1 Introduction

The quantization of matter fields in curved space-times is, as widely believed, a preliminary step towards a more complete theory of quantum gravity [

1]. In this framework the most important result is the thermal evaporation of black holes, whose temperature

T is related to surface gravity

κ by the relation

κ ∼

T ∼ (

GM )

−1, where

M is the mass of the black hole [

2]. Such a result has been obtained also for Rindler space-time [

3,

4,

5,

6,

7], corresponding to an accelerating observer, with the difference that the surface gravity is replaced by the acceleration

a of the observers (

κ →

a).

In a recent paper [

8], we have shown that the quantization of a complex scalar field in a curved manifold can be carried out in the framework of quantum algebras. In this new setting, one can study the thermal properties of quantum field theory in curved space-times. In particular, as shown in [

8], one can derive the functional relation between the entropy of black holes and the area of the event horizon. To be more specific, we have shown that a suitable deformation of the algebra

hk(1) of the annihilation and creation operators of the scalar fields, initially quantized in Minkowski space, induces the canonical quantization of the same field in a static gravitational background. The basic result arising from our approach is that the parameter of deformation

q is related to the physical parameters characterizing the gravitational field, hence the event horizon (for example, the acceleration in the case of Rindler space-time, or the Schwarzschild radius for the Schwarzschild geometry). As a consequence,

q is related to the surface gravity which is proportional to the inverse of the event horizon. This occurs in geometries with a single event horizon.

The aim of this paper is to present some applications of the formalism developed in [

8]. Namely, we shall emphasize the robustness against interaction with the environment of the entanglement of the quantum vacuum, due to the non-unitarity of the mapping between the vacua in the flat and curved frames of reference. Furthermore, we shall derive the entropy of black holes for the Schwarzschild, de Sitter, and Rindler geometries, characterized by having a unique event horizon.

The paper is organized as follows. In

Section 2 we recall the main features of the formalism proposed in [

8].

Section 3 is devoted to the analysis of the vacuum properties for the Minkwoskian and the generic observers. This analysis shows that the entangled structure of the vacuum is robust against interaction with the environment in the infinite volume limit. Besides, we calculate the black hole entropy for static and stationary geometries with a unique event horizon. Conclusions are drawn in

Section 4. Some further thermal features are commented in the

Appendix.

2 Deformed Algebra, Thermal Operators and Entropy

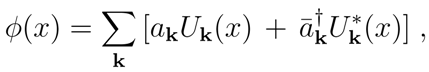

A complex massive scalar field

φ(

x), quantized in Minkowski space-time, can be expanded in terms of the complete set of modes {

Uk(

x)},

where

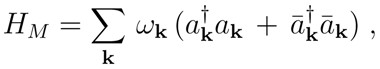

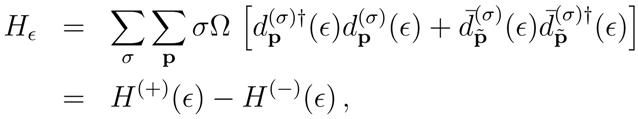

. The Hamiltonian operator is then given by

where

, and

are the annihilation and creation operators, respectively, for particles (antiparticles). They act on the Fock space

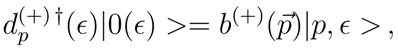

, whose Minkowski vacuum is defined by

. The operators entering the standard expansion (1) satisfy the usual canonical commutation relations (CCRs)

and so on. Algebraically speaking, the CCRs identify an infinite number of Weyl-Heisenberg algebras

hk(1), one for each momentum

k. Within these algebras we want to use the operation of co-product, which will enable us to deal with the partition of the Minkowski space-time into

two sectors (±). This is the preliminary step towards the introduction of the

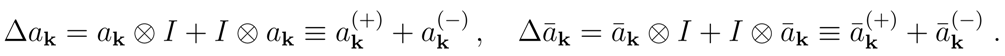

unique event horizon. The coproduct of the operators

ak and

is defined as

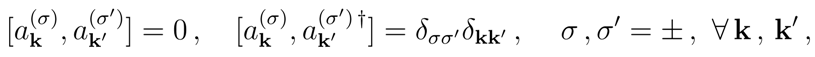

The operators

and

,

σ = ±, satisfy the CCRs

and similarly for

. They act on the full Hilbert space, i.e.

