Abstract

Employee retention is becoming a major concern in organizational management. To maintain business’ competitive advantages, companies need to keep employees working for their organizations. Thus, many firms are trying to find out how to retain their employees. This study aims to investigate determinants of employee retention of South Korean construction employees. From the review of the literature and discussions with industrial practitioners, eight significant determinants affecting employee retention in South Korean construction firms are identified. The fuzzy technique for order of preference by similarity to ideal solution (TOPSIS) is employed to prioritize the identified determinants. The fuzzy TOPSIS analysis shows that personal characteristics, personal development, promotion opportunities, and work-life balance are the four most critical determinants. Construction firms are suggested to focus on these determinants to improve employee retention rates within their companies and achieve sustainable development.

1. Introduction

Employee retention is becoming a major concern in organizational management. In this fierce global business competition, the shortfall of the workforce in many industrial economies has required employers to show their ability to keep employees working for their organizations to maintain business competitive advantages [1]. However, Burke and Ng [2] acknowledged a growing number of employees do not want to have a traditional career within one organization, possibly because they have a greater choice in pursuing careers across an increasing number of companies [1]. Therefore, today workers seem to be more opportunistic of work opportunities and less loyal than their counterparts in the past. High employee turnover rates have been unsurprisingly witnessed in the oil and gas [3], travel [4], and construction industries [5]. Companies may face substantial risks of losing confidential information to competitors since skilled employees can take a lot of know-how with them. In such a case, losing employees does not solely mean a loss of human investment but also business survival.

The construction industry plays a vital role in all national economies that employ a large proportion of employees in the labor market [6]. As a large number of employees is required for business operation, losing such employees may lead to significant losses for recruiting and training. The review of the literature [5] highlighted that a high labor turnover rate negatively influences organizational productivity and performance since most of the resource utilization is heavily dependent on the workforce. Employee retention then becomes necessarily important in construction firms [5].

Unlike other industries, construction is a project-oriented [7] and highly fragmented industry [8]. Construction projects are naturally complex and are subject to a multitude of random internal (i.e., human resources) and external factors (i.e., political and economic factors) [9]. Moreover, construction projects are commonly located in dispersed locations and performed independently by a unique collection of project teams. Consequently, construction workers have to change their working locations frequently. Researchers showed that workers in the construction industry normally suffer from high rates of mental health problems [10] and on-site accidents [11] but not all of them are offered sufficient health insurance [12]. Moreover, construction projects are becoming more complex and challenging [13]. Therefore, it is highly possible that employees will search for another job which provides them better work conditions.

Acknowledging the negative effects of high labor turnover rates in construction businesses, this research focuses on analyzing the determinants that influence employee retention. Basically, job satisfaction and organizational commitment increase the intention to stay of the employees and then reduce the turnover rate within organizations [1,14,15]. Specifically, Currivan [14] confirmed that workplace structure and individual characteristics-related factors affect employee satisfaction, organizational commitment, and then employee retention. To improve employee satisfaction and organizational commitment, specific factors have been identified such as improving the job environment, giving fair and competitive compensation packages, providing clear employee development plans and career growth opportunities [5,12,16,17,18]. Although several factors may affect the level of employee retention within construction firms, the improvement of employee retention requires careful consideration of scarce organizational resources with an emphasis on the most important determinants. The identification and prioritization of employee retention determinants are heavily affected by the research context and remained a problem for decision-makers in organizations.

As stated by Coetzee and Stoltz [19], Kim [20], and Yamamoto [21], the assessment and evaluation of employee retention contains multi-level and multi-factor features, so such difficulties can be considered as multiple criteria decision-making (MCDM). Among numerous MCDM methods, the TOPSIS (Technique for Order Preference by Similarity to Ideal Solution) has been widely employed in previous studies with satisfactory results [22,23,24,25]. Therefore, this research applies TOPSIS to evaluate the importance weights of evaluation criteria. Previous studies noticed the different advantages of TOPSIS in the evaluation of multi-level and multi-factor features. Wang and Chang [26] highlighted the concept of TOPSIS permits the pursuit of best alternatives for each criterion shown in a simple mathematical form. Moreover, Dandage et al. [27] argued TOPSIS logic is rational and understandable with straightforward computation processes. Normally, decision-makers have to deal with uncertain problems under complex circumstances. These issues are understandable because the natural language to express judgment and opinion is normally uncertain, subjective, or vague [26]. Subjectivity, uncertainty, and ambiguity usually exist in the evaluation of the employee retention process and were not easily solved until the development of Zadeh’s fuzzy sets theory [28]. Hence, the use of TOPSIS under a fuzzy environment is reasonable to achieve the research objectives.

The above discussions show that construction firms face unique difficulties in improving the employee retention rate, which may be different from the other business sectors. Thus, it is imperative to investigate the determinants that influence employee retention in construction firms. In making its case, this study focuses on ranking determinants of employee retention of construction employees in the context of the South Korean construction industry based on their effect on two dimensions, namely, job satisfaction and organizational commitment. First, the determinants of employee retention in construction firms are identified through a review of the literature and discussions with construction employees. Second, the fuzzy technique for order of preference by similarity to ideal solution (TOPSIS) is employed to rank the identified determinants. The findings of this research will provide construction firms with the prioritization of determinants of employee retention; thus, supporting the improvement of the employee retention rate to maintain business competitiveness.

