Abstract

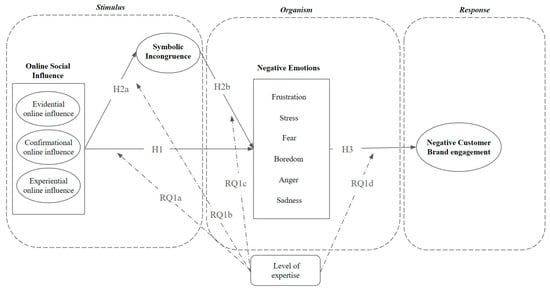

This article draws on the stimulus–organism–response (SOR) model to understand the role of negative emotions in the anti-brand behaviors of online users who consume snow sports brands. To this end, both the online social influence and the mediating effect of symbolic incongruence (stimulus) on the generation of negative emotions (anger, stress, frustration, fear, boredom and sadness) (organism), and how these influence the formation of negative customer brand engagement (nCBE) (response), are analyzed. The study also analyses the moderating effects of “level of expertise”, this makes it possible to capture differences in behaviors based on the profile of the users in each of the proposed relationships. Questionnaire responses of 400 ski and snowboard users over 18 years of age were analyzed using a quantitative methodology. The results obtained have important theoretical and practical implications, since they confirm that online social influences have both a direct and indirect (mediating) effect on negative emotions, which positively affects the nCBE of online users of snow sports brands. Significant differences in behavior based on experience level (moderation effect) were also found. The study proposes useful practical recommendations applicable in online environments that the extreme sports industry could use to neutralize/avoid highly detrimental consequences.

1. Introduction

Emotions have been regarded in the marketing literature as key due to their great implications for consumer behaviors [1,2] and catalytic role in human acts/decisions [2]. Two types are differentiated, positive and negative [2]. Negative emotions, such as anger, fear and stress, have received less scientific attention despite their important implications for consumer behaviors [3,4,5]. These emotions remain longer in consumers’ memories, negatively affecting their relationships with brands [1,6] and, therefore, harming the brands in economic and social terms.

This study examines extreme sports. An investigation is undertaken into the implications of negative emotions felt by ski and snowboard users influenced by comments made by other users on social media. The analysis of this context is of great interest for three reasons: first, the extreme sports sector is experiencing great growth in terms of the number of participants [7,8], with consequent, important social and economic impacts [8]; second, extreme sports followers are considered highly affective due to the physical and mental challenges involved in the activities [9,10] so extending knowledge in terms of the behaviors they exhibit toward brands is of great scientific interest; third, e-commerce involving sports products has grown more than 300% in recent years [11]. There is, thus, a need to understand the attitudes and behaviors of these users in online environments.

Social influences, specifically interpersonal influences, have been widely studied in the literature due to their impact on consumer behaviors [12,13,14,15]. There is significant academic interest in extending the understanding of these influences to other environments, such as social media [14,16,17]. Online environments are useful sources of information for consumers because, in addition to allowing them to make their purchases agilely and quickly (user experience) [16,17], they provide data (e.g., social networks, reviews, websites, forums) posted by other consumers that permits them to know, with greater confidence, things about brands that companies do not transmit on their official channels [11,18,19]. Previous studies, such as by Zhu and Zhang [20], assessed the increase in video game sales based on previous positive ratings. Later, Moe and Trusou [21] indicated that the number of co-commentaries made by reviewers increased if the product rating was negative. Likewise, Sridhar and Srinivasan [22] proved that the influence of leaders’ opinions directly influenced the rating of the products based on the valence of the opinions. Consumers’ online experiences, and the information they obtain online, can influence their emotions [19,23,24] through emotional contagion [13], which can ultimately affect how they behave toward brands.

The present study aims to achieve the following four main objectives: (1) to analyze the effects of online social influence on negative emotions (stress, frustration, fear, anger, sadness and boredom); (2) to analyze the mediating role of symbolic incongruence between online social influence and negative emotions; (3) to understand the effect of negative emotions on the generation of negative brand customer engagement; and (4) to assess whether the experience level of extreme sports users has a moderating effect on negative brand behaviors in online environments.

These analyses make six important contributions to the literature: First, the understanding of emotional contagion theory is expanded by assessing the role of negative emotions (frustration, stress, fear, boredom, anger and sadness) on consumer behaviors [4]. Second, knowledge of the concept of social influences and their effects on extreme sports users in a digital environment is extended [16,25]. Third, the mediating role of symbolic incongruence is evaluated, extending knowledge of reference group theory [26] and self-congruence theory [27]. Fourth, a further exploration of negative customer brand engagement, one of the main negative reactions to brands in online environments, is undertaken [28,29,30,31]. Fifth, the moderating effects of the level of expertise on the proposed relationships is assessed, thus extending understanding of moderating effects on negative brand–consumer relationships [32]. Sixth, the results of the study can help the extreme sports industry understand the affective role of negative emotions felt by their target audience and to develop strategies to address the negative effects of online social influence [33].

2. Literature Review

2.1. Stimulus–Organism–Response (SOR) Model

The SOR model [34] was developed in the psychological domain; it is widely used to explain complex consumer behaviors based on the influence of social interactions [35]. The SOR model has been particularly used in the digital domain [36,37,38,39]. Its use has essentially been based on how external stimuli (S) create an emotional or cognitive state in the consumer (O) that generates responses that directly affect consumer behaviors (R) [36,37,40].

The present study is among the few to utilize the SOR model through a negative prism [37]. In the framework of the model, both online social influence and symbolic incongruence (S) are stimuli that induce negative emotional states in ski and snowboard users (O). These states, in turn, generate negative customer brand engagement response (R) behaviors toward ski/snowboard brands. The proposed model is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Research model. Source: own design.

2.2. Organism: Negative Emotions

The study of negative emotions has intensified in recent years following important contributions from Mehrabian and Russell [34], Plutchik [41] and Lazarus [42]. Nonetheless, there is a need to expand knowledge about them due to their complexity [43,44] and because of their important implications for consumer behaviors [2,44].

Negative emotions are strongly linked to individuals’ organic appraisals of their environment [43,45]. It is commonly accepted that negative emotions are evoked in consumers when they perceive/experience unpleasant situations [2,43], and that these emotions can trigger consumer behaviors that can significantly damage brands [46]. Among the most brand-damaging behaviors are brand avoidance [47], negative word of mouth [48], brand switching [49] and negative engagement [50].

