Abstract

Many disasters occur in Japan, and therefore many initiatives to educate and integrate foreign residents into its society to overcome systematic barriers and enhance disaster preparedness have been implemented. Nevertheless, studies have highlighted foreign residents as a vulnerable group who are at risk of disasters in the country. The country anticipates and prepares for potential mega-disasters in the future; therefore, effective risk communication is vital to creating the required awareness and preparation. Therefore, this study looked at the changing foreigner–Japanese population mix in the Tokyo Metropolitan Area to ascertain its level of diversity and risk communication characteristics. It used secondary and primary data to analyze how heterogeneity among foreigners translates into a different understanding of their awareness. The study reveals that the 23 special wards within the Tokyo Metropolitan area can be compared to other recognized diverse cities in the world, with Shinjuku city, Minato city, Arakawa, and Taito cities being the most heterogeneous cities in Tokyo. Nevertheless, diversity within foreign residents creates diversity in information-gathering preferences, disaster drill participation preferences, and the overall knowledge in disaster prevention. The study suggests the use of these preferences as a tool to promote targeted risk communication mechanisms.

1. Introduction

Risk information and communication are two valuable elements highly essential to managing emergencies or disaster events. They reduce fear, anxiety and perceptions, as well as building confidence that enhances the capabilities to resist, absorb, and recover from disasters. Risk information is usually communicated throughout all the phases of disaster management cycle, i.e., the information which is essential in pre-, during-, and post-disaster situations [1]. However, studies show that pre-disaster communication (where people are informed or educated about risks and vulnerabilities) is the first vital process, with the potential of influencing behavioral change in people at risk, as well as prompting their protective actions [2]. On the other hand, when disaster strikes, a new form of urgency emerges such that it becomes vital to alert the public or relevant stakeholders of imminent dangers or threats that require immediate response or actions [3]. Therefore, a successful combination of effective communication in disaster scenarios is imperative to reducing risks and preparing for disasters. This is relevant because people become well informed and are able to make decisions based on the knowledge acquired through information sharing. Evidence shows that public awareness and disaster knowledge contribute immensely to reducing risk and enhancing resilience [4]. Hence, their importance is specifically highlighted by both the Hyogo Framework for Action (HFA2005-2015) and the Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction (2015–2030) in reducing the risk and impacts of disasters. UNISDR (2009) explains public awareness as “the extent of common knowledge about disaster risks, the factors that lead to disasters and the actions that can be taken individually and collectively to reduce exposure and vulnerability to hazards”. This presupposes that disaster knowledge is essential to improving public awareness, especially in areas with frequent disasters.

Japan, similar to many other countries, experiences disasters. Therefore, in order to equip a person to be able to take swift decisions in disaster situations, it is crucial to have initiatives, programs, and policies, on an ongoing basis, in order to promote disaster knowledge through various first-hand experiences. For instance, the Tokyo Metropolitan Fire Department utilizes simulated earthquakes to offer various levels of experience to people to better understand earthquake intensities, while the “Iza Kaeru Caravan” event also allows experiences through drills and exercises for disaster countermeasures. Other facilities include learning centers and memorial museums, all of which aim at empowering the public to be resilient to disasters [5]. Furthermore, the rise in the number of foreign nationals in the country has equally prompted additional efforts to raise public awareness of disasters. The Multicultural Coexistence Initiative (Tabunka Kyosei) and the Zero Information Refugee Project by the government represent further actions for disaster awareness that integrate foreigners into Japanese society with the aim of overcoming systematic, cultural, and linguistic barriers [6,7,8]. On the other hand, the Japan National Tourism Organization (JNTO), in collaboration with other agencies, provides various forms of information on disasters and preparedness to foreign visitors to Japan through numerous means, such as the official tourism information app “Japan Official Travel App” and the Japan Visitor hotline call service available in Chinese, English, Korean, and Japanese.

Despite these immense disaster-resilience knowledge efforts, studies suggest that there is insufficient disaster preparedness at both household and community levels in Japan [8]. Further studies reveal that this situation is highly prominent amongst foreign residents in the country, placing them among the most vulnerable populations at risk to disasters in Japan [9]. The phenomena of risk awareness and disaster preparedness of foreign nationals in Japan have received much attention from scholars and authorities in recent years. For instance, as part of Japan’s quest to make its cities and human settlements inclusive, safe, resilient, and sustainable (Sustainable Development Goal 11), Tokyo Metropolitan Area’s long-term vision, devised in December 2014, seeks to make Tokyo the world’s best city. As such, it promotes an inclusive, safe, and reliable city, capable of protecting all residents, especially foreign nationals, most of whom are the initiative’s target [10]. This also means that instances of vulnerability in foreign nationals in the cities could derail these efforts. Therefore, many studies have sought to establish the causes of vulnerabilities and have recommended various solutions [11]. However, many of these studies use the word “foreigners”, as translated from the word “gaikokujin” to represent all foreign nationals and to reach conclusions based on the broader term [10,12]. This becomes problematic because other studies recognize different categories of foreign residents’ nomenclature at the local government units [13]. Hence, other scholars advocate for going beyond a single characterization of foreign nationals or foreign residents to be able to understand their vulnerabilities and to better create sustainable and inclusive cities in Japan.

This study therefore aims to further the understanding of disaster preparedness and risk knowledge of foreign residents in Japan by categorizing the problem of the groups within the foreign residents’ community, by acquiring and analyzing secondary data regarding foreign nationals and trends in the Tokyo Metropolitan Area. It examined the Japanese–foreign residents population mix to understand its diversity within cities and used online questionnaires to sample perspectives by some foreign residents on self-characteristics and their experiences of disasters, communication, and information gathering, along with their disaster preparedness and knowledge. The study concludes by contrasting the results with other similar cases. It is based on the hypothesis that risk information and communication are hindered by certain inherent attributes of foreign nationals, affecting disaster preparedness.

