Abstract

This research has undertaken a systematic literature review (SLR) of articles focusing on the acceptance of fintech payment services by identifying 84 peer-reviewed articles published in international scientific journals from 2015 to April 2023. This paper uses the Scientific Procedures and Rationales for Systematic Literature Reviews (SPAR-4-SLR) protocol to gather relevant articles and the theory, context, constructs, and methodology (TCCM) framework to analyse them. The conducted SLR has several findings. First, the Technology Acceptance Model (TAM) is the main theory used to examine consumers’ acceptance of fintech payment services. Second, studies in this area have been conducted in 24 countries, with a focus on Indonesia, Malaysia, and China. The study themes identified include fintech payment apps, Buy Now Pay Later (BNPL), mobile payment, fintech services, e-wallet, and Islamic Fintech. Third, the perceived usefulness, trust, perceived ease of use, and attitude are the four main constructs found to have a significant association with behavioural intention. Finally, most studies (64) rely on quantitative methods, particularly questionnaires. Based on the findings, this study identifies research gaps and provides a future research agenda. The review also has practical implications for policymakers and corporations in developing strategies and policies promoting the acceptance of fintech payment services. Limitations include B2C focus, exclusion of B2B behavior, lack of targeting specific user demographics, and reliance on secondary data. These present opportunities for further research.

1. Introduction

Embracing new technologies has a significant role in the finance industry, which has resulted in a massive increase in the productivity and reachability of its services to consumers [1,2]. The financial technology (fintech) phenomenon has appeared in economic science as a result of the increasing presence of technologies in the market of financial services [3]. Although the definition of fintech varies among scholars [4], fintech can be broadly defined as a service sector made up of companies that employ technology and innovations to improve the efficiency and accessibility of financial operations [5,6,7].

While fintech’s dynamic development is strongly linked to the early 1990s’ development of the Internet, the fintech revolution officially began with the widespread adoption of smartphones, which occurred after 2010 [3,8]. More importantly, since 2015, both the awareness and adoption of fintech services have witnessed a massive increase (from 16% in 2015, to 33% in 2017, and up to 64% in 2019) [9]. COVID-19 and the lockdown also played a crucial role in the increasing adoption of fintech services [10].

Despite the growing interest in fintech, there is still a lack of agreement among scholars and practitioners on its definition and theoretical foundations [6]. This might be due to the wide range of services and applications used within the fintech concept, which covers areas such as digital banking, payments, insurance, crowdfunding, asset management, and many others [5]. The importance and success of fintech services rely heavily on the perception of consumers towards accepting and adopting them [4]. Hence, consumers’ perception and their intention to use the fintech services and applications, and the factors affecting their behaviour, have all been of great concern in both practice and academia. Several researchers have been examining different factors that impact consumers’ perceptions towards adopting fintech services, in different contexts, and even relied on different theories in supporting their claims [10]. However, limited research has conducted a systematic review of consumer adoption of fintech payment services. For instance, ref. [6] provided a broad systematic review of fintech that encompassed all its services and products, but their study only covered the period before COVID-19. Ref. [11] conducted a review focused on digital financial technology adoption, including all its types, but only until 2020. Therefore, these studies do not cover the most recent developments in the quickly changing landscape of fintech. Moreover, given the need for policymakers and business providers to better understand consumers’ perceptions of fintech payment services, it is highly necessary to focus on one specific angle of fintech, i.e., fintech app payment services, and conduct a systematic review that includes recent studies up until April 2023. This will not only provide valuable insights for future research but also increase awareness and knowledge of this aspect of fintech. As fintech app payment services are highly relevant in both practice and academia, this paper aims to provide a systematic literature review (SLR) of their acceptance by consumers.

Studies using a literature review indicate that well-written SLR papers should follow a scientific procedure [12]. Therefore, the present paper continues in this trend by applying the “Scientific Procedures and Rationales for Systematic Literature Reviews” (SPAR-4-SLR) protocol [13]. Such an approach has not been followed widely in the literature review studies on the consumer adoption of fintech services (particularly the payment services). This paper is also distinctive as it follows the theory, context, constructs and methodology (TCCM) framework presented by [14] in its analysis and results. The current study is also unique in that it covers the period from the emergence of studies related to fintech payment services and consumer acceptance (i.e., 2015) until April 2023. Another contribution is related to the inclusion of a newly established fintech payment service, Buy Now Pay Later (BNPL). This service is one of the trending fintech solutions that have received recent attention in academic studies [15,16,17,18]. Due to its recent emergence, we found that there is no systematic review, until now, that has covered this fintech payment service. The current study includes this new fintech service and its acceptance by consumers in its review to provide a better understanding. Furthermore, the study contributes conceptually by identifying and summarizing the factors influencing the adoption and acceptance of fintech apps in payment services. As a result, the findings provide readers with identified gaps and suggest a number of future research directions and a future research agenda, particularly in relation to the enhancement of fintech payment services. Overall, the current paper aims to answer the following questions:

- RQ1:

- How many studies have been done relating to consumers’ adoption of fintech payment services?

- RQ2:

- What are the contexts used by researchers in previous studies?

- RQ3:

- What are the methods applied by researchers in previous studies?

- RQ4:

- What are the theories used by researchers in previous studies?

- RQ5:

- What are the factors that influenced consumers’ adoption of fintech payment services?

- RQ6:

- What are the recommendations for future studies in this field?

The rest of the paper is organized as follows: Section 2 describes the methodology used in this paper. Section 3 presents the results of the literature review. Section 4 discusses and analyses the results. Section 5 provides a future research agenda. Section 6 presents the research contributions, and Section 7 concludes the paper.

2. Methodology

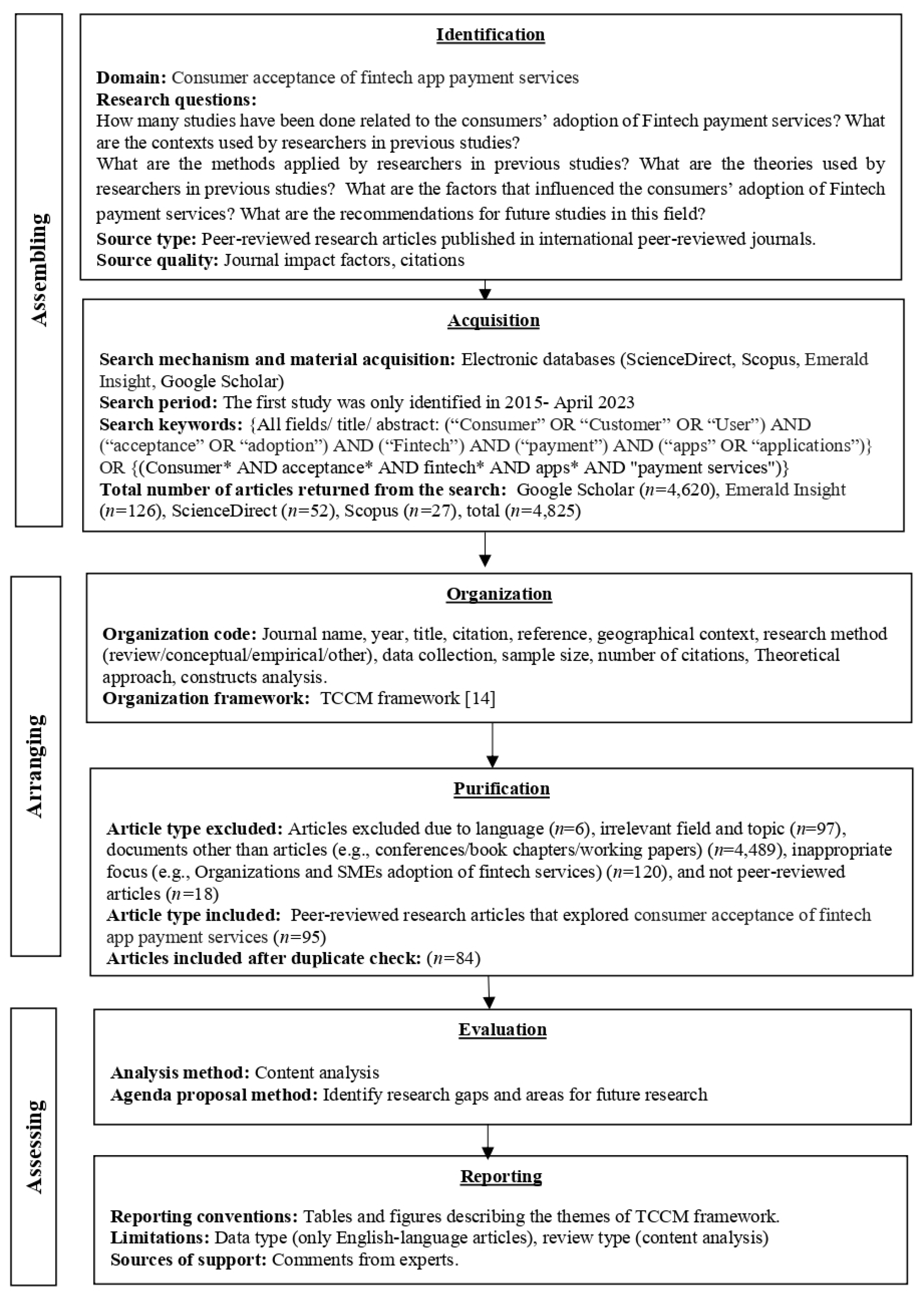

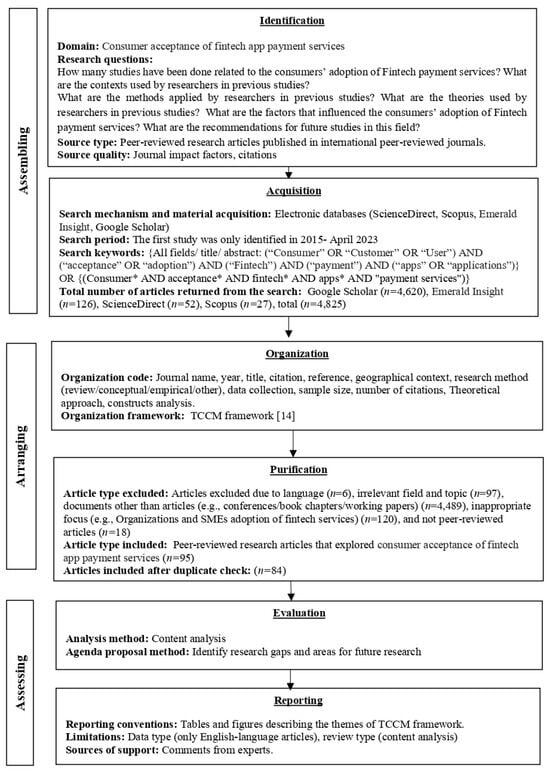

This study applied an SLR to observe the relevant existing literature on consumer acceptance of fintech app payment services in order to analyse the related body of literature. To achieve this goal, the researchers used the proposed protocol by [13], namely SPAR-4-SLR, to conduct the study in three stages (i.e., assembling, arranging, and assessing), as well as six substages (i.e., identification, acquisition, organization, purification, evaluation, and reporting).

This study, which was conducted in the beginning of May 2023, included all relevant studies up until April 2023, with no specified starting year. Based on the inclusion and exclusion of the identified articles, and due to the recency of the topic, the first study of fintech acceptance and adoption by consumers was identified in 2015, representing the modern nature of this topic. Figure 1 presents the flowchart with the three research stages, as well as the six substages to highlight the eligibility criteria and selection of the articles that are part of this literature.

Figure 1.

