Abstract

The acquisition of competencies in basic life support (BLS) among university students of health sciences requires specific and updated training; therefore, the aim of this review was to identify, evaluate, and synthesise the available scientific knowledge on the effect of training in cardiorespiratory resuscitation in this population. A comprehensive literature search was conducted in MEDLINE, CUIDEN, Web of Science, Wiley Online Library, CINAHL, and Cochrane, including all randomised clinical trials published in the last ten years that evaluated basic life support training methods among these students. We selected a total of 11 randomissed clinical trials that met the inclusion criteria. Participants were nursing and medicine students who received theoretical and practical training in basic life support. The studies showed a great heterogeneity in training methods and evaluators, as did the feedback devices used in the practical evaluations and in the measurement of quality of cardiorespiratory resuscitation. In spite of the variety of information resulting from the training methods in basic life support, we conclude that mannequins with voice-guided feedback proved to be more effective than the other resources analysed for learning.

1. Introduction

Cardiorespiratory arrest (CRA) has become a major public health problem and one of the leading causes of death in the Western world in recent years. Cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) is the technique used in the cases of CRA. It consists of thoracic compressions (which are important for the perfusion of vital organs) and rescue breaths by means of artificial ventilation [1,2,3,4,5,6,7]. The quality of CPR is vitally important, and it depends on the level of knowledge and skills held by those who carry out the CPR. Even among healthcare professionals, that level can be inadequate. Therefore, an improvement in educating healthcare professionals in CPR techniques may increase survival rates in cases of CRA [2,8,9].

Within a hospital, the nursing staff is usually the first group of professionals to identify CPR, so competence in basic life support (BLS) is a key factor in recognising cardiac arrest, activating emergency systems, initiating effective CPR, and safely using the defibrillator [10,11,12,13]. Roh and Issenberg concluded that technical skills in CPR among nursing students are very poor, and that despite efforts to improve the quality of psychomotor skills, the results obtained are still not encouraging [5].

As has previously been described, BLS is a fundamental therapy for saving lives, and it requires a broad knowledge of cognitive and psychomotor skills. [13,14] In spite of this, several studies have shown that BLS education is difficult: learners’ retention of motor skills is poor (even immediately after they have completed the course), causing less-than-ideal performance of CPR [6,14,15]. In addition, if those who have been trained in CPR do not frequently perform it, their skills deteriorate over a period of between 3 and 6 months. Therefore, it is very important that in addition to developing different learning strategies, these should be combined with other recycling (retraining) measures during that period of time [10,16].

Within CPR teaching, different methods have been proposed, such as simulation, classical instructor-led teaching, and self-directed mannequins with continuous verbal feedback, which have been shown to be much more effective for retaining knowledge and motor skills [9,12,17,18]. Other methods of learning may be based on interactive videos, high-fidelity 3D simulation scenarios, and partner-based training, in which very positive results have been obtained [1,19].

With all this, there is a need for a systematic review that includes a comparison in the methods used (traditional versus alternative) trying to find the most effective for the teaching of BLS, CPR, and use of automatic external defibrillators (AEDs) in university health science students.

Finally, the research question selected by the authors was what is the most effective method for teaching of BLS, CPR techniques, and use of AED for health science students?

So that, the main objective of this systematic review was to identify, evaluate and synthesize what kind of method is more effective of training in basic life support, cardiopulmonary resuscitation techniques and use of automatic external defibrillator among health science students.

2. Materials and Methods

We undertook a systematic review in line with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) statement [20].

2.1. Literature Search

The search for articles was conducted during February and March 2017. The scientific databases searched were MEDLINE, CUIDEN, Web of Science, Wiley Online Library, CINAHL, and Cochrane.

We used both English and Spanish descriptors that were located in the Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) and in Descriptores de Ciencias de la Salud (Health Sciences Descriptors; DeCS). These included “health science”, “students”, “cardiopulmonary resuscitation”, “training”, “traditional”, “new methods”, “motor skills”, “simulation”, and “evaluation of efficacy-effectiveness”. Descriptors that were synonymous with one another were combined in the search with the Boolean “OR” operator, while the “AND” operator was used to interrelate different concepts.

