Abstract

In Romania, the pandemic and post-pandemic effects, coupled with the nearly 80% increase in internet service penetration, have led to an extraordinary acceleration of e-commerce activity. Rising rents and operational costs, heightened financial challenges, and the improved quality and accessibility of internet connectivity have prompted some Romanian SMEs to sell their products and services online or through other online communication networks. In this context, it becomes essential to conduct marketing research to identify factors that could stimulate business performance. The purpose of this study is to assess the impact of e-marketing orientation, sustainability orientation, and technology orientation on the performance of online SMEs in Romania. Hypothesis testing and validation of the proposed construct model were conducted using structural equation modeling with partial least squares (SEM-PLS) and multi-group analysis (PLS-MGA). The research results have indicated that all three independent variables have positive and significant effects on online SMEs’ business performance. Finally, the study suggests that SME managers should focus on integrating these three variables and on selling products and services both nationally and internationally through the internet if they aim for long-term business performance growth.

1. Introduction

During the pandemic and post-pandemic period, both small- and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) worldwide and those in Romania faced unprecedented challenges such as business and liquidity disruptions, a decreased market demand, unemployment constraints, the lack of infrastructure for rapid digital business transformation, and others. Simultaneously, in order to cope with the economic, social, and environmental challenges of recent years, SMEs also had to prepare for the transition to a digital and sustainable economy. In this regard, SME managers have become aware of the need to integrate new approaches regarding business orientation to address these challenges.

Derived from market orientation, e-marketing orientation (EMO) is more of a culture that illustrates the extent to which enterprises respond to customer desires and make decisions based on information about customer needs and preferences. Recent studies suggest that small- and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) that demonstrate greater sensitivity to customer needs and desires may differentiate themselves in the market and achieve more business benefits, such as personalized communication with customers, adapting products and services to customer needs, reducing transaction costs [1], broader market coverage, improved customer service quality [2,3], facilitating communication with stakeholders, or opportunities for new product development [4,5,6].

At the same time, Romanian enterprises must undertake responsible actions towards the economy, society, and the environment to contribute to the building of a sustainable economy. Some research highlights the fact that an increasing number of SMEs have proceeded to reconfigure their strategic orientation, directing their focus towards new sustainable development actions [7]. Gradually, they have begun to integrate the principles and objectives specific to sustainable development, such as economic development, social development, and environmental protection, known to practitioners and researchers as sustainability orientations (SOs) [8]. Previous research suggests a series of long-term benefits that enterprises could obtain by implementing sustainability orientation, for example: external benefits—obtaining financial support for the implementation of process re-engineering measures for resource efficiency, improving value and performance through technical and business consulting, strengthening ties with the community, and recycled products [9,10]; and internal benefits—reducing production costs, improving the image and brand of the enterprise, organizational value and culture, and management and employee commitment [11].

Technology orientation (TO) has recently gained particular attention from both entrepreneurs and managers, as well as researchers. The integration of new technologies within SMEs could yield multiple long-term benefits, such as easy, fast, and efficient communication with stakeholders, efficient manufacturing techniques, reduced waste, effective inventory and ordering systems, new sales channels, and new capacities for developing innovative approaches [12,13].

In Romania, SMEs represent 89% of the total companies in the economy (around 500,000 SMEs) and three-quarters of the jobs in the private sector. Moreover, they contribute nearly 62% to the Romanian GDP and are the primary creators of added value in most sectors. Considered the pillars of the Romanian economy, SMEs continue to play an essential role in accelerating economic growth and currently contribute to the digital and ecological transition to address current competitive challenges in the context of economic digitization [14]. In Romania, the rapid development of information technology (IT) over the last five years has altered the purchasing and consumption behavior of the population and has enhanced the development, innovation, and adaptability capacity of SMEs to market needs, trends, and requirements. This supports the construction of a fair and competitive digital economy.

As SMEs remain the primary contributors to the Romanian GDP, few studies have identified and evaluated the common influence of specific factors on their performance in the post-pandemic context. A recent study showed that the implementation of circular economy practices and the integration of IT solutions lead to higher profitability rates among Romanian agri-food SMEs, especially if they exhibit high risk and increase the number of digital investments [15]. Another study demonstrated that the performance of Romanian SMEs, particularly young ones, improves when resorting to external consulting services in financial, accounting, marketing, IT, environmental protection, and others [16].

Considering the increasing number of individuals conducting digital transactions among internet users and the growing presence of Romanian SMEs in the e-commerce market in Romania, we believe that conducting marketing research is essential for assessing the common impact of current determinant factors on the performance of their online businesses [17]. There is a heightened interest in analyzing the role of business orientations among SMEs that vary in the adoption and integration of e-marketing, sustainability, and technology. The existing literature lacks any research providing empirical evidence regarding the common impact of these three orientations on the performance of online SMEs.

This study aims to evaluate the impact of e-marketing orientation (EMO), sustainability orientation (SO), and technology orientation (TO) on online SME business performance (OBP) in Romania (See Table 1).

Table 1.

Research objects.

This study provides several valuable contributions. First, it addresses a new theme by identifying and analyzing the determinants’ effects on the performance of online SMEs and complements the existing literature on improving business performance. Second, the study develops a new multidimensional model, proven to be valid and robust, offering developmental perspectives for future studies. Third, the study enhances the literature on business orientations among SMEs. Existing studies indicate that the attention of managers and researchers has generally focused on the effects of sustainability and technology orientations on business performance, with less emphasis on the role and opportunities offered by e-marketing orientation for the development of SMEs. The pandemic and post-pandemic experience have demonstrated that the internet continues to provide multiple opportunities for SMEs, particularly in promoting and distributing products and services through websites and social media platforms. The combination of the three latent variables and their impact on business performance highlights the essential role played in managing online SMEs and their contribution to the development of a sustainable Romanian economy in the future.

The following section provides a review of relevant literature, frames hypotheses regarding the e-marketing, sustainability, and technology orientation of online SMEs, and illustrates the profound changes we are witnessing. These changes are marked by the reshaping of e-commerce systems to enhance business performance, the modification of how enterprises work, communicate, and gather information using new technologies, the shift in consumer behavior, and changes in production and consumption systems to support social development and contribute to the regeneration and preservation of natural environments. Section 3 presents a phased approach to the research method, data collection and analysis, respondent profiles, questionnaire validation, and common method bias. Section 4 unfolds the results of the marketing research. Section 5 introduces the discussion on the obtained data and the theoretical and managerial implications of the study. The limitations and future research directions complete Section 6.

2. Literature Review and Hypothesis Development

The COVID-19 pandemic has generated profound changes in e-commerce behavior, altering the way entrepreneurs organize and develop their businesses, and establish strategies for selling and promoting products and services, as well as how consumers choose to make purchases and payments. Furthermore, the internet and digital technologies have proven to be crucial tools for the development of e-commerce and online transactions [18]. Both during and after the pandemic, e-commerce has become the saving grace for the majority of traditional stores. They were forced to quickly implement or expand online sales, click-and-collect shopping services, or home delivery. In recent years, e-commerce has developed differently from country to country, depending on the imposed restrictions and the nature of the business. To remain competitive and agile in an increasingly competitive and dynamic business environment, SMEs must have a good absorptive capacity and efficient corporate entrepreneurship to constantly mediate the relationship between information technology capabilities and firm performance [19].

2.1. E-Marketing Orientation (EMO)

The transition from mass production (the Second Industrial Revolution) to automated production (the Intelligence Revolution) has been marked by economic transformations where new energy systems work in conjunction with emerging communication technologies. The convergence of information and communication technology through the internet with renewable energies in the 21st century has given rise to profound changes in the market, including the emergence of new forms of communication between enterprises, stakeholders, and clients; the use of diverse means of business management and organization; market segmentation, specialization, and distinct positioning; a better organization of marketing activities and the creation of conditions for an open market accessible to everyone; and the increased role and importance of SMEs in the market [20].

