Optimal Complexity of Parameterized Quantum Circuits

Abstract

1. Introduction

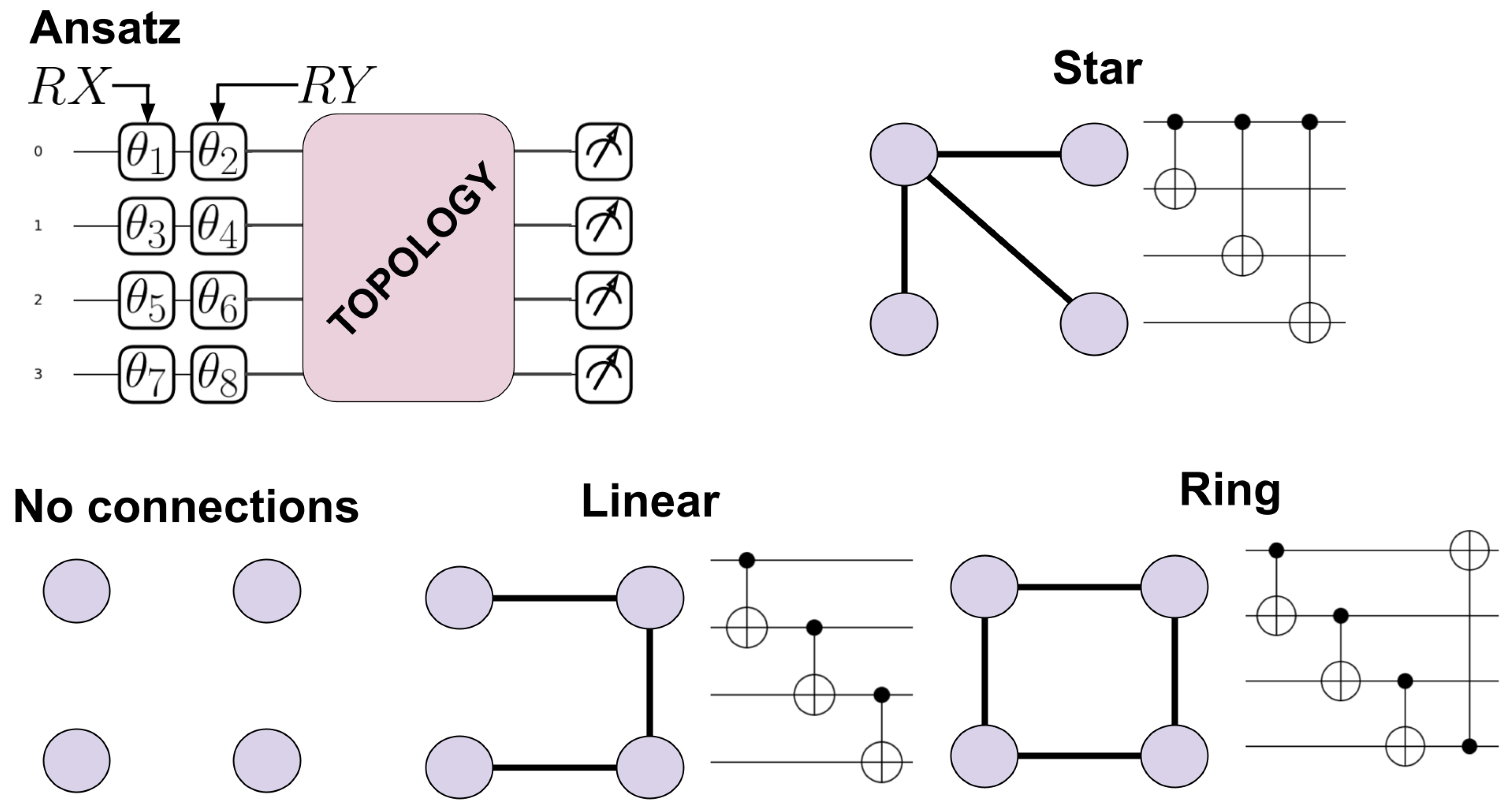

