The problem we considered is formulated as follows.

where

is the differential operator that describes the physical process, and

is the boundary operator applied to the boundary.

is the

d-dimensional physical domain with boundary

, and

represents a vector of unknown physical parameters. In addition,

is the forcing function,

is the boundary function, and

is the solution of the PDE. The aim of the inverse problem is to infer the solution function

and the unknown parameters

by integrating observational data with physical equations. The available data consists of the following three sets:

where

and

,

,

,

correspond to residual data, boundary-condition data and solution measurement in points

, respectively,

,

,

denote the number of residual, boundary and solution data points.

2.2. Hamiltonian Monte Carlo

Hamiltonian Monte Carlo (HMC) is an efficient Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) method specifically designed for sampling from complex high-dimensional probability distributions, and has been applied to inverse problems in Bayesian Neural Networks. By introducing auxiliary momentum variables and simulating Hamiltonian dynamics, HMC is capable of generating states that are widely separated while maintaining a high acceptance probability.

Suppose that the target posterior distribution of

conditioned on the observations

is given by

where

represents the potential energy. Then the Hamiltonian dynamics can be defined as follows:

where

is an auxiliary momentum vector, and

is the corresponding mass matrix, which is set to be the identity matrix

.

represents the kinetic energy. The Hamiltonian dynamics evolve the system according to

We use the Leapfrog integration to perform updating, and the Metropolis–Hastings acceptance test determines whether the proposed sample is accepted. The complete HMC procedure is summarized in Algorithm 1.

2.3. Ensemble Kalman Inversion

Ensemble Kalman Inversion (EKI) is a gradient-free inversion method based on an ensemble of samples, originally developed from the Ensemble Kalman Filter (EnKF). Unlike traditional Bayesian inverse problem solutions, EKI does not require explicit gradient computation. Instead, it iteratively updates an ensemble of samples under observation constraints, progressively approximating the high-probability region of the posterior distribution.

For an inverse problem with known observation data

and a forward model

, the goal is to estimate the unknown parameters

:

where

is the observation noise, and

R is the observation covariance matrix. According to Bayes’ theorem, the posterior can be expressed in the following form:

| Algorithm 1 Hamiltonian Monte Carlo (HMC) |

Require: initial states , time step size , leapfrog steps I, total running steps J for

do Sample from for do end for Sample from if then else end if end for Return:

|

Assuming the prior distribution of the parameters as

, the likelihood can be expressed as

To facilitate iterative inversion, we reformulate the Bayesian inverse problem as an artificial dynamical system:

where

represents an artificial parameter noise with covariance

Q and

denotes the observation error with covariance

R. In this formulation, the parameters are treated as state variables that evolve incrementally through the iterative process, while the observation equations remain unchanged. To efficiently approximate the posterior distribution, EKI employs the Kalman gain formula for Gaussian posterior distributions to iteratively update the sample set as in Ref. [

9]. Let

denote the initial ensemble of

J members drawn from the prior distribution. Then, at iteration

i, the

j-th ensemble member is updated as

where

and

represent the corresponding parameter and the observation noise. The sample covariances are defined as

At each iteration, the ensemble is updated according to the EKI scheme, producing a new set of parameter samples that progressively approximate the target posterior distribution.

2.4. Quantum Model

The quantum model

is formally defined as the expectation value of an observable

O with respect to a state evolved by the quantum circuit [

14]

as follows:

where

denotes the initial quantum state and

is the quantum circuit, which depends on the input

and the parameter

, and takes the following form:

