A Conceptual Examination about the Correlates of Psychological Capital (PsyCap) among the Saudi Arabian Workforce

Abstract

:1. Introduction

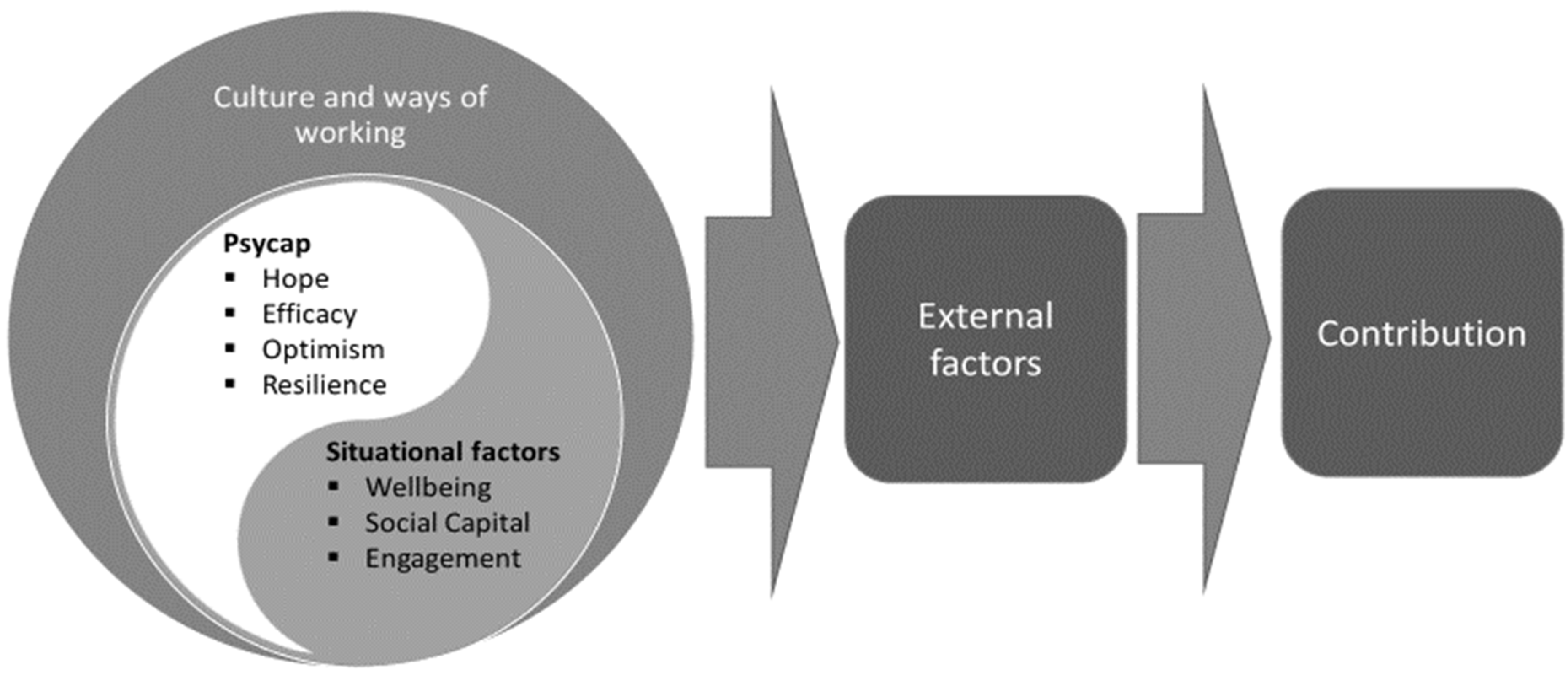

2. Literature Review

2.1. Constructs Used for the Study

2.1.1. Psychological Capital (PsyCap)

“an individual’s positive psychological state of development that is characterized by: having confidence (self-efficacy) to take on and put in the necessary effort to succeed at challenging tasks; making a positive attribution (optimism) about succeeding now and in the future; persevering toward goals and, when necessary, redirecting paths to goals (hope) in order to succeed; and when beset by problems and adversity, sustaining and bouncing back and even beyond (resilience) to attain success.”

2.1.2. Subjective Well-Being

2.1.3. Social Capital (SC)

2.1.4. Engagement

2.1.5. Cultural Considerations

3. Theoretical Underpinnings

4. The Case for Further Research

5. Implications

5.1. Theoretical Implications

5.2. Practical Implications

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Abbas, Muhammad, and Usman Raja. 2011. Impact of Psychological Capital Innovative Performance and Job stress. In 15th International Business Research Conference (Ref No. 449). Melbourne: World Business Institute. [Google Scholar]

