Abstract

Telework has become a crucial element of the modern business landscape, driven by transformations sparked by multiple global crises. The transition from traditional, in-office work to telework, sometimes mandated by revolutionary circumstances (such as the COVID-19 pandemic), has highlighted both the advantages and challenges associated with this mode of work organization. In this context, the present study examines the effects of telework as experienced by employees and managers during two key periods: the COVID-19 pandemic and the introduction of chatbots. Through 24 interviews conducted and analyzed across these two timeframes (2021 and 2024) using NVivo 14 Windows software, the data were organized and interpreted within the framework of the Job Demands–Resources (JD-R) model. The main findings focus on organizational communication, sustainability, and work efficiency, while also highlighting associated benefits and drawbacks. The results demonstrate the importance of adapting organizational resources to meet growing job demands in order to maintain desired levels of efficiency and effectiveness while avoiding burnout, productivity declines, or other negative outcomes in the context of telework. This research contributes to understanding the evolution of telework by offering practical insights for sustaining high levels of motivation and workforce engagement in achieving organizational objectives in the hybrid work era. This paper emphasizes the significance of the JD-R Model in analyzing dynamic work environments, providing relevant perspectives for organizations on the continuously evolving dimensions of job demands, job resources, and outcomes.

1. Introduction

In a constantly changing and complex economic environment, organizations must be prepared to respond swiftly to crises (natural disasters, pandemics, periods of political instability, etc.) that could hinder the achievement of organizational goals. Recently, the concept of telework has undergone a significant transformation from being a benefit offered by certain companies to becoming a necessary condition for the continued functioning of employers and employees, particularly during the coronavirus pandemic. After the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, a significant portion of professional and educational environments shifted online, leading to an increased reliance on social media across all demographic categories [1]. The pandemic posed a substantial challenge for team communication, especially for those accustomed to intensive or exclusively face-to-face interactions [2]. Furthermore, the conditions and modalities of telework were among the most influential factors in adapting to the pandemic context [3,4].

The introduction of telework by organizations during the coronavirus outbreak highlighted both the benefits of technology in enabling employees to work remotely and the necessity of implementing policies in order for the adaptation of new social and economic realities. The SARS-CoV-2 pandemic triggered shifts in consumer preferences, prioritizing the commerce of goods and services through electronic platforms [5]. To maintain or enhance competitiveness in a dynamic and competitive environment, organizations must demonstrate strong absorptive capacity and effective corporate entrepreneurship to continuously mediate the relationship between opportunities provided by information technology (IT) and organizational performance [6,7].

Due to globalization and other influencing factors, economic shocks have become increasingly frequent in recent years [8]. These changes have underscored the need for flexibility, accelerating production through digitization processes and emphasizing the importance of technological investments. While telework creates several opportunities for organizations—such as reducing dependence on physical locations, enabling cost savings in logistical infrastructure, eliminating geographical barriers, and allowing for the hiring of talent from diverse regions—it also intensifies the requirement for new professional models based on digitization and operational efficiency [9].

From improving software for project monitoring to developing video conferencing platforms and enhancing cybersecurity policies, telework has opened the door to a revolutionary change in how organizations function and operate. Telework also positively impacts sustainability, with many studies highlighting its environmental benefits, such as reduced reliance on cars [10,11,12,13,14]. Telework’s positive impact is evident in decreased road traffic and reduced carbon emissions associated with commuting [9,15].

This study aims to explore the evolution of job demands and job resources from 2021 to 2024, emphasizing the advantages, disadvantages, and challenges associated with implementing telework within organizations. To achieve this, a qualitative analysis was conducted at two critical points in time: during the coronavirus pandemic and after the introduction of chatbots (once employees had adjusted to the “new normal”). The research question guiding the formulation of the three hypotheses was how job demands, job resources, and their related outcomes evolved in 2021 and 2024 during the transition to telework and the subsequent shift to hybrid systems. The three hypotheses examining the situation’s evolution from 2021 to 2024 are as follows:

H1.

The perceived pressure related to job demands, particularly technical requirements and workload, significantly decreased in 2024 compared to 2021.

H2.

The need for assistance expressed through technological support and management practices evolved significantly in 2024 compared to 2021, which reflects more nuanced aspects.

H3.

Respondents’ perceptions of telework in 2024 evolved compared to 2021, converging towards a more unified view with fewer polarized opinions for or against.

2. Literature Review

In a world characterized by constant change, marked by uncertainty and complexity, telework has become an effective solution for adapting to social challenges and the rapid pace of technological advancements. Telework can be defined as performing work in a location outside of the usual workplace, utilizing technology to enable individuals to connect and collaborate with others [16]. The concept of telework originated in 1975 [17] and gained significant attention in the scientific community in the 1990s with the widespread use of personal computing devices, allowing employees to work remotely, essentially delivering their services from anywhere and at any time, eliminating the need to commute to organizational offices [9,18].

Over time, this way of organizing work has evolved from a flexible option to the sole means of conducting business activities. For instance, during the COVID-19 pandemic, as SARS-CoV-2 began to spread globally at the end of 2019 and early 2020, many organizations closed their offices, requiring employees to work from home—a historic shift in the perception and experience of telework [19]. As a result, the transition to telework during the pandemic marked a significant shift in global work practices [20]. During this period, the proportion of teleworkers increased from 11% in 2019 to 39% in April 2020 and 48% by June–July 2020 [10,21].

With the rise in hybrid work environments, organizations are under growing pressure to balance flexibility with providing adequate support for employees [22]. Furthermore, globalization, customer demands, and the wave of digitalization have placed significant competitive pressures on companies as they strive to survive and gain competitive advantages [23,24,25]. The widespread adoption of telework during the coronavirus pandemic created a challenging environment for managers, who had to lead their employees within the constraints of working from home [26,27]. Employees were placed in an entirely new situation where working from home became the sole option, whether full-time or for several days a week [28]. The Eurofound (2020) study suggests that employee productivity is influenced not only by individual skills but also by organizational factors such as communication, work management, and the use of modern technological tools within organizational processes [29,30].

Organizations were also compelled to quickly develop e-commerce websites, create applications and platforms, and transfer documents to storage servers or cloud accounts to ensure easy access to information [31]. E-commerce is not just a technical tool for enhancing traditional business models; it is also a transformative force that reshapes organizational processes, turning them into innovative and efficient environments [32]. Today, the culture of telework and its implementation represents a new challenge for both organizations and employees [33]. As organizations transition from crisis-driven telework to more sustainable hybrid and remote models, understanding how job demands and resources have evolved is essential for shaping long-term workforce strategies [34]. Digital transformation can be characterized as the organizational, operational, and cultural changes that occur through the strategic and gradual integration of digital technologies into all aspects of activity [35,36].