SPAR-4-SLR protocol. Note: the symbol * allows to search multiple variations of the keywords.

2.1. Assembling

The first stage of this research protocol is called the assembling section, which includes the identification and acquisition of the literature [13]. In the present study, the assembling includes the identification of previous research on the acceptance of fintech app payment services from the consumer’s perspective. This research focuses on peer-reviewed research articles published in international journals listed in electronic databases, including ScienceDirect, Scopus, Emerald Insight, and Google Scholar [19,20,21]. As examining fintech acceptance and adoption by consumers is recent, the first study was identified in 2015, with others following, up to April 2023. Furthermore, as the purpose of this study was to undertake a complete search aiming to develop the present literature and knowledge on consumer acceptance of fintech app payment services, a number of keywords were used in the search. In the first screening, we used the following keywords: (Consumer* AND acceptance* AND fintech* AND apps* AND “payment services”). This search was accepted in Google Scholar and Emerald Insight. However, ScienceDirect and Scopus do not accept the * symbol. Accordingly, a second screening was based on the following keywords: (“Consumer” OR “Customer” OR “User”) AND (“acceptance” OR “adoption”) AND (“fintech”) AND (“payment” OR “payment services”) AND (“apps” OR “applications”). The total number of articles returned from the search based on each database is as follows: 4620 from Google Scholar, 126 from Emerald Insight, 52 from ScienceDirect, and 27 from Scopus, making a total of 4825 articles. While ScienceDirect, Scopus, and Emerald Insight are reliable databases and have features that allow the researcher to limit the searching process to only peer-reviewed articles, Google Scholar helps in achieving a wider range of scholarly articles that are published by various renowned academic and scientific publishers, such as EBSCO, Springer Link, ProQuest, Taylor and Francis, SAGE, and many others. Using Google Scholar required a massive effort in the later stages in order to include only peer-reviewed articles and exclude other documents.

2.2. Arranging

The second stage of this research protocol is called arranging, which includes the organization and purification of articles by developing the eligibility criteria. In the organization subsection, the organization code was according to the journal name, year, title, citation, reference, geographical context, research method, data collection, sample size, number of citations, theoretical approach, and constructs analysis. This study followed the TCCM framework presented by [14].

In the purification subsection, a set of inclusion and exclusion criteria was decided before starting the search. The exclusion criteria were studies written in languages other than English (n = 6) and papers examining other fields of technology adoption (n = 97). Conferences, dissertations, working papers, and book chapters were also excluded from this study (n = 4489), as well as papers with inappropriate focus, such as organizations’ and SMEs’ adoption of fintech services (n = 120), and not peer-reviewed articles (n = 18). The study included peer-reviewed articles that explore consumer acceptance of fintech app payment services (n = 95). The final number analysed in this study after a duplicate check is 84 peer-reviewed articles.

2.3. Assessing

The last stage of this research protocol is called assessing, which includes the evaluation and reporting of the identified research in the literature [13]. In this paper, the researchers utilized content analysis and developed a review protocol to guide the content analysis of the collected articles on consumer acceptance of fintech app payment services. The review protocol was adopted from [22] (see Table 1). This protocol involved an initial analysis to gain overall insights before conducting a thorough review and structuring the relevant literature. The collected papers were classified using a single category for each dimension, and then content was analysed through descriptive analysis based on specific key characteristics: author(s), journal name, publication year, title, geographical focus, aim and goals, major themes, type of research article, data collection method, sample size, data analysis method, theoretical approach, dependent variables, main findings, and number of citations. We reviewed ten articles to ensure inter-rater reliability and reach a consensus on their classification, and also presented the study to another group of academicians to validate it and incorporate feedback. To enhance maximum inclusion and coverage of the existing literature, we used the snowballing technique but did not find a significant increase in new cases, further confirming the validity of our initial research.

Table 1.

Review protocol.

The research gaps and areas for future research were then identified, based on the TCCM framework [14]. To report the results, tables and figures describing the themes of the TCCM framework were presented in the results of the conducted review. The study reported some limitations, i.e., articles were only in English, and the analysis method was limited to content analysis.

3. Results

The results of the reviewed articles are presented in this section, following the TCCM framework [14]. Prior to that, overviews of the publication year trends and numbers of citations are presented.

3.1. A General Overview of the Results

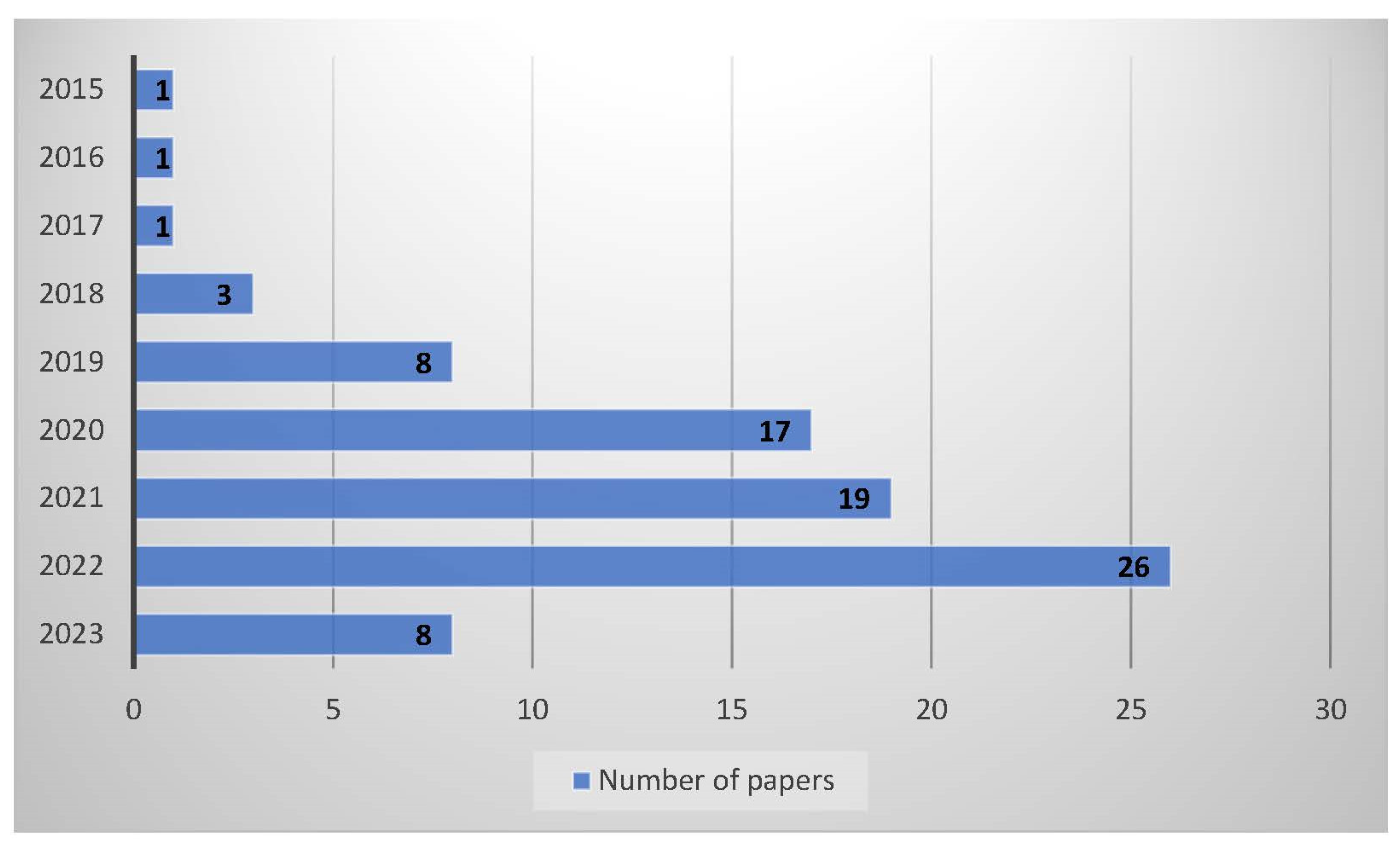

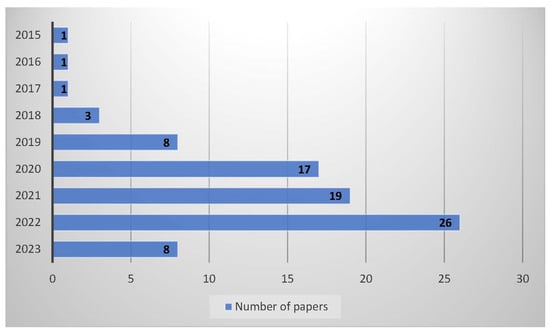

Based on the collected articles, the year-wise distribution (Figure 2) shows a significant increase in the number of papers focusing on the acceptance of fintech payment services, where the year 2022 shows the highest increase. This growing trend signifies the importance of the topic in academia.

Figure 2.

Year-wise distribution of papers.

Table 2 presents an overview of the top ten cited articles. The table is divided into the reference, journal, title, and number of citations as per Google Scholar (extracted on 3 May 2023). In terms of number of citations (Table 2), the top three cited papers are those published by [23,24,25].

Table 2.

The ten most cited studies (Extracted 3 May 2023).

