Abstract

Studies on the Chinese government’s online response present diverse voices and perspectives, but consensus cannot be reached. The literature has constantly ignored the construction of an online media mechanism, which includes professional positions and standardized procedures that were designed inside the online media to process information and facilitate an effective government response. Does the reconstruction of an online media mechanism benefit the effectiveness of government response? If so, how? From the perspective of the media mechanism, what are the influential factors for the effectiveness of government response and how do they work to exert this impact? Engaging with the media system dependence theory, I conducted semi-structured, in-depth interviews with the editor at the Beijing Municipal Government Website and official document drafters at prestigious research institutions. In conversation with the political system theory, multinomial logistic regression was used to analyze the daily government response data covering the period from 2019 to 2020. This article argues that the innovations in the mechanism inside the online media system can outsource some information management functions from the political system to the online media system. These innovations also assist in partial power transfer from the political system to the media system to achieve an effective government response. The political system faces dual pressure, including content pressure and time pressure, regarding its online response.

1. Introduction

The development of the internet triggers expectations regarding its political impact, as it contains essential values of democracy, freedom and equality [1]. However, scholars cannot reach consensus over the political impact of the internet in China, which can be separated into two camps: power reinforcement and power redistribution. The political theory behind reinforcement asserts that the implementation of an e-government strengthens the power of political leaders and the internet intensifies authoritarian rule without leading to reformation or transformation of the government [2,3,4]. On the contrary, the power redistribution theory argues that digital technology empowers the public to challenge authoritarian rule, with participation in public policy expanding from the center to the peripheral due to the trend of decentralization brought about by the internet [5,6,7]. As both camps are supported by evidence, consensus cannot easily be reached.

Among the diverse impacts that the internet has on the Chinese government, responsiveness is a significant aspect, as it is closely connected to the third stage of the development of Chinese digital governance: the relationship between state and society [7]. Developed in Western countries during the government legitimacy crisis in the period from the 1960s to 1970s [8], “government responsiveness” is defined as the government’s adoption of public policies that are the expressed preferences of citizens [9] or the government showing a timely reaction to public requests for policy changes [10]. In the Chinese context, government responsiveness is regarded as the interactions between the government and the public [8]. It is necessary for the Chinese government to respond to public demands to maintain legitimacy and establish a positive image. Responsiveness is regarded as fundamental political legitimacy in modern China, where politics and administration are merged [11,12]. Through responding to public demands, the regime can both consolidate legitimacy and collect information from the public [13]. Moreover, it is also conducive to establishing a positive image of the government, as the Chinese government is perceived as being fearful of the public’s reaction to the inaction of officials [14], especially potential public protest [15].

There are discrepancies in the understanding of government responsiveness in China when comparing the academic literature and official documents. The Chinese government’s responsiveness is perceived as declining longitudinally with the concentration of political power under Xi Jinping’s administration compared with the period of Hu Jintao [16]. However, government official documents tell a different story. At the central government level, problems of responsiveness have been identified and assessment indicators have been adjusted accordingly. “Poor interaction response” is incorporated as one of the “individual rejection indicators”, with any of these directly causing the official website to be unqualified for being assessed as excellent [17]. From the local perspective, the Beijing Municipal Government issued a local official document to stress the mechanism of the construction of public advice processes and set time constraints for the government’s response [18]. Both of these central- and local-level official documents demonstrate the authorities’ emphasis on government responsiveness, which contradicts the claims of its decline in the academic literature.

Research on Chinese government responsiveness commonly focuses on the influence of socio-economic factors regarding whether the government responds and the policy impact generated by online expressions. Based on the data on online public opinion from the Message Board for Leaders of the Renmin Net, it is argued that whether the Chinese government responds or not depends on the social identities of the netizens and the policy categories of posts [19]. The result of an online field experiment shows that claims to be organizing collective action and references to upper levels of government are more effective in triggering county-level governments responsiveness compared with indicating loyalty to the Chinese Communist Party [20]. Regarding the policy impact of online public opinion, scholars argue that the stronger official stress on policies of social welfare was triggered by online expressions through the content comparison between public expressions on the Message Board for Leaders and Government Work Reports [21]. However, the literature has rarely investigated the construction of an operation mechanism inside the online media system to facilitate effective government response. The power reallocation and transfer in the connection between state and society through the online response process have been consistently ignored by scholars.

This article focuses on the local government’s response through the official website of Beijing Municipal Government, which is called “the Window of the Capital”. The reason for choosing this case is its outstanding performance among government websites, especially its indicated public–government interaction. This website was ranked the highest among local government websites in 2020 [22]. It ranked first at the provincial level for public–government interactions in the past 12 consecutive years. An analysis of this case is conducive to understanding how to achieve effective government response through the design of an online media operation mechanism and adjustment of influential factors to structure information. “Online government response”, in this article, is defined as the government’s replies to citizens’ consultations, advice, complaints and reports, with the aim of solving public inquiries through official websites.

In the following sections, I will first introduce the media dependence theory and the political system theory, and justify why these two theories are suitable for answering the research questions. After that, I will explain the research methods that were chosen and how to use them to address relevant questions. In the Discussion section, I will analyze the power transfer from the political system to the media system to process information from the perspectives of the creation of professional positions, the application of the knowledge base, the arbitration of jurisdiction disputes, and the implementation of response supervisions (duban). Following that, an analysis of how the online media system structures information will be conducted, focusing on the influential factors of the online mechanism regarding how to achieve public satisfaction from perspectives of both content pressure and time pressure. Finally, I will finish with concluding remarks, containing theoretical contributions and real-world implications.

