Optimal Transfer of Entanglement in Oscillator Chains in Non-Markovian Open Systems

Abstract

1. Introduction

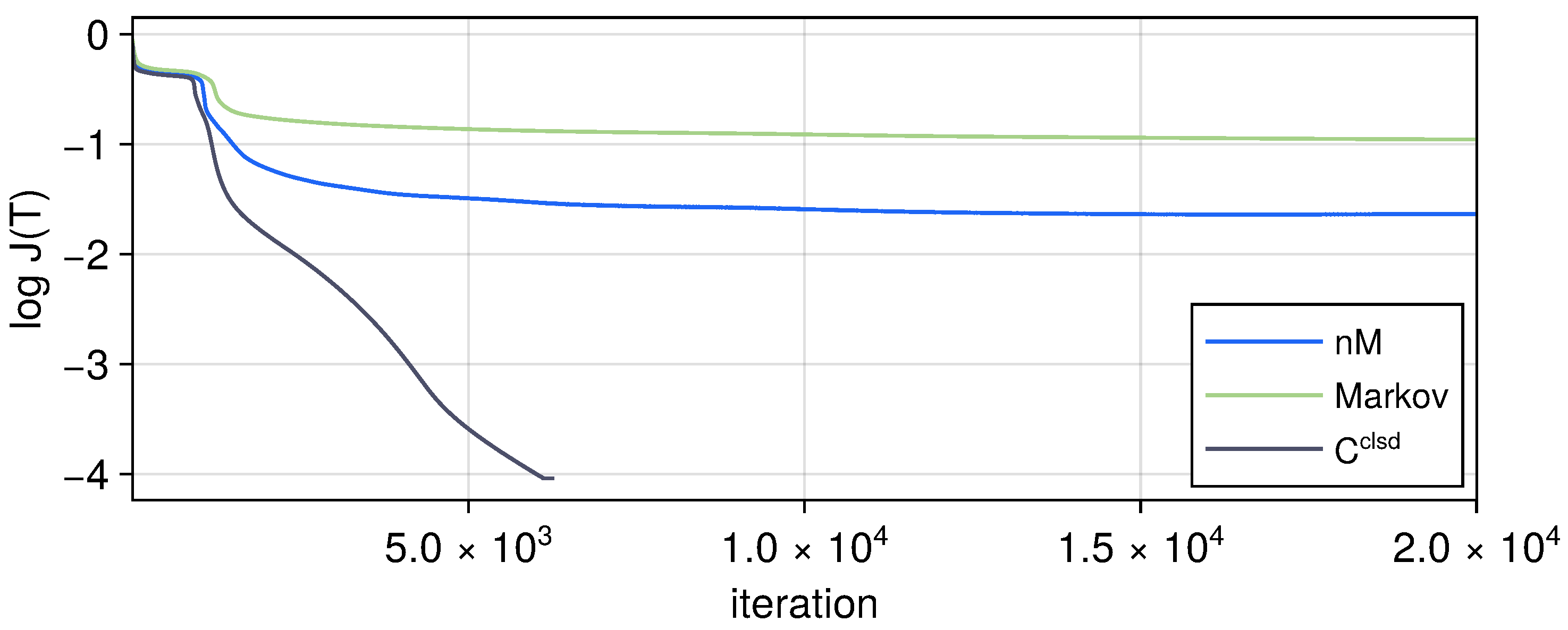

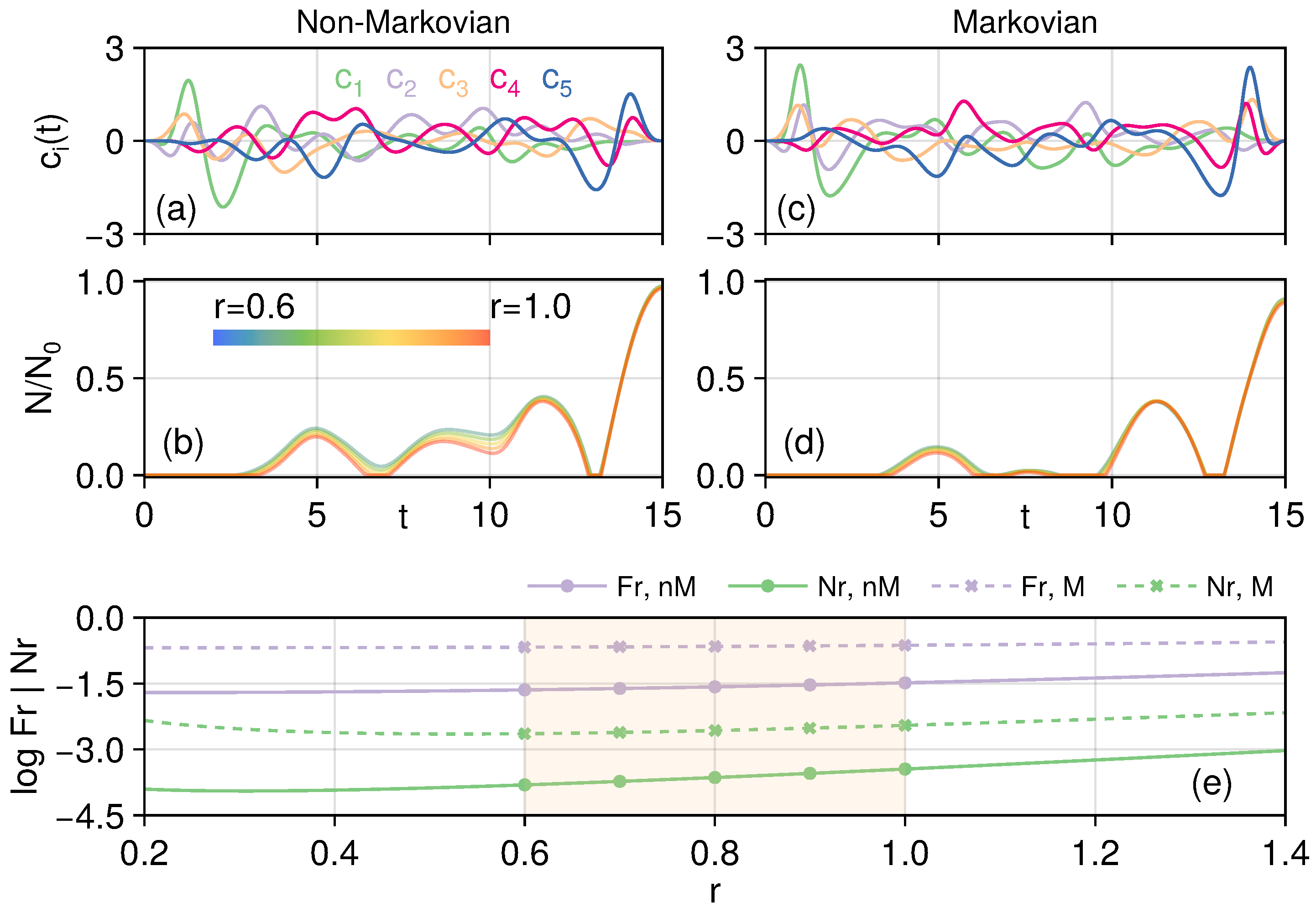

2. Optimal Transfer of Entangled States in Oscillator Chains: Closed-System Setup

3. Krotov’s Method in Open Quantum Systems

4. Conclusions and Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Homogeneous Linear Differential Equation for the Open-System CM

Appendix B. Control Field Update in Non-Markovian Open Systems: O-Operator Contribution to the Update Equation