2. Quantum Circuits

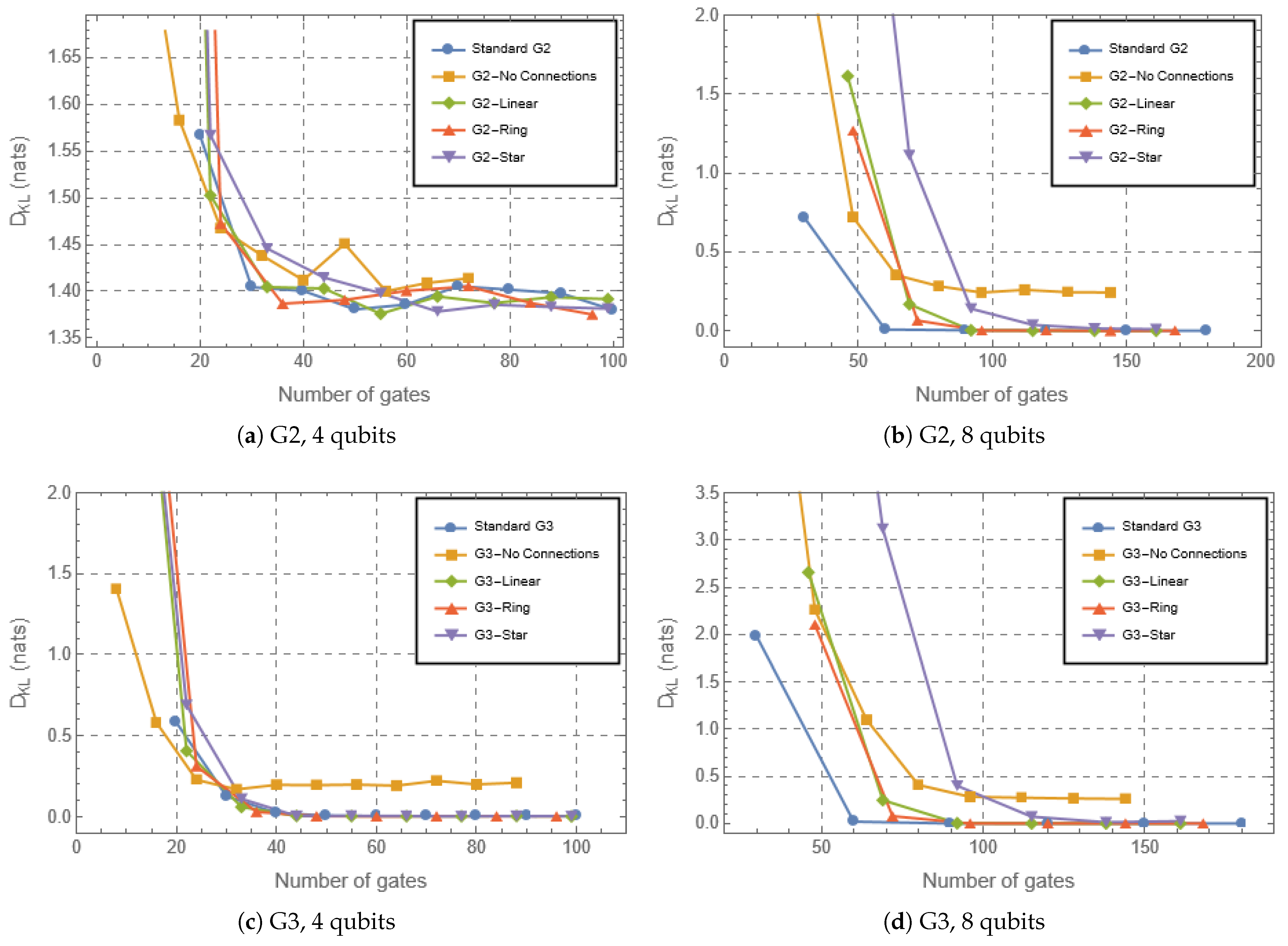

3. Complexity Quantifiers

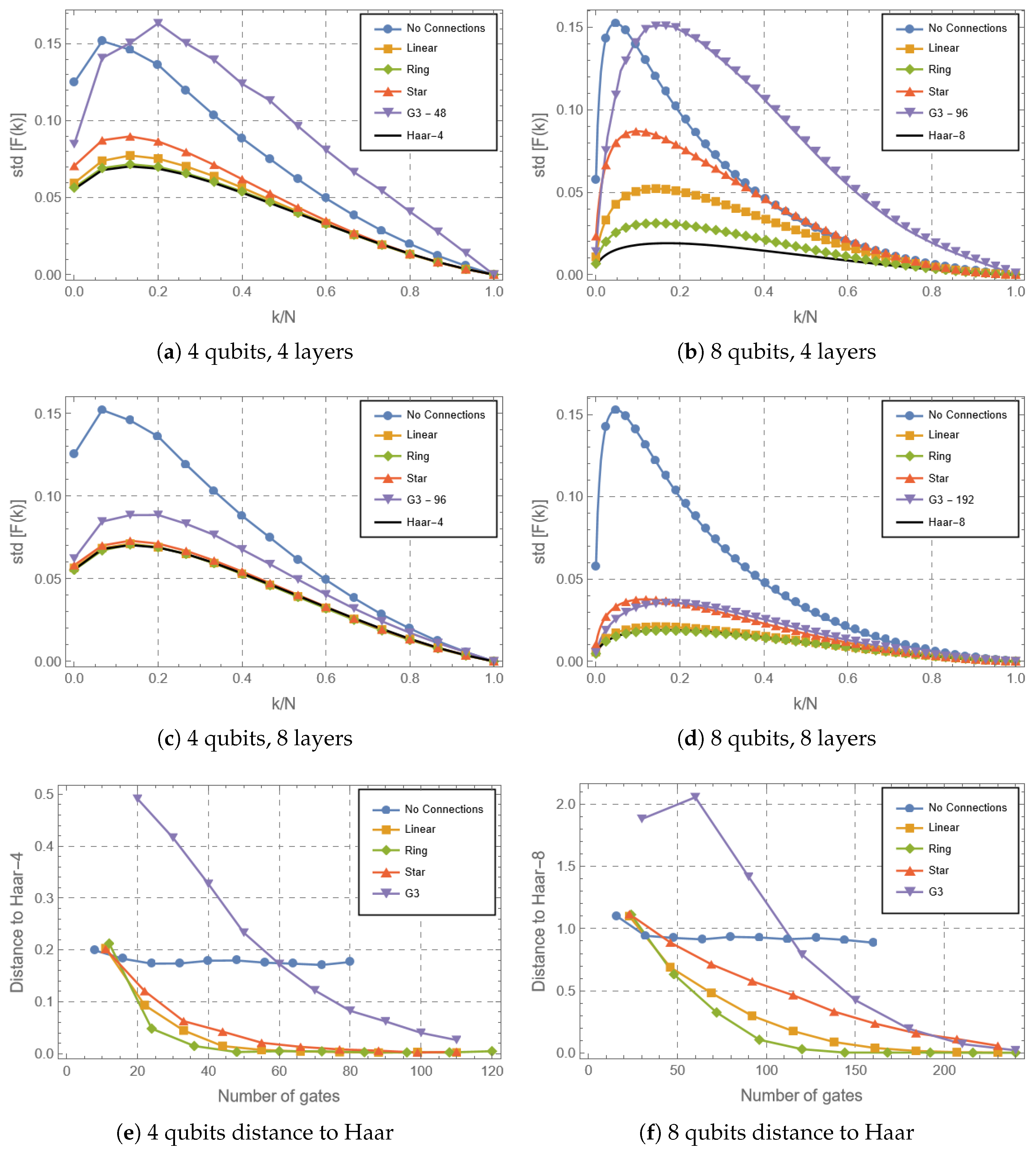

