Statistical CSI-Based Beamspace Transmission for Massive MIMO LEO Satellite Communications

Abstract

1. Introduction

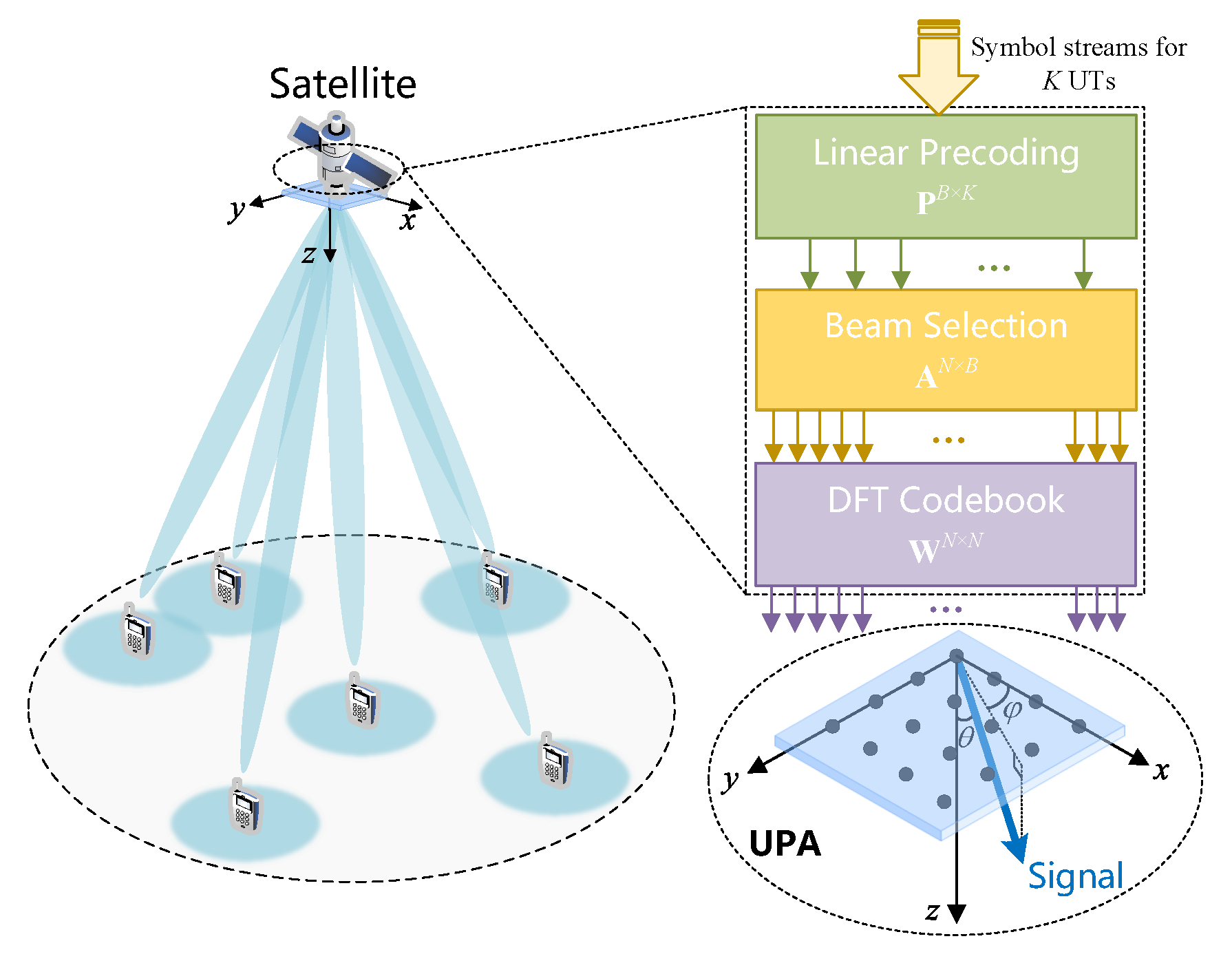

- We propose an sCSI-based multibeam transmission framework. Specifically, we first select beams for UTs from a fixed beamforming codebook, then perform LP based on the equivalent beamspace channel. To fully exploit the sCSI for performance optimization, we analyze the sCSI-based upper and lower bound approximations of the ergodic sum rate and show that the upper bound offers a tighter estimate. Based on this approximation, we formulate the weighted sum rate (WSR) maximization problem, subject to constraints on the power budget and the maximum number of simultaneously activated beams.

