The Emerging Phenomenon of Shopstreaming: Gaining a More Nuanced Understanding of the Factors Which Drive It

Abstract

1. Introduction

- RQ1.

- In the context of shopstreaming, what are the key influencers of perceived benefit and how do they affect consumer attitude and intention to purchase?

- RQ2.

- To what extent does attitude mediate the impact of perceived benefit on intention to purchase?

- RQ3.

- To what extent do perceived platform quality and seller advice moderate the mediated relationship?

2. Literature Review and Theoretical Basis

2.1. The Rise and Advantages of Shopstreaming in Modern E-Commerce

2.2. Theoretical Frameworks for Understanding Human Behaviour

2.2.1. Theory of Planned Behaviour (TPB)

2.2.2. Stimulus–Organism–Response Theory (ESOR)

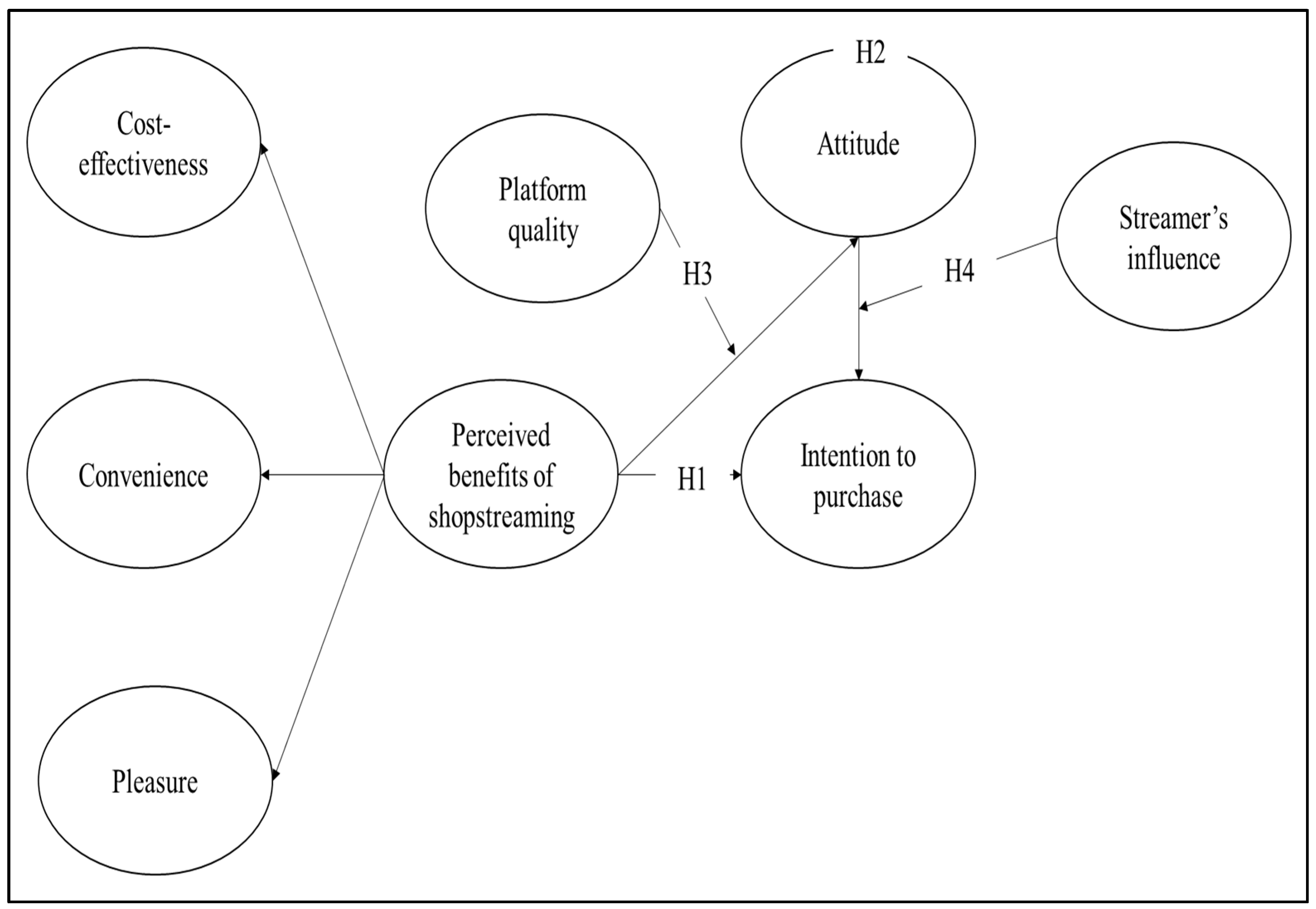

3. Development Hypotheses

3.1. Perceived Benefits of Shopstreaming and Intention to Purchase

3.2. Attitude

3.3. Perceived Platform Quality

3.4. Streamer’s Influence

4. Research Methodology

4.1. Development of the Survey Instrument

- Rephrasing certain items to improve clarity and comprehension;

- Strategically reordering items to maintain a logical flow and coherence in the survey structure;

- Adding explicit instructions for participants to accurately complete the questionnaire.

