French Translation and Validation of the Ontological Addiction Scale (OAS)

Abstract

:1. Introduction

- Feeling pleased or delighted due to having money and/or material possessions,

- Feeling disappointed, upset or angry due to losing possessions or not acquiring them,

- Feeling pleased when praised or approved of by others,

- Feeling upset or dejected when criticised or subjected to disapproval,

- Feeling pleased due to having a good reputation,

- Feeling dejected or upset due to having a bad reputation,

- Feeling delighted when experiencing sense pleasures,

- Feeling dejected and upset by unpleasant sensory experiences.

2. Study and Methodology

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Participants

2.3. Procedure

2.4. Statistical Analysis

2.4.1. External Validity (Hypothesis Testing)

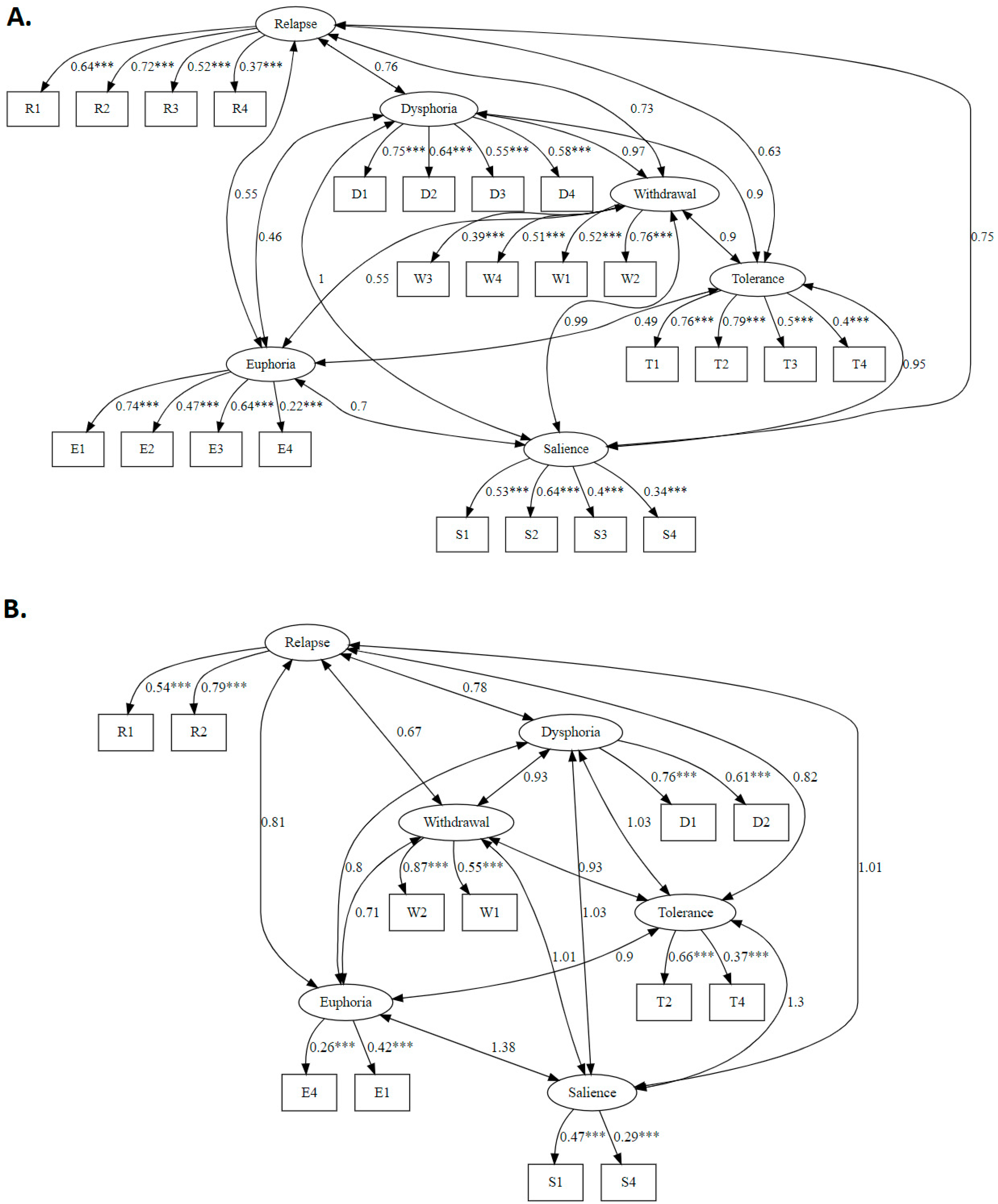

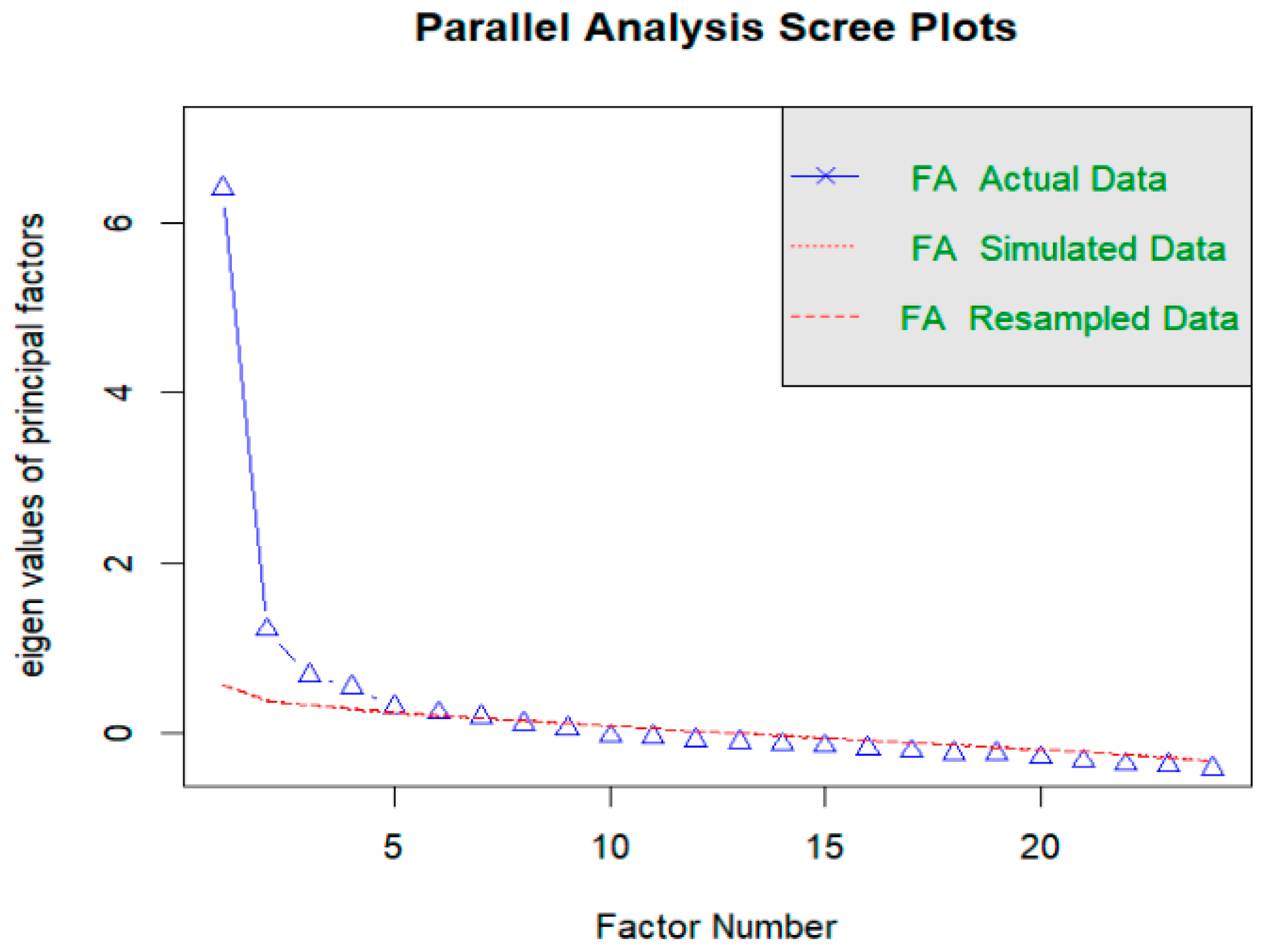

2.4.2. Structural Validity

2.4.3. Reliability (Internal Consistency)

2.4.4. Reliability (Test–Retest)

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Characteristics (Validity, Sample Representativeness and Data Quality)

3.2. Structural Validity

3.3. Reliability (Internal Consistency)

3.4. Reliability: Test–Retest

3.5. External Validity

3.6. Comparison of Psychometric Properties of OAS-24 and OAS-12

4. Discussion

5. Clinical Implications

6. Limitations and Future Directions

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Dimension 1 | Dimension 2 | Dimension 3 | Items not linked to any dimension |

|---|---|---|---|

| 10. Senti(e) que vous deviez mieux faire pour éviter la honte ou l’humiliation? | 11. Senti(e) que vous aviez besoin de plus d’argent ou de possessions matérielles? | 21. Cessé d’être gentil(lle) avec quelqu’un qui vous tient à Cœur car il/elle vous avait critiqué(e)? | 4. Pensé(e) à la façon d’éviter de ressentir un inconfort? |

