When Peers Drive Impulsive Buying: How Social Capital Reshapes Motivational Mechanisms in Chinese Social Commerce

Abstract

1. Introduction

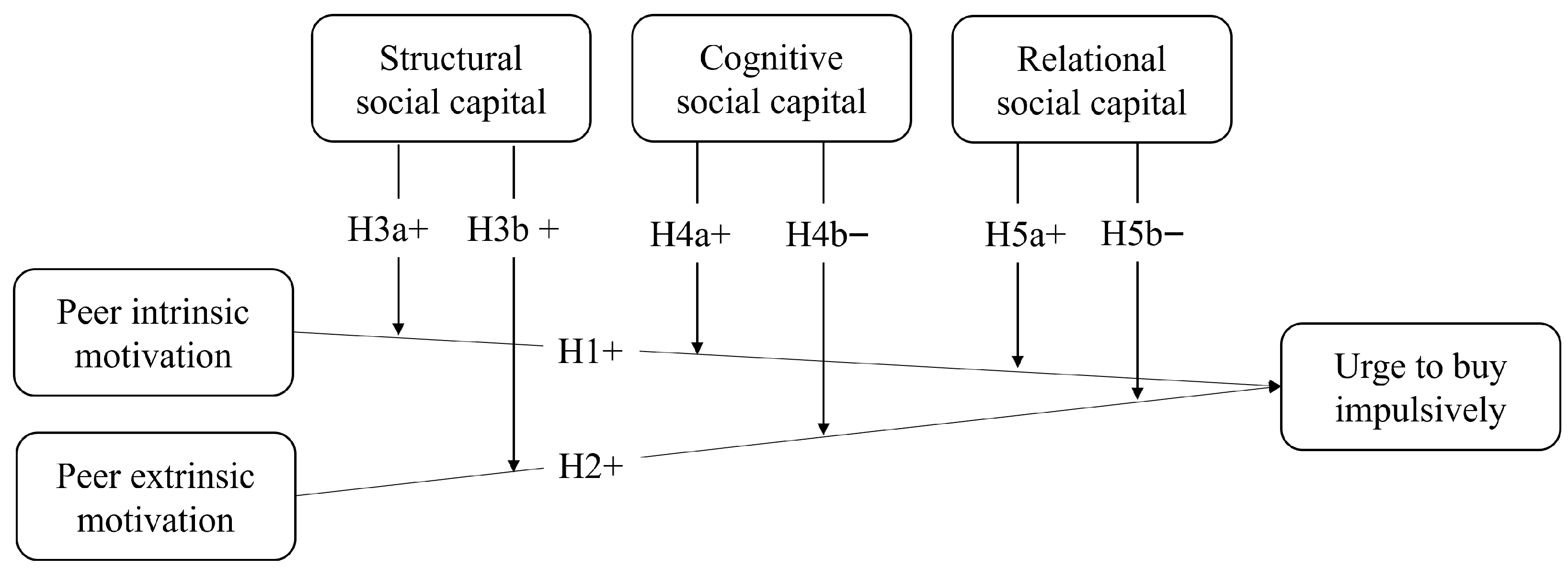

2. Related Work and Hypotheses

2.1. Impulsive Buying in Social Commerce

2.2. Influence of Peer Motivation

2.3. Influence of Social Capital

3. Method

3.1. Data Collection

3.2. Measures

3.3. Common Method Bias

4. Data Analysis and Results

4.1. Measurement Model

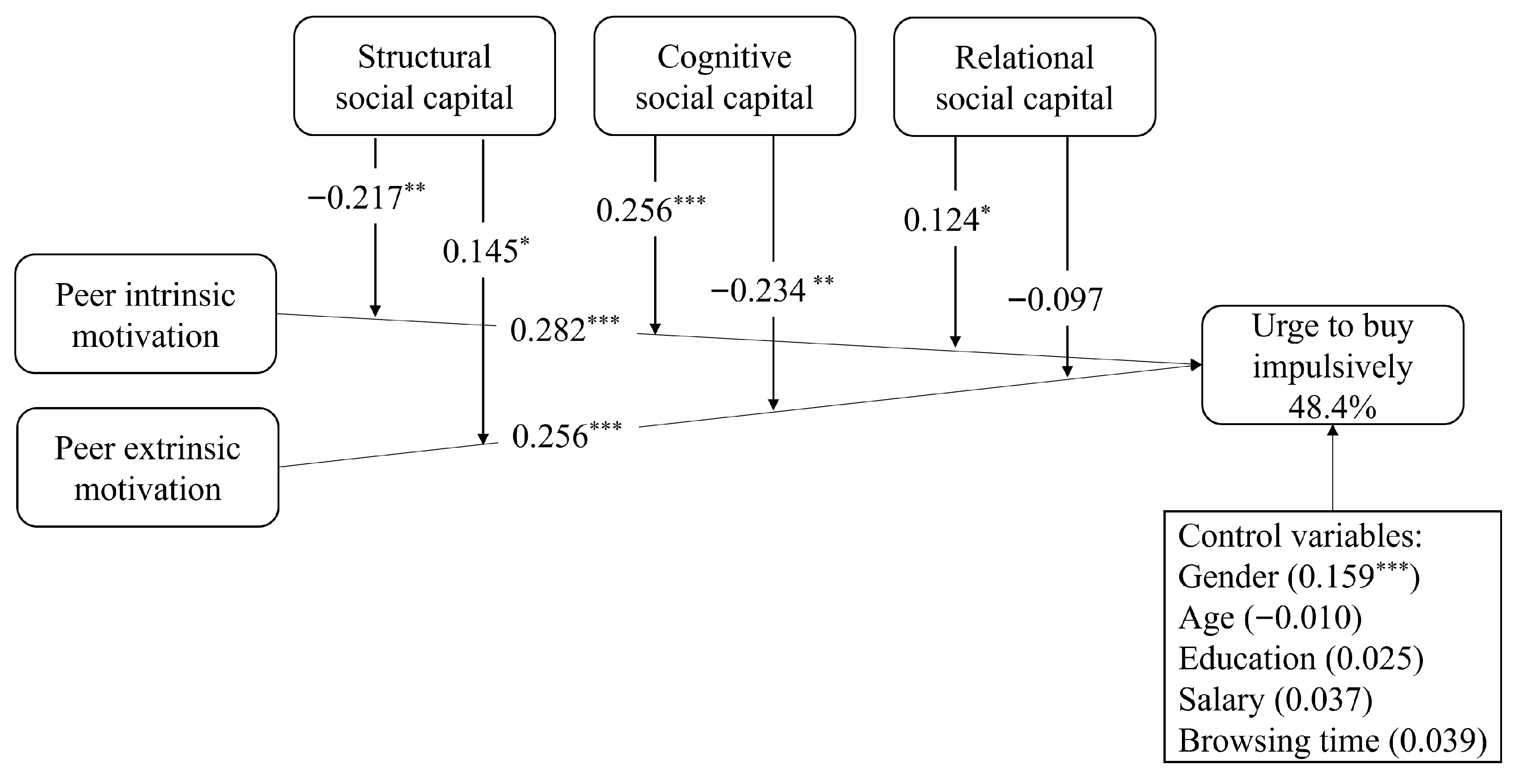

4.2. Structural Model

5. Discussion

5.1. Implications for Theory

5.2. Implications for Practice

5.3. Limtations and Future Research

Supplementary Materials

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Azad Moghddam, H.; Carlson, J.; Wyllie, J.; Mahmudur Rahman, S. Scroll, Stop, Shop: Decoding Impulsive Buying in Social Commerce. J. Bus. Res. 2024, 182, 114776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, X.; Yang, Y.; Wu, W. What Drives Social Shopping in Social Commerce Platform? The Effects of Affordance, Self-Congruity and Functional-Congruity. Inf. Technol. People, 2024; early access. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mousavi, S.; Roper, S. Enhancing Relationships Through Online Brand Communities: Comparing Posters and Lurkers. Int. J. Electron. Commer. 2023, 27, 66–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, Y.; Liu, L.; Lowry, P.B. How Do Consumers Make Behavioural Decisions on Social Commerce Platforms? The Interaction Effect between Behaviour Visibility and Social Needs. Inf. Syst. J. 2024, 34, 1703–1736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, J.S.-L.; Kwok, R.C.-W.; Fang, Y. The Effects of Peer Intrinsic and Extrinsic Motivation on MMOG Game-Based Collaborative Learning. Inf. Manag. 2012, 49, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, X. How Does Shopping with Others Influence Impulsive Purchasing? J. Consum. Psychol. 2005, 15, 288–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Q.; Pan, Z.; Lu, Y.; Wang, B. Heterophily or Homophily of Social Media Influencers: The Role of Dual Parasocial Relationships in Impulsive Buying. Int. J. Electron. Commer. 2023, 27, 558–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ou, C.X.; Pavlou, P.A.; Davison, R.M. Swift Guanxi in Online Marketplaces: The Role of Computer-Mediated Communication Technologies. MIS Q. 2014, 38, 209–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alghababsheh, M.; Gallear, D. Socially Sustainable Supply Chain Management and Suppliers’ Social Performance: The Role of Social Capital. J. Bus. Ethics 2021, 173, 