- Abbas, Muhammad, Usman Raja, Wendy Darr, and Dave Bouckenooghe. 2012. Combined effects of perceived politics and psychological capital on job satisfaction, turnover intentions, and performance. Journal of Management 40: 1813–30. Available online: https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206312455243 (accessed on 20 March 2021). [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Abubakar, Mohammed A., Taraneh Foroutan, and Khaled Jamal Megdadi. 2019. An integrative review: High-performance work systems, psychological capital and future time perspective. International Journal of Organizational Analysis 27: 1093–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agourram, Hafid. 2009. The quest for Information Systems success in Saudi Arabia. A case study. Journal of Global Management Research, 51–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Shehri, M., P. McLaughlin, A. Al-Ashaab, and R. Hamad. 2017. The impact of organizational culture on employee engagement in Saudi banks. Journal of Human Resources Management Research 1: 1–23. Available online: https://doi.org/10.5171/2017.761672 (accessed on 20 March 2021). [CrossRef]

- Aljammaz, Mohammed, Tsung-Hsien Wang, and Chengzhi Peng. 2019. Understanding occupant behaviour in Islamic homes to close the gap in building performance simulation: A case study of houses in Riyadh. In Proceedings of the Building Simulation 2019: 16th Conference of IBPSA, Rome, Italy, September 2–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alkahtani, Hend K., Ray Dawson, and Russel Lock. 2013. The impact of culture on Saudi Arabian information systems security. In Proceedings of the 21st International Conference on Software Quality Management (SQM 2013). Edited by E. Georgiadou, M. Ross and G. Staples. Southampton: Quality Comes of Age, pp. 201–10. [Google Scholar]

- AlSheddi, Mona, Sophie Russell, and Peter Hegarty. 2020. How does culture shape our moral identity? Moral foundations in Saudi Arabia and Britain. European Journal of Social Psychology 50: 97–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Shehry, Abdullah, Simon Rogerson, N. Ben Fairweather, and Mary Prior. 2006. The motivations for change towards e-government adoption: Case studies from Saudi Arabia. Paper presented at the eGovernment Workshop 06 (eGOV06), Brunel University, Uxbridge, London, September 11. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Yahya, Khalid O. 2008. Power-Influence in Decision Making, Competence Utilization, and Organizational Culture in Public Organizations: The Arab World in Comparative Perspective. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory 19: 385–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antonovsky, Aaron. 1979. Health, Stress, and Coping. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Avey, James B., Tara S. Wernsing, and Fred Luthans. 2008a. Can positive employees help positive organizational change? Impact of psychological capital and emotions on relevant attitudes and behaviors. The Journal of Applied Behavioral Science 44: 48–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Avey, J.B., L.W. Hughes, S.M. Norman, and K.W. Luthans. 2008b. Using positivity, transformational leadership and empowerment to combat employee negativity. Leadership & Organization Development Journal 29: 110–26. Available online: https://doi.org/10.1108/01437730810852470 (accessed on 20 March 2021).

- Avey, J.B., B.J. Avolio, C.D. Crossley, and F. Luthans. 2009. Psychological ownership: Theoretical extensions, measurement and relation to work outcomes. Journal of Organizational Behavior 30: 173–91. Available online: https://doi.org/10.1002/job.583 (accessed on 20 March 2021). [CrossRef]

- Avey, James B., Fred Luthans, and Carolyn M. Youssef. 2010a. The additive value of positive psychological capital in predicting work attitudes and behaviors. Journal of Management 36: 430–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Avey, James B., Fred Luthans, Ronda M. Smith, and Noel F. Palmer. 2010b. Impact of positive psychological capital on employee well-being over time. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology 15: 17–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Avey, James B., James L. Nimnicht, and Nancy G. Pigeon. 2010c. Two field studies examining the association between positive psychological capital and employee performance. Leadership & Organization Developmental Journal 31: 384–401. [Google Scholar]

- Avolio, Bruce J., and Fred Luthans. 2006. The High Impact Leader: Moments Matter for Accelerating Authentic Leadership Development. New York: McGraw-Hill. [Google Scholar]

- Bagozzi, Richard P. 2007. The Legacy of the Technology Acceptance Model and a Proposal for a Paradigm Shift. Journal of the Association for Information Systems 8: 244–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, Wane E., and Jane E. Dutton. 2006. Enabling positive social capital in organizations. In Exploring Positive Relationship at Work: Building a Theoretical and Research Foundation. Edited by J. Dutton and F. Ragins. Mahwah: Lawrence Erlbaum Inc., pp. 325–45. [Google Scholar]

- Bakker, A.B., and J.D. De Vries. 2020. Job demands–resources theory and self-regulation: New explanations and remedies for job burnout. Anxiety Stress Coping 34: 1–21. Available online: https://doi.org/10.1080/10615806.2020.1797695 (accessed on 20 March 2021). [CrossRef]

- Bakker, Arnold B., and Evangelia Demerouti. 2017. Job demands–resources theory: Taking stock and looking forward. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology 22: 273–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bakker, A.B., and E. Demerouti. 2018. Multiple levels in job demands-resources theory: Implications for employee well-being and performance. In Handbook of Wellbeing. Edited by E. Diener, S. Oishi and L. Tay. Salt Lake City: DEF Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Bakker, A.B., and W.G.M. Oerlemans. 2019. Daily job crafting and momentary work engagement: A self-determination and self-regulation perspective. Journal of Vocational Behavior 112: 417–30. Available online: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2018.12.005 (accessed on 20 March 2021). [CrossRef]