2. Theories and Research Questions

According to the media dependence theory, both the political system and the individuals rely on the “dependency-engendering” resources controlled by the media to collect, process and disseminate information to achieve their goals [23]. In the government response process, individuals aim to state their concerns to the government. A specific mechanism is designed inside the media system to process the collected information and disseminate it to the corresponding sections in the political system. The political system responds through the media system to maintain the regime’s legitimacy and defend the official positive image. The two-sided dependence on the media system highlights the importance of the online media system for facilitating an effective government response. In addition to the dependence on the media system, there are also reverse dependencies: the media system depends on the political system and individuals [23]. Facilitating government response is one of the major functions of the Beijing Municipal Government Website. Individuals post their messages on this media system with the expectation of receiving a responsible and effective official response. Without the information resources provided by the public, the media system would lack a source of information to process, and could not deliver this information to the political system to trigger an official response. From the perspective of the political system, the government response information should first be consolidated to the online media system and pass the gatekeeping process before reaching the public. Without this connection with the political system, the online media system would lack the expertise to generate a response. Therefore, this mutual dependence makes the government response feasible.

In the online media context, research on the media system dependency theory is continuing to develop. The research has explored the influence of online resources on the perception of the potential of online democracy from the perspective of the media system dependency theory. It found that the intensity of Internet dependency is determined by the perceived comprehensiveness of online news, not its credibility [24]. Furthermore, the media system dependency theory can even explain some of the phenomenon of digital media usage in specific contexts. In special contexts such as the pandemic crisis, analyses using media system dependency theory reveal that the choice of media channel influences the effect of knowledge gains based on the evidence from a four-wave repeated cross-sectional survey [25]. The media system dependency theory has value even in the special context of social media use in the Chinese diaspora’s socialization process. It is argued that this theory contributes to explaining the success of cross-national propaganda conducted by the Chinese government [26]. Although the media system dependency theory can be applied to different digital contexts, very few studies have attempted to test the suitability of this theory to explain the construction of an online media mechanism, which includes the professional positions and standardized procedure designed using online media to process information and facilitate a government response.

From the perspective of politics, the modern political system requires the government to generate a continuous response to public opinions, which is regarded as one of its basic characteristics [27]. The political system theory is well-suited to explaining the process of online government response, as this process contains both a typical “input” and “output”, which are key factors of this theory. It regards politics as a system within the environment, which exerts influence on the “input”, containing requirements of, and support for, the political system. After processing the input, this system generates output to the environment, allowing for feedback to be returned to this [28]. In the context of government response, the public message that is posted online is a typical form of “input”, containing an expression of interest going into the political system, while the government response constitutes a specific form of “output” from this system. As an important function of the political system, the expression of interest determines the characteristics of the boundary and the model of boundary maintenance [29]. In the traditional context of an expression of interest from an interest group, the boundary between the political system and the social system is maintained by the activities of the interest group. The incorporation of the digital media system into the response process, such as through an official website, empowers the media system with the new role of boundary maintenance between the social system and the political system. From the perspective of output, the effectiveness of this output can potentially be influenced by both the content pressure and time pressure. The content pressure means that the substance of the input can have a negative stress on the political system to generate proper output [28]. Certain public messages may cause extra stress on the political system, generating a response. Time pressure is generated by the “lag” in the political system, which refers to the time this system takes to react to information [30]. The longer the lag procedure, the smaller the possibility of achieving the goal [31].

These two theories provide two explanations that can be used to answer the central research question: does the reconstruction of an online media mechanism, which includes professional positions and a standardized procedure designed inside the online media to process information, increase the effectiveness of the government response? If so, how? If not, why? Specific questions are answered using these two theories. From the perspective of the media dependence theory, this research asks: how does the online media system reconstruct the mechanism of the information process to ensure the effectiveness of the government response? In conversation with the political system theory, the study asks: what are the influential factors pertaining to the online media mechanism to ensure the effectiveness of government response? How do they exert their specific impacts?

3. Research Methods

This research uses mixed methods, including a semi-structured in-depth interview and multinomial logistic regression. Researchers have discussed the benefit of using interviews to uncover in-depth information, as they are regarded as “the favored digging tool” for social researchers [32,33]. By conducting interviews, researchers can investigate the reality of the world by asking questions and providing answers through verbal communication [34]. The nature of the research question determines whether an in-depth interview should be chosen [35]. As this paper is interested in understanding the internet mechanism constructed to process information and improve the effectiveness of the government response, it is necessary to use this method with people who are involved in the responsive operation of the official website.

I conducted semi-structured, in-depth interviews lasting around six hours with Mr. Q, the senior manager of the Department of the Interaction between the Public and Politics at the Window of the Capital. Each interview lasted around four hours; interviews were with the Deputy Director Mr. Z and the major project researcher Mr. W at the E-Government Laboratory at our university. Due to his direct responsibility, Mr. Q is very familiar with the information mechanism constructed at the Beijing Municipal Government Website for processing public messages and government response. Mr. Z and Mr. W worked together to draft the <Notice of the General Office of the State Council on Issuing the Guidelines for the Development of Government Websites> in 2017 and <The Notice on the Issuance of Assessment Indicators and Inspection Indicators for Government Websites and Government New Media> in 2019, which are both influential official documents issued by the central government regarding the construction of government websites for the response function.

