1. Introduction

Within the context of Chinese culture, marriage and childbearing have long been regarded as firmly expected behaviors (

Blair et al., 2022). Within the tenets of Confucianism, dating back to 770 BC, males were expected to be the authority figures within families, while women were supposed to defer to their husbands (

S. W. K. Yu & Chau, 1997). One central feature is “xiao,” or filial piety, which stipulates that children should devote themselves to their families and respect the wishes of their parents (

J. Han, 2008). Consequently, the continuation of the family lineage has always been essential, and arranged marriages allowed parents to control the selection of a spouse (

Wolf & Huang, 1980). From the perspective of daughters and sons, the obligations of filial piety meant that they should comply with the wishes and directives of parents, from childhood through adulthood (

Yeh & Bedford, 2003).

The cultural expectations concerning marriage and childbearing have a long history, yet in recent decades, China has undergone considerable change. The shift to a market economy in the 1980s and the opening of China to the world in the 1990s led to the growth of its middle class, which resulted in decided shifts toward materialism, individualism, and personal expression. Among young adults, these cultural shifts are evident in their increasingly progressive attitudes toward intimate relationships, sexual activity, and the relative meaning of marriage and parenthood (

R. Yang & Neal, 2006;

Blair & Scott, 2019). There have also been substantial increases in women’s educational attainment, leading to higher rates of occupational attainment, financial security, and autonomy (

Guthrie, 2008;

Li, 2000). Increasingly, contemporary Chinese women view traditional marriage as being less than desirable (

Neels et al., 2017).

Given the skewed sex ratio, contemporary women have adopted a more nuanced approach to relationships, such that prospective males must demonstrate the ability to provide a suitable level of material comfort (e.g., home and car ownership) (

Piotrowski et al., 2016). Despite its long history of filial piety and conservative family values, young adults appear to be adopting a more progressive and individualistic approach to intimate relationships. These changes are readily evident in the higher rates of cohabitation (

Y. Zhang, 2017), higher rates of premarital sex (

Blair & Scott, 2019), higher rates of divorce (

Chen & Shi, 2013), and higher ages at first marriage (

Blair et al., 2022). Nonetheless, most young women and men continue to view becoming married as a means of fulfilling their obligations of filial piety (

Gui, 2023). For their part, parents still attempt to control their adult children by providing or withholding financial support, assisting with childcare, and offering other services (

Jin et al., 2015;

J. Yu & Xie, 2015).

This study seeks to further our understanding of the changes in young adults’ aspirations for traditional family roles in China. Through the use of data from a multi-year survey project starting in 2015 and running through 2024, it will examine changes in the marriage and parenthood preferences of young women and men. The timing of the survey occurs over years in which changes in fertility policy occurred, along with the pandemic, both of which may have affected aspirations. Given that many of the recent societal changes in China have had tremendous effects on gender and gender roles, this study will also examine how preferences for marriage and childbearing vary among young females and males.

1.1. Marriage and Parenthood in the Chinese Context

In China, becoming married and bearing children have consistently been regarded as both normative and necessary. Individuals who choose to remain single, and especially those who opt to remain childless, are often regarded with derision and scorn, as their choices are viewed as selfish and dishonorable (

Yao et al., 2018). One of the means by which young adults may demonstrate their filial piety is through becoming married, having children, and thereby continuing the family lineage (

J. Han, 2008;

Yeh & Bedford, 2003). However, in 1950, the government introduced the New Marriage Law, which banned arranged marriage and strongly encouraged young adults to choose their partners of their own free will. As such, many young adults are postponing marriage until later in life, resulting in an increasing average age at first marriage (

Blair et al., 2022;

H. Han, 2010). In essence, the economic growth and the accompanying increase in materialism appear to have prompted young adults to pursue individual success and attainment (e.g., college degrees, high-income jobs, and home ownership), rather than attending to their filial piety obligations by becoming married and having children (

Chuang & Yang, 1990).

In the contemporary regard, young adults are adopting approaches to intimate relationships that are decidedly more progressive. College students often take advantage of the minimal oversight by parents, and dating, holding hands, public displays of affection, and sexual intercourse have become common (

Jankowiak & Li, 2017;

R. Yang, 2011). Social media apps, such as WeChat, have become the primary venues by which young adults find that “special someone,” and initiate a dating or sexual relationship (

Blair & Scott, 2019;

Xue et al., 2017). Researchers have noted, though, that many young adults still consider the needs of their family when they are deciding about their own intimate relationships (

Y. Zhang, 2017). Hence, there is an interweaving between traditional cultural expectations and the more progressive approaches being taken by young adults (

Madigan & Blair, 2018). In terms of the specific traits that are sought by young adults in a partner, pragmatic qualities (e.g., high income and educational attainment) remain important (

Gui, 2017), despite the growing emphasis upon romantic aspects of relationships. For their part, parents still attempt to insert themselves into the relationship choices of their adult daughters and sons (

J. Zhang & Sun, 2014), reflecting their own adherence to more traditional norms concerning marriage and parenthood. The generational differences appear to be quite salient, yet these also must be considered in regard to some of the substantial changes in the larger social structure.

