Distribution Contract Analysis on e-Platform by Considering Channel Role and Good Complementarity

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. E-Platforms

2.2. Complementary Goods

3. Models and Analytic Results

3.1. The WWS1 Model

3.2. The WAS1 Model

3.3. The AWS1 Model

3.4. The AAS1 Model

4. Comparison and Analysis of Results

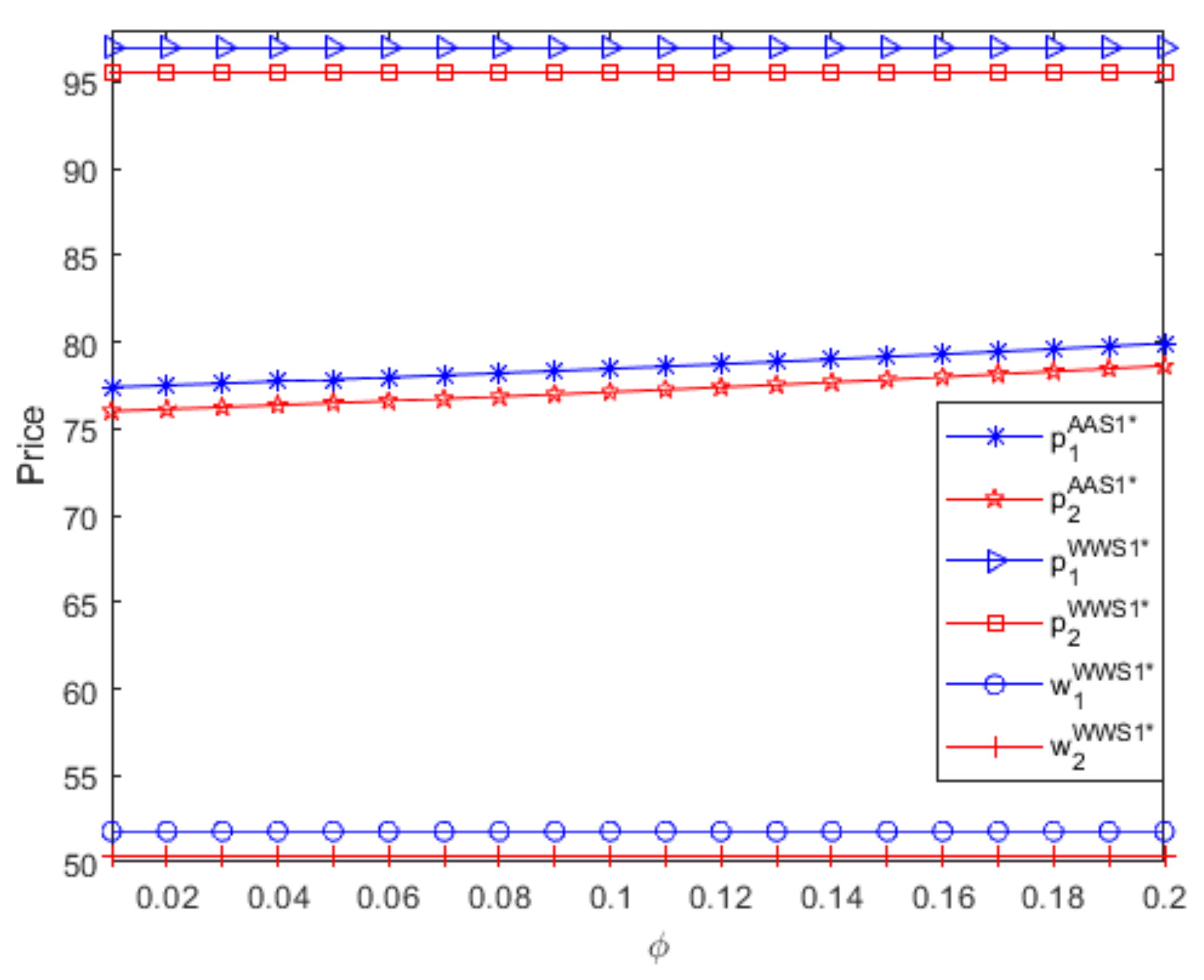

4.1. Impact of the e-Retailer’s Referral Fees

- (1.1)

- If two suppliers use the same distribution contract to sell complementary goods with symmetric parameters, although the optimal retail/wholesale price of powerful supplier is remarkably larger than that of small supplier, there is no obvious difference between two suppliers’ profits. Thus, if two suppliers use the same distribution contract to sell complementary goods with symmetric parameters, although the leader role makes the supplier charge an obviously greater optimal retail/wholesale price, the leader role cannot make the supplier obtain obviously larger profits regardless of the referral fees; moreover, as the referral fees increase, the leader role’s advantage almost disappears when two suppliers both use an A contract.

- (1.2)

- If two suppliers use the same distribution contract to sell complementary goods with symmetric parameters, although these goods have higher optimal retail prices when both suppliers use a W contract than when both suppliers use an A contract, two suppliers obtain more profits when they both use an A contract than when they both use a W contract, which is independent of the referral fees. Moreover, if two suppliers both use an A contract, as the referral fees increase, two goods’ optimal retail prices increase slowly, but two suppliers’ profits decrease quickly. If two suppliers use different distribution contracts to sell complementary goods with symmetric parameters, the optimal retail price charged in a W contract is larger than that charged in an A contract, and the supplier obtains more profits when it uses an A contract than when it uses a W contract, which is independent of its channel role and the referral fees. Thus, if two suppliers use the same or different distribution contracts to sell complementary goods with symmetric parameters, the optimal retail price charged by the e-retailer is greater than that charged by the supplier, and the A contract is more beneficial to the supplier than the W contract, which is independent of the referral fees.

