1. Introduction

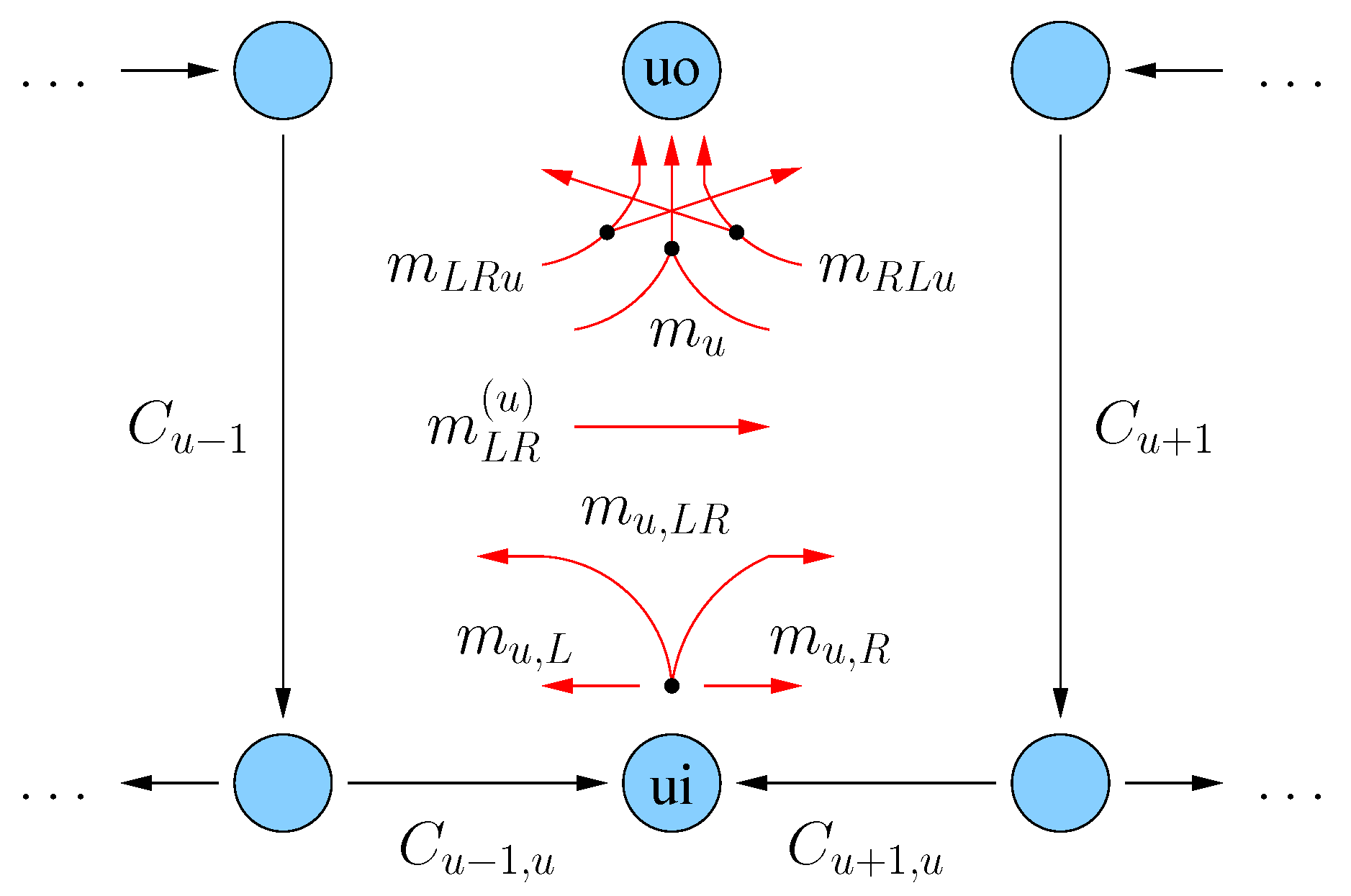

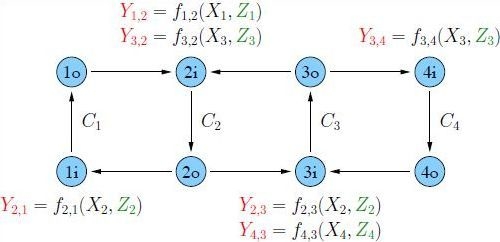

Consider a line network with edge and node capacity constraints as shown in

Figure 1. “Supernode”

