Conspiracy Theories, Psychological Distress, and Sympathy for Violent Radicalization in Young Adults during the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Cross-Sectional Study

Abstract

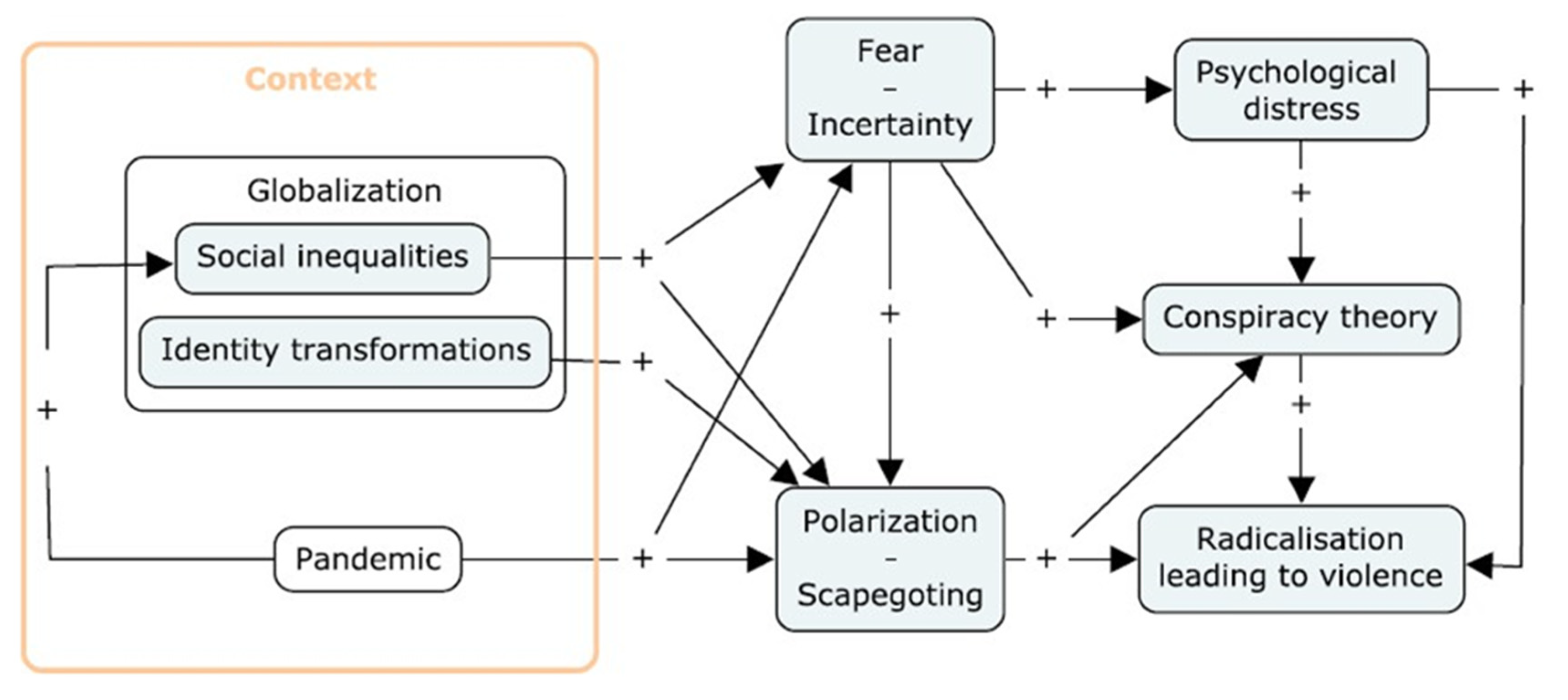

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Description of the Sample

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. Endorsement of Conspiracy Theories

