Time Series Prediction of Open Quantum System Dynamics by Transformer Neural Networks

Abstract

1. Introduction

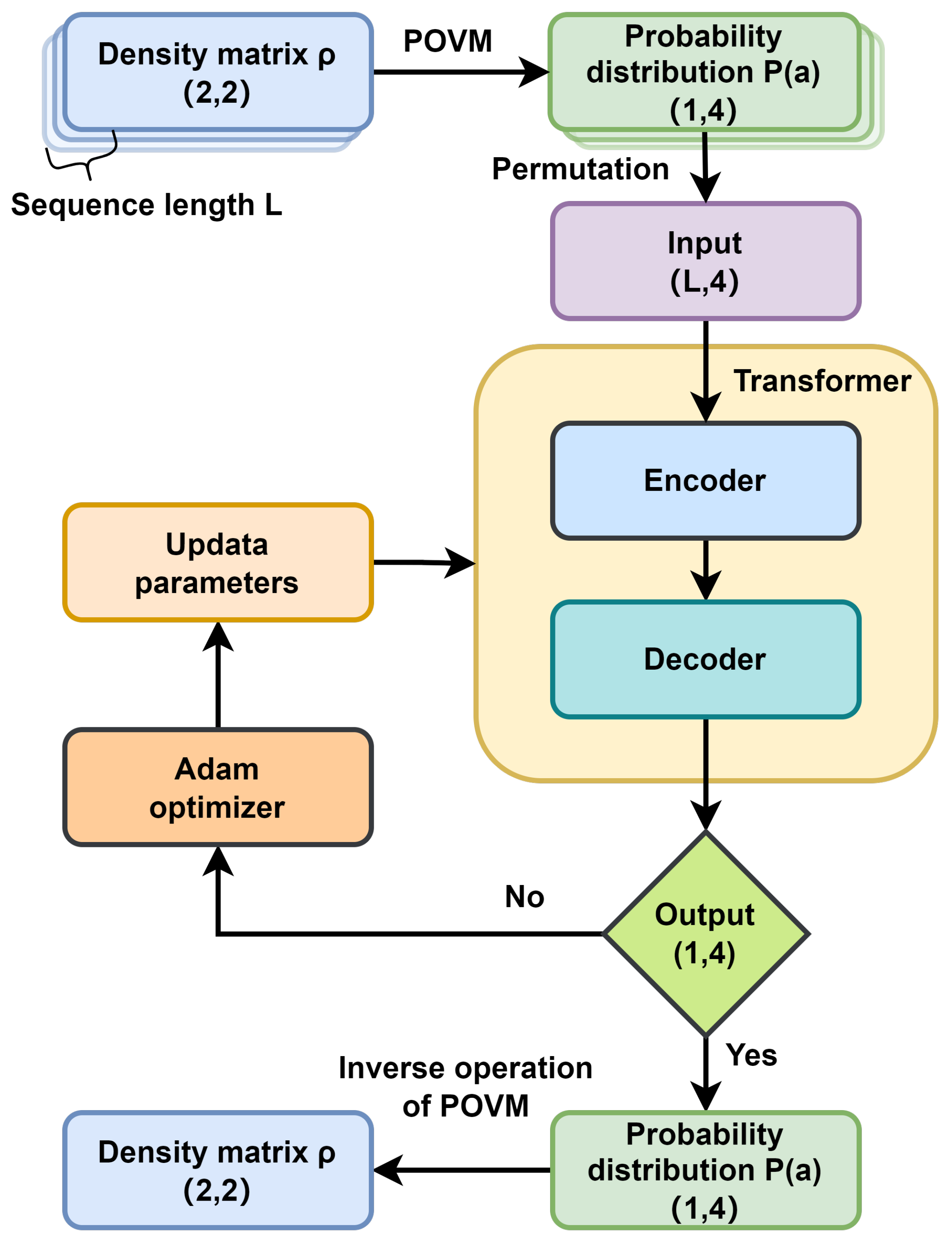

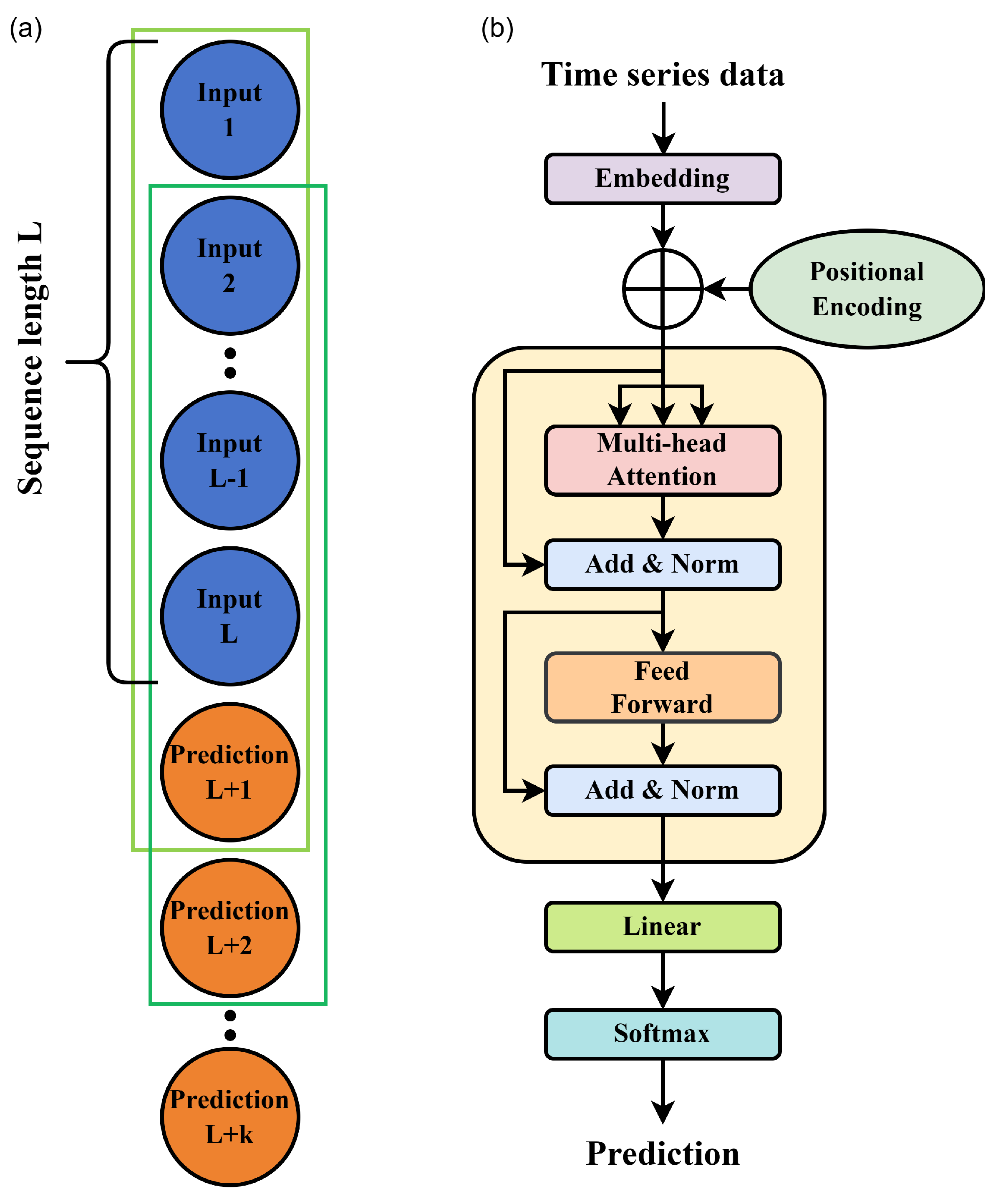

2. Methods

3. TSP and Transformer Neural Networks

