1. Introduction

Transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS) is a non-invasive method of brain stimulation that uses a small electrical current injected through scalp electrodes to modulate neuronal activity (

Nitsche & Paulus, 2000). The subthreshold modulation induced by tDCS may result in acute effects during stimulation as well as long-lasting impacts on cortical excitability, which may persist beyond the stimulation duration (

Yavari et al., 2024). The exact mechanism of action underlying observed behavioral changes may vary from study to study based on stimulation parameters, participant characteristics, and task/treatment particulars (

Guimarães et al., 2023;

Leach et al., 2019;

Santander et al., 2024;

Vergallito et al., 2022). While the majority of mechanistic work has been performed using a motor cortex model, these same mechanisms may not hold for different brain regions that possess distinct anatomical and neurochemical attributes, and mechanisms may include impacts on peripheral and/or cranial nerves as well as non-neuronal tissue such as glial and vascular systems (

Lescrauwaet et al., 2025;

Yavari et al., 2024). Recent studies have shown that tDCS can improve cognitive performance in both clinical populations and healthy adults in domains that include social cognition, motor learning, decision making, memory, and attention (

Brunyé, 2021;

Coffman et al., 2014;

Dayan et al., 2013;

Leshikar et al., 2017;

Trumbo et al., 2016b;

Qi et al., 2022;

Wilson et al., 2018), though meta-analyses are somewhat split on whether tDCS has a consistent, replicable benefit on cognitive function, citing small sample sizes, variability in study protocols, and the impact of individual differences (anatomical and cognitive) as potential factors driving inconsistent results (

Horvath et al., 2015;

Narmashiri & Akbari, 2023).

In previous work from our lab (

Clark et al., 2012), we have investigated the effects of tDCS in a complex visual object detection paradigm. Stimuli were adapted from the “DARWARS Ambush!” program (

MacMillan et al., 2005;

Raybourn, 2009), which was used to train soldiers being deployed into combat in the Middle East. Participants were instructed to view a series of images and decide whether a target object (sniper rifle, shadow indicating an improvised explosive device, etc.) was present in each image (a detailed description of the task can be found in

Section 3 below). Functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) was used to determine neural activity elicited by the task as participants progressed from novice to intermediate and then to expert states of performance.

In this prior work, before any training, novice subjects were scanned while performing the object detection task without receiving feedback regarding their decisions. Subjects were then trained outside of the scanner until they reached an intermediate (>78% accuracy), or for a subset of seven subjects, an expert (>95% accuracy) level of performance. Once trained, they were scanned again. Learning this task (contrasting the difference between novice and intermediate groups, and between intermediate and expert) revealed a strong positive relationship between the level of activity in several brain networks (including right inferior frontal and right parietal cortex) and improved behavioral performance.

