Ions at Helium Interfaces: A Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Trapping of Ions at Helium Interfaces

2.1. Ions at the Liquid–Vapor Helium Interface

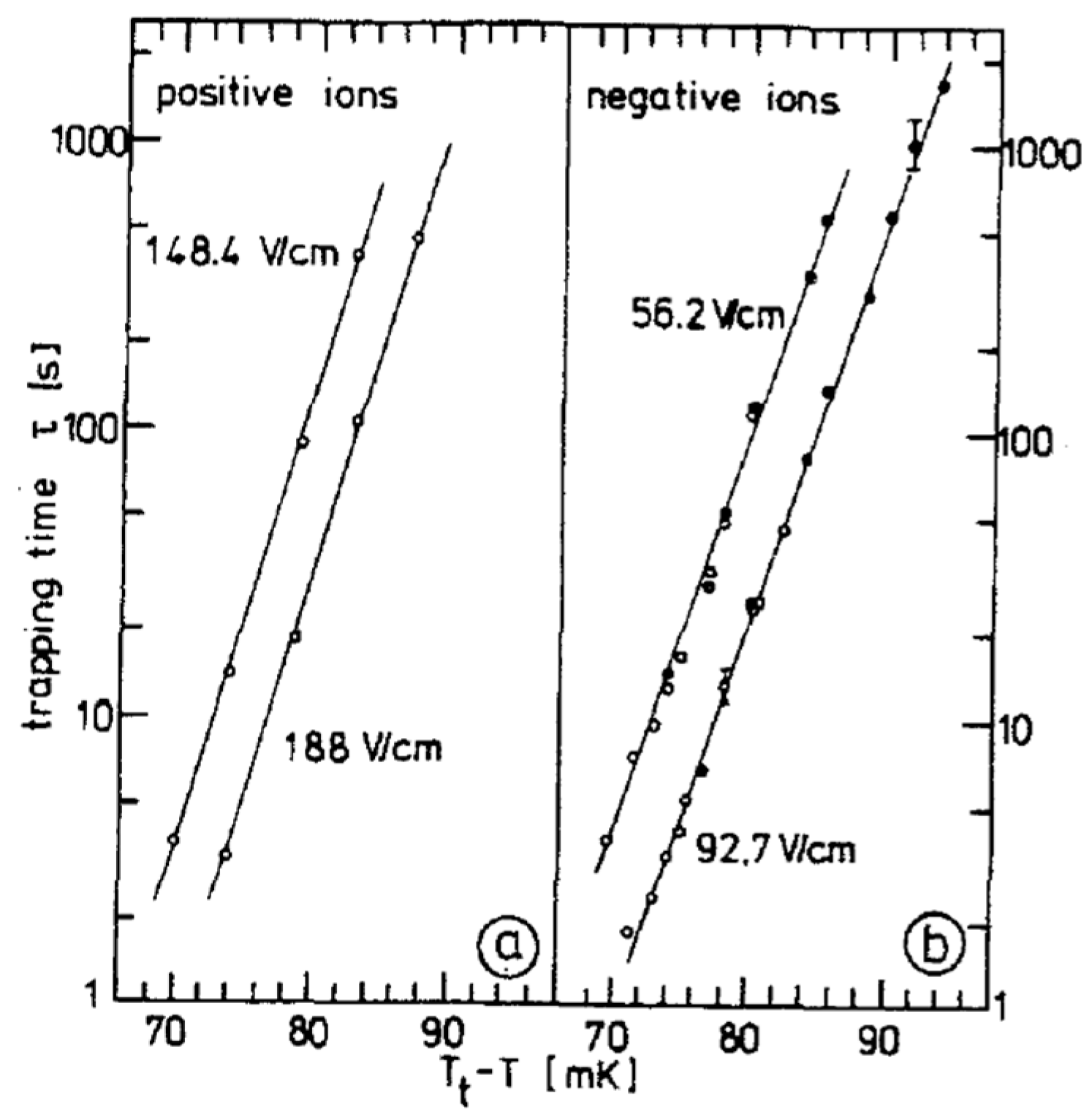

2.2. Ions at the Liquid–Liquid Interface of Phase-Separated 3He-4He Mixtures

2.3. Ions at the Liquid–Solid Interface of 4He

3. Ion Pools Below the Surface of Liquid Helium

4. The Electro-Hydrodynamic Instability of Charged Helium Interfaces

4.1. Ion-Induced Ripplon Softening

4.2. The Dimple Lattice

4.3. Beyond the Instability Point

4.4. Taylor Cone and Electrospraying

5. Conclusions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Fetter, A.L. The Physics of Liquid and Solid Helium; Bennemann, K.H., Ketterson, J.B., Eds.; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 1974; p. 207. [Google Scholar]

