Efficient Privacy-Preserving Face Recognition Based on Feature Encoding and Symmetric Homomorphic Encryption

Abstract

1. Introduction

- What facial information should be encrypted? Suppose a color facial image is 1024 × 1024 × 3 bytes. If homomorphic encryption is directly applied to the image, it would require encrypting 1024 × 1024 × 3 = 3,145,728 times. However, if the facial feature vector (1024 bytes after dimensionality reduction) is encrypted, it would only require 1024 encryptions.

- Which encryption algorithm should be chosen to encrypt facial feature information? When the server performs facial matching similarity calculations or processes result bits, using plaintext for these operations risks data leakage, with the final decision-making power residing on the server. What encryption algorithm can ensure the privacy of the user’s facial data while transferring the decision-making authority for face verification to the client? If a homomorphic encryption algorithm is adopted, which includes partial homomorphic encryption, fully homomorphic encryption, and symmetric homomorphic encryption, which homomorphic encryption scheme should be selected to encrypt facial feature vectors in this approach?

- How can facial feature templates be searched in ciphertext? The server performs similarity computation on ciphertext, requiring the corresponding facial feature ciphertext to be retrieved first. Using a brute-force search approach would reduce the efficiency of facial matching. Therefore, a retrieval method is needed to improve matching efficiency while preventing facial privacy leakage.

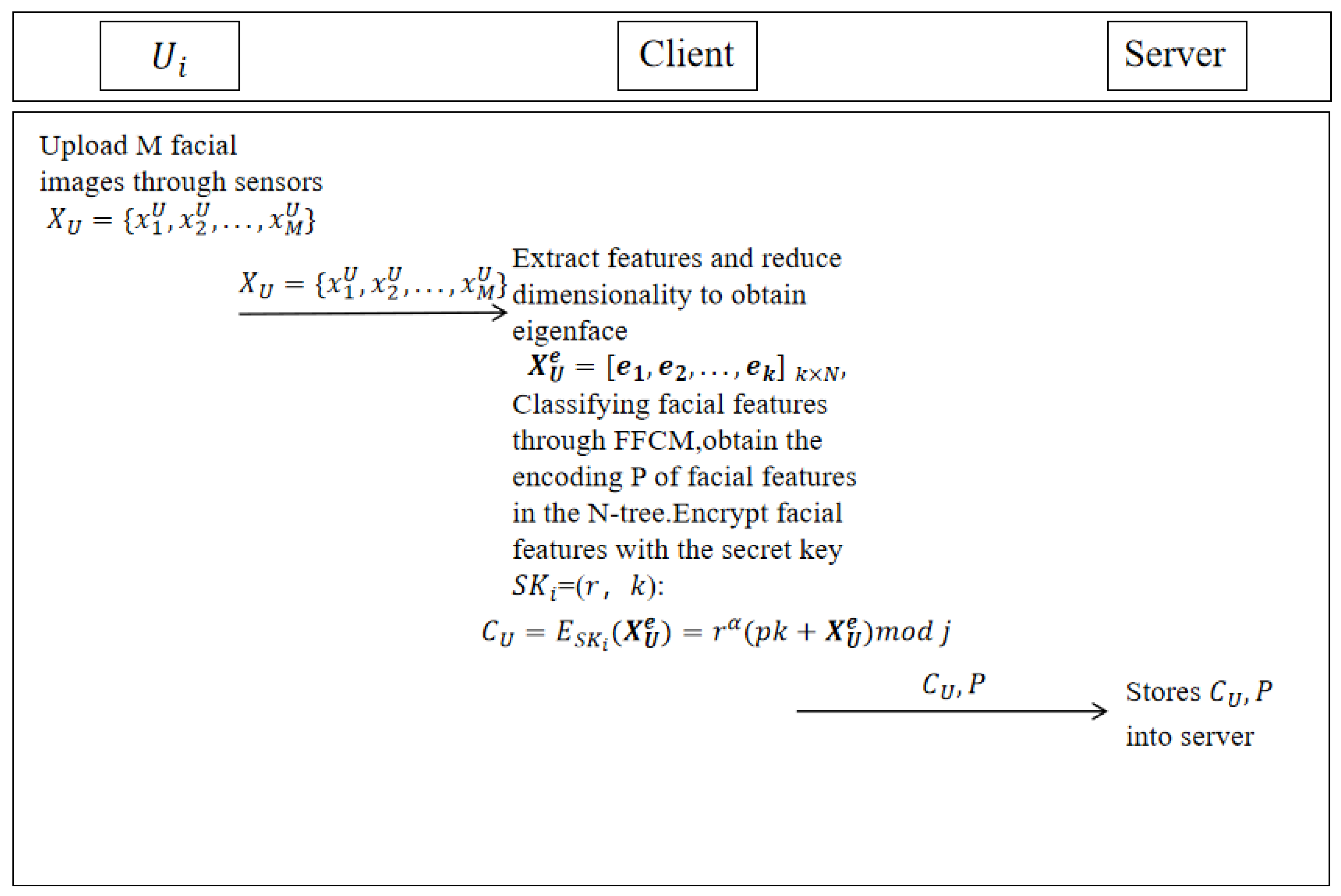

- This paper encrypts the user’s facial features instead of the facial image itself, which significantly reduces the encryption time and enhances the matching efficiency. Principal Component Analysis (PCA) is used to reduce the dimensionality of facial images, which not only decreases storage requirements but also shortens the encryption time.

- A lightweight symmetric homomorphic encryption algorithm is employed to encrypt facial features and decrypt similar ciphertexts. The encryption and decryption operations of the symmetric homomorphic encryption algorithm are carried out on the client side. Homomorphic encryption supports modular addition and multiplication on ciphertexts within a finite field, making it well-suited for the cosine similarity algorithm. This approach ensures that the server can compute the similarity of facial features without accessing the user’s private facial data.

- A facial feature encoding method (FFCM) is proposed, which constructs a facial classification model and assigns corresponding encodings at each level of an N-ary tree. Through this N-ary tree, each leaf node stores a set of multiple facial feature vectors, with each user’s face being assigned a corresponding feature encoding. During the authentication phase, the server can quickly search within the classification set using the facial feature encoding (rather than performing a full-text search), thereby significantly accelerating the server-side matching process. Experimental results show that the face authentication efficiency with FFCM classification is 4.65% higher than that of a similar solution using homomorphic encryption [12], and 6.11% higher than [16].