| 18. Senti(e) inférieur(e) aux autres? | 3. Pensé(e) à augmenter ou protéger votre richesse ou vos biens matériels? | 24. Arrêté(e) d’aider les autres car cela vous causait de l’inconfort? | 8. Senti(e) bien quand vous expérimentiez moins de défis? |

| 14. Eu du mal à faire face aux rejets? | 19. Senti(e) mal après avoir vécu une perte financière ou matérielle? | 23. Senti(e) des regrets après avoir offert un cadeau? | |

| 9. Senti(e) que vous deviez faire plus d’efforts pour recevoir des éloges ou éviter des critiques? | 7. Senti(e) exalté(e) après un gain financier ou matériel? | 6. Senti(e) supérieure aux autres? | |

| 17. Senti(e) mal après avoir été critiqué(e)? | 16. Eu du mal à vivre plus simplement? | 5. Senti(e) exalté(e) après avoir été complimenté(e)? | |

| 2. Pensé(e) à la manière dont les autres vous voient? | 15. Eu du mal à donner quelque chose? | ||

| 20. Senti(e) mal après avoir vécu des circonstances difficiles? | |||

| 13. Eu du mal à accepter vos erreurs et défauts? | |||

| 22. Senti(e) inquiète de ne pas être reconnu(e) après avoir agi dans l’intérêt des autres? | |||

| 1. Senti(e) que vous aviez besoin de recevoir plus d’attention ou d’affection d’une personne qui vous tient à cœur? | |||

| 12. Senti(e) que vous aviez de plus en plus besoin de vous occuper pour éviter d’être seul(e)? |

Appendix B

| Item | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Factor 1 | Factor 2 | CITC | |

| S1. Felt you needed to receive more attention or affection from a person you care about? | 0.464 | 0.250 | 0.52 |

| S2. Thought about how others see you? | 0.617 | 0.217 | 0.60 |

| S3. Thought about increasing or protecting your wealth or material possessions? | 0.098 | 0.626 | 0.48 |

| S4. Thought about how you could avoid experiencing discomfort? | 0.260 | 0.236 | 0.36 |

| E1. Felt uplifted when you were praised? | 0.231 | 0.430 | 0.47 |

| E2. Felt superior to others? | 0.009 | 0.385 | 0.27 |

| E3. Felt uplifted when you experienced financial or material gain? | 0.174 | 0.547 | 0.49 |

| E4. Felt good when you experienced fewer challenges? | 0.159 | 0.260 | 0.29 |

| T1. Felt you needed to try harder in order to receive praise or avoid criticism? | 0.683 | 0.198 | 0.64 |

| T2. Felt you needed to do better in order to avoid shame or humiliation? | 0.718 | 0.216 | 0.68 |

| T3. Felt you needed more money or material possessions? | 0.256 | 0.571 | 0.56 |

| T4. Felt an increasing need to occupy yourself to avoid being on your own? | 0.313 | 0.253 | 0.41 |

| W1. Found it hard to accept your mistakes and shortcomings? | 0.467 | 0.146 | 0.45 |

| W2. Found it hard to overcome rejection? | 0.719 | 0.228 | 0.68 |

| W3. Found it hard to give something away? | 0.196 | 0.430 | 0.44 |

| W4. Found it hard to live more simply? | 0.363 | 0.390 | 0.54 |

| D1. Felt low when you were criticised? | 0.697 | 0.244 | 0.68 |

| D2. Felt inferior to others? | 0.670 | 0.093 | 0.56 |

| D3. Felt low when you encountered financial or material loss? | 0.335 | 0.583 | 0.63 |

| D4. Felt low when you encountered difficult circumstances? | 0.576 | 0.145 | 0.52 |

| R1. Stopped being kind to somebody you care about because they offended you? | 0.302 | 0.437 | 0.53 |

| R2. Felt worried about not being recognised after having acted in others’ interests? | 0.507 | 0.308 | 0.59 |

| R3. Felt regret after having given a gift? | 0.150 | 0.479 | 0.44 |

| R4. Stopped helping others because it was causing discomfort or inconvenience? | 0.087 | 0.317 | 0.29 |

| Item | OAS-24 (α = 0.89; ω = 0.81) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Factor 1 | Factor 2 | Factor 3 | Factor 4 | CITC | |

| S1. Felt you needed to receive more attention or affection from a person you care about? | 0.468 | 0.088 | 0.173 | 0.210 | 0.52 |

| S2. Thought about how others see you? | 0.619 | 0.175 | 0.066 | 0.143 | 0.60 |

| S3. Thought about increasing or protecting your wealth or material possessions? | 0.082 | 0.602 | 0.229 | 0.172 | 0.48 |

| S4. Thought about how you could avoid experiencing discomfort? | 0.255 | 0.184 | 0.136 | 0.071 | 0.36 |

