Micro Fault Diagnosis of Driving Motor Bearings Based on Multi-Residual Neural Networks and Evidence Reasoning Rule

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. The Theoretical Basis

2.1. Information Transformation

2.2. Training and Reasoning of Residual Neural Networks

2.3. Diagnostic Condition Assessment

2.4. Diagnostic Category Assessment

3. Performance Verification and Result Analysis

3.1. Case Description and Model Construction

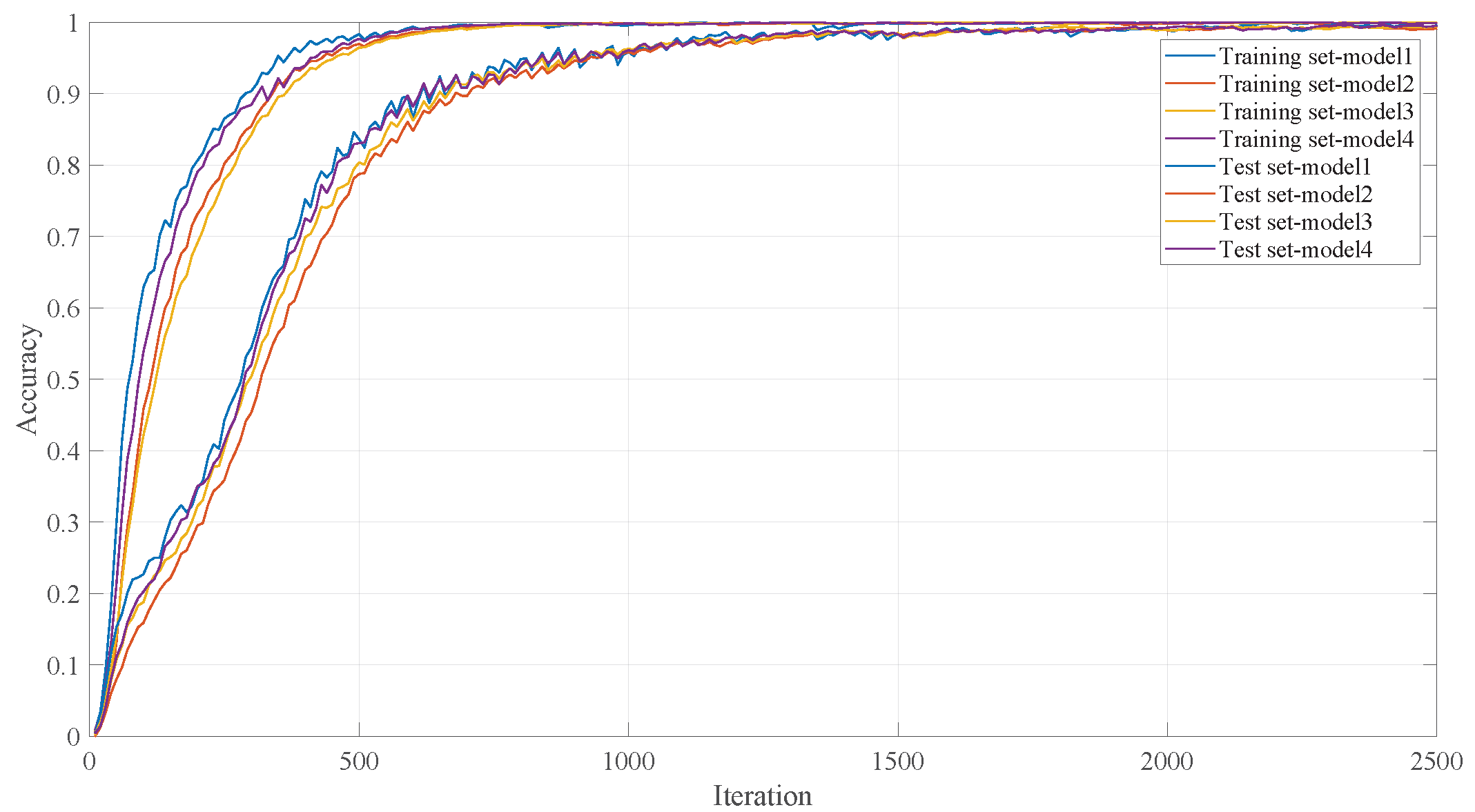

3.2. Model Training and Result Analysis

3.3. Experimental Comparison

4. Conclusions

- 1.

