The KPZ Equation of Kinetic Interface Roughening: A Variational Perspective

Abstract

1. Introduction

- Modeling nonlinearities in ecological systems. The KPZ equation’s inclusion of nonlinear growth terms is particularly useful for modeling ecological processes where interactions between individuals or between species and their environments lead to complex, emergent movement patterns. For example, the propagation of invasive species, herd dynamics, or predator–prey interactions often exhibit such nonlinearities, and KPZ can capture these effects efficiently. A foundational exploration of movement patterns, emphasizing the need for nonlinear models like the KPZ to understand large-scale spatial patterns, can be found in [6].

- Spatial pattern formation in ecosystems. KPZ-like models can explain spatial clustering and aggregation, phenomena common in ecosystems due to habitat fragmentation or social behaviors in species. In this sense, the KPZ equation aligns well with empirical observations in movement ecology, where spatially heterogeneous environments cause uneven dispersal patterns. Book [7] elaborates on spatial pattern formation and how stochastic models, including those similar to KPZ, apply to understanding the distribution and aggregation of organisms.

- Capturing anomalous diffusion in animal movement. Traditional diffusion models often fail to capture the complexity of animal movement, which frequently exhibits subdiffusive or superdiffusive behavior due to factors like resource hotspots or behavioral adaptations. The KPZ equation, with its growth and roughening terms, provides a more flexible framework for modeling these deviations from classical diffusion. The article [8] reviews the inadequacy of simple diffusion models and how alternative stochastic approaches like KPZ are better suited to describe animal search behaviors that diverge from Brownian assumptions.

- Modeling stochastic processes in animal movement. The KPZ equation is an excellent tool for capturing random yet structured movement patterns, such as those seen in animal migrations or dispersal behaviors. Unlike simple random walks, the KPZ framework can describe anisotropic movement, a key aspect of ecological processes where environmental and physiological conditions lead to non-uniform patterns. The article [9] discusses the role of stochastic models, like KPZ, in modeling animal movement patterns beyond simple Brownian motion.

- Interfacing with statistical mechanics for predictive ecology. KPZ’s roots in statistical mechanics make it a natural fit for ecological models that require predictions based on system dynamics under uncertainty. By using KPZ, researchers can leverage known statistical properties to predict critical transitions, tipping points, or responses to environmental changes. The article [10] discusses the interface between movement ecology and statistical mechanics, highlighting how frameworks like KPZ facilitate a predictive approach to ecological modeling.

- In sum, the KPZ equation offers a robust framework for addressing the complex, nonlinear, and stochastic characteristics of movement patterns in ecology. Its applicability extends beyond traditional diffusion models, making it valuable for studying the spatial and temporal heterogeneity observed in animal populations. By leveraging the KPZ equation, ecologists can create models that more accurately reflect real-world movement dynamics, supporting better predictive and management tools in ecological research [11,12,13,14]. The KPZ universality class is characterized by definite values of either the roughness exponent α or the dynamical exponent z, and by the relation . If L denotes the substrate’s length along any dimension, then the global widthscales as . Here h is the local height (flat substrates) or radius (curved substrates), and denote spatial average and the ensemble one. Moreover, the correlation length on the interface scales as . For finite L, the scaling regime ends at saturation, when . As , it is a dynamical critical phenomenon. Putting it all together, it turns out that in the scaling regime , where is called the growth exponent.