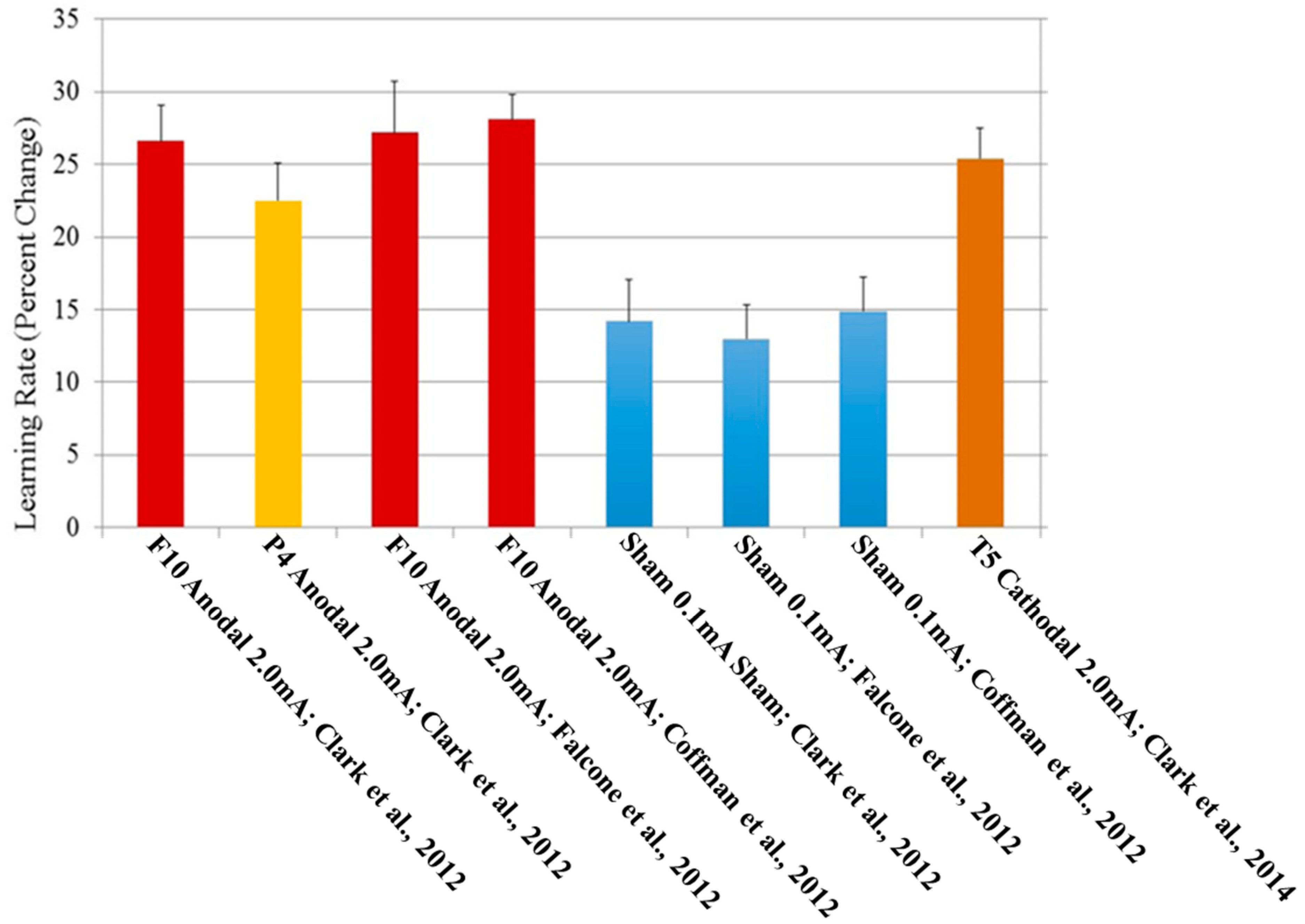

Based on these fMRI results, two candidate electrode placements were identified: targeting right inferior frontal cortex (via anode placement at site F10 in the standard EEG 10-10 system, above Brodmann’s area 44), which was the most significant using GLM methods, and right inferior parietal cortex (via anode placement at 10-10 site P4 above Brodmann’s area 39), which was the most significant using DBN analyses. When right inferior frontal cortex location F10 was stimulated for 30 min (2.0 mA, with the cathode on the left arm), participants receiving the verum dose of stimulation exhibited nearly a doubling in their ability to identify concealed target objects compared to the sham stimulation (0.1 mA) group after training combined with tDCS (26.6% learning compared to baseline for the verum group, 14.2% for the sham group). Furthermore, this effect was also observed in a delayed testing condition (21.4% increase in learning for the verum group, 10.5% for the sham group), which occurred 1 h after stimulation, suggesting that the effects lasted at least 90 min after the end of tDCS administration. Results for the P4 placement were in the same direction but of a lesser magnitude than F10 improvements (

Clark et al., 2012). Furthermore, in a separate replication performed at another institution,

Falcone et al. (

2012) found similar magnitude effects lasting for at least 24 h after stimulation using the F10 electrode placement.

Using the same paradigm described in

Clark et al. (

2012),

Coffman et al. (

2012) investigated the differential effects of tDCS on stimulus type. In the original study, 82% of the testing stimuli were novel (i.e., had not been presented during training), and only 18% were repeated images. To specifically investigate the impact of tDCS on object detection in repeated versus novel images, an experiment was conducted investigating signal detection metrics using the same types of images and procedures, but which was modified to include 50% repeated and 50% novel images.

In signal detection theory, perceptual discriminability (d’) and response bias (β) are used to determine response characteristics in participants. Perceptual discriminability is a measure indicating how well one discriminates signal from noise (or, in terms of this study, objects present, and objects absent), and is calculated as the standardized (z-scored) hit rate minus the standardized false alarm rate. Response bias is a measure of how likely one is to respond one way or the other, where values greater than one suggest a bias toward responding “object absent” and values less than one indicating a bias toward responding “object present” and is calculated by raising e to the power of ½ the difference between the squared standardized hit rate and the squared standardized false alarm rate. Ideally, when trying to improve performance on signal detection metrics, one would want to increase a participant’s d’ while not changing their bias to respond in a certain way.

Data from nine verum (2.0 mA) and ten sham (0.1 mA) participants were included in

Coffman et al. (

2012). Results suggest that verum tDCS enhanced d’ compared to sham without changing the way in which the groups responded to stimuli, evinced by no change in β across groups. Further, this effect was enhanced when comparing repeated images to novel images. Verum tDCS also showed an improvement on both hit rate (choosing correctly that an object was present in the image) as well as correct rejections (choosing correctly that no object was present in the image) across both stimulus types. There was an interaction observed between stimulus type (object present vs. object absent) and repeated versus novel images, where the verum tDCS group showed a greater improvement for repeated images only when objects were present in the image (hits), but not when objects were not present (correct rejections).