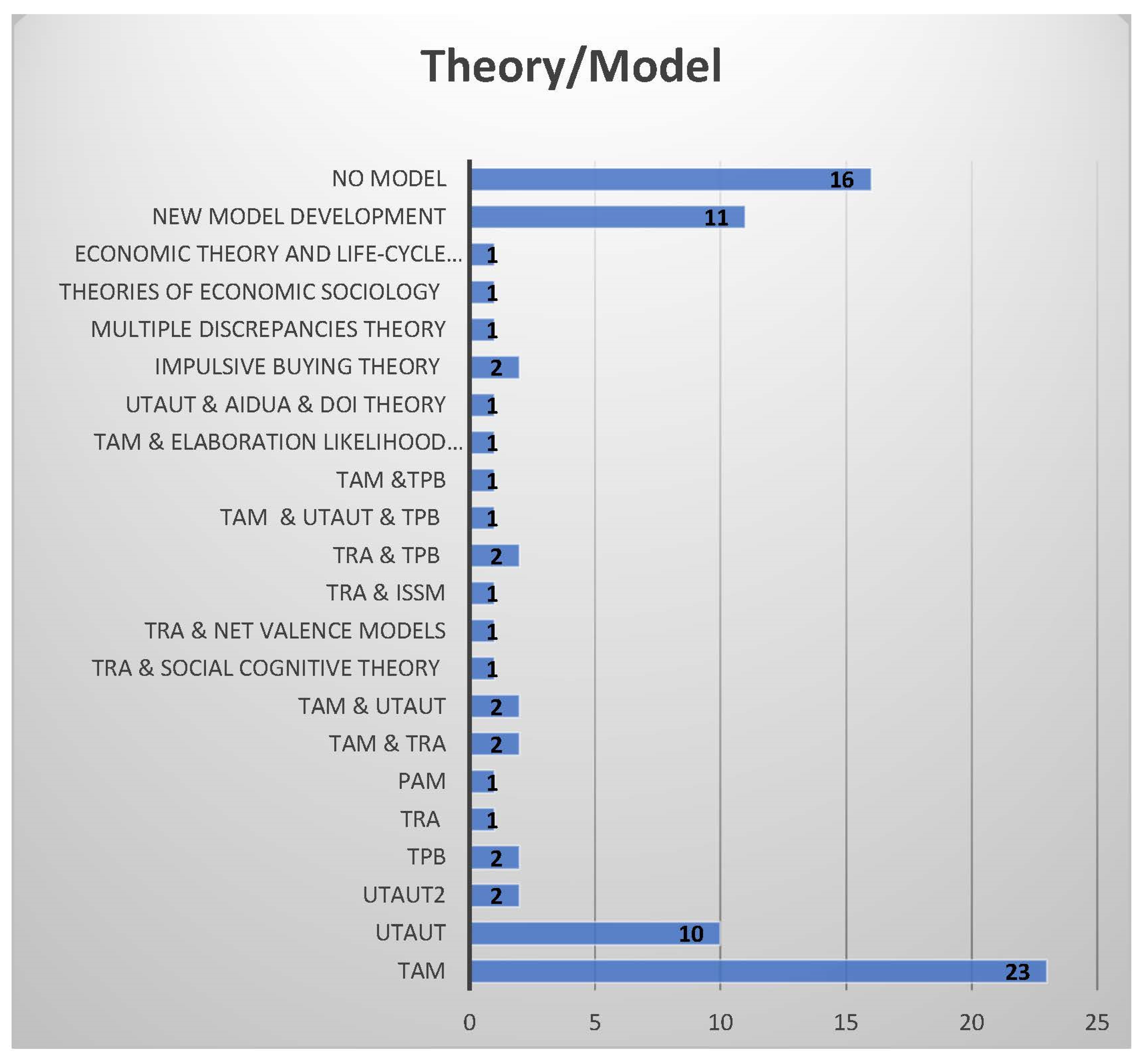

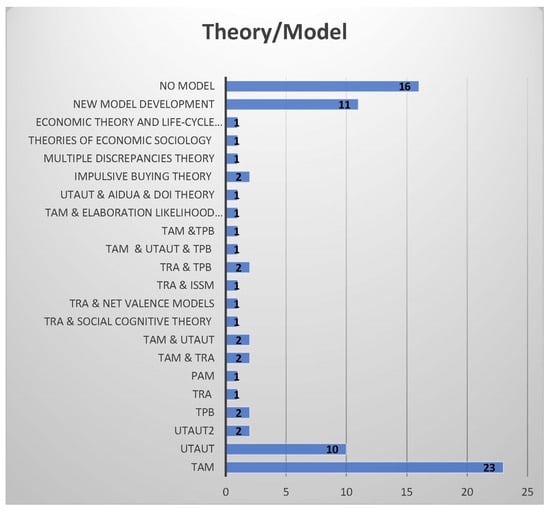

3.2. Theories (T)

As per theories or models identified in the reviewed literature (Figure 3), it can be seen that most articles (23) relied on the Technology Acceptance Model (TAM). The Unified Theory of Acceptance and Use of Technology (UTAUT) is also widely considered (10 times), and its extension (UTAUT2) is also used by two studies. Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB) and Theory of Reasoned Actions (TRA) are seen to be combined with other theories when used (nine articles did this). Sixteen articles did not have a theory or model at all, while 11 articles tended to develop a new model. The usage of the impulsive buying theory emerges in 2020 (two articles). Some theories, such as the Economic theory and life-cycle model, multiple discrepancies theory, theories of economic sociology, social cognitive theory, and post acceptance model (PAM), have each only been used in one article.

Figure 3.

Frequency of theories/models. Note: TAM = Technology Acceptance Model, TRA = Theory of Reasoned Actions, TPB = Theory of Planned Behavior, UTAUT = Unified Theory of Acceptance and Use of Technology, UTAUT2 = an extension of UTAUT, PAM = Post Acceptance model, ISSM = Information System Success Model, AIDUA = Artificially Intelligent Device Use Acceptance framework, and DOI = the Diffusion of Innovation theory.

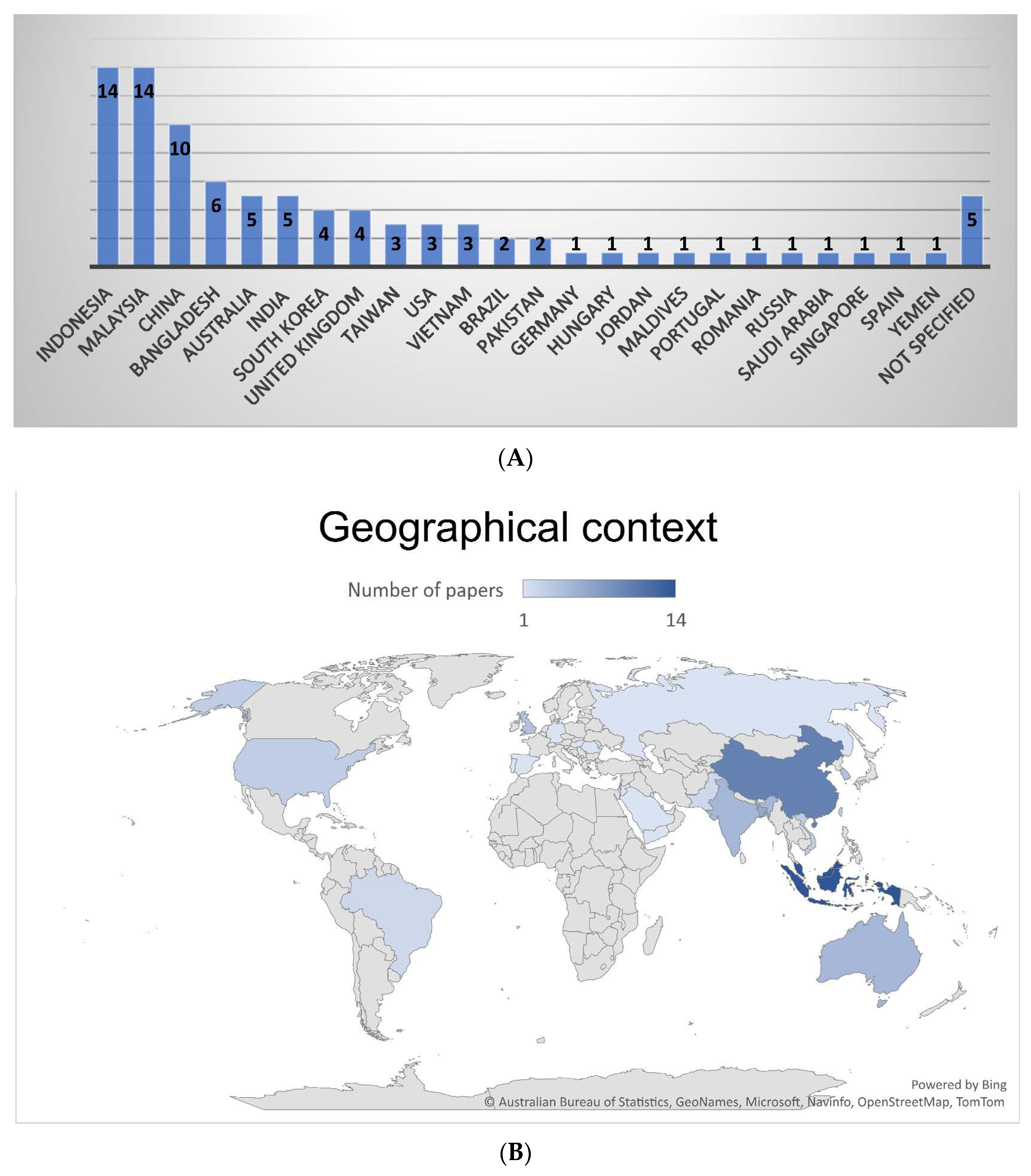

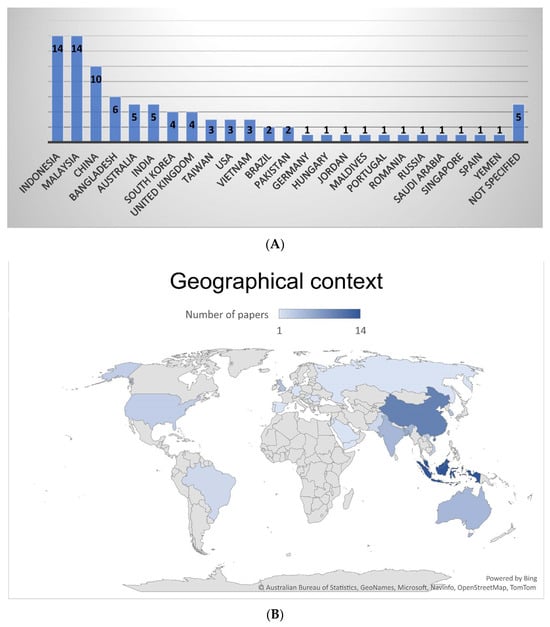

3.3. Context (C)

The geographical context of the reviewed articles is presented in Figure 4A,B. As shown in Figure 4A, the highest number of papers were produced in Indonesia and Malaysia (14 articles each), followed by China (ten articles). Other commonly considered countries are Bangladesh (six articles), followed by Australia and India (five articles each), the United Kingdom and South Korea (four articles each), and USA, Vietnam, and Taiwan (three articles each), while Brazil and Pakistan have two articles each. Other countries have been considered just once: Germany, Hungary, Jordan, Maldives, Portugal, Romania, Russia, Saudi Arabia, Singapore, Spain, and Yemen. Overall, as Figure 4B illustrates, most of the studies are concentrated in Southeast Asian countries.

Figure 4.

(A) Geographical context. (B) Geographical context on the world map.