4.2. Data Collection and Sampling

4.3. Nonresponse Bias

4.4. Method of Analysis

4.5. Ethics

5. Result

5.1. Testing the Measurement Model

5.2. Examination of Common Method Variance and Bias

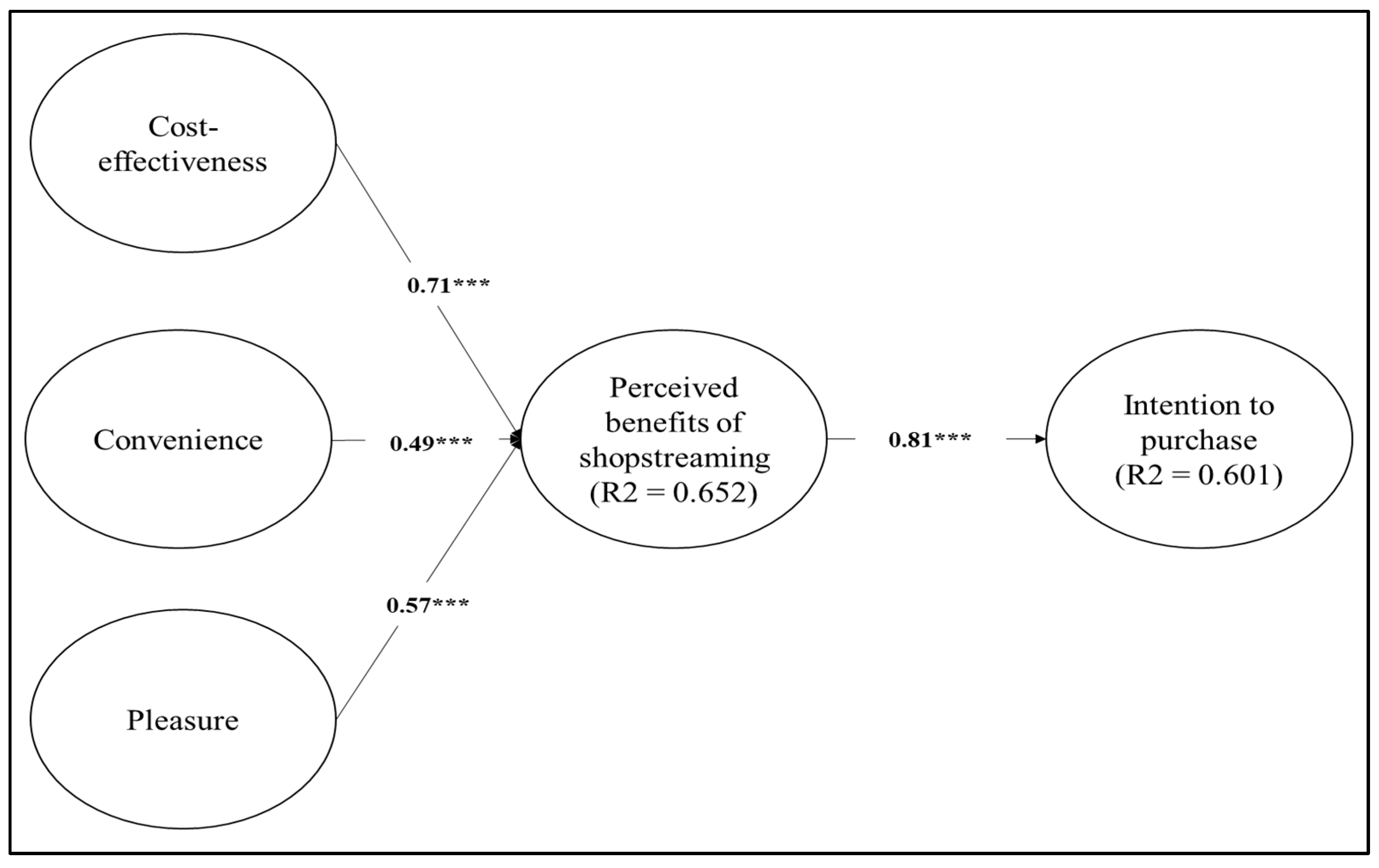

5.3. Findings of the Research Hypotheses

6. Discussion

6.1. Theoretical Implications

6.2. Practical Implications

7. Conclusions, Limitations and Future Research

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zuo, R.; Xiao, J. Exploring Consumers’ Impulse Buying Behavior in Live Streaming Shopping; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 610–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ameer Hussain, A.; Sharma, B.K.; VH, C.; Kazim, S. Cognitive and Affective Components Induced Impulsive Purchase: An Empirical Analysis. J. Promot. Manag. 2024, 30, 901–928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, F.; Lin, Y.; Jiang, X. Influence Mechanism of Consumers’ Characteristics on Impulsive Purchase in E-Commerce Livestream Marketing. Comput. Human. Behav. 2023, 148, 107894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Ye, Y. Who Watches Live Streaming in China? Examining Viewers’ Behaviors, Personality Traits, and Motivations. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 1607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khoi, N.H.; Le, A.N.-H. Real-Time Interactivity and Impulsive Buying in Livestreaming Commerce: The Focal Intermediary Role of Inspiration. Int. J. Hum. Comput. Interact. 2024, 40, 2938–2953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, H.; Zhao, C.; Fan, D.X.F.; Buhalis, D. The Effect of Hotel Livestreaming on Viewers’ Purchase Intention: Exploring the Role of Parasocial Interaction and Emotional Engagement. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2022, 107, 103348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Zhang, L.; Chen, Q. The Effects of Tourism E-Commerce Live Streaming Features on Consumer Purchase Intention: The Mediating Roles of Flow Experience and Trust. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 995129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Liu, T.; Zhu, Y.; Wang, H.; Wang, X.; Zhao, S. The Influence of Consumer Perception on Purchase Intention: Evidence from Cross-Border E-Commerce Platforms. Heliyon 2023, 9, e21617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guzana, M.; Msosa, S.K. The Challenges in Employing Digital Marketing as a Tool for Improving Sales at Selected Retail Stores in the Transkei Region. EUREKA Social. Humanit. 2022, 3–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q. Live Streaming–the New Era of Online Shopping; Atlantis Press: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wongkitrungrueng, A.; Assarut, N. The Role of Live Streaming in Building Consumer Trust and Engagement with Social Commerce Sellers. J. Bus. Res. 2020, 117, 543–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Liu, Y.; Wang, Y.; Zhao, L. How to Retain Customers: Understanding the Role of Trust in Live Streaming Commerce with a Socio-Technical Perspective. Comput. Human. Behav. 2022, 127, 107052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saprikis, V.; Markos, A.; Zarmpou, T.; Vlachopoulou, M. Mobile Shopping Consumers’ Behavior: An Exploratory Study and Review. J. Theor. Appl. Electron. Commer. Res. 2018, 13, 71–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Li, G.; Xie, X.; Wu, S. An Empirical Analysis of the Impacts of Live Chat Social Interactions in Live Streaming Commerce: A Topic Modeling Approach. Electron. Commer. Res. Appl. 2024, 65, 101397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mckinsey. It’s Showtime! How Live Commerce Is Transforming the Shopping Experience. Available online: https://www.mckinsey.com/capabilities/mckinsey-digital/our-insights/its-showtime-how-live-commerce-is-transforming-the-shopping-experience (accessed on 7 April 2024).