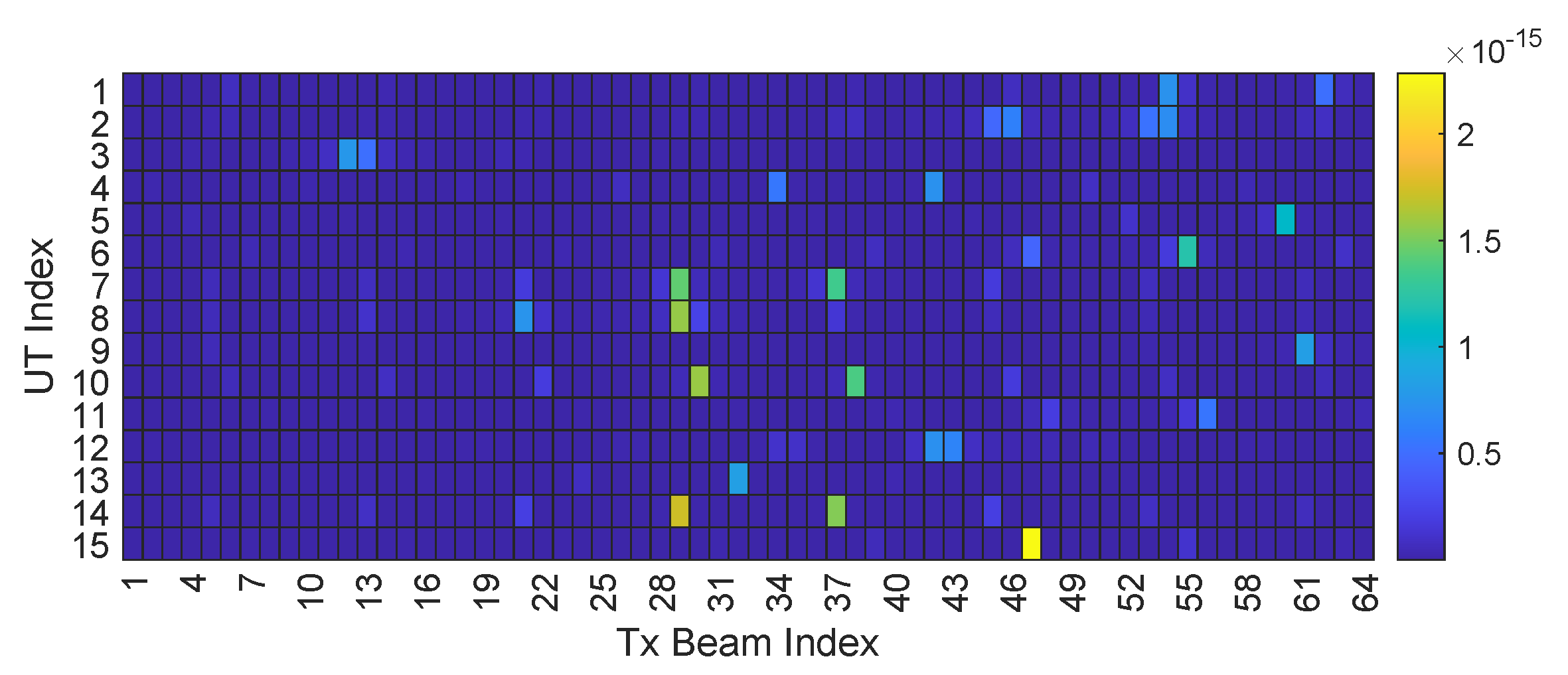

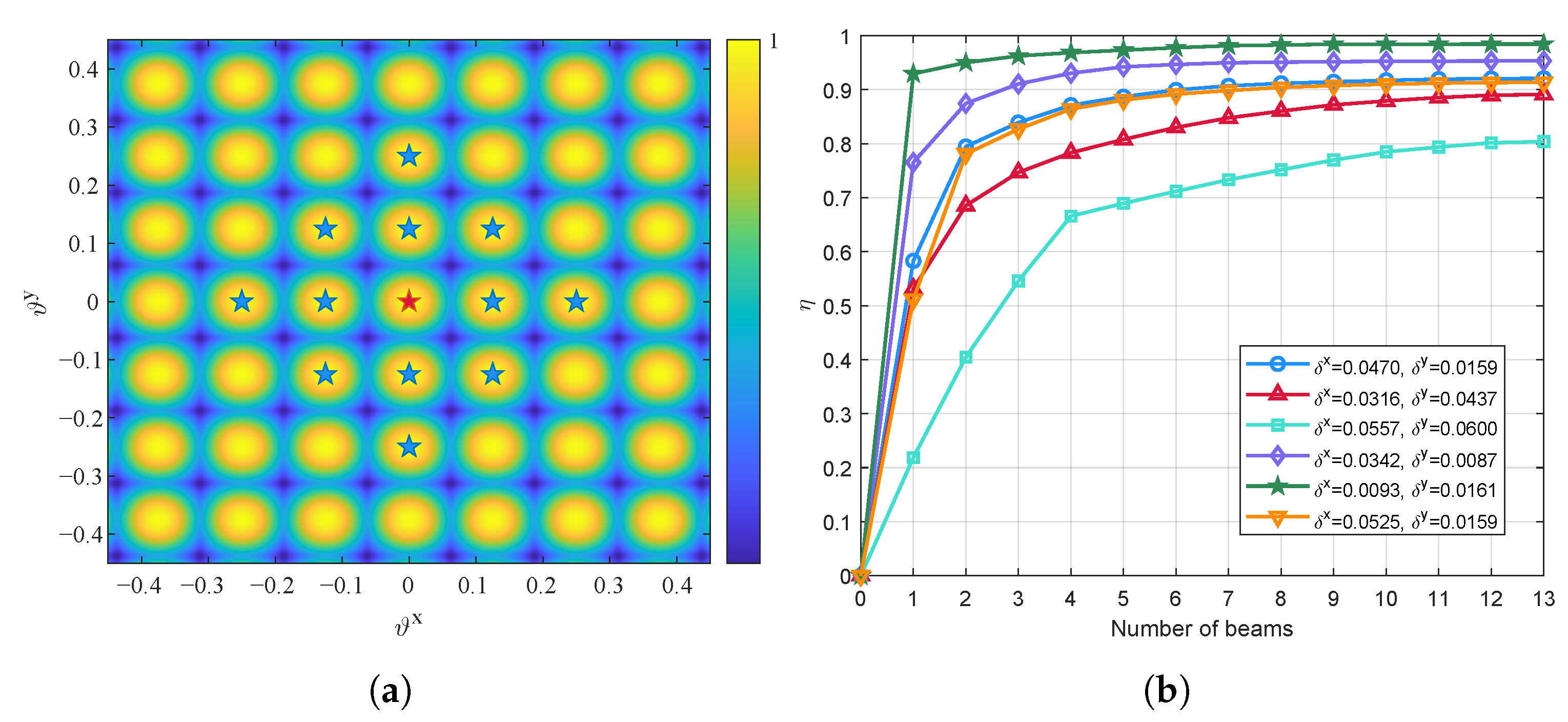

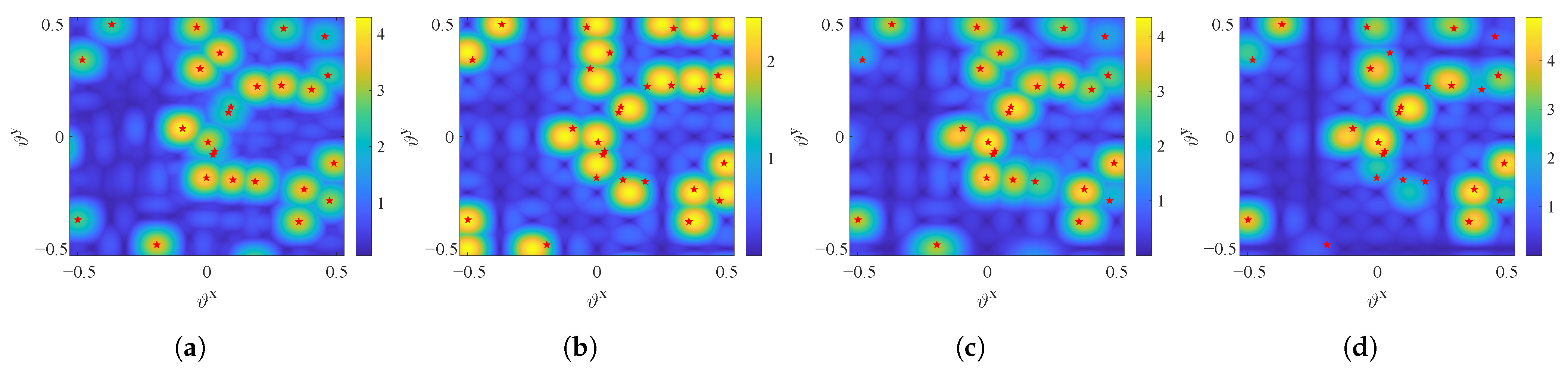

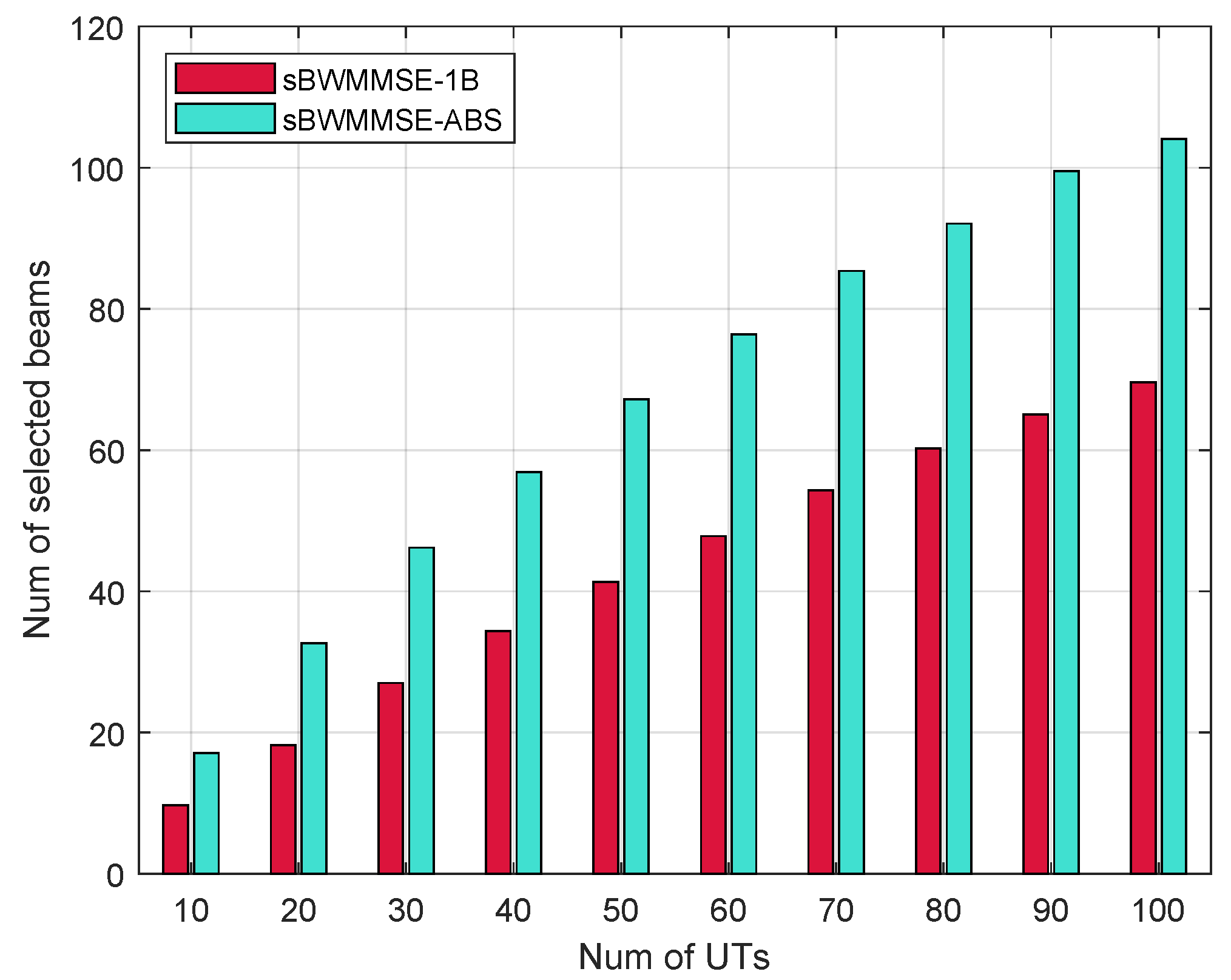

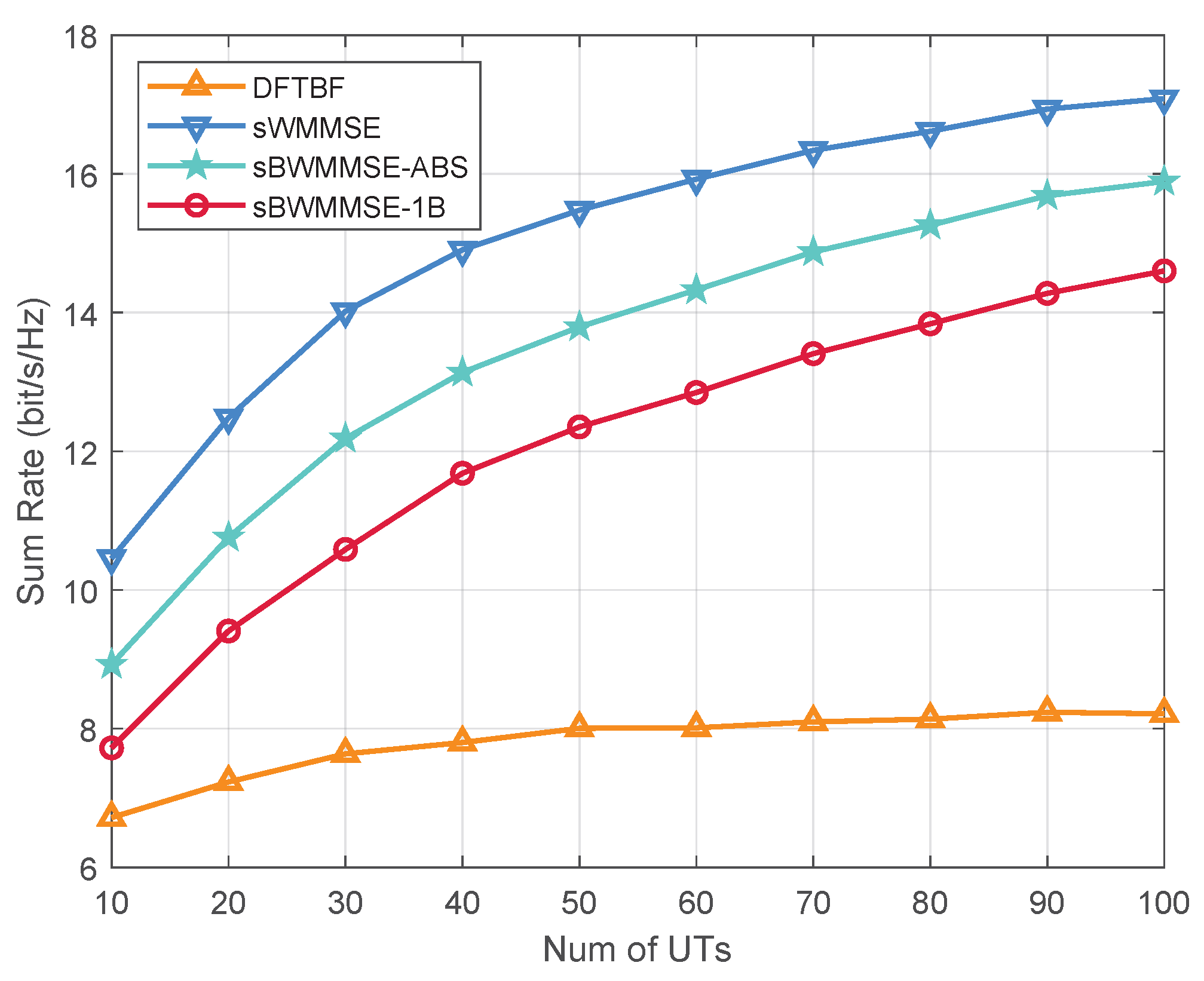

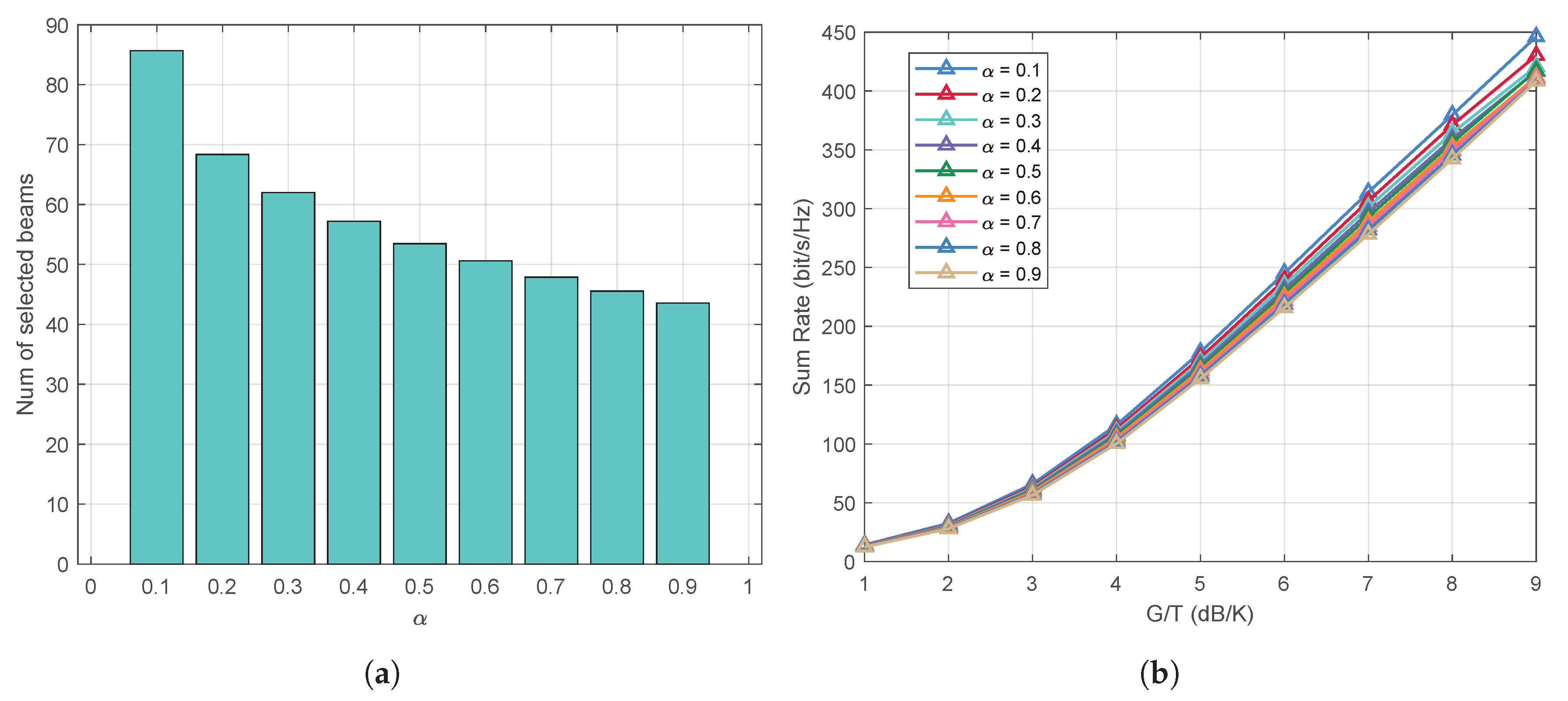

- We propose an angle-based beam selection algorithm that efficiently selects beams from a fixed codebook. To improve the beamspace representation of the antenna-domain channel, we evaluate the normalized beamforming gain of each beam toward a given UT and assign at least one beam to each UT. In addition, we simplify the beam selection process and reduce feedback overhead by reformulating the beamforming gain as a function of the beam’s angular offset from the UT’s line-of-sight (LoS) direction. Simulation results demonstrate that, compared with the baseline scheme that selects a single beam best aligned with each UT’s LoS direction, the proposed algorithm achieves improved sum rate performance.