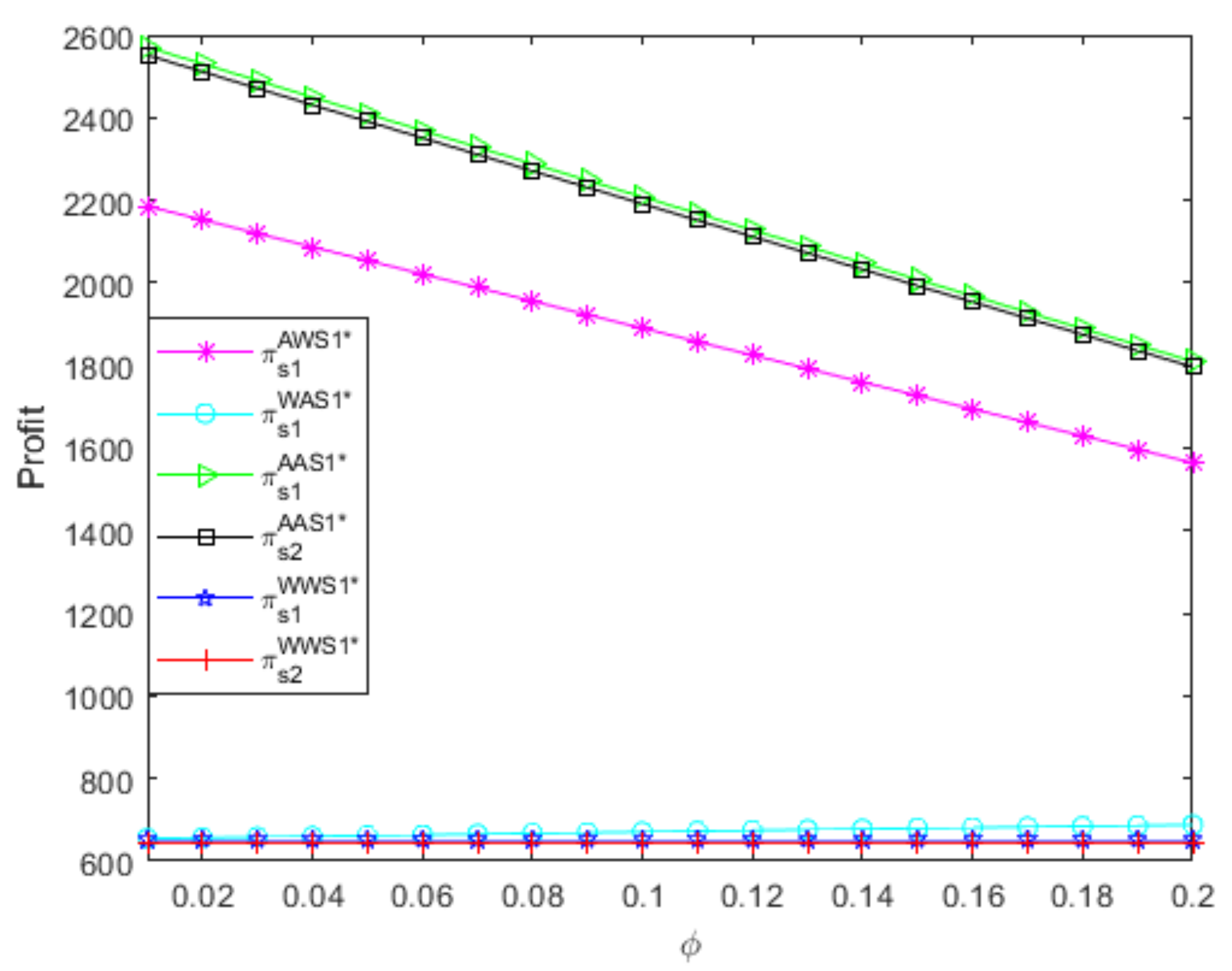

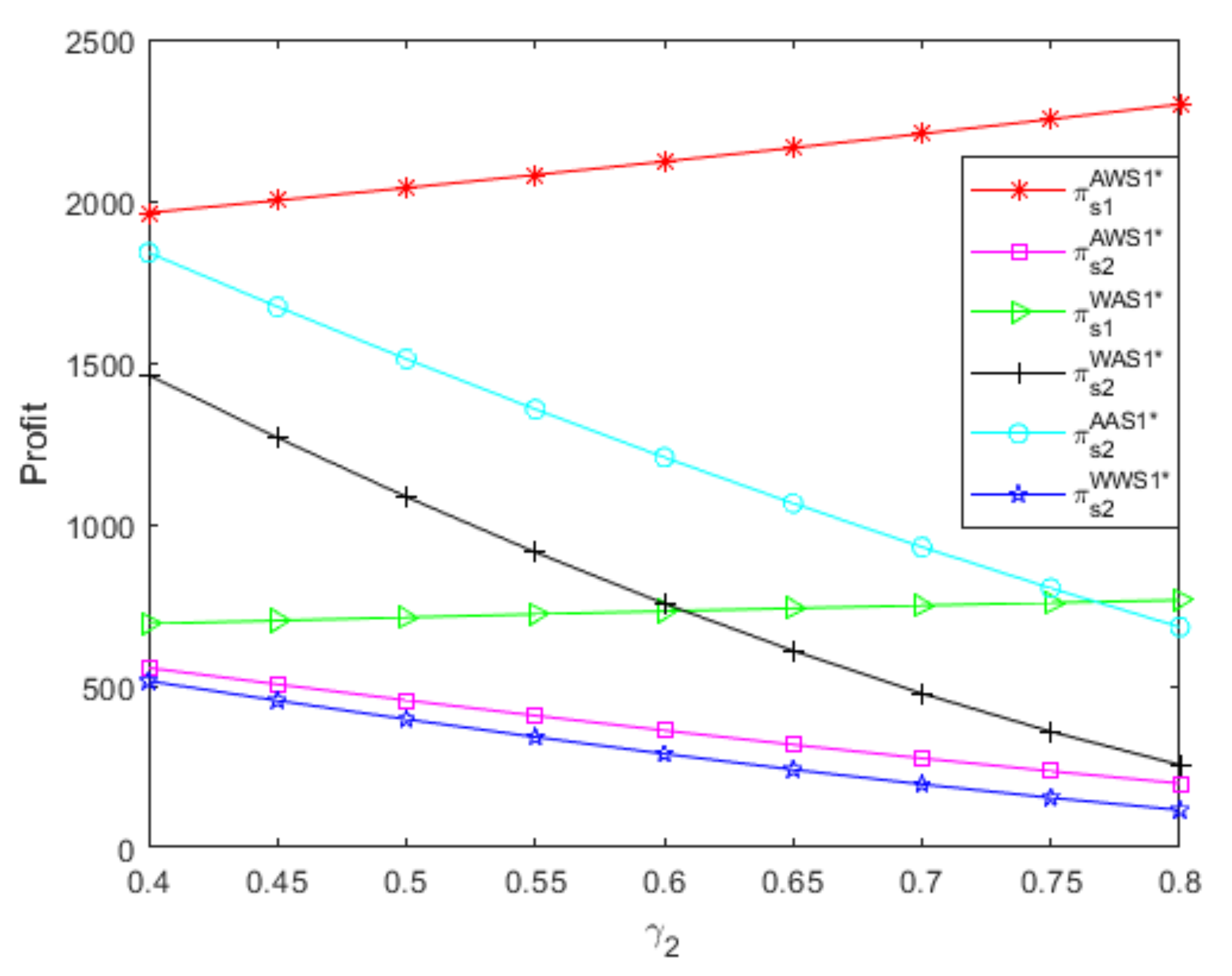

- (2.1)

- From Figure 2, if the small supplier uses an A contract, the profit of the powerful supplier using the A contract decreases as the referral fees increase, but the profit of the powerful supplier using the W contract increases as the referral fees increase; additionally, the A contract is more beneficial to the powerful supplier than the W contract, but the A contract’s advantage decreases as the referral fees increase. Moreover, if the small supplier uses the W contract, the profit of the powerful supplierusing the A contract decreases as the referral fees increase, while the profit of the powerful supplier using the W contract remains unchanged as the referral fees increase; additionally, the A contract is more beneficial to the powerful supplier than the W contract, but the A contract’s advantage decreases as the referral fees increase. Thus, regardless of the small supplier’s distribution contract, the impact of the referral fees on the powerful supplier’s profit depends on the powerful supplier’s distribution contract; additionally, the powerful supplier should choose the A contract, and the A contract’s advantage is larger when the referral fees are relatively low than when the referral fees are relatively high.

