Feasibility and Acceptability of a Multimedia Childbirth Education Intervention for Black Women and Birthing People and Their Birth Companions

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Background

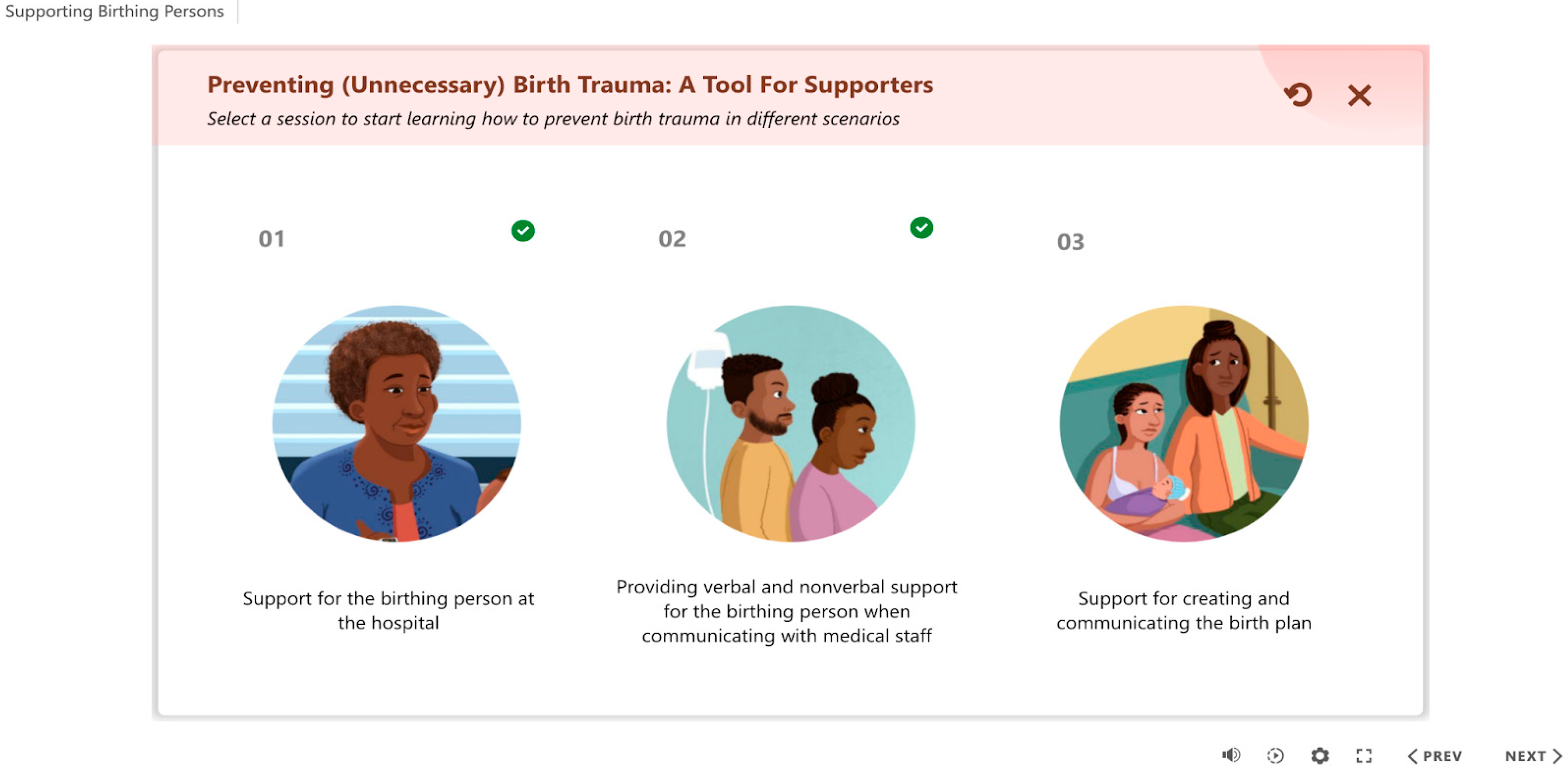

1.2. The Intervention and Current Study: Animation and Game

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants and Procedures

2.2. Survey Measures

2.3. Interview Guide

2.4. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Feasibility, Acceptability, and Appropriateness

3.2. Knowledge

One participant noted, “what caught my attention the most? Honestly, probably the part where it was saying how Black pregnant people are more likely to experience trauma”.(Participant 5, Line 217–18)