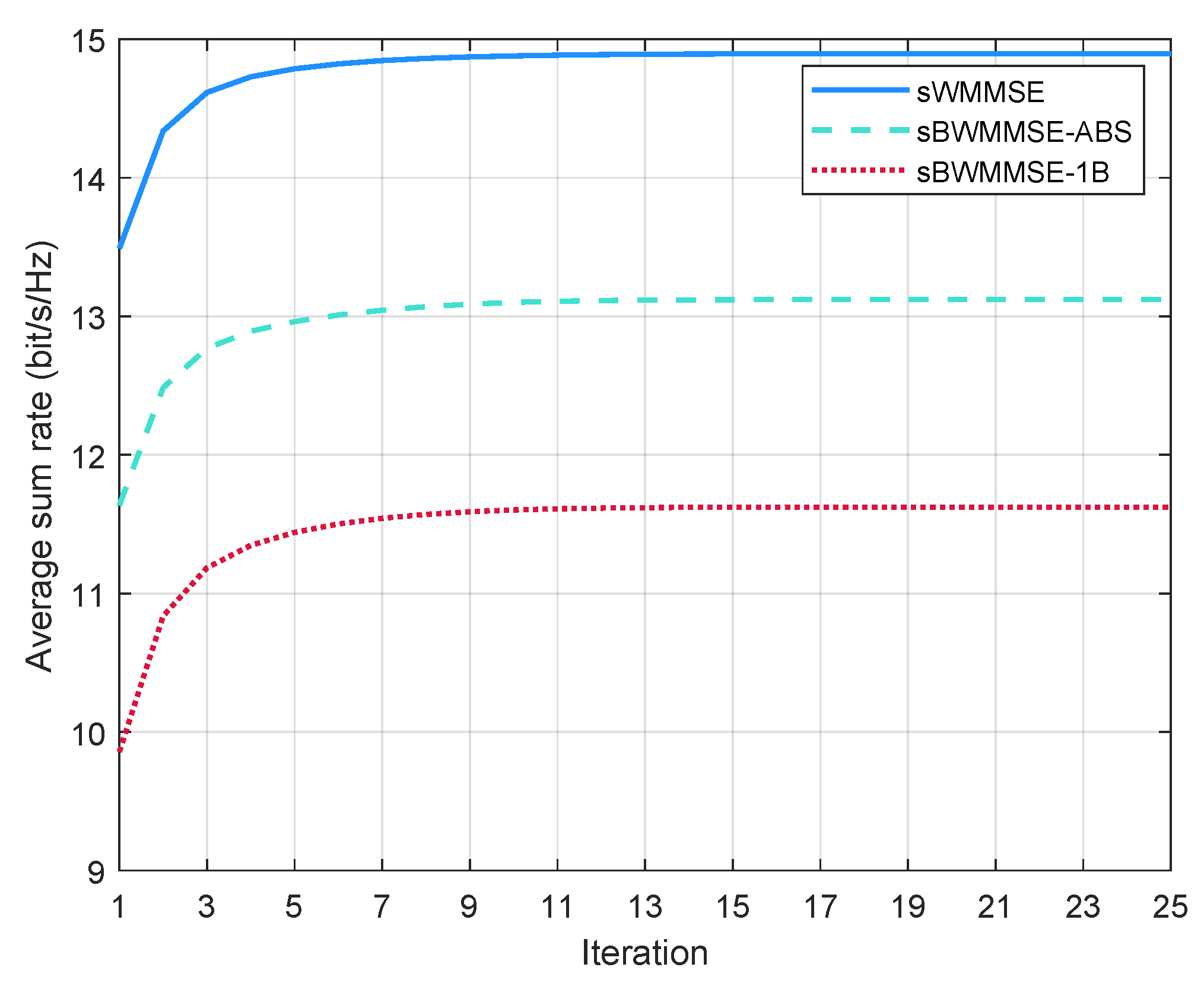

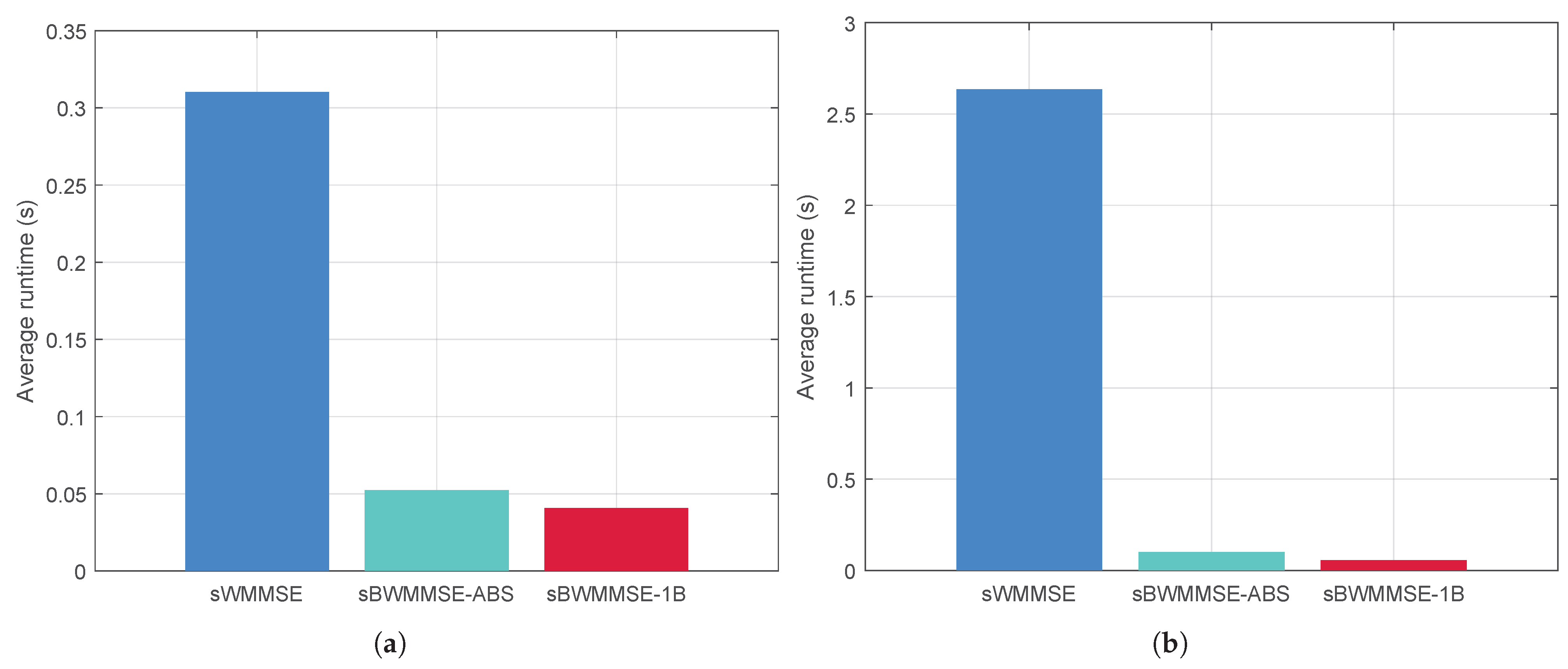

- Based on the equivalent beamspace channel, we reformulate the WSR maximization problem as a WMMSE problem through covariance decomposition and derive an sCSI-based WMMSE (sWMMSE) precoding scheme. The proposed beamspace precoding effectively lowers computational complexity compared with antenna-domain schemes, as it operates on a reduced-dimensional beamspace channel matrix. Simulation results show that the proposed sWMMSE precoding scheme converges rapidly within only a few iterations.