2. Related Work

3. Preliminaries

3.1. Eigenface

3.2. Symmetric Homomorphic Encryption

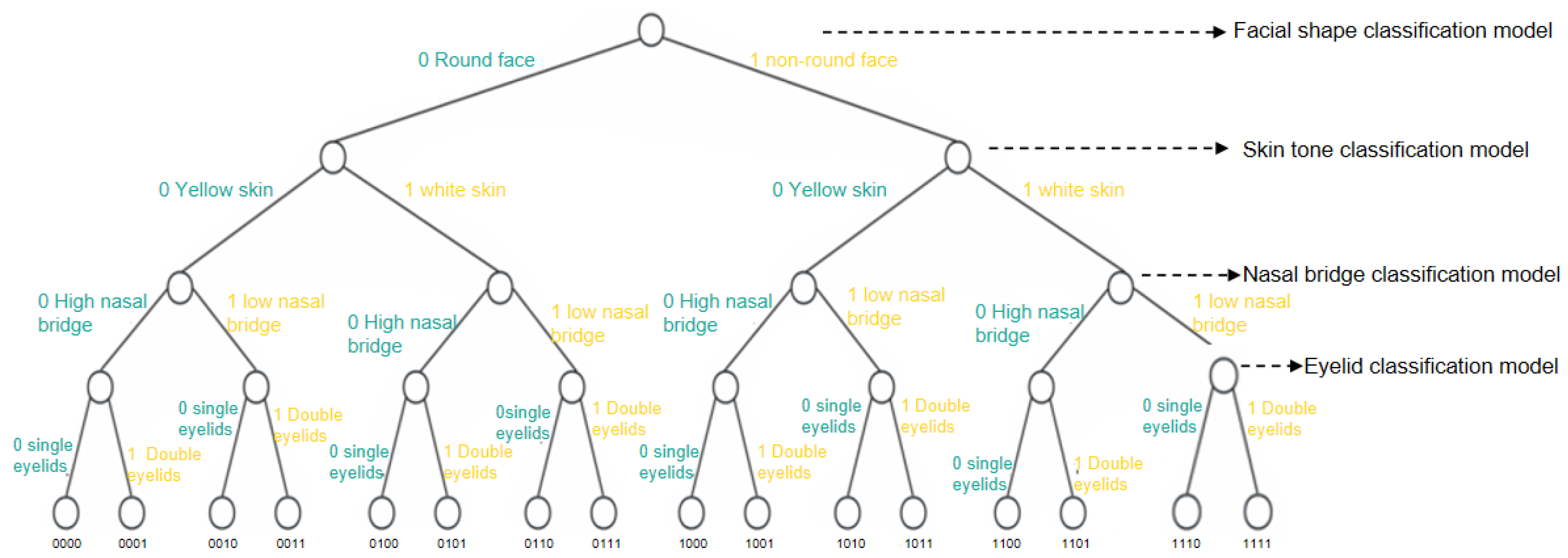

3.3. FFCM (Face Feature Coding Method)

3.4. System Model

3.5. Threat Model and Trust Assumptions

3.6. Security Requirements

- Mutual authentication: Two-way authentication between the client and the server is achieved through a challenge–response interaction mechanism based on dynamically generated session identifiers. In each authentication session, the client initiates communication by sending an authentication request containing a freshly generated session identifier. After receiving this request, the server generates its own challenge value and returns it together with verification information bound to the shared key established during system initialization. The client verifies the authenticity of the server’s response and then sends a confirmation message that allows the server to verify the client’s legitimacy. Only after both parties have successfully validated each other’s identities will the encrypted facial matching process be executed. Although mutual authentication protocols have been extensively studied and widely deployed in practical secure communication systems, the specific mechanism adopted in this work is tailored to our setting and aims to ensure freshness, prevent replay, and resist impersonation attacks. Therefore, the above description highlights only the parts relevant to our threat model rather than reiterating well-established authentication techniques. Each authentication round uses a unique session identifier and challenge value, ensuring that previously intercepted messages cannot be reused, thereby effectively preventing replay and impersonation attacks.

- Privacy of facial features: This article uses the symmetric encryption algorithm SHE to encrypt facial features, ensuring that the data is protected during transmission from tampering or leakage, thereby maintaining the integrity and privacy of the data. In the identity authentication stage, the server performs similarity calculation of facial features in encrypted state to ensure that the facial features and similarity have not been tampered with or leaked, thereby ensuring the integrity of the data during processing.

- User anonymous: It refers to the situation where the client encrypts and uploads the user’s facial features, and the server cannot steal the plaintext information of the user’s facial features. In the identity authentication stage, the homomorphic encryption algorithm is used to calculate the similarity during facial feature matching in ciphertext state, and the user’s facial features will not be leaked.

- Man-in-the-middle Attack: “Man in the middle attack” is a network security threat that refers to attackers stealing sensitive information or manipulating communication content by intercepting and tampering with data streams during the communication process. In man-in-the-middle attacks, attackers typically establish fake connections between the two ends of communication, causing both parties to mistakenly believe that they are communicating directly, when in fact all communication is under the control and monitoring of the attacker.

- Replay attack: This article uses the SHE algorithm to generate keys and select random and prime numbers during the initialization phase, ensuring the security and randomness of the keys and providing a stable foundation for subsequent steps.

- Insider attack: An “insider attack” refers to the situation where employees, partners, or other authorized users within an organization use their legitimate permissions or access rights to engage in malicious behavior against the organization’s information systems, data, or resources. These behaviors may be intentional or unintentional, but they can pose a serious threat to the security, data confidentiality, and availability of the organization.

4. Privacy Protection Method of Face Recognition Based on Symmetric Homomorphic Encryption

4.1. Initialization Stage

- (1)

- Define the node structure: The data domain of each node is used to store the node value of the face features (such as face shape, skin color, nose bridge, etc.). If the node has a child node, the node’s data domain also stores a pointer to the child node.

- (2)

- Create the root node of the N-ary tree: Define the data field of the root node as the first node value used to classify face features, such as face shape classification.

- (3)

- Add child nodes: Based on the root node, add child nodes to it, and add child nodes to existing nodes, so each node can have 1 to N child nodes.

- (4)

- Leaf node number: If the depth (number of layers) of the N-tree is h, H-1 categories are stored, and each leaf node stores all face features that match the path from the root node to the leaf node, and the leaf node is uniquely numbered according to the path.

- (5)

- The trained face classification model is matched to each layer node of the N-ary tree, and each layer node corresponds to a face classification model. The coding method FFCM (Face Feature Coding Method) based on face feature classification is constructed, with P = FFCM(X), where X represents the extracted face features and P represents the number of the leaf node.

4.2. Registration Phase

4.3. Authentication Phase

5. Security Analysis

5.1. Adversarial Model

- (1)

- Send (S, , ): This query simulates the adversary’s ability to act like a legitimate tag. In this context, A sends and receives from S.

- (2)

- Query (CT, , ): This query simulates the adversary’s ability to interrogate the client. To achieve this, A sends to and receives in response.