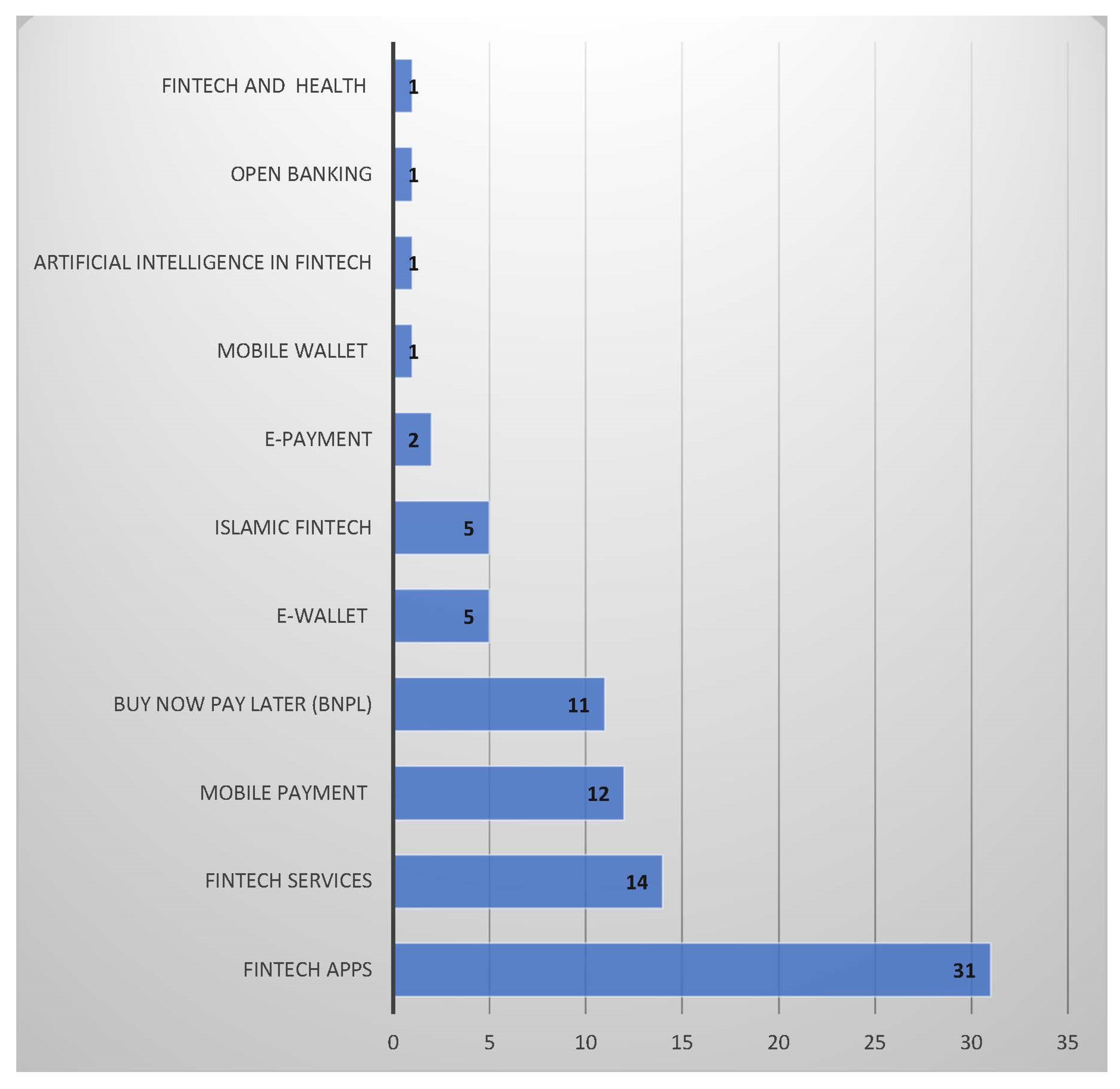

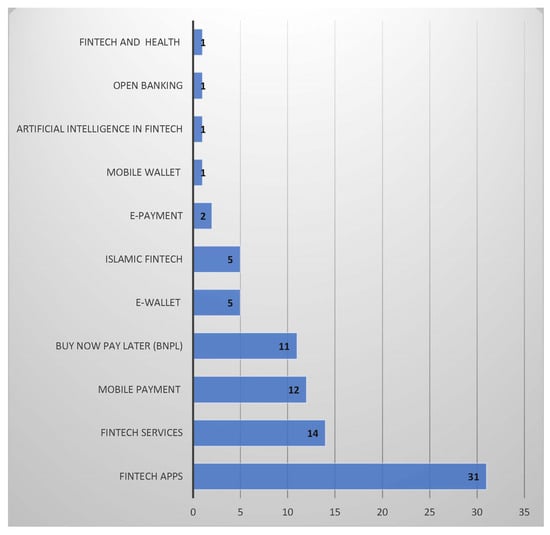

In terms of the context, based on the research theme/topic of the paper, Table 3 presents the identified themes within the fintech application adoption context and the references. Furthermore, Figure 5 shows that most of the articles (31) have considered the fintech apps without specifications; 14 have examined fintech services; 12 have studied mobile payment; and 11 recent articles have focused on the BNPL payment services. E-wallet and Islamic Fintech have also been an area of focus by five articles each. E-payment was considered twice, while the remaining themes (Fintech and Health, Open Banking, AI Fintech, and Mobile wallet) have appeared only once.

Table 3.

Research themes.

Figure 5.

Number of papers by theme/topic.

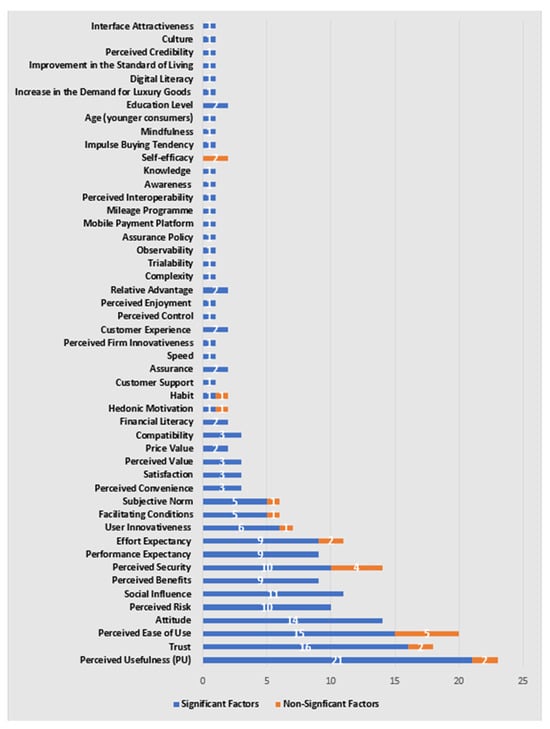

3.4. Construct (C)

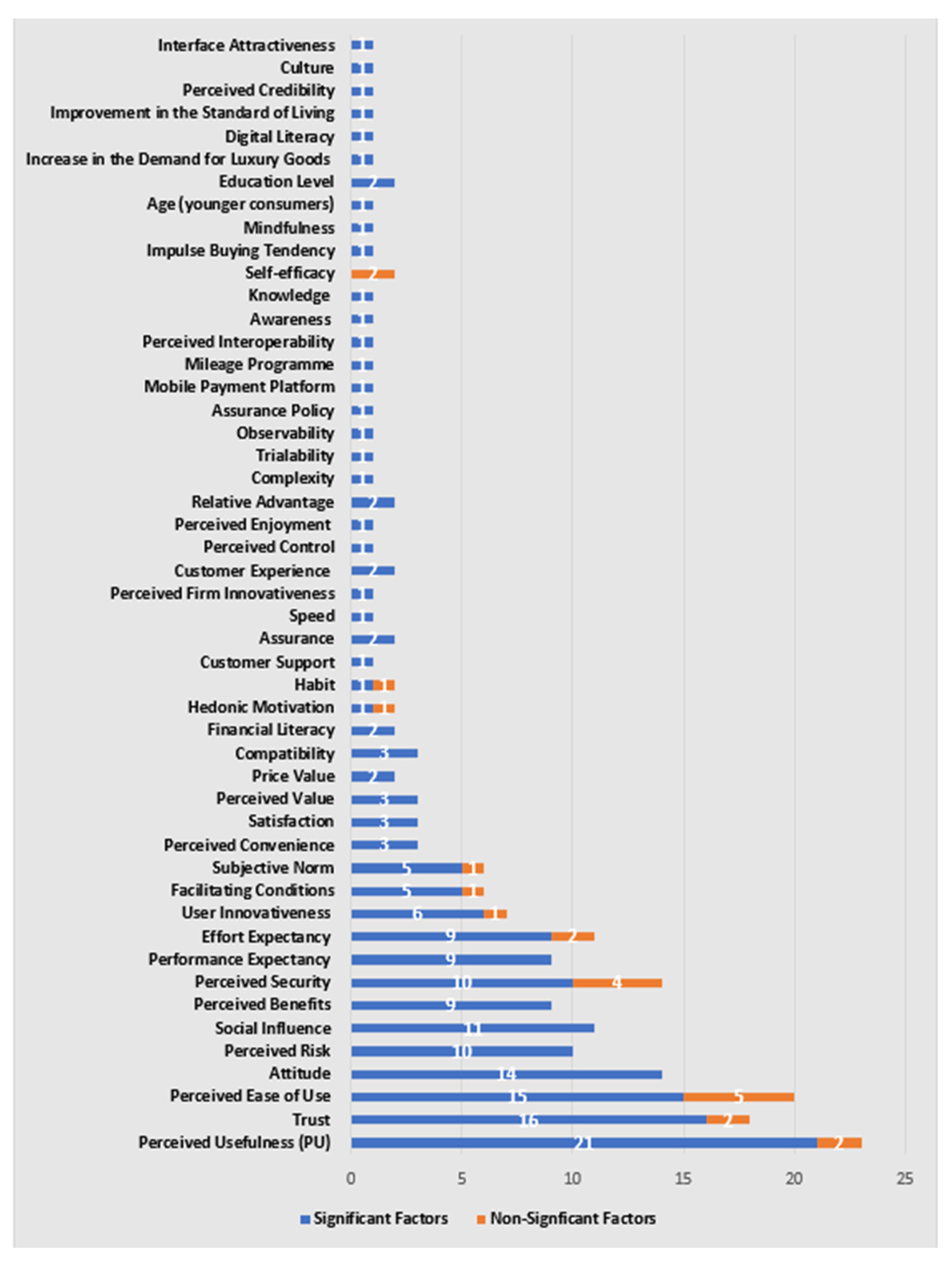

The literature shows a number of constructs (49) that have been significantly associated with the acceptance of fintech payment services (as a dependent variable), with behavioural intention as an independent variable; these constructs are presented in Figure 6. The factor that has been examined most in the reviewed literature and been found to have a significant association with fintech payment services is perceived usefulness (21 times); only two papers found that this factor does not have a significant impact. Trust is the second highest significant factor in the acceptance and adoption of fintech payment services (16 times); again, only two papers did not support such results. The third most examined construct is perceived ease of use (15 times); although five articles claimed the opposite results. Fourteen studies found significant association between attitude and behavioural intention. Eleven studies have examined social influence and found it to be significant in the fintech adoption context. Both perceived risk and perceived security were shown to be significant by some studies (ten times for each factor). Performance expectancy, effort expectancy, and perceived benefits are also commonly examined factors, where most papers tested them (nine articles for each) and supported their significance; only two articles found effort expectancy to be not significant. Figure 6 presents all the factors that showed a significant association with the acceptance and adoption of fintech payment services, where each factor is classified as supported if the factor is found to be significant, and not supported if it is insignificant. Table 4 presents the 17 factors that have been examined in the adoption of fintech payment services, with citations for the supported and not supported factors.

Figure 6.

Number of significant and non-significant factors identified in the literature.

Table 4.

Top 17 factors affecting adoption of fintech payment services.