2.2.2. Attitudes toward Violent Radicalization

2.2.3. Psychological Distress

2.2.4. Sociodemographic Variables

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

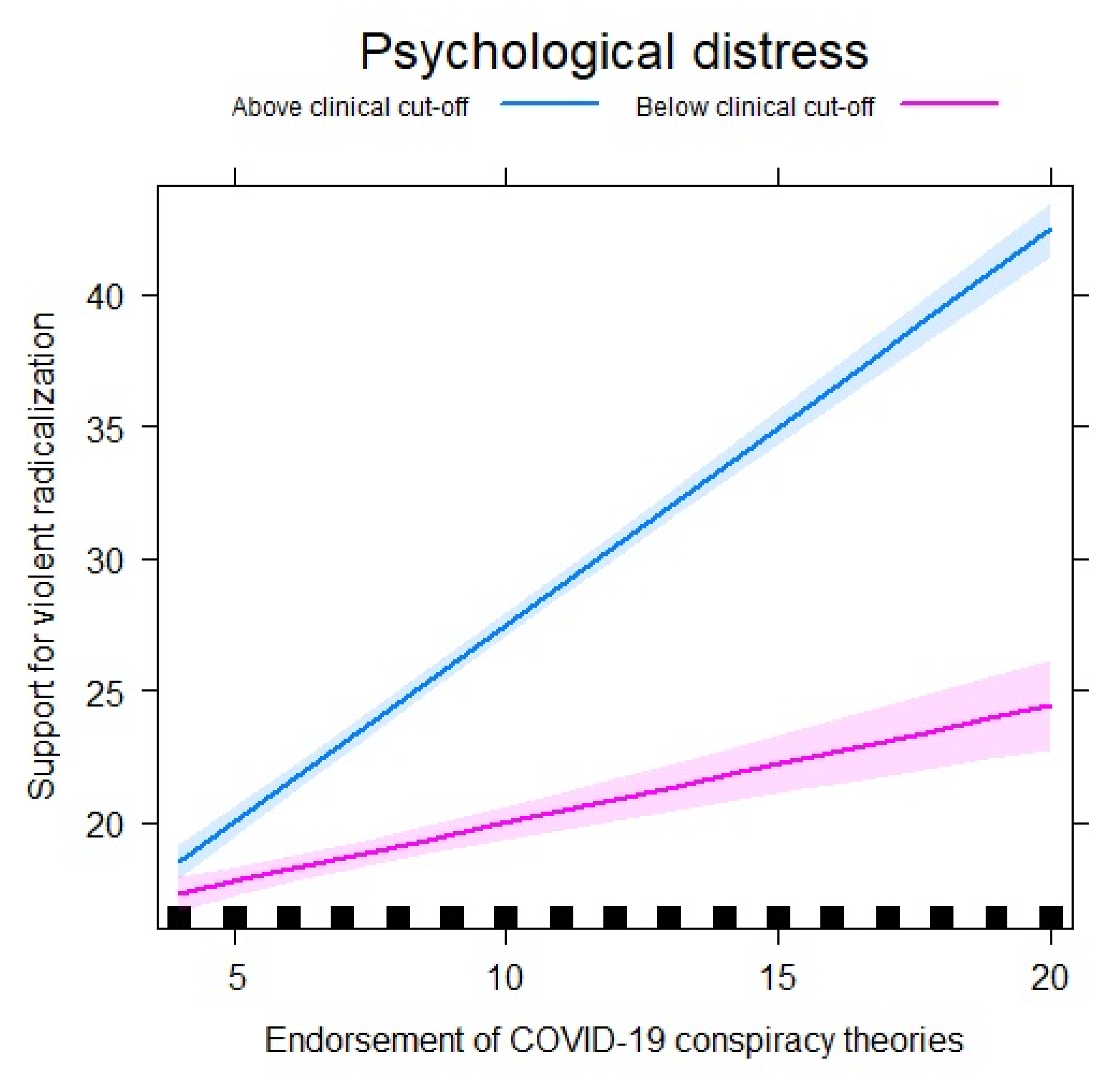

Moderation Analyses

4. Discussion

5. Limitations

6. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Schmid, A.P. Radicalisation, De-radicalisation, Counter-radicalisation: A Conceptual Discussion and Literature Review. ICCT Res. Pap. 2013, 97, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wynia, M.K.; Eisenman, D.; Hanfling, D. Ideologically Motivated Violence: A Public Health Approach to Prevention. Am. J. Public Health 2017, 107, 1244–1246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Fascist Threat. Available online: https://ajph.aphapublications.org/doi/full/10.2105/AJPH.2021.306169 (accessed on 2 February 2021).

