The Effects of Food Security on Academic Performance of University Students at a Hispanic-Serving Institution

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Setting

2.2. Procedure

2.3. Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Statistics

3.2. Model Results

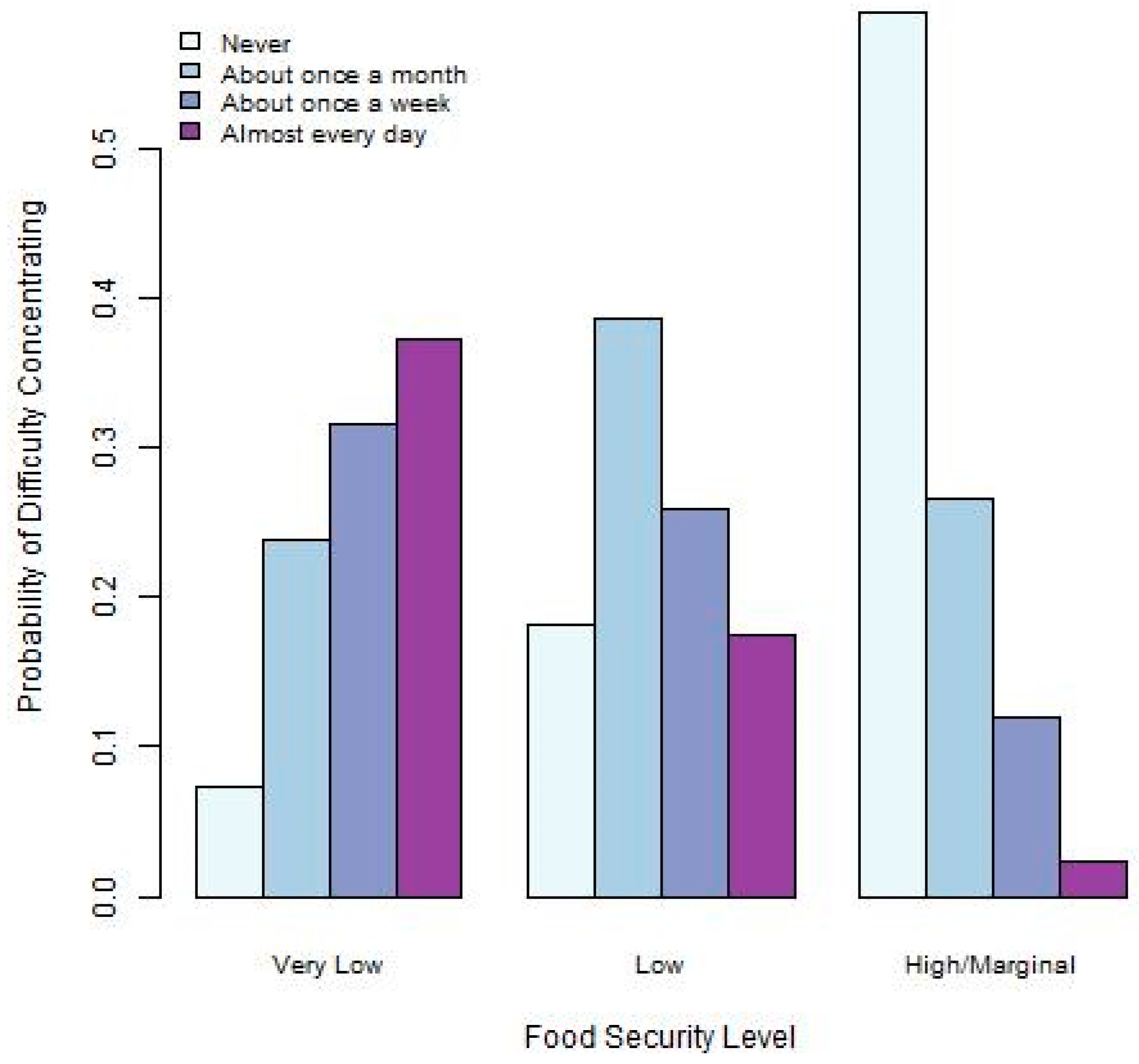

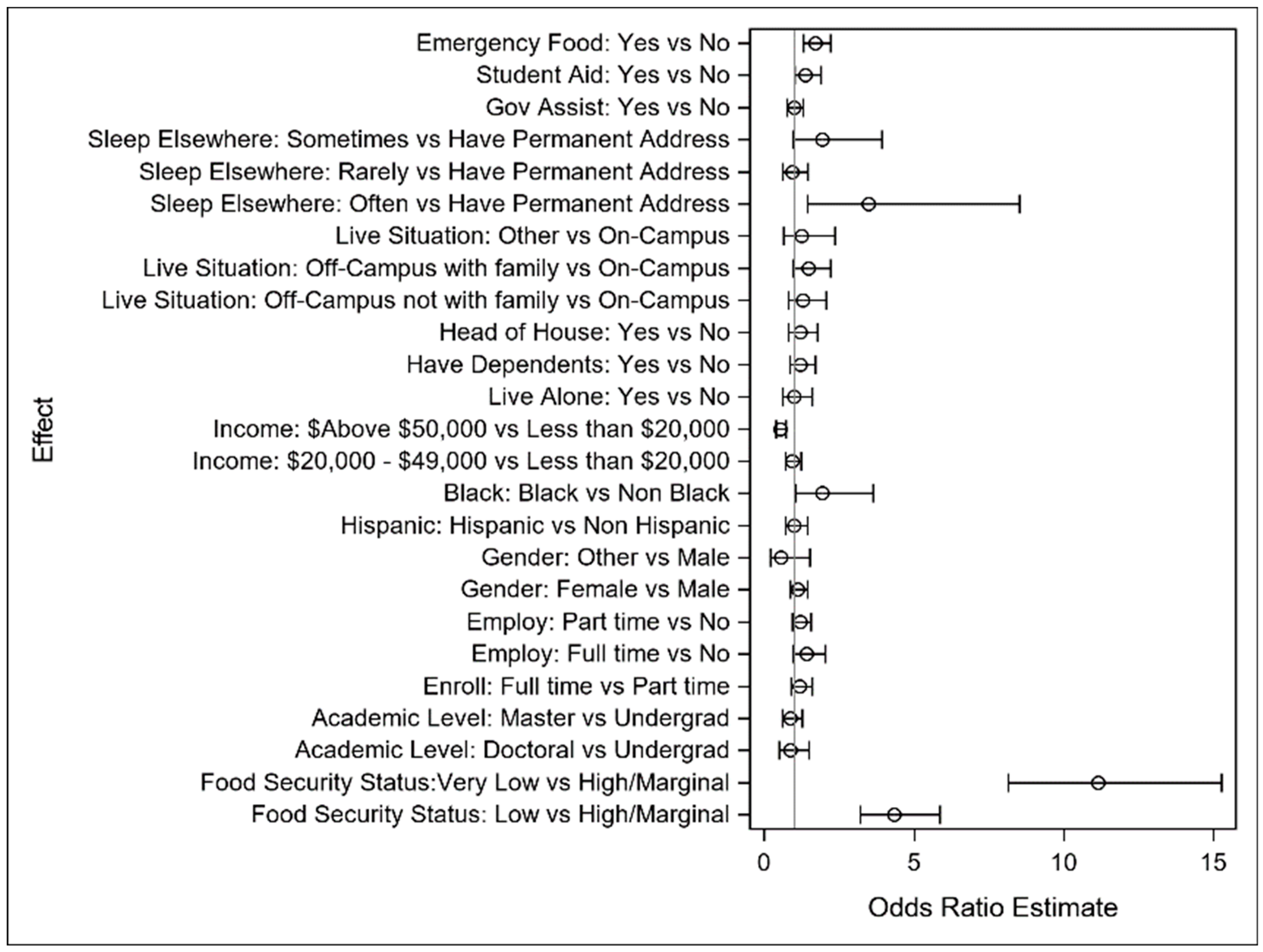

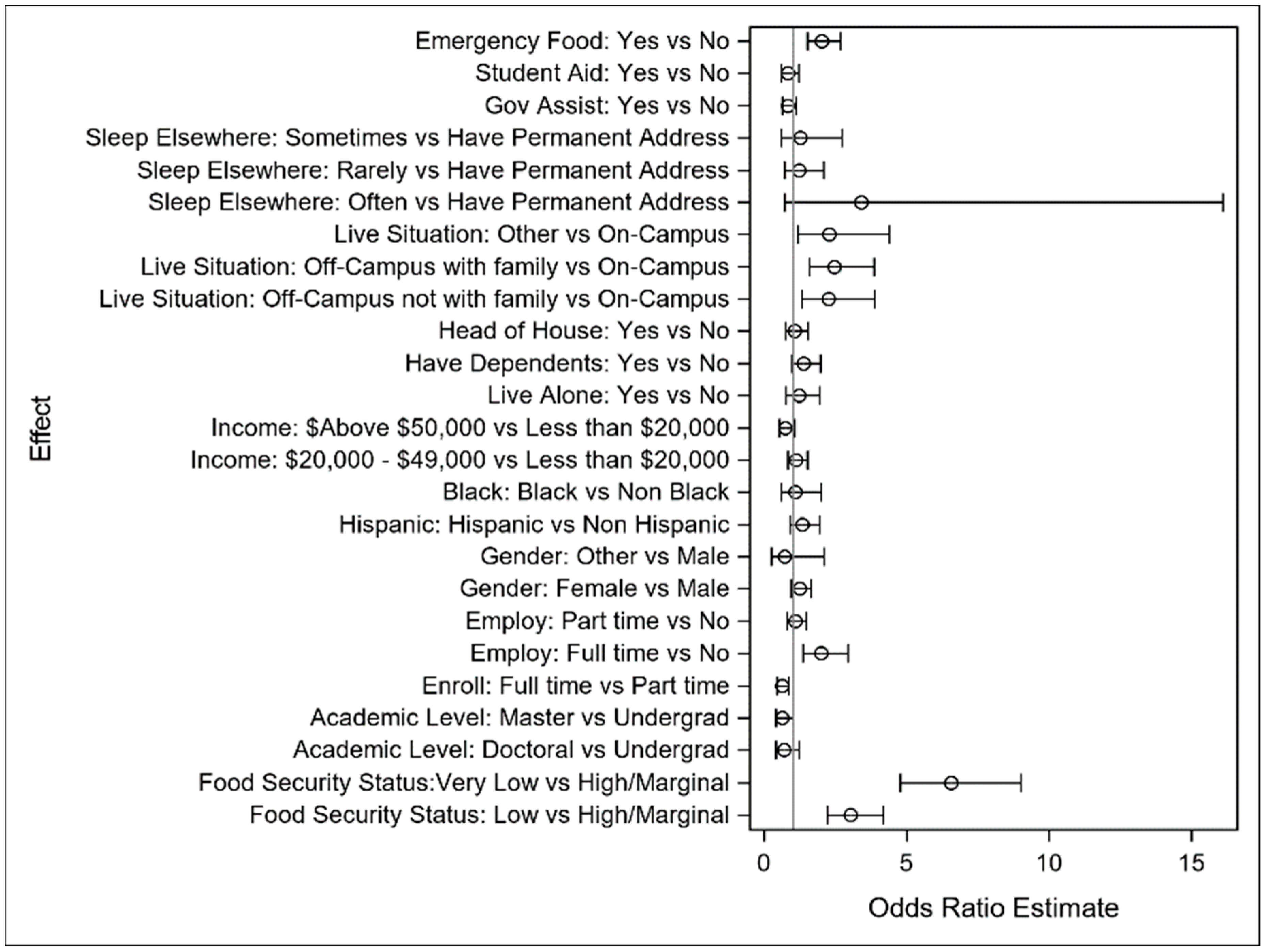

3.2.1. Difficulty Concentrating

- Black students were more likely to experience concentration challenges than non-black students (OR = 1.934, 95% CI [1.032, 3.627]);

- A higher income (above $50,000) was associated with a reduced likelihood of concentration problems (OR = 0.530, 95% CI [0.388, 0.725]);

- Students who did not have a stable residential space and often had to spend the night elsewhere seemed to have poorer concentration than students who had a permanent address (OR = 3.491, 95% CI [1.429, 8.527]);

- Students who received student aid or emergency food within the last 12 months had concentration problems more often than those who did not receive these (OR = 1.380, 95% CI [1.008, 1.889] and OR = 1.696, 95% CI [1.306, 2.202]).

