Implementing Successful Public–Private IT Outsourcing Relationships: Relational View to Fostering Public Value

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. ITO in the Public Sector

2.2. Relational View of Interorganizational Collaborations

2.3. Importance of Knowledge Interfaces in Public-Private ITO

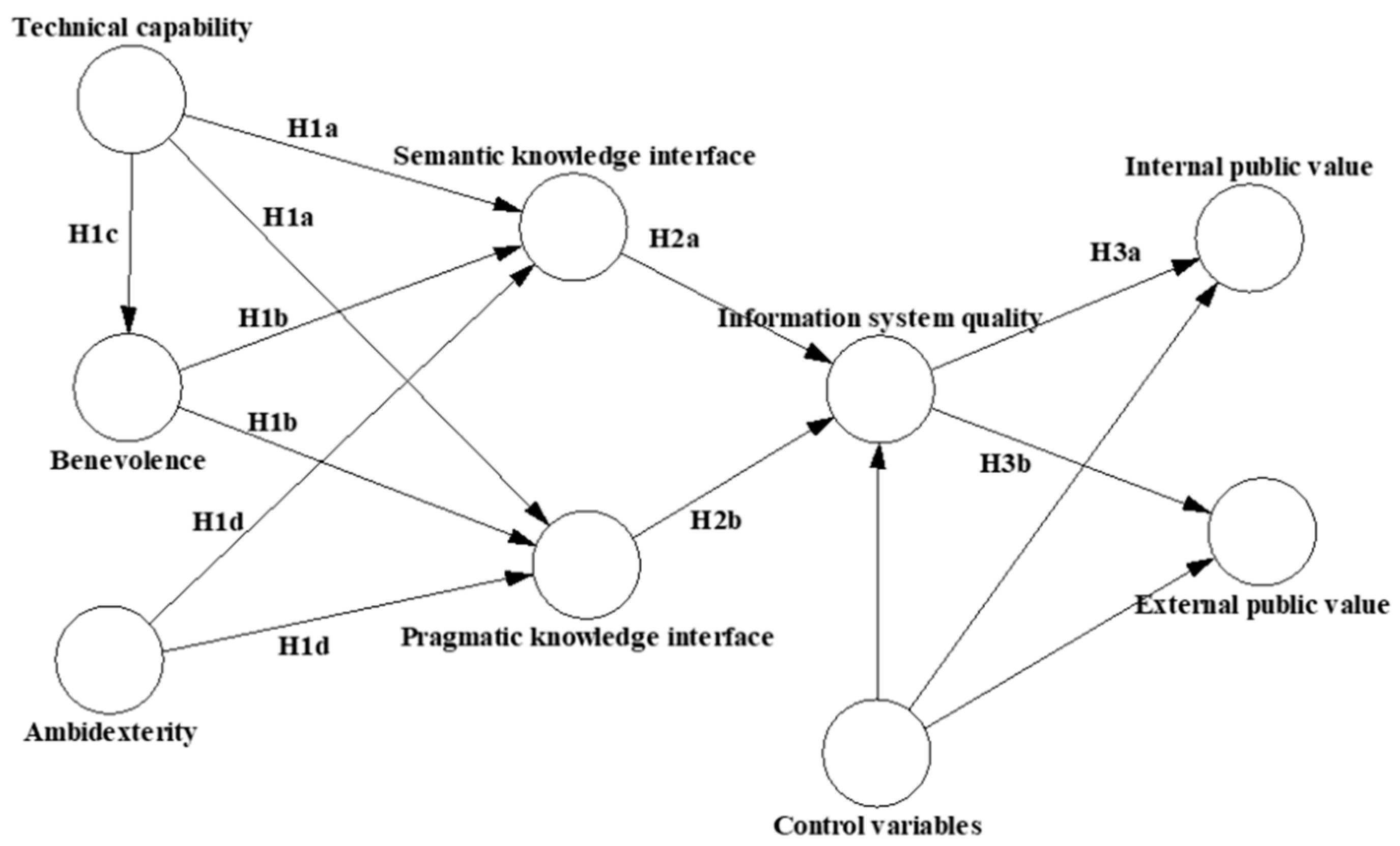

3. Theoretical Framework, Research Model, and Hypotheses

3.1. Relation Between Technical Capability and the Quality of Knowledge Interfaces

3.2. Relation Between Benevolence and the Quality of Knowledge Interfaces

3.3. Relation Between Ambidexterity and the Quality of Knowledge Interfaces

3.4. Relation Between the Quality of Knowledge Interfaces and the Quality of Information Systems

3.5. Information System Quality to Public Value

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Sample

4.2. Measurement

4.3. Data Analysis Method

5. Results

6. Discussion

7. Conclusions

- Building trusting relationships requires attention to the technical competency and benevolence of ITO partners. Public managers involved in the outsourcing process should include an evaluation of the potential for service providers to become trusted partners in a long-term relationship as a criterion in their selection. Beyond the selection process, cultivating trust will continue to be a success factor [85].

- Public managers should redefine their role, keeping strong operational interfaces with the providers’ systems, supported by well-written relational contracts. To do so, there must be some degree of preparation from service providers and a strong capacity of absorption from clients. However, public sector organizations must prepare themselves to redefine their activities as orchestrators of interorganizational relationships.

- Building and maintaining strong operational interfaces involves considering how trust and knowledge interfaces can be developed and nurtured. In this way, besides strategies to build an effective and trusted relationship, public organizations should not abandon the maintenance of associated knowledge and skills related to the project, actively investing in acquiring understanding of technical tools and solutions.

- As our model suggests, relational contracts should include a renewed sense of ambidexterity between formal and informal channels to be able to negotiate changes and adjustments in the contract in an effective manner and to increase chances of success. As projects evolve, understanding of the goals and requirements also evolve. Therefore, it becomes necessary to continuously adjust project components to better respond to evolving requirements.

- In addition, it appears that sharing documentation and methods provides only a precondition for effective alignment between service provider and government agency, given the distinction between the pragmatic and semantic dimensions of knowledge interfaces. Clear procedures and responsibilities, coordination, and arbitration of disagreements are important as well, given that those elements facilitate effective conflict resolution and adjustment in the contractual relationship at the pragmatic level.

- In the particular context of Mexico and other developing countries, understanding the difficulties of sustaining relationships over time should encourage public managers to promote contracts with lengths not limited to the period of current administration and electoral deadlines, as is still too often the case.

