Changes in Consumption Patterns and Tourist Promotion after the COVID-19 Pandemic

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Consumer Behaviour and Tourism Marketing during COVID-19

- Presentation and interaction: website, apps, blogs, podcasts.

- Communication: social networks, web series, online platforms.

- For sale: e-commerce, social networks, marketplaces, blockchains.

- Strategic: SEO (search engine optimization), SEM (search engine marketing), content marketing, attraction marketing.

- Analysis and measurement: data generation, big data, metrics, key performance indicators (KPIs), analytics, data services. Monitoring of the actions carried out and adoption of new KPIs. Using big data techniques and the use of chatbots, customers’ needs and decisions are analysed and future lines of action are redefined [36].

- The online service quality, such as the time of delivery;

- Attitude toward the use of online buying;

- Satisfaction with the online services;

- Ease of using the online platform.

2.2. Changes Detected in the Promotion of the Tourist Destination during COVID-19

- Introduce and adapt actionable and harmonized processes and procedures in line with public health evidence based risk assessment and full coordination with relevant public and private sector partners.

- Support companies in the implementation and training of their staff on the new protocols (financing and training).

- Enhance the use of technology for safe, seamless and touchless travel in your destination. A critical element in the reorganisation of the industry will involve the increased incorporation of automation technologies [57].

- Provide reliable, consistent and easy to access information on protocols to the private sector and to travellers (send SMS—short messages service—to tourists to inform them of national and local heath protocols and relevant health contacts).

- Create programs and campaigns to incentivise the domestic market in cooperation with the private sector (incentive schemes, possible revision of holiday dates, transport facilities, vouchers, etc.) and integrate destinations.

- Promote new products and experiences targeted at individual and small groups of travellers, such as: special interest, nature, rural tourism, gastronomy and wine, sports, etc. [58].

- Consider the data privacy policies when there is a proposal of developing tracing apps. The WHO (World Health Organization) will develop guidance on the use of digital technologies for contact tracing?

- Ensure coordination among tourism, health and transport policies.

- Define roles and responsibilities for governments, private sector and travellers.

2.3. Digital Marketing as a Business Support Tool during the Pandemic

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Sample

3.2. Data Collection

- Section I:

- ⚬

- Sources of information and communication channels

- ⚬

- Online shopping experience

- ⚬

- Role of new technologies

- Section II:

- ⚬

- Changes in marketing

- ⚬

- Changes in the promotion

- Have there been changes in tourism marketing after the pandemic? Which ones?

- Have there been changes in tourism promotion after the pandemic? Which ones?