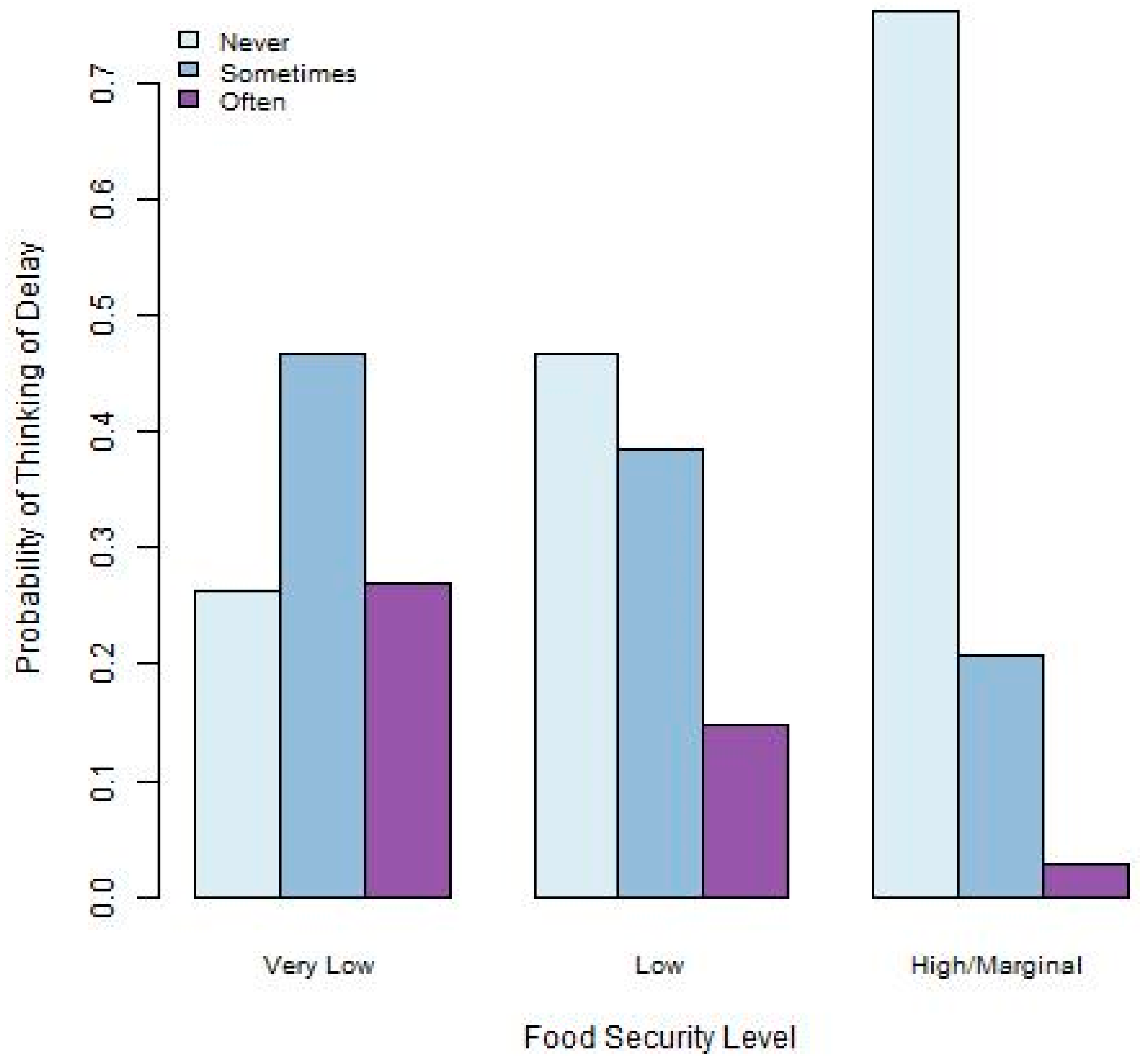

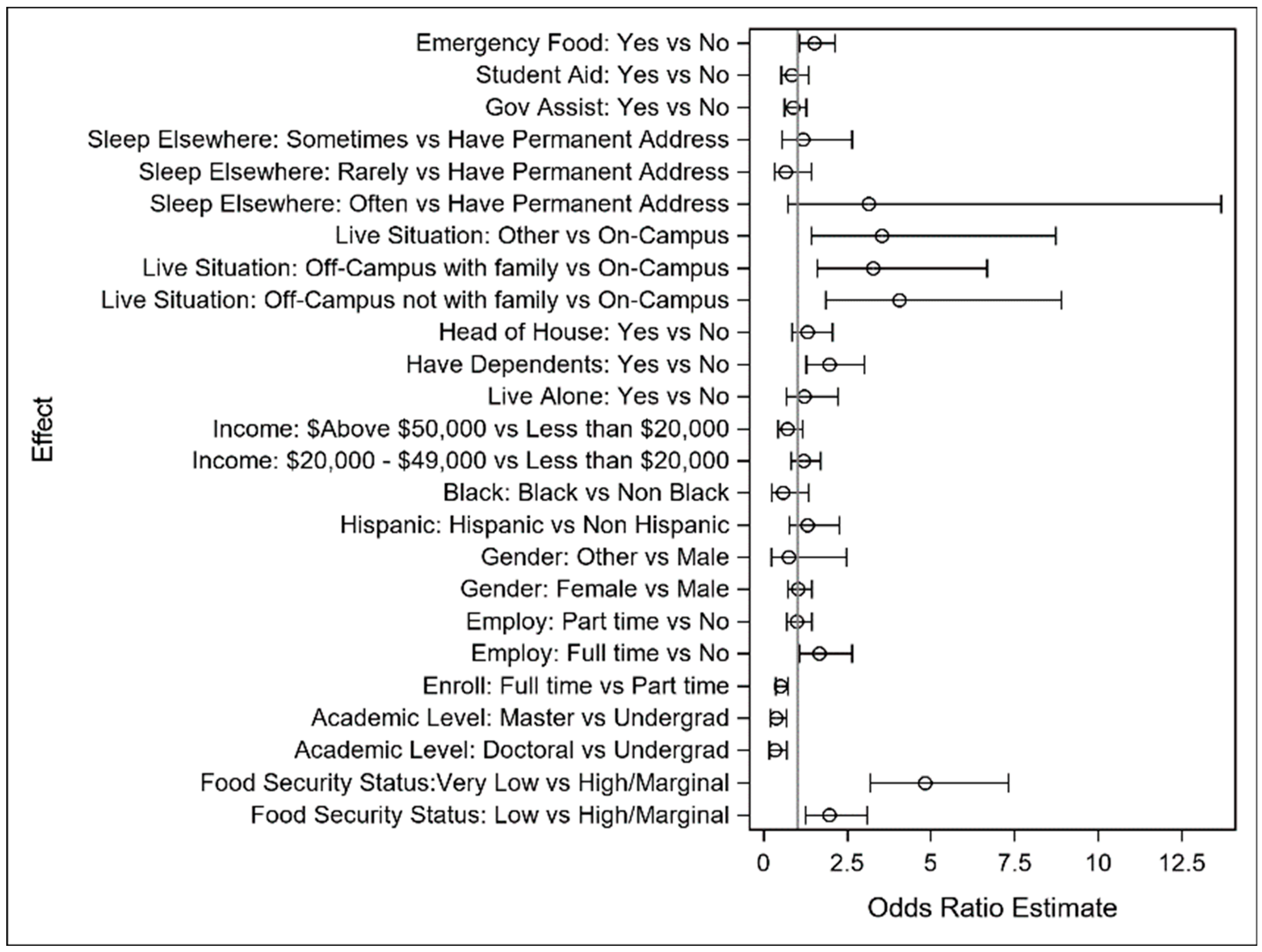

3.2.2. Thinking of Delay

- Students with full-time jobs were more likely to consider delaying their degree completion compared to students without employment (OR = 2.003, 95% CI [1.363, 2.944]);

- Students living on campus were more likely to stay on track with their degree completion;

- Students who received emergency food within the last 12 months thought about a delay more often than those who did not receive it (OR = 2.022, 95% CI [1.522, 2.685]).

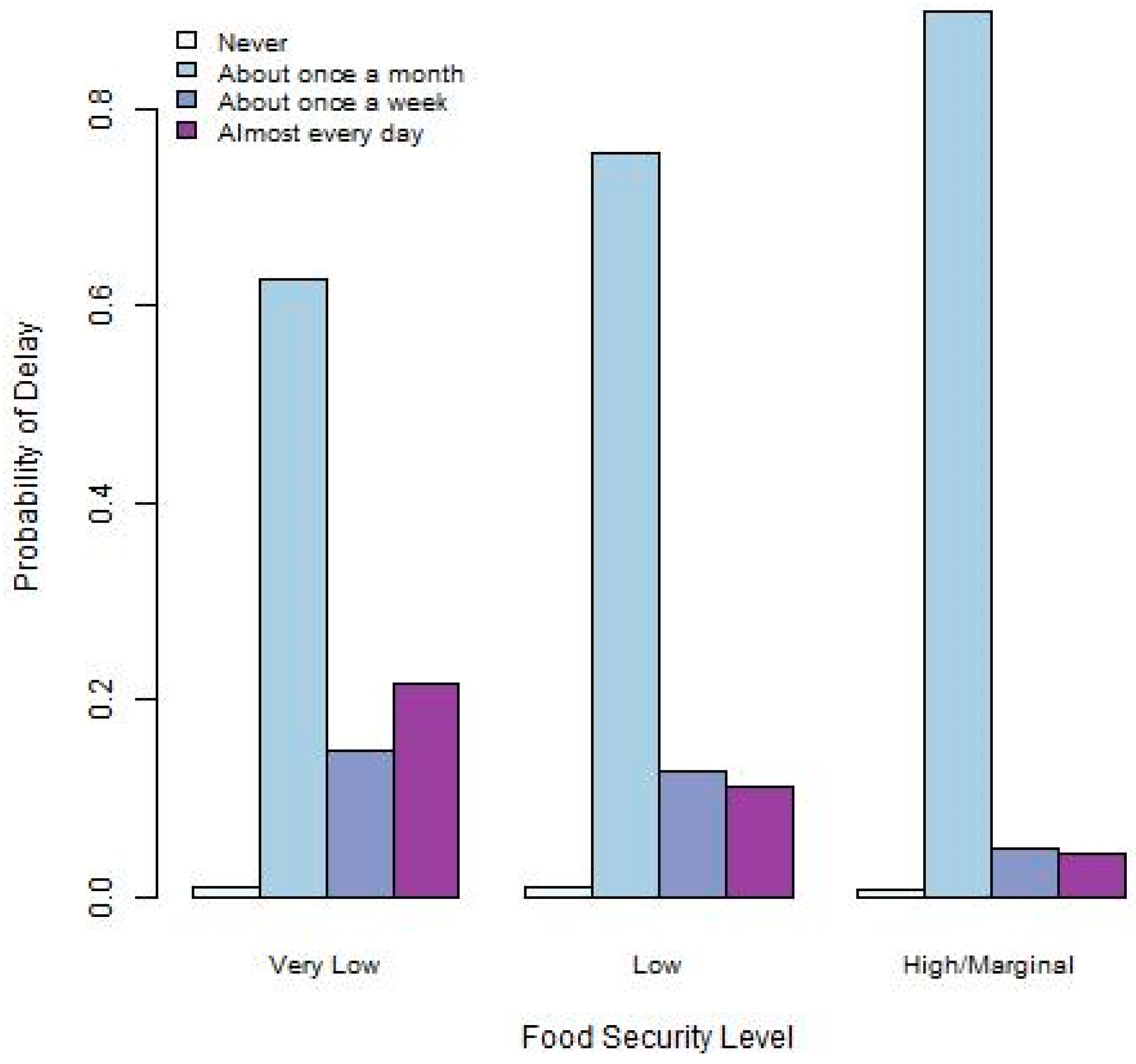

3.2.3. Degree Delay

- Doctoral and master’s students were less likely to delay degree completion compared to undergraduate students (OR = 0.332, 95% CI [0.162, 0.680] and OR = 0.362, 95% CI [0.199, 0.659]);

- Full-time enrollment decreased the odds of extending academic programs (OR = 0.499, 95% CI [0.346, 0.719]);

- Being full-time-employed increased the odds of extending academic programs (OR = 1.667, 95% CI [1.056, 2.631]);

- Having dependents increased the odds of delaying degree completion (OR = 1.954, 95% CI [1.268, 3.010]);

- Living on campus decreased the odds of delaying degree completion;

- Students who received emergency food within the last 12 months were more likely to delay than those who did not receive it (OR = 1.500, 95% CI [1.058, 2.127]).