855–875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiler, M.; Stolz, S.; Lanz, A.; Schlereth, C.; Hinz, O. Social Capital Accumulation through Social Media Networks: Evidence from a Randomized Field Experiment and Individual-Level Panel Data. MIS Q. 2022, 46, 771–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madrazo-Lemarroy, P.; Barajas-Portas, K.; Labastida Tovar, M.E. Analyzing Campaign’s Outcome in Reward-Based Crowdfunding: Social Capital as a Determinant Factor. Internet Res. 2019, 29, 1171–1189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Fang, Y.; Lim, K.H.; Straub, D. User Satisfaction with Information Technology Service Delivery: A Social Capital Perspective. Inf. Syst. Res. 2012, 23, 1195–1211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iyer, G.R.; Blut, M.; Xiao, S.H.; Grewal, D. Impulse Buying: A Meta-Analytic Review. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2020, 48, 384–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.; Gong, X.; Yan, R. Online Impulsive Buying in Social Commerce: A Mixed-Methods Research. Inf. Manag. 2024, 61, 103943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehrabian, A.; Russell, J.A. The Basic Emotional Impact of Environments. Percept. Mot. Ski. 1974, 38, 283–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chan, T.K.H.; Cheung, C.M.K.; Lee, Z.W.Y. The State of Online Impulse-Buying Research: A Literature Analysis. Inf. Manag. 2017, 54, 204–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vazquez, D.; Wu, X.; Nguyen, B.; Kent, A.; Gutierrez, A.; Chen, T. Investigating Narrative Involvement, Parasocial Interactions, and Impulse Buying Behaviours within a Second Screen Social Commerce Context. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2020, 53, 102135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, Z. How the Characteristics of Social Media Influencers and Live Content Influence Consumers’ Impulsive Buying in Live Streaming Commerce? The Role of Congruence and Attachment. J. Res. Interact. Mark. 2024, 18, 506–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.; Zhang, K.Z.K.; Zhao, S.J. A Dual Systems Model of Online Impulse Buying. Ind. Manag. Data Syst. 2020, 120, 845–861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morozova, N.; Vlaev, I. The Urge to Splurge: Differentiating Unplanned and Impulse Purchases. Int. J. Mark. Res. 2024, 66, 519–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Lu, Y.; Wang, B.; Pan, Z. How Do Product Recommendations Affect Impulse Buying? An Empirical Study on WeChat Social Commerce. Inf. Manag. 