| E1. Felt uplifted when you were praised? | 0.251 | 0.163 | 0.099 | 0.601 | 0.47 |

| E2. Felt superior to others? | 0.009 | 0.047 | 0.217 | 0.541 | 0.27 |

| E3. Felt uplifted when you experienced financial or material gain? | 0.180 | 0.452 | 0.019 | 0.515 | 0.49 |

| E4. Felt good when you experienced fewer challenges? | 0.147 | 0.218 | 0.204 | −0.005 | 0.29 |

| T1. Felt you needed to try harder in order to receive praise or avoid criticism? | 0.677 | 0.165 | 0.106 | 0.081 | 0.64 |

| T2. Felt you needed to do better in order to avoid shame or humiliation? | 0.711 | 0.269 | 0.084 | −0.008 | 0.68 |

| T3. Felt you needed more money or material possessions? | 0.232 | 0.767 | 0.049 | 0.124 | 0.56 |

| T4. Felt an increasing need to occupy yourself to avoid being on your own? | 0.309 | 0.142 | 0.178 | 0.126 | 0.41 |

| W1. Found it hard to accept your mistakes and shortcomings? | 0.467 | 0.101 | 0.068 | 0.098 | 0.45 |

| W2. Found it hard to overcome rejection? | 0.724 | 0.126 | 0.106 | 0.197 | 0.68 |

| W3. Found it hard to give something away? | 0.165 | 0.291 | 0.457 | −0.011 | 0.44 |

| W4. Found it hard to live more simply? | 0.354 | 0.343 | 0.193 | 0.100 | 0.54 |

| D1. Felt low when you were criticised? | 0.695 | 0.104 | 0.199 | 0.159 | 0.68 |

| D2. Felt inferior to others? | 0.665 | 0.215 | 0.090 | −0.201 | 0.56 |

| D3. Felt low when you encountered financial or material loss? | 0.316 | 0.616 | 0.238 | 0.081 | 0.63 |

| D4. Felt low when you encountered difficult circumstances? | 0.564 | 0.117 | 0.164 | −0.024 | 0.52 |

| R1. Stopped being kind to somebody you care about because they offended you? | 0.282 | 0.110 | 0.553 | 0.174 | 0.53 |

| R2. Felt worried about not being recognised after having acted in others’ interests? | 0.511 | 0.022 | 0.350 | 0.235 | 0.59 |

| R3. Felt regret after having given a gift? | 0.113 | 0.193 | 0.598 | 0.107 | 0.44 |

| R4. Stopped helping others because it was causing discomfort or inconvenience? | 0.064 | 0.033 | 0.477 | 0.107 | 0.29 |

Appendix C

| A Quelle Fréquence, Durant l’Année Ecoulée, Avez-Vous ou Vous Etes-Vous: | Jamais | Rarement | Parfois | Souvent | Toujours |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Senti(e) que vous aviez besoin de recevoir plus d’attention ou d’affection d’une personne qui vous tient à cœur? | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 2. Pensé(e) à la manière dont les autres vous voient? | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 3. Pensé(e) à augmenter ou protéger votre richesse ou vos bien matériels? | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 4. Pensé(e) à la façon d’éviter de ressentir un inconfort? | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 5. Senti(e) exalté(e) après avoir été complimenté(e)? | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 6. Senti(e) supérieur(e) aux autres? | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 7. Senti(e) exalté(e) après un gain financier ou matériel? | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 8. Senti(e) bien quand vous expérimentiez moins de défis? | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 9. Senti(e) que vous deviez faire plus d’efforts pour recevoir des éloges ou éviter des critiques? | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 10. Senti(e) que vous deviez mieux faire pour éviter la honte ou l’humiliation? | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 11. Senti(e) que vous aviez besoin de plus d’argent ou de possessions matérielles? | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 12. Senti(e) que vous aviez de plus en plus besoin de vous occuper pour éviter d’être seul(e) avec vous-même? | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 13. Eu du mal à accepter vos erreurs et défauts? | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 14. Eu du mal à faire face au rejet? | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 15. Eu du mal à donner quelque chose? | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 16. Eu du mal à vivre plus simplement? | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 17. Senti(e) mal après avoir été critiqué(e)? | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 18. Senti(e) inférieur(e) aux autres? | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 19. Senti(e) mal après avoir vécu une perte financière ou matérielle? | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 20. Senti(e) mal après avoir vécu des circonstances difficiles? | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 21. Cessé(e) d’être gentil(le) avec quelqu’un qui vous tient à cœur car il/elle vous avait critiqué(e)? | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 22. Senti(e) inquiet(e) de ne pas être reconnu(e) après avoir agi dans l’intérêt des autres? | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 23. Senti(e) des regrets après avoir offert un cadeau? | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 24. Arrêté(e) d’aider les autres car cela vous causait de l’inconfort? | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| Total: | /96 |