Electronic marketing, also known as e-marketing, encompasses the entirety of marketing activities conducted through the internet. Both the literature and economic practice often use this term interchangeably with internet marketing, web marketing, online marketing, or digital marketing [21]. The importance of e-marketing has been amplified by the transformation and popularity of the internet in recent years. E-marketing, utilizing the internet as a platform, has brought about significant changes in business and consumer behaviors. Furthermore, it has enabled enterprises to attract new customers and expand existing ones, promote and sell more products and services, develop a brand identity, adopt marketing strategies in correlation with the current needs of customers, reduce transaction costs, communicate more effectively with customers, and eliminate time and location constraints inherent in traditional distribution channels [22].

Marketing orientation remains a business approach that mandates all processes of the development and creation of new products or services to be focused on meeting the current needs of consumers [23]. In contrast, the new concept of strategic orientation, namely, e-marketing orientation (EMO), is committed to a superior enterprise performance through the use of the internet and digital technologies in delivering products and services to customers based on their needs and preferences [24].

In the technology era, e-marketing has become an integral and indispensable part of marketing policies and strategies regardless of the nature and size of the enterprise. According to [25], EMO represents a modern business philosophy that provides SMEs with the opportunity to promote products and services through the internet and online-based digital technologies, such as desktop computers, mobile phones, digital platforms, social media, etc. As this orientation becomes increasingly popular among practitioners and researchers, various typologies of e-marketing are evident in the market, such as social media marketing, mobile marketing, email marketing, search engine optimization (SEO), and paid advertising (PPC). However, regardless of the typology used, e-marketing orientation offers multiple advantages to enterprises, regardless of their size and market experience. Investigating the adoption of internet-based e-commerce among SMEs in Turkey, Ref. [4] observed that e-marketing orientation provides the ability to target customers more quickly and cost-effectively through the distribution of useful and relevant content.

The most commonly used tools for this purpose are video marketing, blog posts and articles, social media content through the influence of influencers, targeted advertising, or referral marketing. The implementation of e-marketing also contributes to reducing opportunity costs through the automation of electronic supports [26], and operating and marketing costs [27], as well as transaction costs [28]. In addition to cost reduction, Ref. [29] observed that the use of e-marketing platforms leads to better geographical targeting and increased visibility, providing SMEs with the opportunity to attract more customers, and deliver large quantities of information, unlimited and without human intervention, in an easily processed and understood form.

Through e-marketing orientation, enterprises can quantify and collect customer data [30], provide visual maps of digital knowledge for consumers [31], create customer relationship management (CRM) systems that match customer preferences [32], and develop marketing systems using email as a delivery method [33]. Numerous technologies such as computer telephony in call centers, web-based text chat or voice, web-based catalogs chat rooms, email, personalized web pages, FAQ pages or large databases, frequently asked questions (FAQ) pages, CRM databases, call centers that use computer telephony, POTS telephony, IP telephony permit real-time interaction between enterprise marketing agents and end consumers [34,35,36].

Ref. [37] argued that, in the conditions of volatile and turbulent demand, such as the online fashion market, enterprises can ensure success only through flexibility and responsiveness to change. This involves incorporating current customer preferences into the design and production process, reacting quickly to product launches, and swiftly adjusting the product sales volume. Ref. [38] proposed a new approach to “integrated e-marketing value creation” processes on the internet, providing enterprises with information about the need to develop e-marketing strategy implementation skills in a short timeframe to ensure success in the digital world. According to [39], using a strategic approach and one-to-one marketing relationship management processes, enterprises can achieve value exchanges based on information about market segments’ receptiveness and preferences, despite increasing consumer confidentiality. Ref. [40] had shown that, in order to gain a market positional advantage and enhance long-term performance, enterprises must integrate market, entrepreneurial, and learning orientations, as well as the use of specific internet marketing technologies.

Ref. [41] argued that, for small- and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) to take the best measures to improve e-commerce performance, they must identify the factors affecting the extent of e-marketing coverage from the perspective of organizational orientation. Thus, e-marketing orientation (EMO) becomes a necessary strategic action that, alongside other enterprises activities, contributes to enhancing customer satisfaction and business performance. The specialized literature indicates a limited number of studies examining the effect of EMO on SME performance. Ref. [42], examining the interrelationship between market orientation and EMO, attempted to identify alternative mechanisms contributing to the improvement of tourism service performance. Ref. [43] argued that SMEs adopting “alternative” marketing approaches, such as industrial, business, contact, social, and network marketing, can enhance their financial performance. Ref. [44] demonstrated that adopting EMO and utilizing electronic media can lead to long-term marketing performance improvement, particularly evident through increased sales and attracting a larger consumer base. The positive effect of EMO on firm performance, reflected in sales, customer satisfaction, and relationship development, has also been reported by [45].

Ref. [46] had shown that supporting secondary processes of the enterprise (product quality, cycle time, customer service, stakeholder relations, and employee satisfaction) contributes to achieving primary objectives related to satisfying consumer needs and increasing profit. It is necessary to use a performance measurement system for both financial and non-financial aspects. Analyzing the effect of multiple capabilities and brand orientation on SME performance, Ref. [26] observed an increase in financial performance following the application of e-marketing capabilities. E-marketing orientation (EMO) should be viewed by SMEs in developing countries as a means of improving strategic business performance, as a way to enhance e-trust with customers [47]. Ref. [48] suggested that business strategic performance increases as SMEs set objectives and adopt specific EMO and e-trust strategies.

2.2. Sustainability Orientation (SO)

SMEs represent the key to transitioning towards more sustainable economies. In recent years, they have faced external pressures to adapt to the effects of climate change and environmental degradation, as well as pressures from stakeholders—organization owners, business partners, directors, and public institution employees, banks, suppliers, and consumers. Generally, SMEs have limited financial resources, making their daily operations a major priority in the face of the transition to sustainability. However, they can implement proactive actions, options to encourage the emergence of innovation projects, the launch and commercialization of new products, and the implementation of advanced production technologies to enhance competitiveness [49]. Sustainability orientation has become a necessity for most enterprises in the post-COVID-19 era. They have had to adopt a proactive approach to sustainability, implement new strategic alternatives, gain added value in cloud computing, and attract and nurture young talents, transforming them into vectors of both strategic and sustainable development. A recent study shows that an increasing number of SMEs are interested in sustainable development and adopting sustainable business models. Market changes, technological innovation, stakeholder influences, government policies, and relationships with public institutions, as well as openness to new ideas, mindset change, problem-solving, social exchange, and resource utilization are key factors increasingly facilitating SMEs’ transition to adopting new sustainable business models [50].

Sustainability orientation represents a modern approach that involves expanding the economic dimensions of the enterprise’s activity by incorporating environmental protection measures and social responsibility. Ref. [51] stated that sustainability orientation entails adopting a proactive stance toward integrating the best environmental practices and social actions into the strategic, tactical, and operational activities of the enterprise. Ref. [52] had shown that the degree of the sustainability orientation of the enterprise can be assessed based on environmental and social strategies and policies, and the organization of environmental management, as well as communication and problem-solving regarding environmental and social issues. According to [53], sustainability orientation involves a triad of interconnected pillars: economic, environmental, and social orientation. Economic orientation evaluates changes in the enterprise’s performance based on aspects such as the level of achievement of sustainable economic objectives, the changes and diversification of factors necessary for value creation, and the level and evolution of productivity and efficiency. It guides the enterprise in the business environment, influences operational conditions, and affects the organization’s planning, organization, and control capacity, necessary for overcoming daily vulnerabilities or those induced by crises [54,55].

Environmental orientation involves a series of different actions and processes on the part of the enterprise, such as renewing resources and using less harmful substitutable materials, introducing cutting-edge technologies in the production process and less polluting processes, reducing water, energy, and gas consumption, recycling waste, and adopting environmental policies, ethics, and training courses [56,57]. Sustainability orientation towards the environment also entails integrating environmental considerations into the overall business strategy and reconfiguring the organizational structure [51], ensuring the robust management of environmental practices [58], evaluating unsustainable ecological production operations and technologies [52], or identifying new alternative resources [59].