2019, 56, 236–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Setyani, V.; Zhu, Y.-Q.; Hidayanto, A.N.; Sandhyaduhita, P.I.; Hsiao, B. Exploring the Psychological Mechanisms from Personalized Advertisements to Urge to Buy Impulsively on Social Media. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2019, 48, 96–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zafar, A.U.; Qiu, J.; Li, Y.; Wang, J.; Shahzad, M. The Impact of Social Media Celebrities’ Posts and Contextual Interactions on Impulse Buying in Social Commerce. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2021, 115, 106178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, L.-T. Flow and Social Capital Theory in Online Impulse Buying. J. Bus. Res. 2016, 69, 2277–2283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, I.-L.; Chiu, M.-L.; Chen, K.-W. Defining the Determinants of Online Impulse Buying through a Shopping Process of Integrating Perceived Risk, Expectation-Confirmation Model, and Flow Theory Issues. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2020, 52, 102099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zafar, A.U.; Shahzad, M.; Ashfaq, M.; Shahzad, K. Forecasting Impulsive Consumers Driven by Macro-Influencers Posts: Intervention of Followers’ Flow State and Perceived Informativeness. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2023, 190, 122408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Li, Y.-Q.; Ruan, W.-Q.; Zhang, S.-N. Owned Media or Earned Media? The Influence of Social Media Types on Impulse Buying Intention in Internet Celebrity Restaurants. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2023, 111, 103487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, W.; Yang, Q.; Gong, X. Impulsive Social Shopping in Social Commerce Platforms: The Role of Perceived Proximity. Inf. Syst. Front. 2023, 26, 1527–1541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Kang, K.; Zhao, A.; Feng, Y. The Impact of Social Presence and Facilitation Factors on Online Consumers’ Impulse Buying in Live Shopping–Celebrity Endorsement as a Moderating Factor. Inf. Technol. People 2023, 36, 2611–2631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anoop, T.S.; Rahman, Z. Online Impulse Buying: A Systematic Review of 25 Years of Research Using Meta Regression. J. Consum. Behav. 2025, 24, 363–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, X.; Zhang, H.; Sun, J.; Xiang, L.; Wei, J. Impulsive Purchase Behavior in Social Commerce The Role of Social Influence. In Proceedings of the Pacific Asia Conference on Information Systems, Chiayi, Taiwan, 27 July 2016; p. 18. [Google Scholar]