As an example, one of the search strategies used in the Medline database was: “health science students” AND (“traditional cardiopulmonary resuscitation training” OR “new methods cardiopulmonary resuscitation training”).

2.2. Eligibility Criteria

The studies that were selected for the systematic review met the following inclusion criteria.

- Year of publication: we included all articles published between 2007 and 2017, in order to obtain the most recent articles on training methods.

- Language: Spanish and/or English.

- Studies: we included full texts of randomised clinical trials (RCTs), because these epidemiological studies provide more evidence.

- Population: students of both sexes who were pursuing university degrees related to the health sciences.

- Intervention: any method used in the teaching of BLS and the acquisition of technical skills in CPR in adults.

- Results: we selected studies that contained information about the socio-demographic characteristics of participants, ones that analysed the effect of training in the acquisition of theoretical and practical knowledge, and ones that reported on measurement tools for skills relating to placement of the hands, number of compressions, average depth of compressions, number of ventilations, or volumes administered.

All articles that did not meet these criteria were excluded.

2.3. Selection of Articles and Data Extraction

Initially, two reviewers independently performed the article search in order to minimise selection bias. After deleting duplicates, an initial selection of articles was carried out following independent analysis of the titles.

We then conducted a second review that included the reading of titles, abstracts and key words of the articles found by the two reviewers, who jointly proceeded to make the final selection of articles. At this point, a third independent reviewer intervened in the decision-making process in cases of disagreement. Finally, after obtaining the full-text articles, the third and final selection took place, in which the articles that were eventually used in the review were chosen.

Because the studies reviewed were very heterogeneous and had different methods of intervention and assessment, it was not possible to undertake a meta-analysis.

Last of all, and following the final selection of the articles included in the review, we extracted the following information from each article: first author, publication year, population, study groups, learning method, evaluation method, immediate results, and results after refreshers/recycling.

2.4. Evaluation of the Studies’ Methodological Quality

The methodological quality of the randomised clinical trials included in the review was evaluated using the Jadad scale [21].

The validity of this scale has been proven in the scientific literature, and it is simple and quick to use. In addition, the researchers were already trained in its use, having deployed it in other studies.

The scale gives a score between 0 and 5 points, primarily to three aspects: randomisation, blinding (double-blind), and description of withdrawals and dropouts during follow-up. A score of 5 represents the highest possible methodological quality, while a score of under 3 means that the evaluated clinical trial is of a low methodological quality. Below, we provide the full scale with the items and their corresponding scores (Table 1).

Table 1.

Jadad scale.

3. Results

3.1. Study Characteristics and Quality Evaluation

Through our search, we obtained a total of 522 articles that were potentially eligible for the review. Of them, 371 were eliminated on the basis that they were duplicates from across the different databases.

After completing the first selection (reading of titles), 109 articles were excluded. We then analysed the abstracts of the 42 articles that were still potentially valid for inclusion, through which a total of 18 were excluded. Finally, and after obtaining the remaining 24 articles in full-text form, a total of 11 studies were included in the review [6,9,11,12,13,16,17,18,19,22,23].

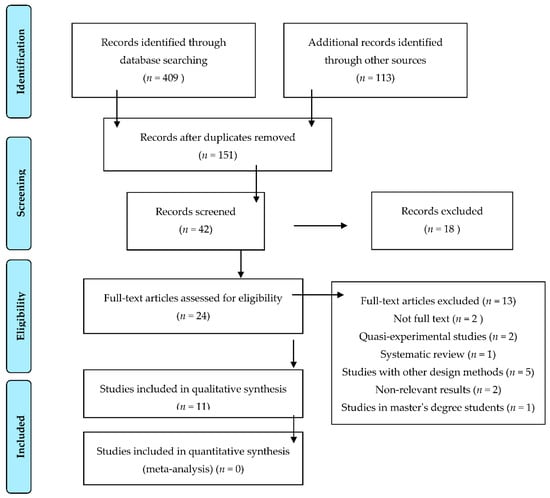

The excluded articles were those which did not meet the inclusion criteria for the study, which are shown in a flow diagram in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Flowchart with selection of articles included in the review.