3.3. Agency

3.4. Self-Efficacy

3.5. Intentions

“Yes, definitely. I definitely would [use this tool for a future birth or share it with others]. Just to let people have that information and that give them insight if there are other options. You don’t have to keep doing that routine that had been passed on from our moms, our grandmothers, and that same routine. There’re other options now that could help us”.(Participant 2)

“…. I have little sisters and I think it’s something that if I was around a person, if I didn’t show them the game, I would at least share what I learned from it to try to help them through the process. I think it’s valuable information and people don’t talk about it. Now it’s starting to become a conversation”.(Participant 12)

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| BWBP | Black Women and Birthing People |

References

- Howard, E.D.; Bowley, M.; Patel, S. Innovations in Maternal Health Education: The Flourishing Families Virtual Education Partnership. J. Perinat. Neonatal Nurs. 2021, 35, 110–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petersen, E.E.; Davis, N.L.; Goodman, D.; Cox, S.; Syverson, C.; Seed, K.; Shapiro-Mendoza, C.; Callaghan, W.M.; Barfield, W. Racial/Ethnic Disparities in Pregnancy-Related Deaths—United States, 2007–2016. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2019, 68, 762–765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, M.C.; Halfon, N. Racial and ethnic disparities in birth outcomes: A life-course perspective. Matern. Child. Health J. 2003, 7, 13–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mueller, C.G.; Webb, P.J.; Morgan, S. The effects of childbirth education on maternity outcomes and maternal satisfaction. J. Perinat. Educ. 2020, 29, 16–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caldwell, C.J.; McCullagh, L. Recent data indicate that Black women are at greater risk of severe morbidity and mortality from postpartum haemorrhage, both before and after adjusting for comorbidity. Evid. Based Nurs. 2019, 22, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nypaver, C.F.; Shambley-Ebron, D. Using community-based participatory research to investigate meaningful prenatal care among African American women. J. Transcult. Nurs. 2016, 27, 558–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raines, D.A.; Morgan, Z. Culturally sensitive care during childbirth. Appl. Nurs. Res. 2000, 13, 167–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bohren, M.A.; Hofmeyr, G.J.; Sakala, C.; Fukuzawa, R.K.; Cuthbert, A. Continuous support for women during childbirth. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2017, 7, CD003766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McFarlane, S.J.; Wright, K.O.; Acheampong, B.; Francis, D.B.; Callands, T.; Swartzendruber, A.; Adesina, O. Reframing the experience of childbirth: Black doula communication strategies and client responses during delivery hospitalization. Soc. Sci. Med. 2024, 351, 116981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, H.H.; Heelan-Fancher, L. Female Relatives as Lay Doulas and Birth Outcomes: A Systematic Review. J. Perinat. Educ. 2022, 31, 111–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacDorman, M.F.; Declercq, E. Trends and state variations in out-of-hospital births in the United States, 2004–2017. Birth 2019, 46, 279–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hands, K.K.; Clements-Hickman, A.; Davies, C.C.; Brockopp, D. The Effect of Hospital-Based Childbirth Classes on Women’s Birth Preferences and Fear of Childbirth: A Pre- and Post-Class Survey. J. Perinat. Educ. 2020, 29, 134–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abbyad, C.; Robertson, T.R. African American Women’s Preparation for Childbirth From the Perspective of African American Health-Care Providers. J. Perinat. Educ. 2011, 20, 45–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alizadeh-Dibazari, Z.; Abdolalipour, S.; Mirghafourvand, M. The effect of prenatal education on fear of childbirth, pain intensity during labour and childbirth experience: A scoping review using systematic approach and meta-analysis. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2023, 23, 541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davenport, M.H.; Meyer, S.; Meah, V.L.; Strynadka, M.C.; Khurana, R. Moms Are Not OK: COVID-19 and Maternal Mental Health. Front. Glob. Womens Health 2020, 1, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Callister, L.C. Cultural meanings of childbirth. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Neonatal Nurs. 1995, 24, 327–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toluhi, A.A.; Richardson, M.R.; Julian, Z.I.; Sinkey, R.G.; Knight, C.C.; Budhwani, H.; Szychowski, J.M.; Wingate, M.S.D.; Tita, A.T.; Baskin, M.L.; et al. Contribution of health care practitioner and maternity services factors to racial disparities in Alabama: A qualitative study. Obstet. Gynecol. 2023, 142, 873–885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Attanasio, L.B.; Hardeman, R.R. Declined care and discrimination during the childbirth hospitalization. Soc. Sci. Med. 2019, 232, 270–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wicks, T.E. Elevating Voices for Self-Advocacy: Making the Case for Childbirth and Advocacy Education for Black Pregnant Women; Johns Hopkins University: Baltimore, MD, USA, 2021; Available online: https://jscholarship.library.jhu.edu/handle/1774.2/64075 (accessed on 6 May 2025).

