Implementation of Website Marketing Strategies in Sports Tourism: Analysis of the Online Presence and E-Commerce of Golf Courses

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Golf and the Tourist Industry

3. Methods

3.1. Web Content Analysis (WCA)

3.2. Extended Model of Internet Commerce Adoption (eMICA)

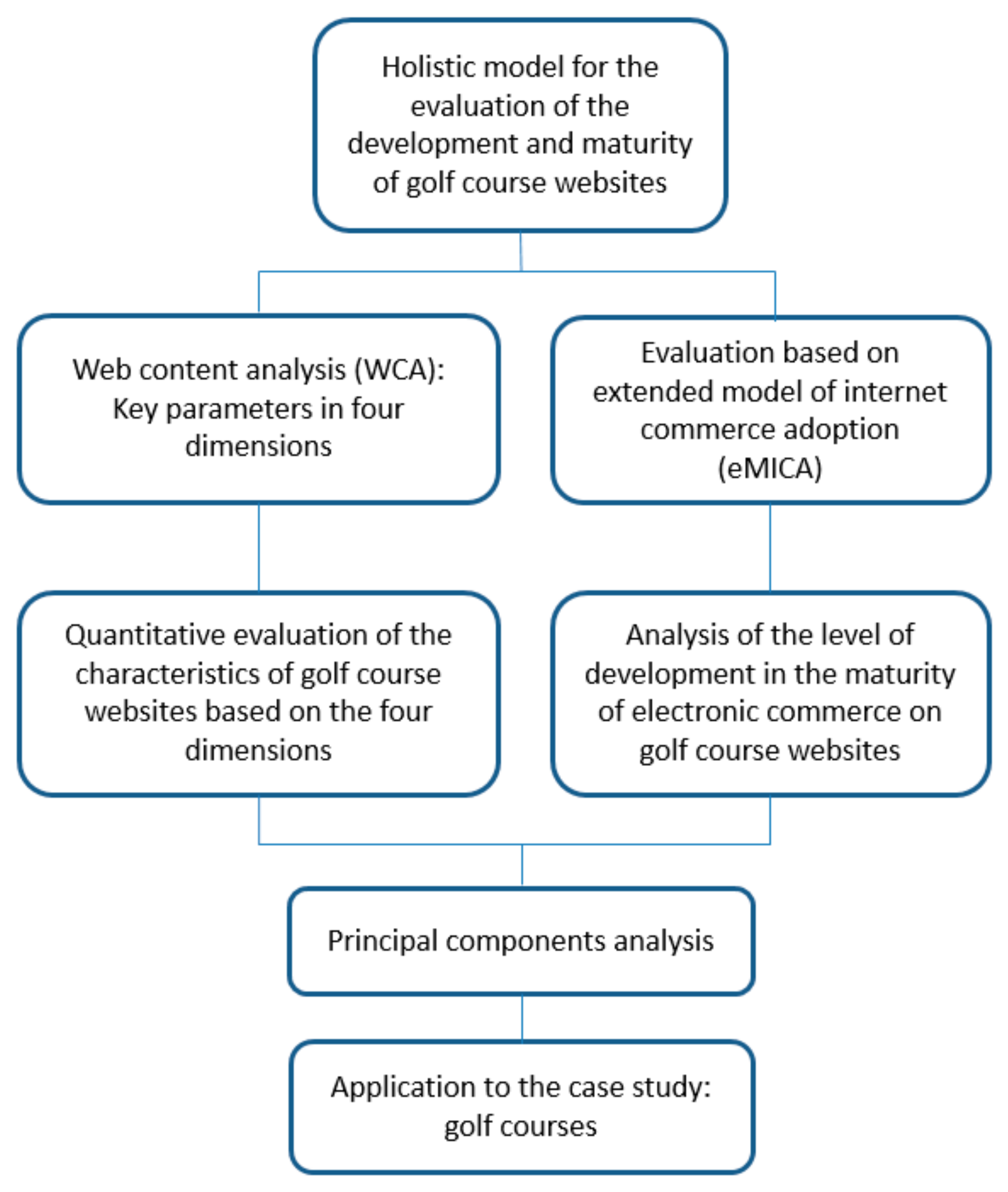

3.3. Integration of the eMICA and WCA

4. Results

4.1. Results of the WCA

4.1.1. Information

4.1.2. Communication

4.1.3. E-Commerce

4.1.4. Additional Functions

4.2. Results of the eMICA

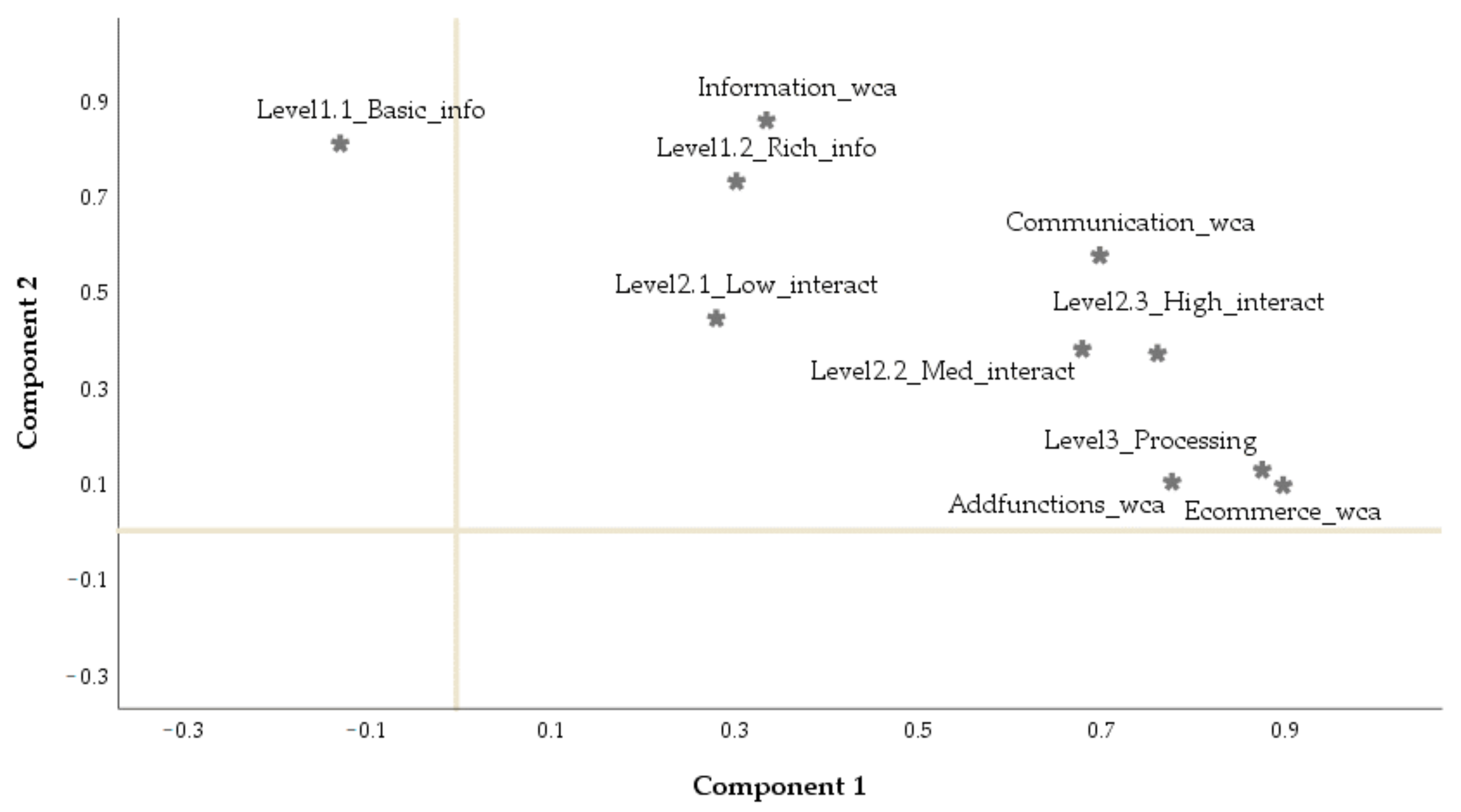

4.3. Results of the PCA

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Laudon, K.C.; Traver, C.G. E-Commerce: Business, Technology, Society; Pearson: Harlow, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Alam, S.S.; Nor, N.G.M.; Ali, M.H.; Omar, N.A.; Wel, C.A.C. Relationship between entrepreneur’s traits and cloud computing adoption among malay-owned SMEs in Malaysia. Cuad. Gest. 2018, 18, 115–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calvo-Porral, C.; Nieto-Mengotti, M. The moderating influence of involvement with ICTs in mobile services. Span. J. Mark. ESIC 2019, 23, 25–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eze, S.C.; Chinedu-Eze, V.C.; Bello, A.O. Determinants of dynamic process of emerging ICT adoption in SMEs–actor network theory perspective. J. Sci. Technol. Policy Manag. 2019, 10, 2–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kijek, T.; Kijek, A. Is innovation the key to solving the productivity paradox? J. Innov. Knowl. 2019, 4, 219–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dangi, M.R.M.; Ismail, A.H.; Johari, R.J.; Noor, R.M. SME’s Internationalization Initiatives: Business & Growth Strategy ICT and Technology. Int. J. Account. Financ. Bus. 2018, 3, 63–75. [Google Scholar]

