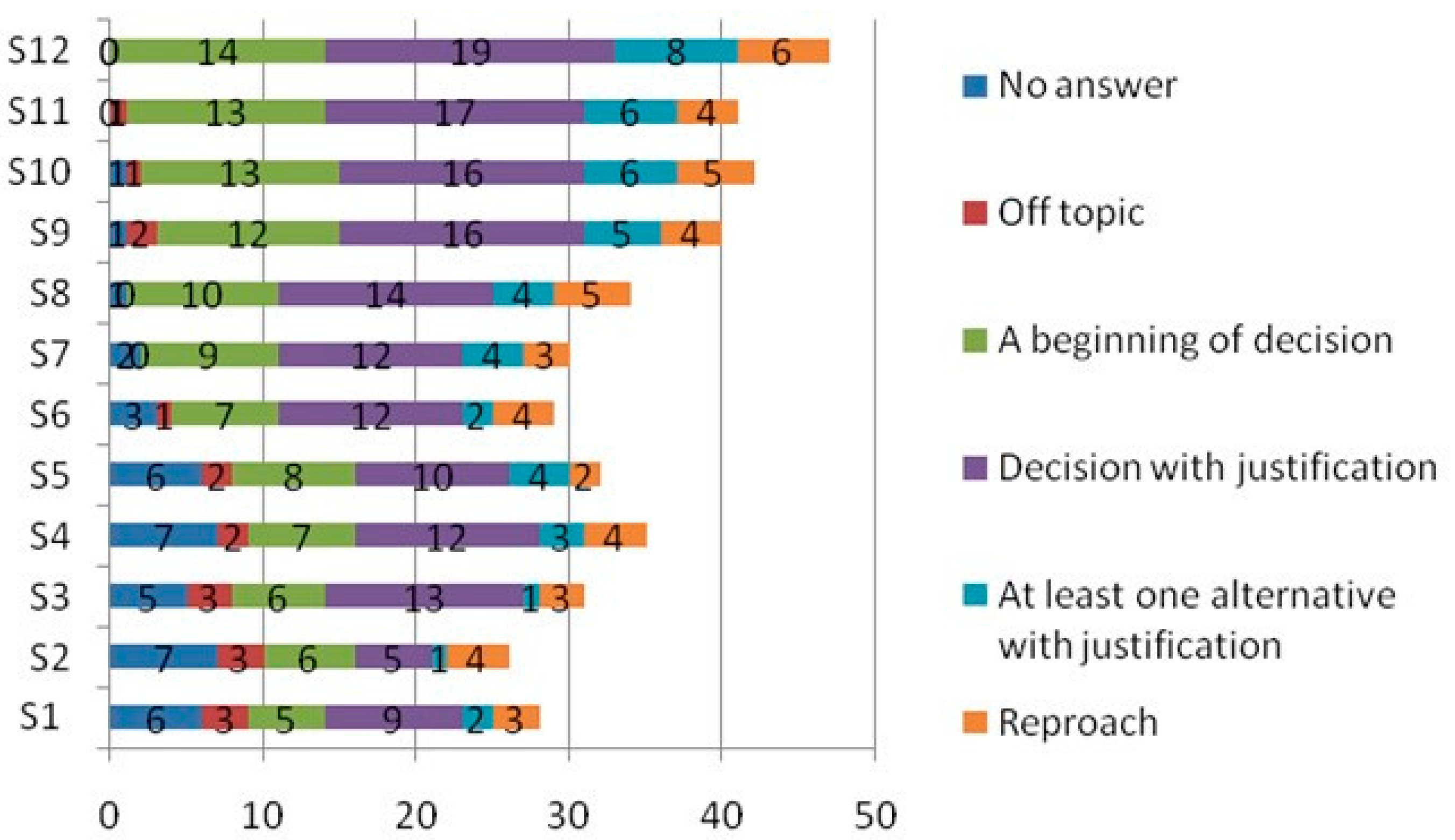

Figure A3.

Categories of responses during the twelve sessions for group 3.

Figure A3.

Categories of responses during the twelve sessions for group 3.