3.1. Expressibility

3.2. Majorization Criterion

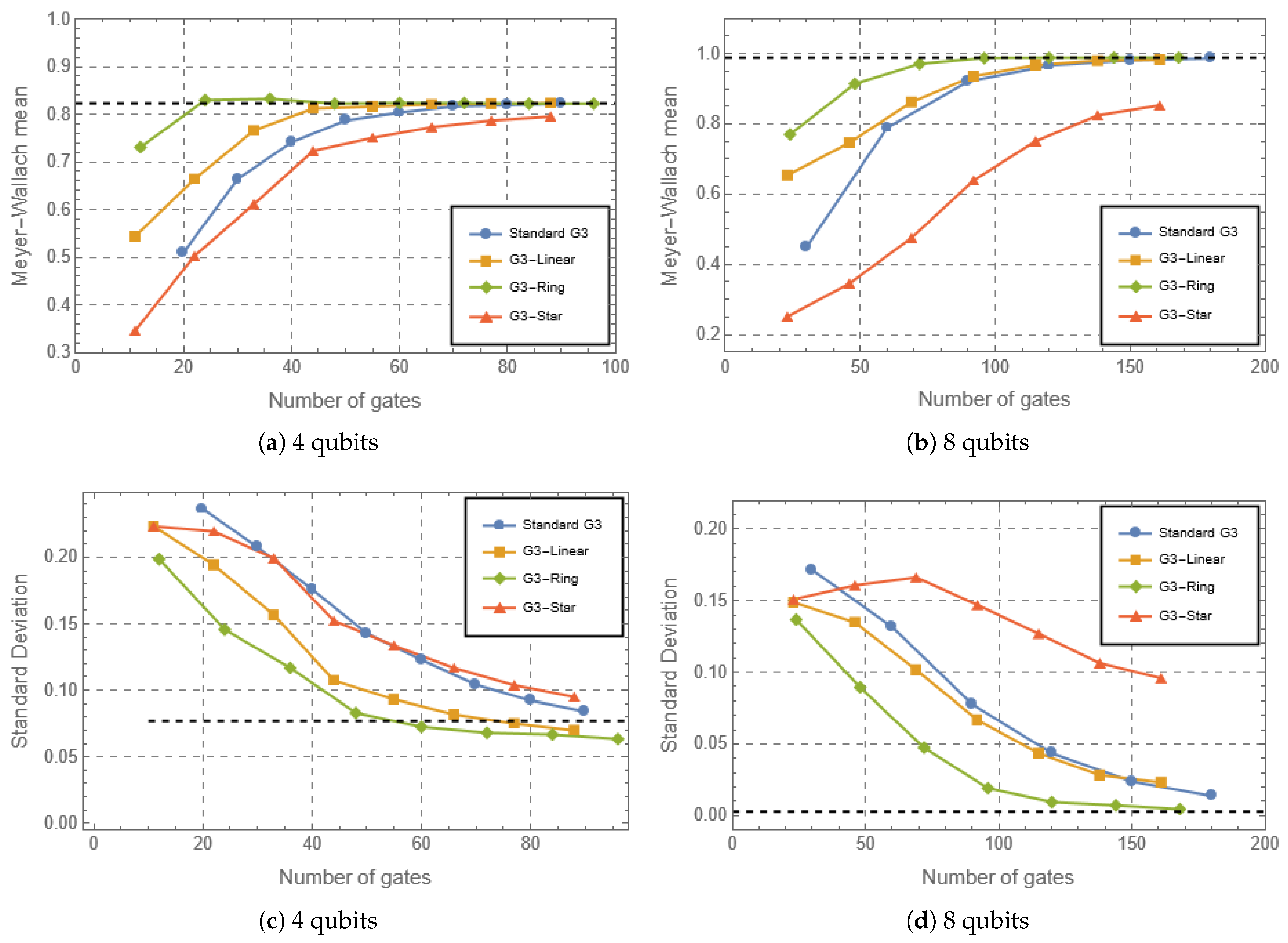