In addition to the interviews, I also used multinomial logistic regression to analyze the data of online messages and government responses for the influential factors regarding the effectiveness of government response. This method can test the significance of the correlation between numerical independent variables and binary dependent variables. This effectiveness can be represented by the level of satisfaction using the attribute “the category of feedback” (At the Window of the Capital, there are four categories of public feedbacks: satisfied (manyi), general (yiban), not satisfied (bu manyi), no feedback (wu pingjia)).

As mentioned briefly in the political system theory, certain pressures contained in this input can negatively influence the function of the political system to ensure the quality of its output. One of these pressures is called “content pressure”, which refers to the stress caused by the substance of the input and the pressure faced by the political system [36] (Easton, 1965). A potential perspective to reflect the content pressure of input is the category of online public messages, which are classified as consultation, suggestion, complaint and report in this case. As different categories are consolidations of information with similar content, this represents how the online mechanism structures information based on content. Once the structure of information becomes steady, the potential content pressure from this structure could be consistently triggered. This leads to the hypothesis (H1a) that the way the internet structures information has a significant correlation with the effectiveness of the official response. More specifically, the way the internet structures information refers to how the online public messages are categorized. The effectiveness of official response is represented by the public satisfactory level (At the Window of the Capital, there are four categories of public feedback: satisfied (manyi), general (yiban), not satisfied (bu manyi), no feedback (wu pingjia).) In addition to the category of message, the online mechanism also structures information across different government departments. There are 83 government departments and institutions, connected by the Beijing Municipal Government Website. As each of them has its own specialization regarding public affairs, different government departments and institutions may face different levels of content pressure and different difficulties in generating an effective response. Thus, the study raises the hypothesis (H1b) that the way the internet structures information, which refers to the government departments and institutions generating the responses, is significantly correlated with the effect of the response. This is represented by the public’s level of satisfaction with the responses.

The political system theory is further developed from the perspective of government communication. Karl Deutsch emphasizes the significance of information communication in governance and describes it with the metaphor “the nerve of government” [31]. Informed by the communication flows, the government conducts “steering” instead of controlling [31], which can be understood as an ongoing movement, continual adjustment of strategy and sensitivity to the environment [37]. Two concepts, including “lag” and “gain”, are introduced to further interpret the government “steering” process. “Lag” means that the political system takes time to generate a reaction to information. “Gain” means the extent of this reaction; different reactions have differing abilities to resolve public requests [30]. The greater the lag, the lower the possibility of the political system being able to reach the goal [31]. In other words, the longer the political system takes to react, the less effective this reaction is in fulfilling public requests. From this interpretation, the research raises the hypothesis (H2a) that the longer the government process time, the lower the possibility of achieving public satisfaction. As the lag in the online response procedure also includes the process time of the official website, another hypothesis (H2b) is raised: the longer the government website process time, the less likely the public is to be satisfied by the response.

To explore the influence of processing factors in the response procedure on public satisfaction, I created the binary dependent variable of “satisfied or not” through coding the category of “satisfied” feedback as “1” and other categories, including “not satisfied” and “general”, as “0”. The response dataset, which was collected from the Department of Technology at the Window of the Capital, contains 272,707 observations covering everyday public messages and government replies from 2019 to 2020 (Each observation regarding the dataset represents a message that was posted online and its variables. The initial 10 variables include “category of message”, “title of message”, “content of message”, “time the message was posted online”, “time of government receiving message”, “reply department”, “time of reply”, “content of reply”, “category of feedback” and “reason for feedback”). I set the attribute “length of reply” as the control variable, which may influence public satisfaction but is not directly related to the influential factors in which I am interested. To test the first series of hypotheses (H1a and H1b), I added the category of online public message and government departments as the independent variables. In order to test the second series of hypotheses (H2a and H2b), I added the government process time and the government website process time as the independent variables.

4. Discussions

4.1. Media Mechanism

The Window of the Capital, on the one hand, has the unique functions of media to collect, process and disseminate information. On the other hand, it is a public institution (shiye danwei), which is greatly affected by administrative instructions and policy updates. The intensification (jiyue hua) of government websites encouraged by the central government creates a positive environment for the construction of a new mechanism inside the online media system to systematically process information. In 2018, the General Office of the State Council issued <The Government Website Intensification Pilot Work Plan> to suggest “building intensive platforms for government websites based on unified information resource base” and chose Beijing as one of the ten pilot areas [38]. Since 2019, the government websites of different departments in Beijing were gradually integrated into one platform, following the official guidance [39]. Before that, different government departments and institutions individually constructed their own websites, with public funding being allocated separately. This caused the problem that public messages to different government departments could only be posted on their individual corresponding websites, and were processed separately, which increased the administration cost and complexity of the work and decreased the efficiency of the response. The launch of the integrated online governance platform on 1 January, 2020, was conducive to the construction of a new comprehensive mechanism inside the website to systematically process government response, as this platform serves as the only online portal to navigate public messages, which largely reduces the complexity of the public matching their inquiries with the corresponding departments.

