Leveraging 3D Printing Capacity in Times of Crisis: Recommendations for COVID-19 Distributed Manufacturing for Medical Equipment Rapid Response

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Discussion

2.1. Regulation

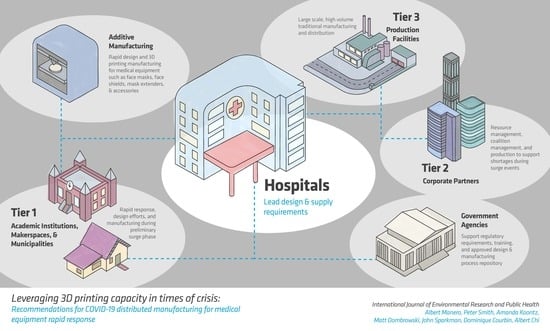

2.2. Coalitions

2.2.1. Identifying Supply Shortages

2.2.2. Unified Production Coalitions

2.2.3. Design Work, Challenges, and Resource Sharing

2.3. Strengths and Limitations

2.3.1. Face Masks

2.3.2. Face Shields

2.3.3. Ventilators

2.3.4. Nasopharyngeal Swabs

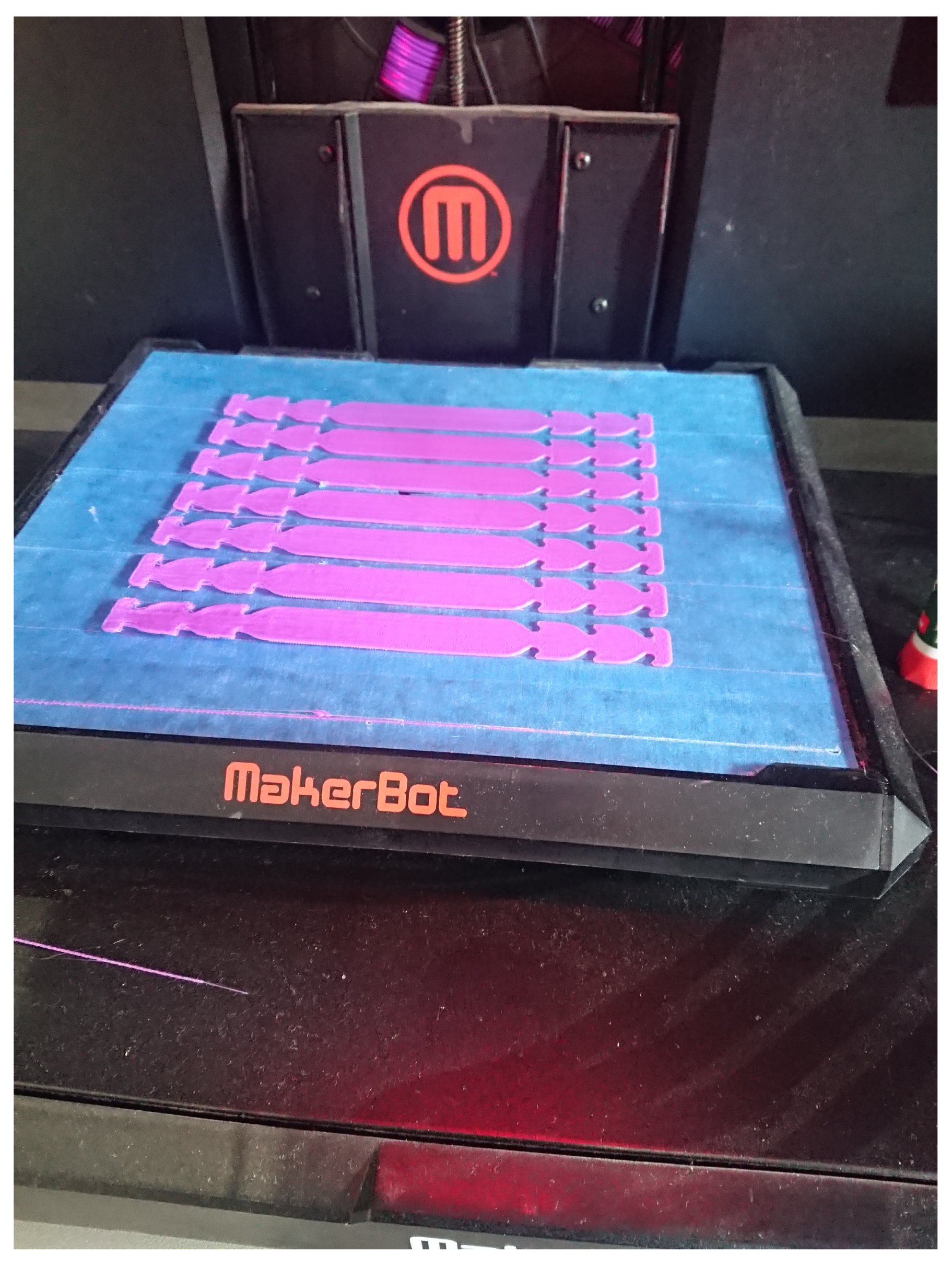

2.3.5. Accessories

2.4. File Sharing and Security

3. Recommendations

3.1. Hospital Infrastructure

- (i)

- Manufacturing and design capacity will allow the design and evaluation for parts and equipment prior to critical need. This will enable hospital staff to review current capacities and identify strategies for frequently replaced or consumed parts. Developing designs for spare replaceable parts prepared prior to critical needs can reduce inventory demands. When surge demands or supply chain issues emerge, hospitals will have standardized and validated designs to engage community and national coalitions to pivot manufacturing needs quickly to fill gaps in the short term. This capacity will also encourage hospitals to take an innovative approach toward the tools and equipment used in the hospital, which may improve surgical instrumentation and use-specific tool situations.

- (ii)

- Emergency manufacturing may be possible during surge events for hospitals with sufficient equipment and design knowledge. For certain equipment items, like face shields, hospitals may be able to have supply stock ready in case of emergency needs to augment traditional supplies. At the start of potential surge events nationally or internationally, short-run manufacturing can be initiated to increase supplies of key components with the support of community networks.

3.2. Regulation

- (i)

- Having archived reputable designs and instructions will reduce the time to start broad distributed manufacturing efforts, critical to building sufficient supply before the surge. This partnership and print exchange are critical for future surge events, and a dedicated curation of designs and production techniques should be prioritized by NIH and the FDA for rapid implementation.

- (ii)

- Guidelines and training information for local Institutional Review Boards, liability, and risk management should be prioritized to clearly communicate best practices, authorization requirements, and safety guidelines. This will reduce the time for coordinated efforts to begin for academic institutions, municipalities, and corporate manufacturers and ensure that uniform protocols are implemented.