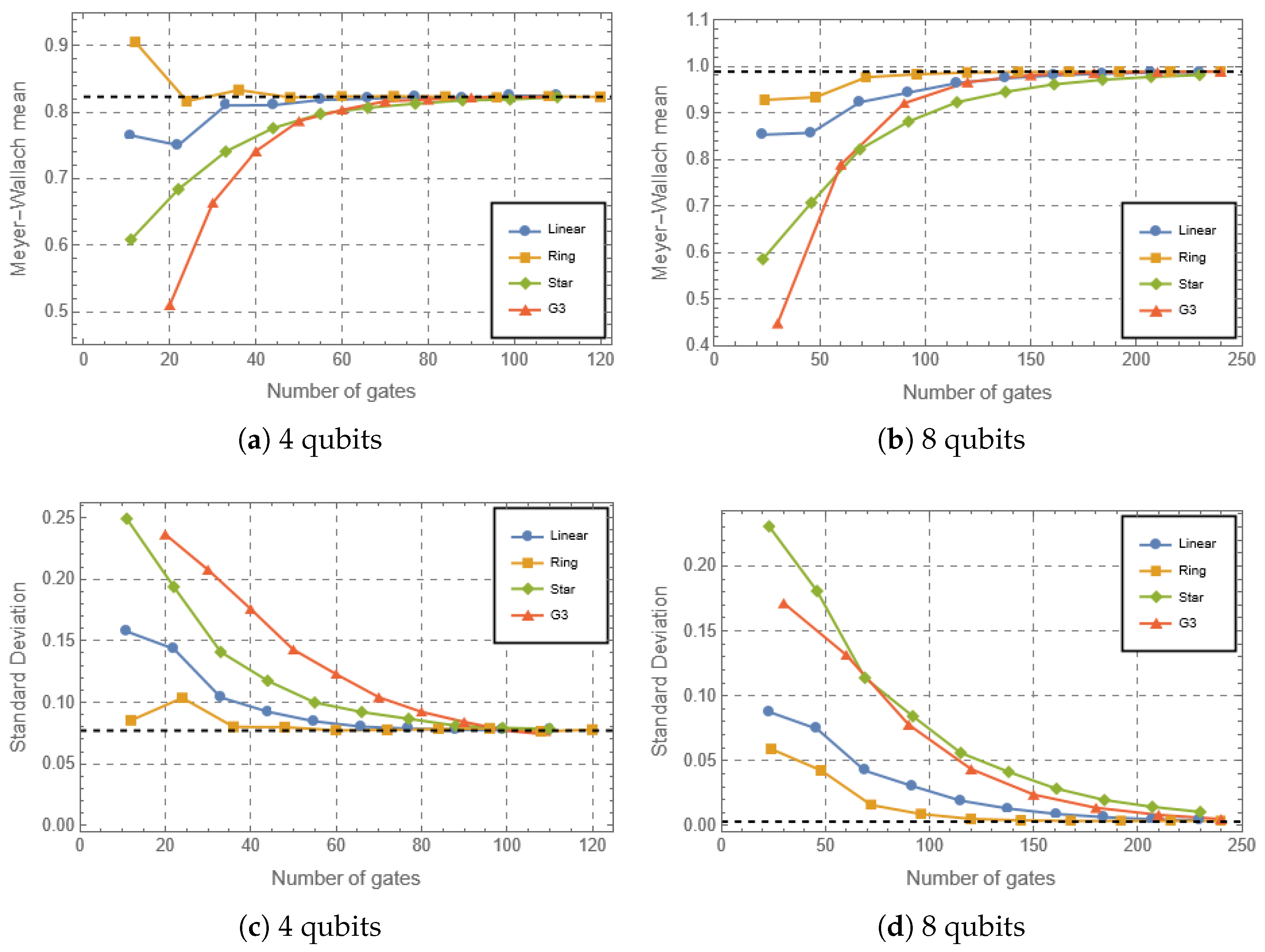

3.3. Average Entanglement

3.4. Relation to Dimensional Expressivity and Controllability

4. Results

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| NISQ | Near intermediate-scale quantum |