- Krieger, N. Enough: COVID-19, Structural Racism, Police Brutality, Plutocracy, Climate Change—and Time for Health Justice, Democratic Governance, and an Equitable, Sustainable Future. Am. J. Public Health. 2020, 110, 1620–1623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozer, S. Globalization and radicalization: A cross-national study of local embeddedness and reactions to cultural globalization in regard to violent extremism. Int. J. Intercult. Relat. 2020, 76, 26–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marone, F. Hate in the time of coronavirus: Exploring the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on violent extremism and terrorism in the West. Secur. J. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macklin, G. Coronavirus and the Far Right: Seizing the Moment? Instituto per gli Studi di Politica Internazionale: Milano, Italy, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Marinthe, G.; Brown, G.; Delouvée, S.; Jolley, D. Looking out for myself: Exploring the relationship between conspiracy mentality, perceived personal risk, and COVID-19 prevention measures. Br. J. Health Psychol. 2020, 25, 957–980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Romer, D.; Jamieson, K.H. Conspiracy theories as barriers to controlling the spread of COVID-19 in the U.S. Soc. Sci. Med. 2020, 263, 113356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Earnshaw, V.A.; Eaton, L.; Kalichman, S.C.; Brousseau, N.M.; Hill, E.C.; Fox, A.B. COVID-19 conspiracy beliefs, health behaviors, and policy support. Transl. Behav. Med. 2020, 10, 850–856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rozbroj, T.; Lyons, A.; Lucke, J. Psychosocial and demographic characteristics relating to vaccine attitudes in Australia. Patient Educ. Couns. 2019, 102, 172–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jolley, D.; Paterson, J.L. Pylons ablaze: Examining the role of 5G COVID-19 conspiracy beliefs and support for violence. Br. J. Soc. Psychol. 2020, 59, 628–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antecedents and consequeneces of COVID-19 conspiracy theories: A rapid review of the evidence. Available online: https://psyarxiv.com/u8yah (accessed on 2 February 2021).