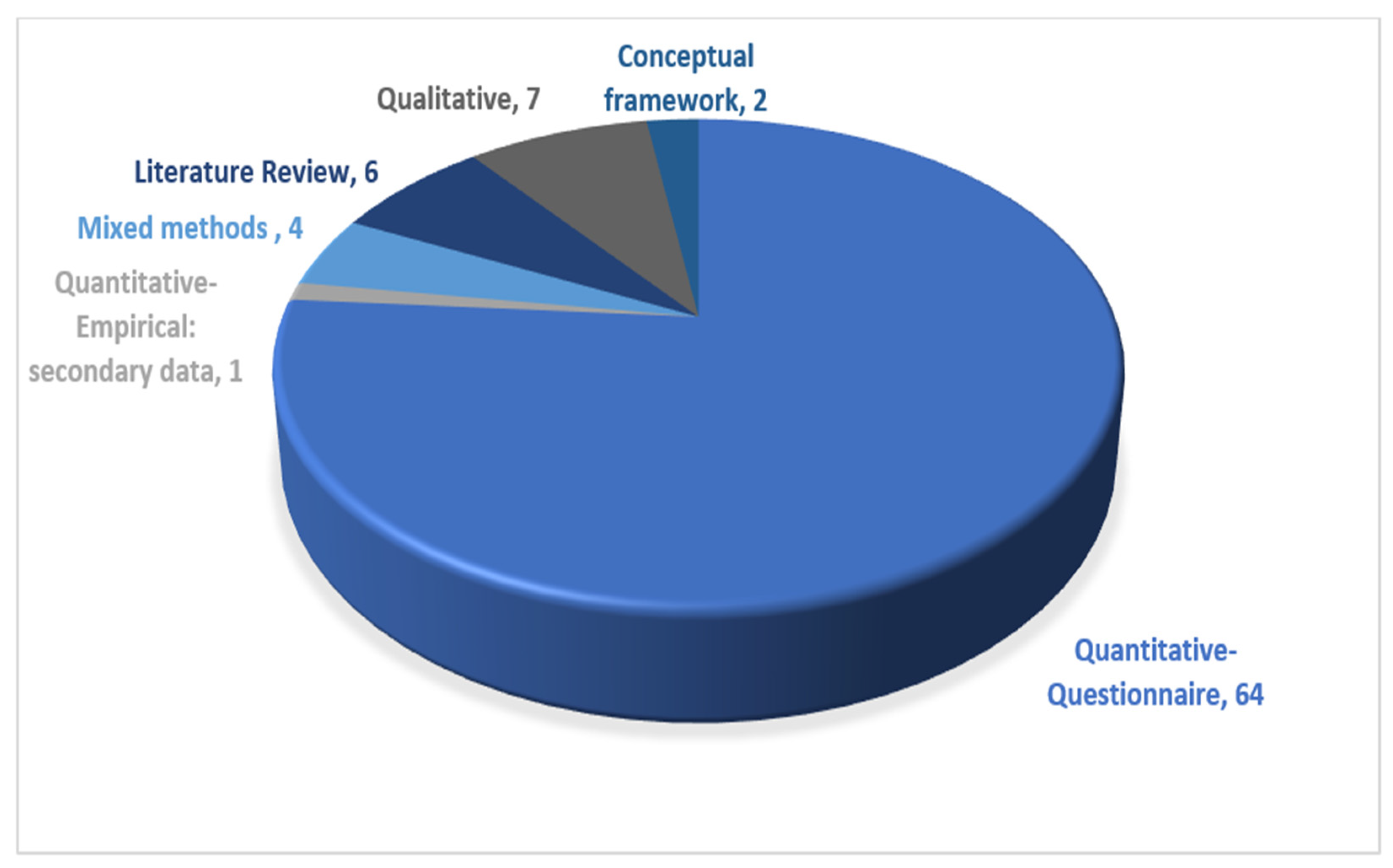

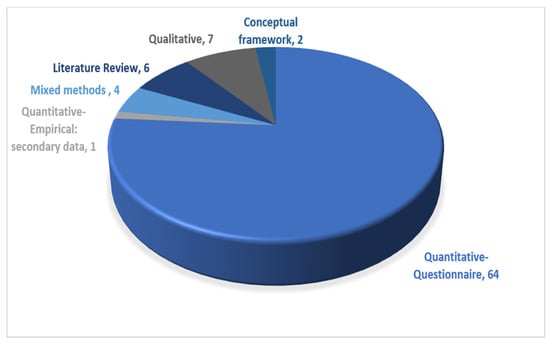

3.5. Methods (M)

The methods used in the reviewed studies are summarized in Figure 7. It can be seen that most of them used a quantitative approach, particularly primary data/questionnaire (64 times). The results also show that seven articles used a qualitative approach, and six applied a literature review approach. The mixed method approach was used by four articles. Only one article in the reviewed literature relied on secondary data, and one applied a conceptual framework. Table 5 provides more details of the papers’ citations, divided based on the research methods used. Most articles have used Quantitative (Questionnaire), followed by Qualitative (Content Analysis) and Literature Review. A few papers utilized Mixed Methods (Questionnaires and Interviews), and two studies utilized a conceptual framework.

Figure 7.

Research methods used in the reviewed papers.

Table 5.

Widely used research methods.

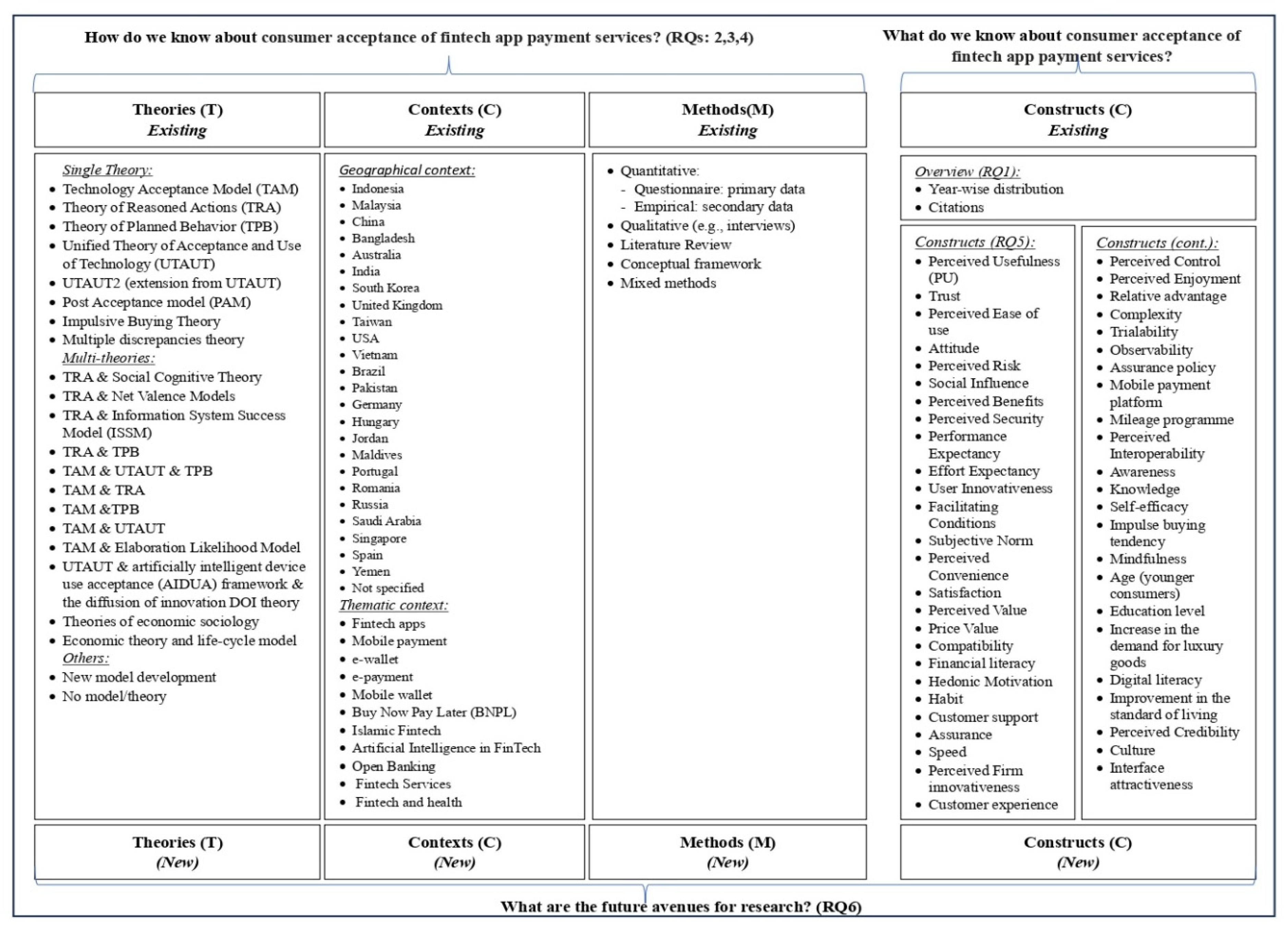

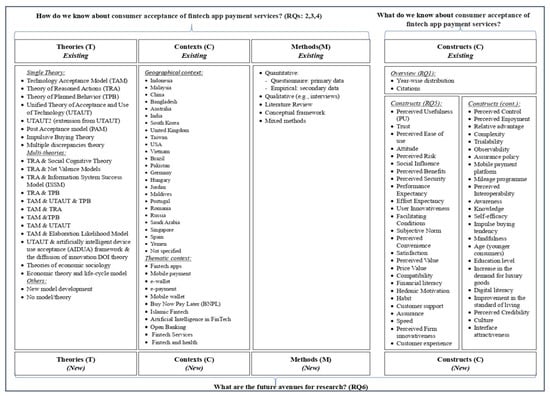

The results discussed in this section have been incorporated into a comprehensive framework, based on [98] and others, which is presented in Figure 8.

Figure 8.

A comprehensive TCCM framework.

4. Discussion

This section discusses and analyses the results of the previous section, and hence answers the research questions. RQ1 was addressed by applying an SLR to observe the relevant existing literature on consumer acceptance of fintech app payment services. To achieve this goal, the researchers used the proposed protocol by [13], namely SPAR-4-SLR, to conduct the study in three stages (i.e., assembling, arranging, and assessing), as well as six substages (i.e., identification, acquisition, organization, purification, evaluation, and reporting). The study was conducted without specifying a timeframe, up to April 2023. Based on keyword searches and the inclusion and exclusion of the identified articles, 84 peer-reviewed research articles were identified that are published in international journals listed in electronic databases including ScienceDirect, Scopus, Emerald Insight, and Google Scholar from 2015 to April 2023 [19,20,21]. After that, an analysis of the geographic distribution of the published articles was used to address RQ2. The results indicate that 24 countries have been considered when examining the acceptance of fintech payment services. Most of the studies are in Indonesia, Malaysia, and China. A possible reason for the high attention in these countries is the high level of fundraising in this sector by investors who have paid great attention to fintech. Moreover, the young, unbanked population in these countries has fuelled an increase in fintech adoption [99]. Additionally, governments’ motivations and efforts in developing a qualified infrastructure for fintech payment services in these countries might be another reason for the higher adoption by consumers. However, fintech payment services are highly supported by other countries’ governments and are used by consumers in their daily lives. Hence, further countries need to be considered and examined. RQ2 was also addressed by another context classification, i.e., the theme/topic of the identified studies; the results indicate that most of the studies have not specified a certain fintech payment service or app. This might be in the hope of more generalization of the results. However, this is a fast-growing sector, and many services and apps options are being released, which signifies the importance of greater specification. Although the BNPL theme is very recent (2020 onwards), it is receiving attention from academia, as 11 articles considered this theme. The Islamic Fintech theme is also considered by some articles, given that fintech is highly considered in Malaysia and Indonesia, which are both Islamic countries. RQ3 was addressed by analysing the methods applied by researchers in previous studies. Most of the studies relied on primary data (questionnaire). A possible reason for this is that fintech payment services are considered to be emergent, therefore reaching the users through questionnaires can reflect their insights and perceptions. However, there is a clear need for secondary data analysis, as consumers’ perceptions might differ from one country to another, and secondary data can be a better approach to generalizing the results. Moreover, the mixed-methods approach is rarely used, though it can actually provide a more thorough understanding. A conceptual framework was used only twice, although it, too, can provide a better understanding of this recent topic. The analysis of theories used by researchers in previous studies (addressing RQ4) indicates that a limited number of theories and models have been used when examining the acceptance of fintech payment services, mostly TAM and UTAUT. The high usage of these two theories might be due to their significance and popularity in examining technology acceptance and the adoption of new and modern technologies in different contexts [100]. Hence, many researchers adopted TAM or UTAUT, and some added a few constructs to those in the adopted theory. The analysis also shows that many of the studies did not specify any theory or model (16 times), while a few of them incorporated two or more theories. The limited number of papers that used a combination of theories might be due to the complexity of building such a combination with logical reasoning. The analysis of theory trends since the emergence of fintech services reveals that in the initial years of 2017–2018, the primary focus was on applying the TAM as the theoretical framework. Subsequently, in 2019, scholars increasingly utilized UTAUT. From 2020 onwards, researchers began to explore other theories and models such as the TPB and the TRA. Additionally, some researchers have sought to integrate multiple theories in their efforts to gain a more nuanced understanding of consumer acceptance of fintech services. Nevertheless, TAM and UTAUT also have still been used in recent years, with additional constructs. Understanding the evolution of theoretical trends in the field of fintech adoption can be highly beneficial for marketers and the banking industry. This knowledge can help them develop effective strategies, stay up to date on emerging frameworks, and enhance consumer engagement.

