Abstract

The increase in digital disruptions and changing preferences of different stakeholders has led to digital adoption in all hierarchies of business ecosystem. This study focused on the identification of the determinants of digitalization in unorganized small, localized retail outlets (Kirana stores) of an emerging economy. A theoretical model was constructed with certain modifications based on technology adoption models such as Technology Acceptance Model (TAM) and Unified Theory of Acceptance and Use of Technology 2 (UTAUT2) to study the impact on business performance in general and as an effect of pandemic. A survey of 285 Unorganized Localized Retail Outlets Stores from different regions of India was used to validate this theoretical model, and structural equation modeling was then further employed. The findings underscore that cost, compatibility, perceived ease of use, and perceived usefulness significantly affect the intention to digitalize. By addressing the post-pandemic impact of digitalization within an unorganized sector in an emerging economy, this study adds to the scant literature that exists in this context.

1. Introduction

Globally, the fast growth of digital technologies and loops of digital disruptions are setting up a new normal and new competitive dynamics across all kinds of business activities, such as finance and accounting, operations, strategy, and organization design [1,2,3,4,5]. For example, according to Statista Digital Market Outlook, during 2017–2021, global revenues in the e-commerce industry increased by 70% and total revenues touched around $3.8 trillion. Still, small grocery stores remained relatively immune to digital disruptions in the pre-pandemic times [6]. However, the recent powerful trends, such as changing consumer attitudes as well as accelerated technology adoption in the post-pandemic world, has made disruptions in the small grocery business a global phenomenon.

Digitalization, defined as the “use of digital technologies to change a business model and provide new revenue and value-producing opportunities”, is a hot issue in pandemic and post-pandemic information systems research [7,8]. Since digitalization alters how businesses, people, and groups function, communicate, and generate values using technology, economies face a series of challenges such as inadequate infrastructure support, lack of market intelligence, and meagre technological capabilities [9,10,11].

Irrespective of how digitalization has been adopted in earlier times, one event that has forced the new normal and imparted enormous impact but remained under-explored is the COVID-19 pandemic. While the socio-economic impact of the pandemic is enormous across all regions, emerging markets face the challenges more profoundly [2]. For example, Loayza [12] argued that uncertainties and vulnerabilities in emerging markets are relatively more due to resource constraints and institutional limitations. Moreover, in the case of small unorganized businesses, the pandemic posed problems which were even more drastic [13]. Evidently, the pace of digitalization has accelerated after the pandemic, but small businesses in the unorganized sector have faced more challenges than the organized sector in the digitalization journey. The challenges, opportunities, and business benefits of digitalization presently facing the unorganized sector, especially in the pandemic and post-pandemic setting, is an important case to study.

In the unorganized sector, one of prominent businesses that has contributed immensely, in economic terms, is the unorganized retail, grocery, and neighborhood store segment [14]. The unorganized grocery business worldwide has experienced digitalization at different paces and the COVID-19 pandemic has made the impact even more variegated [15,16]. On the one hand, Malaysia was one of the early adopters of digital technologies, owing to state initiatives [17]. On the other hand, the United States struggled in digitalization of small retail stores [16]. Even before the pandemic, several provision stores in Switzerland brought in new schemes or expanded their click-and-collect services, allowing consumers to place online orders and then pick their items up from the store [18]. However, such trends were not common in an emerging market like India due to the lack of digital infrastructure and consumers’ preferences among others. In India, the adoption of digital technologies was accelerated after two major policy interventions, namely demonetization and indirect tax reforms (known as the Goods and Services Tax) in the years 2016 and 2017, respectively [19]. Moreover, recent research on consumers’ digitalization readiness during the pandemic in Bangladesh showed that the measures taken by the state had significantly affected small retail sectors’ knowledge, attitude, and perception about digital transformation [20].

In extant literature, there are many studies that have reported on barriers, enablers, and the determining factors impacting digitalization and the digital transformation of different segments of the organized sector businesses [21,22]. Also, there is the presence of post-COVID-19 pandemic literature on digital adoptions in several organized sector businesses, large retail segments [23,24], and SME sector businesses [25], respectively. Though these studies adopted a plethora of technology adoption frameworks for establishing the relationships between the drivers of digital technology adoption, they have overlooked the unique challenges and motivations of the small, unorganized neighborhood retailer segment, such as their financial constraints and affordability, limited technology expertise and training, hyper-localized customer dynamics, and infrastructure issues. The scarcity of research exploring digitalization in the unorganized retail sector, and particularly in the context of emerging markets, presently persists [14,26]. This study fills these gaps by using an integrated model based on the Technology Acceptance Model (TAM) and Unified Theory of Acceptance and Use of Technology 2 (UTAUT2). Thus, in the following three aspects, the present study is novel. First, it focuses on unorganized retail in India. Second, the Indian retail market is unique due to the geographical and cultural differences that result in differences in consumer behaviors and economic conditions. Lastly, it examines the determinants at the micro level for detailed insights. So, the value addition of the present study to the existing literature on the digital economy is as follows. It classifies specific barriers and enablers for digitalization within the diverse unorganized neighborhood retail stores in the context of India. The insights from the present study have several policy implications in the context of digital transformation within the retail sector in a developing market context, and they have laid the foundation for future studies in other developing nations.

With these motivations in mind, we investigate the factors that influence digitalization in unorganized small businesses in an emerging market context. The rest of the article is structured as follows: Section 2 provides a brief review of existing literature. Section 3 explains the theory development for the proposed model. Section 4 and Section 5 present the methodology and empirical analysis. Finally, Section 6 and Section 7 provides a comprehensive discussion of the research’s conclusions and the ramifications are then provided.

2. Literature Review

The review of the literature for this study can be divided into two sections. The first section will examine the literature pertaining to the unorganized small businesses (grocery stores in this case), with a special emphasis on the Indian context. The second part will curate the digital technologies and their impact on the performance of these businesses, and how the post-pandemic world changes the discourse.

In the context of emerging economies, small businesses including the Kirana stores in the Indian context posit a significant position as these are the neighborhood suppliers of goods, and they generate livelihoods at a large scale [27]. Kirana stores in India are small neighborhood shops offering essential groceries with personalized service and flexible credit options. These are generally a kind of unorganized localized retail outlet that sells everything from basic provisions to branded merchandise. Unlike Western grocery stores, they have a limited product range, focus on local communities, and often extend delivery services and credit to regular customers. This model emphasizes personal relationships and adaptability to meet the diverse needs of the community. These stores also act as important linkages between urban and rural regions [28]. These grocery stores could be part of an organized or unorganized set-up; however, the latter remains the dominant part in emerging economies. The literature also suggests that such unorganized neighborhood stores involve people from low-income groups, i.e., bottom of the pyramid, therefore the retail sector has become an important part of economic development [29]. For example, India is one of the top five biggest retail markets with a 10% contribution to GDP, 8% total employment, and has remained largely unorganized [30].