3.3. Data Analysis

4. Results

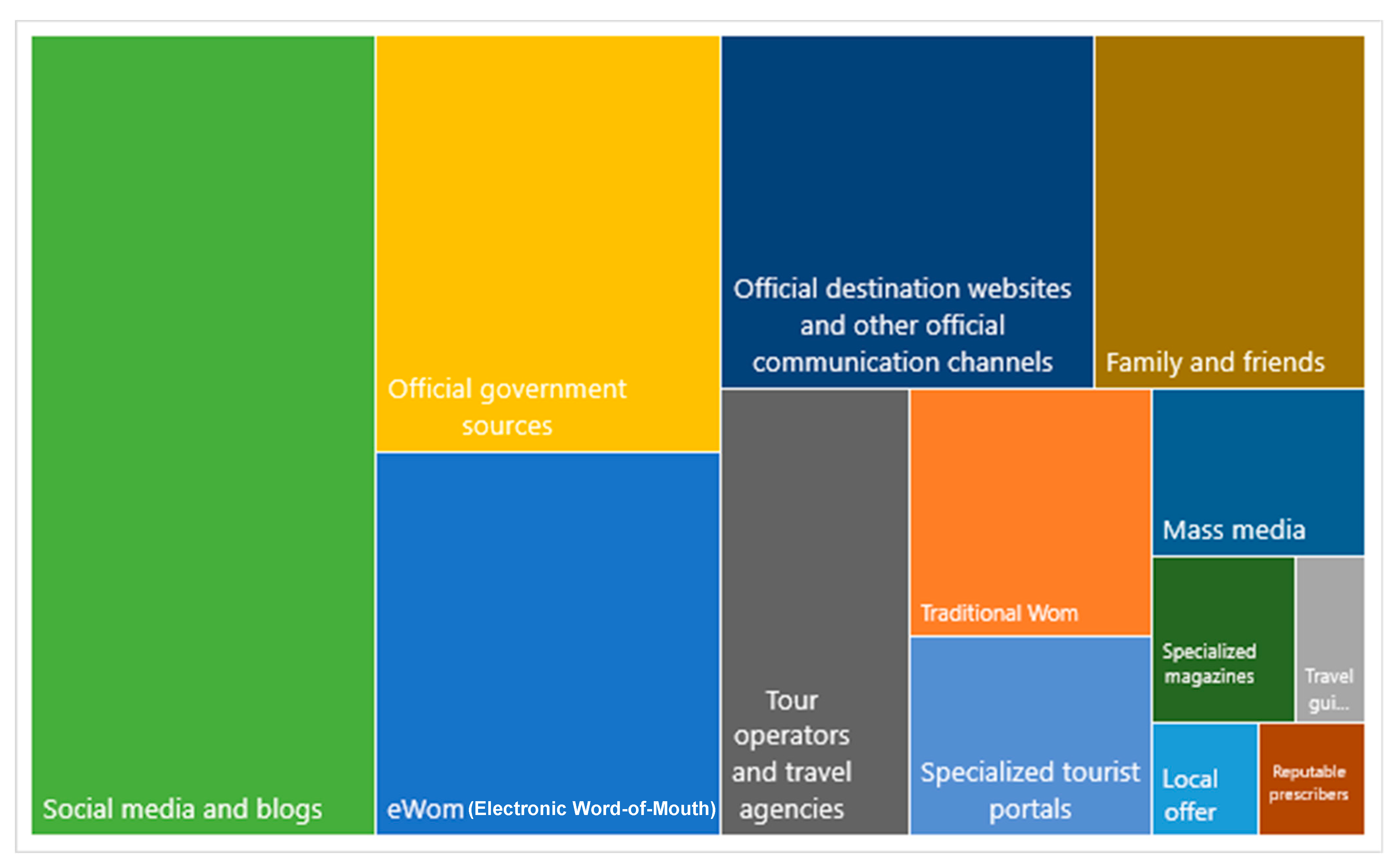

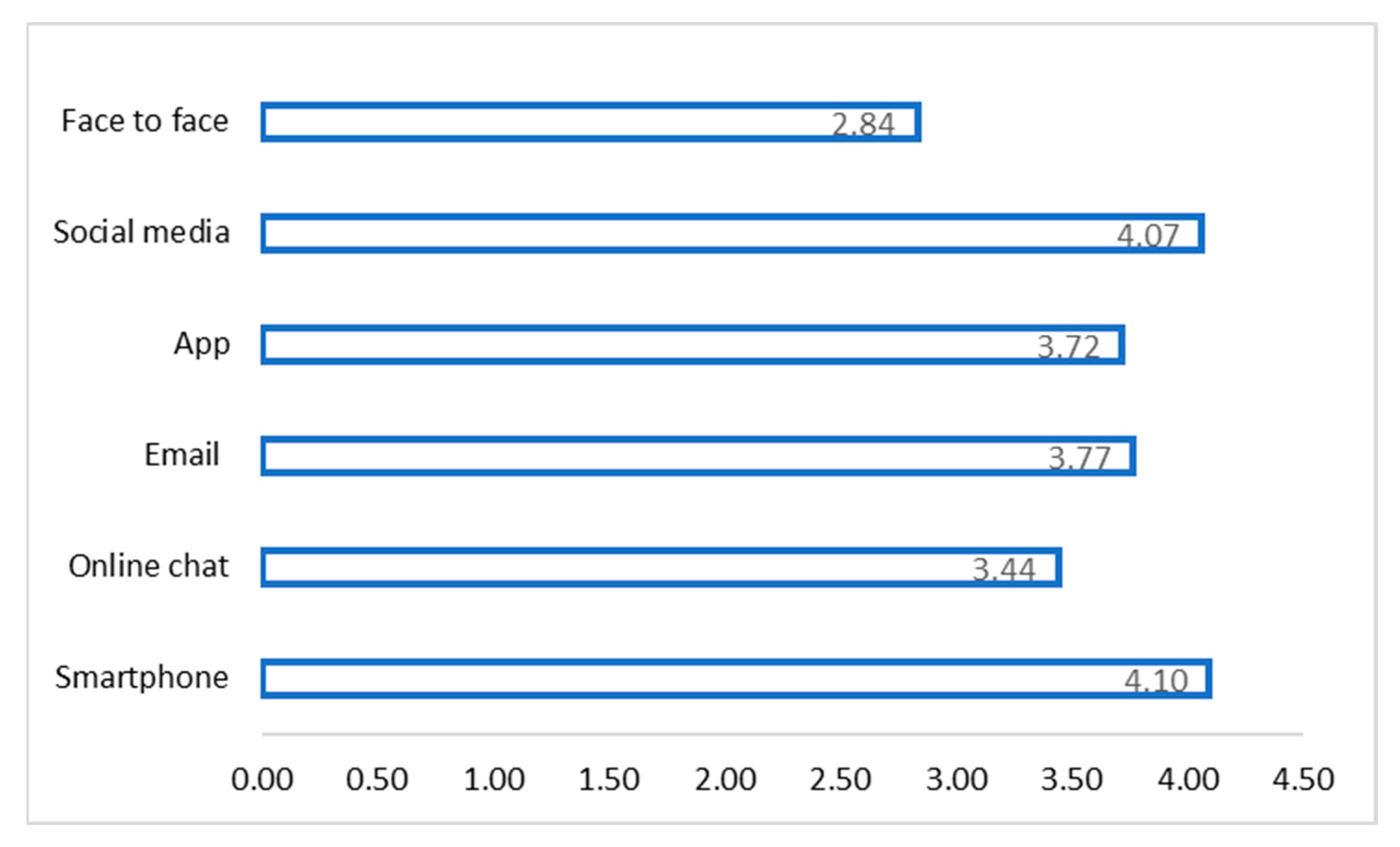

4.1. Sources of Information, Communication Channels and New Technologies

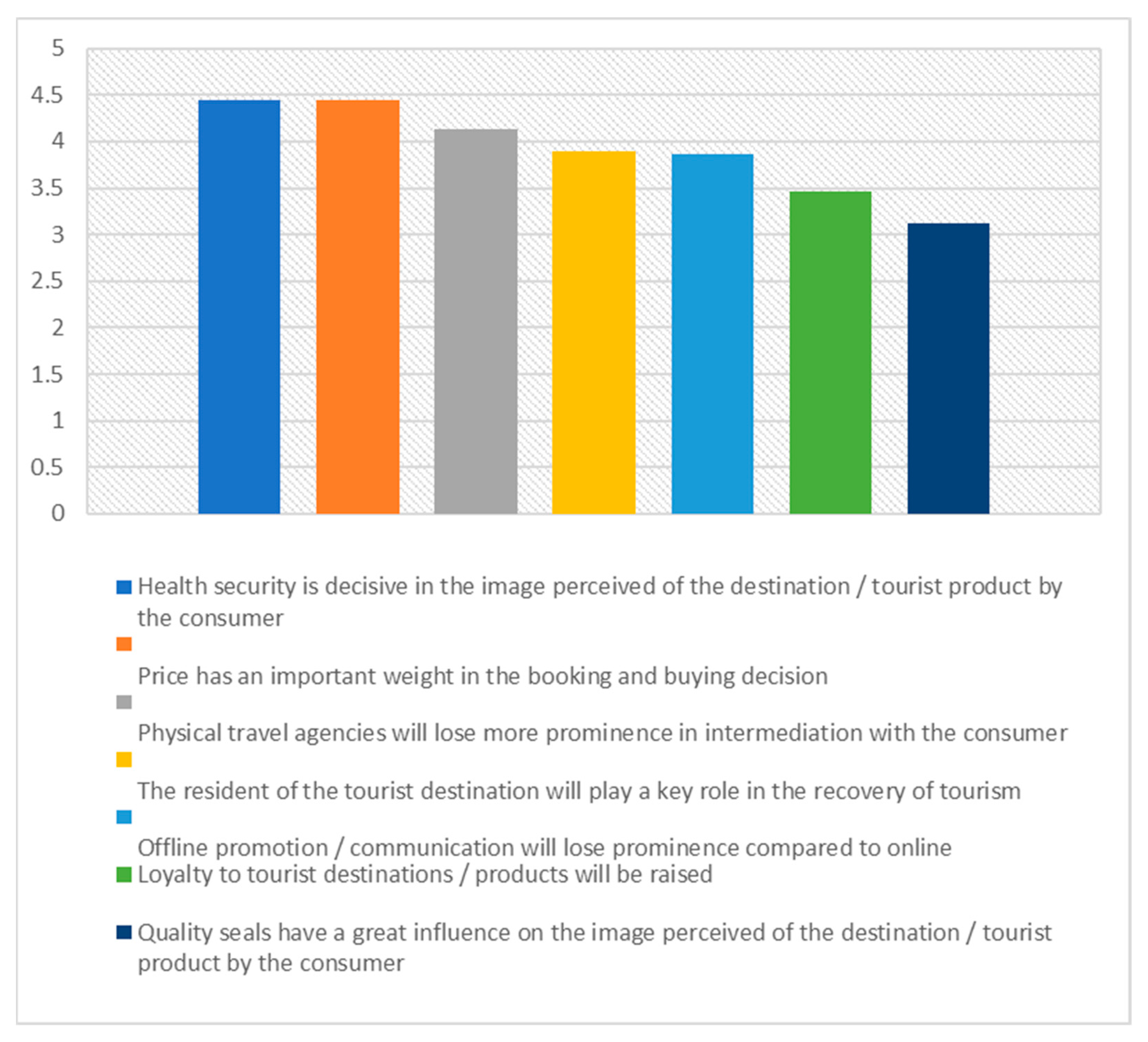

4.2. Expected Changes in Tourism Marketing

- Flexibility and transparency in trade policies were a requirement during the pandemic. The client will hardly understand a reversal in this regard.

