Abstract

The rapid rise of live streaming e-commerce has transformed retail dynamics; however, the allocation of after-sales service costs between live streaming salespeople and manufacturers remains a critical, unresolved issue, exacerbated by fairness concerns among stakeholders. Utilizing a Stackelberg game model where manufacturers act as leaders and live streaming salespeople as followers, this study examines the impact of cost allocation on profit distribution and supply chain efficiency. The framework incorporates a coefficient for fairness concerns and an after-sales effort to develop nine decision-making scenarios. Analysis demonstrates that perceptions of fairness significantly reshape cost-sharing strategies: when manufacturers assume after-sales responsibilities, their scale effects reduce marginal costs, maximizing overall supply chain profit. Conversely, when a live streaming salesperson bears costs, excessive focus on fairness reduces total supply chain efficiency, even if short-term profits are gained through premium pricing. These results validate that the Stackelberg game model combined with fairness concerns and after-sales efforts balances efficiency–profit dual objectives, providing a sustainable governance framework for live streaming e-commerce ecosystems.

1. Introduction

According to a report on the development of live streaming e-commerce in China (China International E-commerce Center, 2024 [1]), the industry has expanded rapidly in recent years. The market size grew from RMB 1.2 trillion in 2020 to approximately RMB 2 trillion in 2021 and further reached about RMB 3.5 trillion in 2022. In 2023, it surged to RMB 4.9 trillion, marking a robust 35.2% year-on-year growth. Although the growth has slowed considerably compared to initial rapid-growth phases, with transaction volume even contracting by around 5% year-on-year in the first half of 2023, the overall market continues to expand.

Simultaneously, the number of live streaming salespeople has surged, surpassing the one million active practitioner mark in 2021, a substantial portion being small-to-medium-sized streamers. However, these streamers often face unfair profit distribution issues, typically receiving only 10% to 15% of sales profits. Nearly 50% of small and medium-sized live streaming salespeople report dissatisfaction with profit-sharing arrangements. Some have experienced sales declines and income reductions of over 20%, leading to reduce after-sales efforts and even considerations of exiting the industry.

To address the current issue of small and medium-sized live streaming salespeople being inclined to exit the industry or reduce their after-sales service efforts, it is imperative to focus on economic fairness within the live streaming sales sector. As the industry continues to thrive, live streaming salespeople significantly contribute to the profits of platforms and brands through their after-sales service efforts. However, the phenomenon of unfair profit distribution or wealth concentration may prevent some participants from receiving their due rewards. Such inequities could lead to measures being taken by those affected, potentially giving rise to social issues. For instance, when consumers purchase certain small electronic products, if problems occur within the warranty period, they usually turn to retailers for warranty services. The manufacturer does not undertake after-sales services. When consumers purchase large home appliances or products from well-known brands, they typically receive services directly from the brand’s official after-sales outlets or authorized repair centers, eliminating the need to contact retailers. This incident reveals the potential dominant role of manufacturers in profit distribution, shifting the risk onto the live streaming salesperson, who finds themselves in a relatively passive position within the partnership. If the distribution of profits among supply chain members is unfair or the rewards for after-sales service efforts are inadequate, it will lead to a decline in product quality and service levels. This, in turn, affects consumer rights and shopping experiences, prompting consumers to pay more attention to the protection of their own rights. Protecting consumer rights is essential not only for safeguarding consumer interests but also for ensuring the healthy development of the industry. Furthermore, unfair profit distribution can exacerbate social wealth disparities, impacting social stability and harmony.

Secondly, we must also consider the issue of labor value in live streaming commerce. Live streaming salespeople need to engage in live planning before the broadcast, manage fan relationships to enhance loyalty, actively engage with the audience and create a lively atmosphere during the broadcast, and set up promotional activities to attract viewers. For merchants, live streaming commerce can stimulate impulsive consumption by leveraging live streaming salespeople’s emotions, while for consumers, purchasing in the livestream can avoid awkwardness faced by socially anxious individuals in offline shopping. As a popular industry, live streaming has a large number of participants and varying levels of personnel quality. After-sales service covers a wide range, including repair and maintenance, return and exchange services, technical support, consultation, customer training, feedback and improvement, etc. The broad scope of after-sales service has made it a challenge in the live streaming e-commerce supply chain, and many consumers are facing difficulties in after-sales service. If live streaming salesperson can improve the quality of their after-sales service, it will greatly increase the sales volume of their live broadcasts. Improving the quality of after-sales service can not only effectively improve customer satisfaction and promote repeated consumption but also improve brand reputation and form free advertising. High-quality after-sales service can also improve the sales price of products to a certain extent so that businesses can obtain more profits and industry participants can contribute to product sales through their labor and efforts, but whether the profits they receive are commensurate with their labor value and contributions is worth pondering. Additionally, as an emerging industry, live streaming commerce is still in its infancy in terms of regulation and oversight, leading to significant uncertainties and disputes regarding profit distribution and rewards for after-sales service efforts. The lack of norms and regulations can lead to issues such as unfair competition and transactions within the industry, negatively impacting the overall market order and industry development. Therefore, it is essential for the state to establish robust industry norms and regulatory mechanisms. This paper will explore strategies for profit distribution in live streaming sales, with a focus on issues of fairness and whether rewards match labor value, addressing social concerns. This paper will attempt to propose solutions for supply chain optimization and coordination to promote healthy industry development, enhancing fairness and transparency in profit distribution, and creating a better shopping and working environment for consumers and participants. Additionally, this paper hopes to draw more attention and contemplation to the issues facing society today, driving progress and improvement in relevant policies and norms.

This paper constructs a Stackelberg game model to explore the interaction between after-sales service commitment, equity concerns, and supply chain profits. Therefore, three main research questions are proposed.

- (1)

- The optimal allocation of after-sales cost in the supply chain of live streaming e-commerce.

By constructing game theory models (such as an L model, S model, etc.), this paper discusses different scenarios in which the manufacturer or live streaming salesperson bears the after-sale cost. It is found that when the manufacturer undertakes the after-sales cost, its mature after-sales system and scale effect can reduce marginal cost and improve the overall profit of the supply chain. When live streaming salespeople bear after-sales costs, they need to cover the potential costs through a higher premium, which may lead to overpricing and weaken profits. The purpose of the study is to determine which cost-sharing model can achieve the best balance between economic efficiency and after-sales service quality.

- (2)

- Fairness concerns the impact on profit distribution strategies.

In this paper, the equity concern coefficient is introduced to analyze how the psychological perception of equity of profit distribution affects the decision-making of live streaming salespeople or manufacturers. For example, when a live streaming salesperson perceives an unfair distribution, retaliatory measures may be taken, such as reducing after-sales service efforts, leading to supply chain conflicts. The research shows that manufacturers, as game leaders, need to consider fair mechanisms in pricing and profit distribution in order to alleviate the dissatisfaction of live streaming salespeople and maintain long-term cooperation. The study reveals the dynamic effects of equity concerns on wholesale prices, retail prices, and profits of each party.

- (3)

- The role of after-sales service efforts in the coordination of sales performance and supply chain.

This paper quantifies the influence of live streaming salesperson after-sales service input on consumers’ purchase intention through an after-sales service effort coefficient and an cost coefficient. The study found that the after-sales service efforts of live streaming salespeople can significantly increase sales, but the cost (such as a quadratic function relationship) may compress the profit margin. The study further proposes that manufacturers can motivate live streaming salespeople to improve their service efforts by considering fairness issues and realizing more reasonable profit distribution so as to coordinate the conflicts of interest among supply chain members and achieve overall performance optimization.