References

- Lave, J. Cognition in Practice: Mind, Mathematics and Culture in Everyday Life; Cambridge University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Wright, J.; Forrest, G. A Social Semiotic Analysis of Knowledge Construction and Games Centred Approaches to Teaching. Phys. Educ. Sport Pedagog. 2007, 12, 273–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roth, W.-M. Learning Process Studies: Examples from Physics. Int. J. Sci. Educ. 1998, 20, 1019–1024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delignières, D. Risque Perçu et Apprentissage Moteur. In Apprentissage Moteur: Rôle des Représentations; EPS: Paris, France, 1991; pp. 157–171. [Google Scholar]

- Darnis, F.; Lafont, L.; Menaut, A. Interactions Verbales En Situation de Co-Construction de Règles d’action Au Hand-Ball: L’exemple de Deux Dyades à Fonctionnement Contrasté. E J. Rech. Sur L’Intervention En Educ. Phys. Sport. 2007, 11, 56-17. [Google Scholar]

- Loewen, S.; Sato, M. Interaction and Instructed Second Language Acquisition. Lang. Teach. 2018, 51, 285–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grangeat, M. Dimensions and Modalities of Inquiry-Based Teaching: Understanding the Variety of Practices. Educ. Inq. 2016, 7, 29863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grangeat, M. Modéliser les Enseignements Scientifiques Fondés Sur Les Démarches D’investigation: Développement des Compétences Professionnelles, Apport du Travail Collectif; Presses universitaires de Grenoble: Grenoble, France, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Perret-Clermont, A.-N. La Construction de l’intelligence Dans l’interaction Sociale; Peter Lang AG: Bern, Germany, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Brousseau, G.; Balacheff, N. Théorie Des Situations Didactiques: Didactique Des Mathématiques 1970–1990; La pensée sauvage Grenoble: Grenoble, France, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Schubauer-Leoni, M.-L. Interactions Didactiques et Interactions Sociales: Quels Phénomènes et Quelles Constructions Conceptuelles. Skholê Cah. Rech. Dév. 1997, 7, 102–134. [Google Scholar]

- Johsua, S.; Dupin, J.-J. Introduction à La Didactique Des Sciences et Des Mathématiques; Presses universitaires de France Paris: Paris, France, 1993; Volume 327. [Google Scholar]

- Brousseau, G. Fondements et Méthodes de La Didactique Des Mathématiques. Fond. Méthodes Didact. Mathématiques 1986, 7, 33–115. [Google Scholar]

- Gréhaigne, J.F.; Godbout, P. Observation, Critical Thinking and Transformation: Three Key Elements for a Constructivist Perspective of the Learning Process in Team Sports. Educ. Life 1998, 109–118. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/332605897_Observation_critical_thinking_and_transformation_three_key_elements_for_a_constructivist_perspective_of_the_learning_process_in_team_sports (accessed on 20 April 2021).

- Caverni, J.-P. L’éthique Dans Les Sciences Du Comportement; FeniXX: Paris, France, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Sahli, H.; Selmi, O.; Zghibi, M.; Hill, L.; Rosemann, T.; Knechtle, B.; Clemente, F.M. Effect of the Verbal Encouragement on Psychophysiological and Affective Responses during Small-Sided Games. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 8884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben Khalifa, W.; Zouaoui, M.; Zghibi, M.; Azaiez, F. Effects of Verbal Interactions between Students on Skill Development, Game Performance and Game Involvement in Soccer Learning. Sustainability 2021, 13, 160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gréhaigne, J.-F.; Billard, M.; Laroche, J.-Y. L’enseignement Des Sports Collectifs à l’école: Conception, Construction et Évaluation; De Boeck Supérieur: Brussels, Belgium, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Rabatel, A. Interactions Orales En Contexte Didactique: Mieux (Se) Comprendre Pour Mieux (Se) Parler et Pour Mieux (s’) Apprendre; Presses Universitaires Lyon: Lyon, France, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- van Aalst, J. Distinguishing Knowledge-Sharing, Knowledge-Construction, and Knowledge-Creation Discourses. Int. J. Comput. Support. Collab. Learn. 2009, 4, 259–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vermersch, P. Du Faire Au Dire (l’entretien d’explicitation). Cah. Pédagogiques 1995, 336, 27–32. [Google Scholar]

- Binder, P.-E.; Holgersen, H.; Moltu, C. Staying Close and Reflexive: An Explorative and Reflexive Approach to Qualitative Research on Psychotherapy. Nord. Psychol. 2012, 64, 103–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zghibi, M.; Sahli, H.; Bennour, N.; Guinoubi, C.; Guerchi, M.; Hamdi, M. The Pupil’s Discourse and Action Projects: The Case of Third Year High School Pupils in Tunisia. Creat. Educ. 2013, 4, 165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Brousseau, G.; Warfield, V. Didactic Situations in Mathematics Education. In Encyclopedia of Mathematics Education; Lerman, S., Ed.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, The Netherlands, 2020; pp. 206–213. ISBN 978-3-030-15789-0. [Google Scholar]