This effect is one of the few cognitive tDCS studies to be replicated in a different laboratory, location, and with different researchers performing data collection (

Falcone et al., 2012), and similar results have been found when placing the cathode over the temporal lobe, at position T5 in the 10-20 EEG system (

Clark et al., 2014). Together, these results are summarized in

Figure 1.

2. Eye Tracking Metrics and Hypotheses

The mechanism underlying the learning benefit of tDCS described above remains elusive. One possibility is that tDCS optimizes visual search by modulating visual attention or via the reduction in certain types of search errors. One method of quantifying visual attention is to use eye tracking to record search patterns to determine if and how visual search is adjusted under verum stimulation conditions. Eye tracking allows determination of both where and when someone is looking with a high degree of precision and can be used to quantify visual search characteristics such as fixations (when the eyes are stopped on a specific point) and saccades (rapid movements of the eyes) thought to reflect brain activity, thereby acting as a window to cognitive processes (

Beatty & Lucero-Wagoner, 2000). Such eye phenomena have previously been related to aspects of cognitive processing relevant to the target detection task presented here, including scene perception, attention and decision making, and visual search (

Orquin & Loose, 2013;

Schütz et al., 2011). Eye tracking uses cameras, which may be unobtrusively placed in nearly any environment, allowing for data collection to occur non-invasively and externally from a participant, thereby enabling concurrent use of eye tracking and tDCS. This combination of methods has been suggested as a useful way to investigate the effects of stimulation on neurocognition by relating application of tDCS to the cognitive processing reflected in gaze patterns (see

Subramaniam et al., 2023).

To assess the balance between ambient and focal attention during visual search, we employed the k-coefficient, a quantitative metric derived from eye-tracking data (

Krejtz et al., 2016). The k-coefficient serves as an index of attentional states, with positive values reflecting focal attention—characterized by longer fixation durations and shorter saccades, and negative values indicating ambient attention—marked by shorter fixations and longer saccades (

Krejtz et al., 2017). This metric is calculated by normalizing fixation durations and saccade amplitudes using z-scores, followed by computing their mean difference.

The k-coefficient provides insight into how participants engage with visual stimuli, offering a continuous measure of their attentional strategy throughout the task (

Holmqvist et al., 2011). In complex search environments, such as those investigated in the present study, focal attention is associated with detailed object recognition, whereas ambient attention facilitates rapid scene scanning (

Orquin & Loose, 2013). As such, the k-coefficient is a useful tool for evaluating the effects of tDCS on visual search dynamics and was analyzed alongside traditional eye-tracking metrics.

Given the aims of this study—to elucidate the mechanisms by which tDCS modulates visual search behaviors—the inclusion of the k-coefficient allows us to determine whether stimulation leads to preferential engagement in focal or ambient attention strategies. The ability of tDCS to enhance attentional control has been suggested in prior work (

Coffman et al., 2014;

Subramaniam et al., 2023), and quantifying attentional shifts in this way provides a direct means of assessing the specificity of these effects.

Unlike traditional eye-tracking metrics, which typically assess discrete aspects (e.g., fixation duration, saccade amplitude), the k-coefficient provides a holistic measure of attentional state by integrating fixation and saccade dynamics (

Krejtz et al., 2016). This allows for a more nuanced interpretation of how attention is deployed across different task conditions, particularly in real-time search scenarios where attentional flexibility is critical (

Trumbo et al., 2016a). If tDCS preferentially enhances focal attention, this would provide further support for its potential to improve real-world search tasks, such as those encountered in intelligence analysis, medical imaging, and security screening.

By identifying whether an observer’s attention is predominantly focal or ambient, the k-coefficient also has implications for training paradigms in high-stakes visual search domains. In professions such as radiology (

Bruno et al., 2015) and aviation security (

Sterchi et al., 2019), attentional allocation plays a crucial role in performance outcomes. If tDCS can be shown to influence attentional engagement as indexed by the k-coefficient, it could be leveraged as a tool for optimizing target detection performance by promoting more effective engagement with relevant stimuli.

Eye tracking metrics can be associated with regions of interest (ROIs; a section of a visual scene that is of particular concern, such as the portion displaying a target object) to allow determination of how a participant is conducting visual search and decision-making regarding that object (

Holmqvist et al., 2011). For our project, eye tracking data allowed classification of errors into error types, including sampling errors (failing to look in the relevant region), recognition errors (looking at the critical portion of a scene, but failing to recognize it as such as evidenced by visual fixation), and decision-making errors (fixating on the relevant portion of a scene, but making the wrong determination—for instance, indicating a target is not a target) (

Cain et al., 2013). It is possible that the benefit that tDCS confers on visual search stems from a reduction in a particular error type; determination of such would help move tDCS into the application space by pairing it with analysts who are concerned with the type of search error that is corrected via stimulation (

Speed, 2015).

