Handwritten Messages Boost Consumer Engagement in Food Delivery

Abstract

1. Introduction

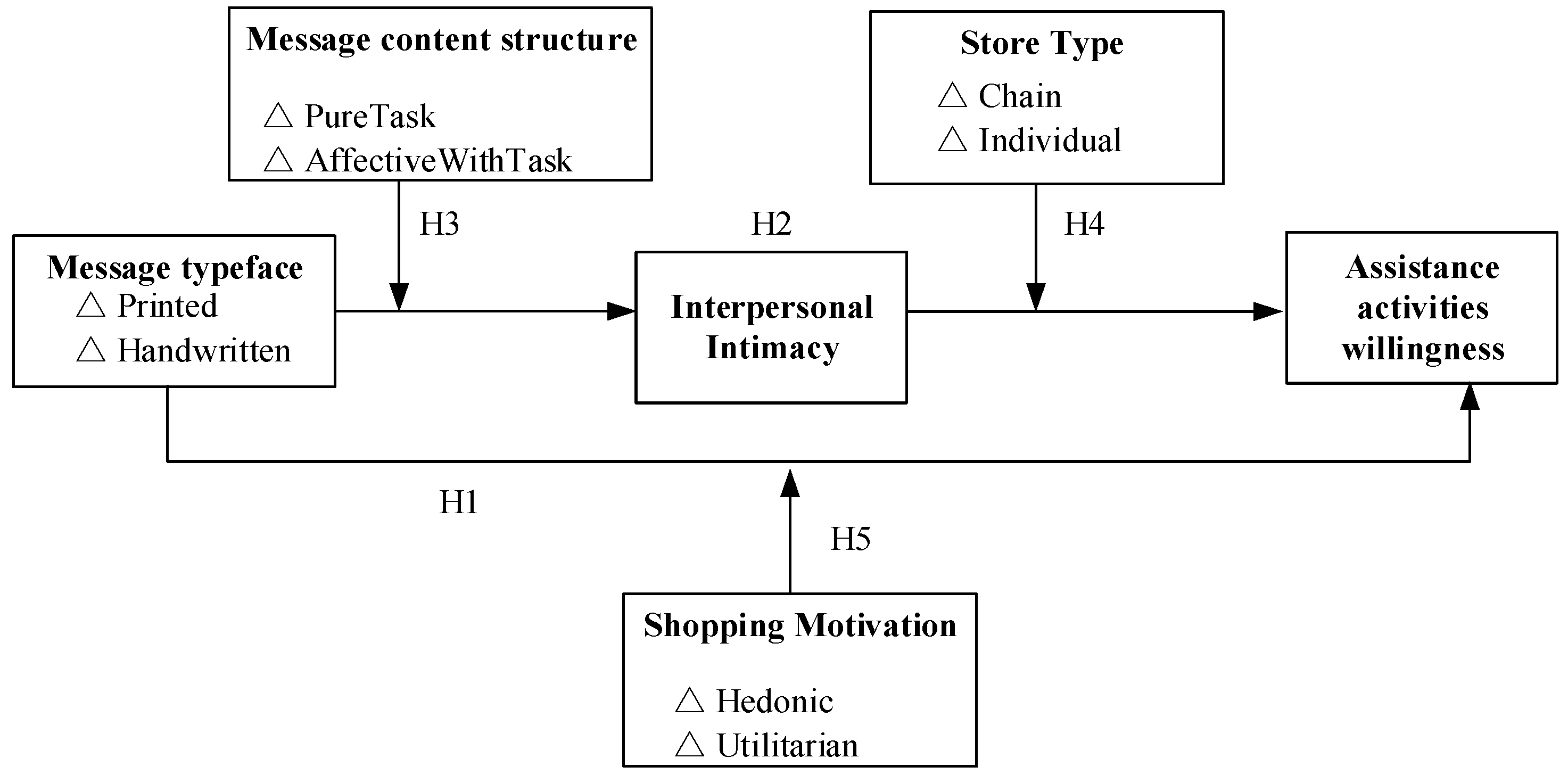

2. Literature Review and Hypothesis Development

2.1. Customer Behaviors in Online Food-Delivery Service

2.2. Message Typeface (Printed vs. Handwritten), Interpersonal Intimacy, and Customers’ Willingness to Engage in Assistance Activities