The factors (constructs) that influenced consumers’ adoption of fintech payment services have been analysed to address RQ5. Many of the studies focused on certain constructs, such as the perceived usefulness, trust, perceived ease of use, attitude, perceived risk, and social influence; however, consumer innovativeness, financial literacy, and awareness have rarely been considered. Furthermore, other moderating factors need to be examined, such as age, gender, income, and educational level, in the adoption of fintech payment services. Those constructs and moderators need further examination to reflect a better understanding and provide a greater potential of the generalization of their influence on the acceptance of fintech payment services. The findings and the discussion provided in this paper have several practical implications, which are discussed below.

4.1. Managerial Level Implications

The study shows that usefulness and ease of use are two of the most significant determinants of adopting fintech payment services by consumers. Hence, at a managerial level, fintech service providers (i.e., telecom companies, financial institutions, and online retailers) need to ensure that their fintech products are both user-friendly and useful. To improve usability, service providers should conduct user testing to identify and address pain points and optimize their products’ features and design. They can also provide user-friendly tutorials and customer support to enhance the user experience. Trust was also found to be an important factor that influenced the adoption of fintech payment services. Therefore, it is imperative for fintech service providers to implement innovative features that foster trust, such as gamification and social referral systems. Additionally, these service providers must not only prioritize the security of their services but also communicate and accentuate the security features to consumers in order to build trust and credibility.

4.2. Policy Implications

For policymakers, factors such as social influence and awareness need more attention. Several countries’ governments are investing heavily in developing their fintech services but awareness by consumers about these services is still missing. Hence, governments need to consider investing in creating fintech awareness. Moreover, the diffusion of digital financial services is more significantly influenced by regulatory and general market conditions [101]. Hence, governments of countries with limited adoption of fintech services should consider improving their infrastructure and regulations to promote the usage of fintech services. Finally, policymakers may have an essential role by applying regulations requiring certain criteria (i.e., ease of use, security, preserving the consumers’ rights) for the fintech services’ providers in order to increase the adoption of these services.

4.3. Academic Research Implications

This paper provides researchers with detailed information about consumer acceptance of fintech payment services and the gaps found in the literature. This information allows them to better understand the various theories, methods, and constructs that have been examined and are currently available in the literature. Furthermore, this study identifies the research gaps in the literature and provides research directions that academic researchers can consider as bases for future research.

5. Research Gaps and Future Research Agenda

The acceptance of fintech app payment services is receiving growing attention, which opens the door for future research. This section answers RQ6 by providing recommendations and opportunities for future research investigations based on the gaps identified in the reviewed literature. Following [14], these recommendations are classified based on the TCCM framework.

5.1. Theories—Future Agenda

It was found that most studies relied heavily on certain theories (e.g., TAM, UTAUT, TRA, TPB) when investigating the consumer acceptance of fintech payment services. Other multi-discipline theories can be applied to provide a better understanding. This is particularly important, as fintech services are innovative and develop quickly, and the consumer acceptance behaviour includes different aspects (e.g., socio-political, psychological). Hence, applying more recent theories that incorporate different aspects is essential. For instance:

- Most of the studies have examined technology acceptance theories and models in the fintech adoption context. This includes TAM and UTAUT. Future research could combine these theories with other models, such as The DeLone and McLean Model of Information Systems (IS) Success Model [102], to provide a better understanding of the most significant factors that affect fintech adoption by consumers.

- The electronic Word of Mouth (eWOM) theory is considered a multi-disciplinary theory that combines sociology, marketing, and IS literatures. Ref. [103] found that there is an association between eWOM and consumers’ purchasing intention. Hence, examining the eWOM impact or association with the acceptance of fintech app payment services can be considered in future research.

- The impulsive buying behaviour theory has been employed by some recent studies, particularly on the BNPL service e.g., [17,44]. Studies on other themes (i.e., e-wallet, mobile payment) have also considered this theory. Future studies can examine consumers’ acceptance of one of the fintech app payment services based on impulsive buying behaviour. This is particularly important, as the world is becoming a cashless society and fintech payment services may stimulate impulsive purchasing behaviour.

- Understanding the acceptance of fintech payment services is complicated, as it includes different stakeholders. Hence, future researchers are advised to develop new models that incorporate moderating and mediating effects for better understanding [56].

5.2. Context—Future Agenda

In terms of geographical context, the literature shows that many studies depended heavily on Southeast Asian countries (Indonesia, Malaysia, and China). Few studies have considered India and no study has been conducted in South Africa, based on the reviewed literature, although these countries are considered at the top of the list of consumers fintech adoption [9]; therefore, this study suggests:

- Conducting more studies targeting countries other than the widely investigated ones. The MENA region is also one of the areas that have not been considered, although some of its countries’ governments (i.e., Saudi Arabia) have injected massive investments into fintech services. Hence, those countries can be considered in future research. Moreover, EU countries have been considered by a very limited number of studies, though some EU countries can be potential contexts for future studies (e.g., France, Sweden, and Austria).

- In terms of demographic context, most of the studies focused on young adults (Millennials) [10,29,92]. Older adults (above 50) commonly have different preferences, and this segment is highly neglected in the literature. It is recommended that future studies examine the challenges faced by the older generation (above 50) in accepting the usage of fintech payment services.

- Additionally, there is different technology acceptance behaviour between male and female consumers. Very few studies have considered the difference between male and female acceptance of fintech payment services e.g., [74]. Future studies are encouraged to differentiate between the acceptance of fintech payment services between males and females.

- Furthermore, variation in education level has not been considered widely, i.e., only considered by [17]. Future studies may consider how different educational levels influence the acceptance of fintech payment services.

- In terms of the themes/topics, it was found that the majority of studies have examined the fintech apps as a whole, with no specification of a certain app or payment service. Future studies may consider specification and focus on examining the acceptance of a particular fintech payment service. For instance, the BNPL is one of the themes that can be highly considered in future research, particularly using a quantitative approach for testing the factors influencing the consumer acceptance of the BNPL mechanism. To the best of our knowledge, only [17] examined some factors in Dhaka city (Bangladesh). Hence, this theme can be highly considered in the future.

5.3. Construct—Future Agenda

In terms of construct (characteristics), based on the reviewed literature, limited studies have examined the factors of accepting the BNPL theme of fintech payment services [17,44,47,50], as well as the impulsive buying behaviour of e-wallet adoption. Accordingly, there are massive numbers of factors that can be examined with regard to the acceptance of these contexts; future research directions include:

- Examine the factors that have been considered in other fintech payment services acceptance in the BNPL context (i.e., perceived usefulness, trust, perceived ease of use, perceived security, perceived convenience, awareness, etc.) (Figure 6 gives more factors).

- Impulsive buying behaviour can be a factor to be studied in e-wallet and mobile payment acceptance, especially as these themes have a low number of articles, based on the reviewed literature. This factor is essential, as some studies argue that once an individual puts money into his/her e-wallet, it is regarded as spent [104]. Hence, consumers may believe that e-wallet money must be spent (impulsive buying behaviour).

5.4. Methods—Future Agenda

Based on the reviewed literature, many of the studies were conducted using primary data and quantitative analysis, which may limit the usability of the results in different geographical contexts [11].

- Future research may consider secondary data, for instance, using the number of transactions by each fintech payment service provider [16]. More importantly, secondary data can be used in examining causality between some factors and consumer acceptance of fintech payment services by applying Difference-in-Differences (DiD) tests.

- It was also noticed that use of a qualitative approach is very limited; hence gathering an in-depth understanding of consumers’ beliefs and experience is recommended. In such cases NVivo and other tools can be utilized.

- A mixed-methods approach is rarely used in the reviewed literature. While it is a more complex approach, it can be considered in future research, as it provides a thorough understanding of consumers’ acceptance.

6. Research Contributions

During the literature review process, it was observed that some previous systematic review studies had addressed the topic of fintech [6,105,106,107,108]. However, the current study offers a unique perspective. For example, ref. [6] conducted a systematic review of many fintech services before the COVID-19 pandemic. In contrast, this study focuses solely on the literature related to fintech payment apps, including newer services such as BNPL, up until April 2023. Similarly, ref. [105] only reviewed research up until 2019, while the current study includes more recent research, resulting in a more up-to-date understanding of the fintech landscape. Ref. [106] considered the broader concept of fintech services but only assessed 14 articles. Conversely, this study examines 84 peer-reviewed articles on fintech payment apps, analyzing recent theories, constructs, and methodologies. While some previous research [107] explored fintech from a company perspective, this study focuses on the context of consumers, aiming to understand their perception and acceptance of fintech payment services. Additionally, a previous study [108] only identified 16 articles from a single database, whereas the present study reviewed 84 peer-reviewed articles from various databases (namely Scopus, ScienceDirect, Emerald, and Google Scholar). Furthermore, their methodology and framework were not clearly stated, whereas this study utilized the SPAR-4-SLR protocol and TCCM framework, which were explicitly explained in the present study. Overall, this study offers several key contributions for future researchers, which can be summarized in the following points:

- First, the present paper can be followed in the phase of collecting data from databases, i.e., the SPAR-4-SLR protocol [13]. This approach has not been followed in the literature review studies in the consumer adoption of fintech services. Applying this protocol can guide future researchers in conducting literature reviews.

- Second, the paper is distinctive as it followed the TCCM framework presented by [14] in the analysis and results, which has not been followed in the literature review studies in the consumer adoption of fintech services. This can also guide future researchers to follow a framework in conducting literature reviews.

- Third, the current study is unique as it synthesizes recent studies by covering the period from the beginning of the emergence of studies related to fintech payment services and consumer acceptance (2015) until April 2023. Future researchers who are interested in this subject can benefit from this literature, as it covers the studies from the beginning of the emergence of this context.

- Fourth is the inclusion of a newly established fintech payment service, i.e., BNPL, which has been one of the trending fintech solutions that have received recent attention in academic studies [15,16,17,18]. Due to its recent emergence, we found that there has been no systematic review, until now, that has covered this fintech payment service. The current study includes this new fintech service and its acceptance by consumers in its review to provide a better understanding for future researchers.

- Fifth, the study contributes conceptually by identifying and summarizing the theories and factors influencing the adoption and acceptance of fintech apps in payment services. As a result, future researchers can examine other theories and factors in different geographical contexts.

7. Conclusions

This paper has presented a literature review of articles focusing on the acceptance of fintech payment services. Eighty-four peer-reviewed articles were identified from 2015 to April 2023, and most were published in 2022. Twenty-four countries have been examined in the identified articles, mostly in Indonesia, Malaysia, and China. The identified articles mostly studied the fintech payment apps, the BNPL, mobile payment, fintech services, e-wallet, and the Islamic Fintech. The main theory used to understand the consumer acceptance of fintech payment services was the TAM. The four constructs that were tested and found to have a significant association with the acceptance behaviour were perceived usefulness, trust, perceived ease of use, and attitude. Research gaps and a future research agenda, and research academic contributions have also been presented. The paper provides valuable insights, such as the need to incorporate more recent theories, examine the challenges faced by older generations, target underrepresented countries, and differentiate acceptance by gender. The study further emphasizes the importance of investigating specific fintech payment services, like BNPL, and utilizing both secondary data and mixed methods in future research.