- Brigitte Korte. 32 Livestream Shopping Statistics to Know for 2024. Available online: https://fitsmallbusiness.com/livestream-shopping-statistics/ (accessed on 7 April 2024).

- Statista. Video Streaming (SVoD) – Worldwide. Available online: https://www.statista.com/outlook/dmo/digital-media/video-on-demand/video-streaming-svod/worldwide (accessed on 7 April 2024).

- Nick Vivarelli. Saudi Arabia Leads Streaming Gains in Gulf Arab Nations, as Pay-TV Market Contracts (EXCLUSIVE). Available online: https://variety.com/2022/digital/news/saudi-arabia-streaming-svod-1235187143/ (accessed on 7 April 2024).

- Zhang, Y.; Zhang, T.; Yan, X. Understanding Impulse Buying in Short Video Live E-Commerce: The Perspective of Consumer Vulnerability and Product Type. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2024, 79, 103853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Duan, Y. Strategic Live Streaming Choices for Vertically Differentiated Products. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2024, 76, 103582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Y.; Li, W.; Xue, J. What and How Driving Consumer Engagement and Purchase Intention in Officer Live Streaming? A Two-Factor Theory Perspective. Electron. Commer. Res. Appl. 2022, 56, 101223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, S.; Wu, M.; Liao, J. The Impact of Destination Live Streaming on Viewers’ Travel Intention. Curr. Issues Tour. 2023, 26, 184–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, N.; Xuan, C.; Chen, R. Different Roles of Two Kinds of Digital Coexistence: The Impact of Social Presence on Consumers’ Purchase Intention in the Live Streaming Shopping Context. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2024, 80, 103890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, L.; Zhang, N.; Huang, L. How the Source Dynamism of Streamers Affects Purchase Intention in Live Streaming E-Commerce: Considering the Moderating Effect of Chinese Consumers’ Gender. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2024, 81, 103949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lo, P.-S.; Dwivedi, Y.K.; Wei-Han Tan, G.; Ooi, K.-B.; Cheng-Xi Aw, E.; Metri, B. Why Do Consumers Buy Impulsively during Live Streaming? A Deep Learning-Based Dual-Stage SEM-ANN Analysis. J. Bus. Res. 2022, 147, 325–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosário, A.; Raimundo, R. Consumer Marketing Strategy and E-Commerce in the Last Decade: A Literature Review. J. Theor. Appl. Electron. Commer. Res. 2021, 16, 3003–3024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wongkitrungrueng, A.; Dehouche, N.; Assarut, N. Live Streaming Commerce from the Sellers’ Perspective: Implications for Online Relationship Marketing. J. Mark. Manag. 2020, 36, 488–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.V.; Pham, D.T.; Tran, S.T.T. Building Consumer Engagement in Live Streaming on Social Media: A Comparison of Facebook and Instagram Live. Int. J. Hum. Comput. Interact. 2024, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, L.; Xu, M.; Zheng, Y. Informative or Affective? Exploring the Effects of Streamers’ Topic Types on User Engagement in Live Streaming Commerce. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2024, 79, 103799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, B.; Wang, L.; Rasool, H.; Wang, J. Research on the Impact of Marketing Strategy on Consumers’ Impulsive Purchase Behavior in Livestreaming E-Commerce. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 905531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hewei, T.; Youngsook, L. Factors Affecting Continuous Purchase Intention of Fashion Products on Social E-Commerce: SOR Model and the Mediating Effect. Entertain. Comput. 2022, 41, 100474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, W.; Jiang, N.; Guo, Q. How Do Virtual Streamers Affect Purchase Intention in the Live Streaming Context? A Presence Perspective. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2023, 73, 103356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sastika, W.; Kusumahadi, K.; Hanifa, F.H.; Marcelino, D. E-Commerce Website Quality: Usability, Information, Service Interaction & Visual Quality on Customer Satisfaction. In Proceedings of the 2023 11th International Conference on Cyber and IT Service Management (CITSM), Makassar, Indonesia, NJ, USA, 10–11 November 2023; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA; pp. 1–7. [CrossRef]