2.3. The Moderating Role of Message Content Structure

2.4. The Moderating Role of Store Type

2.5. The Moderating Role of Shopping Motivation

2.6. Conceptual Model

3. Methodology

3.1. Overview

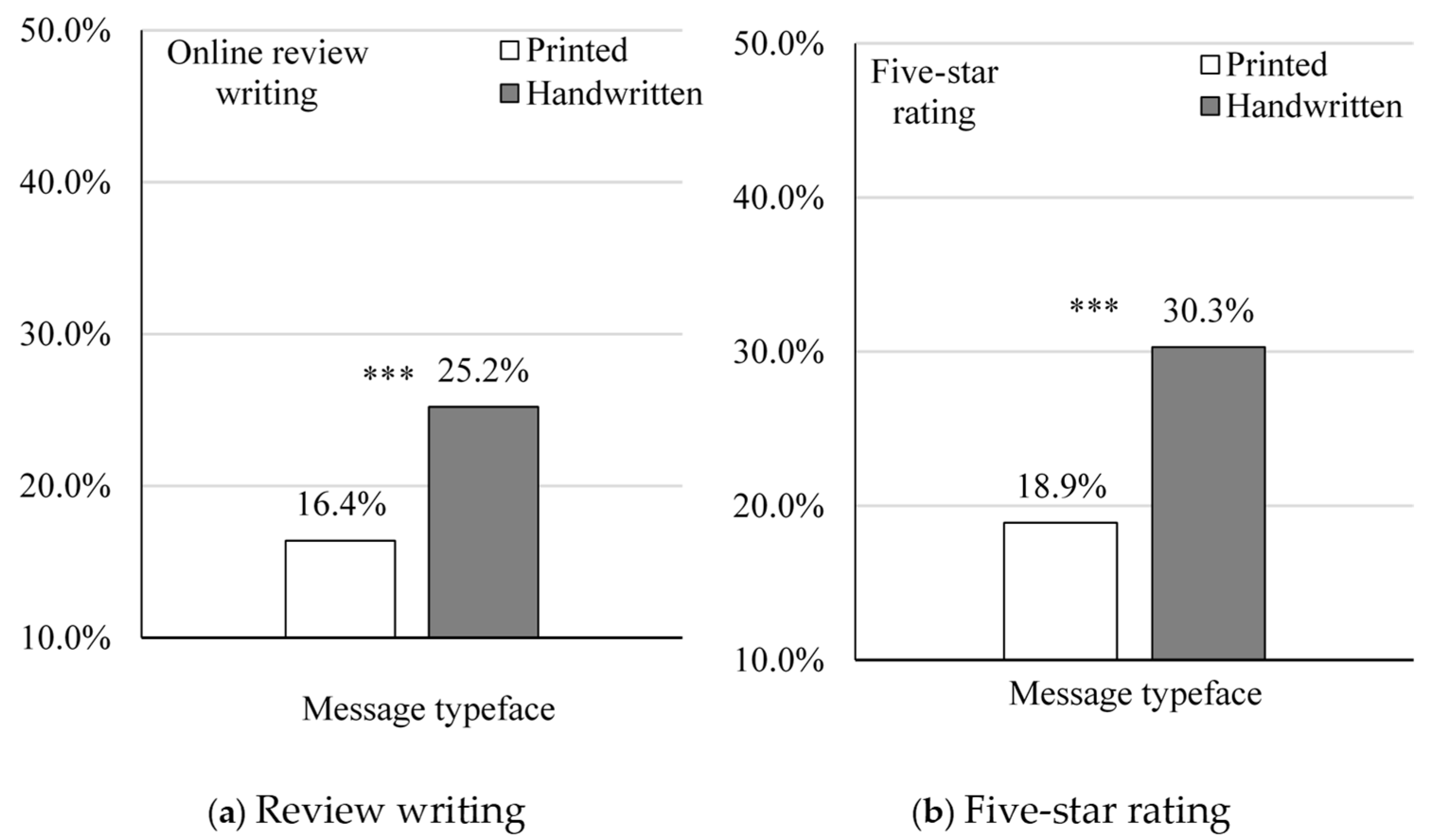

3.2. Study 1: The Main Effect of the Message Typeface (Printed vs. Handwritten)

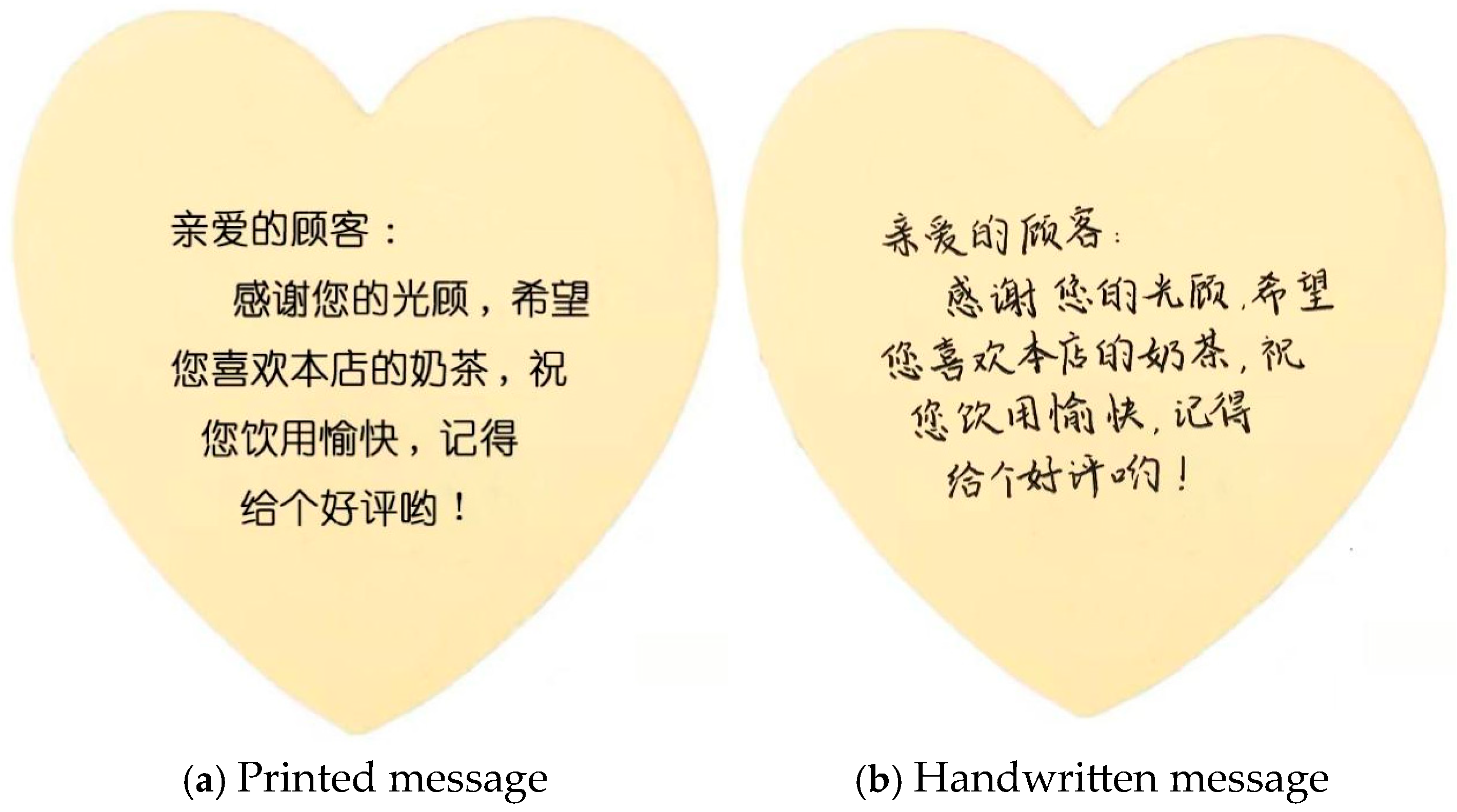

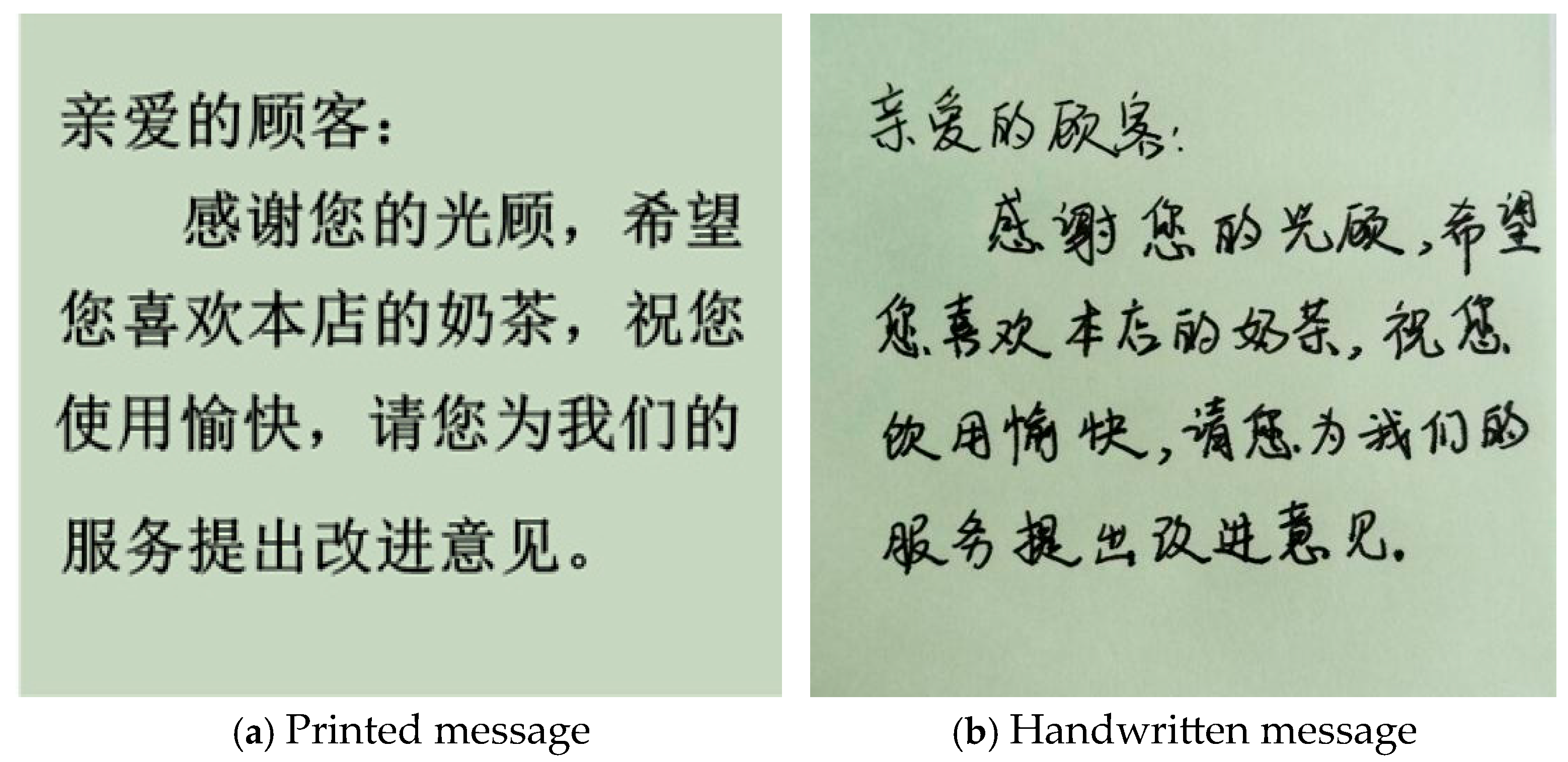

3.2.1. Study Design

3.2.2. Pretest

3.2.3. Procedures for the Main Experiment

3.2.4. Results

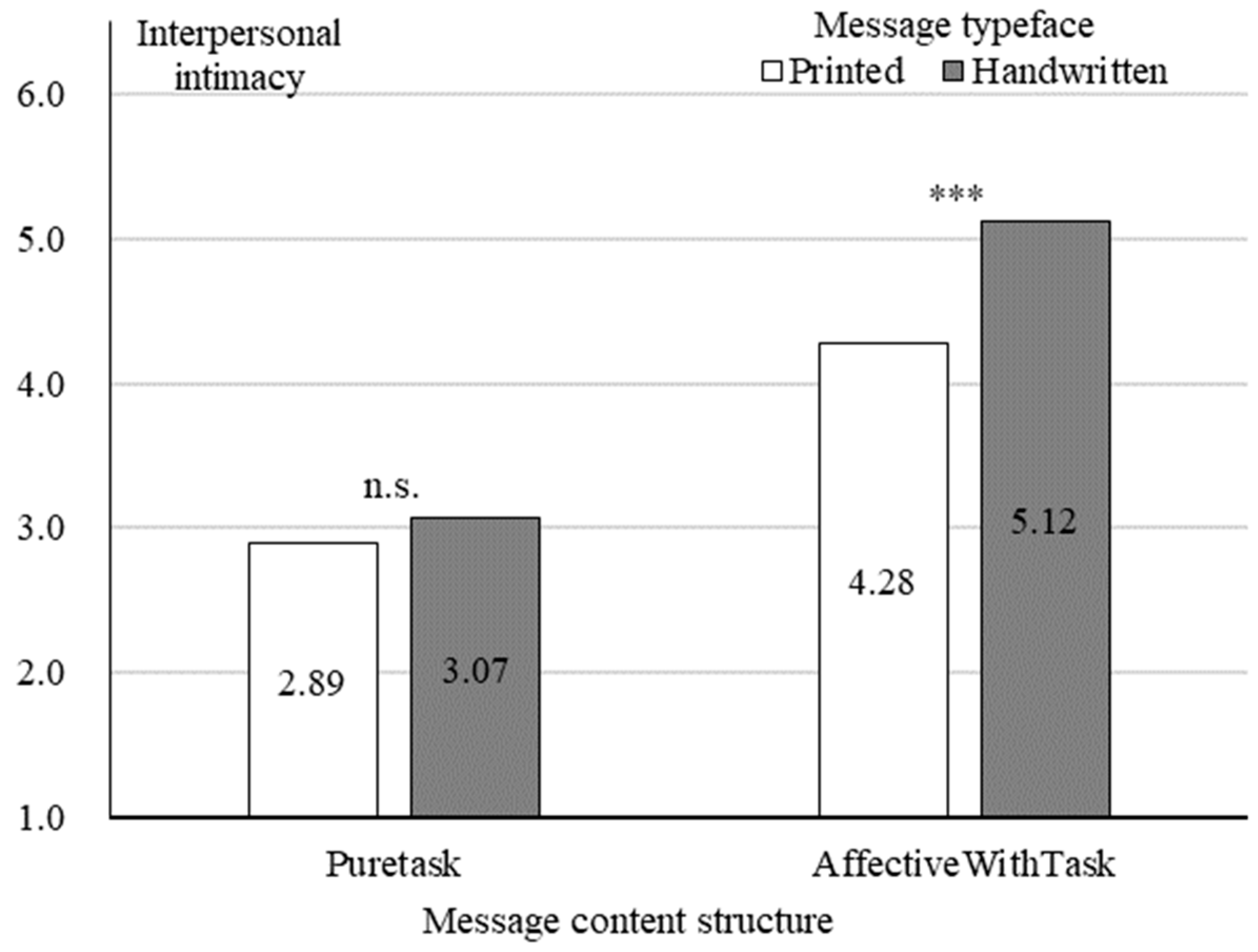

3.3. Study 2: The Mediating Role of Interpersonal Intimacy and the Moderating Role of Message Content Structure

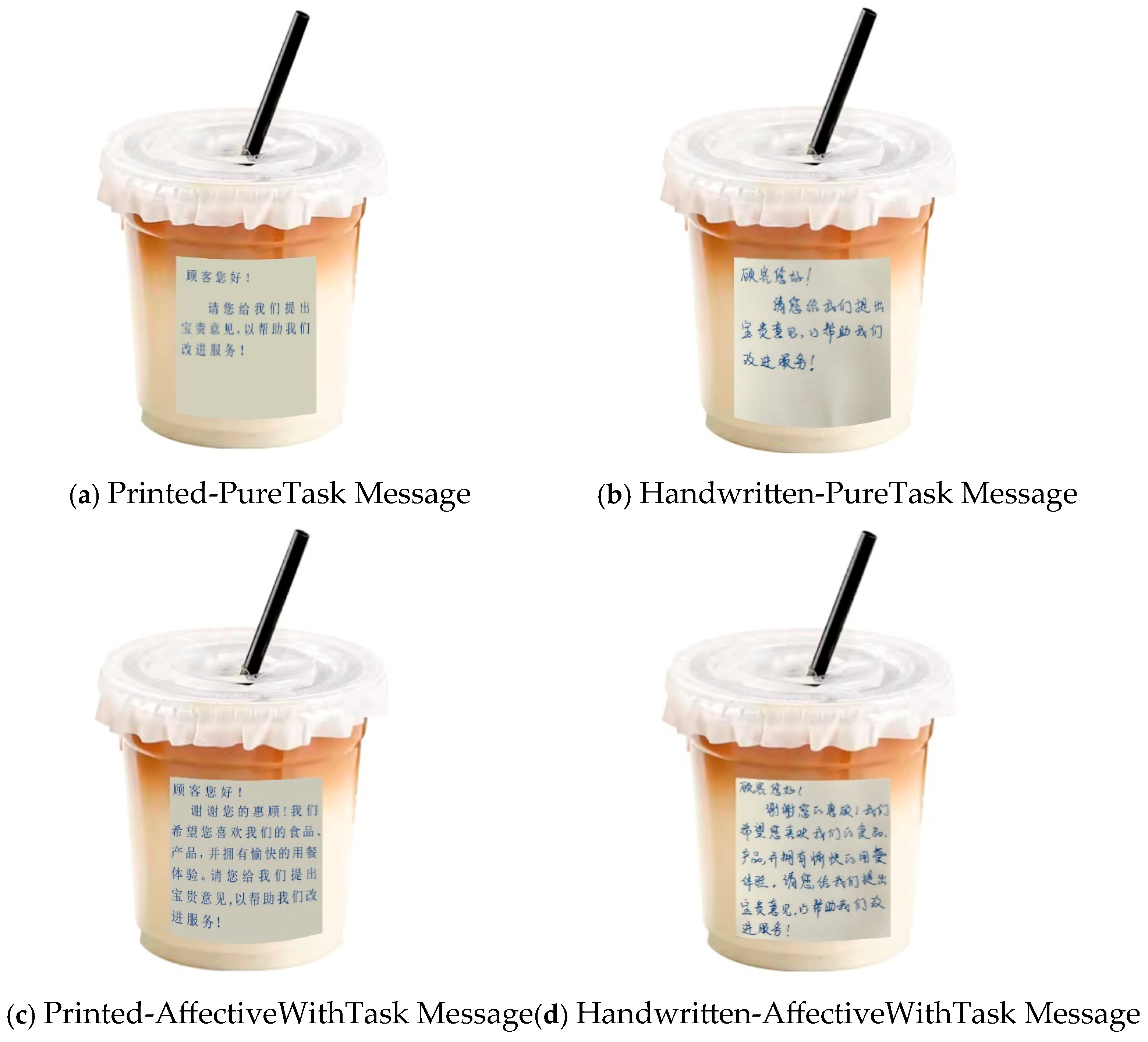

3.3.1. Study Design

3.3.2. Procedures

3.3.3. Results

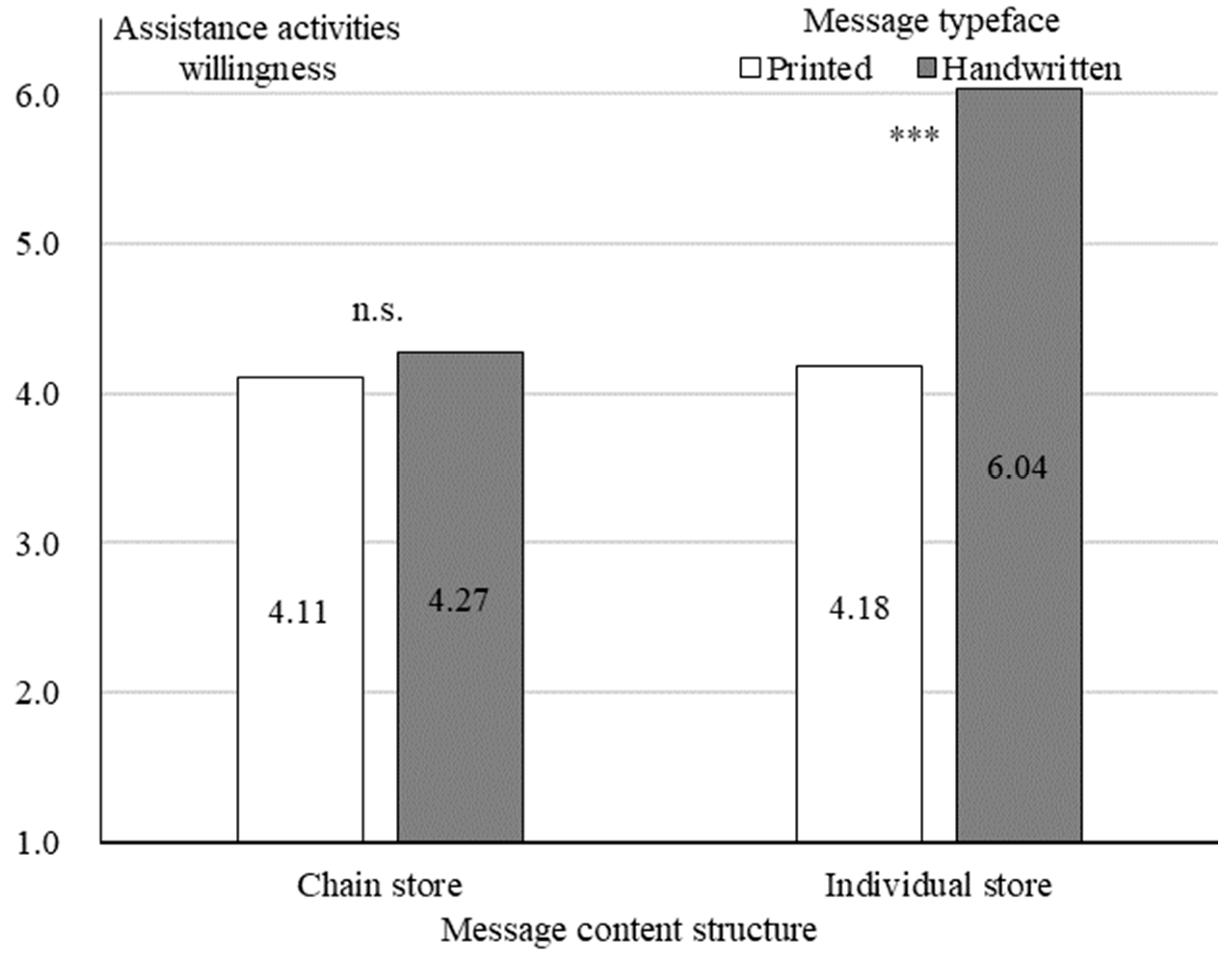

3.4. Study 3: The Moderating Role of Store Type

3.4.1. Study Design