The Kirana stores tailor their items according to the ethnicity and geography of their trade location [31]. India’s retail sector employs nearly one out of every twelve individuals and contributes to almost one-tenth of the national income [30]. In terms of numbers, India’s retail sector is world’s fifth largest destination with an estimated $2 trillion valuation by 2032 and a 9% projected growth rate from 2019 to 2030. With the third highest number of e-retail shoppers, India’s e-retail sector following the pandemic is expected to grow at a phenomenal 25% per annum. Combined with other changes such as the vast popularity of UPI (Unified Payments Interface), transition to D2C (Direct-to-Consumer) business model, new-age logistic solutions, and changing consumer behavior, India’s retail sector is an interesting case study in the digital transformation discourse.

Prior to the pandemic, digitalization was not a top priority for unorganized sector retail stores globally [6]. The changing consumer behavior and overall ecosystem after the pandemic has pushed the unorganized retail sector to adopt digitalization [32]. For example, during the pandemic, when there was a surge in demand for home delivery, many grocery stores across the world started using messaging platforms such as WhatsApp or a virtual queue was brought into effect to reduce the volume of clients that may be simultaneously served in the stores, as well as provide delivery slots to vulnerable or elderly customers. However, in most cases, the digital technologies which were adopted by the grocery stores included mostly open source and less expensive digital platforms such as unified payments interface (UPI) and social media platforms. The recent data show that the value of UPI (e.g., Google Pay, PhonePe, and Paytm) transactions in India has increased from 1700 crores to almost 13 Lakh crores from 2017 to 2022 [33]. In addition to this, technologies like QR codes and RFID, along with the presence of hand scanners in grocery stores, play an important role in the adoption of their use by consumers [26,34]. Also, policies such as GST in India have incentivized businesses to employ digital tools such as mini-ERP or a tax filing system. Surely, this has motivated the retail sector to move towards a formal set-up but one question that calls for further attention is as follows: How many unorganized neighborhood retail stores (Kirana stores) have adopted digitalization in an emerging market context such as in India, especially in the context of COVID-19 and within the post-COVID-19 landscape?

3. Proposed Model and Development of Hypothesis

The proposed research model of this study is based on technology adoption models such as the Technology Acceptance Model (TAM) and the Unified Theory of Acceptance and Use of Technology 2 (UTAUT2). According to TAM, Perceived Usefulness (PEU) and Perceived Ease of Use (PEOU) have direct impacts on behavioral intentions and include causal chains of beliefs and attitudes towards the adoption of technologies [35]. According to UTAUT2, “Cost”, which represents the monetary value of using the technology, determines the intentions as well as the performance of adopting technologies [36]. Together, these two models cover the psychological, financial, and technological issues related to behavioral intentions towards digitalization and digital transformations [37,38].

In the present context of unorganized small businesses in India, some other important variables could also be theorized as important predictors for digitalization and digital transformation. Compatibility is an important predictor which refers to how much the employees associated with such businesses are either familiar with or motivated to adopt the technology based upon their belief that it might improve their performance [39]. This belief could come either from the prior experiences and practices or because of an exogenous factor such as competitive pressure [35,40]. Moreover, in an emerging economy context, cost becomes one of the key factors as the market is largely driven by implications of affordability and price differentials. If the costs of technology adoption are relatively higher than that of conventional practices, it becomes a serious impediment [41]. Therefore, the costs of technology adoption are an important factor that could either motivate or discourage a business towards digitalization and digital transformation. Finally, economies have experienced several structural and functional changes due to the COVID-19 pandemic and therefore it can be argued that digitalization has become a crucial aspect for all kinds of businesses in recent times [42].

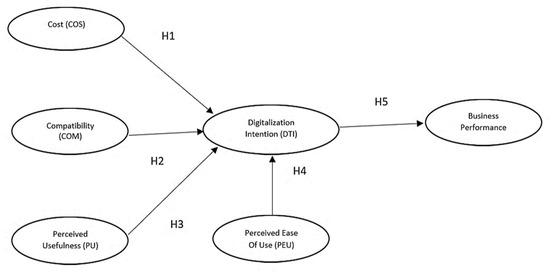

The proposed research model considers that the perceived usefulness, perceived ease of use, cost, and compatibility directly impact (positively or negatively) the digitalization intentions of businesses.

3.1. Costs

Cost in this case refers to the comparison between the benefits acquired while adopting such technologies versus the sacrifices made in the process. The literature indicates there is a significant impact of the costs incurred during the adoption of a technology [43]. In the context of the emerging economies, costs play an even more important role. This is further driven by all kinds of inertia that conventional business models impart such as the initial set-up cost or cost of the necessary digital infrastructure for continuing those technologies. For example, the disruption in the Indian telecom sector caused by Reliance Jio presented a case of how low-cost availability of digital services could help in the adoption of technologies in an emerging economy [44].

Also, emerging economies face the issue of low working capital that sometimes makes them sensitive towards any such costs. Furthermore, there are cultural factors in the Indian contexts as well that push for such inertia. Digital technologies, however, are cost-effective and help to cause low operational costs in the long run [45]. Hence, it is likely that a small retailer in an unorganized segment would use digital technologies if there were reasonable overall costs associated with the digitalization journey. Based on these inputs, the following hypothesis can be formulated:

H1.

Cost (COS) has a negative impact on the small unorganized retailers’ intention to adopt digitalization.

3.2. Compatibility

Compatibility consists of two main components as follows: (a) fit of digital technologies with the business in consideration; and (b) present-day relevance of the innovation and digital technologies and the extent of value creation for the business [46,47]. The essential pillars of compatibility for digitalization are skills, flexibility, and awareness. It provides decision-making options as well as the crucial components to adapt to the change. Organizations with current and updated IT equipment have a competitive edge because they can restructure business strategies and rework existing goods and offers into digitally enhanced products. In the small retailers’ context, compatibility comes out to be an essential ingredient because of cost-effectiveness in the long run and better efficiency. In terms of relevance, the adoption of digital technologies is important for better customer service and helps small businesses to equip themselves for scaling up marketing outreach among others. For example, the effective adoption of digital technologies could lead to improved performance when organizations are able to leverage IT and complement their core capabilities [48]. Deriving from the above discussion, the following hypothesis is also proposed:

H2.

Compatibility (COM) has a positive impact on the small unorganized retailers’ intention to adopt digitalization.

3.3. Perceived Usefulness

In the TAM framework, the belief of PEU appears as one of the most important constructs [49,50]. PEU could be considered as a measure to which the user (here, a small retailer) posits the belief that the use of digital technologies would help to ensure better business performance. If the small retailers could perceive that use of technologies would be critical for their business performance, that retailer would be sure to accept the technology. In this case, digitalization could be used to create new or modify existing business models, processes, and products that could enhance performance [51]. Several studies have shown that PEU has important links with the intentions of small retailers to use the digital technologies [52]. Even in the case of an emerging market like India, a similar positive relation does exist [36]. The belief of PEU comprises factors such as performance, effectiveness, risk, and trust. For example, Adhikary et al. [26] confirmed, in their study of unorganized retailers, that adoption of digital technologies improves the financial performance of firms in an emerging market context. Thus, it could be said that that PEU has a substantial effect on digitalization. With this discussion, the following hypothesis can then be proposed:

H3.