- Fink, C.; Mattoo, A.; Neagu, I.C. Assessing the impact of communication costs on international trade. J. Int. Econ. 2005, 67, 428–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biagi, F.; Falk, M. The impact of ICT and e-commerce on employment in Europe. J. Policy Model. 2017, 39, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikalef, P.; Pateli, A. Information technology-enabled dynamic capabilities and their indirect effect on competitive performance: Findings from PLS-SEM and fsQCA. J. Bus. Res. 2017, 70, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piccoli, G.; Lui, T.-W. The competitive impact of information technology: Can commodity IT contribute to competitive performance. Eur. J. Inf. Syst. 2014, 23, 616–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofacker, C.F.; Belanche, D. Eight social media challenges for marketing managers. Span. J. Mark. ESIC 2016, 20, 73–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burstein, A.; Vogel, J. International trade, technology, and the skill premium. J. Polit. Econ. 2017, 125, 1356–1412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ming, D.; Xiao, C.; Han, J. Effect of Interaction between Exporter’s Technology Level and Importer’s Protection of IPR on Exporter’s Trade: Evidences from China’s Foreign Trade. Technol. Econ. 2017, 5, 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Cristobal-Fransi, E.; Martín, E.; Daries, N. Behavioral Analysis of Subjects Interacting with Information Technology: Categorizing the behavior of e-consumers. Int. J. Serv. Technol. Manag. 2015, 21, 163–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FRONTUR-INE. Estadística de Movimientos Turísticos en Frontera [Tourist Movement on Borders]. Available online: https://www.ine.es/ (accessed on 15 June 2020). (In Spanish).