In addition to classification of error type, the duration and frequency of fixations and saccades during visual search allow an assessment of attention during visual search as either ambient (broad allocation of attention across a visual field, associated with processing the gist of a scene) or focal (allocation of attention to a particular region, associated with detailed processing). There is thought to be an optimal attentional state for different types of search tasks (

Trumbo et al., 2016a); therefore, eye tracking represents a method of both determining attentional state in real-time and of classifying search errors in a manner that will allow appropriate matching of brain stimulation to application space.

We hypothesize that verum stimulation over F10 will lead to increased learning compared to sham stimulation as observed in prior work with this task and stimulation parameters (

Clark et al., 2012;

Falcone et al., 2012), and this effect will be especially evident in repeated image type, as shown in previous studies (

Coffman et al., 2012;

Jones et al., 2018). We also hypothesize that there will be a reduction in errors in the verum group, as elucidated by eye tracking.

This paper makes four primary contributions. (1) We replicate and extend prior work showing that anodal tDCS over F10 improves hidden-target detection, yielding medium–large learning gains (accuracy/d′) relative to sham, with effects most evident for repeated images when targets are present. (2) We integrate eye tracking with region-of-interest analyses to decompose miss errors into sampling, recognition, and decision-making components, and we show a selective reduction in decision-making errors for repeated targets in the verum group (Cohen’s d ≈ 0.80), highlighting a plausible mechanism for performance gains. (3) We test a mechanistic attention account using the k-coefficient and find no systematic shift in focal vs. ambient attention, constraining accounts of how stimulation alters search behavior. (4) We document stimulation parameters and blinding/tolerability outcomes and motivate operational relevance for high-stakes visual search domains (e.g., radiology, aviation security), helping map laboratory gains onto application needs.

3. Methods

3.1. Inclusion/Exclusion Criteria

Participants (

n = 28) were ages 18–40 years, used English as a first language, were right-handed according to the Edinburgh Handedness Inventory (

Oldfield, 1971), and had normal or corrected hearing and/or vision. They reported no history of head injury with loss of consciousness longer than 5 min, had no history of neurological or psychiatric disorder, did not have metal implants or pacemakers, reported adequate sleep prior to testing, had no prior experience with neurostimulation, were not pregnant, had no history of alcohol, nicotine, or drug abuse, and were not taking any pharmacological agents known to affect nervous system function. Participants reviewed and provided signed consent at the beginning of the first experimental session and were randomly assigned to a condition (16 verum, 12 sham). Study materials and procedures were approved by Sandia National Laboratories (SNL) Human Subjects Board (HSB) and the University of New Mexico Main Campus IRB. Additional tasks were included as part of this research, which will be described in a subsequent paper.

3.2. Target Detection Task

Participants were trained in a computer-based discovery learning paradigm, previously described in

Jones et al. (

2018), to identify the presence of targets hidden in complex static images. The target detection task was developed using the E-Prime 3.0 program to generate and present the stimuli. Hidden targets within these images included explosive devices concealed by or disguised as fruit, flora, rocks, sand, building structures, dead animals, and enemies in the form of suicide bombers, snipers, stone-throwers, or tank drivers. Stimuli were divided into two categories: repeated images were identical to those seen in training (to test veridical memory), while generalized images were related to corresponding scenes within training but with a varied spatial perspective. Generalized images were novel in that they had not been presented previously. In prior work using this task and stimulation method, we have found behavioral improvements, while present for both repeated and generalized stimuli, were greatest for repeated test stimuli with the presence of hidden targets (

Coffman et al., 2012). Examples of images presented to participants can be found in

Figure 2. Participants were instructed that they could stop the task at any time if the stimuli resulted in anxiety or discomfort of any kind. No participants elected to stop for this reason.

3.3. tDCS

TDCS was administered via an ActivaDose II Iontophoresis device using stimulation parameters based on previous research and deemed safe for use (

Clark et al., 2012;

Coffman et al., 2012) when applied according to established safety guidelines. TDCS current was administered through 11 cm

2 square saline-soaked sponge electrodes and was delivered for 30 min with the anode placed near 10-10 EEG location F10, over the right temple or sphenoid bone (

Figure 3). This location was previously identified in functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) and magnetoencephalography (MEG) studies (

Clark et al., 2012). The cathodal electrode was placed on the participant’s left upper arm.