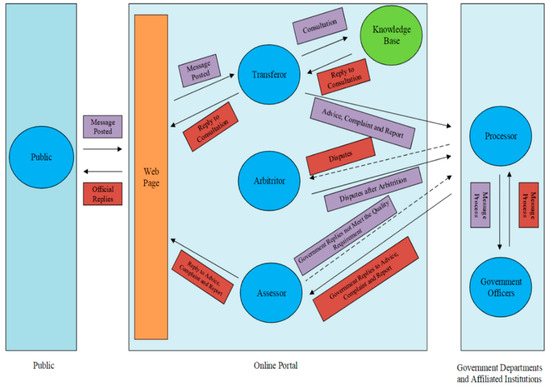

The political system outsourced some information management functions to the online media systems in the case of Beijing. To be more specific, this outsourcing was achieved by setting up professional positions and constructing a standardized procedure for information processing within the online media system. Information processing is regarded as one of the “dependency-engendering” information resources of the media system [23]. The specific professionalization initiatives are to set up specialized positions, including a transferer (zhuanban ren), arbitrator (zhongcai ren) and an assessor (chuli ren), with clear and separated responsibilities at different stages of information processing (Figure 1). Benefitting from the information technology, the online media system constructs a new mechanism for information processing between the government and the public. As argued by Jane Fountain, one of the main effects of information technology on political institutions is its ability to create the capacity for information processing and information flow [40]. The information related to government response is processed in a professional way in the online media system, and flows according to specific rules. The transferer (zhuanban ren), as the first position that accesses the public messages posted online, works as a pivot to accurately deliver public messages to the corresponding government departments. Their responsibilities also include categorizing and shunting public concerns. If the public messages can be classified as consultation, they will be delivered to the knowledge base (zhishi ku) for an automatic response. If the transferer categorizes the public concerns as suggestion, complaint or report, they will be sent to the corresponding government departments for response.

Figure 1.

The Message process procedure at the Window of the Capital. Notes: The figure was created based on the semi-structured interviews conducted at the Window of the Capital.

The individuals form a special type of dependence on the online media system during the whole process of government response. To satisfy the individuals’ demands, the online media system establishes an organic structure to process information. As the audience, the individuals have certain demands, including receiving government responses that address their inquiries. Satisfying “individual needs” is one of the ways to increase peoples’ dependencies on media information [23]. Individuals’ dependence on the online media system leads to demands to simplify the procedure regarding public inquiries. The innovations of the online media mechanism, which include the creation of professional positions and a standardized procedure inside online media to process information, seem to realize the expectation of Owen Hughes regarding the development of an e-government: through technological changes, government customers do not need to know the clear boundaries between institutional work, especially regarding service provision [41]. Assisted by the online media system, the public only needs to refer to a single official website to leave a message, no matter which government department is responsible for the inquiry. Inside the online media system, professional positions are connected with each other inside the online media system to form “organic structures”, which means that the connections and behaviors of these parts can be explained from the perspective of this relationship [23]. Specialized positions are connected through the information flow within the online mechanism. After being categorized and shunted by the transferer at an early position of the information flow, information containing suggestions, complaints and reports is delivered into the political system. Once controversies regarding the different government departments’ jurisdiction arise, information is sent back to the arbitrator in the media system. Being positioned at the last stage of gatekeeping, information containing a response must pass the assessor’s evaluation before reaching the public. All these positions are organically connected by information flow, which engenders the individuals’ special dependence on the media system to satisfy their need for an effective official response.

The semi-automation of the information process represents the typical dependence of both the political system and the individual system on the media system. The semi-automation refers to the function of “the knowledge base (zhishi ku)” set up inside the website to process the specific type of message: consultation. This not only improves the efficiency of processing the information of response, but also reduces the work pressure and the administration cost of the political system. It achieves success by replying to the consultation and receiving the highest satisfaction rate among all categories of public messages (There are four categories of public messages, as classified by the Beijing Municipal Government Website: consultation, suggestion, complaint and report.) “The knowledge base” works using a similar function as the database, automatically matching and providing answers to public consultations. If the transferer classifies the public message as consultation, it will be sent to the knowledge base for an automatic response without referring to the government departments. Rich information is contained in this. According to the interviews with Mr. Q, there are around 500,000 knowledge items inside the knowledge base. Based on their maturity, specificity and timeliness, these items are classified into three levels of complexity: high, middle and low. The highest level includes relatively fixed laws, regulations and work guidance, and the lowest level is mainly about time-sensitive information, which may change quickly. There are also ongoing updates regarding the format of the knowledge, with the purpose of facilitating an efficient response. This application improves the efficiency of responding to public messages, as it significantly reduces the workload of the political system. This successful innovation of the knowledge base illustrates two types of individual media system dependency relations: understanding and orientation [23]. Through the matching between the public consultation and the specific item contained in the knowledge base, the public achieves a better understanding of the social world by achieving an accurate perception of certain public policies in which they are interested. A typical example of this kind of understanding is consulting the website to understand the specific updates to the lottery policy for personal car number in Beijing. Some other benefits can be derived from the knowledge base to achieve effective orientation and ensure meaningful actions by following official instructions on dealing with complex situations; for example, consulting the specific steps of the household registration (hukou) relocation to Beijing. Mr. Q expressed the expectation that the public will fully take advantage of the knowledge base as follows:

“From the professional point of view, the knowledge base which we have established is like a database in the physical form. However, it is more like a service ecology (fuwu shengtai) as it can really release its value only if there are different roles in different fields to use this knowledge base from different perspectives”.