The rest of the paper is organized as follows: the next section presents the literature on employee retention, determinants of employee retention, and the current status of the South Korean construction industry. This is followed by the presentation of the research methodology in Section 3. Subsequently, Section 4 shows the analysis of fuzzy TOPSIS to rank the determinants of employee retention. Finally, Section 5 discusses the research findings, limitations, and proposes future research directions to enhance the understanding and knowledge of employee retention.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Employee Retention

Although advancement in technologies has allowed for the replacement of workers in many business stages, employees have still served as a crucial resource of any organization. The value of employees has even increasingly become important because many modern technologies are not able to efficiently and effectively operate without the collaboration of skillful and knowledgeable employees [29]. In this situation, human resources become a business advantage of organizations. Consequently, organizations should not only focus on recruiting new talents but also retaining the current ones for the long term.

In contrast to employee turnover which is used “when employees change organizations, professions, and stay on full employment condition while not working” [5], employee retention refers to “a systematic effort to create and foster an environment that encourages employees to remain employed by having policies and practices in place that address their diverse needs” [29]. According to Kyndt et al. [1], Coetzee and Stoltz [19], and Currivan [14], employee retention can be reflected through job satisfaction and organizational commitment dimensions.

Job satisfaction is used to portray whether employees are happy, contented and whether their needs and desires are fulfilled at the workplace [30]. Skaalvik and Skaalvik [31] defined job satisfaction as employees’ feeling toward the job and argued that job satisfaction occurs when their job expectations match the real outcomes. Kim et al. [32] also noticed that job satisfaction is the employees’ attitude with their jobs and job-related factors such as the working conditions, working environment, and communication with their coworkers. Ocen et al. [33] categorized job satisfaction as extrinsic and intrinsic job-related factors. While extrinsic factors consist of all the external factors an employee is satisfied with such as supervisor cooperation, communication style, pay, and working conditions, intrinsic factors consist of the types of work that employees do and the employees’ duty. Researchers have found that if employees do not obtain job satisfaction, they are likely to leave their organization [30].

In this study, organizational commitment refers to employee commitment to its organizations. Indeed, “employees with a high organizational commitment are those who have a strong identification with the organization, value the sense of membership within it, agree with its objectives and value systems, are likely to remain in it and, finally, are prepared to work hard on its behalf” [1]. Famakin and Abisuga [34] and Dyk and Coetzee [35] grouped organizational commitment into three categories, affective commitment, continuance commitment, and normative commitment. Indeed, affective commitment mentions employee involvement, identification, and emotional attachment with its organization and goals [36]. Continuance commitment refers to the willingness to remain of an employee in the organization due to non-transferable investments the employee has that are irreplaceable to the organization, such as relationships with other employees, retirement benefits, and giving up seniority-based privileges. Normative commitment links to the feeling of the moral obligation of an employee to its organization.

2.2. The South Korean Construction Industry

The construction industry plays a vital role in the South Korean economy [37]. It is witnessed that the national economy is increasingly being over-dependent on its construction industry as more than half of economic growth has been contributed by construction investments in recent years [38]. Construction companies account for around 7.7% of the total employment of the nation [37]. However, Benghida [38] documented that the South Korean authorities have to invest a large amount of money to attract more skilled workmanship as skills shortage of construction workers. The sector has a demanding work environment that construction workers must face with many job-related stressors regarding the threat of penalties for project time and cost overruns [39]. Moreover, because of the centrality of work and high power distance culture, South Korean employees face excessive pressures at work [40]. Specifically, Kim et al. [40] argued that while empowerment is given at the organizational level in the western context, it is much more associated with the individual level in the Asian context. In other words, managers in the Asian context (i.e., South Korea) accredit much to reliable employees that they like and trust. It may then create a situation, in the context of voluntary turnover, that “employees don’t quit their companies, they quit their bosses” [41]. Annual reports from the Ministry of Employment and Labor presented that construction has high incident rates with many occupational accidents [42]. Besides, the mortality rate is documented as the highest among all the other business industries [42]. Kim et al. [43] acknowledged the shortfall in the workforce in South Korea, thus struggling to satisfy demands for both skilled and unskilled labor. Meanwhile, today workers have a wide range of job opportunities in different business sectors. Thus, South Korean construction firms may face substantial difficulties in keeping employees to work within their organizations.

2.3. Determinants of Employee Retention

The review of the literature [18,44] highlighted that employee retention initiative is not only influenced by a single factor, but by a large number of determinants that are responsible for retaining them in an organization. Based on the research outputs of various studies, eight determinants of employee retention are explained as follows.

DER1: Employee income. Income is one of the most important rewards that employees receive from what they have contributed to the organization. Previous studies [21,45] have demonstrated a significant relationship between the level of employee income and job satisfaction. Employees may have a higher level of job satisfaction when they are receiving a higher income for their efforts. In cases where an employee believes that he/she works harder than another one who receives a higher compensation rate, employee income may become an extremely important factor that encourages him/her to leave the current position and to search for other job opportunities.

DER2: Work environment. A supportive work environment has a positive relationship with employee retention [41]. If employees feel the organization work environment is characterized by appropriate work ethic [16], job security [46], good working relationship among coworkers [47], and employee involvement in decision making [16], they may have a strong sense of belonging which enhances their organizational commitment levels for the long term [18]. Mohyin et al. [48] acknowledged that employee involvement refers to the efforts of the organizations in allowing their employees to make an impact on jobs related decisions. Thus, this policy gives the employees more empowerment which enhances employee commitment.

DER3: Promotion opportunities. Employees expect the acknowledgment of contributions to their organizations. Promotion prospects become an important aspect of achieving job satisfaction and reducing turnover retention [35,46]. Parker and Skitmore [49] identified promotion as one of the leading factors causing turnover of organizational performance. A study of civil engineers in Australia highlighted that employees who are satisfied with promotion prospects will have less cynicism with their job, thus lowering the turnover rate [39]. Kyndt et al. [1] noticed that once top employees think they have fewer career advancement and promotion opportunities, they may start to look externally for other job opportunities.