4. Results and Discussions

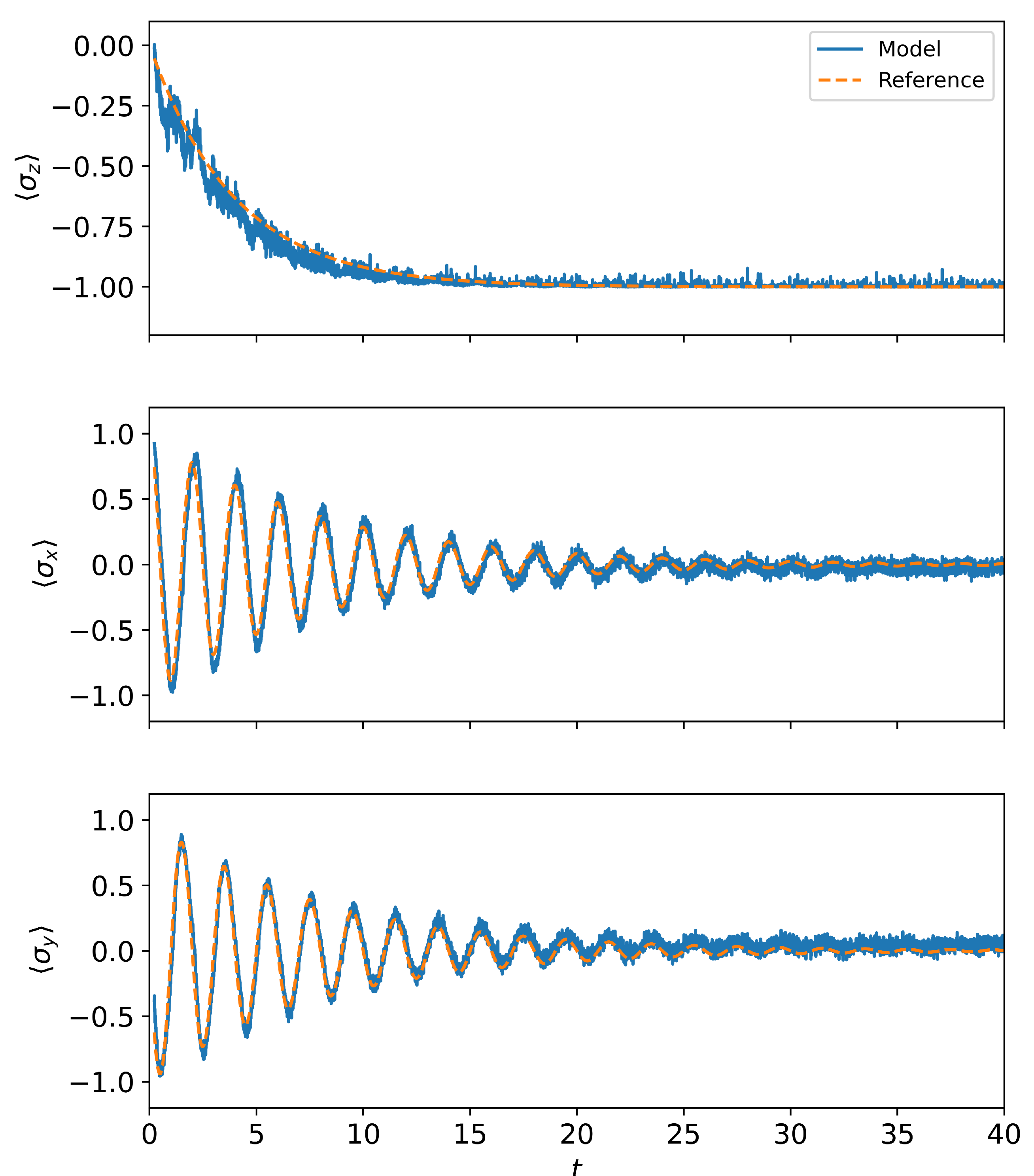

4.1. Short-Term TSP

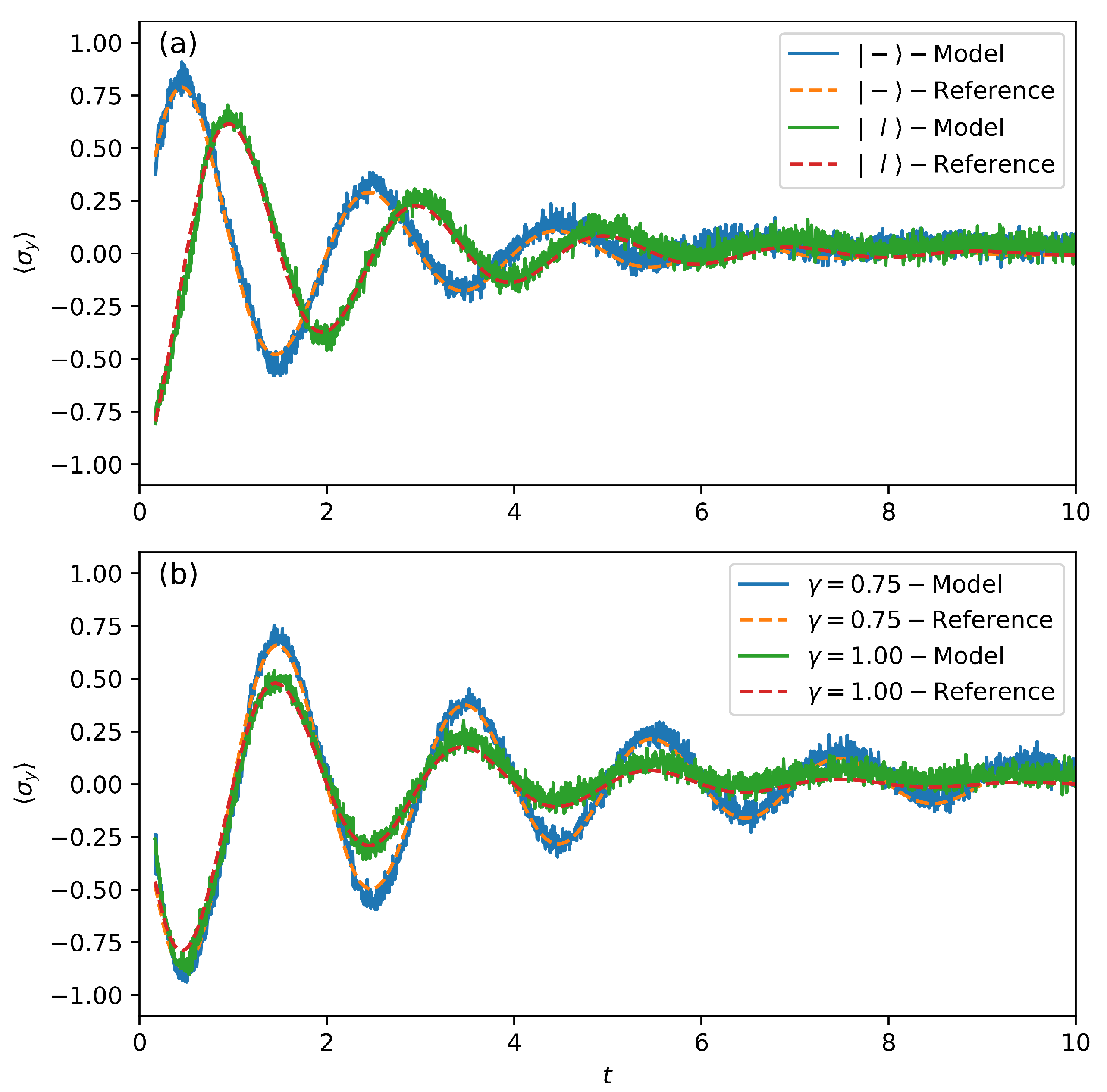

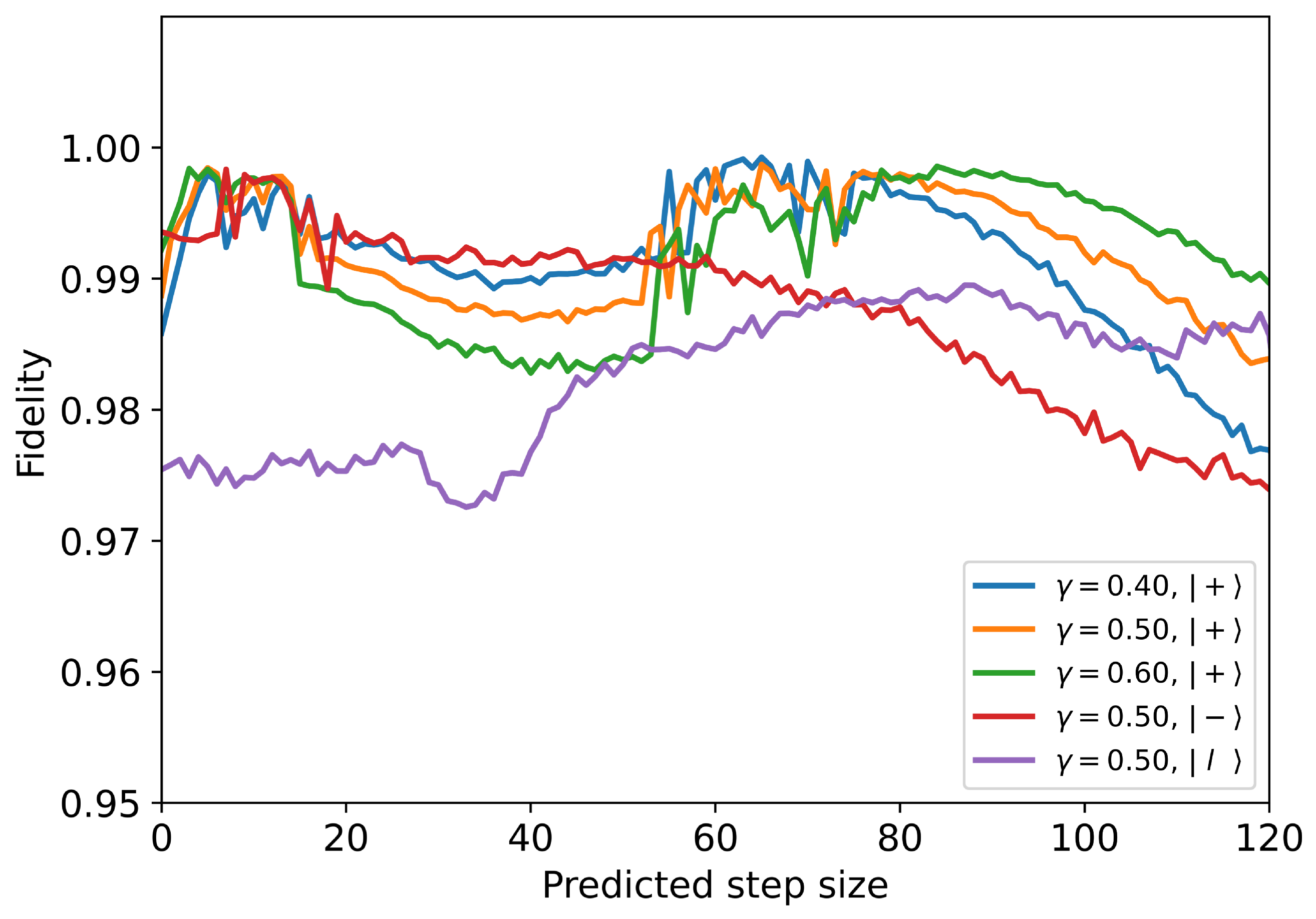

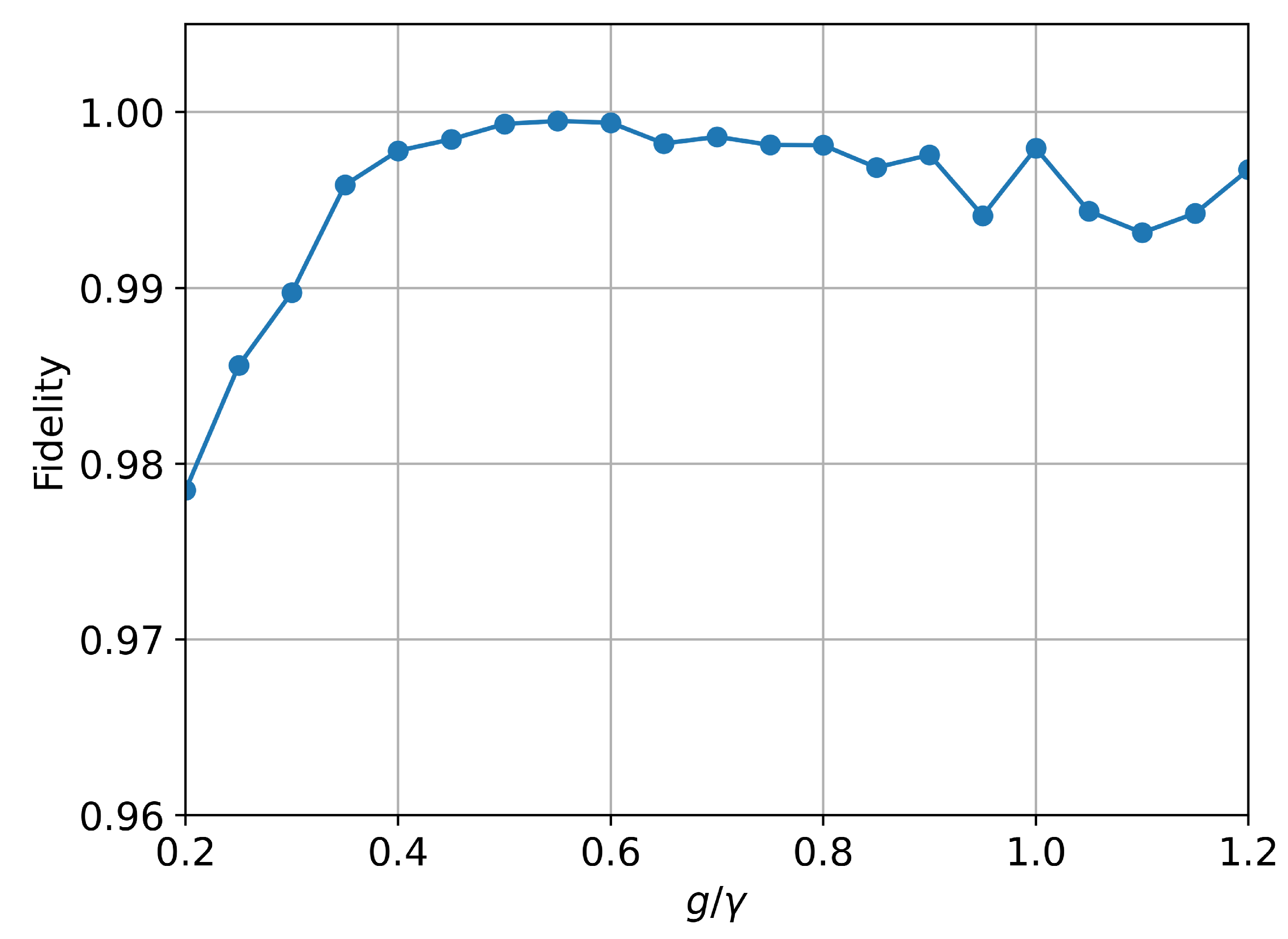

4.2. Long-Term TSP

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| TSP | time series prediction |

| POVM | positive operator-valued measure |

| PINNs | physics-informed neural networks |

| QuTiP | Quantum Toolbox in Python |

Appendix A. Training Process and Hyperparameters of TSP Models

| Parameters | Model 1 | Model 2 |

|---|---|---|

| 32 | 32 | |

| Feedforward network dimension | 128 | 128 |

| Number of attention heads | 8 | 8 |

| Positional encoding maximum length | 5000 | 5000 |

| Dropout rate | 0.1 | 0.1 |

| Learning Rate | ||

| Batch Size | 20 | 20 |

| Training Epochs | 500 | 500 |

| Optimizer | Adam | Adam |

| Weight initialization scheme | Default | Default |

References

- Yang, N.; Yu, T. Quantum Synchronization via Active–Passive Decomposition Configuration: An Open Quantum-System Study. Entropy 2025, 27, 432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cariolaro, G. Quantum Communications; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2015; Volume 2. [Google Scholar]