- A greater prominence—more power—is expected from the final tourist as opposed to the current prominence of the intermediaries.

- Increased traveller attention to safe destinations.

- Increased importance of the experience attribute and emotions.

- Increased exchange of information between consumers (P2P—peer to per—networks).

- Increased awareness of environmental sustainability and landscape and heritage preservation.

4.3. Expected Changes in Destination Promotion

- For a long period, we will have important quotas of local demand that will determine the promotion of the tourist destination.

- We will see a shift from traditional to digital media budgets. This means a change in promotion strategies, from the traditional tourist fairs or general advertising campaigns towards digital and defined strategies. Online commercial communication will increase in all segments. Traditional commercial communication may continue to be used in mature segments.

- In a scenario of increased competition to capture the attention of markets, apparently opposing strategies can coexist, that is, personalized promotions aimed at small niches with the use of mass media, online and offline. In this sense, “the organization of singular events that stimulate the involvement of the consumer or potential visitor can be interesting for the future” (participant 56).

- Greater transversality will be perceived through the incorporation of “non-tourist” agents and elements, indispensable for the increased demand from tourists.

5. Discussion and Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Gaffney, C.; Eeckels, B. COVID-19 and Tourism Risk in the Americas. J. Lat. Am. Geogr. 2020, 19, 308–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogerson, C.M.; Baum, T. COVID-19 and African tourism research agendas. Dev. S. Afr. 2020, 37, 727–741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ardiansyah, M. The impact of corona virus disease (Covid-19) on Indonesia tourism. Media Bina Ilm. 2020, 15, 4321–4328. [Google Scholar]

- Slyvenko, V.; Slyvenko, O. Economic security of tourism in Germany: Models for overcoming the crisis. Eur. J. Manag. Issues 2020, 28, 110–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. OECD Tourism Trends and Policies 20202. Key Findings; OECD and Europe Union: Paris, France, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Gössling, S.; Scott, D.; Hall, C.M. Pandemics, tourism and global change: A rapid assessment of COVID-19. J. Sustain. Tour. 2020, 29, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niewiadomski, P. COVID-19: From temporary de-globalisation to a re-discovery of tourism? Tour. Geogr. 2020, 22, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polyzos, S.; Samitas, A.; Spyridou, A.E. Tourism demand and the COVID-19 pandemic: An LSTM approach. Tour. Recreat. Res. 2020, 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Baker, S.R.; Bloom, N.; Davis, S.J.; Terry, S.J. Covid-Induced Economic Uncertainty; National Bureau of Economic Research: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2020; p. 26983. [Google Scholar]

- Calveras, J. Economía de un destino turístico seguro en tiempos de pandemia: El caso del todo incluido en las Islas Baleares. In Turismo Pos-COVID-19, Reflexiones, Retos y Oportunidades; Simancas, M., Hernández, R., Padron, N., Eds.; Cátedra de Turismo CajaCanarias-Ashotel de la Universidad de La Laguna: Islas Canarias, Spain, 2020; pp. 489–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Extremera, N. Coping with the stress caused by the COVID-19 pandemic: Future research agenda based on emotional intelligence. Int. J. Soc. Psychol. 2020, 35, 631–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosteltur. La COVID Cambia las Vacaciones de los Españoles: Se Dispara el Last Minute. 2020. Available online: https://www.hosteltur.com/138610_la-covid-cambia-las-vacaciones-de-los-espanoles-se-dispara-el-last-minute.html (accessed on 18 January 2021).

- Travel Consul. New Global Study Reveals That Destination Health Certifications Inspire Confidence among Travel Advisors and Their Clients. 2020. Available online: https://www.travelconsul.com/blog/new-global-study-reveals-destination-health-certifications-inspire-confidence-among-travel (accessed on 20 January 2021).