| A Quelle Fréquence, Durant l’Année Ecoulée, Avez-Vous ou Vous Etes-Vous: | Jamais | Rarement | Parfois | Souvent | Toujours |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Senti(e) que vous aviez besoin de recevoir plus d’attention ou d’affection d’une personne qui vous tient à cœur? | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 2. Pensé(e) à la façon d’éviter de ressentir un inconfort? | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 3. Senti(e) exalté(e) après avoir été complimenté(e)? | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 4. Senti(e) bien quand vous expérimentiez moins de défis? | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 5. Senti(e) que vous deviez mieux faire pour éviter la honte ou l’humiliation? | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 6. Senti(e) que vous aviez besoin de plus d’argent ou de possessions matérielles? | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 7. Senti(e) que vous aviez de plus en plus besoin de vous occuper pour éviter d’être seul(e) avec vous-même? | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 8. Eu du mal à donner quelque chose? | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 9. Eu du mal à vivre plus simplement? | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 10. Senti(e) mal après avoir vécu une perte financière ou matérielle? | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 11. Senti(e) mal après avoir vécu des circonstances difficiles? | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 12. Cessé(e) d’être gentil(le) avec quelqu’un qui vous tient à cœur car il/elle vous avait critiqué(e)? | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| Total: | /48 |

References

- Kraemer, H.C. DSM categories and dimensions in clinical and research contexts. Int. J. Methods Psychiatr. Res. 2007, 16, S8–S15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hyman, S.E. The diagnosis of mental disorders: The problem of reification. Annu. Rev. Clin. Psychol. 2010, 6, 155–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krueger, R.F.; Kotov, R.; Watson, D.; Forbes, M.K.; Eaton, N.R.; Ruggero, C.J.; Simms, L.J.; Widiger, T.A.; Achenbach, T.M.; Bach, B.; et al. Progress in achieving quantitative classification of psychopathology. World Psychiatry 2018, 17, 282–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zandersen, M.; Parnas, J. Borderline personality disorder or a disorder within the schizophrenia spectrum? A psychopathological study. World Psychiatry 2019, 18, 109–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Gordon, W.; Shonin, E.; Diouri, S.; Garcia-Campayo, J.; Kotera, Y.; Griffiths, M.D. Ontological addiction theory: Attachment to me, mine, and I. J. Behav. Addict. 2018, 7, 892–896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gyatso, G.K. How to Understand the Mind: The Nature and Power of the Mind; Tharpa Publications: London, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Ducasse, D.; Van Gordon, W.; Courtet, P.; Olié, E. Self-injury and self-concept. J. Affect. Disord. 2019, 258, 115–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calderone, A.; Latella, D.; Impellizzeri, F.; de Pasquale, P.; Famà, F.; Quartarone, A.; Calabrò, R.S. Neurobiological changes induced by mindfulness and meditation: A systematic review. Biomedicines 2024, 12, 2613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrows, P.; Van Gordon, W. Ontological Addiction Theory and mindfulness-based approaches in the context of addiction theory and treatment. Religions 2021, 12, 586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carmichael, J. Paying attention: An examination of attention and empathy as they relate to Buddhist philosophy. Religions 2022, 13, 108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahdra, B.; Ciarrochi, J.; Parker, P. Nonattachment and mindfulness: Related but distinct constructs. Psychol. Assess. 2016, 28, 819–829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahdra, B.K.; Shaver, P.R.; Brown, K.W. A scale to measure Nonattachment: A Buddhist complement to Western research on attachment and adaptive functioning. J. Pers. Assess. 2010, 92, 116–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Whitehead, R.; Bates, G.; Elphinstone, B.; Yang, Y.; Murray, G. Letting go of self: The creation of the Nonattachment to Self Scale. Front. Psychol. 2018, 9, 2544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitehead, R.; Bates, G.; Elphinstone, B. Growing by letting go: Nonattachment and mindfulness as qualities of advanced psychological development. J. Adult Dev. 2020, 27, 12–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meling, D. Knowing the Knowing. Non-dual Meditative Practice From an Enactive Perspective. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 778817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costines, C.; Borghardt, T.L.; Wittmann, M. The phenomenology of “pure” consciousness as reported by an experienced meditator of the Tibetan Buddhist Karma Kagyu tradition. Analysis of interview content concerning different meditative states. Philosophies 2021, 6, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horiuchi, T. Disputed emptiness: Vimalamitra’s Mādhyamika interpretation of the Heart Sutra in the light of his criticism on other schools. Religions 2022, 13, 1067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrows, P.; Shonin, E.; Sapthiang, S.; Griffiths, M.D.; Ducasse, D.; Van Gordon, W. The development and validation of the Ontological Addiction Scale. Int. J. Ment. Health Addict. 2022, 21, 4043–4070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekşi, H.; Şekerc, S. Turkish Adaptation of the Ontological Addiction Scale. In Proceedings of the International Antalya Scientific Research and Innovative Studies Congress, Antalya, Turkey, 2–4 December 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Griffiths, M. A ‘components’ model of addiction within a biopsychosocial framework. J. Subst. Use 2005, 10, 191–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagarjuna, K.K.R. Nagarjuna’s Letter to a Friend: With Commentary by Kyabje Kangyur Rinpoche; Snow Lion Publications: New York, NY, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Mokkink, L.B.; Terwee, C.B.; Knol, D.L.; Stratford, P.W.; Alonso, J.; Patrick, D.L.; Bouter, L.M.; de Vet, H.C.W. The COSMIN checklist for evaluating the methodological quality of studies on measurement properties: A clarification of its content. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2010, 10, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenberg, M. Society and the Adolescent Self-Image; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 1965. [Google Scholar]