3.4.2. Procedures

3.4.3. Results

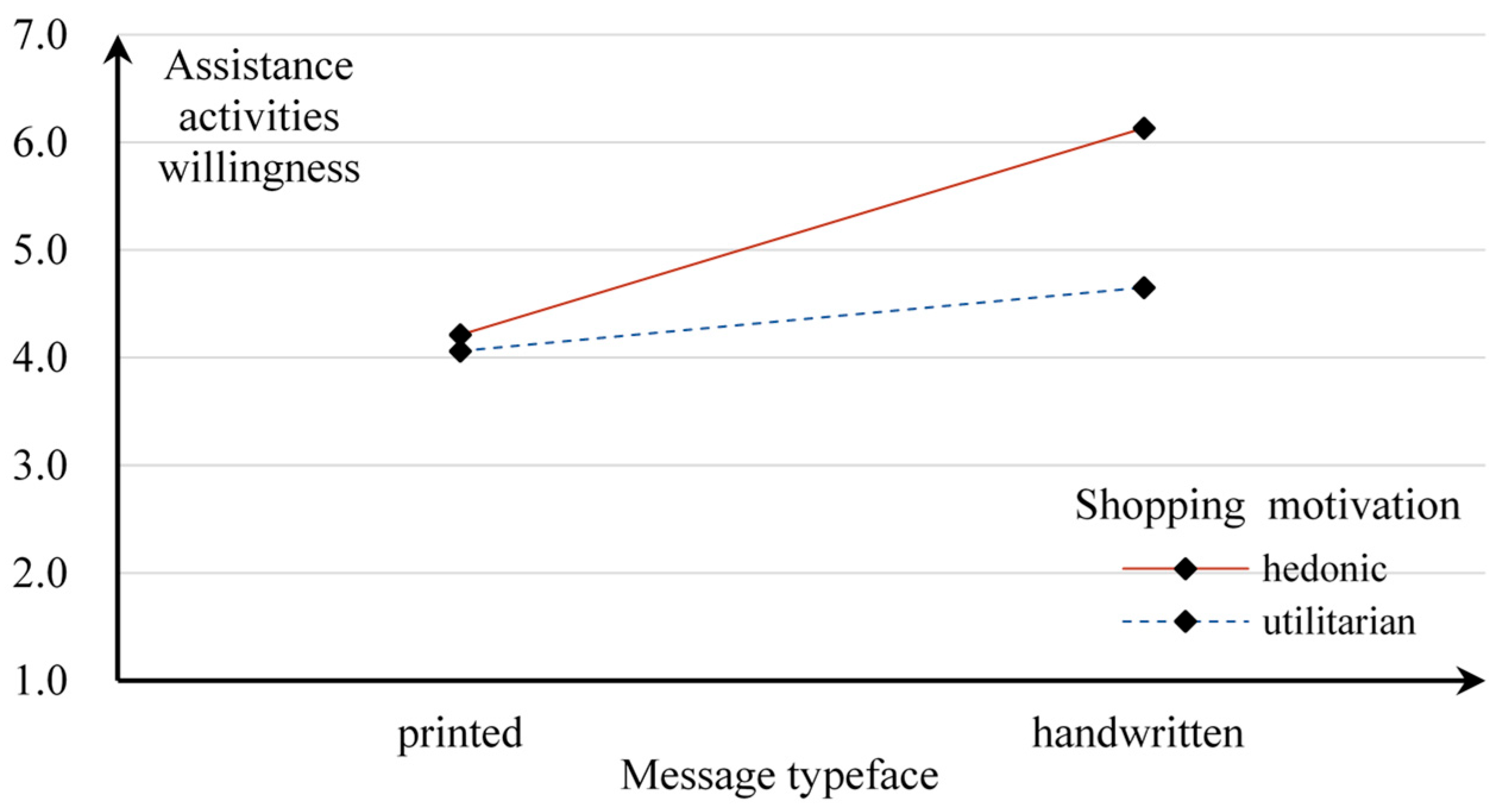

3.5. Study 4: The Moderating Role of Shopping Motivation

3.5.1. Study Design

3.5.2. Pretest

3.5.3. Procedures

3.5.4. Results

4. Conclusions

4.1. Theoretical Implications

4.2. Managerial Implications

4.3. Limitations and Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Offline Message from the Milk-Tea Merchants (Customer Reviews)

References

- Rivera, M. Online Delivery Provider (ODP) Services: Who Is Getting What from Food Deliveries? Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2019, 80, A1–A2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, J.; Choe, J.Y.J.; Kim, J.J. Exploring Perceived Risk in Building Successful Drone Food Delivery Services. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2020, 32, 1775–1794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ray, A.; Dhir, A.; Bala, P.K.; Kaur, P. Why Do People Use Food Delivery Apps (FDA)? A Uses and Gratification Theory Perspective. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2019, 51, 221–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Statista. eServices Report 2024—Online Food Delivery. 2024. Available online: https://www.statista.com/study/40457/food-delivery/ (accessed on 1 January 2024).

- Duan, W.; Gu, B.; Whinston, A.B. The Dynamics of Online Word-of-Mouth and Product Sales—An Empirical Investigation of the Movie Industry. J. Retail. 2008, 84, 233–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanford, S.; Kim, E.L. Risk versus Reward: When Will Travelers Go the Distance? J. Travel Res. 2019, 58, 745–759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, G.; Datta, B.; Basu, R. Effect of eWOM Valence on Online Retail Sales. Glob. Bus. Rev. 2017, 18, 198–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.X.; Yin, C.Y.; Li, M.R. The Power of Voice! The Impact of Robot Receptionists’ Voice Pitch and Communication Style on Customer Value Cocreation Intention. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2024, 122, 103819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linos, E.; Lasky-Fink, J.; Larkin, C.; Moore, L.; Kirkman, E. The Formality Effect. Nat. Hum. Behav. 2024, 8, 300–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.M.; Park, S. Does Language Shape the Mind? Linguistic Fluency and Perception of Service Quality. J. Serv. Mark. 2023, 37, 53–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, X.; Xia, L.; Du, J. Delivering Warmth by Hand: Customer Responses to Different Formats of Written Communication. J. Serv. Mark. 2018, 32, 223–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.Q.; Choi, S.; Mattila, A.S. Love Is in the Menu: Leveraging Healthy Restaurant Brands with Handwritten Typeface. J. Bus. Res. 2019, 98, 289–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shankar, A.; Jebarajakirthy, C.; Nayal, P.; Maseeh, H.I.; Kumar, A.; Sivapalan, A. Online Food Delivery: A Systematic Synthesis of Literature and a Framework Development. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2022, 104, 103240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- iiMedia Research. Survey Data on the Development Status and Consumer Behavior of China’s Online Food Delivery Platform Market; iiMedia: Guangzhou, China, 2025; Available online: https://data.iimedia.cn/data-classification/theme/13121676.html?acFrom=iminfo_103996&acPlatCode=imw (accessed on 21 February 2025).