- Hasibuan, N.F.; Putri, R.A.; Harahap, A.M. E-Commerce Application with Web Engineering Method Website Based. J. Comput. Netw. Archit. High. Perform. Comput. 2024, 6, 179–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, T.Y.; Matz, R.; Luo, L.; Xu, C. Gamification for Value Creation and Viewer Engagement in Gamified Livestreaming Services: The Moderating Role of Gender in Esports. J. Bus. Res. 2022, 145, 482–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krolow, P.J.; Dias, P.; Oliveira, S.M.L. How Small Companies Used Shopstreaming in Their Fight for Survival in a COVID-19 Scenario; IGI Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2022; pp. 76–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y. To Shop or Not: Understanding Chinese Consumers’ Live-Stream Shopping Intentions from the Perspectives of Uses and Gratifications, Perceived Network Size, Perceptions of Digital Celebrities, and Shopping Orientations. Telemat. Inform. 2021, 59, 101562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Sethi, S.; Zhang, Y. Seeing Is Believing: Does Live Streaming E-Commerce Make Brands More Shoppable? SSRN Electron. J. 2021. [CrossRef]

- Cai, J.; Wohn, D.Y.; Mittal, A.; Sureshbabu, D. Utilitarian and Hedonic Motivations for Live Streaming Shopping. In Proceedings of the 2018 ACM International Conference on Interactive Experiences for TV and Online Video, Seoul, Republic of Korea, 26–28 June 2018; ACM: New York, NY, USA, 2018; pp. 81–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Safira, A.M.; Novie, M. Pengaruh Live Streaming Dan Sales Promotion Terhadap Impulse Buying Yang Dimediasi Oleh Consumer Shopping Motivation (Studi Pada Gen Z Pengguna Shopee). J. Inform. Ekon. Bisnis 2024, 6, 197–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Z.; Yan, X.; Deng, J. How Social Presence Influences Consumer Well-Being in Live Video Commerce: The Mediating Role of Shopping Enjoyment and the Moderating Role of Familiarity. J. Theor. Appl. Electron. Commer. Res. 2024, 19, 725–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam, S.S.; Masukujjaman, M.; Makhbul, Z.K.M.; Ali, M.H.; Omar, N.A.; Siddik, A.B. Impulsive Hotel Consumption Intention in Live Streaming E-Commerce Settings: Moderating Role of Impulsive Consumption Tendency Using Two-Stage SEM. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2023, 115, 103606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Lu, Z.; Cao, P.; Chu, J.; Wang, H.; Wattenhofer, R. How Live Streaming Changes Shopping Decisions in E-Commerce: A Study of Live Streaming Commerce. Comput. Support. Coop. Work (CSCW) 2022, 31, 701–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ming, J.; Jianqiu, Z.; Bilal, M.; Akram, U.; Fan, M. How Social Presence Influences Impulse Buying Behavior in Live Streaming Commerce? The Role of S-O-R Theory. Int. J. Web Inf. Syst. 2021, 17, 300–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Statista. Transaction value of livestream commerce on Chinese online shopping platform Taobao in China from 2017 to 2022. Available online: https://www.trade.gov/market-intelligence/saudi-arabia-transportation-and-logistics-network-outlook (accessed on 7 April 2024).

- Statista. Change in livestream purchases from before to during the COVID-19 pandemic in selected regions worldwide in 2021. Available online: https://www.statista.com/statistics/1276981/change-livestream-commerce-usage-worldwide-region/ (accessed on 7 April 2024).

- Liu, X.; Kim, S.H. Beyond Shopping: The Motivations and Experience of Live Stream Shopping Viewers. In Proceedings of the 2021 13th International Conference on Quality of Multimedia Experience (QoMEX), Montreal, QC, Canada, 14–17 June 2021; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2021; pp. 187–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fauska, P.; Kryvinska, N.; Strauss, C. The Role of E-Commerce in B2B Markets of Goods and Services. Int. J. Serv. Econ. Manag. 2013, 5, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassen, Y.A.; Svensson, A. The Role of E-commerce for the Growth of Small Enterprises in Ethiopia. Electron. J. Inf. Syst. Dev. Ctries. 2014, 65, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Statista. Video Streaming (SVoD)-Saudi Arabia. 2024. Available online: https://www.statista.com/outlook/dmo/digital-media/video-on-demand/video-streaming-svod/saudi-arabia (accessed on 7 April 2024).

- Tertia Tay; Simon Wintels. Resellers: The unseen engine of Indonesian e-commerce. Available online: https://www.mckinsey.com/industries/retail/our-insights/resellers-the-unseen-engine-of-indonesian-e-commerce (accessed on 7 April 2024).

- Keerthana Tiwari. Rising Kingdom of Ecommerce: Post-Covid Online Retail Trends in Saudi Arabia. Available online: https://www.statista.com/topics/7723/e-commerce-in-saudi-arabia/ (accessed on 7 April 2024).