- Hall, M.C.; Prayag, G.; Fieger, P.; Dyason, D. Beyond panic buying: Consumption displacement and COVID-19. J. Serv. Manag. 2020, 32, 113–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhatti, A.; Akram, H.; Basit, H.M.; Khan, A.U.; Raza, S.M.; Naqvi, M.B. E-commerce trends during COVID-19 Pandemic. Int. J. Future Gener. Commun. Netw. 2020, 13, 1449–1452. [Google Scholar]

- Watanabe, T.; Omori, Y. Online consumption during the covid-19 crisis: Evidence from Japan. Covid Econ. 2020, 38, 218–252. [Google Scholar]

- Khwaja, M.G.; Zaman, U. Configuring the evolving role of ewom on the consumers information adoption. J. Open Innov. Technol. Mark. Complex. 2020, 6, 125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kock, F.; Nørfelt, A.; Josiassen, A.; Assaf, A.G.; Tsionas, M.G. Understanding the COVID-19 tourist psyche: The evolutionary tourism paradigm. Ann. Tour. Res. 2020, 85, 103053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kantar. Coronavirus Outbreak’s Impact on China’s Consumption. 2020. Available online: https://mp.weixin.qq.com/s/OptUHteL3zGVHahnDolRDg (accessed on 15 January 2021).

- Kim, J. Impact of the perceived threat of COVID-19 on variety-seeking. Australas. Mark. J. 2020, 28, 108–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malfitano, A.P.S.; Cruz, D.M.C.D.; Lopes, R.E. Occupational therapy in times of pandemic: Social security and guaranties of possible everyday life for all. Cad. Bras. Ter. Ocup. 2020, 28, 401–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matyakubov, U.R.; Ibadullaev, E.B. Exploring the Impact of the Coronavirus Pandemic on Tourism and Recreational Services: Case from Republic of Uzbekistan. Sci. Res. Dev. 2020, 32, 168–171. [Google Scholar]

- Dinarto, D.; Wanto, A.; Sebastian, L.C. Global Health Security–COVID-19: Impact on Bintan’s Tourism Sector, Rsis Commentaries; NanyangTechnological University: Singapore, 2020; pp. 20–33. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson, M.E.; Chen, L.H. Re-starting travel in the era of COVID-19: Preparing anew. J. Travel Med. 2020, 27, 108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, M.C.; Inman, J.J.; Kirmani, A.; Price, L.L. In times of trouble: A framework for understanding consumers’ responses to threats. J. Consum. Res. 2020, 47, 311–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galoni, C.; Carpenter, G.S.; Rao, H. Disgusted and afraid: Consumer choices under the threat of contagious disease. J. Consum. Res. 2020, 47, 373–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pennycook, G.; McPhetres, J.; Zhang, Y.; Lu, J.G.; Rand, D.G. Fighting COVID-19 misinformation on social media: Experimental evidence for a scalable accuracy-nudge intervention. Psychol. Sci. 2020, 31, 770–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naidoo, V. Firm survival through a crisis: The influence of market orientation, marketing innovation and business strategy. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2010, 39, 1311–1320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rutynskyi, M.; Kushniruk, H. The impact of quarantine due to COVID-19 pandemic on the tourism industry in Lviv (Ukraine). Probl. Perspect. Manag. 2020, 18, 194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosteltur. Los Bonos Turísticos del País Vasco Tendrán Vigencia Hasta Mayo de 2021. Available online: https://www.hosteltur.com/140184_los-bonos-turisticos-del-pais-vasco-tendran-vigencia-hasta-mayo-de-2021.html (accessed on 15 January 2021).

- Nunes, S.; Cooke, P. New global tourism innovation in a post-coronavirus era. Eur. Plan. Stud. 2020, 29, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Teba, E.M.; García-Mestanza, J.; Rodríguez-Fernández, M. The Application of the Inbound Marketing Strategy on Costa del Sol Planning & Tourism Board. Lessons for Post-COVID-19 Revival. Sustainability 2020, 12, 9926. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Hong, A.; Li, X.; Gao, J. Marketing innovations during a global crisis: A study of China firms’ response to COVID-19. J. Bus. Res. 2020, 116, 214–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, C.K.; Rakshit, P. A critical analysis to comprehend panic buying behaviour of Mumbaikar’s in COVID-19 era. Stud. Indian Place Names 2020, 40, 44–51. [Google Scholar]

- Talaya, Á.E.; Romero, C.L. Dirección comercial; ESIC Editorial: Madrid, Spain, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Martínez, S. Redes sociales y big data. Una oportunidad para la recuperación de los mercados turísticos. In El Turismo Después de la Pandemia Global: Análisis, Perspectivas y Vías de Recuperación; Bauzá, F.J., Melgosa, F.J., Eds.; Asociación Española de Expertos Científicos en Turismo, AECIT: Madrid, Spain, 2020; pp. 85–94. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Ghraibah, O.B. Online Consumer Retention in Saudi Arabia During COVID 19: The Moderating Role of Online Trust. J. Crit. Rev. 2020, 7, 2464–2472. [Google Scholar]