- Borghesani, A.F. Ions and Electrons in Liquid Helium; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Atkins, K.R. Ions in liquid helium. Phys. Rev. 1959, 116, 1339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yarmchuk, E.J.; Packard, R.E. Photographic studies of quantized vortex lines. J. Low Temp. Phys. 1982, 46, 479–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Classen, J.; Mohazzab, M.; Su, C.-K.; Maris, H.J. Electrons and cavitation in liquid helium. Phys. Rev. 1998, 57, 3000–3010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donnelly, R.J.; Swanson, C.E. Quantum turbulence. J. Fluid Mech. 1986, 173, 387–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barenghi, C.F.; Skrbek, L.; Sreenivasan, K.R. Quantum Turbulence; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- McClintock, P.V.E. Ions in superfluid helium. Phys. B+C 1984, 127, 300–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McClintock, P.V.E.; Bowley, R.M. Vortex Creation in Superfluid Helium-4. In Excitations in Two-Dimensional and Three-Dimensional Quantum Fluids; NATO ASI Series; Wyatt, A.F.G., Lauter, H.J., Eds.; Springer: Boston, MA, USA, 1991; Volume 257, pp. 567–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McClintock, P.V.E.; Bowley, R.M. The Landau critical velocity. In Progress in Low Temperature Physics; Halperin, W.B., Ed.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1995; Volume 14, pp. 1–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skrbek, L.; Sergeev, Y.A. Critical velocities in flows of superfluid 4He. Phys. Fluids 2025, 37, 31305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cole, M.W. Electronic surface states of liquid helium. Rev. Mod. Phys. 1974, 46, 451–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grimes, C.C. Electrons in surface states on liquid helium. Surf. Sci. 1978, 73, 379–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shikin, V. Theory of localized electron states on the liquid helium surface. Rev. Mod. Phys. 1978, 73, 396–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrei, E.Y. (Ed.) Two-Dimensional Electron Systems on Helium and Other Cryogenic Substrates; Kluwer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Kono, K. Electrons on the surface of superfluid 3He. J. Low Temp. Phys. 2010, 158, 288–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, L.; Reif, F. Mobilities of He Ions in Liquid Helium. Phys. Rev. 1958, 110, 279–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Careri, G.; Fasoli, U.; Gaeta, F.S. Experimental behaviour of ionic structures in liquid helium II. Nuovo Cim. 1960, 15, 774–783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruschi, L.; Maraviglia, B.; Moss, F.E. Measurement of a Barrier for the Extraction of Excess Electrons from Liquid Helium. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1966, 17, 682–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoepe, W.; Rayfield, G.W. Thermal Emission of Electrons from Liquid Helium. Z. Naturforschung A 1971, 26, 1392–1397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoepe, W.; Rayfield, G.W. Tunneling from electronic bubble states in liquid helium through the liquid-vapor interface. Phys. Rev. A 1973, 7, 469–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cole, M.W.; Klein, J.R. Tunneling from electron bubbles beneath the surface of liquid helium. J. Low Temp. Phys. 1979, 36, 331–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ancilotto, F.; Toigo, F. Properties of an electron bubble approaching the surface of liquid helium. Phys. Rev. B 1994, 50, 12820–12830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boyle, F.P.; Dahm, A.J. Extraction of charged droplets from charged surfaces of liquid dielectrics. J. Low Temp. Phys. 1976, 23, 477–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leiderer, P. Optical Experiments in 3He-4He mixtures near the tricritical point. In Quantum Fluids and Solids; Trickey, S.B., Adams, E.D., Dufty, J.W., Eds.; Plenum Press: New York, NY, USA, 1977; p. 351. [Google Scholar]