- Bakker, Arnold B., and Wilmar B. Schaufeli. 2015. Work engagement. In Wiley Encyclopedia of Management. Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd., pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baltes, Boris B., Kevin Wynne, Mgrdich Sirabian, Daniel Krenn, and Annet Lange. 2014. Future time perspective, regulatory focus, and selection, optimization, and compensation: Testing a longitudinal model. Journal of Organizational Behavior 35: 1120–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baluku, Martin M., Eriphase N. Mugabi, Joyce Nansamba, Leonsio Matagi, Peter Onderi, and Kathleen Otto. 2020. Psychological capital and career outcomes among final year University students: The mediating role of career engagement and perceived employability. International Journal of Applied Positive Psychology 6: 55–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, Albert. 2020. Social cognitive theory: An agentic perspective. Psychology: The Journal of the Hellenic Psychological Society 12: 313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basinska, B. A., and Malgorzata Rozkwitalska. 2020. Psychological capital and happiness at work: The mediating role of employee thriving in multinational corporations. Current Psychology. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben-Hador, B. 2016. Coaching executives as tacit performance evaluation: A multiple case study. Journal of Management Development 35: 75–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben-Hador, Batia. 2019. Social capital levels, gossip and employee performance in aviation and shipping companies in Israel. International Journal of Manpower 40: 1036–55. Available online: https://doi.org/10.1108/ijm-12-2017-0321 (accessed on 25 March 2021). [CrossRef]

- Benozzo, Angelo, Mirka Koro-Ljungberg, and Adamo Ssergia. 2019. Would you prefer not to? Resetting/resistance across literature, culture, and organizations. Culture and Organization 25: 131–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bjerke, Bjorn, and Abdulraheem Al-Meer. 1993. Culture’s consequences: Management in Saudi Arabia. Leadership and Organization Development Journal 14: 30–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boston Consulting Group. 2011. High-performance organizations: The Secrets of their Success. [Google Scholar]

- Bourdieu, Pierre. 1983. Forms of social capital. In Handbook of Theory and Research for the Sociology of Education. Edited by J. C. Richards. New York: Greenwood Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bourdieu, Pierre. 1986. Handbook of Theory and Research for the Sociology of Education. Edited by J. Richardson. Westport: Greenwood. [Google Scholar]

- Bowen, Wayen H. 2008. The History of Saudi Arabia. Westport: Greenwood Press. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell, Angus, Philip E. Converse, and Willard L. Rodgers. 1976. The Quality of American Life: Perceptions, Evaluations, and Satisfactions. New York: Russell Sage Foundation. [Google Scholar]

- Carmona-Halty, Marcos, Marisa Salanova, and Wilmar B. Schaufeli. 2019. Good relations, good performance: The mediating role of psychological capital: A three-wave study among students. Frontiers in Psychology: Section Organizational Psychology 10: 306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Çelik, Mazlum. 2018. The Effect of Psychological Capital Level of Employees on Workplace Stress and Employee Turnover Intention. Innovar 28: 67–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Central Department of Statistics & Information. 2010. Available online: https://www.stats.gov.sa/en/73 (accessed on 15 January 2021).

- Çetin, F., and N. Basim. 2011. The role of resilience in the attitudes of job satisfaction and organizational commitment. ISGUC, The Journal of Industrial Relations and Human Resources 13: 79–94. Available online: https://doi.org/10.4026/1303-2860.2011.0184.x (accessed on 20 March 2021).

- Chazon, Timothy L. 2009. Social Capital: Relationship Between Social Capital and Teacher Job Satisfaction Within a Learning Organization. Boiling Springs: GardnerWebb University. [Google Scholar]