Electrodes were secured to the scalp and upper arm using Coban self-adherent wrap. Stimulation was initiated 5 min prior to the start of training and continued through the first 2 of 4 training blocks for a total of 30 min of stimulation. Participants received a dose of either 0.1 mA (Sham) or 2.0 mA (Verum). The control (sham) condition employed 0.1 mA of current to induce the physical sensation associated with tDCS (

Trumbo et al., 2016b) while not providing enough current to alter the function of the cortex beneath, according to simulation studies that suggest at the electrode size used in this study greater than 0.5 mA of current would be necessary to alter neural activity in cortical tissue (

Miranda et al., 2009).

3.4. Eye Tracking Methods

The left eye was recorded with an SR-Research EyeLink 1000 2K system operating at 500 Hz in a dimly lit room. Visual stimuli were presented on a Dell 23 monitor (60 Hz) at a distance of 70 cm from the eye. Monitor resolution was set to 1920 pixels by 1080 pixels (16:9 ratio). A standard 9-point EyeLink calibration and validation (software version 4.56) was carried out.

3.5. Experimental Procedure

Potential participants were recruited through the University of New Mexico (UNM) research participation portal, posted advertisements on the UNM campus and surrounding area, and through the Sandia Daily News (SDN) newsletter at Sandia National Laboratories (SNL). Participants were screened prior to enrollment, following the inclusion/exclusion criteria listed above. Participants were provided an electronic consent form detailing the use of tDCS and the goals of the study.

Upon arrival for their first session at the UNM Psychology Clinical Neurosciences Center (PCNC), participants were screened for COVID symptoms and fever using a remote infrared thermometer. A physical copy of the consent form was provided for review; after ensuring there were no questions, a signature of consent was obtained. As required by the IRB, female participants took a pregnancy test prior to starting the experimental session, due to the unknown effects of tDCS during pregnancy. Next, participants completed a series of computer-based questionnaires to confirm study eligibility as well as to provide basic demographic information. Following the initial questionnaire, participants completed a mood questionnaire (a measure to be repeated at the conclusion of the session) to assess any possible impact of tDCS on mood.

Following initial assessments, participants were prepped for eye-tracking and task completion. Eye tracking calibration occurred as per the EyeLink 1000 manual and used a sticker placed on the forehead of the participant. Calibration occurred prior to each baseline block, training block, and testing block (see

Figure 4). Participants were assigned to either verum or sham stimulation in a double-blind design. Blinding was achieved using a custom-built 6-switch box (3 verum settings and 3 sham settings). Two simulators were connected to the blinding box (one set to the verum dose and one set to the sham dose), and depending on the box setting, either the verum stimulator or the sham stimulator current was allowed to pass through to the participant. The stimulation conditions (and thus box settings) were controlled by a researcher who had no participant contact and were given to the data collectors, who had no knowledge of the blinding box settings until after all data were collected. Participants’ seated position was adjusted to maintain a distance of 70 cm to the monitor and 55–60 cm to the eye-tracking device. Participants then performed the baseline block(s) for the appropriate task, according to their assigned condition (2.0 mA Verum, 0.1 mA Sham).

Participants were provided with instructions on how to respond during the task using a keyboard, but the nature of the hidden targets or any strategy on how to find them was not provided. Participants performed two baseline blocks consisting of 60 novel images per block. Images were presented for 2 s, during which time a binary response was entered (target present/target absent), followed by a variable inter-image interval ranging from 4–8 s. Baseline blocks lasted approximately 8 min. No feedback regarding performance was provided.

Following the 2 baseline blocks, the training portion of the task was administered. Prior to the training session, participants were prepped for tDCS, which was applied according to their assigned condition. Once prepped, application of tDCS was initiated, and participants were asked to report their sensations of heat, itching, and tingling at both the 1 min and 5 min mark following the initiation of stimulation, and then again following the first training block (~20 min after the initiation of stimulation). The tDCS application lasts a total of 30 min, ending approximately halfway through the second training block. Four training blocks, each consisting of 60 novel stimuli, were presented as in the baseline blocks with the addition of a short audiovisual feedback clip (~5 s) 1.5 s post stimulus. Feedback clips were short videos depicting the consequence of their response as follows: for hit trials (correct target present response), the video depicted the mission progressing as planned with a voiceover praising the correct selection; false alarm trials (incorrect target present response) resulted in being chastised for delaying the mission accompanied by a non-eventful video; correct rejection trials (correct non-target response) the video feedback and voiceover depicted the mission progressing as planned; miss trials (incorrect non-target response) were followed by video depicting the consequences of missing the target (e.g., member of the platoon shot by sniper, Humvee destroyed by IED, etc.) accompanied by the voiceover scolding the participant for missing the target resulting in members of the team being killed. Feedback videos did not provide specific details of the shape or location of a target, but did provide enough information, along with the test image, that the target type and location could be inferred from each video. Each training block lasted approximately 16 min.