- van den Hoven, M.; Al Qahtani, M. Pathways to Interculturality and the Saudi 2030 Vision. In English as a Medium of Instruction on the Arabian Peninsula; Routledge: London, UK, 2023; pp. 113–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tawfik, T.; Alkhateeb, Y.; Abdalla, M.; Abdalla, Z.; Abdo, S.; Elsayed, M.; Mohammed, E.; Ibrahim, M.; Shihata, G.; Mawad, E. The Economic Empowerment of Saudi Women in the Light of Saudi Vision 2030. Asian Econ. Financ. Rev. 2020, 10, 1269–1279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hameed, I.; Haq, M.A. Book Review: Research, Innovation and Entrepreneurship in Saudi Arabia: Vision 2030. Int. Small Bus. J. Res. Entrep. 2021, 39, 184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, M. E-services and Their Role in B2C E-commerce. Manag. Serv. Qual. An. Int. J. 2002, 12, 434–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Khalidi Al-Maliki, S.Q. Increasing Non-Oil Revenue Potentiality through Digital Commerce: The Case Study in KSA. J. Money Bus. 2021, 1, 65–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albarq, A. The Emergence of Mobile Payment Acceptance in Saudi Arabia: The Role of Reimbursement Condition. J. Islam. Mark. 2024, 15, 1632–1650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alabdan, R.; Sulphey, M.M. Understanding Proximity Mobile Payment Acceptance among Saudi Individuals: An Exploratory Study. Int. J. Adv. Comput. Sci. Appl. 2020, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, A.; Salameh, A.A. Payment and Settlement System in Saudi Arabia: A Multidimensional Study. Banks Bank. Syst. 2023, 18, 38–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, Y.; Shao, X.; Li, X.; Guo, Y.; Nie, K. How Live Streaming Influences Purchase Intentions in Social Commerce: An IT Affordance Perspective. Electron. Commer. Res. Appl. 2019, 37, 100886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, L.M.; Duan, S.; Zhao, Y.; Lü, K.; Chen, S. The Impact of Online Celebrity in Livestreaming E-Commerce on Purchase Intention from the Perspective of Emotional Contagion. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2021, 63, 102733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. The Theory of Planned Behavior. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process 1991, 50, 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. From Intentions to Actions: A Theory of Planned Behavior. In Action Control; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1985; pp. 11–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. Attitudes, Personality and Behaviour; Open University Press: Maidenhead, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Vladimirova, K.; Henninger, C.E.; Alosaimi, S.I.; Brydges, T.; Choopani, H.; Hanlon, M.; Iran, S.; McCormick, H.; Zhou, S. Exploring the Influence of Social Media on Sustainable Fashion Consumption: A Systematic Literature Review and Future Research Agenda. J. Glob. Fash. Mark. 2024, 15, 181–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shafqat, T.; Ishaq, M.I.; Ahmed, A. Fashion Consumption Using Minimalism: Exploring the Relationship of Consumer Well-Being and Social Connectedness. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2023, 71, 103215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Huang, M.; Zheng, S.; Lin, L.; Wang, L. The Impact of Broadcasters on Consumer’s Intention to Follow Livestream Brand Community. Front. Psychol. 2022, 12, 810883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suvittawat, A.; Suvittawat, N. Influential Factors on Clean Food Purchasing Decisions: A Case Study of Consumers in the Lower Northeastern Region of Thailand. World 2024, 5, 683–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Sheng, H.; Mundorf, N.; Redding, C.; Ye, Y. Integrating Norm Activation Model and Theory of Planned Behavior to Understand Sustainable Transport Behavior: Evidence from China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 2017, 14, 1593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhai, M.; Chen, Y. How Do Relational Bonds Affect User Engagement in E-Commerce Livestreaming? The Mediating Role of Trust. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2023, 71, 103239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theodorou, A.; Hatzithomas, L.; Fotiadis, T.; Diamantidis, A.; Gasteratos, A. The Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Online Consumer Behavior: Applying the Theory of Planned Behavior. Sustainability 2023, 15, 2545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, X.; Cheng-Xi Aw, E.; Wei-Han Tan, G.; Ooi, K.-B. Livestreaming as the next Frontier of E-Commerce: A Bibliometric Analysis and Future Research Agenda. Electron. Commer. Res. Appl. 2024, 65, 101390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamalanon, P.; Chen, J.-S.; Le, T.-T.-Y. “Why Do We Buy Green Products?” An Extended Theory of the Planned Behavior Model for Green Product Purchase Behavior. Sustainability 2022, 14, 689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, S.; Kaur, R. Investigating Consumer’s Buying Behaviour of Green Products through the Lenses of Extended Theory of Planned Behaviour. Manag. Environ. Qual. An. Int. J. 2023; ahead-of-print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winston, A.S. Woodworth, R.S. (1869–1962). In Encyclopedia of the Sciences of Learning; Springer US: Boston, MA, USA, 2012; pp. 3461–3463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, C.A. A Broad Approach to Environmental Psychology. Contemp. Psychol. A J. Rev. 1995, 40, 781–782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, G. Stimulus–Organism–Response Model: SORing to New Heights. In Unifying Causality and Psychology; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2016; pp. 699–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Chen, M.; Zamil, A.M.A. Live Stream Marketing and Consumers’ Purchase Intention: An IT Affordance Perspective Using the S-O-R Paradigm. Front. Psychol. 