- A diagnostic model employing a benchmark condition generalization mechanism was proposed, which selects multiple typical load conditions as diagnostic anchor points based on a multi-residual neural network structure.

- 2.

- By integrating a sub-model credibility assessment mechanism to perform diagnostic condition assessment and category assessment based on ER rule, this model achieves micro-fault diagnosis under varying vehicle operating conditions.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ER Rule | Evidence Reasoning Rule |

| ResNet | Residual Network |

| STFT | Short-Time Fourier Transform |

| BP | Back Propagation network |

| RBF | Radial Basis Function network |

| SVM | Support Vector Machine |

| ES | Expert System |

| UKF | Unscented Kalman Filter |

| CFMDAS | Car Failure and Malfunction Diagnosis Assistance System |

| OLA | Online Approximator |

| ANN | Artificial Neural Network |

| EMD | Empirical Mode Decomposition |

| CWRU | Case Western Reserve University |

| HP | horsepower |

| RPM | Revolutions Per Minute |

| A-IBRB | automatic interval belief rule base |

| CMA-ES | Covariance Matrix Adaptation Evolutionary Strategies |

References

- Afgan, N.H.; Carvalho, M.G.; Pilavachi, P.A.; Tourlidakis, A.; Olkhonski, G.G.; Martins, N. An expert system concept for diagnosis and monitoring of gas turbine combustion chambers. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2006, 26, 766–771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrea, T.; Andrea, L. Energy system diagnosis by a fuzzy expert system with genetically evolved rules. Int. J. Thermodyn. 2008, 11, 115–121. [Google Scholar]

- Nan, C.; Khan, F.; Iqbal, M.T. Real-time fault diagnosis using knowledge-based expert system. Process Saf. Environ. Protection 2008, 86, 55–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mostafa, S.A.; Ahmad, M.S.; Mohammed, M.A.; Obaid, O.I. Implementing an expert diagnostic assistance system for car failure and malfunction. Int. J. Comput. Sci. Issues 2012, 9, 1694–1814. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, B.; Jiang, Z.-N.; Wei, Z.-Q. Development of the task-based expert system for machine fault diagnosis. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2012, 364, 012043. [Google Scholar]

- Kodavade, D.V.; Apte, S.D. A universal object oriented expert system frame work for fault diagnosis. Int. J. Intell. Sci. 2012, 2, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, H.; Zhang, Z.; He, W.; Li, M.; Zhu, H. A new automated interval structure belief rule base-based fault diagnosis method for complex systems. Nonlinear Dyn. 2025, 113, 8391–8422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsiao, T.; Weng, M.C. A hierarchical multiple-model approach for detection and isolation of robotic actuator faults. Robot. Auton. Syst. 2012, 60, 154–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Q.M.; Sun, Y.X. Automated fault accommodation for discrete-time systems using online approximators. In Proceedings of the 30th Chinese Control Conference, Shanghai, China, 22–24 July 2011; pp. 4264–4269. [Google Scholar]

- Avram, R.C.; Zhang, X.; Muse, J. Quadrotor actuator fault diagnosis and accommodation using nonlinear adaptive estimators. IEEE Trans. Control Syst. Technol. 2017, 25, 2219–2226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, B.; Skjetne, R.; Blanke, M.; Dukan, F. Particle filter for fault diagnosis and robust navigation of underwater robot. IEEE Trans. Control Syst. Technol. 2014, 22, 2399–2407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barman, D.; Sarkar, S.; Das, G.; Das, S.; Purkait, P. DFA and DWT based severity detection and discrimination of induction motor stator winding short circuit fault from incipient insulation failure. In Proceedings of the 2015 International Conference on Electrical, Electronics, Signals, Communication, and Optimization, Visakhapatnam, India, 24–25 January 2015; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Sugumaran, V.; Rao, A.V.; Ramachandran, K.I. A comprehensive study of fault diagnostics of roller bearings using continuous wavelet transform. Int. J. Manuf. Syst. Des. 2015, 1, 27–46. [Google Scholar]