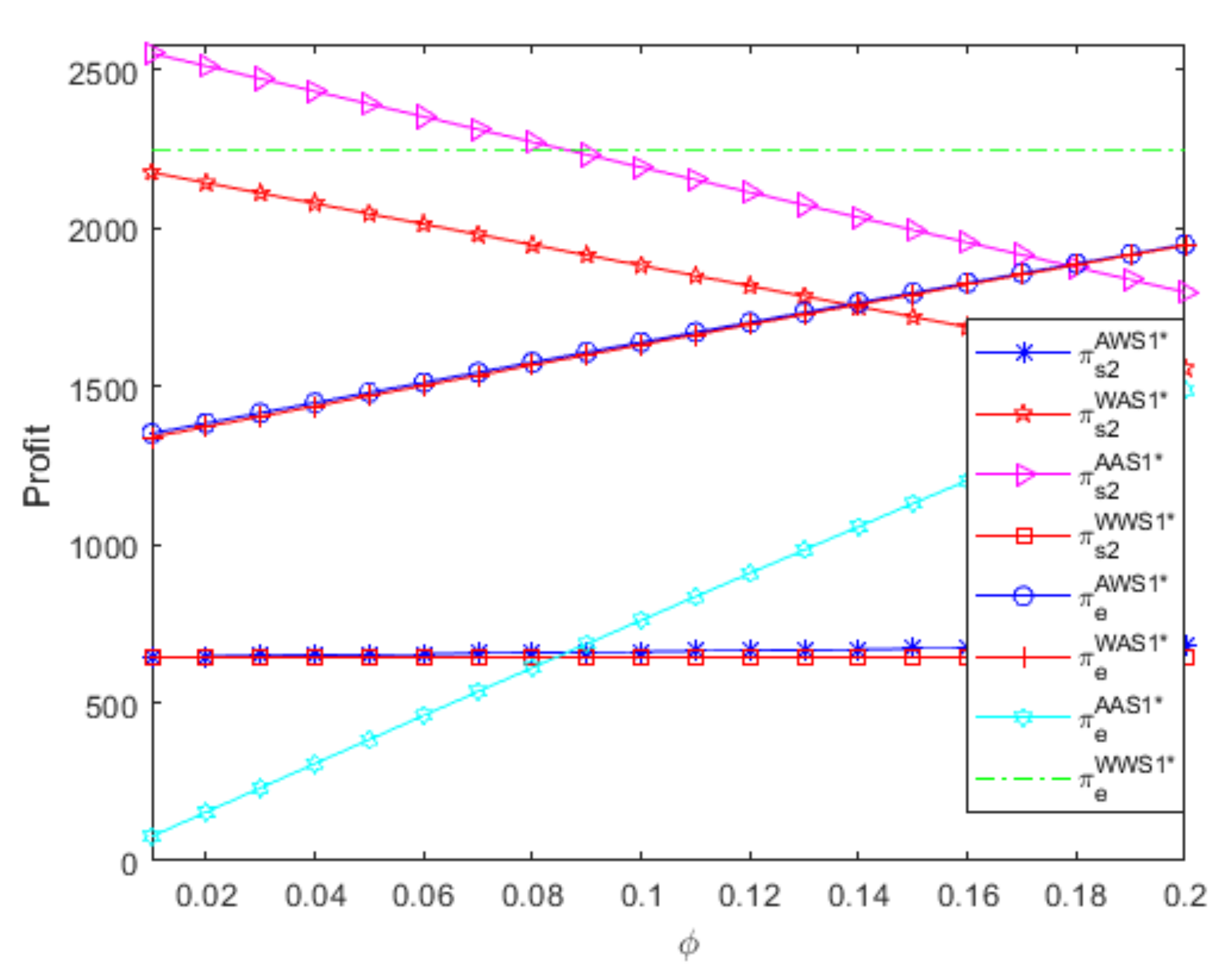

- (2.2)

- From Figure 3, if the powerful supplier uses an A contract, the profit of the small supplier using the W contract increases as the referral fees increase, while the profit of the small supplier using the A contract decreases as the referral fees increase; additionally, the A contract is more beneficial to the small supplier than the W contract, but the A contract’s advantage decreases as the referral fees increase. Furthermore, if the powerful supplier uses the W contract, the profit of the small supplier using the A contract decreases as the referral fees increase, while the profit of the small supplier using the W contract remains unchanged as the referral fees increase; additionally, the A contract is more beneficial to the small supplier than the W contract, but the A contract’s advantage decreases as the referral fees increase. Thus, no matter what distribution contract the powerful supplier uses, the impact of the referral fees on the small supplier’s profit depends onthe small supplier’s distribution contract; additionally, the small supplier should choose the A contract, and the A contract’s advantage is greater when the referral fees are relatively low than when the referral fees are relatively high.

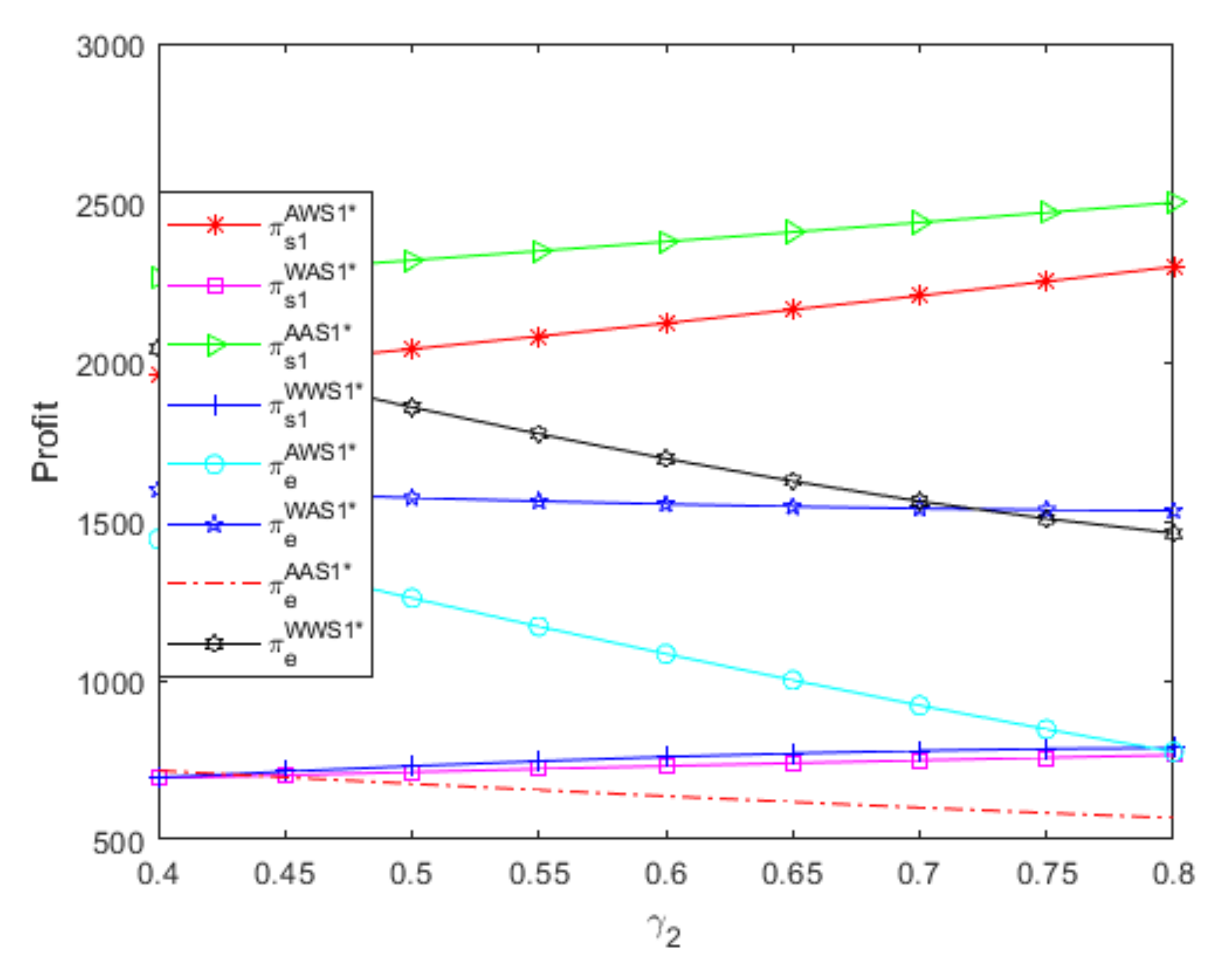

- (3.1)