As telework becomes a permanent feature in many industries, there is an urgent need to identify the best practices and lessons learned from the swift transition to remote work [37]. During periods of crisis, the introduction of telework was often seen as easier and even led to certain levels of satisfaction [38,39]. Telework offers a range of advantages, including [40] increased job satisfaction [41,42,43,44,45], positive effects on productivity and better results [44,45,46], higher autonomy in task completion, reduced absenteeism and employee turnover, more efficient time management (due to the elimination of commuting), flexible work schedules, lower costs, and improved work–life balance [45,47,48]. Additionally, remote work [49] boosts employee motivation [50], contributes to workplace happiness [51], and enhances employee retention [52]. Telework not only lessens the perception of professional stress but also acts as a resource to mitigate stress, whether caused by frequent interruptions in a traditional work environment or from demanding professional situations [53]. Furthermore, telework has a positive environmental impact, as the digital transformation of organizations helps reduce greenhouse gas emissions [23].

Telework has also redefined how organizational teams communicate, proving that effective communication is not solely reliant on physical proximity but also on using the right technological tools and channels to support information exchange. Telework has further facilitated access to a well-developed variety of information and communication technologies (ICT), such as the Internet and increasingly powerful devices designed to enhance usability and ease of use [9]. The transition to telework, accelerated by the COVID-19 pandemic, has demonstrated that many activities can be performed effectively and productively outside traditional workplaces, making this model a beneficial and sustainable long-term strategy for organizations.

In general, women adapted more easily to working from home compared to men, older employees were more receptive than younger ones, and experienced teleworkers were more positive and open to change compared to inexperienced ones [54]. Despite its visible advantages, many managers are still against telework [55], citing potential drawbacks. Among the most significant disadvantages highlighted in the literature are [40] social isolation, difficulties adapting to technology and digital infrastructure, conflicts between family and work (due to frequent interruptions by family members), poor time management, inadequate managerial training, exhaustive demands leading to burnout and overwork, and the pressure to adapt to a new work system [44,46,47,48,56]. Moreover, the spaces where employees work remotely may not always be ergonomically safe, affecting their health [3,57,58,59]. Teleworkers are also less exposed to organizational values, norms, and rules, becoming less engaged, less attached, and more independent [53].

Despite these potential negative effects, the OECD considers telework a critical measure during the COVID-19 crisis to support economies and productivity [29,60]. Based on these perspectives, the JD-R model provides a global view of all determinants of job satisfaction [61,62]. The JD-R model explains that the relationship between work environment, affective environment, and behavioral outcomes is influenced by job demands and job resources [63,64]. Job demands refer to the psychological, physical, social, or organizational requirements of the job that require sustained psychological or physical effort that may lead to exhaustion [65,66]. Job resources refer to those physical, social, psychological, or organizational aspects that are necessary in achieving job goals, reducing costs, and stimulating personal growth and development [65,67]. Increased job demands at work can lead to tensions or the deterioration of work relationships creating adverse effects such as burnout or conflict situations, while job resources are often used as motivators for employees generating positive effects [68]. There are no longitudinal qualitative analyses in the existing literature that explore how job demands and job resources evolve in response to disruptive technological and social changes, such as the COVID-19 pandemic or the introduction of AI-based tools like chatbots. While many studies have applied the JD-R model to cross-sectional datasets, few have investigated how individual perceptions and experiences related to telework demands and resources change over time. Noticing this gap in the literature, we initiated our research. Through this study, we addressed this shortcoming by applying the JD-R framework to two distinct moments in time (2021 and 2024). In doing so, we were able to capture the evolution of telework and hybrid work practices and their impact on employee well-being, productivity, and engagement.

Despite the fact that the JD-R model has been adopted in different professional settings, the literature lacks longitudinal qualitative analyses testing how job demands (e.g., digital adaptation, workload, social isolation), job resources (e.g., managerial support, flexibility, digital tools), and outputs (e.g., productivity, well-being, and burnout) change over time under the influence of disruptive change. The majority of existing studies use cross-sectional data and are not able to capture the evolving dynamics of these variables in time as employees and organizations adapt to remote and hybrid work. This paper addresses the gaps by investigating how these three main categories (job resources, job demands, and their outputs) manifest and evolve at two key points in time (2021 and 2024), using qualitative insights from the interviews conducted. This study specifically examines how the perceived intensity of job demands has decreased (H1), how the nature of job resources has changed (H2), and how employee performance has improved through organizational and individual adaptation (H3).

Telework has redefined how work is perceived by both employers, offering employers the ability to keep teams connected regardless of distance, and providing employees the freedom to work from anywhere. The telework strategies implemented during the pandemic were not merely temporary solutions but a preparation for an uncertain and unstable future business environment that requires flexibility and a shift in workplace paradigms [22]. To fully harness the benefits of telework, organizations must continually adapt and make balanced investments in technologies that ensure transparent and clear communication channels, which in turn facilitate the exchange of information among employees.

3. Materials and Methods

This research was based on the JD-R model and the analysis of data obtained through interviews with 24 individuals from Romania conducted at two points in time (2021 and 2024) using NVivo software. The Job Demands–Resources (JD-R) model provides a robust framework for analyzing how work-related demands and resources influence employee outcomes such as well-being, productivity, and engagement [69].

The JD-R model was chosen for its strong foundation in determining how job demands and resources affect organizational efficiency and effectiveness, as well as the well-being, motivation, and engagement of employees. The model’s selection for this research was further justified by its ability to explore the longitudinal evolution of the three main categories it defines—job demands, job resources, and outcomes—within the context of remote work and its transition to hybrid models.

The research adopted a qualitative methodology, which aligns well with the requirements of the JD-R model, allowing for detailed insights into the perceptions and experiences of the interview participants at both time points. Moreover, given the unprecedented nature of the two contexts under analysis, a qualitative approach enabled an in-depth exploration of the phenomenon, despite the challenges often associated with the validity of such research. The concept of validity itself remains controversial, with various debates surrounding its definition [70]. Validity can be assessed both in terms of the accuracy of observations and the validity of research results. Traditionally rooted in the positivist paradigm, validity often relies on objective procedures aimed at generalizable findings [71].

Threats to validity can be mitigated by adhering to several guidelines, including collecting a large volume of detailed information on the analyzed aspects, ensuring respondents have expertise in the topics discussed to avoid inaccuracies, identifying and investigating divergent elements in the dataset, engaging the researcher intensively and over the long term in the subject matter, collecting convergent data from different sources (triangulation), comparing data obtained from various groups, and incorporating quantitative factors where possible [72,73].

This study was based on semi-structured interviews in which respondents had the opportunity to share their perceptions and experiences and met the requirements for qualitative interviews, which are tools used for comprehensive analysis [74]. In practice, some interviews are conducted without pre-prepared questions, allowing respondents to freely express their emotions and experiences [75]. The researcher must not only know how to ask questions but, more importantly, foster an environment of trust and encourage respondents to open up and share valuable insights [76].

NVivo was chosen for its capacity to support users in organizing and analyzing non-numeric and unstructured data. The software enables researchers to classify, sort, and arrange information; examine relationships between data; and integrate analysis with linking, modeling, searching, and restructuring data [77].

Through NVivo, trends can be identified, and data can be analyzed in various ways using its search engine and query functions to create a body of evidence that either supports or challenges the hypotheses that are formulated [78]. The 24 semi-structured interviews conducted in two phases (2021 and 2024) systematically identified key job demands (e.g., workload, technical challenges) and job resources (e.g., flexibility, managerial support) that influence outcomes such as well-being and productivity. Coding these data into parent and child nodes under the JD-R categories facilitated a structured comparison of persistent and emerging themes.