The quantum circuit is composed of sequential layers

L, where each layer includes a data-encoding circuit block

and a trainable variational circuit block

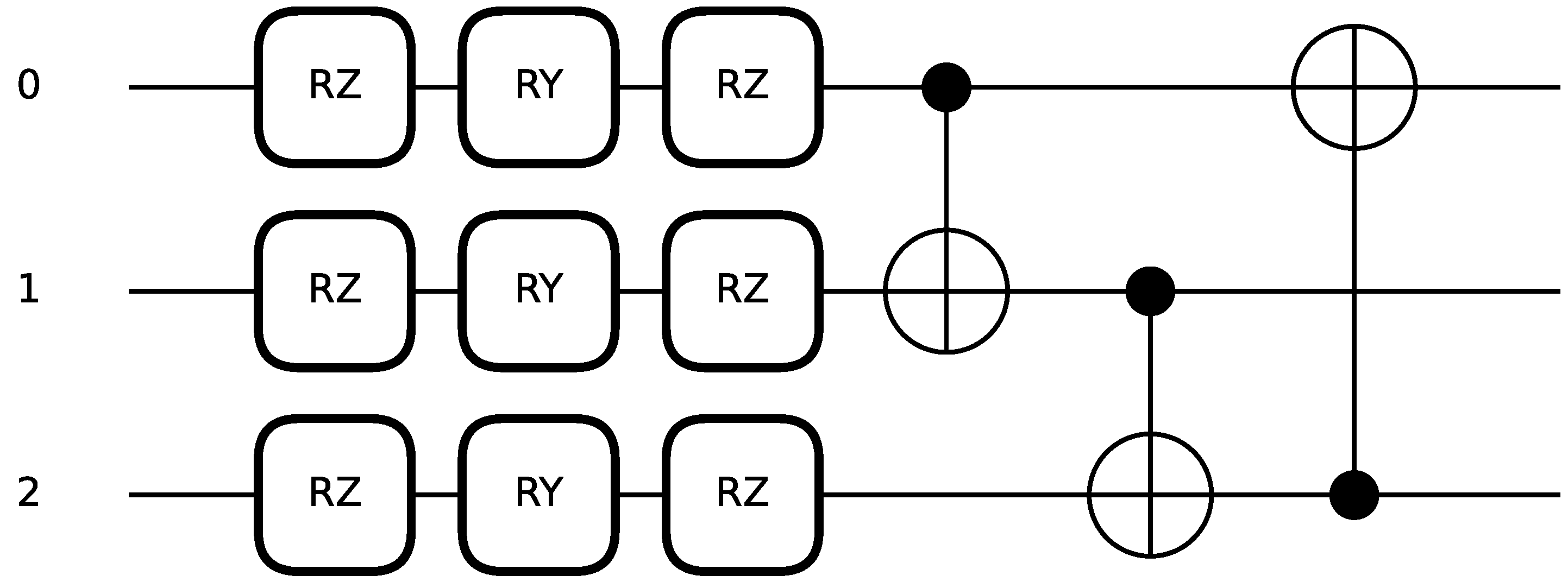

. An example quantum circuit with 3 qubits and 2 sequential layers is shown in

Figure 1.

The trainable and encoding layers of the quantum circuit are constructed using rotational gates [

23]. The matrix representation of these gates is given below:

Applying these rotation gates to the basis states

and

produces:

The data-encoding block

is mathematically defined as a tensor product of rotations

:

where

n is the number of qubits and

is the

i-th component of the input vector

. Applying the encoding block to the initial

n-qubit state

, we obtain the encoded state

as follows:

We use strongly entangling layers [

24] as the trainable circuit block and training blocks

depend on the parameters

that can be classically optimized. A strongly entangling layer with three qubits that contains 9 trainable variables takes the form as in

Figure 2.

Applying the strongly entangling layer to the encoded state produces the following result:

where

denotes a controlled-NOT gate acting on qubit

i (control) and

j (target). Applying the quantum circuit

to the initial state

produces the final state

:

This final state encodes both the classical input

and the variational parameters

, and serves as the basis for subsequent measurements to obtain the model output. Then the output of the quantum model is obtained by measuring a Hermitian observable

O, whose expectation value defines the model prediction [

25]:

where

O is a Hermitian operator representing the measured observable. We choose

O to be a tensor product of Pauli-Z operators

, which allows efficient readout of the model output from the quantum state. In practice,

is estimated by repeated measurements of the observable

O on multiple runs of the circuit.

2.5. Quantum-Encodable Bayesian PINNs Trained via Classical Ensemble Kalman Inversion

Gradient-based optimization of QNNs often encounters the barren plateau phenomenon, where the variance of gradients decays exponentially with the number of qubits or the depth of the circuit. As a result, randomly initialized circuits often produce gradients that are effectively zero, causing extremely slow or even stalled learning, particularly in deep or noisy quantum circuits. As a gradient-free update method, EKI naturally circumvents these difficulties by reducing the need for explicit gradient computation, thus avoiding the gradient concentration problems associated with barren plateaus, which enhances the training stability and accelerates the overall optimization of the QNN.