- Regardless of the referral fees, the e-retailer achieves the highest profit when two suppliers both use a W contract to sell complementary goods with symmetric parameters. Moreover, if two suppliers use different distribution contracts to sell complementary goods with symmetric parameters, although the e-retailer obtains more profits when the powerful supplier uses an A contract and the small supplier uses a W contract than when the powerful supplier uses a W contract and the small supplier uses an A contract, the effect of the two suppliers’ different distribution contracts on the e-retailer’s profit is extremely small and almost disappears as the referral fees increase.

- (3.2)

- If one supplier uses an A contract, although the referral fees have greater positive influences on the e-retailer’s profit when the other supplier also uses an A contract than when the other supplier uses a W contract, the other supplier’s W contract is always more beneficial to the e-retailer than the other supplier’s A contract, which leads to that W contract’s advantage decreases as the referral fees increase. Thus, if one supplier uses an A contract, the e-retailer should attempt to attract the other supplier to use a W contract, and the W contract’s advantage is greater when the referral fees are relatively low than when the referral fees are relatively high.

- (3.3)

- If one supplier uses a W contract, although the e-retailer’s profit is always greater when the other supplier also uses the W contract than when the other supplier uses an A contract, the difference between the e-retailer’s profits under two distribution contracts decreases as the referral fees increase. Therefore, if one supplier uses a W contract, the e-retailer should attempt to attract the other supplier to use a W contract, and the W contract’s advantage is greater when the referral fees are relatively low than when the referral fees are relatively high.

- (3.4)

- If two suppliers use the same distribution contract to sell complementary goods with symmetric parameters, although the two suppliers’ W contracts are more beneficial to the e-retailer than the two suppliers’ A contracts, the difference between the e-retailer’s profits under two distribution contracts decreases as the referral fees increase. Therefore, if two suppliers use the same distribution contract to sell complementary goods with symmetric parameters, letting the two suppliers both use a W contract is the e-retailer’s best choice, and the two suppliers’ distribution contracts have greater influences on the e-retailer’s profit when the referral fees are relatively low than when the referral fees are relatively high.

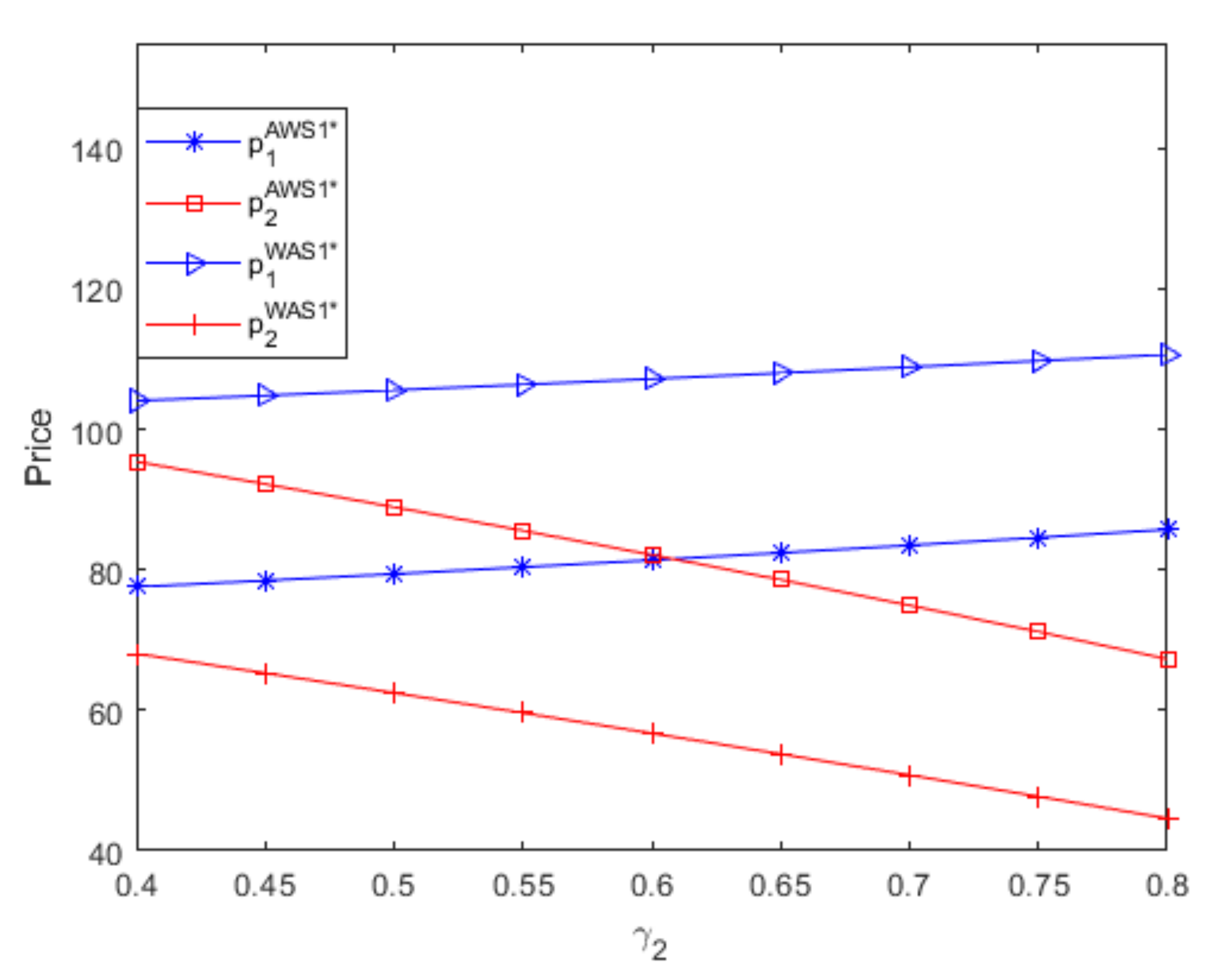

4.2. Impact of Two Goods’ Differences in the Level of Complementarity

- (4.1)

- From Figure 4 and Figure 5, when two suppliers use different distribution contracts to sell goods with different levels of complementarity, the optimal retail price of low-complementarity good produced by the powerful supplier is larger than that of high-complementarity good produced by the small supplier only if the two goods’ differences in the level of complementarity are large enough, and the powerful supplier obtains more profits than the small supplier. If the complementarity of good 1 is greater than that of good 2, we can obtain similar results; namely, when two suppliers use different distribution contracts, only if two goods’ differences in the level of complementarity are large enough, the optimal retail price of the low-complementaritygood produced by the small supplier is greater than that of the high-complementarity good producedby the powerful supplier,and the small supplier obtains bigger profits than the powerful supplier.To limit the number of figures, when two suppliers use different distribution contracts, figures regarding optimal prices and profits if the complementarity of good 1 is greater than that of good 2 are not shown in this article. Thus, when two suppliers use different distribution contracts to sell goods with different levels of complementarity, low-complementarity goods have a greater optimal retail price only if two goods’ differences in the level of complementarity are large enough, and the supplierthat produces goods with lower complementarity obtains more profits regardless ofits distribution contract and channel role.