Table 2 presents the final articles that were part of the systematic review based on their methodological quality.

Table 2.

Methodological quality of studies, calculated with the Jadad scale. BLS basic life support; AED: automatic external defibrillator.

The scores obtained on the Jadad scale for the analysed articles ranged from 2 to 5 points, with an average of 2.81 points. Only one article with double blinding [22] obtained the maximum score, and four articles [9,12,19,23] (which were transversal and involved only one measure) scored 2 points. All the studies, with the exception of the one conducted by Isbye et al. [22], presented a high risk of bias, as they involved single blinding, making it impossible for there to be double-blinding for participants and researchers.

All the data extracted from each article, with general and specific characteristics, are summarised in Table 3.

Table 3.

Description of the studies included in the review. VAM: voice advisory mannequin.

3.2. Study Participants

The participants of the different studies were university students from different branches of the health sciences, including mainly nursing students [11,12,13,17,18,19] and medicine students [22,23]. Only one study did not distinguish the students’ degree titles [6].

The analysed studies included a total of 2175 participants; that by Partiprajak et al. (n = 30) [13] had the fewest participants, while that by Oermann et al. (n = 606) [19] had the most.

3.3. Participants’ Knowledge Prior to the Undertaking of the Studies

Information about previous knowledge of and technical skills in BLS and CPR was collected in seven articles [9,11,12,13,16,18,22]. This meant that some authors excluded a certain number of participants from studies [9,16], or conversely used this information as a basis when establishing prior training [11,12,13,18,22].

3.4. Teaching Methods and Duration

The different teaching methods primarily related to two aspects: theoretical content aspects, and aspects derived from the acquisition of technical skills in CPR. To this end, the researchers were guided by the recommendations of the American Heart Association (AHA) [9,12,13,17,18,23] and of the European Resuscitation Council (ERC) [6,11,19,22]. The exception in this regard was the study by Mpotos et al. [16], which does not mention any recommendations. These guides were also employed later to carry out measurements in the evaluations.

For the theoretical level of the training, the authors employed different techniques according to the different groups that they created within their studies. Accordingly, instructors taught lectures using visual media such as presentations or videos [6,9,11,12,17,23]. In other cases, the participants acquired knowledge independently through computer CDs or DVDs provided by the researchers [9,13] or through different tests with self-assessments [16,19]. In the rest of the studies, training methods were not specified [18,22].

As for the teaching of skills, the most used method was traditional instructor-led teaching, which appeared in a total of 6 studies [9,11,12,17,22,23]. In the study by Li et al. [23], one of the group’s first underwent a pre-assessment (a practical scenario), which after being recorded and reviewed by the instructors, was subsequently used for training purposes as feedback.

The second-most-used method was training with mannequins that had feedback systems (these are known as mannequins with a skill reporter). These featured in five studies [6,11,13,16,19]. In addition, in four studies the participants from some groups carried out self-directed learning with mannequins that, in addition to feedback, had voice prompts that corrected errors (the so-called voice advisory mannequin, VAM) [9,12,18,22]. It is also worth mentioning that in the studies by Aqel et al. [17] and Boada et al. [19] high-fidelity simulation programs were used to deliver the training.

Finally, in two studies [6,9], the control groups did skills training without any kind of feedback or supervision from instructors, and in two others [16,18] no skills practice of any kind was performed.

In terms of the duration of the training undertaken to acquire knowledge and skills, the most homogeneous approach was the traditional teaching method’s time frame of between four and five hours, except in the case of the study carried out by Spooner et al. [6], which took place over 8 h. There were large variations in the other studies.

3.5. Methods Used in the Evaluation

Evaluation methods were organised according to knowledge and skills. To measure knowledge levels, the methods used were pre-intervention [23], post-intervention [9,19] or pre- and post-intervention [11,13,17] questionnaires, or a subjective assessment by instructors of performance in the sequence of BLS steps [6,17]. In addition, two studies included a questionnaire about the confidence that participants had in executing the skills after the training [11,13]. The measurement of CPR-technique skills during the period in which they were being acquired was taken in 10 of the 11 studies through a skill reporter mannequin [6,9,11,12,13,16,18,19,22,23].