When the manufacturer takes the lead in after-sales service, the overall profit of the supply chain is the highest, but it is necessary to alleviate fairness issues through moderate concessions to avoid live streaming salespeople reducing service investment or exiting the industry due to unfair distribution; if a live streaming salesperson undertakes after-sales service, although it can increase their own profits in the short term, it is easy to reduce price competitiveness due to cost transfer; especially when fairness concerns are too strong, the total profit of the supply chain may be reduced. In practice, the platform needs to establish a transparent and dynamic revenue-sharing mechanism. The government should strengthen legislation on after-sales responsibility. Only through collaboration can we solve the industry’s pain points of declining income and promote a healthy ecosystem for live streaming e-commerce, shifting from a “traffic game” to “service empowerment.” In summary, the attribution of after-sales responsibility determines efficiency, while the perception of fairness determines the stability of cooperation.

2. Literature Review

This paper primarily engages with the literature on three major aspects of the supply chain: coordination and optimization, concerns regarding fairness, and efforts in after-sales service. Previous research has extensively explored decision-making and coordination issues within supply chains, focusing on conflicts of interest, cooperation mechanisms, and collaborative optimization methods among various supply chain links.

The first aspect, supply chain coordination and optimization, has emerged as a critical research focus in recent years. All research in this area falls into three key themes: (1) The first is the baseline coordination mechanisms that match centralized system performance, established by Reyniers [2]. Some subsequent studies expanded on this work: Ghosh [3] modeled apparel supply chain decisions; Zhang [4] incorporated product greenness in three-tier systems; Gao [5] analyzed power structures in closed-loop chains; and Basiri [6] demonstrated profit advantages of cooperative green channel models. These mechanisms provide frameworks for coordinating multi-party e-commerce livestreaming ecosystems. (2) The second focus, explored by Qi [7], examines the Emergency Response Mechanism within manufacturer–retailer chains. Benjaafar [8] integrated carbon emissions into operational decisions, while Du [9] extended this research to low-carbon preference scenarios. Such research is critical for livestreaming platforms managing flash demand surges and sustainability-driven consumption shifts. (3) The third focus is centralized or decentralized coordination contracts proposed by Giancarlo [10]. Nematollahi [11] demonstrated that collaborative models significantly increase profits and enhance CSR performance, subsequently extending this approach to pharmaceutical supply chains. Contemporary studies explicitly bridge these principles to e-commerce livestreaming: Xin et al. [12] determined that mode selection depends on fee structures, consumer sensitivity, and service costs—essentially a supply chain coordination challenge; Lu et al. [13] investigated dual-channel pharmaceutical pricing under service influences, while Abaku et al. [14] applied AI to demand forecasting. Collectively, these studies confirm that coordinated decision-making enhances supply chain efficiency, profitability, and sustainability principles and is directly applicable to optimizing live streaming e-commerce operations where platform streamer manufacturer alignment, dynamic demand response, and service cost tradeoffs are paramount. However, traditional supply chain coordination research focuses on multi-agent decision-making conflict and does not consider the unique mechanism in live e-commerce. The traditional method of income distribution cannot meet the power inequality between the live streaming salesperson and the manufacturer. Therefore, this paper constructs a more reasonable method of income distribution by introducing the fairness attention coefficient and after-sales service coefficient.

The research on supply chain fairness has expanded significantly, examining fairness concerns across diverse environments, including retail-led chains, closed-loop systems, green electronics, mixed recycling channels, low-carbon supply chains, and blockchain platforms. These studies analyze impacts of fairness coefficients, preferences, blockchain adoption, and government subsidies on decision-making, providing critical insights for enhancing efficiency and sustainability. Loch [15] established that social preferences systematically influence supply chain decisions beyond economic rationality. Building on this, Du [16] and Wu [17] demonstrated in newsvendor settings that win–win outcomes require specific conditions: high demand uncertainty, constrained retailer allocation ranges, and tolerance for unfavorable inequality. Nie [18] revealed that behavioral supply chains cannot be coordinated through quantity discount contracts, while Chen [19] found that retailer fairness concerns improve performance when they bear market uncertainty risks alone. Li [20] linked carbon reduction costs to fairness impacts: high costs trigger retailer fairness concerns, while low costs disproportionately affect manufacturer profits. Du [21] showed that peer fairness boosts retailer performance but may disadvantage manufacturers. Xiao [22] demonstrated that high fairness intensity makes cost-sharing contracts optimal in sustainable chains. Lin et al. [23] explored optimal competitive supply chain decision-making under blockchain technology, considering that manufacturers have mutual fairness concerns, and discussed optimal pricing and coordination strategies. Yang et al. [24] explored operational and financing strategies for agricultural product supply chains under the influence of vertical producer and horizontal seller fairness concerns. Liu et al.’s [25] research analyzed the impact of different fairness concerns on supply chain collaborative innovation. Wu et al. [26] studied a green supply chain with emission reduction funds provided by retailers and found that when the level of fairness concern is low, fairness concerns are harmful to the entire supply chain. However, when the level of fairness concern is high, fairness concerns are beneficial to the entire supply chain. Qiu et al. [27] studied a two-level dual channel supply chain model consisting of manufacturers and retailers and found that increasing subsidies did not alleviate the negative impact of retailers’ fairness concerns on the supply chain, regardless of the channel structure. The theory of fair preference reveals that retailers retaliate for unfair distribution, and the income polarization of live broadcast e-commerce exacerbates this effect. The low bargaining power of small and medium-sized live streaming salespeople makes them more likely to perceive injustice, causing “negative after-sales efforts”, which is not covered by the traditional model.

The third aspect is literature on supply chain after-sales service efforts. The foundational insights were established by analyzing pricing strategies in two-tier chains with service efforts and channel conflicts, highlighting consumer utility functions as key determinants (Cai et al.) [28]. Subsequent studies expanded context-specific applications: Poverty alleviation investments in agricultural e-commerce were modeled, demonstrating the dual impact of government subsidies on social welfare and total income (Sun) [29]. The impact of service effort policies and cost-sharing measures on decentralized dual-channel profits under manufacturer leadership was quantified by Zhao et al. [30]. Sales efforts and concerns about fairness were integrated into the secondary market, focusing on green efficiency and return rates [31,32]. Che et al. [33] proved that subsidy-driven low-carbon strategies alter service effort allocations in dual channels. Cai et al. [34] later identified precise conditions where cost-sharing contracts mutually incentivize manufacturer retailer service effort. Wang et al. [35] compared centralized/decentralized models under demand uncertainty, revealing service efforts’ nonlinear impact on green investment returns; Tian et al. [36] warned that aggressive service adjustments in multi-channel systems trigger dynamic instability, while Zhang et al. [37] synthesized power structures, subsidies, and manufacturer efforts for platform-based green chains. After-sales service research emphasizes its impact on channel competitiveness, and the real-time interaction of live e-commerce makes after-sales service a key point of consumer trust. The live streaming salesperson’s after-sales service can transform after-sales from cost expenditure to the entrance of traffic, overturning the traditional idea that after-sales costs are pure expenditure, and after-sales service can also affect the repurchase rate of products to a certain extent.

Through the above review of the literature, we can see that fairness of profit distribution is an important research topic in the supply chain. This paper aims to explore this issue in depth and combine cutting-edge research results to analyze the impact of fair attention on profit distribution in live streaming e-commerce and propose new theoretical and practical implications for supply chain stability. Table 1 summarizes the specific differences between our model and previous supply chain management research.

Table 1.

Comparison among related studies.

The studies by Xin et al. [12] and Lu et al. [13] indicate that decision-making in e-commerce live streaming is essentially a supply chain coordination problem, influenced by multiple factors. Cai [28] and Zhang [4] emphasized the impact of service effort on consumer demand, providing a basis for incorporating the after-sales service effort coefficient and cost coefficient into the demand function in this study. Although Liu et al. [25] and Nematollahi [11] did not directly involve live streaming e-commerce, their analysis of cooperation mechanisms and fair distribution suggests that this study introduces a fairness concern coefficient to more accurately reflect the psychological and behavioral responses of live streaming salespeople. Existing research has mostly focused on traditional supply chains or dual channel models, lacking in-depth analysis of power inequality, dynamic changes, and after-sales service responsibilities in live streaming e-commerce. On this basis, this study further combines fairness concerns with after-sales service efforts to construct nine decision-making scenarios, filling this research gap.