- (3)

- Execute (CT, S): This query simulates the adversary’s ability to continuously observe the radio channel between and S. In this scenario, A must intercept the channel during the execution of the protocol instance between and S.

- (4)

- Reveal (T): This query models A’s ability to access the contents of the server’s memory. In other words, this query simulates the adversary’s capability to compromise the server and retrieve the secrets stored in its memory.

- (1)

- C selects a valid server S and two clients and .

- (2)

- A invokes the oracle queries—Send, Query, and Execute—on S as well as on and , for an arbitrary polynomial number of times.

- (3)

- After invoking the oracles, A notifies C.

- (4)

- C randomly selects one of the clients, or .

- (5)

- A invokes the following oracle queries on S and the selected : Send, Query, and Execute.

- (6)

- A makes a prediction ; if , then A wins the game.

- (1)

- C selects a valid server S and client .

- (2)

- A invokes the oracle queries—Send, Query, and Execute—on S and , for an arbitrary polynomial number of times.

- (3)

- After invoking the oracles, A notifies C.

- (4)

- A invokes the Send oracle to simulate the client.

- (5)

- If A is able to prove herself as a legitimate client, then A wins the game.

- (1)

- In this scheme, the client strictly adheres to the computational principles of symmetric homomorphic encryption algorithms. Even if the server is honest yet curious, it cannot decrypt the face feature ciphertext without knowledge of the client’s key.

- (2)

- In the registration and authentication protocol of our scheme, there is no interaction between the user and the server; both only interact with the client. Therefore, the server cannot obtain any face feature information from the user.