- Vargas, A. Covid-19 crisis: A new model of tourism governance for a new time. Worldw. Hosp. Tour. Themes 2020, 12, 691–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renault, S. Les enjeux du crowdmarketing: Le cas Mobeye. Rev. Manag. Des. Technol. Organ. 2016, 6, 153–166. [Google Scholar]

- Williams, A.M.; Baláž, V. Riesgo e incertidumbre turísticos: Reflexiones teóricas. Rev. Investig. Viajes 2015, 54, 271–287. [Google Scholar]

- Gallego, I.; Font, X. Changes in air passenger demand as a result of the COVID-19 crisis: Using Big Data to inform tourism policy. J. Sustain. Tour. 2020, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donthu, N.; Gustafsson, A. Effects of COVID-19 on business and research. J. Bus. Res. 2020, 117, 284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matiza, T. Post-COVID-19 crisis travel behaviour: Towards mitigating the effects of perceived risk. J. Tour. Futures 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Streimikiene, D.; Korneeva, E. Economic impacts of innovations in tourism marketing. Terra Econ. 2020, 18, 182–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohanty, P.; Hassan, A.; Ekis, E. Augmented reality for relaunching tourism post-COVID-19: Socially distant, virtually connected. Worldw. Hosp. Tour. Themes 2020, 12, 753–760. [Google Scholar]

- Félix, A.; Reinoso, N.G.; Vera, R. Participatory diagnosis of the tourism sector in managing the crisis caused by the pandemic (COVID-19). Rev. Interam. Ambiente Tur. Talca 2020, 16, 66–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Zhang, X.; Huang, S.; Zhang, L.; Zhao, Y. Exploring consumers’ buying behavior in a large online promotion activity: The role of psychological distance and involvement. J. Theor. Appl. Electron. Commer. Res. 2020, 15, 66–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gruzd, A.; Staves, K.; Wilk, A. Tenure and promotion in the age of online social media. Proc. Am. Soc. Inf. Sci. Technol. 2011, 48, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akram, U.; Hui, P.; Khan, M.K.; Tanveer, Y.; Mehmood, K.; Ahmad, W. How website quality affects online impulse buying: Moderating effects of sales promotion and credit card use. Asia Pac. J. Mark. Logist. 2018, 30, 235–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKercher, B.; Chon, K. The over-reaction to SARS and the collapse of Asian Tourism. Ann. Tour. Res. 2004, 31, 716–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huynh, T.L. The COVID-19 risk perception: A survey on socioeconomics and media attention. Econ. Bull. 2020, 40, 758–764. [Google Scholar]

- Andersen, K.G.; Rambaut, A.; Lipkin, W.I.; Holmes, E.C.; Garry, R.F. The proximal origin of SARS-CoV-2. Nat. Med. 2020, 26, 450–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pine, R.; McKercher, B. The impact of SARS on Hong Kong’s tourism industry. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2004, 16, 139–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Black, M. The experience of the first sanitary revolution: Are there lessons for today’s global sanitation crisis? Waterlines 2008, 27, 62–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araújo, V.N.; Fraiz, B.J.A.; Toubes, D. El turismo pos-coronavirus en Galicia. Plan de reactivación. In Turismo pos-COVID-19. Reflexiones, Retos y Oportunidades; Simancas, M., Hernández, Padron, N., Eds.; Cátedra de Turismo CajaCanarias-Ashotel de la Universidad de La Laguna, Islas Canarias: Madrid, Spain, 2020; pp. 201–210. Available online: https://doi.org/10.25145/b.Turismopos-COVID-19.2020 (accessed on 18 January 2021).

- UNWTO. Turismo y COVID-19, Prioridades de la OMT para la Recuperación del Turismo; Organización Mundial del Turismo: Madrid, Spain, 2020; Available online: https://webunwto.s3.eu-west-1.amazonaws.com/s3fs-public/2020–06/200606%20-%20UNWTO%20Global%20Guidelines%20to%20Restart%20Tourism%20ES.pdf (accessed on 18 January 2021).

- Ivanov, S.; Webster, C.; Stoilova, E.; Slobodskoy, D. Biosecurity, automation technologies and economic resilience of travel, tourism and hospitality companies. Tour. Econ. 2020. In press. [Google Scholar]

- Ateljevic, I. Transforming the (tourism) world for good and (re) generating the potential ‘new normal’. Tour. Geogr. 2020, 22, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Antón, J.M.; Alonso-Almeida, M.D.M. COVID-19 Impacts and Recovery Strategies: The Case of the Hospitality Industry in Spain. Sustainability 2020, 12, 8599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López, I.S. Los retos del turismo cultural en la ciudad de Santander para convertirse en un destino seguro pos-COVID-19. Estud. Turísticos 2020, 219, 59–70. [Google Scholar]