Investigations into the negative emotions evoked in consumers in digital environments (e.g., consumer reviews, online communities, websites or social networks) [19,23,43,50,51] have found that emotions do not only arise from subjective perceptions. Negative emotions have a social component motivated by social interactions; that is, the individual can feel other people’s emotions, even without being aware they are doing so [13].

The present study draws on emotional contagion theory [52] to explain the relationship between online social influences and negative emotions. The theory, which has been adapted to online environments [13], explains how consumers can be emotionally influenced by other people through the attitudes they express [13,52].

Responding to calls for a deeper understanding of negative emotions in digital environments [43], this study examines the emotions frustration, stress, fear, boredom, anger and sadness. This examination takes place because: (i) stress, fear, anger and sadness [2,19,53] are emotions with a large representation in the analysis of emotions in online environments; (ii) frustration, fear, anger and sadness are emotions strongly implicated in the anti-brand behaviors exhibited by consumers [31,43,54]; and (iii) previous studies have shown that frustration, stress, boredom, sadness and fear are among the most common emotions felt by extreme sports users [7,9,55,56,57].

2.3. Stimulus

2.3.1. Online Social Influence

The relevant literature [15,58,59] suggests that social influences make the individual conform, in terms of behaviors, attitudes and beliefs, with other members of social groups. Two types of social influence are recognized in the literature, depending on setting [15,59]. Offline social influence [12] occurs when influence is exerted through social interactions in a physical environment. It is manifested when the individual seeks approval from a social group (normative) or when they consult people they consider to be referents, such as friends, relatives or people considered experts (informational). Online social influence [16,60] is manifested when the influence is exerted through an interaction between the individual and digital information sources. Among these are reviews, the opinions of influencers and online communities and the experiential navigation of websites, chatbots, blogs and discussion forums. Online social influence has been said to have three dimensions [16], evidential, confirmational and experiential. The first two dimensions measure the quantity and quality of opinions generated in online environments about products and brands. Experiential online influence is related to past online experiences that influence users’ decision-making.

Given the high involvement of social influences in consumer behaviors [15,16], particularly in online environments [61,62], the present study seeks to expand knowledge about the effects that these influences can exert on consumers’ emotional states. Ruiz-Mafé et al. [63] analyzed these relationships, confirming that social influence significantly impacted on consumers’ positive emotions. In turn, these emotions were shown to directly affect brand loyalty. Meng et al. [13] confirmed that social influences affected positive emotions in an online environment, specifically focusing on the influence produced by online celebrities. In the same line, but from a negative valence, Joshi and Yadav [64] were pioneers in confirming the effect of social influence on negative emotions, specifically on brand hate. This study aims to expand the knowledge of social influences on emotions from an innovative perspective by analyzing online social influence [16] and its impact on negative emotions (frustration, stress, fear, boredom, anger and sadness) in skiing and snowboarding users. To explain this relationship the study draws on emotional contagion theory [52], which suggests that social influences impact on individuals’ emotional states and behaviors. Meng et al. [13] and Ozuem et al. [60], examining influencers, found that social influences positively affected emotions in an online context. Therefore, in this study, the following hypothesis is proposed:

H1.

Online social influence positively impacts on the negative emotions users feel toward skiing and snowboarding brands.

2.3.2. Symbolic Incongruence as a Mediator between Online Social Influence and Negative Emotions

Bearden et al. [12] (p. 474) argued that social influence reflects “the need to identify or enhance one’s own image before significant others through the acquisition and use of products and brands, the willingness to confirm others’ expectations regarding purchase decisions, and/or the tendency to learn about products and services by observing others and/or seeking information from others.” In this definition, the component of self-expression is very important; this is even more accentuated when the brand is visible (e.g., clothing) to other people [15].

Ski and snowboard users are considered to be a very specific profile, both because of the highly emotional states they can endure [9,10] and because they are characterized by their motivation to want to be part of social groups that they regard as having the advanced knowledge and sophistication they aspire to [8,9]. This motivation, to be part of these social groups, possibly has utilitarian/functional and symbolic drivers, related to the sportsperson’s self-concept [8,15]. The present study draws on group reference theory [26] to explain the relationships proposed in the model between online social influence and symbolic incongruence. Group reference theory suggests that people’s behaviors and attitudes can be altered based on reference groups, which can even influence their values and group norms [16].

Similarly, individuals can be linked to different social groups based not only on the brands they consume, but also on those they do not consume. This is because they do not identify with them [65,66], a form of self-expression [66]. When a brand´s personality or image does not match the consumer’s personality, symbolic incongruence arises [47,67]. This incongruence can elicit negative emotions in the individual, culminating in anti-brand behaviors [47,65,68]. To explain the relationship between symbolic incongruence and negative emotions, the study draws on self-congruence theory [27]. Self-congruence theory proposes that individuals seek fit in their cognitions (e.g., values or beliefs) as mismatches generate incoherence that can provoke negative emotional states. The theory is applied to analyze the fit relationship between consumer self-concept and brand image; this analysis has indicated that this relationship directly affects consumer behaviors [27,69].

Therefore, the present study examines the mediating effect of symbolic incongruence to test whether the symbolic or self-expressive component in ski and snowboard users should be taken into account in the generation of the negative emotions they express toward brands. Therefore, the following hypotheses are proposed:

H2.

Symbolic incongruence has a mediating effect on online social influence and negative emotions; that is:

H2a.

Online social influence has a positive impact on symbolic incongruence.

H2b.

Symbolic incongruence has a positive impact on negative emotions.

2.4. Response

Negative Customer Brand Engagement

Engagement, because it is regarded as being of great importance in digital environments and can positively and negatively impact brands, has attracted great interest in the consumer behavior literature [68,70,71]. Previous studies have shown that emotions play a predictive role in consumer engagement [43,50,68,70,72], showing that the valence of emotions can directly influence the valence of the engagement itself [50].