- Lehmans, A.; Cordier, A. Transliteracy and Knowledge Formats. In European Conference on Information Literacy; Springer: Heidelberg, Germany, 2014; pp. 118–127. [Google Scholar]

- Wallian, N.; Chang, C.W. Sémiotique de l’action Motrice et Des Activités Langagières: Vers Une Épistémologie Des Savoirs Co-Construits En Sports Collectifs. In Configurations du Jeu: Débat D’idées & Apprentissage du Football et des Sports Collectifs; Presses universitaires de Franche-Comté: Besançon, France, 2007; pp. 146–164. [Google Scholar]

- Wallian, N. Sémiotique de l’agir enseignant en EPS : Figures d’action et registres interprétatifs en milieu difficile. Carrefours Educ. 2015, 40, 67–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cushion, C.J. Reflection and Reflective Practice Discourses in Coaching: A Critical Analysis. Sport Educ. Soc. 2018, 23, 82–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stecanela, N.; Zen, A.C.; Pauletti, F.B. Action Research and Teacher Education: The Use of Research in a Classroom for the Transformation of Reality. IJAR Int. J. Action Res. 2019, 15, 9–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gréhaigne, J.-F.; Godbout, P. Debate of Ideas and Understanding with Regard to Tactical Learning in Team Sports. J. Teach. Phys. Educ. 2020, 1, 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Godbout, P.; Gréhaigne, J.-F. Regulation of Tactical Learning in Team Sports–The Case of the Tactical-Decision Learning Model. Phys. Educ. Sport Pedagog. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godbout, P.; Gréhaigne, J.-F. Revisiting the Tactical-Decision Learning Model. Quest 2020, 72, 430–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Light, R.L.; Clarke, J. Understanding the Complexity of Learning through Movement. Phys. Educ. Sport Pedagog. 2021, 26, 268–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farias, C.; Valério, C.; Mesquita, I. Sport Education as a Curriculum Approach to Student Learning of Invasion Games: Effects on Game Performance and Game Involvement. J. Sports Sci. Med. 2018, 17, 56–65. [Google Scholar]

- Lave, J.; Wenger, E. Situated Learning: Legitimate Peripheral Participation; Cambridge University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Sensevy, G.; Mercier, A. Agir Ensemble. In L’action Conjointe Du Professeur et Des Élèves Dans Le Système Didactique; Presses Universitaires de Rennes: Rennes, France, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Kerbrat-Orecchioni, C. La Notion d’interaction En Linguistique: Origines, Apports, Bilan. Lang. Fr. 1998, 1, 51–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hopkins, W.; Marshall, S.; Batterham, A.; Hanin, J. Progressive Statistics for Studies in Sports Medicine and Exercise Science. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2009, 41, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giordan, A.; De Vecchi, G. Les Origines Du Savoir: Concept, Apprenants Aux Concepts Scientifiques; Neuchâtel-Paris Delachaux Nestlé: Paris, France, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Austin, J.L. Quand Dire, C’est Faire= How to Do Things with Words; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1970. [Google Scholar]

- Ricoeur, P. Du Texte à l’action. In Essais d’herméneutique, t. 2. Média Diffusion; Seuil: Paris, France, 2013; Volume 2. [Google Scholar]

- Kerbrat-Orecchioni, C. Éthique et Ethos Dans Les Pratiques Langagières et Les Descriptions Linguistiques. In Morales Langagières Autour des Propositions de Recherche de Bernard Gardin; Caitucoli, R.D.-L.C., Ed.; Publications des universités de Rouen et du Havre: Rouen, France, 2008; pp. 73–94. [Google Scholar]

- Massey, S.L.; Pence, K.L.; Justice, L.M.; Bowles, R.P. Educators’ Use of Cognitively Challenging Questions in Economically Disadvantaged Preschool Classroom Contexts. Early Educ. Dev. 2008, 19, 340–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.; Kinzie, M.B. Teacher Question and Student Response with Regard to Cognition and Language Use. Instr. Sci. 2012, 40, 857–874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramos, A.; Coutinho, P.; Davids, K.; Mesquita, I. Developing Players’ Tactical Knowledge Using Combined Constraints-Led and Step-Game Approaches—A Longitudinal Action-Research Study. Res. Q. Exerc. Sport 2020, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gréhaigne, J.-F.; Godbout, P. Dynamic Systems Theory and Team Sport Coaching. Quest 2014, 66, 96–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).