Perceived usefulness (PEU) has a positive impact on the small unorganized retailers’ intention to adopt digitalization.

3.4. Perceived Ease of Use

PEOU is one of the fundamental constructs of TAM and it is a measure of how confident a person feels in utilizing technology [50]. It is among the motivating factors that influence whether an individual engages with digital technology [53]. PEOU contains a measure of simplicity and self-efficacy that shows an individual’s perception of a technology’s simplicity of use [54]. The PEOU and PU are two key constructs of technology models that positively affect technology or policy adoption in small industries [55]. Even though PEOU indirectly affects the adoption of new technology through intention, its influence is sometimes greater than that of PU [56]. This concept aids in the formulation of the following hypothesis:

H4.

Perceived Ease of Use (PEOU) has a positive impact on the small unorganized retailers’ intention to adopt digitalization.

3.5. Behavioral Intention for Digitalization

Behavioral intention for digitalization (DTI) is closely linked to the mindful tactics for the transformation of various business activities using smartphones, computers, and other instruments [36]. In the absence of any negative factor that is external to adoption of digitalization, such as the cost of the necessary infrastructure, the behavioral intention to adopt digitalization results in realizing the expected outcomes [57]. This could be attributed to the fact that digital technologies help to eliminate the barriers of time and space, and businesses can make better use of their current assets. Further, successful integration that is associated with the corporate strategy will reduce challenges inside a company, resulting in greater system, procedure, and resource productivity [58]. Earlier studies have also put up ample evidence that the adoption of digital technologies helps in improving the performance of the business, indicating a positive relationship [3].

H5.

Behavioral intentions for digitalization have a positive impact on the performance of businesses, insofar as small unorganized neighborhood retail stores in India are concerned.

Based on all these discussions, Figure 1 represents the proposed research model.

Figure 1.

Proposed research model.

4. Research Methodology

The current study is specific to unorganized localized retail outlets stores (also referred to as Kirana stores) in India. For the validation of the proposed model and for the hypotheses testing, we employed survey-based empirical analysis. Structural and analytical modeling techniques were employed to test the proposed model for digital transformation intention. We used two research tools as follows: (1) Confirmatory factor analysis; and (2) Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) to assess the validity and reliability requirements.

4.1. Research Instrument Development

The questionnaire’s development drew upon established constructs from the TAM and UTAUT theoretical frameworks. As recommended by the originators of TAM and UTAUT, modifications and refinements to these frameworks are imperative to suit various applications and contexts [37]. Therefore, in our study centered on the digitalization of Kirana stores, we slightly adjusted the TAM model constructs to better correspond with our objectives. Within this study, the Behavioral Intention for Digitalization (DTI) construct was formulated by adapting the Behavioral Intention of Technology construct from the TAM model. The Behavioral Intention construct within the TAM model encapsulates the inclination toward technology adoption, and its extension to the context of digitalization adoption allows for pertinent adaptations. In the context of our study, the behavioral intention for digital or digitalization adoption can manifest through several avenues, including recognizing the significance of digitalization, committing to the adoption/utilization of digital tools, technologies, and platforms, devising a digitalization strategy, collaborating with value chain partners/stakeholders to leverage digitalization benefits, and actively seeking support from governmental agencies for digitalization initiatives. Accordingly, the items associated with these dimensions have been integrated into the construct in alignment with the study’s focus.

Questionnaires with a five-point Likert scale, contextualized for unorganized small businesses, was used. The full list of questionnaire items used in Pilot Study 1 is presented in Supplementary Table S1. The questionnaire was pretested twice with 30 Kirana store owners at a particular location. In the first pilot testing, a few items were dropped, and a few items were revised to clarify unclear wording. The reliability analysis of Pilot Study 1 is tabulated in Supplementary Table S2. In Supplementary Table S2, it can be observed that the Cronbach’s alpha values for all the constructs, except the DTI, were in the acceptable range. Based on the feedback and values obtained in the Phase 1 pilot study, a few of the items of the constructs were dropped and some statements were rephrased to improve the instrument understandability and reliability. In the second pilot testing, the improved questionnaire was pilot tested with another 30 Kirana stores. The reliability analysis of Pilot Study 1 is tabulated in Supplementary Table S3. From Supplementary Table S3, it can be inferred that the Cronbach’s alpha values for all the constructs were greater than 0.90, which indicates that the reliability for these constructs is very good and hence acceptable. Once the reliability and validity results were obtained under the satisfaction ranges in second pilot study, the questionnaire was then adopted for the full-scale study. The items/measurements of each are coded using a five-point Likert scale, where “5” implied Strongly Agree (SA) and “1” implied Strongly Disagree (SD). All the measures/items were carefully chosen and validated to meet the goals of our study (see Appendix A).

4.2. Data Collection Strategy

In this study, we examined 27 item numbers against seven constructs. Chatterjee and Kar [35] underscored that the responses should range between 1:4 and 1:10, and in line with this, the recommended responses for our 27 item-based model should come between 108 and 270. Furthermore, additional responses should also be included to cover for the invalid responses [59]. Considering these inputs, we collected survey responses from 285 Kirana store owners (KSOs) hailing from five prominent metropolitan cities in India, namely Delhi, Kolkata, Bangalore, Hyderabad, and Chennai. The sampling of these 285 entrepreneurs was conducted randomly across these five cities. The survey activities spanned a duration of 6 months, taking place in the middle of 2022. The data were collected both physically using printed survey forms and digitally using online survey forms. Since India is a very diverse country with different languages in different regions of the country, the survey forms were translated in local vernacular languages (Hindi, Bengali, Kannada, Telugu, and Tamil) and then used for data collection. The responses were quantified and coded appropriately. The demographic characteristics of these KSOs are given in Table 1. The distribution shows that we considered 70.2% male KSOs, 52.9% KSOs were between 5 and 15 years of business age, and 55% had an intermediate education level. We assessed seven measures to understand the infrastructure required for digital transformation, including digital payments and RFID/QR code scanners. We also investigated the range of business activities where digital transformations are utilized such as the following: Business Finance and Accounting (38.9%); Financial Transaction/Receiving Payments (91.6%); Sales and Order Processing (31.6%); and Business Relationship (46.3%).

Table 1.

Demographic background of KSO.

5. Empirical Analysis

In the quantitative research, data were collected to quantify and analyze information with the aim of supporting or refuting the alternative knowledge claims. For the SEM analysis, a structural model was assessed after an analysis of the measurement model [60]. Relationships between the constructs and indicators were empirically assessed through a measurement model, while the relationships within the constructs were empirically assessed through a structural model. During the analysis, it was important that all the measurement criteria were met when testing the structural model. Several factors were considered while assessing measurement models, including convergent validity, reliability, and discriminant validity.