- EGATUR-INE. Encuesta de Gasto Turístico [Tourism Spending Survey]. Available online: https://www.ine.es/ (accessed on 11 September 2020). (In Spanish).

- World Travel and Tourism Council. Economic Impact of Tourism. Available online: https://www.wttc.org/economic-impact/ (accessed on 11 September 2020).

- Aymerich, F.; Anabitarte, J.; Golf Business Partners. El Impacto Económico del Golf en España [The Economic Impact of Golf in Spain]. Available online: https://www.rfegolf.es/CompetenciaPaginas/NewsDetails.aspx?NewsId=7012 (accessed on 11 September 2020). (In Spanish).

- IAGTO (International Association of Golfing Tour Operators). Global Golf Tourism Market. Available online: https://www.iagto.com/pressrelease/index (accessed on 11 September 2020).

- Sheets, B.H.; Roach-Humphreys, J.; Johnston, T. Turnaround Strategy: Overview of the Business and Marketing Challenges Facing the Golf Industry and Initiatives to Reinvigorate the Game. Bus. Educ. Innov. J. 2016, 8, 161–171. [Google Scholar]

- Ciurana, J.T.P.; Del Campo-Gomis, F.J.; Gimenez, F.V.; Campos, D.P.; Torres, A.A. Analysis of the efficiency of golf tourism via the Internet. Application to the Mediterranean countries. Curr. Issues Tour. 2015, 18, 595–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Bonilla, L.M.; Reyes-Rodríguez, M.D.C.; López-Bonilla, J.M. Golf tourism and sustainability: Content analysis and directions for future research. Sustainability 2020, 12, 3616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enz, C.A.; Canina, L. Competitive pricing in the golf industry. J. Revenue Pricing Manag. 2017, 16, 139–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madrigal, M.A.; Lara, J.A.S. Golf tourism in southern Europe: A potential market. Stud. Appl. Econ. 2019, 37, 64–79. [Google Scholar]

- Sweeney, K. Golf Business and Management: A Global Introduction. J. Sport Manag. 2018, 32, 316–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hudson, S.; Hudson, L. Golf Tourism; Goodfellow Publishing: Oxford, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Song, H.M.; Kim, K.S.; Yim, B.H. The mediating effect of place attachment on the relationship between golf tourism destination image and revisit intention. Asia Pac. J. Tour. Res. 2017, 22, 1182–1193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butler, R.W. Contributions of tourism to destination sustainability: Golf tourism in St Andrews, Scotland. Tour. Rev. 2019, 74, 235–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.J.; Kyle, G.T.; Scott, D. The mediating effect of place attachment on the relationship between festival satisfaction and loyalty to the festival hosting destination. J. Travel Res. 2012, 51, 754–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, Y.; Uysal, M. An examination of the effects of motivation and satisfaction on destination loyalty: A structural model. Tour. Manag. 2005, 26, 45–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geissler, G.L. An examination of the Golf vacation package-purchase decision: A case study in the US Gulf Coast region. J. Hosp. Leis. Mark. 2005, 13, 65–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hutchinson, J.; Wang, Y.; Lai, F. The impact of satisfaction judgment on behavioral intentions: An investigation of golf travelers. J. Vacat. Mark. 2010, 16, 45–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hennessey, S.M.; Macdonald, R.; MacEachern, M. A framework for understanding golfing visitors to a destination. J. Sport Tour. 2008, 13, 5–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.; Morrison, A.M.; Wu, B.; Kong, Y. Korean Golf Tourism in China: Place, Perception and Narratives. Sustainability 2018, 10, 1055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrick, J.F. Are loyal visitors desired visitors? Tour. Manag. 2004, 25, 463–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tassiopoulos, D.; Haydam, N. Golf tourists in South Africa: A demand-side study of a niche market in sports tourism. Tour. Manag. 2008, 29, 870–882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Humphreys, C. Understanding how sporting characteristics and behaviours influence destination selection: A grounded theory study of golf tourism. J. Sport Tour. 2014, 19, 29–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stebbins, R.A. Leisure as not work: A (far too) common definition in theory and research on free-time activities. World Leis. J. 2018, 60, 255–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.H.; Ritchie, B.W. Motivation-based typology: An empirical study of golf tourists. J. Hosp. Tour. Res. 2012, 36, 251–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibson, H.J.; Pennington-Gray, L. Insights from role theory: Understanding golf tourism. Eur. Sport Manag. Q. 2005, 5, 443–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higham, J.; Hinch, T. Sport Tourism Development, 3rd ed.; Channel View Publications: Bristol, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Powers, R.L.; Tabibzadeh, K. An Exploratory Study of Web Use by the Golf Course Industry. Int. J. Acad. Bus. World 2010, 4, 29–32. [Google Scholar]