- Cénat, J.M.; Blais-Rochette, C.; Kokou-Kpolou, C.K.; Noorishad, P.-G.; Mukunzi, J.N.; McIntee, S.-E.; Dalexis, R.D.; Goulet, M.-A.; Labelle, P.R. Prevalence of symptoms of depression, anxiety, insomnia, posttraumatic stress disorder, and psychological distress among populations affected by the COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychiatry Res. 2021, 295, 113599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cénat, J.M.; Dalexis, R.D.; Kokou-Kpolou, C.K.; Mukunzi, J.N.; Rousseau, C. Social inequalities and collateral damages of the COVID-19 pandemic: When basic needs challenge mental health care. Int. J. Public Health 2020, 65, 717–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luna, S. Affective Atmospheres of Terror on the Mexico–U.S. Border: Rumors of Violence in Reynosa’s Prostitution Zone. Cult. Anthropol. 2018, 33, 58–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uscinski, J.E.; Enders, A.M.; Klofstad, C.A.; Seelig, M.I.; Funchion, J.R.; Everett, C.; Wuchty, S.; Premaratne, K.; Murthi, M.N. Why do people believe COVID-19 conspiracy theories? Harv. Kennedy Sch. MisInf. Rev. 2020, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Prooijen, J.-W.; Douglas, K.M. Conspiracy theories as part of history: The role of societal crisis situations. Mem. Stud. 2017, 10, 323–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miconi, D.; Oulhote, Y.; Hassan, G.; Rousseau, C. Sympathy for violent radicalization among college students in Quebec (Canada): The protective role of a positive future orientation. Psychol. Violence 2020, 10, 344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rousseau, C.; Hassan, G.; Miconi, D.; Lecompte, V.; Mekki-Berrada, A.; El Hage, H.; Oulhote, Y. From social adversity to sympathy for violent radicalization: The role of depression, religiosity and social support. Arch. Public Health 2019, 77, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Misiak, B.; Samochowiec, J.; Bhui, K.; Schouler-Ocak, M.; Demunter, H.; Kuey, L.; Raballo, A.; Gorwood, P.; Frydecka, D.; Dom, G. A systematic review on the relationship between mental health, radicalization and mass violence. Eur. Psychiatry 2019, 56, 51–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Freeman, D.; Waite, F.; Rosebrock, L.; Petit, A.; Causier, C.; East, A.; Jenner, L.; Teale, A.-L.; Carr, L.; Mulhall, S.; et al. Coronavirus conspiracy beliefs, mistrust, and compliance with government guidelines in England. Psychol. Med. 2020, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhui, K.; Warfa, N.; Jones, E. Is violent radicalisation associated with poverty, migration, poor self-reported health and common mental disorders? PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e90718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Frounfelker, R.L.; Frissen, T.; Miconi, D.; Lawson, J.; Brennan, R.T.; d’Haenens, L.; Rousseau, C. Transnational evaluation of the Sympathy for Violent Radicalization Scale: Mesuring population attitudes towards violent radicalization among young adults in two countries. Transcult. Psychiatry 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moskalenko, S.; McCauley, C. Measuring political mobilization: The distinction between activism and radicalism. Terror. Political Violence 2009, 21, 239–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mollica, R.F.; Caspi-Yavin, Y.; Bollini, P.; Truong, T.; Tor, S.; Lavelle, J. The Harvard trauma questionnaire: Validating a cross-cultural instrument for measuring torture, trauma, and post-traumatic stress disorder in Indochinese refugees. J. Nerv. Ment. Dis. 1992, 180, 111–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moum, T. Mode of administration and interviewer effects in self-reported symptoms of anxiety and depression. Soc. Indic. Res. 1998, 45, 279–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Buuren, S.; Groothuis-Oudshoorn, K. mice: Multivariate Imputation by Chained Equations in R. J. Stat. Softw. 2011, 45, 1–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tessler, H.; Choi, M.; Kao, G. The anxiety of being Asian American: Hate crimes and negative biases during the COVID-19 pandemic. Am. J. Crim. Justice 2020, 45, 636–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Emmelkamp, J.; Asscher, J.J.; Wissink, I.B.; Stams, G.J.J.M. Risk factors for (violent) radicalization in juveniles: A multilevel meta-analysis. Aggress. Violent Behav. 2020, 55, 101489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Gelder, M.M.; Bretveld, R.W.; Roeleveld, N. Web-based questionnaires: The future in epidemiology? Am. J. Epidemiol. 2010, 172, 1292–1298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, K.B. Researching Internet-based populations: Advantages and disadvantages of online survey research, online questionnaire authoring software packages, and web survey services. J. Comput. Mediat. Commun. 2005, 10, JCMC1034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tworek, H.; Beacock, I.; Ojo, E. Democratic Health Communications during Covid-19: A RAPID Response; UBC Centre for the Study of Democratic Institutions: Vancouver, BC, Canada, 2020. [Google Scholar]

| Variable | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Self-reported gender | |

| Woman | 3292 (54.8%) |

| Man | 2646 (44.1%) |

| Gender-diverse | 30 (0.5%) |

| Missing | 35 (0.6%) |

| Psychological distress | |

| ≤1.75 | 2441 (40.7%) |

| >1.75 | 2974 (49.5%) |

| Missing | 588 (9.8%) |

| City | |

| Montreal | 2000 (33.3%) |

| Calgary | 1002 (16.7%) |

| Edmonton | 1000 (16.7%) |

| Toronto | 2001 (33.3%) |

| Financial problems | |

| Not at all | 1963 (32.70%) |

| A little | 2184 (36.4%) |

| Moderate | 896 (14.9%) |

| A lot | 769 (12.8%) |

| Missing | 191 (3.2%) |

| Education | |

| High school or less | 1267 (21.1%) |

| Apprenticeship, technical institute, trade or vocational school, college, CEGEP or other non-university certificate or diploma, | 1741 (29.0%) |