3. Model Description

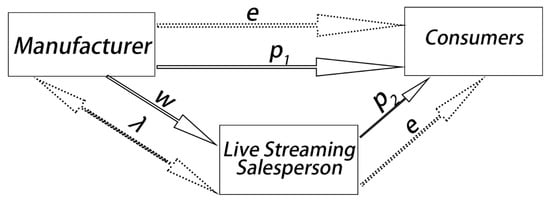

This paper examines a supply chain consisting of the upstream manufacturer and the downstream live broadcast salesperson. The manufacturer serves as the leader in a Stackelberg game, with the live streaming salesperson as the follower. Initially, the manufacturer sets the sales price and wholesale price, decides whether to cover the cost of after-sales service, and considers fairness. Subsequently, the live streaming salesperson establishes the product’s retail price, determines the extent of their after-sales service efforts, and evaluates fairness. The optimal solutions for each model are derived using backward induction. The model architecture is described in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Supply chain structure.

According to research in economics and empirical studies (Loch [15]; Wu [17]), it can be concluded that as a member of the supply chain, the live streaming salesperson attaches great importance to the fairness of profit distribution. Since the manufacturer holds the leading position in the Stackelberg game, they have greater initiative in profit distribution. As the leader of the game, the manufacturer can stimulate the after-sales service effort level of the live streaming salesperson, but this power may make the live streaming salesperson feel that the profit distribution process is unfair. When the live streaming salesperson perceives that their allocated profit is unfair, they may resort to retaliatory measures, sacrificing their own profit to achieve fairness. is used to measure whether the profit distribution is fair, and is used to describe the effort level of after-sales service. The dotted arrow indicates who pays attention to fairness and provides after-sales service.

To illuminate how distinct parameters influence the supply chain, this paper designs several analytical models. Specifically, it develops multiple supply chain frameworks to assess the impact of key factors, with models identified by superscript abbreviations on parameters. These encompass Model B, where neither party bears additional after-sales service costs; Model L, assigning after-sales costs to the live streaming salesperson; Model S, allocating after-sales costs to the manufacturer; Model BL, incorporating live streaming salesperson fairness concerns into Model B; Model BS, integrating manufacturer fairness concerns into Model B; Model LL, incorporating live streaming salesperson fairness concerns into Model L; Model LS, embedding distinct manufacturer fairness concerns into Model L; Model SL, introducing live streaming salesperson fairness concerns into Model S; and Model SS, incorporating distinctive manufacturer fairness concerns into Model S.

3.1. Model Parameters and Variables

The parameters used in the model are listed in Table 2.

Table 2.

Parameters and definitions.

3.1.1. Basic Model

This paper examines a supply chain comprising one manufacturer and one live streaming salesperson. Within this framework, both parties make decisions independently and rationally, each pursuing profit maximization.

In the basic model, the live streaming salesperson’s inadequate attention to fairness and insufficient after-sales service result in significantly lower product sales volume and less intense competition between the manufacturer and the live streamer. Consequently, this article focuses exclusively on the impact of the self-sale price on demand. Aligning with previous research (Mei et al. [38]), we define the customer demand as follows:

Direct channels, , denotes the sales volume attributed to live streamers, stands for the total market size, and captures customers’ price sensitivity coefficient. According to the basic model, we can see that sales volume is intrinsically linked to the sales price. In addition, this paper sets the wholesale price of each unit product to . For the convenience of calculation, this paper sets the sales price of the manufacturer as and the sales price of the live streaming salesperson as .

Therefore, the manufacturer’s profit can be described as follows:

The profit of the live streaming salesperson can be described as follows:

3.1.2. Live Streamers Responsible for After-Sales Service Costs (L Model)

This paper assumes that the live streaming salesperson has the motivation to make certain after-sales service efforts in order to sell more products. This paper uses to represent the after-sales service efforts made by the salesperson, where . After making certain after-sales service efforts, the sales volume of the product can be increased. Therefore, when establishing customer demand, this paper needs to consider the impact of channel preferences on demand. As live streaming salespeople pay more attention to after-sales service, customers are more inclined to choose sellers who provide better after-sales service, which leads to intensified competition between live streaming salespeople and manufacturers. Therefore, we add the sales price of the other side to the demand function to represent the impact of the other side’s price on their own demand. The level of after-sales service effort is similar to other levels of effort previously studied, with a positive impact on the demand for the product (Hu et al. [39]). Therefore, this paper posits that customer demands are determined by , and

The live streaming salesperson may adopt various methods to attract more consumers to purchase their products in order to sell more products. Here, is set as the sensitivity coefficient of customers to after-sales service effort, and is the level of after-sales service effort made by the live streaming salesperson to increase sales.

The manufacturer’s profit can be described as

The profit of the live streaming salesperson can be described as

In order to sell products, the live streaming salesperson may put in a certain amount of effort. When the level of after-sales service efforts is low, the salesperson can achieve more sales with less effort. However, once a live streaming salesperson’s performance reaches certain heights, amplifying after-sales service efforts may yield diminishing returns. There is a quadratic relationship between after-sales service effort cost and after-sales service effort, so this paper describes after-sales service efforts cost as , where is the coefficient of after-sales service effort cost (Xiong et al. [40]).

3.1.3. Manufacturers Responsible for After-Sales Service Costs (S Model)

In Model S, since the manufacturer undertakes better after-sales service, the manufacturer’s demand will increase to a certain extent, which will, in turn, squeeze the sales volume of the live streaming salesperson. Therefore, we set the manufacturer’s demand function to be affected by both price and after-sales service, while the live streaming salesperson demand function is set to be affected only by the sales price between them. In the S model, we assume that the manufacturer takes the initiative to undertake after-sales service. At this time, the sales of the manufacturer and the live streaming salesperson can be described as

The profits of manufacturers and live streaming salespeople can be described as

3.2. Discussion by Case

Considering the fairness concerns of different supply chain participants, this paper will consider the fairness concerns of manufacturers and live streaming salespeople, respectively.

3.2.1. Both Parties Do Not Consider the Issue of Fairness and Do Not Bear the Cost of After-Sales Service (B Model)

In a model neglecting fair attention and after-sales service efforts, the manufacturer and live streaming salesperson, acting as rational, independent players, strategically respond to each other’s potential actions to maximize their own profits, culminating in a Nash equilibrium. First of all, the manufacturer determines the wholesale price and its own sales price, and then the live streaming salesperson determines its own sales price to maximize profits and carries out a reverse solution.

Lemma 1.

Ignoring considerations of fairness and after-sales service, the optimal solution of the model is as follows.

Proof.

The proof process is in Appendix A. □

Traditional pricing is subject to the cost and the price sensitivity coefficient . Ignoring service levels and fairness may underestimate the actual conflict.

3.2.2. Do Not Bear After-Sales Costs, and the Live Streaming Salesperson Pays Attention to Fairness (BL Model)

Based on previous research [40], this paper assumes that the utility of a sales live streaming salesperson with fair attention is

represents the fairness attention coefficient of live streamers who promote products. The equation is used to measure the difference between the profits of live streamers and the manufacturer (Li et al., 2020 [41]). When the difference is positive, the utility of retailers will be compromised, and when the difference is negative, the utility will increase. This means that live streaming salespeople will pay more attention to the relative fairness of their game with the manufacturer, comparing the manufacturer’s profits with their actual profits. However, in this supply chain, due to the dominant position of manufacturers, the profits of live streamers are limited by manufacturers, so the profits of manufacturers are generally higher than those of live streamers.

Lemma 2.

Under the condition that neither party bears the cost of after-sales service and the live streaming salesperson has fair concerns, the optimal solution of the model is

Proof.

The proof process is in Appendix A. □

3.2.3. Do Not Bear After-Sales Costs, and Manufacturers Pay Attention to Fairness (BS Model)

Similar to the utility when the live streaming salesperson with goods produces fairness concerns, the utility of the manufacturer can be expressed as

Lemma 3.