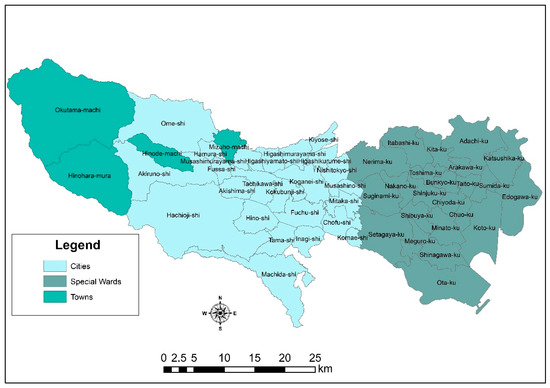

2. Tokyo Metropolitan Area

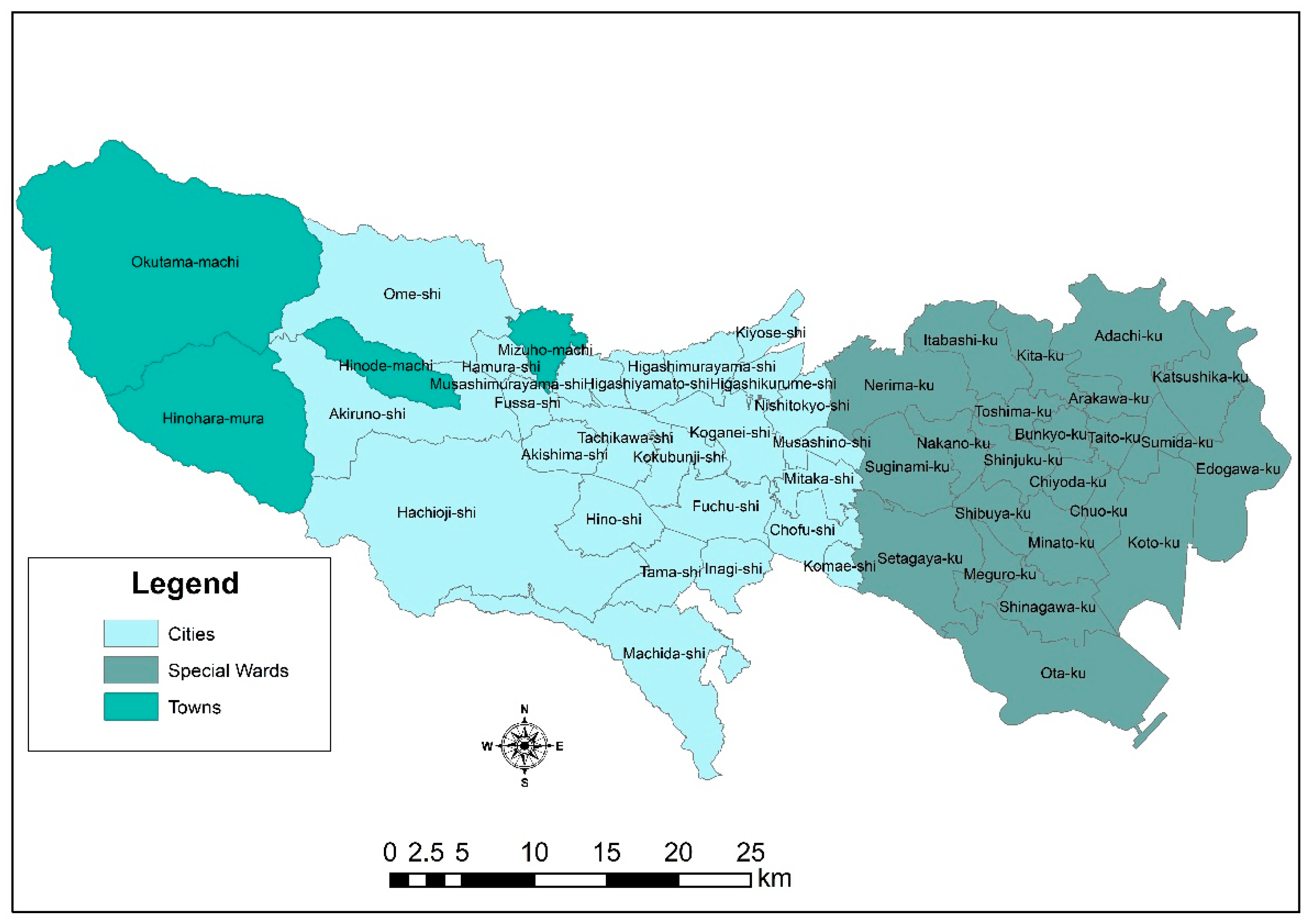

The Tokyo Metropolitan Area is located in the Kanto region on the Honshu Island of Japan. It is made up of 23 special wards, 26 cities, 3 towns, and 1 village (see Figure 1). According to official statistics, its total population as of October 2019 was 13,920,663; representing 32.03% of the total population of the Greater Tokyo area. It also accounted for 11.03% of the entire national population. The Tokyo Metropolitan Area is the most populous region of Japan, and it is equally reflected in the composition and number of foreign nationals residing in the area. Over half a million foreign nationals lived in the metropolis as of June 2019, and the top ten countries with high migrant populations are China, the Republic of Korea, Vietnam, Philippines, Nepal, Taiwan, the United States, India, Myanmar, and Thailand, in descending order. This distribution pattern is fairly representative of other prefectures such as Kanagawa, Chiba prefecture, and Saitama Prefectures. However, the distribution compositions change in other areas such as Gunma, Ibaraki, and Tochigi Prefectures where there are a significant presence of Brazilians, Vietnamese, and Filipinos. These distribution and composition patterns give a certain level of uniqueness to each prefecture. Furthermore, data from the Japanese Statistics Bureau show that each prefecture consists of over one hundred different nationalities [14].

Figure 1.

The study area: location of the Tokyo Metropolitan Area.

The realization of the significant presence of foreign nationals in prefectures has equally prompted responsive activities aimed at delivering important disaster preparedness and resilience information to the citizens and the foreign community. Therefore, a nationwide study on disaster prevention measures for foreign nationals, conducted in 2017, pointed out that local governments adopt many approaches to educate and create awareness of disaster preparedness for foreign nationals in their jurisdictions. The approaches include the use of pamphlets, brochures, production of disaster prevention leaflets, and hazard maps in four to five languages, including English, as well as the occasional organization of disaster prevention workshops and training [15]. In the Tokyo Metropolitan Area, for example, further materials include the disaster prevention booklet (Disaster Preparedness Tokyo) and the Disaster Preparedness app (Tōkyōto bōsai). These characteristics make this area an ideal test sample for this study.

3. Theoretical Review of Risk Information Communication in Disaster Risk Reduction

Information is defined in many terms depending on the context and the field of use. However, the definition by Feicheng Ma (2015) highlights key elements, such that information “eliminates uncertainties” and “offers knowledge” [16] because it is always “about something” [17]. Further studies present new viewpoints of the definition by highlighting certain components of information such as the “flow” of “something from a sender to a receiver” [18]. The use of the word “flow” in this case could be associated with the mechanism through which information from a sender travels to the receiver. This mechanism aligns with how [19] defines communication: “a process of transmitting ideas, information, attitude (by the use of symbols, words, picture, figures) from a source (who is the originator of the message) to a receiver, for the purpose of influencing with intent”. The sender is the originator, producer, or the source of the information, while the receiver becomes the intended target for whom the information is meant. Between these two components, numerous processes and connections exist which facilitate time elements such as storage mechanisms and space elements such as medium and networks [20]. Therefore, if a receiver can process and deduce the import of information from a sender, a great sense of knowledge is generated, and this potentially influences the actions taken [21].

Information communication and its subsequent influence on actions are becoming vital in recent times; the advent of disasters and the increasing vulnerabilities of economies and populations have meant that, “the extent of common knowledge about disaster risks, the factors that lead to disasters and the actions that can be taken individually and collectively to reduce exposure and vulnerability to hazards” are vital counter-measures to co-exist with disaster phenomena [22]. The new sense of knowledge acquisition and subsequent actions is what has characterized the importance of effective risk communication. Thus, it is the “process of exchanging information among interested parties about the nature, magnitude, significance, or control of a risk” with the intent of initiating actions [23].

Adapting to these new changes also aligns with the concept of disaster resilience, which is defined as the ability to plan and prepare for, absorb, recover from, and adapt to adverse events [24]. This suggests that information on risks could be transferred from a sender to a receiver to potentially offer knowledge, and to prompt the necessary actions that would prepare, adapt, and recover from disasters. Communicating risk information to generate knowledge can, however, be viewed from the perspective of risk awareness and risk reduction education; risk awareness education seeks to “impart knowledge regarding local hazard phenomena and the damaging effects these hazards may have on a society”, while risk reduction education pursues a form of awareness that “engages citizens in undertaking effective preventative and mitigation measures that can reduce exposure and vulnerability to natural hazards” [25]. However, more often than not, information fails to reach the intended target. Massa (2016) used communication theories to suggest that this happens when there are barriers in the information processing, or there is a presence of physical obstacles or choices in semantics. Others also include factors attributed to psychosocial interferences such as people’s backgrounds, perceptions, values, biases, needs, and expectations [26]. However, other studies have suggested that some of these characteristics, especially those related to physiological elements, are not readily observed. However, attributes such as gender, age, income levels, race, and ethnicity can become indicators to understand this phenomenon ([27]; p. 16).

Besides the above discussion that provides an overview of the effectiveness of delivering information to intended targets, the other side of the communication spectrum requires information to be sought, acquired, or needed by the receiver because “information has value only if it is accessible” [28]. A study by [29], and reiterated by [26], proposed that access to information consists of physical, intellectual, and social components. Physical access is made up of “the physical structures that contain information, the electronic structures that contain information, and the paths that are traveled to get to information”. Intellectual access, however, refers to “how the information is categorized, organized, displayed, and represented” [30], whilst social access offers an opportunity for everyone to access any published information, irrespective of the social and cognitive characteristics of the person [31]. However, topographical conditions, individual traits (such as physical or cognitive abilities and disabilities), language competence, and technological literacy can affect the access to information [25,28]. Therefore, it is imperative to align information delivery and accessibility components of communication, to be able to optimize a better understanding of effectiveness. Hence, some recommendation by [32] as a means of achieving effective communication seek to ask the questions:

- To what channels do audiences have access, and which do they prefer for receiving and seeking risk information?;

- Are there other channels that are used by hard-to-reach audiences?;

- What channels encourage two-way engagement with audiences, and enable interaction between decision-makers?

Answers to these questions could elucidate information delivery and accessibility in a communication system. Therefore, the above literature highlights a broader definition of risk communication; information is that “which eliminates uncertainties”, “flows” or is “transmitted” from “sender to receiver” to create knowledge which is enacted.

Based on the understanding of information and how the various elements play out, Table 1 summarizes communication and risk reduction.