4. Discussion

4.1. Broader Implications

4.2. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Food Security Status | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Very Low (N = 604) | Low (N = 452) | High/Marginal (N = 673) | Total (N = 1729) | p-Value | |

| Physical PROMIS Scale | <0.0001 1 | ||||

| n | 597 | 447 | 665 | 1709 | |

| Mean (SD) | 6.8 (1.63) | 7.2 (1.63) | 7.8 (1.53) | 7.3 (1.64) | |

| Median | 7.0 | 7.0 | 8.0 | 8.0 | |

| Range | 2.0, 10.0 | 2.0, 10.0 | 2.0, 10.0 | 2.0, 10.0 | |

| Mental PROMIS Scale | <0.0001 1 | ||||

| n | 597 | 447 | 665 | 1709 | |

| Mean (SD) | 5.3 (1.90) | 5.8 (1.89) | 6.3 (1.94) | 5.8 (1.96) | |

| Median | 5.0 | 6.0 | 6.0 | 6.0 | |

| Range | 2.0, 10.0 | 2.0, 10.0 | 2.0, 10.0 | 2.0, 10.0 | |

| UTEP Enrollment, n (%) | 0.6775 2 | ||||

| Full time | 519 (85.9%) | 380 (84.1%) | 576 (85.6%) | 1475 (85.3%) | |

| Part time | 85 (14.1%) | 72 (15.9%) | 97 (14.4%) | 254 (14.7%) | |

| Employed, n (%) | 0.4446 2 | ||||

| Full time | 124 (20.5%) | 79 (17.5%) | 132 (19.6%) | 335 (19.4%) | |

| Part time | 287 (47.5%) | 216 (47.8%) | 299 (44.4%) | 802 (46.4%) | |

| No | 193 (32.0%) | 157 (34.7%) | 242 (36.0%) | 592 (34.2%) | |

| Age Group, n (%) | <0.0001 2 | ||||

| Under 18 | 1 (0.5%) | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (0.4%) | 2 (0.4%) | |

| 18–24 | 120 (65.2%) | 96 (64.4%) | 180 (80.7%) | 396 (71.2%) | |

| 25–34 | 29 (15.8%) | 40 (26.8%) | 26 (11.7%) | 95 (17.1%) | |

| 35–44 | 16 (8.7%) | 3 (2.0%) | 9 (4.0%) | 28 (5.0%) | |

| 45–64 | 18 (9.8%) | 9 (6.0%) | 7 (3.1%) | 34 (6.1%) | |

| 65 and above | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (0.7%) | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (0.2%) | |

| Missing | 420 | 303 | 450 | 1173 | |

| Hispanic, n (%) | 0.1714 2 | ||||

| Non-Hispanic | 119 (19.7%) | 77 (17.0%) | 106 (15.8%) | 302 (17.5%) | |

| Hispanic | 485 (80.3%) | 375 (83.0%) | 567 (84.2%) | 1427 (82.5%) | |

| Black, n (%) | 0.0009 2 | ||||

| Non-Black | 563 (93.2%) | 434 (96.0%) | 656 (97.5%) | 1653 (95.6%) | |

| Black | 41 (6.8%) | 18 (4.0%) | 17 (2.5%) | 76 (4.4%) | |

| White, n (%) | 0.4245 2 | ||||

| Non-White | 514 (85.1%) | 381 (84.3%) | 555 (82.5%) | 1450 (83.9%) | |

| White | 90 (14.9%) | 71 (15.7%) | 118 (17.5%) | 279 (16.1%) | |

| Gender, n (%) | 0.2811 2 | ||||

| Female | 400 (66.2%) | 309 (68.4%) | 432 (64.2%) | 1141 (66.0%) | |

| Male | 187 (31.0%) | 132 (29.2%) | 230 (34.2%) | 549 (31.8%) | |

| Other | 17 (2.8%) | 11 (2.4%) | 11 (1.6%) | 39 (2.3%) | |

| Income in 2022, n (%) | <0.0001 2 | ||||

| Less than $20,000 | 281 (46.5%) | 180 (39.8%) | 181 (26.9%) | 642 (37.1%) | |

| $20,000–$49,000 | 232 (38.4%) | 182 (40.3%) | 237 (35.2%) | 651 (37.7%) | |

| $Above $50,000 | 91 (15.1%) | 90 (19.9%) | 255 (37.9%) | 436 (25.2%) | |

| Academic Level, n (%) | 0.8097 2 | ||||

| Undergrad | 465 (77.0%) | 361 (79.9%) | 531 (78.9%) | 1357 (78.5%) | |

| Master’s | 86 (14.2%) | 59 (13.1%) | 90 (13.4%) | 235 (13.6%) | |

| Doctoral | 53 (8.8%) | 32 (7.1%) | 52 (7.7%) | 137 (7.9%) | |

| Live Alone, n (%) | 0.0021 2 | ||||

| Yes | 85 (14.1%) | 59 (13.1%) | 55 (8.2%) | 199 (11.5%) | |

| No | 519 (85.9%) | 393 (86.9%) | 618 (91.8%) | 1530 (88.5%) | |

| Number of Dependents, n (%) | <0.0001 2 | ||||

| 1 | 52 (66.7%) | 53 (94.6%) | 54 (91.5%) | 159 (82.4%) | |

| 4 or more | 26 (33.3%) | 3 (5.4%) | 5 (8.5%) | 34 (17.6%) | |

| Missing | 526 | 396 | 614 | 1536 | |

| Head of Household, n (%) | <0.0001 2 | ||||

| Yes | 206 (34.1%) | 117 (25.9%) | 125 (18.6%) | 448 (25.9%) | |

| No | 398 (65.9%) | 335 (74.1%) | 548 (81.4%) | 1281 (74.1%) | |

| Living Situation, n (%) | <0.0001 2 | ||||

| On-Campus | 73 (12.1%) | 41 (9.1%) | 31 (4.6%) | 145 (8.4%) | |

| Off-Campus with family | 370 (61.3%) | 323 (71.5%) | 527 (78.3%) | 1220 (70.6%) | |

| Off-Campus not with family | 116 (19.2%) | 62 (13.7%) | 79 (11.7%) | 257 (14.9%) | |

| Other | 45 (7.5%) | 26 (5.8%) | 36 (5.3%) | 107 (6.2%) | |

| Sleeping Elsewhere, n (%) | <0.0001 2 | ||||

| Often | 12 (2.0%) | 5 (1.1%) | 2 (0.3%) | 19 (1.1%) | |

| Sometimes | 27 (4.5%) | 9 (2.0%) | 4 (0.6%) | 40 (2.3%) | |

| Rarely | 48 (8.0%) | 28 (6.2%) | 34 (5.1%) | 110 (6.4%) | |

| Have Permanent Address | 516 (85.6%) | 410 (90.7%) | 633 (94.1%) | 1559 (90.2%) | |

