Exploring the Effects of Problematic Internet Use on Adolescent Sleep: A Systematic Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

Aim of This Study

2. Methods

2.1. Eligibility Criteria

2.2. Search Strategy

2.3. Data Extraction and Quality Evaluation

3. Results

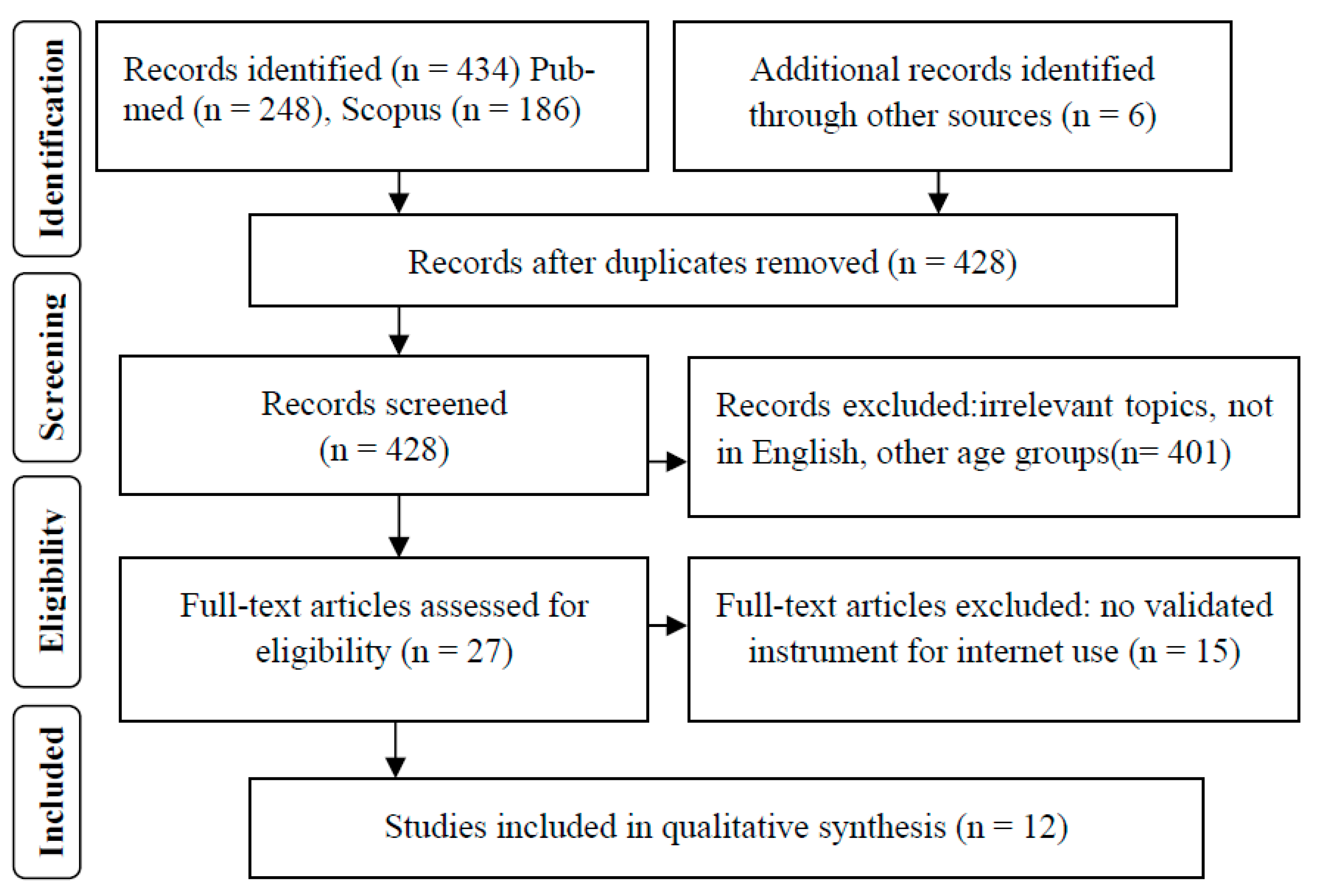

3.1. Study Selection and Basic Characteristics

3.2. Quality Evaluation

4. Discussion

4.1. Sleep Efficacy

4.2. Insomnia Symptoms

4.3. Use of Sleep Medication

4.4. The Role of Sex, Parental Characteristics, Purpose and Time of Use

4.5. Limitations of This Study

4.6. Clinical Importance and Recommendations for Future Research

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Tsitsika, A.; Janikian, M.; Schoenmakers, T.M.; Tzavela, E.C.; Ólafsson, K.; Wójcik, S.; Macarie, G.F.; Tzavara, C.; Richardson, C. Internet addictive behavior in adolescence: A cross-sectional study in seven European countries. Cyberpsychol. Behav. Soc. Netw. 2014, 17, 528–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tzavela, E.C.; Karakitsou, C.; Dreier, M.; Mavromati, F.; Wölfling, K.; Halapi, E.; Macarie, G.; Wójcik, S.; Veldhuis, L.; Tsitsika, A.K. Processes discriminating adaptive and maladaptive Internet use among European adolescents highly engaged online. J. Adolesc. 2015, 40, 34–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farsani, S.I.; Allahbakhshi, K.; Valipour, A.A.; Hafshejani, A.M. Some facts on problematic Internet use and sleep disturbance among adolescents. Iran. J. Public Health 2016, 45, 1531–1532. [Google Scholar]

- Shapira, N.A.; Lessig, M.C.; Goldsmith, T.D.; Szabo, S.T.; Lazoritz, M.; Gold, M.S.; Stein, D.J. Problematic internet use: Proposed classification and diagnostic criteria. Depress. Anxiety 2003, 17, 207–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grant, J.E.; Potenza, M.N.; Weinstein, A. Introduction to Behavioral Addictions. Am. J. Drug Alcohol Abuse 2010, 36, 233–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andreassen, C.G.; Griffiths, M.D.; Gjertsen, S.R.; Krossbakken, E.; Kvam, S.; Pallesen, S. The relationship between behavioral addictions and the five factor model of personality. J. Behav. Addict. 2013, 2, 90–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kennedy, K. Positive and Negative Effects of Social Media on Adolescent Well-Being. Master’s Thesis, Minnesota State University, Mankato, MN, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Akin, A.; Iskender, M. Internet addiction and depression, anxiety and stress. IOJES 2011, 3, 138–148. [Google Scholar]