- Zhao, Y.; Bacao, F. What Factors Determining Customer Continuingly Using Food Delivery Apps During 2019 Novel Coronavirus Pandemic Period? Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2020, 91, 102683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahn, J. Impact of Cognitive Aspects of Food Mobile Application on Customers’ Behaviour. Curr. Issues Tour. 2022, 25, 516–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Sun, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Lu, C. Research on Online Review Information Classification Based on Multimodal Deep Learning. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 3801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alalwan, A.A. Mobile Food Ordering Apps: An Empirical Study of the Factors Affecting Customer E-Satisfaction and Continued Intention to Reuse. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2020, 50, 28–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boldureanu, D.; Gutu, I.; Boldureanu, G. Understanding the Dynamics of e-WOM in Food Delivery Services: A SmartPLS Analysis of Consumer Acceptance. J. Theor. Appl. Electron. Commer. Res. 2025, 20, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roh, M.; Park, K. Adoption of O2O Food Delivery Services in South Korea: The Moderating Role of Moral Obligation in Meal Preparation. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2019, 47, 262–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verhoef, P.C.; Kannan, P.K.; Inman, J.J. From Multi-Channel Retailing to Omni-Channel Retailing: Introduction to the Special Issue on Multi-Channel Retailing. J. Retail. 2015, 91, 174–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapoor, A.; Vij, M. Technology at the Dinner Table: How Smartphones Influence Offline Dining Experiences. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2018, 43, 342–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, J.F.; Al-Khaled, A.A.S.; Martin, J.J. A Study on Consumer Attitude, Perceived Usefulness and Perceived Ease of Use to the Intention to Use Mobile Food Apps during COVID-19 Pandemic in Klang Valley, Malaysia. Int. J. Acad. Res. Bus. Soc. Sci. 2022, 12, 987–1000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, P.M.; Au, W.C.W.; Baum, T. Service Quality of Online Food Delivery Mobile Application: An Examination of the Spillover Effects of Mobile App Satisfaction. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2024, 36, 906–926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meena, P.; Kumar, G. Online Food Delivery Companies’ Performance and Consumers Expectations during COVID-19: An Investigation Using Machine Learning Approach. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2022, 68, 103052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senthil, M.; Gayathri, N.; Chandrasekar, K.S. Changing Paradigms of Indian Foodtech Landscape-Impact of Online Food Delivery Aggregators. Int. J. Food Syst. Dyn. 2020, 11, 139–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shorbaji, M.F.; Alalwan, A.A.; Algharabat, R. AI-Enabled Mobile Food-Ordering Apps and Customer Experience: A Systematic Review and Future Research Agenda. J. Theor. Appl. Electron. Commer. Res. 2025, 20, 156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pires, P.B.; Perestrelo, B.M.; Santos, J.D. Unpacking Customer Experience in Online Shopping: Effects on Satisfaction and Loyalty. J. Theor. Appl. Electron. Commer. Res. 2025, 20, 245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okumus, B.; Bilgihan, A. Proposing a Model to Test Smartphone Users’ Intention to Use Smart Applications in Ordering Food. J. Hosp. Tour. Technol. 2014, 5, 31–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, A.M.; Abbasi, A.Z.; Yan, X. Do Online Peer Reviews Stimulate Diners’ Continued Log-In Behavior: Investigating the Role of Emotions in the O2O Meal Delivery Apps Context. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2023, 72, 103234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schroll, R.; Schnurr, B.; Grewal, D. Humanizing Products with Handwritten Typefaces. J. Consum. Res. 2018, 45, 648–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Cui, X.; Zhao, Y. Handwritten Typeface Effect of Souvenirs: The Influence of Human Presence, Perceived Authenticity, Product Types, and Consumption Goals. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2024, 58, 345–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, J.; Li, X. AI Digital Human Responsiveness and Consumer Purchase Intention: The Mediating Role of Trust. J. Theor. Appl. Electron. Commer. Res. 2025, 20, 246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lăzăroiu, G.; Neguriţă, O.; Grecu, I.; Grecu, G.; Mitran, P.C. Consumers’ Decision-Making Process on Social Commerce Platforms: Online Trust, Perceived Risk, and Purchase Intentions. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xie, S.; Wei, H. Handwritten or Machine-Written? How Typeface Affects Consumer Forgiveness for Brand Failures. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2024, 81, 103938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Choi, J.; Kim, S.H. Do Handwritten Notes Benefit Online Retailers? A Field Experiment. J. Interact. Mark. 2022, 57, 651–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Izadi, A.; Patrick, V.M. The Power of the Pen: Handwritten Fonts Promote Haptic Engagement. Psychol. Mark. 2020, 37, 1082–1100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, H.; Liu, S.Q. “Donate to help combat COVID-19!” How typeface affects the effectiveness of CSR marketing? Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2020, 32, 3315–3333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aron, A.; Aron, E.N.; Tudor, M.; Nelson, G. Close Relationships as Including Other in the Self. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1991, 60, 241–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldstein, N.J.; Cialdini, R.B. The Spyglass Self: A Model of Vicarious Self-Perception. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2007, 92, 402–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubois, D.; Bonezzi, A.; De Angelis, M. Sharing with Friends versus Strangers: How Interpersonal Closeness Influences Word-of-Mouth Valence. J. Mark. Res. 2016, 53, 712–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batson, C.D.; Sager, K.; Garst, E.; Kang, M.; Rubchinsky, K.; Dawson, K. Is Empathy-Induced Helping Due to Self–Other Merging? J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1997, 73, 495–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, Y.; Gao, Y.; Mattila, A.S.; Wang, P. Optimizing Handwritten Font Style to Connect with Customers. Cornell Hosp. Q. 2023, 64, 381–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tok, D.; Huang, Y.H.; Yang, L. “Feel the Green”: How a Handwritten Typeface Affects Tourists’ Responses to Green Tourism Products and Services. Tour. Manag. 2024, 104, 104920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, X.; Huang, H.; Liu, S.Q.; Lu, Z. Signaling Authenticity of Ethnic Cuisines via Handwriting. Ann. Tour. Res. 2020, 85, 103054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Gao, M.; He, B.; Chen, C.H.; Hu, L. From Pen to Plate: How Handwritten Typeface and Narrative Perspective Shape Consumer Perceptions in Organic Food Consumption. Sustainability 2025, 17, 3961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F.; Ma, J. The Effectiveness of the Destination Logo: Congruity Effect Between Logo Typeface and Destination Stereotypes. Tour. Manag. 2023, 98, 104772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lo, L.Y.; Yeung, K.Y. An Effortful Apology: The Effect of Pen Pressure on Perceived Sincerity. Curr. Psychol. 2023, 42, 6395–6402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dillard, J.P.; Shen, L. On the Nature of Reactance and Its Role in Persuasive Health Communication. Commun. Monogr. 2005, 72, 144–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petty, R.E.; Cacioppo, J.T. Communication and Persuasion: Central and Peripheral Routes to Attitude Change; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Festinger, L. A Theory of Cognitive Dissonance; Row Peterson: Evanston, IL, USA, 1957. [Google Scholar]

- Yalcinkaya, B.; Just, D.R. Comparison of Customer Reviews for Local and Chain Restaurants: Multilevel Approach to Google Reviews Data. Cornell Hosp. Q. 2023, 64, 63–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srichookiat, S.; Jindabot, T. Small Family Grocers’ Inherent Advantages Over Chain Stores: A Review. Int. J. Retail Distrib. Manag. 2017, 45, 712–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodman, S.; Remaud, H. Store Choice: How Understanding Consumer Choice of ‘Where’ to Shop May Assist the Small Retailer. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2015, 23, 118–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldman, A.; Krider, R.; Ramaswami, S. The Persistent Competitive Advantage of Traditional Food Retailers in Asia: Wet Markets’ Continued Dominance in Hong Kong. J. Macromark. 1999, 19, 126–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klemz, B.R. Assessing Contact Personnel/Customer Interaction in a Small Town: Differences Between Large and Small Retail Districts. J. Serv. Mark. 1999, 13, 194–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heider, F. The Psychology of Interpersonal Relations; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 1958. [Google Scholar]