u,

, consists of two nodes

where the “

i” represents “input” and “

o” represents “output”. More generally, for

N supernodes

we have

nodes

and

directed edges

Every edge

is labeled with a capacity constraint

and for simplicity we write

as

.

Figure 1.

A line network with edge and node capacity constraints.

Figure 1.

A line network with edge and node capacity constraints.

Let

denote a multicast traffic session, where

are supernodes. The meaning is that a source message is available at supernode

u and is destined for supernodes in the set

. Since

u takes on

N values and

can take on

values, there are up to

multicast sessions. We associate

sources with input nodes

and

sinks with output nodes

. Such line networks are special cases of discrete memoryless networks (DMNs) and we use the capacity definition from [

1] (Section III.D). The capacity region was recently established in [

2]. A binary linear network code achieves capacity and progressive d-separating edge-cut (PdE) bounds [

3] provide the converse.

The goal of this work is to extend results from [

2] to

wireless line networks by using insights from two-way relaying [

4], broadcasting with cooperation [

5], and broadcasting with side-information [

6]. The model is shown in

Figure 2 where the difference to

Figure 1 is that node

transmits over a two-receiver broadcast channel (BC)

to nodes

and

(see [

7]). The channel outputs at node

are

for some functions

and

, and where the

,

, are statistically independent. We permit the noise random variables

to be common to

and

for generality. The edges

are the usual links with capacity

. Such line networks are again special cases DMNs and we use the capacity definition from [

1] (Section III.D).

Figure 2.

A line network with broadcasting and node capacity constraints.

Figure 2.

A line network with broadcasting and node capacity constraints.

The paper is organized as follows.

Section 2 reviews the capacity region for line networks derived in [

2].

Section 3 gives our main result: an achievable rate region for line networks with BCs.

Section 4 shows that this region is the capacity region for orthogonal, deterministic, and physically degraded BCs, and packet erasure BCs with feedback. We further show that for physically degraded Gaussian BCs the best input distributions are Gaussian.

Section 5 relates our work to recent work on relaying and concludes the paper.

2. Review of Wireline Capacity

We review the main result from [

2]. Let

and

denote the message bits and rate, respectively, of traffic session

. We collect the bits going through supernode

u into the following 8 sets:

The idea is that

and represent traffic flowing from left-to-right and right-to-left, respectively, through supernode u without being required at supernode u;

, represent traffic flowing from left-to-right and right-to-left, respectively, through supernode u but required at supernode u also;

represents traffic from the left and right, respectively, and destined for supernode u but not destined for any nodes on the right and left (so this traffic “stops" at supernode u on its way from the left or right);

, , and represent traffic originating at supernode u and destined for nodes on both the left and right, right only, and left only, respectively.

The non-negative message rates are denoted

,

,

,

,

,

,

, and

.

Theorem 1 (Theorem 1 in [2]) The capacity region of a line network with supernodes is specified by the inequalities Remark 1 The converse in [2] follows by PdE arguments [3] and achievability follows by using rate-splitting, routing, copying, and “butterfly” binary linear network coding. We review both the PdE bound and the coding method after Examples 1 and 2 below. Remark 2 Inequalities (15) and (16) are classic cut bounds [8] (Section 14.10). If we have no node constraints () then (15) and (16) are routing bounds, so routing is optimal for this case (see [9]). Example 1 Consider for which we have 9 possible multicast sessions. The network is as in Figure 1 but where the nodes and are removed, as well as the edges touching them. For supernode we collect 7 of these sessions into 2 sets as follows. (We abuse notation and write as .)Sessions and are missing from (17) and (18) because they do not involve supernode 1. Similarly, for supernode 2 we collect the 9 sessions into 8 sets:Finally, for supernode 3 we have the 2 setsThe inequalities of Theorem 1 are We discuss the 7 inequalities (23)–(25) in more detail. Consider first the converse. We write a classic cut as , where is the set of nodes on one side of the cut and is the set of nodes on the other side of the cut. The inequalities with the edge capacities , , , are classic cut bounds. For example, the cut gives the bound .