- Verstraete, F.; Wolf, M.M.; Ignacio Cirac, J. Quantum computation and quantum-state engineering driven by dissipation. Nat. Phys. 2009, 5, 633–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, C.H.; Chen, C.Y.; Chen, K.C.; Huang, T.W.; Hsu, M.C.; Cao, N.P.; Zeng, B.; Tan, S.G.; Chang, C.R. Quantum computation: Algorithms and Applications. Chin. J. Phys. 2021, 72, 248–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mui, K.; Couvertier, A.; Yu, T. Enhanced quantum state swapping via environmental memory. APL Quantum 2025, 2, 016126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nielsen, M.A.; Chuang, I.L. Quantum Computation and Quantum Information, 10th anniversary ed.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Tanimura, Y. Numerically “exact” approach to open quantum dynamics: The hierarchical equations of motion (HEOM). J. Chem. Phys. 2020, 153, 020901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kast, D.; Ankerhold, J. Persistence of Coherent Quantum Dynamics at Strong Dissipation. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2013, 110, 010402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kosionis, S.G.; Biswas, S.; Fouseki, C.; Stefanatos, D.; Paspalakis, E. Efficient population transfer in a quantum dot exciton under phonon-induced decoherence via shortcuts to adiabaticity. Phys. Rev. B 2025, 112, 075304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, P.; Yang, N.; Couvertier, A.; Ding, Q.; Chatterjee, R.; Yu, T. Chaos in Optomechanical Systems Coupled to a Non-Markovian Environment. Entropy 2024, 26, 742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.M.; Ren, F.H.; Luo, D.W.; Yan, Z.Y.; Wu, L.A. Quantum state transmission through a spin chain in finite-temperature heat baths. J. Phys. A Math. Theor. 2021, 54, 155303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diósi, L.; Strunz, W.T. The non-Markovian stochastic Schrödinger equation for open systems. Phys. Lett. A 1997, 235, 569–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martyn, J.M.; Najafi, K.; Luo, D. Variational Neural-Network Ansatz for Continuum Quantum Field Theory. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2023, 131, 081601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagy, A.; Savona, V. Variational quantum Monte Carlo method with a neural-network ansatz for open quantum systems. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2019, 122, 250501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodríguez, L.E.H.; Ullah, A.; Espinosa, K.J.R.; Dral, P.O.; Kananenka, A.A. A comparative study of different machine learning methods for dissipative quantum dynamics. Mach. Learn. Sci. Technol. 2022, 3, 045016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reh, M.; Schmitt, M.; Gärttner, M. Time-dependent variational principle for open quantum systems with artificial neural networks. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2021, 127, 230501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luo, D.; Chen, Z.; Carrasquilla, J.; Clark, B.K. Autoregressive neural network for simulating open quantum systems via a probabilistic formulation. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2022, 128, 090501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viteritti, L.L.; Rende, R.; Becca, F. Transformer Variational Wave Functions for Frustrated Quantum Spin Systems. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2023, 130, 236401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norambuena, A.; Mattheakis, M.; González, F.J.; Coto, R. Physics-Informed Neural Networks for Quantum Control. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2024, 132, 010801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.; Yu, Q.; Kuang, S. Robust Control of Uncertain Quantum Systems Based on Physics-Informed Neural Networks and Sampling Learning. IEEE Trans. Artif. Intell. 2025, 6, 1906–1917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, X.; Wang, D.; Chen, X.; Zhang, M. Physics-Informed Neural Network for Optical Fiber Parameter Estimation From the Nonlinear Schrödinger Equation. J. Light. Technol. 2022, 40, 7095–7105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ullah, A.; Huang, Y.; Yang, M.; Dral, P.O. Physics-informed neural networks and beyond: Enforcing physical constraints in quantum dissipative dynamics. Digit. Discov. 2024, 3, 2052–2060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Wu, Y. Learning quantum dissipation by the neural ordinary differential equation. Phys. Rev. A 2022, 106, 022201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ullah, A.; Dral, P.O. One-shot trajectory learning of open quantum systems dynamics. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2022, 13, 6037–6041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, Z.; Zhao, J.; Leung, H.; Ma, K.F.; Wang, W. A review of deep learning models for time series prediction. IEEE Sens. J. 2019, 21, 7833–7848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, H.; Zhang, S.; Peng, J.; Zhang, S.; Li, J.; Xiong, H.; Zhang, W. Informer: Beyond efficient transformer for long sequence time-series forecasting. AAAI Conf. Artif. Intell. 2021, 35, 11106–11115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masini, R.P.; Medeiros, M.C.; Mendes, E.F. Machine learning advances for time series forecasting. J. Econ. Surv. 2023, 37, 76–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naicker, K.; Sinayskiy, I.; Petruccione, F. Statistical and machine learning approaches for prediction of long-time excitation energy transfer dynamics. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2210.14160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrera Rodríguez, L.E.; Kananenka, A.A. Convolutional neural networks for long time dissipative quantum dynamics. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2021, 12, 2476–2483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, K.; Peng, J.; Gu, F.L.; Lan, Z. Simulation of open quantum dynamics with bootstrap-based long short-term memory recurrent neural network. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2021, 12, 10225–10234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, D.; Hu, Z.; Li, J.; Sun, X. Forecasting nonadiabatic dynamics using hybrid convolutional neural network/long short-term memory network. J. Chem. Phys. 2021, 155, 224104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaswani, A.; Shazeer, N.; Parmar, N.; Uszkoreit, J.; Jones, L.; Gomez, A.N.; Kaiser, Ł.; Polosukhin, I. Attention is all you need. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2017, 30, 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Herrera Rodríguez, L.E.; Kananenka, A.A. A short trajectory is all you need: A transformer-based model for long-time dissipative quantum dynamics. J. Chem. Phys. 2024, 161, 171101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gorini, V.; Kossakowski, A.; Sudarshan, E.C.G. Completely positive dynamical semigroups of N-level systems. J. Math. Phys. 1976, 17, 821–825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrasquilla, J.; Luo, D.; Pérez, F.; Milsted, A.; Clark, B.K.; Volkovs, M.; Aolita, L. Probabilistic simulation of quantum circuits using a deep-learning architecture. Phys. Rev. A 2021, 104, 032610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrasquilla, J.; Torlai, G.; Melko, R.G.; Aolita, L. Reconstructing quantum states with generative models. Nat. Mach. Intell. 2019, 1, 155–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paszke, A.; Gross, S.; Massa, F.; Lerer, A.; Bradbury, J.; Chanan, G.; Killeen, T.; Lin, Z.; Gimelshein, N.; Antiga, L.; et al. Pytorch: An imperative style, high-performance deep learning library. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2019, 32, 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Goodfellow, I.; Bengio, Y.; Courville, A. Deep Learning; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Kingma, D.P.; Ba, J. Adam: A method for stochastic optimization. arXiv 2014, arXiv:1412.6980. [Google Scholar]