- Liang, J.; Yang, Z.X. A novel wavelet transform-empirical mode decomposition based sample entropy and SVD approach for acoustic signal fault diagnosis. In Proceedings of the 6th International Conference on Advances in Swarm and Computational Intelligence, Beijing, China, 25–28 June 2015; pp. 232–241. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Z.Y.; Wang, Y.; Wang, K.S. Fault diagnosis and prognosis using wavelet packet decomposition, Fourier transform and artificial neural network. J. Intell. Manuf. 2013, 24, 1213–1227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Namdari, M.; Jazayeri-Rad, H. Incipient fault diagnosis using support vector machines based on monitoring continuous decision functions. Eng. Applicat. Artif. Intell. 2014, 28, 22–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Cun, Y.; Bengio, Y.; Hinton, G. Deep learning. Nature 2015, 521, 436–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krizhevsky, A.; Sutskever, I.; Hinton, G.E. Image Net Classification with Deep Convolutional Neural Networks. 2012. Available online: https://proceedings.neurips.cc/paper_files/paper/2012/file/c399862d3b9d6b76c8436e924a68c45b-Paper.pdf (accessed on 1 December 2025).

- Szegedy, C.; Liu, W.; Jia, Y.; Sermanet, P.; Reed, S.; Anguelov, D.; Erhan, D.; Vanhoucke, V.; Rabinovich, A. Going deeper with convolutions. In Proceedings of the 2015 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Boston, MA, USA, 7–12 June 2015; pp. 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Girshick, R.; Donahue, J.; Darrell, T.; Malik, J. Rich feature hierarchies for accurate object detection and semantic segmentation. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Denver, CO, USA, 3–7 June 2026. [Google Scholar]

- Ren, S.; He, K.; Girshick, R.; Sun, J. Faster R-CNN: Towards real-time object detection with region proposal networks. ArXiv 2015, arXiv:1506.01497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szegedy, C.; Vanhoucke, V.; Ioffe, S.; Shlens, J.; Wojna, Z. Rethinking the Inception Architecture for Computer Vision. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Las Vegas, NV, USA, 27–30 June 2016; pp. 2818–2826. [Google Scholar]

- Szegedy, C.; Ioffe, S.; Vanhoucke, V.; Alemi, A. Inception-v4, Inception-ResNet and the Impact of Residual Connections on Learning. arXiv 2016, arXiv:1602.07261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, K.; Zhang, X.; Ren, S.; Sun, J. Deep Residual Learning for Image Recognition. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Las Vegas, NV, USA, 27–30 June 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Bao, H.; Dong, L.; Wei, F. BEiT: BERT Pre-Training of Image Transformers. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2106.08254. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, T.Y.; Goyal, P.; Girshick, R.; He, K.; Dollar, P. Focal Loss for Dense Object Detection. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), Venice, Italy, 22–29 October 2017; pp. 2999–3007. [Google Scholar]

- Griffin, D. Signal estimation from modified short-time Fourier transform. IEEE Trans. Acoust. Speech Signal Process. 1984, 32, 236–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwok, H.K.; Jones, D.L. Improved instantaneous frequency estimation using an adaptive short-time Fourier transform. IEEE Trans. Signal Process. 2000, 48, 2964–2972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.J.; Zhang, S.; Miao, C.X.; Li, Y.M. Improved BP Neural Network for Transformer Fault Diagnosis. J. China Univ. Min. Technol. 2007, 17, 138–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, Q.; Zhan-Ming, L.; Er-Chao, L. Fault detection and diagnosis for non-Gaussian stochastic distribution systems with time delays via RBF neural networks. ISA Trans. 2012, 51, 786–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, G.; Cheng, H.; Zhai, H.; Dong, L. Fault diagnosis of power transformer based on multi-layer SVM classifier. Proc. Chin. Soc. Univ. 2005, 75, 9–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Motor Load (HP) | Motor Speed (rpm) | Normal | Inner Raceway | Ball | Outer Raceway Center |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 1797 | - | 7 mils | 7 mils | 7 mils |