The 10 questions that formed the semi-structured interview guide were distributed across the three JD-R model categories as follows:

Job Demands (factors that require sustained effort and may lead to strain or stress):

What are the key challenges of working in a remote team?

What were the primary challenges you faced as a manager or member of a remote team during the pandemic?

What are the advantages and disadvantages of telework in terms of efficiency?

Job Resources (factors that help achieve work goals, reduce job demands, or foster personal growth):

What would motivate you to work enthusiastically in remote teams in the future?

Identify the main factors that influence communication in remote teams.

What factors could impact the efficiency of communication in remote teams?

What are the advantages and disadvantages of telework in relation to achieving organizational goals?

Outcomes (the results of the interplay between job demands and resources, including performance, well-being, and societal impact):

How important is telework from your perspective?

What is your personal experience with telework in your professional activity?

In your opinion, can telework support society in transitioning towards a green economy?

To prevent bias in the results, several classification criteria for respondents were considered, including gender, age, years of experience within the organization, and the diversity of the industries studied [79].

The first phase of the research involved translating the interviews into English, as they were initially transcribed and verified by the respondents. This translation was necessary because NVivo, even in version 15, does not support Romanian. After uploading the files named according to the research phase and respondent, cases were created, and texts were carefully studied. Based on classification information, cases were categorized, revealing that 15 out of 24 respondents held management positions, 17 had over seven years of organizational experience, 12 had remote work experience prior to the pandemic, and 50% were female. One respondent was under 30 years old, 12 were aged 30–40, 10 were 40–50, and one was over 50. The main industries represented were real estate, automotive, clinical studies, financial services, banking, university, retail, and construction.

These classification criteria ensured a balanced approach and supported further analyses, enabling comparisons across different factors.

In the second phase, parent nodes aligned with the JD-R model—job demands, job resources, and outcomes. These parent nodes were used to code the cases, and child nodes were developed for each category, resulting in four child nodes for job demands, five for job resources, and three for outcomes.

Most respondents expressed a preference for anonymity, prompting a decision to anonymize all responses, even if the initial consent form allowed participants to opt out of anonymity.

4. Results

After completing the coding process, a frequency analysis of the most important terms was conducted to ensure that all significant elements were accurately reflected within the created codes, covering both the 2021 and 2024 datasets.

This analysis covered datasets from both 2021 and 2024. In the 2021 dataset, the 25 most frequently used terms from the 24 interviews included communication, challenges, experience, efficiency, professional organization, responsibility, flexibility, perspectives, management, productivity, disadvantages, interactions, colleagues, understanding, connectivity, environment, advantages, and activities. In contrast, the 2024 dataset revealed that while communication remained a key element, terms such as efficiency, collaboration, professional perspectives, interaction, and flexibility held greater prominence compared to 2021.

Certain terms, including efficiency, challenges, responsibilities, disadvantages, and maintaining collaboration retained similar levels of importance across both datasets. However, new terms such as technology, motivation, and engagement emerge in 2024, reflecting shifts in priorities. Conversely, terms like understanding and connectivity, which were prominent in 2021, are no longer present in the 2024 dataset. These differences are clearly illustrated in Figure 1 below, which presents the two graphs.

Figure 1.

Word frequency 2021 (left) versus 2024 (right) (source: own research—export from NVivo).

Communication was the most significant term in both phases of the research, underscoring its pivotal role in the evolution of remote work practices throughout the studied period. The major challenges and the adaptation of collaboration methods emphasized the critical need for effective communication. Terms such as efficiency, challenges, productivity, and especially flexibility retained their importance in both 2021 and 2024. Structural challenges, as well as those related to responsibility, were emphasized in 2021 through terms like responsibility and environment.

These were classified under the “Job Demands” code, highlighting concerns about increased workloads and the new, complex technical requirements that arose during the transition to remote work. Initial difficulties diminished over time, confirming the validity of Hypothesis H1.

In the 2024 research phase, terms such as collaborative, organizational, and engagement emerged, signaling a shift toward more sophisticated strategies to foster collaboration and involvement. This evolution of job resources provides early evidence supporting Hypothesis H2, which suggests a move toward a flexible, hybrid work system where employees receive emotional support and benefit from advanced collaboration opportunities.

In 2021, terms like disadvantages and responsibilities were predominant, reflecting the challenges and stress associated with transitioning to a new work system. However, by 2024, these terms had lost significance, aligning with Hypothesis H3, which suggests improvements such as reduced burnout risks and enhanced team collaboration. Simultaneously, terms reflecting positive aspects, such as efficiency and flexibility, remained prominent in both periods.

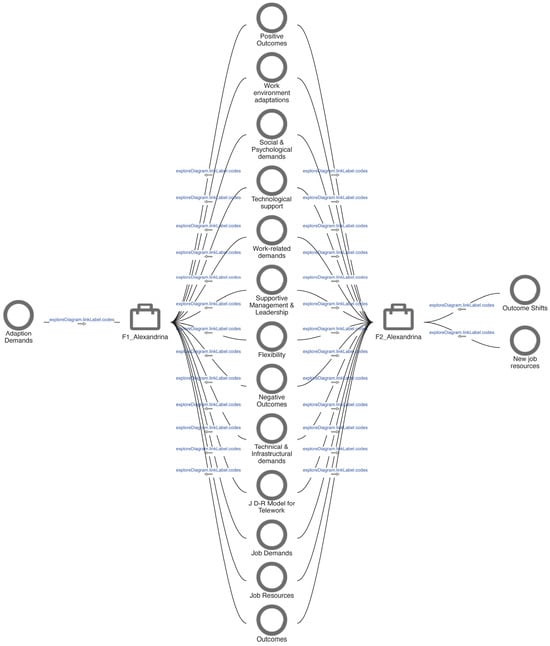

The frequency analysis of terms provided valuable initial evidence supporting the hypotheses and informed the creation of codes for each parent code category, as required by the JD-R model. These codes are illustrated in Figure 2, generated using the “Explore Diagrams” function in NVivo.

Figure 2.

Explore Diagrams of Job Demands, Job Resources, and Outcomes (source: own research—export from NVivo).

For the Job Demands category, four codes were established: “Work-related Demands”, “Social & Psychological Demands”, “Technical & Infrastructural Demands”, and “Adaptation Demands”. The first three codes were created based on the 2021 data, while the “Adaptation Demands” code was added after analyzing the 2024 data.

In 2021, the “Work-related Demands” code included references to increased working hours, blurred boundaries between professional and personal life, challenges related to fulfilling responsibilities, adapting to the new work system, and difficulties in virtual communication for teamwork. The “Technical & Infrastructural Demands” code addressed concerns like unreliable Internet access and outdated technology, as well as the difficulties employees faced when using digital platforms and tools critical for remote work. The “Social & Psychological Demands” code captured the loss of natural, spontaneous interactions with colleagues in face-to-face settings. It also reflected feelings of isolation, reduced motivation, uncertainty about the future, and increased stress levels.