5.2. Privacy Implications of FFCM Encoding

6. Experiment

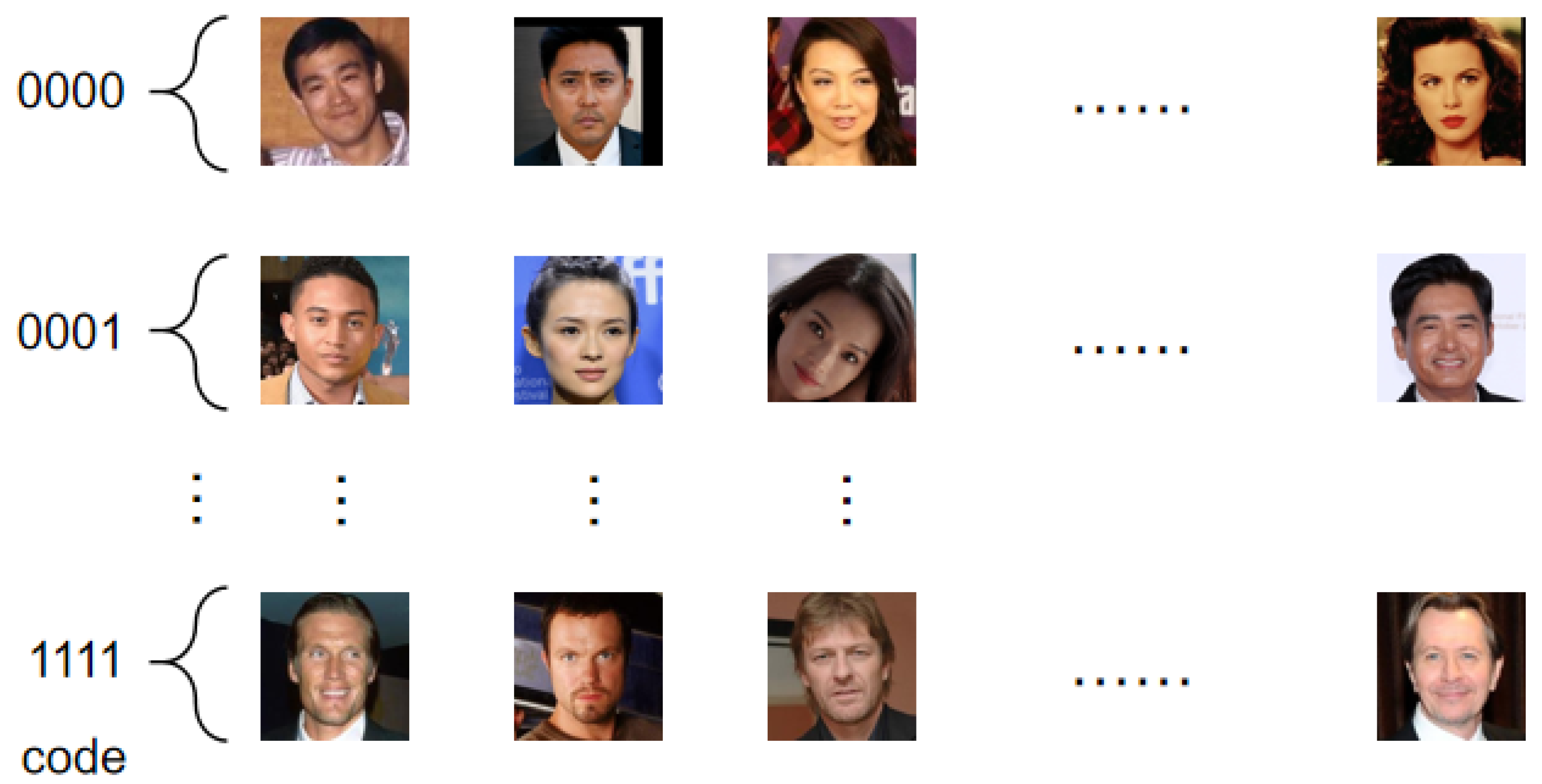

6.1. Dataset

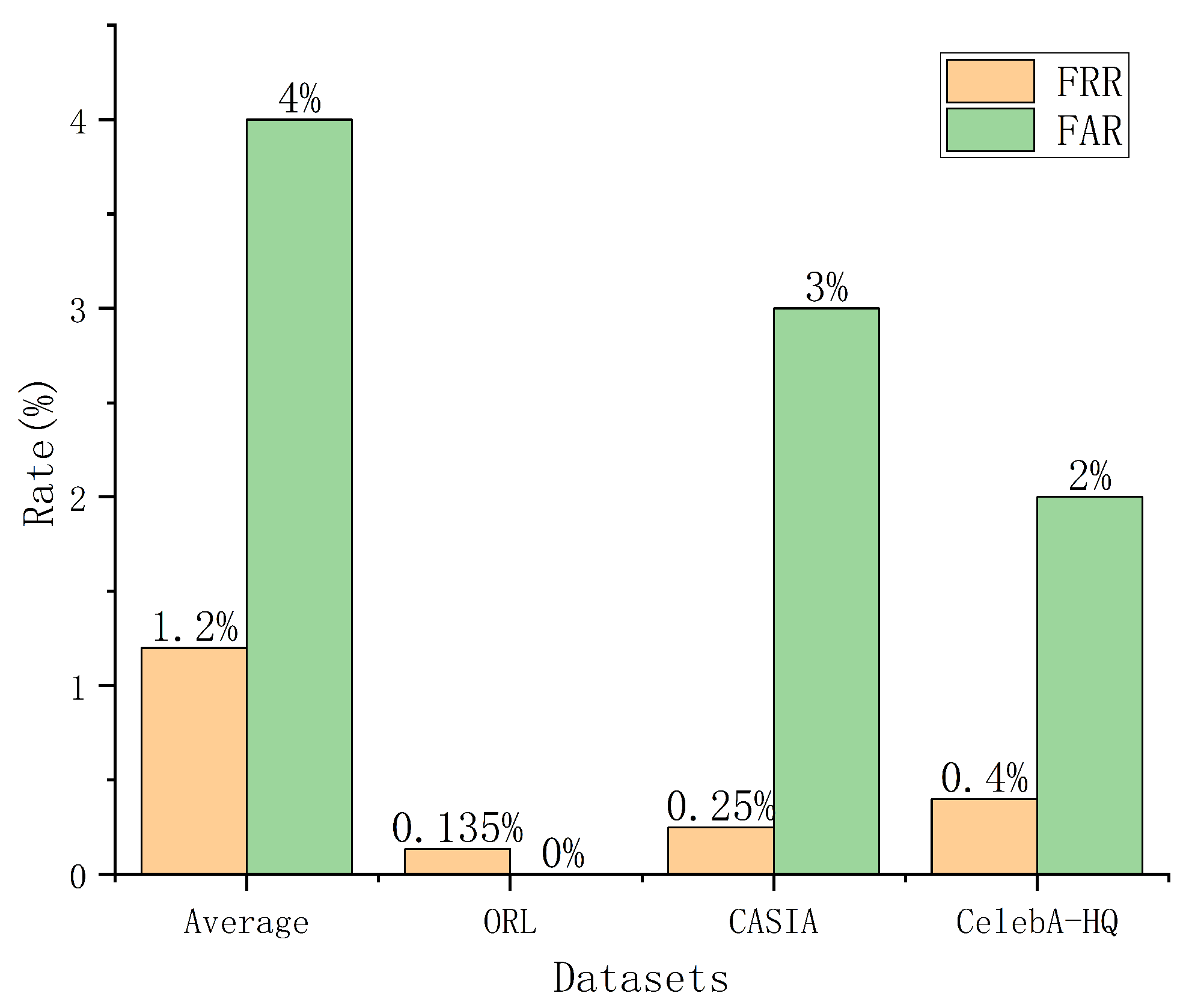

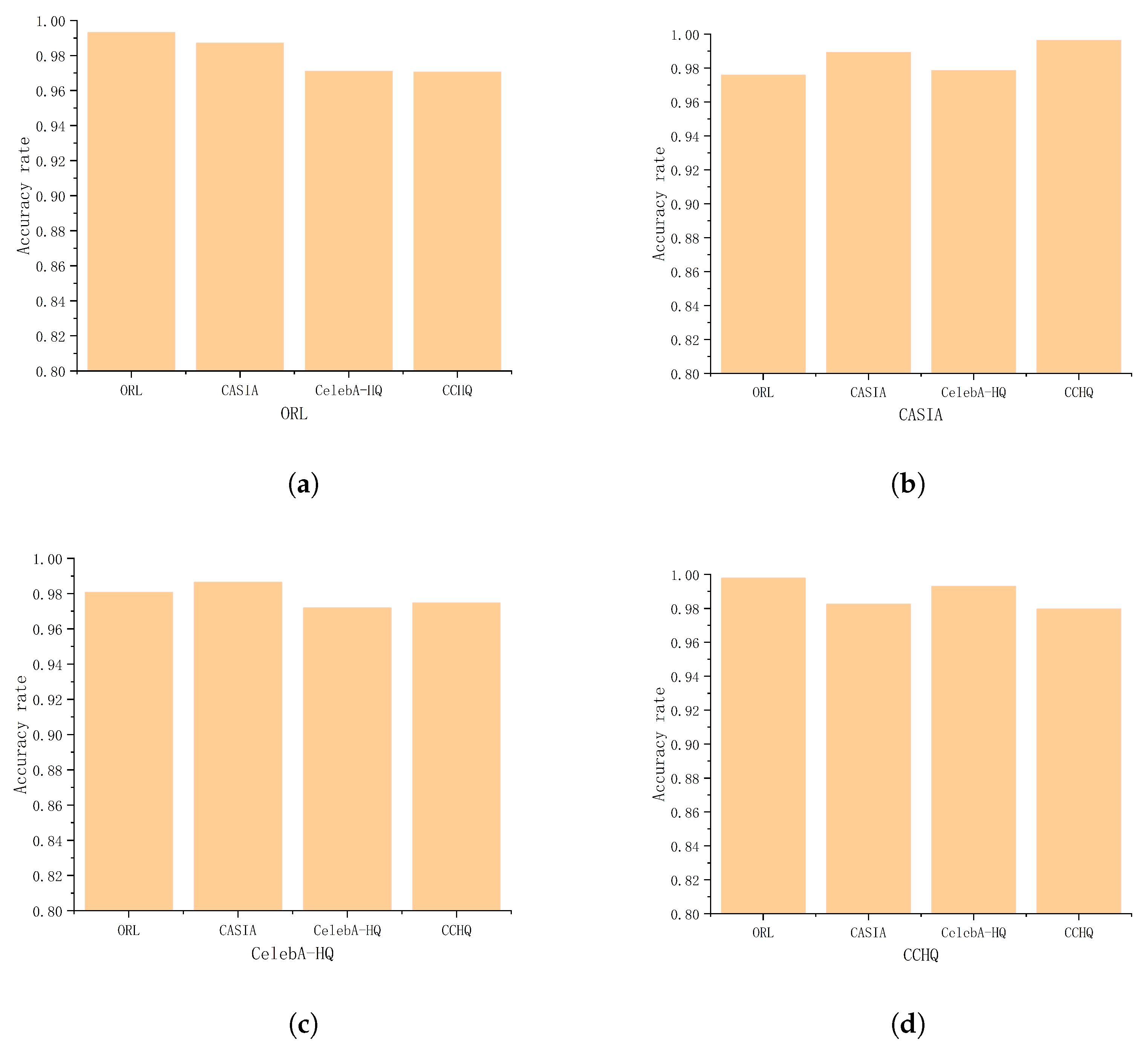

6.2. Recognition Performance

6.3. Correlation Parameter Analysis

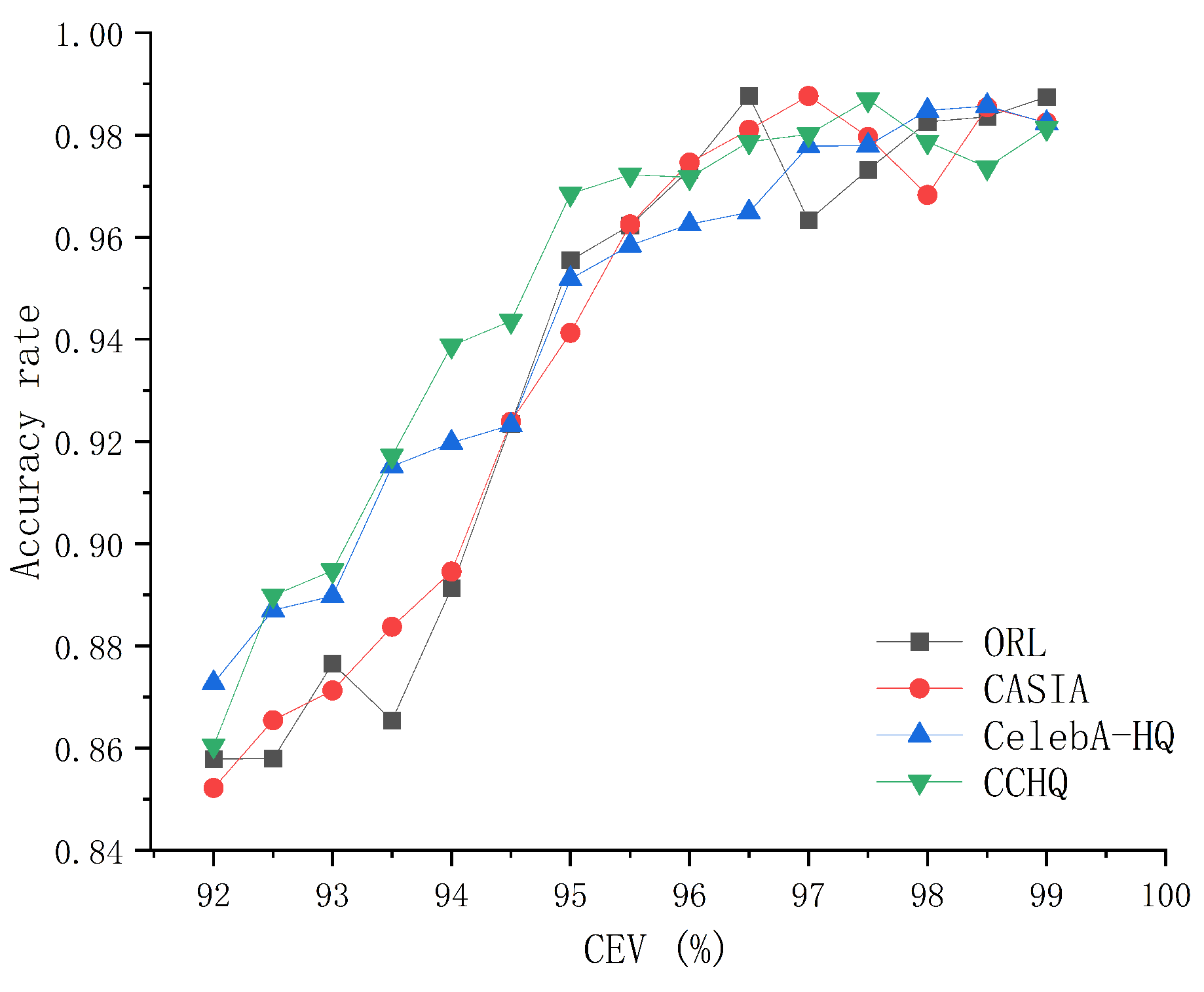

6.3.1. Feature Face Calculation Parameters

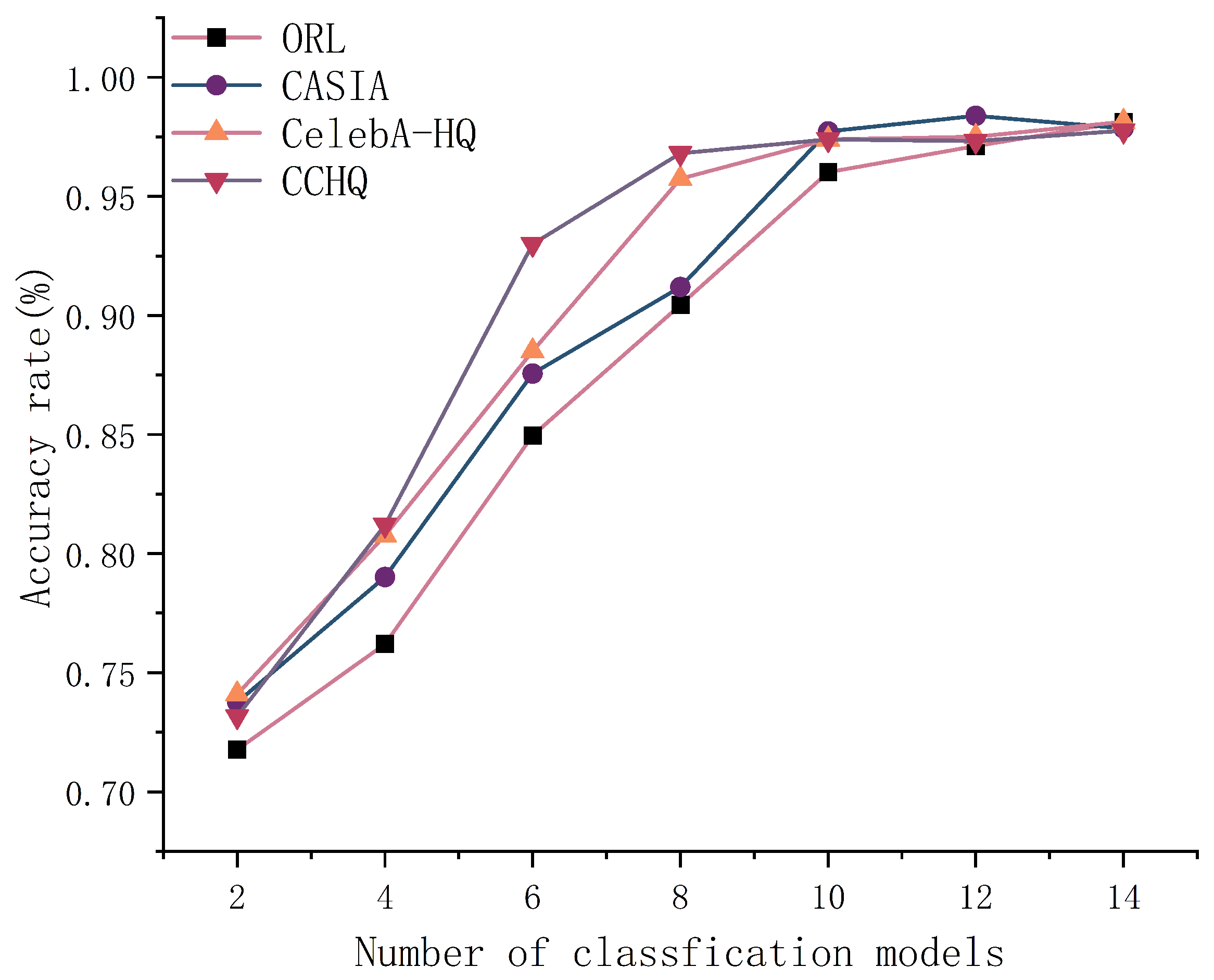

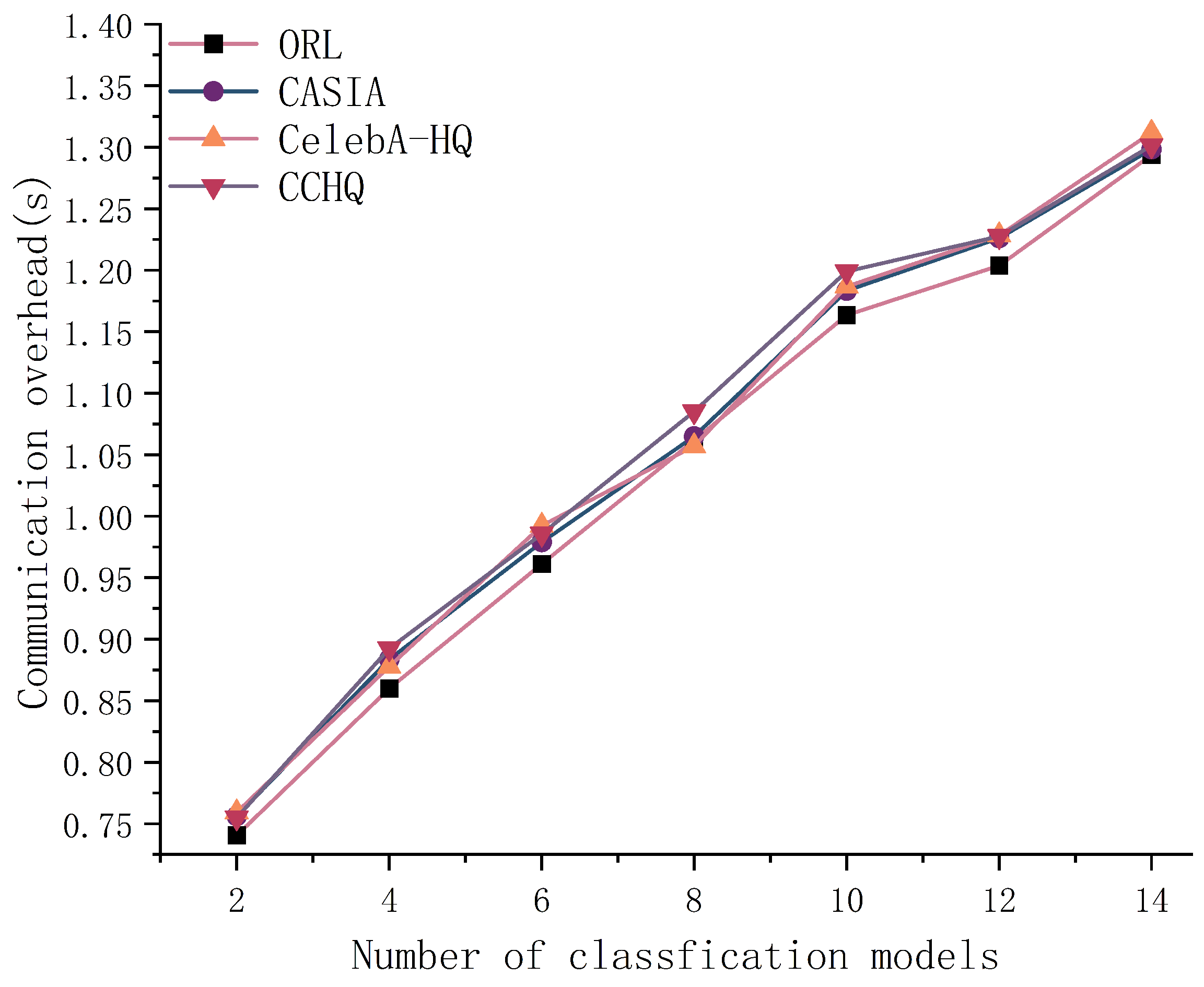

6.3.2. The Number of Classification Models

6.4. Cost Analysis

- (1)

- : The time taken to extract features and reduce them to feature vectors;

- (2)

- : The time taken to classify face features;

- (3)

- : The time taken to encrypt face features;

- (4)

- : The time taken to retrieve face features and perform similarity comparisons;

- (5)

- : The time taken to decrypt face features.