- Azlan, A.; Yusof, Y.; Mohsin, M.F.M. Determining the impact of window length on time series forecasting using deep learning. Int. J. Adv. Comput. Res. 2019, 9, 260–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johansson, J.R.; Nation, P.D.; Nori, F. QuTiP: An open-source Python framework for the dynamics of open quantum systems. Comput. Phys. Commun. 2012, 183, 1760–1772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, K.; Peng, J.; Xu, C.; Gu, F.L.; Lan, Z. Automatic evolution of machine-learning-based quantum dynamics with uncertainty analysis. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2022, 18, 5837–5855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Wang, Z.-W.; Wu, L.-A.; Wang, Z.-M. Time Series Prediction of Open Quantum System Dynamics by Transformer Neural Networks. Entropy 2026, 28, 133. https://doi.org/10.3390/e28020133

Wang Z-W, Wu L-A, Wang Z-M. Time Series Prediction of Open Quantum System Dynamics by Transformer Neural Networks. Entropy. 2026; 28(2):133. https://doi.org/10.3390/e28020133

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Zhao-Wei, Lian-Ao Wu, and Zhao-Ming Wang. 2026. "Time Series Prediction of Open Quantum System Dynamics by Transformer Neural Networks" Entropy 28, no. 2: 133. https://doi.org/10.3390/e28020133

APA StyleWang, Z.-W., Wu, L.-A., & Wang, Z.-M. (2026). Time Series Prediction of Open Quantum System Dynamics by Transformer Neural Networks. Entropy, 28(2), 133. https://doi.org/10.3390/e28020133