- Choi, Yongduk, and Dongseop Lee. 2014. Psychological capital, Big Five traits, and employee outcomes. Journal of Managerial Psychology 29: 122–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cirule, Iveta, and Janis Prusis. 2018. Social capital and social support. 19th International Scientific Conference “Economic Science for Rural Development 2018”. Rural Development and Entrepreneurship Production and Co-operation in Agriculture. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cozzarelli, Catherine. 1993. Personality and self-efficacy as predictors of coping with abortion. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 65: 1224–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Culbertson, Satoris S., Clive J. Fullagar, and Maura J. Mills. 2010. Feeling good and doing great: The relationship between psychological capital and well-being. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology 15: 421–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Daniels, Kevin. 2000. Measures of five aspects of affective well-being at work. Human Relations 53: 275–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Datu, Jesus A., Ronnel B. King, and Jana P. Valdez. 2016. Psychological capital bolsters motivation, engagement, and achievement: Cross-sectional and longitudinal studies. The Journal of Positive Psychology 13: 260–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Waal, Andre. 2007. The characteristics of a high-performance organization. Business Strategy Series 8: 179–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Diener, Ed. 1984. Subjective well-being. Psychological Bulletin 95: 542–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diener, Ed. 2000. Subjective well-being: The science of happiness and a proposal for a national index. American Psychologist 55: 34–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esmail, Hanaa. A. 2019. The impact of cultural diversity on economic development in Saudi Arabia—Empirical study. Journal of Sustainable Development 12: 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Firouzbakht, Mozhgan, Aram Tirgar, Abbas Ebadi, Hamid S. Nia, Tuula Oksanen, Anne Kouvonen, and Mohammed E. Riahi. 2018. Psychometric properties of Persian version of the short-form workplace social capital questionnaire for female health workers. International Journal of Occupational & Environmental Medicine 9: 184–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fried, Eiko I. 2017. What are psychological constructs? On the nature and statistical modelling of emotions, intelligence, personality traits and mental disorders. Health Psychology Review 11: 130–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galunic, Charles, Gokhan Ertug, and Martin Gargiulo. 2012. The positive externalities of social capital: Benefiting from senior brokers. Academy of Management Journal 55: 1213–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gannon, Brenda, and Jennifer Roberts. 2018. Social capital: Exploring the theory and empirical divide. Empirical Economics 58: 899–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gautam, Vikas, Sombala Ningthoujam, and Teena Singh. 2019. Impact of Psychological Capital on Well-Being of Management Students. Theoretical Economics Letters 9: 1246–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gilson, L.L., M.T. Maynard, N.C.J. Young, M. Vartiainen, and M. Hakonen. 2015. Virtual teams research: 10 Years, 10 themes, and 10 opportunities. Journal of Management 41: 1313–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Goleman, Daniel. 2004. What makes a leader? Harvard Business Review 82: 82–91. [Google Scholar]

- González, Pablo A., Francisca Dussaillant, and Esteban Calvo. 2021. Social and individual subjective wellbeing and capabilities in Chile. Frontiers in Psychology 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorgievski, Marjan Jonathan, Jonathon R. B. Halbesleben, and Arnold B. Bakker. 2011a. Expanding the Boundaries of Psychological Resource Theories. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology 84: 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorgievski, M.J., M.E. Ascalon, and U. Stephan. 2011b. Small business owners’ success criteria, a values approach to personal differences. Journal of Small Business Management 49: 207–32. Available online: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-627x.2011.00322.x (accessed on 20 March 2021). [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Halbesleben, Jonathan R. B., Neveu Jean-Pierre, C. Paustain-Underdahl Samantha, and Westman Mina. 2014. Getting to the ‘COR’: Understanding the Role of Resources in Conservation of Resources Theory. Journal of Management 40: 1334–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haybron, Daniel M. 2008. Philosophy and the science of subjective well-being. In The Science of Subjective Well-Being. Edited by M. Eid and R. J. Larsen. New York: The Guilford Press, pp. 17–43. [Google Scholar]

- Helliwell, John F., and Robert D. Putnam. 2004. The social context of well-being. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B 359: 1435–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herdem, Dilek Ö. 2019. The effect of psychological capital on motivation for individual instrument: A study on University students. Universal Journal of Educational Research 7: 1402–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, Carole E., Karen D. Loch, Detmar W. Straub, and Kamal El-Sheshai. 1998. A qualitative assessment of Arab culture and information technology transfer. Journal of Global Information Management 6: 29–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobfoll, Stevan E. 1989. Conservation of resources: A new attempt at conceptualizing stress. American Psychologist 44: 513–24. Available online: https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066x.44.3.513 (accessed on 20 March 2021). [CrossRef]

- Hobfoll, Stevan E. 2002. Social and psychological resources and adaptation. Review of General Psychology 6: 307–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodges, Timothy D. 2010. An experimental Study of the Impact of Psychological Capital on Performance, Engagement, and the Contagion Effect. Dissertations thesis, College of Business Administration, University of Nebraska, Lincoln, NE, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Hofstede, Geert. 1998. Masculinity and Femininity: The Taboo Dimension of National Cultures. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Hofstede, Geet, Gert J. Hofstede, and Michael Minkov. 2010. Cultures and Organizations: Software of the Mind: Intercultural Cooperation and Its Importance for Survival. New York: McGraw-Hill. [Google Scholar]

- Hommerich, Carola, and Tim Tiefenbach. 2017. Analyzing the relationship between social capital and subjective well-being: The mediating role of social affiliation. Journal of Happiness Studies 19: 1091–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Qiao, Wilmar B. Schaufeli, T. W. Taris, van David. J. Hessen, J. Hakanen, Marisa Salanova, and Akihitao Shimazu. 2014. “East is East and West is West and never the twain shall meet” Work engagement and workaholism across Eastern and Western cultures. Journal Behavioral and Social Science 1: 6–24. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, Xiaoyu, K. Jiang, and Anil Verma. 2015. Do changes in high-performance work systems pay off? A longitudinal investigation of dynamic fit. In Academy of Management Proceedings. New York: Briarcliff Manor, vol. 2015, p. 12181. [Google Scholar]