Ref. [60] stated that social orientation represents a philosophy that includes internal elements specific to the cultural environment, such as the mission, vision, values, and beliefs, and structural and organizational domains, and external elements, aligning the enterprise’s objectives with those of stakeholders. Social sustainability orientation involves taking on social and ethical responsibilities in business, such as improving living and working conditions for employees, engaging in activities related to environmental protection, sponsoring education, arts, and sports, or carrying out philanthropic acts [61]. Over time, other aspects have come into play, including increasing employment rates, improving labor relations, ensuring occupational safety, adopting fair work practices, respecting human rights, protecting consumers, conserving and protecting the environment, developing local communities, and combating financial fraud or corruption [62].

Overall, sustainability orientation is an organizational capability that enables enterprises to undertake risky and innovative initiatives, contributing to gaining long-term competitive advantages and superior (financial) performance. Empirical studies indicate that, by applying sustainability orientation, enterprises can gain competitive advantages such as the creation of innovative ecological products [63], the development of an ecological design to enhance sustainability performance throughout the life cycles of new products [64], the transition of SMEs to sustainable business models involving the adoption of the philosophy, values, products, processes, or practices of the circular economy [65], and the creation and use of practical platforms for the future that allow for the reduction in natural resource consumption [66].

Possessing a sustainable competitive advantage translates to profitability for the enterprise. According to [67], entrepreneurial orientation (EO) provides enterprises with an alternative to strategic differentiation, making it easier to gain a competitive advantage in the market. Specialized literature indicates a limited number of empirical studies demonstrating the impact of EO on business performance. Ref. [51] demonstrated that the adoption of entrepreneurial and environmental sustainability orientations by SMEs in the Philippines contributes to improving business performance, highlighting the significant impact of sustainable orientation (SO) on their performance. Analyzing the effects of implementing sustainability strategies in the production activities of American enterprises, Ref. [53] observed that a sustainability orientation leads to the development of circular and sustainable products, generating a common and direct impact on environmental performance and, consequently, business performance. Ref. [67] demonstrated that Ghanaian enterprises can achieve a higher performance by practicing environmental sustainability orientation. The effective integration of SO across the entire business process can only be ensured by achieving sustainability goals and investing in dynamic and relational capabilities that contribute to enhancing economic, social, and environmental performance [68]. Ref. [69] showed a positive correlation between SO and business performance, particularly with the increasing age of SMEs in the market. Ref. [70] demonstrated a significant positive effect of sustainability orientation and marketing orientation on marketing performance. Moreover, the same study demonstrates that SO has a strong impact on marketing orientation.

2.3. Technological Orientation (TO)

Globalization has brought radical changes to communications, the economy, and society. Aspects such as digitization, robotics, the internet of things (IoT), cloud and SaaS, artificial intelligence (AI), 3D printing, and GPS have altered the way enterprises design, produce, work, transport, and sell. Globalization has provided SMEs with a series of opportunities, including the integration of digital technologies, the use of e-commerce, and access to new expanded markets, but also vulnerabilities, such as information security and the transfer of business data via personalized email [71].

In this context, technology orientation (TO) becomes a necessary strategic action for all enterprises in the market, aiming at integrating and using modern technologies in all dimensions of enterprises operations, both related to products and services, and the procedures for obtaining them [72]. Ref. [73] defined technology orientation as the capacity to adopt and use new technologies necessary for the development of environmentally friendly and energy-efficient innovative products. Ref. [74] argued that enterprises should increasingly adopt advanced technology to support both the development of new products and the improvement of existing ones. Technology orientation involves the desire and commitment to proactively integrate theories and techniques that allow the practical use of technological knowledge and resources for obtaining new raw materials, integrating sophisticated technologies during the development of innovative products, facilitating work and tasks, identifying new target segments, meeting consumer needs, or improving the quality of life [75,76,77]. Ref. [78] stated that, to cope with the pace of changes and renew products, enterprises must modify their strategic approach to customer relationship orientation, technology orientation, and entrepreneurial orientation, resorting to external sources of knowledge.

Analyzing the effect of strategic orientation on performance among American and Japanese enterprises, Ref. [74] demonstrated that, unlike customer orientation and cost orientation, technology orientation shows a negative effect on short-term profitability due to the high costs associated with implementing new technologies. Similarly, Ref. [79] argued that leading IT companies in the United States did not achieve a high financial performance, although they acknowledge that expanding their IT capacity contributed to increasing product and service differentiation, as well as revenue and profits. Ref. [80] ruled out a positive relationship between technology orientation and business performance as long as enterprises do not expand their research and development activities, fail to develop employees’ technological capabilities, do not integrate advanced technologies, and do not use IT tools to better understand current consumer needs.

On the other hand, Ref. [81] recommended Nigerian manufacturing enterprises to be creative and innovative, and adopt modern production techniques to cope with current global challenges, demonstrating a strong positive relationship between performance and technology orientation (TO), as well as between performance and production techniques. Analyzing the impact of strategic orientation on organizational performance in the Jordanian pharmaceutical sector, Ref. [82] proved a statistically significant relationship between TO and organizational performance. Other previous studies have indicated similar results, demonstrating that TO, despite involving risk-taking, leads to the development of innovative products, services, and processes, and the creation of new markets, shaping consumer behavior, and meeting their evolving needs [83,84,85,86,87].

Ref. [88] observed that improving business performance can be ensured by enhancing customer and technology orientations, along with customer loyalty. Therefore, SMEs that quickly adopt customer and technology orientations will succeed in finding efficient ways to attract loyal customers and enhance their business. Ref. [89] argue that the use of new technologies such as cloud computing, blockchain technology, machine learning, and artificial intelligence (AI) has contributed to improving the performance of businesses in Pakistan, especially those in the software industry. Furthermore, they recommend managers to focus on technology orientation (TO) and innovation to enhance business performance in the future. Ref. [90] observed that the use of technological advancements and innovations in business contributes to improving the performance of SMEs in East Java, Indonesia, while the impact of TO on market orientation is reduced through technological education.

Analyzing the impact of organizational culture dimensions and proactive marketing behaviors on business performance, Ref. [91] observed that technology orientation (TO) has a significant impact on business performance, correlating positively with both proactive market orientation and market pioneering. Ref. [92], conducting a quantitative study among Polish providers of technological services, found that organizational culture and human resources strengthen the relationship between TO and organizational performance, while weak human resource management diminishes its effect. Ref. [93] demonstrated that developing the IT adoption capability is crucial for the entrepreneurial, technological, and marketing orientation of enterprises in Indonesia and Singapore. Moreover, enterprises that integrate more TO are better able to respond to market challenges and achieve innovative products, leading to higher future performance. Ref. [94] showed that the adoption of responsive and proactive market orientation and TO by Italian manufacturing firms contributes to improving performance in terms of sustainable innovation. Ref. [95] demonstrated that the simultaneous orientation toward technology and customers in Chinese enterprises generates a significant positive influence on business performance.

2.4. Online SME Business Performance (OBP)

Business performance represents the ability of an enterprise to effectively and efficiently use resources, including online resources, to achieve its strategic objectives. In practice, managers constantly seek new solutions that contribute to the growth of small- and medium-sized enterprises’ (SMEs) business performance. Their achievements are measured using key performance indicators that have experienced continuous dynamics over time. Some studies have discussed business performance in quantitative terms (profitability, productivity, sales/profit/market share growth, and website-generated traffic) and qualitative terms (company image, competitive advantage, and customer relationships) [96,97,98,99]. Other experts have grouped business performance measurement parameters into strategic (return on investment, revenues, market share), operational (sales by region, acquisition cost (CPA), and transportation), functional unit (return on assets, and gross profit margin), or leading vs. lagging (the index of consumer confidence, average hours worked, unemployment figures, profits, or interest rates) [100].