- Afonso Dias, J.; Martínez-López, F.J. The use of the internet in golf course promotion: A comparative analysis of the golf course web pages of the Algarve, Andalusia and Florida. Rev. Tur. Desenvolv. 2011, 16, 73–84. [Google Scholar]

- García-Tascón, M.; Pradas-García, M. Does the transparency of the websites can help in attracting customers? Analysis of the golf courses in Andalusia. Intang. Cap. 2016, 12, 805–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brooksbank, R.; Garland, R.; Werder, W. Strategic marketing practices as drivers of successful business performance in British, Australian and New Zealand golf clubs. Eur. Sport Manag. Q. 2012, 12, 457–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garland, R.; Brooksbank, R.; Werder, W. Strategic marketing’s contribution to Australasian golf club performance. Sport Bus. Manag. Int. J. 2011, 1, 138–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, R.; Correia, A.; Schutz, R.L. Destination brand personality: Searching for personality traits on golf-related websites. Anatolia Int. J. Tour. Hosp. Res. 2014, 25, 387–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roigb, E.M.-; Rosellb, B.F.-; Daries, N.; Cristóbal-Fransi, E. Measuring Gastronomic Image Online. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 4631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdallah, S.; Jaleel, B. Website appeal: Development of an assessment tool and evaluation framework of e-marketing. J. Theor. Appl. Electron. Commer. Res. 2015, 10, 45–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camprubí, R.; Coromina, L. Content analysis in tourism research. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2016, 18, 134–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herring, S.C. Web content analysis: Expanding the paradigm. In International Handbook of Internet Research; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2009; pp. 233–249. [Google Scholar]

- Law, R. Evaluation of hotel websites: Progress and future developments. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2019, 76, 2–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benbunan-Fich, R. Using protocol analysis to evaluate the usability of a commercial web site. Inf. Manag. 2001, 39, 151–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiou, W.-C.; Lin, C.-C.; Perng, C. A strategic framework for website evaluation based on a review of the literature from 1995–2006. Inf. Manag. 2010, 47, 282–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cristobal-Fransi, E.; Daries-Ramon, N.; Mariné-Roig, E.; Martin-Fuentes, E. Implementation of Web 2.0 in the snow tourism industry: Analysis of the online presence and e-commerce of ski resorts. Span. J. Mark. ESIC 2017, 21, 117–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Álvarez Díaz, Y. La Orientación al Mercado en el Sector Turístico Con el Uso de las Herramientas de la Web Social, Efectos en Los Resultados Empresariales [Market Orientation in the Tourism Sector with Social Web Tools, Effects on Business Results]. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Cantabria, Santander, Spain, 2014. Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/10902/5018 (accessed on 28 September 2020).

- Cristobal-Fransi, E.; Montegut-Salla, Y.; Ferrer-Rosell, B.; Daries, N. Rural cooperatives in the digital age: An analysis of the Internet presence and degree of maturity of agri-food cooperatives’e-commerce. J. Rural Stud. 2020, 74, 55–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daries, N.; Cristobal-Fransi, E.; Ferrer-Rosell, B.; Marine-Roig, E. Maturity and development of high-quality restaurant websites: A comparison of Michelin-starred restaurants in France, Italy and Spain. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2018, 73, 125–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, M.; Gray, D. Exploring the information source preferences among Canadian adult golf league members. J. Amat. Sport 2016, 2, 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Hasley, J.P.; Gregg, D.G. An exploratory study of website information content. J. Theor. Appl. Electron. Commer. Res. 2010, 5, 27–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.K.; Morrison, A.M. A comparative study of web site performance. J. Hosp. Tour. Technol. 2010, 1, 50–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, H.; Widdows, R.; Hooker, N.H. Web content analysis of e-grocery retailers: A longitudinal study. Int. J. Retail. Distrib. Manag. 2009, 37, 839–851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wanless, E.A.; Petersen, J.C.; Pursglove, L.K.; Desmond, L.; Judge, L.W. Accessible Golf Courses: Web-based Accommodation Communication. Phys. Educ. 2018, 75, 816–834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neuendorf, K.A. The Content Analysis Guide Book; Sage Publications: London, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Burgess, L.; Cooper, J. The Status of Internet Commerce in the Manufacturing Industry in Australia: A survey of Metal Fabrication Industries. In Proceedings of the Second CollECTeR Conference on Electronic Commerce, Sydney, NSW, Australia, 10 October 1998; pp. 65–73. [Google Scholar]