1.2. The Impact of Fertility Policies, the COVID-19 Pandemic, and the Developmental Paradigm

Pro-natalism has long been a component of Chinese culture, yet government policies have restricted childbearing. Given the rapid population growth of the 1960s, the government was concerned that overpopulation would lead to major societal problems. In the 1970s, it enacted the “Wan, Xi, Shao” (later, longer, fewer) program, which encouraged young adults to wait until later in life to marry, to space their births farther apart, and to have fewer babies. In 1979, the One-Child Policy was introduced, generating considerable resistance and public outcry. Subsequently, the government did create exceptions to the policy, but its implementation also brought about a variety of other dilemmas, including a sharply skewed sex ratio, which resulted from the strong preference for sons, in combination with female infanticide and sex-selective abortions (

Blair et al., 2022).

After recognizing the problems associated with its fertility policy, in 2015, the CCP decided to change its long-standing policy by changing it to a Two-Child Policy, with the intention of raising the total fertility rate. When the expected fertility increases did not appear, the CCP changed its fertility policy, yet again, in May 2021, to the Three-Child Policy. This new policy was intended to provide not only encouragement for existing couples to bear additional children but also to create an increased set of birth aspirations among those who were yet to marry (

Blair & Dong, 2023). Hence, the childbearing aspirations of young adults are being developed within a context in which they are allowed to have, if they so desire, more children than previous generations. Despite these pro-family policy changes, fertility rates in China have continued to decline (

Meng et al., 2023). The prevailing sentiment is that most young adults do not regard the opportunity to have additional children as any sort of requirement on their part (

Jiang & Liu, 2016), and that having either a single child or no children at all is the optimal choice (

C. Zhang et al., 2023).

While the fertility restrictions have affected marriage and childbearing aspirations since the 1970s, the COVID-19 pandemic may have created additional hindrances. In December of 2019, the COVID-19 virus was identified in Wuhan, and the disease was soon classified as a global pandemic by the World Health Organization (

WHO, 2020). The government reacted quickly to the situation and began to introduce city-wide mandatory quarantines, effectively shutting down the day-to-day lives of citizens (

Tong et al., 2023). These conditions created considerable panic, leading to a variety of stress disorders (

Guo et al., 2020) for individuals, and created tremendous strain within the relationships of existing couples (

Dattilo et al., 2022). Among those hoping to begin or maintain an intimate relationship, the pandemic created an incredibly pessimistic background for their marriage and childbearing aspirations (

Blair et al., 2022;

Tong et al., 2023).

College and university students in China quickly found themselves confined to their dormitories and apartments, as the strict quarantines prohibited any freedom of movement (

Cheng et al., 2023). Young women and men were now left with tremendous uncertainty about their prospects for a normal, happy future life (

Paredes et al., 2021). The isolation, fear, and anxiety about the ongoing pandemic undoubtedly affected young adults’ aspirations, and the strictly enforced social isolation only served to magnify those stressors (

He et al., 2022). For young adults, the inability to interact with peers, significant others, and intimate partners during the pandemic led to an array of mental health problems (

Dattilo et al., 2022). However, the fear and anxiety produced by the pandemic actually led many young adults to reach out to others via the internet, as “video dating” and the use of social media apps (for the explicit purpose of pursuing intimate relationships) increased dramatically (

Alexopoulos et al., 2021).

Social isolation has been shown to have a deleterious impact upon perceptions of relationship satisfaction and commitment (

Flora & Segrin, 2000). In this same regard, the social isolation and loneliness experienced during the pandemic may have led some individuals to seek out any available partner, largely out of desperation (

Skakoon-Sparling et al., 2023). Hence, the characteristics sought in a prospective partner prior to the pandemic may have been disregarded, due to the stress of the pandemic (

Alexopoulos et al., 2021). Specific aspirations concerning marriage and childbearing were undoubtedly affected, given the tremendous uncertainty felt by young adults about their futures (

Wong & Alias, 2021). While the short-term impact of the pandemic has been well-examined, the long-term consequences, particularly in regard to marriage and childbearing, remain to be seen (

Mengzhen et al., 2024).

The marriage and childbearing choices formulated by contemporary young adults developed within a changing and turbulent time. Over the past decades, the modernization of China has resulted in significant shifts in materialism, individualism, and gender roles (

Constantin, 2024).

Thornton (

2001) posits that societal modernization will lead to changes in family structures and familial norms, such that families will become smaller (fewer children) and geographically mobile. Thornton’s developmental paradigm proposes that aspirations for marriage and childbearing will also change, as “developmental idealism” will supplant traditional ideologies with those more focused upon individuality, equality, and personal choice (

Thornton & Philipov, 2009).

More specifically, the developmental idealism paradigm argues that education, industries, and city life create pathways for ideational changes that will produce family changes (

Thornton, 2001). China has greatly increased the levels of educational attainment among young cohorts over the last several decades, especially for women. It has experienced one of the largest internal migrations of people ever seen in recent times, as several hundred million rural dwellers left agricultural-type jobs to take on new forms of employment ranging from factory line work to high-tech jobs in multinational corporations in the cities. Rapid urbanization has resulted in China having dozens of cities containing one million people or more, and the largest ones are the most developed economically. Also, although urban job opportunities have opened up chances for social mobility, the extreme level of economic inequality makes getting by (getting a quality education, finding a good job, buying a reasonably priced home, taking care of parents, and affording to have children) tougher and tougher.