- Bhandari, P.M.; Neupane, D.; Rijal, S.; Thapa, K.; Mishra, S.R.; Poudyal, A.K. Sleep quality, Internet addiction and depressive symptoms among undergraduate students in Nepal. BMC Psychiatry 2017, 17, 106–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ko, C.H.; Yen, J.Y.; Liu, S.C.; Huang, C.F.; Yen, C.F. The associations between aggressive behaviors and Internet addiction and online activities in adolescents. J. Adolesc. Health 2009, 44, 598–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam, S.S.; Hashim, N.H.; Ahmad, M.; Well, C.A.; Nor, S.M.; Omar, N.A. Negative and positive impact of Internet addiction on young adults: Empericial study in Malaysia. Intang. Cap. 2014, 10, 620–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashbrook, L.H.; Krystal, A.D.; Fu, Y.H.; Ptáček, L.J. Genetics of the human circadian clock and sleep homeostat. Neuropsychopharmacology 2020, 45, 45–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brand, S.; Kirov, R. Sleep and its importance in adolescence and in common adolescent somatic and psychiatric conditions. Int. J. Gen. Med. 2011, 4, 425–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siegel, J.M. Sleep viewed as a state of adaptive inactivity. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2010, 10, 747–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siegel, J.M. Clues to the functions of mammalian sleep. Nature 2005, 437, 1264–1271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krueger, J.M.; Rector, D.M.; Roy, S.; Van Dongen, H.P.; Belenky, G. Sleep as a fundamental property of neuronal assemblies. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2008, 9, 910–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, R.M.; Patrão, I.; Machado, M. Problematic internet use and feelings of loneliness. Int. J. Psychiatry Clin. Pract. 2019, 23, 160–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, M. Will online chat help alleviate mood loneliness? Cyberpsychol. Behav. 2009, 12, 219–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mei, S.; Yau, Y.H.; Chai, J.; Guo, J.; Potenza, M.N. Problematic Internet use, well-being, self-esteem and self-control: Data from a high-school survey in China. Addict. Behav. 2016, 61, 74–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Touitou, Y.; Touitou, D.; Reinberg, A. Disruption of adolescents’ circadian clock: The vicious circle of media use, exposure to light at night, sleep loss and risk behaviors. J. Physiol. Paris 2016, 110, 467–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LeBourgeois, M.K.; Hale, L.; Chang, A.M.; Akacem, L.D.; Montgomery-Downs, H.E.; Buxton, O.M. Digital media and sleep in childhood and adolescence. Pediatrics 2017, 140, 92–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.I.; Gau, S.S.-F. Sleep problems and internet addiction among children and adolescents: A longitudinal study. J. Sleep Res. 2016, 25, 458–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bruni, O.; Settel, S.; Fontanesi, L.; Baiocco, R.; Laghi, F.; Baumgartner, E. Technology Use and Sleep Quality in Preadolescence and Adolescence. J. Clin. Sleep Med. 2015, 11, 1433–1441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lam, L.T. Internet gaming addiction, problematic use of the internet, and sleep problems: A systematic review. Curr. Psychiatry Rep. 2014, 16, 444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alimoradi, Z.; Lin, C.Y.; Broström, A.; Bülow, P.H.; Bajalan, Z.; Griffiths, M.D.; Ohayon, M.M.; Pakpour, A.H. Internet addiction and sleep problems: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Sleep Med. Rev. 2019, 47, 51–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cain, N.; Gradisar, M. Electronic media use and sleep in school-aged children and adolescents: A review. Sleep Med. 2010, 11, 735–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moher, D.; Liberati, A.; Tetzlaff, J.; Altman, D.G. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009, 62, 1006–1012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodburn, E.A.; Ross, D.A.; Adolescent Health Programme. A Picture of Health? A Review and Annotated Bibliography of the Health of Young People in Developing Countries. World Health Organization. 1995. Available online: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/62500 (accessed on 15 December 2020).

- Hill, D.; Ameenuddin, N.; Chassiakos, Y.R.; Cross, C.; Radesky, J.; Hutchinson, J.; Boyd, R.; Mendelson, R.; Moreno, M.A.; Smith, J.; et al. Media use in school-aged children and adolescents. Pediatrics 2016, 138, 20162592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sleep Foundation. How Medications May Affect Sleep. Available online: https://www.sleepfoundation.org/articles/how-medications-may-affect-sleep (accessed on 19 December 2020).