At a certain stage of the information process procedure, the automation of work significantly improves efficiency and reduces administration costs. The application of the knowledge base transfers the substantial working load from people to machines. The knowledge base can be regarded as an efficient information management system containing rich items of knowledge. The ability to access an efficient information system is not only significant for the survival of political organizations, but also a necessity for effective public action [23]. According to Mr. Z, the drafter of a government official document advocates the application of the knowledge base (this document refers to the <Notice of the General Office of the State Council on Issuing the Guidelines for the Development of Government Websites> published in 2017); this innovation actually borrows the idea of an initial knowledge base being used by the hotline, which assists in answering frequently asked questions by the public. The evolution of the knowledge base is introduced by Mr. Q; its initial form is an Excel table containing a descriptions of government responsibilities, which were copied from their official websites. This was further modified to the text format, in which information contained can be easily searched. After incorporating the ongoing updated knowledge, the current version is described by Mr. Q as “a knowledge graph (zhishi tupu)”, containing relatively rich information and a user-friendly navigation. The necessity of establishing such a knowledge base is demonstrated by working experience and required by official government documents. The interviews with Mr. W reveal that around 80% of the online public consultations concentrate on around 20% of the transactions, which can be answered in standard ways. The necessity of launching the knowledge base was also stressed in a central government official document in 2017 [42]. Therefore, long-term successful applications in other channels, to some extent, ensure the success of the knowledge base in online government response.

Inside the online media system, the setup of special positions can facilitate government departments in solving unstructured questions in the response process. The setup of the arbitrator (zhongcai ren) with the power of jurisdiction and arbitration represents not only the professionalization, but also the partial transfer of power from the political system to the online media system. Once there are disputes among government departments regarding their specific responsibilities, the arbitrator is responsible for the judgement and arbitration. As a third party, outside the government departments that are in dispute, the arbitrator exercises the power of arbitration to effectively avoid prevarication in disputes between government departments. In the past, a major flaw in the linear and continuous information processing within the government has been that once there is a problem or dispute at a certain point, the internal information processing cannot continue. A major breakthrough here is the outsourcing of some functions to the online media system through a professional and authoritative position-setting, such as via the arbitrator. This innovation effectively solves the defects in the traditional information system of public management, which mainly tackles the structural problems faced by managers, but cannot function when encountering unstructured and non-procedural problems [41]. Jurisdictional disputes are unstructured issues whose characteristics are not routine, procedural, operational or in a fixed causal relationship. The setup of arbitrators inside the online media system effectively remedies the defects in the traditional information system of public management regarding unstructured problems.

In the online media system, the independent arbitration function represents not only a new form of dependence, but also the partial transfer of power from the political system to the media system. This can resolve controversies caused by a lack of clarity regarding the government departments’ responsibilities. The setup of this position also illustrates the partial transfer of power from the political system to the online media system, with their major functions including the arbitration of jurisdiction and the coordination of collaboration between government departments. Before the design of this position, a continuous puzzle for the government was how to accurately distribute public messages containing diversified issues to the corresponding government departments and effectively solve the controversies regarding jurisdiction. The Beijing Municipal Government authorizes the official website, providing the power to resolve controversies regarding jurisdiction. When disagreements are raised by the processors (chuli ren) of government departments regarding the responsibilities of specific messages, these public messages will be sent back to arbitrators (zhongcai ren) at the website. It is their responsibility to resolve disputes by arbitrating which government department or institution should be in charge of the issue. In addition to the arbitration of jurisdiction, this position is also responsible for clarifying the necessity of collaborating with more than one government department, and, if so, deciding which department is in charge. Once the collaboration is formed, the department in charge takes the responsibility of allocating tasks among the collaborated departments and consolidating information to form the official reply. With these two functions, a new form of dependence, of the political system on the media system, goes beyond the traditional propaganda tool, undertaking a problem-solving role through partial power outsourcing. As Mr. Q explained, the purpose of setting the role of arbitrator is as follows:

“If the arbitrator believes that this matter must be resolved by the joint efforts of two government departments, he will transfer it to them and determine which departments is in charge as the work rule. The department that is in charge of the issue should take the initiative to follow up the updates and consolidate the results. The purpose is to avoid the worst situation that each department gives its individual reply. What if the replies conflict each other or both departments shirk the responsibility”?

The automation of effic iency control inside the online media system is combined with a certain level of flexibility to ensure the efficiency of the government’s response. This function mainly refers to the system supervision (xitong duban), which is one of a series of supervisions (duban) implemented by the online media system. According to the interviews with Mr. Q, this is conducted through the website to automatically record three time points, including the submission time of the public inquiries, the time at which the inquiries were sent to the government and the time at which a response was received from the government. There are official requirements regarding the speed of the government’s response: for example, three working days are the maximum time, in principle, for replies to public consultations [39]. Therefore, system supervision forms time constraints for the relevant government departments by keeping accurate time records. However, there are flexibilities contained in this supervision, as explained by Mr. Q:

“The public inquiries have different difficulties and backgrounds to be addressed. If the difficulty of addressing certain inquiry is relatively clear and the problem is indeed very complicated, the government department is allowed to provide us with a description and an application with the expectation of giving full consideration to the time limit or efficiency. Therefore, while the system fully calculates or supervises the average processing time, we treat difficult issues differently by not using the objective processing time as the single measure of efficiency and moderately referring to the quality of response”.

In addition to efficiency, the response’s quality is also valued, as both external stakeholders and professional positions are included in response supervision. Coordinated supervision (xietong duban) is conducted by a committee organized by the Department of the Interaction between the Public and Politics of the official website. Covering representatives of the National People’s Congress, members of the Chinese Political Consultative Conference and the registered users of the official website, this committee meets quarterly to evaluate if the public inquiries have been effectively addressed, and then provide written records. Another kind of supervision manual supervision (rengong duban) is conducted by assessors (pingjia ren), a professional position inside the online media system, once negative public feedback is received to official responses. This requires assessors to make the decision as to whether the message should be reprocessed based on the quality of the replies and the objectivity of the feedback. This kind of supervision also represents the dependence of the political system on the media system, as this requires the objectivity of professional assessors for the website. Mr. Q explained the necessity of manual supervision in an interview, as follows:

“As not everyone who posted the inquiry will participate into the satisfaction evaluation, there are some official replies with low quality receiving no satisfaction evaluation. It requires our staff to find out those government replies which do not meet the standard from their own operation and maintenance perspective”.