Following training, the tDCS equipment was removed. Participants were then provided a short break, followed by completion of testing blocks to evaluate post training performance. Two test blocks were administered to gauge the effect of training on object detection performance. Test blocks were the same as baseline blocks in quantity and presentation; however, half of the stimuli presented in the testing blocks were repeated images presented during training, while the remaining half were similar in content to the same targets seen previously, but from a different angle or perspective. A fixation cross preceded all instructions, image stimuli and response slides. After the test period, participants concluded the session by completing an exit questionnaire and a second mood questionnaire. See

Figure 4 for a timeline of the study procedure.

4. Analysis

Data were analyzed within an Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) general linear model (GLM) framework comparing stimulation condition as the between-subjects variable (verum, sham) and performance metric as the dependent variable. Behavioral performance metrics included changes in accuracy, d’ and beta with learning. For the repeated vs. generalized analysis, no difference scores were used since that comparison was only available at post-test. For analysis of behavioral data, the learning metrics calculated were accuracy, learning score (difference between post-training test score and baseline score), d’ (d prime), and beta (response bias). Accuracy was calculated as the total number of correct responses/total number of trials, less trials without a response in the allowed time window, while learning score was calculated as the difference in accuracy between baseline and test (test accuracy–baseline accuracy). d’ (see Equation (1)) is the standardized difference between the means of the signal present and signal absent distributions, calculated as

where FA denotes the false alarm rate (target present response on a no-target trial) and H denotes the hit rate (target present response on target present trials;

Stanislaw & Todorov, 1999). β (beta; see Equation (2)), which measures bias toward signal-present responding, was calculated as:

where EXP is the exponential function in Excel, NORMSINV is the Excel function that returns the inverse of the standard normal cumulative distribution, and H and FA are the same as described above (

Stanislaw & Todorov, 1999).

For eye-tracking analysis of error type, rectangular regions of interest (ROIs) were drawn around targets on target trials, which allows for classification of different types of miss errors: sampling errors (no fixations in the ROI), recognition errors (fixations in the ROI were too brief to accurately process a target object), and decision-making errors (fixated in the ROI long enough to process target objects). For this research, we defined recognition errors as fixating in the ROI for less than 350 ms and decision-making errors were defined as fixating in the ROI for more than 350 ms. Analysis of error types provides insight into the mechanics of visual search errors, for instance, was the target was viewed long enough to recognize the object or viewed long enough to recognize the object but deciding it is not a target (

Nodine & Kundel, 1987). Eye-tracking outcome metrics included k-coefficient and error type. As typical ROIs were not available for the no-target stimulus type, only target stimuli were analyzed. All analyses were conducted with Minitab 19.2020.1 (

Minitab, 2020).

5. Results

A total of 28 participants were recruited and provided informed consent. Data were inspected for normality and for statistical outliers, using ± 3SD as a cutoff. Five participants were removed from the statistical analysis (including two verum participants, one was an outlier for learning score, and one had corrupt target detection data, and three sham participants were removed, one for incorrectly responding to the task, resulting in 82 missing responses for the baseline test, one for beta score, and one for learning score), leaving 23 for analysis (14 verum, 9 sham, 10 female, 28.80 age, 9.94 SD).

For the behavioral analysis, results suggest an overall effect of stimulation on learning (

F(1,21) = 6.34,

p = 0.0199; see

Figure 5), and d’ (

F(1,21) = 9.42,

p = 0.0058; see

Figure 5), where the verum condition performed better than sham. A trend level effect was observed for beta (

F(1,21) = 4.30,

p = 0.0510), but there were no significant effects when examining beta separately at pre-test (

F(1,21) = 0.34,

p = 0.5654), or post-test (

F(1,21) = 3.48,

p = 0.0763). Due to the beta effect, additional models were run in an ANCOVA framework with beta value as a covariate. For learning, results suggest a marginal effect of stimulation condition (

F(1,20) = 4.24,

p = 0.0526; Cohen’s

d = 0.88). For d’, results suggest a reduced, though still significant, effect of stimulation (

F(1,20) = 5.53,

p = 0.0290; Cohen’s

d = 1.00). Means and standard deviations of pre and post metrics can be found in

Table 1.

To evaluate the possibility of a speed/accuracy tradeoff, we completed analyses related to reaction time (RT). There were no effects of stimulation on RT change scores (

F(1,21) = 1.20,

p = 0.2681). The average RT difference for the verum group was −149.7 ms (348.9 ms SD), and for the sham group was 14 ms (353 ms SD). Examining the effect of stimulation of repeated and generalized images separately at post-test revealed an effect of stimulation for both stimulus types, where again the verum condition was superior to sham (repeated—

F(1,21) = 7.17,

p = 0.0141, generalized—

F(1,21) = 7.52,

p = 0.0122; see

Figure 6). There were no effects of stimulation on beta values for either repeated (

F(1,21) = 0.76,

p = 0.3936) or generalized (

F(1,21) = 1.72,

p = 0.2044) images. As was done for the learning and d’ overall score, ANCOVAs were run with beta as a covariate. Results suggest that the effect persists for both repeated (

F(1,20) = 5.90,

p = 0.0247; Cohen’s

d = 1.04), and generalized (

F(1,20) = 6.82,

p = 0.0167; Cohen’s

d = 1.12) image types.