- Downes, M.J.; Brennan, M.L.; Williams, H.C.; Dean, R.S. Development of a critical appraisal tool to assess the quality of cross-sectional studies (AXIS). BMJ Open 2016, 6, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juni, P.; Witschi, A.; Bloch, R.; Egger, M. The hazards of scoring the quality of clinical trials for meta-analysis. JAMA 1999, 282, 1054–1060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Surís, J.C.; Akre, C.; Piguet, C.; Ambresin, A.E.; Zimmermann, G.; Berchtold, A. Is internet use unhealthy? A cross-sectional study of adolescent internet overuse. Swiss Med. Wkly. 2014, 144, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canan, F.; Yildirim, O.; Sinani, G.; Ozturk, O.; Ustunel, T.Y. Internet addiction and sleep disturbance symptoms among Turkish high school students. Sleep Biol. Rhythms 2013, 11, 210–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekinci, Ö.; Çelik, T.; Savaş, N.; Toros, F. Association Between Internet Use and Sleep Problems in Adolescents. Arch. Neuropsychiatry 2014, 51, 122–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, K.; Son, H.; Park, M.; Han, J.; Kim, K.; Lee, B.; Gwak, H. Internet overuse and excessive daytime sleepiness in adolescents. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 2009, 63, 455–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kawabe, K.; Horiuchi, F.; Oka, Y.; Ueno, S.I. Association between sleep habits and problems and internet addiction in adolescents. Psychiatry Investig. 2019, 16, 581–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çelebioğlu, A.; Aytekin, A.; Küçükoğlu, S.; Ayran, G. The effect of Internet addiction on sleep quality in adolescents. J. Child Adolesc. Psychiatr. Nurs. 2020, 33, 221–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nursalam, N.; Octavia, M.; Tristiana, R.D.; Efendi, F. Association between insomnia and social network site use in Indonesian adolescents. Nurs. Forum 2019, 54, 149–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, Y.; Chen, Y.; Lu, Y.; Li, L. Exploring Associations between Problematic Internet Use, Depressive Symptoms and Sleep Disturbance among Southern Chinese Adolescents. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2016, 13, 313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.Y.; Kim, M.S.; Park, B.; Kim, J.H.; Choi, H.G. Lack of sleep is associated with internet use for leisure. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0191713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, P.H.; Lee, Y.C.; Chen, K.L.; Hsieh, P.L.; Yang, S.Y.; Lin, Y.L. The relationship between sleep quality and internet addiction among female college students. Front. Neurosci. 2019, 13, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koças, F.; Şaşmaz, T. Internet addiction increases poor sleep quality amongst high school students. Türkiye Halk Sağlığı Dergisi 2018, 16, 167–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Guo, Y.; Du, X.; Jiang, Y.; Wang, W.; Xiao, D.; Wang, T.; Lu, C.; Guo, L. Association between problematic internet use and sleep disturbance among adolescents: The role of the child’s sex. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 2682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, S.Y.; Chen, K.L.; Lin, P.H.; Wang, P.Y. Relationships among health-related behaviors, smart phone dependence, and sleep duration in female junior college students. Soc. Health Behav. 2019, 14, e0214769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goel, N.; Basner, M.; Rao, H.; Dinges, D.F. Circadian rhythms, sleep deprivation, and human performance. Prog. Mol. Biol. Transl. Sci. 2013, 119, 155–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crowley, S.J.; Acebo, C.; Carskadon, M.A. Sleep, circadian rhythms, and delayed phase in adolescence. Sleep Med. 2007, 8, 602–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duffy, J.F.; Cziesler, C.A. Effect of Light on Human Circadian Physiology. Sleep Med. Clin. 2013, 4, 165–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rajaratnam, S.M.W.; Middleton, B.; Stone, B.M.; Arendt, J.; Dijk, D.J. Melatonin advances the circadian timing of EEG sleep and directly facilitates sleep without altering its duration in extended sleep opportunities in humans. J. Physiol. 