2. The Variational Formulation

2.1. Model A—Like Variational Formulation

2.2. Discrete Version

2.3. Memory of Process

2.4. On the Existence of a Stationary State for Process

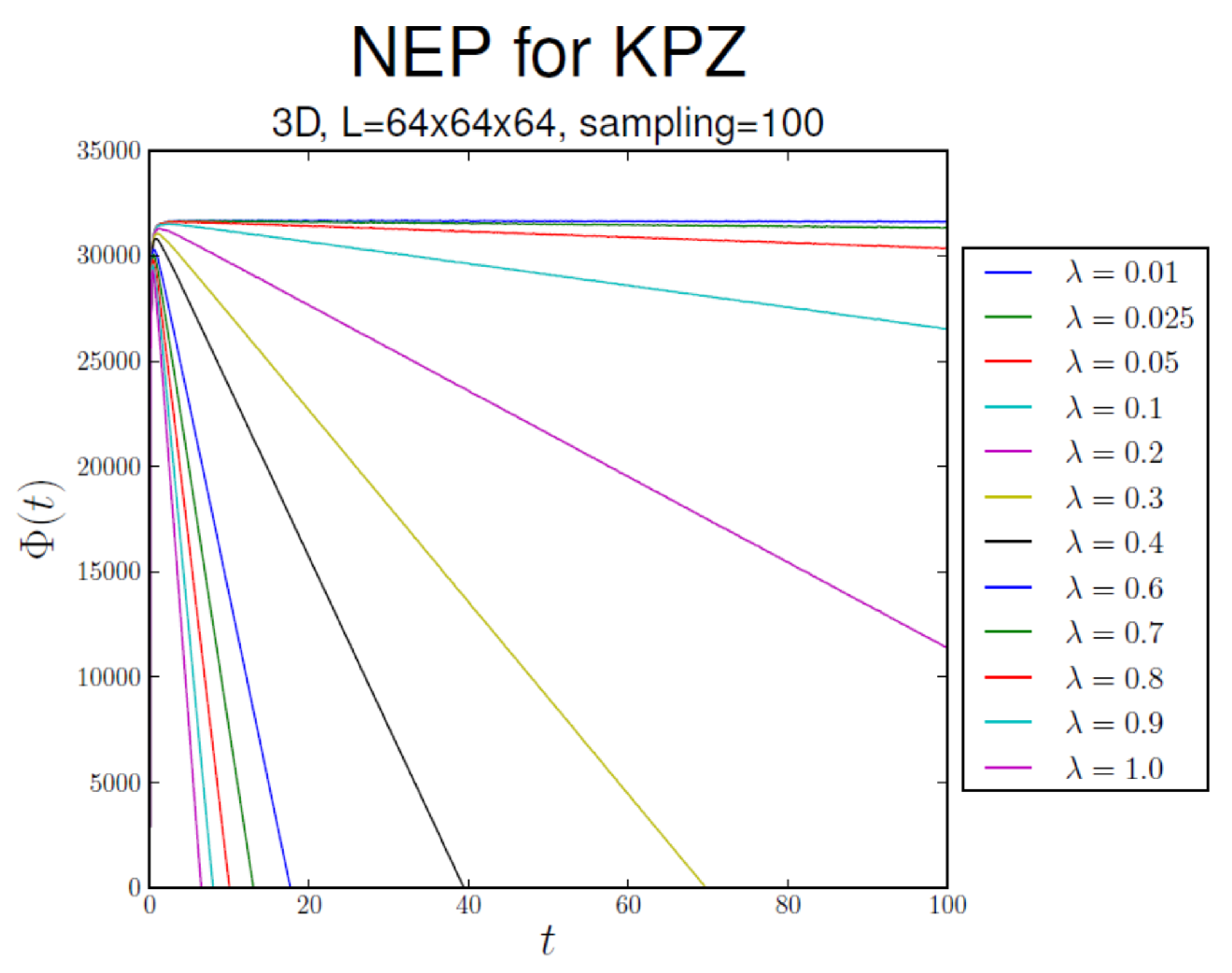

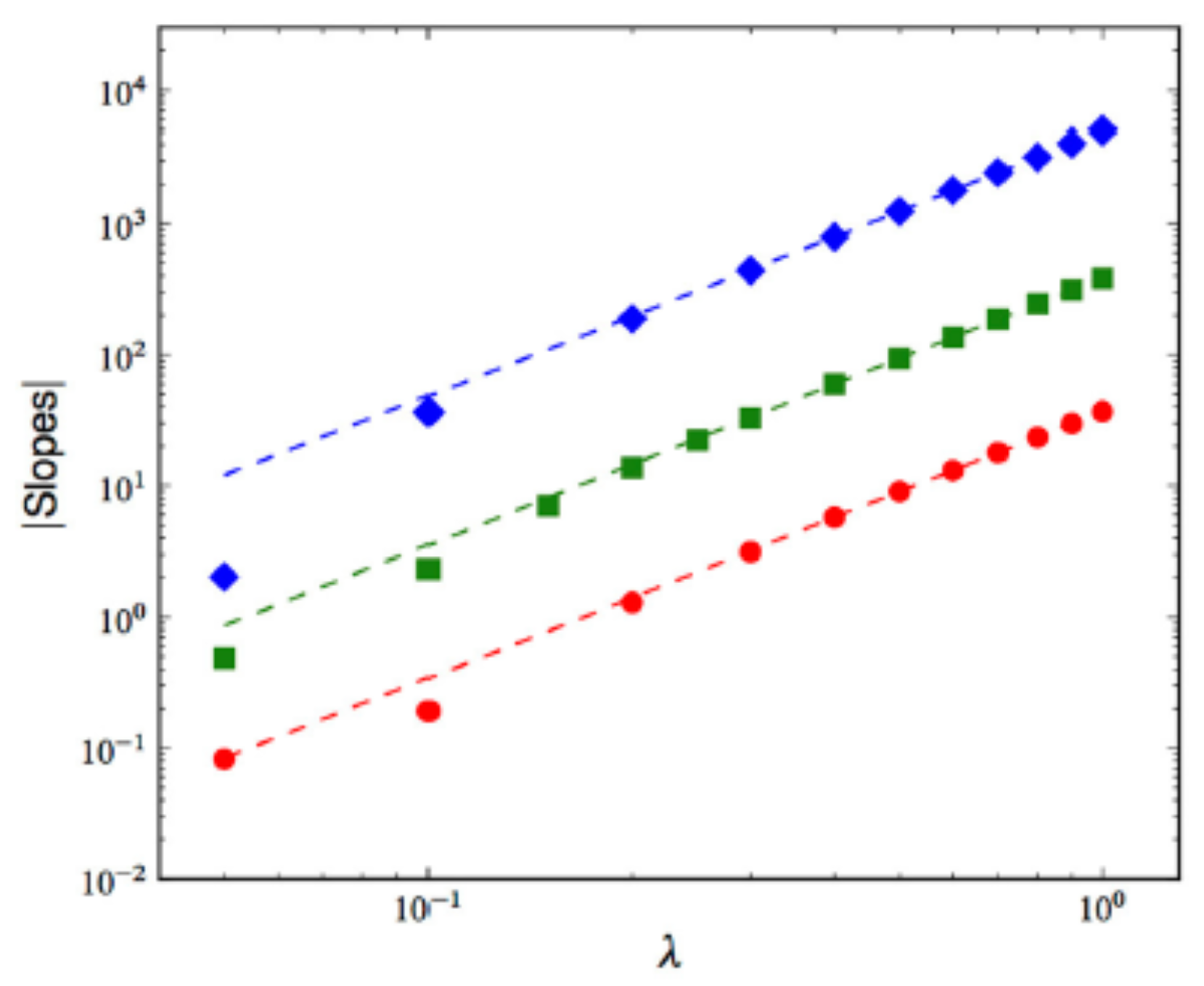

3. KPZ NEP’s Time Behavior and Its -Dependence

4. Novel Results

4.1. Stochastic Thermodynamics

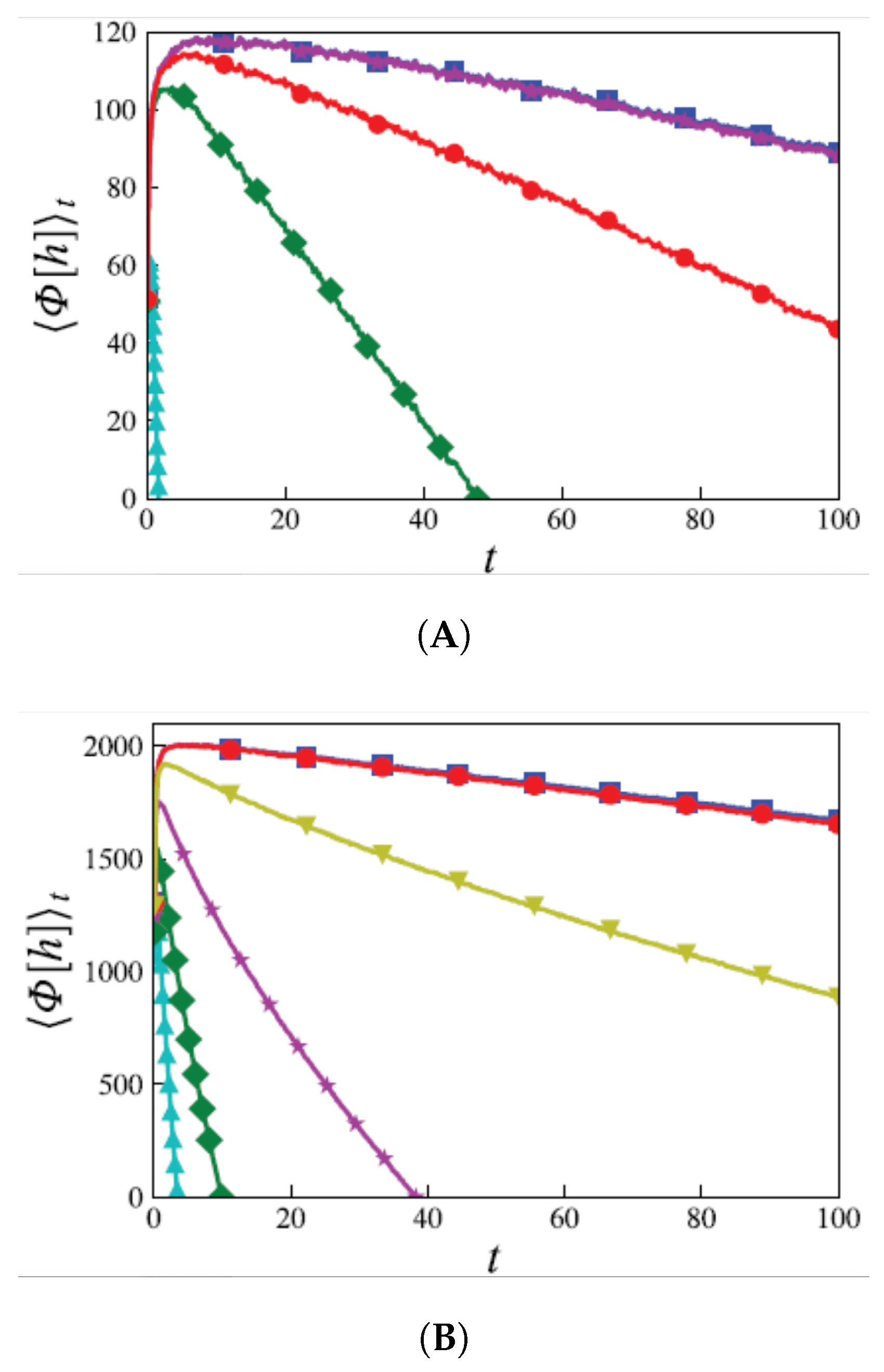

4.2. Memory of Initial Conditions in KPZ

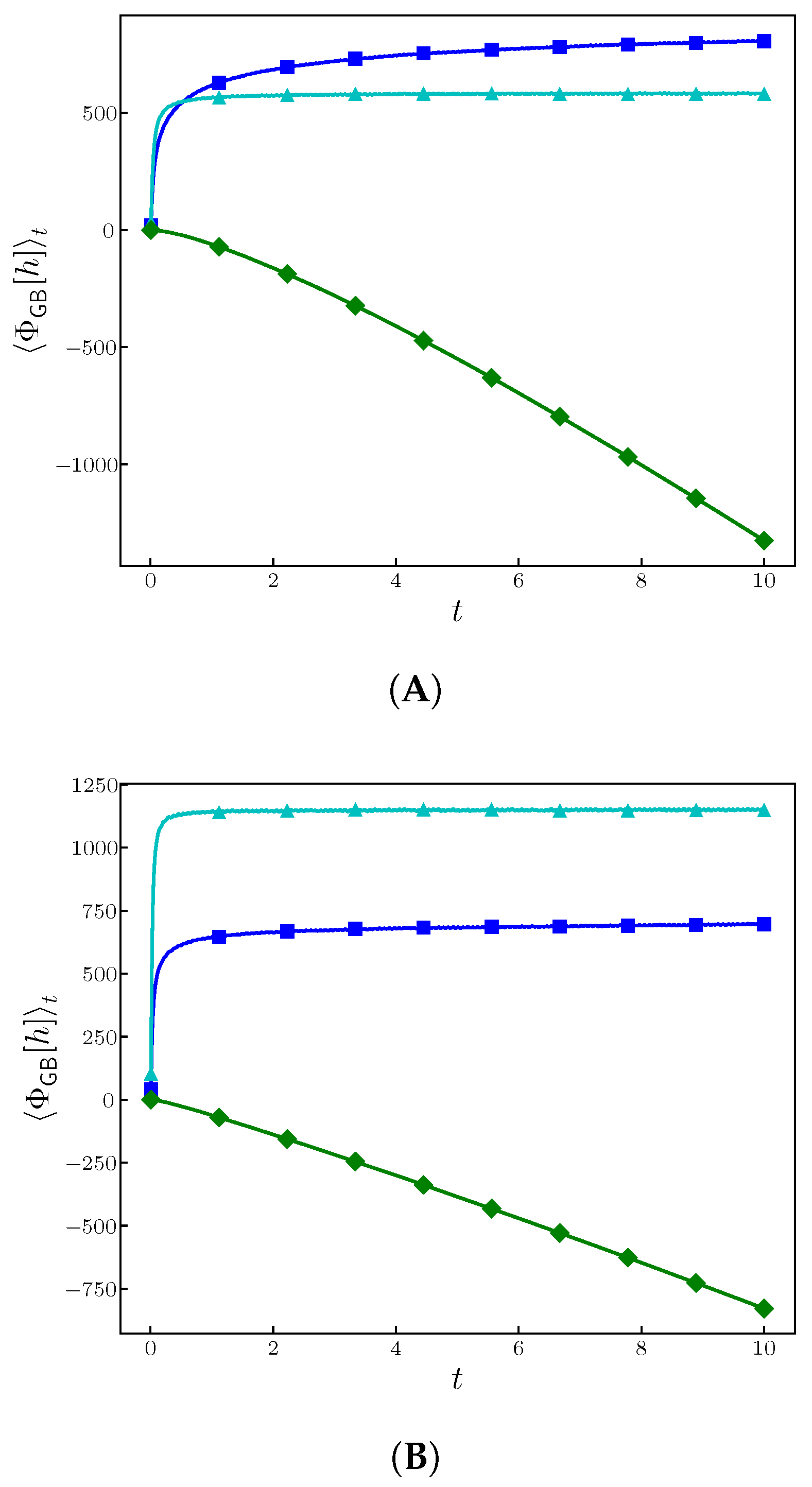

4.3. The Related Golubović–Bruinsma Model

4.4. Isolating the Collective Mode

5. Conclusions and Outlook

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kardar, M.; Parisi, G.; Zhang, Y.C. Dynamic scaling of growing interfaces. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1986, 56, 889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hairer, M. Solving the KPZ equation. Ann. Math. 2013, 178, 559–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vicsék, T.; Cserzö, M.; Horváth, V. Self-affine growth of bacterial colonies. Phys. A Stat. Mech. Its Appl. 1990, 167, 315–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okubo, A.; Levin, S.A. Diffusion and Ecological Problems: Modern Perspectives; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Murray, J.D. Mathematical Biology: I. An Introduction, 2nd ed.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Turchin, P. Quantitative Analysis of Movement: Measuring and Modeling Population Redistribution in Animals and Plants; Sinauer Associates: Sunderland, MA, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Fortin, M.J.; Dale, M.R.T. Spatial Analysis: A Guide for Ecologists; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Bartumeus, F.; da Luz, M.G.E.; Viswanathan, G.M.; Catalan, J. Animal Search strategies: A Quantitative