, where the ground state (vacuum) is defined as

. For brevity we shall indicate

with

, and

with

. The

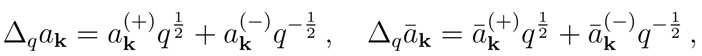

q-deformation of the coproduct (3) is

where

q =

q(

p). In what follows we shall consider the case of real

deformation parameter q. More generally,

q could depend on a momentum

p which may or may not coincide with

k. Furthermore,

q may depend also on other parameters:

q =

q(phys,

p) (where “phys” stands for the proper physical quantity [

8,

9]). We also require that that

, (here

,

, Ω > 0, and

, i.e.

q-deformation plays the same role on particles and antiparticles. Furthermore we shall make use of the standard relation

.

As explained in Ref. [

8], by using the deformed coproducts (5), one can construct new operators acting in an Hilbert space with a non-flat (non-Minkowskian) space-time as a support. To preserve the canonical algebra we use a complete orthonormal set of functions {

F(

k,

p)} to introduce the

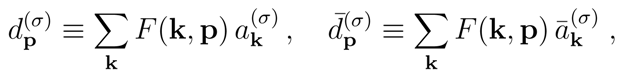

smeared operators

The

q-deformed coproduct of

d and

is given by [

8]

respectively, where the following short-hand notation has been used

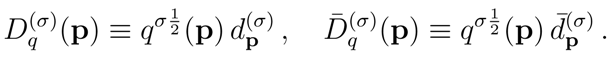

By using (8) we can simply take suitable linear combinations to obtain

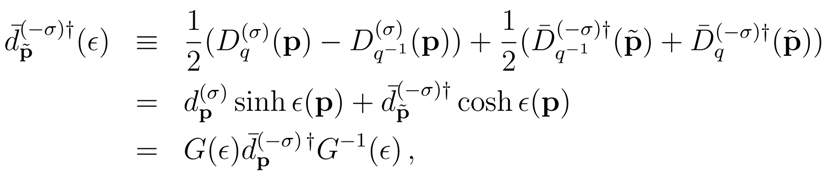

and

Here

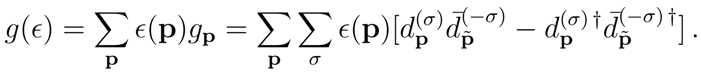

G(

ϵ) ≡ exp

g(

ϵ), where

G(

ϵ) is the generator of the Bogoliubov transformations (9) and is a unitary operator at finite volume:

.

Eqs. (9) and (10) relate vectors of

to vectors of another Hilbert space

labelled by

ϵ. The relation between these spaces is established by the generator

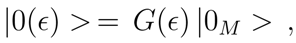

. For the vacuum state one has

where

is the vacuum state of the Hilbert space

annihilated by the new operators

. Note that even though

ϵ =

ϵ(phys,

p), the vacuum |0(

ϵ) > does not depend on

p, but only on the physical parameter, as follows from Eq. (11). Furthermore |0(

ϵ) > appears to be a

SU (1, 1) generalized coherent state [

10] of Cooper-like pairs (Bose-Einstein condensate). Of course similar considerations hold also for the state

by reversing

G(

ϵ) in Eq. (20). One can also see that the Hilbert spaces

,

, and

,

, become unitarily inequivalent in the infinite volume limit (

V-limit).