Analyzing the effects of circular economy practices on the performance of European SMEs, Ref. [10] grouped measurement parameters into three categories: economic performance, environmental performance, and social performance. Ref. [101], attempting to identify the most important strategic performance indicators for Turkish enterprises, grouped measurement parameters into financial marketing performance (profitability, cash flow, and sales/market share) and non-financial (brand equity, customer loyalty, and satisfaction). Online business performances are monitored by IT teams through efficiency indicators (average service ticket resolution time) and operational indicators (availability of online applications) [102].

2.5. Research Model and Hypothesis

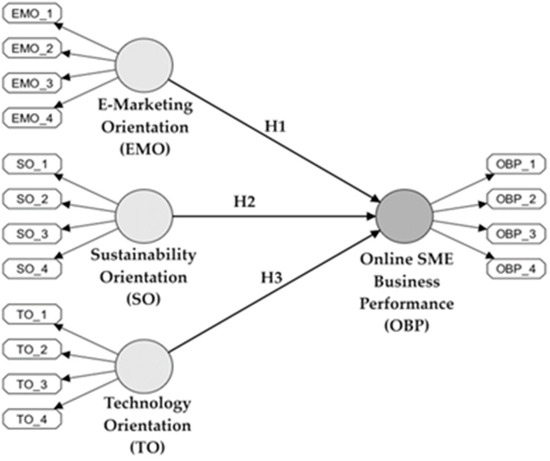

Based on the analysis of previous literature and the establishment of research objectives, the study proposes a new multidimensional model (see Figure 1). Within the proposed construct model, EMO, SO, and TO are treated as independent variables, while OBP is considered the dependent variable.

Figure 1.

Research model of the study.

In relation to the first objective (Q1), three statistical hypotheses have been formulated:

Hypothesis 1 (H1).

E-marketing orientation (EMO) has a positive and significant effect on online SME business performance (OBP).

Hypothesis 2 (H2).

Sustainability orientation (SO) has a positive and significant effect on online SME business performance (OBP).

Hypothesis 3 (H3).

Technological orientation (TO) has a positive and significant effect on online SME business performance (OBP).

Regarding the second objective (Q2), three additional hypotheses have been formulated as follows:

There are no significant differences between e-commerce intensity groups in the construction of e-marketing orientation (EMO) → online SME business performance (OBP).

There are no significant differences between e-commerce intensity groups in the construction of sustainability orientation (SO) → online SME business performance (OBP).

There are no significant differences between e-commerce Intensity groups in the construction of technology orientation (TO) → online SME business performance (OBP).

3. Method

3.1. Materials and Measurement

This study used the online questionnaire as the main tool for collecting data from Romanian SMEs. In recent years, Romania has become one of the most profitable e-commerce markets, estimated at around 6.2 billion euros in 2021, or over half of the total sales in Eastern Europe [103]. The COVID-19 pandemic has had a significant impact on e-commerce sales [104,105]. By the end of 2022, e-commerce turnover had increased by 13% compared to 2021, reaching 7 billion euros (Ecommerce-Europe, 2022) [106]. In the first half of 2023, Romanian online SMEs contributed 3.17% to the GDP, ranking 3rd in Central and Eastern Europe and 12th across the entire European continent [107]. Therefore, the ongoing development of the e-commerce market in Romania provides a favorable opportunity to test the proposed construct model (see Figure 1), and the collected data can contribute to the current literature on online SMEs.

The questionnaire included 8 information questions and 16 closed-content questions, allowing managers to select appropriate responses based on their situations. The first part included demographic information about online SMEs and their representatives. In the second part, items specific to each latent variable of the proposed construct model were integrated, in line with the research’s purpose. The online questionnaire link was distributed to SME managers via email and social networks. The use of these marketing tools was considered appropriate as it enables easy data collection from the active research population and aligns with the research’s purpose. The questionnaire was pretested in a pilot test with a sample of 20 managers, and the results contributed to improving the formulation and structure of the questionnaire [108]. Subsequently, managers of online SMEs were requested, via email, to provide consent to participate in the study and complete the online questionnaire.

3.2. Data Collection

To test the research hypotheses and achieve the set objective, an online survey was conducted among SMEs operating in the e-commerce market in Romania, from August to October 2023. Simple random sampling was employed in the research design. From the www.listafirme.ro (22 August 2024) database, 976 relevant observation units were randomly selected—Romanian online SMEs that, based on the provided information, align with the investigated domain. This probabilistic sampling method helps minimize biased samples and generates reliable survey results. Managers of online SMEs were contacted via email to seek their participation consent in the study and to distribute and complete the online questionnaire.

3.3. Measurement Items

We followed [42,48,109,110] and measured e-marketing orientation (EMO) with four items, taking into account the use of e-marketing resources to communicate with the target audience (EMO_1), ensure continuity of traditional activities (EMO_2), perform transactions (EMO_3), and build and use a customer database (EMO_4) necessary for streamlining the marketing activities of online SMEs. The interest of online SMEs in sustainability orientation (SO) focused on achieving human resources development goals (SO_1), achieving economic goals (SO_2), achieving social protection goals (SO_3), and achieving environmental and climate goals (SO_4), adapted from studies [53,111,112].

Technology orientation (TO) was assessed through specific measurement elements, such as attracting “future-oriented entrepreneurs” (TO_1), “technological innovation adoption/development and diffusion” (TO_2), training “customer-oriented technicians” (TO_3), and the integration of “new employee technology orientation” (TO_4), processed according to research by [82,92,93,113]. The measurement elements of online SME business performance (OBP) captured aspects related to e-marketing (non-financial) performance (OBP_1), financial performance (OBP_2), social and environmental performance (OBP_3), and technology performance (OBP_4), adapted from various previous studies [113,114,115,116,117,118]. All 16 items of the model were measured using a seven-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 = “Strongly Disagree” to 7 = “Strongly Agree”. For informational questions, nominal scales with a single response possibility were used. SPSS 28 was used for data processing and verification of the collected data.

3.4. Data Analysis

To analyze the data, the construct model, and test the hypotheses, structural equation modeling with partial least squares (PLS-SEM) and multi-group analysis (PLS-MGA) were employed. PLS-SEM allows the simultaneous analysis of measurement and structural models. PLS-SEM is particularly useful in studies involving success factors [119] and analyses of usage intentions. In this study, this methodological approach is considered prominent [120,121], with numerous journals publishing review studies on its application in various disciplines, including information management and marketing [119,122]. PLS-SEM was chosen to test the proposed research model due to its suitability for explanatory, predictive, and theoretical applications. Its advantages lie in the ability to analyze complex models that include diverse latent variables and its suitability for assessing the influence of exogenous variables on endogenous ones in exploratory studies [119].

As the first objective of this study is to identify the impact of independent variables—e-marketing orientation (EMO), sustainability orientation (SO), and technology orientation (TO)—on the dependent variable online SME business performance (OBP), we believe that PLS-SEM is appropriate for analyzing the construct model. Therefore, previous marketing studies with similar latent variables were reviewed to analyze the data using PLS-SEM [42,43,44,45,46,68,69,70,91,92,93,94,95]. Multi-group analysis (PLS-MGA) was deemed suitable for examining significant differences between e-commerce intensity groups in the constructions EMO → OBP, SO → OBP, and TO → OBP. It utilizes independent t-test probes to compare paths between groups and determine if the PLS model significantly differs among them [123]. Smart PLS 4 software was used for analyzing the collected data from the sample members [119].

3.5. Respondent Profile

Overall, 976 questionnaires were distributed online to Romanian online SMEs; 37 out of the 381 collected questionnaires were excluded due to ambiguous, incomplete, or partial responses. In the end, the sample included 344 valid questionnaires, resulting in a response rate of 35.24%. Its size was well above the minimum accepted threshold, namely, at least 112 responses (16 items × 7 = 112 responses) [109]. Similar sampling approaches and latent variable measurement methods in the case of different multidimensional models have been used in some previous studies [124].