2004, 561, 339–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wolfson, A.R.; Carskadon, M.A. Understanding adolescent’s sleep patterns and school performance: A critical appraisal. Sleep Med. Rev. 2003, 7, 491–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.J.; Cho, S.J.; Cho, I.H.; Kim, S.J. Insufficient sleep and suicidality in adolescents. Sleep 2012, 35, 455–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donskoy, I.; Loghmanee, D. Insomnia in Adolescence. Med. Sci. 2018, 6, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dewald, J.F.; Meijer, A.M.; Oort, F.J.; Kerkhof, G.A.; Bögels, S.M. The influence of sleep quality, sleep duration and sleepiness on school performance in children and adolescents: A meta-analytic review. Sleep Med. Rev. 2010, 14, 179–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gujar, N.; Yoo, S.S.; Hu, P.; Walker, M.P. Sleep deprivation amplifies reactivity of brain reward networks, biasing the appraisal of positive emotional experiences. J. Neurosci. 2011, 31, 4466–4474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, H.; Hu, R.; Du, H.; Fiona, B.; Zhong, J.; Yu, M. The relationship between sleep duration and obesity risk among school students: A cross-sectional study in Zhejiang, China. Nutr. Metab. 2018, 15, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alfano, C.A.; Beidel, D.C.; Turner, S.M.; Lewin, D.S. Preliminary evidence for sleep complaints among children referred for anxiety. Sleep Med. 2006, 7, 467–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Machado-Duque, M.E.; Chabur, J.E.E.; Machado-Alba, J.E. Excessive Daytime Sleepiness, Poor Quality Sleep, and Low Academic Performance in Medical Students. Rev. Colomb. Psiquiatr. 2015, 44, 137–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navarro-Martínez, R.; Chover-Sierra, E.; Colomer-Pérez, N.; Vlachou, E.; Andriuseviciene, V.; Cauli, O. Sleep quality and its association with substance abuse among university students. Clin. Neurol. Neurosurg. 2020, 188, 105591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Zambotti, M.; Goldstone, A.; Colrain, I.M.; Baker, F.C. Insomnia disorder in adolescence: Diagnosis, impact, and treatment. Sleep Med. Rev. 2018, 39, 12–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Owens, J.; Adolescent Sleep Working Group; Committee on Adolescence. Insufficient sleep in adolescents and young adults: An update on causes and consequences. Pediatrics 2014, 134, e921–e932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez-Castroman, J.; Jaussent, I. Sleep Disturbances and Suicidal Behavior. Curr. Top. Behav. Neurosci. 2020, 46, 211–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chou, W.; Lee, K.; Ko, C.; Liu, L.; Hsiao, R.C.; Lin, H.; Yen, C.-F. Relationship between psychological inflexibility and experiential avoidance and internet addiction: Mediating effects of mental health problems. Psychiatry Res. 2017, 257, 40–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kodaira, K.; Silva, M.T. Sleeping pill use in Brazil: A population-based, cross-sectional study. BMJ Open 2017, 7, 016233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seney, M.L.; Sibille, E. Sex differences in mood disorders: Perspectives from humans and rodent models. Biol. Sex. Differ. 2014, 5, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krishnan, V.; Collop, N.A. Gender differences in sleep disorders. Curr. Opin. Pulm. Med. 2006, 12, 383–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dearing, E.; McCartney, K.; Taylor, B.A. Change in family income-to-needs matters more for children with less. Child Dev. 2001, 72, 1779–1793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, C.Y.; Kuo, F.Y. A study of Internet addiction through the lens of the interpersonal theory. Cyberpsychol. Behav. 2007, 10, 799–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Terms for Internet Use | And | Terms for Sleep |