We now observe that the physical meaning of having two distinct momenta

k and

p for states in the Hilbert spaces

and

, respectively, is the occurrence of two

different reference frames: the

M-frame (Minkowski) and the new frame, which we shall call

Mϵ-frame. To explore the physics in the

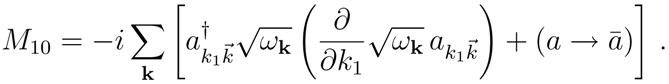

Mϵ–frame, one has to construct a diagonal operator which plays the role of the Hamiltonian. To this end we exploit the deformation of the algebra above introduced (see Eq. (5)). One starts by considering the (1, 0)–component of the generator of the Lorentz transformations defined as [

11]

By deforming the coproduct of

M10, one can write the Hamiltonian as [

8]

where the operators

and

are given in (9). Notice that

acts on states defined in the

new Hilbert space

and has as space–time the new frame

.

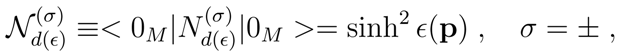

Turning now our attention to

, from Eq. (9) one gets that the number of modes of the type

in

is given by

where

. An analogous formula holds for the modes of type

. Eq. (15) makes clear the condensate structure of

. While one can work indifferently in one of the two sectors,

σ = + or

σ = −, we shall use

σ = +.

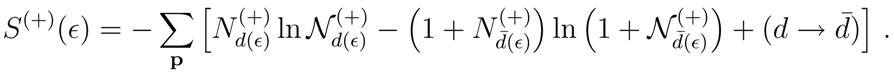

The entropy

of the Minkowskian vacuum as felt by the observer in the

Mϵ-frame, is given by [

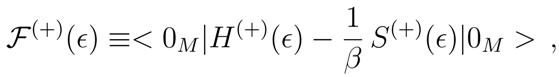

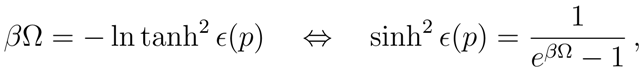

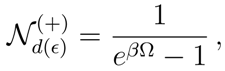

8].

The entropy operator (16) agrees with the definition of von Neumann entropy

, where

is the number of microscopic states. For the reader convenience, in the

Appendix we shall comment on further thermal properties. In particular we observe that, under extremal conditions, the number of particles

in the

Mϵ-frame computed in the Minkowski vacuum

gives a Bose-Einstein distribution. In the regime of thermal equilibrium, the induced partition of the

Mϵ space–time into two sectors,

σ = + and

σ = −, indicates the emergence of an event horizon, namely the emergence of a gravitational field. All that is encoded in the condensate structure of |

OM >. As can be seen from Eqs. (4) and (5) in the

Appendix, a constant temperature

T =

β−1 implies that the

Mϵ-frame is static and time-independent.

We remark that one of the advantages of the approach outlined above relies on the fact that the CCRs in the

Mϵ–frame have not to be imposed by hands, as usually done in QFT in curved space–time, but they are naturally recovered via

q-deformation [

8]. The physical parameter characterizing the background geometry is related to the

q-deformation parameter.

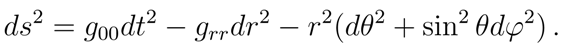

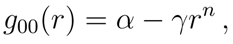

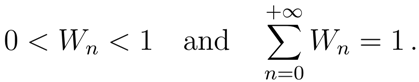

3 Applications to Schwarzschild, de Sitter and Rindler Space–Times

Our aim now is to apply the previous results to some specific geometries. First we derive the functional relation between the event horizon and the surface gravity in geometries with a unique event horizon. Let us consider a space-time with spherical symmetry whose line element is of the form

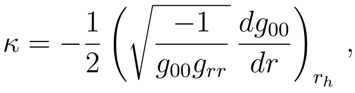

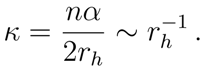

The surface gravity

κ is defined as [

12]

where

rh is the value for which

. Let us consider the usual case in which the components of the background geometry are such that

and that

has the form

where

n can be positive or negative, and

α and

γ are numerical factors. From

it follows

. With a simple calculation, one immediately derives that the surface gravity is

Consequences of this result will be studied in the following Subsections in the framework of Schwarzschild, de Sitter and Rindler geometries. Nonetheless, before moving to those applications, we want to present other important results of our treatment of the vacuum entanglement. Note that these features are common to all the above mentioned geometries.