- Burgess, L.; Sargent, J.P.; Cooper, J.; Cerpa, N. A comparative analysis of the use of the Web for destination marketing by regional tourism organisations in Chile and the Asia Pacific. In Collaborative Electronic Commerce Technology and Research; Universidad de Talca: Talca, Chile, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Burgess, S. Representing small business web presence content: The web presence pyramid model. Eur. J. Inf. Syst. 2016, 25, 110–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burgess, L.; Parish, B.; Alcock, C. To what extent are regional tourism organisations (RTOs) in Australia leveraging the benefits of web technology for destination marketing and eCommerce? Electron. Commer. Res. 2011, 11, 341–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daries, N.; Cristobal-Fransi, E.; Mariné-Roi, E. Deployment of restaurants websites’ marketing features: The case of Spanish Michelin-starred restaurants. Int. J. Hosp. Tour. Adm. 2019, 20, 249–280. [Google Scholar]

- Doolin, B.; Burgess, L.; Cooper, J. Evaluating the use of the Web for tourism marketing: A case study from New Zealand. Tour. Manag. 2002, 23, 557–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, D.; Zhou, Z.; Guo, X. A study of the website performance of travel agencies based on the EMICA model. J. Serv. Sci. Manag. 2009, 3, 181–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ting, P.H.; Wang, S.T.; Bau, D.Y.; Chiang, M.L. Website evaluation of the top 100 hotels using advanced content analysis and eMICA model. Cornell Hosp. Q. 2013, 54, 284–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cristobal-Fransi, E.; Daries, N.; Serra-Cantallops, A.; Ramón-Cardona, J.; Zorzano, M. Ski Tourism and Web Marketing Strategies: The Case of Ski Resorts in France and Spain. Sustainability 2018, 10, 2920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daries, N.; Cristóbal Fransi, E.; Martín Fuentes, E.; Mariné Roig, E. E-commerce adoption in mountain and snow tourism: Analysis of ski resort web presence through the EMICA model. Cuad. Tur. 2016, 37, 483–487. [Google Scholar]

- Girginov, V.; Taks, V.M.; Boucher, B.; Martyn, S.; Holman, M.; Dixon, J. Canadian national sport organizations’ use of the web for relationship marketing in promoting sport participation. Int. J. Sport Commun. 2009, 2, 164–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Schmidt, S.; Serra Cantallops, A.; Dos Santos, C.P. The characteristics of hotel websites and their implications for website effectiveness. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2008, 27, 504–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marimon, F.; Vidgen, R.; Barnes, S.J.; Cristóbal-Fransi, E. Purchasing behaviour in an online supermarket: The applicability of E-S-QUAL. Int. J. Mark. Res. 2010, 52, 111–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ratten, V. Sport innovation management: Towards a research agenda. Innovation 2016, 18, 238–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breitbarth, T.; Kaiser-Jovy, S.; Dickson, G. Global golf business and management. In Golf Business and Management; Routledge: London, UK, 2017; pp. 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, J.H.; Kim, M.; Lennon, S.J. E-Service Performance of Apparel E-Retailing Websites: A Longitudinal Assessment. Int. J. Serv. Sci. Manag. Eng. Technol. 2018, 9, 24–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.; Anderson, R.E.; Black, W.; Tatham, R.L. Multivariate Data Analysis: A Global Perspective, 7th ed.; Prentice-Hall: London, UK; Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Anwar, A.; Waqas, A.; Zain, H.M.; Kee, D.M.H. Impact of Music and Colour on Customers’ Emotional States: An Experimental Study of Online Store. Asian J. Bus. Res. 2020, 10, 104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ijaz, M.F.; Rhee, J. Constituents and Consequences of Online-Shopping in Sustainable E-Business: An Experimental Study of Online-Shopping Malls. Sustainability 2018, 10, 3756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nilashi, M.; Ibrahim, O.; Yadegaridehkordi, E.; Samad, S.; Akbari, E.; Alizadeh, A. Travelers decision making using online review in social network sites (2018), A case on TripAdvisor. J. Comput. Sci. 2018, 8, 168–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, S.; Sousa, B. Exploratory study of consumer behavior and profile in specific tourism contexts: Golf tourism in Northern Portugal. Tour. Hosp. Int. J. 2019, 12, 13–31. [Google Scholar]

| Information Variable | 1. Basic golf course information |

| I.1.1- Golf course description (address, membership information, origin, history, etc.). | |

| I.1.2- Contacts: telephone, fax numbers and email address. | |

| I.1.3- Images of the golf course. | |

| I.1.4- Visual and textual information about services on offer. | |

| I.1.5- News/events communications. | |

| I.1.6- Golf course location information. | |

| I.1.7- Links to assessment websites of services provided by the golf course. | |

| I.1.8- Virtual tour. | |

| I.1.9- Golf course opening hours. | |

| I.1.10- Information about the federation tournament schedule for the specific golf course. | |

| 2. Golf course facilities | |

| I.2.1- Plan of the golf course. | |

| I.2.2- Booking of rounds of golf on the official website. | |

| I.2.3- Price information. | |

| I.2.4- Golf lesson information; lessons for adults/children. | |

| 3. Local environment of the golf course | |

| I.3.1- Tourist information about the area. | |

| I.3.2- Weather reports. | |

| I.3.3- Information about access to the golf course (airports, trains, motorways, etc.). | |

| 4. Promotions | |

| I.4.1- Event promotions, advertising campaigns, news, banners, fairs, promotional calendar and events on the golf course. | |