During the analyzed period, online SMEs reported consistent e-commerce activities for at least three years. Differing in size (micro—18.02%, small—42.15%, and medium—39.83%), they operate in the manufacturing sector (11.99%), technology (7.60%), and services (80.41%). The value of transactions resulting from e-commerce usage (e-commerce intensity) reaches up to 500,000 euros per year for 62.50% of enterprises, while only 6.69% manage to achieve a turnover exceeding 1.5 million euros per year. The proportion of senior managers interviewed was 48.70%, and that of CEOs/managing directors (MD)/business owners reached 28.7%. Among them, 38.08% are women (see Table 2). Most managers are between 31–50 years old (63.37%), and more than half of the respondents have higher education (66.57%).

Table 2.

Demographic information about online SMEs.

3.6. Questionnaire Validation: Preliminary Results

The collected data were entered into the SPSS application to verify the accuracy of the information provided by the enterprises through their representatives and to eliminate any errors. Interactive data validation involves validating the questionnaire after making the necessary corrections. For the three latent variables, preliminary results (for 156 respondents) showed the following: e-marketing orientation (CA = 0.831, AVE = 0.748), sustainability orientation (CA = 0.776, AVE = 0.681), and technology orientation (CA = 0.829, AVE = 0.754). The values of the Cronbach’s alpha (CA) and average variance extracted (AVE) indicators are above the minimum threshold of 0.6; therefore, the preliminary results demonstrate the validity of the model [120].

3.7. Common Method Bias

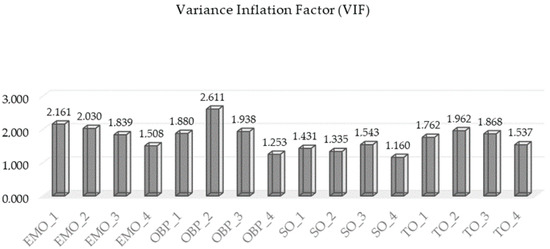

Research indicates that independent and moderating constructs may be susceptible to possible multicollinearity issues; therefore, for developing appropriate interaction relationships, these constructs should be standardized and mean-centered [125]. To avoid common method bias (CMB) and inflate the magnitude of the relationships between the latent variables of the proposed construct model, a collinearity assessment was conducted following the procedures suggested by [119]. The variance inflation factor (VIF) measures for all constructs range between 1.160–2.611. Since these values are below 4.0 [126], there is no evidence of CMB in this research (Table A2). Moreover, all correlations between constructs present measures smaller than the maximum threshold of 0.9, demonstrating the avoidance of CMB.

4. Results

4.1. Measurement (Outer) Model Results

The measurement model evaluation was conducted based on composite reliability (CR), convergent validity—Cronbach’s alpha (CA), average variance extracted (AVE), and item loadings. Alongside the item loadings, Table 3 presents the results of Cronbach’s alpha (CA), composite reliability (CR), and average variance extracted (AVE) indicators. The majority of item loadings range from 0.701 to 0.871, exceeding the intermediate threshold of 0.70 [119]. An exception is the SO_2 indicator, which shows a loading of 0.564; however, it is not excluded from the analysis since it surpasses the minimum threshold allowed for exploratory purposes of 0.50 [126]. The Cronbach’s alpha (CA) coefficients range from a minimum of 0.795 to a maximum of 0.834, exceeding the conventionally accepted limit for good scale reliability of 0.70 [119]. The CR indicators fall within the range of 0.753–0.842, surpassing the 0.70 threshold [119]. AVE scores, ranging from 0.627 to 0.669, were higher than 0.5 [120]. Thus, the measurement model exhibits appropriate consistency, demonstrating both convergent and divergent validity.

Table 3.

Measurement of items loading, CA, CR, and AVE.

The discriminant validity of the construct model was established based on the Fornell–Larcker criterion, cross-loadings, SMRM output, and heterotrait–monotrait ratio (HTMT). Table 4 explains that the square root AVE for the exogenous variable EMO is higher than its correlations with the other variables (0.818 > 0.693; 0.706; 0.846) [127]. The intentional loadings of latent variables were higher than 0.7 [128] and cross-loadings should be less than 0.6 [119] (see Appendix A, Table A1).

Table 4.

Discriminant validity of measurement model—based on the Fornell and Larcker criterion.

Additionally, discriminant validity was examined through the heterotrait–monotrait ratio (HTMT) [126]. As seen in Table 5, the size of the HTMT coefficients is below the recommended threshold of 0.80, indicating that the measurement model fits well and meets the criterion of discriminant validity [119,129].

Table 5.

Discriminant validity of measurement model—based on the HTMT ratio.

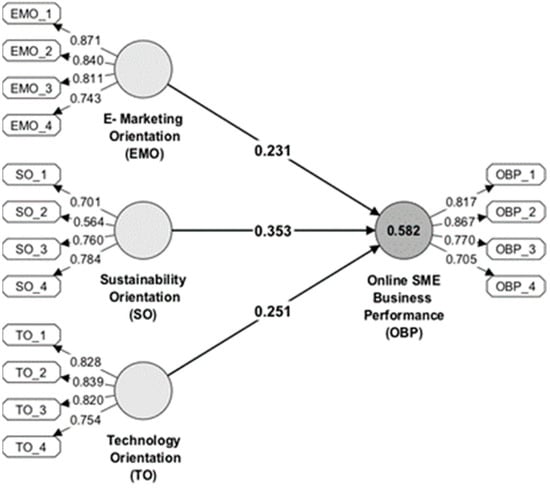

Figure 2 illustrates the standardized coefficients placed on the corresponding paths in the multidimensional model. Collinearity statistics (VIF), model fit (), criterion validity (GoF), and construct cross-validated redundancy () contributed to the evaluation of the proposed construct model [119].

Figure 2.

The results of multidimensional model.

All analyzed elements present variance inflation factor (VIF) coefficients higher than 0.25 [120] and lower than 4.00 [126]. Therefore, in the case of the proposed reflective measurement model, multicollinearity is not a problem (see Appendix A, Figure A1).

4.2. Structural (Inner) Model Results

The R-square value is 0.582 for the endogenous variable OBP, meaning that 58.2% of the variation in online SME business performance is explained collectively by the variables EMO, SO, and TO. Because the proposed construct model includes only three independent variables, the adjusted is 0.578, which is very close to the unadjusted . In Table 6, which also illustrates the sizes of the f-square effect, it is observed that the exogenous variable SO has a greater effect on the endogenous variable OBP than TO and EMO [130]. Achieving an SRMR of 0.074 (<0.80) and a goodness of fit (GoF) of 0.615 once again demonstrates a good fit of the reflective model [119,131]. Testing the statistical hypotheses was conducted by examining the structural model and assessing the significance of the paths between constructs. Using SmartPLS4 software, bootstrapping options were run, generating the specific values for significance tests (t-value) and their corresponding levels of probability (p-value). The most significant impact on OBP (β = 0.353, t = 6.381, p = 0.000) was observed for SO, supporting the null hypothesis H1₀. On the other hand, the exogenous variables EMO (β = 0.231, t = 3.369, p = 0.001) and TO (β = 0.251, t = 3.195, p = 0.001) had a slightly more moderate but positive and significant influence on the endogenous variable OBP, confirming the null hypotheses H2₀ and H3₀. As seen in Table 6, all three paths of the construct model are positive and significant at levels higher than t-value > 1.96 or p-value > 0.05 [119].

Table 6.

Results of the structural model.

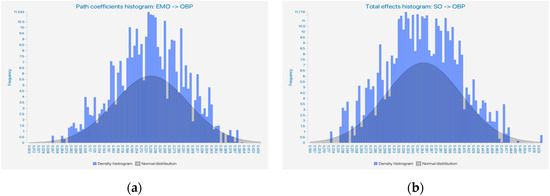

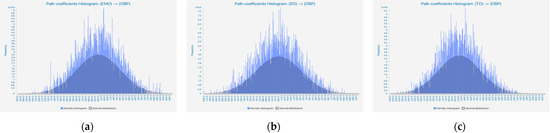

In Figure 3, three histograms can be visualized, illustrating the dispersion of estimated values between the iterations EMO → OBP, SO → OBP, and TO → OBP. For instance, histogram (b) below shows, for the path model from SO to OBP, a more complex distribution of path loading coefficients, unlike histograms (a) and (c).