Customer brand engagement was defined by Hollebeek [73] (p. 565) as “the level of a customer’s cognitive, emotional and behavioral investment in specific brand interaction”. Later, Juric et al. [74] (p. 285) defined it, looking at negative valence, as “a series of mental states and an iterative psychological process, which is catalyzed by perceived threats (or a perceived or reconstructed threat) to oneself”.

The present study considers negative customer brand engagement to be the main reaction by consumers toward brands in an online environment. This is because it represents one of the most active anti-brand behaviors that consumers can develop [73,74,75] and can affect them negatively at the level of prestige and affinity, and economically [74]. To explain the relationship (described in the model) between negative emotions and negative customer brand engagement, this study draws on engagement theory [76]. Engagement theory proposes that the affective state of the individual, generated by his/her relationship with the brand, will cause him/her to engage in customer engagement behaviors toward brands. Therefore, taking the negative perspective, if the individual’s affective state is negative, they will exhibit negative customer engagement behaviors toward the brand. Therefore, we propose the following hypothesis:

H3.

Negative emotions positively influence the generation, in online contexts, of negative customer brand engagement in ski/snowboard users.

2.5. The Effects of Level of Expertise as a Situational Moderator

The expertise concept is understood as a cognitive competence [77]. In the present study, two groups are differentiated based on their level of competence, experts and novices [77]. Experts are individuals who stand out for their knowledge about a domain or, in the case of this study, about a brand [78]. They are more efficient than individuals considered novices [77], who are differentiated by their reduced control in the domain, based on their lack of knowledge and/or on their lack of motivation or enthusiasm to improve their skills [57,77].

Despite its important implications for consumer decision-making, studies into the effects of expertise as a moderator are very scarce [77,78]. Thus, in this study, one aim is to expand knowledge about this phenomenon in the context of negative brand-consumer relationships [32]. Evanschitzky and Wunderlich [79] argued that the consumer´s level of expertise has the capacity to alter his/her consumption behaviors due to his/her experience of, and cognitive reasoning related to, the brand. In the context of extreme sports, Pikkemaat et al. [80] found that the expertise effect is highly important in ski and snowboard users as it influences them in their decisions to travel to one ski resort or another. Similarly, Woodman et al. [81] and Monasterio et al. [57] argued that the emotional involvement of experts and novices can differ. For example, an expert user may interpret fear as “necessary” when they practice an extreme sport, giving it a positive valence, despite the emotion being negative in nature [82].

As to the relationships proposed in the present study, Fernandes et al. [16] and Racherla et al. [83] argued that, in online environments, novice consumers are more influenced than are experts, when making a purchase decision, by the quantity and valence of reviews about brands (RQ1a). Similarly, novice users are more influenced by symbolic aspects than by functional aspects [78] because they want to link their self-image with groups they perceive to be sophisticated (reference group theory) (RQ1b and RQ1c). In addition, Mirehie and Gibson [9] found that expertise level directly influenced snowboard users’ engagement with the sport. Yildiz-Durak et al. [84] found the user’s level of expertise had a positive influence on their engagement with videos in online environments (RQ1d). Therefore, in this study it is proposed that level of expertise can have important moderating effects on the relationships described in the model. Thus, the following research questions are posed:

RQ1a.

Does the ski and snowboard user´s level of expertise moderate the relationship between online social influence and negative emotions?

RQ1b.

Does the ski and snowboard user´s level of expertise moderate the relationship between online social influence and symbolic incongruence?

RQ1c.

Does the ski and snowboard user´s level of expertise moderate the relationship between symbolic incongruence and negative emotions?

RQ1d.

Does the ski and snowboard user´s level of expertise moderate the relationship between negative emotions and the generation of negative customer brand engagement?

3. Methodology

A quantitative methodology was used, with structural equation modeling (SEM), to address the hypotheses/questions. A digital, structured questionnaire, based on the Google Form tool, attracted 400 responses from Spain-based ski and snowboard users over 18 years of age during the summer and fall of 2023. A non-probabilistic convenience sampling method (“snowballing”) was used because it offers great ease of access and/distribution to individuals with similar characteristics [17]; in this case, ski and snowboard users. A pre-test (n = 10) was performed with ski/snowboard users to detect any problems in the questionnaire. Adjustments were subsequently made to ensure the scales were understandable.

As to the sample’s demographic characteristics, 62% were men and 38% women; 40.9% were aged between 18 and 30 years, 44.4% were aged between 31 and 45 years, 13.7% were aged between 46 and 64 years and 1.7% were over 65 years of age; 80% of the sample said they were working, 12% were students, 5.2% were unemployed and 2.5% were retired. As to their levels of experience in the sports, two main groups are distinguished: “Experts”, with more than 10 years of experience in skiing and/or snowboarding (63%); and “Novices”, with less than 10 years of experience in skiing and/or snowboarding (37%). Table 1 presents the data.

Table 1.

Sample statistics (N = 400).

The questionnaire used 32 items (4 variables), measured on 5-point Likert scales, with 1 being “totally disagree” and 5 “totally agree”. Online social influence, a scale extracted from Fernandes et al. [16], was the only variable considered in the present model as formative second-order. It is composed of the dimensions of evidential online influence (5 items), confirmational online influence (3 items) and experiential online influence (3 items). The remaining variables, considered as first-order reflective factors, are: symbolic incongruence (5 items), measured using the scale developed by Hegner et al. [47]; negative emotions (frustration, stress, fear, boredom, anger and sadness) were measured using a single item, following Ruiz-Mafé et al. [63] and Haj-Salem and Chebat [46]; NCBE (10 items) was measured using the scale developed by Hollebeek et al. [85]. All the items were slightly adapted to match the study context. A detailed description of the items used in the study can be seen in Table 2.

Table 2.

Measurement scales. Reliability and convergent validity.

3.1. Data Analysis and Results

Two main tools were used to examine the theoretical causal relationships in the model. First, RStudio was used to evaluate the model’s fit indexes. Second, SmartPLS (version 4.1.03) was used to evaluate the indicators and variables proposed in the model and the relationships between the variables that allow acceptance or rejection of the hypotheses.