6.5. Comparison with Other Schemes

6.6. Comparison with Mainstream Homomorphic Encryption Schemes

7. Conclusions and Future Work

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wang, Z.; Wang, H.; Jin, S.; Zhang, W.; Hu, J.; Wang, Y.; Sun, P.; Yuan, W.; Liu, K.; Ren, K. Privacy-preserving adversarial facial features. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 17–24 June 2023; pp. 8212–8221. [Google Scholar]

- Nandakumar, K.; Jain, A.K. Biometric template protection: Bridging the performance gap between theory and practice. IEEE Signal Process. Mag. 2015, 32, 88–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, L.; Liang, K.; Pu, X.; Zhang, Y.; Leng, J.; Wu, T.; Wang, N.; Gao, X. Invertible image obfuscation for facial privacy protection via secure flow. In IEEE Transactions on Circuits and Systems for Video Technology; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Yuan, L.; Chen, W.; Pu, X.; Zhang, Y.; Li, H.; Zhang, Y.; Gao, X.; Ebrahimi, T. PRO-Face C: Privacy-Preserving Recognition of Obfuscated Face via Feature Compensation. IEEE Trans. Inf. Forensics Secur. 2024, 19, 4930–4944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Zhang, H.; Liang, S.; Dai, P.; Cao, X. Privacy-enhancing face obfuscation guided by semantic-aware attribution maps. IEEE Trans. Inf. Forensics Secur. 2023, 18, 3632–3646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shan, S.; Wenger, E.; Zhang, J.; Li, H.; Zheng, H.; Zhao, B.Y. Fawkes: Protecting Privacy against Unauthorized Deep Learning Models. In Proceedings of the 29th USENIX Security Symposium (USENIX Security 20), Virtual, 12–14 August 2020; pp. 1589–1604. [Google Scholar]