Competing forces appear to be affecting the marriage and fertility decisions of young women and men in China, and thus it would be helpful to gain a sense of how they are impacting plans and aspirations. On the one hand, they have come of age during a time of modernization, which tends to lead people to think less traditionally and more individualistically. On the other hand, China’s government has recognized a low fertility population problem on the horizon, so it has been making drastic changes to its family policies with the intent to encourage couples to procreate (

S. Yang et al., 2022;

Peciak, 2023). On top of these cultural, structural, and policy shifts, the lives of the most recent cohort were put at risk due to the pandemic, leaving most without the opportunity to engage in face-to-face relationships with an intimate partner. Further exacerbating the situation, China’s record-breaking economic growth has slowed considerably, which has led to high rates of youth unemployment. Indeed, the social lives of young adults, along with their aspirations, have been through a maelstrom over recent years. There is an urgent need to better understand how their respective aspirations for marriage and childbearing may have changed over time, and what factors have influenced such patterns.

2. Methods

Beginning in the summer of 2015, an annual survey of undergraduate students attending public universities in Nanjing, Shanghai, and Wuhan was initiated. Students were asked to participate in a survey concerning intimate and marital relationships, along with their aspirations for the future. Participants were informed that their responses would be completely anonymous and that their participation was voluntary. This cross-sectional survey was repeated on students in successive years, with data being collected in 2016, 2017, 2018, and 2019. As a result of the COVID-19 quarantines, the survey was not conducted during the years of 2020 and 2021. In 2022, 2023, and 2024, the survey was continued.

Over the length of the study, almost 89% of students who were approached did, indeed, agree to participate. In the pre-pandemic years (2015–2019), the sample included 918 females and 609 males, whereas in the post-pandemic years (2022–2024), the sample included 924 females and 505 males. Data presented in the descriptive graphs is drawn from the full survey (all years), while the multivariate analyses use data from the recent post-pandemic years (2022–2024).

In terms of marriage, the respondents were asked about their agreement with the statement: “I would like to get married someday.” Responses to this item ranged from “strongly disagree” (1), “agree” (2), “unsure” (3), “disagree” (4), and “strongly agree” (5). Higher values indicate a stronger desire to marry. Students were similarly asked at what age they would prefer to marry in the future. Fertility aspirations were assessed with the query: “Ideally, how many children would you like to eventually have?” As was the manner in the question concerning marriage, students were asked: “If you want to have children, ideally, at what age would you like to start?” Combined, these items assess both the desire for marriage and childbearing, overall, as well as the specific timing of the transition into marriage and childbearing.

A wide array of family, peer, and individual characteristics is included in the analyses of marriage and fertility aspirations. Respondents were asked if they would be willing to marry someone without the approval of their parents. Responses to this item ranged over a 5-point scale, with higher scores indicating a greater willingness to marry without parental approval. Respondents were also asked: “When you think about the relationship between you and your parent(s), how close to you feel to them?” Responses ranged from “not close at all” (1) to “very close” (4). Given that marriage and childbearing aspirations may be influenced by the marital relationship of their parents, respondents were asked: “For most of the time when you were growing up, did you think that your parents’ marriage was: “not too happy” (1), “just about average” (2), “happier than average” (3), or “very happy” (4).

Peer role models may affect aspirations, so respondents were asked how many of their close friends were currently dating (with responses ranging from “none/only a few” (1) to “almost all” (5). Across a variety of different traits, respondents were asked whether they considered characteristics in a prospective partner to be “not at all important” (1) to “very important” (7). From these items, three distinct measures were created: pragmatic qualities (well-educated, wealthy, successful, and ambitious), caring qualities (affectionate, loving, considerate, and kind), and appearance qualities (sexy, neat, attractive, and well-dressed).

In order to assess adherence to cultural standards concerning intimate relationships, respondents were asked if: “I would be willing to have sex on a first date,” with responses ranging from “strongly disagree” (1) to “strongly agree” (5). Respondents were also asked about their agreement with the statement: “I would be willing to live with someone before getting married.” Again, responses ranged from “strongly disagree” (1) to “strongly agree” (5). With these two measures, higher scores would indicate more progressive attitudes about dating. Finally, respondents were asked about their agreement with each of the following statements: “A person can have a fully satisfying life without getting married,” and “A person can have a fully satisfying life without having children.” For each of these measures, responses ranged from “strongly agree” (1) to “strongly disagree” (5), with higher scores indicating a lower valuation of marriage and/or childbearing.

The analytical plan first compares respondents’ desire to marry as well as the mean number of desired births by sex across eight time points. Graphing the means across time allows for an analysis of trends in these outcomes after the governmental family policy changes and the impact of COVID-19. They also allow for comparisons between the genders. Next, descriptive statistics for the independent variables in the regression models are presented along with tests for differences between females and males. Finally, ordinary least-squares regression models were run to estimate the effects of the various explanatory variables on the outcomes of desire to marry, preferred age at marriage, desired number of children, and preferred age at 1st birth. Because females and males could be differentially impacted by social forces relating to decisions concerning marriage and fertility, they were modelled separately.