For the Job Resources parent code, the following child codes were created in 2021: “Flexibility”, “Technological Support”, “Supportive Management & Leadership”, and “Work Environment Adaptations”. The “New Job Resources” code was added after analyzing the 2024 data. The “Flexibility” code included aspects related to the benefits of remote work in organizing both professional and personal life, as well as opportunities to adapt work schedules based on individual productivity peaks. The “Technological Support” code captured references to communication and collaboration platforms, digital tools, and equipment provided by companies to facilitate remote work. “Supportive Management & Leadership” included references emphasizing the need for new managerial approaches to support and guide employees remotely, given the lack of direct interaction that characterized traditional work environments. The “Work Environment Adaptations” code encompassed aspects related to the creation of functional home office spaces, supported to varying degrees by employers, allowing employees to concentrate, maintain productivity, and engage in team activities to sustain motivation and involvement.

For the Outcomes parent code, the initial child codes created in 2021 were “Positive Outcomes” and “Negative Outcomes”, later supplemented with the “Outcome Shifts” code in 2024. The “Positive Outcomes” code initially included references to increased efficiency in task execution, attributed to quieter environments and fewer distractions. Another frequently mentioned benefit was the reduced need for commuting, saving time and minimizing stress and fatigue associated with travel. Quiet home environments and the ability to independently schedule work tasks also contributed to an initial boost in productivity for many respondents.

The “Negative Outcomes” code revealed variations based on respondents’ roles within the organization. Managers highlighted reduced team engagement, diminished innovation, and creativity due to limited collaboration. They also pointed to challenges in coordinating and monitoring employee performance, as well as the additional time required to guide, motivate, and support team members facing emotional difficulties or unfamiliarity with remote work tools. Employees, on the other hand, cited frustrations related to delays in receiving peer support, miscommunication, and difficulties establishing boundaries between work responsibilities and personal life.

By 2024, all three parent codes, aligned with the JD-R model, were enriched with new insights. For “Job Demands”, the “Work-related Demands” code now included references to the overwhelming volume of written communication and challenges in prioritizing tasks, as well as delays in feedback that affected decision-making processes. The “Technical & Infrastructural Demands” code reflected an increased reliance on stable Internet and digital tools, along with gaps in team members’ digital skills. In 2024, there was a heightened emphasis on digital proficiency as a critical job requirement and a focus on maintaining innovation and creativity in remote work settings.

Under the “Job Resources” parent code, each child code was updated with new information. For “Flexibility”, hybrid models were increasingly mentioned as a way to balance face-to-face collaboration with the advantages of remote work. “Technological Support” included more advanced tools for informal and structured collaboration, emphasizing reliability and adaptability to diverse needs. Both employees and managers demonstrated a greater sense of ease, and regular team-building activities—both virtual and in-person—were highlighted. The “Work Environment Adaptations” code incorporated regular digital skills training and weekly video meetings to improve communication. New resources emphasized emotional support for individuals, strategies to sustain motivation, and efforts to promote innovation and creativity. Some managers reported organizing informal gatherings at the office to maintain interpersonal connections and satisfy the natural human need for casual communication, ultimately helping to preserve organizational culture and a sense of belonging.

For the parent code Outcomes, it was observed that negative outcomes decreased in intensity as most individuals became accustomed to the new working conditions. Among the positive outcomes, professional autonomy was most frequently mentioned, alongside an increase in efficiency for technical tasks requiring a high level of concentration. New aspects categorized under the “Outcome Shifts” code included hybrid work, the alignment of organizational strategic objectives with the limitations and advantages of remote work, and the maintenance of operational continuity. Additionally, a new concern emerged regarding the potential for job loss due to the replacement of human labor by robots, cobots, or other virtual assistants. This fear is explained by respondents’ awareness of significant technological advancements, particularly in the evolution of artificial intelligence.

Given the importance of resources that organizations must currently provide, a more detailed analysis of these resources was conducted within the context of the JD-R model. While platforms such as Microsoft Teams, Zoom, and other digital tools existed prior to the pandemic, they were not widely known or used by most of the interviewed individuals. During the pandemic, organizations and individuals relied on these solutions to the best of their ability at the time. Over time, their usage has become more sophisticated, incorporating advanced integration and automation features. One element that has gained increasing importance over time is ensuring data security, especially in industries such as banking, financial services, healthcare, and beyond.

Managers’ general attitudes have evolved towards making decisions that adapt to employees’ needs, offering both emotional support and maintaining team morale to enhance motivation and job satisfaction. The working environment provided by the respondents’ organizations is predominantly hybrid, with a strong emphasis on flexibility. Organizations focus on creating a work environment where employees feel comfortable, understood, and supported, ensuring task efficiency and effectiveness. This is achieved through initiatives aimed at mental health support, including relaxation spaces, access to psychological counselors, and other stress management tools.

A key resource offered by most organizations represented in this study is the flexibility to alternate between working from home and the office. This allows employees to adjust their work schedules according to familial needs and their peak productivity periods. This autonomy enables employees to improve their efficiency and effectiveness in completing work tasks. Organizations complement these efforts with training programs focused on developing digital and soft skills, including virtual collaboration, leadership, adaptability, openness to change, and resilience. Standardizing remote and hybrid work procedures has reduced uncertainty and improved efficiency.

At the onset of the pandemic, technological resources and managerial support for remote work were in their infancy, with organizations transitioning to remote work, often overnight, to varying degrees of success. In the current context, these resources have become more sophisticated, encompassing all the aforementioned elements and, in some cases, being integrated into comprehensive well-being programs. This demonstrates the maturation of organizational practices and a deeper understanding of employees’ needs. According to the JD-R model, the evolution of these resources plays a crucial role in mitigating the negative effects of ever-changing job demands, illustrating the progression of remote work and confirming Hypothesis H2.

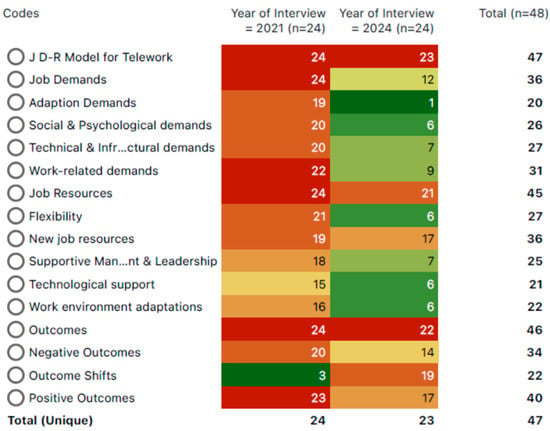

The next NVivo feature utilized was the Crosstab Query of the analyzed cases. The results are presented in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Crosstab Query cases for 2021 versus 2024 (source: own research—export from NVivo).