First, the fit indexes were analyzed through a confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) to ensure that the model had no fit problems. For this, the following indexes were used: (i) χ2 = 1639, df = 561, p < 0.001, χ2/df = 2.9; (Tucker–Lewis index) TLI = 0.944; (comparative fit index) CFI = 0.957; (root mean square error of approximation) RMSEA = 0.078; (standardized root mean square residual) SRMR = 0.071; (goodness-of-fit index) GFI = 0.958. Therefore, following the recommendations of Kline [86] and Hair et al. [87], it can be stated that the model has good fit.

Second, the reliability and convergent validity of all the factors were tested using Cronbach’s alpha (α), composite reliability (CR) and average variance extracted (AVE); the values were all within acceptable parameters [87] (see Table 2). Two items had to be eliminated from the negative customer brand engagement variable due to low loadings and convergent validity issues (AVE > 0.5) [87]. Similarly, the above metrics did not analyze the online social influence construct, given that it is formative [88].

The third step was to evaluate discriminant validity through the Fornell–Larcker criterion (see Table 3). This requires that all AVE values be greater than their inter-construct correlations [89]. This step is essential to verify that a variable is empirically different from other estimated variables in the proposed model [87].

Table 3.

Discriminant validity. Square correlation matrix of latent variables.

The hypotheses were all tested and accepted (see Table 4). Online social influence was found to positively influence negative emotions (beta = 0.236 ***; t-Stat = 5.162). The relationship between online social influence and symbolic incongruence was supported (beta = 0.256 ***; t-Stat = 5.010), thus, H2a is accepted. Similarly, H2b was also accepted as symbolic incongruence had a positive influence on negative emotions (beta = 0.460 ***; t-Stat = 11.114). Negative emotions were found to have a positive influence on negative customer brand engagement (beta = 0.468 ***; t-Stat = 12.281), so H3 is accepted.

Table 4.

Tests of the hypotheses.

3.2. Mediation Analysis

To estimate the mediating effects of symbolic incongruence between online social influence and negative emotions (H2), we followed Hair et al. [87]. First, the indirect effect between online social influence and negative emotions through symbolic incongruence was found to be significant. Second, the direct effect between online social influence and negative emotions was also found to be significant. Finally, the direction of the relationships was found to be all positive, and the VAF (variance accounted for) value was found to be 34% [90]. This suggests there is complementary partial mediation [87,91]. Therefore, H2 is supported (see Table 5).

Table 5.

Mediation analysis.

3.3. Multigroup Analysis: Moderation of Level of Expertise

To identify any differences in the relationships proposed in the model between the “high-expertise” (>10 years of experience in snowboard/ski) and “low-expertise” (<10 years of experience in snowboarding/skiing) groups, a bootstrap-based multigroup analysis (PLS-MGA) was undertaken; this also sought to answer the research questions posed above. Table 6 confirms the reliability, validity and discriminant validity of the “high-expertise” and “low-expertise” groups. Table 7 shows that all the relationships proposed in the model are significantly positive for both groups. In addition, this table shows the results of the multigroup analysis; the following conclusions are highlighted:

Table 6.

Reliability, validity, correlations and the square roots of AVEs (high expertise vs. low expertise).

Table 7.

Multigroup analysis.

There is no significant difference between the groups (high vs. low) in the relationship between online social influence and negative emotions (diff = −0.139; p = 0.138) (RQ1a).

There is a significant difference between the groups (high vs. low) in the relationship between online social influence and symbolic incongruence (diff = −0.198; p = 0.059) (RQ1b).

There is no significant difference between the groups (high vs. low) in the relationship between symbolic incongruence and negative emotions (diff = 0.066; p = 0.430) (RQ1c).

A significant difference was found between the groups (high vs. low) in the relationship between negative emotions and negative customer brand engagement (diff = −0.137; p = 0.087) (RQ1d).

4. Discussion and Conclusions

The present study contributes to the consumer behavior literature by providing further insights into the negative relationships established between brands and consumers in an online environment. The SOR model was used to explain the structure and global relationships of the model, confirming its good fit in online environments, in line with previous studies [36,37,38,39]. Furthermore, it was shown that online social influence and symbolic incongruence are the key stimuli (S) in the generation of the emotions frustration, stress, fear, boredom, anger and sadness, as negative organic responses (O) that create, in online contexts, negative customer brand engagement in ski and snowboard users (R).

It was shown that online social influence is a determining factor in negative brand-consumer relationships; that is, it has a positive effect on the generation of negative emotions in ski and snowboard users. These results are supported by emotional contagion theory [52] and by the results of Joshi and Yadav [64], and reaffirm that online social influence underlies negative consumer behaviors toward brands. Going deeper into the online social influence construct, the experiential online influence dimension (beta = 0.979; p < 0.01) was seen to be more important than evidential online influence (beta = 0.848; p < 0.01) and confirmational online influence (beta = 0.850; p ≤ 0.01), indicating that the influence of the user’s browsing experience is more determinant in ski/snowboard users in terms of generating negative responses. These results are consistent with the results obtained by Ozuem et al. [60], who concluded that negative interactions with digital technical elements (e.g., chatbot failures, ambiguous websites) related to brands generate negative experiences that evoke intense negative emotions toward the brands.

As to mediation, it was shown that symbolic incongruence had a mediating effect between online social influence and negative emotions, by confirming a complementary partial mediation; that is, 34% (VAF) of the relationship between online social influence and negative emotions is explained by symbolic incongruence. This contribution is of great scientific interest because the relationship between online social influence and symbolic incongruence had not, until now, been directly examined. It was shown that ski/snowboard users disassociate themselves from brands to improve their self-concept, which allows them to feel more acceptable to their reference groups. This conclusion is supported by both reference group theory [26] and self-congruence theory [27], confirming the singular profile of ski/snowboard users [9,10] and their attraction to the symbolic value of brands [15], which directly affects negative emotional attitudes felt toward brands [47,67].

The knowledge of negative emotions (frustration, stress, fear, boredom, anger and sadness) is expanded in terms of their significant impact on ski and snowboard users in digital environments [19,23,43]. Stress stands out from the other emotions, which is in line with previous studies [57,92] which examined online environments, in that it is a key factor in generating negative engagement.

The main negative reaction identified in the model, negative customer brand engagement, was seen to be influenced by negative emotions. This result is consistent with engagement theory [76] from a negative perspective, and with the results of previous studies that argued that emotions are antecedents of negative engagement in digital environments [31,50,72].