3. Results

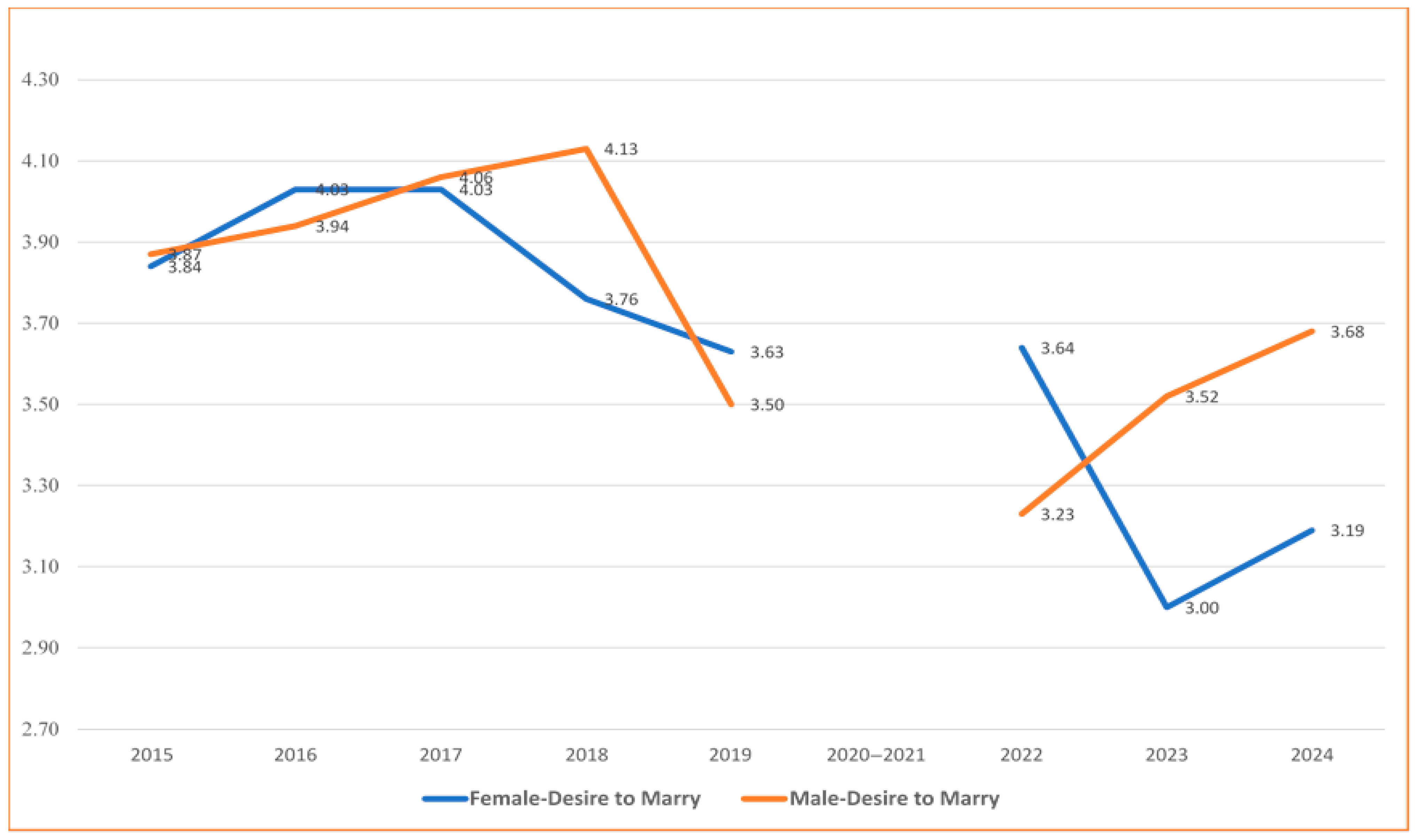

Figure 1 presents the mean levels of the desire to marry, by sex, and across the period from 2015 to 2024. As shown, both female and male aspirations for marriage appear to decline sharply over time. Although female and male aspirations for marriage follow a similar trajectory prior to the pandemic (2020–2021), young women’s desire to marry appears to drop substantially in the post-pandemic period. Interestingly, young men’s desire to marry clearly declines between 2019 and 2022 but rises in the post-pandemic years. Given that face-to-face dating experiences were difficult, if not impossible, during the pandemic lockdowns in China, the declines in marriage aspirations are somewhat understandable. However, the sharp differences in female and male marriage aspirations during the post-pandemic years suggest that a considerable gap exists in how each sex perceives the value of marriage. These patterns may indicate that young women are choosing a decidedly more progressive approach to marriage (i.e., postponing marriage, opting to cohabit, or remaining single), while the aspirations of young men remain largely consistent with the cultural expectations of previous generations (i.e., marry early and have children). The divergence in the attitudes of young women and men has been noted in previous studies (e.g.,

Constantin, 2024;

Gui, 2023), yet these findings suggest that the attitudes of young women have changed substantially over the past decade.