- Kotler, P.; Keller, K.L. Marketing Management, 14th ed.; Prentice Hall: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Garbarino, E.; Johnson, M.S. Effects of Consumer Goals on Attribute Weighting, Overall Satisfaction, and Product Usage. Psychol. Mark. 2001, 18, 929–949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huffman, C.; Houston, M.J. Goal-Oriented Experiences and the Development of Knowledge. J. Consum. Res. 1993, 20, 190–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ratneshwar, S.; Barsalou, L.W.; Pechmann, C.; Moore, M. Goal-Derived Categories: The Role of Personal and Situational Goals in Category Representations. J. Consum. Psychol. 2001, 10, 147–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babin, B.J.; Darden, W.R.; Griffin, M. Work and/or Fun: Measuring Hedonic and Utilitarian Shopping Value. J. Consum. Res. 1994, 20, 644–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adaval, R. Sometimes It Just Feels Right: The Differential Weighting of Affect-Consistent and Affect-Inconsistent Product Information. J. Consum. Res. 2001, 28, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacoby, L.L.; Dallas, M. On the Relationship Between Autobiographical Memory and Perceptual Learning. J. Exp. Psychol. Gen. 1981, 110, 306–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirschman, E.C.; Holbrook, M.B. Hedonic Consumption: Emerging Concepts, Methods and Propositions. J. Mark. 1982, 46, 92–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- iiMedia Research. China Online Food Delivery Platform Consumer Behavior Survey Data [Data Report]; iiMedia: Guangzhou, China, 2024; Available online: https://www.iimedia.cn/c1078/97809.html (accessed on 18 December 2024).

- Tolstedt, B.E.; Stokes, J.P. Relation of Verbal, Affective, and Physical Intimacy to Marital Satisfaction. J. Couns. Psychol. 1983, 30, 573–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, A.F. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach; The Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Kronrod, A.; Grinstein, A.; Wathieu, L. Go Green! Should Environmental Messages Be So Assertive? J. Mark. 2012, 76, 95–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, U.; Dhar, R. Price-Framing Effects on the Purchase of Hedonic and Utilitarian Bundles. J. Mark. Res. 2010, 47, 1090–1099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saad, A.T. Factors Affecting Online Food Delivery Service in Bangladesh: An Empirical Study. Br. Food J. 2021, 123, 535–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunden, N.; Morosan, C.; DeFranco, A. Are Online Food Delivery Systems Persuasive? The Impact of Pictures and Calorie Information on Consumer Behavior. J. Hosp. Tour. Insights 2021, 4, 457–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeo, V.C.S.; Goh, S.K.; Rezaei, S. Consumer Experiences, Attitude and Behavioral Intention Toward Online Food Delivery (OFD) Services. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2017, 35, 150–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chun, J.W.; Lee, M.J. Increasing Individuals’ Involvement and WOM Intention on Social Networking Sites: Content Matters! Comput. Hum. Behav. 2016, 60, 223–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, K.Y.; Yim, M.Y.C.; Kim, E.; Reeves, W. Exploring the Optimized Social Advertising Strategy That Can Generate Consumer Engagement with Green Messages on Social Media. J. Res. Interact. Mark. 2021, 15, 30–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Childers, T.L.; Jass, J. All Dressed Up with Something to Say: Effects of Typeface Semantic Associations on Brand Perceptions and Consumer Memory. J. Consum. Psychol. 2002, 12, 93–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cialdini, R.B.; Demaine, L.J.; Sagarin, B.J.; Barrett, D.W.; Rhoads, K.; Winter, P.L. Managing Social Norms for Persuasive Impact: Social Influence. Soc. Influ. 2006, 1, 3–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaibhav, A.; Sahu, R. Predicting Repeat Usage Intention Towards O2O Food Delivery: Extending UTAUT2 with User Gratifications and Bandwagoning. J. Foodserv. Bus. Res. 2021, 25, 434–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Effect Type | Effect | SE | t | Sig. | 95%CI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LLCI | ULCI | |||||

| Direct effect | 0.51 | 0.07 | 7.00 | 0.00 | 0.37 | 0.65 |

| Indirect effect (MT→IN→WEAA) | ||||||

| Puretask | 1.33 | 0.10 | 1.13 | 1.53 | ||

| AffectiveWithTask | 0.96 | 0.13 | 1.69 | 2.22 | ||

| Effect Type | Effect | SE | t | Sig. | 95%CI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LLCI | ULCI | |||||

| Direct effect | 0.297 | 0.082 | 3.607 | 0.000 | 0.134 | 0.459 |

| Indirect effect (MT→IN→EBI) | ||||||

| Individual | 0.725 | 0.176 | 0.377 | 1.065 | ||

| Chain | 0.590 | 0.135 | 0.321 | 0.854 | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Liu, Y.; Fu, X.; Lan, T. Handwritten Messages Boost Consumer Engagement in Food Delivery. J. Theor. Appl. Electron. Commer. Res. 2025, 20, 281. https://doi.org/10.3390/jtaer20040281

Liu Y, Fu X, Lan T. Handwritten Messages Boost Consumer Engagement in Food Delivery. Journal of Theoretical and Applied Electronic Commerce Research. 2025; 20(4):281. https://doi.org/10.3390/jtaer20040281

Chicago/Turabian StyleLiu, Yue, Xiaoxiao Fu, and Tian Lan. 2025. "Handwritten Messages Boost Consumer Engagement in Food Delivery" Journal of Theoretical and Applied Electronic Commerce Research 20, no. 4: 281. https://doi.org/10.3390/jtaer20040281

APA StyleLiu, Y., Fu, X., & Lan, T. (2025). Handwritten Messages Boost Consumer Engagement in Food Delivery. Journal of Theoretical and Applied Electronic Commerce Research, 20(4), 281. https://doi.org/10.3390/jtaer20040281