References

- Horodecki, R.; Horodecki, P.; Horodecki, M.; Horodecki, K. Quantum entanglement. Rev. Mod. Phys. 2009, 81, 865–942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nielsen, M.A.; Chuang, I.L. Quantum Computation and Quantum Information; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Zeilinger, A. Quantum teleportation. Sci. Am. 2000, 282, 50–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pirandola, S.; Eisert, J.; Weedbrook, C.; Furusawa, A.; Braunstein, S.L. Advances in quantum teleportation. Nat. Photonics 2015, 9, 641–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekert, A.K. Quantum cryptography based on Bell’s theorem. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1991, 67, 661–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grover, L.K. A fast quantum mechanical algorithm for database search. In Proceedings of the Twenty-Eighth Annual ACM Symposium on Theory of Computing, Philadelphia, PA, USA, 22–24 May 1996; pp. 212–219. [Google Scholar]

- Degen, C.L.; Reinhard, F.; Cappellaro, P. Quantum sensing. Rev. Mod. Phys. 2017, 89, 035002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeMille, D.; Hutzler, N.R.; Rey, A.M.; Zelevinsky, T. Quantum sensing and metrology for fundamental physics with molecules. Nat. Phys. 2024, 20, 741–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lecamwasam, R.; Iakovleva, T.; Twamley, J. Quantum metrology with linear Lie algebra parameterizations. Phys. Rev. Res. 2024, 6, 043137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Filho, R.L.d.M.; Agarwal, G.S.; Davidovich, L. Quantum advantage of time-reversed ancilla-based metrology of absorption parameters. Phys. Rev. Res. 2024, 6, 013034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, G.S.; Davidovich, L. Quantifying quantum-amplified metrology via Fisher information. Phys. Rev. Res. 2022, 4, L012014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiss, T.; Roda-Llordes, M.; Torrontegui, E.; Aspelmeyer, M.; Romero-Isart, O. Large Quantum Delocalization of a Levitated Nanoparticle Using Optimal Control: Applications for Force Sensing and Entangling via Weak Forces. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2021, 127, 023601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giovannetti, V.; Lloyd, S.; Maccone, L. Quantum-enhanced measurements: Beating the standard quantum limit. Science 2004, 306, 1330–1336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Demkowicz-Dobrzański, R.; Maccone, L. Using Entanglement Against Noise in Quantum Metrology. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2014, 113, 250801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Y.; Yadin, B.; Xu, Z.P. Quantum-Enhanced Metrology with Network States. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2024, 132, 210801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, Y.; Agrawal, A.R.; Pluchar, C.M.; Brady, A.J.; Liu, Z.; Zhuang, Q.; Wilson, D.J.; Zhang, Z. Entanglement-enhanced optomechanical sensing. Nat. Photonics 2023, 17, 470–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dooley, S.; Pappalardi, S.; Goold, J. Entanglement enhanced metrology with quantum many-body scars. Phys. Rev. B 2023, 107, 035123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Zhuang, M.; Lee, C. Entanglement-enhanced quantum metrology: From standard quantum limit to Heisenberg limit. Appl. Phys. Rev. 2024, 11, 031302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, H.; Lim, Y.; Jiang, L.; Jeong, H.; Oh, C. Quantum metrological power of continuous-variable quantum networks. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2022, 128, 180503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fadel, M.; Roux, N.; Gessner, M. Quantum metrology with a continuous-variable system. Rep. Prog. Phys. 2025, 88, 106001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, L.; He, X.; You, C.; Lv, C.; Li, B.; Lloyd, S.; Wang, X. Exponential enhancement of quantum metrology using continuous variables. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2004.01216. [Google Scholar]