The responsibility of the arbitrator and the function of supervision represent a new form of dependence of the political system on the media system. This new form of dependence features a partial power transfer, including the arbitration power and the supervision power that the political system has over the online media system. This type of dependence is not exactly the dependency relationship presented in the traditional Chinese media context, in which the political system mainly relies on the media system for propaganda. The online media system plays a more active and functional role in resolving disputes, coordinating activities and supervising the political system. Jane Fountain once criticized American government officials in the 1990s for their lack of revolutionary thinking in using new technologies. Although they adopted information technology on the surface, they did not touch the deeper power relationships and the supervision processes [40]. Comparatively speaking, information technology seems to have been adopted by the Chinese government in a deeper and more revolutionary way; in this case, with power reallocation. This is a new means of information technology adoption: the government has made adjustments and transfers in the power relationship using the information technology. The online media system provides both professional and technical resources, which engender a new form of dependence on the political system. For professional resources, the official website sets up professional positions, such as an arbitrator, to resolve disputes redgarding jurisdiction and facilitate collaboration between departments. Regarding technical resources, the system supervision automatically records the timepoints at different response stages to monitor and ensure the government’s response efficiency. This new dependence relationship shifts the endeavor of improving state–society relations from its traditional focus on internal political system reform to the construction of an online media system.

To some extent, the online media system plays the role of an external information management system for the government, controlling the quality of the information. After the public message is processed by the relevant government department, the initial response should pass the assessor’s (pingjia ren) gatekeeping process to ensure its quality. With the assistance of this information management system, the online media system is mainly responsible for processing information, including classification, distribution, arbitration and gatekeeping. It simplifies the government’s task to focus only on responding to the information content. The reengineering of the response workflow has greatly simplified the role of government staff: they are only responsible for responding to the content of public inquiries for the issues under their jurisdiction, with a minimum level of information management responsibility.

4.2. Influential Factors

In addition to the processing of information, another valuable perspective to explain the online mechanism is the way in which the online mechanism structures information. This is represented by the classification of public messages and their connection to corresponding government departments. The structure established inside the online mechanism, to some extent, determines the variation in the content stress for the political system. This is supported by the response data showing that content pressure does exist for the political system, using evidence from the category of public messages and the category of government departments. According to the political system theory, content pressure is caused by the substance of the input and can have a negative impact on the political system [36]. The category of the message can influence the possibility of the government response leading to public satisfaction. Table 1 presents the results of multinomial logistic models. From Model 1 to Model 4, the goodness of fit gradually increases with an increasing trend of the pseudo-R square and a decreasing trend of the absolute value of log likelihood. Most of the independent variables significantly correlate with the dependent variable. In Model 4, compared to consultation, government response to suggestion is 13% less likely to receive satisfied feedback. Official replies to complaint are even less likely to satisfy the public, with the possibility being 23% smaller than the chance of achieving satisfaction through responding to a consultation. It could be presumed that the response to a message regarding certain public policies could be much easier than addressing a complaint regarding certain policy. Among the four categories of messages, it is most difficult to achieve public satisfaction through an official response to a report; this is 69% less likely to satisfy the public compared with the possibility of an ideal response to public consultation. Therefore, the hypothesis (H1a) that the category of online public message has a significant correlation with the level of public satisfaction with the government’s response is verified. This correlation is also partially due to the architecture of the mechanism constructed inside the online media. As Figure 1 shows, consultation is the only category of message that is directed by the transferer to the knowledge base, whereas other categories are transferred to the processor without a chance of receiving an automatic reply. Due to the accumulation of knowledge in the knowledge base, the responses to consultations are relatively standardized and controlled. However, with this mechanism’s architecture, the quality of responses to other categories, including advice, complaints and reports, highly depends on the function of the political system.

Table 1.

Multinomial logistic models of satisfaction in feedback to Chinese government response 1.

In addition to the category of messages, another perspective from which to view the influence of the input content is the category of government department. The reason for this is that similar public messages tend to be directed to the same department. The online mechanism consolidates information and distributes it across different government departments and institutions, which face different levels of content pressure to produce an ideal response, as the difficulties in forming a proper resolution vary across departments. This is also realized by practitioners in the online media system based on their own experiences. In the Media Mechanism section, Mr. Q admitted that public inquiries directed to different departments face different difficulties and have different backgrounds. The online media mechanism is constructed to contain flexibility regarding the time limits. The necessity of flexibility between the different departments is also verified by the quantitative results. The results of logistic regression confirm the significant correlation between the government department and whether the public is satisfied with the response in most cases (see Table 1). (In the original dataset, 83 government departments receive public messages and generate a response. To simplify the analysis, I classify 83 government departments into 12 categories according to the division of the responsibilities of vice mayors of the Beijing municipality (http://www.beijing.gov.cn/gongkai/sld/szfld/ (accessed on 2 March 2021)). Table 2 illustrates the classifications. As “12345 Citizen Hotline” is a separate channel connected to the Beijing Municipal Government Website, we treat this as an individual cluster.) Compared with the category of department Information and Financial Regulation, it is more than two times more likely for responses from the categories Urban Management, Public Security and Justice, Administrative District, Transportation and Technology to satisfy the public. Moreover, there are other categories of departments that can more easily generate an ideal response that will satisfy the public than Information and Financial Regulation, even though the gap is not as obvious as that between this department and the first four. The government departments Civil Affairs and Commerce and Human Resources, Agriculture and Health are 1.84 times and 1.40 times more likely, respectively, to provide responses which attract satisfied feedback compared to the category of Information and Financial Regulation. However, the responses obtained through Beijing 12345 Hotlines are 36% less likely to satisfy the public compared with responses generated by government departments in the category of Information and Financial Regulation. Therefore, the hypothesis (H1b) is supported, as the department can significantly influence the possibility of public satisfaction.