Table 1.

Risk information and communication in the context of disaster resilience.

In an ordinary case, the above table would create a perfect scenario in which risk information can be communicated to enhance resilience. However, in many instances, the processes and challenges extend beyond delivery and access to information. As indicated earlier, much of an effective communication process and resilience depend on the ability to act upon the information. Rippl (2002) examined the factors that influence decisions to act on risks, and points out that individuals choose what they fear as per the relation to their ways of life, such that, “persons with hierarchic orientations are assumed to accept risks as long as decisions about those risks are justified by governmental authorities or experts”, as enshrined in the culture of the individual [33]. Hence, they urge the need to recognize the impact of culture on risk awareness, communication, and response. Nevertheless, belonging to the same culture does not necessarily mean that all members interpret or respond to a piece of information in a similar manner ([27]; p. 17), thereby opening further discussions to include individual traits in this phenomenon.

4. Methodology

The approach for this study involved the collection of views of some foreign residents as empirical data. This was to understand their information accessibility and disaster knowledge characteristics. These were then discussed considering the population composition and attributes of municipalities in the Tokyo Metropolitan Area.

The empirical data used for this study were gathered using online questionnaire administration, on the basis that nearly 85% of foreign residents are in the working-age population, aged between 14 and 64, distributed in different areas across the metropolitan area, and are engaged in many activities [34]. These pose limitations to conducting face-to-face or in-person data gathering. As outlined by Pete Comley and Jon Beaumont (2011), using an online survey curtails these obstacles by offering a sense of openness (due to the certain anonymity of participants, and the fact that they are less likely to feel inhibited in what they say), increases the geographical scope, reduces cost, and expedites responses and feedback [35].

4.1. Questionnaire Design

As stated earlier, the questionnaires for this study were also designed to capture the responses and experiences of some foreign nationals and were based on three blocks of thematic areas: self-characteristics and the experience of disasters; communication and information-gathering characteristics; and disaster preparedness and knowledge. These were gathered through a combination of open- and closed-ended questions, as well as multiple-choice questions with predefined answers to offer respondents the possibility to choose or rank. In total, forty-three questions were designed to solicit the needed information.

4.2. Pre-Testing

The questionnaires were pre-tested among selected students of the Global Resilience and Innovation Laboratory, Keio University SFC to reduce errors and ensure respondents’ understanding of the questions. This was conducted in September 2019.

4.3. Questionnaire Administration

After conducting the pre-testing to correct errors and misrepresentation of questions, they were then uploaded onto the Survey Monkey online platform. The online link to the questionnaires was then shared on Facebook, the LINE app, and other internet platforms. This period was from October to December 2019, and a total of 315 responses were received.

4.4. Method of Diversity Identification and Analysis

Entropy or diversity indexes measure the “average difference between a unit’s group proportions and that of the system as a whole” and can show the spatial distribution of multiple ethnic or cultural groups simultaneously [36]. The use of this approach in a previous study gave an indication of unique locations of foreign residents in Tokyo [11], and again became relevant in this study to understand the risk and communication issues of different categories on foreign residents. Thus, Equation (1) shows the calculation of the diversity index.

where k represents the number of nationalities, including foreign nationals and Japanese, and Pij is the proportion of the population of the jth nationality in the city i. This proportion is calculated by , where nij represents the number of the population of the jth nationality in city i, and ni is the total population in the city.

The variables representing the nationalities used included Chinese nationals, Koreans, people from Vietnam, Filipinos, Nepalese, Taiwanese, Americans, Indians, nationals from Myanmar, Thailand, Japanese, and other foreign nationals grouped under a broad category as “others” by the Japan Statistics Bureau. The depiction of the results is represented with a map generated in ArcGIS 10.4 software (a geographic information system (GIS) application by ESRI, Redlands, CA, USA).

5. Results and Findings

5.1. Visa Status Characteristics of Respondents

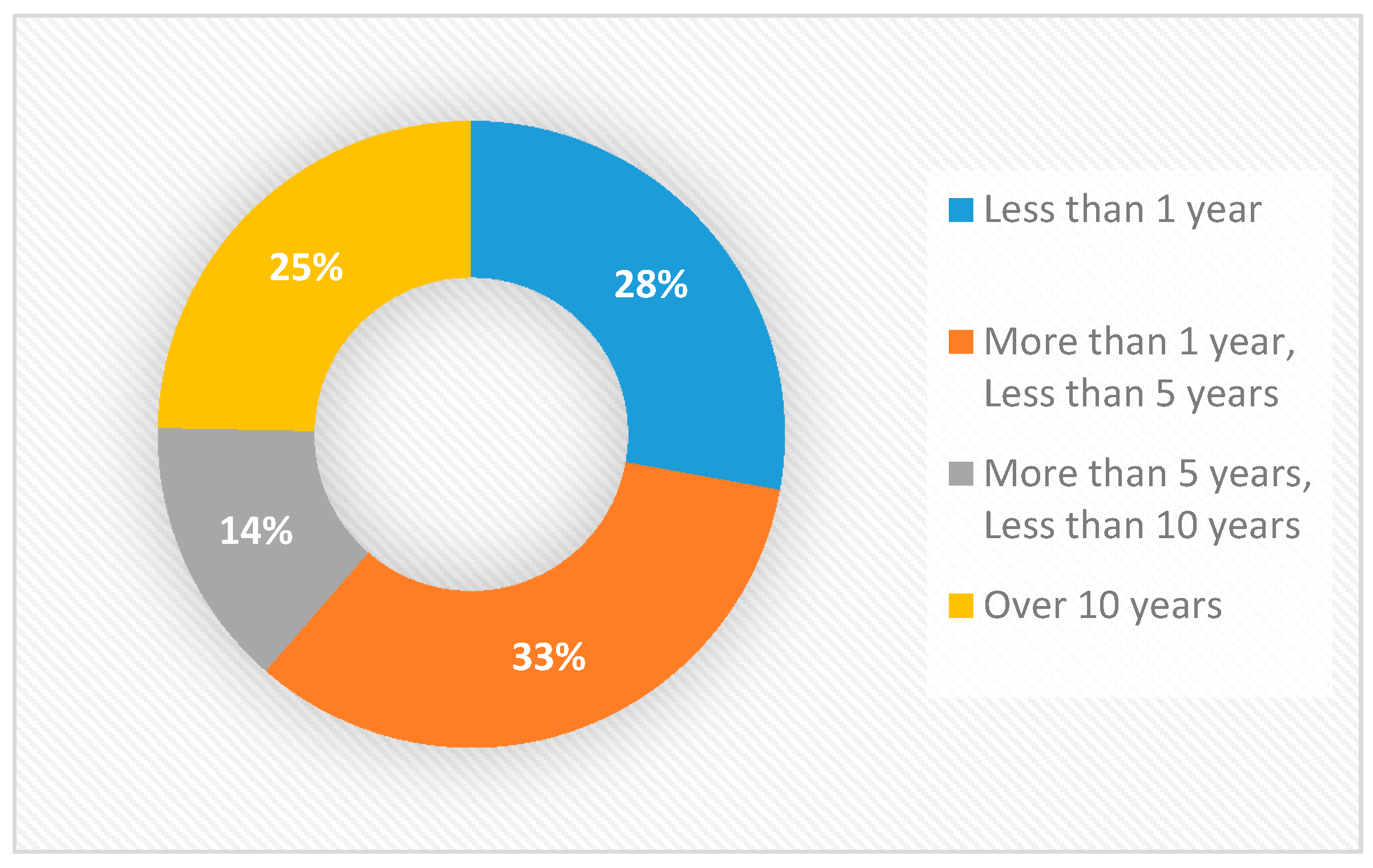

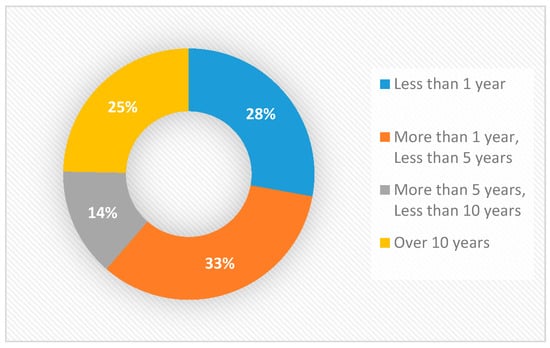

Responses from the survey showed diversity and heterogeneity in many aspects, from nationality to personal traits. In terms of nationality, respondents were from more than 30 different countries but dominated by Vietnamese (34%), Indonesians (16%), Indians (14%), and the United States (7%). From the survey, more than 30% of foreign residents had lived in the country for a period between one and five years. A substantial number, representing 25%, had spent more than 10 years living in Japan. However, within this context, about 28% could be classified as some newcomers because they had lived in Japan for less than one year, as depicted in Figure 2. The duration of residency may be essential to obtaining insights into whether a significant number of years of stay in the country affected information accessibility patterns. Therefore, of the 28% of residents who had been in Japan for less than one year, 73.9% of them were student visa-holders, indicating a possibility of longer stay beyond one year. Again, Table 2 shows that residents with working and student visa statuses constituted the highest composition, with about 34.6% and 34.9%, respectively. These are positive indications that, should there be a problem of communication or challenges in information delivery, there would be time for the revision of strategies and reimplementation, because there would be enough time for assimilation due to the majority of foreign nationals staying for a long duration. Nevertheless, there is no guarantee as to their choice of information accessibility and the influence of their respective cultures.