| Missing | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | |

| Government Assistance, n (%) | <0.0001 2 | ||||

| Yes | 255 (42.2%) | 178 (39.4%) | 206 (30.6%) | 639 (37.0%) | |

| No | 349 (57.8%) | 274 (60.6%) | 467 (69.4%) | 1090 (63.0%) | |

| Federal Student Aid, n (%) | 0.0007 2 | ||||

| Yes | 491 (81.3%) | 379 (83.8%) | 505 (75.0%) | 1375 (79.5%) | |

| No | 113 (18.7%) | 73 (16.2%) | 168 (25.0%) | 354 (20.5%) | |

| Emergency Food, n (%) | <0.0001 2 | ||||

| Yes | 284 (47.0%) | 168 (37.2%) | 101 (15.0%) | 553 (32.0%) | |

| No | 320 (53.0%) | 284 (62.8%) | 572 (85.0%) | 1176 (68.0%) | |

| Factor | Odds Ratio | 95% Confidence Limits | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Food Security: Low vs. High/Marginal | 4.342 | 3.219 | 5.858 |

| Food Security: Very Low vs. High/Marginal | 11.149 | 8.139 | 15.274 |

| Doctoral vs. Undergrad | 0.859 | 0.492 | 1.501 |

| Master’s vs. Undergrad | 0.867 | 0.594 | 1.265 |

| Work: Full time vs. Part time | 1.187 | 0.883 | 1.595 |

| Enrollment: Full time vs. No | 1.410 | 0.975 | 2.039 |

| Enrollment: Part time vs. No | 1.198 | 0.922 | 1.556 |

| Female vs. Male | 1.119 | 0.867 | 1.445 |

| Other vs. Male | 0.551 | 0.201 | 1.512 |

| Hispanic vs. Non-Hispanic | 1.001 | 0.700 | 1.432 |

| Black vs. Non-Black | 1.934 | 1.032 | 3.627 |

| Income: $20,000–$49,000 vs. <$20,000 | 0.936 | 0.711 | 1.233 |

| Income: >$50,000 vs. <$20,000 | 0.530 | 0.388 | 0.725 |

| Lives Alone | 1.001 | 0.626 | 1.601 |

| Has Dependents | 1.196 | 0.842 | 1.698 |

| Head of Household | 1.201 | 0.816 | 1.768 |

| Living Situation: Off-Campus not with family vs. On-Campus | 1.282 | 0.799 | 2.057 |

| Living Situation: Off-Campus with family vs. On-Campus | 1.470 | 0.983 | 2.198 |

| Living: Situation: Other vs. On-Campus | 1.237 | 0.649 | 2.356 |

| Housing: Often vs. Have Permanent Address | 3.491 | 1.429 | 8.527 |

| Housing: Rarely vs. Have Permanent Address | 0.941 | 0.609 | 1.455 |

| Housing: Sometimes vs. Have Permanent Address | 1.931 | 0.953 | 3.916 |

| Government Assistance | 0.989 | 0.762 | 1.283 |

| Student Aid | 1.380 | 1.008 | 1.889 |

| Emergency Food | 1.696 | 1.306 | 2.202 |

| Factor | Odds Ratio | 95% Confidence Limits | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Food Security: Low vs. High/Marginal | 3.041 | 2.210 | 4.185 |

| Food Security: Very Low vs. High/Marginal | 6.560 | 4.779 | 9.006 |

| Doctoral vs. Undergrad | 0.697 | 0.400 | 1.214 |

| Master’s vs. Undergrad | 0.636 | 0.404 | 1.001 |

| Work: Full time vs. Part time | 0.623 | 0.452 | 0.860 |

| Enrollment: Full time vs. No | 2.003 | 1.363 | 2.944 |

| Enrollment: Part time vs. No | 1.089 | 0.810 | 1.464 |

| Female vs. Male | 1.242 | 0.943 | 1.637 |

| Other vs. Male | 0.722 | 0.247 | 2.113 |

| Hispanic vs. Non-Hispanic | 1.334 | 0.907 | 1.962 |

| Black vs. Non-Black | 1.085 | 0.588 | 2.002 |

| Income: $20,000–$49,000 vs. <$20,000 | 1.124 | 0.838 | 1.508 |

| Income: >$50,000 vs. <$20,000 | 0.737 | 0.514 | 1.057 |

| Lives Alone | 1.225 | 0.767 | 1.957 |

| Has Dependents | 1.389 | 0.983 | 1.964 |

| Head of Household | 1.073 | 0.747 | 1.541 |

| Living Situation: Off-Campus not with family vs. On-Campus | 2.262 | 1.319 | 3.877 |

| Living Situation: Off-Campus with family vs. On-Campus | 2.467 | 1.580 | 3.850 |

| Living: Situation: Other vs. On-Campus | 2.273 | 1.180 | 4.378 |

| Housing: Often vs. Have Permanent Address | 3.416 | 0.725 | 16.094 |

| Housing: Rarely vs. Have Permanent Address | 1.226 | 0.723 | 2.081 |

| Housing: Sometimes vs. Have Permanent Address | 1.262 | 0.584 | 2.729 |

| Government Assistance | 0.830 | 0.624 | 1.105 |

| Student Aid | 0.838 | 0.587 | 1.194 |

| Emergency Food | 2.022 | 1.522 | 2.685 |

| Factor | Odds Ratio | 95% Confidence Limits | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Food Security: Low vs. High/Marginal | 1.954 | 1.238 | 3.084 |

| Food Security: Very Low vs. High/Marginal | 4.820 | 3.175 | 7.319 |

| Doctoral vs. Undergrad | 0.332 | 0.162 | 0.680 |

| Master’s vs. Undergrad | 0.362 | 0.199 | 0.659 |

| Work: Full time vs. Part time | 0.499 | 0.346 | 0.719 |

| Enrollment: Full time vs. No | 1.667 | 1.056 | 2.631 |

| Enrollment: Part time vs. No | 0.989 | 0.679 | 1.439 |

| Female vs. Male | 1.021 | 0.727 | 1.435 |

| Other vs. Male | 0.736 | 0.220 | 2.462 |

| Hispanic vs. Non-Hispanic | 1.309 | 0.758 | 2.259 |

| Black vs. Non-Black | 0.572 | 0.244 | 1.340 |

| Income: $20,000–$49,000 vs. <$20,000 | 1.184 | 0.824 | 1.703 |

| Income: >$50,000 vs. <$20,000 | 0.697 | 0.425 | 1.146 |

| Lives Alone | 1.208 | 0.659 | 2.212 |

| Has Dependents | 1.954 | 1.268 | 3.010 |

| Head of Household | 1.307 | 0.830 | 2.058 |

| Living Situation: Off-Campus not with family vs. On-Campus | 4.051 | 1.843 | 8.905 |