Here, we observe a decrease in the elements mentioned under the Job Demands category in 2021, attributed to the adaptation and improvement of organizational infrastructure and practices. This significant reduction in the parent code is also reflected in each child code. For instance, adaptation demands have decreased as remote work became a standard practice, or what is now considered the “new normal”. Social and psychological challenges have also declined, indicating that teams found solutions to improve collaboration after learning to work remotely. Similarly, the pressure related to workload was not perceived as significant in 2024 as it was shortly after the pandemic’s onset. This implies that perceived job demands (e.g., long hours, blurred work–life boundaries) have diminished due to organizations and employees adapting to remote working. This confirms Hypothesis H1, which suggests that job demands decrease, in particular technical requirements and workload.

Regarding Job Resources, the number of cases remains approximately at the same level in both analyzed periods, with slight decreases in 2024 for flexibility, management and leadership support, technical support, and work environment adaptation. For the New Job Resources code, the number of cases does not differ significantly between the two periods. This can be explained by the respondents focusing on new aspects that emerged, while resources already mentioned during the first phase of interviews, being part of their daily activities, were no longer highlighted as relevant elements. The new resources primarily pertain to individual well-being, flexibility, and emotional support, as illustrated by the example of well-being programs. This demonstrates Hypothesis H2, showing that job resources evolved from infrastructure and flexibility to emotional support and hybrid work models.

For the Outcomes parent code, the overall number of cases does not vary greatly. However, significant differences exist within the child codes—a notable decrease in Negative Outcomes and an increase in Outcome Shifts, from 3 to 19 references. This indicates a clear transition from a roughly equal number of positive and negative outcomes to predominantly positive outcomes. In conclusion, we can confirm Hypothesis H3, observing that positive outcomes increase as organizations adapt to new conditions and as individuals grow accustomed to remote work.

The JD-R model highlights the relationships between Job Demands, Job Resources, and Outcomes. In this study, the most pressing issue initially affecting individuals, and subsequently the efficiency and effectiveness of the organizations they work for, was “burnout”. For this reason, we created a Word Tree centered on the term “burnout” to explore in greater depth the data related to this phenomenon provided by the respondents. Figure 4 presents this graph, showcasing examples from the processed texts that illustrate the key aspects respondents mentioned in connection with this term.

Figure 4.

Word Tree “Burnout” (source: own research—export from NVivo).

Regarding the term “burnout”, a key aspect was the blurred boundaries between professional activity and personal life in the context of remote work. The flexibility and autonomy gained through remote work gave many individuals the feeling of being constantly on call, leading to extended working hours. One respondent noted, “The lack of clear boundaries between work and personal life leads to longer working hours and, ultimately, burnout”. This idea was also echoed by other respondents, even when the term “burnout” was not explicitly mentioned.

Another aspect raised by respondents referred to the prolonged time spent in front of screens and extended virtual interactions. This resulted in accumulated fatigue, which negatively impacted both the physical and psychological well-being of individuals involved in remote work.

Respondents also highlighted the lack of informal interaction with colleagues, which occurred naturally and spontaneously in an office setting where individuals met face-to-face. The absence of such interactions was seen as a negative factor, influencing task completion by prolonging the time required. In this regard, respondents emphasized the difficulty of receiving immediate support from colleagues for specific issues, something that was easily resolved during in-person interactions.

Additionally, respondents mentioned the need for proactive interventions by management to reduce the risks of burnout. One example is captured in the following statement: “Encouraging structured breaks and clearly defining working hours helps”.

Even in 2024, respondents highlighted that remote work, in some cases, led to delays in decision-making or complicated activities requiring creativity due to the lack of spontaneity in interactions. One respondent succinctly expressed this issue: “For tasks that require immediate collaboration or quick decision-making… the challenges of remote work remain”. These elements identified in the Word Tree “burnout” complemented the Crosstab Query cases, which highlighted burnout as a persistent issue across both phases of the research. In 2021, burnout was closely linked to initial adaptations and technical barriers, while in 2024, it reflected accumulated fatigue generated by long-term remote or hybrid work without clear boundaries and with increased reliance on virtual tools.

As a result of this analysis, several measures were identified to reduce the risks of burnout by developing clear protocols for working hours and the number and duration of breaks to prevent overload. Adding team-building activities was recommended to boost morale and re-establish spontaneous collaboration among team members. Managers require training programs to recognize early signs of burnout within their teams. Given the ongoing changes, it is crucial for organizations to continuously optimize the digital tools used to reduce unnecessary screen time and improve operational workflows to enhance performance parameters.

All 24 respondents were higher-educated individuals from urban environments, with four of them having worked remotely even before the pandemic due to the nature of their job descriptions. In Figure 5, we compare the coding for a respondent employed as an assistant manager who had no prior experience with remote work before the pandemic. This analysis aims to verify whether the general conclusions are also valid on an individual level.

Figure 5.

Code allocation for the assistant manager respondent in 2024 versus 2021 (source: own research—export from NVivo).

For the parent node Job Demands, the respondent emphasized, during the pandemic, aspects such as workload volume, blurred boundaries between professional and personal life, the lack of face-to-face interaction, inadequate digital tools, and unstable Internet connectivity. By 2024, the respondent noted that they had adapted well to remote work, now combining it with sporadic office presence. While the workload remained high, it was much better managed through organizational procedures introduced during this period. Additionally, issues related to technical requirements had significantly diminished due to improved resources provided by the organization.

From the perspective of the parent node Job Resources, during the pandemic research period, the respondent focused heavily on the significant dependence on technological support and the need for management assistance. However, they highlighted flexibility as a key resource that allowed them to better divide their time. By 2024, the respondent stated that technological resources had improved and were now a standard feature. They continued to benefit from the flexibility of their work schedule. Furthermore, their work environment had improved through the configuration of personalized spaces for their home office, enhancing productivity. However, the respondent still expressed a need for emotional and psychological support during periods of isolation and overload.

For the parent node Outcomes, notable evolutions were also observed. Remote work was no longer perceived as a novelty but instead as an opportunity for increased productivity. The risk of burnout had decreased due to the adaptation and enhancement of resources provided by the organization. The respondent mentioned that productivity initially declined during the abrupt transition to remote work; then, it increased as adaptation occurred. However, this was followed by a rise in stress and overload, leading to another decrease in productivity. Currently, the hybrid system and improved resources have once again boosted productivity. The respondent noted that even though no significant changes are currently taking place, technological advancements, including the emergence of AI-powered chatbots, require continuous adaptation to new circumstances. As new Job Demands emerge, the organization continues to adapt Job Resources to ensure positive outcomes in the long term.

5. Discussion

Job Demands, Job Resources, and Outcomes were examined in the context of the transition from pandemic-driven remote work to sustainable hybrid work models, utilizing the theoretical framework of the JD-R (Job Demands–Resources) model. Data collected during the two interview phases were analyzed comparatively, confirming the proposed hypotheses.

Hypothesis H1: “The perceived pressure related to job demands, particularly technical and workload demands, decreased significantly in 2024 compared to 2021”. This hypothesis was confirmed based on respondents’ feedback. Job demands were easier to manage in 2024, with respondents reporting reduced intensity in issues such as extended working hours, unclear boundaries between personal and professional life, and technical difficulties experienced during the pandemic. This positive evolution stems from the improvement in job resources, particularly organizational investments in digital infrastructure and modern technologies, as well as employees’ accumulated experience with this new work system. Organizational support has also focused on job redesign, task adaptation, role-specific procedures, and relaxation techniques [34]. Negative Outcomes show a decrease in feelings of burnout and isolation, indicating better management of job demands.