- Kimbrough, T.; Tian, P.; Liao, W.; Yu, W. Performance of GAN-Based Denoising and Restoration Techniques for Adversarial Face Images. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE/ACIS 21st International Conference on Software Engineering Research, Management and Applications (SERA), Orlando, FL, USA, 23–25 May 2023; pp. 335–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Li, X.; Yang, L.; Ma, J.; Li, H. ADDITION: Detecting Adversarial Examples With Image-Dependent Noise Reduction. IEEE Trans. Dependable Secur. Comput. 2024, 21, 1139–1154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maximov, M.; Elezi, I.; Leal-Taixé, L. Ciagan: Conditional identity anonymization generative adversarial networks. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Seattle, WA, USA, 13–19 June 2020; pp. 5447–5456. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, M.; Hua, G.; Li, S.; Feng, G. A Key-Driven Framework for Identity-Preserving Face Anonymization. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2409.03434. [Google Scholar]

- Yuan, Z.; You, Z.; Li, S.; Qian, Z.; Zhang, X.; Kot, A. On generating identifiable virtual faces. In Proceedings of the 30th ACM International Conference on Multimedia, New York, NY, USA, 10–14 October 2022; pp. 1465–1473. [Google Scholar]

- Im, J.H.; Jeon, S.Y.; Lee, M.K. Practical Privacy-Preserving Face Authentication for Smartphones Secure Against Malicious Clients. IEEE Trans. Inf. Forensics Secur. 2020, 15, 2386–2401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, H.; Wang, L. Efficient Privacy-Preserving Face Identification Protocol. IEEE Trans. Serv. Comput. 2023, 16, 2632–2641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauspieß, P.; Kolberg, J.; Drozdowski, P.; Rathgeb, C.; Busch, C. Privacy-Preserving Preselection for Protected Biometric Identification Using Public-Key Encryption With Keyword Search. IEEE Trans. Ind. Inform. 2023, 19, 6972–6981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, J.; Pei, Q.; Wang, Y.; Sun, W.; Liu, X. PRIVFACE: Fast privacy-preserving face authentication with revocable and reusable biometric credentials. IEEE Trans. Dependable Secur. Comput. 2021, 19, 3101–3112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, J.; Pei, Q.; Liu, X.; Sun, W. A practical privacy-preserving face authentication scheme with revocability and reusability. In Proceedings of the Algorithms and Architectures for Parallel Processing: 18th International Conference, ICA3PP 2018, Guangzhou, China, 15–17 November 2018; Proceedings, Part IV 18. Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2018; pp. 193–203. [Google Scholar]

- Proença, H. The uu-net: Reversible face de-identification for visual surveillance video footage. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. Video Technol. 2021, 32, 496–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.W.; Chen, L.J.; Yu, C.M.; Lu, C.S. Perceptual indistinguishability-net (pi-net): Facial image obfuscation with manipulable semantics. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Nashville, TN, USA, 20–25 June 2021; pp. 6478–6487. [Google Scholar]

- Hukkelås, H.; Mester, R.; Lindseth, F. Deepprivacy: A generative adversarial network for face anonymization. In International Symposium on Visual Computing; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2019; pp. 565–578. [Google Scholar]

- Kuang, Z.; Guo, Z.; Fang, J.; Yu, J.; Babaguchi, N.; Fan, J. Unnoticeable synthetic face replacement for image privacy protection. Neurocomputing 2021, 457, 322–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuang, Z.; Liu, H.; Yu, J.; Tian, A.; Wang, L.; Fan, J.; Babaguchi, N. Effective de-identification generative adversarial network for face anonymization. In Proceedings of the 29th ACM International Conference on Multimedia, Virtual, 20–24 October 2021; pp. 3182–3191. [Google Scholar]

- Dietlmeier, J.; Hu, F.; Ryan, F.; O’Connor, N.E.; McGuinness, K. Improving person re-identification with temporal constraints. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Winter Conference on Applications of Computer Vision, Waikoloa, HI, USA, 3–8 January 2022; pp. 540–549. [Google Scholar]

- Ye, M.; Shen, W.; Zhang, J.; Yang, Y.; Du, B. Securereid: Privacy-preserving anonymization for person re-identification. IEEE Trans. Inf. Forensics Secur. 2024, 19, 2840–2853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erkin, Z.; Franz, M.; Guajardo, J.; Katzenbeisser, S.; Lagendijk, I.; Toft, T. Privacy-preserving face recognition. In Proceedings of the Privacy Enhancing Technologies: 9th International Symposium, PETS 2009, Seattle, WA, USA, 5–7 August 2009; Proceedings 9. Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2009; pp. 235–253. [Google Scholar]

- Sadeghi, A.R.; Schneider, T.; Wehrenberg, I. Efficient privacy-preserving face recognition. In International Conference on Information Security and Cryptology; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2009; pp. 229–244. [Google Scholar]

- Xiang, C.; Tang, C.; Cai, Y.; Xu, Q. Privacy-preserving face recognition with outsourced computation. Soft Comput. 2016, 20, 3735–3744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Nakachi, T. A privacy-preserving learning framework for face recognition in edge and cloud networks. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 136056–136070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Yang, J.; Zhao, W.; Zhang, Y.; Li, J.; Mu, C. Face Image Publication Based on Differential Privacy. Wirel. Commun. Mob. Comput. 2021, 2021, 8871987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dwork, C. Differential privacy: A survey of results. In International Conference on Theory and Applications of Models of Computation; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2008; pp. 1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Mao, Y.; Yi, S.; Li, Q.; Feng, J.; Xu, F.; Zhong, S. A privacy-preserving deep learning approach for face recognition with edge computing. In Proceedings of the USENIX Workshop Hot Topics Edge Comput. (HotEdge ’18), Boston, MA, USA, 10 July 2018; USENIX Association: Berkeley, CA, USA, 2018; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.; Wang, Y.; Li, D. Privacy-preserving lightweight face recognition. Neurocomputing 2019, 363, 212–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Hu, H.; Xiang, H.; Yang, C.; Lyu, L.; Zhang, X. Clustering-based Efficient Privacy-preserving Face Recognition Scheme without Compromising Accuracy. ACM Trans. Sens. Netw. (TOSN) 2021, 17, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Z.; Liu, Z. Ensuring privacy in face recognition: A survey on data generation, inference and storage. Discov. Appl. Sci. 2025, 7, 441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, S.; Zhang, L.; Xiong, P. PriFace: A privacy-preserving face recognition framework under untrusted server. J. Ambient. Intell. Humaniz. Comput. 2023, 14, 2967–2979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Zhan, Y.; Zhang, Z. Cryptanalysis of a symmetric fully homomorphic encryption scheme. IEEE Trans. Inf. Forensics Secur. 2018, 13, 1460–1467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahdikhani, H.; Lu, R.; Zheng, Y.; Shao, J.; Ghorbani, A.A. Achieving O (log3n) communication-efficient privacy-preserving range query in fog-based IoT. IEEE Internet Things J. 2020, 7, 5220–5232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cozza, F.; Guarino, A.; Isernia, F.; Malandrino, D.; Rapuano, A.; Schiavone, R.; Zaccagnino, R. Hybrid and lightweight detection of third party tracking: Design, implementation, and evaluation. In Computer Networks; Elsevier BV: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Guarino, A.; Malandrino, D.; Zaccagnino, R. An automatic mechanism to provide privacy awareness and control over unwittingly dissemination of online private information. Comput. Netw. 2022, 202, 108614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, J.; Vercauteren, F. Somewhat practical fully homomorphic encryption. Iacr Cryptol. Eprint Arch. 2012, 2012, 144. [Google Scholar]