- (4.2)

- If two suppliers use the same distribution contract to sell goods with different levels of complementarity, although the optimal retail/wholesale price of the low-complementarity good produced by the powerful supplier is greater than that of the high-complementarity good produced by the small supplier, the maximum demand of low-complementarity good produced by the powerful supplier is also larger than that of high-complementarity good produced by the small supplier, which leads to that the powerful supplier that produces low-complementarity goods always benefits more than the small supplier that produces high-complementarity goods. These results are valid regardless of two goods’ differences in the level of complementarity.

- (5.1)

- From Figure 5, regardless of the distribution contract of the powerful supplierthat produces goods with lower complementarity, two goods’ differences in the level of complementarity have greater negative influences on the small supplier’s profit when it uses an A contract than when it uses a W contract, and the A contract is always more profitable than the W contract for the small supplier that produces high-complementarity goods, which results in that A contract’s advantage decreases as two goods’ differences in the level of complementarity increase. Thus, regardless of the distribution contract of the powerful supplier that produces low-complementarity goods, the small supplier that produces high-complementarity goods always prefers an A contract, and the A contract’s advantage is greater when two goods’ differences in the level of complementarity are relatively low than when two goods’ differences in the level of complementarity are relatively high.

- (5.2)

- From Figure 6, no matter what distribution contract the small supplier that produces high-complementarity goods uses, the two goods’ differences in the level of complementarity have greater positive influences on the powerful supplier’s profit when it uses an A contract than when it uses a W contract, and the powerful supplier that produces low-complementarity goods benefits more from an A contract than from a W contract, which leads to that A contract’s advantage increases as two goods’ differences in the level of complementarity increase. Thus, no matter what distribution contract the small supplier that produces high-complementarity goods uses, the powerful supplier that produces low-complementarity goods always prefers the A contract, and the A contract’s advantage is greater when two goods’ differences in the level of complementarity are relatively high than when two goods’ differences in the level of complementarity are relatively low.

- (6.1)

- If the powerful supplier produces low-complementarity goods and uses an A contract, two goods’ differences in the level of complementarity have greater negative influences on the e-retailer’s profit when the small supplier uses a W contract than when the small supplier uses an A contract, and the small supplier’s W contract is more profitable for the e-retailer than the small supplier’s A contract, which leads to that W contract’s advantage decreases as two goods’ differences in the level of complementarity increase. Thus, if the powerful supplier produces low-complementarity goods and uses the A contract, the e-retailer should attract the small supplier to use the W contract, and the W contract’s advantage is greater when two goods’ differences in the level of complementarity are relatively low than when two goods’ differences in the level of complementarity are relatively high.

- (6.2)

- No matter what contract the small supplier that produces high-complementarity goods uses, two goods’ differences in the level of complementarity have larger negative impacts on the e-retailer’s profit when the powerful supplier uses the A contract than when the powerful supplier uses the W contract, and the powerful supplier’s W contract is more beneficial to the e-retailer than the powerful supplier’s A contract, which results in that W contract’s advantage increases as two goods’ differences in the level of complementarity increase. Therefore, regardless of the distribution contract of the small supplier that produces high-complementarity goods, the e-retailer should attract the powerful supplier to use the W contract, and the W contract’s advantage is larger when two goods’ differences in the level of complementarity are relatively high than when two goods’ differences in the level of complementarity are relatively low.

- (6.3)

- If two suppliers use different distribution contracts to sell goods with different levels of complementarity, two goods’ differences in the level of complementarity have larger negative effects on the e-retailer’s profit when the powerful supplier uses the A contract and the small supplier uses the W contract than when the powerful supplier uses the W contract and the small supplier uses the A contract, and the e-retailer obtains more profits when the powerful supplier uses the W contract and the small supplier uses the A contract than when the powerful supplier uses the A contract and the small supplier uses the W contract.

- (6.4)

- If two suppliers use the same distribution contract to sell goods with different levels of complementarity, two goods’ differences in the level of complementarity have greater negative influences on the e-retailer’s profit when the two suppliers use the W contract than when the two suppliers use the A contract, and the two suppliers’ W contracts are more beneficial to the e-retailer than the two suppliers’ A contracts, which results in a situation where the W contract’s advantage is greater when two goods’ differences in the level of complementarity are relatively low than when two goods’ differences in the level of complementarity are relatively high.