2. System Model

2.1. System Setup

2.2. Channel Model

2.3. Statistical CSI

2.4. Problem Formulation

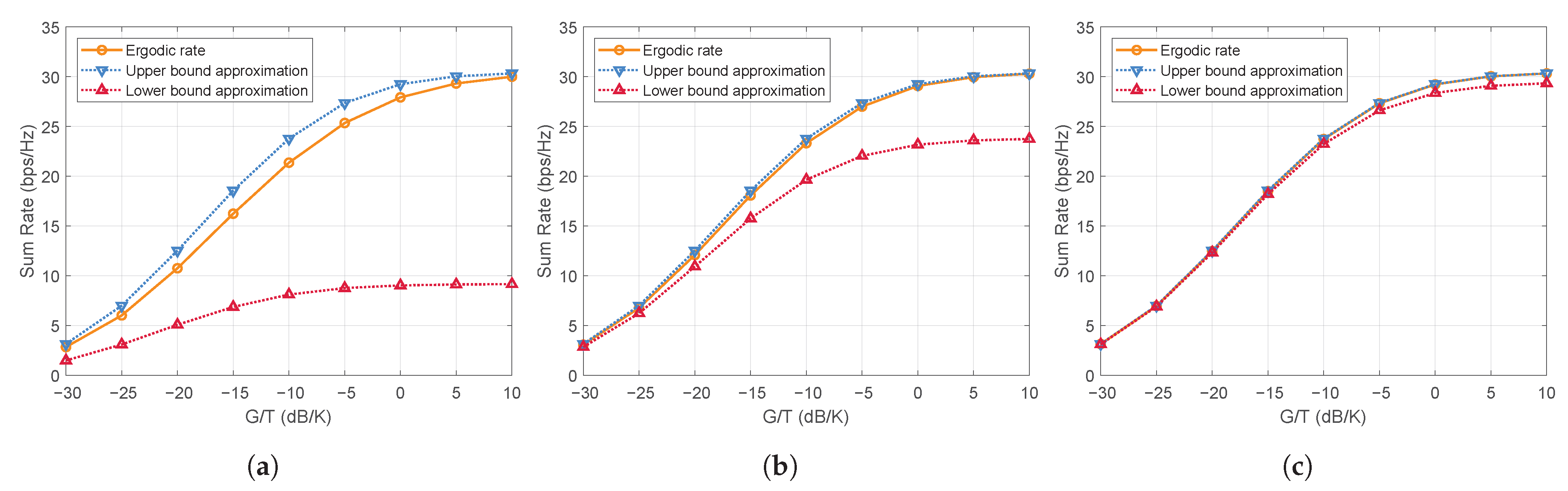

- Upper bound approximation: According to Jensen’s inequality and the concavity of , an upper bound of can be obtained aswhere .

- Lower bound approximation: Let . By treating as the effective channel and regarding the random perturbation as uncorrelated noise, a lower bound of can be derived aswhere .

3. Beamspace Transmission Design for Sum Rate Maximization Problem

3.1. Angle-Based Beam Selection Algorithm

| Algorithm 1 Angle-based Beam Selection Algorithm |

| Input: , W, B.

1: Initialize: 1-a: , . 1-b: , . 2: for do 3: . 4: Calculate as described in (18). 5: Set with indices and sequences . 6: for do 7: Calculate as described in (18). 8: end for 9: . 10: end for 11: 12: if then 13: for do 14: . 15: end for 16: . 17: end if 18: Calculate as described in (26). Output: . |

3.2. Beamspace WMMSE Precoding

| Algorithm 2 Beamspace WMMSE Precoding |

| Input: , , , . 1: Initialize: 1-a: . 1-b: , . 2: while do 3: . 4: , . 5: Update as in (32). 6: Update as in (34). 7: Update as in (37). 8: Calculate as described in (14). 9: if then 10: break 11: end if 12: end while Output: . |

4. Simulation Results

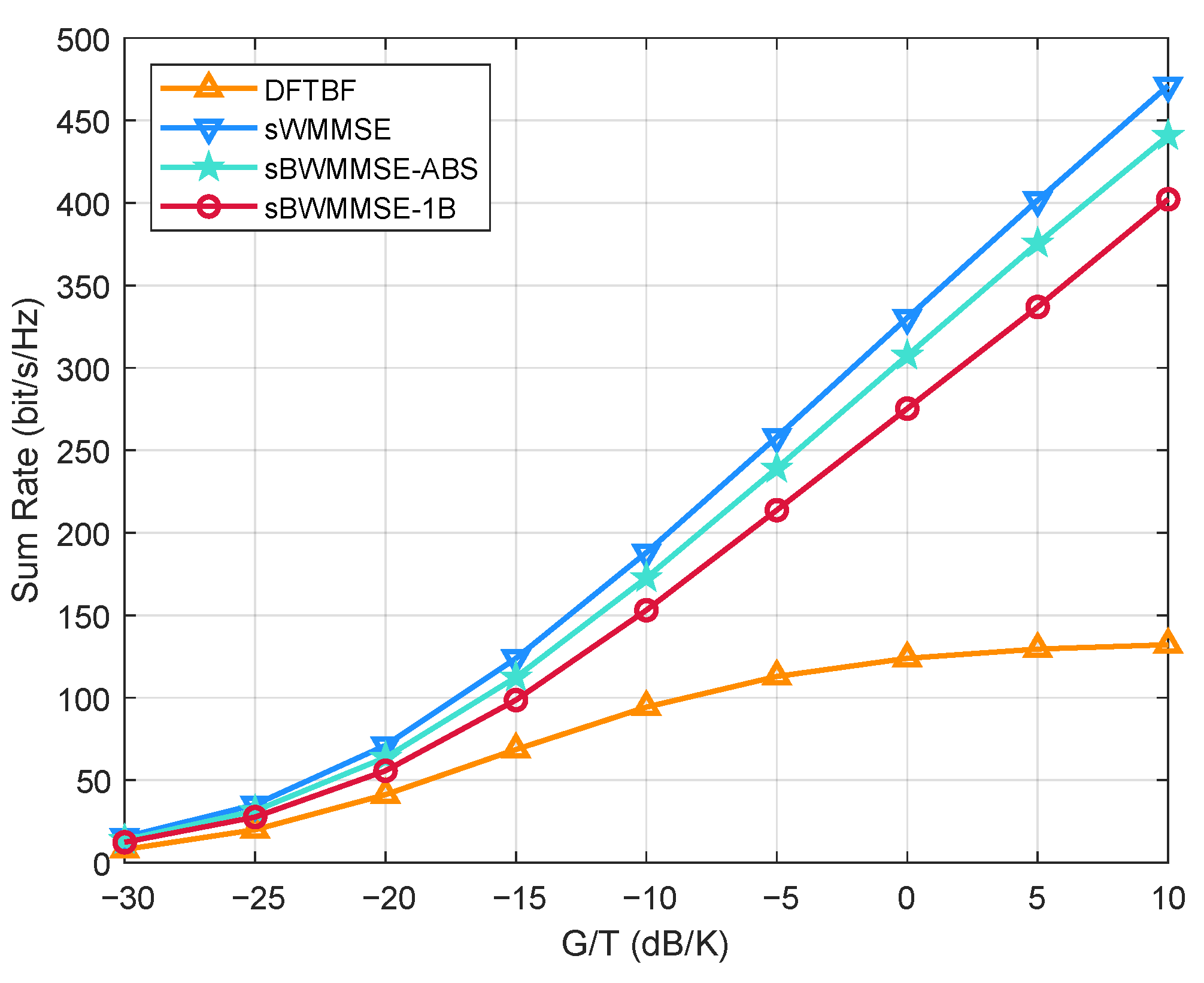

- DFTBF: A baseline that selects K beams from the fixed DFT codebook that best matches the UTs’ LoS directions. This method has the lowest computational complexity but does not incorporate LP methods for interference mitigation, thus serving as a performance lower bound.

- sWMMSE: An sCSI-based antenna-domain WMMSE precoding scheme applied directly to the full channel, serving as the performance upper bound.

- sBWMMSE-ABS: An sCSI-based beamspace WMMSE precoding scheme that first selects B beams from based on the UTs’ angular information (Algorithm 1), and then performs WMMSE precoding in the beam domain (Algorithm 2).

- sBWMMSE-1B: A simplified scheme that selects a single LoS-matched beam for each UT, followed by sCSI-based beamspace WMMSE precoding.

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| LEO | Low Earth orbit |

| MEO | Medium Earth orbit |

| GEO | Geostationary orbit |

| UT | User terminal |

| OBP | On-board processor |

| CoMSat | Coordinated multiple-satellite |

| CCI | Co-channel interference |

| SE | Spectral efficiency |

| CSI | Channel state information |

| iCSI | Instantaneous channel state information |

| sCSI | Statistical channel state information |

| AoD | Angle of departure |

| LoS | Line-of-sight |

| MIMO | Multiple-input multiple-output |

| mMIMO | Massive multiple-input multiple-output |

| UPA | Uniform planar array |

| DBF | Digital beamforming |

| DFT | Discrete Fourier transform |

| FFT | Fast Fourier transform |

| FFR | Full-frequency reuse |

| MSE | Mean square error |

| LP | Linear precoding |

| WSR | Weighted sum rate |

| WMMSE | Weighted minimum mean square error |

| sWMMSE | sCSI-based weighted minimum mean square error |

| MF | Matched filter |

| ZF | Zero-forcing |

| RZF | Regularized zero-forcing |

| SINR | Signal-to-interference-plus-noise ratio |

| SLNR | Signal-to-leakage-plus-noise ratio |

Appendix A. Proof of Proposition 1

Appendix B. Proof of Proposition 2

References

- Wang, W.; Zhu, Y.; Wang, Y.; Ding, R.; Chatzinotas, S. Toward Mobile Satellite Internet: The Fundamental Limitation of Wireless Transmission and Enabling Technologies. Engineering 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heo, J.; Sung, S.; Lee, H.; Hwang, I.; Hong, D. MIMO Satellite Communication Systems: A Survey From the PHY Layer Perspective. IEEE Commun. Surveys Tuts. 2023, 25, 1543–1570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernandez, J.A.; Reviriego, P. A brief introduction to satellite communications for Non-Terrestrial Networks (NTN). arXiv 2023, arXiv:2305.04590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahboob, S.; Liu, L. Revolutionizing Future Connectivity: A Contemporary Survey on AI-Empowered Satellite-Based Non-Terrestrial Networks in 6G. IEEE Commun. Surv. Tuts. 2024, 26, 1279–1321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, K.X.; You, L.; Wang, J.; Gao, X.; Tsinos, C.G.; Chatzinotas, S.; Ottersten, B. Downlink Transmit Design for Massive MIMO LEO Satellite Communications. IEEE Trans. Commun. 2022, 70, 1014–1028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kodheli, O.; Lagunas, E.; Maturo, N.; Sharma, S.K.; Shankar, B.; Montoya, J.F.M.; Duncan, J.C.M.; Spano, D.; Chatzinotas, S.; Kisseleff, S.; et al. Satellite Communications in the New Space Era: A Survey and Future Challenges. IEEE Commun. Surv. Tuts. 2021, 23, 70–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angeletti, P.; De Gaudenzi, R. A Pragmatic Approach to Massive MIMO for Broadband Communication Satellites. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 132212–132236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palisetty, R.; Eappen, G.; Singh, V.; Socarras, L.M.G.; Ha, V.N.; Vásquez-Peralvo, J.A.; Rios, J.L.G.; Duncan, J.C.M.; Martins, W.A.; Chatzinotas, S.; et al. FPGA Implementation of Efficient 2D-FFT Beamforming for On-Board Processing in Satellites. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE 98th Vehicular Technology Conference (VTC2023-Fall), Toronto, ON, Canada, 5–8 September 2023; pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Garcés-Socarrás, L.M.; González-Rios, J.L.; Palisetty, R.; Cuiman, R.; Ha, V.N.; Vásquez-Peralvo, J.A.; Eappen, G.; Nguyen, T.T.; Duncan, J.C.M.; Chatzinotas, S.; et al. Efficient Digital Beamforming for Satellite Payloads Using a 2D FFT-Based Parallel Architecture. In Proceedings of the 2025 IEEE International Symposium on Circuits and Systems (ISCAS), London, UK, 25–28 May 2025; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Ha, V.N.; Abdullah, Z.; Eappen, G.; Duncan, J.C.M.; Palisetty, R.; Rios, J.L.G.; Martins, W.A.; Chou, H.F.; Vasquez, J.A.; Garces-Socarras, L.M.; et al. Joint Linear Precoding and DFT Beamforming Design for Massive MIMO Satellite Communication. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE Globecom Workshops, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 4–8 December 2022; pp. 1121–1126. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, A.; Lei, L.; Hu, X.; Lagunas, E.; Pérez-Neira, A.I.; Chatzinotas, S. Adaptive Beam Pattern Selection and Resource Allocation for NOMA-Based LEO Satellite Systems. In Proceedings of the IEEE Global Communications Conference, (GLOBECOM), Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 4–8 December 2022; pp. 674–679. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, S.; Wang, Y.; Sun, G.; You, L.; Wang, W.; Ding, R. Energy and Computational Efficient Precoding for LEO Satellite Communications. In Proceedings of the IEEE Global Communications Conference, (GLOBECOM), Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, 4–8 December 2023; pp. 1872–1877. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, M.; Zhang, F.; Shan, L.; Wang, M.M. Kalman Filter Based Precoding Approach for Inter-Beam Interference Cancellation in Maritime MTC Satellite. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE 6th International Conference on Computer and Communication Systems (ICCCS), Chengdu, China, 23–26 April 2021; pp. 943–948. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Hou, H.; Yi, X.; Wang, W.; Jin, S. Towards Unified AI Models for MU-MIMO Communications: A Tensor Equivariance Framework. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2406.09022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Ha, V.N.; Ntontin, K.; Yan, H.; Wang, W.; Chatzinotas, S.; Ottersten, B. Statistical CSI-Based Distributed Precoding Design for OFDM-Cooperative Multi-Satellite Systems. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2505.08038. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y.; Wang, Y.; Wang, J.; You, L.; Wang, W.; Gao, X. Robust Downlink Precoding for LEO Satellite Systems With Per-Antenna Power Constraints. IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol. 2022, 71, 10694–10711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- You, L.; Li, K.X.; Wang, J.; Gao, X.; Xia, X.G.; Ottersten, B. Massive MIMO Transmission for LEO Satellite Communications. IEEE J. Sel. Areas Commun. 2020, 38, 1851–1865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Röper, M.; Matthiesen, B.; Wübben, D.; Popovski, P.; Dekorsy, A. Beamspace MIMO for Satellite Swarms. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE Wireless Communications and Networking Conference (WCNC), Austin, TX, USA, 10–13 April 2022; pp. 1307–1312. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmad, I.; Nguyen, K.D.; Letzepis, N.; Lechner, G.; Joroughi, V. Zero-Forcing Precoding With Partial CSI in Multibeam High Throughput Satellite Systems. IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol. 2021, 70, 1410–1420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, J.; Im, G.; Jung, S.; Ryu, J.G.; Byun, W.J. Partial CSI based Regularized Zero-Forcing Precoder for Multibeam Satellite Communications toward 6G Networks. In Proceedings of the 2021 International Conference on Information and Communication Technology Convergence (ICTC), Jeju Island, Republic of Korea, 20–22 October 2021; pp. 1579–1581. [Google Scholar]