3.6. Results Obtained after the Intervention

The different results obtained after analysing the articles were divided into two groups for drafting purposes. We will first discuss the results of the studies in which a single measure was used following completion of the intervention, and we will then consider the other studies, in which more evaluations were carried out over time.

Studies that involved a measurement that evaluated theoretical knowledge reported an improvement in all groups [19,23], with the exception of the study by Roppolo et al. [9], in which the control group that received theoretical training with an instructor obtained better results. In the study by Kardong Edgren et al., knowledge was not measured [12].

As for the acquisition of technical CPR skills, the groups that acquired knowledge through a VAM obtained better results with statistically significant differences relative to the rest of the groups [9,12]. In the study that used high-fidelity simulation, no differences between the groups were established [19]. Finally, in the study by Li et al., in which a group carried out a practical scenario with feedback provided by instructors to participants, significant results were obtained in CPR technique for all aspects except for the placement of hands (both groups obtained 100%) [23].

On the other hand, in the first assessment of the studies that applied several measurements [11,13], knowledge improved in all groups, with the exception of the study by Aqel et al. [17], in which the improvement was additionally statistically significant in the intervention group. In the study by Spooner et al. [6], the correct completion of the BLS algorithm was evaluated, with no differences between the groups. In addition, the studies by Hernández Padilla et al. [11] and by Partiprajak et al. [13] used questionnaires to analyse the confidence of participants in performing the CPR technique safely, and they noted an improvement in results after the intervention had been completed.

With respect to skills in performing CPR, in three studies [11,13,16], no differences were found between the different groups, while in the studies by Spooner et al. and Aqel et al. [6,17], the intervention groups performed better in both studies. Finally, in the study by Isbye et al. [22], the instructor-led group obtained better results than the self-directed groups that used a VAM.

3.7. Results Obtained after a Retention Period or Refreshers

Seven studies carried out a subsequent measurement after a refresher or simply by applying a knowledge retention period [6,11,13,16,17,18,22] over periods of time ranging from 6 weeks [6] to 1 year [18] after the intervention.

In six studies, a measurement for knowledge retention was used [6,11,13,16,17,22]. In the study by Spooner et al., after 6 weeks the group that had undertaken practice obtained better results, while there were no differences when it came to correctly applying the BLS algorithm. [6] In the study by Hernández Padilla et al., the results were better for the self-directed group at three months. [11] In the study by Partiprajak et al., after three months, worse results were obtained in terms of knowledge, similar results were found in terms of confidence of participants when performing CPR, and better results were obtained in terms of acquisition of CPR skills [13]. The study by Mpotos et al. observed that the control group that had not received practical skills training obtained better results than the intervention group at 6 months [16]. In the fifth study in which retention of knowledge was evaluated, carried out by Aqel et al. [17], it was observed that after 3 months the improvement in results for knowledge and skills in the group that received the high-fidelity simulation remained. Finally, the study by Isbye et al. concluded that there were no differences between the groups after 3 months [22].

In the study by Oermann et al. [18] there was no measurement of skills immediately after the intervention. Out of their control and intervention groups, they produced random subgroups at 3, 6, 9, and 12 months, which were the ones evaluated. Among these groups, no differences were established in terms of the number of compressions, volume: minute, or hand placements, but there were in relation to depth and volume administered, which decreased significantly as the measurements were taken over time. Finally, a fifth subgroup that was given a refresher was also established at 12 months, and statistically significant differences between the control and intervention groups were not obtained within it.

4. Discussion

To conduct this review, we drew on a total of 11 randomised clinical trials that were found in different databases and that aimed to assess the quality of training in CPR and BLS knowledge and technical skills among health sciences students. Most of the studies were conducted among nursing and medicine students, in line with the study by López Messa et al., which highlights that BLS training for future healthcare professionals should be reinforced at the undergraduate level, especially in nursing and medicine degrees [24].