4.3. Impact of Two Goods’ Differences in the Potential Demand

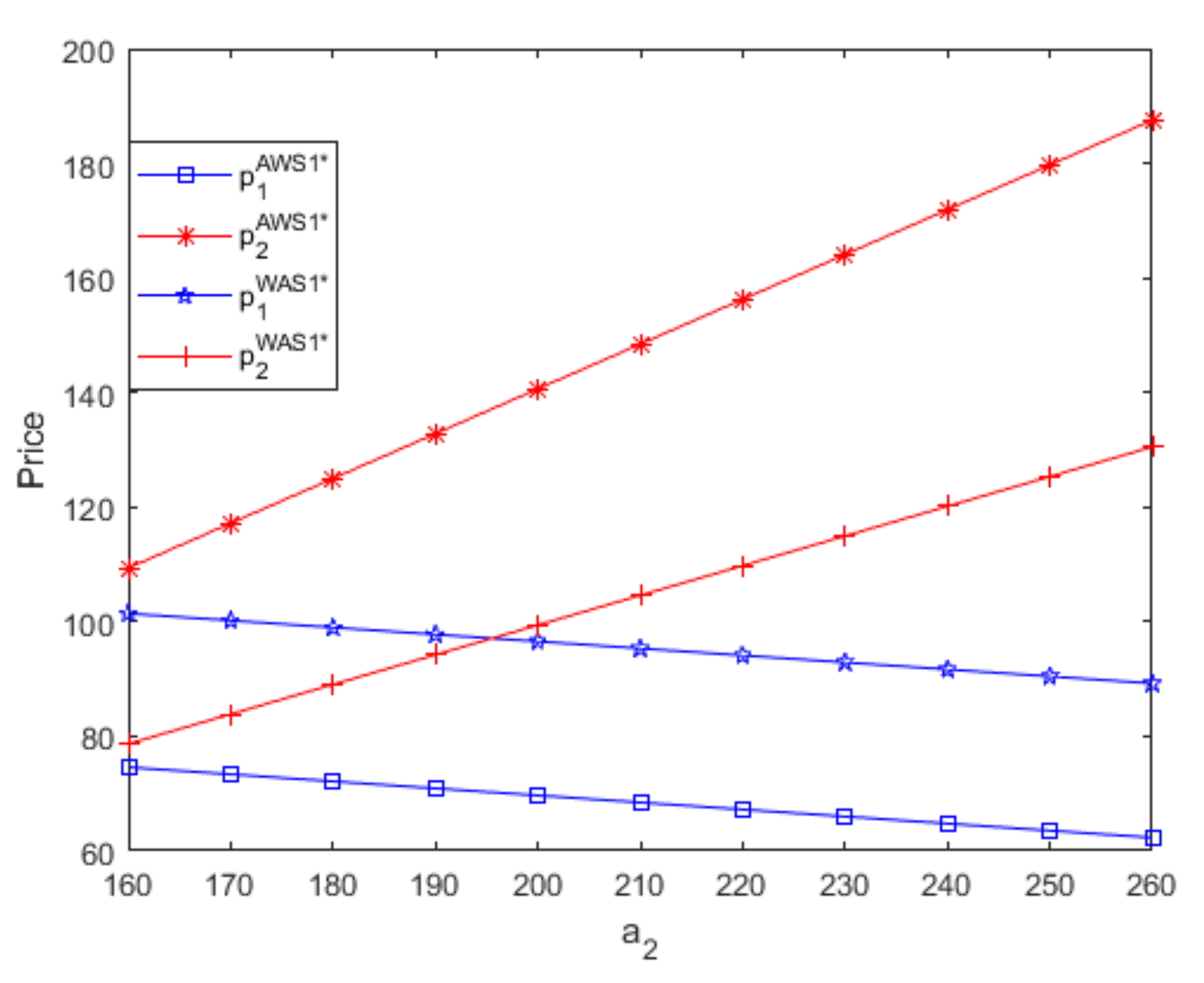

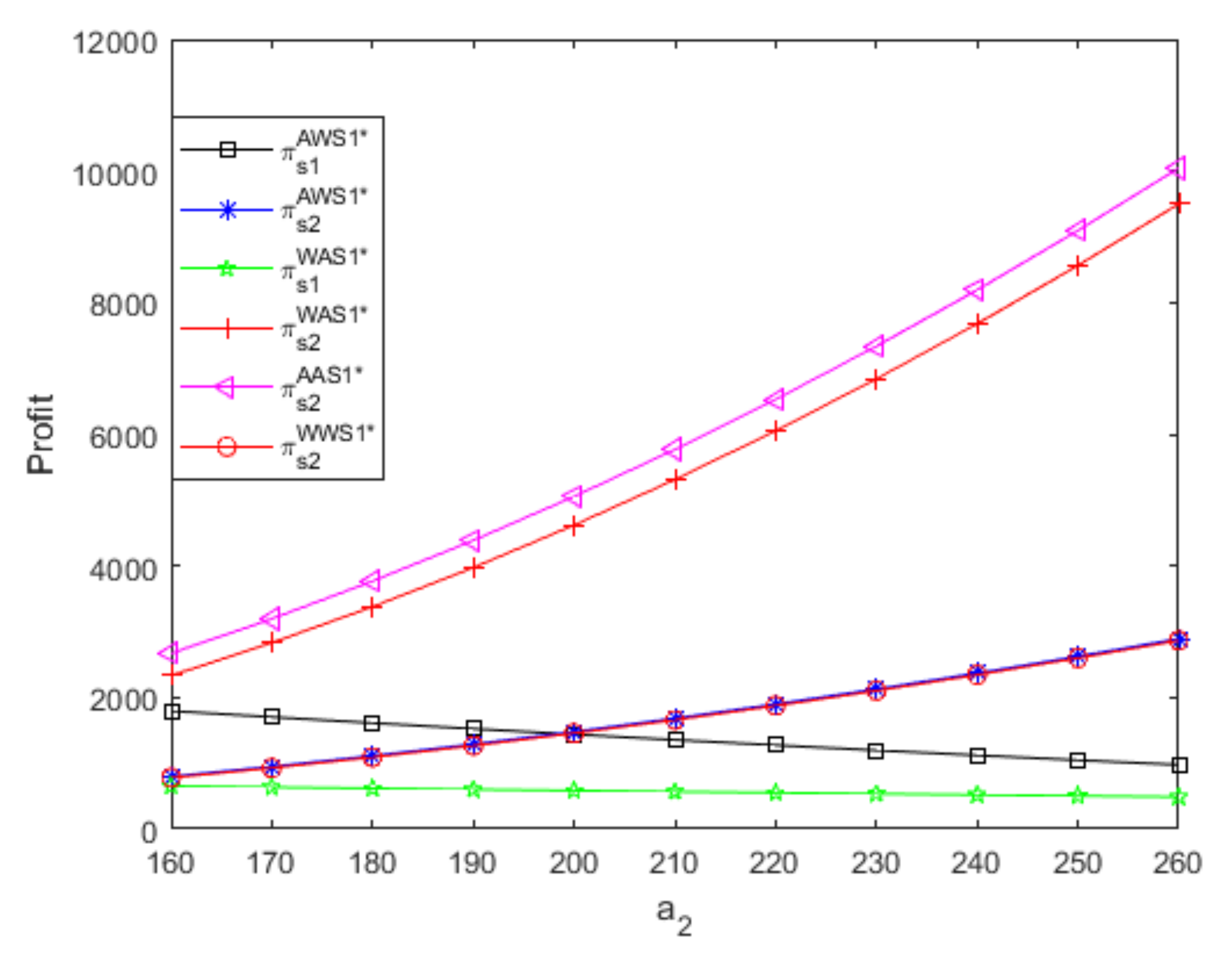

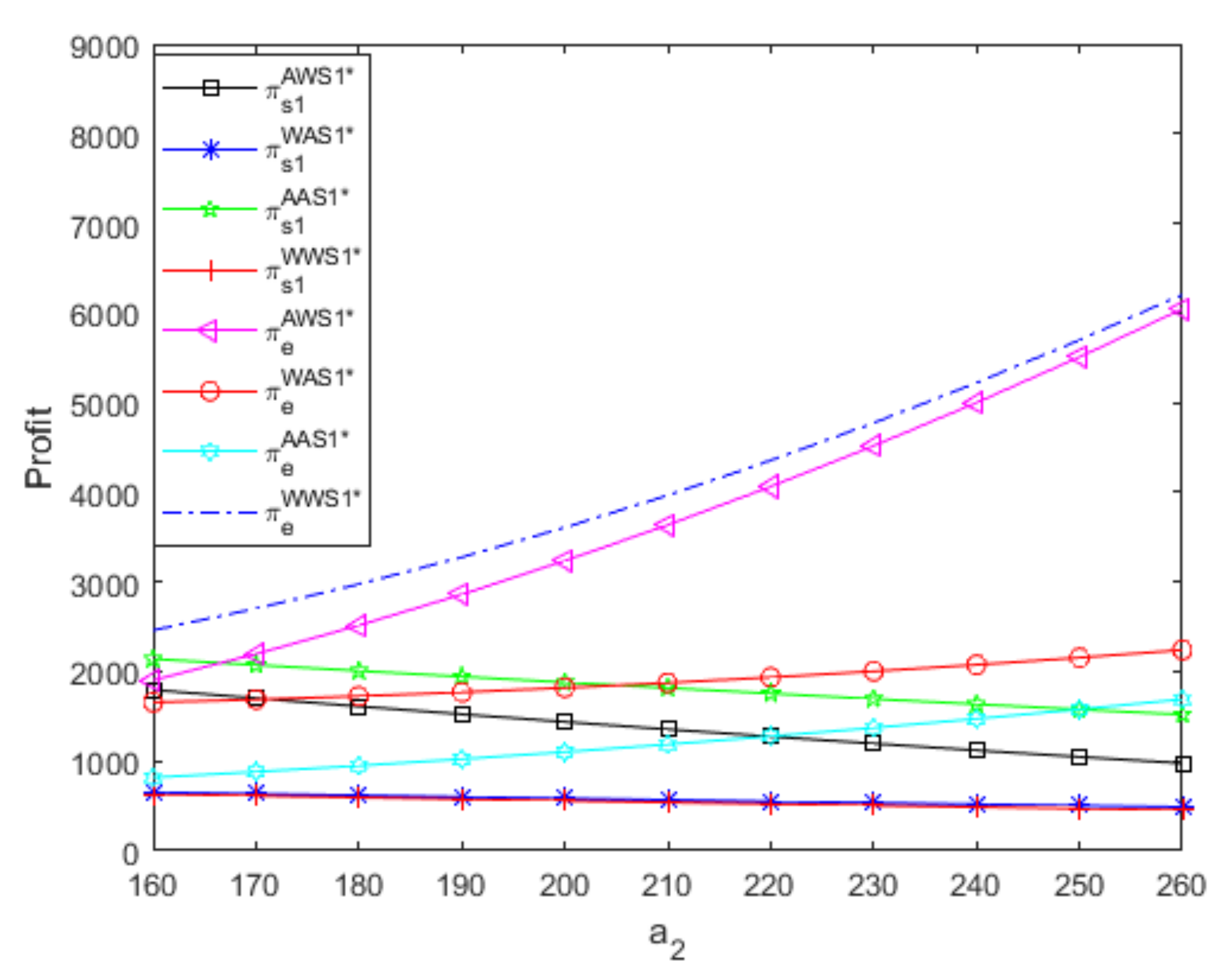

- (7.1)

- Figure 7 and Figure 8 show that, when two suppliers use different distribution contracts to sell complementary goods with different potential demands, the optimal retail price of high-demand good produced by the small supplier is greater than that of low-demand good produced by the powerful supplier only if the goods’ differences in potential demand are large enough, and the small supplier achieves bigger profits than the powerful supplier. If the potential demand of good 1 is greater than that of good 2, similar results appear; namely, when two suppliers use different distribution contracts, the optimal retail price of high-demand good produced by the powerful supplier is larger than that of low-demand good produced by the small supplier only if two goods’ differences in the potential demand are large enough, and the powerful supplier obtains more profits than the small supplier. For brevity, when two suppliers use different distribution contracts, figures regarding optimal prices and profits if the potential demand of good 1 is greater than that of good 2 are not presented in this article. Thus, when two suppliers use different distribution contracts to sell complementary goods with different potential demands, the high-demand good has a greater optimal retail price only if the goods’ differences in potential demand are large enough, and the supplier that produces high-demand goods obtains more profits regardless of its distribution contract and channel role

- (7.2)

- Regardless of two goods’ differences in the potential demand, when two suppliers use the same distribution contract, the high-demand good produced by the small supplier always has a larger optimal wholesale/retail price than low-demand good produced by the powerful supplier, and no matter which distribution contracts the two suppliers both use, the small supplier that produces high-demand goodsalways benefits more than the powerful supplier that produces low-demand goods.

- (8.1)

- From Figure 8, no matter what distribution contract the powerful supplier that produces low-demand goods uses, two goods’ differences in the potential demand have greater positive influences on the small supplier’s profit when it uses the A contract than when it uses the W contract, and the A contract is more profitable than the W contract for the small supplier that produces high-demand goods, which leads to that A contract’s advantage increases as the two goods’ differences in the potential demand increase. Thus, regardless of the distribution contract of the powerful supplier that produces low-demand goods, the small supplier that produces high-demand goods should choose the A contract, and the A contract’s advantage is larger when two goods’ differences in the potential demand are relatively high than when two goods’ differences in the potential demand are relatively low.

- (8.2)