When both parties do not bear the cost of after-sales service and the manufacturer considers the issue of fairness, the optimal solution of the model is as follows.

Proof.

The proof process is in Appendix A. □

From the solutions of the B, BL, and BS models, it can be seen that the manufacturer’s selling price is independent of the fairness concern coefficient.

3.2.4. Neither Side Considers Fairness, and the Live Streaming Salesperson Bears the Cost of After-Sales Service (L Model)

Lemma 4.

The optimal solution of this model is that neither side considers the fairness problem and the live streaming salesperson bears the after-sales service cost:

Proof.

The proof process is in Appendix A. □

According to the calculation results, it can be inferred that for live streaming salespeople, the product with a low after-sales cost coefficient or a high after-sales service sensitivity coefficient, such as some beauty products, may have higher profits for live streaming salespeople.

3.2.5. The Live Streaming Salesperson Bears the Cost of After-Sales Service and Pays Attention to the Fairness of the Live Streaming Salesperson (LL Model)

Lemma 5.

When the live streaming salesperson bears the after-sales service cost and the live streaming salesperson considers the issue of fairness, the optimal solution of the model is as follows.

Proof.

The proof process is in Appendix A. □

From the results of Lemma 5, it can be inferred that the live streaming salesperson bears the pressure of after-sales service costs and fairness issues and needs to sell goods with a high after-sales service sensitivity coefficient to meet its demand for profits, such as 3C electronic products.

3.2.6. The Live Streaming Salesperson Bears the Cost of After-Sales Service and the Manufacturer Pays Attention to the Fairness of the Live Streaming Salesperson (LS Model)

Lemma 6.

The optimal solution of the model is as follows when the manufacturer considers fairness concerns and the live streaming salesperson bears the after-sales service cost.

Proof.

The proof process is in Appendix A. □

3.2.7. The Manufacturer Shall Bear the Cost of After-Sales Service (S Model)

Lemma 7.

When the manufacturer bears the after-sales service cost and neither party considers the issue of fairness, the optimal solution of the model is as follows.

Proof.

The proof process is in Appendix A. □

At this time, the manufacturer should lead the after-sales cost of higher after-sales service cost categories (such as large household appliances) and reduce costs through specialization and scale.

3.2.8. The Manufacturer Bears the Cost of After-Sales Service, and the Live Streaming Salesperson Pays Attention to Fairness (SL Model)

Lemma 8.

When the manufacturer bears the after-sales service cost and the live streaming salesperson considers the issue of fairness, the optimal solution of the model is as follows.

Proof.

The proof process is in Appendix A. □

3.2.9. Manufacturers Bear the Cost of After-Sales Service and Pay Attention to the Fairness of Manufacturers (SS Model)

Lemma 9.

When the manufacturer bears the after-sales service cost and the manufacturer considers fairness concerns, the optimal solution of the model is as follows.

Proof.

The proof process is in Appendix A. □

4. Sensitivity Analysis and Model Comparison

4.1. Sensitivity Analysis

Based on the optimal decisions and profits obtained, it can be seen that various factors will impact profit distribution in the supply chain. This paper compares and analyzes models to identify the most suitable profit distribution method for the supplier and live streamers. This paper analyzes the influence of various dependent parameters in the profit function on the equilibrium solution in detail. By solving the first derivative of each parameter, sensitivity analysis can be performed.

Proposition 1.

In the B, BL, and BS models, has a positive impact on , , and . In the BL model, has a positive impact on , and has a negative impact on manufacturer profits.

Proof.

The proof process is in Appendix B. □

The parameter reflects the sensitivity of consumers to price changes. When is high, consumers react more strongly to price changes, which requires all parties in the supply chain to be more cautious when pricing. In order to ensure profits in fierce price competition, all parties often choose to increase the overall pricing level of their products to compensate for potential sales fluctuations caused by highly sensitive consumers, resulting in an increase in retail prices and .

In consideration of fairness concerns for broadcasters, although fairness considerations have been introduced, consumers are still very sensitive to prices, and broadcasters and suppliers will still face the same market pressure when determining retail prices. Therefore, it is necessary to set higher prices and to balance the game between sales and profits. In order to maintain long-term cooperative relationships and market image, suppliers will provide more compensation to live streaming salespeople in profit distribution. At this point, the commission w will increase as a result, reflecting the concession effect of fairness requirements. In order to demonstrate fairness, suppliers have to make concessions in pricing or profit distribution, transferring some profits to the live streaming salesperson. This leads to a decrease in the actual profit share obtained by the supplier itself while the overall price level is relatively high.

Proposition 2.

In the L and LS models, the sensitivity coefficient of after-sales efforts has a negative impact on and a positive impact on . In the LL model, the sensitivity coefficient of after-sales efforts has a positive impact on .

Proof.

The proof process is in Appendix B. □

When the live streaming salesperson bears the cost of after-sales service, a higher means that consumers are very sensitive to the quality of after-sales service. If the service is insufficient, it will directly affect consumers’ willingness to purchase. Therefore, in order to reduce negative reactions caused by insufficient after-sales service, maintain market competitiveness and attractiveness, live streaming salespeople may have to lower the product price in order to attract consumers. At the same time, as consumers are very sensitive to the quality of after-sales service, broadcasters must increase their efforts and investment in after-sales service to avoid losing consumers or having consumers complain due to unsatisfactory after-sales experience, that is, to improve . When the live streaming salesperson considers fairness issues, the impact of on becomes positive. The live streaming salesperson is unwilling to unilaterally lower the selling price to bear all after-sales risks due to the high sensitivity of consumers. In order to achieve risk sharing and benefit balance, live streaming salespeople may require suppliers to also share some of the costs or compensate for their higher investment in after-sales service by increasing the selling price .

Proposition 3.

In the S model, b has a positive impact on , , and . In the S, SL, and SS models, has a positive impact on supplier profits, and the coefficient of after-sales effort cost has a negative impact on supplier profits. In the SL model, has a negative impact on supplier profits, and in the SS model, has a negative impact on the live streaming salesperson profits.

Proof.

The proof process is in Appendix B. □

has a positive impact on sales prices and wholesale prices, similar to the situation where neither party bears the cost of after-sales service. If suppliers have lower service costs and efficient after-sales systems, they can increase the market premium of their products by improving service quality in the face of a higher beta, thereby increasing overall profits. That is to say, a higher allows suppliers to gain more pricing power and profit margins in service competition. The cost coefficient of after-sales effort reflects the cost that suppliers need to pay when providing a certain level of after-sales service. If the cost coefficient of after-sales efforts is high, it means that more costs need to be paid to achieve the expected service level. This cost pressure will force suppliers to make concessions in pricing while directly eroding profit margins.

In consideration of fairness, suppliers will provide more compensation to live streaming salespeople in profit distribution to maintain long-term, stable cooperative relationships. That is to say, suppliers need to transfer a portion of their overall profits to live streaming salespeople, resulting in a decrease in their own profits. The live streaming salesperson can receive more profit sharing or compensation for concessions. And the live streaming salesperson no longer simply bears all the after-sales risks but obtains certain protection in pricing and profit sharing, thereby increasing their profit level.

Proposition 4.

In the BS model and the SS model, has a positive impact on and live streaming salesperson profits, and has a positive impact on .

Proof.

The proof process is in Appendix B. □

When suppliers consider fairness, they will provide more reasonable compensation to the live streaming salesperson in profit distribution. This allows them to not only increase but also gain more profits when facing higher consumer price sensitivity. In other words, the positive effect of is partially transmitted to the live streaming salesperson’s profit in this situation, as the supplier considers fairness issues and allows the live streaming salesperson to share the premium generated by increasing . When suppliers place greater emphasis on fairness, they tend to make concessions in profit sharing with broadcasters. To ensure a balance of interests between both parties, a live streaming salesperson may need to adjust the sales price to achieve a more reasonable distribution. Improving helps to redistribute profits throughout the entire supply chain, allowing broadcasters to obtain more reasonable profits while suppliers can still maintain fairness in the overall pricing structure.