- Finally, proper attention should be given to the internal and external dimensions of public value in orientating collaborative efforts with private service providers, who may lack sufficient cultural awareness of their clients’ necessities in that perspective.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Cordella, A.; Willcocks, L. Outsourcing, bureaucracy and public value: Reappraising the notion of the “contract state”. Gov. Inf. Q. 2010, 27, 82–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gantman, S. IT outsourcing in the public sector: A literature analysis. J. Glob. Inf. Technol. Manag. 2011, 14, 48–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joha, A.; Janssen, M. Public-private partnerships, outsourcing or shared service centres? Motives and intents for selecting sourcing configurations. Transform. Gov.-People 2010, 4, 232–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karaba, F.; Roehrich, J.K.; Conway, S.; Turner, J. Information sharing in public-private relationships: The role of boundary objects in contracts. Public Manag. Rev. 2023, 25, 2166–2190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boudreau, C.; Bernier, L. The implementation of integrated electronic service delivery in Quebec: The conditions of collaboration and lessons. Int. Rev. Admin. Sci. 2017, 83, 602–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Favoreu, C.; Carassus, D.; Maurel, C. Strategic management in the public sector: A rational, political or collaborative approach? Int. Rev. Admin. Sci. 2016, 82, 435–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pittaway, J.J.; Montazemi, A.R. Know-how to lead digital transformation: The case of local governments. Gov. Inf. Q. 2020, 37, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryson, J.M.; Crosby, B.C.; Bloomberg, L. Public Value Governance: Moving Beyond Traditional Public Administration and the New Public Management. Public Adm. Rev. 2014, 74, 445–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vangen, S.; Huxham, C. The Tangled Web: Unraveling the Principle of Common Goals in Collaborations. J. Public Adm. Res. Theory 2012, 22, 731–760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nurdin, N.; Stockdale, R.; Scheepers, H. Understanding organizational barriers influencing local electronic government adoption and implementation: The electronic government implementation framework. J. Theor. Appl. Electron. Commer. Res. 2011, 6, 13–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Kim, J. Grounded theory analysis of e-government initiatives: Exploring perceptions of government authorities. Gov. Inf. Q. 2007, 24, 135–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swar, B.; Moon, J.; Oh, J.; Rhee, C. Determinants of relationship quality for IS/IT outsourcing success in public sector. Inform. Syst. Front. 2012, 14, 457–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, T.M.; Maxwell, T.A. Information-sharing in public organizations: A literature review of interpersonal, intra-organizational and inter-organizational success factors. Gov. Inf. Q. 2011, 28, 164–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luna-Reyes, L.F.; Gil-Garcia, J.R.; Cruz, C.B. Collaborative digital government in Mexico: Some lessons from federal Web-based interorganizational information integration initiatives. Gov. Inf. Q. 2007, 24, 808–826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, H.; Schotanus, F.; Bakker, E.; Harland, C. Collaborative procurement: A relational view of buyer–buyer relationships. Public Adm. Rev. 2013, 73, 588–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pang, M.S.; Lee, G.; DeLone, W.H. IT resources, organizational capabilities, and value creation in public-sector organizations: A public-value management perspective. J. Inf. Technol. 2014, 29, 187–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlile, P. A pragmatic view of knowledge and boundaries: Boundary objects in new product development. Organ. Sci. 2002, 13, 442–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlile, P.R. Transferring, translating, and transforming: An integrative framework for managing knowledge across boundaries. Organ. Sci. 2004, 15, 555–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fountain, J.E. Building the Virtual State: Information Technology and Institutional Change; Brookings Institution Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Orlikowski, W. Using technology and constituting structures: A practice lens for studying technology in organizations. Organ. Sci. 2000, 11, 404–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huber, T.L.; Winkler, M.A.E.; Dibbern, J.; Brown, C.V. The use of prototypes to bridge knowledge boundaries in agile software development. Inf. Syst. J. 2020, 30, 270–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dyer, J.H.; Singh, H.; Hesterly, W.S. The relational view revisited: A dynamic perspective on value creation and value capture. Strat. Manag. J. 2018, 39, 3140–3162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaheer, A.; Venkatraman, N. Relational governance as an interorganizational strategy: An empirical test of the role of trust in economic exchange. Strat. Manag. J. 1995, 16, 373–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duhamel, F.; Gutiérrez-Martínez, I.; Picazo-Vela, S.; Luna-Reyes, L. IT outsourcing in the public sector: A conceptual model. Transform. Gov.-People 2014, 8, 8–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duhamel, F.; Gutiérrez-Martínez, I.; Picazo-Vela, S.; Luna-Reyes, L. Determinants of collaborative interfaces in public-private IT outsourcing relationships. Transform. Gov.