The studies included in the review were of a low methodological quality according to the Jadad scale. In view of these findings, one priority that emerges is the need to increase the number of RCTs with methodological rigour, which would make it possible to minimise biases and facilitate the identification of progress in scientific evidence regarding BLS training among health sciences students. To this end, the use of this same scale in other reviews or similar studies would facilitate this process.

The articles are also characterised by the absence of homogeneity in establishing BLS training, technical CPR skills and use of AEDs. Despite this, the results have shown how studies that used VAM [9,11,12,18] improved all skills immediately or in the long term, though in the study by Isbye et al. [22] ventilations were not improved at first.

Moreover, the realisation of practical cases through different simulation programs of high fidelity provided better results fundamentally in the acquisition of theoretical knowledge [17,19].

Weidman et al. define learning through simulation as an essential part of training, whether it is high or low fidelity [25]. High-fidelity simulation is very useful when comparing the results obtained with real outcomes, even though it requires thorough intervention from the instructors [26,27]. In addition, this training provides realistic environments and is more student focused [28].

The use of a skill reporter or VAM mannequins with feedback results in a remarkable rise in the improvement of the quality of CPR performed by nursing and medicine students, since it allows them to correct their mistakes or undertake knowledge refreshers independently, making it feasible to not have an instructor on an ongoing basis. Along this line, the study by Nielsen et al. concludes that this type of learning improves knowledge and skills [29].

Finally, in the studies included in the review, the use of AED is scarcely mentioned. Although eight studies included AEDs as part of the theoretical and practical training [6,9,11,13,17,19,22,23], only Roppolo et al. [9] implemented a measure concerning the use of this device. They obtained unfavourable results that do not coincide with those of the study by Ahn et al. [30], the main finding of which was that students reduced intervention times as soon as they had an AED nearby. It has been shown that courses of between 2 and 4 h in the use of an AED may be enough to operate them safely [31].

Therefore, and despite the fact that the use of AEDs is a priority when it comes to saving lives, there is a need for more studies that more comprehensively evaluate training in and handling and application of these devices in order for there to be fuller performance within BLS.

Limitations

One of the main limitations of the study is that in spite of BLS and CPR training for health science students, the number of randomised clinical trials is not very high, and studies that have appeared are very heterogeneous in terms of how they have been produced. Moreover, after reviewing the studies on a methodological level, we observed that it is necessary to increase their methodological rigour.

Another of the limitations of the study is the fact that the recommendations issued by the AHA and ERC for BLS training evolve continuously, meaning that the inclusion of studies published over the last 10 years makes it very difficult to assess them in the same way.

In relation to the use of AEDs, it was not possible to describe them because most of the selected studies did not include measurement results.

Finally, researchers have not included students taking different degrees in their studies, so it has been impossible to establish differences between students, their degrees, and different training methods that it may have been possible to use.

5. Conclusions

The studies included in this systematic review are characterised by a low methodological quality and heterogeneity in terms of their interventions.

Findings have shown that the use of VAMs was more effective for learning CPR skills than the other resources analysed. With regard to the knowledge acquired, participants did not show differences between those who received a theoretical session with an instructor and participants who acquired knowledge independently through computer CDs or DVDs.