The current paper, like any other, has some limitations that suggest opportunities for further research in the future. First, it considered one aspect of the fintech payment services by focusing on Business to Consumer (B2C), but has not considered Business to Business (B2B) acceptance behaviour. Moreover, this paper focused particularly on fintech payment services, which is a single branch of the wider fintech services, such as insurance, crowdfunding, asset management, and many others [5]. Additionally, the SLR context does not concentrate on a particular demographic of mobile payment or fintech users, such as millennials or generation Z, who are often the prominent users of such technologies. Finally, the paper conducted a literature review with secondary data but did not collect primary data. These limitations can be valuable insights for future research. Despite its limitations, this study aims to evaluate the historical and predicted contributions of academia to consumer acceptance of fintech payment apps, and to propose a future research agenda.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.S.A. and R.S.A.; methodology, R.S.A.; software, S.S.A.; validation, R.S.A. and S.S.A.; formal analysis, R.S.A.; investigation, R.S.A.; resources, S.S.A.; data curation, S.S.A.; writing—original draft preparation, R.S.A.; writing—review and editing, S.S.A.; visualization, R.S.A. and S.S.A.; supervision, S.S.A.; project administration, R.S.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Ferraz, R.M.; da Veiga, C.P.; da Veiga, C.R.P.; Furquim, T.S.G.; da Silva, W.V. After-Sales Attributes in E-Commerce: A Systematic Literature Review and Future Research Agenda. J. Theor. Appl. Electron. Commer. Res. 2023, 18, 475–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bălan, C. Chatbots and Voice Assistants: Digital Transformers of the Company–Customer Interface—A Systematic Review of the Business Research Literature. J. Theor. Appl. Electron. Commer. Res. 2023, 18, 995–1019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Yang, J.; Hou, Y.; Li, S.; Sun, S. Gamification of mobile wallet as an unconventional innovation for promoting Fintech: An fsQCA approach. J. Bus. Res. 2023, 155, 113406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bommer, W.H.; Milevoj, E.; Rana, S. A meta-analytic examination of the antecedents explaining the intention to use fintech. Ind. Manag. Data Syst. 2023, 123, 886–909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, S.H.; Kim, D.J.; Hur, Y.; Park, K. An empirical study of the impacts of perceived security and knowledge on continuous intention to use mobile fintech payment services. Int. J. Hum. Comput. Interact. 2019, 35, 886–898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milian, E.Z.; Spinola, M.D.M.; de Carvalho, M.M. Fintechs: A literature review and research agenda. Electron. Commer. Res. Appl. 2019, 34, 100833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schueffel, P. Taming the beast: A scientific definition of fintech. J. Innov. Manag. 2016, 4, 32–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alwi, S. Fintech as financial inclusion: Factors affecting behavioral intention to accept mobile e-wallet during COVID-19 outbreak. Turk. J. Comput. Math. Educ. 2021, 12, 2130–2141. [Google Scholar]

- Ernst & Young Global Fintech Adoption Index 2019. 2019. Available online: https://www.ey.com/en_gl/ey-global-fintech-adoption-index (accessed on 11 February 2023).

- Daragmeh, A.; Lentner, C.; Sági, J. FinTech payments in the era of COVID-19: Factors influencing behavioral intentions of “Generation X” in Hungary to use mobile payment. J. Behav. Exp. Finance 2021, 32, 100574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kajol, K.; Singh, R.; Paul, J. Adoption of digital financial transactions: A review of literature and future research agenda. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2022, 184, 121991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furquim, T.S.G.; da Veiga, C.P.; Veiga, C.R.P.D.; Silva, W.V.D. The Different Phases of the Omnichannel Consumer Buying Journey: A Systematic Literature Review and Future Research Directions. J. Theor. Appl. Electron. Commer. Res. 2022, 18, 79–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, J.; Lim, W.M.; O’Cass, A.; Hao, A.W.; Bresciani, S. Scientific procedures and rationales for systematic literature reviews (SPAR-4-SLR). Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2021, 45, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, J.; Rosado-Serrano, A. Gradual internationalization vs born-global/international new venture models: A review and research agenda. Int. Mark. Rev. 2019, 36, 830–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aalders, R. Buy now, pay later: Redefining indebted users as responsible consumers. Inf. Commun. Soc. 2023, 26, 941–956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guttman-Kenney, B.; Firth, C.; Gathergood, J. Buy now, pay later (BNPL)… on your credit card. J. Behav. Exp. Finance 2023, 37, 100788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.; Haque, S. Impact of Buy Now-Pay Later Mechanism through Installment Payment Facility and Credit Card Usage on the Impulsive Purchase Decision of Consumers: Evidence from Dhaka City. Southeast Univ. J. Arts Soc. Sci. 2021, 3, 40–59. [Google Scholar]

- Tan, G.K.S. Buy what you want, today! Platform ecologies of ‘buy now, pay later’services in Singapore. Trans. Inst. Br. Geogr. 2022, 47, 912–926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Păuceanu, A.M.; Văduva, S.; Nedelcuț, A.C. Social Commerce in Europe: A Literature Review and Implications for Researchers, Practitioners, and Policymakers. J. Theor. Appl. Electron. Commer. Res. 2023, 18, 1283–1300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korte, A.; Tiberius, V.; Brem, A. Internet of Things (IoT) technology research in business and management literature: Results from a co-citation analysis. J. Theor. Appl. Electron. Commer. Res. 2021, 16, 2073–2090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prados-Castillo, J.F.; Guaita Martínez, J.M.; Zielińska, A.; Gorgues Comas, D. A Review of Blockchain Technology Adoption in the Tourism Industry from a Sustainability Perspective. J. Theor. Appl. Electron. Commer. Res. 2023, 18, 814–830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, R.; Singh, R.K.; Koles, B. Consumer decision-making in Omnichannel retailing: Literature review and future research agenda. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2021, 45, 147–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomber, P.; Kauffman, R.J.; Parker, C.; Weber, B.W. On the fintech revolution: Interpreting the forces of innovation, disruption, and transformation in financial services. J. Manag. Inf. Syst. 2018, 35, 220–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Z.; Ding, S.; Li, S.; Chen, L.; Yang, S. Adoption intention of fintech services for bank users: An empirical examination with an extended technology acceptance model. Symmetry 2019, 11, 340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belanche, D.; Casaló, L.V.; Flavián, C. Artificial Intelligence in FinTech: Understanding robo-advisors adoption among customers. Ind. Manag. Data Syst. 2019, 119, 1411–1430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chuang, L.M.; Liu, C.C.; Kao, H.K. The adoption of fintech service: TAM perspective. Int. J. Manag. Adm. Sci. 2016, 3, 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Stewart, H.; Jürjens, J. Data security and consumer trust in FinTech innovation in Germany. Inf. Comput. Secur. 2018, 26, 109–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shiau, W.L.; Yuan, Y.; Pu, X.; Ray, S.; Chen, C.C. Understanding fintech continuance: Perspectives from self-efficacy and ECT-IS theories. Ind. Manag. Data Syst. 2020, 120, 1659–1689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbu, C.M.; Florea, D.L.; Dabija, D.C.; Barbu, M.C.R. Customer experience in fintech. J. Theor. Appl. Electron. Commer. Res. 2021, 16, 1415–1433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.; Park, Y.J.; Choi, J.; Yeon, J. An empirical study on the adoption of “Fintech” service: Focused on mobile payment services. Adv. Sci. Technol. Lett. 2015, 114, 136–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.; Sahni, M.M.; Kovid, R.K. What drives FinTech adoption? A multi-method evaluation using an adapted technology acceptance model. Manag. Decis. 2020, 58, 1675–1697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nathan, R.J.; Setiawan, B.; Quynh, M.N. Fintech and financial health in Vietnam during the COVID-19 pandemic: In-depth descriptive analysis. J. Risk Financ. Manag. 2022, 15, 125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alshari, H.A.; Lokhande, M.A. The impact of demographic factors of clients’ attitudes and their intentions to use FinTech services on the banking sector in the least developed countries. Cogent Bus. Manag. 2022, 9, 2114305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aseng, A.C. Factors Influencing Generation Z Intention in Using FinTech Digital Payment Services. CogITo Smart J. 2020, 6, 155–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karim, R.A.; Sobhani, F.A.; Rabiul, M.K.; Lepee, N.J.; Kabir, M.R.; Chowdhury, M.A.M. Linking Fintech Payment Services and Customer Loyalty Intention in the Hospitality Industry: The Mediating Role of Customer Experience and Attitude. Sustainability 2022, 14, 16481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koroleva, E. Attitude Towards Using Fintech Services: Digital Immigrants Versus Digital Natives. Int. J. Innov. Technol. Manag. 2022, 19, 2250029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.T.; Pan, L.Y. Smile to pay: Predicting continuous usage intention toward contactless payment services in the post-COVID-19 era. Int. J. Bank Mark. 2023, 41, 312–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mainardes, E.W.; Costa, P.M.F.; Nossa, S.N. Customers’ satisfaction with fintech services: Evidence from Brazil. J. Financ. Serv. Mark. 2023, 28, 378–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngo, H.T.; Nguyen, L.T.H. Consumer adoption intention toward FinTech services in a bank-based financial system in Vietnam. J. Financ. Regul. Compliance 2022. ahead-of-print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roh, T.; Yang, Y.S.; Xiao, S.; Park, B.I. What makes consumers trust and adopt fintech? An empirical investigation in China. Electron. Commer. Res. 2022, 1–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souza, M.V.D.; Spers, E.E. Proposal of the FinTech’s Services Adoption Measurement Model. Rev. Adm. Dialogo 2021, 30, 96–114. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Z.; Guan, Z.; Hou, F.; Li, B.; Zhou, W. What determines customers’ continuance intention of FinTech? Evidence from YuEbao. Ind. Manag. Data Syst. 2019, 119, 1625–1637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, C.; Siddik, A.B.; Akter, N.; Dong, Q. Factors influencing the adoption intention of using mobile financial service during the COVID-19 pandemic: The role of FinTech. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2021, 30, 61271–61289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ah Fook, L.; McNeill, L. Click to buy: The impact of retail credit on over-consumption in the online environment. Sustainability 2020, 12, 7322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burton, D. Digital debt collection and ecologies of consumer overindebtedness. Econ. Geogr. 2020, 96, 244–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, L.; Teng, J.T.; Zhou, F. Pricing and lot-sizing decisions on buy-now-and-pay-later installments through a product life cycle. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2023, 306, 754–763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerrans, P.; Baur, D.G.; Lavagna-Slater, S. Fintech and responsibility: Buy-now-pay-later arrangements. Aust. J. Manag. 2022, 47, 474–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, D.; Rodwell, J.; Hendry, T. Analyzing the impacts of financial services regulation to make the case that buy-now-pay-later regulation is failing. Sustainability 2021, 13, 1992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pattamatta, P.; Dabadghao, S.S. Models for Point-of-Sale (POS) Market Entry. FinTech 2022, 1, 318–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schomburgk, L.; Hoffmann, A. How mindfulness reduces BNPL usage and how that relates to overall well-being. Eur. J. Mark. 2023, 57, 325–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdillah, L.A. FinTech E-commerce payment application user experience analysis during COVID-19 pandemic. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2012.07750. [Google Scholar]

- Johan, S. Users’ acceptance of financial technology in an emerging market (An empirical study in Indonesia). J. Ekon. Dan Bisnis 2020, 23, 173–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alwi, S.; Salleh, M.N.M.; Kamaruddin, H.; Alpandi, R.M.; Razak, S.E.A. The e-wallet usage as an acceptance indicator on Financial Technology in Malaysia. Relig. Rev. Cienc. Soc. Humanid. 2019, 4, 45–52. [Google Scholar]