3.3. Leverage Existing Communities

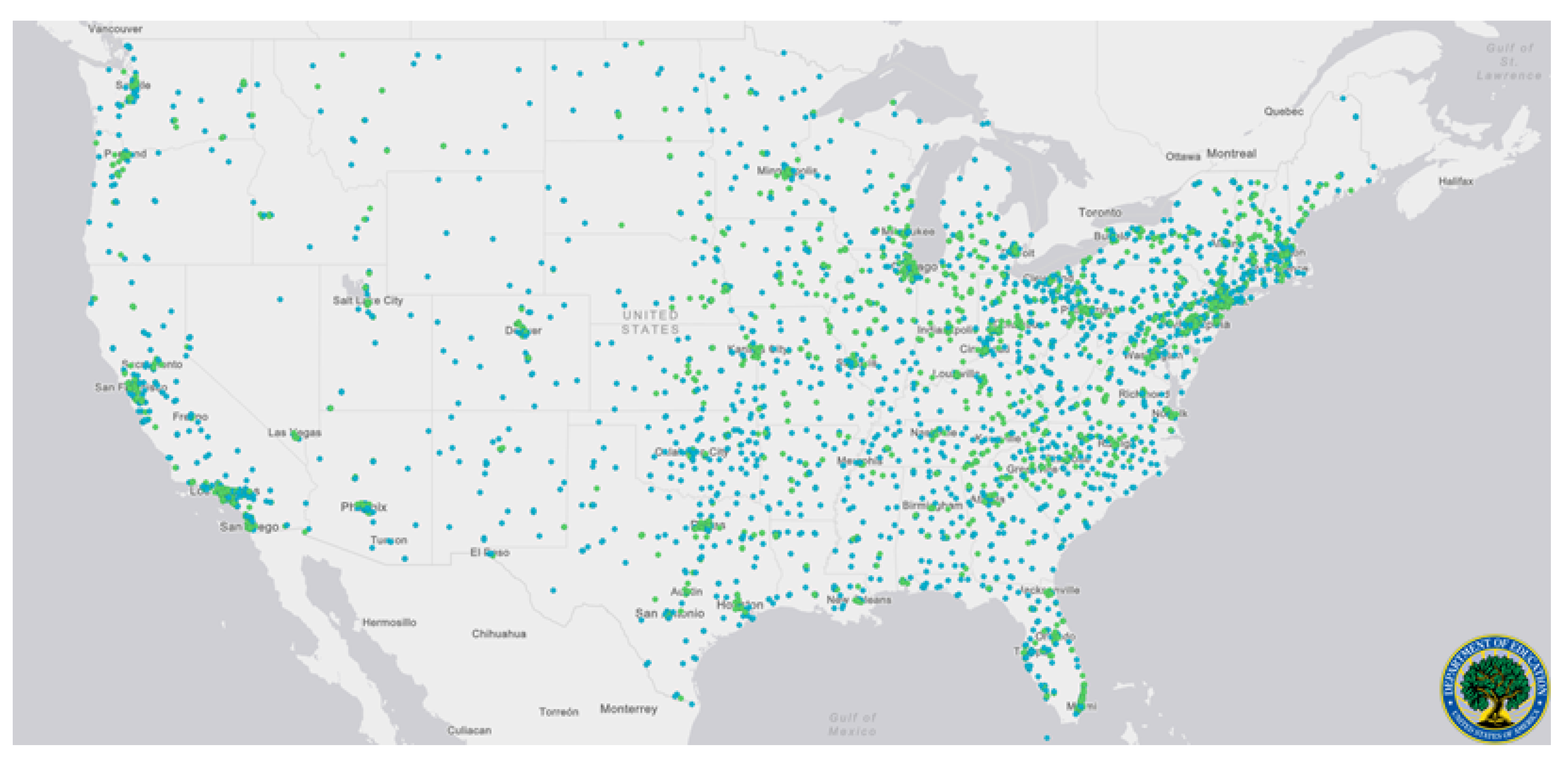

3.3.1. Education Systems

3.3.2. Defense Industry

3.4. Establishing Community Networks

- (i)

- Evaluate community resources: In order to support the hospital infrastructure, a mesh network of distributed manufacturing facilities must be developed. This is complex as it extends beyond the available equipment. There is a need to evaluate what type of equipment can be useful in a crisis for specific types of productions, what facilities or networks in local communities already supply this equipment, how it can be leveraged to maximum efficiency and flexibility, and what parts or hardware are susceptible to shortfall in the case of a crisis. The needs must then be evaluated for the ease of manufacturing through tools available locally including maker spaces and other corporate or educational manufacturing facilities. These facilities must be vetted for the quality of the equipment, supporting the right materials, and for the ability to deliver, house, and manipulate the appropriate materials. This database should be handled by a central organization that should keep track of machines, materials, and expertise.Informal networks and organizations that are created to solve one particular problem can come to remain after the initial need, becoming more established and able to address a broader scope of issues [17]. This is an important consideration in response to COVID-19 in two directions, in that production services can contemporaneously look to informal community networks to further develop social capital that enables a more effective and resilient response, while the informal networks that became established during this time should aim to be maintained as a form of social infrastructure to meet future demands.Empowering an equitable, embedded social infrastructure will entail (1) acknowledging power differentials (economic, physical, and human capital), (2) determining stakeholders (e.g., small and mass producers, investors, at-risk community members), and (3) developing trust in the social network. This process of embedding social infrastructure therefore also includes transparently sharing resources and getting commitment from stakeholders, and more specifically determining the beneficiaries. Beneficiaries, in this instance, relate to the positionality of organizations and individuals. Creating a knowledge chain that includes those who are likely to be in need of services, who offer interpersonal services (e.g., nurses), and those on the production side will have differing knowledge of and impact on production and distribution. Therefore, involving a variety of stakeholders in the creation of community networks can greatly benefit the development and embeddedness of social infrastructure, creating higher buy-in and ability to activate social resources quickly.

- (ii)

- Support a repository of vetted designs: The community must be supported by vetted infrastructure that provides access to designs, keeps track of distributed manufacturing resources, and can aid in logistical support. The design of the parts being created should be handled by a central organization that not only keeps track of the available infrastructure and provides vetted designs. These designs should, when possible, be pre-vetted and approved by governing organizations. Effort should also be made to support IP and ownership of industrial and medical designs; permission should be sought from the patent holders for any parts that are exclusive to one organization, but saving lives should be the primary focus of such a repository of designs. This may require government leadership to allow emergency production to support distributed manufacturing in short-term emergency situations.This distribution process can be expedited through the development of social infrastructure, as network members can establish norms of reciprocity, sanctions that uphold standards of emergency response, trust, and informational channels. The obligation of saving lives, as a primary focus, can establish expectations and direct focus to identifying resources available to each party even by sharing needed production resources in exchange for needed expertise.

- (iii)

- Encourage participation and protect participants: Concrete rewards and recognition must be incorporated to encourage continued support of the coalition. Developing social infrastructure that supports informal associations that enable community members, stakeholders, and specialists to participate smoothly not only requires community support for vetted files and logistical support, but participants in this ecosystem must feel safe, helpful, and rewarded. In an effort to expand the reach of such an enterprise, the authors suggest technical, professional organizations consider leading in a multi-tier local and national approach. Organizations and municipalities can leverage the open database [3] to establish guidelines for distributed manufacturing volume appropriate for their local community. Establishing the clear communication of stakeholders and recipients, in particular in the local network, will strengthen participation.Investing in social capital can encourage a sense of shared responsibility through civic engagement and, when based on authentic participation, trust from participants. This encourages decision-making from the ground-up to address “local” needs, but needs to be done in such a way that a process is in place for strategic activities, helping to create a power balance. Additionally, while not directly connected to economic capital, the development of reciprocity can encourage further investments, expanding potential monetary benefits to involved parties. This, in turn, increases the strength of the community network and emergency response abilities. Such social networks can then be seen as a resource to an individual or corporation, increasing capacity to meet certain ends otherwise not possible. This synergistic production process is therefore based on the relations amongst members, regulating production and services as social capital “allows” certain activities and actions to happen because it is also understood that only certain actions are acceptable. Establishing norms that expand beyond institutional regulation can encourage the trust and social regulation during a surge that help to serve as a stopgap for safety and public information trust. The mesh network, or mesh of networks, can be uniquely positioned to support local surges or disasters that limit a local response.

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| COVID-19 | SARS-CoV-2 Virus Disease |

| DoD | United States Department of Defense |

| EUA | Emergency Use Authorization |

| FDM | Fused Deposition Modeling |

| IRB | Institutional Review Board |

| NIH | National Institutes of Health |

| NIOSH | National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health |

| PEEP | Positive End Expiratory Pressure |

| PIP | Peak Inspiratory Pressure |

| PPE | Personal Protective Equipment |

| R-FAB | Rapid Fabrication via Additive-Manufacturing on the Battlefield |

| REACT | Reverse Engineering and Critical Tooling |

| SLS | Selective Laser Sintering |

References

- World Health Organization. Statement on the Second Meeting of the International Health Regulations (2005) Emergency Committee Regarding the Outbreak of Novel Coronavirus (2019-nCoV). 2020. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/detail/30-01-2020-statement-on-the-second-meetingof-the-international-health-regulations-(2005)-emergency-committee-regarding-the-outbreak-of-novelcoronavirus-(2019-ncov) (accessed on 24 April 2020).

- Washington Post Staff. Mapping the Worldwide Spread of the Coronavirus. 2020. Available online: https://www.washingtonpost.com/graphics/2020/world/mapping-spread-new-coronavirus/ (accessed on 24 April 2020).

- Jha, A.; Tsai, T.; Figueroa, J.; Jacobson, B.; Friedhoff, S. US Hospital Capacity. 2020. Available online: https://globalepidemics.org/our-data/hospital-capacity/ (accessed on 25 April 2020).

- Fink, S. Worst-Case Estimates for US Coronavirus Deaths. 2020. Available online: https://www.nytimes.com/2020/03/13/us/coronavirus-deaths-estimate.html (accessed on 28 April 2020).

- Ventilator Stockpiling and Availability in the US and Internationally. 2020. Available online: https://www.centerforhealthsecurity.org/resources/COVID-19/COVID-19-fact-sheets/200214-VentilatorAvailability-factsheet.pdf (accessed on 24 April 2020).

- Personal Protective Equipment (PPE) Assumptions. 2020. Available online: https://www.centerforhealthsecurity.org/resources/COVID-19/PPE/PPE-assumptions (accessed on 27 April 2020).

- Balmer, C.; Pollina, E.; Reuters. Italy’s Lombardy Asks Retired Health Workers to Join Coronavirus Fight. Reuters, 2020. Available online: https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2020/03/italys-lombardy-etired-health-workers-coronavirus-covid19-pandemic (accessed on 28 April 2020).

- High Proportion of Healthcare Workers with COVID-19 in Italy Is a Stark Warning to the World: Protecting Nurses and Their Colleagues Must Be the Number One Priority. 2020. Available online: https://www.icn.ch/news/high-proportion-healthcare-workers-covid-19-italy-stark-warning-world-protecting-nurses-and (accessed on 14 June 2020).

- Pfleger, P. Technology to Clean and Reuse PPE Is Being Deployed to Hotspot Hospitals. 2020. Available online: https://www.npr.org/2020/03/30/823803831/technology-to-clean-and-reuse-ppe-is-being-deployed-to-hotspot-hospitals (accessed on 23 April 2020).

- Zhou, Z.G.; Yue, D.S.; Mu, C.L.; Zhang, L. Mask is the possible key for self-isolation in COVID-19 pandemic. J. Med. Virol. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, Q.X.; Shan, H.; Zhang, H.L.; Li, G.M.; Yang, R.M.; Chen, J.M. Potential utilities of mask-wearing and instant hand hygiene for fighting SARS-CoV-2. J. Med. Virol. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paxton, N.C.; Forrestal, D.P.; Desselle, M.; Kirrane, M.; Sullivan, C.; Powell, S.K.; Woodruff, M.A. N95 Respiratory Masks for COVID-19: A Review of the Literature to Inform Local Responses to Global Shortages. 2020; Pre-Print. [Google Scholar]

- Eninger, R.M.; Honda, T.; Adhikari, A.; Heinonen-Tanski, H.; Reponen, T.; Grinshpun, S.A. Filter performance of N99 and N95 facepiece respirators against viruses and ultrafine particles. Ann. Occup. Hyg. 2008, 52, 385–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ranney, M.L.; Griffeth, V.; Jha, A.K. Critical supply shortages—The need for ventilators and personal protective equipment during the COVID-19 pandemic. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020, 18, e41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, A.; Kasloff, S.B.; Leung, A.; Cutts, T.; Strong, J.E.; Hills, K.; Vazquez-Grande, G.; Rush, B.; Lother, S.; Zarychanski, R.; et al. N95 Mask Decontamination using Standard Hospital Sterilization Technologies. medRxiv 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration Commissioner. Investigating Decontamination and Reuse of Respirators. 2020. Available online: https://www.fda.gov/emergency-preparedness-and-response/mcm-regulatory-science/investigating-decontamination-and-reuse-respirators-public-health-emergencies (accessed on 17 April 2020).

- Coleman, J.S. Social capital in the creation of human capital. Am. J. Sociol. 1988, 94, S95–S120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofmann, M.; Burke, J.; Pearlman, J.; Fiedler, G.; Hess, A.; Schull, J.; Hudson, S.E.; Mankoff, J. Clinical and maker perspectives on the design of assistive technology with rapid prototyping technologies. In Proceedings of the 18th International ACM SIGACCESS Conference On Computers and Accessibility, Reno, NV, USA, 24–26 October 2016; pp. 251–256. [Google Scholar]

- Manero, A.; Smith, P.; Sparkman, J.; Dombrowski, M.; Courbin, D.; Kester, A.; Womack, I.; Chi, A. Implementation of 3D printing technology in the field of prosthetics: Past, present, and future. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 1641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manero, A.; Smith, P.; Sparkman, J.; Dombrowski, M.; Courbin, D.; Barclay, P.; Chi, A. Utilizing additive manufacturing and gamified virtual simulation in the design of neuroprosthetics to improve pediatric outcomes. MRS Commun. 2019, 9, 941–947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Department of Health and Human Services. Determination of Public Health Emergency. 2020. Available online: https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2020/02/07/2020-02496/determination-of-public-health-emergency (accessed on 17 April 2020).

- Department of Health and Human Services. Emergency Use Declaration. 2020. Available online: https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2020/03/10/2020-04823/emergency-use-declaration (accessed on 17 April 2020).

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration Commissioner. Emergency Use Authorization. 2020. Available online: https://www.fda.gov/emergency-preparedness-and-response/mcm-legal-regulatory-and-policy-framework/emergency-use-authorization#battellecovideua (accessed on 27 April 2020).

- Center for Devices and Radiological Health. FAQs on 3D Printing of Medical Devices and Accessories during COVID-19. 2020. Available online: https://www.fda.gov/medical-devices/3d-printing-medical-devices/faqs-3d-printing-medical-devices-accessories-components-and-parts-during-covid-19-pandemic (accessed on 17 April 2020).

- Food and Drug Administration Commissioner. FDA, VA, NIH, and America Makes COVID-19 Public-Private Partnership. 2020. Available online: https://www.fda.gov/emergency-preparedness-and-response/coronavirus-disease-2019-covid-19/fda-efforts-connect-manufacturers-and-health-care-entities-fda-department-veterans-affairs-national (accessed on 24 April 2020).

- Bourdieu, P. Distinction: Towards a Social Critique of the Judgement of Taste; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Coleman, J.S. Foundations of Social Capital; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Misener, L.; Mason, D.S. Creating community networks: Can sporting events offer meaningful sources of social capital? Manag. Leis. 2006, 11, 39–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Get Us PPE. 2020. Available online: https://getusppe.org/states/ (accessed on 17 April 2020).

- 1 Million Face Shields and Counting: The Team Making It Possible. Available online: https://news.bostonscientific.com/project-shield (accessed on 13 June 2020).

- Howard, P.W. Miracle in Plymouth: UAW Worker Celebrates Ford Making 1 M Face Shields in 13 Days. 2020. Available online: https://www.freep.com/story/money/cars/ford/2020/04/06/ford-uaw-make-million-face-shields-nypd-nyfd/2951650001/ (accessed on 14 June 2020).

- COVID-19 AM Challenge Community. 2019. Available online: https://innovatedefense.net/nsin/covid19-3d (accessed on 2 April 2020).

- Prusa, J. 3D Printed Face Shields for Medics and Professionals. 2020. Available online: https://www.prusa3d.com/covid19/ (accessed on 14 June 2020).

- 3D Printing Support for Medical Professionals Fighting COVID-19. Available online: https://formlabs.com/covid-19-response/medical/ (accessed on 14 June 2020).

- Stratasys Helps: Responding to the COVID-19 Crisis. 2020. Available online: https://go.stratasys.com/lp-stratasys-helps.html (accessed on 31 March 2020).

- Glowforge: 2 Million Ears Saved. 2020. Available online: https://meet.glowforge.com/earsavers/ (accessed on 13 April 2020).

- Open Source Face Shield. Available online: https://making.engr.wisc.edu/shield-make/ (accessed on 13 June 2020).

- Donohue, B.; Holtz, J.; McQuate, S. UW’s 3D printed COVID-19 Face Shields: From Innovation to Delivery. Available online: https://www.washington.edu/news/2020/04/13/uws-3d-printed-covid-19-face-shields-from-innovation-to-delivery/ (accessed on 15 June 2020).

- Face Shields. Available online: https://pwp.gatech.edu/rapid-response/face-shields/ (accessed on 15 June 2020).

- HP COVID-19 Response. 2020. Available online: https://enable.hp.com/us-en-3dprint-COVID-19-containment-applications (accessed on 3 April 2020).

- CoVent-19 Challenge Asks Millions of Designers and Engineers to Respond to the Ventilator Crisis. 2020. Available online: https://apnews.com/BusinessWire/13b3451973ad41059a7196e0eed477ec (accessed on 20 April 2020).

- Begley, S.; Lanson, S. Analysis Urges Less Reliance on Ventilators for Coronavirus Patients. 2020. Available online: https://www.statnews.com/2020/04/21/coronavirus-analysis-recommends-less-reliance-on-ventilators/ (accessed on 22 April 2020).

- National Institutes of Health. COVID-19 Treatment Guidelines Panel. Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) Treatment Guidelines. 2020. Available online: https://covid19treatmentguidelines.nih.gov/critical-care/ (accessed on 22 April 2020).

- Kent, C. Start-Up Which 3D-Printed Lifesaving Ventilator Valves May Face Legal Action. 2020. Available online: https://www.medicaldevice-network.com/news/3d-printed-valves-covid-19-italy/ (accessed on 20 April 2020).

- Rankouhi, B.; Javadpour, S.; Delfanian, F.; Letcher, T. Failure analysis and mechanical characterization of 3D printed ABS with respect to layer thickness and orientation. J. Fail. Anal. Prev. 2016, 16, 467–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keleş, Ö.; Blevins, C.W.; Bowman, K.J. Effect of build orientation on the mechanical reliability of 3D printed ABS. Rapid Prototyp. J. 2017, 23, 320–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flanagan, S.T.; Ballard, D.H. 3D Printed Face Shields: A Community Response to the COVID-19 Global Pandemic. Acad. Radiol. 2020, 27, 905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ishack, S.; Lipner, S.R. Applications of 3D Printing Technology to Address COVID-19 Related Supply Shortages. Am. J. Med. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Swennen, G.R.; Pottel, L.; Haers, P.E. Custom-made 3D-printed face masks in case of pandemic crisis situations with a lack of commercially available FFP2/3 masks. Int. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2020, 49, 673–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pearce, J. Distributed Manufacturing of Open-Source Medical Hardware for Pandemics. J. Manuf. Mater. Process. 2020, 4, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Army Researchers Help Design 3D-Printed Ventilators. 2020. Available online: https://www.army.mil/article/234822/army_researchers_help_design_3d_printed_ventilators (accessed on 17 June 2020).

- Robinson, E. Ventilators Available With the Flip of a Switch. 2020. Available online: https://news.ohsu.edu/2020/04/24/ventilators-available-with-the-flip-of-a-switch (accessed on 24 April 2020).

- Quinn, L. Pigs Push Forward Quick Solution for Emergency Ventilators. 2020. Available online: https://aces.illinois.edu/news/pigs-push-forward-quick-solution-emergency-ventilators (accessed on 17 June 2020).

- Callahan, C.J.; Lee, R.; Zulauf, K.; Tamburello, L.; Smith, K.P.; Previtera, J.; Cheng, A.; Green, A.; Abdul Azim, A.; Yano, A.; et al. Open Development and Clinical Validation of Multiple 3D-Printed Sample-Collection Swabs: Rapid Resolution of a Critical COVID-19 Testing Bottleneck. medRxiv 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, J. BIDMC Physician-Scientists Spearhead Effort to Address Nationwide COVID-19 Testing Swab Shortage. 2020. Available online: https://www.bidmc.org/about-bidmc/news/2020/03/3d-printed-swabs (accessed on 19 May 2020).

- Teune, V. Disposable Ear Relief Strap. 2020. Available online: https://3dprint.nih.gov/discover/3dpx-013564 (accessed on 6 April 2020).

- Michalski, M.H.; Ross, J.S. The shape of things to come: 3D printing in medicine. JAMA 2014, 312, 2213–2214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ventola, C.L. Medical applications for 3D printing: Current and projected uses. Pharm. Ther. 2014, 39, 704. [Google Scholar]

- Stratasys Ltd. MakerBot Thingiverse Celebrates 10 Years of 3D Printed Things. 2018. Available online: https://investors.stratasys.com/news-events/press-releases/detail/547/makerbot-thingiverse-celebrates-10-years-of-3d-printed (accessed on 8 May 2020).

- US Department of Education. Integrated Postsecondary Education Data System from the National Center for Education Statistics College Map. 2020. Available online: https://nces.ed.gov/ipeds/collegemap/# (accessed on 5 May 2020).

- Inspector General. Audit of the DoD’s Use of Additive Manufacturing for Sustainment Parts; Technical Report DODIG-2020-003; Department of Defense: Washington, DC, USA, 2019.

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Manero, A.; Smith, P.; Koontz, A.; Dombrowski, M.; Sparkman, J.; Courbin, D.; Chi, A. Leveraging 3D Printing Capacity in Times of Crisis: Recommendations for COVID-19 Distributed Manufacturing for Medical Equipment Rapid Response. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 4634. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17134634

Manero A, Smith P, Koontz A, Dombrowski M, Sparkman J, Courbin D, Chi A. Leveraging 3D Printing Capacity in Times of Crisis: Recommendations for COVID-19 Distributed Manufacturing for Medical Equipment Rapid Response. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2020; 17(13):4634. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17134634

Chicago/Turabian StyleManero, Albert, Peter Smith, Amanda Koontz, Matt Dombrowski, John Sparkman, Dominique Courbin, and Albert Chi. 2020. "Leveraging 3D Printing Capacity in Times of Crisis: Recommendations for COVID-19 Distributed Manufacturing for Medical Equipment Rapid Response" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 17, no. 13: 4634. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17134634

APA StyleManero, A., Smith, P., Koontz, A., Dombrowski, M., Sparkman, J., Courbin, D., & Chi, A. (2020). Leveraging 3D Printing Capacity in Times of Crisis: Recommendations for COVID-19 Distributed Manufacturing for Medical Equipment Rapid Response. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(13), 4634. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17134634