Hypothesis H2: “The need for support, expressed through technological support and management practices, evolved significantly in 2024 compared to 2021, towards more nuanced aspects”. This hypothesis was confirmed by the shift from tangible, basic resources like technology and equipment to intangible resources, such as empathy, well-being programs, training, and psychological counseling provided by organizations.

Hypothesis H3: “Respondents’ perspectives on remote work evolved in 2024 compared to 2021, converging toward a common viewpoint with fewer entirely pro or contra opinions”. This hypothesis was confirmed. The evolution of outcomes toward predominantly positive results was observed across all comparisons, regardless of the NVivo function used in presenting the results. Both organizations and their members overcame the initial barriers of remote work and learned what, how, and when to offer support and, conversely, what, how, and when to request resources to optimize final outcomes.

6. Conclusions

The results of this research highlight the relevance of the JD-R model in analyzing and deepening the understanding of transitions from traditional work systems to remote work during the pandemic, and to hybrid work in the current period.

This research is valuable for organizations, whether small and in their early stages or more experienced ones, by providing clear directions on key aspects and measures in the context of evolving work models. These directions include continuous investment in technology, complemented by informational and emotional support for employees; ensuring hybrid work environments that offer maximum flexibility without compromising efficiency; implementing strategies to prevent burnout by managing the balance between demands and resources; and, specifically, training management to recognize the early signs of burnout.

The findings of this research enrich the academic literature by highlighting how Job Demands, Job Resources, and Outcomes have evolved from the onset of the pandemic to 2024, addressing the challenges of continuously changing and dynamic contexts. The study offers guiding perspectives for the future organization of work. This research emphasizes that to successfully manage a changing workforce, organizations need to adopt flexible and hybrid models that capitalize on lessons from the pandemic; invest in complex resources that meet both the professional and emotional needs of employees; and constantly monitor the balance between demands and resources to ensure positive outcomes and prevent negative effects. These insights are essential for informing decision-making processes, technological investments, and leadership practices aligned with evolving employee expectations and organizational objectives.

Demands have decreased in intensity as organizations have implemented support measures and employees have adapted to the new reality of remote work. These developments suggest that organizations can better manage employee stress and pressure through strategic planning and investment in infrastructure. The measures most appreciated by employees, as implemented by organizations according to the research findings, included a well-structured and consistent feedback system and digital detox initiatives, as well as emotional and psychological support programs. This study also highlighted that hybrid work models allowing autonomy in choosing both schedule and work environment, alongside investments in user-friendly collaboration platforms—particularly those enabling informal communication and fostering team cohesion—have contributed significantly to positive outcomes. Therefore, an organization aiming for sustainable success must continuously improve telework conditions by institutionalizing virtual team-building activities, offering training programs to enhance digital skills, and establishing clear work hour protocols to help prevent burnout. Early recognition of burnout symptoms and sustained employee motivation are critical. For this reason, all individuals with responsibilities in team coordination—whether permanent or occasional—should develop adaptive leadership skills. In remote work settings especially, work needs to be centered around the individual. This calls for organizational policies that not only support operational efficiency but also promote employee well-being.

The Job Demands–Resources (JD-R) model provided a robust framework for exploring how Job Demands and Job Resources influence employee outcomes such as well-being, productivity, motivation, and engagement [69]. The chosen methodological approach not only validates the applicability of the JD-R model in continuously evolving work environments but also highlights the nuanced interaction between demands, resources, and outcomes as employees and organizations adapt to long-term remote work practices. By linking these qualitative findings to the theoretical foundations of the JD-R model, this study contributes both to practical insights for organizational strategies and to theoretical advancements in understanding the implications of remote work within the JD-R framework.

The shift to remote work during the pandemic marked a significant transformation in global work practices [20]. Organizations adopted work models that ensured the continuity of operations and the achievement of organizational objectives in a crisis context. Over time, these work practices evolved toward more sustainable models, whether remote or hybrid, making it crucial to understand how job demands and resources have shifted for long-term workforce strategies. This research captures the dynamic nature of these changes and offers insights into challenges and opportunities that remain relevant today and in the coming years.

Organizations face challenges related to the flexibility demanded by employees, the support they require, and the ability to maintain high productivity levels to ensure efficiency and effectiveness [22]. Our research highlights critical factors that have influenced and continue to influence individual motivation, satisfaction, and engagement, ultimately driving performance growth or decline. Each organization must consider these factors to develop strategies that address challenges effectively, ensuring a sustainable future in an ever-changing economic and social context.

As more organizations and industries adopt remote or hybrid work models, it becomes increasingly important to understand critical factors, develop best practices, and apply lessons learned during the rapid pandemic-induced transition. Doing so will help build a secure and stable future.

This study also acknowledges several limitations, primarily those inherent in qualitative research. Additionally, all respondents were from urban environments, predominantly aged between 30 and 50 years, and exclusively held higher education degrees. For future research, we aim to replicate this study in collaboration with colleagues and educators from other countries and validate the findings through quantitative analysis methods.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.V. and M.M.; methodology, C.V. and M.M.; software, C.V.; validation, C.V., M.M. and D.C.B.; formal analysis, M.M.; investigation, C.V.; resources, M.M.; data curation, D.C.B.; writing—original draft preparation, C.V. and M.M.; writing—review and editing, M.M., C.V. and D.C.B.; visualization, M.M., C.V. and D.C.B.; supervision, M.M.; project administration, C.V., M.M. and D.C.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

For further information, please contact the authors.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| JD-R model | Job Demands–Resources model |