4.2. Model Comparison

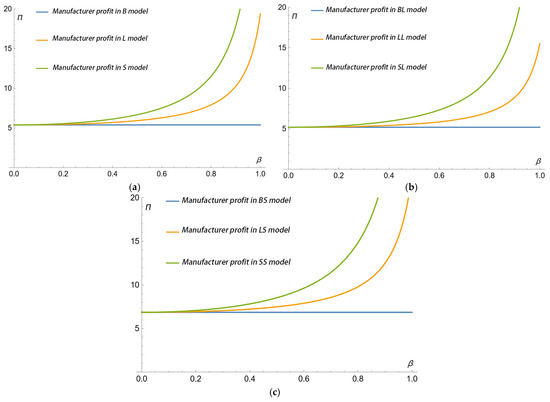

Proposition 5.

In the B, BL, and BS models, and are the highest; in the S, SL, and SS models, and are the lowest.

When neither party in the supply chain bears after-sales costs or only considers equity concerns, the live streaming salesperson or supplier has little incentive to reduce costs. In order to cover potential after-sales risks (such as returns and maintenance), the live streaming salesperson needs to increase the risk premium in the pricing, resulting in the sales price being pushed up. However, when the supplier bears the after-sales cost, the supplier can rely on the mature after-sales system to provide services at a lower marginal cost. In addition, as the leader of the supply chain, suppliers can attract live streaming salespeople to cooperate by optimizing pricing strategies, such as reducing wholesale prices, so as to lower retail prices and enhance market competitiveness.

For suppliers, in the S, SL, and SS models, they can reduce after-sales costs through professional management while mastering the pricing power, so their profit has been significantly improved. For the live streaming salesperson, when suppliers bear after-sales costs, the live streaming salesperson can stimulate consumers to buy at a lower retail price. Although live streaming salespeople do not bear after-sales costs, their profits are stable or slightly increased through sales growth and supplier concessions. However, in the B, BL, and BS models, the fair demands of live streaming salespeople force the supplier to reduce the wholesale price, and the live streaming salesperson forces the supplier to adopt a higher retail price to suppress sales, and the profit of the supplier is compressed.

Proposition 6.

In the S, SL, and SS models, the profit of the supplier is the highest; comparing the B, BL, and BS models, in the BL model, the profit of the supplier is low.

Proof.

The proof process is in Appendix B. □

When the supplier bears the after-sales service cost, the supplier significantly reduces the unit after-sales cost through the centralized and standardized after-sales system. At the same time, as the leader of the game, the supplier can also pass on part of the after-sales cost to live streaming salespeople or consumers by setting a higher wholesale price while retaining a larger profit margin. When the supplier bears the after-sales service cost and considers the fairness issue, the supplier alleviates the sense of injustice of the live streaming salesperson by transferring part of the profit and avoids the retaliatory behavior. Although the profit is slightly lower than that of the S model, it is still significantly higher than that of other models, as the sales volume increase and long-term cooperation stability compensate for the short-term profit.

When the live streaming salesperson pays attention to fairness and both parties do not bear the after-sales cost, the perceived unfairness of the live streaming salesperson may reduce after-sales service efforts, resulting in decreased consumer satisfaction and indirectly increasing the brand maintenance cost of the supplier. Moreover, the live streaming salesperson will adopt a higher retail price to weaken the purchase intention of price-sensitive consumers and further reduce sales and profits, and part of the profit allocated by live streaming salesperson to the supplier will be reduced to a certain extent. The result is lower profit margins for suppliers than would otherwise be the case.

Proposition 7.

In the L, LL, d LS model, the live streaming salesperson has the highest profit; when comparing these three models, in the LL model, the manufacturer has the lowest profit.

Proof.

The proof process is in Appendix B. □

When the live streaming salesperson bears the after-sales service cost and consumers are not sensitive to price, the live streaming salesperson transfers the after-sales cost through raising the retail price to ensure the maximum profit. This can also let suppliers yield profits through supply chain bargaining to further enhance their own profits. In addition, when the live streaming salesperson undertakes after-sales service, they will be more motivated to improve the quality of after-sales service, enhance user satisfaction, enhance consumer stickiness, and indirectly promote sales growth. Under the LL model, the lowest profit of suppliers is due to the fact that live streaming salespeople think they bear too much cost when they bear the after-sales service cost, requiring suppliers to make greater concessions may require suppliers to achieve a fairer profit distribution method and reduce their earnings. In addition, under the LL model, the live streaming salesperson also transfers after-sales costs by raising prices, which further weakens the pricing power of suppliers, resulting in the minimum profit of suppliers.

Proposition 8.

In the S, SL, and SS models, the total supply chain profit is the highest. The overall profit of the supply chain can be maximized when the manufacturer undertakes after-sales service.

Proof.

The proof process is in Appendix B. □

When the supplier bears the cost of after-sales service, the supplier can effectively reduce the cost of after-sales service by virtue of standardization and scale, and high-quality after-sales service helps to enhance consumers’ trust in the brand, enhance loyalty, and promote repurchase behavior. When suppliers undertake after-sales service, they are more inclined to improve product quality to reduce after-sales cost, thus forming a positive cycle and increasing the overall revenue of the supply chain. When suppliers bear the cost of after-sales service, they can also strengthen the coordination of the supply chain so that live streaming salespeople can put more resources into marketing, fan operation, and sales strategies; enhance the promotion effect; and improve sales. The after-sales service is undertaken by the supplier. The live streaming salesperson does not need to increase the after-sales cost in the product cost but can sell the product at a more competitive price to improve the market share. After-sales service costs borne by suppliers can significantly improve the overall profits of the supply chain, optimize resource allocation, improve operational efficiency, and make the supply chain more stable and efficient.

4.3. Numerical Research

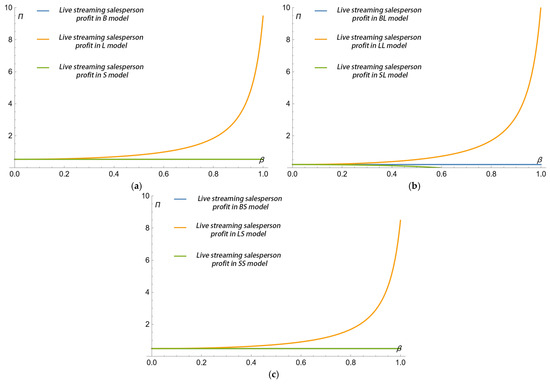

In order to further explore the optimal strategies and profits of different models with respect to the changing trends of various parameters, this section will conduct numerical analysis. In this section, we classify the B, L, and S models into a group; the three models in this group only consider who bears the after-sales service cost and do not consider the issue of fairness. We continue to group the BL, LL, and SL models into a group; in this group, the three models consider the fairness concerns of live streaming salespeople based on the B, L, and S models. The BS, LS, and SS models are grouped into a group; in this group, the three models consider the fairness concerns of manufacturers on the basis of the B, L, and S models.

4.3.1. The Impact of Fairness Concern Coefficient on Profits

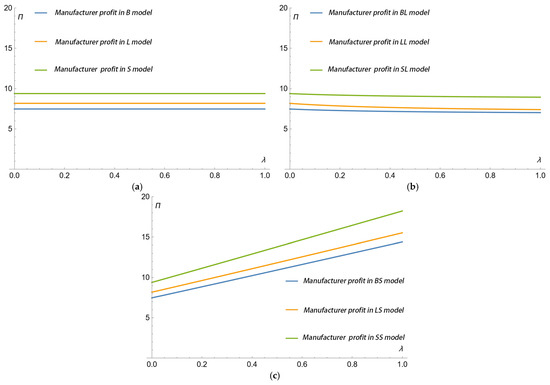

In this section, we will investigate the impact of the fairness concern coefficient on the overall profits of manufacturers, live streaming salespeople, and supply chains. We label the parameters used in the image below it.