Table 2.

Department classification 1.

In addition to the content pressure, the processing time of the official response is important to achieving public satisfaction. This logic applies not only to the time the government takes to generate a response, but also to the time the online media system takes to process information related to this response, which highlights the significance of the online media system in producing an effective response. As introduced earlier for the political system theory, the greater the “lag” in the process, the smaller the possibility of the political system reaching the goal [31]. In the online response context, the “lag” can be understood as the time taken by both the political system and the media system to absorb, consider and process information before the government generates a response. While the adequate “gain” here refers to the extent to which the government reaction exactly matches the public’s request, which could ideally achieve public satisfaction. In the Beijing case, the processing time covers both the government processing time and the website processing time, which should be considered together. The regression results in Table 1 support the idea that both the government process time and the website process time are negatively correlated with the dependent variable of whether the public is satisfied. Therefore, the quicker the government can respond to public messages, the higher the possibility of achieving public satisfaction (p < 0.001 in Model 2b, p < 0.001 in Model 2c, p < 0.001 in Model 4). From the perspective of the website, a similar logic applies. The quicker the website can process public messages and government responses, the easier it is for the response to satisfy the public (p < 0.001 in Model 2a, p < 0.001 in Model 2c, p < 0.001 in Model 4). Therefore, both hypothesis (H2a) and hypothesis (H2b) are verified. The quantitative results show the necessity of creating professional positions, including transferer, arbitrator and assessor, and the establishment of a knowledge base. The purpose of the mechanism’s architecture is to improve the effectiveness of government responses through accelerating this process.

5. Conclusions

The innovative mechanism contained within the online media system increases the effectiveness of the government response. This innovation is mainly achieved through outsourcing the information management function and transferring part of the information processing power. This study contributes to the development of the media dependence theory through an analysis of the mechanism constructed inside the online media system in China. This newly constructed mechanism engenders new forms of dependence: with both the political system and individuals depending on the online media system. The political system outsources some information management functions to the online media system. The dependence of the political system on the online media system for a response is no longer in the form of traditional propaganda. This dependence is in a new form of functional dependence on the online media system to help the political system reduce administration costs, resolve disputes, coordinate cooperation and ensure the quality of the response information. It is realized through professional and technical resources provided from within the online media system. The mechanism’s innovations work together to form a new type of functional dependence of the political system on the online media system to modify state–society relations.

From the perspective of the political system theory, how the internet structures information can influence the effectiveness of the connection between the Chinese state and society in the form of government response. Both content pressure and time pressure exist for the political system in the online response process. The evidence supports the idea that the effectiveness of the response varies across different government departments as they face different levels of content pressure. Another typical way of structuring information, the category of public message, also impacts the effectiveness of the government response. Regarding government communication, a time pressure exists concerning the political system’s response, as the regression results demonstrate the public’s preference for quick information processing, both in the political system and on the website. They results also highlight the significance of information processing in the online media system.

New nuances emerge regarding the specific type of media dependence relationship and the operation logic of the political system. The online media system does not only improve the efficiency of government response, but also sets constraints and thresholds for the response quality. The new power balance between the political system and the online media system form a new type of functional dependence relationship. In this dependence relationship, both the position and function of the online media system have never been more prominent in the political system. The dependence of the political system on the media system changes from a tool-based propaganda logic to power reallocation and transfer. This is typically illustrated by the arbitration of controversies regarding responsibility, the gatekeeping of response quality and the mixed forms of supervision. The success of hypotheses-testing supports the existence of both a content pressure and time pressure for the political system during the response process. However, “public satisfaction”, as an indicator for the effectiveness of the government’s response, only offers one dimension of measurement. This can be somewhat subjective and not accurate. There is a demand for a systematic measurement method regarding the effectiveness of government response.