- Idris, Abdallah M., and Michelle Manganaro. 2017. Relationships between psychological capital, job satisfaction, and organizational commitment in the Saudi oil and petrochemical industries. Journal of Human Behavior in the Social Environment 27: 251–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, M. Kamrul, Juan Merlo, Ichiro Kawachi, Martin Lindström, and Ulf-G Gerdtham. 2006. Social capital and health: Does egalitarianism matter? A literature review. International Journal for Equity in Health, 5. Available online: https://doi.org/10.1186/1475-9276-5-3 (accessed on 20 March 2021). [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kabasakal, Hayat, and Muzaffer Bodur. 2002. Arabic cluster: A bridge between East and West. Journal of World Business 37: 40–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahn, William A. 1990. Psychological conditions of personal engagement and disengagement at work. Academy of Management Journal 33: 692–724. [Google Scholar]

- Kamarudin, N Norafisha, Siew H. Yen, and Kok F. See. 2020. Social capital and subjective well-being in Malaysia. Malaysian Journal of Social Sciences and Humanities (MJSSH) 5: 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kashdan, Todd B., Robert Biswas-Diener, and Laura A. King. 2008. Reconsidering happiness: The costs of distinguishing between hedonics and Eudaimonia. The Journal of Positive Psychology 3: 219–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kašpárková, Ludmila, Martin Vaculík, Jakub Procházka, and Wilmar B. Schaufeli. 2018. Why resilient workers perform better: The roles of job satisfaction and work engagement. Journal of Workplace Behavioral Health 33: 43–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotter, John P., and James L. Heskett. 2011. Corporate Culture and Performance. New York: Free Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kuznetsova, Natalia V., and Elena V. Matveeva. 2015. Accumulation of social capital as a competitive advantage of companies which are loyal to the principles of corporate citizenship. International Journal of Economics and Financial Issues 5: 68–72. [Google Scholar]

- Larson, Milan, and Fred Luthans. 2006. Potential added value of psychological capital in predicting work attitudes. Journal of Leadership and Organizational Studies 13: 44–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larson, Milan D., Steven M. Norman, Larry W. Hughes, and James B. Avey. 2013. Psychological capital: A new lens for understanding employee fit and attitudes. International Journal of Leadership Studies 8: 28–43. [Google Scholar]

- Law, Kenneth S., Chi-Sum Wong, and William H. Mobley. 1998. Toward a taxonomy of multidimensional constructs. Academy of Management Review 23: 741–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leana, Carrie R., and Harry J. Van Buren. 1999. Organizational Social Capital and Employment Practices. Academy of Management Review 24: 538–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Tingyi, Wei Liang, Zhijian Yu, and Xin Dang. 2020. Analysis of the influence of entrepreneur’s psychological capital on employee’s innovation behavior under leader-member exchange relationship. Frontiers in Psychology, 11. Available online: https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.01853 (accessed on 20 March 2021). [CrossRef]

- Liang, Zengxian, Hui Luo, and Chenxi Liu. 2020. The concept of subjective well-being: Its origins an application in tourism research: A critical review with reference to China. Tourism Critiques: Practice and Theory. ahead-of-print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Nan. 2001. Social Capital: A Theory of Social Structure and Action. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- López-Núñez, M. Inmaculada, Susana Rubio-Valdehita, Eva M. Diaz-Ramiro, and Marta E. Aparicio-García. 2020. Psychological capital, workload, and burnout: What’s new? The impact of personal accomplishment to promote sustainable working conditions. Sustainability 12: 8124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorenz Timo, Clemens Beer, Jan Pütz, and Kathrin Heinitz. 2016. Measuring Psychological Capital: Construction and Validation of the Compound PsyCap Scale (CPC-12). PLoS ONE 11: e0152892. Available online: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0152892 (accessed on 20 March 2021). [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Luthans, Fred. 2002. Positive organizational behavior: Developing and managing psychological strengths. Academy of Management Executive 16: 57–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luthans, Fred, and Carolyn M. Youssef. 2004. Human, Social, and Now Positive Psychological Capital Management: Investing in People for Competitive Advantage. Organizational Dynamics 33: 143–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luthans, Fred, and Carolyn M. Youssef. 2007. Emerging positive organizational behavior. Journal of Management 33: 321–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Luthans, Fred, and Carolyn M. Youssef-Morgan. 2017. Psychological capital: An evidence-based positive approach. Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior 4: 339–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Luthans, Fred, Carolyn M. Youssef, and Bruce J. Avolio. 2007a. Psychological Capital: Developing the Human Competitive Edge. New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Luthans, Fred, Bruce J. Avolio, James B. Avey, and Steven M. Norman. 2007b. Positive Psychological Capital: Measurement and Relationship with Performance and Satisfaction. Personnel Psychology 60: 541–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Luthans, Fred, James B. Avey, Rachel C. Smith, and Weixing Li. 2008. More evidence on the value of Chinese workers’ psychological capital: A potentially unlimited competitive resource? International Journal of Human Resource Management 19: 818–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Macey, William H., and Benjamin Schneider. 2008. The meaning of employee engagement. Industrial and Organizational Psychology 1: 3–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacLeod, David, and Nita Clarke. 2009. Engaging for Success: Enhancing Performance through Employee Engagement. London: Office of Public Sector Information. [Google Scholar]