- Deci, E.L.; Ryan, R.M.; Gagné, M.; Leone, D.R.; Usunov, J.; Kornazheva, B.P. Need Satisfaction, Motivation, and Well-Being in the Work Organizations of a Former Eastern Bloc Country: A Cross-Cultural Study of Self-Determination. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 2001, 27, 930–942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkatesh, V. Determinants of Perceived Ease of Use: Integrating Control, Intrinsic Motivation, and Emotion into the Technology Acceptance Model. Inf. Syst. Res. 2000, 11, 342–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vallerand, R.J. Toward A Hierarchical Model of Intrinsic and Extrinsic Motivation. Adv. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 1997, 29, 271–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fruchter, G.E.; Prasad, A. Too Popular, Too Fast: Optimal Advertising and Entry Timing in Markets with Peer Influence. Manag. Sci. 2022, 68, 4725–4741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pyo, T.-H.; Lee, J.Y.; Park, H.M. The Effects of Consumer Preference and Peer Influence on Trial of an Experience Good. J. Mark. Res. 2022, 59, 1161–1178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langer, N.; Jain, T. Peer Influence and IT Career Choice. Inf. Syst. Res. 2024, 35, 642–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Han, X.; Moon, H. Host-Guest Interactions in Peer-to-Peer Accommodation: Scale Development and Its Influence on Guests’ Value Co-Creation Behaviors. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2023, 110, 103447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belo, R.; Ferreira, P. Free-Riding in Products with Positive Network Externalities: Empirical Evidence from a Large Mobile Network. MIS Q. 2022, 46, 401–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klapper, H.; Reitzig, M. On the Effects of Authority on Peer Motivation: Learning from Wikipedia. Strateg. Manag. J. 2018, 39, 2178–2203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parboteeah, D.V.; Valacich, J.S.; Wells, J.D. The Influence of Website Characteristics on a Consumer’s Urge to Buy Impulsively. Inf. Syst. Res. 2009, 20, 60–78. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, M.T.; Theokary, C. The Superstar Social Media Influencer: Exploiting Linguistic Style and Emotional Contagion over Content? J. Bus. Res. 2021, 132, 860–871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasford, J.; Hardesty, D.M.; Kidwell, B. More than a Feeling: Emotional Contagion Effects in Persuasive Communication. J. Mark. Res. 2015, 52, 836–847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Good, V.; Hughes, D.E.; Kirca, A.H.; McGrath, S. A Self-Determination Theory-Based Meta-Analysis on the Differential Effects of Intrinsic and Extrinsic Motivation on Salesperson Performance. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2022, 50, 586–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, T.; Barbeitos, I.; Calado, A. The Role of Intrinsic and Extrinsic Motivations in Sharing Economy Post-Adoption. Inf. Technol. People 2021, 35, 165–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Z.; Hui, K.-L.; Xu, H. When Discounts Hurt Sales: The Case of Daily-Deal Markets. Inf. Syst. Res. 2018, 29, 567–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lo, P.-S.; Dwivedi, Y.K.; Wei-Han Tan, G.; Ooi, K.-B.; Cheng-Xi Aw, E.; Metri, B. Why Do Consumers Buy Impulsively during Live Streaming? A Deep Learning-Based Dual-Stage SEM-ANN Analysis. J. Bus. Res. 2022, 147, 325–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, P.; He, J.; Li, A. Upward Social Comparison on Social Network Sites and Impulse Buying: A Moderated Mediation Model of Negative Affect and Rumination. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2019, 96, 133–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caya, O.; Mosconi, E. Citizen Behaviors, Enterprise Social Media and Firm Performance. Inf. Technol. People 2022, 36, 1298–1325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nahapiet, J.; Ghoshal, S. Social Capital, Intellectual Capital, and the Organizational Advantage. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1998, 23, 242–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, K.H.; Shim, D.C.; Park, H.H. Revisiting Theory of Social Capital: Can the Internet Make a Difference? Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2024, 202, 123282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiu, C.-M.; Hsu, M.-H.; Wang, E.T.G. Understanding Knowledge Sharing in Virtual Communities: An Integration of Social Capital and Social Cognitive Theories. Decis. Support Syst. 2006, 42, 1872–1888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, H.H.; Chuang, S.