Although the response data are relatively rich, and could be analyzed for influential factors on public satisfaction, there are certain limitations to this study. This research focuses on the single case of Beijing, due to the limited resources. More fieldwork can be conducted elsewhere to explore other possibilities for innovation in both the media system and the political system. The study analyzes the mechanism of information processing in the media system, and the political system’s dependence on the media system. However, there is still a lack of research inside the government comparing operation and implementation across different departments or different municipalities. This comparative view could be valuable regarding both the theoretical implications and practical insights for government response research.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Z.L. and Q.M.; methodology, Z.L.; software, Z.L.; validation, Z.L.; formal analysis, Z.L.; investigation, Z.L.; resources, Q.M.; data curation, Q.M.; writing—original draft preparation, Z.L.; writing—review and editing, Z.L.; visualization, Z.L.; supervision, Q.M.; project administration, Z.L.; funding acquisition, Z.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the research funding of the Department of Service Standardization, China National Institute of Standardization and The APC was funded by the research funding of the Department of Service Standardization, China National Institute of Standardization.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy of the Official Website of the Beijing Municipal Government.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the support provided by Lida Wang, Hui Qiao, Shaotong Zhang and Youkui Wang for this research, especially in the coordination and acceptance of interviews and the access to data.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Chadwick, A. Internet Politics: States, Citizens, and New Communication Technologies; Huaxia Press: Beijing, China, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Coursey, D.; Norris, D.F. Models of E-Government: Are They Correct? An Empirical Assessment. Public Adm. Rev. 2008, 68, 523–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalathil, S. Open Networks, Closed Regimes: The Impact of the Internet on Authoritarian Rule; Carnegie Endowment for International Peace: Washington, DC, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Stockmann, D.; Gallagher, M.E. Remote control: How the media sustain authoritarian rule in China. Comp. Political Stud. 2011, 44, 436–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grossman, L.K. The Electronic Republic: Reshaping Democracy in the Information Age; Viking: New York, NY, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Taubman, G. A Not-So World Wide Web: The Internet, China, and the Challenges to Nondemocratic Rule. Political Commun. 1998, 15, 255–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y. Technological Empowerment: The Internet, State, and Society in China; Stanford University Press: Stanford, CA, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y. The Study of Government Response Process (zhengfu huiying guocheng yanjiu); The Chinese Social Science Press: Beijing, China, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Przeworski, A.; Susan, S.; Bernard, M. Democracy, Accountability, and Representation; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Starling, G. Managing the Public Sector; Wadsworth Publishing: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Ifeng. Available online: https://news.ifeng.com/c/404 (accessed on 3 March 2021).

- Sohu. Available online: http://news.sohu.com/20100816/n274251398.shtml (accessed on 3 March 2021).

- Kornreich, Y. Authoritarian responsiveness: Online consultation with “issue publics” in China. Governance 2019, 32, 547–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MIT. Available online: http://web.mit.edu/polisci/people/gradstudents/papers/Distelhorst_PDA_0927.pdf (accessed on 29 January 2021).

- Shirk, S.L. Changing Media, Changing China; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- China File. Available online: http://www.chinafile.com/library/nyrbchina-archive/china-back-future (accessed on 22 January 2021).

- The Central Government of the People’s Republic of China. Available online: http://www.gov.cn/zhengce/content/2019-04/18/content_5384134.htm (accessed on 20 January 2021).

- Beijing Municipal Government. Available online: http://www.beijing.gov.cn/zhengce/gfxwj/sj/201905/t20190522_58287.html (accessed on 20 January 2021).

- Su, Z.; Meng, T. Selective responsiveness: Online public demands and government responsiveness in authoritarian China. Soc. Sci. Res. 2016, 59, 52–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, J.; Pan, J.; Xu, Y. Sources of Authoritarian Responsiveness: A Field Experiment in China. Am. J. Political Sci. 2016, 60, 383–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, J.; Meng, T.; Zhang, Q. From Internet to social safety net: The policy consequences of online participation in China. Governance 2019, 32, 531–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Chinese Central Government. Available online: http://www.gov.cn/zhengce/content/2020-12/16/content_5569781.htm (accessed on 15 January 2021).

- De Fleur, M.L. Theories of Mass Communication; D. McKay Co.: New York, NY, USA, 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Ognyanova, K.; Ball-Rokeach, S.J. Political Efficacy on the Internet: A Media System Dependency Approach, Communication and Information Technologies Annual; Emerald Group Publishing Limited: New Delhi, India, 2015; Volume 9, pp. 3–27. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, B.; Zhang, D. Channel selection and knowledge acquisition during the 2009 Beijing H1N1 flu crisis: A media system dependency theory perspective. Chin. J. Commun. 2014, 7, 299–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luqiu, L.; Kang, Y. Loyalty to WeChat beyond national borders: A perspective of media system dependency theory on techno-nationalism. Chin. J. Commun. 2021, 14, 451–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahl, R.A. Polyarchy: Participation and Opposition; Yale University Press: New Haven, CT, USA, 1971. [Google Scholar]

- Easton, D. An Approach to the Analysis of Political Systems. World Politics 1957, 9, 383–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almond, G.A.; Oleman, J.S. The Politics of the Developing Areas; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Deutsch, K. Politics and Government: How People Decide Their Fate; Houghton Mifflin: Boston, MA, USA, 1970. [Google Scholar]

- Deutsch, K.W. The Nerves of Government; Models of Political Communication and Control; Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 1966. [Google Scholar]

- Benney, M.; Hughes, E.C. Of Sociology and the Interview: Editorial Preface. Am. J. Sociol. 1956, 62, 137–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kvale, S. Interviews: An Introduction to Qualitative Research Interviewing; Sage: London, UK, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Gunter, B. Media Research Methods: Measuring Audiences, Reactions and Impact; Sage: London, UK, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Gubrium, J.F.; Holstein, J. Handbook of Interview Research: Context and Method; SAGE Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Easton, D. A Systems Analysis of Political Life; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 1965. [Google Scholar]

- Mellon, H. Deutsch re-visited: Government as communication and learning. Can. Public Adm. 2003, 46, 390–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The General Office of the State Council. Available online: https://www.gov.cn/zhengce/content/2018-11/09/content_5338761.htm (accessed on 15 January 2021).

- Beijing Municipal Government. Available online: http://www.gov.cn/xinwen/2019-04/28/content_5387054.htm (accessed on 15 January 2021).

- Fountain, J. Building the Virtual State: Information Technology and Institutional Change; Brookings Institution Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Hughes, O.E. Public Management and Administration: An Introduction; The Press of the People’s University of China: Beijing, China, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- The Central Government of the People’s Republic of China. Available online: http://www.gov.cn/zhengce/content/2017-06/08/content_5200760.htm (accessed on 4 April 2021).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).