DER4: Company images and development. Companies worldwide are implementing several efforts to improve their image, thus boosting business performance [50]. In this study, the image stands for the set of perceptions, impressions, expectations, beliefs, and attitudes that internal and external stakeholders have about the company [51]. Herrbach and Mignonac [52] acknowledged that organizational image affects employee attitudes. Riordan et al. [53] emphasized the relationship between employee’s perceptions of company image and two specific variables, namely job satisfaction and intentions to quit. Moreover, companies that show their sustainable and continuous development can earn trust from their employees, thus increasing employee commitment.

DER5: Employment welfare. Kundu and Lata [41] recognized that a high employee retention rate may be witnessed when employees’ contributions are recognized and their welfare is sufficiently provided. Welfare is a strong tool to enhance employee motivation in organization retention [4,44]. Employees may then feel obliged to reciprocate these helpful policies with favorable behaviors and attitudes [54]. Famakin and Abisuga [34] acknowledged that displaying concern for employee welfare show a supportive leadership style within the company, which is essential in the alleviation of frustration and stress reduction. Yamamoto [21] linked employee welfare and employee benefits management, which creates family-friendly work styles [32].

DER6: Work-life balance. The construction industry is characterized by a high workload and long working hours. Sang et al. [46] highlighted poor work-life balance as one of the leading stressors which potentially negatively impact employees in the construction industry. Moreover, work-life balance enables the achievement of good mental health [21]. Therefore, work-life balance is considered as one of the most important employee-centered human resource policies among organizations [35]. Coetzee and Stoltz [19] investigated that work-life balance is a crucial factor in determining employee retention. Those who have work-life balance conflicts are less satisfied with their job and then show a strong turnover intention [46].

DER7: Personal development. Researchers have demonstrated training programs operated by organizations influence employee commitment [33]. Employees would have a higher intention rate if their organizations invest in their career development. Borstorff and Marker [55] witnessed that career growth, learning and development, meaningful work, and exciting work and challenge are the pivotal retention factors. The study in Japan [21] also agreed that training and development are essential in human resource management that foster employee retention. In Australia, Hee and Ling [16] suggested appropriate training schemes would enable quantity surveyors to develop new skills that help them to achieve job satisfaction.

DER8: Personal characteristics. Previous studies [1,56] have found that employees have multiple characteristics such as creativity, leadership, learning potential, and autonomy. While these characteristics are helpful in coping with flexibility and stress at workplace, it reflects the diversity of employees’ personalities and affects their intention to stay in the organizations [1]. Coffey [56] also noticed that these personal characteristics would affect the desire to be involved in the employees. If the employees feel they are not suitable for the work environment and the organization culture, they might notice somehow wrong which results in a feeling of not belonging [31].

2.4. Research Gap

The body of literature on labor retention in business organizations suggests changes in approach to examine the phenomenon. Previously, most turnover theories are established on the seminal research proposed by March and Simon [5], which focused on the idea of job alternatives and job dissatisfaction. In the 1990s, there was a significant paradigm shift toward a new approach that combines the image theory (constant information disclosure results in behavioral changes) and the voluntary turnover model [57]. Since then, studies on employee retention have emphasized refining this model and theory to foster understanding of the relationship between employee retention and organizational performance [1,35]. The 21st century has witnessed a new wave of studies that examine novel theories to interpret the employee retention phenomenon and its associated behaviors. These cover the job embeddedness theory [35], collective turnover model [5], and employee empowerment [40].

Discussions presented in Section 2.1 and Section 2.2 illustrate much of prior literature aimed to gain insight into understanding determinants of employee retention in several business industries, including construction. The construction sector is one of the largest employment industries but suffers from reduced labor productivity, severe skills shortage, and high absenteeism and labor turnover [39,43]. Ayodele et al. [5] highlighted productivity in construction firms may be negatively affected by a high labor turnover rate because most of the resource utilization is largely dependent on the workforce. Hence, construction firms have to explore and grasp the underlying factors that contribute to employee retention [34,46,58]. In this case, understanding and evaluating the factors which mostly affect employee retention in construction firms become critical. However, to the best of our knowledge, there is a lack of studies that emphasize ranking the determinants of employee retention in the context of the construction industry. The evolution of labor retention research highlights the requirements to contextualize and align employee retention according to turnover antecedents and the identification of employee motivations to stay. Employee retention is affected by working culture, which is determined and differentiated from different geographical locations. South Korea is an Asian country with unique working cultures [40]. Therefore, it is essential to examine determinants of employee retention to foster the success of human resources management in South Korean construction firms, which is the focus of this study.