| Living Situation: Off-Campus with family vs. On-Campus | 3.268 | 1.599 | 6.681 |

| Living: Situation: Other vs. On-Campus | 3.523 | 1.422 | 8.728 |

| Housing: Often vs. Have Permanent Address | 3.136 | 0.719 | 13.678 |

| Housing: Rarely vs. Have Permanent Address | 0.655 | 0.304 | 1.411 |

| Housing: Sometimes vs. Have Permanent Address | 1.177 | 0.526 | 2.632 |

| Government Assistance | 0.874 | 0.606 | 1.261 |

| Student Aid | 0.826 | 0.509 | 1.342 |

| Emergency Food | 1.500 | 1.058 | 2.127 |

References

- Ahmed, T.; Ilieva, R.T.; Shane, J.; Reader, S.; Aleong, C.; Wong, H.Y.; Chu, C.; Brusche, D.; Jiang, K.; Lopez, D.; et al. A developing crisis in hunger: Food insecurity within 3 public colleges before and during the COVID-19 Pandemic. J. Hunger Environ. Nutr. 2023, 18, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, C.C.; Alleman, N.F. A private struggle at a private institution: Effects of student hunger on social and academic experiences. J. Coll. Stud. Dev. 2019, 60, 52–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruening, M.; Laska, M.N. Position of the Society for Nutrition Education and Behavior: Food and nutrition insecurity among college students. J. Nutr. Educ. Behav. 2023, 55, 699–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camelo, K.; Elliott, M. Food insecurity and academic achievement among college students at a public university in the United States. J. Coll. Stud. Dev. 2019, 60, 307–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeBate, R.; Himmelgreen, D.; Gupton, J.; Heuer, J.N. Food insecurity, well-being, and academic success among college students: Implications for post COVID-19 Pandemic programming. Ecol. Food Nutr. 2021, 60, 564–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duke, N.N.; Campbell, S.D.; Sauls, D.L.; Stout, R.; Story, M.T.; Austin, T.; Bosworth, H.B.; Skinner, A.C.; Vilme, H. Prevalence of food insecurity among students attending four Historically Black Colleges and Universities. J. Am. Coll. Health 2023, 71, 87–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El Zein, A.; Shelnutt, K.P.; Colby, S.; Vilaro, M.J.; Zhou, W.; Greene, G.; Olfert, M.D.; Riggsbee, K.; Morrell, J.S.; Mathews, A.E. Prevalence and correlates of food insecurity among U.S. college students: A multi-institutional study. BMC Public Health 2019, 19, 660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goldman, B.J.; Freiria, C.N.; Landry, M.J.; Arikawa, A.Y.; Wright, L. Research trends and gaps concerning food insecurity in college students in the United States: A scoping review. J. Am. Coll. Health 2024, 1–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goldrick-Rab, S.; Baker-Smith, C.; Coca, V.; Looker, E.; Williams, T. College and University Basic Needs Insecurity: A National #RealCollege Survey Report. The Hope Center. 2019. Available online: https://hope.temple.edu/research/hope-center-basic-needs-survey (accessed on 8 November 2024).

- Hagedorn, R.L.; McArthur, L.H.; Hood, L.B.; Berner, M.; Anderson Steeves, E.T.; Connell, C.L.; Wall-Bassett, E.; Spence, M.; Toyin Babatunde, O.; Brooke Kelly, E.; et al. Expenditure, coping, and academic behaviors among food-insecure college students at 10 higher education institutes in the Appalachian and Southeastern Regions. Curr. Dev. Nutr. 2019, 3, nzz058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammad, N.M.; Leung, C.W. Food insecurity among graduate students and postdoctoral trainees. JAMA Netw. Open 2024, 7, e2356894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hickey, A.; Shields, D.; Henning, M. Perceived hunger in college students related to academic and athletic performance. Educ. Sci. 2019, 9, 242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilieva, R.T.; Ahmed, T.; Yan, A. Hungry minds: Investigating the food insecurity of minority community college students. J. Public Aff. 2019, 19, e1891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leung, C.W.; Farooqui, S.; Wolfson, J.A.; Cohen, A.J. Understanding the cumulative burden of basic needs insecurities: Associations with health and academic achievement among college students. Am. J. Health Promot. 2021, 35, 275–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loofbourrow, B.M.; Scherr, R.E. Food insecurity in higher education: A contemporary review of impacts and explorations of solutions. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 5884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maroto, M.E.; Snelling, A.; Linck, H. Food insecurity among community college students: Prevalence and association with grade point average. Community Coll. J. Res. Pract. 2015, 39, 515–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez, S.M.; Frongillo, E.A.; Leung, C.; Ritchie, L. No food for thought: Food insecurity is related to poor mental health and lower academic performance among students in California’s public university system. J. Health Psychol. 2020, 25, 1930–1939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meza, A.; Altman, E.; Martinez, S.; Leung, C.W. “It’s a feeling that one is not worth food”: A qualitative study exploring the psychosocial experience and academic consequences of food insecurity among college students. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet. 2019, 119, 1713–1721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moya, E.M.; Wagler, A.; Ayala, J.; Crouse, M.; Garcia, A.; Schober, G.S. Analysis of food and housing insecurity among university students at a public Hispanic-serving institution. J. Hunger Environ. Nutr. 2023, 18, 21–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nazmi, A.; Martinez, S.; Byrd, A.; Robinson, D.; Bianco, S.; Maguire, J.; Crutchfield, R.M.; Condron, K.; Ritchie, L. A systematic review of food insecurity among US students in higher education. J. Hunger Environ. Nutr. 2019, 14, 725–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikolaus, C.J.; An, R.; Ellison, B.; Nickols-Richardson, S.M. Food insecurity among college students in the United States: A scoping review. Adv. Nutr. 2020, 11, 327–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olfert, M.D.; Hagedorn-Hatfield, R.L.; Houghtaling, B.; Esquivel, M.K.; Hood, L.B.; MacNell, L.; Soldavini, J.; Berner, M.; Savoie Roskos, M.R.; Hingle, M.D.; et al. Struggling with the basics: Food and housing insecurity among college students across twenty-two colleges and universities. J. Am. Coll. Health 2023, 71, 2518–2529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Neill, M.; Maguire, J. College students self-reported food insecurity and correlations with health and academic performance. J. Behav. Soc. Sci. 2017, 4, 34–40. [Google Scholar]