-People 2018, 12, 61–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eckerd, A.; Eckerd, S. Institutional constraints, managerial choices, and conflicts in public sector supply chains. Int. Public Manag. J. 2017, 20, 624–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osborne, S.P. The new public governance? Public Manag. Rev. 2006, 8, 377–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osborne, S.P. Public management research over the decades: What are we writing about? Public Manag. Rev. 2017, 19, 109–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ansell, C.; Gash, A. Collaborative governance in theory and practice. J. Public Adm. Res. Theory. 2008, 18, 543–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sørensen, E.; Torfing, J. Metagoverning collaborative innovation in governance networks. Am. Rev. Public Adm. 2017, 47, 826–839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agranoff, R. Inside collaborative networks: Ten lessons for public managers. Public Adm. Rev. 2006, 66, 56–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryson, J.M.; Crosby, B.C.; Stone, M.M. Designing and implementing cross-sector collaborations: Needed and challenging. Public Adm. Rev. 2015, 75, 647–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williamson, O. Comparative economic organization: The analysis of discrete structural alternatives. Adm. Sci. Q. 1991, 36, 269–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weeks, M.R.; Feeny, D. Outsourcing: From cost management to innovation and business value. Calif. Manag. Rev. 2008, 50, 127–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aben, T.A.; van der Valk, W.; Roehrich, J.K.; Selviaridis, K. Managing information asymmetry in public–private relationships undergoing a digital transformation: The role of contractual and relational governance. Int. J. Oper. Prod. Manag. 2021, 41, 1145–1191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeLone, W.H.; McLean, E.R. Information systems success: The Quest for the dependent variable. Inf. Syst. Res. 1992, 3, 60–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeLone, W.H.; McLean, E.R. The DeLone and McLean Model of information systems success: A ten-year update. J. Manag. Inf. Syst. 2003, 19, 9–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rondan-Cataluña, F.J.; Arenas-Gaitán, J.; Ramírez-Correa, P.E. A comparison of the different versions of popular technology acceptance models: A non-linear perspective. Kybernetes 2015, 44, 788–805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buyannemekh, B.; Picazo-Vela, S.; Luna, D.E.; Luna-Reyes, L.F. Understanding Value of Digital Service Delivery by Governments in Mexico. Gov. Inf. Q. 2024, 41, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gil-Garcia, J.R.; Dawes, S.S.; Pardo, T.A. Digital government and public management research: Finding the crossroads. Public Manag. Rev. 2018, 20, 633–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wallmeier, F.; Helmig, B.; Feeney, M.K. Knowledge construction in public administration: A discourse analysis of public value. Public Adm. Rev. 2019, 79, 488–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryson, J.M.; Sancino, A.; Benington, J.; Sørensen, E. Towards a multi-actor theory of public value co-creation. Public Manag. Rev. 2017, 19, 640–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cook, M.; Harrison, T.M.; Zhang, J.; Puron-Cid, G.; Gil-Garcia, J.R. Using public value thinking for government IT planning and decision making: A case study. Inf. Pol. Int. J. Gov. Democr. Inf. Age 2015, 20, 183–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nabatchi, T. Putting the “Public” back in public values research: Designing participation to identify and respond to values. Public Adm. Rev. 2012, 72, 699–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandoval-Almazán, R.; Luna-Reyes, L.F.; Luna-Reyes, D.E.; Gil-Garcia, J.R.; Puron-Cid, G.; Picazo-Vela, S. Developing a digital government strategy for public value creation. In Building Digital Government Strategies; Sandoval-Almazán, R., Luna-Reyes, L.F., Luna-Reyes, D.E., Gil-Garcia, J.R., Puron-Cid, G., Picazo-Vela, S., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland; New York, NY, USA, 2017; Volume 16, pp. 7–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benington, J.; Moore, M.H. Public value in complex and changing times. In Public Value; Benington, J., Moore, M.H., Eds.; Macmillan Education: London, UK, 2011; pp. 1–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, M.H. Creating Public Value: Strategic Management in Government; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Picazo-Vela, S.; Gutiérrez-Martínez, I.; Duhamel, F.; Luna, D.E.; Luna-Reyes, L.F. Value of inter-organizational collaboration in digital government projects. Public Manag. Rev. 2018, 20, 691–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertot, J.C.; Jaeger, P.T.; Grimes, J.M. Using ICTs to create a culture of transparency: E-government and social media as openness and anti-corruption tools for societies. Gov. Inf. Q. 2010, 27, 264–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrison, T.M.; Guerrero, S.; Burke, G.B.; Cook, M.; Cresswell, A.; Helbig, N.; Hrdinova, J.; Pardo, T. Open government and e-government: Democratic challenges from a public value perspective. Inf. Pol. Int. J. Gov. Democr. Inf. Age 2012, 17, 83–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dawes, S.S. The evolution and continuing challenges of E-Governance. Public Adm. Rev. 2008, 