| PQC | Parameterized quantum circuit |

| VQA | Variational quantum algorithm |

Appendix A. G2 and G3 Circuits with Dense Entangling Structures

References

- Emerson, J.; Weinstein, Y.S.; Saraceno, M.; Lloyd, S.; Cory, D.G. Pseudo-Random Unitary Operators for Quantum Information Processing. Science 2003, 302, 2098–2100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Z.W.; Lloyd, S.; Zhu, E.; Zhu, H. Entanglement, quantum randomness, and complexity beyond scrambling. J. High Energy Phys. 2018, 2018, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisher, M.P.; Khemani, V.; Nahum, A.; Vijay, S. Random Quantum Circuits. Annu. Rev. Condens. Matter Phys. 2023, 14, 335–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ippoliti, M.; Ho, W.W. Solvable model of deep thermalization with distinct design times. Quantum 2022, 6, 886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peruzzo, A.; McClean, J.; Shadbolt, P.; Yung, M.H.; Zhou, X.Q.; Love, P.J.; Aspuru-Guzik, A.; O’brien, J.L. A variational eigenvalue solver on a photonic quantum processor. Nat. Commun. 2014, 5, 4213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McClean, J.R.; Romero, J.; Babbush, R.; Aspuru-Guzik, A. The theory of variational hybrid quantum-classical algorithms. New J. Phys. 2016, 18, 023023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kandala, A.; Mezzacapo, A.; Temme, K.; Takita, M.; Brink, M.; Chow, J.M.; Gambetta, J.M. Hardware-efficient variational quantum eigensolver for small molecules and quantum magnets. Nature 2017, 549, 242–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leone, L.; Oliviero, S.F.E.; Cincio, L.; Cerezo, M. On the practical usefulness of the Hardware Efficient Ansatz. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2211.01477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, A.C.C. Quantum circuit complexity. In Proceedings of the 1993 IEEE 34th Annual Foundations of Computer Science, Palo Alto, CA, USA, 3–5 November 1993; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 1993; pp. 352–361. [Google Scholar]