5.1. Analysis for Validity and Reliability

The average variance extracted (AVE) was used to evaluate a construct’s convergent validity. Hair et al. [60] found that if a construct’s AVE is larger than 0.50, it has a higher likelihood of explaining the variance for the selected indicators. On the other hand, reliability helps in assessing the goodness of a measure. It is a measure of how well the observed variable captures the true value and is less erroneous. Cronbach’s alpha is one of the common metrics for measuring reliability. Composite reliability examines the effectiveness of a construct’s items in measuring it. In this study, the acceptable lower values for Cronbach’s alpha were fixed as 0.6 [61]. The Loading Factor (LF) was also calculated to identify if the item identification (questionnaire) was accurate. If the value of LF exceeded 0.7, it could be said that item identification is accurate. In addition, the minimum permissible accepted limits for AVE and composite reliability were 0.5 and 0.6, respectively.

Table 2 shows the estimated values of CR, AVE, LF, and composite reliability for each of the constructs selected for our conceptual model. It was found that the lowest value of CR estimated was greater than 0.6. Also, the values for LF, AVE and composite reliability exceeded the least accepted numbers. As a result, it can be said that all the constructs used in this study are reliable and consistent.

Table 2.

Measurement model results.

5.2. Test for Discriminant Validity

The discriminant validity of a measurement model can be defined as the unlikeness among the constructs. In other words, discriminant validity is confirmed when items constituting one construct could strongly explain the construct, but weakly interpret other constructs. If Average Variance (AV) is shown to be higher than the correlation coefficients of one construct with other constructs, the discriminant validity is established. Table 3 provides the estimated AV values and accompanying correlation coefficients. Table 3 displays the values of correlation coefficients in off-diagonal positions and AVs in diagonal positions. The AVs are represented by the numbers in bold typefaces. The results reveal that the AVs of a construct were bigger than of all the correlation coefficient values. Discriminant validity was thus confirmed. Another technique to ensure discriminant validity is right is to use a test. When the cross-loadings are lower than all the loadings, discriminant validity is said to be confirmed. After computing the cross-loadings, it was discovered that the loadings were higher. As a result, discriminant validity is proven.

Table 3.

Descriptive statistics and discriminant validity of measures.

5.3. SEM Analysis

To validate the proposed model, which was estimated using AMOS 26 software, various fit indices such as Adjusted GFI (AGFI), Comparative Fit Index (CFI), Goodness of Fit Index (GFI), Root Mean Square Error (RMSE), and Tucker Lewis index (TLI) should be estimated. Table 4 lists all these indices. All the parameters were found to be within the admissible limits, and therefore it can be said that the proposed model is in order.

Table 4.

Model Fit Summary.

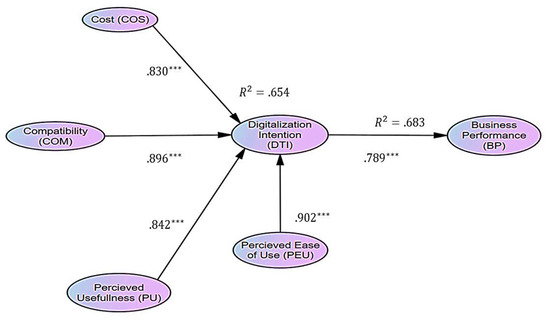

Figure 2 illustrates the key results including the estimates, levels of significance, and determinant coefficients. The complete detailed findings are provided in Table 5.

Figure 2.

Proposed model with the estimates, levels of significance, and determinant coefficients. Note: *** p value is less than 0.001.

Table 5.

SEM Results using AMOS.

5.4. Common Method Bias

As pointed out by Sreen et al. [59] and others [35], when the same research instrument/questionnaire using the same method (online survey) is used to collect data for predictors as well as dependent variable(s), there are chances that the data sample of the study may involve the issue of common method bias. To address this problem, a single-factor test of Harman [62] was conducted. With the help of un-rotated exploratory factor analysis, it was found that 40.1% of variance could be explained from the factors considered in the analysis, which is well below the recommended cut-off value of 50%, implying that no single factor alone can explain majority of the variance. Thus, there is no common method bias in the research.

5.5. Results from Analysis

This study provides a conceptual model by identifying seven constructs and developing six hypotheses. SEM analysis was thus used to validate this conceptual paradigm. All the hypotheses were found to be supported after validation. According to the estimation of the determinant’s coefficients (R2), which came out to be 0.654, the PEU, PEOU, COM, and COS could explain and interpret the adoption of digitalization to an extent of about 65.4%. Out of all these independent variables, the impact of Perceived Usefulness (PEU) and Compatibility (COM) came out to be the maximum since the magnitude of path coefficients for both the variables were around 0.860 with a *** significance level (p < 0.01). This hypothesis is supported in this study and shows that the pandemic has motivated small unorganized neighborhood retail stores (Kirana) to adopt digital technologies. Furthermore, as the coefficient of determinant was 0.783, the adoption of digital technology could explain and interpret the impact on business performance to the tune of 78.3%. The conceptual model has an explanatory power of 68.3%.

6. Discussion

The two hypotheses from the TAM model were found to be supported in our study. The significant results for PEU and PEOU are consistent with the earlier findings [35,39]. In addition, the inclusion of these two factors (PEU and PEOU) covers several important components explicitly and implicitly. For example, PEU shows the levels of trust that goes into adopting digital technologies for better performance and effectiveness, but at the same time, it also implicitly covers the levels of risk associated with the adoption of digital technologies. Additionally, it was observed that the COM and COS positively and significantly affects the adoption of digital technology, supporting the earlier findings [63]. This finding is intuitive as well since the unorganized neighborhood Kirana stores in an emerging market like that of India operates in a resource-scarce situation, and thus the decision-making process is heavily influenced by cost. Also, as illustrated in Table 1, 87% of the Kirana stores surveyed in our study have used free mobile fintech platforms like Google Pay, and other free supplementary fintech platforms provided by banks, such as ATM Card Machines, Online Payment Systems and Internet Banking. Hence, it further strengthens our line of argument that cost is a major factor affecting the adoption of digitalization in resource-constrained unorganized sector microbusinesses such as Kirana stores. The hypothetical relationship between digitalization and business performance is very strong, as exhibited by our findings. Also, as illustrated in Table 1, the business activities that are enhanced due to digitalization in such businesses include finance and accounting, financial transactions and receiving payments, sales, and order processing, and maintaining business relationships with customers and other partners. A mighty 91.6% of the Kirana stores owners agreed to the use of digital technology in their financial transactions and in receiving payments, which has a large impact on the overall business performance.

The use of digital technologies turned out to be helpful for the Unorganized Localized Retail Outlets Stores (Kirana stores) because of the improved efficiency, cost-effectiveness and better outreach. There has been a voluminous amount of literature on digital technology adoption by customers during the pandemic period. Also, several studies have also focused on digital technology adoption amongst businesses in organized sectors during the COVID-19 pandemic period. For instance, there are studies on social media adoption, cloud computing adoption, blockchain adoption amongst organized sector businesses such as educational institutions [64].