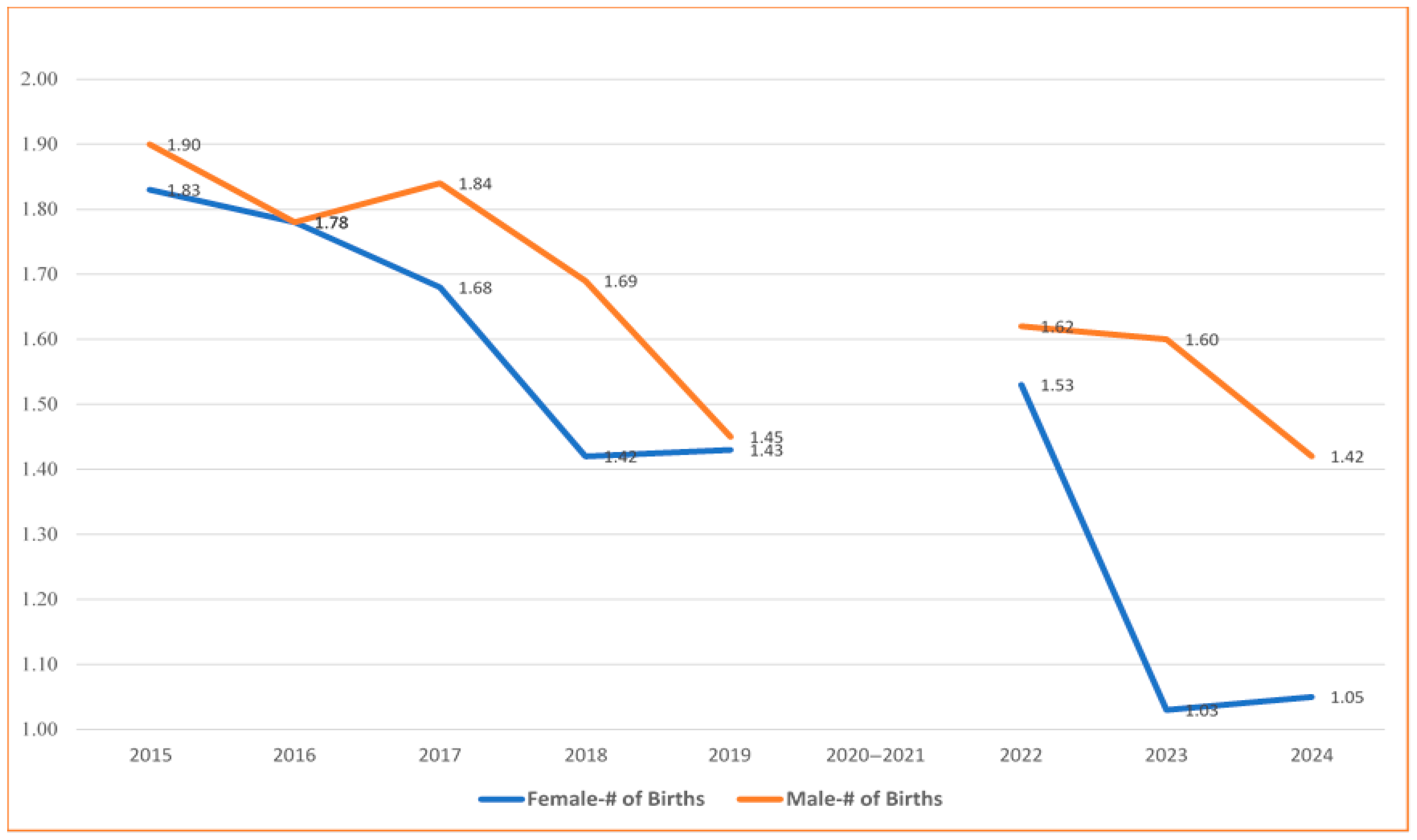

Figure 2 presents the mean number of desired births, by sex, across the same time period (2015 through 2024). Among females, the highest desired number of births is shown in 2015, with an average of 1.83 births, while the lowest number is shown in 2023, with an average of 1.03 births. Across all years, males report a significantly higher number of desired births, with a reported high of 1.90 in 2015, and a low of 1.42 in 2024. Overall, it is abundantly clear that, for both sexes, the number of desired births has declined. Given that the One-Child Policy was changed to a Two-Child Policy in 2016, and then a Three-Child Policy in 2021, it is reasonable to assert that the fertility aspirations of young adults (and especially young women) were not positively influenced as a result. Indeed, the reported fertility aspirations suggest that the total fertility rate in China will likely continue to decline over the coming years.