- McMurray, Adela J., Andrew Pirola-Merlo, James C. Sarros, and Mohammed M. Islam. 2010. Leadership, climate, psychological capital, commitment and well-being in a non-profit organization. Leadership & Organization Development Journal 31: 436–57. [Google Scholar]

- Milana, Elias, and Issa Maldaon. 2015. Social Capital: A Comprehensive Overview at Organizational Context. Periodica Polytechnica Social and Management Sciences 23: 133–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mostafa, A. Mohammed Sayed. 2017. High-performance HR practices, positive affect and employee outcomes. Journal of Managerial Psychology 32: 163–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Nahapiet, Janine, and Sumantra Ghoshal. 1998. Social Capital, Intellectual Capital, and The Organizational Advantage. Academy of Management Review 23: 242–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norman, Steven M., Bruce J. Avolio, and Fred Luthans. 2010. The impact of positivity and transparency on trust in leaders and their perceived effectiveness. The Leadership Quarterly 21: 350–364. Available online: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.leaqua.2010.03.002 (accessed on 20 March 2021). [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ochsenwald, William, and Sydney N. Fisher. 2010. The Middle East: A History. Boston: McGraw Hill. [Google Scholar]

- Oishi, Shigehiro. 2018. Culture and subjective well-being: Conceptual and measurement issues. In Handbook of Well-Being. Edited by E. Diener, S. Oishi and L. Tay. Salt Lake City: DEF Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Parent, Jane D., and Kathi J. Lovelace. 2018. Employee engagement, positive organizational culture and individual adaptability. On the Horizon 26: 206–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parfit, Derek. 1984. Reasons and Persons. New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Parker, Andrew, Daniel S. Halgin, and Stephen P. Borgatti. 2015. Dynamics of social capital: Effects of performance feedback on network change. Organization Studies 37: 375–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Peterson, A. Townsend, Jorge Soberón, Richard G. Pearson, Robert P. Anderson, Enrique Martínez-Meyer, Miguel Nakamura, and Miguel B. Araújo. 2011. Ecological Niches and Geographic Distributions. Princeton: Princeton University Press, p. 314. [Google Scholar]

- Portes, Alejandro. 1998. Social capital: Its origins and applications in modern sociology. Annual Review of Sociology 24: 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Putnam, Robert D. 2001. Bowling Alone: The Collapse and Revival of American Community. New York: Simon and Schuster Paperbacks. [Google Scholar]

- Qi, Yaning. 2020. Influence of psychological capital construction on human resource management from the perspective of employee engagement. Revista Argentina De Clinica Psicologica 29: 530–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raza, Basharat, Alia Ahmed, Sabahat Zubair, and Abdul Moueed. 2019. Linking workplace deviance and abusive supervision: Moderating role of positive psychological capital. International Journal of Organizational Leadership 8: 95–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Read, Emily A. 2014. Workplace social capital in nursing: An evolutionary concept analysis. Journal of Advances in Nursing 70: 997–1007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rini, Christine K., Christine Dunkel-Schetter, Pathik D. Wadhwa, and Curt A. Sandman. 1999. Psychological adaptation and birth outcomes: The role of personal resources, stress, and sociocultural context in pregnancy. Health Psychology 18: 333–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, Richard M., and Edward L. Deci. 2000. Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. American Psychologist 55: 68–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryff, Carol D. 1989. Happiness is everything, or is it? Explorations on the meaning of psychological well-being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 57: 1069–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryff, Carol. D., and Corey Lee M. Keyes. 1995. The structure of psychological well-being revisited. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 69: 719–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sabaitytė, Eglė, and Aistė Diržytė. 2016. Psychological Capital, Self-Compassion, and Life Satisfaction of Unemployed Youth. International Journal of Psychology: A Biopsychosocial Approach 19: 49–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sagie, Abraham, and Zeynep Aycan. 2003. A cross-cultural analysis of participative decision-making in organizations. Human Relations 56: 453–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saleem, Muniba, M.E. Wojcieszak, I. Hawkins, M. Li, and S. Ramasubramanian. 2019. Social identity threats: How media and discrimination affect Muslim Americans’ identification as Americans and trust in the U.S. government. Journal of Communication 69: 214–236. Available online: https://doi.org/10.1093/joc/jqz001 (accessed on 20 March 2021). [CrossRef]

- Sameer, Yomna M. 2018. Innovative behavior and psychological capital: Does positivity make any difference? Journal of Economics and Management 32: 75–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santisi, Giuseppe, Ernesto Lodi, Paola Magnano, Rita Zarbo, and Andrea Zammitti. 2020. Relationship between psychological capital and quality of life: The role of courage. Sustainability 12: 5238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sato, Yoshimichi. 2013. Social capital. Sociopedia.isa, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaufeli, Wilmar B., and Arnold B. Bakker. 2004. Job demands, job resources, and their relationship with burnout and engagement. Journal of Organizational Behavior 25: 293–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Schein, Edgar H. 1996. Culture: The Missing Concept in Organization Studies. Administrative Science Quarterly 41: 229–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahnawaz, Ghazi M., and Mohammed H. Jafri. 2009. Psychological Capital as Predictors of Organizational Commitment and Organizational Citizenship Behaviour. Journal of the Indian Academy of Applied Psychology 35: 78–84. [Google Scholar]