Figure 2.

Duration of stay in Japan.

Table 2.

Duration of stay in Japan and visa status.

5.2. Evidence of Diversity

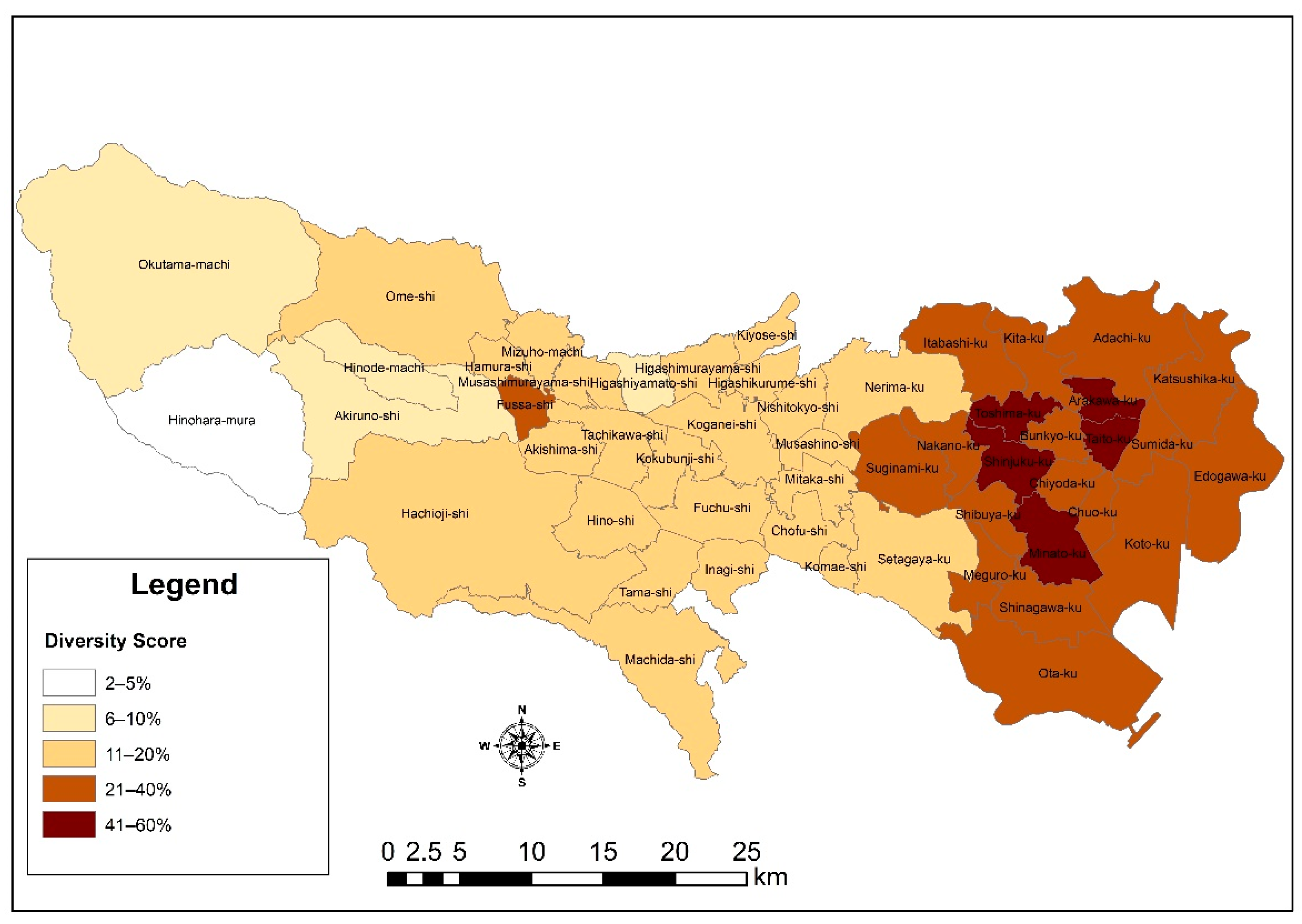

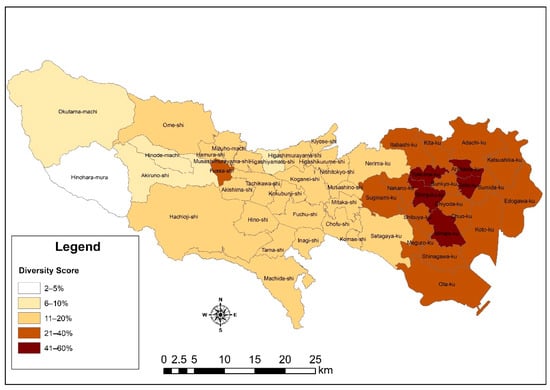

To position itself as a global hub, the Japanese government has over the years promoted initiatives such as the “internationalization of universities/schools”, “The Three Hundred Thousand International Student Plan” in 2008, and “The Global 30 Universities” since 2009 [37], to attract foreign nationals to the country. Hence, these policy reforms, together with other incentives, continue to facilitate the increase in the number of foreign nationals in Japan. An increase in the population of foreign residents also increases its heterogeneity in many ways, such that an example from the Tokyo Metropolitan Area could give a vivid account of this changing mix in population heterogeneity. As seen in Figure 3, cities within the Tokyo area show different characteristics in terms of foreign national populations and the locals. The presence of foreign residents is high from east to west, and diversifies the communities similarly. On average, the results based on Equation (1) show a diversity index of 20.17%. However, when examined from a community level or by jurisdictions, Shinjuku, Minato, Arakawa, and Taito cities are the most diverse with nearly 60%. Surrounding cities within 5–10 km also exhibit a strong level of diversity, ranging between 15% and 37% of the foreign nationals–Japanese population mix. Figure 3 further shows that the diversity levels reduce from the east of the metropolis to the west; where Okutama town, Hinohara village, and Hinode town show almost homogenous communities with nearly 3% diversity. This trend can be explained with a study by the Japanese Ministry of Land, Infrastructure, Transport, and Tourism, 2017 titled, “Report on a study on the living environment of foreigners to attract foreign companies to strengthen international competitiveness in large cities”. The report showed a high spatial distribution of international schools, English-speaking health facilities, parks, and other foreign-assisted facilities in particular areas, especially in the 23 special wards of the Tokyo Metropolitan Area. It then concludes that the location of such facilities and services are some reasons for the special wards’ attractiveness to foreign nationals [38].

Figure 3.

Diversity in population composition.