- Brakerski, Z.; Gentry, C.; Vaikuntanathan, V. (Leveled) fully homomorphic encryption without bootstrapping. ACM Trans. Comput. Theory (TOCT) 2014, 6, 1–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheon, J.; Kim, A.; Kim, M.; Song, Y. Homomorphic encryption for arithmetic of approximate numbers. In International Conference on the Theory and Application of Cryptology and Information Security; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 409–437. [Google Scholar]

- Serengil, S.; Ozpinar, A. CipherFace: A Fully Homomorphic Encryption-Driven Framework for Secure Cloud-Based Facial Recognition. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2502.18514. [Google Scholar]

| Approach Category | Key Features | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Anonymization Methods [9,17,18,19,20,21,22,23] | Employing conventional techniques such as blurring, pixelation, and noise addition, or utilizing learnable models based on face swapping. | The reversible framework supports data reuse and is adaptable to multiple scenarios. | Some methods (such as the ISED architecture) require the allocation of exclusive keys for each identity, which poses key management challenges in large-scale systems. |

| Encryption Methods [24,25,26,27,28] | Based on mathematical algorithms (such as secure multi-party computation, SMPC), the facial data/attributes are encoded to generate ciphertext. | The privacy protection is highly effective, completely preventing the leakage of original data at the mathematical level. | The computational complexity is high, and the processes of encryption/decryption and ciphertext matching take a long time, making it difficult to adapt to real-time scenarios. |

| Differential Privacy Methods [29,30,31,32] | Controllable noise (such as Laplace and Gaussian noise) is added during the facial feature extraction/model training stage, and the noise intensity is controlled through a “privacy budget”. | Low computational cost, lightweight noise generation and addition process, suitable for resource-constrained devices such as mobile terminals. | There exists a “privacy–accuracy trade-off” contradiction: if is too small (strong privacy), the noise will be too large, leading to an increase in the False Rejection Rate; if is too large (high accuracy), the strength of privacy protection will be insufficient. |

| Notation | Descriptions |

|---|---|

| grayscale face image dataset | |

| matrix | |

| the mean vector of the matrix | |

| the covariance matrix | |

| feature face vector | |

| face images of user U | |

| encrypted face feature ciphertext | |

| face images of user U to be authenticated | |

| ) | encrypted face feature ciphertext of user U to be authenticated |

| the similarity |

| Name | Individuals | Total Face Images | Resolution | Image Type |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ORL | 40 | 400 | 92 ∗ 112 | Gray image |

| CASIA | 500 | 2500 | 256 ∗ 256 | Color image |

| CelebA-HQ | 200 | 2000 | 256 ∗ 256 | Color image |

| Database | Precision | Recall | Cost (ms) |

|---|---|---|---|

| ORL | 0.98531 | 1.00 | 1004.246 |

| CASIA | 0.99673 | 1.00 | 1257.917 |

| CelebA | 0.97540 | 1.00 | 1219.514 |

| Symbol | The Client | The Server |

|---|---|---|

| 235.245 | - | |

| 0.032 | - | |

| 264.834 | - | |

| - | 596.234 | |

| 123.983 | 1.00 |

| Scheme | The User | The Client | The Server | Total Cost (ms) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| [16] | + | - | + + | 2281 |

| [12] | - | ++ | 1299.73 | |

| Ours | - | +++ | 1220.328 |

| Method | Precision | Recall | F1-Score |

|---|---|---|---|

| Eigenfaces | 0.96250 | 1.00 | 0.97468 |

| PRIFACE | 0.93330 | 1.00 | 0.89788 |

| FFCM | 0.98582 | 1.00 | 0.98548 |

| Scheme | Ciphertext Structure | Supported Operations | Complexity | Suitability for Face Recognition |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| BFV [39] | Polynomial modulus (RNS) | Exact addition/ multiplication | High | Heavyweight; high latency for vector operations |

| BGV [40] | Polynomial modulus with modulus switching | Exact addition/multiplication | High | Efficient but still computationally expensive for real-time authentication |

| CKKS [41] | Polynomial modulus with approximate arithmetic | Approximate addition/multiplication | High | Good for neural inference, but expensive for cosine similarity |

| Proposed SHE | Integer modulus | Exact addition/multiplication | Low | Lightweight and well-suited for 1D feature vector matching |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Zhou, L.; Li, Q.; Zhu, H.; Zhou, Y.; Wu, H. Efficient Privacy-Preserving Face Recognition Based on Feature Encoding and Symmetric Homomorphic Encryption. Entropy 2026, 28, 5. https://doi.org/10.3390/e28010005

Zhou L, Li Q, Zhu H, Zhou Y, Wu H. Efficient Privacy-Preserving Face Recognition Based on Feature Encoding and Symmetric Homomorphic Encryption. Entropy. 2026; 28(1):5. https://doi.org/10.3390/e28010005

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhou, Limengnan, Qinshi Li, Hui Zhu, Yanxia Zhou, and Hanzhou Wu. 2026. "Efficient Privacy-Preserving Face Recognition Based on Feature Encoding and Symmetric Homomorphic Encryption" Entropy 28, no. 1: 5. https://doi.org/10.3390/e28010005

APA StyleZhou, L., Li, Q., Zhu, H., Zhou, Y., & Wu, H. (2026). Efficient Privacy-Preserving Face Recognition Based on Feature Encoding and Symmetric Homomorphic Encryption. Entropy, 28(1), 5. https://doi.org/10.3390/e28010005