- Vallières, E.F.; Vallerand, R.J. Traduction et validation canadienne-française de l’échelle de l’estime de soi de Rosenberg. Int. J. Psychol. 1990, 25, 305–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tangney, J.P.; Dearing, R.; Wagner, P.; Gramzow, R. The Test of Self-Conscious- Affect 3 (TOSCA-3); George Mason University: Fairfax, VA, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nugier, A.; Gil, S.; Chekroun, P. French validation of the Test of self-conscious affect-3 (TOSCA-3): A measure for the tendencies to feel ashamed andguilty. Eur. Rev. Appl. Psychol. 2012, 62, 19–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hewitt, P.L.; Flett, G.L. Perfectionism and depression: A multidimensional analysis. J. Soc. Behav. Pers. 1990, 5, 423–438. [Google Scholar]

- Labrecque, J.P.; Stephenson, R.; Boivin, I. Validation de l’Échelle multidimensionnelle du perfectionnisme auprès de la francophone du Québec. Rev. Francoph. Clin. Comport. Cogn. 1999, 3, 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Jermann, F.; Billieux, J.; Laroi, F. Mindfull Attention Awareness Scale (MAAS): Psychometric properties of the French translation and exploration of its relations with emotion regulation strategies. Psychol. Assess. 2009, 21, 506–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCullough, M.E.; Emmons, R.A.; Tsang, J.-A. The grateful disposition: A conceptual and empirical topography. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2002, 82, 112–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tachon, G.; Shankland, R.; Marteau-Chasserieau, F.; Morgan, B.; Leys, C.; Kotsou, I. Gratitude moderates the relation between daily hassles and satisfaction with life in university students. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 13005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Izquierdo, I.; Olea, J.; Abad, F.J. Exploratory factor analysis in validation studies: Uses and recommendations. Psicothema 2014, 26, 395–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harman, H.H.; Jones, W.H. Factor analysis by minimizing residuals (minres). Psychometrika 1966, 31, 351–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Béland, S.; Cousineau, D.; Loye, N. Using The McDonald’s Omega Coefficient Instead of Cronbach’s Alpha. McGill J. Educ. 2018, 53, 791–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, A.F.; Coutts, J.J. Use Omega rather than Cronbach’s Alpha for estimating reliability. But…. Commun. Methods Meas. 2020, 14, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldberg, L.R.; Velicer, W.F. Principles of exploratory factor analysis. In Differentiating Normal and Abnormal Personality, 2nd ed.; Stack, S., Ed.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2006; pp. 209–237. [Google Scholar]

- Barrows, P.; Van Gordon, W.; Richardson, M. Self-transcendence through the lens of ontological addiction: Correlates of prosociality, competitiveness and pro-nature behavior. Curr. Psychol. 2024, 43, 28950–28964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeYoung, C.G.; Krueger, R.F. A cybernetic perspective on the nature of psychopathology: Transcending conceptions of mental illness as statistical deviance and brain disease. J. Psychopathol. Clin. Sci. 2023, 132, 228–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morris, S.E.; Sanislow, C.A.; Pacheco, J.; Vaidyanathan, U.; Gordon, J.A.; Cuthbert, B.N. Revisiting the seven pillars of RDoC. BMC Med. 2022, 20, 220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salzberg, S.; Kabat-Zinn, J. Lovingkindness: The Revolutionary Art of Happiness; Shambhala Publications, Incorporated: Boulder, CO, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert, P. The Compassionate Mind: A New Approach to Life’s Challenges; New Harbinger Publications: Alameda, CA, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Dahl, C.J.; Lutz, A.; Davidson, R.J. Reconstructing and deconstructing the self: Cognitive mechanisms in meditation practice. Trends Cogn. Sci. 2015, 19, 515–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Gordon, W.; Shonin, E.; Dunn, T.J.; Sapthiang, S.; Kotera, Y.; Garcia-Campayo, J.; Sheffield, D. Exploring emptiness and its effects on non-attachment, mystical experiences, and psycho-spiritual wellbeing: A quantitative and qualitative study of advanced meditators. Explore 2019, 15, 261–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Component | Positive | Negative |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Material wealth/possessions | Delight about gain | Distress about loss or non- acquisition |