Motivated by these advantages, we incorporate QNNs into the EKI–BPINNs framework as surrogate models to solve PDE inverse problems. In this framework, the QNN surrogate approximates the forward solution of the governing PDE. Its parameters and the unknown PDE parameters are treated as part of the ensemble, which evolves during the inversion process. The EKI update infers the unknown physical parameters by assimilating noisy observational data while maintaining ensemble diversity. Furthermore, to fully exploit the input data for the QNN, we first perform a classical preprocessing step that constructs the network inputs as learnable linear combinations of the raw PDE data. Specifically, the QNN input is defined as , where represents the raw data, including residual data, boundary-condition data and solution measurement, and W and b are learnable parameters, which serve as a classical linear layer to map the raw data into a vector whose dimension matches the number of qubits used in the quantum circuit.

Algorithm 2 summarizes the complete training and inversion procedure. In this study, all computational stages are implemented and executed on classical hardware, where the QNN is simulated using the PennyLane v0.43 [

26] quantum circuit simulator. In the current framework, the inversion algorithm, ensemble perturbation, and residual-based updates are entirely classical, while the quantum role is confined to the QNN-based surrogate representation and its circuit evaluation.

The classical–quantum interaction is organized as an iterative parameter-update scheme. In each step, the BPINNs input is mapped to a quantum state using angle encoding, and the parameterized variational layers transform the state according to the current QNN weights. The circuit is evaluated repeatedly with several measurement shots to estimate expectation values, which serve as the circuit output. These outputs are passed to the classical EKI routine, where the residual between the observations and the quantum surrogate predictions is used to generate the next ensemble update.

Within B-PINNs, the parameters

are considered, with the forward operator

defining the model mapping. The quantity

represents the result of evaluating the forward model

in one step, which is defined as

| Algorithm 2 Quantum-Encodable Bayesian PINNs trained via Classical Ensemble Kalman Inversion (QEKI) |

Require: Observations , initial J ensemble states , observation covariance R, parameter covariance Q, training data points , iteration index . while not converge do for do Sample from Update each ensemble state Apply quantum circuit Evaluate the expectation value end for for do Sample from end for end while

Return:

|

Correspondingly, the observations defined in (

2) can be formulated as follows:

The physics-based residuals are evaluated via PennyLane’s interface, which maps the quantum circuit to a classically differentiable node. This setup enables the use of classical automatic differentiation while maintaining compatibility with native quantum gradient methods, such as the parameter-shift rule, for future execution on quantum processing units.

The choice of covariance matrices

Q and

R can significantly affect the performance of the algorithm. Previous studies have explored automatic estimation techniques for these matrices. In this work, following the strategy proposed in Ref. [

6], we set

R to be the covariance matrix as defined in (

5):

An appropriate choice of

Q is essential to preserve ensemble spread, so we set

Q to be

where

and

represent the standard deviations of the artificial process noise introduced to preserve ensemble spread for the QNN parameters

and the physical parameters

, respectively.

To determine when QEKI iterations should terminate, we employ a discrepancy-based stopping rule inspired by classical iterative regularization methods. The basic idea is to monitor how well the prediction of the current ensemble-averaged model matches the observed data, measured by a weighted residual norm as defined in Ref. [

6]. Let

denote the discrepancy at iteration

i, where

is the predicted observation produced by the

j-th ensemble member at iteration

i. Specifically, we define a sliding window of length

W and terminate the iteration once the discrepancy no longer exhibits sufficient improvement, i.e.,

Complexity Analysis. The computational cost of QEKI is lower than that of HMC, as it performs direct ensemble updates. The per-iteration computational complexity of QEKI is given by:

This complexity can be decomposed into the following components:

- (1)

—Cost of constructing the observation covariance matrix

- (2)

—Cost of constructing the observation covariance matrix

- (3)

—Cost of updating all ensemble members via the Kalman gain, .

In conclusion, the computational analysis indicates that the primary bottleneck of QEKI lies in the observation dimension , specifically due to the cost associated with the matrix inversion in the Kalman gain. Conversely, the algorithm exhibits linear scalability with respect to both the high-dimensional parameter space and the ensemble size J. This structural characteristic allows for rapid ensemble updates without prohibitive computational costs.

This completes the description of the proposed QEKI framework. The next section presents numerical experiments that demonstrate its performance on representative PDE inverse problems.