| I.4.2- Incentives: vouchers/coupons, exclusive internet offers, online contests, promotion of different services. | |

| Communication Variable | 1. Interaction with clients. |

| C.1.1- Golf course email addresses and telephone number. | |

| C.1.2- Facility for clients to post comments online. | |

| C.1.3- Instant messaging. | |

| C.1.4- Online surveys. | |

| C.1.5- Frequently asked questions section. | |

| C.1.6- Option to receive course newsletter (information bulletin). | |

| C.1.7- Restricted access zone for clients and members. | |

| C.1.8- Facility for clients to vote on the quality of, and satisfaction with, services provided. | |

| 2. Web 2.0. resources | |

| C.2.1- Content syndication (RSS)/Podcasting. | |

| C.2.2- Applications that allow users to publish content. | |

| C.2.3- Facility that allows users to share content with their contacts. | |

| C.2.4- Link to company blog. | |

| C.2.5- Links to external image and video platforms. | |

| C.2.6- Links to company social networks. | |

| C.2.7- Content syndication (RSS)/Podcasting. | |

| C.2.8- Applications that allow users to publish content. | |

| 3. Foreign language facility | |

| C.3.1- Website available in more than one language. | |

| Electronic Commerce Variable | EC.1- Online payment. |

| EC.2- Secure online transactions (in purchase processes, digital signatures, encryption, security code via mobile text). | |

| EC.3- Interaction with the server: database consultation (customer access to their profiles, with the possibility of making modifications, access to purchase history, etc.) | |

| Additional Functions Variable | 1. Information security. |

| AF 1.1. Privacy policy and legal notice | |

| AF 1.2. Data protection laws | |

| AF 1.3. Website security | |

| 2. Certifications. | |

| AF 2.1- Golf Environment Organisation (GEO) certification. A seal granted by the Golf Environment Organisation | |

| AF 2.2- Environmental Management Systems (EMS) help to identify, prioritise and manage environmental risks. | |

| AF 2.3- Environmental certification (ISO 14000). Environmental policy established by the Directorate of the National Golf Centre | |

| AF 2.4- Other certifications. | |

| 3. Mobile version. | |

| AF 3.1- Possession of an internet link to the mobile version of the website. | |

| AF 3.2- Availability of official golf course app. |

| Phase 1: Promotion (Information) | Level 1: Basic Information (Minimum of 3 of the 5 Proposed Variables) |

|---|---|

| Contact details: Golf course name, address, telephone and fax numbers, and others | |

| Opening days and hours | |

| Plan of the golf course | |

| Photographs of the golf course | |

| Location information | |

| Level 2: Rich information (minimum of 4 of the 7 proposed variables) | |

| Email and/or contact form | |

| Information on services offered (caddies, golf buggies, golf carts, golf club hire, etc.) | |

| Weather forecasts | |

| Website available in more than one language | |

| Quality awards and certifications | |

| News/events information | |

| Internet-based promotions and incentives (vouchers/coupons, exclusive internet offers, online contests) | |

| Phase 2: Provision (Dynamic Information) | Level 1: Low level of interactivity (minimum of 4 of the 9 proposed variables) |

| Rates and members’ season ticket prices | |

| Interactive golf course map | |

| Basic prices and information | |

| Links to external information: accommodation, restaurants, others | |

| Playing tips (clothing, techniques, etc.) | |

| Complete competition calendar | |

| Lessons | |

| Online survey of services offered | |

| Links to related pages | |

| Level 2: Medium level of interactivity (minimum of 4 of the 9 proposed variables) | |

| Website map | |

| Webcam | |

| Reservation facility | |

| Facility to download brochures and photographs | |

| Email bulletins (newsletter) | |

| Privacy policy and legal notice | |

| Frequently asked questions (FAQs) | |

| Suggestions | |

| Online shop | |

| Level 3: High level of interactivity (minimum of 4 of the 9 proposed variables) | |

| Exclusive client/member zone | |

| Multimedia applications | |

| Blogs, forums and chats | |

| Access to profiles in golf course social networks | |

| Facility for clients to post comments online | |

| Facility to evaluate satisfaction with services offered | |

| Virtual tour of the golf courses | |

| Mobile version of the website | |

| Facility to download the mobile app | |

| Phase 3: Processing (Functional Maturity) | Secure online transactions, (in purchase processes, digital signatures, encryption, security code via mobile text) (secure forms of payment using credit/debit cards or PayPal) |

| Interaction with the server: database consultation (access to customer profiles with the possibility of modification, access to purchase history, etc.). Private registration area |

| Information | 18 Holes | 9 Holes | Total | V.C. and Sig. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Golf course information | ||||

| I.1.1- Description of the golf course | 100 | 100 | 100 | - |

| I.1.2- Contacts: telephone and fax numbers, email address | 100 | 100 | 100 | - |

| I.1.3- Images of the golf course | 100 | 100 | 100 | - |

| I.1.4- Text and visual information about services offered | 96.3 | 100 | 97.3 | 0.101 |

| I.1.5- News/events communications | 88.9 | 70.0 | 83.8 | 0.228 |

| I.1.6- Information on the location of golf courses | 100 | 100 | 100 | - |

| I.1.7- Links to assessment websites of services provided by the golf course | 18.5 | 0.0 | 13.5 | 0.241 |