Finally, the answers to the research questions expand the knowledge of the moderating effect of level of expertise on consumer behaviors [77,78,79,80], and confirm that it is a variable that brands should consider when developing their affinity strategies and approaches to users in online environments. Similarly, the singular profile of the ski and snowboard user [10,57] was examined, and it was confirmed that this profile can alter decision-making processes regarding the consumption of, and affinity for, a brand.

Therefore, the results of the study showed two significant differences from the relationships proposed in the model. First, in line with Sohail and Awal [78], Burke et al. [93] and reference group theory [26], it was confirmed that level of expertise has a moderating effect on the relationship between online social influence and symbolic incongruence; that is, online social influence has a significantly greater impact on symbolic incongruence for the “low-expertise” group due to their the lack of knowledge of the field. This lack makes novices more susceptible to the recommendations of groups they consider references and increases their motivation to belong to “experts” groups, which would help them improve their level of skill and their self-image. Second, in line with Mireie and Gibson [9], Burke et al. [93] and Yildiz-Durak et al. [84], an important difference was found between negative emotions and negative customer brand engagement; that is, the group considered “low-expertise” was more affected by this relationship than was the “high-expertise” group; this is because “novices” have a lower “locus of control”; that is, they are more impulsive on an emotional level.

5. Implications

5.1. Theoretical Implications

The present study offers interesting contributions to the consumer behavior literature. Specifically, it examines, in depth, the negative role of social influences exerted by online information sources on the emotional state of ski/snowboard users; that is, they evoke negative behaviors toward brands. This theoretical approach is supported by the SOR model which, despite its important implications for consumer behaviors [3,4,30], has rarely been examined in the literature from a negative perspective in online environments [37,67].

At the level of social influence, to the best of the authors´ knowledge, this study may be the first to apply the construct proposed by Fernandes et al. [16], which brings together, in a single variable, the most important factors that can influence users in online environments. In addition, this study is one of the few [60,64] to examine the social influences on consumers’ negative emotions as a predictor of their negative behaviors toward brands. In doing so, it confirms the good fit of emotional contagion theory in this relationship. This result is consistent with the findings of Joshi and Yadav [64], who found that past experience strongly influenced e-WOM behaviors; that is, active anti-brand behaviors in online environments. Another important contribution is the finding about the mediation of symbolic incongruence between online social influence and negative emotions; this confirms that social influences can create negative emotional states, in the consumer, that can affect brands. This is supported by both reference group theory [26] and self-congruence theory [27].

In addition, the negative emotions analyzed in the present study contribute to a broader understanding [4,43,94] of frustration, stress, fear, boredom, anger and sadness and their effects on ski/snowboard users in an online environment. The results confirm their involvement in negative consumer effects, with the emotion of stress being the most important of the six emotions assessed, in line with other studies such as Siu et al. [92] and Monasterio et al. [57] or Iranzo-Barreira et al. [94].

Regarding the main reaction identified in this study, negative customer brand engagement is postulated to be a negative response in online environments, which is predicted by the emotions frustration, stress, fear, anger and sadness [28,50,72,89,92] (boredom is a complementary emotion that should also be taken into account). Thus, the study results support engagement theory [76]. In addition, this relationship confirms that ski/snowboard users, negatively influenced by online information sources, act against brands by posting negative comments, reviews or reactions [38,64]. This represents a high economic and reputational risk for companies.

Finally, an important contribution relates to the results obtained for the moderating effects of level of expertise: (i) knowledge of the moderating effects of expertise on consumer behaviors is extended [32], confirming that the consumer´s profile alters his/her attitudes and behaviors toward brands; (ii) there is no moderating influence between online social influence and symbolic incongruence and negative emotions; (iii) the “low-expertise” group is more influenced by online social influences and their emotional states are more predictive of negative customer brand engagement behaviors.

5.2. Managerial Implications

This study makes important recommendations for the extreme sports industry that should be considered in the design of their online environment strategies.

Brands should seek to neutralize the stimuli that produce, in their consumers, bad experiences and negative perceptions, due to the social influences present in online environments. It is essential that brands consider the browsing experience of users as they explore websites and social networks. Their websites and mobile apps should have a clear design and appear congruent with their consumers’ symbolic values. In terms of web experience, it is recommended that the consumer´s product search can be performed with as few clicks as possible, and that they can obtain all the product information they want in a clear, reliable and uninterrupted manner. Similarly, in terms of symbolic value, brands should seek to emphasize the values that increase their customers’ self-concepts, especially for those with little experience in sports. This will mean avoiding sponsorships that may conflict with their values (e.g., if the brand identifies with environmental values). If the brand identifies with environmental values, it should associate itself with companies with strong environmental positioning, try to use elements in online environments (e.g., websites/social networks) that help the consumer feel identified with the brand (e.g., use professional and creative language and high-quality images/videos) and carry out corporate actions that show affinity with the target audience (e.g., arrange free meetings with elite skiing and snowboarding athletes).

In addition, the study demonstrates the importance of negative emotions in generating negative customer brand engagement. For this reason, it is essential that brands invest in detailed, regular monitoring of the main negative emotions that are expressed in information sources, using specialized software. It is recommended that brands use this information to contact, in a personalized way, those users who have expressed the most damaging emotions (especially stress and anger) and seek to alleviate their affective dissatisfaction. The study results suggest that brands should place more importance on those users considered “newbies”, given that they are more susceptible to negative emotions and, therefore, will have a greater predisposition to act against the brand.

Another recommendation is that brands should stimulate positive comments in the sources of information that express most opposition to the brand. This may have a contagion effect. To this end, they might carry out promotional activities that encourage engagement, for example, by giving gifts to the brand’s most loyal customers in exchange for reviews or reactions to the brand. It is important that company managers undertake actions to stimulate positive engagement in an organic way, to ensure that users will not see their promotions as artificial, which would generate distrust and boost negative emotions against the brand.