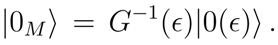

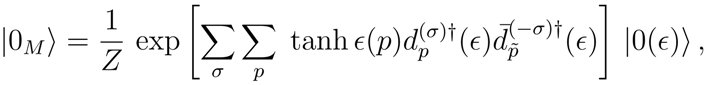

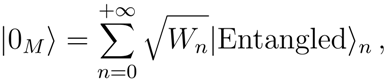

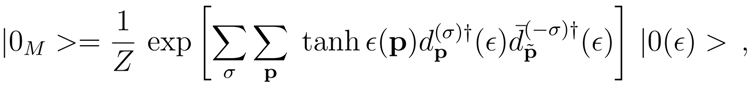

3.1 Vacuum Structure and Entanglement

As we have noted, the relation between the spaces

and

is established by the generator

, or by its inverse

. Thus the Minkowskian vacuum is expressed in terms of the generic

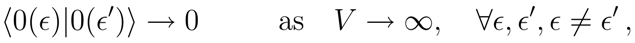

ϵ-vacuum as follows

This relation holds only at finite degrees of freedom, i.e. finite volume. Note that

G(

ϵ) is an element of

2 SU(1, 1) ×

SU(1, 1). Of course the same structure arises by writing

G−1(

ϵ) in terms of the

d(

ϵ)s, all one has to do is to replace

d →

d(

ϵ) in the Eq. (11). Thus by using the Gaussian decomposition, the Minkowski vacuum can be expressed as a

SU(1, 1) ×

SU(1, 1) generalized coherent state [

10] of Cooper-like pairs

where

Z = ∏

p cosh

2 ϵ(

p).

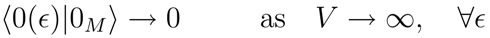

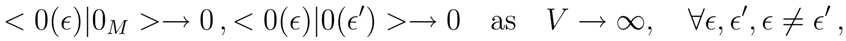

In the continuum limit in the space of momenta, i.e. in the infinite-volume limit, the number of degrees of freedom becomes uncountable infinite, hence we have

where

V is the volume of the whole (

D − 1)-dimensional space. This means that the Hilbert spaces

and

become unitarily inequivalent in the continuum limit. In this limit

ϵ, related to the deformation parameter by the relation

, labels the set

of the infinitely many unitarily inequivalent representations of the CCRs

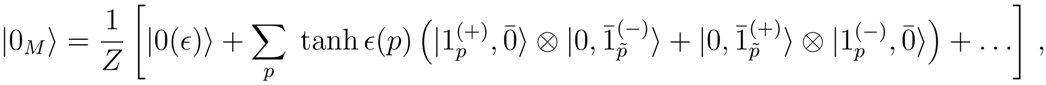

Let us now discuss the entanglement of the vacuum

in (21), that we rewrite in the following convenient form

where, we denote by

a state of

n particles and

m antiparticles in whichever sector (

σ). Note that for the generic

nth term, the state

, and similarly for antiparticles.

By introducing a well known notation, ↑ for a particle, and ↓ for an antiparticle, the two-particle state in (24) can be written as

which is an entangled state of particle and antiparticle living in the two causally disconnected regions (±). The generic

nth term in (24) shares exactly the same property as the two-particle state, but this time the ↑ describes a

set of

n particles, and ↓ a

set of

n anti-particles. The mechanism of the entanglement, dynamically induced by gravitational effects, takes place at all orders in the expansion, always by grouping particles and antiparticles into two sets. Thus the whole vacuum

is an infinite superposition of entangled states

3

where

with

The coefficients

of the expansion in Eq. (24) appear also in the discussion about the entropy of the black hole on which we shall concentrate in the following Sections. Details of calculations can be found in

Appendix A.