68, S86–S102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cordella, A.; Willcocks, L. Government policy, public value and IT outsourcing: The strategic case of ASPIRE. J. Strat. Inf. Syst. 2012, 21, 295–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jørgensen, T.B.; Bozeman, B. Public values: An inventory. Admin. Soc. 2007, 39, 354–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Picazo-Vela, S.; Luna, D.E.; Gil-Garcia, J.R.; Luna-Reyes, L.F. Creating public value through inter-organizational collaboration and information technologies. Int. J. Electron. Gov. Res. 2022, 18, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duhamel, F.; Gutiérrez-Martínez, I.; Picazo-Vela, S.; Luna-Reyes, L.F. Strategic alignment, process improvements and public value in public-private IT outsourcing in Mexico. Int. J. Public Sect. Manag. 2021, 34, 489–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gantman, S.; Fedorowicz, J. Determinants and success factors of IT outsourcing in the public sector. Commun. Assoc. Inf. Syst. 2020, 47, 248–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johansson, T.; Siverbo, S. Governing cooperation hazards of outsourced municipal low contractibility transactions: An exploratory configuration approach. Manag. Account. Res. 2011, 22, 292–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monteduro, F.; Allegrini, V. How outsourcing affects the e-disclosure of performance information by local governments. Gov. Inf. Q. 2020, 37, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roehrich, J.K.; Lewis, M.A.; George, G. Are public–private partnerships a healthy option? A systematic literature review. Soc. Sci. Med. 2014, 113, 110–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goles, T.; Chin, W.W. Information systems outsourcing relationship factors: Detailed conceptualization and initial evidence. ACM SIGMIS Database Database Adv. Inf. Sys. 2005, 36, 47–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moon, J.; Choe, Y.C.; Chung, M.; Jung, G.H.; Swar, B. IT outsourcing success in the public sector lessons from e-government practices in Korea. Inf. Dev. 2014, 32, 142–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomson, A.M.; Perry, J.L. Collaboration processes: Inside the black box. Public Adm. Rev. 2006, 66, 20–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopes, A.V.; Farias, J.S. How can governance support collaborative innovation in the public sector? A systematic review of the literature. Int. Rev. Admin. Sci. 2022, 88, 114–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agger, A.; Sørensen, E. Managing collaborative innovation in public bureaucracies. Plan. Theor. 2018, 17, 53–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, L.; Mohan, K.; Ramesh, B.; Sarkar, S. Evolution of governance: Achieving ambidexterity in IT outsourcing. J. Manag. Inf. Syst. 2013, 30, 115–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torfing, J. Collaborative innovation in the public sector: The argument. Public Manag. Rev. 2019, 21, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiwana, A. Systems development ambidexterity: Explaining the complementary and substitutive roles of formal and informal controls. J. Manag. Inf. Syst. 2010, 27, 87–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monazam Tabrizi, N. Relational dimensions, motivation and knowledge-sharing in healthcare: A perspective from relational models theory. Int. Rev. Admin. Sci. 2023, 89, 221–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eriksson, E.; Andersson, T.; Hellström, A.; Gadolin, C.; Lifvergren, S. Collaborative public management: Coordinated value propositions among public service organizations. Public Manag. Rev. 2020, 22, 791–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neumann, O.; Matt, C.; Hitz-Gamper, B.S.; Schmidthuber, L.; Stürmer, M. Joining forces for public value creation? Exploring collaborative innovation in smart city initiatives. Gov. Inf. Q. 2019, 36, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levina, N.; Vaast, E. The emergence of boundary spanning competence in practice: Implications for implementation and use of information systems. MIS Q. 2005, 29, 335–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ansell, C.; Gash, A. Collaborative platforms as a governance strategy. J. Public Adm. Res. Theory 2018, 28, 16–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goo, J.; Huang, C.D.; Hart, P. A path to successful IT outsourcing: Interaction between service-level agreements and commitment. Decision Sci. 2008, 39, 469–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cordella, A.; Iannacci, F. Information systems in the public sector: The e-Government enactment framework. J. Strat. Inf. Syst. 2010, 19, 52–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Black, L.J.; Carlile, P.R.; Repenning, N.P. A dynamic theory of expertise and occupational boundaries in new technology implementation: Building on Barley’s study of CT scanning. Adm. Sci. Q. 2004, 49, 572–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blakçori, F.; Psychogios, A. Sensing from the middle: Middle managers’ sensemaking of change process in public organizations. Int. Stud. Manag. Organ. 2021, 51, 328–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carey, G.; Jacobs, K.; Malbon, E.; Buick, F.; Li, A.; Williams, P. Boundary Spanners. In Crossing Boundaries in Public Policy and Management: Tackling the Critical Challenges; Craven, L., Dickinson, H., Carey, G., Eds.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2018; pp. 121–134. [Google Scholar]