2023, 14, 1069050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bai, K.; Tan, K.H. The Influence of Online Social and Physical Presence on User Consumption Decisions in TikTok Livestreaming: A Scoping Review. Cyberpsychol Behav. Soc. Netw. 2024, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, F.; Huang, X.; Wang, X. Willingness to Pay for Mobile Health Live Streaming during the COVID-19 Pandemic: Integrating TPB with Compatibility. Sustainability 2022, 14, 15932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutuleac, R.; Bargoni, A.; Giachino, C. E-Commerce and Consumer Behaviour: Mapping the Past to Untangle the Present and Inform the Future. Int. J. Electron. Trade 2024, 1, 130–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, R.; Abdul Hamid, A.B.; Ya’akub, N.I. Revisiting Perceived Gratification, Consumer Attitudes and Purchase Impulses in Cross-Border e-Commerce Live Streaming: A Direct and Indirect Effects Model. J. Syst. Inf. Technol. 2024, 26, 51–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iglesias-Pradas, S.; Acquila-Natale, E. The Future of E-Commerce: Overview and Prospects of Multichannel and Omnichannel Retail. J. Theor. Appl. Electron. Commer. Res. 2023, 18, 656–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khoa, B.T.; Huynh, T.T. How Does Anxiety Affect the Relationship between the Customer and the Omnichannel Systems? J. Theor. Appl. Electron. Commer. Res. 2023, 18, 130–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavlou, P.A.; Fygenson, M. Understanding and Predicting Electronic Commerce Adoption: An Extension of the Theory of Planned Behavior. MIS Q. 2006, 30, 115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, G.; Liu, F.; Liu, W.; Liu, S.; Chen, Y.; Xu, D. Effects of Information Quality on Information Adoption on Social Media Review Platforms: Moderating Role of Perceived Risk. Data Sci. Manag. 2021, 1, 13–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosillo-Díaz, E.; Blanco-Encomienda, F.J.; Crespo-Almendros, E. A Cross-Cultural Analysis of Perceived Product Quality, Perceived Risk and Purchase Intention in e-Commerce Platforms. J. Enterp. Inf. Manag. 2019, 33, 139–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Maroof, R.S.; Alhumaid, K.; Alshaafi, A.; Akour, I.; Bettayeb, A.; Alfaisal, R.; Salloum, S.A. A Comparative Analysis of ChatGPT and Google in Educational Settings: Understanding the Influence of Mediators on Learning Platform Adoption; Springer Nature Switzerland: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; pp. 365–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Z.; Han, X.; Zhang, X. Users’ Satisfaction Improvement of Financial Shared Service Platform—Perceived Usefulness Mediation and NGIT Application Maturity Adjustment. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 48960–48974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rishi, B. Motivators and Decisional Influencers of Online Shopping. Int. J. Bus. Innov. Res. 2010, 4, 195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, S.; Zaman, I.; Khan, M.I.; Musleha, Z. Role of Influencers in Digital Marketing: The Moderating Impact of Follower’s Interaction. GMJACS 2022, 12, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horváth, J.; Fedorko, R. The Impact of Influencers on Consumers’ Purchasing Decisions When Shopping Online; Springer Nature Switzerland: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; pp. 216–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, A.; Jaiwant, S.V. Role of Social Media Influencers in Fashion and Clothing; IGI Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2023; pp. 203–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gökerik, M. Consumer Cynicism in Influencer Marketing: An Impact Analysis on Purchase Intention and Brand Loyalty. İnsan Ve Toplum. Bilim. Araştırmaları Derg. 2024, 13, 404–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barta, S.; Belanche, D.; Fernández, A.; Flavián, M. Influencer Marketing on TikTok: The Effectiveness of Humor and Followers’ Hedonic Experience. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2023, 70, 103149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barta, S.; Gurrea, R.; Flavián, C. Telepresence in Live-Stream Shopping: An Experimental Study Comparing Instagram and the Metaverse. Electron. Mark. 2023, 33, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gillham, B. Developing a Questionnaire; Continuum: London, UK, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Denscombe, M. Web-Based Questionnaires and the Mode Effect. Soc. Sci. Comput. Rev. 2006, 24, 246–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernard, R.M.; Brauer, A.; Abrami, P.C.; Surkes, M. The Development of a Questionnaire for Predicting Online Learning Achievement. Distance Educ. 2004, 25, 31–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeVaus, D. Surveys in Social Research; Routledge: London, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Aday, L.A.; Cornelius, L.J. Designing and Conducting Health Surveys: A Comprehensive Guide; Jossey-Bass A: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, W.W.K.; Clark, T.H.K. ONLINE COURSE ACCEPTANCE: A PAIRED SAMPLE EXPERIMENT. In Proceedings of the TechEd Ontario International Conference & Exposition, Oshawa, ON, Canada, 24–26 March 2003; pp. 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Calculator. Sample Size Calculator. Available online: http://www.calculator.net/sample-size-calculator.html (accessed on 1 June 2020).