5.3. Disaster Risk Information and Accessibility Characteristics

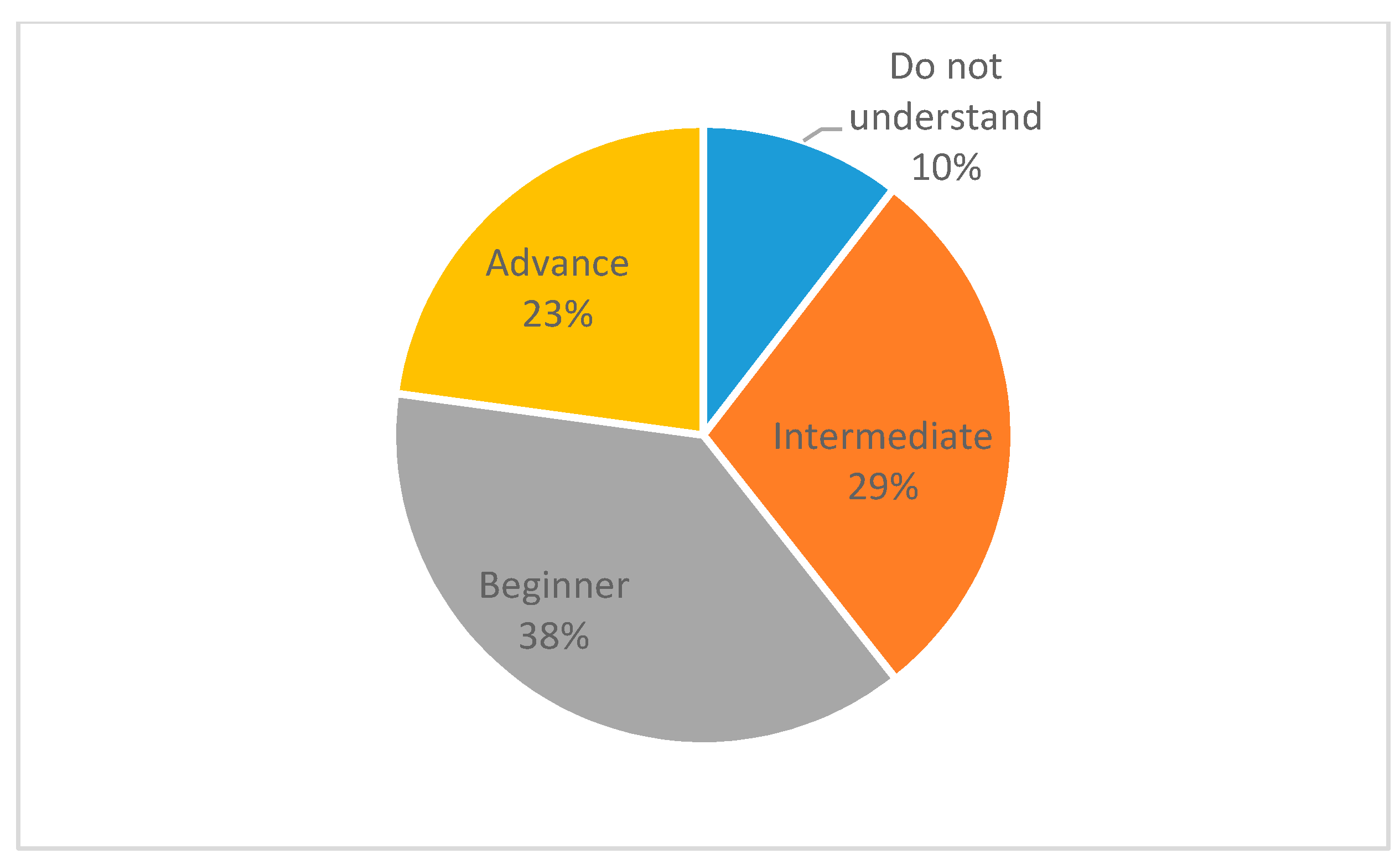

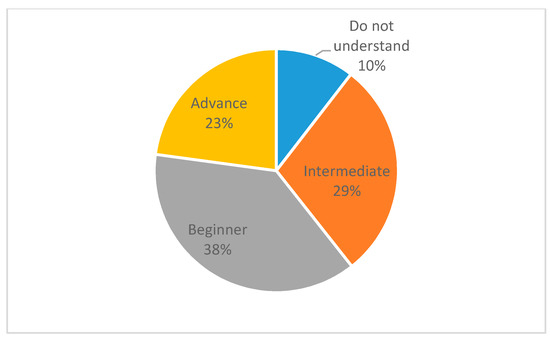

Risk communication characteristics indicate the differences in risk information accessibility and delivery. Although it is seen from the above discussion that the majority of our sample are within the “working or long term” stay visa category, Figure 4 further shows that the proficiency levels of most foreign residents differ in terms of ability. This is evidenced from the survey, because Japanese language proficiency consisted of an advanced level (23%) to zero proficiency level (10%). However, because the majority may have the opportunity to stay longer in the country based on their visas, there is the likelihood of advancement in each level of the language proficiencies. On the contrary, when searching for information on the internet, most foreign residents use the English language (52.1%) and their native language (39%), with the Japanese language being the lowest, at 5.2% (Table 3). This may be a setback to advancing proficiency levels in the Japanese language. Even though it has been found that various sources are used for information gathering, as shown in Table 3, electronic sources appeal to most foreign residents.

Figure 4.

Japanese language proficiency.

Table 3.

Language use on the Internet.

The sources of information from the survey also reflect the elements of social networking services (SNS). SNS, which are defined as an “online vehicle for creating relationships with other people who share an interest, background, or real relationship”, include Facebook, Line, Twitter, WeChat, Weibo, and WhatsApp. Within these social network platforms, the results reveal that interaction on these platforms equally follows language preference patterns. However, not so significant in comparison is the use of the Japanese language when it comes to using SNS, with a proportion of 6%. Facebook is the major source of disaster-related information, and similarly, the search for information on Facebook is performed within the English language (33%) and native language (31.4%), with little activity in Japanese (Table 3).

Interaction is another form of gaining information and knowledge; therefore, a certain level of interaction between foreign nationals and Japanese people can facilitate the process of risk communication. Hence, the results show a significant level of interaction between Japanese people and foreign residents. However, about 27.6% still have no specific interactions with Japanese people.

5.4. Disaster Knowledge and Experience

This section presents whether respondents have witnessed or experienced any form of disasters, or have participated in disaster preparedness activities, either in their respective places of origin or in Japan. It is assumed that experience and participation in disaster risk reduction activities would give certain knowledge about disaster prevention and preparedness. They would also serve as a medium to transfer or receive risk information. Therefore, from the survey, it was revealed that, just as Japan is known for many disasters, many foreign residents in the country had a certain level of knowledge on disasters. From the results, more than 80% had experienced a form of disaster in Japan, with a further 52% experiencing disasters in their country of origin. For some, disasters are a novelty (23.3%); they had neither experienced any form of disaster in their country of origin or Japan. For those who had experienced disasters in their country of origin, about 14% of them were yet to experience any form of disaster in Japan. These results indicate that policy initiatives designed for foreign residents need further discussions on scope and diversity when concerning the knowledge of disasters in the first place.

The Japanese Disaster Countermeasures Basic Act (Act No. 223, 15 November 1961) Article 7.2. stipulates that; “... residents of the area under local government are obligated to contribute toward the cause of disaster prevention by taking their own measures to prepare for disaster and by participating in voluntary disaster prevention groups”. This suggests that an individual must seek disaster prevention activities for capacity building by soliciting disaster information, partaking in disaster drills or simulations, and understanding the protocols of risk prevention to ensure that they have the needed skills and attitude. Hence, when respondents were asked about these, it was surprising that almost 70% had not participated in any form of disaster drills. Although 47.6% of respondents had not had any experience of disasters in their home countries, nearly 67.3% of this group had not made the effort to partake in any disaster simulation drills in Japan, as stipulated by law.

One may argue that the low participation in disaster simulation drills may perhaps be due to a limited stay in Japan; the person’s length of stay may not give the chance to take part in such activities. However, Table 4 indicates that, of the nearly 70% who had not taken part in disaster simulation drills, nearly 68% of them were those who had lived in the country for over one year. What is surprising is that a substantial number of this group had lived in the country for over 10 years.

Table 4.

Duration of stay and participation in disaster drills.

5.5. Disaster Preparedness

Either by experience, participation, or information gathering, respondents were asked about their preparedness with a dichotomous variable; yes or no. From this, it can be seen that 73.7% categorically stated that they were prepared, with those not prepared accounting for 26.3%. However, of the number that said “yes” they were prepared, 24.6% hardly had daily interaction with Japanese people and Facebook was their main information source (71.6%). Furthermore, among those who thought they were not prepared for disasters, nearly 64% of them had regular interaction with Japanese people, either through friends, partaking in local community events, or at schools and workplaces. However, an interesting point is that although knowledge of evacuation sites is an important aspect of disaster preparedness, and although many people said there were prepared for disasters in Japan, Table 5 shows that, for the 39.7% who said they did not know where evacuation sites were located, 55.2% are them were those who said they were prepared. Nevertheless, there was a significant number of foreign residents who knew the location of evacuation sites (60.3%), and these included those who believe they were not prepared.