| I.1.8. Virtual tours | 7.4 | 0.0 | 5.4 | 0.145 |

| I.1.9. Golf course opening hours | 48.1 | 60.0 | 51.4 | 0.105 |

| I.1.10- Information on the golf course’s federation tournament calendar | 96.3 | 90.0 | 94.6 | 0.124 |

| 2. Golf course facilities | ||||

| I.2.1- Golf course plans | 96.3 | 80.0 | 91.9 | 0.251 |

| I.2.2- Facility to book rounds of golf | 81.5 | 50.0 | 73.0 | 0.315 * |

| I.2.3- Price information | 96.3 | 20.0 | 75.7 | 0.790 ** |

| I.2.4- Golf lesson information: courses for adults/children | 100 | 100 | 100 | - |

| 3. Golf course surroundings | ||||

| I.3.1- Local area tourism information | 40.7 | 20.0 | 35.1 | 0.193 |

| I.3.2- Weather forecasts | 40.7 | 30.0 | 37.8 | 0.098 |

| I.3.3- Access routes to the golf course | 81.5 | 60.0 | 75.7 | 0.222 |

| 4. Promotions | ||||

| I.4.1- Event promotions, public campaigns, news, banners, fairs, calendar of golf course promotions and events | 77.8 | 70.0 | 75.7 | 0.080 |

| I.4.2- Incentives: vouchers/coupons, exclusive internet offers, online courses, promotion of different services | 88.9 | 70.0 | 83.8 | 0.228 |

| Communication | 18 Holes | 9 Holes | Total | V.C. and Sig. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Client interaction | ||||

| C.1.1- Golf course email address and telephone number | 100 | 100 | 100 | - |

| C.1.2- Facility for clients to post comments online | 81.5 | 10.0 | 62.2 | 0.655 ** |

| C.1.3- Instant messaging | 81.5 | 0.0 | 59.5 | 0.737 ** |

| C.1.4- Online surveys | 0 | 0 | 0 | - |

| C.1.5- Frequently asked questions area | 22.2 | 0 | 16.2 | 0.268 |

| C.1.6- Information bulletin | 66.7 | 50.0 | 62.2 | 0.153 |

| C.1.7- Private client/member zone | 22.2 | 0 | 16.2 | 0.268 |

| C.1.8- Facility for clients to vote on the quality of, and satisfaction with, services provided | 0 | 0 | 0 | - |

| 2. Website resources | ||||

| C.2.1- Content syndication (RSS)/Podcasting | 29.6 | 20.0 | 27.0 | 0.096 |

| C.2.2- Applications that allow users to publish content | 0 | 0 | 0 | - |

| C.2.3- Facility to share content with friends and contacts | 0 | 10.0 | 2.70 | 0.274 ^ |

| C.2.4- Link to company blog | 11.1 | 10.0 | 10.8 | 0.016 |

| C.2.5- Links to external image and video platforms | 33.3 | 0 | 24.3 | 0.345 * |

| C.2.6- Links to company social networks | 74.1 | 30.0 | 62.2 | 0.404 * |

| 3. Language capabilities | ||||

| C.3. Website available in more than one language | 81.5 | 50.0 | 73.0 | 0.315 ^ |

| Electronic Commerce | 18 Holes | 9 Holes | Total | V.C. and Sig. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| EC.1- Online payment | 70.4 | 0.0 | 51.4 | 0.625 ** |

| EC.2- Secure online transactions (in purchase processes, digital signature, encryption, security code via mobile text) | 70.4 | 0.0 | 51.4 | 0.625 ** |

| EC.3- Interaction with the server: database consultation (access to client profile with the facility to modify, access to purchase history, etc.) | 70.4 | 0.0 | 51.4 | 0.625 ** |

| Additional Functions | 18 Holes | 9 Holes | Total | V.C. and Sig. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Information safety | ||||

| AF 1.1- Privacy policy and legal notice | 74.1 | 50.0 | 67.6 | 0.228 |

| AF 1.2- Data protection laws | 66.7 | 30.0 | 56.8 | 0.329 * |

| AF 1.3- Secure website | 44.4 | 30.0 | 40.5 | 0.131 |

| 2. Certifications. | ||||

| AF 2.1- Golf Environment Organization (GEO) certificate | 7.4 | 0 | 5.4 | 0.145 |

| AF 2.2- Environment management systems (EMS) | 0 | 0 | 0 | - |

| AF 2.3- Environmental certifications (ISO 14000) | 3.7 | 0 | 2.7 | 0.101 |

| AF 2.4- Other certifications | 0 | 0 | 0 | - |

| 3. Mobile versions. | ||||

| AF 3.1- Link to the mobile version of the website | 100 | 10.0 | 75.7 | 0.932 ** |

| AF 3.2- Official golf course app | 11.1 | 10.0 | 10.8 | 0.016 |

| 18 Holes | 9 Holes | Total | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Promotion (information) | ||||||