Of course, the probability of having entanglement of two sets of n particles and n antiparticles is Wn. At finite volume, being Wn a decreasing monotonic function of n, the entanglement is suppressed for large n. It appears then, that only a finite number of entangled terms in the expansion (26) is relevant. Nonetheless this is only true at finite volume (the quantum mechanical limit), while the interesting case occurs in the infinite volume limit, which one has to perform in a quantum field theoretical setting.

The entanglement is generated by

G(

ϵ), where the scalar field modes in one sector (

σ) are coupled to the modes in the other sector (−

σ) via the parameter

ϵ(

p). We remark that

ϵ(

p) actually describes the ”environment”, namely

ϵ(

p) takes into account the effects of the background gravitational field [

8]. Surprisingly in the present formulation the origin of the entanglement

is the environment, in contrast with the usual quantum mechanical view, which attributes to the environment the loss of the entanglement. In the present treatment such an origin for the entanglement makes it quite robust.

One further reason for the robustness is that this entanglement is realized in the limit to the infinite volume once and for all, since then there is no unitary evolution to disentangle the vacuum: at infinite volume one cannot ”unknot the knots”. Such a non-unitarity is only realized when all the terms in the series (26) are summed up, which indeed happens in the V → ∞ limit. In a future work we will comment with more details on the specific topic of the entanglement.

3.2 The Schwarzschild Geometry

We shall start with the Schwarzschild geometry. In polar coordinates, the line element of this space–time is (in natural units)

α = 1,

γ = 2

GM and

n = −1 in (19). The event horizon is given by

rh = 2

GM. According to our discussion (see

Section II and the

Appendix), the parameter

β is related to the surface gravity, so that we can impose the identification

β ~

rh, or

T ~ (

GM)

−1, which is the Bekenstein-Hawking temperature defined in the Introduction. The

q-deformation parameter is related to

β (see

Appendix) hence to the Schwarzschild radius

rS = 2

GM ≡

rh, which characterizes the geometrical structure underlying the

Mϵ-frame.

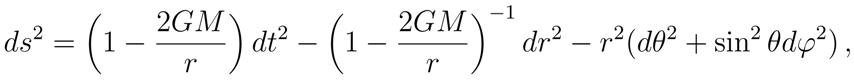

Let us now analyze the entropy operator. At the origin of the entropy (16) there are the vacuum fluctuations of quantum states, which have a thermal character for different observers related to the Minkowski observer through a diffeomorphism. In a curved space-time the momentum concept can be defined only locally. Keeping this in mind, it is convenient to make calculations in the continuum limit,

We shall use the relation

where

is a wave-packet

, similarly for

.

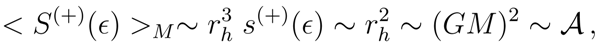

The expectation value on the vacuum

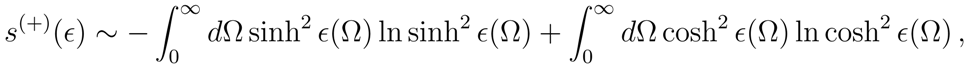

of the entropy operator defined in Eq. (16), gives the entropy density,

, hence

up to a factor of dimensions [lenght]

−2. The integration in Eq. (30), see also Eq. (4) in the

Appendix, yields [

14]

From Eq. (31) immediately follows that the entropy

of a spherical shell of radius

δ is

4, again up to a factor of dimensions [lenght]

−2,

namely the entropy is proportional to the horizon area

of the black holes [

2,

15].