-S. Social Capital and Individual Motivations on Knowledge Sharing: Participant Involvement as a Moderator. Inf. Manag. 2011, 48, 9–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Gupta, S.; Sun, W.; Zou, Y. How Social-Media-Enabled Co-Creation between Customers and the Firm Drives Business Value? The Perspective of Organizational Learning and Social Capital. Inf. Manag. 2020, 57, 103200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, Y.; Sun, L. Entrepreneurs’ Social Capital and Venture Capital Financing. J. Bus. Res. 2021, 136, 499–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coleman, J.S. Social Capital in the Creation of Human Capital. Am. J. Sociol. 1988, 94, 95–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Q.; Chen, X.; Ou, C.X.; Davison, R.M.; Hua, Z. Understanding Buyers’ Loyalty to a C2C Platform: The Roles of Social Capital, Satisfaction and Perceived Effectiveness of E-commerce Institutional Mechanisms. Inf. Syst. J. 2017, 27, 91–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horng, S.-M.; Wu, C.-L. How Behaviors on Social Network Sites and Online Social Capital Influence Social Commerce Intentions. Inf. Manag. 2020, 57, 103176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M. Understanding How Customer Social Capital Accumulation in Brand Communities: A Gamification Affordance Perspective. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2024, 78, 103761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wyer, R.S. Language and Advertising Effectiveness: Mediating Influences of Comprehension and Cognitive Elaboration. Psychol. Mark. 2002, 19, 693–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Patrick, V.M. Mickey D’s Has More Street Cred Than McDonald’s: Consumer Brand Nickname Use Signals Information Authenticity. J. Mark. 2021, 85, 58–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Q.; Mu, Y.; Guo, X.; Jiang, W.; Chen, G. Dynamic Bayesian Network–Based Product Recommendation Considering Consumers’ Multistage Shopping Journeys: A Marketing Funnel Perspective. Inf. Syst. Res. 2023, 35, 1382–1402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, Z.; Pan, Z. Building Guanxi Network in the Mobile Social Platform: A Social Capital Perspective. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2019, 44, 109–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zollo, L. The Consumers’ Emotional Dog Learns to Persuade Its Rational Tail: Toward a Social Intuitionist Framework of Ethical Consumption. J. Bus. Ethics 2021, 168, 295–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Huang, Q.; Davison, R.M. Economic and Social Satisfaction of Buyers on Consumer-to-Consumer Platforms: The Role of Relational Capital. Int. J. Electron. Commer. 2017, 21, 219–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.-W.; Gao, G.; Agarwal, R. Reciprocity or Self-Interest? Leveraging Digital Social Connections for Healthy Behavior. MIS Q. 2022, 46, 261–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wasko, M.M.; Faraj, S. Why Should I Share? Examining Social Capital and Knowledge Contribution in Electronic Networks of Practice. MIS Q. 2005, 29, 35–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, X.; Chen, X.; Davison, R.M. Social Support, Source Credibility, Social Influence, and Impulsive Purchase Behavior in Social Commerce. Int. J. Electron. Commer. 2019, 23, 297–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Liu, Z.; Wei, S.; Liu, Y. Understanding the Role of Affordances in Promoting Social Commerce Engagement. Int. J. Electron. Commer. 2021, 25, 287–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verhagen, T.; van Dolen, W. The Influence of Online Store Beliefs on Consumer Online Impulse Buying: A Model and Empirical Application. Inf. Manag. 2011, 48, 320–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Lee, J.-Y.; Podsakoff, N.P. Common Method Biases in Behavioral Research A Critical Review of the Literature and Recommended Remedies. J. Appl. Psychol. 2003, 88, 879–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, H.; Saraf, N.; Hu, Q.; Xue, Y. Assimilation of Enterprise Systems: The Effect of Institutional Pressures and the Mediating Role of Top Management. MIS Q. 2007, 31, 59–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chin, W.W. Commentary: Issues and Opinion on Structural Equation Modeling. MIS Q. 1998, 22, vii–xvi. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.F.; Anderson, R.E.; Tatham, R.L.; Black, W.C. Multivariate Data Analysis; Prentice Hall: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating Structural Equation Models with Unobservable Variables and Measurement Error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar]