6. Limitations and Future Lines of Research

This study has some limitations that open avenues for future research. A convenience sample was used, so the results should not be generalized. It would be interesting, in future studies, to apply an experimental methodology to compare online versus offline influence. The study considered only level of expertise as a moderator. It would be interesting to consider other moderators, such as age, gender and economic level, and to examine a third group in the multigroup analysis (e.g., (a) no experience, (b) beginner experience, (c) advanced experience). The study focused exclusively on the sports sector, so it would be interesting to extend the approach to other contexts, to contrast its conclusions (e.g., gastronomy, tourist destinations, fashion). The work considered only symbolic incongruence as a mediator in the model, so an interesting future line of research would be to include functional incongruence to assess which of the two aspects is more important for online consumers in their anti-brand actions. Although the work examines important negative emotions, its scope could be broadened; thus, future studies might include intense emotions, such as shame and hate, in their models, to explore their implications for consumer behaviors in online environments. Finally, future studies could explore new influences on consumers; for example, it would be interesting to examine the influence of AI on the emotions of online users, both from a positive and negative perspective.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Á.I.-B., I.K. and C.R.-M.; methodology, Á.I.-B., I.K. and C.R.-M.; validation, I.K. and C.R.-M.; formal analysis, Á.I.-B.; data curation, Á.I.-B.; writing—original draft preparation, Á.I.-B.; writing—review and editing, I.K. and C.R.-M.; supervision, I.K. and C.R.-M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Spanish Ministry of Science and Innovation (ID grant number: PID2019-111195RB-I00/AEI/10.13039/501100011033 0).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Review Board (Ethics Committee) of the University of Valencia.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The dataset supporting this study’s findings is available from the corresponding author on request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Kumar, A.; Shankar, A.; Tiwari, A.K.; Hong, H.J. Understanding dark side of online community engagement: An innovation resistance theory perspective. Inf. Syst. E-Bus. Manag. 2023, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khatoon, S.; Rehman, V. Negative emotions in consumer brand relationship: A review and future research agenda. International J. Consum. Stud. 2021, 45, 719–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curina, I.; Francioni, B.; Hegner, S.M.; Cioppi, M. Brand hate and non-repurchase intention: A service context perspective in a cross-channel setting. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2020, 54, 102031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahimah, A.; Dang, H.P.; Nguyen, T.T.; Cheng, J.M.; Kusumawati, A. The subsequent effects of negative emotions: From brand hate to anti-brand consumption behavior under moderating mechanisms. J. Prod. Brand Manag. 2023, 32, 618–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, A.; Chakrabarti, S. Brand hate: A systematic literature review and future research agenda. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2022, 46, 1992–2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, F.; Guzmán, F. Negative online reviews, brand equity and emotional contagion. Eur. J. Mark. 2021, 55, 2825–2870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brymer, E.; Feletti, F.; Monasterio, E.; Schweitzer, R. Understanding extreme sports: A psychological perspective. Front. Psychol. 2020, 10, 3029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raggiotto, F.; Scarpi, D.; Mason, M.C. Faster! More! Better! Drivers of upgrading among participants in extreme sports events. J. Bus. Res. 2019, 102, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirehie, M.; Gibson, H.J. Women’s participation in snow-sports and sense of well-being: A positive psychology approach. J. Leis. Res. 2020, 51, 397–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raggiotto, F.; Scarpi, D.; Moretti, A. Advertising on the edge: Appeal effectiveness when advertising in extreme sports. Int. J. Advert. 2020, 39, 655–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, A.S.; Heo, Y.; Choi, J.W.; Pedersen, Z.P.; Byon, K.K. Online consumer reviews of a sport product: An alternative path to understanding brand associations. Sport Bus. Manag. Int. J. 2023, 13, 530–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bearden, W.O.; Netemeyer, R.G.; Teel, J.E. Measurement of consumer susceptibility to interpersonal influence. J. Consum. Res. 1989, 15, 473–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, L.M.; Duan, S.; Zhao, Y.; Lü, K.; Chen, S. The impact of online celebrity in livestreaming E-commerce on purchase intention from the perspective of emotional contagion. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2021, 63, 102733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajput, A.; Gandhi, A. The branding power of social media influencers: An interactive marketing approach. Cogent Bus. Manag. 2024, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruane, L.; Wallace, E. Brand tribalism and self-expressive brands: Social influences and brand outcomes. J. Prod. Brand Manag. 2015, 24, 333–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, S.; Venkatesh, V.G.; Panda, R.; Shi, Y. Measurement of factors influencing online shopper buying decisions: A scale development and validation. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2021, 59, 102394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haro-Sosa, G.; Moliner-Velázquez, B.; Gil-Saura, I.; Fuentes-Blasco, M. Motivations toward Electronic Word-of-Mouth Sending Behavior Regarding Restaurant Experiences in the Millennial Generation. J. Theor. Appl. Electron. Commer. Res. 2024, 19, 993–1012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konur, D. Keep your enemy close? Competitive online brands’ expansion with individual and shared showrooms. Omega 2021, 99, 102206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pezoa-Fuentes, C.; García-Rivera, D.; Matamoros-Rojas, S. Sentiment and emotion on twitter: The case of the global consumer electronics industry. J. Theor. Appl. Electron. Commer. Res. 2023, 18, 765–776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, F.; Zhang, X. Impact of online consumer reviews on sales: The moderating role of product and consumer characteristics. J. Mark. 2010, 74, 133–148. Available online: https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1509/jm.74.2.133 (accessed on 12 May 2024). [CrossRef]

- Moe, W.W.; Trusov, M. The value of social dynamics in online product ratings forums. J. Mark. Res. 2011, 48, 444–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sridhar, S.; Srinivasan, R. Social influence effects in online product ratings. J. Mark. 2012, 76, 70–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Odoom, R.; Kosiba, J.P.B.; Odoom, P.T. Brand hate experiences and the role of social media influencers in altering consumer emotions. J. Brand Manag. 2024, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vishkin, A.; Tamir, M. Emotion norms are unique. Affect. Sci. 2023, 4, 453–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mazzoli, V.; Donvito, R.; Zarantonello, L. Brand transgressions in advertising related to diversity, equity and inclusion: Implications for consumer–brand relationships. J. Prod. Brand Manag. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richer, S. Reference-group theory and ability grouping: A convergence of sociological theory and educational research. Sociol. Educ. 1976, 49, 65–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sirgy, M.J. Self-Congruity: Toward a Theory of Personality and Cybernetics; Praeger Publishers: Greenwood, IN, USA, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Do, D.K.X.; Rahman, K.; Robinson, L.J. Determinants of negative customer engagement behaviours. J. Serv. Mark. 2020, 34, 117–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naumann, K.; Bowden, J.; Gabbott, M. Expanding customer engagement: The role of negative engagement, dual valences and contexts. Eur. J. Mark. 2020, 54, 1469–1499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, R.; Sangroya, D.; Pereira, V. Why consumers turn negative about the brand: Antecedents and consequences of negative consumer engagement in virtual communities. Inf. Syst. E-Bus. Manag. 2023, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zang, L.; Liu, Y.; Sun, X.; Wen, D. Understanding the formation process of negative customer engagement behaviours: A quantitative and qualitative interpretation. Total Qual. Manag. Bus. Excell. 2024, 35, 170–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aziz, R.; Rahman, Z. Brand hate: A literature review and future research agenda. Eur. J. Mark. 2022, 56, 2014–2051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akdim, K. The influence of eWOM. Analyzing its characteristics and consequences, and future research lines. Span. J. Mark.-ESIC 2021, 25, 239–259. [Google Scholar]