The ‘black swan event’ of COVID-19 significantly impacted everything across the globe, with unorganized microbusinesses like Kirana stores being influenced by unseen strong forces. Rather than delaying the adoption of digitalization, KSOs had to focus on the benefits it would bring. An essential facet for coping with pandemic forces is the capability of a system to adapt, change, and deal with shock, while preserving its fundamental role and structure [65]. In response to increasing disruptions such as COVID-19, Kirana stores sought the means to fulfill their needs for acquiring new customers, serving and retaining existing ones, conducting financial transactions, and tracking orders in turbulent circumstances. Hence, digitalization was immensely crucial for such businesses, providing them with the ability to cope with and excel in unexpected events and perform more effectively. The results of this study provide various thoughts for policymakers and practitioners to reflect upon when designing effective strategies for pushing digital technologies for the unorganized businesses at the bottom of the pyramid.

6.1. Theoretical Contributions

This study tried to theorize four factors, COS, PEU, COM, and PEOU, that have some impact on the intention of unorganized neighborhood retail outlet stores (Kirana stores) to adopt digital technologies. The adoption of digital technologies might improve these unorganized neighborhood retail businesses’ performances overall. This study examined whether Kirana stores in India should employ digital technologies to help them sustain their operations in the post-pandemic scenario. Several important factors that influence the motivation for the adoption of digital technologies were included in this study and thus provide an important theoretical contribution in explaining their impact on intention as well as performance. Using the PEU measure, factors such as performance, effectiveness, risk, and trust were considered [26,36,52]. With the PEOU measure, we considered one’s ability to adopt the digital technologies [53,54]. This study has also integrated two important constructs (PEU and PEOU) with one construct from UTAUT2 [35,39]. The cost (COS) construct signifies the affordability of those digital technologies. Also, construct compatibility was adopted from the literature as an independent measure.

Lastly, we highlighted the pandemic’s effects as playing a key role in creating a need to adopt digital technology to stay relevant. Hence, the proposed theoretical model shows the impact of these constructs on the adoption of digital technologies. The results help us to claim that the model proposed seems to be correct. We are of the opinion that the findings of the research can be extrapolated to other developing nations with economies like India to form conclusions about the adoption of digital technology in the unorganized sector.

Several key contributions have been made by this study. Firstly, it marks the inaugural endeavor to integrate the TAM and UTAUT2 theories for analyzing the digitalization intention within unorganized neighborhood retail outlets, specifically focusing on Kirana stores. The factors were meticulously adapted and tailored to better suit the nuances of the unorganized neighborhood retail sector, particularly in burgeoning markets like that of India. Secondly, our research assumes critical significance within the contemporary post-COVID-19 landscape from a pragmatic standpoint. Following the pandemic, both businesses and consumers have undergone substantial transformations across organized and unorganized neighborhood segments alike. The digitalization-induced evolution in the business models of these unorganized Kirana stores renders them exceptionally pertinent in addressing the varied hyper-localized consumer demands within their respective target segments. Thirdly, most technology adoption studies have focused on digital transformation for organized sector businesses. Digitalization intention has been introduced, for the first time, as an outcome variable in an unorganized sector segment in our study.

6.2. Managerial Contributions

This study investigated how different factors could motivate small unorganized neighborhood retail stores to adopt the digital technologies to improve the performance of their businesses. The results show that all the factors—PEU, PEOU, COM, and COS—have a big impact on how digital technologies are adopted. This is a result of the state’s initiatives for quicker digitalization and digital transformation as well as a positively changing business climate. For example, the relative competitive advantage that digital technologies provide in receiving payments motivated the unorganized neighborhood retail stores to expand their UPI services. This step was further complemented by the state through easy norms, no charges, and supporting infrastructure for such digital payment interfaces. In addition, the startup ecosystem in India also facilitated such an environment that pushed these digital technologies from the sidelines into the mainstream and further to the last mile at the bottom of the pyramid. For example, digital payment services such as Paytm or Bharatpe, and business management apps such as Khatabook, have made business activities much simpler and helped to improve their performance. The emancipation from the rivalry with formal enterprises and big companies such as Amazon, Big Basket, or Blinkit is another significant aspect that contributed to this favorable acceptance of digital technology. On the one hand, these big companies have emerged as a threat to the unorganized sector and small businesses that could not adopt digital technologies as consumer preference significantly shifted to online buying after the pandemic. On the other hand, businesses that were able to adopt digital technologies benefited immensely from these platforms such as Amazon marketplace. Hence, there is a dual benefit of adopting digital technologies. Therefore, strengthening these significant factors could be the important step towards accelerating the adoption of digital technologies. In this direction, the first step should be strengthening the facilitating conditions. For example, India should focus more on the BharatNet initiative that aims to connect 250,000 village panchayats with high-speed internet. This perspective situates the discussion in the larger context of the digital divide in emerging economies. Unless this divide is mitigated using various initiatives for internet connectivity, affordable infrastructure, and digital literacy, there would not be a sustainable solution. Finally, the pandemic also showed a significant impact on the adoption on digital technologies, and this presents with an important underlying issue. If the present-day situation necessitates the adoption of newer and much more complex digital technologies, what could be the future of those unorganized neighborhood retail stores which are unable to adopt these digital technologies? Policymakers and practitioners need to be on the lookout for ways to improve the capabilities of those at the base of the pyramid so that they can take advantage of the opportunities offered by the digital market. The policymakers and practitioners should focus on making these digital technologies even more inclusive such that the small businesses which find it difficult to adopt these technologies could cross those barriers of adoption.

The current study has provided several managerial implications for small retail business owners, policymakers, technology providers, and support organizations in the emerging economies. Since cost has been found as a significant factor affecting digital adoption, unorganized retailers should seek cost-effective digital solutions and possibly leverage government subsidies (both central and state governments) or financial assistance programs designed to encourage digitalization. Ensuring compatibility of new digital tools with existing business processes is crucial, requiring unorganized small retail owners to evaluate the compatibility of digital solutions to minimize disruptions and maximize efficiency. To enhance the perceived ease of use, it is essential that these unorganized retailers obtain adequate training and attend more digital awareness programs on the effective usage of digital tools. Technology providers and support organizations can demonstrate the tangible benefits of digitalization to unorganized retail segment, such as increased sales, better inventory management, and enhanced customer engagement, which can subsequently improve the perceived usefulness among them. This demonstration can be in the form of case studies and success stories, serving as powerful perceived usefulness vehicles. The pandemic has accelerated digital adoption, and unorganized retailers should leverage this momentum to build more resilient business models by using digital platforms for online sales, contactless payments, and efficient supply chain management. Understanding and adapting to changing consumer preferences, such as the increased preference for online shopping and digital payment methods, can help unorganized retail outlets remain competitive. Business associations of unorganized retailers should advocate for better digital infrastructure, such as improved internet connectivity and reliable power supply, which are essential for effective digitalization. Also, small retail outlets or their business associations can form alliances or partnerships with technology providers, fintech companies, and other stakeholders to access affordable digital solutions and technical expertise. Unorganized retailers should keep themselves abreast of the latest digital trends and innovations by attending more and more digital awareness programs to make informed decisions about adopting new technologies that can further enhance their business operations. By addressing all these, unorganized localized retail outlets in India can effectively navigate the digitalization journey, improve their business performance, and remain competitive in a rapidly evolving market.