- Dowling, J.P. Quantum optical metrology–the lowdown on high-N00N states. Contemp. Phys. 2008, 49, 125–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dowling, J.P.; Seshadreesan, K.P. Quantum optical technologies for metrology, sensing, and imaging. J. Light. Technol. 2015, 33, 2359–2370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huver, S.D.; Wildfeuer, C.F.; Dowling, J.P. Entangled Fock states for robust quantum optical metrology, imaging, and sensing. Phys. Rev. A-Mol. Opt. Phys. 2008, 78, 063828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aspelmeyer, M.; Kippenberg, T.J.; Marquardt, F. Cavity optomechanics. Rev. Mod. Phys. 2014, 86, 1391–1452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.B.; Ou, L.; Lei, Y.; Liu, Y.C. Cavity optomechanical sensing. Nanophotonics 2021, 10, 2799–2832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zobenica, Ž.; van der Heijden, R.W.; Petruzzella, M.; Pagliano, F.; Leijssen, R.; Xia, T.; Midolo, L.; Cotrufo, M.; Cho, Y.; Van Otten, F.W.; et al. Integrated nano-opto-electro-mechanical sensor for spectrometry and nanometrology. Nat. Commun. 2017, 8, 2216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodwin, D.L.; Singh, P.; Foroozandeh, M. Adaptive optimal control of entangled qubits. Sci. Adv. 2022, 8, eabq4244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omanakuttan, S.; Mitra, A.; Meier, E.J.; Martin, M.J.; Deutsch, I.H. Qudit Entanglers Using Quantum Optimal Control. PRX Quantum 2023, 4, 040333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palaiodimopoulos, N.E.; Brouzos, I.; Diakonos, F.K.; Theocharis, G. Fast and robust quantum state transfer via a topological chain. Phys. Rev. A 2021, 103, 052409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.H.; Zeng, Y.; Tan, Q.S.; Dong, D.; Nori, F.; Liao, J.Q. Optimal control of linear Gaussian quantum systems via quantum learning control. Phys. Rev. A 2024, 109, 063508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duncan, C.W.; Poggi, P.M.; Bukov, M.; Zinner, N.T.; Campbell, S. Taming Quantum Systems: A Tutorial for Using Shortcuts-To-Adiabaticity, Quantum Optimal Control, and Reinforcement Learning. PRX Quantum 2025, 6, 040201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Y.J.; Dai, H.N.; Yuan, Z.S.; Deng, Y.; Li, X.; Chen, Y.A.; Pan, J.W. Bayesian learning for optimal control of quantum many-body states in optical lattices. Phys. Rev. A 2022, 106, 013316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konnov, A.; Krotov, V.F. On global methods for the successive improvement of control processes. Avtomatika i Telemekhanika 1999, 60, 1427–1436. [Google Scholar]