3. Methodology

3.1. Research Plan

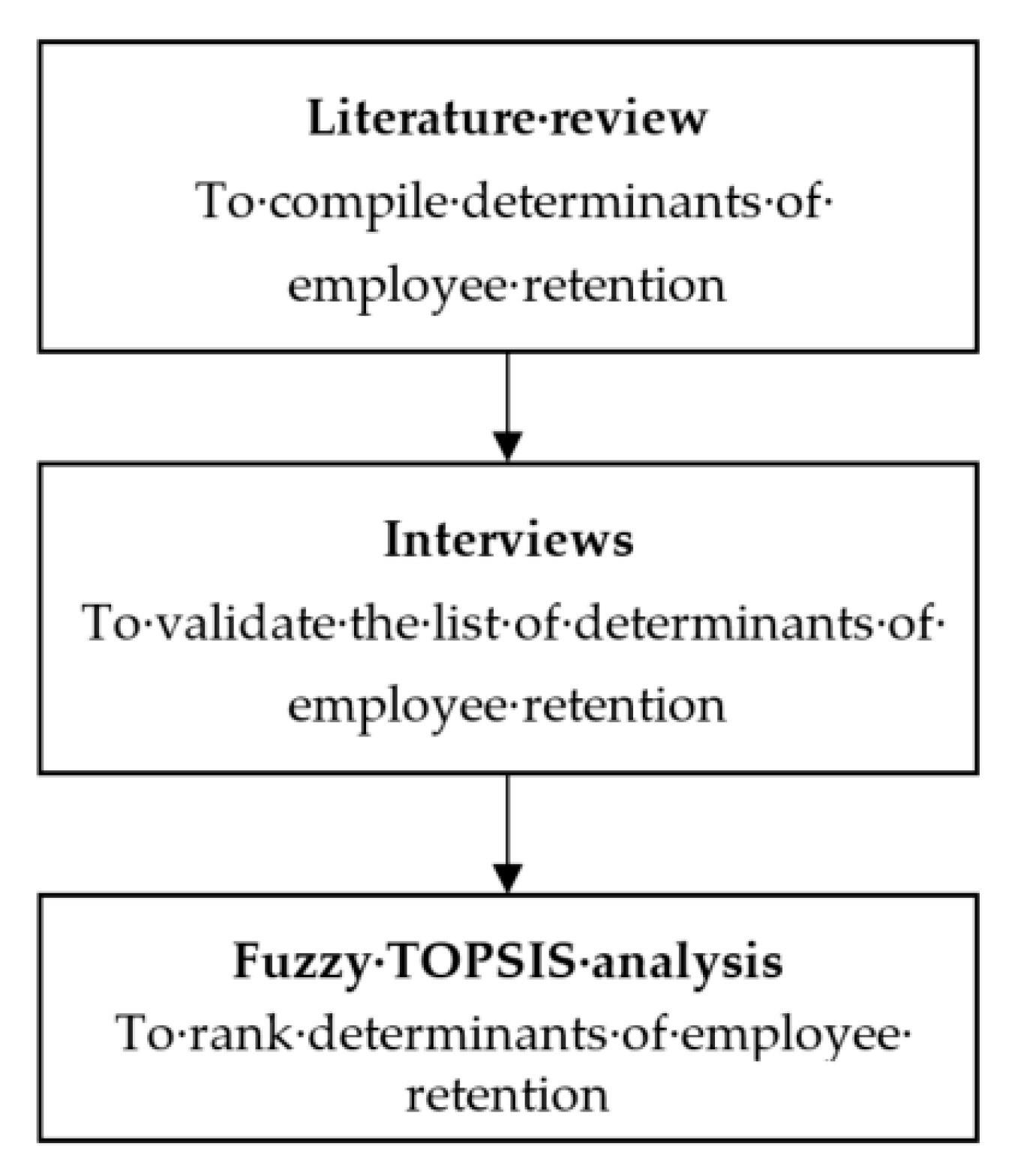

This study employs both qualitative and quantitative methods. First, previous studies were analyzed to compile the initial list of determinants of employee retention. Interviews then conducted with experts who had experience in human resources management in South Korean construction firms to validate and finalize the list of determinants of employee retention in the research context. Finally, the TOPSIS method was employed to prioritize the determinants of employee retention under two dimensions of job satisfaction and organizational commitment in the fuzzy environment. Figure 1 illustrates the research plan of this study.

Figure 1.

Research plan.

3.2. Interviews

The identification of eight employee retention determinants became the inputs of the interviews with experts who had solid experiences in human resources management in the South Korean construction companies. Fourteen experts who had more than ten years of working and hold manager positions in South Korean construction firms were invited to discuss with semi-structured questions. More than half (57%) of the respondents were line managers and engineers, followed by functional managers (29%) and top management (14 percent). In terms of the number of years of construction involvement, proportions of the respondents were: less than or equal to 10 years (36%), between 10 and 16 years (36%), and 20 years or more (28%). Each expert was delivered a list of eight employee retention determinants with detailed descriptions. The experts were asked questions such as:

- In your opinion, which determinants are suitable in the South Korean construction industry?

- Please propose other determinants that may impact the level of employee retention in the South Korean construction industry?

Additionally, the authors had discussed with the experts about the applicability of the predefined determinants and how they work in the research context. Finally, all experts agreed that eight predefined determinants sufficiently cover the research objectives. No other determinants were added.

3.3. Fuzzy TOPSIS

Practically, several techniques can be applied to prioritize the determinants according to the roles that they play in the intent to stay of employees. Multi-criteria decision-making (MCDM) techniques have become popular recently in assessing, evaluating, and ranking determinants across diverse sectors. It is considered a powerful tool in dealing with multiple objective problems [27]. The application of various MCDM methods has been successfully demonstrated to prioritize alternatives such as the use of TOPSIS in waste management [22] and risk management [27], decision making trial and evaluation laboratory in international development projects [13], and relationship management [59], analytic network processes in mega construction projects [60], and analytical hierarchy processes in energy conservation and emissions reduction [61]. The discussion of all these techniques is however beyond the paper’s scope.