- Altman, M.R.; Oseguera, T.; McLemore, M.R.; Kantrowitz-Gordon, I.; Franck, L.S.; Lyndon, A. Information and power: Women of color’s experiences interacting with health care providers in pregnancy and birth. Soc. Sci. Med. 2019, 238, 112491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cancelmo, C.M. Protecting Black mothers: How the history of midwifery can inform doula activism. Sociol. Compass. 2021, 15, e12867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wint, K.; Elias, T.I.; Mendez, G.; Mendez, D.D.; Gary-Webb, T.L. Experiences of community doulas working with low-income, African American mothers. Health Equity 2019, 3, 109–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Campbell, D.; Scott, K.D.; Klaus, M.H.; Falk, M. Female relatives or friends trained as labor doulas: Outcomes at 6 to 8 weeks postpartum. Birth 2007, 34, 220–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bruggemann, O.M.; Parpinelli, M.A.; Osis, M.J.D.; Cecatti, J.G.; Neto, A.S.C. Support to woman by a companion of her choice during childbirth: A randomized controlled trial. Reprod. Health 2007, 4, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ogunwole, S.M.; Karbeah, J.; Bozzi, D.G.; Bower, K.M.; Cooper, L.A.; Hardeman, R.; Kozhimannil, K. Health equity considerations in state bills related to doula care (2015–2020). Womens Health Issues 2022, 32, 440–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morton, C.H.; Clift, E. Birth Ambassadors: Doulas and the Re-Emergence of Woman-Supported Birth America; Praeclarus Press, LLC: Amarillo, TX, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Lantz, P.M.; Low, L.K.; Varkey, S.; Watson, R.L. Doulas as childbirth paraprofessionals: Results from a national survey. Womens Health Issues 2005, 15, 109–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kathawa, C.A.; Arora, K.S.; Zielinski, R.; Low, L.K. Perspectives of doulas of color on their role in alleviating racial disparities in birth outcomes: A qualitative study. J. Midwifery Womens Health 2022, 67, 31–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, A.; Elcombe, E.; Burns, E.S. “Paper, face-to-face and on my mobile please”: A survey of women’s preferred methods of receiving antenatal education. Women Birth 2021, 34, e547–e556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiner, B.J.; Lewis, C.C.; Stanick, C.; Powell, B.J.; Dorsey, C.N.; Clary, A.S.; Boynton, M.H.; Halko, H. Psychometric assessment of three newly developed implementation outcome measures. Implement. Sci. 2017, 12, 108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Sonderen, E.; Sanderman, R.; Coyne, J.C. Ineffectiveness of reverse wording of questionnaire items: Let’s learn from cows in the rain. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e68967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swain, S.D.; Weathers, D.; Niedrich, R.W. Assessing Three Sources of Misresponse to Reversed Likert Items. J. Mark. Res. 2008, 45, 116–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, G. The impact of incorrect responses to reverse-coded survey items. Res. Sch. 2009, 16, 76–88. [Google Scholar]

- Dahlem, C.H.Y.; Villarruel, A.M.; Ronis, D.L. African American Women and Prenatal Care: Perceptions of Patient–Provider Interaction. West. J. Nurs. Res. 2015, 37, 217–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wicks, T. Elevating Black pregnant voices for self-advocacy. ScienceOpen 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Black Mamas Matter Alliance, Policy & Advocacy Department. Black Mamas Matter: Research Justice in Policy and Practice; Black Mamas Matter Alliance, Policy & Advocacy Department: Atlanta, GA, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Lothian, J.A. Childbirth education at the crossroads. J. Perinat. Educ. 2008, 17, 45–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Vries, C.A.; De Vries, R.G. Childbirth education in the 21st century: An immodest proposal. J. Perinat. Educ. 2007, 16, 38–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Individual-Level Variable | n | % | M | SD |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 135 | 29.8 | 6.8 | |