|---|---|---|

| problematic internet use | sleep | |

| Or | Or | |

| internet addiction | sleep deprivation | |

| Or | Or | |

| internet use | sleep problems |

| Study Ref. #,Year, Origin | Participants Sample, Mean Age, Sex (Females) | Measurements on Internet Use | Measurements on Sleep | Main Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| [33] 2014, Switzerland | n = 3067, 14.23 years, 50.3% | Young’s IAT | Structured inquiry on sleep | PI users had at least 1 h less sleep that those who weren’t. PIU was higher in females. 80% of problematic internet users used it for leisure. |

| [34] 2013, Turkey | n = 1024, 16.04 years, 52.5% | Young’s IAT | Structured inquiry on sleep | PIU was associated with decreased sleep but only when used for leisure. PIU was higher for males. |

| [35] 2014, Turkey | n = 1212, 16 years, 52.6% | Young’s IAT | Semi-structured inquiry on sleep | PI users had higher frequencies of sleep problems (later bedtime, delayed sleep onset, night awakenings) |

| [36] 2009, South Korea | n = 2336, 16.7 years, 42.5% | Young’s IAT | ESS, structured inquiry on sleep problems | PI users slept significantly less than regular users. Increased sleeping problems among severe users (insomnia symptoms, snoring, teeth grinding, nightmares). Insomnia symptoms were higher in older adolescents |

| [37] 2019, Japan | n = 853, 13.6 years, 50.17% | Young’s IAT | CASC | Shorter sleep duration, later sleep onset (weekdays and weekends) and later sleep offset (weekends) for problematic users. |

| [38] 2020, Turkey | n = 1487, 16.16 years, 39.4% | Young’s IAT | PSQI | PIU negatively affects sleep quality. Weak but positive association with sleep duration–efficiency–latency and use of sleep medication. Using internet before bedtime was associated with higher PIU. |

| [39] 2018, Indonesia | n = 180, 17.0 years, 65% | SMSAQ | Insomnia questionnaire | Duration of use was significantly correlated with insomnia symptoms. High tolerance was the main reason of problematic use. |