- Liébana-Cabanillas, F.; Molinillo, S.; Ruiz-Montañez, M. To Use or Not to Use, That Is the Question: Analysis of the Determining Factors for Using NFC Mobile Payment Systems in Public Transportation. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2019, 139, 266–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henseler, J.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. A New Criterion for Assessing Discriminant Validity in Variance-Based Structural Equation Modeling. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2015, 43, 115–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, L.; Bentler, P.M. Cutoff Criteria for Fit Indexes in Covariance Structure Analysis: Conventional Criteria versus New Alternatives. Struct. Equ. Model. A Multidiscip. J. 1999, 6, 1–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J.; Cohen, P.; West, S.G.; Aiken, L.S. Applied Multiple Regression/Correlation Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates: London, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Chan, C.K.; Fang, Y.; Li, H. Relative Advantage of Interactive Electronic Banking Adoption by Premium Customers: The Moderating Role of Social Capital. Internet Res. 2019, 30, 357–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Chen, R.P.; Zhang, K. Anthropomorphized Helpers Undermine Autonomy and Enjoyment in Computer Games. J. Consum. Res. 2016, 43, 282–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.V.; Su, B.; Widjaja, A.E. Facebook C2C Social Commerce: A Study of Online Impulse Buying. Decis. Support Syst. 2016, 83, 57–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X. Understanding Consumers’ Purchase Intentions in Social Commerce through Social Capital: Evidence from SEM and fsQCA. J. Theor. Appl. Electron. Commer. Res. 2021, 16, 1557–1570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, W.; Ghoshal, S. Social Capital and Value Creation: The Role of Intrafirm Networks. Acad. Manag. J. 1998, 41, 464–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.-C.; Chiang, M.-J. Social Interaction and Continuance Intention in Online Auctions: A Social Capital Perspective. Decis. Support Syst. 2009, 47, 466–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, Y.-H.; Joe, S.-W.; Lin, C.-P.; Wang, R.-T.; Chang, Y.-H. Modeling the Relationship between IT-Mediated Social Capital and Social Support: Key Mediating Mechanisms of Sense of Group. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2012, 79, 1592–1604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Ye, F.; Sheu, C. Social Capital, Information Sharing and Performance: Evidence from China. Int. J. Oper. Prod. Manag. 2014, 34, 1440–1462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Pan, Y.; Guo, B. The Influence of Personality Traits and Social Networks on the Self-Disclosure Behavior of Social Network Site Users. Internet Res. 2016, 26, 566–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigo-Alarcón, J.; García-Villaverde, P.M.; Ruiz-Ortega, M.J.; Parra-Requena, G. From Social Capital to Entrepreneurial Orientation: The Mediating Role of Dynamic Capabilities. Eur. Manag. J. 2018, 36, 195–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Attributes | Category | Frequency | Percentage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 78 | 23.1% |