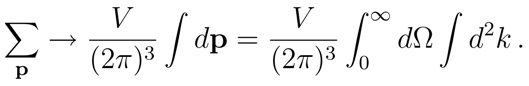

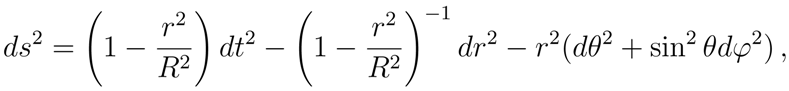

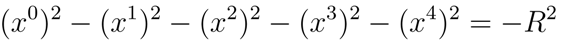

3.3 The de-Sitter Space–Time

Another interesting static geometry is the de Sitter one characterized by the line element [

16]

which clearly exhibits a horizon at

rh =

R. Here

R is the radius of the four-dimensional hyperboloid

embedded in a five-dimensional flat space-time. The comparison with (19) gives

α = 1,

γ = 1/

R2 and

n = 2. By using (18) it follows that

. For the above argument,

β ~

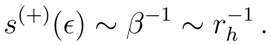

R. Thus the entropy

s(+) turns out to be

and the total entropy is given by (see (30)-(32))

and again the proportionality between entropy and area of the horizon is recovered.

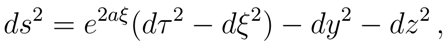

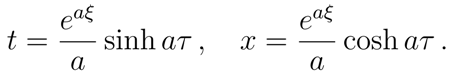

3.4 The Rindler Geometry

As further example, we shall now analyze a geometry in which again only one horizon is present but

. This is the case of Rindler space-time. It is described by the line element (see for example [

1])

which reduces to Minkowski space-time letting

This metric covers a portion of Minkowski space-time with

x > |

t|. The boundary planes are determine by

x ±

t = 0 [

17].

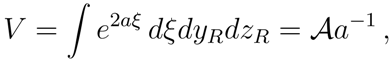

From Eq. (18) we get

κ =

a = 1/

β. The volume

V is given by

where 𝒜 = ∫

dyRdzR is the area of the surface of constant

x and it has been evaluated at

ξ = 0. Following the same calculations as for the Schwarzschild case, one infers that the entropy density turns out to be

so that the entropy is

which agrees with the result of Ref. [

18].

It is worth noting that in the case of Rindler space-time, results are formally equivalent to the Schwarzschild geometry since the surface gravity of the black holes is the gravitational acceleration at radius r measured at the infinity.

4 Conclusions

In this paper we exploited a model developed in a previous paper [

8], where it was shown how the

q-deformation of the canonical algebra of a complex scalar field quantized in the Minkowski space–time reproduces some of the typical structures of a quantized field in a space–time with a unique horizon. The deformation parameter

q depends on physical quantities related to the geometrical properties characterizing the background. The parameter

q(phys) → 1, as the physical parameters vanish, and the curved space-time reduces to a locally flat space-time.

We are then led to conclude that: i) quantum deformations can be described in terms of gravitational field effects; ii) the origin of the vacuum entanglement is the environment (contrarily to the common view which attributes to the environment the loss of the entanglement); iii) this entanglement is realized in the limit to the infinite volume once and for all, since then there is no unitary evolution to disentangle the vacuum. For the last two reasons the entanglement in this context is quite robust.

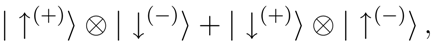

On the other hand, we have also derived the relationship between the entropy and the area of event horizons for Schwarzschild, de Sitter and Rindler space-times. The results obtained here, as well as in [

8], hold for geometries in which the horizon separates the space-time in two regions. It will be certainly interesting to extend our analysis to the case of geometries with more than one horizon, where the space-time is made of more than two regions. For instance, in the Kerr and Reissner-Nordstrom geometries one has two horizons,

r+ and

r−, to which correspond two distinct surfaces gravity,

k+ and

k−, as well as two distinct temperatures,

T+ and

T− (

k± ~

T±)

The key point in handling such geometries in our approach is to find a suitable deformation of the co-product. This implies a more careful analysis in deriving, from the deformed algebra, the Bogoliubov transformations (9) that are at the core of the thermal properties inferred in [

8]. This work is currently under investigation, as well as the extension to the fermionic fields.