- Karim, M.W.; Chowdhury, M.A.M.; Haque, A.A. A Study of Customer Satisfaction Towards E-Wallet Payment System in Bangladesh. Am. J. Econ. Bus. Innov. 2022, 1, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeh, H. Factors in the ecosystem of mobile payment affecting its use: From the customers’ perspective in Taiwan. J. Theor. Appl. Electron. Commer. Res. 2020, 15, 13–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdul-Rahim, R.; Bohari, S.A.; Aman, A.; Awang, Z. Benefit–Risk Perceptions of FinTech Adoption for Sustainability from Bank Consumers’ Perspective: The Moderating Role of Fear of COVID-19. Sustainability 2022, 14, 8357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agustiningsih, M.D.; Savitrah, R.M.; Lestari, P.C.A. Indonesian young consumers’ intention to donate using sharia fintech. Asian J. Islam. Manag. AJIM 2021, 3, 34–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Nawayseh, M.K. Fintech in COVID-19 and beyond: What factors are affecting customers’ choice of fintech applications? J. Open Innov. Technol. Mark. Complex. 2020, 6, 153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darmansyah, D.; Fianto, B.A.; Hendratmi, A.; Aziz, P.F. Factors determining behavioral intentions to use Islamic financial technology: Three competing models. J. Islam. Mark. 2020, 12, 794–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Datta, D. The Future of Financial Inclusion Through Fintech: A Conceptual Study in Post Pandemic India. Sachetas 2023, 2, 11–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Handarkho, Y.D.; Harjoseputro, Y.; Samodra, J.E.; Irianto, A.B.P. Understanding proximity mobile payment continuance usage in Indonesia from a habit perspective. J. Asia Bus. Stud. 2021, 15, 420–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lantang, A.P.; Pangemanan, S.S.; Tielung, M.V. The Influence of Ease of Use and Facility Towards Customer Satisfaction on Fintech Digital Payment. J. Ris. Ekon. Manaj. Bisnis Dan Akunt. 2021, 9, 406–414. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, Y.K. Higher innovativeness, lower technostress?: Comparative study of determinants on FinTech usage behavior between Korean and Chinese Gen Z consumers. Asia Pac. J. Mark. Logist. 2022. ahead-of-print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mascarenhas, A.B.; Perpétuo, C.K.; Barrote, E.B.; Perides, M.P. The influence of perceptions of risks and benefits on the continuity of use of fintech services. Braz. Bus. Rev. 2021, 18, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ming, K.L.Y.; Jais, M. Factors affecting the intention to use e-wallets during the COVID-19 pandemic. Gadjah Mada Int. J. Bus. 2022, 24, 82–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nan, D.; Kim, Y.; Huang, J.; Jung, H.S.; Kim, J.H. Factors affecting intention of consumers in using face recognition payment in offline markets: An acceptance model for future payment service. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 830152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nurfadilah, D.; Samidi, S. How The COVID-19 Crisis is Affecting Customers’ Intentions to Use Islamic Fintech Services: Evidence from Indonesia. J. Islam. Monet. Econ. Finance 2021, 7, 83–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oladapo, I.A.; Hamoudah, M.M.; Alam, M.M.; Olaopa, O.R.; Muda, R. Customers’ perceptions of FinTech adaptability in the Islamic banking sector: Comparative study on Malaysia and Saudi Arabia. J. Model. Manag. 2022, 17, 1241–1261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purba, J.; Samuel, S.; Budiono, S. Collaboration of digital payment usage decision in COVID-19 pandemic situation: Evidence from Indonesia. Int. J. Data Netw. Sci. 2021, 5, 557–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahzad, A.; Zahrullail, N.; Akbar, A.; Mohelska, H.; Hussain, A. COVID-19’s Impact on Fintech Adoption: Behavioral Intention to Use the Financial Portal. J. Risk Financ. Manag. 2022, 15, 428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spulbar, C.; Birau, R.; Calugaru, T.; Mehdiabadi, A. Considerations regarding FinTech and its multidimensional implications on financial systems. Rev. Stiinte Politice 2020, 68, 77–86. [Google Scholar]

- Susilo, A.Z.; Prabowo, M.I.; Taman, A.; Pustikaningsih, A.; Samlawi, A. A comparative study of factors affecting user acceptance of go-pay and OVO as a feature of Fintech application. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2019, 161, 876–884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, K.L.; Ooi, C.K.; Chong, J.B. Perceived risk factors affect intention to use FinTech. J. Account. Finance Emerg. Econ. 2020, 6, 453–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tun-Pin, C.; Keng-Soon, W.C.; Yen-San, Y.; Pui-Yee, C.; Hong-Leong, J.T.; Shwu-Shing, N. An adoption of fintech service in Malaysia. South East Asia J. Contemp. Bus. 2019, 18, 134–147. [Google Scholar]

- Vaicondam, Y.; Jayabalan, N.; Tong, C.X.; Qureshi, M.I.; Khan, N. Fintech Adoption Among Millennials in Selangor. Acad. Entrep. J. 2021, 27, 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J.S. Exploring biometric identification in FinTech applications based on the modified TAM. Financ. Innov. 2021, 7, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wardani, D.; Wulandari, N.; Baskara, C.A. Understanding Customer Acceptance To Financial Technology; Study In Indonesia. Int. J. Innov. Technol. Econ. 2021, 2, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weichert, M. The future of payments: How FinTech players are accelerating customer-driven innovation in financial services. J. Paym. Strategy Syst. 2017, 11, 23–33. [Google Scholar]

- Won-jun, L. Understanding consumer acceptance of Fintech Service: An extension of the TAM Model to understand Bitcoin. IOSR J. Bus. Manag. 2018, 20, 34–37. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, L.L.; Kim, H. The influence of financial service characteristics on use intention through customer satisfaction with mobile fintech. J. Syst. Manag. Sci. 2020, 10, 82–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, M.; Raza, S.A.; Khamis, B.; Puah, C.H.; Amin, H. How perceived risk, benefit and trust determine user Fintech adoption: A new dimension for Islamic finance. Foresight 2021, 23, 403–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakri, M.H.; Yahaya, S.N. Conceptualization of Spiritual intelligence quotient (SQ) in the Islamic Fintech adoption. Islamiyyat 2020, 42, 113–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maryam, S.Z.; Ahmed, A.; Haider, S.W.; Akhter, T. Explicating the adoption of an innovation Fintech Value Chain Financing from Aarti (Middlemen) perspective in Pakistan. Afr. J. Sci. Technol. Innov. Dev. 2023, 15, 429–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahim, N.F.; Bakri, M.H.; Fianto, B.A.; Zainal, N.; Hussein Al Shami, S.A. Measurement and structural modelling on factors of Islamic Fintech adoption among millennials in Malaysia. J. Islam. Mark. 2022, 14, 1463–1487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaikh, I.M.; Qureshi, M.A.; Noordin, K.; Shaikh, J.M.; Khan, A.; Shahbaz, M.S. Acceptance of Islamic financial technology (FinTech) banking services by Malaysian users: An extension of technology acceptance model. Foresight 2020, 22, 367–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belanche, D.; Guinalíu, M.; Albás, P. Customer adoption of p2p mobile payment systems: The role of perceived risk. Telemat. Inform. 2022, 72, 101851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, H.; Park, J.; Kim, J.; Jung, Y. Consumer preferences of attributes of mobile payment services in South Korea. Telemat. Inform. 2020, 51, 101397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diana, N.; Leon, F.M. Factors affecting continuance intention of FinTech payment among Millennials in Jakarta. Eur. J. Bus. Manag. Res. 2020, 5, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haritha, P.H. Mobile payment service adoption: Understanding customers for an application of emerging financial technology. Inf. Comput. Secur. 2023, 31, 145–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, M.S.; Islam, M.A.; Sobhani, F.A.; Nasir, H.; Mahmud, I.; Zahra, F.T. Drivers influencing the adoption intention towards mobile fintech services: A study on the emerging Bangladesh market. Information 2022, 13, 349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, Y.; Park, S.; Shin, N. Sustainable development of a mobile payment security environment using fintech solutions. Sustainability 2021, 13, 8375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khuong, N.V.; Phuong, N.T.T.; Liem, N.T.; Thuy, C.T.M.; Son, T.H. Factors Affecting the Intention to Use Financial Technology among Vietnamese Youth: Research in the Time of COVID-19 and Beyond. Economies 2022, 10, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laksamana, P.; Suharyanto, S.; Cahaya, Y.F. Determining factors of continuance intention in mobile payment: Fintech industry perspective. Asia Pac. J. Mark. Logist. 2023, 35, 1699–1718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, J.; Ye, L.; Huang, W.; Ye, M. Understanding FinTech platform adoption: Impacts of perceived value and perceived risk. J. Theor. Appl. Electron. Commer. Res. 2021, 16, 1893–1911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yahaya, M.H.; Ahmad, K. Factors affecting the acceptance of financial technology among asnaf for the distribution of zakat in Selangor-A Study Using UTAUT. J. Islam. Finance 2019, 8, 35–46. [Google Scholar]

- Chan, R.; Troshani, I.; Rao Hill, S.; Hoffmann, A. Towards an understanding of consumers’ FinTech adoption: The case of Open Banking. Int. J. Bank Mark. 2022, 40, 886–917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.K.; Sharma, P. A study of Indian Gen X and Millennials consumers’ intention to use FinTech payment services during COVID-19 pandemic. J. Model. Manag. 2022, 18, 1177–1203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jebarajakirthy, C.; Maseeh, H.I.; Morshed, Z.; Shankar, A.; Arli, D.; Pentecost, R. Mobile advertising: A systematic literature review and future research agenda. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2021, 45, 1258–1291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soriano, M.; Ziegler, T.; Umer, Z.; Chen, H.; Jenweeranon, P.; Zhang, B.Z.; Donald, D.C.; Lin, L.; Alam, N.; Luo, C.S.; et al. The ASEAN Fintech Ecosystem Benchmarking Study. 2019. Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3772254 (accessed on 28 January 2023).

- Dwivedi, Y.K.; Rana, N.P.; Jeyaraj, A.; Clement, M.; Williams, M.D. Re-examining the unified theory of acceptance and use of technology (UTAUT): Towards a revised theoretical model. Inf. Syst. Front. 2019, 21, 719–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lashitew, A.A.; van Tulder, R.; Liasse, Y. Mobile phones for financial inclusion: What explains the diffusion of mobile money innovations? Res. Policy 2019, 48, 1201–1215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeLone, W.H.; McLean, E.R. The DeLone and McLean model of information systems success: A ten-year update. J. Manag. Inf. Syst. 2003, 19, 9–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Odilia, G.; Sulistiobudi, R.A.; Fitriana, E. Factors Contributing to Online Shopping Behavior During COVID-19 Pandemic: The Power of Electronic Word of Mouth in Digital Generation. Acad. Entrep. J. 2022, 28, 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Alam, M.M.; Awawdeh, A.E.; Muhamad, A.I.B. Using e-wallet for business process development: Challenges and prospects in Malaysia. Bus. Process Manag. J. 2021, 27, 1142–1162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suryono, R.R.; Budi, I.; Purwandari, B. Challenges and trends of financial technology (Fintech): A systematic literature review. Information 2020, 11, 590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giglio, F. Fintech: A literature review. Eur. Res. Stud. J. 2021, 24, 600–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takeda, A.; Ito, Y. A review of FinTech research. Int. J. Technol. Manag. 2021, 86, 67–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Firmansyah, E.A.; Masri, M.; Anshari, M.; Besar, M.H.A. Factors affecting fintech adoption: A systematic literature review. FinTech 2022, 2, 21–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).