- Simons, Janet C., and Johanna H. Buitendach. 2013. Psychological capital, work engagement and organizational commitment amongst call center employees in South Africa. SA Journal of Industrial Psychology 39: 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sironi, Emiliano. 2019. Job satisfaction as a determinant of employees’ optimal well-being in an instrumental variable approach. Quality & Quantity 53: 1721–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sleator, Roy D. 2020. An alternative viewpoint—Comment on Prescott and bland Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 1407. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 17: 5004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snyder, Charles R., Cheri Harris, John R. Anderson, Sharon A. Holleran, Lori M. Irving, Sandra T. Sigmon, Lauren Yoshinobu, June Gibb, Charyle Langelle, and Pat Harney. 1991. The will and the ways: Development and validation of an individual-differences measure of hope. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 60: 570–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Yu, Peng Peng, and Guangtao Yu. 2020. I would speak up to live up to your trust: The role of psychological safety and regulatory focus. Frontiers in Psychology 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Soni, Kumari, and Ravi Rastogi. 2019. Psychological Capital Augments Employee Engagement. Psychological Studies 64: 465–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stajkovic, Alexander D., and Fred Luthans. 1998. Social cognitive theory and self-efficacy: going beyond traditional motivational and behavioral approaches. Organizational Dynamics 26: 62–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sulphey, M. MohammedIsmail. 2019. The Concept of Workplace Identity, its evolution, antecedents and development, International Journal of Environment. Workplace and Employment 5: 151–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sulphey, M. MohammedIsamil, and Nasser S. Al-Kahtani. 2017. Economic security and sustainability through social entrepreneurship: The current Saudi scenario. Journal of Security and Sustainability Issues 6: 479–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sulphey, M. MohammedIsmail, and Nasser S. Al-Kahtani. 2018. Academic Excellence of Business Graduates through Nudging: Prospects in Saudi Arabia. International Journal of Innovation and Learning 24: 98–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sumner, L. Wayne. 1996. Welfare, Happiness, and Ethics. New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, W. 2015. Dao and eudaimonia: Another dialogue between Aristotle and Xunzi’s ethics. Fudan Journal (Social Sciences) 6: 86–95. [Google Scholar]

- Sweetman, David S., Fred Luthans, James B. Avey, and Brett C. Luthans. 2011. Relationship between positive psychological capital and creative performance. Canadian Journal of Administrative Sciences 28: 4–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Szreter, Simon, and Michael Woolcock. 2004. Health by association? Social capital, social theory, and the political economy of public health. International Journal of Epidemiology 33: 650–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tantardini, Michele, and Alexadner Kroll. 2015. The role of organizational social capital in performance management. Public Performance & Management Review 39: 83–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thoits, Paggy A. 1994. Stressors and problem solving: The individual as a psychological activist. Journal of Health and Social Behavior 35: 143–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- UNDP. 2019. Inequalities in Human Development in the 21st Century Briefing Note for Countries on the 2019 Human Development Report Saudi Arabia, Human Development Report 2019. Available online: http://www.hdr.undp.org/sites/all/themes/hdr_theme/country-notes/SAU.pdf (accessed on 12 March 2021).

- Uphoff, Norman. 1999. Understanding social capital: Learning from the analysis and experience of participation. In Social Capital: A Multi-faceted Perspective. Edited by P. Dasgaputa and I. Serageldin. Washington: The World Bank. [Google Scholar]

- Van de Ven, Andrew H., and Marshall Scott Poole. 1989. Methods for Studying Innovation Processes. Edited by Andrew H. Van de Ven, H.L. Angle and Marshall Scott Poole. New York: Research on the Management of Innovation, Harper & Row, pp. 31–54. [Google Scholar]

- Van den Heuvel, M., E. Demerouti, A. B. Bakker, J. Hetland, and W. B. Schaufeli. 2020. How do employees adapt to organizational change? The role of meaning-making and work engagement. Spanish Journal of Psychology 23: e56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vörös, Tiber, and J. Choudrie. 2011. Uncertainty Avoidance and Technology Acceptance in Emerging Economies: A Comparative Study. Paper presented at the SIG Globdev 4th Annual Conference, Shanghai, China, December 3. [Google Scholar]

- Wagner, Heinz-Theo, Daniel Beimborn, and Tim Weitzel. 2014. How social capital among information technology and business units drives operational alignment and IT business value. Journal of Management Information Systems 13: 241–72. Available online: https://doi.org/10.2753/mis0742-1222310110 (accessed on 20 March 2021). [CrossRef]