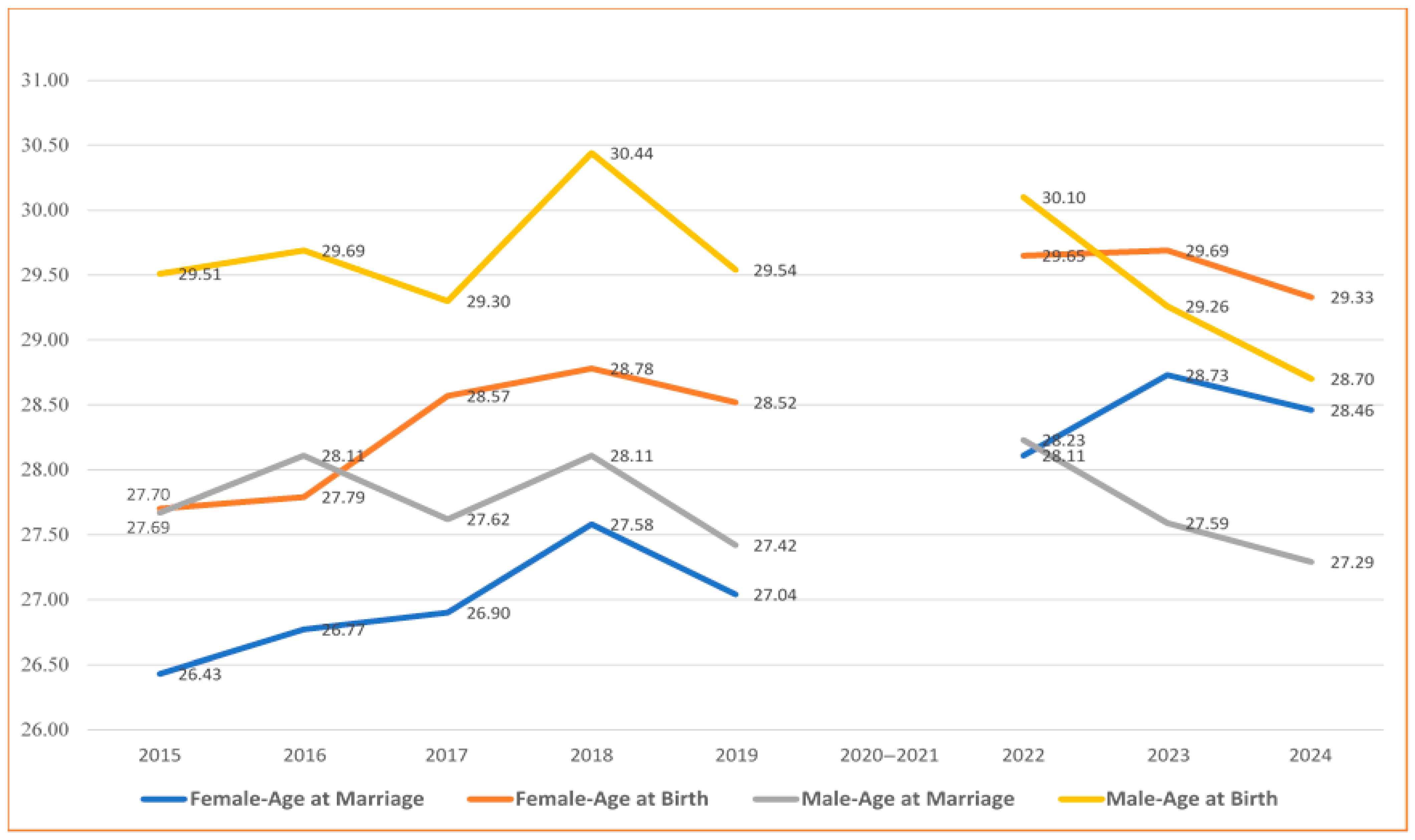

Figure 3 presents the mean desired ages at the time of first marriage and first birth, by sex, across the period between 2015 and 2024. In terms of the timing of marriage, the desired age among females ranged from a low of 26.43 in 2015 to a high of 28.73 in 2023. The timing of marriage among females demonstrates a steady increase over the years, while the desired timing among males is relatively consistent over time, with a low of 27.42 in 2019 to a high of 28.11 in 2022. Among females, the timing of first birth again appears to steadily increase over time, with a low of 27.67 in 2015 to a high of 29.69 in 2023. The desired timing of first birth among males is more erratic, ranging from a low of 28.70 in 2024 to a high of 30.44 in 2018. It is important to note that, during the post-pandemic years (2022 through 2024), the desired age at first birth among females actually exceeds that of males. Overall, it appears that in the post-pandemic years, young women prefer to postpone both marriage and first birth to later ages, as compared directly with their young male counterparts.

Table 1 presents the mean levels of parental and dating characteristics among young adults in China. As shown, males report having a significantly closer relationship with their parents, as compared to daughters. Given the long-standing preference for sons in Chinese culture, this is to be expected. Additionally, males report that their parents have higher marital quality, as compared to the reports from females. In terms of their respective preferences for characteristics in dating partners, females have higher preferences for pragmatic, caring, and appearance qualities, suggesting that males’ standards may be lower than those of females. Not surprisingly, males were significantly more willing to have sex on a first date and had a greater desire to cohabit compared to females. Among the more meaningful differences between the sexes, though, was their respective beliefs that they could have satisfying lives without getting married and without having children. Females were significantly more likely to regard marriage and childbearing as unnecessary to having a satisfying life, as compared to males.

Table 2 presents the ordinary least-squares regression models of the marriage aspirations of young Chinese females and males. In terms of wanting to marry someday, females’ aspirations were significantly associated with their parents’ marital quality (

b = 0.110). Females’ preferences for partners with pragmatic and caring traits were also positively associated with their aspirations for marriage (

b = 0.120 and 0.096, respectively). However, females’ preference for appearance traits yielded a negative association with their aspirations for marriage (

b = −0.015), perhaps indicating that “looks” are not substantially linked to the selection of a spouse (at least relative to the pragmatic and caring traits). Interestingly, females’ desire to cohabit was positively associated with their aspirations for marriage (

b = 0.269), suggesting that contemporary females may view cohabitation as a precursor to marriage. Finally, the belief that one could have a satisfying life without children was negatively associated with females’ aspirations for marriage (

b = −0.220).