Figure 3.

Path coefficients histograms: (a) the distribution of path loading coefficients for the model’s path from EMO → OBP; (b) the distribution of path loading coefficients for the model’s path from SO → OBP; and (c) the distribution of path loading coefficients for the model’s path from TO → OBP.

4.3. Moderating Effects of E-Commerce Intensity

PLS multigroup analysis (MGA) was employed to assess whether there are significant differences within the proposed structural model (PLS) among the e-commerce intensity groups in the paths EMO → OBP, SO → OBP, and TO → OBP. The sample was divided into two groups, namely, e-commerce intensity—under 500,000 €/year (EIU) and e-commerce intensity—over 600,000 €/year (EIO), subsequently testing the relationships between their paths.

Table 7 illustrates the separate path coefficients for the EIU and EIO groups, alongside bootstrap estimated standard errors, t-values, significance p-values, and confidence intervals. It is observed that the path coefficients in the structural model (interior) are higher for EIU (0.357; 0.274; 0.186) compared to EIO (0.018; 0.476; 0.371). In Table A2, the overlapping confidence intervals for the paths SO → OBP (EIU, ranging from 0.141 lower to 0.396 higher; and EIO, ranging from 0.287 lower to 0.646 higher) can be observed. Additionally, the confidence intervals for the path from TO to OBP overlap (EIU, ranging from −0.015 lower to 0.363 higher; and EIO, ranging from 0.104 lower to 0.620 higher). In both cases above, null hypotheses 2₀ and 3 are accepted (p-value < 0.05 or 0.001). However, there is a clear difference in path coefficients between the samples EIU and EIO for the path from EMO to OBP. The confidence intervals no longer overlap in the case of the EIO group, which means that, at the significance level of 0.05, the null hypothesis is rejected, and the alternative hypothesis 1₁ is accepted.

Table 7.

Results of PLS-MGA.

The difference between the path coefficients EIU vs. EIO was subjected to three tests, which implicitly utilize the significance level of 0.05 [132]. The non-parametric PLS-MGA significance test indicates that there is a significant difference in the case of “e-commerce intensity” for the specific path EMO → OBP, with a p-value less than 0.05 (p-value new = 0.016 < 0.05). The situation proves to be similar in the case of the other two tests (Parametric Test: p-value new = 0.015 < 0.05; and Welch–Satterthwait Test: p-palue new = 0.016 < 0.05). However, there is no significant difference regarding “e-commerce intensity” for the difference in path coefficients SO → OBP and TO → OBP, as indicated by all p-value columns in Table 8.

Table 8.

Differences between groups e-commerce intensity under 500,000 €/year (EIU) and e-commerce intensity over 600,000 €/year (EIO).

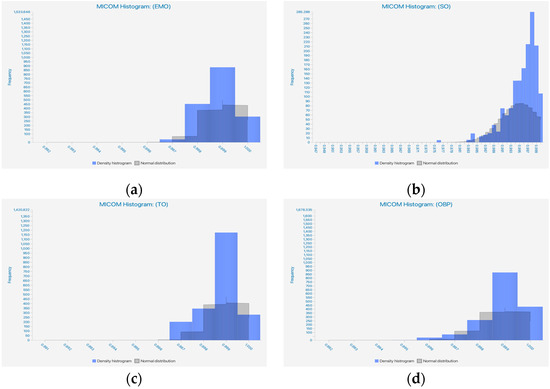

To compare the groups, the permutation algorithm was used (MICOM). The measurement invariance assessment (MICOM) was used to measure significant differences between groups due to other intergroup modifications in constructions [133]. The results of the permutation algorithm (5000 permutations) confirm that there is a significant difference between the groups of EIU and EIO for the path EMO → OBP in the structural model (interior), as the permutation p-value is below the accepted threshold of 0.05 (EMO → OBP has a permutation p-value of 0.020) [126]. Since the permutation p-values for the paths SO → OBP (0.085) and TO → OBP (0.268) are greater than 0.05, it can be concluded that there is no significant difference between the two groups (EIU and EIO) for these specific paths in the structural model (see Table 9).

Table 9.

Results of the structural model.

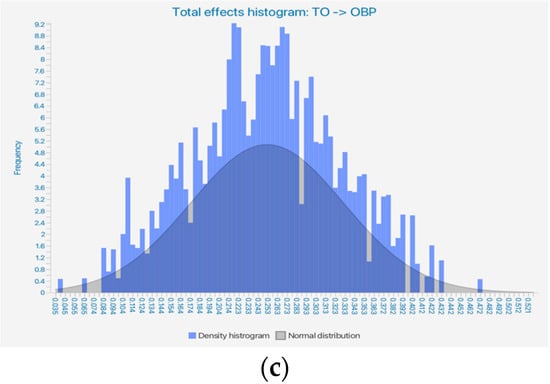

In Figure 4, the permutation process is illustrated through the three histograms for the paths EMO → OBP, SO → OBP, and TO → OBP. The results of the compositional invariance assessment (see Figure 3 and Appendix A—Table A3) showed that the 5% quartile was smaller than the original correlation (c) for the four constructs of the proposed model (EMO, 0.999 < 0.997; OBP, 0.999 < 0.997; SO, 0.998 < 0.986; TO, 0.998 < 0.997). Since the permutation p-values were greater than 0.05, it follows that all correlations are nonsignificant (EMO, 0.448 > 0.05; OBP, 0.433 > 0.05; SO, 0.800 > 0.05; TO, 0.160 > 0.05). Meeting these criteria, the results of MICOM Step 2 demonstrate compositional invariance.

Figure 4.

Permutation sample results for path coefficients of the structural model: (a) distribution of path coefficients after the permutation process for EMO → OBP; (b) distribution of path coefficients after the permutation process for SO → OBP; and (c) distribution of path coefficients after the permutation process for TO → OBP.

MICOM histograms for the four latent variables of the structural model are presented in Figure 5. Scalar invariance (equality of composite means and variances) (Step 3) is shown in Appendix A, Table A4. Initial differences between the mean values of latent variable scores were within the lower (2.5%) and upper (97.5%) limits. For instance, for EMO, the initial difference of 0.055 is included in the interval [−0.210; 0.239]. A similar situation is observed for the other variables (OBP, 0.089 ⊂ [−0.220; 0.214]; SO, −0.003 ⊂ [−0.209; 0.222]; TO, 0.045 ⊂ [−0.230; 0.230]). The permutation p-value tests for intergroup differences in means were greater than 0.05 for each internal model construction (0.419, 0.626, 0.660, 0.976 > 0.05). Additionally, the permutation p-values for intergroup differences in variances for all internal model constructions were also above the threshold of 0.05 (0.388, 0.495, 0.657, 0.814 > 0.05). Considering the above results, we can assert that there is complete measurement invariance [126,133].

Figure 5.

MICOM histograms: (a) for EMO; (b) for SO; (c) for TO; and (d) for OBP.

Finally, the results of the PLS-MGA analysis have shown that there is a significant difference between EIU and EIO due to the modification between groups in the EMO → OBP construction. For the SO → OBP and TO → OBP constructions, the PLS-MGA analysis does not indicate a significant difference between the analyzed groups.

5. Discussion

This study highlights some important findings. First, the results of this study show that EMO has a strong influence on OBP. The research results suggest that EMO ranks third among the three dimensions that significantly influence OBP. It seems that SMEs increasingly use e-marketing resources to achieve specific objectives, such as rapid and appropriate communication with the public, ensuring the continuity of traditional activities, stimulating commercial transactions, and conducting marketing activities as efficiently as possible.

Second, this study assessed the impact of SO on OBP. The results reveal that SMEs continuously develop partnerships with local suppliers and public institutions for the administration and financing of action plans related to social services and the achievement of social protection objectives. It seems that enterprises are increasingly concerned with the development of sustainability plans that include specific goals such as: job creation, the implementation of programs for personal and professional development, greening the enterprise, stimulating product and process innovation, expanding production and distribution markets, and others.