| Female | 259 | 76.9% | |

| Age | 20 or below | 139 | 41.2% |

| 21–30 | 172 | 51.0% | |

| 31–40 | 10 | 3.0% | |

| 41 or above | 16 | 4.8% | |

| Education | Below college | 72 | 21.4% |

| Bachelor degree | 238 | 70.6% | |

| Master’s degree or above | 27 | 8.0% | |

| Income (Monthly) | 5000 or below | 239 | 70.9% |

| 5001–8000 | 76 | 22.6% | |

| 8000–10,000 | 16 | 4.7% | |

| 10,001 or above | 6 | 1.8% | |

| Time spent on browsing social media per day (H) | >0 and ≤1 | 117 | 34.7% |

| >1 and ≤2 | 117 | 34.7% | |

| >2 and ≤3 | 42 | 12.5% | |

| >3 (h) | 61 | 18.1% |

| Construct | Item | Factor Loading | Cronbah’s α | Composite Reliability | AVE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Structural social capital (Social interaction ties)—SIT | SIT1 | 0.858 | 0.87 | 0.91 | 0.72 |

| SIT2 | 0.894 | ||||

| SIT3 | 0.869 | ||||

| SIT4 | 0.765 | ||||

| Cognitive social capital (Shared language)—SLA | SLA1 | 0.791 | 0.78 | 0.87 | 0.70 |

| SLA2 | 0.866 | ||||

| SLA3 | 0.846 | ||||

| Relational social capital (Reciprocity)—REC | REC1 | 0.940 | 0.87 | 0.94 | 0.88 |

| REC2 | 0.938 | ||||

| Peer intrinsic motivation—PIM | PIM1 | 0.865 | 0.91 | 0.94 | 0.78 |

| PIM2 | 0.888 | ||||

| PIM3 | 0.910 | ||||

| PIM4 | 0.879 | ||||

| Peer extrinsic motivation—PEM | PEM1 | 0.754 | 0.80 | 0.88 | 0.71 |

| PEM3 | 0.858 | ||||

| PEM4 | 0.872 | ||||

| Urge to buy impulsively—UBI | UBI1 | 0.847 | 0.85 | 0.90 | 0.70 |

| UBI2 | 0.808 | ||||

| UBI3 | 0.841 | ||||

| UBI4 | 0.839 |

| Construct | SIT | SLA | REC | PIM | PEM | UBI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SIT | 0.848 | |||||

| SLA | 0.505 | 0.835 | ||||

| REC | 0.401 | 0.165 | 0.939 | |||

| PIM | 0.395 | 0.449 | 0.409 | 0.886 | ||

| PEM | 0.316 | 0.304 | 0.279 | 0.515 | 0.791 | |

| UBI | 0.434 | 0.379 | 0.283 | 0.537 | 0.497 | 0.834 |

| Construct | SIT | SLA | REC | PIM | PEM | UBI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SIT | ||||||

| SLA | 0.605 | |||||

| REC | 0.458 | 0.201 | ||||

| PIM | 0.446 | 0.532 | 0.462 | |||

| PEM | 0.393 | 0.395 | 0.353 | 0.613 | ||

| UBI | 0.500 | 0.461 | 0.326 | 0.603 | 0.578 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Xu, H. When Peers Drive Impulsive Buying: How Social Capital Reshapes Motivational Mechanisms in Chinese Social Commerce. J. Theor. Appl. Electron. Commer. Res. 2025, 20, 252. https://doi.org/10.3390/jtaer20030252

Xu H. When Peers Drive Impulsive Buying: How Social Capital Reshapes Motivational Mechanisms in Chinese Social Commerce. Journal of Theoretical and Applied Electronic Commerce Research. 2025; 20(3):252. https://doi.org/10.3390/jtaer20030252

Chicago/Turabian StyleXu, Haiqin. 2025. "When Peers Drive Impulsive Buying: How Social Capital Reshapes Motivational Mechanisms in Chinese Social Commerce" Journal of Theoretical and Applied Electronic Commerce Research 20, no. 3: 252. https://doi.org/10.3390/jtaer20030252

APA StyleXu, H. (2025). When Peers Drive Impulsive Buying: How Social Capital Reshapes Motivational Mechanisms in Chinese Social Commerce. Journal of Theoretical and Applied Electronic Commerce Research, 20(3), 252. https://doi.org/10.3390/jtaer20030252