Among males, the willingness to marry without parental approval was positively associated with their aspirations for marriage (b = 0.126). This may be related to the demographic challenges of the skewed sex ratio in China, in which there is an overabundance of males. Males’ preference for partners with caring traits was also positively associated with their aspirations for marriage (b = 0.158), as was their wish to cohabit (b = 0.414). Males’ willingness to have sex on a first date was negatively associated with their aspirations for marriage (b = −0.093). This perhaps represents the pursuit of sex for individual recreational purposes.

In terms of the preferred age at marriage, females with a close relationship with their parents were shown to desire a younger age at marriage (

b = −0.399). However, the belief that they could have a satisfying life without children yielded a positive association with the preferred age at marriage (

b = 0.600). Among males, peer pressure was perhaps influential, as the number of their friends who were dating was negatively associated with males’ preferred age at marriage. Similar to females, though, males’ preferred age at marriage was also positively associated with their belief that they could have a satisfying life without children (

b = 0.219). In traditional Chinese culture, marriage and childbearing are synonymous, yet these findings suggest that there may be a growing generational difference, as young women and men in contemporary China may regard marriage and parenthood as distinct roles (e.g.,

Blair & Madigan, 2021;

Constantin, 2024). Hence, declines in marriage aspirations may further exacerbate declining rates of childbearing, as a consequence of the changing perspectives of young women and men.

Table 3 presents the regression models of fertility aspirations among young women and men in China. Females’ preferences for partners with caring traits are shown to be positively associated with their desired number of births (

b = 0.203), yet their preference for appearance traits yields a negative association (

b = −0.153). This may reflect a linkage between caring traits and parenthood (in a spouse), while appearance traits may be more linked to dating and individual pleasures. Females’ belief that they could have a satisfying life without marriage appears to have lower desired numbers of births (

b = −0.202). Among males, peer pressure is again shown to be a significant factor, as the number of friends dating is positively associated with males’ desired number of births (

b = 0.077). Like their female counterparts, though, males who believe that they can have a satisfying life without marriage appear to have a lower desired number of births (

b = −0.101). Among females, the timing of first birth is negatively associated with the number of their friends who are dating (

b = −0.372). Obviously, dating relationships among females appear to equate with the speeding up of the transition to childbearing. Similarly, females’ preference for appearance traits in a partner yields a positive association with their preferred age at first birth (

b = 0.416). Females’ belief that they can have a satisfying life without marriage is also positively associated with their preferred age at first birth (

b = 0.399). Overall, these patterns strongly suggest that the rising average age at first birth in China will likely continue into the near future. The implications and larger meaning of these findings will now be addressed.

4. Discussion and Conclusions

Over the past several decades, China has experienced substantial economic, political, and cultural change. As the country’s economy boomed during the 1990s, it led to a dramatic expansion of the middle class, along with a clear ideological shift towards greater materialism, individualism, and the pursuit of personal satisfaction (

Li, 2005). After several millennia of traditional familial norms, these ideological shifts appeared to run counter to the prevailing conservative values of Chinese family structure and values. Whereas the traditional understanding of filial piety included the stipulations of respecting the authority and wishes of parents, along with getting married, having children, and continuing the family lineage, contemporary young adults find themselves in a different environment altogether. Now, young women and men spend inordinate amounts of time on social media, enhancing their online profiles, seeking “likes,” and pursuing romantic and sexual relationships in ways that are strikingly different from those of their parents. The desire for a college education, high occupational status, and a comfortable lifestyle to be provided by the acquisition of wealth seems to have become the priorities of contemporary young adults.

This study has attempted to examine how the marriage and childbearing aspirations of young adults have changed over recent years, along with obtaining an understanding of the factors that have influenced those aspirations. The results strongly suggest that both females and males have a markedly lower interest in marriage, with their aspirations dropping steadily over the past decade. The pandemic seems to have accelerated the decline in young women’s aspirations for marriage, while those of men have increased slightly since then. Among women, both the preferred age at which to marry and have children increased over the time frame, reflecting their desire to postpone both of these milestones until later ages. Young men, particularly in the post-pandemic period, appear to prefer earlier ages. For men, a stronger desire to both marry and have children at earlier ages may reflect their collective sense of frustration about their diminished prospects, given the skewed sex ratio in China.

Among the most striking patterns, though, is the clear decline in childbearing aspirations. From 2015 to 2024, women’s fertility aspirations dropped from 1.83 to 1.05, while men’s dropped from 1.90 to 1.42. During this time frame, the government changed its fertility policies from a One-Child to a Two-Child Policy, and finally to a Three-Child Policy, yet birth aspirations continued to decline. It seems plausible that the stress and uncertainty of the pandemic caused many to lower their childbearing aspirations, yet the overall pattern of decline is quite evident. Simply, it seems rather unlikely that fertility rates will increase over the coming years, despite the changes in fertility policy.

In the multivariate analyses, females’ desire to marry was strongly associated with a combination of desired qualities in a prospective partner, as well as their wish to cohabit. These findings support the contention of the developmental paradigm, as it appears that the pursuit of individual needs (rather than those of the family) is what motivates young women to want to marry. Among women, this pattern was also evident in the relationship between their belief that they could have a satisfied life without children, suggesting that young women, in particular, may not necessarily see a direct connection between marriage and parenthood. In addition, among women, pushing off the age of marriage and of having children could put such women in a more likely position to do neither. Again, a lower desire to marry and a lower valuation of childbearing are to be expected, given the tenets of the developmental paradigm. This is also supported by the fact that males’ desire to marry is positively linked to their willingness to marry without parental approval, thus going against the traditional tenets of filial piety.