Random-Walk Analysis. Ecology 2005, 86, 3078–3087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Codling, E.A.; Plank, M.J.; Benhamou, S. Random walk models in biology. J. R. Soc. Interface 2008, 5, 813–834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morales, J.M.; Moorcroft, P.R.; Matthiopoulos, J.; Frair, J.L.; Kie, J.G.; Powell, R.A.; Haydon, D.T. Building the Bridge between Animal Movement and Population Dynamics. Phil. Trans R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 2010, 365, 2289–2301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takeuchi, K.A.; Sano, M.; Sasamoto, T.; Spohn, H. Growing interfaces uncover universal fluctuations behind scale invariance. Sci. Rep. 2011, 1, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonachela, J.A.; Nadell, C.D.; Xavier, J.B.; Levin, S.A. Universality in bacterial colonies. J. Stat. Phys. 2011, 144, 303–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krieger, K. Coffee Stains Test Universal Equation. Physics 2013, 6, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, R.J.; Waclaw, B. Bacterial growth: A statistical physicist’s guide. Rep. Prog. Phys. 2018, 82, 016601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards, S.F.; Wilkinson, D.R. The surface statistics of a granular aggregate. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. A 1982, 381, 17–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golubović, L.; Bruinsma, R. Surface diffusion and fluctuations of growing interfaces. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1991, 66, 321–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barabási, A.L.; Stanley, H.E. Fractal Concepts in Surface Growth; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Wio, H.S. Variational formulation for the KPZ and