- Eisert, J. Entangling power and quantum circuit complexity. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2021, 127, 020501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bu, K.; Koh, D.E.; Li, L.; Luo, Q.; Zhang, Y. Statistical complexity of quantum circuits. Phys. Rev. A 2022, 105, 062431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haferkamp, J.; Faist, P.; Kothakonda, N.B.; Eisert, J.; Yunger Halpern, N. Linear growth of quantum circuit complexity. Nat. Phys. 2022, 18, 528–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vallejos, R.O.; de Melo, F.; Carlo, G.G. Principle of majorization: Application to random quantum circuits. Phys. Rev. A 2021, 104, 012602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sim, S.; Johnson, P.D.; Aspuru-Guzik, A. Expressibility and Entangling Capability of Parameterized Quantum Circuits for Hybrid Quantum-Classical Algorithms. Adv. Quantum Technol. 2019, 2, 1900070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weinstein, Y.S.; Brown, W.G.; Viola, L. Parameters of pseudorandom quantum circuits. Phys. Rev. A 2008, 78, 052332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, A.J.; Caves, C.M. Entangling power of the quantum baker’s map. J. Phys. A Math. Gen. 2003, 36, 9553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, A.J. Multipartite entanglement, quantum-error-correcting codes, and entangling power of quantum evolutions. Phys. Rev. A 2004, 69, 052330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iaconis, J. Quantum state complexity in computationally tractable quantum circuits. PRX Quantum 2021, 2, 010329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, A.J. Optimizing quantum process tomography with unitary 2-designs. J. Phys. A Math. Theor. 2008, 41, 055308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gross, D.; Audenaert, K.; Eisert, J. Evenly distributed unitaries: On the structure of unitary designs. J. Math. Phys. 2007, 48, 052104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dankert, C.; Cleve, R.; Emerson, J.; Livine, E. Exact and approximate unitary 2-designs and their application to fidelity estimation. Phys. Rev. A 2009, 80, 012304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerezo, M.; Arrasmith, A.; Babbush, R.; Benjamin, S.C.; Endo, S.; Fujii, K.; McClean, J.R.; Mitarai, K.; Yuan, X.; Cincio, L.; et al. Variational quantum algorithms. Nat. Rev. Phys. 2021, 3, 625–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Oz, Y. Entanglement diagnostics for efficient VQA optimization. J. Stat. Mech. Theory Exp. 2022, 2022, 073101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Oz, Y.; Rosa, D. Quantum chaos and circuit parameter optimization. J. Stat. Mech. Theory Exp. 2023, 2023, 023104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Liu, J.; Alexeev, Y.; Jiang, L. Estimating the randomness of quantum circuit ensembles up to 50 qubits. npj Quantum Inf. 2022, 8, 137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, L.; Zhai, J.; Zhang, Z.; Allcock, J.; Zhang, S.; Zheng, Y.C. Suppressing ZZ crosstalk of Quantum computers through pulse and scheduling co-optimization. In Proceedings of the 27th ACM International Conference on Architectural Support for Programming Languages and Operating Systems, Lausanne, Switzerland, 28 February–4 March 2022; ACM: New York, NY, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton, K.E.; Dumitrescu, E.F.; Pooser, R.C. Generative model benchmarks for superconducting qubits. Phys. Rev. A 2019, 99, 062323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, J.; Wang, H.; Liang, Z.; Shi, Y.; Han, S.; Qian, X. TopGen: Topology-Aware Bottom-Up Generator for Variational Quantum Circuits. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2210.08190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilário Correr, G.; Medina, I.; Azado, P.C.; Drinko, A.; Soares-Pinto, D.O. Characterizing randomness in parameterized quantum circuits through expressibility and average entanglement. Quantum Sci. Technol. 2024, 10, 015008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitaev, A.Y. Quantum computations: Algorithms and error correction. Russ. Math. Surv. 1997, 52, 1191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dawson, C.M.; Nielsen, M.A. The solovay-kitaev algorithm. arXiv 2005, arXiv:quant-ph/0505030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aaronson, S.; Gottesman, D. Improved simulation of stabilizer circuits. Phys. Rev. A—Atomic Mol. Opt. Phys. 2004, 70, 052328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gottesman, D. The Heisenberg representation of quantum computers. arXiv 1998, arXiv:quant-ph/9807006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domingo, L.; Carlo, G.; Borondo, F. Optimal quantum reservoir computing for the noisy intermediate-scale quantum era. Phys. Rev. E 2022, 106, L043301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tacla, A.B.; O’Neill, N.M.; Carlo, G.G.; de Melo, F.; Vallejos, R.O. Majorization-based benchmark of the complexity of quantum processors. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2304.04894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mezzadri, F. How to generate random matrices from the classical compact groups. Not. Am. Math. Soc. 2007, 54, 592–604. [Google Scholar]

- Zyczkowski, K.; Sommers, H.J. Induced measures in the space of mixed quantum states. J. Phys. A Math. Gen. 2001, 34, 7111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, D.A.; Yoshida, B. Chaos and complexity by design. J. High Energy Phys. 2017, 2017, 121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kullback, S.; Leibler, R.A. On information and sufficiency. Ann. Math. Stat. 1951, 22, 79–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilde, M.M. Quantum Information Theory, 2nd ed.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Życzkowski, K.; Sommers, H.J. Average fidelity between random quantum states. Phys. Rev. A 2005, 71, 032313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marshall, A.W.; Olkin, I.; Arnold, B.C. Inequalities: Theory of Majorization and Its Applications; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1979; Volume 143. [Google Scholar]