- Leiderer, P.; Poisel, H.; Wanner, M. Interfacial tension near the tricritical point in 3He-4He mixtures. J. Low Temp. Phys. 1977, 28, 167–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuchnir, M.; Roach, P.R.; Ketterson, J.B. Negative ion transmission through the 3He-4He phase boundary. J. Low Temp. Phys. 1979, 3, 183–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wanner, M.; Leiderer, P.; Reverchon, T. Ions at the Critical Interface of 3He-4He Mixtures. Phys. Lett. A 1978, 68, 226–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Leiderer, P.; Wanner, M.; Schoepe, W. Ions at the critical interface of 3He-4He mixtures. J. Phys. Colloq. 1978, 39, C6-1328–C6-1333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Crandall, R.S.; Williams, R. Deformation of the surface of liquid helium by electrons. Phys. Lett. 1971, 36, 35–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golov, A.I.; Mezhov-Deglin, L.P. IR absorption spectrum of excess electrons in solid helium. Physica B 1994, 194–196, 951–952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savignac, D.; Leiderer, P. Charge-Induced Instability of the 4He Solid-Superfluid Interface. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1982, 49, 1869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bodensohn, J.; Nicolai, K.; Leiderer, P. The growth of atomically rough4He crystals. Z. Phys. B Condens. Matter 1986, 64, 55–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poitrenaud, J.; Williams, F.I.B. Precise Measurement of Effective Mass of Positive and Negative Charge Carriers in Liquid Helium II. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1972, 29, 1230–1232, Erratum in Phys. Rev. Lett. 1974, 32, 1213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ott-Rowland, M.L.; Kotsubo, V.; Theobald, J.; Williams, G.A. Two-dimensional plasma resonances in positive ions under the surface of liquid helium. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1982, 49, 1708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ikezi, H. Nonlinear plasmon resonance of a charged-particle system on a surface of liquid helium. Phys. Rev. B 1983, 27, 585–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skrbek, L. Ion Pools Underneath the Surface of Superfluid He: A Playground of Classical Two-Dimensional Physics. J. Low Temp. Phys. 2023, 212, 232–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barenghi, C.F.; Mellor, C.J.; Muirhead, C.M.; Vinen, W.F. Experiments on ions trapped below the surface of superfluid 4He. J. Phys. C Solid State Phys. 1986, 19, 1135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwarz, K.W. Charge-Carrier Mobilities in Liquid Helium at the Vapor Pressure. Phys. Rev. A 1972, 6, 837–844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hendry, P.C.; McClintock, P.V.E. Continuous flow apparatus for preparing isotopically pure 4He. Cryogenics 1987, 27, 131–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grimes, C.C.; Adams, G. Evidence for a Liquid-to-Crystal Phase Transition in a Classical, Two-Dimensional Sheet of Electrons. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1979, 42, 795–798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shikin, V.B. Excitation of capillary waves in helium by a Wigner lattice of surface electrons. JETP Lett. 1974, 19, 335–336. [Google Scholar]

- Mellor, C.J.; Vinen, W.F. Experimental observation of crystallization and ripplon generation in a two-dimensional pool of helium ions. Surf. Sci. 1990, 229, 368–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elliott, P.L.; Pakes, C.I.; Skrbek, L.; Vinen, W.F. Capillary-wave crystallography: Crystallization of two-dimensional sheets of He+ ions. Phys. Rev. B 2002, 61, 1396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elliott, P.L.; Pakes, C.I.; Skrbek, L.; Vinen, W.F. Damage and annealing in two-dimensional Coulomb crystals. Czech J. Phys. B 1996, 46, 333–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elliott, P.L.; Pakes, C.I.; Skrbek, L.; Vinen, W.F. Modes of transverse response in a two-dimensional Coulomb system above the melting temperature. Phys. B 1998, 249–251, 664–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelson, D.R.; Halperin, B.I. Dislocation-mediated melting in two dimensions. Phys. Rev. B 1979, 19, 2457–2484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, A.P. Melting and the vector Coulomb gas in two dimensions. Phys. Rev. B 1979, 19, 1855–1866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kokko, J.; Paalanen, M.A.; Schoepe, W.; Takano, Y. Positive ion mobility in normal and superfluid 3He. J. Low Temp. Phys. 1978, 33, 69–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Shiino, T.; Mukuda, H.; Kono, K.; Vinen, W.F. First mobility measurement of ions trapped below the normal and superfluid 3He surface. J. Low Temp. Phys. 2002, 126, 493–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ikegami, H.; Chung, S.B.; Kono, K. Mobility of ions trapped below a free surface of superfluid 3He. J. Phys. Soc. Jpn. 2013, 82, 124607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ikegami, H.; Kono, K. Review: Observation of Majorana bound states at a free surface of 3He-B. J. Low Temp. Phys. 2019, 195, 343–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ikegami, H.; Tsutsumi, Y.; Kono, K. Chiral Symmetry Breaking in Superfluid 3He-A. Science 2013, 341, 59–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frenkel, Y.I. On the Tonks theory of liquid surface rupture by a uniform electric field in vacuum. Zh. Eksp. Teor. Fiz. 1936, 6, 347–350. [Google Scholar]

- Tonks, L. A Theory of Liquid Surface Rupture by a Uniform Electric Field. Phys. Rev. 1935, 48, 562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gor’kov, L.P.; Chernikova, D.M. Concerning the structure of a charged surface of liquid helium. JETP Lett. 1974, 18, 68. [Google Scholar]