related kinetic equations. Int. J. Bif. Chaos 2009, 19, 2813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hohenberg, P.C.; Halperin, B.I. Theory of dynamic critical phenomena. Rev. Mod. Phys. 1977, 49, 435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hentschel, H. Shift invariance and surface growth. J. Phys. A Math. Gen. 1994, 27, 2269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutiérrez, R.; Cuerno, R. Nonequilibrium criticality driven by Kardar–Parisi–Zhang fluctuations in the synchronization of oscillator lattices. Phys. Rev. Res. 2023, 5, 023047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutiérrez, R.; Cuerno, R. Kardar–Parisi–Zhang fluctuations in the synchronization dynamics of limit-cycle oscillators. Phys. Rev. Res. 2024, 6, 033324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutiérrez, R.; Cuerno, R. Kardar–Parisi–Zhang universality class in the synchronization of oscillator lattices with time-dependent noise. Phys. Rev. E 2024, 110, L052201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutiérrez, R.; Cuerno, R. Influence of coupling symmetries and noise on the critical dynamics of synchronizing oscillator lattices. Phys. D Nonlinear Phenom. 2025, 473, 134552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomes-Filho, M.S.; Oliveira, F.A. The hidden fluctuation–dissipation theorem for growth. Europhys. Lett. 2021, 133, 10001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomes-Filho, M.S.; de Castro, P.; Liarte, D.B.; Oliveira, F.A. Restoring the fluctuation—Dissipation theorem in Kardar–Parisi–Zhang universality class through a new emergent fractal dimension. Entropy 2024, 26, 260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wio, H.S.; Revelli, J.A.; Deza, R.R.; Escudero, C.; de La Lama, M.S. KPZ equation: Galilean-invariance violation, consistency, and fluctuation—Dissipation issues in real-space discretization. Europhys. Lett. 2010, 89, 40008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wio, H.S.; Revelli, J.A.; Deza, R.R.; Escudero, C.; de La Lama, M.S. Discretization-related issues in the Kardar–Parisi–Zhang equation: Consistency, Galilean-invariance violation, and fluctuation—Dissipation relation. Phys. Rev. E 2010, 81, 066706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Family, F.; Vicsék, T. Scaling of the active zone in the Eden process on percolation networks and the ballistic deposition model. J. Phys. A 1985, 18, L75–L81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prähofer, M.; Spohn, H. Statistical self-similarity of one-dimensional growth processes. Phys. A Stat. Mech. Its Appl. 2000, 279, 342–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prähofer, M.; Spohn, H. Universal distributions for growth processes in 1 + 1 dimensions and random matrices. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2000, 84, 4882–4885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sasamoto, T.; Spohn, H. One-dimensional Kardar–Parisi–Zhang equation: An exact solution and its universality. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2010, 104, 230602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calabrese, P.; Le Doussal, P. Exact solution for the Kardar–Parisi–Zhang equation with flat initial conditions. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2011, 106, 250603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corwin, I. The Kardar–Parisi–Zhang equation and universality class. Random Matrices Theory Appl. 2012, 1, 1130001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imamura, T.; Sasamoto, T. Exact solution for the stationary Kardar–Parisi–Zhang equation. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2012, 108, 190603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wio, H.; Deza, J.; Sánchez, A.; García-García, R.; Gallego, R.; Revelli, J.; Deza, R. The nonequilibrium potential today: A short review. Chaos Solitons Fractals 2022, 165, 112778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wio, H.S.; Rodríguez, M.A.; Gallego, R.; Revelli, J.A.; Alés, A.; Deza, R.R. d–Dimensional KPZ equation as a stochastic gradient flow in an evolving landscape: Interpretation, parameter dependence, and asymptotic form. Front. Phys. 2017, 4, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wio, H.S. Path Integrals for Stochastic Processes; World Scientific: Singapore, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Langouche, F.; Roekaerts, D.; Tirapegui, E. Functional Integration and Semiclassical Expansions; Reidel: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Wio, H.; Rodríguez, M.; Gallego, R. Variational approach to KPZ: Fluctuation theorems and large deviation function for entropy production. Chaos 2020, 30, 073107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodríguez, M.; Gallego, R.; Wio, H. Stochastic entropies and fluctuation theorems for a generic 1D KPZ system: Internal and external dynamics. Europhys. Lett. 2021, 116, 58005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Funaki, T.; Quastel, J. KPZ equation, its renormalization and invariant measures. Stoch. Partial. Differ. Equ. Anal. Comput. 2014, 3, 159–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niggemann, O.; Seifert, U. Field-Theoretic Thermodynamic Uncertainty Relation. J. Stat. Phys. 2020, 178, 1142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takeuchi, K.A. Crossover from growing to stationary interfaces in the Kardar–Parisi–Zhang class. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2013, 110, 210604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meerson, B.; Vilenkin, A. Large deviations of the interface height in the Golubovic-Bruinsma model of stochastic growth. Phys. Rev. E 2023, 108, 014117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janas, J.; Kamenev, A.; Meerson, B. Dynamical phase transition in large-deviation statistics of the Kardar-Parisi-Zhang equation. Phys. Rev. E 2016, 94, 032133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sasorov, P.; Meerson, B.; Prolhac, S. Large deviations of surface height in the 1 + 1-dimensional Kardar–Parisi–Zhang equation: Exact long-time results for λH < 0. J. Stat. Mech. 2017, 2017, 063203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Wio, H.S.; Deza, R.R.; Revelli, J.A.; Gallego, R.; García-García, R.; Rodríguez, M.A. The KPZ Equation of Kinetic Interface Roughening: A Variational Perspective. Entropy 2026, 28, 55. https://doi.org/10.3390/e28010055

Wio HS, Deza RR, Revelli JA, Gallego R, García-García R, Rodríguez MA. The KPZ Equation of Kinetic Interface Roughening: A Variational Perspective. Entropy. 2026; 28(1):55. https://doi.org/10.3390/e28010055

Chicago/Turabian StyleWio, Horacio S., Roberto R. Deza, Jorge A. Revelli, Rafael Gallego, Reinaldo García-García, and Miguel A. Rodríguez. 2026. "The KPZ Equation of Kinetic Interface Roughening: A Variational Perspective" Entropy 28, no. 1: 55. https://doi.org/10.3390/e28010055

APA StyleWio, H. S., Deza, R. R., Revelli, J. A., Gallego, R., García-García, R., & Rodríguez, M. A. (2026). The KPZ Equation of Kinetic Interface Roughening: A Variational Perspective. Entropy, 28(1), 55. https://doi.org/10.3390/e28010055