In Figure 2, we will take the B, L, and S models that only consider after-sales service and do not consider fairness issues as the first group, consider after-sales service and the live streaming salesperson’s consideration of fairness issues as the second group, and consider after-sales service and the manufacturer’s consideration of fairness issues as the third group. Figure 2a shows that the profit of suppliers is the highest when they bear the after-sales service cost. When suppliers take the initiative to bear the after-sales cost, they can often control the after-sales link, set more favorable wholesale prices or cooperation terms, and, with the help of the large-scale and professional after-sales system, reduce the actual cost to a lower level, so as to obtain higher profits. Figure 2b shows that the model with the highest profit when the supplier still bears the after-sales service cost, and with the increase in the fairness concern coefficient , the profit of the supplier has a downward trend, indicating that the live streaming salesperson requires a more equitable profit distribution in the negotiation or income distribution, which will reduce the profit of the supplier to a certain extent. Figure 2c shows that the profit of suppliers is the highest when they bear the after-sales service cost. With the increase in the fairness concern coefficient , the profit of suppliers increases instead. It may be explained that when suppliers care about fairness, pricing and distribution strategies can better promote the sales enthusiasm or cooperation stability of live streaming salespeople, achieve a win–win effect of cooperation, and ultimately improve the profits of suppliers. For the supplier, the best decision is that the supplier should bear the cost of after-sales service and consider the issue of fairness.

Figure 2.

The profit of the manufacturer varies with the fairness attention coefficient ( = 0.15, = 5.5, = 0.14, = 0.25, = 0.25). (a) Profit of the manufacturer when neither party considers fairness; (b) profit of the manufacturer when the live streaming salesperson considers fairness; and (c) profit of the manufacturer when considering fairness issues.

We used the same grouping method as in Figure 2, Figure 3, Figure 4 and Figure 5. Figure 3a shows that live streaming salespeople’s profit is maximized when they bear after-sales service costs. This could occur because the enhanced after-sales service draws more consumers toward live streaming sales, offsetting the costs of after-sales service while generating extra profits. Figure 3b shows that when the live streaming salesperson bears the after-sales service cost and the live streaming salesperson pays attention to fairness, the profit is much higher than the other two cases. When the live streaming salesperson considers fairness, the live streaming salesperson’s profit is particularly sensitive to the after-sales service cost. With the increase in the fairness concern coefficient , the live streaming salesperson’s profits have declined in all three cases, indicating that the live streaming salesperson’s excessive consideration of distribution fairness may lead to problems in the live streaming salesperson’s cooperation with suppliers and affect their own profits and the profits of the entire supply chain. Figure 3c shows that when the live streaming salesperson bears the cost of after-sales service, the live streaming salesperson’s profit is the largest. The best choice for the live streaming salesperson is to bear the cost of after-sales service for itself, and the supplier considers the issue of fairness, or both parties do not consider the issue of fairness. Combined with the benefits of the whole supply chain, the best choice for both parties is to bear the after-sales service cost for the supplier. Neither party considers fairness, or the supplier considers fairness.

Figure 3.

Change trend of the live streaming salesperson’s profit with a fairness attention coefficient ( = 0.2, = 5.5, = 0.15, = 0.2, = 0.3). (a) Profit of live streaming salesperson when neither party considers fairness; (b) profit of the live streaming salesperson when the live streaming salesperson considers fairness; and (c) profit of the live streaming salesperson when considering fairness issues.

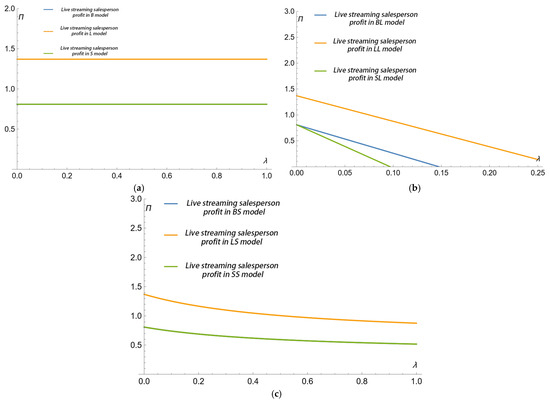

Figure 4.

The impact of the after-sales service sensitivity coefficient on the profits of manufacturers and live streamers ( = 0.4, = 0.3, = 5, = 0.6, = 0.3). (a) Profit of manufacturers when both parties do not consider fairness concerns; (b) profit of the manufacturer when the live streaming salesperson considers attention to fairness; and (c) profit of manufacturers when considering fairness concerns.

Figure 5.

Changes in the after-sales service sensitivity coefficient of manufacturer sales prices ( = 0.4, = 5, = 0.1, = 0.6, = 0.3). (a) The profit of the live streaming salesperson who does not consider fairness concerns on both sides; (b) profit of the live streaming salesperson considering fairness concerns; and (c) profit of the live streaming salesperson considering fairness concerns in manufacturers.

4.3.2. The Impact of After-Sales Service Efforts on Profits

Figure 4 reveals that when the supplier bears the after-sales service cost, the profit of the supplier is always the highest, indicating that once the supplier has mastered the after-sales link, with the help of large-scale management, professional services, and pricing power, it can maximize the overall profit and benefit more when increases. If the live streaming salesperson bears the cost of the after-sales service and the supplier’s income is slightly higher than that of both parties who do not bear the cost of the after-sales service, the supplier will no longer face the risk and cost of after-sales service on behalf of the live streaming salesperson. Therefore, the wholesale price can be increased or the profit can be reduced accordingly, so as to obtain higher profits with the increase in , but the range is less than that of the situation where the live streaming salesperson bears the cost of the after-sales service. The profit of suppliers is always the lowest when neither party bears the cost of after-sales service, indicating that the lack of high-quality after-sales service in this case may reduce the market attractiveness and make it difficult for suppliers’ profits to benefit from the growth of .

It can be seen from Figure 5 that the profit of the live streaming salesperson is the highest when the live streaming salesperson bears the cost of after-sales service. It indicates that when the live streaming salesperson bears the cost of after-sales service, a certain premium will be added to the terminal retail price of the product in order to cover the potential risks of return and replacement, maintenance, etc. Given that live streaming salespeople directly engage with consumers and possess flexibility in pricing and promotional strategies, they can effectively transmit this premium to the market, thereby enhancing their profit levels. By enhancing the after-sales experience, live streaming hosts not only mitigate disputes but also strengthen fan loyalty and drive repurchase rates. In the long run, this will also help live streaming salespersons’ profit growth. In Figure 5b, the profit of the live streaming salesperson decreases with the increase in the after-sales service sensitivity coefficient when the live streaming salesperson considers fair attention. This may be because with the increase in the after-sales service sensitivity coefficient, the after-sales service cost of suppliers will also increase. The supplier should prioritize their own sustainable development, compelling the live streaming salesperson to either passively absorb a portion of the costs or sacrifice a share of their profits to foster supply chain collaboration.