Table 5.

Disaster preparedness and knowledge of evacuation sites.

Another way to improve disaster knowledge is to learn more about the modus operandi of disaster responses in the country and some countermeasures. Hence, questions were asked about where it would be convenient for each respondent to receive such education; various places were chosen. This question was asked in anticipation and recognition of the differences in ethnicity and culture. As discussed in the earlier paragraphs, it is important to consider the differences in a multi-ethnic society. Hence, although not significant, learning from the city or ward offices seemed to be the most preferred places to learn (27%), with school (24%) or via the media (24%) constituting other optional places for studies. Only 1% of respondents thought that they already knew much about disaster prevention, therefore would not need additional studies.

6. Discussion

Sato et al. (2009) argue that revisions in the Immigration Control Act triggered Japan to move towards becoming a multi-cultural society [39]. Some evidence of this assertion can be found in this study which further reinforces the point made by Sachi (2005), that Japanese societies have already become heterogeneous and multicultural [40]. Based on the diversity score of the 23 special wards of the Tokyo Metropolitan Area, it is evidence that they can be compared to other recognized culturally diverse cities such as Barcelona [41], Dublin, Limerick, and Cork [36]. However, further indication showed a great homogeneity in areas of western Tokyo; communities such as Okutama town, Hinohara village, and Hinode town had nearly 3% diversity which, when compared with the overall average of 20.17% on the diversity index, portrays contrasts to the 23 special wards. This set of scenarios could explain some cultural and ethnic identity issues in Japan. For instance, [42] asserts that identity is recognized through internal (“relationship between similar cultural groups and individuals with similar cultural backgrounds”) and external (“person within a cultural background and the relationship with the general culture of the community where the person lives”). Therefore, it is no surprise that there seems to be a nomenclature of “Japanese” and “foreigners” when it comes to the discourse of population mixes in Japan. It is through this that some aspects of risk communication are usually handled or labeled as “for foreigners” [43].

Scholars, however, caution about the general labeling of population or pan-ethnic groups, because within a population there are distinct traits and characteristics of members [41,42,43,44,45]. This study exposed such situations where the use of the broad term “foreigners” may suggest potential vulnerabilities or lack of awareness, if the responses to questions of information sources, knowledge of evacuation sites, participation in disaster drills, and language used for information gathering are considered. However, it further shows that the duration of stay in the country, as well as language abilities, play major roles in defragmenting the word “foreigners”, while giving insight to which groups may be lacking information or face challenges. As shown in the findings, many have not experienced disaster before (82%), but this is further disaggregated to show that some have taken part in disaster drill exercises, know where evacuation sites are, and have ways of accessing disaster risk information, indicating some level of risk communication and risk awareness. The use of the word “some” here should not be surprising, because only a handful of respondents who had a certain level of risk awareness had actually gone further to partake in disaster drill exercises to know what to do in the event of disasters. This is a very typical scenario, which shows that risk awareness alone may not translate into actions.

The issue of defragmenting for better results could also be found in an example of a case in the Mekong Delta in Vietnam, where an assessment of flood vulnerability showed a higher livelihood vulnerability index of Phu Huu village than that of Ta Danh village. However, a detailed probe reviewed a higher human capital index of Phu Huu village than Ta Danh village; this was highly attributed to their knowledge, skills, and various other factors [46].

On the other hand, approaching issues of communication and awareness in a diversified or defragmented population approach involves understanding if the effort of risk communication fulfills its goals. One indication to knowing if information is spread to the appropriate receiver is by knowing to what channels the audiences have access, and which do they prefer for receiving and seeking risk information [32]. As per previous studies, pamphlets, and brochures, the production of disaster prevention and hazard maps in multiple languages constitutes the major risk information dissemination avenue by local government officials [15]. However, in this study, social media (especially Facebook) is most preferred by a large section of the respondents, contrary to a previous study which attributed television to be the major source of information for some foreign residents in Japan [47]. These results, together with other studies [48], confirm that different categories of foreigners in Japan have different preferences when it comes to acquiring disaster risk information.