References

- Govindankutty, S.; Gopalan, S. From Fake Reviews to Fake News: A Novel Pandemic Model of Misinformation in Digital Networks. J. Theor. Appl. Electron. Commer. Res. 2023, 18, 1069–1085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maurer, M.; Bach, N.; Oertel, S. Forced to go virtual. Working-from-home arrangements and their effect on team communication during COVID-19 lockdown. Ger. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2022, 36, 238–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Labrecque, C.; Lecours, A.; Gilbert, M.-H.; Boucher, F. Workers’ Perspectives on the Effects of Telework During the COVID-19 Pandemic on Their Well-being: A Qualitative Study in Canada. Work 2023, 74, 785–798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carillo, K.; Cachat-Rosset, G.; Marsan, J.; Saba, T.; Klarsfeld, A. Adjusting to epidemic-induced telework: Empirical insights from teleworkers in France. Eur. J. Inf. 2021, 30, 69–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gogonea, R.; Moraru, L.; Bodislav, D.; Paunescu, L.; Vlasceanu, C. Similarities and Disparities of e-Commerce in the European Union in the Post-Pandemic Period. J. Theor. Appl. Electron. Commer. Res. 2024, 19, 340–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Türkes, M. Driving Success: Unveiling the Synergy of E-Marketing, Sustainability, and Technology Orientation in Online SME. J. Theor. Appl. Electron. Commer. Res. 2024, 19, 1411–1441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rehman, N.; Razaq, S.; Farooq, A.; Zohaib, N.; Nazri, M. Information technology and firm performance: Mediation role of absorptive capacity and corporate entrepreneurship in manufacturing SMEs. Technol. Anal. Strateg. Manag. 2020, 32, 1049–1065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Park, K.-C.; Marjerison, R. Usefulness of Online Reviews of Sensory Experiences: Pre- vs. Post-Pandemic. J. Theor. Appl. Electron. Commer. Res. 2024, 19, 1471–1492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stamos, G.; Kotsopoulos, D. Applying IS-Enabled Telework during COVID-19 Lockdown Periods and Beyond: Insights from Employees in a Greek Banking Institution. Adm. Sci. 2024, 14, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krasilnikova, N.; Levin-Keitel, M. Telework as a Game-Changer for Sustainability? Transitions in Work, Workplace and Socio-Spatial Arrangements. Sustainability 2022, 14, 6765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguiléra, A.; Pigalle, E. The Future and Sustainability of Carpooling Practices. An Identification of Research Challenges. Sustainability 2021, 13, 11824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beck, M.; Hensher, D.; Wei, E. Slowly coming out of COVID-19 restrictions in Australia: Implications for working from home and commuting trips by car and public transport. J. Transp. Geogr. 2020, 80, 102846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elldér, E. Telework and daily travel: New evidence from Sweden. J. Transp. Geogr. 2020, 86, 102777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Keefe, P.; Caulfield, B.; Brazil, W.; White, P. The impacts of telecommuting in Dublin. Res. Transp. Econ. 2016, 57, 13–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruth, S.; Imran, C. Telework: A productivity paradox? IEEE Internet Comput. 2008, 12, 87–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gajendran, R.S.; Harrison, D.A. The good, the bad, and the unknown about telecommuting: Meta-analysis of psychological mediators and individual consequences. J. Appl. Psychol. 2007, 92, 1524–1541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nilles, J.M. Telecommunications and Organizational Decentralization. IEEE Trans. Commun. 1975, 23, 1142–1147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Martino, V.; Wirth, L. Telework: A new way of working and living. Int. Labour Rev. 1990, 129, 529–554. [Google Scholar]

- Smite, D.; Tkalich, A.; Moe, N.; Papatheocharous, E.; Klotins, E.; Buvik, M. Changes in perceived productivity of software engineers during COVID-19 pandemic: The voice of evidence. J. Syst. Softw. 2022, 186, 111197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillips, S. Working through the pandemic: Accelerating the transition to remote working. Bus. Inf. Rev. 2020, 37, 129–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López Soler, J.; Christidis, P.; Vassallo, J. Teleworking and Online Shopping: Socio-Economic Factors Affecting Their Impact on Transport Demand. Sustainability 2021, 13, 7211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shirmohammadi, M.; Chan Au, W.; Beigi, M. Remote work and work-life balance: Lessons learned from the COVID-19 pandemic and suggestions for HRD practitioners. Hum. Resour. Dev. Int. 2022, 25, 163–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capusneanu, S.; Mates, D.; Tűrkes, M.; Barbu, C.-M.; Staras, A.-I.; Topor, D.; Fűlöp, M. The Impact of Force Factors on the Benefits of Digital Transformation in Romania. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 2365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westerman, G.; Calméjane, C.; Bonnet, D.; Ferraris, P.; McAfee, A. Digital transformation: A roadmap for billion-dolllar organization. MIT Sloan Manag. MIT Cent. Digit. Bus. Capgemini Consult. 2011, 1, 1–68. [Google Scholar]

- Bharadwaj, A. A resource-based perspective on information technology capability and firm performance: An empirical investigation. MIS Q. 2000, 24, 169–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nordhall, O.; Kaur, R.; Törnblom, L.; Knez, I. Female managers’ organizational organizational leadership during telework: Experiences of job demands, control and support. Front. Psychol. 2024, 15, 1335749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plotnikof, M.; Bramming, P.; Branicki, L.; Pullen, A.; Christiansen, L.H.; Henley, K.; van Amsterdam, N. Catching a glimpse: Corona-life and its micro-politics in academia. Gend. Work Organ. 2020, 27, 804–826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thulin, E.V.; Brundin, L. Telework after confinement: Interrogating the spatiotemporalities of home-based work life. J. Transp. Geogr. 2023, 113, 103740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivasciuc, I.; Epuran, G.; Vuta, D.; Tescasiu, B. Telework Implications on Work-Life Balance, Productivity, and Health of Different Generations of Romanian Employees. Sustainability 2022, 14, 16108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eurofound. Living, Working and COVID-19|Publications Office of the European Union, Luxembourg 2020. Available online: https://www.eurofound.europa.eu/en/publications/2020/living-working-and-covid-19 (accessed on 2 December 2024).

- Pirosca, G.; Serban-Oprescu, G.; Badea, L.; Stanef-Puica, M.-R.; Valdebenito, C. Digitalization and Labor Market—A Perspective within the Framework of Pandemic Crisis. J. Theor. Appl. Electron. Commer. Res. 2021, 16, 2843–2857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsoud, A.; Harasis, A. The Impact of COVID-19 Pandemic on Student’s E-Learning Experience in Jordan. J. Theor. Appl. Electron. Commer. Res. 2021, 16, 1404–1414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turkeș, M.; Stăncioiu, A.; Băltescu, C. During the COVID-19 Pandemic—An Approach From the Perspective of Romanian Enterprises. Amfiteatru Econ. 2021, 23, 700–717. [Google Scholar]

- Andersone, N.; Nardelli, G.; Ipsen, C.; Edwards, K. Exploring Managerial Job Demands and Resources in Transition to DistanceManagement: A Qualitative Danish Case Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 1–29. [Google Scholar]