| 1 | 1772 | - | 7 mils | 7 mils | 7 mils |

| 2 | 1750 | - | 7 mils | 7 mils | 7 mils |

| 3 | 1730 | - | 7 mils | 7 mils | 7 mils |

| Residual Unit | Output Size | Network Layer Parameters | Unit Number | Sub-Model Number |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| - | 112 × 112 | 7 × 7 conv, 64/2 | 1 | 4 |

| - | 56 × 56 | 3 × 3 max pool, 64/2 | 1 | |

| unit_1 | 56 × 56 | 1 × 1, 64; 3 × 1, 64; 1 × 3, 64; 1 × 1, 256 | 2 | |

| unit_1 | 56 × 56 | 1 × 1, 64; 3 × 1, 64; 1 × 3, 64/2; 1 × 1, 256 | 1 | |

| unit_2 | 28 × 28 | 1 × 1, 128; 3 × 1, 128; 1 × 3, 128; 1 × 1, 512 | 3 | |

| unit_2 | 28 × 28 | 1 × 1, 128; 3 × 1, 128; 1 × 3, 128/2; 1 × 1, 512 | 1 | |

| unit_3 | 14 × 14 | 1 × 1, 256; 3 × 1, 256; 1 × 3, 256; 1 × 1, 1024 | 5 | |

| unit_3 | 14 × 14 | 1 × 1, 256; 3 × 1, 256; 1 × 3, 256/2; 1 × 1, 1024 | 1 | |

| unit_4 | 7 × 7 | 1 × 1, 512; 3 × 1, 512; 1 × 3, 512; 1 × 1, 2048 | 2 | |

| unit_4 | 7 × 7 | 1 × 1, 512; 3 × 1, 512; 1 × 3, 512/2; 1 × 1, 2048 | 1 | |

| 1 × 7 × 2 | 1 × 1 | 7 × 7 mean pool, 2048 | 1 | |

| 1 × 7 × 2 | - | 4 fc, Softmax | 1 | |

| ER Rule | 1 | |||

| Model | Training Set | Test Set |

|---|---|---|

| Multi-ResNet-67 + ER Rule | 0.9916 | 0.9734 |

| Wavelet packet + BP | 0.9772 | 0.9646 |

| Wavelet packet + RBF | 0.9706 | 0.9553 |

| Wavelet packet + SVM | 0.9634 | 0.9521 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Zhang, A.; Tang, L.; Hu, G. Micro Fault Diagnosis of Driving Motor Bearings Based on Multi-Residual Neural Networks and Evidence Reasoning Rule. Entropy 2026, 28, 53. https://doi.org/10.3390/e28010053

Zhang A, Tang L, Hu G. Micro Fault Diagnosis of Driving Motor Bearings Based on Multi-Residual Neural Networks and Evidence Reasoning Rule. Entropy. 2026; 28(1):53. https://doi.org/10.3390/e28010053

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhang, Aoxiang, Lihong Tang, and Guanyu Hu. 2026. "Micro Fault Diagnosis of Driving Motor Bearings Based on Multi-Residual Neural Networks and Evidence Reasoning Rule" Entropy 28, no. 1: 53. https://doi.org/10.3390/e28010053

APA StyleZhang, A., Tang, L., & Hu, G. (2026). Micro Fault Diagnosis of Driving Motor Bearings Based on Multi-Residual Neural Networks and Evidence Reasoning Rule. Entropy, 28(1), 53. https://doi.org/10.3390/e28010053