7. Conclusions and Directions for Future Research

This study has made significant research contributions by being the first to integrate the TAM and UTAUT2 models to analyze digitalization intention in unorganized neighborhood retail outlets, specifically in Kirana stores. It has identified and validated key factors—cost, compatibility, perceived ease of use, and perceived usefulness—that influence digital adoption in the unorganized segment of an emerging economy. The research has highlighted the critical need for digital technologies in sustaining operations in the post-COVID-19 era, offering practical insights for unorganized retail sectors. Additionally, it has filled a gap by focusing on digitalization in the unorganized sector, providing a framework that can be extrapolated to similar emerging economies.

It is evident from the study that digitalization adoption holds substantial potential to enhance the operational performance of such microbusinesses operating within the unorganized sector. Furthermore, the increased accessibility of mobile devices and the internet, coupled with the availability of user-friendly and free mobile applications such as QR code scanning, Google Pay, and PhonePe, collectively contributes to the advancement of digitalization within the unorganized neighborhood retail segment in India. However, it is also true that in a resource-scarce and digitally divided economy such as India, unorganized neighborhood retailers may not have the adequate skills, infrastructure, and awareness to effectively utilize all variants of digital technologies. At the base of the pyramid, digital technology adoption is still challenging, even though the unorganized sector has accelerated the adoption of digital technologies due to the pandemic. However, in the present scenario, with no further shocks, the adoption of such technologies can be rapidly carried out through government interventions. In this setting, the government should take proper measures and provide incentives, such as digital literacy campaigns, and the availability of affordable technology in vernacular languages should be emphasized. All of these might improve the circumstance, which would finally result in economic growth for the nation. In the future, a comparative study can be undertaken to understand the adoption behavior of unorganized sectors across different emerging economies. Also, longitudinal studies can be performed in multiple regions in India on post-pandemic technology adoption behavior. Moreover, in our study, we selected unorganized neighborhood retail stores from five major metropolitan cities of India, i.e., Delhi NCR, Chennai, Bangalore, Hyderabad, and Kolkata. India is a vast country with huge diversity, where technology infrastructure, electricity availability, internet availability, education, and awareness varies considerably across different regions. Hence, future research can use samples from rural areas and perform a comparative analysis.

This research has some limitations as well as a scope for future research as follows. The focus of the study was the metropolitan cities of India that truly represent the diversity in population, language, and behavior. However, India largely consists of small towns and rural markets. The digital adoption rate differs widely across these geographies. Future research may include this digital divide in a more vivid way, and the variables used in this study can be tested for those geographies. The government interventions aimed at accelerating or supporting digital adoption were not included in the present study, and thus another possible extension of the study would be to test the impact of those interventions. Furthermore, the study focused on digitalization adoption in general and did not take specific technology adoption, such as social media or payment gateways, into account. Future studies can also consider moderator variables such as social identity or gender in addition to the model tested in this study. Lastly, this research can act as a basis to further study the differences in digital adoption by conducting a cross-sectional study on other emerging economies such as Indonesia, Nigeria, and Bangladesh.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/jtaer19030083/s1, Table S1: Questionnaire items used for Pilot Study; Table S2: Reliability Analysis of Pilot Sample data-Phase 1 (30 respondents); Table S3: Reliability Analysis of Phase 2 Pilot Sample with modified questionnaire (30 respondents).

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, B.B., S.K., P.V. and M.M.; methodology, B.B., S.K., P.V.; software, B.B., S.K. and P.V.; validation, B.B., S.K. and P.V.; formal analysis, M.M.; data curation, B.B., S.K. and P.V.; writing—original draft preparation, B.B., S.K. and P.V.; writing—review and editing, M.M.; visualization, B.B., S.K. and P.V.; supervision, M.M.; project administration, B.B. and S.K. and P.V.; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not Applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Dataset available on request from the authors.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Questionnaire Summary.

Table A1.

Questionnaire Summary.

| Variable | Factor | Measurement Items | Adapted from |

|---|---|---|---|

| Perceived Usefulness | PU1 | Digital platforms are useful for business | [35] |

| PU2 | Digital platforms are a valuable tool for the business | [66] | |

| PU3 | Digital platforms enhance the productivity of the business | [67,68] | |

| PU4 | Digital platforms help better management of business | [67,68] | |

| Perceived Ease of Use | PEU2 | Conducting business through digital platforms is easy | [35] |

| PEU3 | Applying digital platforms for my business is easy | [35] | |

| PEU4 | Integrating business partners on digital platforms is easy | [35] | |

| Business Performance | BP1 | My business performance has improved by using digital platforms | [35] |

| BP2 | My sales have significantly increased compared to past after using digital platforms | [67,68] | |

| BP3 | My customers feel more connected with my business after using digital platforms | [67,68] | |

| BP6 | Digital platforms have made my business more competitive | [35] | |

| Compatibility | COM1 | Our enterprise is ready for using digital platforms for different business purposes | [63,69] |

| COM2 | I use digital platforms regularly for business purposes | [35] | |

| COM3 | My organization possess the capability for switching to digital platforms | [35] | |

| COM4 | Our business is compatible for using digital platforms for marketing purpose | [63] | |

| Cost | COS2 | My cost of promoting products/service have gone down using digital platforms | [70,71] |

| COS3 | Cost of identifying new customers has been reduced through use of digital platforms | [72] | |

| COS4 | Customer awareness and training cost have diminished by use of digital platforms | [70,73] | |

| COS5 | The overall cost of conducting business have gone down using digital platforms | [68] | |

| Digitalization Intention | DT1 | Our enterprise has realized the importance of Digitalization | [37,74] |

| DT3 | Our business is committed to adopt/use tools, technologies and platforms towards Digitalization | [37,74] | |

| DT4 | We are in the process of transforming our business to digital era | [37,74] |

References

- Maiti, M.; Kotliarov, I.; Lipatnikov, V. A future triple entry accounting framework using blockchain technology. Blockchain Res. Appl. 2021, 2, 100037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, C.; Quayson, M.; Sarkis, J. COVID-19 pandemic digitization lessons for sustainable development of micro-and small-enterprises. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2021, 27, 1989–2001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matarazzo, M.; Penco, L.; Profumo, G.; Quaglia, R. Digital transformation and customer value creation in Made in Italy SMEs: A dynamic capabilities perspective. J. Business. Res. 2021, 123, 642–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravichandran, T. Exploring the relationships between IT competence, innovation capacity and organizational agility. J. Strategic. Inf. Syst. 2018, 27, 22–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westerman, G.; Bonnet, D.; McAfee, A. The nine elements of digital transformation. MIT Sloan Manag. Rev. 2014, 55, 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Begley, S.; Marohn, E.; Mikha, S.; Rettaliata, A. Digital Disruption at the Grocery Store, Mckinsey & Company. 2020. Available online: https://www.mckinsey.com/~/media/McKinsey/Industries/Retail/Our%20Insights/Digital%20disruption%20at%20the%20grocery%20store/Digital-disruption-at-the-grocery-store.pdf (accessed on 1 September 2023).