| University certificate, diploma or degree | 2892 (48.2%) |

| Missing | 103 (1.7%) |

| Immigration status | |

| First generation | 1454 (24.2%) |

| Second generation | 1577 (26.3%) |

| Third generation or more | 2872 (47.8%) |

| Missing | 100 (1.7%) |

| mean (SD) min, max, % missing | |

| Age | 26.72 (4.53) 18.00, 35.00, 0.0% |

| Psychological distress | 2.00 (.79) 1.00, 4.00, 9.8% |

| Endorsement of conspiracy theories | 8.78 (4.87) 4.00, 20.00, 7.7% |

| Sympathy for violent radicalisation (SyfoR) | 23.72 (13.86) 8.00, 56.00, 7.9% |

| Radicalism Intention Scale (RIS) | 13.87 (7.40) 4.00, 28.00, 9.3% |

| SyfoR, Total Score | Endorsement of COVID-19 Conspiracy Theories, Total Score | Psychological Distress, Mean Score | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Mean (SD) | p-Value | η2 | Mean (SD) | p-Value | η2 | Mean (SD) | p-Value | η2 |

| Self-reported gender | <0.0001 | 0.04 | <0.0001 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.002 | |||

| Woman | 21.29 (12.42) | 8.24 (4.49) | 2.00 (0.71) | ||||||

| Man | 26.62 (14.96) | 9.45 (5.23) | 1.99 (0.87) | ||||||

| Gender-diverse | 30.42 (10.19) | 6.21 (3.31) | 2.43 (0.74) | ||||||

| Age | <0.0001 | 0.01 | <0.0001 | 0.004 | <0.0001 | 0.02 | |||

| 18–25 | 25.81 (13.84) | 9.17 (4.92) | 2.15 (0.82) | ||||||

| 26–35 | 22.41 (13.72) | 8.53 (4.83) | 1.91 (0.75) | ||||||

| City of residence | <0.0001 | 0.01 | <0.0001 | 0.03 | <0.0001 | 0.03 | |||

| Calgary | 23.66 (12.80) | 8.32 (4.57) | 1.90 (0.73) | ||||||

| Edmonton | 24.77 (13.62) | 8.90 (4.96) | 2.05 (0.82) | ||||||

| Montreal | 25.11 (15.91) | 9.90 (5.31) | 2.16 (0.87) | ||||||

| Toronto | 21.77 (11.86) | 7.80 (4.23) | 1.86 (0.68) | ||||||

| Financial problems | <0.0001 | 0.10 | <0.0001 | 0.13 | <0.0001 | 0.25 | |||

| Not at all | 19.51 (11.14) | 7.16 (3.89) | 1.61 (0.58) | ||||||

| A little | 22.67 (12.56) | 8.26 (4.32) | 1.95 (0.66) | ||||||

| Moderate | 28.33 (14.64) | 10.38 (5.05) | 2.37 (0.78) | ||||||

| A lot | 32.46 (17.20) | 12.47 (5.86) | 2.78 (0.86) | ||||||

| Education | <0.0001 | 0.02 | <0.0001 | 0.06 | <0.0001 | 0.05 | |||

| High school or less | 23.89 (12.26) | 8.95 (4.56) | 2.08 (0.76) | ||||||

| Apprenticeship, technical institute, trade or vocational school, college, CEGEP or other non-university certificate or diploma | 26.80 (15.68) | 10.46 (5.26) | 2.23 (0.88) | ||||||

| University certificate, diploma or degree | 21.78 (13.02) | 7.69 (4.47) | 1.84 (0.70) | ||||||

| Immigrant status | <0.0001 | 0.02 | <0.0001 | 0.01 | <0.0001 | 0.04 | |||

| First generation | 21.03 (12.48) | 8.44 (4.30) | 1.80 (0.66) | ||||||

| Second generation | 23.21 (12.13) | 8.16 (4.48) | 1.91 (0.72) | ||||||

| Third generation or more | 25.36 (15.11) | 9.27 (5.28) | 2.15 (0.85) | ||||||

| β | 95% CI | p-Value | β | 95% CI | p-Value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | 6.68 | 4.45 | 8.91 | <0.0001 | 17.6 | 14.45 | 20.74 | <0.0001 |