- Rybalko, S.A.; Kovdrya, Y.Z. Singularities of electromagnetic field energy absorption by a system of electrons on a liquid helium surface. Sov. J. Low Temp. Phys. 1975, 1, 498–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volodin, A.P.; Khaikin, M.S.; Edel’man, V.S. Development of instabibility and bubblon production on a charged surface of liquid helium. JETP Lett. 1977, 26, 543. [Google Scholar]

- Mima, K.; Ikezi, H. Propagation of nonlinear waves on an electron-charged surface of liquid helium. Phys Rev. B 1978, 17, 3567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wanner, M.; Leiderer, P. Charge-Induced Ripplon Softening and Dimple Crystallization at the Interface of 3He-4He Mixtures. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1979, 42, 315–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leiderer, P. Charged interface of 3He-4He mixtures. Softening of interfacial waves. Phys. Rev. 1979, 20, 4511–4517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ikezi, H. Macroscopic Electron Lattice on the Surface of Liquid Helium. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1979, 42, 1688–1690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leiderer, P.; Wanner, M. Structure of the dimple lattice. Phys. Lett. A 1979, 73, 189–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebner, W.; Leiderer, P. Development of the dimple instability on liquid 4He. Phys. Lett. A 1980, 80, 277–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leiderer, P.; Ebner, W.; Shikin, V.B. Macroscopic electron dimples on the surface of liquid helium. Surf. Sci. 1982, 113, 405–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giannetta, R.W.; Ikezi, H. Nonlinear Deformation of the Electron-Charged Surface of Liquid 4He. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1981, 47, 849–852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leiderer, P.; Ebner, W.; Shikin, V.B. Multielectron dimples on the surface of liquid 4He. Phys. B+C 1981, 107, 217–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ikezi, H.; Giannetta, R.W.; Platzman, P.M. Nonlinear equilibria of the electron-charged surface of liquid helium. Phys. Rev. 1982, 25, 4488–4494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melnikov, V.I.; Meshkov, S.V. Hexagonal restructuring of the charged surface of liquid helium. Sov. Phys. JETP 1982, 55, 1099. [Google Scholar]

- Poesio, P.; Cominardi, G.; Lezzi, A.M.; Mauri, R.; Beretta, G.P. Effects of quenching rate and viscosity on spinodal decomposition. Phys. Rev. E 2006, 74, 11507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andreev, A.F.; Parshin, A.Y. Equilibrium shape and oscillations of the surface of quantum crystals. Sov. Phys. JETP 1978, 48, 763. [Google Scholar]

- Keshishev, K.O.; Parshin, A.Y.; Babkin, A.V. Experimental detection of crystallization waves in 4He. JETP Lett. 1979, 30, 56. [Google Scholar]

- Albrecht, U.; Leiderer, P. Multielectron Bubbles in Liquid Helium. Europhys. Lett. 1987, 3, 705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, N.; Rath, P.K.; Xie, Z.; Huang, Y.; Ghosh, A. Multielectron Bubbles in Liquid Helium. J. Low Temp. Phys. 2020, 201, 658–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rath, P.K.; Pradhan, D.K.; Leiderer, P.; Ghosh, A. Kinetics of electrohydrodynamic instability of a charged liquid helium surface. Phys. Rev. B 2024, 110, 94510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volodin, A.P.; Khaikin, M.S. Ion ‘‘geysers’’ on the surface of superfluid helium. JETP Lett. 1979, 30, 572. [Google Scholar]

- Moroshkin, P.; Leiderer, P.; Möller, T.B.; Kono, K. Taylor cone and electrospraying at a free surface of superfluid helium charged from below. Phys. Rev. E 2017, 95, 53110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, G.I.; McEwan, A.D. The stability of a horizontal fluid interface in a vertical electric field. J. Fluid Mech. 1965, 22, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Leiderer, P. Ions at Helium Interfaces: A Review. Entropy 2026, 28, 109. https://doi.org/10.3390/e28010109

Leiderer P. Ions at Helium Interfaces: A Review. Entropy. 2026; 28(1):109. https://doi.org/10.3390/e28010109

Chicago/Turabian StyleLeiderer, Paul. 2026. "Ions at Helium Interfaces: A Review" Entropy 28, no. 1: 109. https://doi.org/10.3390/e28010109

APA StyleLeiderer, P. (2026). Ions at Helium Interfaces: A Review. Entropy, 28(1), 109. https://doi.org/10.3390/e28010109