| 2. Sensations | Delight at pleasurable sensations | Distress from painful or unpleasant sensations |

| 3. Others’ perception of us (friends, colleagues, family) | Delighted with praise | Distress from disapproval or criticism |

| 4. Others’ perception of us (general reputation) | Delighted with good reputation | Distress from bad reputation |

| Salience (i.e., ego-centred activities are the most important in the person’s life, and dominate their thinking, feelings and behaviours) | S1. Felt you needed to receive more attention or affection from a person you care about? S2. Thought about how others see you? S3. Thought about increasing or protecting your wealth or material possessions? S4. Thought about how you could avoid experiencing discomfort? |

| Euphoria (i.e., ego-centred occurrences impact mood in a positive way) | E1. Felt uplifted when you were praised? E2. Felt superior to others? E3. Felt uplifted when you experienced financial or material gain? E4. Felt good when you experienced fewer challenges? |

| Tolerance (i.e., one needs to constantly increase ego-centred behaviour to feel well) | T1. Felt you needed to try harder in order to receive praise or avoid criticism? T2. Felt you needed to do better in order to avoid shame or humiliation? T3. Felt you needed more money or material possessions? T4. Felt an increasing need to occupy yourself to avoid being on your own? |

| Withdrawal (i.e., unpleasant feeling occurs when ego-centred behaviour is reduced) | W1. Found it hard to accept your mistakes and shortcomings? W2. Found it hard to overcome rejection? W3. Found it hard to give something away? W4. Found it hard to live more simply? |

| Dysphoria (i.e., interpersonal or intrapsychic conflicts resulting from ego-centred behaviour) | D1. Felt low when you were criticised? D2. Felt inferior to others? D3. Felt low when you encountered financial or material loss? D4. Felt low when you encountered difficult circumstances? |

| Relapse (i.e., the tendency for repeated reversions to ego-centeredness following a period of being less self-centred) | R1. Stopped being kind to somebody you care about because they criticised you? * R2. Felt worried about not being recognised after having acted in others’ interests? R3. Felt regret after having given a gift? R4. Stopped helping others because it was causing discomfort? ** |

| Measure | n | Mean | SD | 95% Confidence Interval | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower Bound | Upper Bound | ||||

| Age | 489 | 37.7 | 12.9 | 36.6 | 38.9 |

| OAS-24 | 453 | 53.6 | 14.0 | 52.3 | 5.9 |

| OAS-12 | 466 | 30.3 | 7.5 | 29.6 | 30.9 |

| TOSCA-3-SS | 433 | 36.9 | 11.7 | 35.8 | 38.0 |

| RSES | 451 | 13.3 | 6.4 | 12.7 | 13.9 |

| MAAS | 435 | 38.1 | 13.0 | 36.9 | 39.3 |

| GQ-6 | 489 | 20.5 | 8.01 | 19.8 | 21.2 |

| SOP-MPS | 437 | 56.4 | 17.3 | 54.7 | 58.0 |

| Model | χ2 | df | χ2/df | TLI | CFI | RMSEA | SRMR | Coeff > 0.05 | Loading < 0.30 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OAS-24 | 927 | 237 | 3.9 | 0.77 | 0.80 | 0.08 | 0.07 | – | E4 |

| OAS-12 | 122 | 39 | 3.1 | 0.90 | 0.94 | 0.07 | 0.04 | – | S4, E4 |

| Factor | Total | % of Variance | Cumulative % |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 7.17 | 30 | 30 |

| 2 | 1.94 | 8 | 38 |

| 3 | 1.46 | 6 | 44 |

| 4 | 1.33 | 6 | 50 |

| 5 | 1.07 | 4 | 54 |

| 6 | 1.03 | 4 | 58 |

| Item Groups: Salience (S1-7), Ego Euphoria (E1-5), Tolerance (T1-5), Dysphoria (D1-4), Withdrawal (W1-4) and Relapse (R1-6) | OAS-24 (α = 0.89; ω = 0.81) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Factor 1 | Factor 2 | Factor 3 | CITC | |

| S1. Felt you needed to receive more attention or affection from a person you care about? | 0.455 | 0.119 | 0.270 | 0.517 |

| S2. Thought about how others see you? | 0.609 | 0.200 | 0.129 | 0.602 |

| S3. Thought about increasing or protecting your wealth or material possessions? | 0.074 | 0.631 | 0.238 | 0.479 |