| [40] 2016, China | n = 1661, 14.53 years, 48.2% | Young’s IAT | PSQI | PIU was associated with sleep disturbances. Higher level of father’s education was associated with PIU, but only for males. |

| [41] 2010, Korea | n = 853, 14.0 years, 55.2% | Korean Internet Addiction Scale | Structured inquiry on sleep | PIU was associated with irregular bedtime patterns and sleep disturbance. Low parental income and educational level associated with PIU. |

| [42] 2019, Taiwan | n = 503, 17.05 years, 100% | Young’s IAT | PSQI | PIU was associated with low sleep quality-latency-duration and use of sleep medication. |

| [43] 2016, Turkey | n = 1061, 16.2 years, 50.0% | IAS | PSQI | PIU was associated with poor sleep quality and lack of parental supervision. |

| [44] 2018, China | n = 4750, 16.0 years, 50.8% | Young’s IAT | PSQI | PIU associated with elevated risk of sleep disturbance. Sleep disturbance was higher in females, older adolescents were at greater risk for sleep disturbance. |

| Study ** | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Question | 38 | 43 | 42 | 35 | 33 | 44 | 36 | 37 | 39 | 33 | 40 | 41 |

| Were the aims/objectives of the study clear? | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Was the study design appropriate for the stated aim(s)? | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Was the sample size justified? | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | N | N | Y |

| Was the target/reference population clearly defined? (Is it clear who the research was about?) | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Was the sample frame taken from an appropriate population base so that it closely represented the target/reference population under investigation? | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Was the selection process likely to select subjects/participants that were representative of the target/reference population under investigation? | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Were measures undertaken to address and categorize non-responders? | Y | Y | Y | N | N | N | Y | Y | N | Y | N | Y |

| Were the risk factor and outcome variables measured appropriate to the aims of the study? | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Were the risk factor and outcome variables measured correctly using instruments/measurements that had been trialled, piloted or published previously? | Y | Y | Y | N | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y |

| Is it clear what was used to determined statistical significance and/or precision estimates? (e.g., p-values, confidence intervals) | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Were the methods (including statistical methods) sufficiently described to enable them to be repeated? | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y |

| Were the basic data adequately described? | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Does the response rate raise concerns about non-response bias? | N * | N * | N * | N * | N * | N * | N * | N * | DK | N * | N * | N * |

| If appropriate, was information about non-responders described? | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | N | N | Y | N | Y | Y | Y |

| Were the results internally consistent? | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Were the results presented for all the analyses described in the methods? | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Were the authors’ discussions and conclusions justified by the results? | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Were the limitations of the study discussed? | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | N | Y | Y | N |

| Were there any funding sources or conflicts of interest that may affect the authors’ interpretation of the results? | DK | N * | DK | N * | N * | N * | DK | N * | DK | DK | N * | N * |

| Was ethical approval or consent of participants attained? | Y | Y | Y | Y | DK | Y | DK | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kokka, I.; Mourikis, I.; Nicolaides, N.C.; Darviri, C.; Chrousos, G.P.; Kanaka-Gantenbein, C.; Bacopoulou, F. Exploring the Effects of Problematic Internet Use on Adolescent Sleep: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 760. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18020760

Kokka I, Mourikis I, Nicolaides NC, Darviri C, Chrousos GP, Kanaka-Gantenbein C, Bacopoulou F. Exploring the Effects of Problematic Internet Use on Adolescent Sleep: A Systematic Review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2021; 18(2):760. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18020760

Chicago/Turabian StyleKokka, Ioulia, Iraklis Mourikis, Nicolas C. Nicolaides, Christina Darviri, George P. Chrousos, Christina Kanaka-Gantenbein, and Flora Bacopoulou. 2021. "Exploring the Effects of Problematic Internet Use on Adolescent Sleep: A Systematic Review" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18, no. 2: 760. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18020760

APA StyleKokka, I., Mourikis, I., Nicolaides, N. C., Darviri, C., Chrousos, G. P., Kanaka-Gantenbein, C., & Bacopoulou, F. (2021). Exploring the Effects of Problematic Internet Use on Adolescent Sleep: A Systematic Review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(2), 760. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18020760