The inequalities with the “node" capacities , , in (23)–(25) are not classic cut bounds. To see this, consider the bound . A classic cut bound would require us to choose because and generally include messages with positive rates for all supernodes. But then the only way to isolate the edge is to choose which gives the too-weak bound .

We require a stronger method and use PdE bounds. We use the notation in [

3]:

is the edge cut,

is the set of sources whose sum-rate we bound,

is the permutation that defines the order in which we test the sources. Consider the edge cut

, the source set

with the traffic sessions (17) and (18), and any permutation

for which the sessions (17) appear before the sessions (18). After removing edge

the PdE algorithm removes edge

because node

has no incoming edges. We next test if the sessions (17) are disconnected from one of their destinations; indeed they are because one of these destinations is node

. The PdE algorithm now removes the remaining edges in the graph because the nodes

are not the sources of messages in (18). As a result, the remaining sessions (18) are disconnected from their destinations and the PdE bound gives

. The bound on

follows similarly. The bound on

is more subtle and we develop it in a more general context below (see the text after Example 2).

For achievability, note that all 7 inequalities are routing bounds except for the bound on

in (24). To approach this bound, we use a classic method and XOR the bits in sessions

and

before sending them through edge

. More precisely, we combine

and

to form

by which we mean the bits formed when the smaller-rate message bits are XORed with a corresponding number of bits of the larger-rate message. The remaining larger-rate message bits are appended so that

has rate

. The message (26) is sent to node

together with the remaining messages received at node

. We must thus satisfy the bound on

in (24).

For the routing bounds there are two subtleties. First, node forwards to the left the uncoded bits , , and . However, it must treat specially because it cannot necessarily determine and . But if then node can remove the appended bits in (26) and communicate to node at rate , rather than . If then no bits should be removed and node again communicates to node at rate . The bits node forwards to the right are treated similarly. In summary, the rates for messages and on edges and , respectively, are simply the classic routing rates.

The second routing subtlety is more straightforward: after node receives the XORed bits, it can recover by subtracting the bits that it knows. Finally, node transmits to node . Node operates similarly.

Example 2 Consider Figure 1 with for which there are 28 possible multicast sessions. For supernode 1 we collect 19 of these sessions into 2 sets as follows.The 9 sessions not involving supernode 1 are missing. The rate bounds for supernode 1 are given by (14)–(16) with . The messages and rate bounds for supernode 4 are similar. Similarly, for supernode 2 we collect 26 of 28 sessions into 8 sets as follows.Sessions and are missing. The rate bounds for supernode 2 are given by (14)–(16) with . The messages and rate bounds for supernode 3 are similar. The converse and coding method for are entirely similar to the case . However, we have not yet developed the PdE bound for and edge cut . We do this now but in the more general context of and for any u.

So consider the PdE bound with

and

having all the traffic sessions (6)–(13) except for (7). We choose

so that the sessions (8)–(10) appear first, the sessions (6) and (11)–(12) appear second, and the sessions (13) appear last. The PdE algorithm performs the following steps.

Remove

and then remove

and

because node

has no incoming edges. The resulting graph at supernode

u is shown in

Figure 3.

Test if the sessions (8)–(10) (sessions , , ) are disconnected from one of their destinations, which they are because one of these destinations is node .

Remove all edges to the right of supernode u because the nodes to the right are not the sources of the remaining sessions (6), (11)–(13) (sessions , , , and ).