- Fatema, N.; Hua, G.; Xiang, Y.; Peng, D.; Natgunanathan, I. Massive MIMO Linear Precoding: A Survey. IEEE Syst. J. 2018, 12, 3920–3931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ha, V.N.; Nguyen, D.H.N.; Duncan, J.C.M.; Gonzalez-Rios, J.L.; Peralvo, J.A.V.; Eappen, G.; Garces-Socarras, L.M.; Palisetty, R.; Chatzinotas, S.; Ottersten, B. User-Centric Beam Selection and Precoding Design for Coordinated Multiple-Satellite Systems. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE 35th International Symposium on Personal, Indoor and Mobile Radio Communications (PIMRC), Valencia, Spain, 2–5 September 2024; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Papathanassiou, A.; Salkintzis, A.; Mathiopoulos, P. A comparison study of the uplink performance of W-CDMA and OFDM for mobile multimedia communications via LEO satellites. IEEE Pers. Commun. 2001, 8, 35–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fontan, F.; Vazquez-Castro, M.; Cabado, C.; Garcia, J.; Kubista, E. Statistical modeling of the LMS channel. IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol. 2001, 50, 1549–1567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, S.; Wang, Y.; Sun, G.; Wang, W.; Wang, J.; Ottersten, B. Distributed Beamforming for Multiple LEO Satellites With Imperfect Delay and Doppler Compensations: Modeling and Rate Analysis. IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol. 2025, 74, 14978–14984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Letzepis, N.; Grant, A.J. Capacity of the Multiple Spot Beam Satellite Channel With Rician Fading. IEEE Trans. Inf. Theory 2008, 54, 5210–5222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, W.; Bu, X.; Gao, X.; Xing, C.; Hanzo, L. Beamspace Precoding and Beam Selection for Wideband Millimeter-Wave MIMO Relying on Lens Antenna Arrays. IEEE Trans. Signal Process. 2019, 67, 6301–6313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, A.; Lau, V.K.N. Two-Stage Subspace Constrained Precoding in Massive MIMO Cellular Systems. IEEE Trans. Wirel. Commun. 2015, 14, 3271–3279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sayeed, A.; Brady, J. Beamspace MIMO for high-dimensional multiuser communication at millimeter-wave frequencies. In Proceedings of the IEEE Global Communications Conference, (GLOBECOM), Atlanta, GA, USA, 9–13 December 2013; pp. 3679–3684. [Google Scholar]

- 3rd Generation Partnership Project (3GPP). Solutions for NR to Support Non-Terrestrial Networks (NTN); Technical Report TR 38.821 V16.2.0, 3GPP; 3rd Generation Partnership Project (3GPP): Sophia Antipolis Cedex, France, 2023; Release 16. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Hraishawi, H.; Chougrani, H.; Kisseleff, S.; Lagunas, E.; Chatzinotas, S. A Survey on Nongeostationary Satellite Systems: The Communication Perspective. IEEE Commun. Surv. Tuts. 2023, 25, 101–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Parameter | Value |

|---|---|

| Orbit altitude | 785.41 km |

| Transmit antenna size | / |

| Maximum transmit power | 300 W |

| Gain of TX antennas | 0 dBi |

| Gain of RX antennas | 0 dBi |

| UT antenna noise temperature | 290 K |

| UT G/T | dB/K |

| Number of UTs | 10–70 |

| Distribution of UTs | Uniform |

| Carrier frequency | 2 GHz |

| System bandwidth | 20 MHz |

| Methods | Complexity Order |

|---|---|

| DFTBF | |

| sWMMSE | |

| sBWMMSE-1B | |

| sBWMMSE-ABS |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Dong, Q.; Wang, Y.; Hu, N.; Zhu, Y.; Wang, W.; Chai, L. Statistical CSI-Based Beamspace Transmission for Massive MIMO LEO Satellite Communications. Entropy 2025, 27, 1214. https://doi.org/10.3390/e27121214

Dong Q, Wang Y, Hu N, Zhu Y, Wang W, Chai L. Statistical CSI-Based Beamspace Transmission for Massive MIMO LEO Satellite Communications. Entropy. 2025; 27(12):1214. https://doi.org/10.3390/e27121214

Chicago/Turabian StyleDong, Qian, Yafei Wang, Nan Hu, Yiming Zhu, Wenjin Wang, and Li Chai. 2025. "Statistical CSI-Based Beamspace Transmission for Massive MIMO LEO Satellite Communications" Entropy 27, no. 12: 1214. https://doi.org/10.3390/e27121214

APA StyleDong, Q., Wang, Y., Hu, N., Zhu, Y., Wang, W., & Chai, L. (2025). Statistical CSI-Based Beamspace Transmission for Massive MIMO LEO Satellite Communications. Entropy, 27(12), 1214. https://doi.org/10.3390/e27121214