- Oswick, C.; Robertson, M. Boundary Objects Reconsidered: From Bridges and Anchors to Barricades and Mazes. J. Change Manag. 2009, 9, 179–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sullivan, H.; Williams, P.; Marchington, M.; Knight, L. Collaborative futures: Discursive realignments in austere times. Public Money Manag. 2013, 33, 123–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feldman, M.S.; Khademian, A.M. The Role of the public manager in inclusion: Creating Communities of Participation. Governance 2007, 20, 305–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uppström, E.; Lönn, C.-M. Explaining value co-creation and co-destruction in e-government using boundary object theory. Gov. Inf. Q. 2017, 34, 406–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gil-Garcia, J.R.; Pardo, T.A.; Sutherland, M.K. Information sharing in the regulatory context: Revisiting the concepts of cross-boundary information sharing. In Proceedings of the 9th International Conference on Theory and Practice of Electronic Governance, Montevideo, Uruguay, 1–3 March 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayer, R.C.; Davis, J.H.; Schoorman, F.D. An integrative model of organizational trust. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1995, 20, 709–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.Y.; Im, K.S.; Kim, J.S. The role of IT human capability in the knowledge transfer process in IT outsourcing context. Inform. Manag. 2011, 48, 53–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaheer, A.; McEvily, B.; Perrone, V. Does trust matter? Exploring the effects of interorganizational and interpersonal trust on performance. Organ. Sci. 1998, 9, 141–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goo, J.; Nam, K. Contract as a source of trust-commitment in successfully IT Outsourcing relationship: An empirical study. In Proceedings of the 40th Hawaii International Conference on Systems Sciences, Waikoloa, HI, USA, 3–6 January 2007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luna-Reyes, L.F.; Black, L.J.; Cresswell, A.M.; Pardo, T. Knowledge-sharing and Trust in Collaborative Requirements Analysis. Syst. Dyn. Rev. 2008, 24, 265–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bassellier, G.; Benbasat, I. Business competence of information technology professionals: Conceptual development and influence on IT-business partnerships. MIS Q. 2004, 28, 673–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, C.; Chau, P.Y. Relationship, contract and IT outsourcing success: Evidence from two descriptive case studies. Decis. Support Syst. 2012, 53, 859–869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, H.S.; Lee, J.N.; Seo, Y.W. Analyzing the impact of a firm’s capability on outsourcing success: A process perspective. Inf. Manag. 2008, 45, 31–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caglio, A.; Ditillo, A. A review and discussion of management control in inter-firm relationships: Achievements and future directions. Account. Org. Soc. 2008, 33, 865–898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Z.; Lumineau, F. Revisiting the interplay between contractual and relational governance: A qualitative and meta-analytic investigation. J. Oper. Manag. 2015, 33, 15–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Im, G.; Rai, A. Knowledge sharing ambidexterity in long-term interorganizational relationships. Manag. Sci. 2008, 54, 1281–1296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngah, E.; Tjemkes, B.; Dekker, H. Relational dynamics in information technology outsourcing: An integrative review and future research directions. Int. J. Manag. Rev. 2024, 26, 54–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caccamo, M.; Pittino, D.; Tell, F. Boundary objects, knowledge integration, and innovation management: A systematic review of the literature. Technovation 2023, 122, 102645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.-N.; Huynh, M.Q.; Hirschheim, R. An integrative model of trust in IT outsourcing: Examining a bilateral perspective. Inf. Syst. Front. 2008, 10, 145–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luna-Reyes, L.F.; Gil-García, J.R.; Sandoval Almazán, R. Avances y Retos del Gobierno Digital en México; Instituto de Administración Pública del Estado de México y Universidad Autónoma del Estado de México: Toluca, Mexico, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Baruch, Y.; Holtom, B.C. Survey response rate levels and trends in organizational research. Hum. Relat. 2008, 61, 1139–1160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clement, J.; Manjon, M.; Crutzen, N. Factors for collaboration amongst smart city stakeholders: A local government perspective. Gov. Inf. Q. 2022, 39, 101746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cook, C.; Heath, F.; Thompson, R.L. A meta-analysis of response rates in web- or internet based surveys. Educ. Psychol. Meas. 2000, 60, 821–836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Lee, J.Y.; Podsakoff, N.P. Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J. Appl. Psychol. 2003, 88, 879–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hair Jr, J.F.; Matthews, L.M.; Matthews, R.L.; Sarstedt, M. PLS-SEM or CB-SEM: Updated guidelines on which method to use. Int. J. Multivar. Data Anal. 2017, 1, 107–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarstedt, M.; Ringle, C.M.; Hair, J.F. Treating unobserved heterogeneity in PLS-SEM: A multi-method approach. In Partial Least Squares Path Modeling; Latan, H., Noonan, R., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland; New York, NY, USA, 2017; pp. 197–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M.; Straub, D.W. Editor’s comments: A critical look at the use of PLS-SEM in “MIS Quarterly”. MIS Q. 2012, 36, iii. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mateos-Aparicio, G. Partial least squares (PLS) methods: Origins, evolution, and application to social sciences. Commun. Stat. Theory Methods 2011, 40, 2305–2317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodhue, D.L.; Lewis, W.; Thompson, R. Does PLS have advantages for small sample size or non-normal data? MIS Q. 2012, 36, 981–1001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. PLS-SEM: Indeed a silver bullet. J. Mark. Theory Pract. 2011, 19, 139–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gil-Garcia, J.R. Using partial least squares in digital government research. In Handbook of Research on Public Information Technology; Garson, G.D., Khosrow-Pour, M., Eds.; IGI Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2008; pp. 239–253. [Google Scholar]