The results of this research are consistent with the existing research system presented in the literature review and provide useful extensions and supplements, revealing more complex dynamic relationships in specific contexts. The specific comparison is as follows: The central finding of this research reveals that suppliers’ absorption of after-sales service expenses maximizes total supply chain profit. This is consistent with the research conclusions of Giannocaro [10], Basiri [6], and Nematollahi [11]. This paper further refines and deepens the impact of fairness concerns. Li [20] pointed out that the impact of fairness concerns varies depending on the cost structure, and this study specifically reveals that the direction of this impact is closely related to the cost bearers. This study confirms the positive promotion effect of after-sales service efforts on demand. This study also finds that after-sales service efforts can be transformed into traffic entry points and trust-building tools, thereby overturning the traditional concept that after-sales is a pure expenditure. This is an innovative application and development of Cai’s [28], Zhao’s [30], and others’ studies in live streaming scenarios. The research results support the modeling approach of quantifying service effort into cost coefficients and sensitivity coefficients. There are contextual differences between the results of this study and the conclusions of a few literature sources. Notably, Xiao [22] discovered that cost-sharing contracts proved optimal under conditions of high fairness concern intensity. Intriguingly, this research reveals that when the live streaming salesperson shoulders the after-sales cost (the L model), excessive fairness concerns (the LL model) can become detrimental to the supply chain. This divergence precisely demonstrates the moderating effect of the decision-making environment on the fairness concern effect, indicating that a certain research conclusion cannot be simply generalized. This study reveals a unique issue in live streaming e-commerce that has not been fully explored in the literature: the power and responsibility mismatch between supplier-led pricing and anchor-led services. This unique contradiction is a new manifestation of “channel conflict” in the traditional supply chain literature in the era of live streaming, and this study provides an in-depth analysis of its mechanism. In summary, this research is not at odds with the existing literature but rather based on a mature theoretical foundation; applying it to the challenging new field of live streaming e-commerce; and verifying, refining, and expanding upon it. The results strongly support core theories such as supply chain coordination, fairness concerns, and service efforts, while revealing the more complex interaction relationships between these factors under specific power structures, cost sharing, and interaction patterns, providing a new theoretical and empirical basis for understanding and developing live streaming e-commerce supply chain management.

5. Conclusions

This study concentrates on the strategy of post-sale service cost-sharing and profit distribution within the supply chain of live streaming e-commerce, emphasizing the impact of equity concerns on the decision-making processes of all supply chain parties and the collective benefit. Utilizing a mathematical model that incorporates price sensitivity, after-sales service sensitivity, after-sales service cost, and equity concern parameters, we conducted sensitivity analyses and model comparisons to discuss the profit variations and overall income of suppliers and live streaming salespeople under various cost commitment and equity concern scenarios.

First of all, the results show that when the supplier bears the after-sales service cost; due to its mature after-sales system and scale effect, it can provide high-quality services at a lower cost, thus significantly improving the overall efficiency of the supply chain. In this case, the consumer’s sensitivity to price allows the retail price to be appropriately increased, and the wholesale price also increases accordingly. At the same time, the increase in the after-sales service sensitivity coefficient enables suppliers to obtain higher product premiums by improving service quality, which promotes the profit growth of suppliers.

In contrast, when live streaming salespeople bear after-sales service costs, they not only need to face the direct costs and risks caused by after-sales problems but also must add a risk premium to pricing to make up for possible after-sales losses, which inhibits pricing to a certain extent and weakens their own profits. Sensitivity analysis shows that the increase in the after-sales effort cost coefficient has a negative impact on pricing and profit, which means that increasing the after-sales service input cost will reduce the profit margin of all parties to a certain extent.

After considering the fairness problem further, the model introduces the fairness concern parameter. The role of the fair mechanism is mainly reflected in the profit distribution: in the supply chain, in order to maintain the long-term cooperative relationship and market image with live streaming salespeople, the supplier will make concessions in profit distribution, that is, take the initiative to transfer part of the profit to the live streaming salesperson to achieve a balance of interests. In addition, the fair mechanism will also affect the setting of some price variables to compensate for the deviation of profit distribution between the two sides so as to achieve the purpose of balancing risk and return.

From the perspective of suppliers, when they bear the after-sales service cost, they can give full play to their advantages in professional management and economies of scale and achieve higher product pricing at lower service costs. In this case, the positive effect of price sensitivity is reflected, and the profit of suppliers is significantly increased. However, if the issue of fairness is over-considered on this basis, suppliers need to make big concessions in profit distribution, resulting in their own profits being significantly compressed. Therefore, for suppliers, the optimal mode is to bear the after-sales service cost, while maintaining a moderate or even a low level of fair attention, in order to give full play to their cost control advantages and obtain maximum profits. From the perspective of the live streaming salesperson, although the live streaming salesperson has higher profits when they bear after-sales service costs, they will bear some risks and costs brought by the after-sales service, and the overall profit of the supply chain will be low. Therefore, for the live streaming salesperson, the optimal situation is that the supplier bears the after-sales service cost. In this case, the live streaming salesperson can avoid the high costs and risks brought by after-sales services and enjoy higher product premiums and profits with the professional operation support of suppliers. After the introduction of a fair mechanism, the live streaming salesperson can also obtain additional compensation in the profit distribution so as to further enhance their status and income in the supply chain.

The main limitation of this study is that the model constructed fails to fully consider various complex after-sales issues in live streaming e-commerce, such as the differences in after-sales costs of different categories of goods. Future research should focus on the following avenues: investigating variations in after-sale costs across distinct commodity categories and assessing how these differences influence profit distribution mechanisms within supply chains, and rigorously examining customer feedback systems pertaining to post-purchase service quality, with particular emphasis on how optimizing these service mechanisms can significantly improve overall supply chain efficiency.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, W.L.; methodology, W.L.; software, Y.Z.; validation, Y.Z.; formal analysis, Y.Z.; investigation, J.S.; data curation, Y.Z. and J.S.; writing—original draft preparation, C.W.; writing—review and editing, X.M.; supervision, X.M.; project administration, W.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

Special fund for Postdoctoral Innovation Project of Shandong Province (Grant no. 201903025).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

Appendix A.1. Basic Models (B Model)

Firstly, the manufacturer determines their sales price and wholesale price to maximize their profit, and then the live streaming salesperson determines their sale price and after-sales service effort level to maximize their profit.

The income function of the live streaming salesperson finds the partial derivative of the sales price so that it is 0. We can solve the expression of :

Substitute into the manufacturer’s revenue function and calculate the partial derivatives with respect to and e, making the partial derivatives 0. Resolve the expressions for and w.

By inputting the obtained , , and w into the profit function, the profits of the manufacturer and live streaming salesperson can be obtained:

Appendix A.2. Live Streamers Responsible for After-Sales Service Costs (L Model)

Firstly, the manufacturer determines their sales price and wholesale price to maximize their profit, and then the sales live streaming salesperson determines their sales price and after-sales service effort level to maximize their profit.

Find the partial derivative of the income function of the live streaming salesperson with respect to the sales price and after-sales service effort level so that the partial derivative is 0.

Solve the two equations yields the expressions for and e:

By substituting and into the manufacturer’s revenue function, we can obtain

Find the partial derivative of the profit function of the manufacturer with respect to and so that the partial derivative is 0.

Solve the system of equations composed of these two equations:

Substitute the obtained into the functions of and determined by (A11) and (A12).

By inputting the obtained , , , and e into the manufacturer’s profit function and the live streaming salesperson’s profit function , we can obtain the profits of the manufacturer and the live streaming salesperson in the decentralized model without attention to fairness:

Appendix A.3. Manufacturers Responsible for After-Sales Service Costs (S Model)

Firstly, the manufacturer determines their sales price and wholesale price to maximize their profit, and then the live streaming salesperson determines their sales price and after-sales service effort level to maximize their profit.

Find the partial derivative of the income function of the live streaming salesperson with respect to the sales price so that the partial derivative is 0. The expression of can be solved as follows.

Substitute into the manufacturer’s revenue function and calculate the partial derivatives with respect to , and , making the partial derivatives 0. Resolve the expressions for and

By inputting the obtained , , and into the profit function, the profits of the manufacturer and live streamers can be obtained:

Appendix A.4. Basic Model Live Streaming Salesperson Considers Fairness Issues (BL Model)

Based on the basic model and the fairness attention coefficient, the optimal solution of the model can be obtained:

Based on the basic model and utility function, the optimal utility of broadcasters and manufacturer profits considering fairness can be obtained:

Appendix A.5. Basic Model Manufacturer Considers Fairness Issues (BS Model)

Based on the basic model and the fairness attention coefficient, the optimal solution of the model can be obtained:

Based on the basic model and utility function, the optimal utility of broadcasters and manufacturer profits considering fairness can be obtained

Appendix A.6. Live Streamers Responsible for After-Sales Service Costs, Live Streaming Salesperson Fairness Concerns (LL Model)

Appendix A.7. Live Streamers Responsible for After-Sales Service Costs, Manufacturer Fairness Concerns (LS Model)

Appendix A.8. The Manufacturer Bears the Cost of After-Sales Service, and the Live Streaming Salesperson Pays Attention to Fairness (SL Model)

Appendix A.9. The Manufacturer Bears the Cost of After-Sales Service, and the Manufacturer Pays Attention to Fairness (SS Model)

Appendix B

Appendix B.1. Proof of Proposition 1

Based on the value ranges of each parameter, we can determine the relationship in size between the partial derivatives of some parameters and zero.