- Rupeika-Apoga, R.; Petrovska, K.; Bule, L. The Effect of Digital Orientation and Digital Capability on Digital Transformation of SMEs during the COVID-19 Pandemic. J. Theor. Appl. Electron. Commer. Res. 2022, 17, 669–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Priyono, A.; Moin, A.; Putri, V. Identifying digital transformation paths in the business model of SMEs during the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Open Innov. Technol. Mark. Complex. 2020, 6, 104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacks, T. Research on Remote Work in the Era of COVID-19. J. Glob. Inf. Technol. Manag. 2021, 24, 93–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maillot, A.-S.; Meyer, T.; Prunier-Poulmaire, S.; Vayre, E. A Qualitative and Longitudinal Study on the Impact of Study on the Impact of Telework in Times of COVID-19. Sustainability 2022, 14, 8731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ono, H.; Mori, T. COVID-19 and telework: An international comparison. J. Quant. Descr. Digit. Media 2021, 1, 1–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enes, Y.; Vieira, M.B.; Coelho Junior, F.A.; Pereira, D.; Zanon, É.R. Home-Office During COVID-19 Pandemic in Brazil: Perceived Influences on Performance and Competency Management. Qual. Rep. 2023, 28, 1718–1740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diab-Bahman, R.; Al-Enzi, A. The impact of COVID-19 pandemic on conventional work settings. Int. J. Sociol. Soc. Policy 2020, 40, 909–927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bae, K.B.; Kim, D. The impact of decoupling of telework on job satisfaction in US federal agencies: Does gender matter? Am. Rev. Public Adm. 2016, 46, 356–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ronda, L.; Ollo López, A.; Goni-Legaz, S. Family-friendly practices, high-performance work practices and work–family balance: How do job satisfaction and working hours affect this relationship? Manag. Res. 2016, 14, 2–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fonner, K.L.; Roloff, M.E. Why teleworkers are more satisfied with their jobs than are office-based workers: When less contact is beneficial. J. Appl. Commun. Res. 2010, 38, 336–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, R.E. Teleworking: An assessment of the benefits and challenges. Eur. Bus. Rev. 2004, 16, 344–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker, L. The COVID-19 office in transition: Cost, efficiency and the social responsibility business case. Account. Audit. Account. J. 2020, 33, 1943–1967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakrosiené, A.; Buciuniené, I.; Gostautaite, B. Working from home: Characteristics and outcomes of telework. Int. J. Manpow. 2019, 1, 87–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suh, A.; Lee, J. Understanding teleworkers’ technostress and its influence on job satisfaction. Internet Res. 2017, 27, 140–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kortsch, T.; Rehwaldt, R.; Schwake, M.; Licari, C. Does Remote Work Make People Happy? Effects of Flexibilization of Work Location and Working Hours on Happiness at Work and Affective Commitment in the German Banking Sector. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 9117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deci, E.; Ryan, R. The “what” and “why” of goal pursuits: Human needs and the self-determination of behavior. Psychol. Inq. 2000, 11, 227–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rehwaldt, R. Die Glückliche Organisation. Chancen und Hürden für Positive Psychologie im Unternehmen (Research); Springer Gabler: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Onken-Menke, G.; Nüesch, S.; Kröll, C. Are you attracted? Do you remain? Meta-analytic evidence on flexible work practices. Bus. Res. 2018, 11, 239–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vayre, É.; Morin-Messabel, C.; Cros, F.; Maillot, A.-S.; Odin, N. Benefits and Risks of Teleworking from Home: The Teleworkers’Point of View. Information 2022, 13, 545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hiselius, L.; Arnfalk, P. When the impossible becomes possible: COVID-19’s impact on work and travel patterns in Swedish public agencies. Eur. Transp. Res. Rev. 2021, 13, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- George, G. Manager Perceptions on the Efficacy of Telecommuting for Technology Professional. Ph.D. Thesis, Walden University, Minneapolis, MN, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Lembrechts, L.; Zanoni, P.; Verbruggen, M. The impact of team characteristics on the supervisor’s attitude towards telework: A mixed-method study. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2018, 29, 3118–3146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ipsen, C.; van Veldhoven, M.K.; Hansen, J. Six key advantages and disadvantages of working from home in Europe during COVID-19. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 1826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bubric, K.; Hedge, A. Differential patterns of laptop use and associated musculoskeletal discomfort in male and female college students. Work 2016, 55, 663–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrington, S.; Walker, B. The effects of ergonomics training on the knowledge, attitudes, and practices of teleworkers. J. Saf. Res. 2004, 35, 13–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. Productivity Gains from Teleworking in the Post COVID-19 era: How Can Public Policies Make It Happen. 2020. Available online: https://www.oecd.org/en/publications/2020/07/productivity-gains-from-teleworking-in-the-post-covid-19-era-how-can-public-policies-make-it-happen_0aad8ddd.html (accessed on 5 January 2025).

- Gastearena-Balda, L.; Ollo-Lopez, A.; Larraza-Kintana, M. Are public employees more satisfied than private ones? The mediating role of job demands and job resources. Manag. Res. J. Iberoam. Acad. Manag. 2021, 19, 231–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, A.B.; Hakanen, J.J.; Demerouti, E.; Xanthopoulou, D. Job resources boost work engagement, particularly when job demands are high. J. Educ. Psychol. 2007, 99, 274–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Junça Silva, A.; Violante, C.; Brito, S. The role of personal and job resources for telework’s affective and behavioral outcomes. Kybernetes 2024, 53, 3754–3773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demerouti, E.; Bakker, A. The job demands–resources model: Challenges for future research. SA J. Ind. Psychol. 2011, 37, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sardeshmukh, S.; Sharma, D.; Golden, T. Impact of telework on exhaustion and job engagement: A job demands and job resources model. New Technol. Work. Employ. 2012, 27, 193–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaufeli, W.; Bakker, A. Job Demands, Job Resources, and Their Relationship with Burnout and Engagement: A Multi-Sample Study. J. Organ. Behav. 2004, 25, 293–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demerouti, E.; Bakker, A.B.; Nachreiner, F.; Schaufeli, W.B. The job demands-resources model of burnout. J. Appl. Psychol. 2001, 86, 499–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, M.; Li, S.; Liu, H. The impact mechanism of telework on job performance: A cross-level moderation model of digital leadership. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 12520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, A.B.; de Vries, J.D. Job Demands–Resources theory and self-regulation: New explanations and remedies for job burnout. Anxiety Stress Coping 2020, 34, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winter, G. A comparative discussion of the notion of validity in qualitative and quantitative research. Qual. Rep. 2000, 4, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popa, M. Noțiuni de cercetare calitativă. In Metodologia Cercetării; APIO: Iași, Romania, 2016; pp. 1–25. [Google Scholar]

- Creswell, J.W.; Miller, D.L. Determining validity in qualitative inquiry. Theory Into Pract. 2000, 39, 124–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, R.K. Qualitative Research from Start to Finish; The Guilford Press: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Krahn, G.L.; Putnam, M. Qualitative Methods in Psychological Research. In Handbook of Research Methods in Clinical Psychology; Roberts, M.C., Ilardi, S.S., Eds.; Blackwell Publishing Ltd: Oxford, UK, 2005; pp. 177–195. [Google Scholar]

- Clinchy, B.M. An epistemological approach to the teaching of narrative research Up close and personal: The teaching and learning of narrative research. Am. Psychol. Assoc. 2003, 29–48. [Google Scholar]

- Chase, S.E. Learning to listen: Narrative principles in a qualitative research methods course Up close and personal: The teaching and learning of narrative research. Am. Psychol. Assoc. 2003, 79–99. [Google Scholar]

- Allsop, D.; Chelladurai, J.; Kimball, E.; Marks, L.; Hendricks, J. Qualitative Methods with Nvivo Software: A Practical Guide for Analyzing Qualitative Data. Psych 2022, 4, 142–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saunders, B.; Sim, J.; Kingstone, T.; Baker, S.; Waterfield, J.; Bartlam, B.; Jinks, C. Saturation in qualitative research: Exploring its conceptualization and operationalization. Qual. Quant. 2017, 52, 1893–1907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thurairajah, K. “The person behind the research”: Reflexivity and the qualitative research process. In The Craft of Qualitative Research: A Handbook; Kleinknect, S., van den Scott, L., Sanders, C., Eds.; Canadian Scholar: Toronto, ON, Canada; Vancuver, BC, Canada, 2018; pp. 10–16. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).