- Kock, N.; Hadaya, P. Minimum sample size estimation in PLS-SEM: The inverse square root and gamma-exponential methods. Inform. Syst. J. 2018, 28, 227–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aragão, J.P.S.; Fontana, M.E. Outsourcing strategies in public services under budgetary constraints: Analysing perceptions of public managers. Public Organ. Rev. 2022, 22, 61–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luna-Reyes, L.F. Collaboration, Trust and Knowledge Sharing in Information-Technology-Intensive Projects in the Public Sector. Ph.D. Thesis, State University of New York at Albany, New York, NY, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

| IT Project | Number | % |

|---|---|---|

| Software development | 29 | 47% |

| Data center operations | 20 | 32% |

| Digitalization of documents and files | 9 | 15% |

| Cloud services | 4 | 6% |

| Total | 62 | 100% |

| Category | Item |

|---|---|

| Benevolence | |

| BENE 1 | The service provider considers the welfare of my organization, as well as its own, when making important decisions in this project. |

| BENE 2 | The service provider considers the interests of my organization and their organization when problems arise. |

| BENE 3 | The service provider makes beneficial decisions to us under any circumstances. |

| Technical capability | |

| TECH 1 | My service provider is very capable of performing their job in this project. |

| TECH 2 | My service provider is known to be successful at the things they do. |

| TECH 3 | My service provider has specific technological capabilities that can increase our performance. |

| Ambidexterity | When coordinating activities with the service provider, we use formal channels (official reports and briefings, formal planned meetings, logs and other official communications through standard procedures, etc. …) and informal channels (face-to-face conversations, phone conversations, and email or text messages through unplanned interactions or meetings) … |

| AMB 1 | … to exchange knowledge. |

| AMB 2 | … to resolve conflicts. |

| AMB 3 | … to adapt or change processes. |

| Semantic interface | |

| SEM 1 | We and our service provider share manuals, models, and methodologies with each other. |

| SEM 2 | We and our service provider share know-how from work experience with each other. |

| SEM 3 | We and our service provider share each other’s know-where and know-whom if decisions need to be taken. |

| Pragmatic interface | |

| PRAGMA 1 | My service provider and I have different understandings of our project goals. |

| PRAGMA 2 | Often, during the collaboration with the service provider, I initially think I understand them, but afterwards, this turns out not to be correct. |

| PRAGMA 3 | I have a different perception of solutions to problems than my service provider. |

| PRAGMA 4 | It is hard to come to a joint solution with my service provider. |

| Information system quality | |

| INF 1 | Info systems produced through the collaboration are easy to use. |

| INF 2 | Info systems produced through the collaboration are useful. |

| INF 3 | Info systems produced through the collaboration can be customized to our needs. |

| Internal public value | |

| PV 1 | During the course of the collaboration, we have been able to reduce the cost of operations in our organization in this project. |

| PV 2 | During the course of the collaboration, we have been able to access top-class, state-of-the-art IT capabilities in this project. |

| External public value | |

| PV 3 | During the course of the collaboration, we have been able to create a more transparent government thanks to this project. |