| Endorsement of COVID-19 consp. theories | 0.88 | 0.80 | 0.96 | <0.0001 | −0.21 | −0.42 | 0.01 | 0.06 |

| Psychological distress (mean score) | 6.32 | 5.77 | 6.86 | <0.0001 | 1.10 | 0.12 | 2.08 | 0.03 |

| Self-reported gender (ref = woman) | ||||||||

| Man | 4.38 | 3.74 | 5.02 | <0.0001 | 3.66 | 2.98 | 4.35 | <0.0001 |

| Gender-diverse | 7.45 | 3.06 | 11.84 | 0.01 | 7.98 | 3.63 | 12.33 | 0.0004 |

| Age | −0.29 | −0.36 | −0.22 | <0.0001 | −0.29 | −0.36 | −0.22 | <0.0001 |

| City (ref = Montreal) | ||||||||

| Calgary | 2.18 | 1.27 | 3.09 | <0.0001 | 2.55 | 1.63 | 3.47 | <0.0001 |

| Edmonton | 1.76 | 0.88 | 2.65 | 0.0001 | 2.03 | 1.17 | 2.90 | <0.0001 |

| Toronto | 1.39 | 0.65 | 2.14 | 0.0003 | 1.70 | 0.96 | 2.44 | <0.0001 |

| Financial problems (ref = Not at all) | ||||||||

| A little | 0.10 | −0.66 | 0.86 | 0.79 | 0.42 | −0.31 | 1.15 | 0.26 |

| Moderate | 0.93 | −0.05 | 1.90 | 0.06 | 1.21 | 0.24 | 2.17 | 0.01 |

| A lot | 0.39 | −0.82 | 1.61 | 0.52 | −0.33 | −1.56 | 0.90 | 0.59 |

| Education (ref = High school or less) | ||||||||

| Apprenticeship, Tech. school or vocational school, college, CEGEP or other non-university cert. or diploma | 1.55 | 0.71 | 2.39 | 0.0003 | 1.02 | 0.20 | 1.84 | 0.02 |

| University cert., diploma or degree | 2.18 | 1.38 | 2.98 | <0.0001 | 1.42 | 0.62 | 2.22 | 0.0005 |

| Immigration (ref = 3rd generation or more) | ||||||||

| 1st generation | −1.54 | −2.33 | −0.75 | 0.0002 | −1.23 | −2.00 | −0.45 | 0.002 |

| 2nd generation | −0.04 | −0.75 | 0.66 | 0.91 | 0.13 | −0.56 | 0.82 | 0.71 |

| Interaction Endorsement of COVID-19 consp. theories * Psychol. distress | 0.49 | 0.40 | 0.57 | <0.0001 | ||||

| Outcome | Moderator (Level) | Estimate | 95% CI | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SyfoR | Psychological distress (≤1.75) | 0.47 | 0.35–0.59 | <0.0001 |

| Psychological distress (>1.75) | 1.36 | 1.26–1.46 | <0.0001 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Levinsson, A.; Miconi, D.; Li, Z.; Frounfelker, R.L.; Rousseau, C. Conspiracy Theories, Psychological Distress, and Sympathy for Violent Radicalization in Young Adults during the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Cross-Sectional Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 7846. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18157846

Levinsson A, Miconi D, Li Z, Frounfelker RL, Rousseau C. Conspiracy Theories, Psychological Distress, and Sympathy for Violent Radicalization in Young Adults during the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Cross-Sectional Study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2021; 18(15):7846. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18157846

Chicago/Turabian StyleLevinsson, Anna, Diana Miconi, Zhiyin Li, Rochelle L. Frounfelker, and Cécile Rousseau. 2021. "Conspiracy Theories, Psychological Distress, and Sympathy for Violent Radicalization in Young Adults during the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Cross-Sectional Study" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18, no. 15: 7846. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18157846

APA StyleLevinsson, A., Miconi, D., Li, Z., Frounfelker, R. L., & Rousseau, C. (2021). Conspiracy Theories, Psychological Distress, and Sympathy for Violent Radicalization in Young Adults during the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Cross-Sectional Study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(15), 7846. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18157846