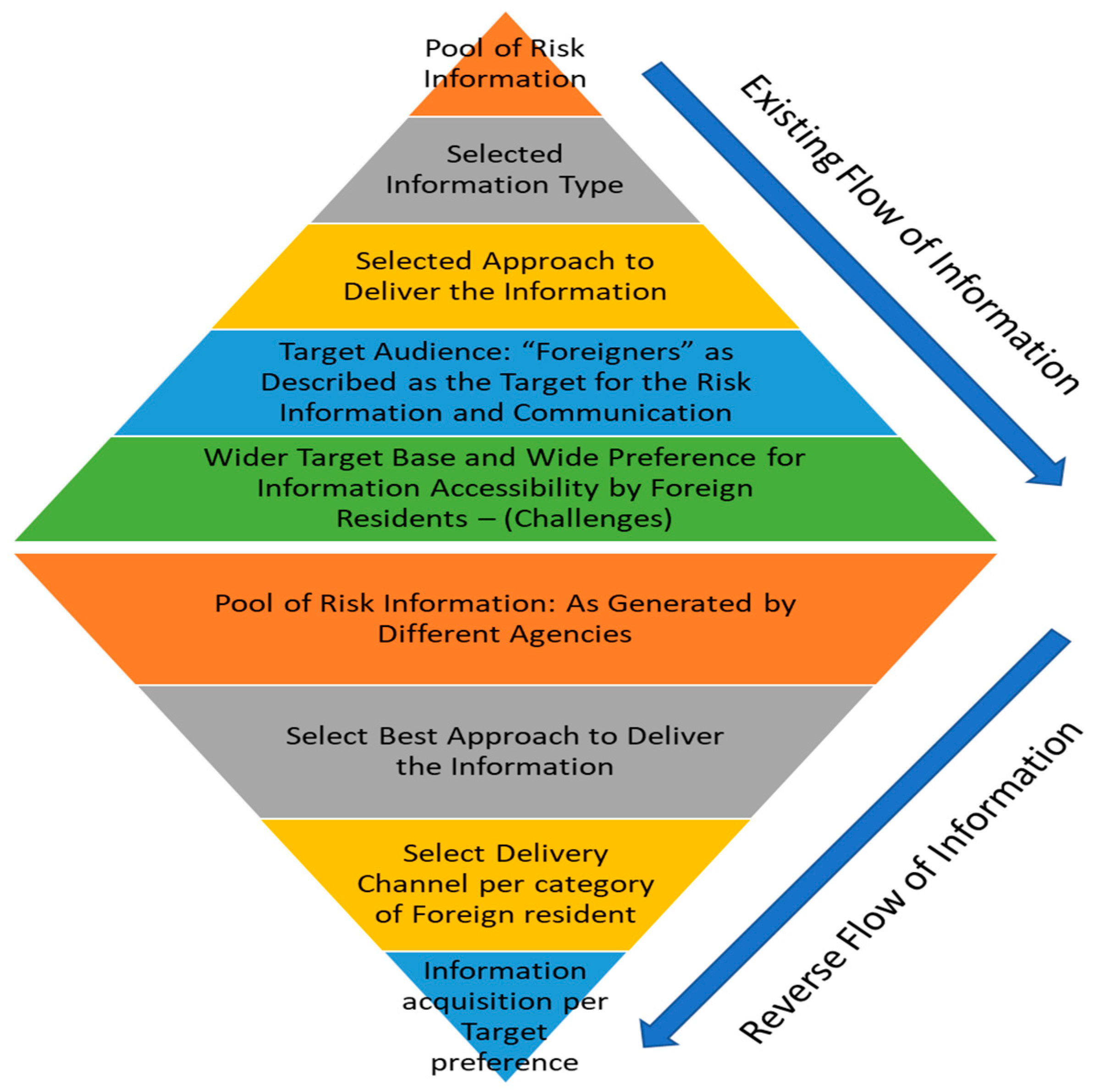

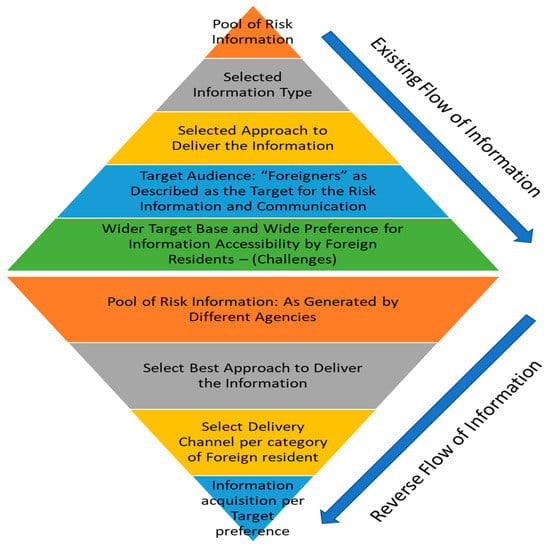

In this case, social media was most preferred by a large section of foreigners because, as presented by [49], social media is effective in receiving, delivering, and communicating urgent information, and its effective feedback mechanism plays a vital role in risk reduction. Therefore, it is evident from this study that, from the way risk information is delivered, it is changing from a specific source (usually from authorities) towards achieving or reaching foreign residents as its audience, although diversity among them, their preferences, and available communication tools broadens the reach of the envisaged target base, thereby potentially missing out on some targets. However, to effectively capture as many targets as possible, this study proposes the process to be reversed, as per a recommendation by [27] (p. 22). Thus, by carefully appreciating the unique characteristics and subcultures of a multi-ethnic society, risk communication should be framed in such a way that it considers different units within different groups of people. Hence, information with a broader base must be redesigned to ensure a narrow base that targets each set or groups of people, as shown in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

Proposed risk communication and awareness framework.

7. Implications

A major implication of the results, as indicated in this study, is a potential loss of trust in official warnings, as well as potential fake news proliferation (misinformation). Thus, the majority of foreign residents in Japan still rely on inter-ethnic, acquaintances, inter-circles, and social media for risk and resilience information. As per existing studies, these situations are vulnerable to the infiltration and influx of fake or misinformed news and information [50]. According to studies, factors such as age, culture, education, gender, and rumor-mongering within circles and networks are the major elements that fuel fake news acceptance and the proliferation of misinformation [51]. These are the same attributes that were identified in the survey conducted by this study. The effects of the inability to control this is what has characterized many countries’ efforts to provide reliable and acceptable information in the current COVID-19 pandemic. An example is an extensive effort by authorities to combat fake news hindering the fight against COVID-19 in Nigeria [52]. Hence, if authorities do not increase their presence on various social media platforms, unauthorized news and misinformation could detract from disaster prevention awareness efforts.

8. Conclusions

Policy and immigration reforms have facilitated an influx of foreign nationals to Japan; some researchers predict a probable shift from a homogenous society to a more diverse community, particularly in major urban centers such as the Tokyo Metropolitan Area. Nevertheless, Japan continues to bear the tag of a “homogenous country”. This is reflected in this study, with a low diversity score of 20% for the Tokyo Metropolitan Area. However, when examined from the local level, the 23 special wards within the Tokyo Metropolitan Area can invariably be compared to other recognized diverse cities such as Barcelona, Dublin, Limerick, Cork, and other large metropolitan areas of the world. Areas such as Shinjuku city, Minato city, Arakawa, and Taito cities are the most diverse, with nearly a 60% diversity score. However, this value reduces from the east of the Tokyo Metropolitan Area to its west, where Okutama town, Hinohara village, and Hinode town show almost homogenous communities, with nearly 3% diversity. Previous studies have outlined that the core measures for which awareness and education on risk reduction are conducted in these diversified cities are through the use of pamphlets, brochures, and the production of disaster prevention booklets and hazard maps in four to five multiple languages, translated from Japanese. There is also the occasional organization of disaster prevention workshops and training by local authorities in their local jurisdictions. Nevertheless, although more than 52% of foreign residents in this study had good proficiency in the Japanese language, English (51%) and native (43%) languages were the preferred choices to gather information. Judging by the diverse composition of foreign residents, their choice of using native language means that the effort of authorities to translate some information into English and a few other languages misses out some of the target audience.

Furthermore, the approach of using different attributes of foreign residents in Japan through the survey in this study also highlighted different risk awareness scenarios; 70% had not participated in any form of disaster drills, and nearly 68% of these were respondents who had lived in the country for over one year. This indicates that the duration of stay may not necessarily lead to knowledge gained from participating in organized disaster drills and simulations, but rather other attributes such as language, information delivery sources, and accessibility preferences all shape how knowledge and awareness are gained. The result again reinforces the point that besides defragmenting the foreign residents’ population into nationalities, religion, and other units, other elements such as the duration of stay, visa status, and integration with Japanese nationals give further understanding of risk awareness and communication within societies. Therefore, to build sustainable, safe, and inclusive cities, these factors may be relevant for consideration in all initiatives that aim to ensure effective risk communication, change in attitude for disaster prevention, and activities that promote and consider all backgrounds.

9. Limitation

The study used the entropy index to measure diversity within cities, and as shown by other studies, in this case it provided a distribution of foreign national populations within the Japanese population; however, its score alone may not give a definite situation of diversity. Further studies may be needed to correlate the diversity with its unique risk awareness and disaster preparations. Furthermore, the method used for data collection may be limited in terms of the use of the English language used in the design of the questionnaire and method of questionnaire distribution. Nevertheless, the results may be useful in planning communication and information initiatives for cities across the metropolis.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, methodology and software, B.A.-G.; validation, formal analysis, investigation, resources, B.A.-G. and R.S.; data curation, B.A.-G.; validation, writing—original draft preparation, B.A.-G.; writing—review and editing, visualization, supervision, R.S.; project administration and funding acquisition, B.A.-G. and R.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The data collection and analysis of this research was funded by the Keio University Taikichiro Mori Memorial Research Fund 2020. The APC of the paper was supported by a Keio University SFC Publication grant.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Communicating in a Crisis: Risk Communication Guidelines for Public Officials; U.S. Department of Health and Human Services: Rockville, MD, USA, 2002. Available online: https://www.hsdl.org/?view&did=440159 (accessed on 21 July 2020).

- Ng, K.L.; Hamby, D.M. Fundamentals for establishing a risk communication program. Health Phys. 1997, 73, 473–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. CERC: Introduction. 2018. Available online: https://emergency.cdc.gov/cerc/ppt/CERC_Introduction.pdf (accessed on 20 April 2020).

- Meredith, L.S.; Shugarman, L.R.; Chandra, A.; Taylor, S.L.; Stern, S.; Beckjord, E.B.; Parker, A.M.; Tanielian, T. Analysis of Risk Communication Strategies and Approaches with At-Risk Populations to Enhance Emergency Preparedness, Response, and Recovery Final Report. 2008. Available online: www.rand.org (accessed on 14 September 2020).

- The World Bank. Learning from Disaster Simulation Drills in Japan; The World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2016; Available online: https://reliefweb.int/sites/reliefweb.int/files/resources/011717drmhubtokyoLearningFromDisasterSimulationDrillsinJapan.pdf (accessed on 9 January 2021).

- Nagy, S. Japanese-style Multiculturalism? A Comparative Examination of the Japanese Coexistence. J. Multiling. Multicult. 2012, 18, 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Cao, H.; Morrell, E. Regional Minorities and Development in Asia; Amsterdam University Press: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Tomio, J.; Sato, H.; Matsuda, Y.; Koga, T.; Mizumura, H. Household and Community Disaster Preparedness in Japanese Provincial City: A Population-Based Household Survey. Adv. Anthropol. 2014, 4, 68–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kataoka, H. ‘Foreigners’ in regional disaster prevention: A consideration for re-questioning ‘local communities’ from ethnicity research. Geogr. Space 2017, 9, 285–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tokyo Metropolitan Government. Tokyo Long-Term Vision. 2016. Available online: https://www.seisakukikaku.metro.tokyo.lg.jp/tokyo_vision/vision_index/index.html (accessed on 7 April 2021).

- Adu-Gyamfi, B.; Shaw, R. Utilizing population distribution patterns for disaster vulnerability assessment: Case of foreign residents in the Tokyo metropolitan area of Japan. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 4061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hada, Y. Current Situation and Issues in Providing Disaster Information to International Visitors in Japan. IATSS Rev. 2020, 45, 28–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aiden, H.S. Creating the multicultural coexistence society: Central and local government policies towards foreign residents in Japan. Soc. Sci. Jpn. J. 2011, 14, 213–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Japan Statistics Bureau. Statistics Bureau Japan Statistical Yearbook 2019—Chapter 2 Population and Households. 2020. Available online: https://www.stat.go.jp/english/data/nenkan/68nenkan/1431-02.html (accessed on 6 December 2020).