- Phillips, E.; McDaniel, A.; Croft, A. Food insecurity and academic disruption among college students. J. Stud. Aff. Res. Pract. 2018, 55, 353–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savoie-Roskos, M.R.; Harrison, C.; Coombs, C.; Hendrickson, J.; Hawes, R.; Barney, M.; Doxey, J.; LeBlanc, H. Food insecurity exists among college students at a midsized university in Utah. J. Hunger Environ. Nutr. 2023, 18, 36–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valle, I.; Quinteros, K.; Covarrubias, R. Security as servingness: Examining links between food insecurity and performance at a Hispanic-Serving Institution. J. Divers. High. Educ. 2025, 18, 49–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Woerden, I.; Hruschka, D.; Bruening, M. Food insecurity negatively impacts academic performance. J. Public Aff. 2019, 19, e1864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabbitt, M.P.; Hales, L.J.; Burke, M.P.; Coleman-Jensen, A. Household Food Security in the United States in 2022; (Report No. ERR-325); U.S. Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service: Washington, DC, USA, 2023.

- Wagler, A.; Schober, G.S.; Chavez-Baray, S.M.; Ayala, J.; Dessauer, P.R.; Moya, E.M. Food and housing security at a US Hispanic-Serving Institution: An examination before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. Front. Public Health 2022, 10, 918955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mechler, H.; Coakley, K.; Walsh-Dilley, M.; Cargas, S. Examining the relationship between food insecurity and academic performance: Implications for diversity and equity in higher education. J. Coll. Stud. Retent. Res. Theory Pract. 2024, 26, 3–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tin, J.J.; Williams, V.; Perryment, G.; Montano, S. Prevalence of food insecurity in a community college district: Relationship between food security and grade point average. Community Coll. J. Res. Pract. 2024, 48, 271–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banerjee, T.; Crews, D.C.; Wesson, D.E.; Dharmarajan, S.; Saran, R.; Burrows, N.R.; Saydah, S.; Powe, N.R. Food insecurity, CKD, and subsequent ESRD in US adults. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 2017, 70, 38–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laraia, B.A. Food insecurity and chronic disease. Adv. Nutr. 2013, 4, 203–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maynard, M.; Andrade, L.; Packull-McCormick, S.; Perlman, C.M.; Leos-Toro, C.; Kirkpatrick, S.I. Food insecurity and mental health among females in high-income countries. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 1424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thomas, M.M.C.; Miller, D.P.; Morrissey, T.W. Food insecurity and child health. Pediatrics 2019, 144, e20190397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haveman, R.; Smeeding, T. The role of higher education in social mobility. Future Child. 2006, 16, 125–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Terriquez, V. Trapped in the working class? Prospects for the intergenerational im(mobility) of Latino youth. Sociol. Inq. 2014, 84, 382–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blumberg, S.J.; Bialostosky, K.; Hamilton, W.L.; Briefel, R.R. The effectiveness of a short form of the Household Food Security Scale. Am. J. Public Health 1999, 89, 1231–1234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Izrael, D.; Hoaglin, D.; Battaglia, M. A SAS macro for balancing a weighted sample. In Proceedings of the SAS Users Group International (SUGI) Conference, Indianapolis, IN, USA, 9–12 April 2000; Available online: http://www2.sas.com/proceedings/sugi25/25/st/25p258.pdf (accessed on 31 January 2016).

- McCaffrey, D.F.; Griffin, B.A.; Almirall, D.; Slaughter, M.E.; Ramchand, R.; Burgette, L.F. A tutorial on propensity score estimation for multiple treatments using generalized boosted models. Stat. Med. 2013, 32, 3388–3414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- UnidosUS. Survey of Latinos in Higher Education: Unveiling Barriers, Celebrating Persistence, and Identifying Opportunities for Tomorrow; UnidosUS: Washington, DC, USA, 2024; Available online: https://unidosus.org/publications/latinos-and-higher-education-survey/ (accessed on 1 November 2024).

- Yu, R.; Haddock, A.; Womack, T. Integrating supports for students with wraparound. Contemp. Sch. Psychol. 2022, 26, 155–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Response | Description | Levels |

|---|---|---|

| Difficulty Concentrating | This variable assesses the frequency with which students experience poor concentration at school due to concerns about food, rent, or other necessities. |

|

| Thinking of Delay | This variable evaluates how often students think about delaying the completion of their degree due to a lack of money for essentials. |

|

| Delayed Degree | This variable shows whether students have delayed their degree because of financial constraints related to food, rent, or other necessities. |

|

| Frequency | Relative Frequency | |

|---|---|---|

| Very Low | 604 | 34.93 |

| Low | 452 | 26.14 |

| High/Marginal | 673 | 38.92 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Moya, E.M.; Schober, G.S.; Wagler, A.; Ayala-Demeo Brown, J.; Chavez-Baray, S.M.; Liang, P.; Kennebrew, R. The Effects of Food Security on Academic Performance of University Students at a Hispanic-Serving Institution. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2025, 22, 266. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22020266

Moya EM, Schober GS, Wagler A, Ayala-Demeo Brown J, Chavez-Baray SM, Liang P, Kennebrew R. The Effects of Food Security on Academic Performance of University Students at a Hispanic-Serving Institution. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2025; 22(2):266. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22020266

Chicago/Turabian StyleMoya, Eva M., Gregory S. Schober, Amy Wagler, Jessica Ayala-Demeo Brown, Silvia M. Chavez-Baray, Panfeng Liang, and Robbie Kennebrew. 2025. "The Effects of Food Security on Academic Performance of University Students at a Hispanic-Serving Institution" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 22, no. 2: 266. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22020266

APA StyleMoya, E. M., Schober, G. S., Wagler, A., Ayala-Demeo Brown, J., Chavez-Baray, S. M., Liang, P., & Kennebrew, R. (2025). The Effects of Food Security on Academic Performance of University Students at a Hispanic-Serving Institution. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 22(2), 266. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22020266