| Level 1 Basic information | 27 | 100% | 10 | 100% | 37 | 100% |

| Level 2 Rich information | 18 | 66.7% | 4 | 40% | 22 | 55% |

| Provision (dynamic information) | ||||||

| Level 1 Low level of interactivity | 16 | 59.2% | 4 | 40% | 20 | 50% |

| Level 2 Medium level of interactivity | 14 | 51.8% | 2 | 20% | 16 | 40% |

| Level 3 High level of interactivity | 4 | 14.8% | 0 | 0% | 4 | 10% |

| Processing (functional maturity) | 4 | 14.8% | 0 | 0% | 4 | 10% |

| WCA Dimensions | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Achievement of eMICA Phases | Type | Freq. | Info. 19 Items | Eta and Sig. | Com. 15 Items | Eta and Sig. | e-com. 3 Items | Eta and Sig. | AddF 9 Items | Eta and Sig. | WCA 46 Items | Eta and Sig. | |

| Phase 1 | No | 18 | 9 | 13.2 | 0.606 ** | 5.1 | 0.469 ** | 1.7 | 0.298 ^ | 2.9 | 22.9 | 0.535 ** | |

| 9 | 6 | 10.8 | 2.2 | 0.0 | 1.0 | 14.0 | |||||||

| Yes (22) | 18 | 18 | 15.3 | 6.5 | 2.3 | 3.1 | 27.3 | ||||||

| 9 | 4 | 14.3 | 3.4 | 0.0 | 1.2 | 19.8 | |||||||

| Phase 2 | No | 18 | 21 | 14.4 | 5.6 | 0.510 ** | 1.9 | 0.428 ** | 2.7 | 0.489 ** | 24.7 | 0.487 ** | |

| 9 | 10 | 12.2 | 2.8 | 0.0 | 1.3 | 16.3 | |||||||

| Yes (6) | 18 | 6 | 15.2 | 7.7 | 3.0 | 4.2 | 30.0 | ||||||

| 9 | - | - | - | - | - | - | |||||||

| Phase 3 | No | 18 | 8 | 13.9 | 0.452 ** | 5.0 | 0.596 *** | 0.0 | 0.947 ** | 2.3 | 0.563 ** | 21.1 | 0.764 ** |

| 9 | 9 | 11.9 | 2.7 | 0.0 | 1.1 | 15.7 | |||||||

| Yes (20) | 18 | 19 | 14.9 | 6.5 | 3.0 | 3.3 | 27.8 | ||||||

| 9 | 1 | 15 | 4.0 | 0.0 | 3 | 22.0 | |||||||

| All courses | 18 | 27 | 14.6 | 0.464 ** | 6.1 | 0.665 ** | 2.1 | 0.626 ** | 3.0 | 0.516 ** | 25.9 | 0.698 ** | |

| 9 | 10 | 12.2 | 2.8 | 0 | 1.3 | 16.3 | |||||||

| Component 1: E-Commerce and Processing | Component 2: Information and Low Interaction | |

|---|---|---|

| Information WCA | 0.335 | 0.858 |

| Communication WCA | 0.698 | 0.575 |

| E-commerce WCA | 0.899 | 0.094 |

| Additional functions WCA | 0.777 | 0.102 |

| Level 1.1 Basic information | −0.130 | 0.809 |

| Level 1.2 Rich information | 0.302 | 0.730 |

| Level 2.1 Low interaction | 0.280 | 0.444 |

| Level 2.2 Medium interaction | 0.679 | 0.379 |

| Level 2.3 High interaction | 0.761 | 0.370 |

| Level 3 Processing | 0.876 | 0.127 |

| Source: Own design |

| E-commerce and Processing | Information and Low Interaction | Integrated Model | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 18 Holes | 15.48 | 21.76 | 336.69 |

| 9 Holes | 5.73 | 18.34 | 105.01 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Daries, N.; Cristobal-Fransi, E.; Ferrer-Rosell, B. Implementation of Website Marketing Strategies in Sports Tourism: Analysis of the Online Presence and E-Commerce of Golf Courses. J. Theor. Appl. Electron. Commer. Res. 2021, 16, 542-561. https://doi.org/10.3390/jtaer16030033

Daries N, Cristobal-Fransi E, Ferrer-Rosell B. Implementation of Website Marketing Strategies in Sports Tourism: Analysis of the Online Presence and E-Commerce of Golf Courses. Journal of Theoretical and Applied Electronic Commerce Research. 2021; 16(3):542-561. https://doi.org/10.3390/jtaer16030033

Chicago/Turabian StyleDaries, Natalia, Eduard Cristobal-Fransi, and Berta Ferrer-Rosell. 2021. "Implementation of Website Marketing Strategies in Sports Tourism: Analysis of the Online Presence and E-Commerce of Golf Courses" Journal of Theoretical and Applied Electronic Commerce Research 16, no. 3: 542-561. https://doi.org/10.3390/jtaer16030033

APA StyleDaries, N., Cristobal-Fransi, E., & Ferrer-Rosell, B. (2021). Implementation of Website Marketing Strategies in Sports Tourism: Analysis of the Online Presence and E-Commerce of Golf Courses. Journal of Theoretical and Applied Electronic Commerce Research, 16(3), 542-561. https://doi.org/10.3390/jtaer16030033