| S4. Thought about how you could avoid experiencing discomfort? | 0.254 | 0.200 | 0.137 | 0.361 |

| E1. Felt uplifted when you were praised? | 0.218 | 0.241 | 0.385 | 0.473 |

| E2. Felt superior to others? | −0.012 | 0.130 | 0.456 | 0.273 |

| E3. Felt uplifted when you experienced financial or material gain? | 0.159 | 0.476 | 0.279 | 0.488 |

| E4. Felt good when you experienced fewer challenges? | 0.153 | 0.218 | 0.146 | 0.294 |

| T1. Felt you needed to try harder in order to receive praise or avoid criticism? | 0.676 | 0.180 | 0.127 | 0.641 |

| T2. Felt you needed to do better in order to avoid shame or humiliation? | 0.717 | 0.273 | 0.044 | 0.675 |

| T3. Felt you needed more money or material possessions? | 0.224 | 0.786 | 0.048 | 0.562 |

| T4. Felt an increasing need to occupy yourself to avoid being on your own? | 0.303 | 0.162 | 0.215 | 0.407 |

| W1. Found it hard to accept your mistakes and shortcomings? | 0.461 | 0.119 | 0.110 | 0.448 |

| W2. Found it hard to overcome rejection? | 0.707 | 0.159 | 0.206 | 0.684 |

| W3. Found it hard to give something away? | 0.182 | 0.292 | 0.323 | 0.439 |

| W4. Found it hard to live more simply? | 0.352 | 0.363 | 0.188 | 0.538 |

| D1. Felt low when you were criticised? | 0.687 | 0.131 | 0.261 | 0.683 |

| D2. Felt inferior to others? | 0.675 | 0.192 | −0.053 | 0.559 |

| D3. Felt low when you encountered financial or material loss? | 0.317 | 0.620 | 0.197 | 0.625 |

| D4. Felt low when you encountered difficult circumstances? | 0.568 | 0.116 | 0.121 | 0.524 |

| R1. Stopped being kind to somebody you care about because they offended you? | 0.282 | 0.144 | 0.544 | 0.529 |

| R2. Felt worried about not being recognised after having acted in others’ interests? | 0.502 | 0.055 | 0.442 | 0.591 |

| R3. Felt regret after having given a gift? | 0.128 | 0.216 | 0.505 | 0.441 |

| R4. Stopped helping others because it was causing discomfort or inconvenience? | 0.070 | 0.062 | 0.436 | 0.294 |

| Measure | OAS-24 | OAS-12 | TOSCA-3 -SS | RSES | MAAS | GQ-6 | SOP-MPS |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OAS-24 | 1 | 0.927 | 0.475 | −0.513 | −0.449 | −0.294 | 0.4 |

| OAS-12 | 0.927 | 1 | 0.501 | −0.53 | −0.434 | −0.271 | 0.402 |

| TOSCA-3-SS | 0.475 | 0.501 | 1 | −0.551 | −0.406 | −0.218 | 0.37 |

| RSES | −0.513 | −0.53 | −0.551 | 1 | 0.397 | 0.444 | −0.284 |

| MAAS | −0.449 | −0.434 | −0.406 | 0.397 | 1 | 0.205 | −0.358 |

| GQ-6 | −0.294 | −0.271 | −0.218 | 0.444 | 0.205 | 1 | −0.092 |

| SOP-MPS | 0.4 | 0.402 | 0.37 | −0.284 | −0.358 | −0.092 | 1 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ducasse, D.; Leurent, M.; Picot, M.-C.; Aouinti, S.; Brand-Arpon, V.; Courtet, P.; Barrows, P.; Shonin, E.; Sapthiang, S.; Olié, E.; et al. French Translation and Validation of the Ontological Addiction Scale (OAS). Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2025, 22, 511. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22040511

Ducasse D, Leurent M, Picot M-C, Aouinti S, Brand-Arpon V, Courtet P, Barrows P, Shonin E, Sapthiang S, Olié E, et al. French Translation and Validation of the Ontological Addiction Scale (OAS). International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2025; 22(4):511. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22040511

Chicago/Turabian StyleDucasse, Déborah, Martin Leurent, Marie-Christine Picot, Safa Aouinti, Véronique Brand-Arpon, Philippe Courtet, Paul Barrows, Edo Shonin, Supakyada Sapthiang, Emilie Olié, and et al. 2025. "French Translation and Validation of the Ontological Addiction Scale (OAS)" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 22, no. 4: 511. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22040511

APA StyleDucasse, D., Leurent, M., Picot, M.-C., Aouinti, S., Brand-Arpon, V., Courtet, P., Barrows, P., Shonin, E., Sapthiang, S., Olié, E., & Van Gordon, W. (2025). French Translation and Validation of the Ontological Addiction Scale (OAS). International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 22(4), 511. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22040511