B model

BL model

BS model

Appendix B.2. Proof of Proposition 2

L model

LL model

LS model

Appendix B.3. Proof of Proposition 3

S model

SL model

SS model

Appendix B.4. Proof of Proposition 4

BS model

SS model

Appendix B.5. Proof of Proposition 5

When ,

Appendix B.6. Proof of Proposition 6

When ,

Appendix B.7. Proof of Proposition 7

When ,

Appendix B.8. Proof of Proposition 8

When ,

References

- China International E-commerce Center. China Live E-commerce High Quality Development Report (2024); China International E-commerce Center Research Institute: Beijing, China, 2024; p. 3. [Google Scholar]

- Savaskan, R.C.; Bhattacharya, S.; Van Wassenhove, L.N. Closed-loop supply chain models with product remanufacturing. Manag. Sci. 2004, 502, 239–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, D.; Shah, J. A comparative analysis of greening policies across supply chain structures. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2012, 1352, 568–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.T.; Liu, L.P. Research on coordination mechanism in three-level green supply chain under non-cooperative game. Appl. Math. Model. 2013, 37, 3369–3379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, J.; Han, H.; Hou, L.; Wang, H. Pricing and effort decisions in a closed-loop supply chain under different channel power structures. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 112, 2043–2057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basiri, Z.; Heydari, J. A mathematical model for green supply chain coordination with substitutable products. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 145, 232–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, X.; Bard, J.F.; Yu, G. Supply chain coordination with demand disruptions. Omega 2004, 324, 301–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benjaafar, S.; Li, Y.; Daskin, M. Carbon footprint and the management of supply chains: Insights from simple models. IEEE Trans. Autom. Sci. Eng. 2013, 101, 99–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, S.; Zhu, J.; Jiao, H.; Ye, W. Game-theoretical analysis for supply chain with consumer preference to low carbon. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2015, 5312, 3753–3768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giannoccaro, I.; Pontrandolfo, P. Supply chain coordination by revenue sharing contracts. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2004, 892, 131–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nematollahi, M.; Hosseini-Motlagh, S.M.; Heydari, J. Coordination of social responsibility and order quantity in a two-echelon supply chain: A collaborative decision-making perspective. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2017, 184, 107–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xin, B.; Hao, Y.; Xie, L. Strategic product showcasing mode of E-commerce live streaming. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2023, 73, 103360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Q.; Liu, Q.; Wang, Y.; Guan, M.; Zhou, Z.; Wu, Y.; Zhang, J. Pricing strategy research in the dual-channel pharmaceutical supply chain considering service. Front. Public Health 2024, 12, 1265171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abaku, G.A.; Abaku, E.A.; Edunjobi, T.E.; Odimarha, A.C. Theoretical approaches to AI in supply chain optimization: Pathways to efficiency and resilience. Int. J. Sci. Technol. Res. Arch. 2024, 61, 92–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loch, C.H.; Wu, Y. Social preferences and supply chain performance: An experimental study. Manag. Sci. 2008, 5411, 1835–1849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, S.; Nie, T.; Chu, C.; Yu, Y. Newsvendor model for a dyadic supply chain with Nash bargaining fairness concerns. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2014, 5217, 5070–5085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Nederlof, J.A. Fairness in selling to the newsvendor. Prod. Oper. Manag. 2014, 2311, 2002–2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nie, T.; Du, S. Dual-fairness supply chain with quantity discount contracts. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2017, 2592, 491–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Zhou, Y.W.; Zhong, Y. A pricing/ordering model for a dyadic supply chain with buyback guarantee financing and fairness concerns. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2017, 5518, 5287–5304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Xiao, X.; Qiu, Y. Price and carbon emission reduction decisions and revenue-sharing contract considering fairness concerns. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 190, 303–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, S.; Wei, L.; Zhu, Y.; Nie, T. Peer-regarding fairness in supply chain. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2018, 5610, 3384–3396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Q.; Chen, L.; Xie, M.; Wang, C. Optimal contract design in sustainable supply chain: Interactive impacts of fairness concern and overconfidence. J. Oper. Res. Soc. 2021, 727, 1505–1524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, S.; Zhang, G. Competitive supply chain pricing and coordination strategies considering fairness concerns under blockchain technology. Econ. Manag. Rev. 2024, 20245, 122–134. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, H.; Luo, M.; Shao, E. Financing strategies for agricultural product supply chains considering preservation efforts and equity concerns. Oper. Res. Manag. 2024, 20, 2307–2331. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, H.; Hao, H.; Wei, Z.; Su, J.; Qu, Y.; Zhu, B. The effects of different fairness reference points on supply chain members’ collaborative innovation. Ann. Oper. Res. 2024; advance online publication. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, H.; Weng, J.; Li, G.; Zheng, H. Green subsidy strategies and fairness concern in a capital-constrained supply chain. Transp. Res. Part E Logist. Transp. Rev. 2024, 192, 107563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, J.; Xu, X.; Yang, Y. Carbon emission reduction and channel development strategies under government subsidy and retailers’ fairness concerns. Electron. Commer. Res. Appl. 2024, 68, 101867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, H.; Qing, S. Pricing strategies in a two-echelon supply chain with after-sales service efforts and channel conflicts. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 83238–83247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, L. Differential game research based on industrial poverty alleviation in e-commerce environment. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2020, 4405, 052098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.; You, J.; Fang, S.C. A dual-channel supply chain problem with resource-utilization penalty: Who can benefit from after-sales service effort? J. Ind. Manag. Optim. 2020, 174, 2837–2853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoo, S.H.; Cheong, T. Inventory model for sustainable operations of a closed-loop supply chain: Role of a third-party refurbisher. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 315, 127810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Shao, E.; Gong, Y.; Guan, X. Decision-making for green supply chain considering fairness concern based on trade credit. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 67684–67695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Che, C.; Chen, Y.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, Z. The impact of different government subsidy methods on low-carbon emission reduction strategies in dual-channel supply chain. Complexity 2021, 2021, 6668243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, J.; Dong, R.; Zeng, Z.; Hu, X. Supply chain competition models with strategic customers considering after-sales service effort. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2022, 172, 108540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Song, Q. Pricing policies for dual-channel supply chain with green investment and after-sales service effort under uncertain demand. Math. Comput. Simul. 2020, 171, 79–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Y.; Ma, J.; Xie, L.; Koivumäki, T.; Seppänen, V. Coordination and control of multi-channel supply chain driven by consumers’ channel preference and after-sales service effort. Chaos Solitons Fractals 2020, 132, 109583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, N.; Wu, J.; Li, B.; Fu, D. Research on green closed-loop supply chain considering manufacturer’s fairness concerns and after-sales service effort. J. Theor. Appl. Electron. Commer. Res. 2023, 18, 333–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mei, Y.; Cao, K.; Liu, Y.; Mangla, S.K. Effects of manufacturer fairness concerns and carbon emission reduction investment on pricing decisions under countervailing power. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 461, 142356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Meng, L.; Huang, Z. Pricing and after-sales service effort decisions in a closed-loop supply chain considering the network externality of remanufactured product. Sustainability 2023, 157, 5771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, X.; Fang, J.; Yuan, J.; Jin, P. Research on the incentive mechanism and coordination of fresh agricultural product supply chain under the behavioral preference of league members. Chin. Manag. Sci. 2019, 274, 115–126. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Huang, Y. The impacts of fairness concern and different business objectives on the complexity of dual-channel value chains. Complexity 2020, 2020, 8814878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).