| PV 4 | During the course of the collaboration, we have been able to increase systems’ timeliness for the citizen thanks to this project. |

| PV 5 | During the course of the collaboration, we have been able to increase systems’ user friendliness for the citizen thanks to this project. |

| Project complexity | |

| COMPLEX_1 | The project entailed new technical requirements for our organization. |

| COMPLEX_2 | The project included new technologies. |

| COMPLEX_3 | The project involved the coordination of multiple units. |

| Experience | |

| EXP_1 | Number of years of tenure in the present position. |

| Variable | Cronbach’s Alpha | Composite Reliability | AVE |

|---|---|---|---|

| BENE | 0.894 | 0.897 | 0.826 |

| TECH | 0.869 | 0.87 | 0.792 |

| AMBI | 0.881 | 0.881 | 0.808 |

| SEM | 0.801 | 0.807 | 0.717 |

| PRAGMA | 0.917 | 0.918 | 0.801 |

| ISQ | 0.907 | 0.907 | 0.843 |

| IPV | 0.841 | 0.841 | 0.863 |

| EPV | 0.954 | 0.954 | 0.915 |

| COMPLEX | 0/827 | 0/897 | 0.744 |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Technical capability | ||||||||

| Benevolence | 0.411 | |||||||

| Ambidexterity | 0.243 | 0.149 | ||||||

| Pragmatic knwl. interface | 0.585 | 0.399 | 0.292 | |||||

| Semantic knwl. interface | 0.478 | 0.517 | 0.483 | 0.339 | ||||

| Information system qual. | 0.695 | 0.537 | 0.209 | 0.567 | 0.595 | |||

| Internal public value | 0.878 | 0.501 | 0.367 | 0.615 | 0.452 | 0.756 | ||

| External public value | 0.783 | 0.538 | 0.210 | 0.452 | 0.394 | 0.703 | 0.944 |

| Dependent Construct | Independent Construct | Path Coefficients and p Values |

|---|---|---|

| Benevolence R2 (adj) = 0.118 | Technical capability | 0.364 * |

| Semantic interface quality R2 (adj) = 0.275 | Benevolence | 0.306 * |

| Technical capability | 0.230 | |

| Pragmatic interface quality R2 (adj) = 0.289 | Benevolence | 0.184 |

| Technical capability | 0.421 *** | |

| Information system quality R2 (adj) = 0.571 | Semantic interface quality | 0.396 *** |

| Pragmatic interface quality | 0.341 ** | |

| Internal public value R2 (adj) = 0.395 | Information system quality | 0.583 *** |

| External public value | Information system quality | 0.585 *** |

| R2 (adj) = 0.377 | ||

| Complexity | Information system quality | 0.399 *** |

| Internal public value | −0.003 | |

| External public value | −0.001 | |

| Experience | Information system quality | 0.241 |

| Internal public value | −0.112 | |

| External public value | 0.035 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Duhamel, F.; Gutiérrez-Martínez, I.; Luna-Reyes, L.F. Implementing Successful Public–Private IT Outsourcing Relationships: Relational View to Fostering Public Value. J. Theor. Appl. Electron. Commer. Res. 2025, 20, 42. https://doi.org/10.3390/jtaer20010042

Duhamel F, Gutiérrez-Martínez I, Luna-Reyes LF. Implementing Successful Public–Private IT Outsourcing Relationships: Relational View to Fostering Public Value. Journal of Theoretical and Applied Electronic Commerce Research. 2025; 20(1):42. https://doi.org/10.3390/jtaer20010042

Chicago/Turabian StyleDuhamel, Francois, Isis Gutiérrez-Martínez, and Luis Felipe Luna-Reyes. 2025. "Implementing Successful Public–Private IT Outsourcing Relationships: Relational View to Fostering Public Value" Journal of Theoretical and Applied Electronic Commerce Research 20, no. 1: 42. https://doi.org/10.3390/jtaer20010042

APA StyleDuhamel, F., Gutiérrez-Martínez, I., & Luna-Reyes, L. F. (2025). Implementing Successful Public–Private IT Outsourcing Relationships: Relational View to Fostering Public Value. Journal of Theoretical and Applied Electronic Commerce Research, 20(1), 42. https://doi.org/10.3390/jtaer20010042