Studies did not show results of the use of AEDs, so a comparison could not be made. Therefore, we would recommend future researchers to include in their research the use of AED, since we consider it necessary to increase information regarding its use and how students can face its use in a real case. Finally, we would recommend that future research have a high methodological quality so that studies can have greater relevance.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.G.-S., C.M.-M., S.M.-I., and D.F.-G.; Data curation, M.G.-S., C.M.-M., S.M.-I., J.G.-S., and D.F.-G.; Formal analysis, M.G.-S., C.M.-M., S.M.-I., J.G.-S., and D.F.-G.; Investigation, M.G.-S., C.M.-M., S.M.-I., J.G.-S., and D.F.-G.; Methodology, M.G.-S., C.M.-M., S.M.-I., J.G.-S., and D.F.-G.; Project administration, M.G.-S.; Resources, M.G.-S.; Supervision, M.G.-S., and J.G.-S.; Validation, M.G.-S., C.M.-M., J.G.-S., and D.F.-G.; Visualization, M.G.-S., C.M.-M., S.M.-I., J.G.-S., and D.F.-G.; Writing—original draft, M.G.-S., C.M.-M., S.M.-I., J.G.-S., and D.F.-G.; Writing—review and editing, M.G.-S., C.M.-M., S.M.-I., J.G.-S., and D.F.-G.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Charlier, N.; Van Der Stock, L.; Iserbyt, P. Peer-assisted Learning in Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation: The Jigsaw Model. J. Emerg. Med. 2016, 50, 67–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gebremedhn, E.G.; Gebregergs, G.B.; Anderson, B.B. The knowledge level of final year undergraduate health science students and medical interns about cardiopulmonary resuscitation at a university teaching hospital of Northwest Ethiopia. World J. Emerg. Med. 2014, 5, 29–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jones, C.M.; Owen, A.; Thorne, C.J.; Hulme, J. Comparison of the quality of basic life support provided by rescuers trained using the 2005 or 2010 ERC guidelines. Scand. J. Trauma. Resusc. Emerg. Med. 2012, 20, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McDonald, C.H.; Heggie, J.; Jones, C.M.; Thorne, C.J.; Hulme, J. Rescuer fatigue under the 2010 ERC guidelines, and its effect on cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) performance. Emerg. Med. J. 2013, 30, 623–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roh, Y.S.; Issenberg, S.B. Association of cardiopulmonary resuscitation psychomotor skills with knowledge and self-efficacy in nursing students. Int. J. Nurs. Pract. 2014, 20, 674–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spooner, B.B.; Fallaha, J.F.; Kocierz, L.; Smith, C.M.; Smith, S.C.L.; Perkins, G.D. An evaluation of objective feedback in basic life support (BLS) training. Resuscitation 2007, 73, 417–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Szögedi, I.; Zrínyi, M.; Betlehem, J.; Újváriné, A.S.; Tóth, H. Training nurses for CPR: Support for the problem-based approach. Eur. J. Cardiovasc. Nurs. 2010, 9, 50–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davey, P.; Whatman, C.; Dicker, B. Comparison of Chest Compressions Metrics Measured Using the Laerdal Skill Reporter and Q-CPR A Simulation Study. Simul. Healthc. 2015, 10, 257–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roppolo, L.P.; Heymann, R.; Pepe, P.; Wagner, J.; Commons, B.; Miller, R.; Allen, E.; Horne, L.; Wainscott, M.P.; Idris, A.H. A randomized controlled trial comparing traditional training in cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) to self-directed CPR learning in first year medical students: The two-person CPR study. Resuscitation 2011, 82, 319–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dal, U.; Sarpkaya, D. Knowledge and psychomotor skills of nursing students in North Cyprus in the area of cardiopulmonary resuscitation. Pakistan J. Med. Sci. 2013, 29, 966–971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernandez-Padilla, J.M.; Suthers, F.; Granero-Molina, J.; Fernandez-Sola, C. Effects of two retraining strategies on nursing students’ acquisition and retention of BLS/AED skills: A cluster randomised trial. Resuscitation 2015, 93, 27–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kardong-Edgren, S.E.; Oermann, M.H.; Odom-Maryon, T.; Ha, Y. Comparison of two instructional modalities for nursing student CPR skill acquisition. Resuscitation 2010, 81, 1019–1024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Partiprajak, S.; Thongpo, P. Retention of basic life support knowledge, self-efficacy and chest compression performance in Thai undergraduate nursing students. Nurse Educ. Pract. 