- Maiti, M.; Vuković, D.; Mukherjee, A.; Paikarao, P.D.; Yadav, J.K. Advanced data integration in banking, financial, and insurance software in the age of COVID-19. Softw. Pract. Exp. 2022, 52, 887–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Veldhoven, Z.V.; Vanthienen, J. Digital transformation as an interaction-driven perspective between business, society, and technology. Electron. Mark. 2021, 32, 629–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maier, E. Supply and demand on crowdlending platforms: Connecting small and medium-sized enterprise borrowers and consumer investors. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2016, 33, 143–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatterjee, S.; Chaudhuri, R.; Vrontis, D.; Thrassou, A.; Ghosh, S.K. ICT-enabled CRM system adoption: A dual Indian qualitative case study and conceptual framework development. J. Asia Bus. Stud. 2020, 15, 257–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kundu, S.C.; Mor, A.; Kumar, S.; Bansal, J. Diversity within management levels and organizational performance: Employees’ perspective. J. Adv. Manag. Res. 2019, 17, 110–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loayza, N. Costs and Trade-Offs in the Fight against the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Developing Country Perspective. World Bank Res. Policy Briefs 2020, 148535. [Google Scholar]

- Shekhar, K.C.; Mansoor, K. COVID-19: Lockdown impact on informal sector in India. Transport 2020, 13, 13–14. [Google Scholar]

- Mishra, V.; Walsh, I.; Srivastava, A. Merchants’ adoption of mobile payment in emerging economies: The case of unorganised retailers in India. Eur. J. Inf. Syst. 2021, 31, 74–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, G.; Gao, X. Precision retail marketing strategy based on digital marketing model. Sci. J. Bus. Manag. 2019, 7, 33–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mostaghel, R.; Oghazi, P.; Parida, V.; Sohrabpour, V. Digitalization driven retail business model innovation: Evaluation of past and avenues for future research trends. J. Bus. Res. 2022, 146, 134–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurnia, S.; Choudrie, J.; Mahbubur, R.M.; Alzougool, B. E-commerce technology adoption: A Malaysian grocery SME retail sector study. J. Bus. Res. 2015, 68, 1906–1918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szegedi, K. Consumers Want to Go Shopping again, but Uncertainty Remains: The Swiss Retail Sector and the COVID-19 Crisis. Deloitte. 2022. Available online: https://www2.deloitte.com/ch/en/pages/consumer-industrial-products/articles/kundschaft-will-zurueck-in-die-laeden.html (accessed on 24 September 2022).

- Kumar, S.; Kumar, D.; Sengupta, K.; Giri, T.K. Through convergence and governance: Embedding empowerment in community development interventions. Community Dev. J. 2022, 57, 295–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Showrav, D.G.Y.; Hassan, M.A.; Anam, S.; Chakrabarty, A.K. Factors influencing the rapid growth of online shopping during covid-19 pandemic time in Dhaka City, Bangladesh. Acad. Strateg. Manag. J. 2021, 20, 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez-Espíndola, O.; Chowdhury, S.; Dey, P.K.; Albores, P.; Emrouznejad, A. Analysis of the adoption of emergent technologies for risk management in the era of digital manufacturing. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2022, 178, 121562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Battistoni, E.; Gitto, S.; Murgia, G.; Campisi, D. Adoption paths of digital transformation in manufacturing SME. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2023, 255, 108675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acquila-Natale, E.; Chaparro-Peláez, J.; Del-Río-Carazo, L.; Cuenca-Enrique, C. Do or Die? The Effects of COVID-19 on Channel Integration and Digital Transformation of Large Clothing and Apparel Retailers in Spain. J. Theor. Appl. Electron. Commer. Res. 2022, 17, 439–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Chen, H.; Liang, H. Did New Retail Enhance Enterprise Competition during the COVID-19 Pandemic? An Empirical Analysis of Operating Efficiency. J. Theor. Appl. Electron. Commer. Res. 2023, 18, 352–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos-Jaén, J.M.; Gimeno-Arias, F.; León-Gómez, A.; Palacios-Manzano, M. The Business Digitalization Process in SMEs from the Implementation of e-Commerce: An Empirical Analysis. J. Theor. Appl. Electron. Commer. Res. 2023, 18, 1700–1720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adhikary, A.; Diatha, K.S.; Borah, S.B.; Sharma, A. How does the adoption of digital payment technologies influence unorganized retailers’ performance? An investigation in an emerging market. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2021, 49, 882–902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goswami, P.; Mishra, M.S. Would Indian consumers move from kirana stores to organized retailers when shopping for groceries? Asia Pac. J. Mark. Logist. 2009, 21, 127–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soluk, J.; Kammerlander, N.; Darwin, S. Digital entrepreneurship in developing countries: The role of institutional voids. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2021, 170, 120876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sengupta, A. Emergence of modern Indian retail: An historical perspective. Int. J. Retail Distrib. Manag. 2008, 36, 689–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IBEF. Retail Industry in India, India Brand Equity Foundation. 2022. Available online: https://www.ibef.org/industry/retail-india (accessed on 1 September 2023).

- Rani, E. Supermarkets vs. Small Kirana Stores. J. Bus. Manag. 2013, 10, 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Patil, G.R.; Dhore, R.; Bhavathrathan, B.K.; Pawar, D.S.; Sahu, P.; Mulani, A. Consumer responses towards essential purchases during COVID-19 pan-India lockdown. Res. Transp. Bus. Manag. 2022, 43, 100768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Live Mint. Daily UPI Transactions Jump 50% to ₹36 cr, Says RBI, 7 March 2023. Available online: https://www.livemint.com/news/india/daily-upi-transactions-jump-50-to-rs-36-cr-says-rbi-11678191749546.html (accessed on 1 September 2023).