The effect of SO on OBP is the strongest compared to the other two variables. One possible reason could be that SMEs have observed that, following the implementation of sustainability plans, they achieve higher financial gains than the resources allocated for sustainable investments. This finding is consistent with [69,134,135], where enterprises not only perceive the social importance of sustainable business activities intensely but also demonstrate an increased interest in implementing sustainability plans.

Third, unlike previous studies [95,136], it is demonstrated that TO, following SO, has a strong positive impact on OBP. It is observed that enterprises are becoming interested in implementing technology and innovation policies and practices. Furthermore, they are developing comprehensive plans that include expanding and renewing advanced technological capabilities to gain competitive advantages, reducing pollution, enhancing communication and collaboration with technology providers and stakeholders, integrating new technologies for visibility, boosting sales, improving customer relationships, and implicitly developing technical and technological skills among employees, contributing to increased productivity and efficiency.

The proposed structural model is valid and robust, as demonstrated by the study results. With an R-square value of 0.582, it indicates that over half of the variance in the dependent variable online SME business performance is explained by the joint action of the independent variables EMO, SO, and TO. The values of the adjusted R-square (0.578) and GoF (0.615) further confirm that the proposed structural model is solid and strong. The existing literature does not highlight studies examining the common effect of exogenous variables EMO, SO, and TO on OBP. This study addresses this gap and proposes a new, unique model that may become more complex in the future by including other latent variables. All the results obtained in the study have been discussed solely from the perspective of research objectives, statistical hypotheses, and conducted tests.

5.1. Theoretical Implications

The study results show that all three correlations are significantly positive. The strongest effect on the endogenous variable OBP (β = 0.353, t = 6.381, p = 0.000) was exerted by the exogenous variable SO; therefore, the null hypothesis H1₀ was accepted. Although the slightly more moderate impact of the independent variables EMO (β = 0.231, t = 3.369, p = 0.001) and TO (β = 0.251, t = 3.195, p = 0.001) on the dependent variable OBP was close in intensity, it was still positive and significant. In this context, null hypotheses H2₀ and H3₀. were accepted. Therefore, all three paths of the structural model are positive and significant at levels above the accepted thresholds of t-value > 1.96 or p-value > 0.05 [119].

A multigroup PLS-MGA analysis was conducted between the e-commerce intensity groups—under 500,000 €/year (EIU) and e-commerce intensity—over 600,000 €/year (EIO) to test, based on the proposed structural model, that there are differences in the paths created by the proposed and measured variables. The results indicate smaller path coefficients in the structural model (interior) for EIO compared to EIU. Confidence intervals overlap for the paths SO → OBP and TO → OBP; therefore, null hypotheses 2₀ and 3₀ are accepted. The only difference arises in the correlation between EMO → OBP. In the case of the EIO sample, confidence intervals do not overlap, so, at a significance level of 0.05, the null hypothesis 1₀ is rejected, and the alternative hypothesis 1₁ is accepted. Additionally, the results of the PLS-MGA analyses, parametric test, and Welch–Satterthwait test indicate that there is only one significant difference in the EIO sample for the correlation path EMO → OBP.

Although enterprises continuously aim to maximize results and establish mutually beneficial relationships with market participants, the exploration of the three dimensions EMO, SO, and TO and their effect on OBP has been separately investigated [69,134,135]. This study responds to research demands by identifying items and deepening the understanding of factors contributing to the growth of the online business performance of Romanian SMEs, evaluating their common impact. In this context, the study provides several theoretical implications.

Primarily, it extends the existing marketing research literature by developing a new comprehensive multi-structural reflective model, enabling the highlighting of the extent of online SME business performance (OBP) changes under the joint action of EMO, SO, and TO factors. Our findings emphasize the importance and necessity of integrating EMO at the enterprise level to attract new businesses or expand existing ones; create, produce, and sell quality products and services; reduce production and distribution costs; and meet current and future consumer needs.

Second, the identification of new items and the measurement of the EMO variable contribute to the digital marketing literature and suggest that enterprises efficiently use e-marketing resources to communicate more easily with their target audience, ensure the continuity of traditional activities, stimulate the improvement of commercial transactions, and expand future marketing activities. Exploring how enterprises leverage their e-marketing resources to implement e-marketing strategies contributes to the resource-based view (RBV) theory, emphasizing the role of resources in gaining a sustainable competitive advantage. Ref. [137] argues that an enterprise’s sustained competitive advantage focuses on its resources, which are rare, valuable, inimitable, and non-substitutable. Enterprises with the ability to create or attract these e-marketing resources enjoy high performance and competitiveness compared to their competitors. Previous studies have focused on analyzing the change process for sustainability and the challenges faced by most enterprises [138]. Many studies have not considered the importance of sustainability goals [53,138,139]. This study addresses this gap by highlighting their essential role in guiding enterprises toward achieving ecological, social, and economic sustainability. These goals serve as a roadmap, setting clear objectives and directions for the integration of sustainable practices into various aspects of operations.

Third, by assessing the items of the SO variable, this contributes to expanding the literature on sustainability. Examining the extent to which enterprises support the achievement of human, economic, social, environmental, and climate development goals allows the identification of measurable elements against which their performance can be evaluated. The hypothesis underlying SO is rooted in the belief that enterprises should operate in a manner that considers the long-term impact of their actions on society, the environment, and the economy. This study highlights that, in addition to simply complying with regulations and profitability goals, enterprises should adopt a proactive commitment to addressing sustainability challenges and creating long-term value for multiple stakeholders.

Fourth, this study extends the literature on TO by integrating and evaluating new items specific to the variable, while also suggesting that enterprises attract “future-oriented entrepreneurs”, support “technological innovation adoption/development and diffusion”, train “customer-oriented technicians”, and facilitate the integration of “new employee technology orientation” to enhance long-term performance. Our findings highlight that a technology-oriented approach positively and significantly impacts customer loyalty [88], helps reduce salesperson role ambiguity [140], contributes to gaining a competitive advantage [141], serves as a catalyst for innovation [142], and contributes to overall business performance improvement [93]. The study results emphasize that SMEs should strategically and proactively embrace and leverage technological advancements to enhance operational efficiency, support innovation, gain a competitive advantage, and achieve overall business success.

Fifth, the study aims to contribute to existing literature by disaggregating business performance into four distinct categories: e-marketing performance, financial and consumer performance, social and environmental performance, and technology performance. Integrating these orientations provides a holistic approach to online business, ensuring that marketing strategies are not only technologically advanced but also socially conscious and customer centric. Through integrated strategies, enterprises can offer customers a more consistent and personalized experience, building stronger relationships and loyalty. Moreover, enterprises that efficiently integrate these orientations gain a competitive advantage by leveraging technology, data-driven insights, social engagement, and targeted marketing strategies to stimulate growth and adapt to market changes.

5.2. Managerial Implications

This study provides significant implications for Romanian online SMEs to continue integrating e-marketing orientation. The study results demonstrate that managers give the highest priority to using e-marketing resources to ensure communication with the target audience (EMO_1). High importance is attributed to resources needed for ensuring the continuity of traditional activities (EMO_2) and stimulating commercial transactions (EMO_3). Resources allocated to the efficiency of marketing activities (EMO_4) receive slightly moderate attention. The outcomes derived from the analysis of the EMO variable provide Romanian online SMEs with the opportunity to enhance the efficiency of e-marketing resource utilization for strategic development, customer focus, and overall business performance maximization. For example, managers could develop targeted marketing strategies, leveraging digital channels to reach specific audiences based on data-driven perspectives and segmentation. Focusing on e-marketing involves personalized interactions, tailoring messages and offers to individual customer preferences for increased engagement. Managers of online SMEs should carefully oversee the creation of digital content and campaign management, ensuring consistent messaging and brand representation across various online platforms. The efficient allocation of resources for the adoption and integration of digital tools, marketing automation, and analytics platforms can be crucial for the enterprise’s e-marketing strategies. Analyzing relevant indicators could enable managers of Romanian SMEs to measure the success of e-marketing initiatives and identify areas for improvement.