Among various MCDM methods developed to tackle real-world problems, TOPSIS satisfactorily illustrates wide applicability in diverse application fields. Originally, to select the best alternative with a definite limit number of criteria Hwang and Yoon developed the TOPSIS method in 1981 [62]. TOPSIS is considered as a simple ranking method in both conception and application, which “attempts to choose alternatives that simultaneously have the shortest distance from the positive ideal solution and the farthest distance from the negative ideal solution” [62]. While the positive ideal solution minimizes the cost criteria and maximizes the benefit criteria, the negative ideal solution minimizes the benefit criteria and maximizes the cost criteria [27].

It is argued that original MCDM methods are limited with crisp values which are uncertain, ambiguous, and unable to capture the vagueness of the real-world decision problems. Consequently, fuzzy MCDM is favorable to reflect the uncertainty of a complex environment [13] and suitable for this study. Recently, TOPSIS has received much attention from scholars and professionals. Maghsoodi and Khalilzadeh [63] employed fuzzy TOPSIS to rank critical success factors of Iranian construction projects. Baykasoǧlu et al. [24] used fuzzy TOPSIS to solve the truck selection problem in a Turkey land transportation company. Memari et al. [64] selected sustainable suppliers based on nine criteria and 30 sub-criteria by using fuzzy TOPSIS. Malakouti et al. [65] applied fuzzy TOPSIS and evaluated the flexibility of components to improve housing quality. Zubayer et al. [66] utilized fuzzy TOPSIS to prioritize supply chain risk in the ceramic industry in Bangladesh. This wide application has highlighted that the advantages of fuzzy TOPSIS include: (1) simple calculation processes that can be simply shown into a spreadsheet, (2) scalar values that simultaneously consists of best and worst alternatives, and (3) logically representing uncertain perceptions of human [25,27,62].

4. Ranking Determinants Using Fuzzy TOPSIS

Results collected from the interview stage enabled the authors to form the survey questionnaire, which intended prioritizing the importance of each determinant according to two dimensions, namely, job satisfaction and organizational commitment.

Fuzzy TOPSIS was employed to analyze the collected data. It is worth noticing that in this research, the alternatives are eight employee retention determinants and the criteria are job satisfaction and organizational commitment. The following steps should be noted. This section is divided by subheadings. It should provide a concise and precise description of the experimental results, their interpretation, as well as the experimental conclusions that can be drawn.

4.1. Step One

Introducing the membership function of the alternatives and criteria. In this paper, the linguistic terms and their corresponding membership functions of the alternatives and criteria are illustrated in Table 1.

Table 1.

Linguistic terms and their corresponding membership functions of the alternatives and criteria.

4.2. Step Two

Assigning linguistic terms to the alternatives and criteria. Seventy-two respondents in different South Korean contractors agreed to participate in the questionnaire survey. Table 2 presents the information of these respondents.

Table 2.

Demographic information of the respondents.

The list of employee retention determinants and dimensions was provided to the respondents. They were asked to assign the linguistic terms to the given criteria and alternatives.

4.3. Step Three

Constructing the aggregated fuzzy weights for the criteria and alternatives. The collected assessments of linguistic terms of criteria and alternatives were then translated into membership functions presented in Table 1. The outputs were used to calculate the aggregated fuzzy weights for the criteria and alternatives. First, the aggregated fuzzy weights for the criteria is defined as follows:

where: is the weight of jth criterion

The fuzzy decision matrix of the criteria () is presented as follow:

Second, the aggregated fuzzy weights for the alternatives is defined as follow:

where: is the aggregated fuzzy rating of criteria within each alternative.

The fuzzy decision matrix of the alternatives () is presented as follow:

The aggregated fuzzy weights of criteria and ratings of alternatives are computed and presented in Table 3 and Table 4.

Table 3.

Aggregated fuzzy weight of criteria.

Table 4.

Aggregated fuzzy weight of alternatives.

4.4. Step Four

Calculating the normalized fuzzy decision matrix. The normalized fuzzy decision matrix for alternatives is calculated by the following formulation and illustrated in Table 5:

where:

Table 5.

The normalized fuzzy decision matrix for alternatives.

For example, the normalized decision matrix of alternatives employee income in criteria job satisfaction is computed as:

4.5. Step Five

Generating the weighted normalized matrix. The weighted normalized matrix was then identified as follow:

where:

For example, the weighted normalized matrix of alternatives employee income in criteria job satisfaction is computed as:

Table 6 illustrates the weighted normalized matrix.

Table 6.

The weighted normalized matrix.

4.6. Step Six

Determining the distance of each alternative from FPISs and FNISs. The fuzzy positive ideal solution (FPIS) and fuzzy negative ideal solution (FNIS) are generated as follow:

The distance of each alternative from FPISs and FNISs are then computed and presented in Table 7 as follows:

where: d(..) refers to the distance between two triangular fuzzy numbers and , calculated by the following formula:

Table 7.

Distance of each alternative from FPISs and FNISs.

Taking alternatives employee income in criteria job satisfaction as an example:

4.7. Step Seven

Determining the closeness coefficient and ranking the alternatives. The alternatives are prioritized based on the values of . The alternative that has the highest value is the most important option. The closeness coefficient of each alternative is defined and calculated (Table 8) as follows:

Table 8.

Closeness coefficient and ranking.

For example, the ranking of alternative employee income is calculated as:

The results of fuzzy TOPSIS analysis revealed that personal characteristics are the most critical factor that affects employee retention in South Korean construction firms. This was followed by personal development, promotion opportunities, and work-life balance, respectively. Meanwhile, company images and development, work environment, employee welfare, and employee income were the least affecting factors towards employee retention.

5. Discussion and Conclusions

It is noticeable that employee income ranked the lowest importance in comparison with the other determinants. As a developed country, South Korean workers are well-protected by the laws [20]. In 2021, the minimum hourly wage has been set at $7.23, increasing by 1.5% from 2020 [67]. This minimum wage is applied to any worker in any business sector. Thus, a construction worker typically earns more than $2,000 per month [67]. On a national level, it is estimated a family of four can expect to spend an average of $2,000 per month [68]. As to Maslow’s needs hierarchy theory [69], because this amount of money is sufficient for the basic needs (i.e., physiological needs), construction workers will value other aspects such as working conditions, social security insurance, and affiliation to an organization [43]. Meanwhile, previous studies, focused on developing context, witnessed a critical role that employee income plays in employee retention [15,34,35].

According to Maslow’s five basic needs [69], when an employee has fulfilled a self-development opportunity (i.e., social needs), they may value a working environment that provides a high possibility of growth. In particular, they will expect to be participated in the organization’s decision-making process, thus showing their social status. At the highest level of Maslow’s needs hierarchy, employees demand that their personality is fit with their job characteristics and working environment to achieve self-actualization [43]. Thus, it is understandable that personal characteristics became the most crucial factor that affects employee retention in the South Korean context. This finding is also supported by the statement of Ayodele et al. [5] that personal (employee) characteristics are the most frequently mentioned factor associated with the individual workforce that affects workforce turnover in the construction sector.

Through reviewing the literature and discussions with construction professionals, this study identifies eight significant determinants of employee retention in the context of the South Korean construction industry. The fuzzy TOPSIS method is successfully employed to assess and prioritize eight determinants of employee retention in regards to two dimensions, job satisfaction, and organizational commitment. The findings highlight that personal characteristics are the most critical determinants of employee retention in South Korean construction firms, followed by personal development, promotion opportunities, and work-life balance, company image and development, work environment, employee welfare, and employee income, respectively. Additionally, the proposed framework presented in Figure 1 is another finding of this study that proposes a comprehensive methodology in assessing determinants of employee retention. Finally, it results that fuzzy TOPSIS can be employed in human resources management multiple criteria decision-making problems with several advantages over other techniques of prioritization.

In terms of managerial implications, this paper contributes to human resources management by investigating the determinant of employee retention in South Korean construction firms. The analysis highlighted that South Korean construction firms should carefully examine employee characteristics before hiring and positioning important positions within their organizations to increase employee retention rates. Furthermore, they should provide their employees with sufficient training to satisfy employees’ demand for personal development. Specifically, South Korean construction firms are suggested to increase human capital investment through different employee training programs, such as safety (i.e., site supervisor safety training), technical training (i.e., Building Information Modelling), and soft skills (i.e., leadership, teamwork, and communication). Moreover, potential promotion opportunities should be also provided which plays a significant role in the achievement of sustainable employee retention in South Korean construction companies.

Although the research objectives were achieved, this research had the following limitations. First, this research only focused on the context of South Korean contractors. Thus, different business contexts, working environments, and cultural backgrounds may generate different findings. Second, while the list of determinants of employee retention was investigated from the careful literature review and validated by experienced experts, this research was unable to encompass all determinants pertaining to employee retention considering the uncertainties of the dynamic business environment. Consequently, future studies are encouraged to employ the methodology presented in this research to investigate the most relevant determinants of employee retention and assess the importance of these variables within different research contexts. Moreover, future studies should be implemented in the contexts of developing countries to compare the results of this research. The comparisons will provide comprehensive illustrations regarding the differences in human resources management practices between developed and developing countries.

Author Contributions

Authors have worked together on this manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Some or all data, models, or codes that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request. The quantitative data utilized to develop the tables and figures within the manuscript are available.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully appreciated and respect all valuable contributions from all participants in this research.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Kyndt, E.; Dochy, F.; Michielsen, M.; Moeyaert, B. Employee Retention: Organisational and Personal Perspectives. Vocat. Learn. 2009, 2, 195–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burke, R.J.; Ng, E. The changing nature of work and organizations: Implications for human resource management. Hum. Resour. Manag. Rev. 2006, 16, 86–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harhara, A.S.; Singh, S.K.; Hussain, M. Correlates of employee turnover intentions in oil and gas industry in the UAE. Int. J. Organ. Anal. 2015, 23, 493–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, N. Employee Turnover Intention Among Newcomers in Travel Industry. Tourism 2014, 16, 56–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayodele, O.A.; Chang-Richards, A.; González, V. Factors Affecting Workforce Turnover in the Construction Sector: A Systematic Review. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 2020, 146, 03119010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durdyev, S.; Ismail, S.; Kandymov, N. Structural Equation Model of the Factors Affecting Construction Labor Productivity. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 2018, 144, 04018007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, W.; Wong, J.K.W. Key activity areas of corporate social responsibility (CSR) in the construction industry: A study of China. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 113, 850–860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, S.; Hossain, M.M.; Haq, I. Implementation of lean construction in the construction industry in Bangladesh: Awareness, benefits and challenges. Int. J. Build. Pathol. Adapt. 2020, 39, 368–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.Y.; Nguyen, M.V. Mapping the Complexity of International Development Projects Using DEMATEL Technique. J. Manag. Eng. 2021, 37, 05020016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotera, Y.; Green, P.; Sheffield, D. Work-life balance of UK construction workers: Relationship with mental health. Constr. Manag. Econ. 2020, 38, 291–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manu, P.; Poghosyan, A.; Mshelia, I.M.; Iwo, S.T.; Mahamadu, A.-M.; Dziekonski, K. Design for occupational safety and health of workers in construction in developing countries: A study of architects in Nigeria. Int. J. Occup. Saf. Ergon. 2019, 25, 99–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Philips, P. Health Insurance and Worker Retention in the Construction Industry. J. Labor Res. 2010, 31, 20–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.Y.; Nguyen, M.V.; Dao, T.T.N. Prioritizing complexity using fuzzy DANP: Case study of international development projects. Eng. Constr. Arch. Manag. 2020, 28, 1114–1133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Currivan, D.B. The Causal Order of Job Satisfaction and Organizational Commitment in Models of Employee Turnover. Hum. Resour. Manag. Rev. 1999, 9, 495–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerdngern, N.; Thanitbenjasith, P. Influence of contemporary leadership on job satisfaction, organizational commitment, and turnover intention: A case study of the construction industry in Thailand. Int. J. Eng. Bus. Manag. 2017, 9, 1847979017723173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hee, C.H.S.; Ling, F.Y.Y. Strategies for reducing employee turnover and increasing retention rates of quantity surveyors. Constr. Manag. Econ. 2011, 29, 1059–1072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uğural, M.N.; Giritli, H.; Urbański, M. Determinants of the Turnover Intention of Construction Professionals: A Mediation Analysis. Sustainability 2020, 12, 954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, B.L. Employee Retention: A Review of Literature. IOSR J. Bus. Manag. 2013, 14, 8–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coetzee, M.; Stoltz, E. Employees’ satisfaction with retention factors: Exploring the role of career adaptability. J. Vocat. Behav. 2015, 89, 83–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S. Factors affecting employment retention among older workers in South Korea. Work. Older People 2016, 20, 14–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamamoto, H. The relationship between employee benefit management and employee retention. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2011, 22, 3550–3564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahpour, A. Prioritizing barriers to adopt circular economy in construction and demolition waste management. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2018, 134, 216–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.-T.; Chen, C.-B.; Ting, Y.-C. An ERP model for supplier selection in electronics industry. Expert Syst. Appl. 2011, 38, 1760–1765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baykasoğlu, A.; Kaplanoğlu, V.; Durmuşoğlu, Z.D.U.; Şahin, C. Integrating fuzzy DEMATEL and fuzzy hierarchical TOPSIS methods for truck selection. Expert Syst. Appl. 2013, 40, 899–907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salih, M.M.; Zaidan, B.B.; Zaidan, A.A.; Ahmed, M.A. Survey on fuzzy TOPSIS state-of-the-art between 2007 and 2017. Comput. Oper. Res. 2019, 104, 207–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.-C.; Chang, T.-H. Application of TOPSIS in evaluating initial training aircraft under a fuzzy environment. Expert Syst. Appl. 2007, 33, 870–880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dandage, R.; Mantha, S.S.; Rane, S.B. Ranking the risk categories in international projects using the TOPSIS method. Int. J. Manag. Proj. Bus. 2018, 11, 317–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zadeh, L.A. Fuzzy sets. Inf. Control 1965, 8, 338–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kossivi, B.; Xu, M.; Kalgora, B. Study on Determining Factors of Employee Retention. Open J. Soc. Sci. 2016, 04, 261–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilau, A.A.; Ajagbe, M.A.; Sholanke, A.B.; Sani, T.A. Impact of Employee Turnover in Small and Medium Construction Firms: A Literature Review. Int. J. Eng. Res. Technol. 2015, 4, 976–984. [Google Scholar]

- Skaalvik, E.M.; Skaalvik, S. Teacher job satisfaction and motivation to leave the teaching profession: Relations with school context, feeling of belonging, and emotional exhaustion. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2011, 27, 1029–1038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, W.G.; Leong, J.K.; Lee, Y.-K. Effect of service orientation on job satisfaction, organizational commitment, and intention of leaving in a casual dining chain restaurant. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2005, 24, 171–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ocen, E.; Francis, K.; Angundaru, G. The role of training in building employee commitment: The mediating effect of job satisfaction. Eur. J. Train. Dev. 2017, 41, 742–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Famakin, I.O.; Abisuga, A.O. Effect of path-goal leadership styles on the commitment of employees on construction projects. Int. J. Constr. Manag. 2016, 16, 67–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Dyk, J.; Coetzee, M. Retention factors in relation to organisational commitment in medical and information technology services. SA J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2012, 13, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Kim, S.; Kim, Y. Diversity climate on turnover intentions: A sequential mediating effect of personal diversity value and affective commitment. Pers. Rev. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- You, T.; Zi, H. The economic crisis and efficiency change: Evidence from the South Korean construction industry. Appl. Econ. 2007, 39, 1833–1842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benghida, D. Prospects and challenges in the South Korean construction industry: An economic overview. Int. J. Civ. Eng. Technol. 2017, 8, 1338–1346. [Google Scholar]

- Lingard, H. The impact of individual and job characteristics on ‘burnout’ among civil engineers in Australia and the implications for employee turnover. Constr. Manag. Econ. 2003, 21, 69–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, P.B.; Lee, G.; Jang, J. Employee empowerment and its contextual determinants and outcome for service workers: A cross-national study. Manag. Decis. 2017, 55, 1022–1041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kundu, S.C.; Lata, K. Effects of supportive work environment on employee retention: Mediating role of organizational engagement. Int. J. Organ. Anal. 2017, 25, 703–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jo, B.W.; Lee, Y.S.; Kim, J.H.; Khan, R.M.A. Trend Analysis of Construction Industrial Accidents in Korea from 2011 to 2015. Sustainability 2017, 9, 1297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Kim, J.-D.; Shin, Y.; Kim, G.-H. Cultural differences in motivation factors influencing the management of foreign laborers in the South Korean construction industry. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 2015, 33, 1534–1547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramlall, S. A Review of Employee Motivation Theories and their Implications for Employee Retention within Organizations. J. Am. Acad. Bus. 2004, 5, 52–63. [Google Scholar]

- Bakan, P.I. The Relationship between Employees’ Income Level and Employee Job Satisfaction: An Empirical Study. Int. J. Bus. Soc. Sci. 2013, 4, 18–25. [Google Scholar]

- Sang, K.J.C.; Ison, S.G.; Dainty, A.R.J. The job satisfaction of UK architects and relationships with work-life balance and turnover intentions. Eng. Constr. Arch. Manag. 2009, 16, 288–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foote, D.A.; Seipel, S.J.; Johnson, N.B.; Duffy, M.K. Employee commitment and organizational policies. Manag. Decis. 2005, 43, 203–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohyin, N.; Dainty, A.; Carrillo, P. HRM Strategies for Managing Employee Commitment: A Case Study of Small Construction Professional Services Firms. In Proceedings of the Engineering Project Organizations Conference, Rheden, The Netherlands, 1 January 2012; pp. 1–22. [Google Scholar]

- Parker, S.K.; Skitmore, M.; Skitmore, R. Project management turnover: Causes and effects on project performance. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 2005, 23, 205–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Oo, B.L.; Lim, B.T.H. Drivers, motivations, and barriers to the implementation of corporate social responsibility practices by construction enterprises: A review. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 210, 563–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martos-Pedrero, A.; Cortés-García, F.J.; Jiménez-Castillo, D. The Relationship between Social Responsibility and Business Performance: An Analysis of the Agri-Food Sector of Southeast Spain. Sustainability 2019, 11, 6390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrbach, O.; Mignonac, K. How organisational image affects employee attitudes. Hum. Resour. Manag. J. 2004, 14, 76–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riordan, C.M.; Gatewood, R.D.; Bill, J.B. Corporate Image: Employee Reactions and Implications for Managing Corporate Social Performance. J. Bus. Ethic 1997, 16, 401–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farooq, M.; Farooq, O.; Cheffi, W. How Do Employees Respond to the CSR Initiatives of their Organizations: Empirical Evidence from Developing Countries. Sustainability 2019, 11, 2646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borstorff, P.; Marker, M. Turnover Drivers and Retention Factors Affecting Hourly Workers: What is Important? Manag. Rev. Int. J. 2007, 2, 14–27. [Google Scholar]

- Coffey, M. Developing and maintaining employee commitment and involvement in lean construction. In Proceedings of the 8th International Workshop on Lean Construction; University of Sussex: Brighton, UK, 2000; Volume 44, pp. 17–19. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, T.W.; Mitchell, T.R.; Holtom, B.C.; McDaneil, L.S.; Hill, J.W. The unfolding model of voluntary turnover: A replication and extension. Acad. Manag. J. 1999, 42, 450–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chih, Y.-Y.; Kiazad, K.; Zhou, L.; Capezio, A.; Li, M.; Restubog, S.L.D. Investigating Employee Turnover in the Construction Industry: A Psychological Contract Perspective. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 2016, 142, 04016006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, F.; Granja, A.D.; Fregola, A.; Picchi, F.; Staudacher, A.P. Understanding Relative Importance of Barriers to Improving the Customer–Supplier Relationship within Construction Supply Chains Using DEMATEL Technique. J. Manag. Eng. 2019, 35, 04019002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Q.; Luo, L.; Hu, Y.; Chan, A.P.C. Measuring the complexity of mega construction projects in China—A fuzzy analytic network process analysis. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 2015, 33, 549–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Han, R.; Huang, Q.; Hao, J.; Lv, N.; Li, T.; Tang, B. Research on energy conservation and emissions reduction based on AHP-fuzzy synthetic evaluation model: A case study of tobacco enterprises. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 201, 88–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behzadian, M.; Otaghsara, S.K.; Yazdani, M.; Ignatius, J. A state-of the-art survey of TOPSIS applications. Expert Syst. Appl. 2012, 39, 13051–13069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maghsoodi, A.I.; Khalilzadeh, M. Identification and Evaluation of Construction Projects’ Critical Success Factors Employing Fuzzy-TOPSIS Approach. KSCE J. Civ. Eng. 2017, 22, 1593–1605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Memari, A.; Dargi, A.; Jokar, M.R.A.; Ahmad, R.; Rahim, A.R.A. Sustainable supplier selection: A multi-criteria intuitionistic fuzzy TOPSIS method. J. Manuf. Syst. 2019, 50, 9–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malakouti, M.; Faizi, M.; Hosseini, S.-B.; Norouzian-Maleki, S. Evaluation of flexibility components for improving housing quality using fuzzy TOPSIS method. J. Build. Eng. 2019, 22, 154–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Zubayer, A.; Ali, S.M.; Kabir, G. Analysis of supply chain risk in the ceramic industry using the TOPSIS method under a fuzzy environment. J. Model. Manag. 2019, 14, 792–815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- You, B.K. COVID-19 Crisis and the South Korean Construction Industry; South Korean Reseach Institute for Construction Policy: Seoul, Korea, 2020; Volume 3. [Google Scholar]

- Internations.org. Available online: https://www.internations.org/go/moving-to-south-korea/living (accessed on 28 April 2021).

- Oyedele, L.O. Sustaining architects’ and engineers’ motivation in design firms: An investigation of critical success factors. Eng. Constr. Arch. Manag. 2010, 17, 180–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).