- Mehrabian, A.; Russell, J.A. An Approach to Environmental Psychology; The MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1974. [Google Scholar]

- Islam, T.; Sheikh, Z.; Hameed, Z.; Khan, I.U.; Azam, R.I. Social comparison, materialism, and compulsive buying based on stimulus-response-model: A comparative study among adolescents and young adults. Young Consum. 2018, 19, 19–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, J.; Li, Y.; Xu, Y.; Zeng, K. How live streaming features impact consumers’ purchase intention in the context of cross-border E-commerce? A research based on SOR theory. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 767876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jabeen, F.; Kaur, P.; Talwar, S.; Malodia, S.; Dhir, A. I love you, but you let me down! How hate and retaliation damage customer-brand relationship. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2022, 174, 121183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandliya, A.; Pandey, J.; Hassan, Y.; Behl, A.; Alessio, I. Negative brand news, social media, and the propensity to doomscrolling measuring and validating a new scale. Int. Stud. Manag. Organ. 2024, 54, 137–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, B.; Kowatthanakul, S.; Satanasavapak, P. Generation Y consumer online repurchase intention in Bangkok: Based on Stimulus-Organism-Response (SOR) model. International J. Retail Distrib. Manag. 2020, 48, 53–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buxbaum, O. The SOR-Model in Key Insights into Basic Mechanisms of Mental Activity; Springer International Publishing: Charm, Switzerland, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Plutchik, R. A general psychoevolutionary theory of emotion. In Theories of Emotion; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA USA, 1980; pp. 3–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazarus, R.S. Emotion and Adaptation. In Handbook of Personality: Theory and Research; Pervin: Guilford, CT, USA, 1991; pp. 609–637. [Google Scholar]

- Haase, J.; Wiedmann, K.P.; Labenz, F. Brand hate, rage, anger & co.: Exploring the relevance and characteristics of negative consumer emotions toward brands. J. Bus. Res. 2022, 152, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taqi, M.; Bagozzi, R.P.; Tuğrul, T.; Yaprak, A. The phenomenon of brand hate: A systematic literature review. J. Mark. Theory Pract. 2024, 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, C.A.; Ellsworth, P.C. Patterns of cognitive appraisal in emotion. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1985, 48, 813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haj-Salem, N.; Chebat, J.C. The double-edged sword: The positive and negative effects of switching costs on customer exit and revenge. J. Bus. Res. 2014, 67, 1106–1113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hegner, S.M.; Fetscherin, M.; Van Delzen, M. Determinants and outcomes of brand hate. J. Prod. Brand Manag. 2017, 26, 13–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurtoğlu, R.; Özbölük, T.; Hacıhasanoğlu, P. Revisiting the effects of inward negative emotions on outward negative emotions, brand loyalty, and negative WOM. J. Brand Manag. 2021, 29, 72–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelwahab, D.; San-Martín, S.; Jiménez, N. Does regional bias matter? Examining the role of regional identification, animosity, and negative emotions as drivers of brand switching: An application in the food and beverage industry. J. Brand Manag. 2022, 29, 111–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kujur, F.; Singh, S. Emotions as predictor for consumer engagement in YouTube advertisement. J. Adv. Manag. Res. 2018, 15, 184–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vila-López, N.; Küster-Boluda, I. Opinion leaders on sporting events for country branding. J. Vacat. Mark. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, J.; Fan, X.; Feng, T. Multiple emotional contagions in service encounters. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2011, 39, 449–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattachary, S.; Anand, V. An empirical study to find the road-map for understanding online buying practices of indian youths. Int. J. Online Mark. 2017, 7, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Kucuk, S.U.; Aledin, S.A. Brand bullying: From stressing to expressing. Qual. Mark. Res. Int. J. 2022, 25, 60–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brymer, E.; Schweitzer, R. Extreme sports are good for your health: A phenomenological understanding of fear and anxiety in extreme sports. J. Health Psychol. 2013, 18, 477–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hetland, A.; Vittersø, J.; Oscar Bø Wie, S.; Kjelstrup, E.; Mittner, M.; Dahl, T.I. Skiing and thinking about it: Moment-to-moment and retrospective analysis of emotions in an extreme sport. Front. Psychol. 2018, 9, 971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Monasterio, E.; Mei-Dan, O.; Hackney, A.C.; Lane, A.R.; Zwir, I.; Rozsa, S.; Cloninger, C.R. Stress reactivity and personality in extreme sport athletes: The psychobiology of BASE jumpers. Physiol. Behav. 2016, 167, 289–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Argo, J.J.; Dahl, D.W. Social influence in the retail context: A contemporary review of the literature. J. Retail. 2020, 96, 25–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsieh, J.K.; Tseng, C.Y. Exploring social influence on hedonic buying of digital goods-online games’ virtual items. J. Electron. Commer. Res. 2018, 19, 164–185. [Google Scholar]