Test if the sessions (6), (11) and (12) (sessions , , ) are disconnected from one of their destinations, which they are because one of these destinations is to the right of supernode u.

Remove all edges to the left of supernode u because the nodes to the left are not the sources of the sessions (13) (sessions ).

Test if the sessions (13) are disconnected from one of their destinations, which they are.

Since the algorithm completes successfully, the PdE bound (almost) gives inequality (14), but with

replacing

. The other inequality,

i.e., the one with

replacing

follows by choosing

with all the traffic sessions (6)–(13) except for (6), and by modifying

so that the edges to the left of supernode

u are removed first, and then the edges to the right.

Figure 3.

Network at supernode u after the PdE bound has removed the edges , , and . The session messages are tested in the order: , , , then , , , and finally .

Figure 3.

Network at supernode u after the PdE bound has removed the edges , , and . The session messages are tested in the order: , , , then , , , and finally .

3. Achievable Rates with Broadcast

We separate channel and network coding, which sounds simple enough. However, every BC receiver has side information about some of the messages being transmitted, so we will need the methods of [

6]. We further use the theory in [

5] to describe our achievable rate region.

We begin by having each node

combine

and

into the message

by which we mean the same operation as in (26): the smaller-rate message bits are XORed with a corresponding number of bits of the larger-rate message. The remaining larger-rate message bits are appended so that

has rate

. The message (37) is sent to node

together with the remaining messages received at node

. As a result, we must satisfy the bound (14).

The bits arriving at node

are (37) and (8)–(13). Bits

are removed at node

since this node is their final destination. The bits (37) and (8)–(9) and (11) must be broadcast to both nodes

and

. The remaining bits

and

are destined (or dedicated) for the right and left only, respectively. However, we know from information theory for broadcast channels [

7] that it can help to broadcast parts of these dedicated messages to both receivers. So we split

and

into two parts each, namely the respective

and

where

and

are broadcast to both nodes

and

. The rates of

and

are the respective

and

, and similarly for

and

. We choose a joint distribution

and generate a codebook of size

with length-

n codewords

by choosing every letter of every codeword independently using

.

We next choose “binning" rates and . For every , we choose length-n codewords by choosing the ith letter of via the distribution where is the ith letter of . We label with the arguments of , , and a “bin” index from . Similarly, for every we generate length-n codewords generated via and label with the arguments of , , and a “bin” index from .

Next, the encoder tries to find a pair of bin indices such that

is jointly typical according to one’s favorite flavor of typicality. Using standard typicality arguments (see, e.g., [

5]) a typical triple exists with high probability if

n is large and

Once this triple is found, we transmit a length-

n signal

that is generated via

for

.

The receivers use joint typicality decoders to recover their messages. They further use their knowledge (or side-information) about some of the messages. The result is that decoding is reliable if

n is large and if the following rate constraints are satisfied (see [

5,

6]):

Finally, we use Fourier–Motzkin elimination (see [

5]) to remove

,

,

,

,

, and

from the above expressions and obtain the following result.

Theorem 2 An achievable rate region for a line network with broadcast channels is given by the boundsfor any choice of and for all u, and where forms a Markov chain for all u. Remark 3 The bound (43) is the same as (14).

Remark 4 The bounds (44)–(48) are similar to the bounds of [5, Theorem 5]. A few rates are “missing” because nodes and know and , respectively, when decoding. Example 3 Consider for which we have the sessions (17)–(22). The inequalities of Theorem 2 areObserve that the channels from node to node , and node to node , are memoryless channels with capacities and , respectively. In fact, from (49) and (51) it is easy to see that we may as well choose , , , and as constants. Moreover, we should choose and , and then choose the input distributions so that and . The inequalities (44)–(48) at node correspond to Marton’s region [10] (Section 7.8) for broadcast channels including a common rate. We will see in the next section that if we specialize to the model of [2] then only the bounds (43)–(45) remain at node 2 because the bounds (46)–(48) are redundant.