- As illustrated in Figure 9, no matter what distribution contract the small supplier that produces high-demand goods uses, although two goods’ differences in the potential demand have larger negative effects on the powerful supplier’s profit when it uses the A contract than when it uses the W contract, the A contract is always more profitable than the W contract for the powerful supplier that produces low-demand goods, which results in a situation where the A contract’s advantage decreases as two goods’ differences in the potential demand increase. Thus, regardless of the distribution contract of the small supplier that produces high-demand goods, the powerful supplier that produces low-demand goods should choose the A contract, and the A contract’s advantage is larger when two goods’ differences in the potential demand are relatively low than when two goods’ differences in the potential demand are relatively high.

- (9.1)

- Regardless of two suppliers’ distribution contracts and channel roles, the e-retailer’s profit increases as two goods’ differences in the potential demand increase. The e-retailer achieves the maximum profit when two suppliers both use the W contract and achieves the least profit when two suppliers both use the A contract, which is independent of two goods’ differences in the potential demand.

- (9.2)

- If two suppliers use different distribution contracts to sell complementary goods with different potential demands, two goods’ differences in the potential demand have greater positive influences on the e-retailer’s profit when the powerful supplier uses A contract and the small supplier uses W contract than when the powerful supplier uses W contract and the small supplier uses the A contract, and the e-retailer obtains more profits when the powerful supplier uses the A contract and the small supplier uses the W contract than when the powerful supplier uses the W contract and the small supplier uses the A contract.

- (9.3)

- No matter what distribution contract the small supplier that produces high-demand goods uses, although two goods’ differences in the potential demand have greater positive influences on the e-retailer’s profit when the powerful supplier uses the A contract than when the powerful supplier uses the W contract, the powerful supplier’s W contract is more beneficial to the e-retailer than the powerful supplier’s A contract, which results in a situation where the W contract’s advantage decreases as two goods’ differences in the potential demand increase. Thus, no matter what distribution contract the small supplier that produces high-demand goods uses, the e-retailer should guide the powerful supplier to use the W contract, and the W contract’s advantage is larger when two goods’ differences in the potential demand are relatively low than when two goods’ differences in the potential demand are relatively high.

- (9.4)

- Regardless of the distribution contract of the powerful supplier that produces low-demand goods, two goods’ differences in the potential demand have greater positive influences on the e-retailer’s profit when the small supplier uses the W contract than when the small supplier uses the A contract, and the small supplier’s W contract is more profitable for the e-retailer than the small supplier’s A contract, which leads to that the W contract’s advantage increases as two goods’ differences in the potential demand increase. Thus, regardless of the distribution contract of the powerful supplier that produces low-demand goods, the e-retailer should guide the small supplier to use the W contract, and the W contract’s advantage is greater when two goods’ differences in the potential demand are relatively high than when two goods’ differences in the potential demand are relatively low.