- Institute of Scientific Approaches for Fire and Disaster Prevention. Questionnaire Survey Results on the Current Status of Disaster Prevention Measures for Foreigners in Municipalities. Firef. Disaster Prev. Sci. 2017, 130, 46–49. Available online: https://www.isad.or.jp/pdf/information_provision/information_provision/no130/46p.pdf (accessed on 22 June 2020).

- Ma, F. On Information 1.1 Concept of information. In Information Communication; Morgan Publisher; Claypool Publisher: San Rafael, CA, USA, 2015; pp. 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Loose, R.M. A Discipline Independent Definition of Information. Am. Soc. Inf. Sci. 1998, 48, 254–269. Available online: https://ils.unc.edu/~losee/book5.pdf (accessed on 14 June 2020). [CrossRef]

- Capurro, R.; Hjørland, B. The concept of information. Annu. Rev. Inf. Sci. Technol. 2005, 37, 343–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Youssef, I.M.A. Communication Skills. Cairo Egypt. 2005. Available online: www.capscu.com (accessed on 16 August 2020).

- Heath, R.L.; Johansen, W.; Ruler, B. Communication Theory. In The International Encyclopedia of Strategic Communication; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2018; pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, F. Basic Concepts of Information Communication 2.1 Classification of information communication. In Information Communcation; Morgan Publisher; Claypool Publisher: San Rafael, CA, USA, 2015; pp. 15–21. [Google Scholar]

- UNISDR. Terminology on Disaster Risk Reduction; Geneva, Switzerland, 2009. Available online: https://www.preventionweb.net/files/7817_UNISDRTerminologyEnglish.pdf (accessed on 7 February 2021).

- Miller, S.; France, D.; Welsh, K. Development of Crisis and Emergency Risk Communication (CERC) activities and an evaluation of their impact on learning: Geoscience students’ perceptions. Belgeo. Rev. Belg. De Géograph. 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larkin, S.; Fox-Lent, C.; Eisenberg, D.A.; Trump, B.D.; Wallace, S.; Chadderton, C.; Linkov, I. Benchmarking agency and organizational practices in resilience decision making. Environ. Syst. Decis. 2015, 35, 185–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. Risk Awareness, Capital Markets and Catastrophic Risks, No. 14; OECD: Paris, France, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Massa, M.E. Dynamics of Communication Barriers on Public Institutions; The Case of NDU Council, North West Region Cameroon. Int. J. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Educ. 2016, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindell, M.K.; Perry, R.W. Communicating Environmental Risk in Multiethnic Communities; SAGE Publications Inc.: Los Angeles: CA, USA, 2004; Volume 7. [Google Scholar]

- Burden, P.R. The Key to Intellectual Freedom Is Universal Access to Information. 2000. Available online: http://keytoinformation.blogspot.com/2008/12/insi-rep-ofindia.html (accessed on 22 May 2020).

- Burnett, G.; Jaeger, P.T.; Thompson, K.M. Normative behavior and information: The social aspects of information access. Libr. Inf. Sci. Res. 2008, 30, 56–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaeger, C.A.B.; Jaeger, P.T. Access and Accessibility. In Understanding Disability: Inclusion, Access, Diversity, and Civil Rights; Jaeger, P.T., Bowman, C.A., Jaeger, P.T., Eds.; ABC-CLIO, LLC: Santa Barbara, CA, USA, 2005; p. 67. [Google Scholar]

- Nasir, M.; Alzoubi, R.; Khedr, A.; Altamimi, A.; Aqib, J.; Khder, A.; Ramadan, R. Social Accessibility: Issues, Standards, and Tools. Int. Conf. Recent Adv. Comput. Syst. 2016, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO. WHO Strategic Communications Framework for Effective Communications; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Rippl, S. Cultural theory and risk perception: A proposal for a better measurement. J. Risk Res. 2002, 5, 147–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minako, Y. Foreigners in Japan Hit Record as Tokyo Rolls out Welcome Mat—Nikkei Asia. Nikkei Asian Rev. 2019. Available online: https://asia.nikkei.com/Spotlight/Japan-immigration/Foreigners-in-Japan-hit-record-as-Tokyo-rolls-out-welcome-mat (accessed on 22 May 2020).

- Comley, P.; Beaumont, J. Online research: Methods, benefits and issues—Part 2. J. Direct Data Digit. Mark. Pract. 2011, 13, 25–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fahey, É.; Russell, H.; McGinnity, F.; Grotti, R. Diverse Neighbourhoods: An Analysis of the Residential Distribution of Immigrants in Ireland; ESRI: Dublin, Ireland, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kobayashi, N. Mapping Internationalization in Higher Education in Japan. 2013. Available online: https://www.he.u-tokyo.ac.jp/wp-content/uploads/2014/04/CRDHE-working-paper-7.pdf (accessed on 11 July 2020).

- Ministry of Land, Infrastructure, Transport and Tourism: Tokyo, Japan. Report on a Study on the Living Environment of Foreigners to Attract Foreign Companies to Strengthen International Competitiveness in Large Cities; Tokyo, Japan, 2017. Available online: https://www.mlit.go.jp/common/001184447.pdf (accessed on 14 July 2020).

- Sato, M.M.K.; Okamoto, K. Japan, Moving Towards Becoming a Multi-cultural Society, and the Way of Disseminating Multilingual Disaster Information to Non-Japanese Speakers. In Proceedings of the 2009 International Workshop on Intercultural Collaboration, Palo Alto, CA, USA, 20–21 February 2008; p. 312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sachi, T. Multiculturalism in Japan: A Victor y over Assimilationism or Subjection to Neo-Liberalism? Ritsumeikan Lang. Cult. Res. 2005, 18, 3. [Google Scholar]

- Galeano, J.; Bayona-I-Carrasco, J. Residential segregation and clustering dynamics of migrants in the metropolitan area of Barcelona. Quetelet J. 2018, 6, 99–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucini, B. Multicultural Approaches to Disaster and Cultural Resilience. How to Consider them to Improve Disaster Management and Prevention: The Italian case of two Earthquakes. Procedia Econ. Financ. 2014, 18, 151–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okinawa International Exchange & Human Resources Development Foundation. Disaster Prevention Handbook for Foreigners; Okinawa International Exchange & Human Resources Development Foundation: Ginowan, Japan, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Masuoka, N. Together They Become One: Examining the Predictors of Panethnic Group Consciousness among Asian Americans and Latinos. Soc. Sci. Q. 2006, 87, 993–1011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, M. Residential Integration on the New Frontier: Immigrant Segregation in Established and New Destinations. Demography 2013, 50, 1873–1896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Can, N.D.; Tu, V.H.; Hoanh, C.T. Application of livelihood vulnerability index to assess risks from flood vulnerability and climate variability—A case study in the Mekong Delta of Vietnam. J. Environ. Sci. Eng. 2013, 2, 476–486. [Google Scholar]

- Ikuyo, K. Issues Faced by Foreigners in the Event of a Disaster-Considering How Information Should Be Disseminated; Fukuoka, Japan, 2020. Available online: http://urc.or.jp/wp-content/uploads/2020/02/3kikusawa.pdf (accessed on 11 September 2020).

- Yonekura, T. Media use and Information Behavior of Foreign Residents in Japan during a Disaster; Tokyo, Japan, 2012. Available online: https://www.nhk.or.jp/bunken/summary/research/report/2012_08/20120805.pdf (accessed on 5 July 2020).

- Alexander, D.E. Social Media in Disaster Risk Reduction and Crisis Management. Sci. Eng. Ethics 2014, 20, 717–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones-Jang, S.M.; Mortensen, T.; Liu, J. Does Media Literacy Help Identification of Fake News? Information Literacy Helps, but Other Literacies Don’t. Am. Behav. Sci. 2021, 65, 371–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stabile, B.; Grant, A.; Purohit, H.; Harris, K. Sex, Lies, and Stereotypes: Gendered Implications of Fake News for Women in Politics. Public Integr. 2019, 21, 491–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO. Inoculating against the ‘Infodemic’ in Africa. 2020. Available online: https://www.afro.who.int/news/inoculating-against-infodemic-africa (accessed on 18 February 2021).

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).