- Walumbwa, Fred O., Suzanne J. Peterson, Bruce J. Avolio, and Chad A. Hartnell. 2010. An investigation of the relationships among leader and follower psychological capital, service climate, and job performance. Personnel Psychology 63: 937–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Yanfei, Yi Chen, and Yu Zhu. 2021. Promoting innovative behavior in employees: The mechanism of leader psychological capital. Frontiers in Psychology 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warr, Peter. 1990. The measurement of well-being and other aspects of mental health. Journal of Occupational Psychology 63: 193–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waxin, Marie-France, Sandra L. Knuteson, and Aaron Bartholomew. 2020. Outcomes and Key Factors of Success for ISO 14001 Certification: Evidence from an Emerging Arab Gulf Country. Sustainability 12: 258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Weick, Karl E. 1989. Theory construction as disciplined imagination. Academy of Management Review 14: 516–31. Available online: https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.1989.4308376 (accessed on 20 March 2021). [CrossRef]

- White, Michael, and Alex Bryson. 2013. Positive employee attitudes: How much human resource management do you need? Human Relations 66: 385–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wilson, Warner R. 1967. Correlates of avowed happiness. Psychological Bulletin 67: 294–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Meling, Xing Gao, Mengqiu Cao, and Enrica Papa. 2021. Large-scale enterprises, social capital and the post-disaster development of community tourism: The case of Taoping, China. International Journal of Tourism Research. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Jia, Yan Liu, and Beth Chung. 2017. Leader psychological capital and employee work engagement. Leadership & Organization Development Journal 38: 969–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Youssef, Carolyn M., and Fred Luthans. 2007. Positive organizational behavior in the workplace: The impact of hope, optimism, and resilience. Journal of Management 33: 774–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuwono, Wisnu. 2021. Empirical analysis of intellectual capital, potential absorptive capacity, realized absorptive capacity and cultural intelligence on innovation. Management Science Letters, 1399–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Hui, Yi Zhao, Ping Zou, Yang Liu, Shuanghong Lin, Zhihong Ye, Leiwen Tang, Jing Shao, and Dandan Chen. 2020. The relationship between autonomy, optimism, work engagement and organisational citizenship behaviour among nurses fighting COVID-19 in Wuhan: A serial multiple mediation. BMJ Open 10: e039711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| No | Constructs | Definition | Author |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Hope | “Positive motivational state that is based on an interactively derived sense of successful (a) agency (goal-directed energy) and (b) pathways (planning to meet goals).” | Snyder et al. (1991, p. 287) |

| 2 | Efficacy | “The employee’s conviction or confidence about his or her abilities to mobilize the motivation, cognitive resources, or courses of action needed to successfully execute a specific task within a given context.” | Stajkovic and Luthans (1998, p. 66) |

| 3 | Optimism | “A positive outcome outlook or attribution of events, which includes positive emotions and motivation, and has the caveat of being realistic”. | (Luthans 2002a) |

| 4 | Resilience | “Positive psychological capacity to rebound, to ‘bounce back’ from adversity, uncertainty, conflict, failure, or even positive change, progress, and increased responsibility.” | (Luthans 2002a, p. 702) |

| Particulars | Description | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| SC | Dimensions (Uphoff 1999) | Structural | Involves the various roles of individuals and the rules, precedents, and procedures followed |

| Cognitive | Beliefs, attitudes, values, and norms that could affect participation in social activities | ||

| Levels (Szreter and Woolcock 2004) | Bonding SC | Involves the interactions of different individuals having similar personal/social characteristics, like similar job positions | |

| Bridging SC | Involves interactions of individuals who are different with respect to social and individual aspects, like occupational differences | ||

| Linking SC | Exchanges between individuals of various levels of power, like interactions between employees and employers | ||

| No | Variable | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Vigor | The inner power of an individual, which motivates energetic action within the workplace. |

| 2 | Dedication | Willingness to discharge individual obligations and duties, understanding their significance with a sense of enthusiasm. |

| 3 | Absorption | Enthusiasm of individuals to be involved and get happily engrossed in their respective works. |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Alkahtani, N.S.; Sulphey, M.M.; Delany, K.; Elneel Adow, A.H. A Conceptual Examination about the Correlates of Psychological Capital (PsyCap) among the Saudi Arabian Workforce. Soc. Sci. 2021, 10, 122. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci10040122

Alkahtani NS, Sulphey MM, Delany K, Elneel Adow AH. A Conceptual Examination about the Correlates of Psychological Capital (PsyCap) among the Saudi Arabian Workforce. Social Sciences. 2021; 10(4):122. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci10040122

Chicago/Turabian StyleAlkahtani, Nasser Saad, M. M. Sulphey, Kevin Delany, and Anass Hamad Elneel Adow. 2021. "A Conceptual Examination about the Correlates of Psychological Capital (PsyCap) among the Saudi Arabian Workforce" Social Sciences 10, no. 4: 122. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci10040122

APA StyleAlkahtani, N. S., Sulphey, M. M., Delany, K., & Elneel Adow, A. H. (2021). A Conceptual Examination about the Correlates of Psychological Capital (PsyCap) among the Saudi Arabian Workforce. Social Sciences, 10(4), 122. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci10040122