For the eye-tracking analysis, the same model was run (stimulation as a predictor, as age and gender had no effect). There was no effect of stimulation on search time consistency overall, or for repeated or generalized images (all

ps > 0.05). Further, there was no effect of stimulation on k-coefficient values (ambient vs. focal attention; all

ps > 0.05). However, there was a significant effect of stimulation on the error type analysis. Specifically, for repeated target images, there was a trend effect for the number of decision errors committed by the verum group, which was lower than that for the sham group (

F(1,21) = 4.06,

p = 0.0570; Cohen’s

d = 0.86. See

Figure 7). No effect was found for generalized target images (

F(1,21) = 1.88,

p = n.s; Cohen’s

d = 0.57).

For physical sensations and mood analyses, all participants who completed the experiment were included in the analysis. There was an effect of stimulation on itching, where participants in the verum condition rated itching as more intense than sham (F(1,25) = 21.07, p < 0.001). There were no other significant sensation effects. No sensations were associated with task performance (all Pearson rs < 0.164, all ps > 0.05), suggesting that even though participants differed in itching between sham and verum, these somatic differences did not influence learning and performance. Looking at just those participants included in the results section, a Chi-squared test revealed no association between assigned condition and guessed condition (x2(1) = 2.76, p = 0.0964), suggesting blinding was achieved. For the mood analysis, there were no effects of stimulation.

6. Discussion

In this experiment, findings from prior work with the target detection task (e.g.,

Clark et al., 2012;

Coffman et al., 2012;

Falcone et al., 2012) were replicated and further explained with the use of eye-tracking. It is possible that the brain region targeted by this type of stimulation, the right inferior frontal gyrus, is particularly involved in the identification of hidden targets as part of an evolutionary background in the detection of camouflaged predators and prey (

Clark et al., 2014). Eye tracking metrics allowed us to delineate between sampling errors (in which a participant failed to execute visual search in a critical area of a scene), recognition errors (in which a participant searched a critical area but did not stop to focus attention on the object in that area), and decision-making errors (in which a participant fixated on the critical region of a scene but ultimately miscategorized the object contained in that region). This led to the discovery that the overall learning benefit of verum stimulation was being driven by a particular reduction in decision-making errors for scenes that contained a target. This adds to the small body of research that has combined the methods of tDCS and eye tracking, and supports the typical finding reported in a recent review that active stimulation has an impact on gaze characteristics (

Subramaniam et al., 2023). As an additional contribution, only three of the reviewed studies featured stimulation delivered online with a behavioral task, as in the current work.

In analyst domains, both false positives and false negatives create risk, albeit for different reasons. False positives may have a cumulative detriment, as validation of each instance takes time and attention, such that a preponderance of false positives may lead to alarm burnout, reduced trust in the system, and eventual desensitization that creates risk of dismissing a valid alarm (

Alahmadi et al., 2022). On a singular basis, however, false positives offer the possibility of further investigation and therefore an opportunity for accurate assessment. This is not true of false negatives for which a singular error can be catastrophic, as in the case of a radiologist who misses early identification of a tumor and therefore an effective treatment window (

Bruno et al., 2015), a baggage screener who misses an improvised explosive device (

Sterchi et al., 2019), or an intelligence analyst searching cybersecurity data and missing signs of an insider threat (

Yerdon et al., 2021). These types of analyst domains therefore value reduction in false negatives. In our experiment, the most common error type was a decision-making error in which a participant looked at a target but ultimately decided that a target was not present in the scene—a false negative.

Given the criticality of target identification in the aforementioned analyst domains, this represents an important step toward determining the potential for tDCS-enhanced learning as a part of analyst training. While we did not have any significant findings regarding focal vs. ambient attention, this might be an artifact of the timing for this task; participants are only given 2 s to respond, which may not be enough time for a shift in these types of attentional states to be detectable. While analysts do not have an unlimited amount of time to make decisions, they are typically allowed some flexibility in decision-making time, with an emphasis on accuracy above speed and no forced progression of stimuli (

Speed, 2015). Therefore, should the opportunity for ecologically valid follow-up work present itself, we would like to keep these attention metrics in mind as they might prove a useful indicator of performance in operational environments. It is worth noting that the type of error that was specifically reduced—decision-making error—was also the most common error made, so the ability to reduce this error type might have utility both due to ubiquity as well as potential consequence.