- Armstrong, J.S.; Overton, T.S. Estimating Nonresponse Bias in Mail Surveys. J. Mark. Res. 1977, 14, 396–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Field, A.P. Discovering Statistics Using IBM SPSS Statistics: And Sex and Drugs and Rock “n” Roll; Sage: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.F.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. PLS-SEM: Indeed a Silver Bullet. J. Mark. Theory Pract. 2011, 19, 139–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rigdon, E.E.; Sarstedt, M.; Ringle, C.M. On Comparing Results from CB-SEM and PLS-SEM: Five Perspectives and Five Recommendations. Mark. ZFP 2017, 39, 4–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Howard, M.C.; Nitzl, C. Assessing Measurement Model Quality in PLS-SEM Using Confirmatory Composite Analysis. J. Bus. Res. 2020, 109, 101–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Comrey, A.L.; Lee, H.B. A First Course in Factor Analysis; Psychology Press: London, UK, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Tinsley, H.E.; Tinsley, D.J. Uses of Factor Analysis in Counseling Psychology Research. J. Couns. Psychol. 1987, 34, 414–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaiser, H.F. An Index of Factorial Simplicity. Psychometrika 1974, 39, 31–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adya, M.; Kaiser, K.M. Early Determinants of Women in the IT Workforce: A Model of Girls’ Career Choices. Inf. Technol. People 2005, 18, 230–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, L.; Bentler, P.M. Cutoff Criteria for Fit Indexes in Covariance Structure Analysis: Conventional Criteria versus New Alternatives. Struct. Equ. Model. 1999, 6, 1–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taber, K.S. The Use of Cronbach’s Alpha When Developing and Reporting Research Instruments in Science Education. Res. Sci. Educ. 2018, 48, 1273–1296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cronbach, L.J. Coefficient Alpha and the Internal Structure of Tests. Psychometrika 1951, 16, 297–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F., Jr.; Matthews, L.M.; Matthews, R.L.; Sarstedt, M. PLS-SEM or CB-SEM: Updated Guidelines on Which Method to Use. Int. J. Multivar. Data Anal. 2017, 1, 107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Lee, J.-Y.; Podsakoff, N.P. Common Method Biases in Behavioral Research: A Critical Review of the Literature and Recommended Remedies. J. Appl. Psychol. 2003, 88, 879–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumgartner, H.; Weijters, B.; Pieters, R. The Biasing Effect of Common Method Variance: Some Clarifications. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2021, 49, 221–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chin, W.W.; Thatcher, J.B.; Wright, R.T. Assessing Common Method Bias: Problems with the ULMC Technique. MIS Q. 2012, 36, 1003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godefroid, M.-E.; Plattfaut, R.; Niehaves, B. How to Measure the Status Quo Bias? A Review of Current Literature. Manag. Rev. Q. 2023, 73, 1667–1711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, S.; Durand, R.M.; Gur-Arie, O. Identification and Analysis of Moderator Variables. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 291–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saunders, D.R. Moderator Variables in Prediction. Educ. Psychol. Meas. 1956, 16, 209–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, A.F.; Rockwood, N.J. Regression-Based Statistical Mediation and Moderation Analysis in Clinical Research: Observations, Recommendations, and Implementation. Behav. Res. Ther. 2017, 98, 39–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, A.F. Partial, Conditional, and Moderated Moderated Mediation: Quantification, Inference, and Interpretation. Commun. Monogr. 2018, 85, 4–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.; Wu, J.; Sun, Y.; Chen, J.; Pu, Y.; Qi, Y. Trust in Human and Virtual Live Streamers: The Role of Integrity and Social Presence. Int. J. Hum. Comput. Interact. 2023, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; He, N.; Miles, I. Live Commerce Platforms: A New Paradigm for E-Commerce Platform Economy. J. Theor. Appl. Electron. Commer. Res. 2023, 18, 959–975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, K.; Lu, J.; Guo, L.; Li, W. The Dynamic Effect of Interactivity on Customer Engagement Behavior through Tie Strength: Evidence from Live Streaming Commerce Platforms. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2021, 56, 102251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, B.; Chen, Z. Live Streaming Commerce and Consumers’ Purchase Intention: An Uncertainty Reduction Perspective. Inf. Manag. 2021, 58, 103509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nisar, Q.A.; Haider, S.; Ali, F.; Gill, S.S.; Waqas, A. The Role of Green HRM on Environmental Performance of Hotels: Mediating Effect of Green Self-Efficacy & Employee Green Behaviors. J. Qual. Assur. Hosp. Tour. 2024, 25, 85–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ong, A.K.S.; German, J.D.; Almario, A.Y.V.; Vistan, J.M.V.; Galang, J.A.P.; Dantis, J.R.; Balboa, E. Consumer Behavior Analysis and Open Innovation on Actual Purchase from Online Live Selling: A Case Study in the Philippines. J. Open Innov. Technol. Mark. Complex. 2024, 10, 100283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abu-AlSondos, I.A.; Alkhwaldi, A.F.; Salhab, H.A.; Shehadeh, M.; Ali, B.J.A. Customer Attitudes towards Online Shopping: A Systematic Review of the Influencing Factors. Int. J. Data Netw. Sci. 2023, 7, 513–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Adwan, A.S.; Al-Debei, M.M.; Dwivedi, Y.K. E-Commerce in High Uncertainty Avoidance Cultures: The Driving Forces of Repurchase and Word-of-Mouth Intentions. Technol. Soc. 2022, 71, 102083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, Z.; Fan, Z.-P.; Sun, F. Live Streaming Sales: Streamer Type Choice and Limited Sales Strategy for a Manufacturer. Electron. Commer. Res. Appl. 2023, 61, 101300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, Z.; Fan, Z.-P.; Sun, F.; Liu, Y. Open the Live Streaming Sales Channel or Not? Analysis of Strategic Decision for a Manufacturer. Ann. Oper. Res. 2023, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macca, L.S.; Shehzad, N.; Kovacova, M.; Santoro, G. Unlocking E-Commerce Potential: Micro and Small Enterprises Strike Back in the Food and Beverage Industry. Eur. J. Innov. Manag. 2024; ahead-of-print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ismail, H.H.; Azab, R.S. The Role of E-Commerce as an Innovative Solutions in the Development of the Saudi Economy. Mark. Manag. Innov. 2023, 14, 255–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olaopa, O.R.; Alsuhaibany, Y.M. Economic Diversification in Saudi Arabia: The Role of Information Communication Technology and e-Commerce in Achieving Vision 2030 and Beyond. Int. J. Technol. Learn. Innov. Dev. 2023, 15, 137–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jula, N.M.; Staicu, G.I.; Moraru, L.C.; Bodislav, D.A. Toward a Sustainable Development of E-Commerce in EU: The Role of Education, Internet Infrastructure, Income, and Economic Freedom on E-Commerce Growth. Sustainability 2024, 16, 3809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Construct/Factor | Item | Factor Loading |