The desired number of births had clearly declined over time, for both sexes. On the surface, this does seem to indicate that the government’s efforts to increase fertility rates are not working (at least for now). The rather sharp decline in desired births among young women is of particular note, as this same pattern can be seen in many of China’s regional neighbors, such as South Korea, Japan, and even the Philippines. In the multivariate regression models of desired births, both females’ and males’ childbearing aspirations were negatively associated with their belief that they could have a satisfying life without marriage. Once again, this disconnect between marriage and childbearing runs directly counter to traditional Chinese cultural norms and is contrary to the obligations of filial piety. With the rapid modernization of China, the growth of its economy, and the shifts in ideologies toward greater individualism, it is reasonable to assert that the disconnect of marriage and childbearing is likely to become a growing pattern among young adults.

There is little question that contemporary young adults in China are choosing different paths for their futures, as compared to previous generations. Greater individualism, the pursuit of material success, and the satisfaction of personal needs are components of many modern societies around the globe (

Gans, 1991;

Eppard et al., 2020). China’s unique cultural history, however, is one which dates back approximately three thousand years (

Hsu, 2012). For young adults to opt for more individualistic pursuits and greater individualism is particularly striking, from a historical perspective. Among young adult females, the achievement of a college degree typically equates with greater autonomy and financial independence, thus further detracting from the traditional “need” to marry and have children. Among young adult males, the skewed sex ratio, along with any adherence to traditional gender ideologies, will likely make their pursuit of marriage and childbearing a challenging one, to say the least. The changing perspectives towards marriage and parenthood are not unique to China, by any means, but they do appear to be on a trajectory that will lead to lower marriage and childbearing rates.

According to the developmental paradigm, people’s ideas or “scripts” about how to live their lives will change as changes occur in the major social institutions in which they are enveloped. Individuals need to rethink how they are connected to each other at the micro level, most importantly in the realm of family relationships. In addition, they also need to reconsider how they should be attached to social institutions outside of the family, such as the economy and the state. Each attachment comes with the requisite social expectations, obligations, and exchanges. Costs and resources are involved. The links formed also occur in fields of struggle where power differences can develop and drive behavior (

Jankowiak & Li, 2017;

Jankowiak & Moore, 2017). Based on our findings above, it appears that the combined effect of changes across multiple spheres of Chinese society could be one of the most important explanations for persistently lower fertility and marriage expectations. In other words, simply ending a decades-old family policy will not result in drastic changes in behavior if marriage and fertility decisions are being heavily influenced by broader economic and structural factors (

Bao et al., 2017;

S. Yang et al., 2022).

As previously stated, the recent governmental changes to fertility policy do not appear to have produced their intended results, as the childbearing aspirations shown in this study foretell a lower total fertility rate in the near future. This most recent generation of young women and men has also gone through the terror and uncertainty created by the COVID-19 pandemic. As noted, the post-pandemic aspirations of young women are distinctly lower in regard to both marriage and childbearing. While the changing conditions that have led to the general downward trajectory of marriage and childbearing aspirations have been around for decades, it appears that the pandemic may have exacerbated and accelerated those downward patterns, at least for now.

This study has some limitations. The nonrandom selection of participants limits the generalizability of the results, as does the focus on only college students located in large cities in China. The causal impact of the pandemic is difficult to ascertain since everyone seems to have been exposed to it, and we did not ask specific questions on how it might have impacted individual decisions regarding life choices. In survey research, stated intentions of respondents might not always match their future behavior. Longitudinal surveys could perhaps uncover more nuanced shifts in thinking on topics of interest.

Future research should attempt to continue to search for and verify the patterns identified here. The researchers also need to consider additional predictors of marriage and fertility. How have incentives brought forth by the government shaped or not the calculus of fertility decisions? A cost/benefits analysis using social exchange theory seems to be a sensible approach to drill down into the sources of individual reluctance to marry and reproduce. Is nationalism on the rise, and is it connected to increased pronatalism? Young people could be asked directly if they see any connections between their fertility decisions and China’s continued economic development and social stability. What kind of changes are occurring to the fertility culture, as evidenced in official media, social media, advertising, workplace policies, corporate policies, etc., among young people in China? Future studies along these lines could take advantage of metadata by combining it with individual-level data to test how broader contextual factors might be impacting fertility culture, especially if respondents could be followed over time. To what extent are the factors that shape marriage and family decisions differentially affected by gender? Our research suggests that women seek pragmatic marital partners, but if economic change makes it more difficult for young men to succeed, then family formation will be deferred. Men seek caring wives, but if young women need to be successful economically to assist their family, they may be less appealing as marital partners (the “sheng nu” dilemma) (

Lake, 2018). If the political and economic sides of Chinese society do not change significantly enough to play a more positive role in growing families and the environments that are conducive to that, for example by confronting the hefty 4-2-1, 996, gaokao exam, rural/urban divide, stalling economy problems, and so on—all headwinds for young people to go up against as they mature and make major life decisions—then fertility will continue to stagnate. We hope that researchers, leaders, and politicians can home in on identifying the multiple manifest and latent factors that are affecting marriage and childbearing decisions in China.