One limitation of the present study is the exclusion of pupillometry data, which could have provided additional insight into the cognitive and physiological mechanisms underlying tDCS-induced changes in visual search. Pupillary responses have been widely used as indicators of cognitive load and attentional engagement (

Mathôt, 2018), and their inclusion could have allowed for a more detailed understanding of the interaction between neural stimulation and autonomic nervous system activity. Our decision to exclude pupillometry was based on both methodological and practical constraints. First, the rapid-paced nature of the target detection task required participants to scan complex scenes and make decisions within a highly constrained timescale. Pupillary responses, which operate on a slower timescale relative to fixation-based eye-tracking measures, may not have provided a meaningful reflection of cognitive load under these conditions (

Eckstein et al., 2017). Given the short stimulus presentation duration, there was concern that pupil dilation changes would not have had sufficient time to manifest in response to individual stimuli, limiting their interpretability in the context of the search strategy.

Additionally, given time and budget constraints, we prioritized measures most directly aligned with our research questions and the feasibility of data collection. Pupillometry requires additional methodological considerations, including strict control of ambient lighting conditions and the use of advanced filtering techniques to remove noise introduced by blinks or transient luminance changes (

Laeng et al., 2012). Given these factors, we opted to focus on fixation and saccadic measures, which provided more reliable indicators of visual attention and decision-making strategies in our experimental paradigm.

Absent the practical constraints of the current study, future studies can overcome the aforementioned methodological considerations to incorporate pupillometry to further investigate the physiological underpinnings of tDCS-enhanced visual search. Specifically, analyzing pupil dilation during the decision-making phase of trials could offer insight into whether tDCS modulates cognitive effort or arousal levels when participants engage in target detection. By integrating pupillometry with fixation-based metrics, future research could develop a more comprehensive model of how stimulation influences attentional resource allocation across different phases of visual search. Such an approach would be particularly valuable in extending our findings to more naturalistic settings, where search duration is less constrained, allowing for greater sensitivity in measuring pupil-related cognitive effects.

The sample collected here presents limitations in terms of both size and balance, owing to data collection initiated during the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, which limited the ability to recruit participants. Future work should certainly endeavor to include a greater sample size that is balanced to allow confidence in the results. In addition, given the potential applicability of these findings to visual analysts, a sample of professional analysts should be included rather than a pure student sample, as professional analysts may possess different characteristics that interact with the stimulation protocol, leading to a different pattern of behavioral changes. Given these limitations, the current work is perhaps best thought of as a pilot study that provides some direction for future work rather than conclusions resulting from the current effort. It is also possible that other electrode placements that have resulted in task performance benefit (

Clark et al., 2012,

2014) have achieved this benefit through different mechanisms than the F10 vs. left arm placement used in the current study. Inclusion of eye tracking during replication attempts involving these alternate placements would help determine if the mechanism of improvement is the same.

TDCS is a particularly appealing technology for the enhancement of learning in complex training scenarios for two reasons: more difficult and cognitively demanding tasks are more likely to benefit from tDCS (

Gill et al., 2015;

Matzen et al., 2015), and tDCS appears to have particularly large effect sizes in the domain of accelerated learning (

Clark et al., 2012;

Coffman et al., 2014). Therefore, we propose that tDCS could be used to accelerate the training of analysts. Benefit can be achieved via reaching critical performance thresholds faster, or via reaching higher levels of performance when given the same amount to train (expert level of performance was reached in half the time with verum stimulation vs. sham stimulation in

Clark et al., 2012;

Coffman et al., 2012;

Falcone et al., 2012).

It is also worth mentioning that we did not find any negative impact of brain stimulation on mood, and in fact, brain stimulation has been found to be more tolerable with regard to side effects than commonly used pharmacological enhancements such as caffeine (

McIntire et al., 2017).

7. Conclusions

In sum, we found that online tDCS over F10 improved hidden-target detection learning and perceptual discriminability (d′), with large effect size (learning: Cohen’s d ≈ 0.88), and that the putative mechanism involves a selective reduction in decision-making errors on repeated target images (large effect; d ≈ 0.86), even though the corresponding p value (p = 0.057) is marginal. There was no evidence for a speed–accuracy trade-off, no systematic shifts in focal vs. ambient attention (k-coefficient), and blinding and tolerability checks were acceptable. These findings suggest near-term utility for analyst training contexts that prioritize minimizing false negatives (e.g., radiology, aviation security, and cyber defense), where fewer decision errors could yield meaningful operational gains. Future work should pursue adequately powered, preregistered replications with balanced groups and professional analyst samples, incorporate pupillometry alongside eye-movement measures, explore alternative montages and parameter optimizations, allow longer decision windows to probe attentional dynamics, and assess individual-difference moderators to inform targeted application.