- Ozuem, W.; Ranfagni, S.; Willis, M.; Salvietti, G.; Howell, K. Exploring the relationship between chatbots, service failure recovery and customer loyalty: A frustration-aggression perspective. Psychol. Mark. 2024, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Kim, M.; Choi, J.; Trivedi, M. Offline social interactions and online shopping demand: Does the degree of social interactions matter? J. Bus. Res. 2019, 99, 373–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharipudin, M.N.S.; Abdullah, N.A.; Foo, K.W.; Hassim, N.; Tóth, Z.; Chan, T.J. The influence of social media influencer (SMI) and social influence on purchase intention among young consumers. J. Media Commun. Res. 2023, 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Ruiz-Mafe, C.; Tronch, J.; Sanz-Blas, S. The role of emotions and social influences on consumer loyalty towards online travel communities. J. Serv. Theory Pract. 2016, 26, 534–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joshi, R.; Yadav, R. Captivating brand hate using contemporary metrics: A structural equation modelling approach. Vision 2021, 25, 439–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, T.; Li, J.; Ali, A.; Xiaobei, L.; Sheikh, Z.; Zafar, A.U. Mapping online App hate: Determinants and consequences. Telemat. Inform. 2020, 51, 101401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kressmann, F.; Sirgy, M.J.; Herrmann, A.; Huber, F.; Huber, S.; Lee, D.-J. Direct and indirect effects of self-image congruence on brand loyalty. J. Bus. Res. 2006, 59, 955–964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Attiq, S.; Hamid, A.B.A.; Shah, H.J.; Khokhar, M.N.; Shahzad, A. Impact of brand hate on consumer well-being for technology products through the lens of stimulus organism response approach. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 946362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, C.; Laroche, M. Brand hate: A multidimensional construct. J. Prod. Brand Manag. 2020, 30, 392–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Yuan, R.; Liu, M.J.; Luo, J. Luxury symbolism, self-congruity, self-affirmation and luxury consumption behavior: A comparison study of China and the US. Int. Mark. Rev. 2022, 39, 166–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, T.; Moreira, M. Consumer brand engagement, satisfaction and brand loyalty: A comparative study between functional and emotional brand relationships. J. Prod. Brand Manag. 2019, 28, 274–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schönberner, J.; Woratschek, H. Sport sponsorship as a booster for customer engagement: The role of activation, authenticity and attitude. Int. J. Sports Mark. Spons. 2023, 24, 259–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.P.; Frethey-Bentham, C.; Juric, B.; Brodie, R.J. A negative actor engagement scale for online knowledge-sharing platforms. Australas. Mark. J. 2023, 31, 36–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hollebeek, L.D. Exploring customer brand engagement: Definition & themes. J. Strateg. Mark. 2011, 19, 555–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juric, B.; Smith, S.D.; Wilks, G. Negative customer brand engagement: An overview of conceptual and blog-based findings. In Customer Engagement; Routledge: Abingdon-on-Thames, UK, 2015; pp. 278–294. [Google Scholar]

- Do, D.K.X.; Bowden, J.L.H. Negative customer engagement behaviour in a service context. Serv. Ind. J. 2023, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pansari, A.; Kumar, V. Customer engagement: The construct, antecedents, and consequences. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2017, 45, 294–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czellar, S.; Luna, D. The effect of expertise on the relation between implicit and explicit attitude measures: An information availability/accessibility perspective. J. Consum. Psychol. 2010, 20, 259–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sohail, M.S.; Awal, F. Examining the impact of self-image congruence on brand preference and satisfaction: The moderating effect of expertise. Middle East J. Manag. 2017, 4, 133–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evanschitzky, H.; Wunderlich, M. An examination of moderator effects in the four-stage loyalty model. J. Serv. Res. 2006, 8, 330–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pikkemaat, B.; Bichler, B.F.; Peters, M. Exploring the crowding-satisfaction relationship of skiers: The role of social behavior and experiences. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2020, 37, 902–916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woodman, T.; Hardy, L.; Barlow, M.; Le Scanff, C. Motives for participation in prolonged engagement high-risk sports: An agentic emotion regulation perspective. Psychol. Sport Exerc. 2010, 11, 345–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunn, L.; Hoegg, J. The impact of fear on emotional brand attachment. J. Consum. Res. 2014, 41, 152–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Racherla, P.; Mandviwalla, M.; Connolly, D.J. Factors affecting consumers’ trust in online product reviews. J. Consum. Behav. 2012, 11, 94–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yildiz Durak, H.; Haktanir, A.; Saritepeci, M. Examining the predictors of video game addiction according to expertise levels of the players: The role of time spent on video gaming, engagement, positive gaming perception, social support and relational health indices. Int. J. Ment. Health Addict. 2023, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hollebeek, L.D.; Glynn, M.S.; Brodie, R.J. Consumer brand engagement in social media: Conceptualization, scale development and validation. J. Interact. Mark. 2014, 28, 149–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kline, R.B. Principles and Practice of Structural Equation Modeling, 5th ed.; The Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.F., Jr.; Hult, G.T.M.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M.; Danks, N.P.; Ray, S. Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM) Using R: A Workbook; Springer Nature: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2021; Available online: https://library.oapen.org/handle/20.500.12657/51463 (accessed on 12 May 2024).

- Chin, W.W. Commentary: Issues and opinion on structural equation modelling. MIS Q. 1998, 22, 7–16. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/249674 (accessed on 12 May 2024).

- Rodrigues, P.; Pinto Borges, A. Negative emotions toward a financial brand: The opposite impact on brand love. Eur. Bus. Rev. 2021, 33, 272–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Sarstedt, M.; Hopkins, L.; Kuppelwieser, V.G. Partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM): An emerging tool in business research. Eur. Bus. Rev. 2014, 26, 106–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Lynch, J.G., Jr.; Chen, Q. Reconsidering Baron and Kenny: Myths and truths about mediation analysis. J. Consum. Res. 2010, 37, 197–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siu, N.Y.M.; Zhang, T.J.; Yeung, R.S.P. The bright and dark sides of online customer engagement on brand love. J. Consum. Mark. 2023, 40, 957–970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burke, S.M.; Durand-Bush: Doell, K. Exploring feel and motivation with recreational and elite Mount Everest climbers: An ethnographic study. Int. J. Sport Exerc. Psychol. 2010, 8, 373–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iranzo-Barreira, A.; Kuster, I.; Ruiz-Mafe, C. Inward negative emotions and brand hate in users of snow-sports’ brands. J. Prod. Brand Manag. 2024, 33, 745–760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).