2016, 16, 235–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mardegan, K.J.; Schofield, M.J.; Murphy, G.C. Comparison of an interactive CD-based and traditional instructor-led Basic Life Support skills training for nurses. Aust. Crit. Care 2015, 28, 160–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jantti, H.; Silfvast, T.; Turpeinen, A.; Paakkonen, H.; Uusaro, A. Nationwide survey of resuscitation education in Finland. Resuscitation 2009, 80, 1043–1046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mpotos, N.; De Wever, B.; Cleymans, N.; Raemaekers, J.; Loeys, T.; Herregods, L.; Valcke, M.; Monsieurs, K.G. Repetitive sessions of formative self-testing to refresh CPR skills: A randomised non-inferiority trial. Resuscitation 2014, 85, 1282–1286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aqel, A.A.; Ahmad, M.M. High-fidelity simulation effects on CPR knowledge, skills, acquisition, and retention in nursing students. Worldviews Evid. Based. Nurs. 2014, 11, 394–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oermann, M.H.; Kardong-Edgren, S.E.; Odom-Maryon, T. Effects of monthly practice on nursing students’ CPR psychomotor skill performance. Resuscitation 2011, 82, 447–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boada, I.; Rodriguez-Benitez, A.; Garcia-Gonzalez, J.M.; Olivet, J.; Carreras, V.; Sbert, M. Using a serious game to complement CPR instruction in a nurse faculty. Comput. Methods Progr. Biomed. 2015, 122, 282–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Urrútia, G.; Bonfill, X. Declaración PRISMA: Una propuesta para mejorar la publicación de revisiones sistemáticas y metaanálisis. Med. Clin. 2010, 135, 507–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jadad, A.R.; Moore, R.A.; Carroll, D.; Jenkinson, C.; Reynolds, D.J.; Gavaghan, D.J.; McQuay, H.J. Assessing the quality of reports of randomized clinical trials: Is blinding necessary? Control. Clin. Trials 1996, 17, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isbye, D.L.; Hoiby, P.; Rasmussen, M.B.; Sommer, J.; Lippert, F.K.; Ringsted, C.; Rasmussen, L.S. Voice advisory manikin versus instructor facilitated training in cardiopulmonary resuscitation. Resuscitation 2008, 79, 73–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Q.; Ma, E.-L.; Liu, J.; Fang, L.-Q.; Xia, T. Pre-training evaluation and feedback improve medical students’ skills in basic life support. Med. Teach. 2011, 33, e549–e555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- López-Messa, J.B.; Martín-Hernández, H.; Pérez-Vela, J.L.; Molina-Latorre, R.; Herrero-Ansola, P. Novedades en métodos formativos en resucitacion. Med. Intensiva 2011, 35, 433–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weidman, E.K.; Bell, G.; Walsh, D.; Small, S.; Edelson, D.P. Assessing the impact of immersive simulation on clinical performance during actual in-hospital cardiac arrest with CPR-sensing technology: A randomized feasibility study. Resuscitation 2010, 81, 1556–1561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, C.; Zhao, Y.; Chen, Z.; Chen, S.; Yang, X. Improving cardiopulmonary resuscitation in the emergency department by real-time video recording and regular feedback learning. Resuscitation 2010, 81, 1664–1669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kobayashi, L.; Lindquist, D.G.; Jenouri, I.M.; Dushay, K.M.; Haze, D.; Sutton, E.M.; Smith, J.L.; Tubbs, R.J.; Overly, F.L.; Foggle, J. Comparison of sudden cardiac arrest resuscitation performance data obtained from in-hospital incident chart review and in situ high-fidelity medical simulation. Resuscitation 2010, 81, 463–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wayne, D.B.; McGaghie, W.C. Use of simulation-based medical education to improve patient care quality. Resuscitation 2010, 81, 1455–1456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nielsen, A.M.; Henriksen, M.J.V.; Isbye, D.L.; Lippert, F.K.; Rasmussen, L.S. Acquisition and retention of basic life support skills in an untrained population using a personal resuscitation manikin and video self-instruction (VSI). Resuscitation 2010, 81, 1156–1160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahn, J.Y.; Cho, G.C.; Shon, Y.D.; Park, S.M.; Kang, K.H. Effect of a reminder video using a mobile phone on the retention of CPR and AED skills in lay responders. Resuscitation 2011, 82, 1543–1547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andresen, D.; Arntz, H.R.; Grafling, W.; Hoffmann, S.; Hofmann, D.; Kraemer, R.; Krause-Dietering, B.; Osche, S.; Wegscheider, K. Public access resuscitation program including defibrillator training for laypersons: A randomized trial to evaluate the impact of training course duration. Resuscitation 2008, 76, 419–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).