- Reich, D.M.; Ndong, M.; Koch, C.P. Monotonically convergent optimization in quantum control using Krotov’s method. J. Chem. Phys. 2012, 136, 104103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tannor, D.J.; Kazakov, V.; Orlov, V. Control of Photochemical Branching: Novel Procedures for Finding Optimal Pulses and Global Upper Bounds. In Time-Dependent Quantum Molecular Dynamics; Springer: Boston, MA, USA, 1992; pp. 347–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jäger, G.; Reich, D.M.; Goerz, M.H.; Koch, C.P.; Hohenester, U. Optimal quantum control of Bose-Einstein condensates in magnetic microtraps: Comparison of gradient-ascent-pulse-engineering and Krotov optimization schemes. Phys. Rev. A 2014, 90, 033628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goerz, M.H.; Basilewitsch, D.; Gago-Encinas, F.; Krauss, M.G.; Horn, K.P.; Reich, D.M.; Koch, C.P. Krotov: A Python implementation of Krotov’s method for quantum optimal control. SciPost Phys. 2019, 7, 080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breuer, H.P.; Petruccione, F. Theory of Open Quantum Systems; Oxford University: New York, NY, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Rivas, A.; Huelga, S.F. Open Quantum Systems; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2012; Volume 10. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, T.; Eberly, J.H. Sudden Death of Entanglement. Science 2009, 323, 598–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, T.; Eberly, J. Sudden death of entanglement: Classical noise effects. Opt. Commun. 2006, 264, 393–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindblad, G. On the generators of quantum dynamical semigroups. Commun. Math. Phys. 1976, 48, 119–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chin, A.W.; Huelga, S.F.; Plenio, M.B. Quantum Metrology in Non-Markovian Environments. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2012, 109, 233601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, T.; Diósi, L.; Gisin, N.; Strunz, W.T. Non-Markovian quantum-state diffusion: Perturbation approach. Phys. Rev. A 1999, 60, 91–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diósi, L.; Gisin, N.; Strunz, W.T. Non-Markovian quantum state diffusion. Phys. Rev. A 1998, 58, 1699–1712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Vega, I.; Alonso, D. Dynamics of non-Markovian open quantum systems. Rev. Mod. Phys. 2017, 89, 015001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breuer, H.P.; Laine, E.M.; Piilo, J.; Vacchini, B. Colloquium: Non-Markovian dynamics in open quantum systems. Rev. Mod. Phys. 2016, 88, 021002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Jing, J.; Corn, B.; Yu, T. Dynamics of interacting qubits coupled to a common bath: Non-Markovian quantum-state-diffusion approach. Phys. Rev. A 2011, 84, 032101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.F.; Guo, G.C.; Piilo, J. Non-Markovian quantum dynamics: What is it good for? EPL (Europhys. Lett.) 2020, 128, 30001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Long, X.; Liu, R.; Tang, K.; Zhai, Y.; Nie, X.; Xin, T.; Li, J.; Lu, D. Control-enhanced non-Markovian quantum metrology. Commun. Phys. 2024, 7, 282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milne, A.R.; Edmunds, C.L.; Hempel, C.; Roy, F.; Mavadia, S.; Biercuk, M.J. Phase-Modulated Entangling Gates Robust to Static and Time-Varying Errors. Phys. Rev. Appl. 2020, 13, 024022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bishof, M.; Zhang, X.; Martin, M.J.; Ye, J. Optical Spectrum Analyzer with Quantum-Limited Noise Floor. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2013, 111, 093604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blais, A.; Gambetta, J.; Wallraff, A.; Schuster, D.I.; Girvin, S.M.; Devoret, M.H.; Schoelkopf, R.J. Quantum-information processing with circuit quantum electrodynamics. Phys. Rev. A 2007, 75, 032329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blais, A.; Grimsmo, A.L.; Girvin, S.M.; Wallraff, A. Circuit quantum electrodynamics. Rev. Mod. Phys. 2021, 93, 025005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, J.Q.; Gong, Z.R.; Zhou, L.; Liu, Y.x.; Sun, C.P.; Nori, F. Controlling the transport of single photons by tuning the frequency of either one or two cavities in an array of coupled cavities. Phys. Rev. A 2010, 81, 042304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wallquist, M.; Shumeiko, V.S.; Wendin, G. Selective coupling of superconducting charge qubits mediated by a tunable stripline cavity. Phys. Rev. B 2006, 74, 224506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castellanos-Beltran, M.A.; Lehnert, K.W. Widely tunable parametric amplifier based on a superconducting quantum interference device array resonator. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2007, 91, 083509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plenio, M.B.; Semiao, F.L. High efficiency transfer of quantum information and multiparticle entanglement generation in translation-invariant quantum chains. New J. Phys. 2005, 7, 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parkins, A.; Kimble, H. Quantum state transfer between motion and light. J. Opt. B Quantum Semiclassical Opt. 1999, 1, 496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halaski, A.; Krauss, M.G.; Basilewitsch, D.; Koch, C.P. Quantum optimal control of squeezing in cavity optomechanics. Phys. Rev. A 2024, 110, 013512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiseman, H.M.; Milburn, G.J. Quantum Measurement and Control; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Gough, J.E. Principles and applications of quantum control engineering. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. A Math. Phys. Eng. Sci. 2012, 370, 5241–5258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Genoni, M.G.; Mancini, S.; Serafini, A. Optimal feedback control of linear quantum systems in the presence of thermal noise. Phys. Rev. A 2013, 87, 042333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonnard, B.; Sugny, D. Optimal Control with Applications in Space and Quantum Dynamics; American Institute of Mathematical Sciences: Springfield, MO, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Doria, P.; Calarco, T.; Montangero, S. Optimal Control Technique for Many-Body Quantum Dynamics. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2011, 106, 190501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muller, M.M.; Said, R.S.; Jelezko, F.; Calarco, T.; Montangero, S. One decade of quantum optimal control in the chopped random basis. Rep. Prog. Phys. 2022, 85, 076001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gollub, C.; Kowalewski, M.; de Vivie-Riedle, R. Monotonic Convergent Optimal Control Theory with Strict Limitations on the Spectrum of Optimized Laser Fields. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2008, 101, 073002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sklarz, S.E.; Tannor, D.J. Loading a Bose-Einstein condensate onto an optical lattice: An application of optimal control theory to the nonlinear Schrödinger equation. Phys. Rev. A 2002, 66, 053619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morzhin, O.V.; Pechen, A.N. Krotov method for optimal control of closed quantum systems. Russ. Math. Surv. 2019, 74, 851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miki, D.; Matsumoto, N.; Matsumura, A.; Shichijo, T.; Sugiyama, Y.; Yamamoto, K.; Yamamoto, N. Generating quantum entanglement between macroscopic objects with continuous measurement and feedback control. Phys. Rev. A 2023, 107, 032410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cong, S. Control of Quantum Systems: Theory and Methods; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Brif, C.; Chakrabarti, R.; Rabitz, H. Control of quantum phenomena: Past, present and future. New J. Phys. 2010, 12, 075008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rojan, K.; Reich, D.M.; Dotsenko, I.; Raimond, J.M.; Koch, C.P.; Morigi, G. Arbitrary-quantum-state preparation of a harmonic oscillator via optimal control. Phys. Rev. A 2014, 90, 023824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goerz, M.H.; Carrasco, S.C.; Malinovsky, V.S. Quantum Optimal Control via Semi-Automatic Differentiation. Quantum 2022, 6, 871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zygote.jl. Available online: https://github.com/FluxML/Zygote.jl (accessed on 30 October 2025).