- De Oliveira Santos, D.P. Tarjeta turística safety and security: El pasaporte para turistas y destinos seguros. Cuad. Tur. 2020, 46, 489–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, J.; Kozak, M.; Yang, S.; Liu, F. COVID-19: Potential effects on Chinese citizens’ lifestyle and travel. Tour. Rev. 2020, 76, 74–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Zhao, Q.; Huo, T.; Shao, Y.; Hu, Z. COVID-19: Management focus of reopened tourist destinations. Curr. Issues Tour. 2020, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seyfi, S.; Hall, C.M.; Shabani, B. COVID-19 and international travel restrictions: The geopolitics of health and tourism. Tour. Geogr. 2020, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sigala, M. Tourism and COVID-19: Impacts and implications for advancing and resetting industry and research. J. Bus. Res. 2020, 117, 312–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brouder, P. Reset redux: Possible evolutionary pathways towards the transformation of tourism in a COVID-19 world. Tour. Geogr. 2020, 22, 484–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Huang, X.; Li, Z. A content analysis of Chinese news coverage on COVID-19 and tourism. Curr. Issues Tour. 2020, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, D.; Luo, Q.; Ritchie, B.W. Afraid to travel after COVID-19? Self-protection, coping and resilience against pandemic ‘travel fear’. Tour. Manag. 2020, 83, 104261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, G.D.; Thomas, A.; Paul, J. Reviving tourism industry post-COVID-19: A resilience-based framework. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2020, 37, 100786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, X.M. Posibles impactos de la crisis generada por la COVID-19 sobre el Camino de Santiago. In Turismo pos-COVID-19. Reflexiones, Retos y Oportunidades; Simancas, M., Hernández, R., Padron, N., Eds.; Cátedra de Turismo CajaCanarias-Ashotel de la Universidad de La Laguna: Islas Canarias, Spain, 2020; pp. 571–580. Available online: https://doi.org/10.25145/b.Turismopos-COVID-19.2020 (accessed on 18 January 2021).

- Henderson, J.C. Managing a tourism crisis in Southeast Asia: The role of National Tourism Organisations. Int. J. Hosp. Tour. Adm. 2002, 3, 85–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dore, L.; Crouch, G.I. Promoting destinations: An exploratory study of publicity programmes used by National Tourism Organizations. J. Vacat. Mark. 2003, 9, 137–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoyos-Estrada, S.; Sastoque-Gómez, J.D. Marketing Digital como oportunidad de digitalización de las PYMES en Colombia en tiempo del Covid–19. Rev. Científica Anfibios 2020, 3, 39–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotler, P. Marketing 4.0: Dal tradizionale al digitale. In Marketing 4.0; Koepli: Milano, Italy, 2017; pp. 1–168. [Google Scholar]

- González-Bríñez, M.H. El Marketing Digital Transforma La Gestión De Pymes En Colombia. Cuad. Latinoam. Adm. 2019, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garello, F.A. Tendencias del Marketing Digital Desde la Perspectiva de las Pymes. Bachelor’s Thesis, Universidad Empresarial Siglo 21, Córdoba, Argentina, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Flores Torres, R.; Galarza Uzcátegui, A. Importancia de la Reputación Online para Una PYME. 2014. Available online: http://201.159.223.2/handle/123456789/938 (accessed on 18 January 2021).

- Kim, R.Y. The impact of COVID-19 on consumers: Preparing for digital sales. IEEE Eng. Manag. Rev. 2020, 48, 212–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hardy, Q. COVID-19 and Our Surprising Digital Transformation, Forbes. 2020. Available online: https://www.forbes.com/sites/googlecloud/2020/03/11/beyond-spreadsheets/#401e43c76c7f (accessed on 18 January 2021).

- Anyan, F. The Influence of Power Shifts in Data Collection and Analysis Stages: A Focus on Qualitative Research Interview. Qual. Rep. 2013, 18, 36. [Google Scholar]

- Holstein, J.A.; Gubrium, J.F. Context: Working it up, down and across. In Qualitative Research Practice; Sage Publication: London, UK, 2004; pp. 297–311. [Google Scholar]

- Nunkoosing, K. The problems with interviews. Qual. Health Res. 2005, 15, 698–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kvale, S. The qualitative research interview. J. Phenomenol. Psychol. 1983, 14, 171–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merriam, S.B. Qualitative Research: A Guide to Design and Implementation; Josseybass: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Sierra López, A. Métodos Cualitativos de Investigación en Turismo. Available online: https://www.scribd.com/doc/46910113/Metodos-Cualitativos-de-Investigacion-en-Turismo-Metodo-Delphi (accessed on 18 January 2021).