- Domingo, L.; Carlo, G.; Borondo, F. Taking advantage of noise in quantum reservoir computing. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 8790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, D.A.; Wallach, N.R. Global entanglement in multiparticle systems. J. Math. Phys. 2002, 43, 4273–4278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brennen, G.K. An Observable Measure of Entanglement for Pure States of Multi-Qubit Systems. Quantum Inf. Comput. 2003, 3, 619–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, N.A.; Wei, T.C.; Kwiat, P.G. Mixed-state sensitivity of several quantum-information benchmarks. Phys. Rev. A 2004, 70, 052309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Oliveira, T.R.; Rigolin, G.; de Oliveira, M.C. Genuine multipartite entanglement in quantum phase transitions. Phys. Rev. A 2006, 73, 010305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rigolin, G.; de Oliveira, T.R.; de Oliveira, M.C. Operational classification and quantification of multipartite entangled states. Phys. Rev. A 2006, 74, 022314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Funcke, L.; Hartung, T.; Jansen, K.; Kühn, S.; Stornati, P. Dimensional expressivity analysis of parametric quantum circuits. Quantum 2021, 5, 422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- d’Alessandro, D. Introduction to Quantum Control and Dynamics; Chapman and Hall/CRC: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Altafini, C. Controllability of quantum mechanical systems by root space decomposition of su(N). J. Math. Phys. 2002, 43, 2051–2062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schirmer, S.G.; Fu, H.; Solomon, A.I. Complete controllability of quantum systems. Phys. Rev. A 2001, 63, 063410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schatzki, L.; Larocca, M.; Nguyen, Q.T.; Sauvage, F.; Cerezo, M. Theoretical guarantees for permutation-equivariant quantum neural networks. npj Quantum Inf. 2024, 10, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holmes, Z.; Sharma, K.; Cerezo, M.; Coles, P.J. Connecting ansatz expressibility to gradient magnitudes and barren plateaus. PRX Quantum 2022, 3, 010313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McClean, J.R.; Boixo, S.; Smelyanskiy, V.N.; Babbush, R.; Neven, H. Barren plateaus in quantum neural network training landscapes. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 4812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayden, P.; Leung, D.W.; Winter, A. Aspects of generic entanglement. Commun. Math. Phys. 2006, 265, 95–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, W.G. Random Quantum Dynamics: From Random Quantum Circuits to Quantum Chaos. Ph.D. Thesis, Dartmouth College, Hanover, NH, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Brandao, F.G.; Harrow, A.W.; Horodecki, M. Local random quantum circuits are approximate polynomial-designs. Commun. Math. Phys. 2016, 346, 397–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wold, K.; Ribeiro, P.; Denisov, S. Universal spectra of noisy parameterized quantum circuits. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2405.11625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, S.; Yang, Z.; Hamma, A.; Chamon, C. Single T gate in a Clifford circuit drives transition to universal entanglement spectrum statistics. SciPost Phys. 2020, 9, 087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viscardi, M.; Dalmonte, M.; Hamma, A.; Tirrito, E. Interplay of entanglement structures and stabilizer entropy in spin models. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2503.08620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capecci, C.; Santra, G.C.; Bottarelli, A.; Tirrito, E.; Hauke, P. Role of Nonstabilizerness in Quantum Optimization. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2505.17185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turkeshi, X.; Tirrito, E.; Sierant, P. Magic spreading in random quantum circuits. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 2575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Topology | Number of CNOTs | Total Number of Gates |

|---|---|---|

| No connections | 0 | |

| Linear | ||

| Ring | ||

| Star |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Correr, G.I.; Azado, P.C.; Soares-Pinto, D.O.; Carlo, G.G. Optimal Complexity of Parameterized Quantum Circuits. Entropy 2026, 28, 73. https://doi.org/10.3390/e28010073

Correr GI, Azado PC, Soares-Pinto DO, Carlo GG. Optimal Complexity of Parameterized Quantum Circuits. Entropy. 2026; 28(1):73. https://doi.org/10.3390/e28010073

Chicago/Turabian StyleCorrer, Guilherme I., Pedro C. Azado, Diogo O. Soares-Pinto, and Gabriel G. Carlo. 2026. "Optimal Complexity of Parameterized Quantum Circuits" Entropy 28, no. 1: 73. https://doi.org/10.3390/e28010073

APA StyleCorrer, G. I., Azado, P. C., Soares-Pinto, D. O., & Carlo, G. G. (2026). Optimal Complexity of Parameterized Quantum Circuits. Entropy, 28(1), 73. https://doi.org/10.3390/e28010073