- Shree, S.; Pratap, B.; Saroy, R.; Dhal, S. Digital payments and consumer experience in India: A survey based empirical study. J. Bank. Financ. Technol. 2021, 5, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatterjee, S.; Kumar Kar, A. Why do small and medium enterprises use social media marketing and what is the impact: Empirical insights from India. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2020, 53, 102103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baishya, K.; Samalia, H.V. Extending unified theory of acceptance and use of technology with perceived monetary value for smartphone adoption at the bottom of the pyramid. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2020, 51, 102036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkatesh, V.; Morris, M.G.; Davies, G.B.; Davies, F.D. User Acceptance of Information Technology: Toward a Unified View. MIS Q. 2003, 27, 425–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.; Kozar, K.A.; Larsen, K.R.T. The technology acceptance model: Past, present and future. Commun. Assoc. Inf. Syst. 2003, 12, 752–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkatesh, V.; Thong, J.Y.; Xu, X. Consumer acceptance and use of information technology: Extending the unified theory of acceptance and use of technology. MIS Q. 2012, 36, 157–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deb, R.; Samalia, H.V.; Prusty, S.K. The role of informal competition in driving export propensity of emerging economy firms: An attention based approach. Int. J. Sociol. Soc. Policy 2020, 40, 184–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dwivedi, Y.K.; Rana, N.P.; Janssen, M.; Lal, B.; Williams, M.D.; Clement, M. An empirical validation of a unified model of electronic government adoption (UMEGA). Gov. Inf. Q. 2017, 34, 211–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaumotte, F.; Li, L.; Medici, A.; Oikonomou, M.; Pizzinelli, C.; Shibata, I.; Soh, J.; Tavares, M.M. Digitalization during the COVID-19 Crisis: Implications for Productivity and Labor Markets in Advanced Economies; Staff Discussion Notes 2023 (SDN/2023/003); International Monetary Fund: Washington, DC, USA, 2023; pp. 1–56. [Google Scholar]

- Abad, P.; De la Fuente-Cabrero, C.; González-Serrano, L.; Talón-Ballestero, P. Determinants of successful revenue management. Tour. Rev. 2019, 74, 666–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukherjee, R. Jio sparks Disruption 2.0: Infrastructural imaginaries and platform ecosystems in ‘Digital India’. Media Cult. Soc. 2019, 41, 175–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Centobelli, P.; Cerchione, R.; Ertz, M. Agile supply chain management: Where did it come from and where will it go in the era of digital transformation? Ind. Mark. Manag. 2020, 90, 324–345. [Google Scholar]

- Lokuge, S.; Sedera, D.; Grover, V.; Dongming, X. Organizational readiness for digital innovation: Development and empirical calibration of a construct. Inf. Manag. 2019, 56, 445–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jöhnk, J.; Weißert, M.; Wyrtki, K. Ready or not, AI comes—An interview study of organizational AI readiness factors. Bus. Inf. Syst. Eng. 2021, 63, 5–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Wang, X.; Chu, Z. Capacity sharing, product differentiation and welfare. Econ. Res.-Ekon. Istraživanja 2020, 33, 107–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, F.; Bagozzi, R.; Warshaw, P. User acceptance of computer technology: A comparison of two theoretical models. Manag. Sci. 1989, 35, 982–1003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, F.D. Perceived usefulness, perceived ease of use, and user acceptance of information technology. MIS Q. 1989, 13, 319–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomez-Trujillo, A.M.; Gonzalez-Perez, M.A. Digital transformation as a strategy to reach sustainability. Smart Sustain. Built Environ. 2022, 11, 1137–1162. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, T.; Chiu, W. Consumer acceptance of sports wearable technology: The role of technology readiness. Int. J. Sports Mark. Spons. 2019, 20, 109–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amin, H.; Abdul-Rahman, A.-R.; Ramayah, T.; Supinah, R.; Mohd-Aris, M. Determinants of online Waqf acceptance: An empirical investigation. Electron. J. Inf. Syst. Dev. Ctries. 2014, 60, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuo, Y.F.; Yen, S.N. Towards an understanding of the behavioural intention to use 3G mobile value-added services. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2009, 25, 103–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Lee, K.H. Influences of motivations and lifestyles on intentions to use smartphone applications. Int. J. Advert. 2018, 37, 385–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calvino, F.; Criscuolo, C. Business dynamics and digitalisation. OECD Science, Technology and Innovation Policy Papers 62. 2019. Available online: https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/content/paper/6e0b011a-en (accessed on 1 September 2023).

- Duerr, S.; Holotiuk, F.; Wagner, H.T.; Beimborn, D.; Weitzel, T. What is digital organizational culture? Insights from exploratory case studies. In Proceedings of the 51st Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences, HICSS 2018, Hilton Walkoloa Village, HI, USA, 3–6 January 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Sabherwal, R.; Chan, Y.E. Alignment between business and IS strategies: A study of prospectors, analyzers, and defenders. Inf. Syst. Res. 2001, 12, 11–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sreen, N.; Purbey, S.; Sadarangani, P. Impact of culture, behavior and gender on green purchase intention. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2018, 41, 177–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J., Jr.; Black, W.C.; Babin, B.J.; Anderson, R.E. Multivariate Data Analysis, 7th ed.; Prentice Hall: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.F.; Black, W.C.; Babin, B.J.; Anderson, R.E.; Tatham, R.L. Análise Multivariada de Dados, 6th ed.; Bookman Editora: Porto Alegre, Brazil, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Harman, H.H. Modern Factor Analysis, 3rd ed.; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Derham, R.; Cragg, P.; Morrish, S. Creating Value: An SME and Social media, PACIS 2011 Proceedings. Paper 53. 2011. Available online: http://aisel.aisnet.org/pacis2011/53 (accessed on 1 September 2023).

- Sharma, S.K.; Dwivedi, Y.K.; Metri, B.; Lal, B.; Elbanna, A. (Eds.) Transfer, Diffusion and Adoption of Next-Generation Digital Technologies: IFIP WG 8.6 International Working Conference on Transfer and Diffusion of IT, TDIT 2023, Nagpur, India, 15–16 December 2023, Proceedings, Part I; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; Volume 697. [Google Scholar]

- Adobor, H.; McMullen, R.S. Supply chain resilience: A dynamic and multidimensional approach. Int. J. Logist. Manag. 2018, 29, 1451–1471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alalwan, A.A.; Rana, N.P.; Dwivedi, Y.K.; Algharabat, R.S. Social media in marketing: A review and analysis of the existing literature. Telemat. Inform. 2017, 34, 1177–1190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aral, S.; Dellarocas, C.; Godes, D. Introduction to the special issue—Social media and business transformation: A framework for research. Inf. Syst. Res. 2013, 24, 3–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, A.Q.H.; Andreev, P.; Benyoucef, M.; Duane, A.; O’Reilly, P. Managing an organization’s social media presence: An empirical stages of growth model. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2017, 37, 1405–1417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, S.-B.; Cho, E. Convergence adoption model (CAM) in the context of a smart car service. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2016, 60, 500–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, A.M.; Haenlein, M. Users of the world, unite! The challenges and opportunities of Social Media. Bus. Horiz. 2010, 53, 59–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dwivedi, Y.K.; Kapoor, K.K.; Chen, H. Social media marketing and advertising. Mark. Rev. 2015, 15, 289–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Fan, C.; Yao, W.; Hu, X.; Mostafavi, A. Social media for intelligent public information and warning in disasters: An interdisciplinary review. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2019, 49, 190–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, K.J.; Shin, D.H. An acceptance model for smart watches: Implications for the adoption of future wearable technology. Internet Res. 2015, 25, 527–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkatesh, V.; Davis, F.D. A theoretical extension of the technology acceptance model: Four longitudinal field studies. Manag. Sci. 2000, 46, 186–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).