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, H.; Harris, L. The impact of Covid-19 pandemic on corporate social responsibility and marketing philosophy. J. Bus. Res. 2020, 116, 176–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gitelson, R.; Kerstetter, D. The influence of friends and relatives in travel decision-making. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 1995, 3, 59–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, L.; Mascardo, G.; Benckendorff, P. Exploring word-of-mouth influences on travel decisions: Friends and relatives vs. other travellers. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2007, 31, 517–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, B.; Ye, Q.; Kucukusta, D.; Law, R. Analysis of the perceived value of online tourism reviews: Influence of readability and reviewer characteristics. Tour. Manag. 2016, 52, 498–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgins-Desbiolles, F. The “war over tourism”: Challenges to sustainable tourism in the tourism academy after COVID-19. J. Sustain. Tour. 2020, 29, 551–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Law, R. The Perceived Impact of Risks in Travel Decisions. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2006, 8, 289–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mäser, B.; Weiermair, K. Travel decision making: From the vantage point of perceived risk and information preferences. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 1998, 7, 107–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slevitch, L.; Sharma, A. Management of perceived risk in the context of destination choice. Int. J. Hosp. Tour. Adm. 2008, 9, 85–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawton, L.J.; Weaver, D.B. Travel agency threats and opportunities: The perspective of successful owners. Int. J. Hosp. Tour. Adm. 2009, 10, 68–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- ETC. Handbook on COVID-19 Recovery Strategies for National Tourism Organizations. European Travel Commission. Brussels, ETC Market. Intelligence. 2020. Available online: https://etc-corporate.org/reports/handbook-on-covid-19-recovery-strategies-for-national-tourism-organisations/ (accessed on 18 January 2021).

| Element | Action |

|---|---|

| Hardware | Nearly 90% of consumer transactions start and end on an electronic device, primarily mobile devices such as tablets and smartphones. |

| Content marketing | The information provided by the website and/or social networks must be real and in line with what is offered, so it will be possible to ensure the return of customers (customer loyalty). |

| Organic search | Customer use of search engines. It is necessary to achieve high visibility and traffic on the website, attract and persuade customers. |

| E-mail marketing | An appropriate e-mail campaign allows you to close a deal with a potential customer, for this it is necessary to have content that can convince the customer. |

| Social media marketing | The first step of the contact with the customer lies in the social networks, in this step an interaction between the brand and the user is established. |

| Web development | The website presents the business and must detail everything it offers because on social networks only the ad is shown. |

| Corporate image | This point is essential for the business as it allows the establishment of an identity and recognition among users. |

| Positioning in Google | A ranking within the search engines will not only give visibility to the brand, it will also give confidence and security. |

| SEO (Search Engine Optimization) | Through organic growth, it aims to improve the position of a website in search engine results for specific search terms that relate directly to the business. |

| SEM (Search Engine Marketing) | In this case it improves the position of the website through paid advertising. It allows the site to be shown in the first positions when the user searches for a specific item. |

| Advertising campaigns | The medium and mode of dissemination are decisive to reach potential customers, and it is possible to know the customers’ tastes thanks to the data shared by users and reactions to the published content. |

| Participants | Sample |

|---|---|

| University and Technology Centres | 25 |

| Business consultancy | 11 |

| Restaurant business | 12 |

| Rural tourism | 5 |

| Tourist accommodation | 7 |

| Winery-Enotourism | 4 |

| Media | 1 |

| Total | 65 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Toubes, D.R.; Araújo Vila, N.; Fraiz Brea, J.A. Changes in Consumption Patterns and Tourist Promotion after the COVID-19 Pandemic. J. Theor. Appl. Electron. Commer. Res. 2021, 16, 1332-1352. https://doi.org/10.3390/jtaer16050075

Toubes DR, Araújo Vila N, Fraiz Brea JA. Changes in Consumption Patterns and Tourist Promotion after the COVID-19 Pandemic. Journal of Theoretical and Applied Electronic Commerce Research. 2021; 16(5):1332-1352. https://doi.org/10.3390/jtaer16050075

Chicago/Turabian StyleToubes, Diego R., Noelia Araújo Vila, and Jose A. Fraiz Brea. 2021. "Changes in Consumption Patterns and Tourist Promotion after the COVID-19 Pandemic" Journal of Theoretical and Applied Electronic Commerce Research 16, no. 5: 1332-1352. https://doi.org/10.3390/jtaer16050075

APA StyleToubes, D. R., Araújo Vila, N., & Fraiz Brea, J. A. (2021). Changes in Consumption Patterns and Tourist Promotion after the COVID-19 Pandemic. Journal of Theoretical and Applied Electronic Commerce Research, 16(5), 1332-1352. https://doi.org/10.3390/jtaer16050075