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Websites List

Appendix B. Proofs of Propositions 1–4

References

- Abhishek, V.; Jerath, K.; Zhang, Z.J. Agency selling or reselling? Channel structures in electronic retailing. Manag. Sci. 2016, 62, 2259–2280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Q.; Shi, V.; Huang, J. Who benefit from agency model: A strategic analysis of pricing models in distribution channels of physical books and e-books. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2018, 264, 1074–1091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Y.; Zhao, R.; Xing, T. Strategic introduction of the marketplace channel under dual upstream disadvantages in sales efficiency and demand information. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2019, 273, 968–982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geng, X.; Tan, Y.; Wei, L. How add-on pricing interacts with distribution contracts. Prod. Oper. Manag. 2018, 27, 605–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, L.; Vakharia, A.J.; Tan, Y.; Xu, Y. Marketplace, reseller, or hybrid: Strategic analysis of an emerging e-commerce model. Prod. Oper. Manag. 2018, 27, 1595–1610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Y.; Zhao, R.; Liu, Z. Strategic introduction of the marketplace channel under spillovers from online to offline sales. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2018, 267, 65–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Zhang, J. Agency selling or reselling: E-tailer information sharing with supplier offline entry. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2020, 280, 134–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EI-Ansary, A.L.E.; Stern, L.W. Power measurement in the distribution channel. J. Mark. Res. 1972, 9, 47–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, R.; Zhang, J.; Ru, J. Impacts of power structure on supply chains with uncertain demand. Prod. Oper. Manag. 2013, 22, 1232–1249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, J.; Zhao, J.; Li, Y. Pricing decisions for complementary products with firms’ different market powers. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2013, 224, 507–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Z.; Chen, X.; Chen, J.; Wang, X. Optimal pricing policies for differentiated brands under different supply chain power structures. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2017, 259, 437–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Zhang, R.; Liu, B. Pricing decisions of competing supply chains under power imbalance structures. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2018, 125, 695–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukhopadhyay, S.K.; Yue, X.; Zhu, X. A Stackelberg model of pricing of complementary goods under information asymmetry. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2011, 134, 424–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Yan, Y.; Du, H.; Zhao, R. The optimal sales format for green products considering downstream investment. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2020, 58, 1107–1126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, J.; Lu, J.; Wang, Y. How to Choose Online Sales Formats for Competitive E-Tailers, International Transactions in Operational Research. Available online: https://doi.org/10.1111/itor.12777 (accessed on 1 January 2020).

- Zennyo, Y. Strategic contracting and hybrid use of agency and wholesale contracts in e-commerce platforms. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2020, 281, 231–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, Y.; Carrillo, J.E. Strategic analysis of the agency model for digital goods. Prod. Oper. Manag. 2017, 26, 724–741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, J.; Zhao, J.; Hou, X. Bilateral information sharing in two supply chains with complementary products. Appl. Math. Model. 2019, 72, 28–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yue, X.; Mukhopadhyay, S.K.; Zhu, X. A Bertrand model of pricing of complementary goods under information asymmetry. J. Bus. Res. 2006, 59, 1182–1192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karray, S.; Sigue, S.P. Should companies jointly promote their complementary products when they compete in other product categories? Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2016, 255, 620–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinitsyn, M. Coordination of price promotions in complementary categories. Manag. Sci. 2012, 58, 2076–2094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Y.; Yin, S. Joint selling of complementary components under brand and retail competition. Manuf. Serv. Oper. Manag. 2015, 17, 470–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y. Joint pricing-production decisions in supply chains of complementary products with uncertain demand. Oper. Res. 2006, 54, 1110–1127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, S. Alliance formation among perfectly complementary suppliers in a price-sensitive assembly system. Manuf. Serv. Oper. Manag. 2010, 12, 527–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jalali, H.; Ansaripoor, A.H.; Giovanni, P.D. Closed-loop supply chains with complementary products. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2020, 229, 107757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lan, Y.; Cai, X.; Shang, C.; Zhang, L.; Zhao, R. Heterogeneous suppliers’ contract design in assembly systems with asymmetric information. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2020, 286, 149–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, D.; Lan, Y.; Shang, C.; Wang, J.; Xue, C. Impact of trade credit on pricing decisions of complementary products. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2020, 146, 106580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Song, H.; Wang, Y. Pricing and service decisions of complementary products in a dual-channel supply chain. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2017, 105, 223–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F.; Li, S.; Gu, J. Whether to delay the release of eBooks or not? An analysis of optimal publishing strategies for book publishers. J. Theor. Appl. Electron. Commer. Res. 2019, 14, 124–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lou, Y.; He, Z.; Feng, L.; Cai, k.; He, S. Original Design Manufacturer’s Warranty Strategy When Considering Retailers’ Brand Power Under Different Power Structures, International Transactions in Operational Research. Available online: https://doi.org/10.1111/itor.12795 (accessed on 1 April 2020).

- Wang, J.; Wang, Y.; Lai, F. Impact of power structure on supply chain performance and consumer surplus. Int. Trans. Oper. Res. 2019, 26, 1752–1785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsay, A.A.; Agrawal, N. Channel dynamics under price and service competition. Manuf. Serv. Oper. Manag. 2000, 2, 372–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Tang, W. Analysis of network effect in the competition of self-publishing market. J. Theor. Appl. Electron. Commer. Res. 2020, 15, 50–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, B.K.; Raghunathan, S. Retailer- vs. vendor-managed inventory and brand competition. Manag. Sci. 2004, 50, 445–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Articles | Decision-Maker | HCR | Product Status | Problem |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| [1] | One S and two Es | Same | Single | E’s decision on using A or W contract in addition to traditional distribution channel |

| [2] | One S, one RE and one E | Same | Substitutable | SC members’ decisions on using A or W contract in the presence of traditional distribution channel |

| [6] | One S and one E | N/A | Single | Whether to introduce A contract in addition to W contract and traditional distribution channel |

| [7] | One S and one E | N/A | Single | Whether to introduce traditional distribution channel in addition to A or W contract |

| [14] | One S and one E | N/A | Single | A or W contract to complement the S’s online direct channel |

| [3] | One S and one E | N/A | Single | Whether to introduce A contract in addition to W contract |

| [5] | Two Ss and one E | Same | Substitutable | A or W contract |

| [15] | One S and Two Es | Different | Single | A or W contract |

| [16] | Two Ss and one E | Same | Substitutable | A or W contract |

| Our study | Two Ss and one E | Different | Complementary | A or W contract |

| Supplier 2 | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Supplier 1 | W contract | A contract | |

| W contract | WWS1 | WAS1 | |

| A contract | AWS1 | AAS1 | |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wei, J.; Lu, J.; Chen, W.; Xu, Z. Distribution Contract Analysis on e-Platform by Considering Channel Role and Good Complementarity. J. Theor. Appl. Electron. Commer. Res. 2021, 16, 445-465. https://doi.org/10.3390/jtaer16030028

Wei J, Lu J, Chen W, Xu Z. Distribution Contract Analysis on e-Platform by Considering Channel Role and Good Complementarity. Journal of Theoretical and Applied Electronic Commerce Research. 2021; 16(3):445-465. https://doi.org/10.3390/jtaer16030028

Chicago/Turabian StyleWei, Jie, Jinghui Lu, Weiyu Chen, and Zeling Xu. 2021. "Distribution Contract Analysis on e-Platform by Considering Channel Role and Good Complementarity" Journal of Theoretical and Applied Electronic Commerce Research 16, no. 3: 445-465. https://doi.org/10.3390/jtaer16030028

APA StyleWei, J., Lu, J., Chen, W., & Xu, Z. (2021). Distribution Contract Analysis on e-Platform by Considering Channel Role and Good Complementarity. Journal of Theoretical and Applied Electronic Commerce Research, 16(3), 445-465. https://doi.org/10.3390/jtaer16030028