- Vitanov, N.V.; Rangelov, A.A.; Shore, B.W.; Bergmann, K. Stimulated Raman adiabatic passage in physics, chemistry, and beyond. Rev. Mod. Phys. 2017, 89, 015006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khaneja, N.; Reiss, T.; Kehlet, C.; Schulte-Herbruggen, T.; Glaser, S.J. Optimal control of coupled spin dynamics: Design of NMR pulse sequences by gradient ascent algorithms. J. Magn. Reson. 2005, 172, 296–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, M.Y.; Boixo, S.; Smelyanskiy, V.N.; Neven, H. Universal quantum control through deep reinforcement learning. npj Quantum Inf. 2019, 5, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sivak, V.V.; Eickbusch, A.; Liu, H.; Royer, B.; Tsioutsios, I.; Devoret, M.H. Model-Free Quantum Control with Reinforcement Learning. Phys. Rev. X 2022, 12, 011059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, P.; Luo, D.W.; Yu, T. Optimal entanglement generation in optomechanical systems via Krotov control of covariance matrix dynamics. Phys. Rev. Res. 2025, 7, 013161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Z.; Luo, D.W. Many-body quantum state control in the presence of environmental noise. Quantum Inf. Comput. 2023, 23, 937–948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohtsuki, Y.; Nakagami, K.; Zhu, W.; Rabitz, H. Quantum optimal control of wave packet dynamics under the influence of dissipation. Chem. Phys. 2003, 287, 197–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekert, A.K.; Knight, P.L. Correlations and squeezing of two-mode oscillations. Am. J. Phys. 1989, 57, 692–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, G.S. Quantum Optics; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Vidal, G.; Werner, R.F. Computable measure of entanglement. Phys. Rev. A 2002, 65, 032314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simon, R. Peres-Horodecki Separability Criterion for Continuous Variable Systems. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2000, 84, 2726–2729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plenio, M.B. Logarithmic Negativity: A Full Entanglement Monotone That is not Convex. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2005, 95, 090503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uhlmann, A. The “transition probability” in the state space of a∗-algebra. Rep. Math. Phys. 1976, 9, 273–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banchi, L.; Braunstein, S.L.; Pirandola, S. Quantum Fidelity for Arbitrary Gaussian States. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2015, 115, 260501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plenio, M.B.; Hartley, J.; Eisert, J. Dynamics and manipulation of entanglement in coupled harmonic systems with many degrees of freedom. New J. Phys. 2004, 6, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Innes, M.; Edelman, A.; Fischer, K.; Rackauckas, C.; Saba, E.; Shah, V.B.; Tebbutt, W. A Differentiable Programming System to Bridge Machine Learning and Scientific Computing. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1907.07587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strunz, W.T.; Diosi, L.; Gisin, N. Open system dynamics with non-Markovian quantum trajectories. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1999, 82, 1801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Percival, I. Quantum State Diffusion; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Hartmann, R.; Strunz, W.T. Exact open quantum system dynamics using the hierarchy of pure states (HOPS). J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2017, 13, 5834–5845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritschel, G.; Eisfeld, A. Analytic representations of bath correlation functions for ohmic and superohmic spectral densities using simple poles. J. Chem. Phys. 2014, 141, 094101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, T. Non-Markovian quantum trajectories versus master equations: Finite-temperature heat bath. Phys. Rev. A 2004, 69, 062107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jing, J.; Zhao, X.; You, J.Q.; Strunz, W.T.; Yu, T. Many-body quantum trajectories of non-Markovian open systems. Phys. Rev. A 2013, 88, 052122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jing, J.; Yu, T. Non-Markovian Relaxation of a Three-Level System: Quantum Trajectory Approach. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2010, 105, 240403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strunz, W.T.; Yu, T. Convolutionless Non-Markovian master equations and quantum trajectories: Brownian motion. Phys. Rev. A 2004, 69, 052115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, D.W.; Lam, C.H.; Wu, L.A.; Yu, T.; Lin, H.Q.; You, J.Q. Higher-order solutions to non-Markovian quantum dynamics via a hierarchical functional derivative. Phys. Rev. A 2015, 92, 022119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.Z.; Yip, C.T.; Deng, H.Y.; Chen, M.; Yu, T.; You, J.Q.; Lam, C.H. Approach to solving spin-boson dynamics via non-Markovian quantum trajectories. Phys. Rev. A 2014, 90, 022122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buchmann, L.F.; Mølmer, K.; Petrosyan, D. Controllability in tunable chains of coupled harmonic oscillators. Phys. Rev. A 2018, 97, 042111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okamoto, H.; Gourgout, A.; Chang, C.Y.; Onomitsu, K.; Mahboob, I.; Chang, E.Y.; Yamaguchi, H. Coherent phonon manipulation in coupled mechanical resonators. Nat. Phys. 2013, 9, 480–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barredo, D.; de Léséleuc, S.; Lienhard, V.; Lahaye, T.; Browaeys, A. An atom-by-atom assembler of defect-free arbitrary two-dimensional atomic arrays. Science 2016, 354, 1021–1023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Luo, D.-W.; Yu, E.; Yu, T. Optimal Transfer of Entanglement in Oscillator Chains in Non-Markovian Open Systems. Entropy 2025, 27, 1239. https://doi.org/10.3390/e27121239

Luo D-W, Yu E, Yu T. Optimal Transfer of Entanglement in Oscillator Chains in Non-Markovian Open Systems. Entropy. 2025; 27(12):1239. https://doi.org/10.3390/e27121239

Chicago/Turabian StyleLuo, Da-Wei, Edward Yu, and Ting Yu. 2025. "Optimal Transfer of Entanglement in Oscillator Chains in Non-Markovian Open Systems" Entropy 27, no. 12: 1239. https://doi.org/10.3390/e27121239

APA StyleLuo, D.-W., Yu, E., & Yu, T. (2025). Optimal Transfer of Entanglement in Oscillator Chains in Non-Markovian Open Systems. Entropy, 27(12), 1239. https://doi.org/10.3390/e27121239