|---|---|---|

| Cost-effectiveness | CE1: By using shopstreaming, one can purchase at lower product prices. | 0.836 |

| CE2: Shopstreaming offers good discounts for immediate purchases. | 0.863 | |

| CE13: With shopstreaming, one wastes less money on ‘bad’ purchases. | 0.869 | |

| CE4: Shopstreaming saves money by not having to visit stores. | 0.939 | |

| Convenience | CV1: Shopstreaming is fast and easy. | 0.927 |

| CV2: I can engage with shopstreaming where and when it suits me. | 0.912 | |

| CV3: Shopstreaming saves me from having to visit multiple stores. | 0.836 | |

| Pleasure | PL1: I enjoy engaging with the host and other buyers. | 0.887 |

| PL2: I enjoy seeing product reviews and demonstrations. | 0.899 | |

| PL3: I enjoy being able to make an immediate purchase. | 0.854 | |

| Intention to purchase | IP1: I intend to purchase demonstrated products during the live stream. | 0.849 |

| IP2: I intend to purchase demonstrated products at a later stage. | 0.889 | |

| IP3: The products demonstrated in shopstreaming sessions are perfect for me. | 0.861 | |

| Streamer’s influence | SI1: I completely trust, and rely on, the information provided by the seller. | 0.801 |

| SI2: I feel happy that I’ve done the right thing when I purchase a product SI3 that the seller recommends. | 0.882 | |

| SI4: Shopstreaming sellers are extremely knowledgeable about the products they sell. | 0.827 | |

| Platform quality | PQ1: Shopstreaming platforms are well designed and easy to use. | 0.869 |

| PQ2: Shopstreaming platforms are fast and reliable. | 0.849 | |

| PQ3: The purchase and payment processes used on shopstreaming platforms are simple. | 0.836 | |

| Attitude | AT1: I like the idea of purchasing from a shopstreaming portal. | 0.863 |

| AT2: I prefer to buy through shopstreaming than by visiting a ‘real’ store. | 0.784 | |

| AT3: Buying through shopstreaming is enjoyable and pleasant. | 0.796 |

| Demographic/Experience Category | Participants % | |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 39 |

| Female | 61 | |

| Education | High School | 16 |

| College Degree or Higher | 41 | |

| Master’s Degree | 26 | |

| PhD Degree | 17 | |

| Age | 18–24 | 41 |

| 25–49 | 37 | |

| 50+ | 22 | |

| Nationalities | Saudi | 58 |

| Non-Saudi | 42 | |

| Language | Arabic | 69 |

| Non-Arabic | 31 | |

| Shopstreaming Experience | <1 | 23 |

| 1–3 | 40 | |

| 3+ | 37 |

| Fit Measure Category | Fit Measure | Result | Recommended Criteria | Meets Criteria? |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Absolute Fit Measures | Chi-Square (χ2/DF) | 2.59 | <3.0 | Yes |

| SRMR | 0.891 | >0.80 | Yes | |

| GFI | 0.961 | >0.90 | Yes | |

| RMSEA | 0.039 | <0.05 | Yes | |

| Parsimonious Fit Measures | PGFI | 0.641 | <0.05 | Yes |

| PNFI | 0.682 | <0.05 | Yes | |

| Incremental Fit Measures | AGFI | 0.922 | >0.90 | Yes |

| IFI | 0.931 | >0.90 | Yes | |

| NFI | 0.943 | >0.90 | Yes | |

| CFI | 0.951 | >0.90 | Yes |

| Construct/Factor | CA | CR | AVE | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cost-effectiveness | 0.82 | 0.85 | 0.75 | 0.87 | ||||||

| Convenience | 0.84 | 0.83 | 0.73 | 0.62 | 0.86 | |||||

| Pleasure | 0.83 | 0.84 | 0.66 | 0.69 | 0.70 | 0.82 | ||||

| Intention to purchase | 0.85 | 0.80 | 0.63 | 0.57 | 0.65 | 0.68 | 0.80 | |||

| Streamer’s influence | 0.87 | 0.79 | 0.65 | 0.58 | 0.69 | 0.62 | 0.57 | 0.81 | ||

| Platform quality | 0.88 | 0.82 | 0.70 | 0.56 | 0.67 | 0.63 | 0.62 | 0.54 | 0.84 | |

| Attitude | 0.85 | 0.76 | 0.73 | 0.67 | 0.73 | 0.50 | 0.62 | 0.66 | 0.56 | 0.86 |

| Proposed Path | Indirect Relationship (with Attitude) | Direct Relationship (without Attitude) | Results | Status of Mediation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Attitude ← perceived benefits | β = 1.608, p value = 0.02 | β = 7.832, p value = 0.001 | Mediation | Partial Mediation |

| Moderator | Construct (s) | β | t-Value | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Platform Quality: Attitude | Perceived Benefit | 0.4289 | 1.4867 | 0.1381 |

| Platform Quality | 0.7754 | 2.7159 | 0.0068 | |

| Interaction Perceived Benefit × Platform Quality | −0.0990 | −1.3617 | 0.1742 | |

| Streamer’s Influence: Intention to Purchase | Attitude | 0.7782 | 3.2922 | 0.0012 |

| Streamer’s Influence | 0.7242 | 3.1754 | 0.0018 | |

| Interaction Attitude × Streamer’s Influence | −0.1632 | −2.7979 | 0.0058 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mutambik, I. The Emerging Phenomenon of Shopstreaming: Gaining a More Nuanced Understanding of the Factors Which Drive It. J. Theor. Appl. Electron. Commer. Res. 2024, 19, 2522-2542. https://doi.org/10.3390/jtaer19030121

Mutambik I. The Emerging Phenomenon of Shopstreaming: Gaining a More Nuanced Understanding of the Factors Which Drive It. Journal of Theoretical and Applied Electronic Commerce Research. 2024; 19(3):2522-2542. https://doi.org/10.3390/jtaer19030121

Chicago/Turabian StyleMutambik, Ibrahim. 2024. "The Emerging Phenomenon of Shopstreaming: Gaining a More Nuanced Understanding of the Factors Which Drive It" Journal of Theoretical and Applied Electronic Commerce Research 19, no. 3: 2522-2542. https://doi.org/10.3390/jtaer19030121

APA StyleMutambik, I. (2024). The Emerging Phenomenon of Shopstreaming: Gaining a More Nuanced Understanding of the Factors Which Drive It. Journal of Theoretical and Applied Electronic Commerce Research, 19(3), 2522-2542. https://doi.org/10.3390/jtaer19030121