| 18–24 | 34 | 25.2 | ||

| 25–34 | 65 | 48.1 | ||

| 35–44 | 36 | 26.7 | ||

| Residing State (Top 5) | 135 | |||

| Texas | 21 | 15.6 | ||

| Louisiana | 12 | 8.9 | ||

| Georgia | 9 | 6.7 | ||

| North Carolina | 8 | 5.9 | ||

| Michigan | 8 | 5.9 | ||

| Level of Education | 135 | |||

| Less than high school | 2 | 1.5 | ||

| Some high school | 5 | 3.7 | ||

| High school (e.g., GED) | 34 | 25.2 | ||

| Some college, but no degree | 35 | 25.9 | ||

| Associate degree | 23 | 17.0 | ||

| College (e.g., B.A. or B.S.) | 20 | 14.8 | ||

| Some graduate school, but no degree | 1 | 0.7 | ||

| Graduate school (e.g., M.S., M.D., or Ph.D.) | 15 | 11.1 | ||

| Annual Household Income | 135 | |||

| Less than USD 20,000 | 27 | 20.0 | ||

| USD 20,000–USD 44,999 | 42 | 31.1 | ||

| USD 45,000–USD 139,999 | 49 | 36.3 | ||

| USD 140,000–USD 149,999 | 3 | 2.2 | ||

| USD 150,000–USD 199,999 | 7 | 5.2 | ||

| USD 102,001–USD 105,800 | 2 | 1.5 | ||

| USD 200,000+ | 4 | 3.0 | ||

| No. of Children | 135 | 2.1 | 1.1 | |

| One | 47 | 34.8 | ||

| Two | 52 | 38.5 | ||

| Three | 20 | 14.8 | ||

| Four | 14 | 10.4 | ||

| Five | 2 | 1.5 | ||

| Marital Status When Giving Birth | 135 | 99.3 | ||

| Unmarried with a partner | 72 | 53.3 | ||

| Unmarried with no partner | 9 | 6.7 | ||

| Married | 50 | 37.0 | ||

| Divorced | 2 | 1.5 |

| M (Scale Range) | SD | |

|---|---|---|

| Feasibility of Intervention Measure | ||

| Animation | 4.30 (1–5) | 0.79 |

| Game | 4.30 (1–5) | 0.79 |

| Acceptability of Intervention Measure | ||

| Animation | 4.10 (1–5) | 0.82 |

| Game | 4.30 (1–5) | 0.70 |

| Intervention Appropriateness Measure | ||

| Animation | 4.36 (1–5) | 0.66 |

| Game | 4.29 (1–5) | 0.76 |

| Cognitive and Behavioral outcomes | ||

| Self-efficacy | 5.75 (1–7) | 1.30 |

| Agency | 5.22 (1–7) | 1.14 |

| Intention to use animation/game for future births | 4.08 (1–5) | 1.24 |

| Intention to share information | 3.46 (1–4) | 0.57 |

| Item | Pre-Test M (SD) | Post-Test M (SD) | p-Value (One-Sided) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Black women are 3–5 times more likely to die from pregnancy-related trauma than White women. | 0.66 (0.74) | 0.84 (0.37) | <0.001 |

| 2. Social support can improve birth outcomes for birthing people and their babies. | 0.82 (0.39) | 0.89 (0.32) | 0.04 |

| 3. Inadequate communication can make women more at risk for poorer health outcomes. | 0.73 (0.45) | 0.88 (0.33) | <0.001 |

| 4. Listening to the birth person’s needs and advocating for them to medical providers, if necessary, is an important skill for a birth companion or support person. | 0.87 (0.33) | 0.92 (0.28) | 0.07 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

McFarlane, S.J.; Callands, T.; Francis, D.B.; Swartzendruber, A.; S, D. Feasibility and Acceptability of a Multimedia Childbirth Education Intervention for Black Women and Birthing People and Their Birth Companions. Healthcare 2025, 13, 1106. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13101106

McFarlane SJ, Callands T, Francis DB, Swartzendruber A, S D. Feasibility and Acceptability of a Multimedia Childbirth Education Intervention for Black Women and Birthing People and Their Birth Companions. Healthcare. 2025; 13(10):1106. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13101106

Chicago/Turabian StyleMcFarlane, Soroya Julian, Tamora Callands, Diane B. Francis, Andrea Swartzendruber, and Divya S. 2025. "Feasibility and Acceptability of a Multimedia Childbirth Education Intervention for Black Women and Birthing People and Their Birth Companions" Healthcare 13, no. 10: 1106. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13101106

APA StyleMcFarlane, S. J., Callands, T., Francis, D. B., Swartzendruber, A., & S, D. (2025). Feasibility and Acceptability of a Multimedia Childbirth Education Intervention for Black Women and Birthing People and Their Birth Companions. Healthcare, 13(10), 1106. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13101106