Managers of SMEs in Romania prioritize, above all, the achievement of environmental and climate goals (SO_4). This is reflected in their commitment to sustainability and responsible business practices. Managers agree that, by reducing the carbon and water footprint, achieving climate neutrality, recycling waste, using green energy sources, and protecting biodiversity, their enterprise contributes to environmental improvement. The second priority was given to social protection goals (SO_3). The surge in prices in recent years, ecological erosion, substandard food consumption, and the spread of infections such as COVID-19 are factors driving SME managers to develop collaborations with local suppliers and communities for the implementation of local social protection plans. Third, managers support the achievement of human resources development goals (SO_1). The integration of human resources plans and programs often leads to job creation, the promotion of health and safety at work, personal and professional development, support for gender equality, the cessation of discrimination against women, and others, contributing overall to improving the performance of online SMEs. Finally, managers confirm the importance of achieving economic objectives (SO_2). Without stimulating product and process innovation, improving the quality of products and services, expanding production and market channels, among other aspects, enterprises will not be able to maximize future business performance. For example, managers should incorporate sustainability goals into long-term strategic planning, ensuring that business decisions consider the social and environmental impact. Efforts should then be made to engage stakeholders (customers, employees, suppliers, and local communities) in communicating sustainability efforts, collecting feedback, and aligning interests toward sustainable practices. Additionally, managers should involve employees in sustainability initiatives, encouraging participation and fostering a sense of responsibility for sustainable practices. The need to establish sustainability metrics and benchmarks should not be overlooked, allowing for the measurement of progress and the continuous improvement of sustainability goals.

The research results demonstrate that managers strongly support “technological innovation adoption/development and diffusion” (TO_2). The rapid exchange of information and knowledge, expanding communication and co-operation with suppliers and other stakeholders regarding ICT usage, are high-priority activities for Romanian online SMEs. Supporting “future-oriented entrepreneurs” (TO_1) is another aspect highly appreciated by managers. The adoption and use of new technologies, strategic alignment through the implementation of technology and innovation policies and practices, and the development and exploitation of technological capabilities for sustainable competitive advantage are constant concerns of Romanian managers. The reduction in the birth rate, the intensification of migration, and the shortage of qualified and specialized workforce prompt Romanian managers to facilitate the integration and/or training of “new employee technology orientation” (TO_4).

Managers agree that only by improving the technical and technological skills of the human resources can the capacity to operate the enterprise’s equipment or technologies easily, quickly, and efficiently be enhanced. For example, managers should develop comprehensive digital transformation strategies aligned with business objectives, focusing on how technology can drive innovation and efficiency. Ensuring a robust technological infrastructure (hardware, software, and network systems) to support the enterprises’ operations and future scalability should be a priority for managers. The continuous analysis of technology-related indicators could enable managers to assess the impact of technology investments on online SME business performance. Furthermore, leveraging technology for innovation and efficiency can strategically position SMEs in the market, providing customers with unique technological capabilities.

5.3. Implications for Environmental Decision Makers

The integration of the three orientations at the level of online SMEs in Romania also has implications for environmental decision-makers, such as government organizations and regulators, non-governmental organizations, and corporate and business leaders. Regarding e-marketing orientation (EMO), government organizations and regulators should simplify and improve the regulatory framework for SMEs, encourage the application of practices and the use of e-marketing tools for communication with the target audience (EMO_1), and contribute to raising awareness about product quality, environmental regulations, and sustainability programs (EMO_4). Businesses should benefit from incentives for adopting new e-marketing technologies, such as integrating digital customer service, and participate in entrepreneurial programs that include the adoption of sustainable e-marketing practices (EMO_2). Government organizations could improve SMEs’ access to financing and online platforms to stimulate commercial transactions (EMO_3). Non-governmental organizations (NGOs) should collaborate with businesses to educate consumers about product quality and sustainable choices, as well as to raise funds online for the development of social and environmental projects. On the other hand, businesses in partnership with corporate and business leaders should analyze data to understand consumer needs and preferences, create innovative products, offer carbon-neutral transportation options, ensure sustainable packaging, and issue digital invoices and receipts.

Regarding sustainability orientation (SO), government organizations and regulators should provide funding to SMEs that invest in health and safety programs, personal and professional development for their employees, gender equality initiatives, and anti-discrimination policies (SO_1). To promote economic objectives (SO_2), they could offer innovation grants and subsidies to SMEs engaged in the development of sustainable products and services, as well as assistance in entering markets with sustainable products. To achieve social protection objectives (SO_3), government organizations should offer tax benefits to businesses that collaborate with local suppliers, invest in the local community, and contribute to the Romanian economy. Achieving environmental and climate objectives (SO_4) requires renewed involvement from government organizations through programs that incentivize businesses to achieve climate neutrality and protect biodiversity. Non-governmental organizations (NGOs) should partner with SMEs to run sustainability programs aimed at establishing strategic objectives, transforming business models, improving education and working conditions, reducing environmental impact, and more. Corporate and business leaders should collaborate with SMEs to develop eco-friendly products, expand into new markets by leveraging eco-certifications and labels, and meet sustainability standards and customer expectations.

Considering technology orientation (TO), government organizations and regulators should support “future-oriented entrepreneurs” (TO_1) by publishing regulations that encourage technological innovation and developing innovation hubs (innovation centers and technology parks). They should facilitate “technological innovation adoption/development and diffusion” (TO_2) by developing an information and communication technology (ICT) infrastructure for the rapid exchange of information and knowledge, and by creating platforms that promote collaboration between businesses, suppliers, and other stakeholders on sustainability initiatives. Additionally, government organizations should support all SMEs interested in training “customer-oriented technicians” (TO_3) by developing educational and vocational training programs on using emerging technologies, and certification programs that emphasize customer-oriented technological approaches and sustainability. To facilitate the integration and/or training of “new employee technology orientation” (TO_4), government organizations could offer grants and subsidies to SMEs that invest in developing technical and technological skills for new employees and develop online learning platforms that provide accessible and continuous training on new technologies. Non-governmental organizations (NGOs) could create support networks and forums where future-oriented entrepreneurs can connect, share ideas, and collaborate on sustainability projects. SMEs, in partnership with corporate and business leaders, should implement onboarding programs that familiarize new employees with the latest technologies and sustainable practices.

The study results demonstrate that online SMEs enjoy strong “financial and customer service performance” (OBP_1), followed by robust “e-marketing performance” (OBP_2). On the other hand, “social and environmental performance” (OBP_3) and “technology performance” (OBP_4) record positive yet slightly moderate results.

6. Limitations and Future Research Directions

This study involves several limitations that could provide new perspectives on future research directions. First, this cross-sectional study was conducted among SMEs in Romania, limiting the generalizability of the analysis. Future studies could include longitudinal research and broader samples of enterprises from different countries, contributing even more to the generalizability of the results.

Second, the questionnaire used in the research has a high degree of structure, contributing to limiting the level of detail in respondents’ answers and the lack of diversity in the scales used for questions. Third, the proposed structural model included only four latent variables. Future research should expand the construct model by including latent variables such as market orientation, sales orientation, product orientation, societal orientation, etc., and by extending the scope of activities, thereby enhancing its applicability. This would contribute to understanding how SMEs, on one hand, use resources, and organize production and sales, and, on the other hand, monitor the long-term impact of their processes, products, and marketing on society and the environment.

Fourth, the moderating effect of factors on the correlation paths between variables was not studied. Other research could include various moderators (e.g., size of enterprise, the company’s age on the market, sector of activity, volume of sales, etc.) and conduct analyses that demonstrate different perspectives on the findings.

Finally, this study focused on the positive aspects generated by EMO, SO, and TO. Some studies should explore potential challenges and negative aspects that enterprises may face upon their integration, namely, inundating consumers with excessive information, leading to information overload and fatigue; the rapid spread of negative feedback in the public domain that could damage brand reputation; and cyber threats that could disrupt operations, affecting customer experience and business continuity.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study does not require ethical approval.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement